User login

Rare Case of Dual Lesion: Nonossifying Fibroma and Osteochondroma

High-Altitude Illness

Patients participating in occupational and sports-related activities requiring ascent to high elevations are at risk of developing a range of high-altitude illnesses. Prompt recognition and treatment are paramount to improving outcomes and preventing life-threatening sequelae. High-elevation locations are the setting of many recreational activities for outdoor enthusiasts. As such, illnesses associated with high altitude may be encountered by those summiting peaks, traveling by air, or working in flight medicine or as part of an emergency rescue team. The altitude syndromes discussed in this review are acute mountain sickness (AMS), high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), and high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE). While these conditions do not represent all altitude-related illnesses, they are the primary pathological processes for which physicians should be familiar when working with high-altitude populations.

Physiological Response to Altitude

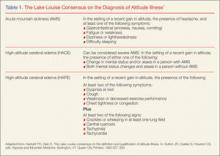

The Lake Louise Criteria

Acute Mountain Sickness

Acute mountain sickness comprises a constellation of symptoms caused by the atmospheric changes at elevations above approximately 2,500 m. It is the most common form of high-altitude illness, affecting 25% of travelers at moderate altitude and 50% to 85% above 4,000 m.3

Symptoms

The onset of symptoms (eg, headache, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, weakness) may occur at 2,000 m in the setting of rapid ascent—most commonly at 6 to 12 hours, but onset can range from 1 hour to 2 days after ascent. If symptoms begin after 3 days, other diagnoses should be considered. Symptoms of AMS are generally worse after the first night of sleep at elevation. On physical examination, vital signs are usually normal, though postural hypotension and tachycardia are possible. Oxygen saturation may be markedly decreased after rapid ascent, and chest auscultation may reveal rales in 20% of patients.4 Peripheral and facial edema may also be present. Funduscopic examination may show venous tortuosity and dilation, and retinal hemorrhage is common in ascents over 4,800 m.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for AMS is broad and includes hypothermia, dehydration, exhaustion, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracranial mass, carbon monoxide poisoning, alcohol hangover, intoxication, central nervous system infection and migraine. Risk factors for developing AMS are a previous history of altitude illness, rapid ascent, and lack of previous acclimatization. Interestingly, physical fitness does not protect a person from developing AMS.5

Mechanism of AMS

The true mechanism of AMS is uncertain, but it is clear that a fall in barometric pressure results in hypobaric hypoxia. This is thought to lead to an increased blood volume in the brain and increased cerebral blood flow, possibly precipitating an enlarged brain. A mechanism related to vasogenic edema has been proposed due to patients’ clinical improvement with dexamethasone therapy.6 Acute mountain sickness does appear to be related to overall fluid balance, as an increase in reninangiotensin, aldosterone, and antidiuretic hormone has been observed in patients with the condition. Elevation of these hormones is contrary to the appropriate physiological response of diuresis.

Treatment

Treatment of AMS begins with descent from elevation as soon as possible. Descent should be at least 500 m from the aggravating elevation. Patients should remain at least 1 to 2 days at this lower elevation before attempting reascent. If descent is not feasible, any further ascent should be delayed until symptoms have resolved.

Dexamethasone. This glucocorticoid has been used clinically with good success, although the mechanism of action in unclear. The initial dose is 8 mg followed by 4 mg every 6 hours.3

Acetazolamide. A carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, acetazolamide acts to temper symptoms by causing an acidosis that increases ventilation and prevents periodic breathing and hypoxia during sleep. The standard dose is 250 mg twice daily.3

Oxygen. Supplemental oxygen provided at 1 to 2 L/min via nasal cannula for 12 to 24 hours may help to improve symptoms. A portable hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) bag (eg, a Gamow bag) can be used to create an effective altitude of approximately 1,500 to 2,000 m inside the bag. The patient is placed completely within the bag, the zipper is sealed shut, and the bag is inflated with a foot pump. Treatment in such a chamber can be provided in 1-hour increments and repeated as needed. However, if descent is possible, use of the HBO chamber should not prevent or delay descent.

Ibuprofen. Compared to placebo, studies have shown ibuprofen 600 mg three times a day reduces the severity of AMS.7

Prevention

Strategies to prevent AMS are similar to those used to treat the condition. These include gradual ascent and prophylactic drug therapy.

Gradual Ascent. Gradual ascent is the primary strategy to prevent AMS. At altitudes above 3,000 m, each subsequent night should not be spent at an elevation 300 m higher than the previous night.

Acetazolamide. Pretreatment with acetazolamide is indicated for patients with a history of altitude illness or who anticipate an abrupt ascent (eg, rescue workers). Acetazolamide has been shown in multiple studies to be effective in the prevention of AMS.8 Adverse side effects of acetazolamide include paresthesias and increased urinary frequency; the drug may also make carbonated beverages taste flat. The preventive dose is 125 mg twice daily, and should be started the day before ascent.

Dexamethasone. In addition to treating AMS, dexamethasone may be taken as a preventive in doses of 2 mg every 6 hours or 4 mg twice daily.3 However, unlike acetazolamide, which acts to facilitate acclimatization, dexamethasone only prevents symptoms. Thus, cessation of the drug can result in rebound AMS symptoms, and prolonged use can result in adrenal suppression.3 Therefore, it should not be used for more than 10 days.

Sumatriptan and Gabapentin. In recent studies, sumatriptan and gabapentin haven shown benefit in preventing AMS, 9,10 but further study is needed before either of these drugs can be recommended.

Ginkgo Biloba. While ginkgo biloba has been touted as an effective preventive treatment, studies have shown no benefit to its use.8

Ibuprofen. ibuprofen 600 mg three times daily can be initiated the day prior to ascent, and has been shown to decrease the incidence of AMS.7

High-Altitude Cerebral Edema

Mechanism of HACE

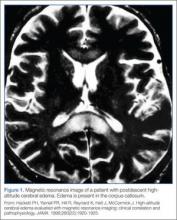

The exact mechanism of HACE is unclear. Magnetic resonance imaging of patients with the condition demonstrates cerebral edema primarily localized to the corpus callosum.11 These findings suggest an increased permeability in the blood-brain barrier, leading to vasogenic cerebral edema. Cases of death associated with HACE are the result of herniation. Fortunately, if the condition is recognized promptly and appropriate management is instituted, most patients will recover without permanent deficits.

Current recommendations for treating HACE are similar to treatment strategies for AMS.

Descent. A therapeutic priority, descent may prove challenging as the patient may be ataxic, have altered mental status, and have difficulty facilitating his or her own descent.

Oxygen. A portable HBO bag can be used to simulate descent until evacuation is possible. Supplemental oxygen should be applied immediately.

Dexamethasone. In treating HACE, dexamethasone may be administered at a loading dose of 8 mg, followed by 4 mg every 6 hours.3

Airway Management. If the patient has significantly altered mental status, appropriate airway management must be initiated.

High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema

The most common cause of death from altitude illness is HAPE,12 a form of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. This condition generally occurs at elevations above 3,000 m. Symptoms begin 2 to 5 days after ascent and progress in a typical pattern. A patient will initially experience a nonproductive cough and dyspnea at rest. The dyspnea worsens, and the cough becomes productive of pink, frothy sputum. Without medical intervention, lethargy, coma, and death may follow.

Symptoms of HAPE generally worsen following a night of sleep at elevation. Physical examination reveals crackles, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypoxia. Diagnosis requires at least two of the following signs:

- Crackles or wheezing in at least one lung field

- Central cyanosis

- Tachypnea

- Tachycardia.

In addition to the above signs, at least two of the following symptoms must also be present:

- Dyspnea at rest

- Cough

- Weakness or decreased exercise performance

- Chest tightness

- Congestion.

Mechanism of HAPE

The mechanism of HAPE is better understood than that of AMS and HACE. In HAPE, high microvascular pressures in the lungs lead to elevated pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary artery pressure. Pulmonary edema ensues, but left ventricular function is preserved. Patients with a naturally low HVR, high pulmonary artery pressures at rest, preexisting pulmonary hypertension, or a previous history of HAPE are predisposed to developing the condition. Risk factors include heavy exertion, rapid ascent, cold, salt ingestion, and sleeping medications.

Treatment

Decent and warming of the patient as soon as possible, along with treatment outlined below, are essential.

Oxygen. Treatment of HAPE begins with supplemental oxygen to immediately lower pulmonary artery pressure. Oxygen should initially be administered at 4 to 6 L/min; if the patient improves clinically and can maintain oxygen saturations greater than 90%, oxygen may be decreased with a goal to maintain saturation above 90%.

Nifedipine. Following oxygen, descent, and warming, nifedipine can be used as an adjunctive therapy. The treatment dose for HAPE is 20 to 30 mg of the sustained release form every 12 hours.3

Salmeterol/Albuterol and Expiratory Positive Airway Pressure. The oral inhalers salmeterol or albuterol may be used for bronchodilation; however, there is little evidence to support their effectiveness in HAPE. Ventilation with expiratory positive airway pressure can be employed if available.

Prevention

For patients with a predisposition to HAPE, preventive measures should be considered prior to ascent. As with all forms of altitude illness, gradual ascent is the most effective prevention method available.

Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors act via pulmonary vasodilation to prevent HAPE in some patients. Tadalafil at a dose of 10 mg twice daily or 20 mg once daily has been shown to reduce the incidence of HAPE.14 Alternatively, sildenafil 50 mg three times daily may be used.

Acetazolamide and β-Agonists. Although both acetazolamide and β-agonists such as albuterol have been theorized to aid in preventing HAPE, this has not been proven.15

Conclusion

Clinically, high-altitude illnesses range from subtle symptoms to severe, life threatening disease. Knowledge of these disease processes and clinical presentation prior to travel or work in a high-altitude setting is essential. Rapid recognition of symptoms and prompt, appropriate interventions, such as descent when necessary, can significantly improve the outcomes of these conditions.

Dr Haroutunian is an emergency physician, department of emergency medicine, Exempla St Joseph Hospital, Denver, Colorado. Dr Bono is professor and vice chairman, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

- Hackett PH, Oelz O. The Lake Louise consensus on the definition and qualification of altitude illness. In: Sutton JR, Coates G, Houston CS, eds. Hypoxia and Mountain Medicine. Burlington, VT: Queen City Printers; 1992:327-330.

- Roach RC, Bärtch P, Hackett PH, Oelz O, and the Lake Louise AMS Scoring Consensus Committee. The Lake Louise Acute Mountain Sickness Scoring System. In: Hypoxia and Molecular Medicine. Proceedings of the 8th International Hypoxia Symposium. Burlington, VT: Queen City Printers; 1993:272-274.

- Eide RP 3rd, Asplund CA. Altitude illness: update on prevention and treatment. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11(3):124-130.

- Milzman DP, Damergis JA, Napoli AM. Rapid ascent changes in vitals at altitude. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(4):536.

- Bärtsch P, Swenson ER. Clinical practice: Acute high-altitude illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(24):2294-2302.

- Hackett PH, Roach RC. Medical therapy of mountain illness. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16(9):980-986.

- Lipman GS, Kanaan NC, Holck PS, Constance BB, Gertsch JH; PAINS Group. Ibuprofen prevents altitude illness: a randomized controlled trial for prevention of altitude illness with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(6): 484-490.

- Seupaul RA, Welch JL, Malka ST, Emmett TW. Pharmacologic prophylaxis for acute mountain sickness: a systematic shortcut review. Ann Emerg Med. 2012; 59(4):307-317.

- Jafarian S, Gorouhi F, Salimi S, Lotfi J. Sumatriptan for prevention of acute mountain sickness: randomized clinical trial. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(3):273-277.

- Jafarian S, Abolfazli R, Gorouhi F, Rezaie S, Lotfi J. Gabapentin for prevention of hypobaric hypoxia-induced headache: randomized double-blind clinical trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(3): 321-323.

- Hackett PH, Yarnell PR, Hill R, Reynard K, Heit J, McCormick J. High-altitude cerebral edema evaluated with magnetic resonance imaging: clinical correlation and pathophysiology. JAMA. 1998;280(22):1920-1925.

- Gallagher SA1, Hackett PH. High-altitude illness. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2004;22(2):329-355.

- Fagenholz PJ, Gutman JA, Murray AF, Noble VE, Thomas SH, Harris NS. Chest ultrasonography for the diagnosis and monitoring of high-altitude pulmonary edema. Chest. 2007;131(4): 1013-1018.

- Leshem E1, Caine Y, Rosenberg E, Maaravi Y, Hermesh H, Schwartz E. Tadalafil and acetazolamide versus acetazolamide for the prevention of severe high-altitude illness. J Travel Med. 2012;19(5): 308-310.

- Schoene RB. Illnesses at high altitude. Chest. 2008;134(2):402-416.

Patients participating in occupational and sports-related activities requiring ascent to high elevations are at risk of developing a range of high-altitude illnesses. Prompt recognition and treatment are paramount to improving outcomes and preventing life-threatening sequelae. High-elevation locations are the setting of many recreational activities for outdoor enthusiasts. As such, illnesses associated with high altitude may be encountered by those summiting peaks, traveling by air, or working in flight medicine or as part of an emergency rescue team. The altitude syndromes discussed in this review are acute mountain sickness (AMS), high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), and high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE). While these conditions do not represent all altitude-related illnesses, they are the primary pathological processes for which physicians should be familiar when working with high-altitude populations.

Physiological Response to Altitude

The Lake Louise Criteria

Acute Mountain Sickness

Acute mountain sickness comprises a constellation of symptoms caused by the atmospheric changes at elevations above approximately 2,500 m. It is the most common form of high-altitude illness, affecting 25% of travelers at moderate altitude and 50% to 85% above 4,000 m.3

Symptoms

The onset of symptoms (eg, headache, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, weakness) may occur at 2,000 m in the setting of rapid ascent—most commonly at 6 to 12 hours, but onset can range from 1 hour to 2 days after ascent. If symptoms begin after 3 days, other diagnoses should be considered. Symptoms of AMS are generally worse after the first night of sleep at elevation. On physical examination, vital signs are usually normal, though postural hypotension and tachycardia are possible. Oxygen saturation may be markedly decreased after rapid ascent, and chest auscultation may reveal rales in 20% of patients.4 Peripheral and facial edema may also be present. Funduscopic examination may show venous tortuosity and dilation, and retinal hemorrhage is common in ascents over 4,800 m.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for AMS is broad and includes hypothermia, dehydration, exhaustion, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracranial mass, carbon monoxide poisoning, alcohol hangover, intoxication, central nervous system infection and migraine. Risk factors for developing AMS are a previous history of altitude illness, rapid ascent, and lack of previous acclimatization. Interestingly, physical fitness does not protect a person from developing AMS.5

Mechanism of AMS

The true mechanism of AMS is uncertain, but it is clear that a fall in barometric pressure results in hypobaric hypoxia. This is thought to lead to an increased blood volume in the brain and increased cerebral blood flow, possibly precipitating an enlarged brain. A mechanism related to vasogenic edema has been proposed due to patients’ clinical improvement with dexamethasone therapy.6 Acute mountain sickness does appear to be related to overall fluid balance, as an increase in reninangiotensin, aldosterone, and antidiuretic hormone has been observed in patients with the condition. Elevation of these hormones is contrary to the appropriate physiological response of diuresis.

Treatment

Treatment of AMS begins with descent from elevation as soon as possible. Descent should be at least 500 m from the aggravating elevation. Patients should remain at least 1 to 2 days at this lower elevation before attempting reascent. If descent is not feasible, any further ascent should be delayed until symptoms have resolved.

Dexamethasone. This glucocorticoid has been used clinically with good success, although the mechanism of action in unclear. The initial dose is 8 mg followed by 4 mg every 6 hours.3

Acetazolamide. A carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, acetazolamide acts to temper symptoms by causing an acidosis that increases ventilation and prevents periodic breathing and hypoxia during sleep. The standard dose is 250 mg twice daily.3

Oxygen. Supplemental oxygen provided at 1 to 2 L/min via nasal cannula for 12 to 24 hours may help to improve symptoms. A portable hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) bag (eg, a Gamow bag) can be used to create an effective altitude of approximately 1,500 to 2,000 m inside the bag. The patient is placed completely within the bag, the zipper is sealed shut, and the bag is inflated with a foot pump. Treatment in such a chamber can be provided in 1-hour increments and repeated as needed. However, if descent is possible, use of the HBO chamber should not prevent or delay descent.

Ibuprofen. Compared to placebo, studies have shown ibuprofen 600 mg three times a day reduces the severity of AMS.7

Prevention

Strategies to prevent AMS are similar to those used to treat the condition. These include gradual ascent and prophylactic drug therapy.

Gradual Ascent. Gradual ascent is the primary strategy to prevent AMS. At altitudes above 3,000 m, each subsequent night should not be spent at an elevation 300 m higher than the previous night.

Acetazolamide. Pretreatment with acetazolamide is indicated for patients with a history of altitude illness or who anticipate an abrupt ascent (eg, rescue workers). Acetazolamide has been shown in multiple studies to be effective in the prevention of AMS.8 Adverse side effects of acetazolamide include paresthesias and increased urinary frequency; the drug may also make carbonated beverages taste flat. The preventive dose is 125 mg twice daily, and should be started the day before ascent.

Dexamethasone. In addition to treating AMS, dexamethasone may be taken as a preventive in doses of 2 mg every 6 hours or 4 mg twice daily.3 However, unlike acetazolamide, which acts to facilitate acclimatization, dexamethasone only prevents symptoms. Thus, cessation of the drug can result in rebound AMS symptoms, and prolonged use can result in adrenal suppression.3 Therefore, it should not be used for more than 10 days.

Sumatriptan and Gabapentin. In recent studies, sumatriptan and gabapentin haven shown benefit in preventing AMS, 9,10 but further study is needed before either of these drugs can be recommended.

Ginkgo Biloba. While ginkgo biloba has been touted as an effective preventive treatment, studies have shown no benefit to its use.8

Ibuprofen. ibuprofen 600 mg three times daily can be initiated the day prior to ascent, and has been shown to decrease the incidence of AMS.7

High-Altitude Cerebral Edema

Mechanism of HACE

The exact mechanism of HACE is unclear. Magnetic resonance imaging of patients with the condition demonstrates cerebral edema primarily localized to the corpus callosum.11 These findings suggest an increased permeability in the blood-brain barrier, leading to vasogenic cerebral edema. Cases of death associated with HACE are the result of herniation. Fortunately, if the condition is recognized promptly and appropriate management is instituted, most patients will recover without permanent deficits.

Current recommendations for treating HACE are similar to treatment strategies for AMS.

Descent. A therapeutic priority, descent may prove challenging as the patient may be ataxic, have altered mental status, and have difficulty facilitating his or her own descent.

Oxygen. A portable HBO bag can be used to simulate descent until evacuation is possible. Supplemental oxygen should be applied immediately.

Dexamethasone. In treating HACE, dexamethasone may be administered at a loading dose of 8 mg, followed by 4 mg every 6 hours.3

Airway Management. If the patient has significantly altered mental status, appropriate airway management must be initiated.

High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema

The most common cause of death from altitude illness is HAPE,12 a form of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. This condition generally occurs at elevations above 3,000 m. Symptoms begin 2 to 5 days after ascent and progress in a typical pattern. A patient will initially experience a nonproductive cough and dyspnea at rest. The dyspnea worsens, and the cough becomes productive of pink, frothy sputum. Without medical intervention, lethargy, coma, and death may follow.

Symptoms of HAPE generally worsen following a night of sleep at elevation. Physical examination reveals crackles, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypoxia. Diagnosis requires at least two of the following signs:

- Crackles or wheezing in at least one lung field

- Central cyanosis

- Tachypnea

- Tachycardia.

In addition to the above signs, at least two of the following symptoms must also be present:

- Dyspnea at rest

- Cough

- Weakness or decreased exercise performance

- Chest tightness

- Congestion.

Mechanism of HAPE

The mechanism of HAPE is better understood than that of AMS and HACE. In HAPE, high microvascular pressures in the lungs lead to elevated pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary artery pressure. Pulmonary edema ensues, but left ventricular function is preserved. Patients with a naturally low HVR, high pulmonary artery pressures at rest, preexisting pulmonary hypertension, or a previous history of HAPE are predisposed to developing the condition. Risk factors include heavy exertion, rapid ascent, cold, salt ingestion, and sleeping medications.

Treatment

Decent and warming of the patient as soon as possible, along with treatment outlined below, are essential.

Oxygen. Treatment of HAPE begins with supplemental oxygen to immediately lower pulmonary artery pressure. Oxygen should initially be administered at 4 to 6 L/min; if the patient improves clinically and can maintain oxygen saturations greater than 90%, oxygen may be decreased with a goal to maintain saturation above 90%.

Nifedipine. Following oxygen, descent, and warming, nifedipine can be used as an adjunctive therapy. The treatment dose for HAPE is 20 to 30 mg of the sustained release form every 12 hours.3

Salmeterol/Albuterol and Expiratory Positive Airway Pressure. The oral inhalers salmeterol or albuterol may be used for bronchodilation; however, there is little evidence to support their effectiveness in HAPE. Ventilation with expiratory positive airway pressure can be employed if available.

Prevention

For patients with a predisposition to HAPE, preventive measures should be considered prior to ascent. As with all forms of altitude illness, gradual ascent is the most effective prevention method available.

Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors act via pulmonary vasodilation to prevent HAPE in some patients. Tadalafil at a dose of 10 mg twice daily or 20 mg once daily has been shown to reduce the incidence of HAPE.14 Alternatively, sildenafil 50 mg three times daily may be used.

Acetazolamide and β-Agonists. Although both acetazolamide and β-agonists such as albuterol have been theorized to aid in preventing HAPE, this has not been proven.15

Conclusion

Clinically, high-altitude illnesses range from subtle symptoms to severe, life threatening disease. Knowledge of these disease processes and clinical presentation prior to travel or work in a high-altitude setting is essential. Rapid recognition of symptoms and prompt, appropriate interventions, such as descent when necessary, can significantly improve the outcomes of these conditions.

Dr Haroutunian is an emergency physician, department of emergency medicine, Exempla St Joseph Hospital, Denver, Colorado. Dr Bono is professor and vice chairman, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

Patients participating in occupational and sports-related activities requiring ascent to high elevations are at risk of developing a range of high-altitude illnesses. Prompt recognition and treatment are paramount to improving outcomes and preventing life-threatening sequelae. High-elevation locations are the setting of many recreational activities for outdoor enthusiasts. As such, illnesses associated with high altitude may be encountered by those summiting peaks, traveling by air, or working in flight medicine or as part of an emergency rescue team. The altitude syndromes discussed in this review are acute mountain sickness (AMS), high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), and high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE). While these conditions do not represent all altitude-related illnesses, they are the primary pathological processes for which physicians should be familiar when working with high-altitude populations.

Physiological Response to Altitude

The Lake Louise Criteria

Acute Mountain Sickness

Acute mountain sickness comprises a constellation of symptoms caused by the atmospheric changes at elevations above approximately 2,500 m. It is the most common form of high-altitude illness, affecting 25% of travelers at moderate altitude and 50% to 85% above 4,000 m.3

Symptoms

The onset of symptoms (eg, headache, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, weakness) may occur at 2,000 m in the setting of rapid ascent—most commonly at 6 to 12 hours, but onset can range from 1 hour to 2 days after ascent. If symptoms begin after 3 days, other diagnoses should be considered. Symptoms of AMS are generally worse after the first night of sleep at elevation. On physical examination, vital signs are usually normal, though postural hypotension and tachycardia are possible. Oxygen saturation may be markedly decreased after rapid ascent, and chest auscultation may reveal rales in 20% of patients.4 Peripheral and facial edema may also be present. Funduscopic examination may show venous tortuosity and dilation, and retinal hemorrhage is common in ascents over 4,800 m.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for AMS is broad and includes hypothermia, dehydration, exhaustion, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracranial mass, carbon monoxide poisoning, alcohol hangover, intoxication, central nervous system infection and migraine. Risk factors for developing AMS are a previous history of altitude illness, rapid ascent, and lack of previous acclimatization. Interestingly, physical fitness does not protect a person from developing AMS.5

Mechanism of AMS

The true mechanism of AMS is uncertain, but it is clear that a fall in barometric pressure results in hypobaric hypoxia. This is thought to lead to an increased blood volume in the brain and increased cerebral blood flow, possibly precipitating an enlarged brain. A mechanism related to vasogenic edema has been proposed due to patients’ clinical improvement with dexamethasone therapy.6 Acute mountain sickness does appear to be related to overall fluid balance, as an increase in reninangiotensin, aldosterone, and antidiuretic hormone has been observed in patients with the condition. Elevation of these hormones is contrary to the appropriate physiological response of diuresis.

Treatment

Treatment of AMS begins with descent from elevation as soon as possible. Descent should be at least 500 m from the aggravating elevation. Patients should remain at least 1 to 2 days at this lower elevation before attempting reascent. If descent is not feasible, any further ascent should be delayed until symptoms have resolved.

Dexamethasone. This glucocorticoid has been used clinically with good success, although the mechanism of action in unclear. The initial dose is 8 mg followed by 4 mg every 6 hours.3

Acetazolamide. A carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, acetazolamide acts to temper symptoms by causing an acidosis that increases ventilation and prevents periodic breathing and hypoxia during sleep. The standard dose is 250 mg twice daily.3

Oxygen. Supplemental oxygen provided at 1 to 2 L/min via nasal cannula for 12 to 24 hours may help to improve symptoms. A portable hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) bag (eg, a Gamow bag) can be used to create an effective altitude of approximately 1,500 to 2,000 m inside the bag. The patient is placed completely within the bag, the zipper is sealed shut, and the bag is inflated with a foot pump. Treatment in such a chamber can be provided in 1-hour increments and repeated as needed. However, if descent is possible, use of the HBO chamber should not prevent or delay descent.

Ibuprofen. Compared to placebo, studies have shown ibuprofen 600 mg three times a day reduces the severity of AMS.7

Prevention

Strategies to prevent AMS are similar to those used to treat the condition. These include gradual ascent and prophylactic drug therapy.

Gradual Ascent. Gradual ascent is the primary strategy to prevent AMS. At altitudes above 3,000 m, each subsequent night should not be spent at an elevation 300 m higher than the previous night.

Acetazolamide. Pretreatment with acetazolamide is indicated for patients with a history of altitude illness or who anticipate an abrupt ascent (eg, rescue workers). Acetazolamide has been shown in multiple studies to be effective in the prevention of AMS.8 Adverse side effects of acetazolamide include paresthesias and increased urinary frequency; the drug may also make carbonated beverages taste flat. The preventive dose is 125 mg twice daily, and should be started the day before ascent.

Dexamethasone. In addition to treating AMS, dexamethasone may be taken as a preventive in doses of 2 mg every 6 hours or 4 mg twice daily.3 However, unlike acetazolamide, which acts to facilitate acclimatization, dexamethasone only prevents symptoms. Thus, cessation of the drug can result in rebound AMS symptoms, and prolonged use can result in adrenal suppression.3 Therefore, it should not be used for more than 10 days.

Sumatriptan and Gabapentin. In recent studies, sumatriptan and gabapentin haven shown benefit in preventing AMS, 9,10 but further study is needed before either of these drugs can be recommended.

Ginkgo Biloba. While ginkgo biloba has been touted as an effective preventive treatment, studies have shown no benefit to its use.8

Ibuprofen. ibuprofen 600 mg three times daily can be initiated the day prior to ascent, and has been shown to decrease the incidence of AMS.7

High-Altitude Cerebral Edema

Mechanism of HACE

The exact mechanism of HACE is unclear. Magnetic resonance imaging of patients with the condition demonstrates cerebral edema primarily localized to the corpus callosum.11 These findings suggest an increased permeability in the blood-brain barrier, leading to vasogenic cerebral edema. Cases of death associated with HACE are the result of herniation. Fortunately, if the condition is recognized promptly and appropriate management is instituted, most patients will recover without permanent deficits.

Current recommendations for treating HACE are similar to treatment strategies for AMS.

Descent. A therapeutic priority, descent may prove challenging as the patient may be ataxic, have altered mental status, and have difficulty facilitating his or her own descent.

Oxygen. A portable HBO bag can be used to simulate descent until evacuation is possible. Supplemental oxygen should be applied immediately.

Dexamethasone. In treating HACE, dexamethasone may be administered at a loading dose of 8 mg, followed by 4 mg every 6 hours.3

Airway Management. If the patient has significantly altered mental status, appropriate airway management must be initiated.

High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema

The most common cause of death from altitude illness is HAPE,12 a form of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. This condition generally occurs at elevations above 3,000 m. Symptoms begin 2 to 5 days after ascent and progress in a typical pattern. A patient will initially experience a nonproductive cough and dyspnea at rest. The dyspnea worsens, and the cough becomes productive of pink, frothy sputum. Without medical intervention, lethargy, coma, and death may follow.

Symptoms of HAPE generally worsen following a night of sleep at elevation. Physical examination reveals crackles, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypoxia. Diagnosis requires at least two of the following signs:

- Crackles or wheezing in at least one lung field

- Central cyanosis

- Tachypnea

- Tachycardia.

In addition to the above signs, at least two of the following symptoms must also be present:

- Dyspnea at rest

- Cough

- Weakness or decreased exercise performance

- Chest tightness

- Congestion.

Mechanism of HAPE

The mechanism of HAPE is better understood than that of AMS and HACE. In HAPE, high microvascular pressures in the lungs lead to elevated pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary artery pressure. Pulmonary edema ensues, but left ventricular function is preserved. Patients with a naturally low HVR, high pulmonary artery pressures at rest, preexisting pulmonary hypertension, or a previous history of HAPE are predisposed to developing the condition. Risk factors include heavy exertion, rapid ascent, cold, salt ingestion, and sleeping medications.

Treatment

Decent and warming of the patient as soon as possible, along with treatment outlined below, are essential.

Oxygen. Treatment of HAPE begins with supplemental oxygen to immediately lower pulmonary artery pressure. Oxygen should initially be administered at 4 to 6 L/min; if the patient improves clinically and can maintain oxygen saturations greater than 90%, oxygen may be decreased with a goal to maintain saturation above 90%.

Nifedipine. Following oxygen, descent, and warming, nifedipine can be used as an adjunctive therapy. The treatment dose for HAPE is 20 to 30 mg of the sustained release form every 12 hours.3

Salmeterol/Albuterol and Expiratory Positive Airway Pressure. The oral inhalers salmeterol or albuterol may be used for bronchodilation; however, there is little evidence to support their effectiveness in HAPE. Ventilation with expiratory positive airway pressure can be employed if available.

Prevention

For patients with a predisposition to HAPE, preventive measures should be considered prior to ascent. As with all forms of altitude illness, gradual ascent is the most effective prevention method available.

Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors act via pulmonary vasodilation to prevent HAPE in some patients. Tadalafil at a dose of 10 mg twice daily or 20 mg once daily has been shown to reduce the incidence of HAPE.14 Alternatively, sildenafil 50 mg three times daily may be used.

Acetazolamide and β-Agonists. Although both acetazolamide and β-agonists such as albuterol have been theorized to aid in preventing HAPE, this has not been proven.15

Conclusion

Clinically, high-altitude illnesses range from subtle symptoms to severe, life threatening disease. Knowledge of these disease processes and clinical presentation prior to travel or work in a high-altitude setting is essential. Rapid recognition of symptoms and prompt, appropriate interventions, such as descent when necessary, can significantly improve the outcomes of these conditions.

Dr Haroutunian is an emergency physician, department of emergency medicine, Exempla St Joseph Hospital, Denver, Colorado. Dr Bono is professor and vice chairman, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

- Hackett PH, Oelz O. The Lake Louise consensus on the definition and qualification of altitude illness. In: Sutton JR, Coates G, Houston CS, eds. Hypoxia and Mountain Medicine. Burlington, VT: Queen City Printers; 1992:327-330.

- Roach RC, Bärtch P, Hackett PH, Oelz O, and the Lake Louise AMS Scoring Consensus Committee. The Lake Louise Acute Mountain Sickness Scoring System. In: Hypoxia and Molecular Medicine. Proceedings of the 8th International Hypoxia Symposium. Burlington, VT: Queen City Printers; 1993:272-274.

- Eide RP 3rd, Asplund CA. Altitude illness: update on prevention and treatment. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11(3):124-130.

- Milzman DP, Damergis JA, Napoli AM. Rapid ascent changes in vitals at altitude. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(4):536.

- Bärtsch P, Swenson ER. Clinical practice: Acute high-altitude illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(24):2294-2302.

- Hackett PH, Roach RC. Medical therapy of mountain illness. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16(9):980-986.

- Lipman GS, Kanaan NC, Holck PS, Constance BB, Gertsch JH; PAINS Group. Ibuprofen prevents altitude illness: a randomized controlled trial for prevention of altitude illness with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(6): 484-490.

- Seupaul RA, Welch JL, Malka ST, Emmett TW. Pharmacologic prophylaxis for acute mountain sickness: a systematic shortcut review. Ann Emerg Med. 2012; 59(4):307-317.

- Jafarian S, Gorouhi F, Salimi S, Lotfi J. Sumatriptan for prevention of acute mountain sickness: randomized clinical trial. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(3):273-277.

- Jafarian S, Abolfazli R, Gorouhi F, Rezaie S, Lotfi J. Gabapentin for prevention of hypobaric hypoxia-induced headache: randomized double-blind clinical trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(3): 321-323.

- Hackett PH, Yarnell PR, Hill R, Reynard K, Heit J, McCormick J. High-altitude cerebral edema evaluated with magnetic resonance imaging: clinical correlation and pathophysiology. JAMA. 1998;280(22):1920-1925.

- Gallagher SA1, Hackett PH. High-altitude illness. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2004;22(2):329-355.

- Fagenholz PJ, Gutman JA, Murray AF, Noble VE, Thomas SH, Harris NS. Chest ultrasonography for the diagnosis and monitoring of high-altitude pulmonary edema. Chest. 2007;131(4): 1013-1018.

- Leshem E1, Caine Y, Rosenberg E, Maaravi Y, Hermesh H, Schwartz E. Tadalafil and acetazolamide versus acetazolamide for the prevention of severe high-altitude illness. J Travel Med. 2012;19(5): 308-310.

- Schoene RB. Illnesses at high altitude. Chest. 2008;134(2):402-416.

- Hackett PH, Oelz O. The Lake Louise consensus on the definition and qualification of altitude illness. In: Sutton JR, Coates G, Houston CS, eds. Hypoxia and Mountain Medicine. Burlington, VT: Queen City Printers; 1992:327-330.

- Roach RC, Bärtch P, Hackett PH, Oelz O, and the Lake Louise AMS Scoring Consensus Committee. The Lake Louise Acute Mountain Sickness Scoring System. In: Hypoxia and Molecular Medicine. Proceedings of the 8th International Hypoxia Symposium. Burlington, VT: Queen City Printers; 1993:272-274.

- Eide RP 3rd, Asplund CA. Altitude illness: update on prevention and treatment. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11(3):124-130.

- Milzman DP, Damergis JA, Napoli AM. Rapid ascent changes in vitals at altitude. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(4):536.

- Bärtsch P, Swenson ER. Clinical practice: Acute high-altitude illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(24):2294-2302.

- Hackett PH, Roach RC. Medical therapy of mountain illness. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16(9):980-986.

- Lipman GS, Kanaan NC, Holck PS, Constance BB, Gertsch JH; PAINS Group. Ibuprofen prevents altitude illness: a randomized controlled trial for prevention of altitude illness with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(6): 484-490.

- Seupaul RA, Welch JL, Malka ST, Emmett TW. Pharmacologic prophylaxis for acute mountain sickness: a systematic shortcut review. Ann Emerg Med. 2012; 59(4):307-317.

- Jafarian S, Gorouhi F, Salimi S, Lotfi J. Sumatriptan for prevention of acute mountain sickness: randomized clinical trial. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(3):273-277.

- Jafarian S, Abolfazli R, Gorouhi F, Rezaie S, Lotfi J. Gabapentin for prevention of hypobaric hypoxia-induced headache: randomized double-blind clinical trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(3): 321-323.

- Hackett PH, Yarnell PR, Hill R, Reynard K, Heit J, McCormick J. High-altitude cerebral edema evaluated with magnetic resonance imaging: clinical correlation and pathophysiology. JAMA. 1998;280(22):1920-1925.

- Gallagher SA1, Hackett PH. High-altitude illness. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2004;22(2):329-355.

- Fagenholz PJ, Gutman JA, Murray AF, Noble VE, Thomas SH, Harris NS. Chest ultrasonography for the diagnosis and monitoring of high-altitude pulmonary edema. Chest. 2007;131(4): 1013-1018.

- Leshem E1, Caine Y, Rosenberg E, Maaravi Y, Hermesh H, Schwartz E. Tadalafil and acetazolamide versus acetazolamide for the prevention of severe high-altitude illness. J Travel Med. 2012;19(5): 308-310.

- Schoene RB. Illnesses at high altitude. Chest. 2008;134(2):402-416.

Emergency Imaging: What is the suspected diagnosis? Is additional imaging necessary, and if so, why?

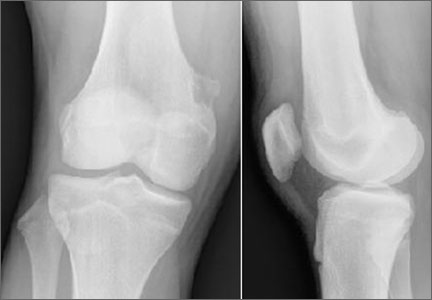

A 25-year-old man with no significant past medical history presented with low-back pain that radiated down into his right thigh. The patient stated the pain began 1 week earlier when he was lifting weights and had increased in severity to the point where he was no longer able to walk or stand up straight. He had taken nonprescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs but received no significant relief.

Radiographs of the lumbosacral spine were obtained; representative anteroposterior (AP) and lateral images are shown above (Figures 1 and 2).

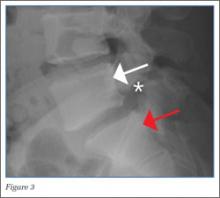

The lateral view of the lumbar spine demonstrates mild anterolisthesis of L5 on S1 with the posterior cortex of L5 (white arrow, Figure 3) anterior to the posterior cortex of S1 (red arrow, Figure 3). Normally, the posterior cortices of the adjacent vertebral bodies should align. Lucency is also noted in the region of the pars interarticularis (white asterisk, Figure 3). The combination of anterolisthesis and this lucency in a young patient suggests the diagnosis of spondylolysis (pars defect).

The pathophysiology of spondylolysis is still uncertain. Two theories have been proposed—underlying dysplastic pars interarticularis versus repetitive microtrauma resulting in stress factors are the two proposed underlying mechanism. If patients are genetically predisposed, underlying dysplasia probably contributes to the pathology, while microtrauma triggers the actual defect.2 Most patients respond well with conservative management.

When evaluating for spondylolysis, AP, lateral, 45-degree right and left oblique views, and collimated lateral views of the lumbosacral spine should be obtained. With this five-view study, up to 96.5% of pars defect can be identified.

In the general population, if spondylolysis is suspected and radiographs are negative, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and/or single-photon emission computed tomography bone scintigraphy can be used for further evaluation.4,5 In this case, the diagnosis was made based on radiographic imaging, and the patient was discharged with a scheduled follow-up with an orthopedic surgeon.

Dr Salama is a resident of radiology, resident of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Belfi is an assistant professor of radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College New York; and an assistant attending radiologist, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Belfi LM, Ortiz AO, Katz DS. Computed tomography evaluation of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in asymptomatic patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(24):E907-E910. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000245947.31473.0a.

- Foreman P, Griessenauer CJ, Watanabe K, et al. L5 spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis: a comprehensive review with an anatomic focus. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(2):209-216. doi:10.1007/s00381-012-1942-2.

- Amato M, Totty WG, Gilula LA. Spondylolysis of the lumbar spine: demonstration of defects and laminal fragmentation. Radiology. 1984;153(3):627-629.

- Saraste H, Nilsson B, Broström LA, et al. Relationship between radiological and clinical variables in spondylolysis. Int Orthop. 1984;8(3):163-174. doi:10.1007/BF00269912.

- Lee JH, Ehara S, Tamakawa Y, Shimamura T. Spondylolysis of the upper lumbar spine: Radiological features. Clin Imaging. 1999;23(6):389-393. doi:10.1016/S0899-7071(99)00158-8.

A 25-year-old man with no significant past medical history presented with low-back pain that radiated down into his right thigh. The patient stated the pain began 1 week earlier when he was lifting weights and had increased in severity to the point where he was no longer able to walk or stand up straight. He had taken nonprescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs but received no significant relief.

Radiographs of the lumbosacral spine were obtained; representative anteroposterior (AP) and lateral images are shown above (Figures 1 and 2).

The lateral view of the lumbar spine demonstrates mild anterolisthesis of L5 on S1 with the posterior cortex of L5 (white arrow, Figure 3) anterior to the posterior cortex of S1 (red arrow, Figure 3). Normally, the posterior cortices of the adjacent vertebral bodies should align. Lucency is also noted in the region of the pars interarticularis (white asterisk, Figure 3). The combination of anterolisthesis and this lucency in a young patient suggests the diagnosis of spondylolysis (pars defect).

The pathophysiology of spondylolysis is still uncertain. Two theories have been proposed—underlying dysplastic pars interarticularis versus repetitive microtrauma resulting in stress factors are the two proposed underlying mechanism. If patients are genetically predisposed, underlying dysplasia probably contributes to the pathology, while microtrauma triggers the actual defect.2 Most patients respond well with conservative management.

When evaluating for spondylolysis, AP, lateral, 45-degree right and left oblique views, and collimated lateral views of the lumbosacral spine should be obtained. With this five-view study, up to 96.5% of pars defect can be identified.

In the general population, if spondylolysis is suspected and radiographs are negative, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and/or single-photon emission computed tomography bone scintigraphy can be used for further evaluation.4,5 In this case, the diagnosis was made based on radiographic imaging, and the patient was discharged with a scheduled follow-up with an orthopedic surgeon.

Dr Salama is a resident of radiology, resident of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Belfi is an assistant professor of radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College New York; and an assistant attending radiologist, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

A 25-year-old man with no significant past medical history presented with low-back pain that radiated down into his right thigh. The patient stated the pain began 1 week earlier when he was lifting weights and had increased in severity to the point where he was no longer able to walk or stand up straight. He had taken nonprescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs but received no significant relief.

Radiographs of the lumbosacral spine were obtained; representative anteroposterior (AP) and lateral images are shown above (Figures 1 and 2).

The lateral view of the lumbar spine demonstrates mild anterolisthesis of L5 on S1 with the posterior cortex of L5 (white arrow, Figure 3) anterior to the posterior cortex of S1 (red arrow, Figure 3). Normally, the posterior cortices of the adjacent vertebral bodies should align. Lucency is also noted in the region of the pars interarticularis (white asterisk, Figure 3). The combination of anterolisthesis and this lucency in a young patient suggests the diagnosis of spondylolysis (pars defect).

The pathophysiology of spondylolysis is still uncertain. Two theories have been proposed—underlying dysplastic pars interarticularis versus repetitive microtrauma resulting in stress factors are the two proposed underlying mechanism. If patients are genetically predisposed, underlying dysplasia probably contributes to the pathology, while microtrauma triggers the actual defect.2 Most patients respond well with conservative management.

When evaluating for spondylolysis, AP, lateral, 45-degree right and left oblique views, and collimated lateral views of the lumbosacral spine should be obtained. With this five-view study, up to 96.5% of pars defect can be identified.

In the general population, if spondylolysis is suspected and radiographs are negative, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and/or single-photon emission computed tomography bone scintigraphy can be used for further evaluation.4,5 In this case, the diagnosis was made based on radiographic imaging, and the patient was discharged with a scheduled follow-up with an orthopedic surgeon.

Dr Salama is a resident of radiology, resident of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Belfi is an assistant professor of radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College New York; and an assistant attending radiologist, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Belfi LM, Ortiz AO, Katz DS. Computed tomography evaluation of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in asymptomatic patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(24):E907-E910. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000245947.31473.0a.

- Foreman P, Griessenauer CJ, Watanabe K, et al. L5 spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis: a comprehensive review with an anatomic focus. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(2):209-216. doi:10.1007/s00381-012-1942-2.

- Amato M, Totty WG, Gilula LA. Spondylolysis of the lumbar spine: demonstration of defects and laminal fragmentation. Radiology. 1984;153(3):627-629.

- Saraste H, Nilsson B, Broström LA, et al. Relationship between radiological and clinical variables in spondylolysis. Int Orthop. 1984;8(3):163-174. doi:10.1007/BF00269912.

- Lee JH, Ehara S, Tamakawa Y, Shimamura T. Spondylolysis of the upper lumbar spine: Radiological features. Clin Imaging. 1999;23(6):389-393. doi:10.1016/S0899-7071(99)00158-8.

- Belfi LM, Ortiz AO, Katz DS. Computed tomography evaluation of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in asymptomatic patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(24):E907-E910. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000245947.31473.0a.

- Foreman P, Griessenauer CJ, Watanabe K, et al. L5 spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis: a comprehensive review with an anatomic focus. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(2):209-216. doi:10.1007/s00381-012-1942-2.

- Amato M, Totty WG, Gilula LA. Spondylolysis of the lumbar spine: demonstration of defects and laminal fragmentation. Radiology. 1984;153(3):627-629.

- Saraste H, Nilsson B, Broström LA, et al. Relationship between radiological and clinical variables in spondylolysis. Int Orthop. 1984;8(3):163-174. doi:10.1007/BF00269912.

- Lee JH, Ehara S, Tamakawa Y, Shimamura T. Spondylolysis of the upper lumbar spine: Radiological features. Clin Imaging. 1999;23(6):389-393. doi:10.1016/S0899-7071(99)00158-8.

Case Report: Headache in a Postpartum Patient With Essential Thrombocytosis

Case

At presentation, the patient was in no apparent distress and had normal vital signs, including normal blood pressure. On physical examination, she was alert and oriented, with unremarkable head, neck, fundoscopic, cardiac, pulmonary, skin, and neurological examinations. Laboratory results were only notable for a platelet count of 677 x 109/L. The remainder of the complete blood count, chemistry, and coagulation panels was all within normal limits. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the brain was unremarkable. She was treated symptomatically with ketorolac, diphenhydramine, and metoclopramide, but received no relief.

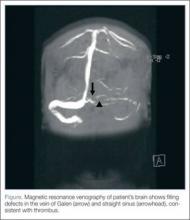

Based on the patient’s history of ET and postpartum state, there was a high suspicion for cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). Magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance venography (MRI/MRV) of the brain was obtained, which revealed near-complete thrombosis of the vein of Galen and straight sinus (Figure). Neurology and hematology services were consulted emergently, and the patient was started on a heparin drip and admitted to the neurosurgical intensive care unit. Hydroxyurea was also given for cytoreduction, and platelets normalized to 305 x 109/L within 1 day of treatment. The patient’s neurological examination remained nonfocal, her headache gradually resolved, and she was discharged on hospital day 3 on oral anticoagulants.

Discussion

Essential thrombocytosis is a chronic myeloproliferative disorder characterized by clonal proliferation of the megakaryocyte cell line due to a defect in a pluripotent hematopoietic stem cell.1 The estimated annual incidence is 2.5 per 100,000 individuals.2 It affects patients of both genders, most commonly between ages 50 to 70 years.3

Up to 25% of patients with ET experience neurological complications, mainly occlusive strokes, chronic headache, and dizziness.4 Since pregnancy also increases thrombogenicity, and CVT occurs in 12 per 100,000 deliveries,5 it should be considered in any pregnant or postpartum patient with neurological symptoms.

Diagnosis of ET

Essential thrombocytosis is a diagnosis of exclusion, and no clinical or laboratory finding is diagnostic.1 Although patients with ET are at increased risk for bleeding, these events usually involve mucosal and cutaneous sites and are clinically insignificant. Thrombotic complications account for the majority of the morbidity and mortality associated with ET and can be both arterial and venous. In one case series, roughly 50% patients with ET experienced a thrombotic event within 9 years from diagnosis.6 Thrombotic complications are seen most commonly in patients younger than age 55 years at diagnosis. Common sites of thrombosis include the deep veins of the lower extremities, pulmonary vessels, hepatic vein, portal vein, digital microvasculature, and placenta.1

Despite the high rate of thrombotic complications in ET, there is little data on neurological complications and few reports of CVT in patients with ET.7-9 In one chart review of 70 patients with ET, researchers identified 18 patients who developed neurological complications,4 the most common of which was cerebrovascular accident/transient ischemic attack. Only one patient in the series had a CVT. The majority of patients with neurological events were female and no clinical or laboratory parameter predicted the risk of neurological event.

Thrombocytosis

Thrombocytosis is classified as either primary/essential or secondary/reactive. The majority of thrombocytosis is secondary/reactive and is caused by a variety of inflammatory conditions, such as infection and malignancy. Unlike ET, secondary thrombocytosis is not associated with any bleeding or thrombotic complications and does not require direct treatment.1

Treatment of ET

The decision to treat ET is based on clinical parameters and is usually reserved for patients at high-risk of thrombosis, including those with history of thrombosis or platelets >1,500 x 109/L.1 The first-line agent for treatment of essential thrombocytosis, hydroxyurea has been shown to decrease thrombotic episodes.10 Other cytoreductive agents include anagrilide and interferon-α, the use of which is considered safe in pregnancy.1

Cerebral Venous Thrombosis

Cerebral venous thrombosis is a rare but potentially fatal condition. Patients may present with headache (95%), seizures (47%), and vision changes (41%), and may or may not have focal or generalized neurological deficits.11 Thrombosis can lead to venous obstruction, resulting in increased intracranial pressure and ultimately cerebral herniation and death. Predisposing risk factors for CVT include thrombophilic and procoagulant disorders, maxillofacial infections, trauma, malignancy, and vasculitides. Among female patients with CVT, studies show approximately 50% were on oral contraceptives and 20% were pregnant or in the postpartum period at the time of the event. Nearly half of patients with CVT have multiple risk factors.12

Diagnosis of CVT

Diagnosis of CVT requires a high clinical suspicion. Lumbar puncture usually reveals high opening pressure with normal cerebrospinal fluid analysis.13 The classic finding of CVT on a contrast-enhanced CT scan is the “empty delta sign,” which is a central hypointensity within the superior sagittal sinus secondary due to slow/absent flow surrounded by contrast enhancement in a triangular shape. An ischemic infarction crossing arterial boundaries or near a venous sinus—with or without a hemorrhagic component—is also suggestive of CVT. However, CT scans are read as normal or indeterminate in up to 30% patients.14 Moreover, while CT venography may visualize the cerebral venous system, there is a false-negative rate of 25%.15 Therefore, MRI with MRV is the gold standard for diagnosis.

Pregnancy and CVT

As previously noted, pregnant or postpartum patients are at an increased risk of developing CVT. During pregnancy, decreased levels of protein S inhibitors and increased levels of fibrinogen, clotting factors, and protein C inhibitors lead to increased thrombogenicity.16 Older maternal age, pregnancy-related hypertension, peripartum infections, and cesarean delivery also increase the risk of CVT.16

Patients with CVT associated with pregnancy have more acute onset of symptoms and neurological findings, and 2% to 10% less mortality than patients with CVT secondary to other etiologies. Cerebral venous thrombosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any pregnant or postpartum patient presenting with neurological symptoms.

Treatment of CVT

Regardless of underlying etiology or symptom duration, all patients with CVT should receive anticoagulation therapy. Unfractionated or low-molecular weight heparin has been shown to decrease thrombus propagation, increase the rate of recanalization, and improve long-term outcomes—even in the presence of intracranial hemorrhage.17 In the 30% to 40% of patients with CVT who present with intracranial hemorrhage, anticoagulation decreases mortality and is not associated with new or enlarged bleeding.17-19 Patients who continue to deteriorate despite anticoagulation therapy may benefit from endovascular thrombolysis or decompressive hemicraniectomy.20 In a study of patients with CVT, 80% had full recovery, 6% had minor disability, and 14% had a poor outcome.12

Conclusion

This case describes a patient with two risk factors for CVT, a life-threatening condition. It should be considered in patients with ET and/or pregnant and postpartum patients presenting with headache or other neurological symptoms. Magnetic resonance venography is the diagnostic imaging of choice as the CVT may not be visible on CT. All patients with thrombosis and ET should receive anticoagulation therapy and hydroxyurea to prevent cerebral herniation and death.

Dr Canders is a resident, department of emergency medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr Taira is a clinical assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Los Angeles County Hospital/University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Disclosure: The authors report no financial disclosures or conflicts of interests related to this article.

- Schafer AI. Thrombocytosis and thrombocythemia. Blood Rev. 2001;15(4):159-166.

- Mesa RA, Silverstein MN, Jacobsen SJ, Wollan PC, Tefferi A. Population-based incidence and survival figures in essential thrombocythemia and agnogenic myeloid metaplasia: an Olmsted County Study, 1976-1995. Am J Hematol. 1999;61():10-15.

- Tefferi A. Recent progress in the pathogenesis and management of essential thrombocythemia. Leuk Res. 2001;25(5):369-377.

- Kesler A, Ellis MH, Manor Y, Gadoth N, Lishner M. Neurological complications of essential thrombocytosis (ET). Acta Neurol Scand. 2000;102(5):299-302.

- Cantú C, Barinagarrementeria F. Cerebral venous thrombosis associated with pregnancy and puerperium: Review of 67 cases. Stroke. 1993;24(12):1880-1884.

- Bazzan M, Tamponi G, Schinco P, Vaccarino A, Foli C, Gallone G, et al. Thrombosis-free survival and life expectancy in 187 consecutive patients with essential thrombocythemia. Ann Hematol. 1999;78(12):539-543.

- Walther EU, Tiecks FP, Haberl RL. Cranial sinus thrombosis associated with essential thrombocythemia followed by heparin-associated thrombocytopenia. Neurology. 1996;47(1):300-301.

- McDonald TD, Tatemichi TK, Kranzler SJ, Chi L, Hilal SK, Mohr JP. Thrombosis of the superior sagittal sinus associated with essential thrombocytosis followed by MRI during anticoagulant therapy. Neurology. 1989;39(11):1554-1555.

- Iob I, Scanarini M, Andrioli GC, Pardatscher K. Thrombosis of the superior sagittal sinus associated with idiopathic thrombocytosis. Surg Neurol. 1979;11(6):439-41.

- Cortelazzo S, Finazzi G, Ruggeri M, Vestri O, Galli M, Rodeghiero F, et al. Hydroxyurea for patients with essential thrombocythemia and a high risk of thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(17):1132-1136.

- de Bruijn SF, de Haan RJ, Stam J. Clinical features and prognostic factors of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in a prospective series of 59 patients. For The Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Study Group. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70(1):105-108.

- Ferro JM, Canhão P, Stam J, Bousser MG, Barinagarrementeria F; ISCVT Investigators. Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke. 2004;35(3):664-670.

- DeLashaw MR, Vizioli TL, Jr, Counselman FL. Headache and seizure in a young woman postpartum. J Emerg Med. 2005;29(3):289-293.

- Bousser MG. Cerebral venous thrombosis: diagnosis and management. J Neurol. 2000;247(4):252-258.

- Grover M. Cerebral venous thrombosis as a cause of acute headache. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17(4):295-298.

- Martinelli I, Sacchi E, Landi G, Taioli E, Duca F, Mannucci PM. High risk of cerebral venous thrombosis in carriers of prothrombic-gene mutation and in users of oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1988;338(25):1793-1797.

- Star M, Flaster M. Advances and controversies in the management of cerebral venous thrombosis. Neurol Clin. 2013;31(3):765-783.

- Einhäupl KM, Villringer A, Meister W, Mehraein S, Garner C, Pellkofer M, et al. Heparin treatment in sinus venous thrombosis. Lancet. 1991;338(8767):597-600.

- Preter M, Tzourio C, Ameri A, Bousser MG. Long-term prognosis in cerebral venous thrombosis: follow-up of 77 patients. Stroke 1996;27(2):243-246.

- Coutinho JM, Stam J. How to treat cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(5):877-883.

Case

At presentation, the patient was in no apparent distress and had normal vital signs, including normal blood pressure. On physical examination, she was alert and oriented, with unremarkable head, neck, fundoscopic, cardiac, pulmonary, skin, and neurological examinations. Laboratory results were only notable for a platelet count of 677 x 109/L. The remainder of the complete blood count, chemistry, and coagulation panels was all within normal limits. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the brain was unremarkable. She was treated symptomatically with ketorolac, diphenhydramine, and metoclopramide, but received no relief.

Based on the patient’s history of ET and postpartum state, there was a high suspicion for cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). Magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance venography (MRI/MRV) of the brain was obtained, which revealed near-complete thrombosis of the vein of Galen and straight sinus (Figure). Neurology and hematology services were consulted emergently, and the patient was started on a heparin drip and admitted to the neurosurgical intensive care unit. Hydroxyurea was also given for cytoreduction, and platelets normalized to 305 x 109/L within 1 day of treatment. The patient’s neurological examination remained nonfocal, her headache gradually resolved, and she was discharged on hospital day 3 on oral anticoagulants.

Discussion

Essential thrombocytosis is a chronic myeloproliferative disorder characterized by clonal proliferation of the megakaryocyte cell line due to a defect in a pluripotent hematopoietic stem cell.1 The estimated annual incidence is 2.5 per 100,000 individuals.2 It affects patients of both genders, most commonly between ages 50 to 70 years.3

Up to 25% of patients with ET experience neurological complications, mainly occlusive strokes, chronic headache, and dizziness.4 Since pregnancy also increases thrombogenicity, and CVT occurs in 12 per 100,000 deliveries,5 it should be considered in any pregnant or postpartum patient with neurological symptoms.

Diagnosis of ET

Essential thrombocytosis is a diagnosis of exclusion, and no clinical or laboratory finding is diagnostic.1 Although patients with ET are at increased risk for bleeding, these events usually involve mucosal and cutaneous sites and are clinically insignificant. Thrombotic complications account for the majority of the morbidity and mortality associated with ET and can be both arterial and venous. In one case series, roughly 50% patients with ET experienced a thrombotic event within 9 years from diagnosis.6 Thrombotic complications are seen most commonly in patients younger than age 55 years at diagnosis. Common sites of thrombosis include the deep veins of the lower extremities, pulmonary vessels, hepatic vein, portal vein, digital microvasculature, and placenta.1

Despite the high rate of thrombotic complications in ET, there is little data on neurological complications and few reports of CVT in patients with ET.7-9 In one chart review of 70 patients with ET, researchers identified 18 patients who developed neurological complications,4 the most common of which was cerebrovascular accident/transient ischemic attack. Only one patient in the series had a CVT. The majority of patients with neurological events were female and no clinical or laboratory parameter predicted the risk of neurological event.

Thrombocytosis

Thrombocytosis is classified as either primary/essential or secondary/reactive. The majority of thrombocytosis is secondary/reactive and is caused by a variety of inflammatory conditions, such as infection and malignancy. Unlike ET, secondary thrombocytosis is not associated with any bleeding or thrombotic complications and does not require direct treatment.1

Treatment of ET

The decision to treat ET is based on clinical parameters and is usually reserved for patients at high-risk of thrombosis, including those with history of thrombosis or platelets >1,500 x 109/L.1 The first-line agent for treatment of essential thrombocytosis, hydroxyurea has been shown to decrease thrombotic episodes.10 Other cytoreductive agents include anagrilide and interferon-α, the use of which is considered safe in pregnancy.1

Cerebral Venous Thrombosis

Cerebral venous thrombosis is a rare but potentially fatal condition. Patients may present with headache (95%), seizures (47%), and vision changes (41%), and may or may not have focal or generalized neurological deficits.11 Thrombosis can lead to venous obstruction, resulting in increased intracranial pressure and ultimately cerebral herniation and death. Predisposing risk factors for CVT include thrombophilic and procoagulant disorders, maxillofacial infections, trauma, malignancy, and vasculitides. Among female patients with CVT, studies show approximately 50% were on oral contraceptives and 20% were pregnant or in the postpartum period at the time of the event. Nearly half of patients with CVT have multiple risk factors.12

Diagnosis of CVT

Diagnosis of CVT requires a high clinical suspicion. Lumbar puncture usually reveals high opening pressure with normal cerebrospinal fluid analysis.13 The classic finding of CVT on a contrast-enhanced CT scan is the “empty delta sign,” which is a central hypointensity within the superior sagittal sinus secondary due to slow/absent flow surrounded by contrast enhancement in a triangular shape. An ischemic infarction crossing arterial boundaries or near a venous sinus—with or without a hemorrhagic component—is also suggestive of CVT. However, CT scans are read as normal or indeterminate in up to 30% patients.14 Moreover, while CT venography may visualize the cerebral venous system, there is a false-negative rate of 25%.15 Therefore, MRI with MRV is the gold standard for diagnosis.

Pregnancy and CVT

As previously noted, pregnant or postpartum patients are at an increased risk of developing CVT. During pregnancy, decreased levels of protein S inhibitors and increased levels of fibrinogen, clotting factors, and protein C inhibitors lead to increased thrombogenicity.16 Older maternal age, pregnancy-related hypertension, peripartum infections, and cesarean delivery also increase the risk of CVT.16

Patients with CVT associated with pregnancy have more acute onset of symptoms and neurological findings, and 2% to 10% less mortality than patients with CVT secondary to other etiologies. Cerebral venous thrombosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any pregnant or postpartum patient presenting with neurological symptoms.

Treatment of CVT

Regardless of underlying etiology or symptom duration, all patients with CVT should receive anticoagulation therapy. Unfractionated or low-molecular weight heparin has been shown to decrease thrombus propagation, increase the rate of recanalization, and improve long-term outcomes—even in the presence of intracranial hemorrhage.17 In the 30% to 40% of patients with CVT who present with intracranial hemorrhage, anticoagulation decreases mortality and is not associated with new or enlarged bleeding.17-19 Patients who continue to deteriorate despite anticoagulation therapy may benefit from endovascular thrombolysis or decompressive hemicraniectomy.20 In a study of patients with CVT, 80% had full recovery, 6% had minor disability, and 14% had a poor outcome.12

Conclusion

This case describes a patient with two risk factors for CVT, a life-threatening condition. It should be considered in patients with ET and/or pregnant and postpartum patients presenting with headache or other neurological symptoms. Magnetic resonance venography is the diagnostic imaging of choice as the CVT may not be visible on CT. All patients with thrombosis and ET should receive anticoagulation therapy and hydroxyurea to prevent cerebral herniation and death.

Dr Canders is a resident, department of emergency medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr Taira is a clinical assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Los Angeles County Hospital/University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Disclosure: The authors report no financial disclosures or conflicts of interests related to this article.

Case

At presentation, the patient was in no apparent distress and had normal vital signs, including normal blood pressure. On physical examination, she was alert and oriented, with unremarkable head, neck, fundoscopic, cardiac, pulmonary, skin, and neurological examinations. Laboratory results were only notable for a platelet count of 677 x 109/L. The remainder of the complete blood count, chemistry, and coagulation panels was all within normal limits. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the brain was unremarkable. She was treated symptomatically with ketorolac, diphenhydramine, and metoclopramide, but received no relief.

Based on the patient’s history of ET and postpartum state, there was a high suspicion for cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). Magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance venography (MRI/MRV) of the brain was obtained, which revealed near-complete thrombosis of the vein of Galen and straight sinus (Figure). Neurology and hematology services were consulted emergently, and the patient was started on a heparin drip and admitted to the neurosurgical intensive care unit. Hydroxyurea was also given for cytoreduction, and platelets normalized to 305 x 109/L within 1 day of treatment. The patient’s neurological examination remained nonfocal, her headache gradually resolved, and she was discharged on hospital day 3 on oral anticoagulants.

Discussion

Essential thrombocytosis is a chronic myeloproliferative disorder characterized by clonal proliferation of the megakaryocyte cell line due to a defect in a pluripotent hematopoietic stem cell.1 The estimated annual incidence is 2.5 per 100,000 individuals.2 It affects patients of both genders, most commonly between ages 50 to 70 years.3

Up to 25% of patients with ET experience neurological complications, mainly occlusive strokes, chronic headache, and dizziness.4 Since pregnancy also increases thrombogenicity, and CVT occurs in 12 per 100,000 deliveries,5 it should be considered in any pregnant or postpartum patient with neurological symptoms.

Diagnosis of ET

Essential thrombocytosis is a diagnosis of exclusion, and no clinical or laboratory finding is diagnostic.1 Although patients with ET are at increased risk for bleeding, these events usually involve mucosal and cutaneous sites and are clinically insignificant. Thrombotic complications account for the majority of the morbidity and mortality associated with ET and can be both arterial and venous. In one case series, roughly 50% patients with ET experienced a thrombotic event within 9 years from diagnosis.6 Thrombotic complications are seen most commonly in patients younger than age 55 years at diagnosis. Common sites of thrombosis include the deep veins of the lower extremities, pulmonary vessels, hepatic vein, portal vein, digital microvasculature, and placenta.1

Despite the high rate of thrombotic complications in ET, there is little data on neurological complications and few reports of CVT in patients with ET.7-9 In one chart review of 70 patients with ET, researchers identified 18 patients who developed neurological complications,4 the most common of which was cerebrovascular accident/transient ischemic attack. Only one patient in the series had a CVT. The majority of patients with neurological events were female and no clinical or laboratory parameter predicted the risk of neurological event.

Thrombocytosis

Thrombocytosis is classified as either primary/essential or secondary/reactive. The majority of thrombocytosis is secondary/reactive and is caused by a variety of inflammatory conditions, such as infection and malignancy. Unlike ET, secondary thrombocytosis is not associated with any bleeding or thrombotic complications and does not require direct treatment.1

Treatment of ET

The decision to treat ET is based on clinical parameters and is usually reserved for patients at high-risk of thrombosis, including those with history of thrombosis or platelets >1,500 x 109/L.1 The first-line agent for treatment of essential thrombocytosis, hydroxyurea has been shown to decrease thrombotic episodes.10 Other cytoreductive agents include anagrilide and interferon-α, the use of which is considered safe in pregnancy.1

Cerebral Venous Thrombosis