User login

Patent foramen ovale and the risk of cryptogenic stroke

The article by Roth and Alli in this issue describes in depth more than 10 years of research that addresses the question, Should we close a patent foramen ovale (PFO) to prevent recurrent cryptogenic stroke?

There is no longer any doubt that PFO can be the pathway for thrombus from the venous circulation to go from the right atrium to the left atrium, bypassing the pulmonary capillary filtration bed, and entering the arterial side to produce a stroke, myocardial infarction, or peripheral embolus. Two questions remain: What should we do to prevent another episode? And is percutaneous closure of a PFO with the current devices preferable to medical therapy?

How much do we know about the risks and benefits of closure of PFO? I maintain that we know a great deal about interatrial shunt and paradoxical embolism as a cause of cryptogenic stroke. Prospective randomized clinical trials now give us data with which we can provide appropriate direction to our patients. Percutaneous closure is no longer an “experimental procedure,” as insurance companies claim. The experiment has been done, and the only issue is how one interprets the data from the randomized clinical trials.

The review by Roth and Alli comprehensively describes the observational studies, as well as the three randomized clinical trials done to determine whether PFO closure is preferable to medical therapy to prevent recurrent stroke in patients who have already had one cryptogenic stroke. If we understand some of the subtleties and differences between the trials, we can reach an appropriate conclusion as to what to recommend to our patients.

A review of 10 reports of transcatheter closure of PFO vs six reports of medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke showed a range of rates of recurrent stroke at 1 year—between 0% and 4.9% for transcatheter closure, and between 3.8% and 12% for medical therapy.1

These numbers are important because they were used to estimate the number of patients that would be necessary to study in a randomized clinical trial to demonstrate a benefit of PFO closure vs medical therapy. Unlike most studies of new devices, the PFO closure trials were done in an environment in which patients could get their PFO closed with other devices that were already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for closure of an atrial septal defect. This ability of patients to obtain PFO closure outside of the trial with an off-label device meant that the patients who agreed to be randomized tended to have lower risk for recurrence than patients studied in the observational populations. From a practical standpoint, this meant that the event rate in the patients who participated in the randomized clinical trials (1.7% per year) was lower than predicted from the observational studies.2,3

Another way of saying this is that the randomized clinical trials were underpowered to answer the question. A common way of dealing with this problem is to combine the results of different studies in a meta-analysis. This makes sense if the studies are assessing the same thing. This is not the case with the PFO closure trials. Although the topic of percutaneous PFO closure vs medical therapy was the same, the devices used were different.

In the CLOSURE trial (Evaluation of the STARFlex Septal Closure System in Patients With a Stroke and/or Transient Ischemic Attack Due to Presumed Paradoxical Embolism Through a Patent Foramen Ovale),3 the device used was the STARFlex, which is no longer produced—and for good reasons. It is not as effective as the Amplatzer or Helex devices in completely closing the right-to-left shunt produced by a PFO. In addition, the CardioSEAL or STARFlex device increases the risk of atrial fibrillation, which was seen in 6% of the treated patients.3 This was the major cause of recurrent stroke in the CLOSURE trial. The CardioSEAL STARFlex device was also more thrombogenic.

In the RESPECT trial (Randomized Evaluation of Recurrent Stroke Comparing PFO Closure to Established Current Standard of Care Treatment),2 which used the Amplatzer PFO closure device, there was no increased incidence of atrial fibrillation in the device group compared with the control group. Therefore, it is not appropriate to combine the results of the CLOSURE trial with the results of the RESPECT trial and PC trial,4 both of which used the Amplatzer device.

Our patients want to know what the potential risks and benefits will be if they get their PFO closed with a specific device. They don’t want to know the average risk between two different devices.

However, if you do a meta-analysis of the RESPECT and PC trials, which used the same Amplatzer PFO occluder device, and combine the number of patients studied to increase the statistical power, then the benefit of PFO closure is significant even with an intention-to-treat analysis. By combining the two studies that assessed the same device, you reach a completely different interpretation than if you do a meta-analysis including the CLOSURE trial, which showed no benefit.

The medical community should not uncritically accept meta-analysis methodology. It is a marvelous case example of how scientific methods can be inappropriately used and two diametrically opposed conclusions reached if the meta-analysis combines two different types of devices vs a meta-analysis of just the Amplatzer device.

If we combine the numbers from the RESPECT and PC trials, there were 23 strokes in 691 patients (3.3%) in the medical groups and 10 strokes in 703 patients (1.4%) who underwent PFO closure. By chi square analysis of this intention-to-treat protocol, PFO closure provides a statistically significant reduction in preventing recurrent stroke (95% confidence interval 0.20–0.89, P = .02).

From the patient’s perspective, what is important is this: If I get my PFO closed with an Amplatzer PFO occluder device, what are the risks of the procedure, and what are the potential benefits compared with medical therapy? We can now answer that question definitively. I tell my patients, “The risks of the procedure are remarkably low (about 1%) in experienced hands, and the benefit is that your risk of recurrent stroke will be reduced 73%2 compared with medical therapy.” In the RESPECT Trial, the as-treated cohort consisted of 958 patients with 21 primary end-point events (5 in the closure group and 16 in the medical-therapy group). The rate of the primary end point was 0.39 events per 100 patient-years in the closure group vs 1.45 events per 100 patient-years in the medical-therapy group (hazard ratio 0.27; 95% confidence interval 0.10–0.75; P = .007).

Not all cryptogenic strokes in people who have a PFO are caused by paradoxical embolism. PFO may be an innocent bystander. In addition, not all people who have a paradoxical embolism will have a recurrent stroke. For example, if a young woman presents with a PFO and stroke, is it possible that she can prevent another stroke just by stopping her birth-control pills and not have her PFO closed? What is the risk of recurrent stroke if she were to become pregnant? We do not know the answers to these questions.

Your patients do not want to wait to find out if they are going to have another stroke. The meta-analysis of the randomized clinical trials for paradoxical embolism demonstrates that the closure devices are safe and effective. The FDA should approve the Amplatzer PFO occluder with an indication to prevent recurrent stroke in patients with PFO and an initial cryptogenic event.

- Khairy P, O’Donnell CP, Landzberg MJ. Transcatheter closure versus medical therapy of patent foramen ovale and presumed paradoxical thromboemboli: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139:753–760.

- Carroll JD, Saver JL, Thaler DE, et al; RESPECT Investigators. Closure of patent foramen ovale versus medical therapy after cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1092–1100.

- Furlan AJ, Reisman M, Massaro J, et al; CLOSURE Investigators. Closure or medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke with patent foramen ovale. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:991–999.

- Meier B, Kalesan B, Mattle HP, et al; PC Trial Investigators. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic embolism. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1083–1091.

The article by Roth and Alli in this issue describes in depth more than 10 years of research that addresses the question, Should we close a patent foramen ovale (PFO) to prevent recurrent cryptogenic stroke?

There is no longer any doubt that PFO can be the pathway for thrombus from the venous circulation to go from the right atrium to the left atrium, bypassing the pulmonary capillary filtration bed, and entering the arterial side to produce a stroke, myocardial infarction, or peripheral embolus. Two questions remain: What should we do to prevent another episode? And is percutaneous closure of a PFO with the current devices preferable to medical therapy?

How much do we know about the risks and benefits of closure of PFO? I maintain that we know a great deal about interatrial shunt and paradoxical embolism as a cause of cryptogenic stroke. Prospective randomized clinical trials now give us data with which we can provide appropriate direction to our patients. Percutaneous closure is no longer an “experimental procedure,” as insurance companies claim. The experiment has been done, and the only issue is how one interprets the data from the randomized clinical trials.

The review by Roth and Alli comprehensively describes the observational studies, as well as the three randomized clinical trials done to determine whether PFO closure is preferable to medical therapy to prevent recurrent stroke in patients who have already had one cryptogenic stroke. If we understand some of the subtleties and differences between the trials, we can reach an appropriate conclusion as to what to recommend to our patients.

A review of 10 reports of transcatheter closure of PFO vs six reports of medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke showed a range of rates of recurrent stroke at 1 year—between 0% and 4.9% for transcatheter closure, and between 3.8% and 12% for medical therapy.1

These numbers are important because they were used to estimate the number of patients that would be necessary to study in a randomized clinical trial to demonstrate a benefit of PFO closure vs medical therapy. Unlike most studies of new devices, the PFO closure trials were done in an environment in which patients could get their PFO closed with other devices that were already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for closure of an atrial septal defect. This ability of patients to obtain PFO closure outside of the trial with an off-label device meant that the patients who agreed to be randomized tended to have lower risk for recurrence than patients studied in the observational populations. From a practical standpoint, this meant that the event rate in the patients who participated in the randomized clinical trials (1.7% per year) was lower than predicted from the observational studies.2,3

Another way of saying this is that the randomized clinical trials were underpowered to answer the question. A common way of dealing with this problem is to combine the results of different studies in a meta-analysis. This makes sense if the studies are assessing the same thing. This is not the case with the PFO closure trials. Although the topic of percutaneous PFO closure vs medical therapy was the same, the devices used were different.

In the CLOSURE trial (Evaluation of the STARFlex Septal Closure System in Patients With a Stroke and/or Transient Ischemic Attack Due to Presumed Paradoxical Embolism Through a Patent Foramen Ovale),3 the device used was the STARFlex, which is no longer produced—and for good reasons. It is not as effective as the Amplatzer or Helex devices in completely closing the right-to-left shunt produced by a PFO. In addition, the CardioSEAL or STARFlex device increases the risk of atrial fibrillation, which was seen in 6% of the treated patients.3 This was the major cause of recurrent stroke in the CLOSURE trial. The CardioSEAL STARFlex device was also more thrombogenic.

In the RESPECT trial (Randomized Evaluation of Recurrent Stroke Comparing PFO Closure to Established Current Standard of Care Treatment),2 which used the Amplatzer PFO closure device, there was no increased incidence of atrial fibrillation in the device group compared with the control group. Therefore, it is not appropriate to combine the results of the CLOSURE trial with the results of the RESPECT trial and PC trial,4 both of which used the Amplatzer device.

Our patients want to know what the potential risks and benefits will be if they get their PFO closed with a specific device. They don’t want to know the average risk between two different devices.

However, if you do a meta-analysis of the RESPECT and PC trials, which used the same Amplatzer PFO occluder device, and combine the number of patients studied to increase the statistical power, then the benefit of PFO closure is significant even with an intention-to-treat analysis. By combining the two studies that assessed the same device, you reach a completely different interpretation than if you do a meta-analysis including the CLOSURE trial, which showed no benefit.

The medical community should not uncritically accept meta-analysis methodology. It is a marvelous case example of how scientific methods can be inappropriately used and two diametrically opposed conclusions reached if the meta-analysis combines two different types of devices vs a meta-analysis of just the Amplatzer device.

If we combine the numbers from the RESPECT and PC trials, there were 23 strokes in 691 patients (3.3%) in the medical groups and 10 strokes in 703 patients (1.4%) who underwent PFO closure. By chi square analysis of this intention-to-treat protocol, PFO closure provides a statistically significant reduction in preventing recurrent stroke (95% confidence interval 0.20–0.89, P = .02).

From the patient’s perspective, what is important is this: If I get my PFO closed with an Amplatzer PFO occluder device, what are the risks of the procedure, and what are the potential benefits compared with medical therapy? We can now answer that question definitively. I tell my patients, “The risks of the procedure are remarkably low (about 1%) in experienced hands, and the benefit is that your risk of recurrent stroke will be reduced 73%2 compared with medical therapy.” In the RESPECT Trial, the as-treated cohort consisted of 958 patients with 21 primary end-point events (5 in the closure group and 16 in the medical-therapy group). The rate of the primary end point was 0.39 events per 100 patient-years in the closure group vs 1.45 events per 100 patient-years in the medical-therapy group (hazard ratio 0.27; 95% confidence interval 0.10–0.75; P = .007).

Not all cryptogenic strokes in people who have a PFO are caused by paradoxical embolism. PFO may be an innocent bystander. In addition, not all people who have a paradoxical embolism will have a recurrent stroke. For example, if a young woman presents with a PFO and stroke, is it possible that she can prevent another stroke just by stopping her birth-control pills and not have her PFO closed? What is the risk of recurrent stroke if she were to become pregnant? We do not know the answers to these questions.

Your patients do not want to wait to find out if they are going to have another stroke. The meta-analysis of the randomized clinical trials for paradoxical embolism demonstrates that the closure devices are safe and effective. The FDA should approve the Amplatzer PFO occluder with an indication to prevent recurrent stroke in patients with PFO and an initial cryptogenic event.

The article by Roth and Alli in this issue describes in depth more than 10 years of research that addresses the question, Should we close a patent foramen ovale (PFO) to prevent recurrent cryptogenic stroke?

There is no longer any doubt that PFO can be the pathway for thrombus from the venous circulation to go from the right atrium to the left atrium, bypassing the pulmonary capillary filtration bed, and entering the arterial side to produce a stroke, myocardial infarction, or peripheral embolus. Two questions remain: What should we do to prevent another episode? And is percutaneous closure of a PFO with the current devices preferable to medical therapy?

How much do we know about the risks and benefits of closure of PFO? I maintain that we know a great deal about interatrial shunt and paradoxical embolism as a cause of cryptogenic stroke. Prospective randomized clinical trials now give us data with which we can provide appropriate direction to our patients. Percutaneous closure is no longer an “experimental procedure,” as insurance companies claim. The experiment has been done, and the only issue is how one interprets the data from the randomized clinical trials.

The review by Roth and Alli comprehensively describes the observational studies, as well as the three randomized clinical trials done to determine whether PFO closure is preferable to medical therapy to prevent recurrent stroke in patients who have already had one cryptogenic stroke. If we understand some of the subtleties and differences between the trials, we can reach an appropriate conclusion as to what to recommend to our patients.

A review of 10 reports of transcatheter closure of PFO vs six reports of medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke showed a range of rates of recurrent stroke at 1 year—between 0% and 4.9% for transcatheter closure, and between 3.8% and 12% for medical therapy.1

These numbers are important because they were used to estimate the number of patients that would be necessary to study in a randomized clinical trial to demonstrate a benefit of PFO closure vs medical therapy. Unlike most studies of new devices, the PFO closure trials were done in an environment in which patients could get their PFO closed with other devices that were already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for closure of an atrial septal defect. This ability of patients to obtain PFO closure outside of the trial with an off-label device meant that the patients who agreed to be randomized tended to have lower risk for recurrence than patients studied in the observational populations. From a practical standpoint, this meant that the event rate in the patients who participated in the randomized clinical trials (1.7% per year) was lower than predicted from the observational studies.2,3

Another way of saying this is that the randomized clinical trials were underpowered to answer the question. A common way of dealing with this problem is to combine the results of different studies in a meta-analysis. This makes sense if the studies are assessing the same thing. This is not the case with the PFO closure trials. Although the topic of percutaneous PFO closure vs medical therapy was the same, the devices used were different.

In the CLOSURE trial (Evaluation of the STARFlex Septal Closure System in Patients With a Stroke and/or Transient Ischemic Attack Due to Presumed Paradoxical Embolism Through a Patent Foramen Ovale),3 the device used was the STARFlex, which is no longer produced—and for good reasons. It is not as effective as the Amplatzer or Helex devices in completely closing the right-to-left shunt produced by a PFO. In addition, the CardioSEAL or STARFlex device increases the risk of atrial fibrillation, which was seen in 6% of the treated patients.3 This was the major cause of recurrent stroke in the CLOSURE trial. The CardioSEAL STARFlex device was also more thrombogenic.

In the RESPECT trial (Randomized Evaluation of Recurrent Stroke Comparing PFO Closure to Established Current Standard of Care Treatment),2 which used the Amplatzer PFO closure device, there was no increased incidence of atrial fibrillation in the device group compared with the control group. Therefore, it is not appropriate to combine the results of the CLOSURE trial with the results of the RESPECT trial and PC trial,4 both of which used the Amplatzer device.

Our patients want to know what the potential risks and benefits will be if they get their PFO closed with a specific device. They don’t want to know the average risk between two different devices.

However, if you do a meta-analysis of the RESPECT and PC trials, which used the same Amplatzer PFO occluder device, and combine the number of patients studied to increase the statistical power, then the benefit of PFO closure is significant even with an intention-to-treat analysis. By combining the two studies that assessed the same device, you reach a completely different interpretation than if you do a meta-analysis including the CLOSURE trial, which showed no benefit.

The medical community should not uncritically accept meta-analysis methodology. It is a marvelous case example of how scientific methods can be inappropriately used and two diametrically opposed conclusions reached if the meta-analysis combines two different types of devices vs a meta-analysis of just the Amplatzer device.

If we combine the numbers from the RESPECT and PC trials, there were 23 strokes in 691 patients (3.3%) in the medical groups and 10 strokes in 703 patients (1.4%) who underwent PFO closure. By chi square analysis of this intention-to-treat protocol, PFO closure provides a statistically significant reduction in preventing recurrent stroke (95% confidence interval 0.20–0.89, P = .02).

From the patient’s perspective, what is important is this: If I get my PFO closed with an Amplatzer PFO occluder device, what are the risks of the procedure, and what are the potential benefits compared with medical therapy? We can now answer that question definitively. I tell my patients, “The risks of the procedure are remarkably low (about 1%) in experienced hands, and the benefit is that your risk of recurrent stroke will be reduced 73%2 compared with medical therapy.” In the RESPECT Trial, the as-treated cohort consisted of 958 patients with 21 primary end-point events (5 in the closure group and 16 in the medical-therapy group). The rate of the primary end point was 0.39 events per 100 patient-years in the closure group vs 1.45 events per 100 patient-years in the medical-therapy group (hazard ratio 0.27; 95% confidence interval 0.10–0.75; P = .007).

Not all cryptogenic strokes in people who have a PFO are caused by paradoxical embolism. PFO may be an innocent bystander. In addition, not all people who have a paradoxical embolism will have a recurrent stroke. For example, if a young woman presents with a PFO and stroke, is it possible that she can prevent another stroke just by stopping her birth-control pills and not have her PFO closed? What is the risk of recurrent stroke if she were to become pregnant? We do not know the answers to these questions.

Your patients do not want to wait to find out if they are going to have another stroke. The meta-analysis of the randomized clinical trials for paradoxical embolism demonstrates that the closure devices are safe and effective. The FDA should approve the Amplatzer PFO occluder with an indication to prevent recurrent stroke in patients with PFO and an initial cryptogenic event.

- Khairy P, O’Donnell CP, Landzberg MJ. Transcatheter closure versus medical therapy of patent foramen ovale and presumed paradoxical thromboemboli: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139:753–760.

- Carroll JD, Saver JL, Thaler DE, et al; RESPECT Investigators. Closure of patent foramen ovale versus medical therapy after cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1092–1100.

- Furlan AJ, Reisman M, Massaro J, et al; CLOSURE Investigators. Closure or medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke with patent foramen ovale. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:991–999.

- Meier B, Kalesan B, Mattle HP, et al; PC Trial Investigators. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic embolism. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1083–1091.

- Khairy P, O’Donnell CP, Landzberg MJ. Transcatheter closure versus medical therapy of patent foramen ovale and presumed paradoxical thromboemboli: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139:753–760.

- Carroll JD, Saver JL, Thaler DE, et al; RESPECT Investigators. Closure of patent foramen ovale versus medical therapy after cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1092–1100.

- Furlan AJ, Reisman M, Massaro J, et al; CLOSURE Investigators. Closure or medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke with patent foramen ovale. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:991–999.

- Meier B, Kalesan B, Mattle HP, et al; PC Trial Investigators. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic embolism. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1083–1091.

Double trouble: Simultaneous complications of therapeutic thoracentesis

A 51-year-old man with end-stage liver disease from alcohol abuse presented with worsening dyspnea on exertion. He had a history of ascites requiring diuretic therapy and intermittent paracentesis, as well as symptomatic hepatic hydrothorax requiring thoracentesis. Chest radiography showed a large right hydrothorax (Figure 1).

The patient underwent high-volume thoracentesis, and 3.2 L of clear fluid was removed. Chest radiography after the procedure revealed a right-sided pneumothorax (Figure 2, arrow). The patient was mildly short of breath and was treated with high-flow oxygen. Later the same day, his shortness of breath worsened, and repeat chest radiography showed an unchanged pneumothorax that was now complicated by reexpansion pulmonary edema after thoracentesis (Figure 3, star). The reexpansion pulmonary edema resolved by the following day, and the pneumothorax resolved after placement of a pig-tail catheter into the pleural space (Figure 4).

Iatrogenic pneumothorax after thoracentesis occurs in 6% of cases.1 Iatrogenic reexpansion pulmonary edema after thoracentesis occurs in fewer than 1% of cases.2,3 Simultaneous pneumothorax and reexpansion pulmonary edema arising from the same procedure appears to be extremely rare.

- Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman D, Balk EM, Smetana GW. Pneumothorax following thoracentesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170:332–339.

- Ragozzino MW, Greene R. Bilateral reexpansion pulmonary edema following unilateral pleurocentesis. Chest 1991; 99:506–508.

- Dias OM, Teixeira LR, Vargas FS. Reexpansion pulmonary edema after therapeutic thoracentesis. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2010; 65:1387–1389.

A 51-year-old man with end-stage liver disease from alcohol abuse presented with worsening dyspnea on exertion. He had a history of ascites requiring diuretic therapy and intermittent paracentesis, as well as symptomatic hepatic hydrothorax requiring thoracentesis. Chest radiography showed a large right hydrothorax (Figure 1).

The patient underwent high-volume thoracentesis, and 3.2 L of clear fluid was removed. Chest radiography after the procedure revealed a right-sided pneumothorax (Figure 2, arrow). The patient was mildly short of breath and was treated with high-flow oxygen. Later the same day, his shortness of breath worsened, and repeat chest radiography showed an unchanged pneumothorax that was now complicated by reexpansion pulmonary edema after thoracentesis (Figure 3, star). The reexpansion pulmonary edema resolved by the following day, and the pneumothorax resolved after placement of a pig-tail catheter into the pleural space (Figure 4).

Iatrogenic pneumothorax after thoracentesis occurs in 6% of cases.1 Iatrogenic reexpansion pulmonary edema after thoracentesis occurs in fewer than 1% of cases.2,3 Simultaneous pneumothorax and reexpansion pulmonary edema arising from the same procedure appears to be extremely rare.

A 51-year-old man with end-stage liver disease from alcohol abuse presented with worsening dyspnea on exertion. He had a history of ascites requiring diuretic therapy and intermittent paracentesis, as well as symptomatic hepatic hydrothorax requiring thoracentesis. Chest radiography showed a large right hydrothorax (Figure 1).

The patient underwent high-volume thoracentesis, and 3.2 L of clear fluid was removed. Chest radiography after the procedure revealed a right-sided pneumothorax (Figure 2, arrow). The patient was mildly short of breath and was treated with high-flow oxygen. Later the same day, his shortness of breath worsened, and repeat chest radiography showed an unchanged pneumothorax that was now complicated by reexpansion pulmonary edema after thoracentesis (Figure 3, star). The reexpansion pulmonary edema resolved by the following day, and the pneumothorax resolved after placement of a pig-tail catheter into the pleural space (Figure 4).

Iatrogenic pneumothorax after thoracentesis occurs in 6% of cases.1 Iatrogenic reexpansion pulmonary edema after thoracentesis occurs in fewer than 1% of cases.2,3 Simultaneous pneumothorax and reexpansion pulmonary edema arising from the same procedure appears to be extremely rare.

- Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman D, Balk EM, Smetana GW. Pneumothorax following thoracentesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170:332–339.

- Ragozzino MW, Greene R. Bilateral reexpansion pulmonary edema following unilateral pleurocentesis. Chest 1991; 99:506–508.

- Dias OM, Teixeira LR, Vargas FS. Reexpansion pulmonary edema after therapeutic thoracentesis. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2010; 65:1387–1389.

- Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman D, Balk EM, Smetana GW. Pneumothorax following thoracentesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170:332–339.

- Ragozzino MW, Greene R. Bilateral reexpansion pulmonary edema following unilateral pleurocentesis. Chest 1991; 99:506–508.

- Dias OM, Teixeira LR, Vargas FS. Reexpansion pulmonary edema after therapeutic thoracentesis. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2010; 65:1387–1389.

USPSTF: Women smokers might benefit from AAA screening

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force says that women between ages 65 and 75 years who have smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lives could benefit from one-time ultrasonography screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA).

The AAA guidelines replace those published by USPSTS in 2005, which had recommended against screening in women regardless of smoking history.

The new guidelines, published online June 23 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi:10.7326/M14-1204), do not recommend screening in women who have never smoked, citing the very low prevalence of AAA in this group.

Nevertheless, the task force’s systematic review, led by current chair Dr. Michael L. LeFevre of the University of Missouri in Columbia, revealed that screening in women aged 65-75 years who have smoked or currently smoke – a group for which AAA prevalence is between 0.8% and 2% – could potentially be beneficial, though current evidence remains insufficient to recommend it.

"Prevalence of AAA in women who currently smoke approaches that of men who have never smoked," Dr. LeFevre and his colleagues wrote in the guidelines. "As such, a small net benefit might exist for this population and appropriate, high-quality research designs should be used to address this question."

The task force continues to recommend that men between the ages of 65 and 75 years who have ever smoked be offered one-time screening with ultrasonography for AAA. Men in this age group who have never smoked may be offered screening if they have certain risk factors, such as advanced age or a family history of AAA.

AAA – a dilation in the wall of the abdominal section of the aorta of 3 cm or larger – is seen in 4% and 7% of men and about 1% of women over the age of 50, USPSTF said. Most AAAs remain asymptomatic until they rupture, in which case the mortality risk has been shown to be higher than 75%. Women who develop AAA tend to do so at a later age than do men, the task force noted, with most ruptures occurring past age 80 years.

The task force is a voluntary advisory body independent of the U.S. government but supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. One of the study’s coauthors, Dr. Douglas Owens of the Stanford (Calif.) University, disclosed travel support from the agency during the course of the review. The other task force members declared no conflicts of interest.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force says that women between ages 65 and 75 years who have smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lives could benefit from one-time ultrasonography screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA).

The AAA guidelines replace those published by USPSTS in 2005, which had recommended against screening in women regardless of smoking history.

The new guidelines, published online June 23 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi:10.7326/M14-1204), do not recommend screening in women who have never smoked, citing the very low prevalence of AAA in this group.

Nevertheless, the task force’s systematic review, led by current chair Dr. Michael L. LeFevre of the University of Missouri in Columbia, revealed that screening in women aged 65-75 years who have smoked or currently smoke – a group for which AAA prevalence is between 0.8% and 2% – could potentially be beneficial, though current evidence remains insufficient to recommend it.

"Prevalence of AAA in women who currently smoke approaches that of men who have never smoked," Dr. LeFevre and his colleagues wrote in the guidelines. "As such, a small net benefit might exist for this population and appropriate, high-quality research designs should be used to address this question."

The task force continues to recommend that men between the ages of 65 and 75 years who have ever smoked be offered one-time screening with ultrasonography for AAA. Men in this age group who have never smoked may be offered screening if they have certain risk factors, such as advanced age or a family history of AAA.

AAA – a dilation in the wall of the abdominal section of the aorta of 3 cm or larger – is seen in 4% and 7% of men and about 1% of women over the age of 50, USPSTF said. Most AAAs remain asymptomatic until they rupture, in which case the mortality risk has been shown to be higher than 75%. Women who develop AAA tend to do so at a later age than do men, the task force noted, with most ruptures occurring past age 80 years.

The task force is a voluntary advisory body independent of the U.S. government but supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. One of the study’s coauthors, Dr. Douglas Owens of the Stanford (Calif.) University, disclosed travel support from the agency during the course of the review. The other task force members declared no conflicts of interest.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force says that women between ages 65 and 75 years who have smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lives could benefit from one-time ultrasonography screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA).

The AAA guidelines replace those published by USPSTS in 2005, which had recommended against screening in women regardless of smoking history.

The new guidelines, published online June 23 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi:10.7326/M14-1204), do not recommend screening in women who have never smoked, citing the very low prevalence of AAA in this group.

Nevertheless, the task force’s systematic review, led by current chair Dr. Michael L. LeFevre of the University of Missouri in Columbia, revealed that screening in women aged 65-75 years who have smoked or currently smoke – a group for which AAA prevalence is between 0.8% and 2% – could potentially be beneficial, though current evidence remains insufficient to recommend it.

"Prevalence of AAA in women who currently smoke approaches that of men who have never smoked," Dr. LeFevre and his colleagues wrote in the guidelines. "As such, a small net benefit might exist for this population and appropriate, high-quality research designs should be used to address this question."

The task force continues to recommend that men between the ages of 65 and 75 years who have ever smoked be offered one-time screening with ultrasonography for AAA. Men in this age group who have never smoked may be offered screening if they have certain risk factors, such as advanced age or a family history of AAA.

AAA – a dilation in the wall of the abdominal section of the aorta of 3 cm or larger – is seen in 4% and 7% of men and about 1% of women over the age of 50, USPSTF said. Most AAAs remain asymptomatic until they rupture, in which case the mortality risk has been shown to be higher than 75%. Women who develop AAA tend to do so at a later age than do men, the task force noted, with most ruptures occurring past age 80 years.

The task force is a voluntary advisory body independent of the U.S. government but supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. One of the study’s coauthors, Dr. Douglas Owens of the Stanford (Calif.) University, disclosed travel support from the agency during the course of the review. The other task force members declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Women aged 65-75 years who have smoked more than 100 cigarettes ever could benefit from one-time ultrasonography screening for AAA.

Major finding: Screening in women aged 65-75 years who have smoked or currently smoke – a group for which AAA prevalence is between 0.8% and 2% – could potentially be beneficial.

Data source: The USPSTF commissioned a systematic review that assessed the evidence on the benefits and harms of screening for AAA and strategies for managing small (3.0-5.4 cm) screen-detected AAAs.

Disclosures: Dr. Douglas Owens of the Stanford (Calif.) University, disclosed travel support from the agency during the course of the review.

ED doc survey: 22% of advanced imaging is ‘medically unnecessary’

DALLAS – On average, 22% of the CTs and MRIs ordered by emergency physicians are "medically unnecessary," based on responses by 435 emergency physicians participating in a national survey.

"The overwhelming majority of physicians in our sample recognized the issue of overimaging in the ED, and it’s not just something they felt was going on among others in their group. It’s something they personally acknowledged participating in," Dr. Hemal K. Kanzaria said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

The two most common reasons for ordering "medically unnecessary" advanced diagnostic imaging studies were fear of missing a diagnosis despite low pretest probability, cited by 69% of respondents, and fear of litigation, cited by 64%, noted Dr. Kanzaria, a Robert Woods Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholar and emergency medicine fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Patient and family expectations were identified as a driving force in ordering medically unnecessary imaging, 40% of respondents said. A mere 1% of respondents cited administrative pressure to increase group reimbursement as a main contributor, he added.

Advanced diagnostic imaging in EDs has increased appreciably in recent years, with little evidence of a resultant improvement in patient outcomes. The trend has drawn scrutiny from health policy experts in light of estimates that the U.S. annually spends $210 billion on unnecessary medical tests, procedures, and services. Yet there are little data on emergency physicians’ perceptions regarding overordering of CTs and MRIs, the causes, and the potential solutions.

"Basically, we need to know what physicians are thinking (about the issue), and that’s why we did this study," Dr. Kanzaria explained.

Two focus groups of multispecialty physicians and expert opinion from physicians who have researched overordering of diagnostic imaging were used to create the questions, which were then revised in response to a pilot study conducted among 16 emergency physicians.

The resulting 19-item survey took about 10 minutes to complete. The survey defined a "medically unnecessary" imaging study as "one you wouldn’t order if you had no external pressure and were only concerned about providing optimal medical care."

The nonrandom sample for the survey included 478 academic and community practice emergency physicians in 29 states; the completion rate was a whopping 91% (435 respondents). Respondents’ average age was 42 years with a mean 14 years in clinical practice; 68% were board-certified in emergency medicine. The pattern of survey responses did not differ based upon physician age, years in practice, or board certification status.

More than 85% of the emergency physicians said they believe too many diagnostic tests are ordered in their own ED. More specifically, a similarly lofty percentage believe medically unnecessary CTs and MRIs are ordered in their ED under common clinical scenarios described in the survey, such as head CTs for nontraumatic headaches and pan scans for trauma patients. Fully 97% of EPs acknowledged ordering medically unnecessary CTs and MRIs.

More than 50% of respondents identified as "extremely or very helpful" proposed solutions to "medically unnecessary" advanced imaging in the ED.

Topping the options was tort reform, which 79% of emergency physicians thought would make a major difference. However, Dr. Kanzaria called malpractice reform necessary but not sufficient to change practice. "Recent studies on tort reform efforts have not actually shown subsequent significant effects on cost reduction or a change in test-ordering behavior."

A more promising option may be shared decision making with patients regarding diagnostic testing for low-probability outcomes, he said. "The literature on shared decision making is still in its infancy, but what’s out there [indicates this option] is really promising as an avenue to improve communication and potentially to reduce overuse. So, I think we should consider ways to incorporate shared decision making into emergency care," Dr. Kanzaria said.

Another popular suggestion was to provide feedback to emergency physicians regarding their own test ordering behavior compared to that of their peers, something Dr. Kanzaria called "incredibly simple to do."

Education aimed at steering patients, families, and referring physicians away from the prevailing "no miss" attitude in favor of greater understanding of the probabilistic limits of diagnostic testing was also widely endorsed by the survey respondents.

Dr. Kanzaria’s research is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program. He reported having no financial conflicts.

DALLAS – On average, 22% of the CTs and MRIs ordered by emergency physicians are "medically unnecessary," based on responses by 435 emergency physicians participating in a national survey.

"The overwhelming majority of physicians in our sample recognized the issue of overimaging in the ED, and it’s not just something they felt was going on among others in their group. It’s something they personally acknowledged participating in," Dr. Hemal K. Kanzaria said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

The two most common reasons for ordering "medically unnecessary" advanced diagnostic imaging studies were fear of missing a diagnosis despite low pretest probability, cited by 69% of respondents, and fear of litigation, cited by 64%, noted Dr. Kanzaria, a Robert Woods Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholar and emergency medicine fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Patient and family expectations were identified as a driving force in ordering medically unnecessary imaging, 40% of respondents said. A mere 1% of respondents cited administrative pressure to increase group reimbursement as a main contributor, he added.

Advanced diagnostic imaging in EDs has increased appreciably in recent years, with little evidence of a resultant improvement in patient outcomes. The trend has drawn scrutiny from health policy experts in light of estimates that the U.S. annually spends $210 billion on unnecessary medical tests, procedures, and services. Yet there are little data on emergency physicians’ perceptions regarding overordering of CTs and MRIs, the causes, and the potential solutions.

"Basically, we need to know what physicians are thinking (about the issue), and that’s why we did this study," Dr. Kanzaria explained.

Two focus groups of multispecialty physicians and expert opinion from physicians who have researched overordering of diagnostic imaging were used to create the questions, which were then revised in response to a pilot study conducted among 16 emergency physicians.

The resulting 19-item survey took about 10 minutes to complete. The survey defined a "medically unnecessary" imaging study as "one you wouldn’t order if you had no external pressure and were only concerned about providing optimal medical care."

The nonrandom sample for the survey included 478 academic and community practice emergency physicians in 29 states; the completion rate was a whopping 91% (435 respondents). Respondents’ average age was 42 years with a mean 14 years in clinical practice; 68% were board-certified in emergency medicine. The pattern of survey responses did not differ based upon physician age, years in practice, or board certification status.

More than 85% of the emergency physicians said they believe too many diagnostic tests are ordered in their own ED. More specifically, a similarly lofty percentage believe medically unnecessary CTs and MRIs are ordered in their ED under common clinical scenarios described in the survey, such as head CTs for nontraumatic headaches and pan scans for trauma patients. Fully 97% of EPs acknowledged ordering medically unnecessary CTs and MRIs.

More than 50% of respondents identified as "extremely or very helpful" proposed solutions to "medically unnecessary" advanced imaging in the ED.

Topping the options was tort reform, which 79% of emergency physicians thought would make a major difference. However, Dr. Kanzaria called malpractice reform necessary but not sufficient to change practice. "Recent studies on tort reform efforts have not actually shown subsequent significant effects on cost reduction or a change in test-ordering behavior."

A more promising option may be shared decision making with patients regarding diagnostic testing for low-probability outcomes, he said. "The literature on shared decision making is still in its infancy, but what’s out there [indicates this option] is really promising as an avenue to improve communication and potentially to reduce overuse. So, I think we should consider ways to incorporate shared decision making into emergency care," Dr. Kanzaria said.

Another popular suggestion was to provide feedback to emergency physicians regarding their own test ordering behavior compared to that of their peers, something Dr. Kanzaria called "incredibly simple to do."

Education aimed at steering patients, families, and referring physicians away from the prevailing "no miss" attitude in favor of greater understanding of the probabilistic limits of diagnostic testing was also widely endorsed by the survey respondents.

Dr. Kanzaria’s research is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program. He reported having no financial conflicts.

DALLAS – On average, 22% of the CTs and MRIs ordered by emergency physicians are "medically unnecessary," based on responses by 435 emergency physicians participating in a national survey.

"The overwhelming majority of physicians in our sample recognized the issue of overimaging in the ED, and it’s not just something they felt was going on among others in their group. It’s something they personally acknowledged participating in," Dr. Hemal K. Kanzaria said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

The two most common reasons for ordering "medically unnecessary" advanced diagnostic imaging studies were fear of missing a diagnosis despite low pretest probability, cited by 69% of respondents, and fear of litigation, cited by 64%, noted Dr. Kanzaria, a Robert Woods Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholar and emergency medicine fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Patient and family expectations were identified as a driving force in ordering medically unnecessary imaging, 40% of respondents said. A mere 1% of respondents cited administrative pressure to increase group reimbursement as a main contributor, he added.

Advanced diagnostic imaging in EDs has increased appreciably in recent years, with little evidence of a resultant improvement in patient outcomes. The trend has drawn scrutiny from health policy experts in light of estimates that the U.S. annually spends $210 billion on unnecessary medical tests, procedures, and services. Yet there are little data on emergency physicians’ perceptions regarding overordering of CTs and MRIs, the causes, and the potential solutions.

"Basically, we need to know what physicians are thinking (about the issue), and that’s why we did this study," Dr. Kanzaria explained.

Two focus groups of multispecialty physicians and expert opinion from physicians who have researched overordering of diagnostic imaging were used to create the questions, which were then revised in response to a pilot study conducted among 16 emergency physicians.

The resulting 19-item survey took about 10 minutes to complete. The survey defined a "medically unnecessary" imaging study as "one you wouldn’t order if you had no external pressure and were only concerned about providing optimal medical care."

The nonrandom sample for the survey included 478 academic and community practice emergency physicians in 29 states; the completion rate was a whopping 91% (435 respondents). Respondents’ average age was 42 years with a mean 14 years in clinical practice; 68% were board-certified in emergency medicine. The pattern of survey responses did not differ based upon physician age, years in practice, or board certification status.

More than 85% of the emergency physicians said they believe too many diagnostic tests are ordered in their own ED. More specifically, a similarly lofty percentage believe medically unnecessary CTs and MRIs are ordered in their ED under common clinical scenarios described in the survey, such as head CTs for nontraumatic headaches and pan scans for trauma patients. Fully 97% of EPs acknowledged ordering medically unnecessary CTs and MRIs.

More than 50% of respondents identified as "extremely or very helpful" proposed solutions to "medically unnecessary" advanced imaging in the ED.

Topping the options was tort reform, which 79% of emergency physicians thought would make a major difference. However, Dr. Kanzaria called malpractice reform necessary but not sufficient to change practice. "Recent studies on tort reform efforts have not actually shown subsequent significant effects on cost reduction or a change in test-ordering behavior."

A more promising option may be shared decision making with patients regarding diagnostic testing for low-probability outcomes, he said. "The literature on shared decision making is still in its infancy, but what’s out there [indicates this option] is really promising as an avenue to improve communication and potentially to reduce overuse. So, I think we should consider ways to incorporate shared decision making into emergency care," Dr. Kanzaria said.

Another popular suggestion was to provide feedback to emergency physicians regarding their own test ordering behavior compared to that of their peers, something Dr. Kanzaria called "incredibly simple to do."

Education aimed at steering patients, families, and referring physicians away from the prevailing "no miss" attitude in favor of greater understanding of the probabilistic limits of diagnostic testing was also widely endorsed by the survey respondents.

Dr. Kanzaria’s research is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program. He reported having no financial conflicts.

AT SAEM 2014

Psychiatric comorbidities add to migraineurs’ medical interventions

PHILADELPHIA – Patients who have migraines and comorbid psychiatric disorders visited the emergency department more, and received more brain imaging and narcotics, than patients who had only migraine.

The additional emergency visits and procedures – combined with significantly higher rates of hospital admissions and outpatient visits – run contrary to published recommendations, Dr. Mia Minen reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The imaging findings of her cross-sectional analysis are particularly troubling in light of current guidelines aimed at helping to minimize radiation exposure by avoiding head and brain imaging in patients with primary headache disorders, said Dr. Minen, a fellow at the Graham Headache Center, Boston.

"One of the AAN’s recommendations for the Choosing Wisely campaign was not to perform brain imaging for patients presenting to the ED with recurrence of their baseline primary headache disorder," she said. She added that the American College of Emergency Physicians has not found level A evidence supporting imaging in patients who present to the emergency department with headache, unless the headache is sudden and severe, or unless it’s accompanied by an abnormal neurological exam.

Her analysis looked at emergency treatment trends in a database of almost 3,000 headache patients seen over a 10-year period in a single hospital’s emergency department. The patients were a mean of 40 years old; most (80%) were women. About 2,000 had at least one psychiatric comorbidity; the most common psychiatric comorbidities were anxiety and depression.

Over the 10-year study period, migraine patients overall made an average of 11 ED visits, with 10 admissions and 26 outpatient visits. Those patients without a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis made significantly fewer visits in every category: 6 ED visits, 3 inpatient visits, and 11 outpatient visits.

Migraine patients with comorbidities presented a very different picture, Dr. Minen said. These patients had an average of 18 ED visits, 19 inpatient visits, and 45 outpatient visits over the study period.

Compared with migraineurs without psychiatric disorders, those with them were significantly more likely to undergo a CT of the head (relative risk, 1.4) and an MRI of the brain (RR, 1.5). They received narcotic treatment in the ED significantly more often as well.

"We need more studies to understand why this is the case," Dr. Minen said.

She added that the pharmacotherapy findings also were in contrast to recommendations in the AAN Choosing Wisely campaign.

"In 2013, one of the final recommendations was not to use opiates or butalbital for the treatment of migraine, except in rare circumstances."

Dr. Minen had no financial disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – Patients who have migraines and comorbid psychiatric disorders visited the emergency department more, and received more brain imaging and narcotics, than patients who had only migraine.

The additional emergency visits and procedures – combined with significantly higher rates of hospital admissions and outpatient visits – run contrary to published recommendations, Dr. Mia Minen reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The imaging findings of her cross-sectional analysis are particularly troubling in light of current guidelines aimed at helping to minimize radiation exposure by avoiding head and brain imaging in patients with primary headache disorders, said Dr. Minen, a fellow at the Graham Headache Center, Boston.

"One of the AAN’s recommendations for the Choosing Wisely campaign was not to perform brain imaging for patients presenting to the ED with recurrence of their baseline primary headache disorder," she said. She added that the American College of Emergency Physicians has not found level A evidence supporting imaging in patients who present to the emergency department with headache, unless the headache is sudden and severe, or unless it’s accompanied by an abnormal neurological exam.

Her analysis looked at emergency treatment trends in a database of almost 3,000 headache patients seen over a 10-year period in a single hospital’s emergency department. The patients were a mean of 40 years old; most (80%) were women. About 2,000 had at least one psychiatric comorbidity; the most common psychiatric comorbidities were anxiety and depression.

Over the 10-year study period, migraine patients overall made an average of 11 ED visits, with 10 admissions and 26 outpatient visits. Those patients without a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis made significantly fewer visits in every category: 6 ED visits, 3 inpatient visits, and 11 outpatient visits.

Migraine patients with comorbidities presented a very different picture, Dr. Minen said. These patients had an average of 18 ED visits, 19 inpatient visits, and 45 outpatient visits over the study period.

Compared with migraineurs without psychiatric disorders, those with them were significantly more likely to undergo a CT of the head (relative risk, 1.4) and an MRI of the brain (RR, 1.5). They received narcotic treatment in the ED significantly more often as well.

"We need more studies to understand why this is the case," Dr. Minen said.

She added that the pharmacotherapy findings also were in contrast to recommendations in the AAN Choosing Wisely campaign.

"In 2013, one of the final recommendations was not to use opiates or butalbital for the treatment of migraine, except in rare circumstances."

Dr. Minen had no financial disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – Patients who have migraines and comorbid psychiatric disorders visited the emergency department more, and received more brain imaging and narcotics, than patients who had only migraine.

The additional emergency visits and procedures – combined with significantly higher rates of hospital admissions and outpatient visits – run contrary to published recommendations, Dr. Mia Minen reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The imaging findings of her cross-sectional analysis are particularly troubling in light of current guidelines aimed at helping to minimize radiation exposure by avoiding head and brain imaging in patients with primary headache disorders, said Dr. Minen, a fellow at the Graham Headache Center, Boston.

"One of the AAN’s recommendations for the Choosing Wisely campaign was not to perform brain imaging for patients presenting to the ED with recurrence of their baseline primary headache disorder," she said. She added that the American College of Emergency Physicians has not found level A evidence supporting imaging in patients who present to the emergency department with headache, unless the headache is sudden and severe, or unless it’s accompanied by an abnormal neurological exam.

Her analysis looked at emergency treatment trends in a database of almost 3,000 headache patients seen over a 10-year period in a single hospital’s emergency department. The patients were a mean of 40 years old; most (80%) were women. About 2,000 had at least one psychiatric comorbidity; the most common psychiatric comorbidities were anxiety and depression.

Over the 10-year study period, migraine patients overall made an average of 11 ED visits, with 10 admissions and 26 outpatient visits. Those patients without a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis made significantly fewer visits in every category: 6 ED visits, 3 inpatient visits, and 11 outpatient visits.

Migraine patients with comorbidities presented a very different picture, Dr. Minen said. These patients had an average of 18 ED visits, 19 inpatient visits, and 45 outpatient visits over the study period.

Compared with migraineurs without psychiatric disorders, those with them were significantly more likely to undergo a CT of the head (relative risk, 1.4) and an MRI of the brain (RR, 1.5). They received narcotic treatment in the ED significantly more often as well.

"We need more studies to understand why this is the case," Dr. Minen said.

She added that the pharmacotherapy findings also were in contrast to recommendations in the AAN Choosing Wisely campaign.

"In 2013, one of the final recommendations was not to use opiates or butalbital for the treatment of migraine, except in rare circumstances."

Dr. Minen had no financial disclosures.

AT THE AAN 2014 ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: More studies are needed to determine why migraineurs with psychiatric disorders are more likely than those without comorbidities to undergo brain imaging and to receive narcotics.

Major finding: Migraine patients with psychiatric comorbidities were 40% more likely to have head imaging and 50% more likely to receive narcotics than those without such conditions.

Data source: The cross-sectional analysis comprised almost 3,000 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Minen had no financial disclosures.

Radiation exposure in children with heart disease highest for transplants

Children with heart disease are cumulatively exposed to relatively low levels of ionizing radiation from imaging procedures – less than the average annual background exposure in the United States – although those who have undergone more complex procedures such as heart transplants or cardiac catheterization experience significantly greater exposure, a retrospective cohort study has found.

Dr. Jason N. Johnson, a pediatric cardiologist at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues showed that the estimated lifetime attributable risk of cancer above baseline ranged from 6 cases per 100,000 exposed for children with atrial septal defect, to 1,677 per 100,000 exposed for cardiac transplant, with a median of 65 cases per 100,000 across surgical cohorts.

While conventional radiographic examination accounted for 92% of the total examinations, it accounted for only 8% of the cumulative effective dose, compared with cardiac catheterization, which represented 1.5% of all examinations but accounted for 60% of the total radiation exposure, according to a study published online June 9 in Circulation.

The study of 337 children aged 6 years or younger exposed to more than 13,000 radiation examinations found the lifetime attributable risk of cancer was nearly double in females versus males, mostly because of increased breast and thyroid cancer risk (Circulation 2014 June 9 [doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005425]).

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Mend a Heart Foundation. One author reported receiving support from the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the U.S. Department of Energy, and Duke University.

Children with heart disease are cumulatively exposed to relatively low levels of ionizing radiation from imaging procedures – less than the average annual background exposure in the United States – although those who have undergone more complex procedures such as heart transplants or cardiac catheterization experience significantly greater exposure, a retrospective cohort study has found.

Dr. Jason N. Johnson, a pediatric cardiologist at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues showed that the estimated lifetime attributable risk of cancer above baseline ranged from 6 cases per 100,000 exposed for children with atrial septal defect, to 1,677 per 100,000 exposed for cardiac transplant, with a median of 65 cases per 100,000 across surgical cohorts.

While conventional radiographic examination accounted for 92% of the total examinations, it accounted for only 8% of the cumulative effective dose, compared with cardiac catheterization, which represented 1.5% of all examinations but accounted for 60% of the total radiation exposure, according to a study published online June 9 in Circulation.

The study of 337 children aged 6 years or younger exposed to more than 13,000 radiation examinations found the lifetime attributable risk of cancer was nearly double in females versus males, mostly because of increased breast and thyroid cancer risk (Circulation 2014 June 9 [doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005425]).

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Mend a Heart Foundation. One author reported receiving support from the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the U.S. Department of Energy, and Duke University.

Children with heart disease are cumulatively exposed to relatively low levels of ionizing radiation from imaging procedures – less than the average annual background exposure in the United States – although those who have undergone more complex procedures such as heart transplants or cardiac catheterization experience significantly greater exposure, a retrospective cohort study has found.

Dr. Jason N. Johnson, a pediatric cardiologist at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues showed that the estimated lifetime attributable risk of cancer above baseline ranged from 6 cases per 100,000 exposed for children with atrial septal defect, to 1,677 per 100,000 exposed for cardiac transplant, with a median of 65 cases per 100,000 across surgical cohorts.

While conventional radiographic examination accounted for 92% of the total examinations, it accounted for only 8% of the cumulative effective dose, compared with cardiac catheterization, which represented 1.5% of all examinations but accounted for 60% of the total radiation exposure, according to a study published online June 9 in Circulation.

The study of 337 children aged 6 years or younger exposed to more than 13,000 radiation examinations found the lifetime attributable risk of cancer was nearly double in females versus males, mostly because of increased breast and thyroid cancer risk (Circulation 2014 June 9 [doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005425]).

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Mend a Heart Foundation. One author reported receiving support from the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the U.S. Department of Energy, and Duke University.

FROM CIRCULATION

Key clinical point: Imaging radiation associated with heart transplants raises children’s lifetime cancer risk by 6.5%.

Major finding: Children with heart disease are cumulatively exposed to relatively low levels of ionizing radiation from imaging procedures – less than the average annual background exposure in the United States – although those who have undergone more complex procedures such as heart transplants or cardiac catheterization experience significantly greater exposure, with a lifetime attributable risk of cancer 6.5% above baseline across the surgical cohort.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 337 children aged 6 years or younger exposed to more than 13,000 radiation examinations from a single center.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Mend a Heart Foundation. One author reported receiving support from the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the U.S. Department of Energy, and Duke University.

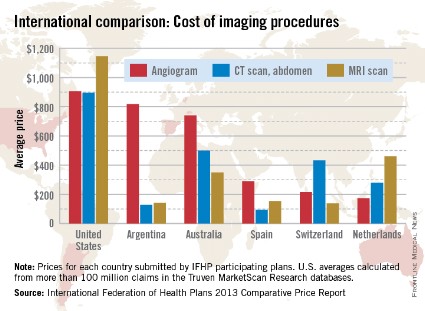

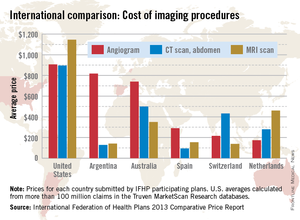

Imaging procedure costs higher in the United States

When it comes to diagnostic imaging, the average costs of angiograms, abdominal CTs, and MRIs are higher in the United States than in other industrialized countries, according to the International Federation of Health Plans’ 2013 Comparative Price Report.

The average cost of an angiogram in the United States last year was $907, about 11% higher than Argentina’s $818, which was the second-highest of the six countries included in all three IFHP comparisons. The lowest cost among the six countries was in the Netherlands, at $174.

For an abdominal CT scan, the average cost in the United States was $896 in 2013, compared with $500 in Australia. Spain had the lowest cost, with an average of $94, the IFHP reported. In the United States, the average price for an MRI in 2013 was $1,145, with the Netherlands second at $461 and Switzerland lowest at $138.

New Zealand, which was not included in the angiogram analysis and therefore left out of the graph below, was actually the second most-expensive country in which to get a CT scan ($731) and an MRI ($1,005).

The IFHP is composed of more than 100 member companies in 25 countries. For the survey, the price for each country was submitted by participating member plans. Some prices are drawn from the public sector, and some are from the private sector. U.S. averages are calculated from more than 100 million claims in the Truven MarketScan Research databases.

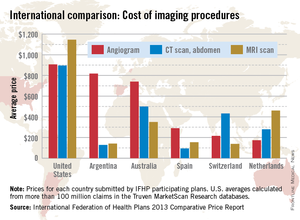

When it comes to diagnostic imaging, the average costs of angiograms, abdominal CTs, and MRIs are higher in the United States than in other industrialized countries, according to the International Federation of Health Plans’ 2013 Comparative Price Report.

The average cost of an angiogram in the United States last year was $907, about 11% higher than Argentina’s $818, which was the second-highest of the six countries included in all three IFHP comparisons. The lowest cost among the six countries was in the Netherlands, at $174.

For an abdominal CT scan, the average cost in the United States was $896 in 2013, compared with $500 in Australia. Spain had the lowest cost, with an average of $94, the IFHP reported. In the United States, the average price for an MRI in 2013 was $1,145, with the Netherlands second at $461 and Switzerland lowest at $138.

New Zealand, which was not included in the angiogram analysis and therefore left out of the graph below, was actually the second most-expensive country in which to get a CT scan ($731) and an MRI ($1,005).

The IFHP is composed of more than 100 member companies in 25 countries. For the survey, the price for each country was submitted by participating member plans. Some prices are drawn from the public sector, and some are from the private sector. U.S. averages are calculated from more than 100 million claims in the Truven MarketScan Research databases.

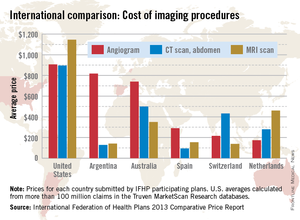

When it comes to diagnostic imaging, the average costs of angiograms, abdominal CTs, and MRIs are higher in the United States than in other industrialized countries, according to the International Federation of Health Plans’ 2013 Comparative Price Report.

The average cost of an angiogram in the United States last year was $907, about 11% higher than Argentina’s $818, which was the second-highest of the six countries included in all three IFHP comparisons. The lowest cost among the six countries was in the Netherlands, at $174.

For an abdominal CT scan, the average cost in the United States was $896 in 2013, compared with $500 in Australia. Spain had the lowest cost, with an average of $94, the IFHP reported. In the United States, the average price for an MRI in 2013 was $1,145, with the Netherlands second at $461 and Switzerland lowest at $138.

New Zealand, which was not included in the angiogram analysis and therefore left out of the graph below, was actually the second most-expensive country in which to get a CT scan ($731) and an MRI ($1,005).

The IFHP is composed of more than 100 member companies in 25 countries. For the survey, the price for each country was submitted by participating member plans. Some prices are drawn from the public sector, and some are from the private sector. U.S. averages are calculated from more than 100 million claims in the Truven MarketScan Research databases.

Case Report: An Unusual Case of Arrhythmia

Case

A 3-year-old girl presented to the ED with a 1-week history of cough and new-onset abdominal pain. She was accompanied by her grandfather, who stated that the child had been dropped-off at his house around 5:00 pm the previous day. He noted that after putting his granddaughter to bed, she awoke around 4:30 am complaining of a stomachache. After rocking her, he said she went back to sleep but did not wake up again until 1:00 pm that afternoon. Over the first few hours of awakening, she became less active and had three episodes of posttussive emesis. The grandfather denied the child had any recent nasal congestion, fever, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. When questioned about possible toxic ingestion, he said there were no medications in the house and that he did not witness any substance ingestion or trauma.

At presentation, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure (BP) 86/49 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 178 beats/minute and regular; respiratory rate (RR), 26 breaths/minute; temporal artery temperature, 104.7°F. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. On physical examination, she was normocephalic; there was no scleral icterus; and the throat and bilateral tympanic membranes were normal. Her extremities were warm and well perfused, with normal capillary refill. Patient’s lungs were clear, and heart sounds were normal with no detection of a murmur. The abdomen was soft and nontender; there was no evidence of organomegaly.

Laboratory evaluation included assessment of sodium, chloride, carbon dioxide, calcium, magnesium, amylase, lipase, and creatine levels; liver function test; complete blood count; and red-cell indices. All of the laboratory values were within normal limits, and urinalysis was negative for infection. Blood and urine cultures were also taken. A chest X-ray showed no acute intrathoracic process (Figure 1).

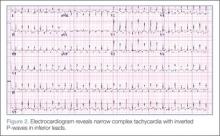

During treatment, the patient became increasingly fussy with new-onset abdominal distension. Repeat physical examination revealed hepatomegaly. A bedside echocardiogram showed hyperdynamic heart with fractional shortening* (FS) of 20% and ejection fraction (EF) of 43%, but no structural abnormalities. An electrocardiogram (ECG) was then ordered, which revealed narrow complex tachycardia with inverted P-waves in inferior leads.

Discussion

Normal cardiac conduction involves an originating impulse from a sinus node followed by atrial muscle activation reaching the atrioventricular (AV) node. There is a necessary delay at the AV node, which is required for ventricular filling and activation of ventricles through the His-Purkinje fiber system and the bundle branches. An abnormality or interruption of this pathway results in an arrhythmia such as supraventricular tachycardia (SVT).

Supraventricular Tachycardia

Supraventricular tachycardia is the most common symptomatic abnormality in the pediatric population.1 Among the various forms of SVT, AV reentrant tachycardia (AVRT) and AV node reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT) account for most case presentations.2 Supraventricular tachycardia may be classified by duration of RP interval compared to PR interval on ECG. Short RP interval SVT includes AVNRT and AVRT through a rapidly conducting accessory path. Long RP interval SVT includes atypical AVNRT, atrial tachycardia, and PJRT.

Persistent Junctional Reentrant Tachycardia

Persistent junctional reentrant tachycardia is a rare form of long RP tachycardia, accounting for approximately 1% of SVT in a study review of 21 patients.3 As with the patient in this case, PJRT usually presents in early childhood.3 In a recent review of 194 patients with PJRT, 57% were infants.4 The condition involves an accessory pathway most commonly located in the posterior-superior septal region; conduction involves a retrograde impulse through the decremental accessory pathway.5 On ECG, findings include a negative P wave in inferior leads, a long RP interval, and a 1:1 AV conduction.6

A long-term multicenter follow-up study of 32 patients showed that rates of tachycardia vary among patients, from 100 to 250 beats/minute.7 Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy (TIC), which is secondary to the incessant nature of tachycardia, may be present in up to 30% to 50% of patients.3,8 In a recent multicenter study, PJRT was responsible for 23% of cases of TIC.9 Although the exact mechanism of this property is unknown, decremental conduction and unidirectional block of the accessory pathway appear to be contributing factors.6

Treatment

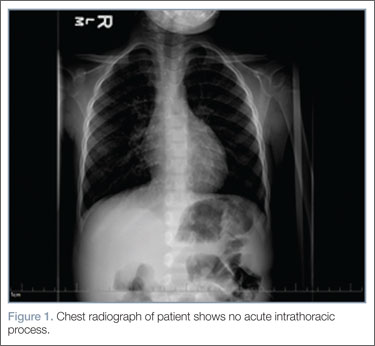

Adenosine is the initial drug of choice for narrow complex tachycardia with stable hemodynamic status and an available intravascular access.10 In a study evaluating the effectiveness of adenosine for managing SVT in the pediatric ED setting, it was more than 70% effective in cardioverting patients presumed to have SVT.11 However, in PJRT, owing to the incessant pattern, adenosine may either terminate the tachycardia (causing asystole) or, as seen in this patient, convert tachycardia to sinus rhythm for only a few seconds.12 Reinitiation of tachycardia in sinus beat without the need for a premature complex contributes to its incessant nature.13

In a multicenter study looking at clinical profile and outcome for PJRT, Vaksmann et al8 found a greater than 80% success rate in controlling the dysrhythmia with amiodarone and verapamil. For long-term management of tachyarrhythmia, medical therapy has been recommended in early childhood compared to older children in whom catheter ablation is an effective approach.7 Spontaneous resolution of PJRT has been documented but is rare.14

Conclusion

Pediatric cardiac emergencies require very specific treatment. As such, it is important that the emergency physician distinguish the different the types of tachyarrhythmias—especially in cases that do not respond to treatment with adenosine. In the pediatric patient, PJRT is a potentially life-threatening arrhythmia that requires a high index of suspicion. Clues to diagnosis include negative P waves in inferior leads, long RP interval, and 1:1 atrioventricular conduction.

Dr Fichadia is a fellow, pediatric emergency medicine, Wayne State University, Children’s Hospital of Michigan. Dr Perez is a clinical instructor, pediatric emergency medicine, Wayne State University, Children’s Hospital of Michigan.

- Doniger SJ, Sharieff GQ. Pediatric dysrhythmias. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006; 53(1):85-105, vi.

- Ko JK, Deal BJ, Strasburger JF, Benson DW Jr. Supraventricular tachycardia mechanisms and their age distribution in pediatric patients. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69(12):1028-1032.

- Dorostkar PC, Silka MJ, Morady F, Dick M 2nd. Clinical course of persistent junctional reciprocating tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(2):366-375.

- Kang KT, Potts JE, Radbill AE, et al. Permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia in children: A multi-center experience: Permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia [published online ahead of print April 24, 2014]. Heart Rhythm. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.04.033.

- Fox DJ, Tischenko A, Krahn AD, et al. Supraventricular tachycardia: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(12):1400-1411.