User login

Malpractice Counsel

Stroke in a Young Man

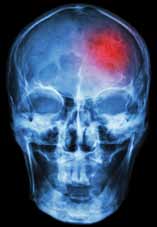

A 26-year-old man presented to the ED with the chief complaint of mild right-sided weakness, paresthesias, and slurred speech. He stated the onset was sudden—approximately 30 minutes prior to arrival to the ED. The patient denied any previous similar symptoms and was otherwise in good health; he denied taking any medications. He drank alcohol socially, but denied smoking or illicit drug use.

On physical examination, his vital signs and oxygen saturation were normal. Pulmonary, cardiovascular, and abdominal examinations were also normal. The patient thought his speech was somewhat slurred, but the triage nurse and treating emergency physician (EP) had difficulty detecting any altered speech. He was noted to have mild (4+/5) right upper and lower extremity weakness; no facial droop was detected. The patient did have a mild pronator drift of the right upper extremity. Gait testing revealed a mild limp of the right lower extremity.

The EP consulted the hospitalist, and the patient was admitted to a monitored bed. The following morning, a brain magnetic resonance image revealed an ischemic stroke in the distribution of the left middle cerebral artery. The patient’s hospital course was uncomplicated, but at the time of discharge, he continued to have mild right-sided weakness and required the use of a cane.

The patient sued the hospital and the EP for negligence in failing to treat his condition in a timely manner and for not consulting a neurologist. The plaintiff’s attorneys argued the patient should have been given tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which would have avoided the residual right-sided weakness. The defense denied negligence and argued the patient’s symptoms could have been due to several things for which tPA would have been an inappropriate treatment. A defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

Stroke in young patients is relatively rare. With “young” defined as aged 18 to 45 years, this population accounts for approximately 2% to 12% of cerebral infarcts.1 In one nationwide US study of stroke in young adults, Ellis2 found that 4.9% of individuals experiencing a stroke in 2007 were between ages 18 and 44 years. Among this group, 78% experienced an ischemic stroke; 11.2% experienced a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH); and 10.8% had an intracerebral hemorrhage.2

While the clinical presentation of stroke in young adults is similar to that of older patients, the etiologies and risk factors are very different. In older patients, atherosclerosis is the major cause of ischemic stroke. In studies of young adults with ischemic stroke, cardioembolism was found to be the leading cause. Under this category, a patent foramen ovale (PFO) was considered a common cause, followed by atrial fibrillation, bacterial endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, and atrial myxoma. There is, however, increasing controversy over the role of PFO as an etiology of stroke. Many investigators think its role has been overstated and is probably more of an incidental finding than a causal relationship.3 Patients with a suspected cardioembolic etiology will usually require an echocardiogram (with saline contrast or a “bubble study” for suspected PFO), cardiac monitoring, and a possible Holter monitor at the time of discharge (to detect paroxysmal arrhythmias).

Following cardioembolic etiologies, arterial dissection is the next most common category.4 In one study of patients aged 31 to 45 years old, arterial dissection was the most common cause of ischemic stroke.4 Clinical features suggesting dissection include a history of head or neck trauma (even minor trauma), headache or neck pain, and local neurological findings (eg, cranial nerve palsy or Horner syndrome).3 Unfortunately, only about 25% of patients volunteer a history of recent neck trauma. If a cervical or vertebral artery dissection is suspected, contrast enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is the most sensitive and specific test, followed by carotid ultrasound and CT angiography.3

Traditional risk factors for stroke include hypertension and diabetes mellitus (DM). This is not true for younger adults that experience an ischemic stroke. Cigarette smoking is a very important risk factor for cerebrovascular accident in young adults; in addition, the more one smokes, the greater the risk. Other risk factors in young adults include history of migraine headaches (especially migraine with aura), pregnancy and the postpartum period, and illicit drug use.3

The defense’s argument that there are many causes of stroke in young adults that would be inappropriate for treatment with tPA, such as a PFO, carotid dissection or bacterial endocarditis, is absolutely true. Young patients need to be aggressively worked up for the etiology of their stroke, and may require additional testing, such as an MRA, echocardiogram, or Holter monitoring to determine the underlying cause of their stroke.

Obstruction Following Gastric Bypass Surgery

A 47-year-old woman presented to the ED complaining of severe back and abdominal pain. Onset had been gradual and began approximately 4 hours prior to arrival. She described the pain as crampy and constant. The patient had vomited twice; she denied diarrhea and had a normal bowel movement the previous day. She denied any vaginal or urinary complaints. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension and status post gastric bypass surgery 6 months prior. She had lost 42 pounds to date. She denied smoking or alcohol use.

The patient’s vital signs on physical examination were: blood pressure, 154/92 mm Hg; pulse, 106 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute; and temperature, 99˚F. Oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The patient’s lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. The heart was mildly tachycardic, with a regular rhythm and without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The abdominal examination revealed diffuse tenderness and involuntary guarding. There was no distention or rebound. Bowel sounds were present but hypoactive. Examination of the back revealed bilateral paraspinal muscle tenderness without costovertebral angle tenderness.

The EP ordered a CBC, BMP, serum lipase, and a urinalysis. The patient was given an intravenous (IV) bolus of 250 cc normal saline in addition to IV morphine 4 mg and IV ondansetron 4 mg. Her white blood cell (WBC) count was slightly elevated at 12.2 g/dL, with a normal differential. The remainder of the laboratory studies were normal, except for a serum bicarbonate of 22 mmol/L.

The patient stated she felt somewhat improved, but continued to have abdominal and back pain. The EP admitted her to the hospital for observation and pain control. She died the following day from a bowel obstruction. The family sued the EP for negligence in failing to order appropriate testing and for not consulting with specialists to diagnose the bowel obstruction, which is a known complication of gastric bypass surgery. The jury returned a verdict of $2.4 million against the EP.

Discussion

The frequency of bariatric surgery in the United States continues to increase, primarily due to its success with regard to weight loss, but also because of its demonstrated improvement in hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 DM.1

Frequently, the term “gastric bypass surgery” is used interchangeably with bariatric surgery. However, the EP must realize these terms encompass multiple different operations. The four most common types of bariatric surgery in the United Stated are (1) adjustable gastric banding (AGB); (2) the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB); (3) biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS); and (4) vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG).2 (See the Table for a brief explanation of each type of procedure.)

Since each procedure has its own respective associated complications, it is important for the EP to know which the type of gastric bypass surgery the patient had. For example, leakage is much more frequent following RYGB than in gastric banding, while slippage and obstruction are the most common complications of gastric banding.3,4 It is also very helpful to know the specific type of procedure when discussing the case with the surgical consultant.

Based on a recent review of over 800,000 bariatric surgery patients, seven serious common complications following the surgery were identified.3 These included bleeding, leakage, obstruction, stomal ulceration, pulmonary embolism and respiratory complications, blood sugar disturbances (usually hypoglycemia and/or metabolic acidosis), and nutritional disturbances. While not all-inclusive, this list represents the most common serious complications of gastric bypass surgery.

The complaint of abdominal pain in a patient that has undergone bariatric surgery should be taken very seriously. In addition to determining the specific procedure performed and date, the patient should be questioned about vomiting, bowel movements, and the presence of blood in stool or vomit. Depending upon the degree of pain present, the patient may need to be given IV opioid analgesia to facilitate a thorough abdominal examination. A rectal examination should be performed to identify occult gastrointestinal bleeding.

These patients require laboratory testing, including CBC, BMP, and other laboratory evaluation as indicated by the history and physical examination. Early consultation with the bariatric surgeon is recommended. Many, if not most, patients with abdominal pain and vomiting will require imaging, usually a CT scan with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis. Because of the difficulty in interpreting the CT scan results in these patients, the bariatric surgeon will often want to personally review the films rather than rely solely on the interpretation by radiology services.

Unfortunately, the EP in this case did not appreciate the seriousness of the situation. The presence of severe abdominal pain, tenderness, guarding, mild tachycardia with leukocytosis, and metabolic acidosis all pointed to a more serious etiology than muscle spasm. This patient required IV fluids, analgesia, and imaging, as well as consultation with the bariatric surgeon.

- Chatzikonstantinou A, Wolf ME, Hennerici MG. Ischemic stroke in young adults: classification and risk factors. J Neurol. 2012;259(4):653-659.

- Ellis C. Stroke in young adults. Disabil Health J. 2010;3(3):222-224.

- Ferro JM, Massaro AR, Mas JL. Aetiological diagnosis of ischemic stroke in young adults. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(11):1085-1096.

- Chan MT, Nadareishvili ZG, Norris JW; Canadian Stroke Consortium. Diagnostic strategies in young patients with ischemic stroke in Canada. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27(2):120-124.

- Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1724-1737.

- Livingston EH. Patient guide: Endocrine and nutritional management after bariatric surgery: A patient’s guide. Hormone Health Network Web site. http://www.hormone.org/~/media/Hormone/Files/Patient%20Guides/Mens%20Health/PGBariatricSurgery_2014.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2014.

- Hussain A, El-Hasani S. Bariatric emergencies: current evidence and strategies of management. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8(1):58.

- Campanille FC, Boru C, Rizzello M, et al. Acute complications after laparoscopic bariatric procedures: update for the general surgeon. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398(5):669-686

Stroke in a Young Man

A 26-year-old man presented to the ED with the chief complaint of mild right-sided weakness, paresthesias, and slurred speech. He stated the onset was sudden—approximately 30 minutes prior to arrival to the ED. The patient denied any previous similar symptoms and was otherwise in good health; he denied taking any medications. He drank alcohol socially, but denied smoking or illicit drug use.

On physical examination, his vital signs and oxygen saturation were normal. Pulmonary, cardiovascular, and abdominal examinations were also normal. The patient thought his speech was somewhat slurred, but the triage nurse and treating emergency physician (EP) had difficulty detecting any altered speech. He was noted to have mild (4+/5) right upper and lower extremity weakness; no facial droop was detected. The patient did have a mild pronator drift of the right upper extremity. Gait testing revealed a mild limp of the right lower extremity.

The EP consulted the hospitalist, and the patient was admitted to a monitored bed. The following morning, a brain magnetic resonance image revealed an ischemic stroke in the distribution of the left middle cerebral artery. The patient’s hospital course was uncomplicated, but at the time of discharge, he continued to have mild right-sided weakness and required the use of a cane.

The patient sued the hospital and the EP for negligence in failing to treat his condition in a timely manner and for not consulting a neurologist. The plaintiff’s attorneys argued the patient should have been given tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which would have avoided the residual right-sided weakness. The defense denied negligence and argued the patient’s symptoms could have been due to several things for which tPA would have been an inappropriate treatment. A defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

Stroke in young patients is relatively rare. With “young” defined as aged 18 to 45 years, this population accounts for approximately 2% to 12% of cerebral infarcts.1 In one nationwide US study of stroke in young adults, Ellis2 found that 4.9% of individuals experiencing a stroke in 2007 were between ages 18 and 44 years. Among this group, 78% experienced an ischemic stroke; 11.2% experienced a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH); and 10.8% had an intracerebral hemorrhage.2

While the clinical presentation of stroke in young adults is similar to that of older patients, the etiologies and risk factors are very different. In older patients, atherosclerosis is the major cause of ischemic stroke. In studies of young adults with ischemic stroke, cardioembolism was found to be the leading cause. Under this category, a patent foramen ovale (PFO) was considered a common cause, followed by atrial fibrillation, bacterial endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, and atrial myxoma. There is, however, increasing controversy over the role of PFO as an etiology of stroke. Many investigators think its role has been overstated and is probably more of an incidental finding than a causal relationship.3 Patients with a suspected cardioembolic etiology will usually require an echocardiogram (with saline contrast or a “bubble study” for suspected PFO), cardiac monitoring, and a possible Holter monitor at the time of discharge (to detect paroxysmal arrhythmias).

Following cardioembolic etiologies, arterial dissection is the next most common category.4 In one study of patients aged 31 to 45 years old, arterial dissection was the most common cause of ischemic stroke.4 Clinical features suggesting dissection include a history of head or neck trauma (even minor trauma), headache or neck pain, and local neurological findings (eg, cranial nerve palsy or Horner syndrome).3 Unfortunately, only about 25% of patients volunteer a history of recent neck trauma. If a cervical or vertebral artery dissection is suspected, contrast enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is the most sensitive and specific test, followed by carotid ultrasound and CT angiography.3

Traditional risk factors for stroke include hypertension and diabetes mellitus (DM). This is not true for younger adults that experience an ischemic stroke. Cigarette smoking is a very important risk factor for cerebrovascular accident in young adults; in addition, the more one smokes, the greater the risk. Other risk factors in young adults include history of migraine headaches (especially migraine with aura), pregnancy and the postpartum period, and illicit drug use.3

The defense’s argument that there are many causes of stroke in young adults that would be inappropriate for treatment with tPA, such as a PFO, carotid dissection or bacterial endocarditis, is absolutely true. Young patients need to be aggressively worked up for the etiology of their stroke, and may require additional testing, such as an MRA, echocardiogram, or Holter monitoring to determine the underlying cause of their stroke.

Obstruction Following Gastric Bypass Surgery

A 47-year-old woman presented to the ED complaining of severe back and abdominal pain. Onset had been gradual and began approximately 4 hours prior to arrival. She described the pain as crampy and constant. The patient had vomited twice; she denied diarrhea and had a normal bowel movement the previous day. She denied any vaginal or urinary complaints. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension and status post gastric bypass surgery 6 months prior. She had lost 42 pounds to date. She denied smoking or alcohol use.

The patient’s vital signs on physical examination were: blood pressure, 154/92 mm Hg; pulse, 106 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute; and temperature, 99˚F. Oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The patient’s lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. The heart was mildly tachycardic, with a regular rhythm and without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The abdominal examination revealed diffuse tenderness and involuntary guarding. There was no distention or rebound. Bowel sounds were present but hypoactive. Examination of the back revealed bilateral paraspinal muscle tenderness without costovertebral angle tenderness.

The EP ordered a CBC, BMP, serum lipase, and a urinalysis. The patient was given an intravenous (IV) bolus of 250 cc normal saline in addition to IV morphine 4 mg and IV ondansetron 4 mg. Her white blood cell (WBC) count was slightly elevated at 12.2 g/dL, with a normal differential. The remainder of the laboratory studies were normal, except for a serum bicarbonate of 22 mmol/L.

The patient stated she felt somewhat improved, but continued to have abdominal and back pain. The EP admitted her to the hospital for observation and pain control. She died the following day from a bowel obstruction. The family sued the EP for negligence in failing to order appropriate testing and for not consulting with specialists to diagnose the bowel obstruction, which is a known complication of gastric bypass surgery. The jury returned a verdict of $2.4 million against the EP.

Discussion

The frequency of bariatric surgery in the United States continues to increase, primarily due to its success with regard to weight loss, but also because of its demonstrated improvement in hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 DM.1

Frequently, the term “gastric bypass surgery” is used interchangeably with bariatric surgery. However, the EP must realize these terms encompass multiple different operations. The four most common types of bariatric surgery in the United Stated are (1) adjustable gastric banding (AGB); (2) the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB); (3) biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS); and (4) vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG).2 (See the Table for a brief explanation of each type of procedure.)

Since each procedure has its own respective associated complications, it is important for the EP to know which the type of gastric bypass surgery the patient had. For example, leakage is much more frequent following RYGB than in gastric banding, while slippage and obstruction are the most common complications of gastric banding.3,4 It is also very helpful to know the specific type of procedure when discussing the case with the surgical consultant.

Based on a recent review of over 800,000 bariatric surgery patients, seven serious common complications following the surgery were identified.3 These included bleeding, leakage, obstruction, stomal ulceration, pulmonary embolism and respiratory complications, blood sugar disturbances (usually hypoglycemia and/or metabolic acidosis), and nutritional disturbances. While not all-inclusive, this list represents the most common serious complications of gastric bypass surgery.

The complaint of abdominal pain in a patient that has undergone bariatric surgery should be taken very seriously. In addition to determining the specific procedure performed and date, the patient should be questioned about vomiting, bowel movements, and the presence of blood in stool or vomit. Depending upon the degree of pain present, the patient may need to be given IV opioid analgesia to facilitate a thorough abdominal examination. A rectal examination should be performed to identify occult gastrointestinal bleeding.

These patients require laboratory testing, including CBC, BMP, and other laboratory evaluation as indicated by the history and physical examination. Early consultation with the bariatric surgeon is recommended. Many, if not most, patients with abdominal pain and vomiting will require imaging, usually a CT scan with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis. Because of the difficulty in interpreting the CT scan results in these patients, the bariatric surgeon will often want to personally review the films rather than rely solely on the interpretation by radiology services.

Unfortunately, the EP in this case did not appreciate the seriousness of the situation. The presence of severe abdominal pain, tenderness, guarding, mild tachycardia with leukocytosis, and metabolic acidosis all pointed to a more serious etiology than muscle spasm. This patient required IV fluids, analgesia, and imaging, as well as consultation with the bariatric surgeon.

Stroke in a Young Man

A 26-year-old man presented to the ED with the chief complaint of mild right-sided weakness, paresthesias, and slurred speech. He stated the onset was sudden—approximately 30 minutes prior to arrival to the ED. The patient denied any previous similar symptoms and was otherwise in good health; he denied taking any medications. He drank alcohol socially, but denied smoking or illicit drug use.

On physical examination, his vital signs and oxygen saturation were normal. Pulmonary, cardiovascular, and abdominal examinations were also normal. The patient thought his speech was somewhat slurred, but the triage nurse and treating emergency physician (EP) had difficulty detecting any altered speech. He was noted to have mild (4+/5) right upper and lower extremity weakness; no facial droop was detected. The patient did have a mild pronator drift of the right upper extremity. Gait testing revealed a mild limp of the right lower extremity.

The EP consulted the hospitalist, and the patient was admitted to a monitored bed. The following morning, a brain magnetic resonance image revealed an ischemic stroke in the distribution of the left middle cerebral artery. The patient’s hospital course was uncomplicated, but at the time of discharge, he continued to have mild right-sided weakness and required the use of a cane.

The patient sued the hospital and the EP for negligence in failing to treat his condition in a timely manner and for not consulting a neurologist. The plaintiff’s attorneys argued the patient should have been given tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which would have avoided the residual right-sided weakness. The defense denied negligence and argued the patient’s symptoms could have been due to several things for which tPA would have been an inappropriate treatment. A defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

Stroke in young patients is relatively rare. With “young” defined as aged 18 to 45 years, this population accounts for approximately 2% to 12% of cerebral infarcts.1 In one nationwide US study of stroke in young adults, Ellis2 found that 4.9% of individuals experiencing a stroke in 2007 were between ages 18 and 44 years. Among this group, 78% experienced an ischemic stroke; 11.2% experienced a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH); and 10.8% had an intracerebral hemorrhage.2

While the clinical presentation of stroke in young adults is similar to that of older patients, the etiologies and risk factors are very different. In older patients, atherosclerosis is the major cause of ischemic stroke. In studies of young adults with ischemic stroke, cardioembolism was found to be the leading cause. Under this category, a patent foramen ovale (PFO) was considered a common cause, followed by atrial fibrillation, bacterial endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, and atrial myxoma. There is, however, increasing controversy over the role of PFO as an etiology of stroke. Many investigators think its role has been overstated and is probably more of an incidental finding than a causal relationship.3 Patients with a suspected cardioembolic etiology will usually require an echocardiogram (with saline contrast or a “bubble study” for suspected PFO), cardiac monitoring, and a possible Holter monitor at the time of discharge (to detect paroxysmal arrhythmias).

Following cardioembolic etiologies, arterial dissection is the next most common category.4 In one study of patients aged 31 to 45 years old, arterial dissection was the most common cause of ischemic stroke.4 Clinical features suggesting dissection include a history of head or neck trauma (even minor trauma), headache or neck pain, and local neurological findings (eg, cranial nerve palsy or Horner syndrome).3 Unfortunately, only about 25% of patients volunteer a history of recent neck trauma. If a cervical or vertebral artery dissection is suspected, contrast enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is the most sensitive and specific test, followed by carotid ultrasound and CT angiography.3

Traditional risk factors for stroke include hypertension and diabetes mellitus (DM). This is not true for younger adults that experience an ischemic stroke. Cigarette smoking is a very important risk factor for cerebrovascular accident in young adults; in addition, the more one smokes, the greater the risk. Other risk factors in young adults include history of migraine headaches (especially migraine with aura), pregnancy and the postpartum period, and illicit drug use.3

The defense’s argument that there are many causes of stroke in young adults that would be inappropriate for treatment with tPA, such as a PFO, carotid dissection or bacterial endocarditis, is absolutely true. Young patients need to be aggressively worked up for the etiology of their stroke, and may require additional testing, such as an MRA, echocardiogram, or Holter monitoring to determine the underlying cause of their stroke.

Obstruction Following Gastric Bypass Surgery

A 47-year-old woman presented to the ED complaining of severe back and abdominal pain. Onset had been gradual and began approximately 4 hours prior to arrival. She described the pain as crampy and constant. The patient had vomited twice; she denied diarrhea and had a normal bowel movement the previous day. She denied any vaginal or urinary complaints. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension and status post gastric bypass surgery 6 months prior. She had lost 42 pounds to date. She denied smoking or alcohol use.

The patient’s vital signs on physical examination were: blood pressure, 154/92 mm Hg; pulse, 106 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute; and temperature, 99˚F. Oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The patient’s lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. The heart was mildly tachycardic, with a regular rhythm and without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The abdominal examination revealed diffuse tenderness and involuntary guarding. There was no distention or rebound. Bowel sounds were present but hypoactive. Examination of the back revealed bilateral paraspinal muscle tenderness without costovertebral angle tenderness.

The EP ordered a CBC, BMP, serum lipase, and a urinalysis. The patient was given an intravenous (IV) bolus of 250 cc normal saline in addition to IV morphine 4 mg and IV ondansetron 4 mg. Her white blood cell (WBC) count was slightly elevated at 12.2 g/dL, with a normal differential. The remainder of the laboratory studies were normal, except for a serum bicarbonate of 22 mmol/L.

The patient stated she felt somewhat improved, but continued to have abdominal and back pain. The EP admitted her to the hospital for observation and pain control. She died the following day from a bowel obstruction. The family sued the EP for negligence in failing to order appropriate testing and for not consulting with specialists to diagnose the bowel obstruction, which is a known complication of gastric bypass surgery. The jury returned a verdict of $2.4 million against the EP.

Discussion

The frequency of bariatric surgery in the United States continues to increase, primarily due to its success with regard to weight loss, but also because of its demonstrated improvement in hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 DM.1

Frequently, the term “gastric bypass surgery” is used interchangeably with bariatric surgery. However, the EP must realize these terms encompass multiple different operations. The four most common types of bariatric surgery in the United Stated are (1) adjustable gastric banding (AGB); (2) the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB); (3) biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS); and (4) vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG).2 (See the Table for a brief explanation of each type of procedure.)

Since each procedure has its own respective associated complications, it is important for the EP to know which the type of gastric bypass surgery the patient had. For example, leakage is much more frequent following RYGB than in gastric banding, while slippage and obstruction are the most common complications of gastric banding.3,4 It is also very helpful to know the specific type of procedure when discussing the case with the surgical consultant.

Based on a recent review of over 800,000 bariatric surgery patients, seven serious common complications following the surgery were identified.3 These included bleeding, leakage, obstruction, stomal ulceration, pulmonary embolism and respiratory complications, blood sugar disturbances (usually hypoglycemia and/or metabolic acidosis), and nutritional disturbances. While not all-inclusive, this list represents the most common serious complications of gastric bypass surgery.

The complaint of abdominal pain in a patient that has undergone bariatric surgery should be taken very seriously. In addition to determining the specific procedure performed and date, the patient should be questioned about vomiting, bowel movements, and the presence of blood in stool or vomit. Depending upon the degree of pain present, the patient may need to be given IV opioid analgesia to facilitate a thorough abdominal examination. A rectal examination should be performed to identify occult gastrointestinal bleeding.

These patients require laboratory testing, including CBC, BMP, and other laboratory evaluation as indicated by the history and physical examination. Early consultation with the bariatric surgeon is recommended. Many, if not most, patients with abdominal pain and vomiting will require imaging, usually a CT scan with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis. Because of the difficulty in interpreting the CT scan results in these patients, the bariatric surgeon will often want to personally review the films rather than rely solely on the interpretation by radiology services.

Unfortunately, the EP in this case did not appreciate the seriousness of the situation. The presence of severe abdominal pain, tenderness, guarding, mild tachycardia with leukocytosis, and metabolic acidosis all pointed to a more serious etiology than muscle spasm. This patient required IV fluids, analgesia, and imaging, as well as consultation with the bariatric surgeon.

- Chatzikonstantinou A, Wolf ME, Hennerici MG. Ischemic stroke in young adults: classification and risk factors. J Neurol. 2012;259(4):653-659.

- Ellis C. Stroke in young adults. Disabil Health J. 2010;3(3):222-224.

- Ferro JM, Massaro AR, Mas JL. Aetiological diagnosis of ischemic stroke in young adults. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(11):1085-1096.

- Chan MT, Nadareishvili ZG, Norris JW; Canadian Stroke Consortium. Diagnostic strategies in young patients with ischemic stroke in Canada. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27(2):120-124.

- Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1724-1737.

- Livingston EH. Patient guide: Endocrine and nutritional management after bariatric surgery: A patient’s guide. Hormone Health Network Web site. http://www.hormone.org/~/media/Hormone/Files/Patient%20Guides/Mens%20Health/PGBariatricSurgery_2014.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2014.

- Hussain A, El-Hasani S. Bariatric emergencies: current evidence and strategies of management. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8(1):58.

- Campanille FC, Boru C, Rizzello M, et al. Acute complications after laparoscopic bariatric procedures: update for the general surgeon. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398(5):669-686

- Chatzikonstantinou A, Wolf ME, Hennerici MG. Ischemic stroke in young adults: classification and risk factors. J Neurol. 2012;259(4):653-659.

- Ellis C. Stroke in young adults. Disabil Health J. 2010;3(3):222-224.

- Ferro JM, Massaro AR, Mas JL. Aetiological diagnosis of ischemic stroke in young adults. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(11):1085-1096.

- Chan MT, Nadareishvili ZG, Norris JW; Canadian Stroke Consortium. Diagnostic strategies in young patients with ischemic stroke in Canada. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27(2):120-124.

- Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1724-1737.

- Livingston EH. Patient guide: Endocrine and nutritional management after bariatric surgery: A patient’s guide. Hormone Health Network Web site. http://www.hormone.org/~/media/Hormone/Files/Patient%20Guides/Mens%20Health/PGBariatricSurgery_2014.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2014.

- Hussain A, El-Hasani S. Bariatric emergencies: current evidence and strategies of management. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8(1):58.

- Campanille FC, Boru C, Rizzello M, et al. Acute complications after laparoscopic bariatric procedures: update for the general surgeon. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398(5):669-686

Spontaneous, Chronic Expanding Posterior Thigh Hematoma Mimicking Soft-Tissue Sarcoma in a Morbidly Obese Pregnant Woman

Soft-tissue sarcomas are quite rare, with an annual incidence of 20 to 30 per 1,000,000 persons in the United States.1 Because of their heterogeneous presentation, they remain a diagnostic challenge and are often initially confused for more common, benign disorders.2 Chronic expanding hematoma, first described by Friedlander and colleagues3 in 1968, is a rare entity that is particularly difficult to distinguish from soft-tissue malignancy.3-5 Chronic expanding hematoma is defined as a hematoma that gradually expands over 1 month or longer, is absent of neoplastic change on histologic sections, and does not occur in the setting of coagulopathy.6

Typically associated with remote trauma, these lesions often present as a slowly growing mass on the anterior or lateral thigh, calf, or buttock.3-4,7-9 They have been reported to persist as long as 46 years, with sizes ranging from 3 to 55 cm in maximum diameter.7 On imaging, they have a cystic appearance with a dense fibrous capsule.7-8 Most cases resolve uneventfully after drainage or marginal excision, although some cases require repeated intervention.7 This case report describes a morbidly obese patient with a chronic expanding hematoma in the distal posterior thigh whose definitive treatment was delayed 6 months because of her pregnancy status and inability to lie prone for open biopsy. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 27-year-old morbidly obese woman, who was pregnant at 12 weeks gestation, was seen in an orthopedic oncology clinic with a 1-month history of a slowly growing, painful posterior thigh mass. She had no history of cancer or bleeding disorder, and denied a history of trauma or constitutional symptoms consistent with malignancy. Coagulation studies were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) obtained 2 weeks prior in the emergency room showed a cystic lesion with mass-like components in the posterior compartment of the distal right thigh, measuring 17 cm longitudinally. The lesion was located adjacent to, but not involving, the sciatic nerve and femoral vasculature. On initial examination, the large soft-tissue mass was evident and moderately painful to palpation; no skin changes were noted, and the patient had a normal sensorimotor examination. Fine-needle aspiration was performed, which resulted in amorphous debris consistent with hematoma.

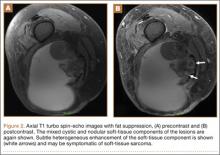

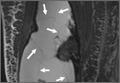

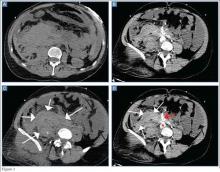

Repeat MRI 2 months later showed increased size of the lesion (9.5×10.5 cm axial, 22.0 cm craniocaudal). Although most findings of a more extensive imaging protocol, including precontrast and postcontrast sequences, were consistent with hematoma, the lesion also had several characteristics that indicated soft-tissue sarcoma. Specifically, findings suggestive of chronic hematoma included the hyperintense short tau inversion recovery (STIR) T1/T2 signal of the cystic component consistent with proteinaceous fluid and the low STIR TI/T2 signal of the periphery consistent with a rim of hemosiderin (Figure 1). Additionally, the cystic component of the lesion had multiple fine septations that are atypical for a hematoma (Figure 1), and several lymph nodes greater than 1.7 cm in short axis were noted in the anterior thigh and hemipelvis that were suspicious of metastatic lymphadenopathy. The encapsulated appearance of the lesion with a sharply defined margin and short transition zone were also reassuring findings for a benign lesion (Figures 1, 2A, 2B). However, several findings were identified that suggested soft-tissue sarcoma, including a nodular soft-tissue component on the medial wall of the lesion that had heterogeneous enhancement with contrast (Figure 2B). We, therefore, proceeded with ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of the mass and cytologic sampling of the fluid components, which were again consistent with hematoma; no evidence of internal vascular flow was noted on Doppler ultrasound. Ultrasound-guided right inguinal lymph node biopsy was also performed and was negative for malignancy. Because of her large body habitus and pregnancy status, it was agreed that open biopsy should be delayed until after delivery to avoid placing the patient in a prone position.

The patient visited the emergency room several times during the following months because of intermittent exacerbations of her lower extremity pain, swelling, and occasional paresthesias. About 6 months after initial presentation, repeat MRI again showed increased size of the mass (13.5×13.5 cm axial, 28 cm craniocaudal). There was also increased displacement of the adjacent neurovascular structures but no evidence of deep vein thrombosis. Because of concerns about the increased symptomatology of her thigh mass and possible sampling error of the previous biopsies, an elective cesarean section was performed at 35 weeks gestation. One week later, after clearance by her obstetrician, we proceeded with open biopsy of the mass in prone position. Initial sampling was negative for malignancy on frozen section; then, we expressed 1.75 L of brown fluid and solidified blood products, irrigated copiously, and placed a surgical drain. The permanent histologic specimens were again consistent with hematoma, and microbial cultures were negative. A week later, the patient accidentally removed her drain, and she presented with a fever (101°F) on postoperative day (POD) 15. Computed tomography showed reaccumulation of fluid; duplex ultrasound was negative. She was placed on cephalexin and underwent ultrasound-guided replacement of the drain with removal of an additional 750 mL fluid on POD 20. She drained an additional 150 to 200 mL/d for 1 month, with marked improvement in her leg swelling and knee range of motion. The drainage decreased during the next 3 weeks, and the drain was removed on POD 75.

Discussion

The presence of a hematoma in the extremities is usually a straightforward diagnosis. However, the unusual circumstances of this case highlight all the indications for investigation for possible soft-tissue sarcoma when a patient presents with what appears to be a benign condition.

Hematomas are rare in the absence of trauma or coagulopathy, with chronic expansion of hematomas rarer still.4,7,10-11 The patient had no evidence of coagulopathy because of her ability to have an uncomplicated pregnancy and elective cesarean section. She denied a history of trauma, and the location of her hematoma at the posterior distal thigh is an uncommon site of injury. In this setting, fine-needle aspiration and serial imaging to assess for progressive increase in lesion size were indicated to rule out malignancy.2

MRI is the gold-standard imaging modality for distinguishing soft-tissue masses from hematomas.5,12-14 Unlike the typical appearance of a hematoma, sarcomas of the soft-tissue extremities are often complex cystic lesions with multiple septations, internal soft-tissue components, and relatively ill-defined margins.15-17 However, as a hematoma becomes chronic, it can develop a fibrinous capsule, and the contents can manifest an atypical, heterogeneous appearance from scattered, progressive accumulation of blood products that is essentially indistinguishable from sarcomas on imaging.5

Because of the expansion of the hematoma and the atypical appearance of the mass on imaging, repeated core biopsy and, eventually, open biopsy were indicated, despite a preliminary negative diagnosis based on fine-needle aspiration. This resulted from the possibility of sampling error that is particularly relevant to cystic sarcomas, because only portions of the mass may be composed of malignant cells.2 An unusual aspect of this case is the regional lymphadenopathy noted on MRI, because regional lymphatic spread is a known mechanism of metastasis in soft-tissue sarcomas.18 However, the inguinal biopsies showed a chronic inflammatory infiltrate and were negative for malignancy, and enlarged nodes were not seen on imaging several months later. It is possible that the lymphadenopathy resulted from an unrelated process; alternatively, it may have been secondary to impaired lymphatic drainage because of mass effect from the hematoma, which also caused temporary lower extremity swelling.

The distal posterior thigh is an unreported location for a chronic expanding hematoma. Our patient developed slowly progressive lower-limb swelling and, eventually, paresthesias because of displacement of the neurovasculature, an unusual sequela that was recently reported in a similar case of an acute spontaneous hematoma in a patient on warfarin.19 Rupture of a Baker cyst is a possible inciting factor in our patient, although the proximal location of the lesion and the clearly defined tissue plane on MRI between the hematoma and the popliteal region make this unlikely. Finally, the patient’s lesion showed no evidence of vascular flow on Doppler ultrasonography, although giant hematomas secondary to popliteal aneurysm rupture have been reported.20-22

Conclusion

This case highlights the features of a chronic expanding hematoma that can suggest soft-tissue sarcoma and shows the recommended diagnostic steps to differentiate the 2 conditions. This case also describes an unreported location for a chronic expanding hematoma with resulting progressive neurovascular displacement caused by mass effect. We recommend careful monitoring of patients with similarly expansile lesions in this region for signs of neurovascular compromise.

1. O’Sullivan B, Pisters PW. Staging and prognostic factor evaluation in soft tissue sarcoma. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003;12(2):333-353.

2. Rougraff B. The diagnosis and management of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities in the adult. Curr Probl Cancer. 1999;23(1):1-50.

3. Friedlander HL, Bump RG. Chronic expanding hematoma of the calf. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1968;50(6):1237-1241.

4. Liu CW, Kuo CL, Tsai TY, Lin LC, Wu CC. Massive gluteal mass mimicking sarcoma: chronic expanding hematoma. Formosan J Musculoskeletal Disord. 2011;2(3):106-108.

5. Taieb S, Penel N, Vanseymortier L, Ceugnart L. Soft tissue sarcomas or intramuscular haematomas? Eur J Radiol. 2009;72(1):44-49.

6. Reid JD, Kommareddi S, Lankerani M, Park MC. Chronic expanding hematomas. A clinicopathologic entity. JAMA. 1980;244(21):2441-2442.

7. Okada K, Sugiyama T, Kato H, Tani T. Chronic expanding hematoma mimicking soft tissue neoplasm. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2971-2972.

8. Negoro K, Uchida K, Yayama T, Kokubo Y, Baba H. Chronic expanding hematoma of the thigh. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(2):192-194.

9. Goddard MS, Vakil JJ, McCarthy EF, Khanuja HS. Chronic expanding hematoma of the lateral thigh and massive bony destruction after a failed total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(2):338.e13-.e15.

10. Radford DM, Schuh ME, Nambisan RN, Karakousis CP. Pseudo-tumor of the calf. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1993;19(3):300-301.

11. Mann HA, Hilton A, Goddard NJ, Smith MA, Holloway B, Lee CA. Synovial sarcoma mimicking haemophilic pseudotumour. Sarcoma. 2006;2006:27212.

12. Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD. Radiologic evaluation of soft-tissue masses: a current perspective. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(3):575-587.

13. Vanel D, Verstraete KL, Shapeero LG. Primary tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Radiol Clin North Am. 1997;35(1):213-237.

14. Siegel MJ. Magnetic resonance imaging of musculoskeletal soft tissue masses. Radiol Clin North Am. 2001;39(4):701-720.

15. O’Connor EE, Dixon LB, Peabody T, Stacy GS. MRI of cystic and soft-tissue masses of the shoulder joint. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(1):39-47.

16. Bermejo A, De Bustamante TD, Martinez A, Carrera R, Zabia E, Manjon P. MR imaging in the evaluation of cystic-appearing soft-tissue masses of the extremities. Radiographics. 2013;33(3):833-855.

17. Morrison C, Wakely PE Jr, Ashman CJ, Lemley D, Theil K. Cystic synovial sarcoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2001;5(1):48-56.

18. Eilber FC, Rosen G, Nelson SD, et al. High-grade extremity soft tissue sarcomas: factors predictive of local recurrence and its effect on morbidity and mortality. Ann Surg. 2003;237(2):218-226.

19. Kuo CH. Peripheral neuropathy and lower limb swelling caused by a giant popliteal fossa hematoma. Neurol Sci. 2012;33(2):475-476.

20. Reijnen MM, de Rhoter W, Zeebregts CJ. Treatment of a symptomatic popliteal pseudoaneurysm using a stent-graft and ultrasound-guided evacuation of the haematoma. Emerg Radiol. 2009;16(2):167-169.

21. Rossi FH, Veith FJ, Lipsitz EC, Izukawa NM, Oliveira LA, Silva DG. Giant femoropopliteal artery aneurysm and vein rupture. Vascular. 2004;12(4):263-265.

22. Lamoca LM, Alerany MB, Hernando LL. Endovascular therapy for a ruptured popliteal aneurysm. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;75(3):427-429.

Soft-tissue sarcomas are quite rare, with an annual incidence of 20 to 30 per 1,000,000 persons in the United States.1 Because of their heterogeneous presentation, they remain a diagnostic challenge and are often initially confused for more common, benign disorders.2 Chronic expanding hematoma, first described by Friedlander and colleagues3 in 1968, is a rare entity that is particularly difficult to distinguish from soft-tissue malignancy.3-5 Chronic expanding hematoma is defined as a hematoma that gradually expands over 1 month or longer, is absent of neoplastic change on histologic sections, and does not occur in the setting of coagulopathy.6

Typically associated with remote trauma, these lesions often present as a slowly growing mass on the anterior or lateral thigh, calf, or buttock.3-4,7-9 They have been reported to persist as long as 46 years, with sizes ranging from 3 to 55 cm in maximum diameter.7 On imaging, they have a cystic appearance with a dense fibrous capsule.7-8 Most cases resolve uneventfully after drainage or marginal excision, although some cases require repeated intervention.7 This case report describes a morbidly obese patient with a chronic expanding hematoma in the distal posterior thigh whose definitive treatment was delayed 6 months because of her pregnancy status and inability to lie prone for open biopsy. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 27-year-old morbidly obese woman, who was pregnant at 12 weeks gestation, was seen in an orthopedic oncology clinic with a 1-month history of a slowly growing, painful posterior thigh mass. She had no history of cancer or bleeding disorder, and denied a history of trauma or constitutional symptoms consistent with malignancy. Coagulation studies were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) obtained 2 weeks prior in the emergency room showed a cystic lesion with mass-like components in the posterior compartment of the distal right thigh, measuring 17 cm longitudinally. The lesion was located adjacent to, but not involving, the sciatic nerve and femoral vasculature. On initial examination, the large soft-tissue mass was evident and moderately painful to palpation; no skin changes were noted, and the patient had a normal sensorimotor examination. Fine-needle aspiration was performed, which resulted in amorphous debris consistent with hematoma.

Repeat MRI 2 months later showed increased size of the lesion (9.5×10.5 cm axial, 22.0 cm craniocaudal). Although most findings of a more extensive imaging protocol, including precontrast and postcontrast sequences, were consistent with hematoma, the lesion also had several characteristics that indicated soft-tissue sarcoma. Specifically, findings suggestive of chronic hematoma included the hyperintense short tau inversion recovery (STIR) T1/T2 signal of the cystic component consistent with proteinaceous fluid and the low STIR TI/T2 signal of the periphery consistent with a rim of hemosiderin (Figure 1). Additionally, the cystic component of the lesion had multiple fine septations that are atypical for a hematoma (Figure 1), and several lymph nodes greater than 1.7 cm in short axis were noted in the anterior thigh and hemipelvis that were suspicious of metastatic lymphadenopathy. The encapsulated appearance of the lesion with a sharply defined margin and short transition zone were also reassuring findings for a benign lesion (Figures 1, 2A, 2B). However, several findings were identified that suggested soft-tissue sarcoma, including a nodular soft-tissue component on the medial wall of the lesion that had heterogeneous enhancement with contrast (Figure 2B). We, therefore, proceeded with ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of the mass and cytologic sampling of the fluid components, which were again consistent with hematoma; no evidence of internal vascular flow was noted on Doppler ultrasound. Ultrasound-guided right inguinal lymph node biopsy was also performed and was negative for malignancy. Because of her large body habitus and pregnancy status, it was agreed that open biopsy should be delayed until after delivery to avoid placing the patient in a prone position.

The patient visited the emergency room several times during the following months because of intermittent exacerbations of her lower extremity pain, swelling, and occasional paresthesias. About 6 months after initial presentation, repeat MRI again showed increased size of the mass (13.5×13.5 cm axial, 28 cm craniocaudal). There was also increased displacement of the adjacent neurovascular structures but no evidence of deep vein thrombosis. Because of concerns about the increased symptomatology of her thigh mass and possible sampling error of the previous biopsies, an elective cesarean section was performed at 35 weeks gestation. One week later, after clearance by her obstetrician, we proceeded with open biopsy of the mass in prone position. Initial sampling was negative for malignancy on frozen section; then, we expressed 1.75 L of brown fluid and solidified blood products, irrigated copiously, and placed a surgical drain. The permanent histologic specimens were again consistent with hematoma, and microbial cultures were negative. A week later, the patient accidentally removed her drain, and she presented with a fever (101°F) on postoperative day (POD) 15. Computed tomography showed reaccumulation of fluid; duplex ultrasound was negative. She was placed on cephalexin and underwent ultrasound-guided replacement of the drain with removal of an additional 750 mL fluid on POD 20. She drained an additional 150 to 200 mL/d for 1 month, with marked improvement in her leg swelling and knee range of motion. The drainage decreased during the next 3 weeks, and the drain was removed on POD 75.

Discussion

The presence of a hematoma in the extremities is usually a straightforward diagnosis. However, the unusual circumstances of this case highlight all the indications for investigation for possible soft-tissue sarcoma when a patient presents with what appears to be a benign condition.

Hematomas are rare in the absence of trauma or coagulopathy, with chronic expansion of hematomas rarer still.4,7,10-11 The patient had no evidence of coagulopathy because of her ability to have an uncomplicated pregnancy and elective cesarean section. She denied a history of trauma, and the location of her hematoma at the posterior distal thigh is an uncommon site of injury. In this setting, fine-needle aspiration and serial imaging to assess for progressive increase in lesion size were indicated to rule out malignancy.2

MRI is the gold-standard imaging modality for distinguishing soft-tissue masses from hematomas.5,12-14 Unlike the typical appearance of a hematoma, sarcomas of the soft-tissue extremities are often complex cystic lesions with multiple septations, internal soft-tissue components, and relatively ill-defined margins.15-17 However, as a hematoma becomes chronic, it can develop a fibrinous capsule, and the contents can manifest an atypical, heterogeneous appearance from scattered, progressive accumulation of blood products that is essentially indistinguishable from sarcomas on imaging.5

Because of the expansion of the hematoma and the atypical appearance of the mass on imaging, repeated core biopsy and, eventually, open biopsy were indicated, despite a preliminary negative diagnosis based on fine-needle aspiration. This resulted from the possibility of sampling error that is particularly relevant to cystic sarcomas, because only portions of the mass may be composed of malignant cells.2 An unusual aspect of this case is the regional lymphadenopathy noted on MRI, because regional lymphatic spread is a known mechanism of metastasis in soft-tissue sarcomas.18 However, the inguinal biopsies showed a chronic inflammatory infiltrate and were negative for malignancy, and enlarged nodes were not seen on imaging several months later. It is possible that the lymphadenopathy resulted from an unrelated process; alternatively, it may have been secondary to impaired lymphatic drainage because of mass effect from the hematoma, which also caused temporary lower extremity swelling.

The distal posterior thigh is an unreported location for a chronic expanding hematoma. Our patient developed slowly progressive lower-limb swelling and, eventually, paresthesias because of displacement of the neurovasculature, an unusual sequela that was recently reported in a similar case of an acute spontaneous hematoma in a patient on warfarin.19 Rupture of a Baker cyst is a possible inciting factor in our patient, although the proximal location of the lesion and the clearly defined tissue plane on MRI between the hematoma and the popliteal region make this unlikely. Finally, the patient’s lesion showed no evidence of vascular flow on Doppler ultrasonography, although giant hematomas secondary to popliteal aneurysm rupture have been reported.20-22

Conclusion

This case highlights the features of a chronic expanding hematoma that can suggest soft-tissue sarcoma and shows the recommended diagnostic steps to differentiate the 2 conditions. This case also describes an unreported location for a chronic expanding hematoma with resulting progressive neurovascular displacement caused by mass effect. We recommend careful monitoring of patients with similarly expansile lesions in this region for signs of neurovascular compromise.

Soft-tissue sarcomas are quite rare, with an annual incidence of 20 to 30 per 1,000,000 persons in the United States.1 Because of their heterogeneous presentation, they remain a diagnostic challenge and are often initially confused for more common, benign disorders.2 Chronic expanding hematoma, first described by Friedlander and colleagues3 in 1968, is a rare entity that is particularly difficult to distinguish from soft-tissue malignancy.3-5 Chronic expanding hematoma is defined as a hematoma that gradually expands over 1 month or longer, is absent of neoplastic change on histologic sections, and does not occur in the setting of coagulopathy.6

Typically associated with remote trauma, these lesions often present as a slowly growing mass on the anterior or lateral thigh, calf, or buttock.3-4,7-9 They have been reported to persist as long as 46 years, with sizes ranging from 3 to 55 cm in maximum diameter.7 On imaging, they have a cystic appearance with a dense fibrous capsule.7-8 Most cases resolve uneventfully after drainage or marginal excision, although some cases require repeated intervention.7 This case report describes a morbidly obese patient with a chronic expanding hematoma in the distal posterior thigh whose definitive treatment was delayed 6 months because of her pregnancy status and inability to lie prone for open biopsy. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 27-year-old morbidly obese woman, who was pregnant at 12 weeks gestation, was seen in an orthopedic oncology clinic with a 1-month history of a slowly growing, painful posterior thigh mass. She had no history of cancer or bleeding disorder, and denied a history of trauma or constitutional symptoms consistent with malignancy. Coagulation studies were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) obtained 2 weeks prior in the emergency room showed a cystic lesion with mass-like components in the posterior compartment of the distal right thigh, measuring 17 cm longitudinally. The lesion was located adjacent to, but not involving, the sciatic nerve and femoral vasculature. On initial examination, the large soft-tissue mass was evident and moderately painful to palpation; no skin changes were noted, and the patient had a normal sensorimotor examination. Fine-needle aspiration was performed, which resulted in amorphous debris consistent with hematoma.

Repeat MRI 2 months later showed increased size of the lesion (9.5×10.5 cm axial, 22.0 cm craniocaudal). Although most findings of a more extensive imaging protocol, including precontrast and postcontrast sequences, were consistent with hematoma, the lesion also had several characteristics that indicated soft-tissue sarcoma. Specifically, findings suggestive of chronic hematoma included the hyperintense short tau inversion recovery (STIR) T1/T2 signal of the cystic component consistent with proteinaceous fluid and the low STIR TI/T2 signal of the periphery consistent with a rim of hemosiderin (Figure 1). Additionally, the cystic component of the lesion had multiple fine septations that are atypical for a hematoma (Figure 1), and several lymph nodes greater than 1.7 cm in short axis were noted in the anterior thigh and hemipelvis that were suspicious of metastatic lymphadenopathy. The encapsulated appearance of the lesion with a sharply defined margin and short transition zone were also reassuring findings for a benign lesion (Figures 1, 2A, 2B). However, several findings were identified that suggested soft-tissue sarcoma, including a nodular soft-tissue component on the medial wall of the lesion that had heterogeneous enhancement with contrast (Figure 2B). We, therefore, proceeded with ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of the mass and cytologic sampling of the fluid components, which were again consistent with hematoma; no evidence of internal vascular flow was noted on Doppler ultrasound. Ultrasound-guided right inguinal lymph node biopsy was also performed and was negative for malignancy. Because of her large body habitus and pregnancy status, it was agreed that open biopsy should be delayed until after delivery to avoid placing the patient in a prone position.

The patient visited the emergency room several times during the following months because of intermittent exacerbations of her lower extremity pain, swelling, and occasional paresthesias. About 6 months after initial presentation, repeat MRI again showed increased size of the mass (13.5×13.5 cm axial, 28 cm craniocaudal). There was also increased displacement of the adjacent neurovascular structures but no evidence of deep vein thrombosis. Because of concerns about the increased symptomatology of her thigh mass and possible sampling error of the previous biopsies, an elective cesarean section was performed at 35 weeks gestation. One week later, after clearance by her obstetrician, we proceeded with open biopsy of the mass in prone position. Initial sampling was negative for malignancy on frozen section; then, we expressed 1.75 L of brown fluid and solidified blood products, irrigated copiously, and placed a surgical drain. The permanent histologic specimens were again consistent with hematoma, and microbial cultures were negative. A week later, the patient accidentally removed her drain, and she presented with a fever (101°F) on postoperative day (POD) 15. Computed tomography showed reaccumulation of fluid; duplex ultrasound was negative. She was placed on cephalexin and underwent ultrasound-guided replacement of the drain with removal of an additional 750 mL fluid on POD 20. She drained an additional 150 to 200 mL/d for 1 month, with marked improvement in her leg swelling and knee range of motion. The drainage decreased during the next 3 weeks, and the drain was removed on POD 75.

Discussion

The presence of a hematoma in the extremities is usually a straightforward diagnosis. However, the unusual circumstances of this case highlight all the indications for investigation for possible soft-tissue sarcoma when a patient presents with what appears to be a benign condition.

Hematomas are rare in the absence of trauma or coagulopathy, with chronic expansion of hematomas rarer still.4,7,10-11 The patient had no evidence of coagulopathy because of her ability to have an uncomplicated pregnancy and elective cesarean section. She denied a history of trauma, and the location of her hematoma at the posterior distal thigh is an uncommon site of injury. In this setting, fine-needle aspiration and serial imaging to assess for progressive increase in lesion size were indicated to rule out malignancy.2

MRI is the gold-standard imaging modality for distinguishing soft-tissue masses from hematomas.5,12-14 Unlike the typical appearance of a hematoma, sarcomas of the soft-tissue extremities are often complex cystic lesions with multiple septations, internal soft-tissue components, and relatively ill-defined margins.15-17 However, as a hematoma becomes chronic, it can develop a fibrinous capsule, and the contents can manifest an atypical, heterogeneous appearance from scattered, progressive accumulation of blood products that is essentially indistinguishable from sarcomas on imaging.5

Because of the expansion of the hematoma and the atypical appearance of the mass on imaging, repeated core biopsy and, eventually, open biopsy were indicated, despite a preliminary negative diagnosis based on fine-needle aspiration. This resulted from the possibility of sampling error that is particularly relevant to cystic sarcomas, because only portions of the mass may be composed of malignant cells.2 An unusual aspect of this case is the regional lymphadenopathy noted on MRI, because regional lymphatic spread is a known mechanism of metastasis in soft-tissue sarcomas.18 However, the inguinal biopsies showed a chronic inflammatory infiltrate and were negative for malignancy, and enlarged nodes were not seen on imaging several months later. It is possible that the lymphadenopathy resulted from an unrelated process; alternatively, it may have been secondary to impaired lymphatic drainage because of mass effect from the hematoma, which also caused temporary lower extremity swelling.

The distal posterior thigh is an unreported location for a chronic expanding hematoma. Our patient developed slowly progressive lower-limb swelling and, eventually, paresthesias because of displacement of the neurovasculature, an unusual sequela that was recently reported in a similar case of an acute spontaneous hematoma in a patient on warfarin.19 Rupture of a Baker cyst is a possible inciting factor in our patient, although the proximal location of the lesion and the clearly defined tissue plane on MRI between the hematoma and the popliteal region make this unlikely. Finally, the patient’s lesion showed no evidence of vascular flow on Doppler ultrasonography, although giant hematomas secondary to popliteal aneurysm rupture have been reported.20-22

Conclusion

This case highlights the features of a chronic expanding hematoma that can suggest soft-tissue sarcoma and shows the recommended diagnostic steps to differentiate the 2 conditions. This case also describes an unreported location for a chronic expanding hematoma with resulting progressive neurovascular displacement caused by mass effect. We recommend careful monitoring of patients with similarly expansile lesions in this region for signs of neurovascular compromise.

1. O’Sullivan B, Pisters PW. Staging and prognostic factor evaluation in soft tissue sarcoma. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003;12(2):333-353.

2. Rougraff B. The diagnosis and management of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities in the adult. Curr Probl Cancer. 1999;23(1):1-50.

3. Friedlander HL, Bump RG. Chronic expanding hematoma of the calf. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1968;50(6):1237-1241.

4. Liu CW, Kuo CL, Tsai TY, Lin LC, Wu CC. Massive gluteal mass mimicking sarcoma: chronic expanding hematoma. Formosan J Musculoskeletal Disord. 2011;2(3):106-108.

5. Taieb S, Penel N, Vanseymortier L, Ceugnart L. Soft tissue sarcomas or intramuscular haematomas? Eur J Radiol. 2009;72(1):44-49.

6. Reid JD, Kommareddi S, Lankerani M, Park MC. Chronic expanding hematomas. A clinicopathologic entity. JAMA. 1980;244(21):2441-2442.

7. Okada K, Sugiyama T, Kato H, Tani T. Chronic expanding hematoma mimicking soft tissue neoplasm. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2971-2972.

8. Negoro K, Uchida K, Yayama T, Kokubo Y, Baba H. Chronic expanding hematoma of the thigh. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(2):192-194.

9. Goddard MS, Vakil JJ, McCarthy EF, Khanuja HS. Chronic expanding hematoma of the lateral thigh and massive bony destruction after a failed total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(2):338.e13-.e15.

10. Radford DM, Schuh ME, Nambisan RN, Karakousis CP. Pseudo-tumor of the calf. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1993;19(3):300-301.

11. Mann HA, Hilton A, Goddard NJ, Smith MA, Holloway B, Lee CA. Synovial sarcoma mimicking haemophilic pseudotumour. Sarcoma. 2006;2006:27212.

12. Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD. Radiologic evaluation of soft-tissue masses: a current perspective. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(3):575-587.

13. Vanel D, Verstraete KL, Shapeero LG. Primary tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Radiol Clin North Am. 1997;35(1):213-237.

14. Siegel MJ. Magnetic resonance imaging of musculoskeletal soft tissue masses. Radiol Clin North Am. 2001;39(4):701-720.

15. O’Connor EE, Dixon LB, Peabody T, Stacy GS. MRI of cystic and soft-tissue masses of the shoulder joint. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(1):39-47.

16. Bermejo A, De Bustamante TD, Martinez A, Carrera R, Zabia E, Manjon P. MR imaging in the evaluation of cystic-appearing soft-tissue masses of the extremities. Radiographics. 2013;33(3):833-855.

17. Morrison C, Wakely PE Jr, Ashman CJ, Lemley D, Theil K. Cystic synovial sarcoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2001;5(1):48-56.

18. Eilber FC, Rosen G, Nelson SD, et al. High-grade extremity soft tissue sarcomas: factors predictive of local recurrence and its effect on morbidity and mortality. Ann Surg. 2003;237(2):218-226.

19. Kuo CH. Peripheral neuropathy and lower limb swelling caused by a giant popliteal fossa hematoma. Neurol Sci. 2012;33(2):475-476.

20. Reijnen MM, de Rhoter W, Zeebregts CJ. Treatment of a symptomatic popliteal pseudoaneurysm using a stent-graft and ultrasound-guided evacuation of the haematoma. Emerg Radiol. 2009;16(2):167-169.

21. Rossi FH, Veith FJ, Lipsitz EC, Izukawa NM, Oliveira LA, Silva DG. Giant femoropopliteal artery aneurysm and vein rupture. Vascular. 2004;12(4):263-265.

22. Lamoca LM, Alerany MB, Hernando LL. Endovascular therapy for a ruptured popliteal aneurysm. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;75(3):427-429.

1. O’Sullivan B, Pisters PW. Staging and prognostic factor evaluation in soft tissue sarcoma. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003;12(2):333-353.

2. Rougraff B. The diagnosis and management of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities in the adult. Curr Probl Cancer. 1999;23(1):1-50.

3. Friedlander HL, Bump RG. Chronic expanding hematoma of the calf. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1968;50(6):1237-1241.

4. Liu CW, Kuo CL, Tsai TY, Lin LC, Wu CC. Massive gluteal mass mimicking sarcoma: chronic expanding hematoma. Formosan J Musculoskeletal Disord. 2011;2(3):106-108.

5. Taieb S, Penel N, Vanseymortier L, Ceugnart L. Soft tissue sarcomas or intramuscular haematomas? Eur J Radiol. 2009;72(1):44-49.

6. Reid JD, Kommareddi S, Lankerani M, Park MC. Chronic expanding hematomas. A clinicopathologic entity. JAMA. 1980;244(21):2441-2442.

7. Okada K, Sugiyama T, Kato H, Tani T. Chronic expanding hematoma mimicking soft tissue neoplasm. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2971-2972.

8. Negoro K, Uchida K, Yayama T, Kokubo Y, Baba H. Chronic expanding hematoma of the thigh. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(2):192-194.

9. Goddard MS, Vakil JJ, McCarthy EF, Khanuja HS. Chronic expanding hematoma of the lateral thigh and massive bony destruction after a failed total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(2):338.e13-.e15.

10. Radford DM, Schuh ME, Nambisan RN, Karakousis CP. Pseudo-tumor of the calf. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1993;19(3):300-301.

11. Mann HA, Hilton A, Goddard NJ, Smith MA, Holloway B, Lee CA. Synovial sarcoma mimicking haemophilic pseudotumour. Sarcoma. 2006;2006:27212.

12. Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD. Radiologic evaluation of soft-tissue masses: a current perspective. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(3):575-587.

13. Vanel D, Verstraete KL, Shapeero LG. Primary tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Radiol Clin North Am. 1997;35(1):213-237.

14. Siegel MJ. Magnetic resonance imaging of musculoskeletal soft tissue masses. Radiol Clin North Am. 2001;39(4):701-720.

15. O’Connor EE, Dixon LB, Peabody T, Stacy GS. MRI of cystic and soft-tissue masses of the shoulder joint. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(1):39-47.

16. Bermejo A, De Bustamante TD, Martinez A, Carrera R, Zabia E, Manjon P. MR imaging in the evaluation of cystic-appearing soft-tissue masses of the extremities. Radiographics. 2013;33(3):833-855.

17. Morrison C, Wakely PE Jr, Ashman CJ, Lemley D, Theil K. Cystic synovial sarcoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2001;5(1):48-56.

18. Eilber FC, Rosen G, Nelson SD, et al. High-grade extremity soft tissue sarcomas: factors predictive of local recurrence and its effect on morbidity and mortality. Ann Surg. 2003;237(2):218-226.

19. Kuo CH. Peripheral neuropathy and lower limb swelling caused by a giant popliteal fossa hematoma. Neurol Sci. 2012;33(2):475-476.

20. Reijnen MM, de Rhoter W, Zeebregts CJ. Treatment of a symptomatic popliteal pseudoaneurysm using a stent-graft and ultrasound-guided evacuation of the haematoma. Emerg Radiol. 2009;16(2):167-169.

21. Rossi FH, Veith FJ, Lipsitz EC, Izukawa NM, Oliveira LA, Silva DG. Giant femoropopliteal artery aneurysm and vein rupture. Vascular. 2004;12(4):263-265.

22. Lamoca LM, Alerany MB, Hernando LL. Endovascular therapy for a ruptured popliteal aneurysm. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;75(3):427-429.

Office-Based Rapid Prototyping in Orthopedic Surgery: A Novel Planning Technique and Review of the Literature

Three-dimensional (3-D) printing is a rapidly evolving technology with both medical and nonmedical applications.1,2 Rapid prototyping involves creating a physical model of human tissue from a 3-D computer-generated rendering.3 The method relies on export of Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM)–based computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data into standard triangular language (STL) format. Reducing CT or MRI slice thickness increases resolution of the final model.2 Five types of rapid prototyping exist: STL, selective laser sintering, fused deposition modeling, multijet modeling, and 3-D printing.

Most implant manufacturers can produce a 3-D model based on surgeon-provided DICOM images. The ability to produce anatomical models in an office-based setting is a more recent development. Three-dimensional modeling may allow for more accurate and extensive preoperative planning than radiographic examination alone does, and may even allow surgeons to perform procedures as part of preoperative preparation. This can allow for early recognition of unanticipated intraoperative problems or of the need for special techniques and implants that would not have been otherwise available, all of which may ultimately reduce operative time.

The breadth of applications for office-based 3-D prototyping is not well described in the orthopedic surgery literature. In this article, we describe 7 cases of complex orthopedic disorders that were surgically treated after preoperative planning in which use of a 3-D printer allowed for “mock” surgery before the actual procedures. In 3 of the cases, the models were made by the implant manufacturers. Working with these models prompted us to buy a 3-D printer (Fortus 250; Stratasys, Eden Prairie, Minnesota) for in-office use. In the other 4 cases, we used this printer to create our own models. As indicated in the manufacturer’s literature, the printer uses fused deposition modeling, which builds a model layer by layer by heating thermoplastic material to a semi-liquid state and extruding it according to computer-controlled pathways.

We present preoperative images, preoperative 3-D modeling, and intraoperative and postoperative images along with brief case descriptions (Table). The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Case 1

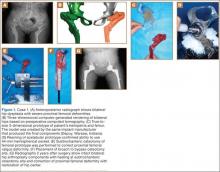

A 28-year-old woman with a history of spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia presented to our clinic with bilateral hip pain. About 8 years earlier, she had undergone bilateral proximal and distal femoral osteotomies. Her function had initially improved, but over the 2 to 3 years before presentation she began having more pain and stiffness with activity. At time of initial evaluation, she was able to walk only 1 to 2 blocks and had difficulty getting in and out of a car and up out of a seated position.

On physical examination, the patient was 3 feet 10 inches tall and weighed 77 pounds. She ambulated with decreased stance phase on both lower extremities and had developed a significant amount of increased forward pelvic inclination and increased lumbar lordosis. Both hips and thighs had multiple healed scars from prior surgeries and pin tracts. Range of motion (ROM) on both sides was restricted to 85° of flexion, 10° of internal rotation, 15° of external rotation, and 15° of abduction.

Plain radiographs showed advanced degenerative joint disease (DJD) of both hips with dysplastic acetabuli and evidence of healed osteotomies (Figure 1). Femoral deformities, noted bilaterally, consisted of marked valgus proximally and varus distally. Preoperative CT was used to create a 3-D model of the pelvis and femur. The model was created by the same implant manufacturer that produced the final components (Depuy, Warsaw, Indiana). Corrective femoral osteotomy was performed on the model to allow for design and use of a custom implant, while the modeled pelvis confirmed the ability to reproduce the normal hip center with a 44-mm conventional hemispherical socket.

After surgery, the patient was able to ambulate without a limp and return to work. Her hip ROM was pain-free passively and actively with flexion to 100°, internal rotation to 35°, external rotation to 20°, and abduction to 30°.

Case 2

A 48-year-old woman with a history of Crowe IV hip dysplasia presented to our clinic with a chronically dislocated right total hip arthroplasty (THA) (Figure 2). Her initial THA was revised 1 year later because of acetabular component failure. Two years later, she was diagnosed with a deep periprosthetic infection, which was ultimately treated with 2-stage reimplantation. She subsequently dislocated and underwent re-revision of the S-ROM body and stem (DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, Indiana). At a visit after that revision, she was noted to be chronically dislocated, and was sent to our clinic for further management.

Preoperative radiographs showed a right uncemented THA with the femoral head dislocated toward the false acetabulum, retained hardware, and an old ununited trochanteric fragment. Both the femoral and acetabular components appeared well-fixed, though the acetabular component was positioned inferior, toward the obturator foramen.

Preoperative CT with metal artifact subtraction was used to create a 3-D model of the residual bony pelvis. The model was made by an implant manufacturer (Zimmer, Warsaw, Indiana). The shape of the superior defect was amenable to reconstruction using a modified revision trabecular metal socket. The pelvic model was reamed to accept a conventional hemispherical socket. The defect was reamed to accept a modified revision trabecular metal socket. The real implant was fashioned before surgery and was sterilized to avoid the need for intraoperative modification. Use of the preoperative model significantly reduced the time that would have been needed to modify the implant during actual surgery.