User login

Treatment of Proximal Humerus Fractures: Comparison of Shoulder and Trauma Surgeons

Proximal humerus fractures (PHFs), AO/OTA (Ar beitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen/Orthopaedic Trauma Association) type 11,1 are common, representing 4% to 5% of all fractures in adults.2 However, there is no consensus as to optimal management of these injuries, with some reports supporting and others rejecting the various fixation methods,3 and there are no evidence-based practice guidelines informing treatment decisions.4 Not surprisingly, orthopedic surgeons do not agree on ideal treatment for PHFs5,6 and differ by region in their rates of surgical management.2 In addition, analyses of national databases have found variation in choice of surgical treatment for PHFs between surgeons and between hospitals of different patient volumes.4 Few studies have assessed surgeon agreement on treatment decisions. Findings from these limited investigations indicate there is little agreement on treatment choices, but training may have some impact.5-7 In 3 studies,5-7 shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons differed in their management of PHFs both in terms of rates of operative treatment5,7 and specific operative management choices.5,6 No study has assessed surgeon agreement on radiographic outcomes.

We conducted a study to compare expert shoulder and trauma surgeons’ treatment decision-making and agreement on final radiographic outcomes of surgically treated PHFs. We hypothesized there would be poor agreement on treatment decisions and better agreement on radiographic outcomes, with a difference between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons.

Materials and Methods

After receiving institutional review board approval for this study, we collected data on 100 consecutive PHFs (AO/OTA type 111) surgically treated at 2 affiliated level I trauma centers between January 2004 and July 2008. None of the cases in the series was managed by any of the surgeons participating in this study.

We created a PowerPoint (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) survey that included radiographs (preoperative, immediate postoperative, final postoperative) and, if available, a computed tomography image. This survey was sent to 4 orthopedic surgeons: Drs. Gardner, Gerber, Lorich, and Walch. Two of these authors are fellowship-trained in shoulder surgery, the other 2 in orthopedic traumatology with specialization in treating PHFs. All are internationally renowned in PHF management. Using the survey images and a 4-point Likert scale ranging from disagree strongly to agree strongly, the examiners rated their agreement with treatment decisions (arthroplasty vs fixation). They also rated (very poor to very good) immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement, immediate postoperative fixation methods for fractures treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), and final radiographic outcomes.

Interobserver agreement was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC),8,9 with scores of <0.2 (poor), 0.21 to 0.4 (fair), 0.41 to 0.6 (moderate), 0.61 to 0.8 (good), and >0.8 (excellent) used to indicate agreement among observers. ICC scores were determined by treating the 4 examiners as independent entities. Subgroup analyses were also performed to determine ICC scores comparing the 2 shoulder surgeons, comparing the 2 trauma surgeons, and comparing the shoulder surgeons and trauma surgeons as 2 separate groups. ICC scores were used instead of κ coefficients to assess agreement because ICC scores treat ratings as continuous variables, allow for comparison of 2 or more raters, and allow for assessment of correlation among raters, whereas κ coefficients treat data as categorical variables and assume the ratings have no natural ordering. ICC scores were generated by SAS 9.1.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

The 4 surgeons’ overall ICC scores for agreement with the rating of immediate reduction or arthroplasty placement and the rating of final radiographic outcome indicated moderate levels of agreement (Table 1). Regarding treatment decision-making and ratings of fixation, the surgeons demonstrated poor and fair levels of agreement, respectively.

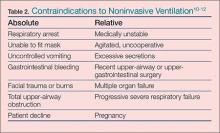

The ICC scores comparing the shoulder and trauma surgeons revealed similar levels of agreement (Table 2): moderate levels of agreement for ratings of both immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement and final radiographic outcomes, but poor and fair levels of agreement regarding treatment decision-making and the rating of immediate postoperative fixation methods for fractures treated with ORIF, respectively.

Subgroup analysis revealed that the 2 shoulder surgeons had poor and fair levels of agreement for treatment decisions and rating of immediate postoperative fixation, respectively, though they moderately agreed on rating of immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement and rating of final radiographic outcome (Table 3). When the 2 trauma surgeons were compared with each other, ICC scores revealed higher levels of agreement overall (Table 4). In other words, the 2 trauma surgeons agreed with each other more than the 2 shoulder surgeons agreed with each other.

Discussion

This study had 3 major findings: (1) Surgeons do not agree on treatment decisions, including fixation methods, regarding PHFs; (2) regardless of their opinions on ideal treatment, they moderately agree on reductions and final radiographic outcomes; (3) expert trauma surgeons may agree more on treatment decisions than expert shoulder surgeons do. In other words, surgeons do not agree on the best treatment, but they radiographically recognize when a procedure has been performed technically well or poorly. These results support our hypothesis and the limited current literature.

An analysis of Medicare databases showed marked regional variation in rates of operative treatment of PHFs.2 Similarly, a Nationwide Inpatient Sample analysis revealed nationwide variation in operative management of PHFs.4 Both findings are consistent with our results of poor agreement about treatment decisions and ratings of postoperative fixation of PHFs. In 2010, Petit and colleagues6 reported that surgeons do not agree on PHF management. In 2011, Foroohar and colleagues10 similarly reported low interobserver agreement for treatment recommendations made by 4 upper extremity orthopedic specialists, 4 general orthopedic surgeons, 4 senior residents, and 4 junior residents, for a series of 16 PHFs—also consistent with our findings.

The lack of agreement about PHF treatment may reflect a difference in training, particularly in light of the recent expansion of shoulder and elbow fellowships.2 Three separate studies performed at 2 affiliated level I trauma centers demonstrated significant differences in treatment decision-making between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons.5-7 Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that training affects treatment decision-making, as we found poor agreement between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons regarding treatment decision for PHFs. Subanalyses revealed that expert trauma surgeons agreed with each other on treatment decisions more than expert shoulder surgeons agreed with each other, further suggesting that training may affect how surgeons manage PHFs. Differences in fellowship training even within the same specialty may account for the observed lesser levels of agreement between the shoulder surgeons, even among experts in the field.

The evidence for optimal treatment historically has been poor,4,6 with few high-quality prospective, randomized controlled studies on the topic up until the past few years. The most recent Cochrane Review on optimal PHF treatment concluded that there is insufficient evidence to make an evidence-based recommendation and that the long-term benefit of surgery is unclear.11 However, at least 5 controlled trials on the topic have been published within the past 5 years.12-16 The evidence is striking and generally supports nonoperative treatment for most PHFs, including some displaced fractures—contrary to general orthopedic practice in many parts of the United States,2 which hitherto had been based mainly on individual surgeon experience and the limited literature. Without strong evidence to support one treatment option over another, surgeons are left with no objective, scientific way of coming to agreement.

Related to the poor status quo of evidence for PHF treatments is new technology (eg, locking plates, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty) that has expanded surgical indications.2,17 Although such developments have the potential to improve surgical treatments, they may also exacerbate the disagreement between surgeons regarding optimal operative treatment of PHFs. This potential consequence of new technology may be reflected in our finding of disagreement among surgeons on immediate postoperative fixation methods. Precisely because they are new, such technological innovations have limited evidence supporting their use. This leaves surgeons with little to nothing to inform their decisions to use these devices, other than familiarity with and impressions of the new technology.

Our study had several limitations. First is the small sample size, of surgeons who are leaders in the field. Our sample therefore may not be generalizable to the general population of shoulder and trauma surgeons. Second, we did not calculate intraobserver variability. Third, inherent to studies of interobserver agreement is the uncertainty of their clinical relevance. In the clinical setting, a surgeon has much more information at hand (eg, patient history, physical examination findings, colleague consultations), thus raising the possibility of underestimations of interobserver agreements.18 Fourth, our comparison of surgeons’ ratings of outcomes was purely radiographic, which may or may not represent or be indicative of clinical outcomes (eg, pain relief, function, range of motion, patient satisfaction). The conclusions we may draw are accordingly limited, as we did not directly evaluate clinical outcome parameters.

Our study had several strengths as well. First, to our knowledge this is the first study to assess interobserver variability in surgeons’ ratings of radiographic outcomes. Its findings may provide further insight into the reasons for poor agreement among orthopedic surgeons on both classification and treatment of PHFs. Second, our surveying of internationally renowned expert surgeons from 4 different institutions may have helped reduce single-institution bias, and it presents the highest level of expertise in the treatment of PHFs.

Although the surgeons in our study moderately agreed on final radiographic outcomes of PHFs, such levels of agreement may still be clinically unacceptable.19 The overall disagreement on treatment decisions highlights the need for better evidence for optimal treatment of PHFs in order to improve consensus, particularly with anticipated increases in age and comorbidities in the population in coming years.4 Subgroup analysis suggested trauma fellowships may contribute to better treatment agreement, though this idea requires further study, perhaps by surveying shoulder and trauma fellowship directors and their curricula for variability in teaching treatment decision-making. The surgeons in our study agreed more on what they consider acceptable final radiographic outcomes, which is encouraging. However, treatment consensus is the primary goal. The recent publication of prospective, randomized studies is helping with this issue, but more studies are needed. It is encouraging that several are planned or under way.20-22

Conclusion

The surgeons surveyed in this study did not agree on ideal treatment for PHFs but moderately agreed on quality of radiographic outcomes. These differences may reflect a difference in training. We conducted this study to compare experienced shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons’ treatment decision-making and ratings of radiographic outcomes of PHFs when presented with the same group of patients managed at 2 level I trauma centers. We hypothesized there would be little agreement on treatment decisions, better agreement on final radiographic outcome, and a difference between decision-making and ratings of radiographic outcomes between expert shoulder and trauma surgeons. Our results showed that surgeons do not agree on the best treatment for PHFs but radiographically recognize when an operative treatment has been performed well or poorly. Regarding treatment decisions, our results also showed that expert trauma surgeons may agree more with each other than shoulder surgeons agree with each other. These results support our hypothesis and the limited current literature. The overall disagreement among the surgeons in our study and an aging population that grows sicker each year highlight the need for better evidence for the optimal treatment of PHFs in order to improve consensus.

1. Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium – 2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10 suppl):S1-S133.

2. Bell JE, Leung BC, Spratt KF, et al. Trends and variation in incidence, surgical treatment, and repeat surgery of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(2):121-131.

3. McLaurin TM. Proximal humerus fractures in the elderly are we operating on too many? Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2004;62(1-2):24-32.

4. Jain NB, Kuye I, Higgins LD, Warner JJP. Surgeon volume is associated with cost and variation in surgical treatment of proximal humeral fractures. Clin Orthop. 2012;471(2):655-664.

5. Boykin RE, Jawa A, O’Brien T, Higgins LD, Warner JJP. Variability in operative management of proximal humerus fractures. Shoulder Elbow. 2011;3(4):197-201.

6. Petit CJ, Millett PJ, Endres NK, Diller D, Harris MB, Warner JJP. Management of proximal humeral fractures: surgeons don’t agree. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(3):446-451.

7. Okike K, Lee OC, Makanji H, Harris MB, Vrahas MS. Factors associated with the decision for operative versus non-operative treatment of displaced proximal humerus fractures in the elderly. Injury. 2013;44(4):448-455.

8. Kodali P, Jones MH, Polster J, Miniaci A, Fening SD. Accuracy of measurement of Hill-Sachs lesions with computed tomography. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(8):1328-1334.

9. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(2):420-428.

10. Foroohar A, Tosti R, Richmond JM, Gaughan JP, Ilyas AM. Classification and treatment of proximal humerus fractures: inter-observer reliability and agreement across imaging modalities and experience. J Orthop Surg Res. 2011;6:38.

11. Handoll HH, Ollivere BJ. Interventions for treating proximal humeral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(12):CD000434.

12. Boons HW, Goosen JH, van Grinsven S, van Susante JL, van Loon CJ. Hemiarthroplasty for humeral four-part fractures for patients 65 years and older: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Orthop. 2012;470(12):3483-3491.

13. Fjalestad T, Hole MØ, Hovden IAH, Blücher J, Strømsøe K. Surgical treatment with an angular stable plate for complex displaced proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(2):98-106.

14. Fjalestad T, Hole MØ, Jørgensen JJ, Strømsøe K, Kristiansen IS. Health and cost consequences of surgical versus conservative treatment for a comminuted proximal humeral fracture in elderly patients. Injury. 2010;41(6):599-605.

15. Olerud P, Ahrengart L, Ponzer S, Saving J, Tidermark J. Internal fixation versus nonoperative treatment of displaced 3-part proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(5):747-755.

16. Olerud P, Ahrengart L, Ponzer S, Saving J, Tidermark J. Hemiarthroplasty versus nonoperative treatment of displaced 4-part proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(7):1025-1033.

17. Agudelo J, Schürmann M, Stahel P, et al. Analysis of efficacy and failure in proximal humerus fractures treated with locking plates. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10):676-681.

18. Brorson S, Hróbjartsson A. Training improves agreement among doctors using the Neer system for proximal humeral fractures in a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(1):7-16.

19. Brorson S, Olsen BS, Frich LH, et al. Surgeons agree more on treatment recommendations than on classification of proximal humeral fractures. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:114.

20. Handoll H, Brealey S, Rangan A, et al. Protocol for the ProFHER (PROximal Fracture of the Humerus: Evaluation by Randomisation) trial: a pragmatic multi-centre randomised controlled trial of surgical versus non-surgical treatment for proximal fracture of the humerus in adults. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:140.

21. Den Hartog D, Van Lieshout EMM, Tuinebreijer WE, et al. Primary hemiarthroplasty versus conservative treatment for comminuted fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly (ProCon): a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:97.

22. Verbeek PA, van den Akker-Scheek I, Wendt KW, Diercks RL. Hemiarthroplasty versus angle-stable locking compression plate osteosynthesis in the treatment of three- and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly: design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:16.

Proximal humerus fractures (PHFs), AO/OTA (Ar beitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen/Orthopaedic Trauma Association) type 11,1 are common, representing 4% to 5% of all fractures in adults.2 However, there is no consensus as to optimal management of these injuries, with some reports supporting and others rejecting the various fixation methods,3 and there are no evidence-based practice guidelines informing treatment decisions.4 Not surprisingly, orthopedic surgeons do not agree on ideal treatment for PHFs5,6 and differ by region in their rates of surgical management.2 In addition, analyses of national databases have found variation in choice of surgical treatment for PHFs between surgeons and between hospitals of different patient volumes.4 Few studies have assessed surgeon agreement on treatment decisions. Findings from these limited investigations indicate there is little agreement on treatment choices, but training may have some impact.5-7 In 3 studies,5-7 shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons differed in their management of PHFs both in terms of rates of operative treatment5,7 and specific operative management choices.5,6 No study has assessed surgeon agreement on radiographic outcomes.

We conducted a study to compare expert shoulder and trauma surgeons’ treatment decision-making and agreement on final radiographic outcomes of surgically treated PHFs. We hypothesized there would be poor agreement on treatment decisions and better agreement on radiographic outcomes, with a difference between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons.

Materials and Methods

After receiving institutional review board approval for this study, we collected data on 100 consecutive PHFs (AO/OTA type 111) surgically treated at 2 affiliated level I trauma centers between January 2004 and July 2008. None of the cases in the series was managed by any of the surgeons participating in this study.

We created a PowerPoint (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) survey that included radiographs (preoperative, immediate postoperative, final postoperative) and, if available, a computed tomography image. This survey was sent to 4 orthopedic surgeons: Drs. Gardner, Gerber, Lorich, and Walch. Two of these authors are fellowship-trained in shoulder surgery, the other 2 in orthopedic traumatology with specialization in treating PHFs. All are internationally renowned in PHF management. Using the survey images and a 4-point Likert scale ranging from disagree strongly to agree strongly, the examiners rated their agreement with treatment decisions (arthroplasty vs fixation). They also rated (very poor to very good) immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement, immediate postoperative fixation methods for fractures treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), and final radiographic outcomes.

Interobserver agreement was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC),8,9 with scores of <0.2 (poor), 0.21 to 0.4 (fair), 0.41 to 0.6 (moderate), 0.61 to 0.8 (good), and >0.8 (excellent) used to indicate agreement among observers. ICC scores were determined by treating the 4 examiners as independent entities. Subgroup analyses were also performed to determine ICC scores comparing the 2 shoulder surgeons, comparing the 2 trauma surgeons, and comparing the shoulder surgeons and trauma surgeons as 2 separate groups. ICC scores were used instead of κ coefficients to assess agreement because ICC scores treat ratings as continuous variables, allow for comparison of 2 or more raters, and allow for assessment of correlation among raters, whereas κ coefficients treat data as categorical variables and assume the ratings have no natural ordering. ICC scores were generated by SAS 9.1.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

The 4 surgeons’ overall ICC scores for agreement with the rating of immediate reduction or arthroplasty placement and the rating of final radiographic outcome indicated moderate levels of agreement (Table 1). Regarding treatment decision-making and ratings of fixation, the surgeons demonstrated poor and fair levels of agreement, respectively.

The ICC scores comparing the shoulder and trauma surgeons revealed similar levels of agreement (Table 2): moderate levels of agreement for ratings of both immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement and final radiographic outcomes, but poor and fair levels of agreement regarding treatment decision-making and the rating of immediate postoperative fixation methods for fractures treated with ORIF, respectively.

Subgroup analysis revealed that the 2 shoulder surgeons had poor and fair levels of agreement for treatment decisions and rating of immediate postoperative fixation, respectively, though they moderately agreed on rating of immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement and rating of final radiographic outcome (Table 3). When the 2 trauma surgeons were compared with each other, ICC scores revealed higher levels of agreement overall (Table 4). In other words, the 2 trauma surgeons agreed with each other more than the 2 shoulder surgeons agreed with each other.

Discussion

This study had 3 major findings: (1) Surgeons do not agree on treatment decisions, including fixation methods, regarding PHFs; (2) regardless of their opinions on ideal treatment, they moderately agree on reductions and final radiographic outcomes; (3) expert trauma surgeons may agree more on treatment decisions than expert shoulder surgeons do. In other words, surgeons do not agree on the best treatment, but they radiographically recognize when a procedure has been performed technically well or poorly. These results support our hypothesis and the limited current literature.

An analysis of Medicare databases showed marked regional variation in rates of operative treatment of PHFs.2 Similarly, a Nationwide Inpatient Sample analysis revealed nationwide variation in operative management of PHFs.4 Both findings are consistent with our results of poor agreement about treatment decisions and ratings of postoperative fixation of PHFs. In 2010, Petit and colleagues6 reported that surgeons do not agree on PHF management. In 2011, Foroohar and colleagues10 similarly reported low interobserver agreement for treatment recommendations made by 4 upper extremity orthopedic specialists, 4 general orthopedic surgeons, 4 senior residents, and 4 junior residents, for a series of 16 PHFs—also consistent with our findings.

The lack of agreement about PHF treatment may reflect a difference in training, particularly in light of the recent expansion of shoulder and elbow fellowships.2 Three separate studies performed at 2 affiliated level I trauma centers demonstrated significant differences in treatment decision-making between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons.5-7 Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that training affects treatment decision-making, as we found poor agreement between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons regarding treatment decision for PHFs. Subanalyses revealed that expert trauma surgeons agreed with each other on treatment decisions more than expert shoulder surgeons agreed with each other, further suggesting that training may affect how surgeons manage PHFs. Differences in fellowship training even within the same specialty may account for the observed lesser levels of agreement between the shoulder surgeons, even among experts in the field.

The evidence for optimal treatment historically has been poor,4,6 with few high-quality prospective, randomized controlled studies on the topic up until the past few years. The most recent Cochrane Review on optimal PHF treatment concluded that there is insufficient evidence to make an evidence-based recommendation and that the long-term benefit of surgery is unclear.11 However, at least 5 controlled trials on the topic have been published within the past 5 years.12-16 The evidence is striking and generally supports nonoperative treatment for most PHFs, including some displaced fractures—contrary to general orthopedic practice in many parts of the United States,2 which hitherto had been based mainly on individual surgeon experience and the limited literature. Without strong evidence to support one treatment option over another, surgeons are left with no objective, scientific way of coming to agreement.

Related to the poor status quo of evidence for PHF treatments is new technology (eg, locking plates, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty) that has expanded surgical indications.2,17 Although such developments have the potential to improve surgical treatments, they may also exacerbate the disagreement between surgeons regarding optimal operative treatment of PHFs. This potential consequence of new technology may be reflected in our finding of disagreement among surgeons on immediate postoperative fixation methods. Precisely because they are new, such technological innovations have limited evidence supporting their use. This leaves surgeons with little to nothing to inform their decisions to use these devices, other than familiarity with and impressions of the new technology.

Our study had several limitations. First is the small sample size, of surgeons who are leaders in the field. Our sample therefore may not be generalizable to the general population of shoulder and trauma surgeons. Second, we did not calculate intraobserver variability. Third, inherent to studies of interobserver agreement is the uncertainty of their clinical relevance. In the clinical setting, a surgeon has much more information at hand (eg, patient history, physical examination findings, colleague consultations), thus raising the possibility of underestimations of interobserver agreements.18 Fourth, our comparison of surgeons’ ratings of outcomes was purely radiographic, which may or may not represent or be indicative of clinical outcomes (eg, pain relief, function, range of motion, patient satisfaction). The conclusions we may draw are accordingly limited, as we did not directly evaluate clinical outcome parameters.

Our study had several strengths as well. First, to our knowledge this is the first study to assess interobserver variability in surgeons’ ratings of radiographic outcomes. Its findings may provide further insight into the reasons for poor agreement among orthopedic surgeons on both classification and treatment of PHFs. Second, our surveying of internationally renowned expert surgeons from 4 different institutions may have helped reduce single-institution bias, and it presents the highest level of expertise in the treatment of PHFs.

Although the surgeons in our study moderately agreed on final radiographic outcomes of PHFs, such levels of agreement may still be clinically unacceptable.19 The overall disagreement on treatment decisions highlights the need for better evidence for optimal treatment of PHFs in order to improve consensus, particularly with anticipated increases in age and comorbidities in the population in coming years.4 Subgroup analysis suggested trauma fellowships may contribute to better treatment agreement, though this idea requires further study, perhaps by surveying shoulder and trauma fellowship directors and their curricula for variability in teaching treatment decision-making. The surgeons in our study agreed more on what they consider acceptable final radiographic outcomes, which is encouraging. However, treatment consensus is the primary goal. The recent publication of prospective, randomized studies is helping with this issue, but more studies are needed. It is encouraging that several are planned or under way.20-22

Conclusion

The surgeons surveyed in this study did not agree on ideal treatment for PHFs but moderately agreed on quality of radiographic outcomes. These differences may reflect a difference in training. We conducted this study to compare experienced shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons’ treatment decision-making and ratings of radiographic outcomes of PHFs when presented with the same group of patients managed at 2 level I trauma centers. We hypothesized there would be little agreement on treatment decisions, better agreement on final radiographic outcome, and a difference between decision-making and ratings of radiographic outcomes between expert shoulder and trauma surgeons. Our results showed that surgeons do not agree on the best treatment for PHFs but radiographically recognize when an operative treatment has been performed well or poorly. Regarding treatment decisions, our results also showed that expert trauma surgeons may agree more with each other than shoulder surgeons agree with each other. These results support our hypothesis and the limited current literature. The overall disagreement among the surgeons in our study and an aging population that grows sicker each year highlight the need for better evidence for the optimal treatment of PHFs in order to improve consensus.

Proximal humerus fractures (PHFs), AO/OTA (Ar beitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen/Orthopaedic Trauma Association) type 11,1 are common, representing 4% to 5% of all fractures in adults.2 However, there is no consensus as to optimal management of these injuries, with some reports supporting and others rejecting the various fixation methods,3 and there are no evidence-based practice guidelines informing treatment decisions.4 Not surprisingly, orthopedic surgeons do not agree on ideal treatment for PHFs5,6 and differ by region in their rates of surgical management.2 In addition, analyses of national databases have found variation in choice of surgical treatment for PHFs between surgeons and between hospitals of different patient volumes.4 Few studies have assessed surgeon agreement on treatment decisions. Findings from these limited investigations indicate there is little agreement on treatment choices, but training may have some impact.5-7 In 3 studies,5-7 shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons differed in their management of PHFs both in terms of rates of operative treatment5,7 and specific operative management choices.5,6 No study has assessed surgeon agreement on radiographic outcomes.

We conducted a study to compare expert shoulder and trauma surgeons’ treatment decision-making and agreement on final radiographic outcomes of surgically treated PHFs. We hypothesized there would be poor agreement on treatment decisions and better agreement on radiographic outcomes, with a difference between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons.

Materials and Methods

After receiving institutional review board approval for this study, we collected data on 100 consecutive PHFs (AO/OTA type 111) surgically treated at 2 affiliated level I trauma centers between January 2004 and July 2008. None of the cases in the series was managed by any of the surgeons participating in this study.

We created a PowerPoint (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) survey that included radiographs (preoperative, immediate postoperative, final postoperative) and, if available, a computed tomography image. This survey was sent to 4 orthopedic surgeons: Drs. Gardner, Gerber, Lorich, and Walch. Two of these authors are fellowship-trained in shoulder surgery, the other 2 in orthopedic traumatology with specialization in treating PHFs. All are internationally renowned in PHF management. Using the survey images and a 4-point Likert scale ranging from disagree strongly to agree strongly, the examiners rated their agreement with treatment decisions (arthroplasty vs fixation). They also rated (very poor to very good) immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement, immediate postoperative fixation methods for fractures treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), and final radiographic outcomes.

Interobserver agreement was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC),8,9 with scores of <0.2 (poor), 0.21 to 0.4 (fair), 0.41 to 0.6 (moderate), 0.61 to 0.8 (good), and >0.8 (excellent) used to indicate agreement among observers. ICC scores were determined by treating the 4 examiners as independent entities. Subgroup analyses were also performed to determine ICC scores comparing the 2 shoulder surgeons, comparing the 2 trauma surgeons, and comparing the shoulder surgeons and trauma surgeons as 2 separate groups. ICC scores were used instead of κ coefficients to assess agreement because ICC scores treat ratings as continuous variables, allow for comparison of 2 or more raters, and allow for assessment of correlation among raters, whereas κ coefficients treat data as categorical variables and assume the ratings have no natural ordering. ICC scores were generated by SAS 9.1.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

The 4 surgeons’ overall ICC scores for agreement with the rating of immediate reduction or arthroplasty placement and the rating of final radiographic outcome indicated moderate levels of agreement (Table 1). Regarding treatment decision-making and ratings of fixation, the surgeons demonstrated poor and fair levels of agreement, respectively.

The ICC scores comparing the shoulder and trauma surgeons revealed similar levels of agreement (Table 2): moderate levels of agreement for ratings of both immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement and final radiographic outcomes, but poor and fair levels of agreement regarding treatment decision-making and the rating of immediate postoperative fixation methods for fractures treated with ORIF, respectively.

Subgroup analysis revealed that the 2 shoulder surgeons had poor and fair levels of agreement for treatment decisions and rating of immediate postoperative fixation, respectively, though they moderately agreed on rating of immediate postoperative reduction or arthroplasty placement and rating of final radiographic outcome (Table 3). When the 2 trauma surgeons were compared with each other, ICC scores revealed higher levels of agreement overall (Table 4). In other words, the 2 trauma surgeons agreed with each other more than the 2 shoulder surgeons agreed with each other.

Discussion

This study had 3 major findings: (1) Surgeons do not agree on treatment decisions, including fixation methods, regarding PHFs; (2) regardless of their opinions on ideal treatment, they moderately agree on reductions and final radiographic outcomes; (3) expert trauma surgeons may agree more on treatment decisions than expert shoulder surgeons do. In other words, surgeons do not agree on the best treatment, but they radiographically recognize when a procedure has been performed technically well or poorly. These results support our hypothesis and the limited current literature.

An analysis of Medicare databases showed marked regional variation in rates of operative treatment of PHFs.2 Similarly, a Nationwide Inpatient Sample analysis revealed nationwide variation in operative management of PHFs.4 Both findings are consistent with our results of poor agreement about treatment decisions and ratings of postoperative fixation of PHFs. In 2010, Petit and colleagues6 reported that surgeons do not agree on PHF management. In 2011, Foroohar and colleagues10 similarly reported low interobserver agreement for treatment recommendations made by 4 upper extremity orthopedic specialists, 4 general orthopedic surgeons, 4 senior residents, and 4 junior residents, for a series of 16 PHFs—also consistent with our findings.

The lack of agreement about PHF treatment may reflect a difference in training, particularly in light of the recent expansion of shoulder and elbow fellowships.2 Three separate studies performed at 2 affiliated level I trauma centers demonstrated significant differences in treatment decision-making between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons.5-7 Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that training affects treatment decision-making, as we found poor agreement between shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons regarding treatment decision for PHFs. Subanalyses revealed that expert trauma surgeons agreed with each other on treatment decisions more than expert shoulder surgeons agreed with each other, further suggesting that training may affect how surgeons manage PHFs. Differences in fellowship training even within the same specialty may account for the observed lesser levels of agreement between the shoulder surgeons, even among experts in the field.

The evidence for optimal treatment historically has been poor,4,6 with few high-quality prospective, randomized controlled studies on the topic up until the past few years. The most recent Cochrane Review on optimal PHF treatment concluded that there is insufficient evidence to make an evidence-based recommendation and that the long-term benefit of surgery is unclear.11 However, at least 5 controlled trials on the topic have been published within the past 5 years.12-16 The evidence is striking and generally supports nonoperative treatment for most PHFs, including some displaced fractures—contrary to general orthopedic practice in many parts of the United States,2 which hitherto had been based mainly on individual surgeon experience and the limited literature. Without strong evidence to support one treatment option over another, surgeons are left with no objective, scientific way of coming to agreement.

Related to the poor status quo of evidence for PHF treatments is new technology (eg, locking plates, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty) that has expanded surgical indications.2,17 Although such developments have the potential to improve surgical treatments, they may also exacerbate the disagreement between surgeons regarding optimal operative treatment of PHFs. This potential consequence of new technology may be reflected in our finding of disagreement among surgeons on immediate postoperative fixation methods. Precisely because they are new, such technological innovations have limited evidence supporting their use. This leaves surgeons with little to nothing to inform their decisions to use these devices, other than familiarity with and impressions of the new technology.

Our study had several limitations. First is the small sample size, of surgeons who are leaders in the field. Our sample therefore may not be generalizable to the general population of shoulder and trauma surgeons. Second, we did not calculate intraobserver variability. Third, inherent to studies of interobserver agreement is the uncertainty of their clinical relevance. In the clinical setting, a surgeon has much more information at hand (eg, patient history, physical examination findings, colleague consultations), thus raising the possibility of underestimations of interobserver agreements.18 Fourth, our comparison of surgeons’ ratings of outcomes was purely radiographic, which may or may not represent or be indicative of clinical outcomes (eg, pain relief, function, range of motion, patient satisfaction). The conclusions we may draw are accordingly limited, as we did not directly evaluate clinical outcome parameters.

Our study had several strengths as well. First, to our knowledge this is the first study to assess interobserver variability in surgeons’ ratings of radiographic outcomes. Its findings may provide further insight into the reasons for poor agreement among orthopedic surgeons on both classification and treatment of PHFs. Second, our surveying of internationally renowned expert surgeons from 4 different institutions may have helped reduce single-institution bias, and it presents the highest level of expertise in the treatment of PHFs.

Although the surgeons in our study moderately agreed on final radiographic outcomes of PHFs, such levels of agreement may still be clinically unacceptable.19 The overall disagreement on treatment decisions highlights the need for better evidence for optimal treatment of PHFs in order to improve consensus, particularly with anticipated increases in age and comorbidities in the population in coming years.4 Subgroup analysis suggested trauma fellowships may contribute to better treatment agreement, though this idea requires further study, perhaps by surveying shoulder and trauma fellowship directors and their curricula for variability in teaching treatment decision-making. The surgeons in our study agreed more on what they consider acceptable final radiographic outcomes, which is encouraging. However, treatment consensus is the primary goal. The recent publication of prospective, randomized studies is helping with this issue, but more studies are needed. It is encouraging that several are planned or under way.20-22

Conclusion

The surgeons surveyed in this study did not agree on ideal treatment for PHFs but moderately agreed on quality of radiographic outcomes. These differences may reflect a difference in training. We conducted this study to compare experienced shoulder and trauma fellowship–trained surgeons’ treatment decision-making and ratings of radiographic outcomes of PHFs when presented with the same group of patients managed at 2 level I trauma centers. We hypothesized there would be little agreement on treatment decisions, better agreement on final radiographic outcome, and a difference between decision-making and ratings of radiographic outcomes between expert shoulder and trauma surgeons. Our results showed that surgeons do not agree on the best treatment for PHFs but radiographically recognize when an operative treatment has been performed well or poorly. Regarding treatment decisions, our results also showed that expert trauma surgeons may agree more with each other than shoulder surgeons agree with each other. These results support our hypothesis and the limited current literature. The overall disagreement among the surgeons in our study and an aging population that grows sicker each year highlight the need for better evidence for the optimal treatment of PHFs in order to improve consensus.

1. Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium – 2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10 suppl):S1-S133.

2. Bell JE, Leung BC, Spratt KF, et al. Trends and variation in incidence, surgical treatment, and repeat surgery of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(2):121-131.

3. McLaurin TM. Proximal humerus fractures in the elderly are we operating on too many? Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2004;62(1-2):24-32.

4. Jain NB, Kuye I, Higgins LD, Warner JJP. Surgeon volume is associated with cost and variation in surgical treatment of proximal humeral fractures. Clin Orthop. 2012;471(2):655-664.

5. Boykin RE, Jawa A, O’Brien T, Higgins LD, Warner JJP. Variability in operative management of proximal humerus fractures. Shoulder Elbow. 2011;3(4):197-201.

6. Petit CJ, Millett PJ, Endres NK, Diller D, Harris MB, Warner JJP. Management of proximal humeral fractures: surgeons don’t agree. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(3):446-451.

7. Okike K, Lee OC, Makanji H, Harris MB, Vrahas MS. Factors associated with the decision for operative versus non-operative treatment of displaced proximal humerus fractures in the elderly. Injury. 2013;44(4):448-455.

8. Kodali P, Jones MH, Polster J, Miniaci A, Fening SD. Accuracy of measurement of Hill-Sachs lesions with computed tomography. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(8):1328-1334.

9. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(2):420-428.

10. Foroohar A, Tosti R, Richmond JM, Gaughan JP, Ilyas AM. Classification and treatment of proximal humerus fractures: inter-observer reliability and agreement across imaging modalities and experience. J Orthop Surg Res. 2011;6:38.

11. Handoll HH, Ollivere BJ. Interventions for treating proximal humeral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(12):CD000434.

12. Boons HW, Goosen JH, van Grinsven S, van Susante JL, van Loon CJ. Hemiarthroplasty for humeral four-part fractures for patients 65 years and older: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Orthop. 2012;470(12):3483-3491.

13. Fjalestad T, Hole MØ, Hovden IAH, Blücher J, Strømsøe K. Surgical treatment with an angular stable plate for complex displaced proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(2):98-106.

14. Fjalestad T, Hole MØ, Jørgensen JJ, Strømsøe K, Kristiansen IS. Health and cost consequences of surgical versus conservative treatment for a comminuted proximal humeral fracture in elderly patients. Injury. 2010;41(6):599-605.

15. Olerud P, Ahrengart L, Ponzer S, Saving J, Tidermark J. Internal fixation versus nonoperative treatment of displaced 3-part proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(5):747-755.

16. Olerud P, Ahrengart L, Ponzer S, Saving J, Tidermark J. Hemiarthroplasty versus nonoperative treatment of displaced 4-part proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(7):1025-1033.

17. Agudelo J, Schürmann M, Stahel P, et al. Analysis of efficacy and failure in proximal humerus fractures treated with locking plates. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10):676-681.

18. Brorson S, Hróbjartsson A. Training improves agreement among doctors using the Neer system for proximal humeral fractures in a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(1):7-16.

19. Brorson S, Olsen BS, Frich LH, et al. Surgeons agree more on treatment recommendations than on classification of proximal humeral fractures. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:114.

20. Handoll H, Brealey S, Rangan A, et al. Protocol for the ProFHER (PROximal Fracture of the Humerus: Evaluation by Randomisation) trial: a pragmatic multi-centre randomised controlled trial of surgical versus non-surgical treatment for proximal fracture of the humerus in adults. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:140.

21. Den Hartog D, Van Lieshout EMM, Tuinebreijer WE, et al. Primary hemiarthroplasty versus conservative treatment for comminuted fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly (ProCon): a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:97.

22. Verbeek PA, van den Akker-Scheek I, Wendt KW, Diercks RL. Hemiarthroplasty versus angle-stable locking compression plate osteosynthesis in the treatment of three- and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly: design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:16.

1. Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium – 2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10 suppl):S1-S133.

2. Bell JE, Leung BC, Spratt KF, et al. Trends and variation in incidence, surgical treatment, and repeat surgery of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(2):121-131.

3. McLaurin TM. Proximal humerus fractures in the elderly are we operating on too many? Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2004;62(1-2):24-32.

4. Jain NB, Kuye I, Higgins LD, Warner JJP. Surgeon volume is associated with cost and variation in surgical treatment of proximal humeral fractures. Clin Orthop. 2012;471(2):655-664.

5. Boykin RE, Jawa A, O’Brien T, Higgins LD, Warner JJP. Variability in operative management of proximal humerus fractures. Shoulder Elbow. 2011;3(4):197-201.

6. Petit CJ, Millett PJ, Endres NK, Diller D, Harris MB, Warner JJP. Management of proximal humeral fractures: surgeons don’t agree. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(3):446-451.

7. Okike K, Lee OC, Makanji H, Harris MB, Vrahas MS. Factors associated with the decision for operative versus non-operative treatment of displaced proximal humerus fractures in the elderly. Injury. 2013;44(4):448-455.

8. Kodali P, Jones MH, Polster J, Miniaci A, Fening SD. Accuracy of measurement of Hill-Sachs lesions with computed tomography. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(8):1328-1334.

9. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(2):420-428.

10. Foroohar A, Tosti R, Richmond JM, Gaughan JP, Ilyas AM. Classification and treatment of proximal humerus fractures: inter-observer reliability and agreement across imaging modalities and experience. J Orthop Surg Res. 2011;6:38.

11. Handoll HH, Ollivere BJ. Interventions for treating proximal humeral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(12):CD000434.

12. Boons HW, Goosen JH, van Grinsven S, van Susante JL, van Loon CJ. Hemiarthroplasty for humeral four-part fractures for patients 65 years and older: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Orthop. 2012;470(12):3483-3491.

13. Fjalestad T, Hole MØ, Hovden IAH, Blücher J, Strømsøe K. Surgical treatment with an angular stable plate for complex displaced proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(2):98-106.

14. Fjalestad T, Hole MØ, Jørgensen JJ, Strømsøe K, Kristiansen IS. Health and cost consequences of surgical versus conservative treatment for a comminuted proximal humeral fracture in elderly patients. Injury. 2010;41(6):599-605.

15. Olerud P, Ahrengart L, Ponzer S, Saving J, Tidermark J. Internal fixation versus nonoperative treatment of displaced 3-part proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(5):747-755.

16. Olerud P, Ahrengart L, Ponzer S, Saving J, Tidermark J. Hemiarthroplasty versus nonoperative treatment of displaced 4-part proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(7):1025-1033.

17. Agudelo J, Schürmann M, Stahel P, et al. Analysis of efficacy and failure in proximal humerus fractures treated with locking plates. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10):676-681.

18. Brorson S, Hróbjartsson A. Training improves agreement among doctors using the Neer system for proximal humeral fractures in a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(1):7-16.

19. Brorson S, Olsen BS, Frich LH, et al. Surgeons agree more on treatment recommendations than on classification of proximal humeral fractures. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:114.

20. Handoll H, Brealey S, Rangan A, et al. Protocol for the ProFHER (PROximal Fracture of the Humerus: Evaluation by Randomisation) trial: a pragmatic multi-centre randomised controlled trial of surgical versus non-surgical treatment for proximal fracture of the humerus in adults. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:140.

21. Den Hartog D, Van Lieshout EMM, Tuinebreijer WE, et al. Primary hemiarthroplasty versus conservative treatment for comminuted fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly (ProCon): a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:97.

22. Verbeek PA, van den Akker-Scheek I, Wendt KW, Diercks RL. Hemiarthroplasty versus angle-stable locking compression plate osteosynthesis in the treatment of three- and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly: design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:16.

MRI shows ongoing inflammation despite clinical remission in early RA

Two years of either triple therapy or treatment with tumor necrosis factor plus methotrexate failed to eliminate joint inflammation on MRI in a subcohort of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis from the randomized, double-blind Treatment of Early Aggressive Rheumatoid Arthritis (TEAR) trial.

In 118 patients with a mean age of 51 years, short disease duration, and severe disease at TEAR trial entry – 92% of whom were seropositive – only 29 had wrist pain, tenderness, or swelling at 2-year follow-up. However, all 118 patients had MRI evidence of residual joint inflammation after 2 years, and 78% had evidence of osteitis, Dr. Veena K. Ranganath of the University of California, Los Angeles, and her colleagues reported (Arthritis Care Res. 2015 Jan. 7 [doi:10.1002/acr.22541]).

Inflammation remained despite significant improvement of disease activity measures at the time of the MRI, compared with baseline (for example, 28-joint disease activity score using erythrocyte sedimentation rate [DAS28-ESR] decreased from 5.8 to 2.9). Total MRI inflammation scores were significantly lower in patients who met 2011 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) Boolean remission criteria and remission by Chronic Disease Activity Index (CDAI), but not in those with DAS28-ESR remission, they noted.

The findings demonstrate that total MRI inflammatory scores are “best differentiated by the most stringent clinical remission criteria” – CDAI and 2011 ACR/EULAR Boolean Criteria, as opposed to DAS28-ESR (with a 2.6 cutpoint). Further, no differences were seen in damage or MRI inflammatory scores based on treatment regimen, which supports methotrexate-first recommendations for the TEAR trial, they said, noting that the long-term prognostic implications of the study findings are unclear because of short-follow-up, and that it remains unclear whether attainment of clinical remission warrants a drug holiday or cessation of RA treatment.

Thus, it is “ill-advised to discontinue therapy until future studies suggest otherwise,” they concluded, adding that this is particularly true given that prior published data suggest a link between osteitis – which occurred at a high rate in this study despite clinical remission – and future radiographic progression.

The TEAR trial was supported by Amgen. The current research was supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Science UCLA CTSI grant, and individual authors were supported by ACR/REF grants, a National Institutes of Health award, the Margaret J. Miller Endowed Professor of Research Chair, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Two years of either triple therapy or treatment with tumor necrosis factor plus methotrexate failed to eliminate joint inflammation on MRI in a subcohort of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis from the randomized, double-blind Treatment of Early Aggressive Rheumatoid Arthritis (TEAR) trial.

In 118 patients with a mean age of 51 years, short disease duration, and severe disease at TEAR trial entry – 92% of whom were seropositive – only 29 had wrist pain, tenderness, or swelling at 2-year follow-up. However, all 118 patients had MRI evidence of residual joint inflammation after 2 years, and 78% had evidence of osteitis, Dr. Veena K. Ranganath of the University of California, Los Angeles, and her colleagues reported (Arthritis Care Res. 2015 Jan. 7 [doi:10.1002/acr.22541]).

Inflammation remained despite significant improvement of disease activity measures at the time of the MRI, compared with baseline (for example, 28-joint disease activity score using erythrocyte sedimentation rate [DAS28-ESR] decreased from 5.8 to 2.9). Total MRI inflammation scores were significantly lower in patients who met 2011 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) Boolean remission criteria and remission by Chronic Disease Activity Index (CDAI), but not in those with DAS28-ESR remission, they noted.

The findings demonstrate that total MRI inflammatory scores are “best differentiated by the most stringent clinical remission criteria” – CDAI and 2011 ACR/EULAR Boolean Criteria, as opposed to DAS28-ESR (with a 2.6 cutpoint). Further, no differences were seen in damage or MRI inflammatory scores based on treatment regimen, which supports methotrexate-first recommendations for the TEAR trial, they said, noting that the long-term prognostic implications of the study findings are unclear because of short-follow-up, and that it remains unclear whether attainment of clinical remission warrants a drug holiday or cessation of RA treatment.

Thus, it is “ill-advised to discontinue therapy until future studies suggest otherwise,” they concluded, adding that this is particularly true given that prior published data suggest a link between osteitis – which occurred at a high rate in this study despite clinical remission – and future radiographic progression.

The TEAR trial was supported by Amgen. The current research was supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Science UCLA CTSI grant, and individual authors were supported by ACR/REF grants, a National Institutes of Health award, the Margaret J. Miller Endowed Professor of Research Chair, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Two years of either triple therapy or treatment with tumor necrosis factor plus methotrexate failed to eliminate joint inflammation on MRI in a subcohort of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis from the randomized, double-blind Treatment of Early Aggressive Rheumatoid Arthritis (TEAR) trial.

In 118 patients with a mean age of 51 years, short disease duration, and severe disease at TEAR trial entry – 92% of whom were seropositive – only 29 had wrist pain, tenderness, or swelling at 2-year follow-up. However, all 118 patients had MRI evidence of residual joint inflammation after 2 years, and 78% had evidence of osteitis, Dr. Veena K. Ranganath of the University of California, Los Angeles, and her colleagues reported (Arthritis Care Res. 2015 Jan. 7 [doi:10.1002/acr.22541]).

Inflammation remained despite significant improvement of disease activity measures at the time of the MRI, compared with baseline (for example, 28-joint disease activity score using erythrocyte sedimentation rate [DAS28-ESR] decreased from 5.8 to 2.9). Total MRI inflammation scores were significantly lower in patients who met 2011 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) Boolean remission criteria and remission by Chronic Disease Activity Index (CDAI), but not in those with DAS28-ESR remission, they noted.

The findings demonstrate that total MRI inflammatory scores are “best differentiated by the most stringent clinical remission criteria” – CDAI and 2011 ACR/EULAR Boolean Criteria, as opposed to DAS28-ESR (with a 2.6 cutpoint). Further, no differences were seen in damage or MRI inflammatory scores based on treatment regimen, which supports methotrexate-first recommendations for the TEAR trial, they said, noting that the long-term prognostic implications of the study findings are unclear because of short-follow-up, and that it remains unclear whether attainment of clinical remission warrants a drug holiday or cessation of RA treatment.

Thus, it is “ill-advised to discontinue therapy until future studies suggest otherwise,” they concluded, adding that this is particularly true given that prior published data suggest a link between osteitis – which occurred at a high rate in this study despite clinical remission – and future radiographic progression.

The TEAR trial was supported by Amgen. The current research was supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Science UCLA CTSI grant, and individual authors were supported by ACR/REF grants, a National Institutes of Health award, the Margaret J. Miller Endowed Professor of Research Chair, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Until data suggest otherwise, treatment should continue despite clinical remission in early RA patients.

Major finding: Only 29 of 118 patients had symptoms, but all 118 had MRI evidence of inflammation.

Data source: A subcohort of 118 patients from the randomized, double-blind TEAR trial .

Disclosures: The TEAR trial was supported by Amgen. The current research was supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Science UCLA CTSI grant, and individual authors were supported by ACR/REF grants, a National Institutes of Health award, the Margaret J. Miller Endowed Professor of Research Chair, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Zero coronary calcium means very low 10-year event risk

CHICAGO – Absence of coronary artery calcium upon imaging results in an impressively low cardiovascular event rate over the next 10 years regardless of an individual’s level of standard risk factors, according to prospective data from the MESA study.

In contrast, a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score of 1-10, often described as minimal CAC, nearly doubles the 10-year risk, compared with a baseline CAC score of 0.

Prior to these new 10-year data, many cardiologists considered a CAC score of 1-10 as tantamount to no CAC. Not so, Dr. Parag H. Joshi said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“A CAC of 0 is presumably identifying someone without any atherosclerosis. Just the presence of minimal calcium suggests that atherosclerosis is building up. Our data suggest that among individuals with a CAC of 1-10, current smoking, elevated non-HDL cholesterol, and particularly hypertension should be treated aggressively,” said Dr. Joshi, a clinical fellow in cardiovascular diseases and prevention at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Prior studies totaling more than 50,000 subjects with a CAC score of 0 have shown very low cardiovascular event rates over 4-5 years of follow-up. However, current cardiovascular risk estimates focus on 10-year risk. This new analysis from MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) is the first study to provide prospective, 10-year events data, and those data are highly reassuring, he added.

MESA is a prospective, population-based cohort study. This analysis included 6,814 subjects aged 45-84 who were free of clinical cardiovascular disease at baseline, when their CAC score was determined. At that time, 3,415 participants had a CAC score of 0 and 508 had a score of 1-10.

During a median 10.3 years of follow-up, 123 cardiovascular events occurred, roughly one-third of which were nonfatal acute MIs and half of which were nonfatal strokes; the remainder were cardiovascular deaths.

The event rate was 2.9/1,000 person-years in subjects with a CAC of 0 and significantly greater at 5.5/1,000 person-years with a score of 1-10. However, since the cardiovascular risk factor profile of the zero CAC group was generally more favorable, Dr. Joshi and coinvestigators carried out a Cox proportional hazards analysis factoring in demographics, standard cardiovascular risk factors, body mass index, C-reactive protein level, and carotid intima media thickness. The adjusted 10-year event risk in the group with a CAC score of 1-10 was 1.9-fold greater than with a CAC of 0.

The highest 10-year event rate was noted in subjects with at least three of the following four risk factors at baseline: hypertension, current smoking, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. The rate was 6.5/1,000 person-years in such individuals if they had a CAC of 0 and doubled at 13.1/1,000 person-years with a score of 1-10.

In a multivariate Cox analysis, age, smoking, and hypertension proved to be significant predictors of cardiovascular events in the group with a CAC of 0 as well as in those with a CAC of 1-10. But there was one important difference between the two groups: While the hazard ratio for cardiovascular events associated with hypertension versus no hypertension was 2.1 in subjects with a CAC of 0, the presence of hypertension in individuals with a CAC of 1-10 increased their event risk by 10.2-fold, or nearly five times greater than the risk increase associated with hypertension in persons with a CAC of 0, Dr. Joshi observed.

Non–HDL cholesterol level was predictive of cardiovascular risk in subjects with a CAC of 1-10 but not in those with a score of 0.

When actual event rates were compared with those predicted by the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk estimator introduced in the 2013 AHA/American College of Cardiology cholesterol guidelines, the event rate in subjects with an ASCVD 10-year risk estimate of 7.5%-15% but a CAC of 0 was just 4.4%.

Audience members noted that CAC scores didn’t do a very good job of stratifying stroke risk in MESA. That’s not surprising, since the score reflects coronary but not carotid artery calcium. But it is a limitation of CAC as a predictive tool, especially in light of the fact that strokes accounted for half of all cardiovascular events in the study.

Asked where he and his coinvestigators plan to go from here, Dr. Joshi said a randomized, controlled trial would be ideal, but to date funding isn’t available. However, the observational data from MESA and other studies suggest such a trial may not even be needed.

“Certainly the guidelines do allow for CAC scoring to be used in clinical decision making,” he noted.

The MESA study is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Joshi reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – Absence of coronary artery calcium upon imaging results in an impressively low cardiovascular event rate over the next 10 years regardless of an individual’s level of standard risk factors, according to prospective data from the MESA study.

In contrast, a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score of 1-10, often described as minimal CAC, nearly doubles the 10-year risk, compared with a baseline CAC score of 0.

Prior to these new 10-year data, many cardiologists considered a CAC score of 1-10 as tantamount to no CAC. Not so, Dr. Parag H. Joshi said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“A CAC of 0 is presumably identifying someone without any atherosclerosis. Just the presence of minimal calcium suggests that atherosclerosis is building up. Our data suggest that among individuals with a CAC of 1-10, current smoking, elevated non-HDL cholesterol, and particularly hypertension should be treated aggressively,” said Dr. Joshi, a clinical fellow in cardiovascular diseases and prevention at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Prior studies totaling more than 50,000 subjects with a CAC score of 0 have shown very low cardiovascular event rates over 4-5 years of follow-up. However, current cardiovascular risk estimates focus on 10-year risk. This new analysis from MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) is the first study to provide prospective, 10-year events data, and those data are highly reassuring, he added.

MESA is a prospective, population-based cohort study. This analysis included 6,814 subjects aged 45-84 who were free of clinical cardiovascular disease at baseline, when their CAC score was determined. At that time, 3,415 participants had a CAC score of 0 and 508 had a score of 1-10.

During a median 10.3 years of follow-up, 123 cardiovascular events occurred, roughly one-third of which were nonfatal acute MIs and half of which were nonfatal strokes; the remainder were cardiovascular deaths.

The event rate was 2.9/1,000 person-years in subjects with a CAC of 0 and significantly greater at 5.5/1,000 person-years with a score of 1-10. However, since the cardiovascular risk factor profile of the zero CAC group was generally more favorable, Dr. Joshi and coinvestigators carried out a Cox proportional hazards analysis factoring in demographics, standard cardiovascular risk factors, body mass index, C-reactive protein level, and carotid intima media thickness. The adjusted 10-year event risk in the group with a CAC score of 1-10 was 1.9-fold greater than with a CAC of 0.

The highest 10-year event rate was noted in subjects with at least three of the following four risk factors at baseline: hypertension, current smoking, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. The rate was 6.5/1,000 person-years in such individuals if they had a CAC of 0 and doubled at 13.1/1,000 person-years with a score of 1-10.

In a multivariate Cox analysis, age, smoking, and hypertension proved to be significant predictors of cardiovascular events in the group with a CAC of 0 as well as in those with a CAC of 1-10. But there was one important difference between the two groups: While the hazard ratio for cardiovascular events associated with hypertension versus no hypertension was 2.1 in subjects with a CAC of 0, the presence of hypertension in individuals with a CAC of 1-10 increased their event risk by 10.2-fold, or nearly five times greater than the risk increase associated with hypertension in persons with a CAC of 0, Dr. Joshi observed.

Non–HDL cholesterol level was predictive of cardiovascular risk in subjects with a CAC of 1-10 but not in those with a score of 0.

When actual event rates were compared with those predicted by the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk estimator introduced in the 2013 AHA/American College of Cardiology cholesterol guidelines, the event rate in subjects with an ASCVD 10-year risk estimate of 7.5%-15% but a CAC of 0 was just 4.4%.

Audience members noted that CAC scores didn’t do a very good job of stratifying stroke risk in MESA. That’s not surprising, since the score reflects coronary but not carotid artery calcium. But it is a limitation of CAC as a predictive tool, especially in light of the fact that strokes accounted for half of all cardiovascular events in the study.

Asked where he and his coinvestigators plan to go from here, Dr. Joshi said a randomized, controlled trial would be ideal, but to date funding isn’t available. However, the observational data from MESA and other studies suggest such a trial may not even be needed.

“Certainly the guidelines do allow for CAC scoring to be used in clinical decision making,” he noted.

The MESA study is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Joshi reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – Absence of coronary artery calcium upon imaging results in an impressively low cardiovascular event rate over the next 10 years regardless of an individual’s level of standard risk factors, according to prospective data from the MESA study.

In contrast, a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score of 1-10, often described as minimal CAC, nearly doubles the 10-year risk, compared with a baseline CAC score of 0.

Prior to these new 10-year data, many cardiologists considered a CAC score of 1-10 as tantamount to no CAC. Not so, Dr. Parag H. Joshi said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“A CAC of 0 is presumably identifying someone without any atherosclerosis. Just the presence of minimal calcium suggests that atherosclerosis is building up. Our data suggest that among individuals with a CAC of 1-10, current smoking, elevated non-HDL cholesterol, and particularly hypertension should be treated aggressively,” said Dr. Joshi, a clinical fellow in cardiovascular diseases and prevention at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Prior studies totaling more than 50,000 subjects with a CAC score of 0 have shown very low cardiovascular event rates over 4-5 years of follow-up. However, current cardiovascular risk estimates focus on 10-year risk. This new analysis from MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) is the first study to provide prospective, 10-year events data, and those data are highly reassuring, he added.

MESA is a prospective, population-based cohort study. This analysis included 6,814 subjects aged 45-84 who were free of clinical cardiovascular disease at baseline, when their CAC score was determined. At that time, 3,415 participants had a CAC score of 0 and 508 had a score of 1-10.

During a median 10.3 years of follow-up, 123 cardiovascular events occurred, roughly one-third of which were nonfatal acute MIs and half of which were nonfatal strokes; the remainder were cardiovascular deaths.

The event rate was 2.9/1,000 person-years in subjects with a CAC of 0 and significantly greater at 5.5/1,000 person-years with a score of 1-10. However, since the cardiovascular risk factor profile of the zero CAC group was generally more favorable, Dr. Joshi and coinvestigators carried out a Cox proportional hazards analysis factoring in demographics, standard cardiovascular risk factors, body mass index, C-reactive protein level, and carotid intima media thickness. The adjusted 10-year event risk in the group with a CAC score of 1-10 was 1.9-fold greater than with a CAC of 0.

The highest 10-year event rate was noted in subjects with at least three of the following four risk factors at baseline: hypertension, current smoking, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. The rate was 6.5/1,000 person-years in such individuals if they had a CAC of 0 and doubled at 13.1/1,000 person-years with a score of 1-10.

In a multivariate Cox analysis, age, smoking, and hypertension proved to be significant predictors of cardiovascular events in the group with a CAC of 0 as well as in those with a CAC of 1-10. But there was one important difference between the two groups: While the hazard ratio for cardiovascular events associated with hypertension versus no hypertension was 2.1 in subjects with a CAC of 0, the presence of hypertension in individuals with a CAC of 1-10 increased their event risk by 10.2-fold, or nearly five times greater than the risk increase associated with hypertension in persons with a CAC of 0, Dr. Joshi observed.

Non–HDL cholesterol level was predictive of cardiovascular risk in subjects with a CAC of 1-10 but not in those with a score of 0.

When actual event rates were compared with those predicted by the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk estimator introduced in the 2013 AHA/American College of Cardiology cholesterol guidelines, the event rate in subjects with an ASCVD 10-year risk estimate of 7.5%-15% but a CAC of 0 was just 4.4%.

Audience members noted that CAC scores didn’t do a very good job of stratifying stroke risk in MESA. That’s not surprising, since the score reflects coronary but not carotid artery calcium. But it is a limitation of CAC as a predictive tool, especially in light of the fact that strokes accounted for half of all cardiovascular events in the study.

Asked where he and his coinvestigators plan to go from here, Dr. Joshi said a randomized, controlled trial would be ideal, but to date funding isn’t available. However, the observational data from MESA and other studies suggest such a trial may not even be needed.

“Certainly the guidelines do allow for CAC scoring to be used in clinical decision making,” he noted.

The MESA study is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Joshi reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: A coronary artery calcium score of 0 appears to trump the 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk estimator introduced in the 2013 AHA/ACC cholesterol guidelines.

Major finding: The actual 10-year cardiovascular event rate in subjects with a coronary artery calcium score of 0 was just 4.4% – below the guideline-recommended threshold for statin therapy– even though their predicted risk using the AHA/ACC risk estimator was 7.5%-15%.

Data source: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis is a prospective, population-based cohort study. This analysis included 6,814 subjects aged 45-84 who were free of clinical cardiovascular disease at baseline.

Disclosures: The MESA study is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Emergency cardiac echocardiography accepted by Europeans

VIENNA – Rapid echocardiographic assessment has become routine for many patients who arrive at an emergency department with suspected acute heart failure, and experts consider these examinations critical for quickly getting patients on the right treatment.

Growing use and the important role for emergency echo exams prompted the European echocardiography community to issue in 2014 both recommendations and a position statement on the practice.

With their actions, European echocardiographers joined their U.S. colleagues who had earlier endorsed rapid, focused echocardiography exams. The European position also highlighted the limitations and pitfalls of emergency echo and the need for proper training.

Use of limited, directed, ultrasound heart examinations on an emergency basis by physicians who are not cardiologists is “an irreversible process, but without appropriate training it may become dangerous,” Dr. Nuno Cardim said at the annual meeting of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI).

A focused cardiac ultrasound (FoCUS) examination for patients with an emergency cardiac condition such as acute heart failure is not a new concept. In 2010, the American Society of Echocardiography and the American College of Emergency Physicians jointly issued a consensus statement on emergency FoCUS (J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010;23:1225-30), and the American Society of Echocardiography followed with additional recommendations in 2013 that also dealt with nonemergency uses for FoCUS (J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2013;26:567-81).