User login

Case

A 46-year-old white woman with sudden onset of numbness in her lower extremities and inability to ambulate was transported to the ED via emergency medical services. At the onset of symptoms, the patient reported a feeling of “heaviness” in her lower extremities, which was greater on the left side than the right. After an unsuccessful attempt at ambulation, she subsequently presented to a community hospital where she could no longer move her left lower extremity. Upon evaluation, the patient was found to have progressive neurological deficits and was transferred by ambulance to the authors’ tertiary medical center for definitive management.

A review of the patient’s recent symptoms indicated that she had also experienced lower abdominal paresthesias of 5 days’ duration. She described this sensation as sharp, numb, and constant since its onset and unrelieved with the use of a muscle relaxant at home. She further noted that the pain became worse with movement, having no palliative modifying factors. Upon further questioning, the patient acknowledged recent urinary incontinence of unknown duration, nausea, and current menstruation. She denied any recent injury or illness.

Her past medical history was unknown, and she stated that she had not seen a physician in several years. The patient’s surgical history included a tonsillectomy and an appendectomy at a young age. She had no known drug allergies. Although she denied the use of medications, electronic medical records show that the patient had been prescribed baclofen, hydrochlorothiazide, metoprolol, and tramadol. She was unaware of her family’s medical history and denied use of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs.

Upon physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 161/99 mm Hg; heart rate, 103 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/minute; oxygen saturation, 97% on room air; and temperature, 97.0°F. She appeared to be a middle-aged obese woman in no apparent distress and was alert with normal mentation, lying comfortably on the gurney.

The head and neck examinations were normal. Lung auscultation demonstrated equal and unlabored breath sounds bilaterally with no adventitious sounds. Incidentally, it was noted at this time that the left breast had a significantly large fungating mass about the areola and within the deep tissue that was visually evidenced by prominent erythema and classic peau d’orange skin. The right breast had minimal skin involvement with a smaller palpable mass below the dermal surface. Both breast masses and enlarged axillary lymph nodes on the left were nontender. The cardiovascular examination demonstrated mild tachycardia with normal heart sounds, no extremity edema, and normal pulses throughout. The gastrointestinal examination had normal borborygmus with mild infraabdominal tenderness to palpation superficially over a nondistended abdomen. Neither organomegaly, hernia, nor masses were appreciated. In addition to urinary incontinence, the patient also had fecal incontinence, which correlated with diminished tone on digital rectal examination.

Neurological sensation was intact in all extremities and no deficits were noted in the cranial nerves. Patellar and ankle tendon-testing demonstrated left-sided hyperreflexia with ipsilateral Babinski reflex exhibiting up-going toes. Musculoskeletal weakness was grossly noted in the left lower extremity to be +2/5, whereas the right lower limb had +4/5 strength. Palpation of the thoracic and lumbar spines did not elicit tenderness. Aside from the aforementioned observations, no additional integumentary findings were noted.

The patient was given oxygen by nasal cannula, connected to cardiac monitoring and pulse oximetry. A urinary catheter was inserted, and she was given parenteral dexamethasone,3 morphine sulfate, ondansetron, and normal saline. An electrocardiogram showed a normal sinus rhythm. A chest X-ray and basic blood analysis were ordered in preparation for the likelihood of surgical management. Neurosurgery and radiology were consulted. Emergent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine with and without contrast was obtained to rule out SCC.

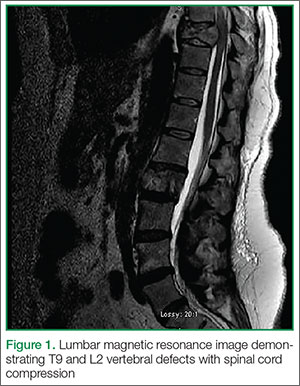

The MRI of the spine revealed pathologic fractures leading to cord compression at T9 and spinal stenosis at the L2 segment (Figure 1); diffuse bone metastasis of the spine was also observed. Subsequent surgical decompressive laminectomy from T7 to L3 was performed without complication. Despite the reportedly poor outcome in CMS,2,4-6 the patient demonstrated a moderate return of strength, sensation, and function within the first month of postoperative follow-up. At 3 months, she had minimal subjective and objective deficits and was ambulating without difficulty. She denied urinary and fecal incontinence during these periods. The biopsied breast mass was determined to be stage IV infiltrating ductal carcinoma mucinous type, for which she was followed by an oncologist and received radiation and chemotherapy.

Discussion

The patient’s chief complaint of lower extremity muscle weakness was a clinical emergency that merited thorough investigation in a timely manner to preserve limb function. Since her medical history did not provide pathologic insight concerning her condition, physical examination by emergency personnel served as the founding evidence for this patient’s diagnosis. Decreased muscle tone of the lower extremities and rectal sphincter raised suspicion for a neurological etiology. These symptoms, along with hyperreflexia, the presence of a Babinski sign, and dual-system incontinence, were suggestive of an underlying central nervous system lesion. Of note, urinary complaints commonly result from retention leading to overflow incontinence, a time-dependent symptom that may not be experienced before presentation to medical personnel. Urinary retention is one of the most consistent findings in patients with CMS and SCC, with a relative prevalence of 90%.4,7,8

For providers not familiar with CMS presentation, preserved tactile sensation, normoreflexia, and lack of a Babinski sign and/or incontinence are not sufficient indicators to discontinue the consideration of spinal cord lesions in the differential diagnosis and may in fact be misleading.6,9,10 Although the patient’s deficits were not symmetrical as is commonly reported, this did not rule out the diagnosis.

Appropriate diagnosis and treatment of such a rare entity in the emergency setting consists of a high clinical suspicion, MRI of the spine, urgent consultations, and early treatment with parenteral corticosteroids.3,4 The patient did not have a previous diagnosis of breast carcinoma; however, once discovered on examination, the condition became suspect as approximately 80% of patients with SCC have a preexisting cancer. The peak incidence of SCC is in the sixth and seventh decades of life. The most common primary cancers metastasizing to bone are breast, prostate, and lung. When found to affect the spine, roughly 60% will be located in the thoracic spine, 30% at the lumbosacral level, and 10% in the cervical spine.

As demonstrated in this case presentation, a thorough examination cannot be stressed enough in emergent situations. The patient’s dermatological findings and nontender lymphadenopathy were adequately significant to consider the possibility of a metastatic process as the underlying etiology. Although discouraged due to the fast-paced environment of the ED, patients are frequently assessed and examined in street clothing, which in this case, may have masked the underlying cause of the patient’s neurological deficits. As a result, imaging studies, corticosteroid treatment, consultations, and surgical management may have been delayed, leading to a nonreversible outcome for the patient.

Central and Peripheral Nervous System Structures and Deficits

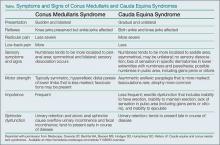

Central and peripheral nervous system structures animate the body through coordinated signaling of upper and lower motor neurons respectively. In most adults, the distal spinal cord terminates at the level of the first or second lumbar vertebrae where the conus medullaris is found, giving rise to S2, S3 and S4 functionality. Lesions at this level exhibit lower motor neuron deficits of the bladder and rectum resulting in incontinence and sexual dysfunction. Deficits of sensorium such as saddle anesthesia or upper motor neuron lesions as evidenced by increased motor tone and abnormal reflexes are not uncommon.1 Branches of the cauda equina extend caudally from the epiconus, a structure proximal to the conus medullaris, as peripheral nervous system branches that innervate spinal cord segments L4 through S1 (Figure 2). Lesions of the epiconus are clinically distinguished by lower motor neuron deficits wherein muscles of the lower extremities are often weakened with potential sparing of the bulbocavernosus and micturition reflexes.2

Conclusion

While many EPs are cognizant of cauda equina syndrome and its presentation, CMS is less well known and not commonly documented. Due to symptomatic overlap and epidemiological rarity of these conditions, most of the literature describing these entities combines their discussion. This case contributes to the growing body of literature to assist clinicians in the evaluation and management of CMS.

Dr Batt is an emergency medicine resident, Arrowhead Regional Medical Center, Colton, California. Dr Stone is the emergency medical services director, Travis Air Force Base, Fairfield, California.

- Lewandrowski KU, McLain RF, Lieberman I, Orr D. Cord and cauda equina injury complicating elective orthopedic surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(9):1056-1059.

- Kirshblum S, Anderson K, Krassioukov A, Donovan W. Assessment and classification of traumatic spinal cord injury. In: Kirshblum S, Campagnolo DI, eds. Spinal Cord Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

- Ruckdeschel JC. Early detection and treatment of spinal cord compression. Oncology (Williston Park). 2005;19(1):81-86.

- Perron AD, Huff JS. Spinal cord disorders. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2013; 1419-1427.

- Wagner R, Jagoda A. Spinal cord syndromes. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1997;15(3):699-711.

- Sciubba DM, Gokaslan ZL. Diagnosis and management of metastatic spine disease. Surg Oncol. 2006;15(3):141-151.

- Jalloh I, Minhas P. Delays in the treatment of cauda equina syndrome due to its variable clinical features in patients presenting to the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(1):33-34.

- Korse NS, Jacobs WCH, Elzevier HW, Vieggeert-Lankamp CL. Complaints of micturition, defecation and sexual function in cauda equina syndrome due to lumbar disk herniation: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(5):1019-1029.

- Dawodu ST, Bechtel KA, Beeson MS, et al. Cauda equina and conus medullaris syndromes. Medscape Web site. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1148690-clinical. Accessed September 1, 2014.

- Glick TH, Workman TP, Gaufberg SV. Spinal cord emergencies: false reassurance from reflexes. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(10):1041-1043.

Case

A 46-year-old white woman with sudden onset of numbness in her lower extremities and inability to ambulate was transported to the ED via emergency medical services. At the onset of symptoms, the patient reported a feeling of “heaviness” in her lower extremities, which was greater on the left side than the right. After an unsuccessful attempt at ambulation, she subsequently presented to a community hospital where she could no longer move her left lower extremity. Upon evaluation, the patient was found to have progressive neurological deficits and was transferred by ambulance to the authors’ tertiary medical center for definitive management.

A review of the patient’s recent symptoms indicated that she had also experienced lower abdominal paresthesias of 5 days’ duration. She described this sensation as sharp, numb, and constant since its onset and unrelieved with the use of a muscle relaxant at home. She further noted that the pain became worse with movement, having no palliative modifying factors. Upon further questioning, the patient acknowledged recent urinary incontinence of unknown duration, nausea, and current menstruation. She denied any recent injury or illness.

Her past medical history was unknown, and she stated that she had not seen a physician in several years. The patient’s surgical history included a tonsillectomy and an appendectomy at a young age. She had no known drug allergies. Although she denied the use of medications, electronic medical records show that the patient had been prescribed baclofen, hydrochlorothiazide, metoprolol, and tramadol. She was unaware of her family’s medical history and denied use of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs.

Upon physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 161/99 mm Hg; heart rate, 103 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/minute; oxygen saturation, 97% on room air; and temperature, 97.0°F. She appeared to be a middle-aged obese woman in no apparent distress and was alert with normal mentation, lying comfortably on the gurney.

The head and neck examinations were normal. Lung auscultation demonstrated equal and unlabored breath sounds bilaterally with no adventitious sounds. Incidentally, it was noted at this time that the left breast had a significantly large fungating mass about the areola and within the deep tissue that was visually evidenced by prominent erythema and classic peau d’orange skin. The right breast had minimal skin involvement with a smaller palpable mass below the dermal surface. Both breast masses and enlarged axillary lymph nodes on the left were nontender. The cardiovascular examination demonstrated mild tachycardia with normal heart sounds, no extremity edema, and normal pulses throughout. The gastrointestinal examination had normal borborygmus with mild infraabdominal tenderness to palpation superficially over a nondistended abdomen. Neither organomegaly, hernia, nor masses were appreciated. In addition to urinary incontinence, the patient also had fecal incontinence, which correlated with diminished tone on digital rectal examination.

Neurological sensation was intact in all extremities and no deficits were noted in the cranial nerves. Patellar and ankle tendon-testing demonstrated left-sided hyperreflexia with ipsilateral Babinski reflex exhibiting up-going toes. Musculoskeletal weakness was grossly noted in the left lower extremity to be +2/5, whereas the right lower limb had +4/5 strength. Palpation of the thoracic and lumbar spines did not elicit tenderness. Aside from the aforementioned observations, no additional integumentary findings were noted.

The patient was given oxygen by nasal cannula, connected to cardiac monitoring and pulse oximetry. A urinary catheter was inserted, and she was given parenteral dexamethasone,3 morphine sulfate, ondansetron, and normal saline. An electrocardiogram showed a normal sinus rhythm. A chest X-ray and basic blood analysis were ordered in preparation for the likelihood of surgical management. Neurosurgery and radiology were consulted. Emergent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine with and without contrast was obtained to rule out SCC.

The MRI of the spine revealed pathologic fractures leading to cord compression at T9 and spinal stenosis at the L2 segment (Figure 1); diffuse bone metastasis of the spine was also observed. Subsequent surgical decompressive laminectomy from T7 to L3 was performed without complication. Despite the reportedly poor outcome in CMS,2,4-6 the patient demonstrated a moderate return of strength, sensation, and function within the first month of postoperative follow-up. At 3 months, she had minimal subjective and objective deficits and was ambulating without difficulty. She denied urinary and fecal incontinence during these periods. The biopsied breast mass was determined to be stage IV infiltrating ductal carcinoma mucinous type, for which she was followed by an oncologist and received radiation and chemotherapy.

Discussion

The patient’s chief complaint of lower extremity muscle weakness was a clinical emergency that merited thorough investigation in a timely manner to preserve limb function. Since her medical history did not provide pathologic insight concerning her condition, physical examination by emergency personnel served as the founding evidence for this patient’s diagnosis. Decreased muscle tone of the lower extremities and rectal sphincter raised suspicion for a neurological etiology. These symptoms, along with hyperreflexia, the presence of a Babinski sign, and dual-system incontinence, were suggestive of an underlying central nervous system lesion. Of note, urinary complaints commonly result from retention leading to overflow incontinence, a time-dependent symptom that may not be experienced before presentation to medical personnel. Urinary retention is one of the most consistent findings in patients with CMS and SCC, with a relative prevalence of 90%.4,7,8

For providers not familiar with CMS presentation, preserved tactile sensation, normoreflexia, and lack of a Babinski sign and/or incontinence are not sufficient indicators to discontinue the consideration of spinal cord lesions in the differential diagnosis and may in fact be misleading.6,9,10 Although the patient’s deficits were not symmetrical as is commonly reported, this did not rule out the diagnosis.

Appropriate diagnosis and treatment of such a rare entity in the emergency setting consists of a high clinical suspicion, MRI of the spine, urgent consultations, and early treatment with parenteral corticosteroids.3,4 The patient did not have a previous diagnosis of breast carcinoma; however, once discovered on examination, the condition became suspect as approximately 80% of patients with SCC have a preexisting cancer. The peak incidence of SCC is in the sixth and seventh decades of life. The most common primary cancers metastasizing to bone are breast, prostate, and lung. When found to affect the spine, roughly 60% will be located in the thoracic spine, 30% at the lumbosacral level, and 10% in the cervical spine.

As demonstrated in this case presentation, a thorough examination cannot be stressed enough in emergent situations. The patient’s dermatological findings and nontender lymphadenopathy were adequately significant to consider the possibility of a metastatic process as the underlying etiology. Although discouraged due to the fast-paced environment of the ED, patients are frequently assessed and examined in street clothing, which in this case, may have masked the underlying cause of the patient’s neurological deficits. As a result, imaging studies, corticosteroid treatment, consultations, and surgical management may have been delayed, leading to a nonreversible outcome for the patient.

Central and Peripheral Nervous System Structures and Deficits

Central and peripheral nervous system structures animate the body through coordinated signaling of upper and lower motor neurons respectively. In most adults, the distal spinal cord terminates at the level of the first or second lumbar vertebrae where the conus medullaris is found, giving rise to S2, S3 and S4 functionality. Lesions at this level exhibit lower motor neuron deficits of the bladder and rectum resulting in incontinence and sexual dysfunction. Deficits of sensorium such as saddle anesthesia or upper motor neuron lesions as evidenced by increased motor tone and abnormal reflexes are not uncommon.1 Branches of the cauda equina extend caudally from the epiconus, a structure proximal to the conus medullaris, as peripheral nervous system branches that innervate spinal cord segments L4 through S1 (Figure 2). Lesions of the epiconus are clinically distinguished by lower motor neuron deficits wherein muscles of the lower extremities are often weakened with potential sparing of the bulbocavernosus and micturition reflexes.2

Conclusion

While many EPs are cognizant of cauda equina syndrome and its presentation, CMS is less well known and not commonly documented. Due to symptomatic overlap and epidemiological rarity of these conditions, most of the literature describing these entities combines their discussion. This case contributes to the growing body of literature to assist clinicians in the evaluation and management of CMS.

Dr Batt is an emergency medicine resident, Arrowhead Regional Medical Center, Colton, California. Dr Stone is the emergency medical services director, Travis Air Force Base, Fairfield, California.

Case

A 46-year-old white woman with sudden onset of numbness in her lower extremities and inability to ambulate was transported to the ED via emergency medical services. At the onset of symptoms, the patient reported a feeling of “heaviness” in her lower extremities, which was greater on the left side than the right. After an unsuccessful attempt at ambulation, she subsequently presented to a community hospital where she could no longer move her left lower extremity. Upon evaluation, the patient was found to have progressive neurological deficits and was transferred by ambulance to the authors’ tertiary medical center for definitive management.

A review of the patient’s recent symptoms indicated that she had also experienced lower abdominal paresthesias of 5 days’ duration. She described this sensation as sharp, numb, and constant since its onset and unrelieved with the use of a muscle relaxant at home. She further noted that the pain became worse with movement, having no palliative modifying factors. Upon further questioning, the patient acknowledged recent urinary incontinence of unknown duration, nausea, and current menstruation. She denied any recent injury or illness.

Her past medical history was unknown, and she stated that she had not seen a physician in several years. The patient’s surgical history included a tonsillectomy and an appendectomy at a young age. She had no known drug allergies. Although she denied the use of medications, electronic medical records show that the patient had been prescribed baclofen, hydrochlorothiazide, metoprolol, and tramadol. She was unaware of her family’s medical history and denied use of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs.

Upon physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 161/99 mm Hg; heart rate, 103 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/minute; oxygen saturation, 97% on room air; and temperature, 97.0°F. She appeared to be a middle-aged obese woman in no apparent distress and was alert with normal mentation, lying comfortably on the gurney.

The head and neck examinations were normal. Lung auscultation demonstrated equal and unlabored breath sounds bilaterally with no adventitious sounds. Incidentally, it was noted at this time that the left breast had a significantly large fungating mass about the areola and within the deep tissue that was visually evidenced by prominent erythema and classic peau d’orange skin. The right breast had minimal skin involvement with a smaller palpable mass below the dermal surface. Both breast masses and enlarged axillary lymph nodes on the left were nontender. The cardiovascular examination demonstrated mild tachycardia with normal heart sounds, no extremity edema, and normal pulses throughout. The gastrointestinal examination had normal borborygmus with mild infraabdominal tenderness to palpation superficially over a nondistended abdomen. Neither organomegaly, hernia, nor masses were appreciated. In addition to urinary incontinence, the patient also had fecal incontinence, which correlated with diminished tone on digital rectal examination.

Neurological sensation was intact in all extremities and no deficits were noted in the cranial nerves. Patellar and ankle tendon-testing demonstrated left-sided hyperreflexia with ipsilateral Babinski reflex exhibiting up-going toes. Musculoskeletal weakness was grossly noted in the left lower extremity to be +2/5, whereas the right lower limb had +4/5 strength. Palpation of the thoracic and lumbar spines did not elicit tenderness. Aside from the aforementioned observations, no additional integumentary findings were noted.

The patient was given oxygen by nasal cannula, connected to cardiac monitoring and pulse oximetry. A urinary catheter was inserted, and she was given parenteral dexamethasone,3 morphine sulfate, ondansetron, and normal saline. An electrocardiogram showed a normal sinus rhythm. A chest X-ray and basic blood analysis were ordered in preparation for the likelihood of surgical management. Neurosurgery and radiology were consulted. Emergent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine with and without contrast was obtained to rule out SCC.

The MRI of the spine revealed pathologic fractures leading to cord compression at T9 and spinal stenosis at the L2 segment (Figure 1); diffuse bone metastasis of the spine was also observed. Subsequent surgical decompressive laminectomy from T7 to L3 was performed without complication. Despite the reportedly poor outcome in CMS,2,4-6 the patient demonstrated a moderate return of strength, sensation, and function within the first month of postoperative follow-up. At 3 months, she had minimal subjective and objective deficits and was ambulating without difficulty. She denied urinary and fecal incontinence during these periods. The biopsied breast mass was determined to be stage IV infiltrating ductal carcinoma mucinous type, for which she was followed by an oncologist and received radiation and chemotherapy.

Discussion

The patient’s chief complaint of lower extremity muscle weakness was a clinical emergency that merited thorough investigation in a timely manner to preserve limb function. Since her medical history did not provide pathologic insight concerning her condition, physical examination by emergency personnel served as the founding evidence for this patient’s diagnosis. Decreased muscle tone of the lower extremities and rectal sphincter raised suspicion for a neurological etiology. These symptoms, along with hyperreflexia, the presence of a Babinski sign, and dual-system incontinence, were suggestive of an underlying central nervous system lesion. Of note, urinary complaints commonly result from retention leading to overflow incontinence, a time-dependent symptom that may not be experienced before presentation to medical personnel. Urinary retention is one of the most consistent findings in patients with CMS and SCC, with a relative prevalence of 90%.4,7,8

For providers not familiar with CMS presentation, preserved tactile sensation, normoreflexia, and lack of a Babinski sign and/or incontinence are not sufficient indicators to discontinue the consideration of spinal cord lesions in the differential diagnosis and may in fact be misleading.6,9,10 Although the patient’s deficits were not symmetrical as is commonly reported, this did not rule out the diagnosis.

Appropriate diagnosis and treatment of such a rare entity in the emergency setting consists of a high clinical suspicion, MRI of the spine, urgent consultations, and early treatment with parenteral corticosteroids.3,4 The patient did not have a previous diagnosis of breast carcinoma; however, once discovered on examination, the condition became suspect as approximately 80% of patients with SCC have a preexisting cancer. The peak incidence of SCC is in the sixth and seventh decades of life. The most common primary cancers metastasizing to bone are breast, prostate, and lung. When found to affect the spine, roughly 60% will be located in the thoracic spine, 30% at the lumbosacral level, and 10% in the cervical spine.

As demonstrated in this case presentation, a thorough examination cannot be stressed enough in emergent situations. The patient’s dermatological findings and nontender lymphadenopathy were adequately significant to consider the possibility of a metastatic process as the underlying etiology. Although discouraged due to the fast-paced environment of the ED, patients are frequently assessed and examined in street clothing, which in this case, may have masked the underlying cause of the patient’s neurological deficits. As a result, imaging studies, corticosteroid treatment, consultations, and surgical management may have been delayed, leading to a nonreversible outcome for the patient.

Central and Peripheral Nervous System Structures and Deficits

Central and peripheral nervous system structures animate the body through coordinated signaling of upper and lower motor neurons respectively. In most adults, the distal spinal cord terminates at the level of the first or second lumbar vertebrae where the conus medullaris is found, giving rise to S2, S3 and S4 functionality. Lesions at this level exhibit lower motor neuron deficits of the bladder and rectum resulting in incontinence and sexual dysfunction. Deficits of sensorium such as saddle anesthesia or upper motor neuron lesions as evidenced by increased motor tone and abnormal reflexes are not uncommon.1 Branches of the cauda equina extend caudally from the epiconus, a structure proximal to the conus medullaris, as peripheral nervous system branches that innervate spinal cord segments L4 through S1 (Figure 2). Lesions of the epiconus are clinically distinguished by lower motor neuron deficits wherein muscles of the lower extremities are often weakened with potential sparing of the bulbocavernosus and micturition reflexes.2

Conclusion

While many EPs are cognizant of cauda equina syndrome and its presentation, CMS is less well known and not commonly documented. Due to symptomatic overlap and epidemiological rarity of these conditions, most of the literature describing these entities combines their discussion. This case contributes to the growing body of literature to assist clinicians in the evaluation and management of CMS.

Dr Batt is an emergency medicine resident, Arrowhead Regional Medical Center, Colton, California. Dr Stone is the emergency medical services director, Travis Air Force Base, Fairfield, California.

- Lewandrowski KU, McLain RF, Lieberman I, Orr D. Cord and cauda equina injury complicating elective orthopedic surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(9):1056-1059.

- Kirshblum S, Anderson K, Krassioukov A, Donovan W. Assessment and classification of traumatic spinal cord injury. In: Kirshblum S, Campagnolo DI, eds. Spinal Cord Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

- Ruckdeschel JC. Early detection and treatment of spinal cord compression. Oncology (Williston Park). 2005;19(1):81-86.

- Perron AD, Huff JS. Spinal cord disorders. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2013; 1419-1427.

- Wagner R, Jagoda A. Spinal cord syndromes. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1997;15(3):699-711.

- Sciubba DM, Gokaslan ZL. Diagnosis and management of metastatic spine disease. Surg Oncol. 2006;15(3):141-151.

- Jalloh I, Minhas P. Delays in the treatment of cauda equina syndrome due to its variable clinical features in patients presenting to the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(1):33-34.

- Korse NS, Jacobs WCH, Elzevier HW, Vieggeert-Lankamp CL. Complaints of micturition, defecation and sexual function in cauda equina syndrome due to lumbar disk herniation: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(5):1019-1029.

- Dawodu ST, Bechtel KA, Beeson MS, et al. Cauda equina and conus medullaris syndromes. Medscape Web site. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1148690-clinical. Accessed September 1, 2014.

- Glick TH, Workman TP, Gaufberg SV. Spinal cord emergencies: false reassurance from reflexes. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(10):1041-1043.

- Lewandrowski KU, McLain RF, Lieberman I, Orr D. Cord and cauda equina injury complicating elective orthopedic surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(9):1056-1059.

- Kirshblum S, Anderson K, Krassioukov A, Donovan W. Assessment and classification of traumatic spinal cord injury. In: Kirshblum S, Campagnolo DI, eds. Spinal Cord Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

- Ruckdeschel JC. Early detection and treatment of spinal cord compression. Oncology (Williston Park). 2005;19(1):81-86.

- Perron AD, Huff JS. Spinal cord disorders. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2013; 1419-1427.

- Wagner R, Jagoda A. Spinal cord syndromes. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1997;15(3):699-711.

- Sciubba DM, Gokaslan ZL. Diagnosis and management of metastatic spine disease. Surg Oncol. 2006;15(3):141-151.

- Jalloh I, Minhas P. Delays in the treatment of cauda equina syndrome due to its variable clinical features in patients presenting to the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(1):33-34.

- Korse NS, Jacobs WCH, Elzevier HW, Vieggeert-Lankamp CL. Complaints of micturition, defecation and sexual function in cauda equina syndrome due to lumbar disk herniation: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(5):1019-1029.

- Dawodu ST, Bechtel KA, Beeson MS, et al. Cauda equina and conus medullaris syndromes. Medscape Web site. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1148690-clinical. Accessed September 1, 2014.

- Glick TH, Workman TP, Gaufberg SV. Spinal cord emergencies: false reassurance from reflexes. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(10):1041-1043.