User login

Biden’s COVID-19 challenge: 100 million vaccinations in the first 100 days. It won’t be easy.

It’s in the nature of presidential candidates and new presidents to promise big things. Just months after his 1961 inauguration, President John F. Kennedy vowed to send a man to the moon by the end of the decade. That pledge was kept, but many others haven’t been, such as candidate Bill Clinton’s promise to provide universal health care and presidential hopeful George H.W. Bush’s guarantee of no new taxes.

Now, during a once-in-a-century pandemic, incoming President Joe Biden has promised to provide 100 million COVID-19 vaccinations in his first 100 days in office.

“This team will help get … at least 100 million covid vaccine shots into the arms of the American people in the first 100 days,” Biden said during a Dec. 8 news conference introducing key members of his health team.

When first asked about his pledge, the Biden team said the president-elect meant 50 million people would get their two-dose regimen. The incoming administration has since updated this plan, saying it will release vaccine doses as soon as they’re available instead of holding back some of that supply for second doses.

Either way, Biden may run into difficulty meeting that 100 million mark.

“I think it’s an attainable goal. I think it’s going to be extremely challenging,” said Claire Hannan, executive director of the Association of Immunization Managers.

While a pace of 1 million doses a day is “somewhat of an increase over what we’re already doing,” a much higher rate of vaccinations will be necessary to stem the pandemic, said Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at Kaiser Family Foundation. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.) “The Biden administration has plans to rationalize vaccine distribution, but increasing the supply quickly” could be a difficult task.

Under the Trump administration, vaccine deployment has been much slower than Biden’s plan. The rollout began on Dec. 14. Since then, 12 million shots have been given and 31 million doses have been shipped out, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s vaccine tracker.

This sluggishness has been attributed to a lack of communication between the federal government and state and local health departments, not enough funding for large-scale vaccination efforts, and confusing federal guidance on distribution of the vaccines.

The same problems could plague the Biden administration, said experts.

States still aren’t sure how much vaccine they’ll get and whether there will be a sufficient supply, said Dr. Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, which represents state public health agencies.

“We have been given little information about the amount of vaccine the states will receive in the near future and are of the impression that there may not be 1 million doses available per day in the first 100 days of the Biden administration,” said Dr. Plescia. “Or at least not in the early stages of the 100 days.”

Another challenge has been a lack of funding. Public health departments have had to start vaccination campaigns while also operating testing centers and conducting contact tracing efforts with budgets that have been critically underfunded for years.

“States have to pay for creating the systems, identifying the personnel, training, staffing, tracking people, information campaigns – all the things that go into getting a shot in someone’s arm,” said Jennifer Kates, director of global health & HIV policy at KFF. “They’re having to create an unprecedented mass vaccination program on a shaky foundation.”

The latest covid stimulus bill, signed into law in December, allocates almost $9 billion in funding to the CDC for vaccination efforts. About $4.5 billion is supposed to go to states, territories and tribal organizations, and $3 billion of that is slated to arrive soon.

But it’s not clear that level of funding can sustain mass vaccination campaigns as more groups become eligible for the vaccine.

Biden released a $1.9 trillion plan last week to address covid and the struggling economy. It includes $160 billion to create national vaccination and testing programs, but also earmarks funds for $1,400 stimulus payments to individuals, state and local government aid, extension of unemployment insurance, and financial assistance for schools to reopen safely.

Though it took Congress almost eight months to pass the last covid relief bill after Republican objections to the cost, Biden seems optimistic he’ll get some Republicans on board for his plan. But it’s not yet clear that will work.

There’s also the question of whether outgoing President Donald Trump’s impeachment trial will get in the way of Biden’s legislative priorities.

In addition, states have complained about a lack of guidance and confusing instructions on which groups should be given priority status for vaccination, an issue the Biden administration will need to address.

On Dec. 3, the CDC recommended health care personnel, residents of long-term care facilities, those 75 and older, and front-line essential workers should be immunized first. But on Jan. 12, the CDC shifted course and recommended that everyone over age 65 should be immunized. In a speech Biden gave on Jan. 15 detailing his vaccination plan, he said he would stick to the CDC’s recommendation to prioritize those over 65.

Outgoing Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar also said on Jan. 12 that states that moved their vaccine supply fastest would be prioritized in getting more shipments. It’s not known yet whether the Biden administration’s CDC will stick to this guidance. Critics have said it could make vaccine distribution less equitable.

In general, taking over with a strong vision and clear communication will be key to ramping up vaccine distribution, said Ms. Hannan.

“Everyone needs to understand what the goal is and how it’s going to work,” she said.

A challenge for Biden will be tamping expectations that the vaccine is all that is needed to end the pandemic. Across the country, covid cases are higher than ever, and in many locations officials cannot control the spread.

Public health experts said Biden must amp up efforts to increase testing across the country, as he has suggested he will do by promising to establish a national pandemic testing board.

With so much focus on vaccine distribution, it’s important that this part of the equation not be lost. Right now, “it’s completely all over the map,” said KFF’s Ms. Kates, adding that the federal government will need a “good sense” of who is and is not being tested in different areas in order to “fix” public health capacity.

Jan. 20, 2021, marks the launch of The Biden Promise Tracker, which monitors the 100 most important campaign promises of President Joseph R. Biden. Biden listed the coronavirus and a variety of other health-related issues among his top priorities. You can see the entire list – including improving the economy, responding to calls for racial justice and combating climate change – here. As part of KHN’s partnership with PolitiFact, we will follow the health-related issues and then rate them on whether the promise was achieved: Promise Kept, Promise Broken, Compromise, Stalled, In the Works or Not Yet Rated. We rate the promise not on the president’s intentions or effort, but on verifiable outcomes. PolitiFact previously tracked the promises of President Donald Trump and President Barack Obama.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

It’s in the nature of presidential candidates and new presidents to promise big things. Just months after his 1961 inauguration, President John F. Kennedy vowed to send a man to the moon by the end of the decade. That pledge was kept, but many others haven’t been, such as candidate Bill Clinton’s promise to provide universal health care and presidential hopeful George H.W. Bush’s guarantee of no new taxes.

Now, during a once-in-a-century pandemic, incoming President Joe Biden has promised to provide 100 million COVID-19 vaccinations in his first 100 days in office.

“This team will help get … at least 100 million covid vaccine shots into the arms of the American people in the first 100 days,” Biden said during a Dec. 8 news conference introducing key members of his health team.

When first asked about his pledge, the Biden team said the president-elect meant 50 million people would get their two-dose regimen. The incoming administration has since updated this plan, saying it will release vaccine doses as soon as they’re available instead of holding back some of that supply for second doses.

Either way, Biden may run into difficulty meeting that 100 million mark.

“I think it’s an attainable goal. I think it’s going to be extremely challenging,” said Claire Hannan, executive director of the Association of Immunization Managers.

While a pace of 1 million doses a day is “somewhat of an increase over what we’re already doing,” a much higher rate of vaccinations will be necessary to stem the pandemic, said Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at Kaiser Family Foundation. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.) “The Biden administration has plans to rationalize vaccine distribution, but increasing the supply quickly” could be a difficult task.

Under the Trump administration, vaccine deployment has been much slower than Biden’s plan. The rollout began on Dec. 14. Since then, 12 million shots have been given and 31 million doses have been shipped out, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s vaccine tracker.

This sluggishness has been attributed to a lack of communication between the federal government and state and local health departments, not enough funding for large-scale vaccination efforts, and confusing federal guidance on distribution of the vaccines.

The same problems could plague the Biden administration, said experts.

States still aren’t sure how much vaccine they’ll get and whether there will be a sufficient supply, said Dr. Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, which represents state public health agencies.

“We have been given little information about the amount of vaccine the states will receive in the near future and are of the impression that there may not be 1 million doses available per day in the first 100 days of the Biden administration,” said Dr. Plescia. “Or at least not in the early stages of the 100 days.”

Another challenge has been a lack of funding. Public health departments have had to start vaccination campaigns while also operating testing centers and conducting contact tracing efforts with budgets that have been critically underfunded for years.

“States have to pay for creating the systems, identifying the personnel, training, staffing, tracking people, information campaigns – all the things that go into getting a shot in someone’s arm,” said Jennifer Kates, director of global health & HIV policy at KFF. “They’re having to create an unprecedented mass vaccination program on a shaky foundation.”

The latest covid stimulus bill, signed into law in December, allocates almost $9 billion in funding to the CDC for vaccination efforts. About $4.5 billion is supposed to go to states, territories and tribal organizations, and $3 billion of that is slated to arrive soon.

But it’s not clear that level of funding can sustain mass vaccination campaigns as more groups become eligible for the vaccine.

Biden released a $1.9 trillion plan last week to address covid and the struggling economy. It includes $160 billion to create national vaccination and testing programs, but also earmarks funds for $1,400 stimulus payments to individuals, state and local government aid, extension of unemployment insurance, and financial assistance for schools to reopen safely.

Though it took Congress almost eight months to pass the last covid relief bill after Republican objections to the cost, Biden seems optimistic he’ll get some Republicans on board for his plan. But it’s not yet clear that will work.

There’s also the question of whether outgoing President Donald Trump’s impeachment trial will get in the way of Biden’s legislative priorities.

In addition, states have complained about a lack of guidance and confusing instructions on which groups should be given priority status for vaccination, an issue the Biden administration will need to address.

On Dec. 3, the CDC recommended health care personnel, residents of long-term care facilities, those 75 and older, and front-line essential workers should be immunized first. But on Jan. 12, the CDC shifted course and recommended that everyone over age 65 should be immunized. In a speech Biden gave on Jan. 15 detailing his vaccination plan, he said he would stick to the CDC’s recommendation to prioritize those over 65.

Outgoing Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar also said on Jan. 12 that states that moved their vaccine supply fastest would be prioritized in getting more shipments. It’s not known yet whether the Biden administration’s CDC will stick to this guidance. Critics have said it could make vaccine distribution less equitable.

In general, taking over with a strong vision and clear communication will be key to ramping up vaccine distribution, said Ms. Hannan.

“Everyone needs to understand what the goal is and how it’s going to work,” she said.

A challenge for Biden will be tamping expectations that the vaccine is all that is needed to end the pandemic. Across the country, covid cases are higher than ever, and in many locations officials cannot control the spread.

Public health experts said Biden must amp up efforts to increase testing across the country, as he has suggested he will do by promising to establish a national pandemic testing board.

With so much focus on vaccine distribution, it’s important that this part of the equation not be lost. Right now, “it’s completely all over the map,” said KFF’s Ms. Kates, adding that the federal government will need a “good sense” of who is and is not being tested in different areas in order to “fix” public health capacity.

Jan. 20, 2021, marks the launch of The Biden Promise Tracker, which monitors the 100 most important campaign promises of President Joseph R. Biden. Biden listed the coronavirus and a variety of other health-related issues among his top priorities. You can see the entire list – including improving the economy, responding to calls for racial justice and combating climate change – here. As part of KHN’s partnership with PolitiFact, we will follow the health-related issues and then rate them on whether the promise was achieved: Promise Kept, Promise Broken, Compromise, Stalled, In the Works or Not Yet Rated. We rate the promise not on the president’s intentions or effort, but on verifiable outcomes. PolitiFact previously tracked the promises of President Donald Trump and President Barack Obama.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

It’s in the nature of presidential candidates and new presidents to promise big things. Just months after his 1961 inauguration, President John F. Kennedy vowed to send a man to the moon by the end of the decade. That pledge was kept, but many others haven’t been, such as candidate Bill Clinton’s promise to provide universal health care and presidential hopeful George H.W. Bush’s guarantee of no new taxes.

Now, during a once-in-a-century pandemic, incoming President Joe Biden has promised to provide 100 million COVID-19 vaccinations in his first 100 days in office.

“This team will help get … at least 100 million covid vaccine shots into the arms of the American people in the first 100 days,” Biden said during a Dec. 8 news conference introducing key members of his health team.

When first asked about his pledge, the Biden team said the president-elect meant 50 million people would get their two-dose regimen. The incoming administration has since updated this plan, saying it will release vaccine doses as soon as they’re available instead of holding back some of that supply for second doses.

Either way, Biden may run into difficulty meeting that 100 million mark.

“I think it’s an attainable goal. I think it’s going to be extremely challenging,” said Claire Hannan, executive director of the Association of Immunization Managers.

While a pace of 1 million doses a day is “somewhat of an increase over what we’re already doing,” a much higher rate of vaccinations will be necessary to stem the pandemic, said Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at Kaiser Family Foundation. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.) “The Biden administration has plans to rationalize vaccine distribution, but increasing the supply quickly” could be a difficult task.

Under the Trump administration, vaccine deployment has been much slower than Biden’s plan. The rollout began on Dec. 14. Since then, 12 million shots have been given and 31 million doses have been shipped out, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s vaccine tracker.

This sluggishness has been attributed to a lack of communication between the federal government and state and local health departments, not enough funding for large-scale vaccination efforts, and confusing federal guidance on distribution of the vaccines.

The same problems could plague the Biden administration, said experts.

States still aren’t sure how much vaccine they’ll get and whether there will be a sufficient supply, said Dr. Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, which represents state public health agencies.

“We have been given little information about the amount of vaccine the states will receive in the near future and are of the impression that there may not be 1 million doses available per day in the first 100 days of the Biden administration,” said Dr. Plescia. “Or at least not in the early stages of the 100 days.”

Another challenge has been a lack of funding. Public health departments have had to start vaccination campaigns while also operating testing centers and conducting contact tracing efforts with budgets that have been critically underfunded for years.

“States have to pay for creating the systems, identifying the personnel, training, staffing, tracking people, information campaigns – all the things that go into getting a shot in someone’s arm,” said Jennifer Kates, director of global health & HIV policy at KFF. “They’re having to create an unprecedented mass vaccination program on a shaky foundation.”

The latest covid stimulus bill, signed into law in December, allocates almost $9 billion in funding to the CDC for vaccination efforts. About $4.5 billion is supposed to go to states, territories and tribal organizations, and $3 billion of that is slated to arrive soon.

But it’s not clear that level of funding can sustain mass vaccination campaigns as more groups become eligible for the vaccine.

Biden released a $1.9 trillion plan last week to address covid and the struggling economy. It includes $160 billion to create national vaccination and testing programs, but also earmarks funds for $1,400 stimulus payments to individuals, state and local government aid, extension of unemployment insurance, and financial assistance for schools to reopen safely.

Though it took Congress almost eight months to pass the last covid relief bill after Republican objections to the cost, Biden seems optimistic he’ll get some Republicans on board for his plan. But it’s not yet clear that will work.

There’s also the question of whether outgoing President Donald Trump’s impeachment trial will get in the way of Biden’s legislative priorities.

In addition, states have complained about a lack of guidance and confusing instructions on which groups should be given priority status for vaccination, an issue the Biden administration will need to address.

On Dec. 3, the CDC recommended health care personnel, residents of long-term care facilities, those 75 and older, and front-line essential workers should be immunized first. But on Jan. 12, the CDC shifted course and recommended that everyone over age 65 should be immunized. In a speech Biden gave on Jan. 15 detailing his vaccination plan, he said he would stick to the CDC’s recommendation to prioritize those over 65.

Outgoing Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar also said on Jan. 12 that states that moved their vaccine supply fastest would be prioritized in getting more shipments. It’s not known yet whether the Biden administration’s CDC will stick to this guidance. Critics have said it could make vaccine distribution less equitable.

In general, taking over with a strong vision and clear communication will be key to ramping up vaccine distribution, said Ms. Hannan.

“Everyone needs to understand what the goal is and how it’s going to work,” she said.

A challenge for Biden will be tamping expectations that the vaccine is all that is needed to end the pandemic. Across the country, covid cases are higher than ever, and in many locations officials cannot control the spread.

Public health experts said Biden must amp up efforts to increase testing across the country, as he has suggested he will do by promising to establish a national pandemic testing board.

With so much focus on vaccine distribution, it’s important that this part of the equation not be lost. Right now, “it’s completely all over the map,” said KFF’s Ms. Kates, adding that the federal government will need a “good sense” of who is and is not being tested in different areas in order to “fix” public health capacity.

Jan. 20, 2021, marks the launch of The Biden Promise Tracker, which monitors the 100 most important campaign promises of President Joseph R. Biden. Biden listed the coronavirus and a variety of other health-related issues among his top priorities. You can see the entire list – including improving the economy, responding to calls for racial justice and combating climate change – here. As part of KHN’s partnership with PolitiFact, we will follow the health-related issues and then rate them on whether the promise was achieved: Promise Kept, Promise Broken, Compromise, Stalled, In the Works or Not Yet Rated. We rate the promise not on the president’s intentions or effort, but on verifiable outcomes. PolitiFact previously tracked the promises of President Donald Trump and President Barack Obama.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

HHS will drop buprenorphine waiver rule for most physicians

Federal officials on Thursday announced a plan to largely drop the so-called X-waiver requirement for buprenorphine prescriptions for physicians in a bid to remove an administrative procedure widely seen as a barrier to opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment.

The Department of Health & Human Services unveiled new practice guidelines that include an exemption from current certification requirements. The exemption applies to physicians already registered with the Drug Enforcement Administration.

A restriction included in the new HHS policy is a limit of treating no more than 30 patients with buprenorphine for OUD at any one time. There is an exception to this limit for hospital-based physicians, such as those working in emergency departments, HHS said.

, such as buprenorphine, and does not apply to methadone. The new guidelines say the date on which they will take effect will be added after publication in the Federal Register. HHS did not immediately answer a request from this news organization for a more specific timeline.

Welcomed change

The change in prescribing rule was widely welcomed, with the American Medical Association issuing a statement endorsing the revision. The AMA and many prescribers and researchers had seen the X-waiver as a hurdle to address the nation’s opioid epidemic.

There were more than 83,000 deaths attributed to drug overdoses in the United States in the 12 months ending in June 2020. This is the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a 12-month period, HHS said in a press release, which cited data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In a tweet about the new policy, Peter Grinspoon, MD, a Boston internist and author of the memoir “Free Refills: A Doctor Confronts His Addiction,” contrasted the relative ease with which clinicians can give medicines that carry a risk for abuse with the challenge that has existed in trying to provide patients with buprenorphine.

“Absolutely insane that we need a special waiver for buprenorphine to TREAT opioid addiction, but not to prescribe oxycodone, Vicodin, etc., which can get people in trouble in the first place!!” Dr. Grinspoon tweeted.

Patrice Harris, MD, chair of the AMA’s Opioid Task Force and the organization’s immediate past president, said removing the X-waiver requirement can help lessen the stigma associated with this OUD treatment. The AMA had urged HHS to change the regulation.

“With this change, office-based physicians and physician-led teams working with patients to manage their other medical conditions can also treat them for their opioid use disorder without being subjected to a separate and burdensome regulatory regime,” Dr. Harris said in the AMA statement.

Researchers have in recent years sought to highlight what they described as missed opportunities for OUD treatment because of the need for the X-waiver.

Buprenorphine is a cost-effective treatment for opioid use disorder, which reduces the risk of injection-related infections and mortality risk, notes a study published online last month in JAMA Network Open.

However, results showed that fewer than 2% of obstetrician-gynecologists who examined women enrolled in Medicaid were trained to prescribe buprenorphine. The study, which was based on data from 31, 211 ob.gyns. who accepted Medicaid insurance, was created to quantify how many were on the list of Drug Addiction Treatment Act buprenorphine-waived clinicians.

The Drug Addiction Treatment Act has required 8 hours of training for physicians and 24 hours for nurse practitioners and physician assistants for the X-waiver needed to prescribe buprenorphine, the investigators report.

‘X the X-waiver’

Only 10% of recent family residency graduates reported being adequately trained to prescribe buprenorphine and only 7% reported actually prescribing the drug, write Kevin Fiscella, MD, University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center and colleagues in a 2018 Viewpoint article published in JAMA Psychiatry.

In the article, which was subtitled “X the X Waiver,” they called for deregulation of buprenorphine as a way of mainstreaming treatment for OUD.

“The DATA 2000 has failed – too few physicians have obtained X-waivers,” the authors write. “Regulations reinforce the stigma surrounding buprenorphine prescribers and patients who receive it while constraining access and discouraging patient engagement and retention in treatment.”

The change, announced Jan. 14, leaves in place restrictions on prescribing for clinicians other than physicians. On a call with reporters, Adm. Brett P. Giroir, MD, assistant secretary for health, suggested that federal officials should take further steps to remove hurdles to buprenorphine prescriptions.

“Many people will say this has gone too far,” Dr. Giroir said of the drive to end the X-waiver for clinicians. “But I believe more people will say this has not gone far enough.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal officials on Thursday announced a plan to largely drop the so-called X-waiver requirement for buprenorphine prescriptions for physicians in a bid to remove an administrative procedure widely seen as a barrier to opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment.

The Department of Health & Human Services unveiled new practice guidelines that include an exemption from current certification requirements. The exemption applies to physicians already registered with the Drug Enforcement Administration.

A restriction included in the new HHS policy is a limit of treating no more than 30 patients with buprenorphine for OUD at any one time. There is an exception to this limit for hospital-based physicians, such as those working in emergency departments, HHS said.

, such as buprenorphine, and does not apply to methadone. The new guidelines say the date on which they will take effect will be added after publication in the Federal Register. HHS did not immediately answer a request from this news organization for a more specific timeline.

Welcomed change

The change in prescribing rule was widely welcomed, with the American Medical Association issuing a statement endorsing the revision. The AMA and many prescribers and researchers had seen the X-waiver as a hurdle to address the nation’s opioid epidemic.

There were more than 83,000 deaths attributed to drug overdoses in the United States in the 12 months ending in June 2020. This is the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a 12-month period, HHS said in a press release, which cited data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In a tweet about the new policy, Peter Grinspoon, MD, a Boston internist and author of the memoir “Free Refills: A Doctor Confronts His Addiction,” contrasted the relative ease with which clinicians can give medicines that carry a risk for abuse with the challenge that has existed in trying to provide patients with buprenorphine.

“Absolutely insane that we need a special waiver for buprenorphine to TREAT opioid addiction, but not to prescribe oxycodone, Vicodin, etc., which can get people in trouble in the first place!!” Dr. Grinspoon tweeted.

Patrice Harris, MD, chair of the AMA’s Opioid Task Force and the organization’s immediate past president, said removing the X-waiver requirement can help lessen the stigma associated with this OUD treatment. The AMA had urged HHS to change the regulation.

“With this change, office-based physicians and physician-led teams working with patients to manage their other medical conditions can also treat them for their opioid use disorder without being subjected to a separate and burdensome regulatory regime,” Dr. Harris said in the AMA statement.

Researchers have in recent years sought to highlight what they described as missed opportunities for OUD treatment because of the need for the X-waiver.

Buprenorphine is a cost-effective treatment for opioid use disorder, which reduces the risk of injection-related infections and mortality risk, notes a study published online last month in JAMA Network Open.

However, results showed that fewer than 2% of obstetrician-gynecologists who examined women enrolled in Medicaid were trained to prescribe buprenorphine. The study, which was based on data from 31, 211 ob.gyns. who accepted Medicaid insurance, was created to quantify how many were on the list of Drug Addiction Treatment Act buprenorphine-waived clinicians.

The Drug Addiction Treatment Act has required 8 hours of training for physicians and 24 hours for nurse practitioners and physician assistants for the X-waiver needed to prescribe buprenorphine, the investigators report.

‘X the X-waiver’

Only 10% of recent family residency graduates reported being adequately trained to prescribe buprenorphine and only 7% reported actually prescribing the drug, write Kevin Fiscella, MD, University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center and colleagues in a 2018 Viewpoint article published in JAMA Psychiatry.

In the article, which was subtitled “X the X Waiver,” they called for deregulation of buprenorphine as a way of mainstreaming treatment for OUD.

“The DATA 2000 has failed – too few physicians have obtained X-waivers,” the authors write. “Regulations reinforce the stigma surrounding buprenorphine prescribers and patients who receive it while constraining access and discouraging patient engagement and retention in treatment.”

The change, announced Jan. 14, leaves in place restrictions on prescribing for clinicians other than physicians. On a call with reporters, Adm. Brett P. Giroir, MD, assistant secretary for health, suggested that federal officials should take further steps to remove hurdles to buprenorphine prescriptions.

“Many people will say this has gone too far,” Dr. Giroir said of the drive to end the X-waiver for clinicians. “But I believe more people will say this has not gone far enough.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal officials on Thursday announced a plan to largely drop the so-called X-waiver requirement for buprenorphine prescriptions for physicians in a bid to remove an administrative procedure widely seen as a barrier to opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment.

The Department of Health & Human Services unveiled new practice guidelines that include an exemption from current certification requirements. The exemption applies to physicians already registered with the Drug Enforcement Administration.

A restriction included in the new HHS policy is a limit of treating no more than 30 patients with buprenorphine for OUD at any one time. There is an exception to this limit for hospital-based physicians, such as those working in emergency departments, HHS said.

, such as buprenorphine, and does not apply to methadone. The new guidelines say the date on which they will take effect will be added after publication in the Federal Register. HHS did not immediately answer a request from this news organization for a more specific timeline.

Welcomed change

The change in prescribing rule was widely welcomed, with the American Medical Association issuing a statement endorsing the revision. The AMA and many prescribers and researchers had seen the X-waiver as a hurdle to address the nation’s opioid epidemic.

There were more than 83,000 deaths attributed to drug overdoses in the United States in the 12 months ending in June 2020. This is the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a 12-month period, HHS said in a press release, which cited data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In a tweet about the new policy, Peter Grinspoon, MD, a Boston internist and author of the memoir “Free Refills: A Doctor Confronts His Addiction,” contrasted the relative ease with which clinicians can give medicines that carry a risk for abuse with the challenge that has existed in trying to provide patients with buprenorphine.

“Absolutely insane that we need a special waiver for buprenorphine to TREAT opioid addiction, but not to prescribe oxycodone, Vicodin, etc., which can get people in trouble in the first place!!” Dr. Grinspoon tweeted.

Patrice Harris, MD, chair of the AMA’s Opioid Task Force and the organization’s immediate past president, said removing the X-waiver requirement can help lessen the stigma associated with this OUD treatment. The AMA had urged HHS to change the regulation.

“With this change, office-based physicians and physician-led teams working with patients to manage their other medical conditions can also treat them for their opioid use disorder without being subjected to a separate and burdensome regulatory regime,” Dr. Harris said in the AMA statement.

Researchers have in recent years sought to highlight what they described as missed opportunities for OUD treatment because of the need for the X-waiver.

Buprenorphine is a cost-effective treatment for opioid use disorder, which reduces the risk of injection-related infections and mortality risk, notes a study published online last month in JAMA Network Open.

However, results showed that fewer than 2% of obstetrician-gynecologists who examined women enrolled in Medicaid were trained to prescribe buprenorphine. The study, which was based on data from 31, 211 ob.gyns. who accepted Medicaid insurance, was created to quantify how many were on the list of Drug Addiction Treatment Act buprenorphine-waived clinicians.

The Drug Addiction Treatment Act has required 8 hours of training for physicians and 24 hours for nurse practitioners and physician assistants for the X-waiver needed to prescribe buprenorphine, the investigators report.

‘X the X-waiver’

Only 10% of recent family residency graduates reported being adequately trained to prescribe buprenorphine and only 7% reported actually prescribing the drug, write Kevin Fiscella, MD, University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center and colleagues in a 2018 Viewpoint article published in JAMA Psychiatry.

In the article, which was subtitled “X the X Waiver,” they called for deregulation of buprenorphine as a way of mainstreaming treatment for OUD.

“The DATA 2000 has failed – too few physicians have obtained X-waivers,” the authors write. “Regulations reinforce the stigma surrounding buprenorphine prescribers and patients who receive it while constraining access and discouraging patient engagement and retention in treatment.”

The change, announced Jan. 14, leaves in place restrictions on prescribing for clinicians other than physicians. On a call with reporters, Adm. Brett P. Giroir, MD, assistant secretary for health, suggested that federal officials should take further steps to remove hurdles to buprenorphine prescriptions.

“Many people will say this has gone too far,” Dr. Giroir said of the drive to end the X-waiver for clinicians. “But I believe more people will say this has not gone far enough.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Eliminating hepatitis by 2030: HHS releases new strategic plan

In an effort to counteract alarming trends in rising hepatitis infections, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has developed and released its Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan 2021-2025, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis infection in the United States by 2030.

An estimated 3.3 million people in the United States were chronically infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) as of 2016. In addition, the country “is currently facing unprecedented hepatitis A (HAV) outbreaks, while progress in preventing hepatitis B has stalled, and hepatitis C rates nearly tripled from 2011 to 2018,” according to the HHS.

The new plan, “A Roadmap to Elimination for the United States,” builds upon previous initiatives the HHS has made to tackle the diseases and was coordinated by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health through the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy.

The plan focuses on HAV, HBV, and HCV, which have the largest impact on the health of the nation, according to the HHS. The plan addresses populations with the highest burden of viral hepatitis based on nationwide data so that resources can be focused there to achieve the greatest impact. Persons who inject drugs are a priority population for all three hepatitis viruses. HAV efforts will also include a focus on the homeless population. HBV efforts will also focus on Asian and Pacific Islander and the Black, non-Hispanic populations, while HCV efforts will include a focus on Black, non-Hispanic people, people born during 1945-1965, people with HIV, and the American Indian/Alaska Native population.

Goal-setting

There are five main goals outlined in the plan, according to the HHS:

- Prevent new hepatitis infections.

- Improve hepatitis-related health outcomes of people with viral hepatitis.

- Reduce hepatitis-related disparities and health inequities.

- Improve hepatitis surveillance and data use.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the viral hepatitis epidemics among all partners and stakeholders.

“The United States will be a place where new viral hepatitis infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with viral hepatitis has high-quality health care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination. This vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” according to the HHS vision statement.

In an effort to counteract alarming trends in rising hepatitis infections, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has developed and released its Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan 2021-2025, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis infection in the United States by 2030.

An estimated 3.3 million people in the United States were chronically infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) as of 2016. In addition, the country “is currently facing unprecedented hepatitis A (HAV) outbreaks, while progress in preventing hepatitis B has stalled, and hepatitis C rates nearly tripled from 2011 to 2018,” according to the HHS.

The new plan, “A Roadmap to Elimination for the United States,” builds upon previous initiatives the HHS has made to tackle the diseases and was coordinated by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health through the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy.

The plan focuses on HAV, HBV, and HCV, which have the largest impact on the health of the nation, according to the HHS. The plan addresses populations with the highest burden of viral hepatitis based on nationwide data so that resources can be focused there to achieve the greatest impact. Persons who inject drugs are a priority population for all three hepatitis viruses. HAV efforts will also include a focus on the homeless population. HBV efforts will also focus on Asian and Pacific Islander and the Black, non-Hispanic populations, while HCV efforts will include a focus on Black, non-Hispanic people, people born during 1945-1965, people with HIV, and the American Indian/Alaska Native population.

Goal-setting

There are five main goals outlined in the plan, according to the HHS:

- Prevent new hepatitis infections.

- Improve hepatitis-related health outcomes of people with viral hepatitis.

- Reduce hepatitis-related disparities and health inequities.

- Improve hepatitis surveillance and data use.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the viral hepatitis epidemics among all partners and stakeholders.

“The United States will be a place where new viral hepatitis infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with viral hepatitis has high-quality health care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination. This vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” according to the HHS vision statement.

In an effort to counteract alarming trends in rising hepatitis infections, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has developed and released its Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan 2021-2025, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis infection in the United States by 2030.

An estimated 3.3 million people in the United States were chronically infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) as of 2016. In addition, the country “is currently facing unprecedented hepatitis A (HAV) outbreaks, while progress in preventing hepatitis B has stalled, and hepatitis C rates nearly tripled from 2011 to 2018,” according to the HHS.

The new plan, “A Roadmap to Elimination for the United States,” builds upon previous initiatives the HHS has made to tackle the diseases and was coordinated by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health through the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy.

The plan focuses on HAV, HBV, and HCV, which have the largest impact on the health of the nation, according to the HHS. The plan addresses populations with the highest burden of viral hepatitis based on nationwide data so that resources can be focused there to achieve the greatest impact. Persons who inject drugs are a priority population for all three hepatitis viruses. HAV efforts will also include a focus on the homeless population. HBV efforts will also focus on Asian and Pacific Islander and the Black, non-Hispanic populations, while HCV efforts will include a focus on Black, non-Hispanic people, people born during 1945-1965, people with HIV, and the American Indian/Alaska Native population.

Goal-setting

There are five main goals outlined in the plan, according to the HHS:

- Prevent new hepatitis infections.

- Improve hepatitis-related health outcomes of people with viral hepatitis.

- Reduce hepatitis-related disparities and health inequities.

- Improve hepatitis surveillance and data use.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the viral hepatitis epidemics among all partners and stakeholders.

“The United States will be a place where new viral hepatitis infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with viral hepatitis has high-quality health care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination. This vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” according to the HHS vision statement.

Pressure builds on CDC to prioritize both diabetes types for vaccine

The American Diabetes Association, along with 18 other organizations, has sent a letter to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urging them to rank people with type 1 diabetes as equally high risk for COVID-19 severity, and therefore vaccination, as those with type 2 diabetes.

On Jan. 12, the CDC recommended states vaccinate all Americans over age 65 and those with underlying health conditions that make them more vulnerable to COVID-19.

Currently, type 2 diabetes is listed among 12 conditions that place adults “at increased risk of severe illness from the virus that causes COVID-19,” with the latter defined as “hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death.”

On the other hand, the autoimmune condition type 1 diabetes is among 11 conditions the CDC says “might be at increased risk” for COVID-19, but limited data were available at the time of the last update on Dec. 23, 2020.

“States are utilizing the CDC risk classification when designing their vaccine distribution plans. This raises an obvious concern as it could result in the approximately 1.6 million with type 1 diabetes receiving the vaccination later than others with the same risk,” states the ADA letter, sent to the CDC on Jan. 13.

Representatives from the Endocrine Society, American Association of Clinical Endocrinology, Pediatric Endocrine Society, Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists, and JDRF, among others, cosigned the letter.

Newer data show those with type 1 diabetes at equally high risk

While acknowledging that “early data did not provide as much clarity about the extent to which those with type 1 diabetes are at high risk,” the ADA says newer evidence has emerged, as previously reported by this news organization, that “convincingly demonstrates that COVID-19 severity is more than tripled in individuals with type 1 diabetes.”

The letter also cites another study showing that people with type 1 diabetes “have a 3.3-fold greater risk of severe illness, are 3.9 times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19, and have a 3-fold increase in mortality compared to those without type 1 diabetes.”

Those risks, they note, are comparable to the increased risk established for those with type 2 diabetes, as shown in a third study from Scotland, published last month.

Asked for comment, CDC representative Kirsten Nordlund said in an interview, “This list is a living document that will be periodically updated by CDC, and it could rapidly change as the science evolves.”

In addition, Ms. Nordlund said, “Decisions about transitioning to subsequent phases should depend on supply; demand; equitable vaccine distribution; and local, state, or territorial context.”

“Phased vaccine recommendations are meant to be fluid and not restrictive for jurisdictions. It is not necessary to vaccinate all individuals in one phase before initiating the next phase; phases may overlap,” she noted. More information is available here.

Tennessee gives type 1 and type 2 diabetes equal priority for vaccination

Meanwhile, at least one state, Tennessee, has updated its guidance to include both types of diabetes as being priority for COVID-19 vaccination.

Vanderbilt University pediatric endocrinologist Justin M. Gregory, MD, said in an interview: “I was thrilled when our state modified its guidance on December 30th to include both type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the ‘high-risk category.’ Other states have not modified that guidance though.”

It’s unclear how this might play out on the ground, noted Dr. Gregory, who led one of the three studies demonstrating increased COVID-19 risk for people with type 1 diabetes.

“To tell you the truth, I don’t really know how individual organizations dispensing the vaccination [will handle] people who come to their facility saying they have ‘diabetes.’ Individual states set the vaccine-dispensing guidance and individual county health departments and health care systems mirror that guidance,” he said.

Thus, he added, “Although it’s possible an individual nurse may take the ‘I’ll ask you no questions, and you’ll tell me no lies’ approach if someone with type 1 diabetes says they have ‘diabetes’, websites and health department–recorded telephone messages are going to tell people with type 1 diabetes they have to wait further back in line if that is what their state’s guidance directs.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Diabetes Association, along with 18 other organizations, has sent a letter to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urging them to rank people with type 1 diabetes as equally high risk for COVID-19 severity, and therefore vaccination, as those with type 2 diabetes.

On Jan. 12, the CDC recommended states vaccinate all Americans over age 65 and those with underlying health conditions that make them more vulnerable to COVID-19.

Currently, type 2 diabetes is listed among 12 conditions that place adults “at increased risk of severe illness from the virus that causes COVID-19,” with the latter defined as “hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death.”

On the other hand, the autoimmune condition type 1 diabetes is among 11 conditions the CDC says “might be at increased risk” for COVID-19, but limited data were available at the time of the last update on Dec. 23, 2020.

“States are utilizing the CDC risk classification when designing their vaccine distribution plans. This raises an obvious concern as it could result in the approximately 1.6 million with type 1 diabetes receiving the vaccination later than others with the same risk,” states the ADA letter, sent to the CDC on Jan. 13.

Representatives from the Endocrine Society, American Association of Clinical Endocrinology, Pediatric Endocrine Society, Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists, and JDRF, among others, cosigned the letter.

Newer data show those with type 1 diabetes at equally high risk

While acknowledging that “early data did not provide as much clarity about the extent to which those with type 1 diabetes are at high risk,” the ADA says newer evidence has emerged, as previously reported by this news organization, that “convincingly demonstrates that COVID-19 severity is more than tripled in individuals with type 1 diabetes.”

The letter also cites another study showing that people with type 1 diabetes “have a 3.3-fold greater risk of severe illness, are 3.9 times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19, and have a 3-fold increase in mortality compared to those without type 1 diabetes.”

Those risks, they note, are comparable to the increased risk established for those with type 2 diabetes, as shown in a third study from Scotland, published last month.

Asked for comment, CDC representative Kirsten Nordlund said in an interview, “This list is a living document that will be periodically updated by CDC, and it could rapidly change as the science evolves.”

In addition, Ms. Nordlund said, “Decisions about transitioning to subsequent phases should depend on supply; demand; equitable vaccine distribution; and local, state, or territorial context.”

“Phased vaccine recommendations are meant to be fluid and not restrictive for jurisdictions. It is not necessary to vaccinate all individuals in one phase before initiating the next phase; phases may overlap,” she noted. More information is available here.

Tennessee gives type 1 and type 2 diabetes equal priority for vaccination

Meanwhile, at least one state, Tennessee, has updated its guidance to include both types of diabetes as being priority for COVID-19 vaccination.

Vanderbilt University pediatric endocrinologist Justin M. Gregory, MD, said in an interview: “I was thrilled when our state modified its guidance on December 30th to include both type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the ‘high-risk category.’ Other states have not modified that guidance though.”

It’s unclear how this might play out on the ground, noted Dr. Gregory, who led one of the three studies demonstrating increased COVID-19 risk for people with type 1 diabetes.

“To tell you the truth, I don’t really know how individual organizations dispensing the vaccination [will handle] people who come to their facility saying they have ‘diabetes.’ Individual states set the vaccine-dispensing guidance and individual county health departments and health care systems mirror that guidance,” he said.

Thus, he added, “Although it’s possible an individual nurse may take the ‘I’ll ask you no questions, and you’ll tell me no lies’ approach if someone with type 1 diabetes says they have ‘diabetes’, websites and health department–recorded telephone messages are going to tell people with type 1 diabetes they have to wait further back in line if that is what their state’s guidance directs.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Diabetes Association, along with 18 other organizations, has sent a letter to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urging them to rank people with type 1 diabetes as equally high risk for COVID-19 severity, and therefore vaccination, as those with type 2 diabetes.

On Jan. 12, the CDC recommended states vaccinate all Americans over age 65 and those with underlying health conditions that make them more vulnerable to COVID-19.

Currently, type 2 diabetes is listed among 12 conditions that place adults “at increased risk of severe illness from the virus that causes COVID-19,” with the latter defined as “hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death.”

On the other hand, the autoimmune condition type 1 diabetes is among 11 conditions the CDC says “might be at increased risk” for COVID-19, but limited data were available at the time of the last update on Dec. 23, 2020.

“States are utilizing the CDC risk classification when designing their vaccine distribution plans. This raises an obvious concern as it could result in the approximately 1.6 million with type 1 diabetes receiving the vaccination later than others with the same risk,” states the ADA letter, sent to the CDC on Jan. 13.

Representatives from the Endocrine Society, American Association of Clinical Endocrinology, Pediatric Endocrine Society, Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists, and JDRF, among others, cosigned the letter.

Newer data show those with type 1 diabetes at equally high risk

While acknowledging that “early data did not provide as much clarity about the extent to which those with type 1 diabetes are at high risk,” the ADA says newer evidence has emerged, as previously reported by this news organization, that “convincingly demonstrates that COVID-19 severity is more than tripled in individuals with type 1 diabetes.”

The letter also cites another study showing that people with type 1 diabetes “have a 3.3-fold greater risk of severe illness, are 3.9 times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19, and have a 3-fold increase in mortality compared to those without type 1 diabetes.”

Those risks, they note, are comparable to the increased risk established for those with type 2 diabetes, as shown in a third study from Scotland, published last month.

Asked for comment, CDC representative Kirsten Nordlund said in an interview, “This list is a living document that will be periodically updated by CDC, and it could rapidly change as the science evolves.”

In addition, Ms. Nordlund said, “Decisions about transitioning to subsequent phases should depend on supply; demand; equitable vaccine distribution; and local, state, or territorial context.”

“Phased vaccine recommendations are meant to be fluid and not restrictive for jurisdictions. It is not necessary to vaccinate all individuals in one phase before initiating the next phase; phases may overlap,” she noted. More information is available here.

Tennessee gives type 1 and type 2 diabetes equal priority for vaccination

Meanwhile, at least one state, Tennessee, has updated its guidance to include both types of diabetes as being priority for COVID-19 vaccination.

Vanderbilt University pediatric endocrinologist Justin M. Gregory, MD, said in an interview: “I was thrilled when our state modified its guidance on December 30th to include both type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the ‘high-risk category.’ Other states have not modified that guidance though.”

It’s unclear how this might play out on the ground, noted Dr. Gregory, who led one of the three studies demonstrating increased COVID-19 risk for people with type 1 diabetes.

“To tell you the truth, I don’t really know how individual organizations dispensing the vaccination [will handle] people who come to their facility saying they have ‘diabetes.’ Individual states set the vaccine-dispensing guidance and individual county health departments and health care systems mirror that guidance,” he said.

Thus, he added, “Although it’s possible an individual nurse may take the ‘I’ll ask you no questions, and you’ll tell me no lies’ approach if someone with type 1 diabetes says they have ‘diabetes’, websites and health department–recorded telephone messages are going to tell people with type 1 diabetes they have to wait further back in line if that is what their state’s guidance directs.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Feds authorize $3 billion to boost vaccine rollout

The CDC will send $3 billion to the states to boost a lagging national COVID-19 vaccination program.

The Department of Health and Human Services announced the new funding as only 30% of the more than 22 million doses of vaccine distributed in the U.S. has been injected into Americans’ arms.

Along with the $3 billion, HHS said another $19 billion is headed to states and jurisdictions to boost COVID-19 testing programs. The amount each state will receive will be determined by population.

The news comes days after President-elect Joe Biden said he planned to release all available doses of vaccine after he takes office on Jan. 20. The Trump administration has been holding back millions of doses to ensure supply of vaccine to provide the necessary second dose for those who received the first shot.

“This funding is another timely investment that will strengthen our nation’s efforts to stop the COVID-19 pandemic in America,” CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD, said in a statement. “Particularly now, it is crucial that states and communities have the resources they need to conduct testing, and to distribute and administer safe, high-quality COVID-19 vaccines safely and equitably.”

Federal officials and public health experts, however, expressed concerns this weekend about Biden’s plan.

Outgoing Trump administration officials and others said they worry that doing so will leave providers without enough second doses for people getting the two-shot vaccines.

If Biden releases all available doses and the vaccine-making process has an issue, they said, that could pose a supply risk.

“We have product that is going through QC right now – quality control – for sterility, identity check that we have tens and tens of millions of product. We always will. But batches fail. Sterility fails ... and then you don’t have a product for that second dose,” Alex Azar, secretary of health and human services, told the American Hospital Association on Jan. 8, according to CNN.

“And frankly, talking about that or encouraging that can really undermine a critical public health need, which is that people come back for their second vaccine,” he said.

One of the main roadblocks in the vaccine rollout has been administering the doses that have already been distributed. The U.S. has shipped 22.1 million doses, and 6.6 million first shots have been given, according to the latest CDC data updated Jan. 8. Mr. Azar and other federal health officials have encouraged states to use their current supply and expand vaccine access to more priority groups.

“We would be delighted to learn that jurisdictions have actually administered many more doses than they are presently reporting,” a spokesman for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services told CNN. “We are encouraging jurisdictions to expand their priority groups as needed to ensure no vaccine is sitting on the shelf after having been delivered to the jurisdiction-directed locations.”

Releasing more vaccines for first doses could create ethical concerns as well, since people getting vaccines expect to get a second dose in the proper amount of time, according to The Week. Biden’s transition team said on Jan. 8 that he won’t delay the second dose but, instead, plans to ramp up production to stay on track.

To do this well, the federal government should create a coordinated vaccine strategy that sets expectations for an around-the-clock operation and help state and local vaccination programs meet their goals, Leana Wen, MD, a professor at George Washington University, wrote in an editorial for The Washington Post.

“The Biden team’s urgency around vaccinations is commendable,” she added in a Twitter post on Jan. 11. “I’d like to see a guarantee that every 1st dose given will be followed with a timely 2nd dose. Otherwise, there are ethical concerns that could add to vaccine hesitancy.”

Biden has pledged that 100 million doses will be administered in his first 100 days in office. He has grown frustrated as concerns grow that his administration could fall short of the promise, according to Politico. His coronavirus response team has noted several challenges, including what they say is a lack of long-term planning by the Trump administration and an initial refusal to share key information.

“We’re uncovering new information each day, and we’re unearthing – of course – more work to be done,” Vivek Murthy, MD, Biden’s nominee for surgeon general, told Politico.

The team has uncovered staffing shortages, technology problems, and issues with health care insurance coverage. The incoming Biden team has developed several initiatives, such as mobile vaccination units and new federal sites to give shots. It could take weeks to get the vaccine rollout on track, the news outlet reported.

“Will this be challenging? Absolutely,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and Biden’s incoming chief medical adviser on the coronavirus, told Politico. “This is an unprecedented effort to vaccinate the entire country over a period of time that’s fighting against people dying at record numbers. To say it’s not a challenge would be unrealistic. Do I think it can be done? Yes.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The CDC will send $3 billion to the states to boost a lagging national COVID-19 vaccination program.

The Department of Health and Human Services announced the new funding as only 30% of the more than 22 million doses of vaccine distributed in the U.S. has been injected into Americans’ arms.

Along with the $3 billion, HHS said another $19 billion is headed to states and jurisdictions to boost COVID-19 testing programs. The amount each state will receive will be determined by population.

The news comes days after President-elect Joe Biden said he planned to release all available doses of vaccine after he takes office on Jan. 20. The Trump administration has been holding back millions of doses to ensure supply of vaccine to provide the necessary second dose for those who received the first shot.

“This funding is another timely investment that will strengthen our nation’s efforts to stop the COVID-19 pandemic in America,” CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD, said in a statement. “Particularly now, it is crucial that states and communities have the resources they need to conduct testing, and to distribute and administer safe, high-quality COVID-19 vaccines safely and equitably.”

Federal officials and public health experts, however, expressed concerns this weekend about Biden’s plan.

Outgoing Trump administration officials and others said they worry that doing so will leave providers without enough second doses for people getting the two-shot vaccines.

If Biden releases all available doses and the vaccine-making process has an issue, they said, that could pose a supply risk.

“We have product that is going through QC right now – quality control – for sterility, identity check that we have tens and tens of millions of product. We always will. But batches fail. Sterility fails ... and then you don’t have a product for that second dose,” Alex Azar, secretary of health and human services, told the American Hospital Association on Jan. 8, according to CNN.

“And frankly, talking about that or encouraging that can really undermine a critical public health need, which is that people come back for their second vaccine,” he said.

One of the main roadblocks in the vaccine rollout has been administering the doses that have already been distributed. The U.S. has shipped 22.1 million doses, and 6.6 million first shots have been given, according to the latest CDC data updated Jan. 8. Mr. Azar and other federal health officials have encouraged states to use their current supply and expand vaccine access to more priority groups.

“We would be delighted to learn that jurisdictions have actually administered many more doses than they are presently reporting,” a spokesman for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services told CNN. “We are encouraging jurisdictions to expand their priority groups as needed to ensure no vaccine is sitting on the shelf after having been delivered to the jurisdiction-directed locations.”

Releasing more vaccines for first doses could create ethical concerns as well, since people getting vaccines expect to get a second dose in the proper amount of time, according to The Week. Biden’s transition team said on Jan. 8 that he won’t delay the second dose but, instead, plans to ramp up production to stay on track.

To do this well, the federal government should create a coordinated vaccine strategy that sets expectations for an around-the-clock operation and help state and local vaccination programs meet their goals, Leana Wen, MD, a professor at George Washington University, wrote in an editorial for The Washington Post.

“The Biden team’s urgency around vaccinations is commendable,” she added in a Twitter post on Jan. 11. “I’d like to see a guarantee that every 1st dose given will be followed with a timely 2nd dose. Otherwise, there are ethical concerns that could add to vaccine hesitancy.”

Biden has pledged that 100 million doses will be administered in his first 100 days in office. He has grown frustrated as concerns grow that his administration could fall short of the promise, according to Politico. His coronavirus response team has noted several challenges, including what they say is a lack of long-term planning by the Trump administration and an initial refusal to share key information.

“We’re uncovering new information each day, and we’re unearthing – of course – more work to be done,” Vivek Murthy, MD, Biden’s nominee for surgeon general, told Politico.

The team has uncovered staffing shortages, technology problems, and issues with health care insurance coverage. The incoming Biden team has developed several initiatives, such as mobile vaccination units and new federal sites to give shots. It could take weeks to get the vaccine rollout on track, the news outlet reported.

“Will this be challenging? Absolutely,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and Biden’s incoming chief medical adviser on the coronavirus, told Politico. “This is an unprecedented effort to vaccinate the entire country over a period of time that’s fighting against people dying at record numbers. To say it’s not a challenge would be unrealistic. Do I think it can be done? Yes.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The CDC will send $3 billion to the states to boost a lagging national COVID-19 vaccination program.

The Department of Health and Human Services announced the new funding as only 30% of the more than 22 million doses of vaccine distributed in the U.S. has been injected into Americans’ arms.

Along with the $3 billion, HHS said another $19 billion is headed to states and jurisdictions to boost COVID-19 testing programs. The amount each state will receive will be determined by population.

The news comes days after President-elect Joe Biden said he planned to release all available doses of vaccine after he takes office on Jan. 20. The Trump administration has been holding back millions of doses to ensure supply of vaccine to provide the necessary second dose for those who received the first shot.

“This funding is another timely investment that will strengthen our nation’s efforts to stop the COVID-19 pandemic in America,” CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD, said in a statement. “Particularly now, it is crucial that states and communities have the resources they need to conduct testing, and to distribute and administer safe, high-quality COVID-19 vaccines safely and equitably.”

Federal officials and public health experts, however, expressed concerns this weekend about Biden’s plan.

Outgoing Trump administration officials and others said they worry that doing so will leave providers without enough second doses for people getting the two-shot vaccines.

If Biden releases all available doses and the vaccine-making process has an issue, they said, that could pose a supply risk.

“We have product that is going through QC right now – quality control – for sterility, identity check that we have tens and tens of millions of product. We always will. But batches fail. Sterility fails ... and then you don’t have a product for that second dose,” Alex Azar, secretary of health and human services, told the American Hospital Association on Jan. 8, according to CNN.

“And frankly, talking about that or encouraging that can really undermine a critical public health need, which is that people come back for their second vaccine,” he said.

One of the main roadblocks in the vaccine rollout has been administering the doses that have already been distributed. The U.S. has shipped 22.1 million doses, and 6.6 million first shots have been given, according to the latest CDC data updated Jan. 8. Mr. Azar and other federal health officials have encouraged states to use their current supply and expand vaccine access to more priority groups.

“We would be delighted to learn that jurisdictions have actually administered many more doses than they are presently reporting,” a spokesman for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services told CNN. “We are encouraging jurisdictions to expand their priority groups as needed to ensure no vaccine is sitting on the shelf after having been delivered to the jurisdiction-directed locations.”

Releasing more vaccines for first doses could create ethical concerns as well, since people getting vaccines expect to get a second dose in the proper amount of time, according to The Week. Biden’s transition team said on Jan. 8 that he won’t delay the second dose but, instead, plans to ramp up production to stay on track.

To do this well, the federal government should create a coordinated vaccine strategy that sets expectations for an around-the-clock operation and help state and local vaccination programs meet their goals, Leana Wen, MD, a professor at George Washington University, wrote in an editorial for The Washington Post.

“The Biden team’s urgency around vaccinations is commendable,” she added in a Twitter post on Jan. 11. “I’d like to see a guarantee that every 1st dose given will be followed with a timely 2nd dose. Otherwise, there are ethical concerns that could add to vaccine hesitancy.”

Biden has pledged that 100 million doses will be administered in his first 100 days in office. He has grown frustrated as concerns grow that his administration could fall short of the promise, according to Politico. His coronavirus response team has noted several challenges, including what they say is a lack of long-term planning by the Trump administration and an initial refusal to share key information.

“We’re uncovering new information each day, and we’re unearthing – of course – more work to be done,” Vivek Murthy, MD, Biden’s nominee for surgeon general, told Politico.

The team has uncovered staffing shortages, technology problems, and issues with health care insurance coverage. The incoming Biden team has developed several initiatives, such as mobile vaccination units and new federal sites to give shots. It could take weeks to get the vaccine rollout on track, the news outlet reported.

“Will this be challenging? Absolutely,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and Biden’s incoming chief medical adviser on the coronavirus, told Politico. “This is an unprecedented effort to vaccinate the entire country over a period of time that’s fighting against people dying at record numbers. To say it’s not a challenge would be unrealistic. Do I think it can be done? Yes.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

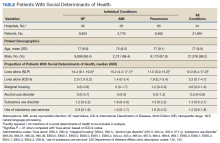

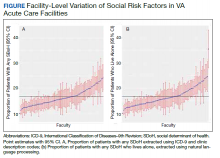

Examining the Interfacility Variation of Social Determinants of Health in the Veterans Health Administration

Social determinants of health (SDoH) are social, economic, environmental, and occupational factors that are known to influence an individual’s health care utilization and clinical outcomes.1,2 Because the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is charged to address both the medical and nonmedical needs of the veteran population, it is increasingly interested in the impact SDoH have on veteran care.3,4 To combat the adverse impact of such factors, the VHA has implemented several large-scale programs across the US that focus on prevalent SDoH, such as homelessness, substance abuse, and alcohol use disorders.5,6 While such risk factors are generally universal in their distribution, variation across regions, between urban and rural spaces, and even within cities has been shown to exist in private settings.7 Understanding such variability potentially could be helpful to US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) policymakers and leaders to better allocate funding and resources to address such issues.

Although previous work has highlighted regional and neighborhood-level variability of SDoH, no study has examined the facility-level variability of commonly encountered social risk factors within the VHA.4,8 The aim of this study was to describe the interfacility variation of 5 common SDoH known to influence health and health outcomes among a national cohort of veterans hospitalized for common medical issues by using administrative data.

Methods

We used a national cohort of veterans aged ≥ 65 years who were hospitalized at a VHA acute care facility with a primary discharge diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), or pneumonia in 2012. These conditions were chosen because they are publicly reported and frequently used for interfacility comparison.

Using the International Classification of Diseases–9th Revision (ICD-9) and VHA clinical stop codes, we calculated the median documented proportion of patients with any of the following 5 SDoH: lived alone, marginal housing, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, and use of substance use services for patients presenting with HF, MI, and pneumonia (Table). These SDoH were chosen because they are intervenable risk factors for which the VHA has several programs (eg, homeless outreach, substance abuse, and tobacco cessation). To examine the variability of these SDoH across VHA facilities, we determined the number of hospitals that had a sufficient number of admissions (≥ 50) to be included in the analyses. We then examined the administratively documented, facility-level variation in the proportion of individuals with any of the 5 SDoH administrative codes and examined the distribution of their use across all qualifying facilities.