User login

Closing the racial gap in minimally invasive gyn hysterectomy and myomectomy

The historical mistreatment of Black bodies in gynecologic care has bled into present day inequities—from surgeries performed on enslaved Black women and sterilization of low-income Black women under federally funded programs, to higher rates of adverse health-related outcomes among Black women compared with their non-Black counterparts.1-3 Not only is the foundation of gynecology imperfect, so too is its current-day structure.

It is not enough to identify and describe racial inequities in health care; action plans to provide equitable care are called for. In this report, we aim to 1) contextualize the data on disparities in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, specifically hysterectomy and myomectomy candidates and postsurgical outcomes, and 2) provide recommendations to close racial gaps in gynecologic treatment for more equitable experiences for minority women.

Black women and uterine fibroids

Uterine leiomyomas, or fibroids, are not only the most common benign pelvic tumor but they also cause a significant medical and financial burden in the United States, with estimated direct costs of $4.1 ̶ 9.4 billion.4 Fibroids can affect fertility and cause pain, bulk symptoms, heavy bleeding, anemia requiring blood transfusion, and poor pregnancy outcomes. The burden of disease for uterine fibroids is greatest for Black women.

The incidence of fibroids is 2 to 3 times higher in Black women compared with White women.5 According to ultrasound-based studies, the prevalence of fibroids among women aged 18 to 30 years was 26% among Black and 7% among White asymptomatic women.6 Earlier onset and more severe symptoms mean that there is a larger potential for impact on fertility for Black women. This coupled with the historical context of mistreatment of Black bodies makes the need for personalized medicine and culturally sensitive care critical.

Inequitable management of uterine fibroids

Although tumor size, location, and patient risk factors are used to determine the best treatment approach, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines suggest that the use of alternative treatments to surgery should be first-line management instead of hysterectomy for most benign conditions.9 Conservative management will often help alleviate symptoms, slow the growth of fibroid(s), or bridge women to menopause, and treatment options include hormonal contraception, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, hysteroscopic resection, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound, and myomectomy.

The rate of conservative management prior to hysterectomy varies by setting, reflecting potential bias in treatment decisions. Some medical settings have reported a 29% alternative management rate prior to hysterectomy, while others report much higher rates.10 A study using patient data from Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) showed that, within a large, diverse, and integrated health care system, more than 80% of patients received alternative treatments before undergoing hysterectomy; for those with symptomatic leiomyomas, 74.1% used alternative treatments prior to hysterectomy, and in logistic regression there was not a difference by race.11 Nationally, Black women are more likely to have hysterectomy or myomectomy compared with a nonsurgical uterine-sparing therapy.12,13

With about 600,000 cases per year within the United States, the hysterectomy is the most frequently performed benign gynecologic surgery.14 The most common indication is for “symptomatic fibroid uterus.” The approach to decision making for route of hysterectomy involves multiple patient and surgeon factors, including history of vaginal delivery, body mass index, history of previous surgery, uterine size, informed patient preference, and surgeon volume.15-17 ACOG recommends a minimally invasive hysterectomy (MIH) whenever feasible given its benefits in postoperative pain, recovery time, and blood loss. Myomectomy, particularly among women in their reproductive years desiring management of leiomyomas, is a uterine-sparing procedure versus hysterectomy. Minimally invasive myomectomy (MIM), compared with an open abdominal route, provides for lower drop in hemoglobin levels, shorter hospital stay, less adhesion formation, and decreased postoperative pain.18

Racial variations in hysterectomy rates persist overall and according to hysterectomy type. Black women are 2 to 3 times more likely to undergo hysterectomy for leiomyomas than other racial groups.19 These differences in rates have been shown to persist even when burden of disease is the same. One study found that Black women had increased odds of hysterectomy compared with their White counterparts even when there was no difference in mean fibroid volume by race,20 calling into question provider bias. Even in a universal insurance setting, Black patients have been found to have higher rates of open hysterectomies.21 Previous studies found that, despite growing frequency of laparoscopic and robotic-assisted hysterectomies, patients of a minority race had decreased odds of undergoing a MIH compared with their White counterparts.22

While little data exist on route of myomectomy by race, a recent study found minority women were more likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy compared with White women; Black women were twice as likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7–2.0), Asian American women were more than twice as likely (aOR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.8–2.8), and Hispanic American women were 50% more likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy (aOR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2–1.9) when compared with White women.23 These differences remained after controlling for potential confounders, and there appeared to be an interaction between race and fibroid weight such that racial bias alone may not explain the differences.

Finally, Black women have higher perioperative complication rates compared with non-Black women. Postoperative complications including blood transfusion after myomectomy have been shown to be twice as high among Black women compared with White women. However, once uterine size, comorbidities, and fibroid number were controlled, race was not associated with higher complications. Black women, compared with White women, have been found to have 50% increased odds of morbidity after an abdominal myomectomy.24

Continue to: How to ensure that BIPOC women get the best management...

How to ensure that BIPOC women get the best management

Eliminating disparities and providing equitable and patient-centered care for Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) women will require research, education, training, and targeted quality improvement initiatives.

Research into fibroids and comparative treatment outcomes

Uterine fibroids, despite their major public health impact, remain understudied. With Black women carrying the highest fibroid prevalence and severity burden, especially in their childbearing years, it is imperative that research efforts be focused on outcomes by race and ethnicity. Given the significant economic impact of fibroids, more efforts should be directed toward primary prevention of fibroid formation as well as secondary prevention and limitation of fibroid growth by affordable, effective, and safe means. For example, Bratka and colleagues researched the role of vitamin D in inhibiting growth of leiomyoma cells in animal models.25 Other innovative forms of management under investigation include aromatase inhibitors, green tea, cabergoline, elagolix, paricalcitol, and epigallocatechin gallate.26 Considerations such as stress, diet, and environmental risk factors have yet to be investigated in large studies.

Research contributing to evidence-based guidelines that address the needs of different patient populations affected by uterine fibroids is critical.8 Additionally, research conducted by Black women about Black women should be prioritized. In March 2021, the Stephanie Tubbs Jones Uterine Fibroid Research and Education Act of 2021 was introduced to fund $150 million in research supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This is an opportunity to develop a research database to inform evidence-based culturally informed care regarding fertility counseling, medical management, and optimal surgical approach, as well as to award funding to minority researchers. There are disparities in distribution of funds from the NIH to minority researchers. Under-represented minorities are awarded fewer NIH grants compared with their counterparts despite initiatives to increase funding. Furthermore, in 2011, Black applicants for NIH funding were two-thirds as likely as White applicants to receive grants from 2000 ̶ 2006, even when accounting for publication record and training.27 Funding BIPOC researchers fuels diversity-driven investigation and can be useful in the charge to increase fibroid research.

Education and training: Changing the work force

Achieving equity requires change in provider work force. In a study of trends across multiple specialties including obstetrics and gynecology, Blacks and Latinx are more under-represented in 2016 than in 1990 across all specialties except for Black women in obstetrics and gynecology.28 It is well documented that under-represented minorities are more likely to engage in practice, research, service, and mentorship activities aligned with their identity.29 As a higher proportion of under-represented minority obstetricians and gynecologists practice in medically underserved areas,30 this presents a unique opportunity for gynecologists to improve care for and increase research involvement among BIPOC women.

Increasing BIPOC representation in medical and health care institutions and practices is not enough, however, to achieve health equity. Data from the Association of American Medical Colleges demonstrate that between 1978 and 2017 the total number of full-time obstetrics and gynecology faculty rose nearly fourfold from 1,688 to 6,347; however, the greatest rise in proportion of faculty who were nontenured was among women who were under-represented minorities.31 Additionally, there are disparities in wage by race even after controlling for hours worked and state of residence.32 Medical and academic centers and health care institutions and practices should proactively and systematically engage in the recruitment and retention of under-represented minority physicians and people in leadership roles. This will involve creating safe and inclusive work environments, with equal pay and promotion structures.

Quality initiatives to address provider bias

Provider bias should be addressed in clinical decision making and counseling of patients. Studies focused on ultrasonography have shown an estimated cumulative incidence of fibroids by age 50 of greater than 80% for Black women and nearly 70% for White women.5 Due to the prevalence and burden of fibroids among Black women there may be a provider bias in approach to management. Addressing this bias requires quality improvement efforts and investigation into patient and provider factors in management of fibroids. Black women have been a vulnerable population in medicine due to instances of mistreatment, and often times mistrust can play a role in how a patient views his or her care decisions. A patient-centered strategy allows patient factors such as age, uterine size, and cultural background to be considered such that a provider can tailor an approach that is best for the patient. Previous minority women focus groups have demonstrated that women have a strong desire for elective treatment;33 therefore, providers should listen openly to patients about their values and their perspectives on how fibroids affect their lives. Provider bias toward surgical volume, incentive for surgery, and implicit bias need to be addressed at every institution to work toward equitable and cost-effective care.

Integrated health care systems like Southern and Northern California Permanente Medical Group, using quality initiatives, have increased their minimally invasive surgery rates. Southern California Permanente Medical Group reached a 78% rate of MIH in a system of more than 350 surgeons performing benign indication hysterectomies as reported in 2011.34 Similarly, a study within KPNC, an institution with an MIH rate greater than 95%,35 found that racial disparities in route of MIH were eliminated through a quality improvement initiative described in detail in 2018 (FIGURE and TABLE).36

Conclusions

There are recognized successes in the gynecology field’s efforts to address racial disparities. Prior studies provide insight into opportunities to improve care in medical management of leiomyomas, minimally invasive route of hysterectomy and myomectomy, postsurgical outcomes, and institutional leadership. Particularly, when systemwide approaches are taken in the delivery of health care it is possible to significantly diminish racial disparities in gynecology.35 Much work remains to be done for our health care systems to provide equitable care.

- Ojanuga D. The medical ethics of the ‘father of gynaecology,’ Dr J Marion Sims. J Med Ethics. 1993;19:28-31. doi: 10.1136/jme.19.1.28.

- Borrero S, Zite N, Creinin MD. Federally funded sterilization: time to rethink policy? Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1822-1825.

- Eaglehouse YL, Georg MW, Shriver CD, et al. Racial differences in time to breast cancer surgery and overall survival in the US Military Health System. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:e185113. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5113.

- Soliman AM, Yang H, Du EX, et al. The direct and indirect costs of uterine fibroid tumors: a systematic review of the literature between 2000 and 2013. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:141-160.

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

- Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:967-973. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00534-6.

- Styer AK, Rueda BR. The epidemiology and genetics of uterine leiomyoma. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;34:3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.11.018.

- Al-Hendy A, Myers ER, Stewart E. Uterine fibroids: burden and unmet medical need. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35:473-480. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607264.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin. Alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387-400.

- Corona LE, Swenson CW, Sheetz KH, et al. Use of other treatments before hysterectomy for benign conditions in a statewide hospital collaborative. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:304.e1-e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.031.

- Nguyen NT, Merchant M, Ritterman Weintraub ML, et al. Alternative treatment utilization before hysterectomy for benign gynecologic conditions at a large integrated health system. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:847-855. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.08.013.

- Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Jacoby VL, Myers ER. Disparities in fibroid incidence, prognosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:81-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2016.11.007.

- Borah BJ, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Myers ER, et al. Association between patient characteristics and treatment procedure among patients with uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:67-77.

- Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000-2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:34.e1-e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.039.

- Bardens D, Solomayer E, Baum S, et al. The impact of the body mass index (BMI) on laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:803-807. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-3050-2.

- Seracchioli R, Venturoli S, Vianello F, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy in the presence of a large uterus. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:333-338. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60413.

- Boyd LR, Novetsky AP, Curtin JP. Effect of surgical volume on route of hysterectomy and short-term morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:909-915. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f395d9.

- Jin C, Hu Y, Chen XC, et al. Laparoscopic versus open myomectomy—a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:14-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.03.009.

- Wechter ME, Stewart EA, Myers ER, et al. Leiomyoma-related hospitalization and surgery: prevalence and predicted growth based on population trends. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:492.e1-e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.008.

- Bower JK, Schreiner PJ, Sternfeld B, et al. Black-White differences in hysterectomy prevalence: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:300-307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.133702.

- Ranjit A, Sharma M, Romano A, et al. Does universal insurance mitigate racial differences in minimally invasive hysterectomy? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2017.03.016.

- Pollack LM, Olsen MA, Gehlert SJ, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities/differences in hysterectomy route in women likely eligible for minimally invasive surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1167-1177.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2019.09.003.

- Stentz NC, Cooney LG, Sammel MD, et al. Association of patient race with surgical practice and perioperative morbidity after myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:291-297. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002738.

- Roth TM, Gustilo-Ashby T, Barber MD, et al. Effects of race and clinical factors on short-term outcomes of abdominal myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(5 pt 1):881-884. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00015-2.

- Bratka S, Diamond JS, Al-Hendy A, et al. The role of vitamin D in uterine fibroid biology. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:698-706. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.05.031.

- Ciebiera M, Łukaszuk K, Męczekalski B, et al. Alternative oral agents in prophylaxis and therapy of uterine fibroids—an up-to-date review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2586. doi:10.3390/ijms18122586.

- Hayden EC. Racial bias haunts NIH funding. Nature. 2015;527:145.

- Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207274.

- Sánchez JP, Poll-Hunter N, Stern N, et al. Balancing two cultures: American Indian/Alaska Native medical students’ perceptions of academic medicine careers. J Community Health. 2016;41:871-880.

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, et al. Racial and ethnic differences between obstetrician-gynecologists and other adult medical specialists. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:148-152. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001184.

- Esters D, Xierali IM, Nivet MA, et al. The rise of nontenured faculty in obstetrics and gynecology by sex and underrepresented in medicine status. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134 suppl 1:34S-39S. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003484.

- Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB. Differences in incomes of physicians in the United States by race and sex: observational study. BMJ. 2016;I2923. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2923.

- Groff JY, Mullen PD, Byrd T, et al. Decision making, beliefs, and attitudes toward hysterectomy: a focus group study with medically underserved women in Texas. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9 suppl 2:S39-50. doi: 10.1089/152460900318759.

- Andryjowicz E, Wray T. Regional expansion of minimally invasive surgery for hysterectomy: implementation and methodology in a large multispecialty group. Perm J. 2011;15:42-46.

- Zaritsky E, Ojo A, Tucker LY, et al. Racial disparities in route of hysterectomy for benign indications within an integrated health care system. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1917004. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.17004.

- Abel MK, Kho KA, Walter A, et al. Measuring quality in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery: what, how, and why? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:321-326. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.11.013.

The historical mistreatment of Black bodies in gynecologic care has bled into present day inequities—from surgeries performed on enslaved Black women and sterilization of low-income Black women under federally funded programs, to higher rates of adverse health-related outcomes among Black women compared with their non-Black counterparts.1-3 Not only is the foundation of gynecology imperfect, so too is its current-day structure.

It is not enough to identify and describe racial inequities in health care; action plans to provide equitable care are called for. In this report, we aim to 1) contextualize the data on disparities in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, specifically hysterectomy and myomectomy candidates and postsurgical outcomes, and 2) provide recommendations to close racial gaps in gynecologic treatment for more equitable experiences for minority women.

Black women and uterine fibroids

Uterine leiomyomas, or fibroids, are not only the most common benign pelvic tumor but they also cause a significant medical and financial burden in the United States, with estimated direct costs of $4.1 ̶ 9.4 billion.4 Fibroids can affect fertility and cause pain, bulk symptoms, heavy bleeding, anemia requiring blood transfusion, and poor pregnancy outcomes. The burden of disease for uterine fibroids is greatest for Black women.

The incidence of fibroids is 2 to 3 times higher in Black women compared with White women.5 According to ultrasound-based studies, the prevalence of fibroids among women aged 18 to 30 years was 26% among Black and 7% among White asymptomatic women.6 Earlier onset and more severe symptoms mean that there is a larger potential for impact on fertility for Black women. This coupled with the historical context of mistreatment of Black bodies makes the need for personalized medicine and culturally sensitive care critical.

Inequitable management of uterine fibroids

Although tumor size, location, and patient risk factors are used to determine the best treatment approach, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines suggest that the use of alternative treatments to surgery should be first-line management instead of hysterectomy for most benign conditions.9 Conservative management will often help alleviate symptoms, slow the growth of fibroid(s), or bridge women to menopause, and treatment options include hormonal contraception, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, hysteroscopic resection, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound, and myomectomy.

The rate of conservative management prior to hysterectomy varies by setting, reflecting potential bias in treatment decisions. Some medical settings have reported a 29% alternative management rate prior to hysterectomy, while others report much higher rates.10 A study using patient data from Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) showed that, within a large, diverse, and integrated health care system, more than 80% of patients received alternative treatments before undergoing hysterectomy; for those with symptomatic leiomyomas, 74.1% used alternative treatments prior to hysterectomy, and in logistic regression there was not a difference by race.11 Nationally, Black women are more likely to have hysterectomy or myomectomy compared with a nonsurgical uterine-sparing therapy.12,13

With about 600,000 cases per year within the United States, the hysterectomy is the most frequently performed benign gynecologic surgery.14 The most common indication is for “symptomatic fibroid uterus.” The approach to decision making for route of hysterectomy involves multiple patient and surgeon factors, including history of vaginal delivery, body mass index, history of previous surgery, uterine size, informed patient preference, and surgeon volume.15-17 ACOG recommends a minimally invasive hysterectomy (MIH) whenever feasible given its benefits in postoperative pain, recovery time, and blood loss. Myomectomy, particularly among women in their reproductive years desiring management of leiomyomas, is a uterine-sparing procedure versus hysterectomy. Minimally invasive myomectomy (MIM), compared with an open abdominal route, provides for lower drop in hemoglobin levels, shorter hospital stay, less adhesion formation, and decreased postoperative pain.18

Racial variations in hysterectomy rates persist overall and according to hysterectomy type. Black women are 2 to 3 times more likely to undergo hysterectomy for leiomyomas than other racial groups.19 These differences in rates have been shown to persist even when burden of disease is the same. One study found that Black women had increased odds of hysterectomy compared with their White counterparts even when there was no difference in mean fibroid volume by race,20 calling into question provider bias. Even in a universal insurance setting, Black patients have been found to have higher rates of open hysterectomies.21 Previous studies found that, despite growing frequency of laparoscopic and robotic-assisted hysterectomies, patients of a minority race had decreased odds of undergoing a MIH compared with their White counterparts.22

While little data exist on route of myomectomy by race, a recent study found minority women were more likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy compared with White women; Black women were twice as likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7–2.0), Asian American women were more than twice as likely (aOR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.8–2.8), and Hispanic American women were 50% more likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy (aOR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2–1.9) when compared with White women.23 These differences remained after controlling for potential confounders, and there appeared to be an interaction between race and fibroid weight such that racial bias alone may not explain the differences.

Finally, Black women have higher perioperative complication rates compared with non-Black women. Postoperative complications including blood transfusion after myomectomy have been shown to be twice as high among Black women compared with White women. However, once uterine size, comorbidities, and fibroid number were controlled, race was not associated with higher complications. Black women, compared with White women, have been found to have 50% increased odds of morbidity after an abdominal myomectomy.24

Continue to: How to ensure that BIPOC women get the best management...

How to ensure that BIPOC women get the best management

Eliminating disparities and providing equitable and patient-centered care for Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) women will require research, education, training, and targeted quality improvement initiatives.

Research into fibroids and comparative treatment outcomes

Uterine fibroids, despite their major public health impact, remain understudied. With Black women carrying the highest fibroid prevalence and severity burden, especially in their childbearing years, it is imperative that research efforts be focused on outcomes by race and ethnicity. Given the significant economic impact of fibroids, more efforts should be directed toward primary prevention of fibroid formation as well as secondary prevention and limitation of fibroid growth by affordable, effective, and safe means. For example, Bratka and colleagues researched the role of vitamin D in inhibiting growth of leiomyoma cells in animal models.25 Other innovative forms of management under investigation include aromatase inhibitors, green tea, cabergoline, elagolix, paricalcitol, and epigallocatechin gallate.26 Considerations such as stress, diet, and environmental risk factors have yet to be investigated in large studies.

Research contributing to evidence-based guidelines that address the needs of different patient populations affected by uterine fibroids is critical.8 Additionally, research conducted by Black women about Black women should be prioritized. In March 2021, the Stephanie Tubbs Jones Uterine Fibroid Research and Education Act of 2021 was introduced to fund $150 million in research supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This is an opportunity to develop a research database to inform evidence-based culturally informed care regarding fertility counseling, medical management, and optimal surgical approach, as well as to award funding to minority researchers. There are disparities in distribution of funds from the NIH to minority researchers. Under-represented minorities are awarded fewer NIH grants compared with their counterparts despite initiatives to increase funding. Furthermore, in 2011, Black applicants for NIH funding were two-thirds as likely as White applicants to receive grants from 2000 ̶ 2006, even when accounting for publication record and training.27 Funding BIPOC researchers fuels diversity-driven investigation and can be useful in the charge to increase fibroid research.

Education and training: Changing the work force

Achieving equity requires change in provider work force. In a study of trends across multiple specialties including obstetrics and gynecology, Blacks and Latinx are more under-represented in 2016 than in 1990 across all specialties except for Black women in obstetrics and gynecology.28 It is well documented that under-represented minorities are more likely to engage in practice, research, service, and mentorship activities aligned with their identity.29 As a higher proportion of under-represented minority obstetricians and gynecologists practice in medically underserved areas,30 this presents a unique opportunity for gynecologists to improve care for and increase research involvement among BIPOC women.

Increasing BIPOC representation in medical and health care institutions and practices is not enough, however, to achieve health equity. Data from the Association of American Medical Colleges demonstrate that between 1978 and 2017 the total number of full-time obstetrics and gynecology faculty rose nearly fourfold from 1,688 to 6,347; however, the greatest rise in proportion of faculty who were nontenured was among women who were under-represented minorities.31 Additionally, there are disparities in wage by race even after controlling for hours worked and state of residence.32 Medical and academic centers and health care institutions and practices should proactively and systematically engage in the recruitment and retention of under-represented minority physicians and people in leadership roles. This will involve creating safe and inclusive work environments, with equal pay and promotion structures.

Quality initiatives to address provider bias

Provider bias should be addressed in clinical decision making and counseling of patients. Studies focused on ultrasonography have shown an estimated cumulative incidence of fibroids by age 50 of greater than 80% for Black women and nearly 70% for White women.5 Due to the prevalence and burden of fibroids among Black women there may be a provider bias in approach to management. Addressing this bias requires quality improvement efforts and investigation into patient and provider factors in management of fibroids. Black women have been a vulnerable population in medicine due to instances of mistreatment, and often times mistrust can play a role in how a patient views his or her care decisions. A patient-centered strategy allows patient factors such as age, uterine size, and cultural background to be considered such that a provider can tailor an approach that is best for the patient. Previous minority women focus groups have demonstrated that women have a strong desire for elective treatment;33 therefore, providers should listen openly to patients about their values and their perspectives on how fibroids affect their lives. Provider bias toward surgical volume, incentive for surgery, and implicit bias need to be addressed at every institution to work toward equitable and cost-effective care.

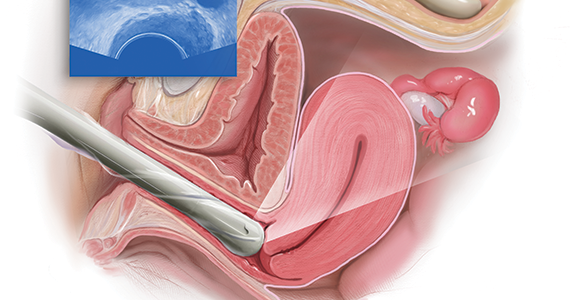

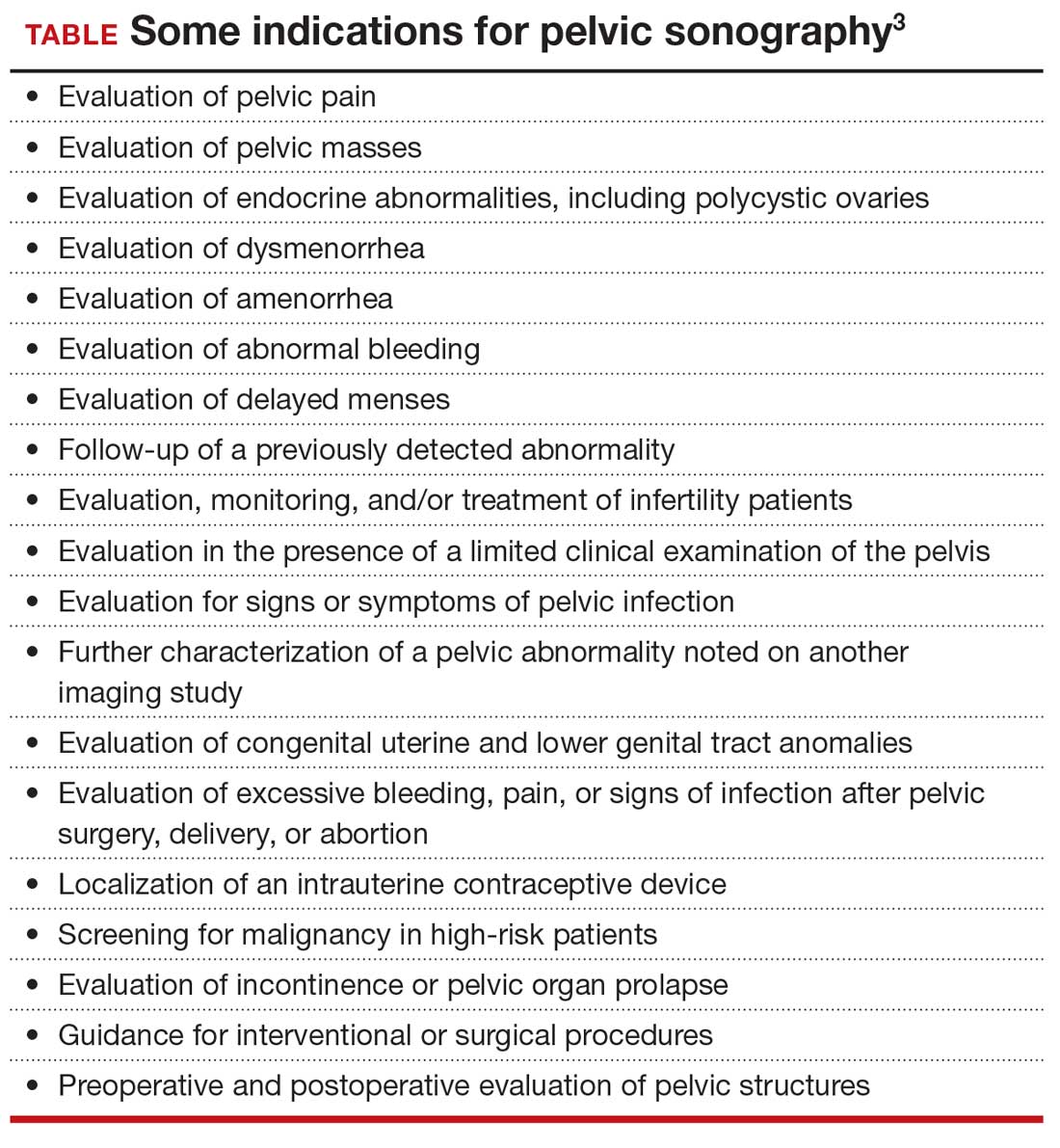

Integrated health care systems like Southern and Northern California Permanente Medical Group, using quality initiatives, have increased their minimally invasive surgery rates. Southern California Permanente Medical Group reached a 78% rate of MIH in a system of more than 350 surgeons performing benign indication hysterectomies as reported in 2011.34 Similarly, a study within KPNC, an institution with an MIH rate greater than 95%,35 found that racial disparities in route of MIH were eliminated through a quality improvement initiative described in detail in 2018 (FIGURE and TABLE).36

Conclusions

There are recognized successes in the gynecology field’s efforts to address racial disparities. Prior studies provide insight into opportunities to improve care in medical management of leiomyomas, minimally invasive route of hysterectomy and myomectomy, postsurgical outcomes, and institutional leadership. Particularly, when systemwide approaches are taken in the delivery of health care it is possible to significantly diminish racial disparities in gynecology.35 Much work remains to be done for our health care systems to provide equitable care.

The historical mistreatment of Black bodies in gynecologic care has bled into present day inequities—from surgeries performed on enslaved Black women and sterilization of low-income Black women under federally funded programs, to higher rates of adverse health-related outcomes among Black women compared with their non-Black counterparts.1-3 Not only is the foundation of gynecology imperfect, so too is its current-day structure.

It is not enough to identify and describe racial inequities in health care; action plans to provide equitable care are called for. In this report, we aim to 1) contextualize the data on disparities in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, specifically hysterectomy and myomectomy candidates and postsurgical outcomes, and 2) provide recommendations to close racial gaps in gynecologic treatment for more equitable experiences for minority women.

Black women and uterine fibroids

Uterine leiomyomas, or fibroids, are not only the most common benign pelvic tumor but they also cause a significant medical and financial burden in the United States, with estimated direct costs of $4.1 ̶ 9.4 billion.4 Fibroids can affect fertility and cause pain, bulk symptoms, heavy bleeding, anemia requiring blood transfusion, and poor pregnancy outcomes. The burden of disease for uterine fibroids is greatest for Black women.

The incidence of fibroids is 2 to 3 times higher in Black women compared with White women.5 According to ultrasound-based studies, the prevalence of fibroids among women aged 18 to 30 years was 26% among Black and 7% among White asymptomatic women.6 Earlier onset and more severe symptoms mean that there is a larger potential for impact on fertility for Black women. This coupled with the historical context of mistreatment of Black bodies makes the need for personalized medicine and culturally sensitive care critical.

Inequitable management of uterine fibroids

Although tumor size, location, and patient risk factors are used to determine the best treatment approach, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines suggest that the use of alternative treatments to surgery should be first-line management instead of hysterectomy for most benign conditions.9 Conservative management will often help alleviate symptoms, slow the growth of fibroid(s), or bridge women to menopause, and treatment options include hormonal contraception, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, hysteroscopic resection, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound, and myomectomy.

The rate of conservative management prior to hysterectomy varies by setting, reflecting potential bias in treatment decisions. Some medical settings have reported a 29% alternative management rate prior to hysterectomy, while others report much higher rates.10 A study using patient data from Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) showed that, within a large, diverse, and integrated health care system, more than 80% of patients received alternative treatments before undergoing hysterectomy; for those with symptomatic leiomyomas, 74.1% used alternative treatments prior to hysterectomy, and in logistic regression there was not a difference by race.11 Nationally, Black women are more likely to have hysterectomy or myomectomy compared with a nonsurgical uterine-sparing therapy.12,13

With about 600,000 cases per year within the United States, the hysterectomy is the most frequently performed benign gynecologic surgery.14 The most common indication is for “symptomatic fibroid uterus.” The approach to decision making for route of hysterectomy involves multiple patient and surgeon factors, including history of vaginal delivery, body mass index, history of previous surgery, uterine size, informed patient preference, and surgeon volume.15-17 ACOG recommends a minimally invasive hysterectomy (MIH) whenever feasible given its benefits in postoperative pain, recovery time, and blood loss. Myomectomy, particularly among women in their reproductive years desiring management of leiomyomas, is a uterine-sparing procedure versus hysterectomy. Minimally invasive myomectomy (MIM), compared with an open abdominal route, provides for lower drop in hemoglobin levels, shorter hospital stay, less adhesion formation, and decreased postoperative pain.18

Racial variations in hysterectomy rates persist overall and according to hysterectomy type. Black women are 2 to 3 times more likely to undergo hysterectomy for leiomyomas than other racial groups.19 These differences in rates have been shown to persist even when burden of disease is the same. One study found that Black women had increased odds of hysterectomy compared with their White counterparts even when there was no difference in mean fibroid volume by race,20 calling into question provider bias. Even in a universal insurance setting, Black patients have been found to have higher rates of open hysterectomies.21 Previous studies found that, despite growing frequency of laparoscopic and robotic-assisted hysterectomies, patients of a minority race had decreased odds of undergoing a MIH compared with their White counterparts.22

While little data exist on route of myomectomy by race, a recent study found minority women were more likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy compared with White women; Black women were twice as likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.7–2.0), Asian American women were more than twice as likely (aOR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.8–2.8), and Hispanic American women were 50% more likely to undergo abdominal myomectomy (aOR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2–1.9) when compared with White women.23 These differences remained after controlling for potential confounders, and there appeared to be an interaction between race and fibroid weight such that racial bias alone may not explain the differences.

Finally, Black women have higher perioperative complication rates compared with non-Black women. Postoperative complications including blood transfusion after myomectomy have been shown to be twice as high among Black women compared with White women. However, once uterine size, comorbidities, and fibroid number were controlled, race was not associated with higher complications. Black women, compared with White women, have been found to have 50% increased odds of morbidity after an abdominal myomectomy.24

Continue to: How to ensure that BIPOC women get the best management...

How to ensure that BIPOC women get the best management

Eliminating disparities and providing equitable and patient-centered care for Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) women will require research, education, training, and targeted quality improvement initiatives.

Research into fibroids and comparative treatment outcomes

Uterine fibroids, despite their major public health impact, remain understudied. With Black women carrying the highest fibroid prevalence and severity burden, especially in their childbearing years, it is imperative that research efforts be focused on outcomes by race and ethnicity. Given the significant economic impact of fibroids, more efforts should be directed toward primary prevention of fibroid formation as well as secondary prevention and limitation of fibroid growth by affordable, effective, and safe means. For example, Bratka and colleagues researched the role of vitamin D in inhibiting growth of leiomyoma cells in animal models.25 Other innovative forms of management under investigation include aromatase inhibitors, green tea, cabergoline, elagolix, paricalcitol, and epigallocatechin gallate.26 Considerations such as stress, diet, and environmental risk factors have yet to be investigated in large studies.

Research contributing to evidence-based guidelines that address the needs of different patient populations affected by uterine fibroids is critical.8 Additionally, research conducted by Black women about Black women should be prioritized. In March 2021, the Stephanie Tubbs Jones Uterine Fibroid Research and Education Act of 2021 was introduced to fund $150 million in research supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This is an opportunity to develop a research database to inform evidence-based culturally informed care regarding fertility counseling, medical management, and optimal surgical approach, as well as to award funding to minority researchers. There are disparities in distribution of funds from the NIH to minority researchers. Under-represented minorities are awarded fewer NIH grants compared with their counterparts despite initiatives to increase funding. Furthermore, in 2011, Black applicants for NIH funding were two-thirds as likely as White applicants to receive grants from 2000 ̶ 2006, even when accounting for publication record and training.27 Funding BIPOC researchers fuels diversity-driven investigation and can be useful in the charge to increase fibroid research.

Education and training: Changing the work force

Achieving equity requires change in provider work force. In a study of trends across multiple specialties including obstetrics and gynecology, Blacks and Latinx are more under-represented in 2016 than in 1990 across all specialties except for Black women in obstetrics and gynecology.28 It is well documented that under-represented minorities are more likely to engage in practice, research, service, and mentorship activities aligned with their identity.29 As a higher proportion of under-represented minority obstetricians and gynecologists practice in medically underserved areas,30 this presents a unique opportunity for gynecologists to improve care for and increase research involvement among BIPOC women.

Increasing BIPOC representation in medical and health care institutions and practices is not enough, however, to achieve health equity. Data from the Association of American Medical Colleges demonstrate that between 1978 and 2017 the total number of full-time obstetrics and gynecology faculty rose nearly fourfold from 1,688 to 6,347; however, the greatest rise in proportion of faculty who were nontenured was among women who were under-represented minorities.31 Additionally, there are disparities in wage by race even after controlling for hours worked and state of residence.32 Medical and academic centers and health care institutions and practices should proactively and systematically engage in the recruitment and retention of under-represented minority physicians and people in leadership roles. This will involve creating safe and inclusive work environments, with equal pay and promotion structures.

Quality initiatives to address provider bias

Provider bias should be addressed in clinical decision making and counseling of patients. Studies focused on ultrasonography have shown an estimated cumulative incidence of fibroids by age 50 of greater than 80% for Black women and nearly 70% for White women.5 Due to the prevalence and burden of fibroids among Black women there may be a provider bias in approach to management. Addressing this bias requires quality improvement efforts and investigation into patient and provider factors in management of fibroids. Black women have been a vulnerable population in medicine due to instances of mistreatment, and often times mistrust can play a role in how a patient views his or her care decisions. A patient-centered strategy allows patient factors such as age, uterine size, and cultural background to be considered such that a provider can tailor an approach that is best for the patient. Previous minority women focus groups have demonstrated that women have a strong desire for elective treatment;33 therefore, providers should listen openly to patients about their values and their perspectives on how fibroids affect their lives. Provider bias toward surgical volume, incentive for surgery, and implicit bias need to be addressed at every institution to work toward equitable and cost-effective care.

Integrated health care systems like Southern and Northern California Permanente Medical Group, using quality initiatives, have increased their minimally invasive surgery rates. Southern California Permanente Medical Group reached a 78% rate of MIH in a system of more than 350 surgeons performing benign indication hysterectomies as reported in 2011.34 Similarly, a study within KPNC, an institution with an MIH rate greater than 95%,35 found that racial disparities in route of MIH were eliminated through a quality improvement initiative described in detail in 2018 (FIGURE and TABLE).36

Conclusions

There are recognized successes in the gynecology field’s efforts to address racial disparities. Prior studies provide insight into opportunities to improve care in medical management of leiomyomas, minimally invasive route of hysterectomy and myomectomy, postsurgical outcomes, and institutional leadership. Particularly, when systemwide approaches are taken in the delivery of health care it is possible to significantly diminish racial disparities in gynecology.35 Much work remains to be done for our health care systems to provide equitable care.

- Ojanuga D. The medical ethics of the ‘father of gynaecology,’ Dr J Marion Sims. J Med Ethics. 1993;19:28-31. doi: 10.1136/jme.19.1.28.

- Borrero S, Zite N, Creinin MD. Federally funded sterilization: time to rethink policy? Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1822-1825.

- Eaglehouse YL, Georg MW, Shriver CD, et al. Racial differences in time to breast cancer surgery and overall survival in the US Military Health System. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:e185113. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5113.

- Soliman AM, Yang H, Du EX, et al. The direct and indirect costs of uterine fibroid tumors: a systematic review of the literature between 2000 and 2013. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:141-160.

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

- Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:967-973. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00534-6.

- Styer AK, Rueda BR. The epidemiology and genetics of uterine leiomyoma. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;34:3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.11.018.

- Al-Hendy A, Myers ER, Stewart E. Uterine fibroids: burden and unmet medical need. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35:473-480. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607264.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin. Alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387-400.

- Corona LE, Swenson CW, Sheetz KH, et al. Use of other treatments before hysterectomy for benign conditions in a statewide hospital collaborative. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:304.e1-e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.031.

- Nguyen NT, Merchant M, Ritterman Weintraub ML, et al. Alternative treatment utilization before hysterectomy for benign gynecologic conditions at a large integrated health system. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:847-855. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.08.013.

- Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Jacoby VL, Myers ER. Disparities in fibroid incidence, prognosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:81-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2016.11.007.

- Borah BJ, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Myers ER, et al. Association between patient characteristics and treatment procedure among patients with uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:67-77.

- Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000-2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:34.e1-e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.039.

- Bardens D, Solomayer E, Baum S, et al. The impact of the body mass index (BMI) on laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:803-807. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-3050-2.

- Seracchioli R, Venturoli S, Vianello F, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy in the presence of a large uterus. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:333-338. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60413.

- Boyd LR, Novetsky AP, Curtin JP. Effect of surgical volume on route of hysterectomy and short-term morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:909-915. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f395d9.

- Jin C, Hu Y, Chen XC, et al. Laparoscopic versus open myomectomy—a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:14-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.03.009.

- Wechter ME, Stewart EA, Myers ER, et al. Leiomyoma-related hospitalization and surgery: prevalence and predicted growth based on population trends. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:492.e1-e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.008.

- Bower JK, Schreiner PJ, Sternfeld B, et al. Black-White differences in hysterectomy prevalence: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:300-307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.133702.

- Ranjit A, Sharma M, Romano A, et al. Does universal insurance mitigate racial differences in minimally invasive hysterectomy? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2017.03.016.

- Pollack LM, Olsen MA, Gehlert SJ, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities/differences in hysterectomy route in women likely eligible for minimally invasive surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1167-1177.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2019.09.003.

- Stentz NC, Cooney LG, Sammel MD, et al. Association of patient race with surgical practice and perioperative morbidity after myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:291-297. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002738.

- Roth TM, Gustilo-Ashby T, Barber MD, et al. Effects of race and clinical factors on short-term outcomes of abdominal myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(5 pt 1):881-884. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00015-2.

- Bratka S, Diamond JS, Al-Hendy A, et al. The role of vitamin D in uterine fibroid biology. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:698-706. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.05.031.

- Ciebiera M, Łukaszuk K, Męczekalski B, et al. Alternative oral agents in prophylaxis and therapy of uterine fibroids—an up-to-date review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2586. doi:10.3390/ijms18122586.

- Hayden EC. Racial bias haunts NIH funding. Nature. 2015;527:145.

- Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207274.

- Sánchez JP, Poll-Hunter N, Stern N, et al. Balancing two cultures: American Indian/Alaska Native medical students’ perceptions of academic medicine careers. J Community Health. 2016;41:871-880.

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, et al. Racial and ethnic differences between obstetrician-gynecologists and other adult medical specialists. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:148-152. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001184.

- Esters D, Xierali IM, Nivet MA, et al. The rise of nontenured faculty in obstetrics and gynecology by sex and underrepresented in medicine status. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134 suppl 1:34S-39S. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003484.

- Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB. Differences in incomes of physicians in the United States by race and sex: observational study. BMJ. 2016;I2923. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2923.

- Groff JY, Mullen PD, Byrd T, et al. Decision making, beliefs, and attitudes toward hysterectomy: a focus group study with medically underserved women in Texas. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9 suppl 2:S39-50. doi: 10.1089/152460900318759.

- Andryjowicz E, Wray T. Regional expansion of minimally invasive surgery for hysterectomy: implementation and methodology in a large multispecialty group. Perm J. 2011;15:42-46.

- Zaritsky E, Ojo A, Tucker LY, et al. Racial disparities in route of hysterectomy for benign indications within an integrated health care system. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1917004. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.17004.

- Abel MK, Kho KA, Walter A, et al. Measuring quality in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery: what, how, and why? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:321-326. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.11.013.

- Ojanuga D. The medical ethics of the ‘father of gynaecology,’ Dr J Marion Sims. J Med Ethics. 1993;19:28-31. doi: 10.1136/jme.19.1.28.

- Borrero S, Zite N, Creinin MD. Federally funded sterilization: time to rethink policy? Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1822-1825.

- Eaglehouse YL, Georg MW, Shriver CD, et al. Racial differences in time to breast cancer surgery and overall survival in the US Military Health System. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:e185113. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5113.

- Soliman AM, Yang H, Du EX, et al. The direct and indirect costs of uterine fibroid tumors: a systematic review of the literature between 2000 and 2013. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:141-160.

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

- Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:967-973. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00534-6.

- Styer AK, Rueda BR. The epidemiology and genetics of uterine leiomyoma. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;34:3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.11.018.

- Al-Hendy A, Myers ER, Stewart E. Uterine fibroids: burden and unmet medical need. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35:473-480. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607264.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin. Alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387-400.

- Corona LE, Swenson CW, Sheetz KH, et al. Use of other treatments before hysterectomy for benign conditions in a statewide hospital collaborative. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:304.e1-e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.031.

- Nguyen NT, Merchant M, Ritterman Weintraub ML, et al. Alternative treatment utilization before hysterectomy for benign gynecologic conditions at a large integrated health system. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:847-855. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.08.013.

- Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Jacoby VL, Myers ER. Disparities in fibroid incidence, prognosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:81-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2016.11.007.

- Borah BJ, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Myers ER, et al. Association between patient characteristics and treatment procedure among patients with uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:67-77.

- Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000-2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:34.e1-e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.039.

- Bardens D, Solomayer E, Baum S, et al. The impact of the body mass index (BMI) on laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:803-807. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-3050-2.

- Seracchioli R, Venturoli S, Vianello F, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy in the presence of a large uterus. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:333-338. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60413.

- Boyd LR, Novetsky AP, Curtin JP. Effect of surgical volume on route of hysterectomy and short-term morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:909-915. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f395d9.

- Jin C, Hu Y, Chen XC, et al. Laparoscopic versus open myomectomy—a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:14-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.03.009.

- Wechter ME, Stewart EA, Myers ER, et al. Leiomyoma-related hospitalization and surgery: prevalence and predicted growth based on population trends. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:492.e1-e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.008.

- Bower JK, Schreiner PJ, Sternfeld B, et al. Black-White differences in hysterectomy prevalence: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:300-307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.133702.

- Ranjit A, Sharma M, Romano A, et al. Does universal insurance mitigate racial differences in minimally invasive hysterectomy? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2017.03.016.

- Pollack LM, Olsen MA, Gehlert SJ, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities/differences in hysterectomy route in women likely eligible for minimally invasive surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1167-1177.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2019.09.003.

- Stentz NC, Cooney LG, Sammel MD, et al. Association of patient race with surgical practice and perioperative morbidity after myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:291-297. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002738.

- Roth TM, Gustilo-Ashby T, Barber MD, et al. Effects of race and clinical factors on short-term outcomes of abdominal myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(5 pt 1):881-884. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00015-2.

- Bratka S, Diamond JS, Al-Hendy A, et al. The role of vitamin D in uterine fibroid biology. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:698-706. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.05.031.

- Ciebiera M, Łukaszuk K, Męczekalski B, et al. Alternative oral agents in prophylaxis and therapy of uterine fibroids—an up-to-date review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2586. doi:10.3390/ijms18122586.

- Hayden EC. Racial bias haunts NIH funding. Nature. 2015;527:145.

- Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207274.

- Sánchez JP, Poll-Hunter N, Stern N, et al. Balancing two cultures: American Indian/Alaska Native medical students’ perceptions of academic medicine careers. J Community Health. 2016;41:871-880.

- Rayburn WF, Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, et al. Racial and ethnic differences between obstetrician-gynecologists and other adult medical specialists. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:148-152. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001184.

- Esters D, Xierali IM, Nivet MA, et al. The rise of nontenured faculty in obstetrics and gynecology by sex and underrepresented in medicine status. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134 suppl 1:34S-39S. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003484.

- Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB. Differences in incomes of physicians in the United States by race and sex: observational study. BMJ. 2016;I2923. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2923.

- Groff JY, Mullen PD, Byrd T, et al. Decision making, beliefs, and attitudes toward hysterectomy: a focus group study with medically underserved women in Texas. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9 suppl 2:S39-50. doi: 10.1089/152460900318759.

- Andryjowicz E, Wray T. Regional expansion of minimally invasive surgery for hysterectomy: implementation and methodology in a large multispecialty group. Perm J. 2011;15:42-46.

- Zaritsky E, Ojo A, Tucker LY, et al. Racial disparities in route of hysterectomy for benign indications within an integrated health care system. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1917004. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.17004.

- Abel MK, Kho KA, Walter A, et al. Measuring quality in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery: what, how, and why? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:321-326. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.11.013.

Placental allograft, cytology processor, cell-free RNA testing, and male infertility

Human placental allograft

For case reports involving Revita and for more information, visit https://www.stimlabs.com/revita.

FDA approval for cytology processor

For more information, visit: https://www.hologic.com/.

Cell-free RNA testing for pregnancy complications

Currently, Mirvie is recruiting for their Miracle of Life study, which requests that single gestation pregnant mothers who are not scheduled for cesarean delivery provide a blood sample during their second trimester. Women can see if they are eligible for study participation by visiting https://www.curebase.com/study/miracle/home.

For more information, visit: https://mirvie.com/.

Male fertility platform

For more information, visit: https://posterityhealth.com/.

Human placental allograft

For case reports involving Revita and for more information, visit https://www.stimlabs.com/revita.

FDA approval for cytology processor

For more information, visit: https://www.hologic.com/.

Cell-free RNA testing for pregnancy complications

Currently, Mirvie is recruiting for their Miracle of Life study, which requests that single gestation pregnant mothers who are not scheduled for cesarean delivery provide a blood sample during their second trimester. Women can see if they are eligible for study participation by visiting https://www.curebase.com/study/miracle/home.

For more information, visit: https://mirvie.com/.

Male fertility platform

For more information, visit: https://posterityhealth.com/.

Human placental allograft

For case reports involving Revita and for more information, visit https://www.stimlabs.com/revita.

FDA approval for cytology processor

For more information, visit: https://www.hologic.com/.

Cell-free RNA testing for pregnancy complications

Currently, Mirvie is recruiting for their Miracle of Life study, which requests that single gestation pregnant mothers who are not scheduled for cesarean delivery provide a blood sample during their second trimester. Women can see if they are eligible for study participation by visiting https://www.curebase.com/study/miracle/home.

For more information, visit: https://mirvie.com/.

Male fertility platform

For more information, visit: https://posterityhealth.com/.

Hepatitis in pregnancy: Sorting through the alphabet

A 27-year-old primigravida at 9 weeks 3 days of gestation tests positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen at her first prenatal appointment. She is completely asymptomatic.

- What additional tests are indicated?

- Does she pose a risk to her sexual partner, and is her newborn at risk for acquiring hepatitis B?

- Can anything be done to protect her partner and newborn from infection?

Meet our perpetrator

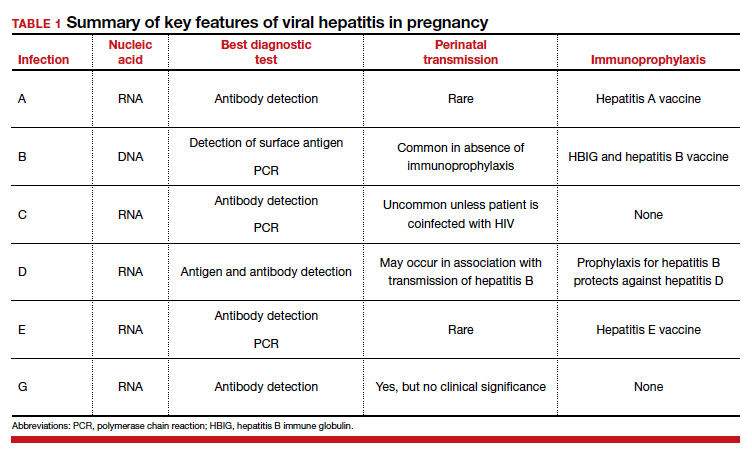

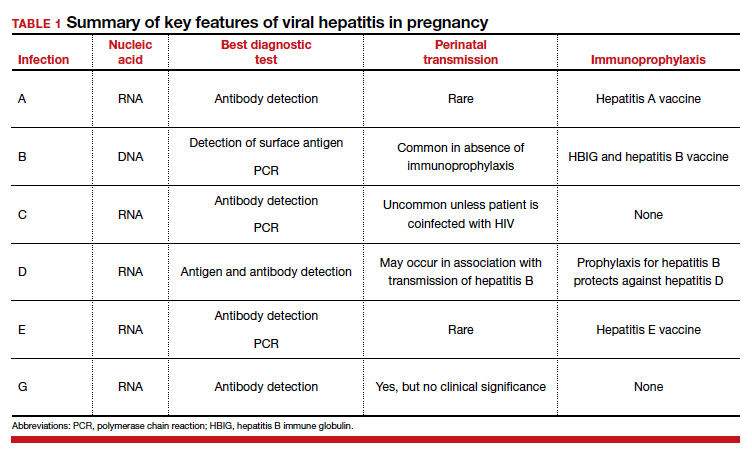

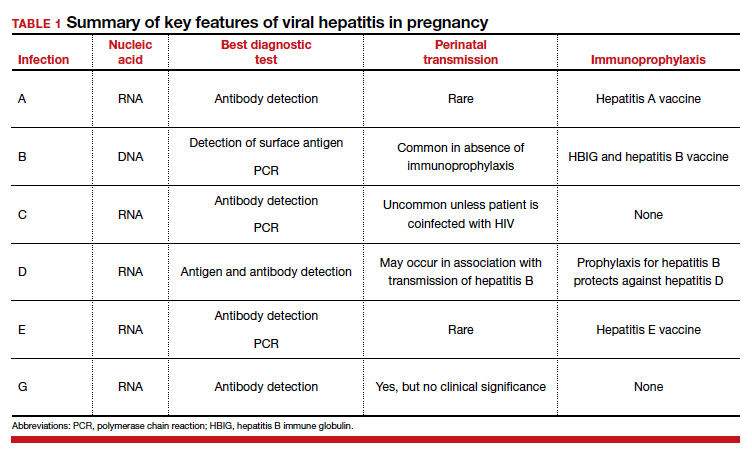

Hepatitis is one of the more common viral infections that may occur during pregnancy. Two forms of hepatitis, notably hepatitis A and E, pose a primary threat to the mother. Three forms (B, C, and D) present dangers for the mother, fetus, and newborn. This article will review the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, perinatal implications, and management of the various forms of viral hepatitis. (TABLE 1).

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is caused by an RNA virus that is transmitted by fecal-oral contact. The disease is most prevalent in areas with poor sanitation and close living conditions. The incubation period ranges from 15 to 50 days. Most children who acquire this disease are asymptomatic. By contrast, most infected adults are acutely symptomatic. Clinical manifestations typically include low-grade fever, malaise, anorexia, right upper quadrant pain and tenderness, jaundice, and claycolored stools.1,2

The diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection is best confirmed by detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM)-specific antibodies. The serum transaminase concentrations and the serum bilirubin concentrations usually are significantly elevated. The international normalized ratio, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time also may be elevated.1,2

The treatment for acute hepatitis A largely is supportive care: maintaining hydration, optimizing nutrition, and correcting coagulation abnormalities. The appropriate measures for prevention of hepatitis A are adoption of sound sanitation practices, particularly water purification; minimizing overcrowded living conditions; and administering the hepatitis A vaccine for both pre and postexposure prophylaxis.3,4 The hepatitis A vaccine is preferred over administration of immune globulin because it provides lifelong immunity.

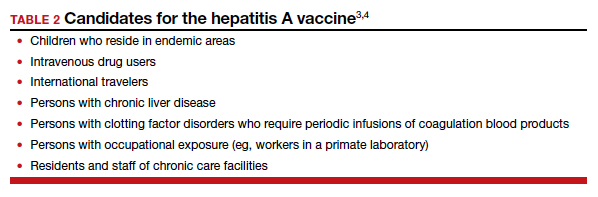

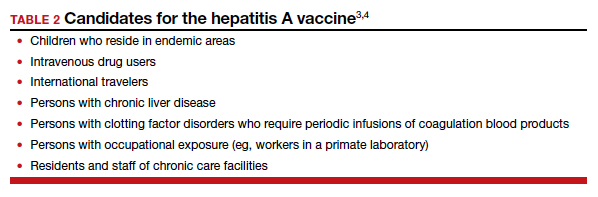

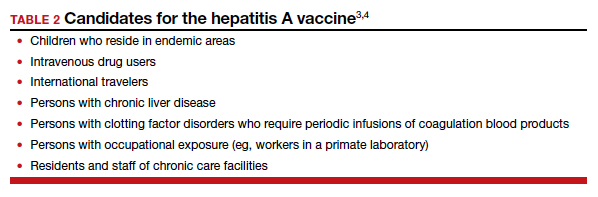

The hepatitis A vaccine is produced in 2 monovalent formulations: Havrix (GlaxoSmithKline) and Vaqta (Merck & Co, Inc). The vaccine should be administered intramuscularly in 2 doses 6 to 12 months apart. The wholesale cost of the vaccine varies from $66 to $119 (according to http://www.goodrx.com). The vaccine also is available in a bivalent form, with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine (Twinrix, GlaxoSmithKline). When used in this form, 3 vaccine administrations are given—at 0, 1, and 6 months apart. The cost of the vaccine is approximately $150 (according to http://www.goodrx.com). TABLE 2 lists the individuals who are appropriate candidates for the hepatitis A vaccine.3,4

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is caused by a DNA virus that is transmitted parenterally or perinatally or through

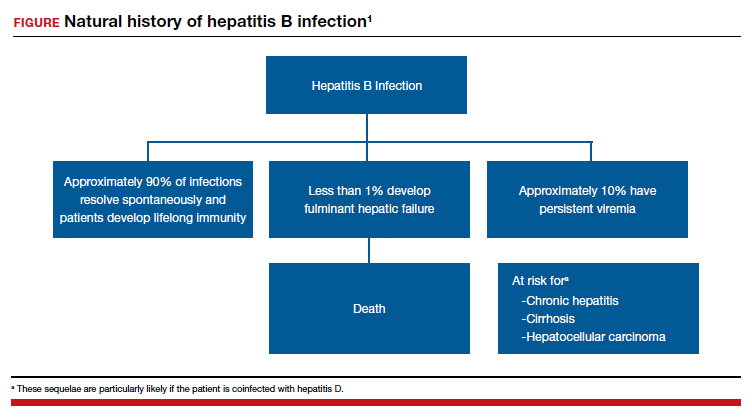

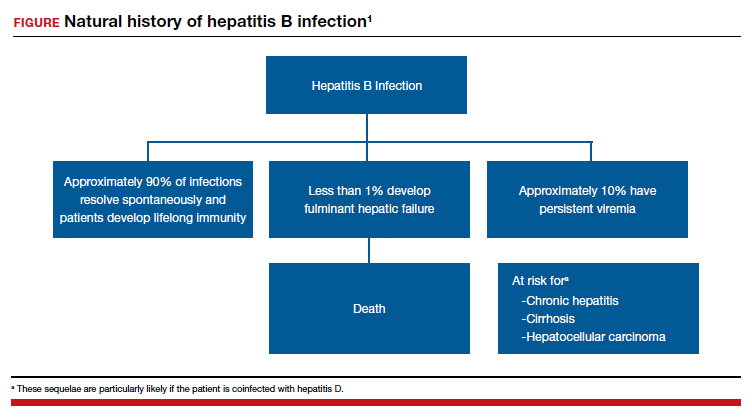

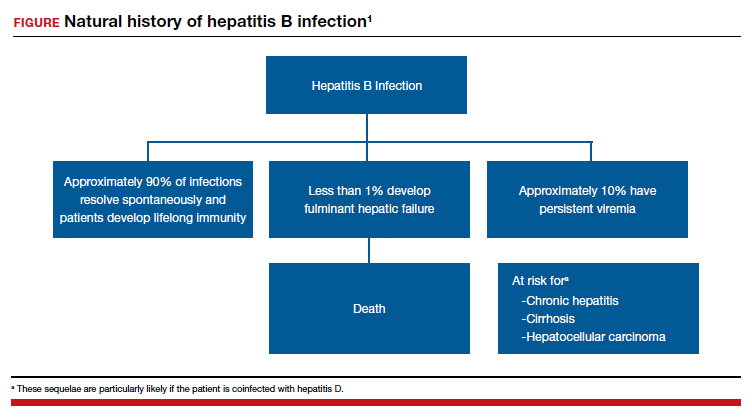

Acute hepatitis B affects 1 to 2 of 1,000 pregnancies in the United States. Approximately 6 to 10 patients per 1,000 pregnancies are asymptomatic but chronically infected.4 The natural history of hepatitis B infection is shown in the FIGURE. The diagnosis of acute and chronic hepatitis B is best established by serology and polymerase chain reaction (PCR; TABLE 3).

All pregnant women should be routinely screened for the hepatitis B surface antigen.5,6 If they are seropositive for the surface antigen alone and receive no immunoprophylaxis, they have a 20% to 30% risk of transmitting infection to their neonate. Subsequently, if they also test positive for the hepatitis Be antigen, the risk of perinatal transmission increases to approximately 90%. Fortunately, 2 forms of immunoprophylaxis are highly effective in preventing perinatal transmission. Infants delivered to seropositive mothers should receive hepatitis B immune globulin within 12 hours of birth. Prior to discharge, the infant also should receive the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine. Subsequent doses should be administered at 1 and 6 months of age. Infants delivered to seronegative mothers require only the vaccine series.1

Although immunoprophylaxis is highly effective, some neonates still acquire infection perinatally. Pan and colleagues7 and Jourdain et al8 demonstrated that administration of tenofovir 200 mg orally each day from 32 weeks’ gestation until delivery provided further protection against perinatal transmission in patients with a high viral load (defined as >1 million copies/mL). In 2016, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine endorsed the use of tenofovir in women with a high viral load.6

Following delivery, women with chronic hepatitis B infection should be referred to a hepatology specialist for consideration of direct antiviral treatment. Multiple drugs are now available that are highly active against this micro-organism. These drugs include several forms of interferon, lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, and tenofovir.1

Continue to: Hepatitis C...

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is caused by an RNA virus that has 6 genotypes. The most common genotype is HCV1, which affects 79% of patients; approximately 13% of patients have HCV2, and 6% have HCV3.9 Of note, the 3 individuals who discovered this virus—Drs. Harvey Alter, Michael Houghton, and Charles Rice—received the 2020 Nobel Prize in Medicine.10

Hepatitis C is transmitted via sexual contact, parenterally, and perinatally. In many patient populations in the United States, hepatitis C is now more prevalent than hepatitis B. Only about half of all infected persons are aware of their infection. If patients go untreated, approximately 15% to 30% eventually develop cirrhosis. Of these individuals, 1% to 3% develop hepatocellular cancer. Chronic hepatitis C is now the most common indication for liver transplantation in the United States.1,9

In the initial stages of infection, hepatitis C usually is asymptomatic. The best screening test is detection of hepatitis C antibody. Because of the increasing prevalence of this disease, the seriousness of the infection, and the recent availability of remarkably effective treatment, routine screening, rather than screening on the basis of risk factors, for hepatitis C in pregnancy is now indicated.11,12

The best tests for confirmation of infection are detection of antibody by enzyme immunoassay and recombinant immuno-blot assay and detection of viral RNA in serum by PCR. Seroconversion may not occur for up to 16 weeks after infection. Therefore, in at-risk patients who initially test negative, retesting is advisable. Patients with positive test results should have tests to identify the specific genotype, determine the viral load, and assess liver function.1

In patients who have undetectable viral loads and who do not have coexisting HIV infection, the risk of perinatal transmission of hepatitis C is less than 5%. If HIV infection is present, the risk of perinatal transmission approaches 20%.1,13,14

If the patient is coinfected with HIV, a scheduled cesarean delivery should be performed at 38 weeks’ gestation.1 If the viral load is undetectable, vaginal delivery is appropriate. If the viral load is high, however (arbitrarily defined as >2.5 millioncopies/mL), the optimal method of delivery is controversial. Several small, nonrandomized noncontrolled cohort studies support elective cesarean delivery in such patients.14

There is no contraindication to breastfeeding in women with hepatitis C unless they are coinfected with HIV. In such a circumstance, formula feeding should be chosen. After delivery, patients with hepatitis C should be referred to a gastroenterology specialist to receive antiviral treatment. Multiple new single-agent and combination regimens have produced cures in more than 90% of patients. These regimens usually require 8 to 12 weeks of treatment, and they are very expensive. They have not been widely tested in pregnant women.1

Hepatitis D

Hepatitis D, or delta hepatitis, is caused by an RNA virus. This virus is unique because it is incapable of independent replication. It must be present in association with hepatitis B to replicate and cause clinical infection. Therefore, the epidemiology of hepatitis D closely mirrors that of hepatitis B.1,2

Patients with hepatitis D typically present in one of two ways. Some individuals are acutely infected with hepatitis D at the same time that they acquire hepatitis B (coinfection). The natural history of this infection usually is spontaneous resolution without sequelae. Other patients have chronic hepatitis D superimposed on chronic hepatitis B (superinfection). Unfortunately, patients with the latter condition are at a notably increased risk for developing severe persistent liver disease.1,2

The diagnosis of hepatitis D may be confirmed by identifying the delta antigen in serum or in liver tissue obtained by biopsy or by identifying IgM- and IgG-specific antibodies in serum. In conjunction with hepatitis B, the delta virus can cause a chronic carrier state. Perinatal transmission is possible but uncommon. Of greatest importance, the immunoprophylaxis described for hepatitis B is almost perfectly protective against perinatal transmission of hepatitis D.1,2

Continue to: Hepatitis E...

Hepatitis E

Hepatitis E is an RNA virus that has 1 serotype and 4 genotypes. Its epidemiology is similar to that of hepatitis A. It is the most common waterborne illness in the world. The incubation period varies from 21 to 56 days. This disease is quite rare in the United States but is endemic in developing nations. In those countries, maternal infection has an alarmingly high mortality rate (5%–25%). For example, in Bangladesh, hepatitis E is responsible for more than 1,000 deaths per year in pregnant women. When hepatitis E is identified in more affluent countries, the individual cases and small outbreaks usually are linked to consumption of undercooked pork or wild game.1,15-17

The clinical presentation of acute hepatitis E also is similar to that of hepatitis A. The usual manifestations are fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea, right upper quadrant pain and tenderness, jaundice, darkened urine, and clay-colored stools. The most useful diagnostic tests are serologic detection of viral-specific antibodies (positive IgM or a 4-fold increase in the prior IgG titer) and PCR-RNA.1,17

Hepatitis E usually does not cause a chronic carrier state, and perinatal transmission is rare. Fortunately, a highly effective vaccine was recently developed (Hecolin, Xiamen Innovax Biotech). This recombinant vaccine is specifically directed against the hepatitis E genotype 1. In the initial efficacy study, healthy adults aged 16 to 65 years were randomly assigned to receive either the hepatitis E vaccine or the hepatitis B vaccine. The vaccine was administered at time point 0, and 1 and 6 months later. Patients were followed for up to 4.5 years to assess efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety. During the study period, 7 cases of hepatitis E occurred in the vaccine group, compared with 53 in the control group. Approximately 56,000 patients were included in each group. The efficacy of the vaccine was 86.8% (P<.001).18

Hepatitis G

Hepatitis G is caused by 2 single-stranded RNA viruses that are virtually identical—hepatitis G virus and GB virus type C. The viruses share approximately 30% homology with hepatitis C virus. The organism is present throughout the world and infects approximately 1.5% to 2.0% of the population. The virus is transmitted by blood and sexual contact. It replicates preferentially in mononuclear cells and the bone marrow rather than in the liver.19-21

Hepatitis G is much less virulent than hepatitis C. Hepatitis G often coexists with hepatitis A, B, and C, as well as with HIV. Coinfection with hepatitis G does not adversely affect the clinical course of the other conditions.22,23

Most patients with hepatitis G are asymptomatic, and no treatment is indicated. The virus can cause a chronic carrier state. Perinatal transmission is distinctly uncommon. When it does occur, however, injury to mother, fetus, or neonate is unlikely.1,24

The diagnosis of hepatitis G can be established by detection of virus with PCR and by the identification of antibody by enzyme immunoassay. Routine screening for this infection in pregnancy is not indicated.1,2

Hepatitis B is highly contagious and can be transmitted from the patient to her sexual partner and neonate. Testing for hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody is indicated in her partner. If these tests are negative, the partner should immediately receive hepatitis B immune globulin and then be started on the 3-dose hepatitis B vaccination series. The patient’s newborn also should receive hepatitis B immune globulin within 12 hours of delivery and should receive the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine prior to discharge from the hospital. The second and third doses should be administered 1 and 6 months after delivery.

The patient also should have the following tests:

• liver function tests

-serum transaminases

-direct and indirect bilirubin

-coagulation profile

• hepatitis D antigen

• hepatitis B genotype

• hepatitis B viral load

• HIV serology.

If the hepatitis B viral load exceeds 1 million copies/mL, the patient should be treated with tenofovir 200 mg daily from 28 weeks’ gestation until delivery. In addition, she should be referred to a liver disease specialist after delivery for consideration of treatment with directly-acting antiviral agents. ●

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TB, et al, eds. Creasy & Resnik’s MaternalFetal Medicine Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Hepatitis in pregnancy. In: Queenan JR, Spong CY, Lockwood CJ, eds. Management of HighRisk Pregnancy. An EvidenceBased Approach. 5th ed. Blackwell; 2007:238-241.

- Duff B, Duff P. Hepatitis A vaccine: ready for prime time. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:468-471.

- Victor JC, Monto AS, Surdina TY, et al. Hepatitis A vaccine versus immune globulin for postexposure prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2007;367:1685-1694.

- Dienstag JL. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1486-1500.

- Society for MaternalFetal Medicine (SMFM); Dionne-Odom J, Tita ATN, Silverman NS. #38. Hepatitis B in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and prevention of vertical transmission. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:6-14.

- Pan CQ, Duan Z, Dai E, et al. Tenofovir to prevent hepatitis B transmission in mothers with high viral load. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2324-2334.

- Jourdain G, Huong N, Harrison L, et al. Tenofovir versus placebo to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:911-923.

- Rosen HR. Chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2429-2438.

- Hoofnagle JH, Feinstore SM. The discovery of hepatitis C—the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:2297-2299.

- Hughes BL, Page CM, Juller JA. Hepatitis C in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:B2-B12.

- Saab S, Kullar R, Gounder P. The urgent need for hepatitis C screening in pregnant women: a call to action. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:773-777.

- Berkley EMF, Leslie KK, Arora S, et al. Chronic hepatitis C in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:304-310.

- Brazel M, Duff P. Considerations on the mode of delivery for pregnant women with hepatitis C infection [published online November 22, 2019]. OBG Manag. 2020;32:39-44.

- Emerson SU, Purcell RH. Hepatitis E virus. Rev Med Virol. 2003;13:145-154.