User login

Adverse pregnancy outcomes and later cardiovascular disease

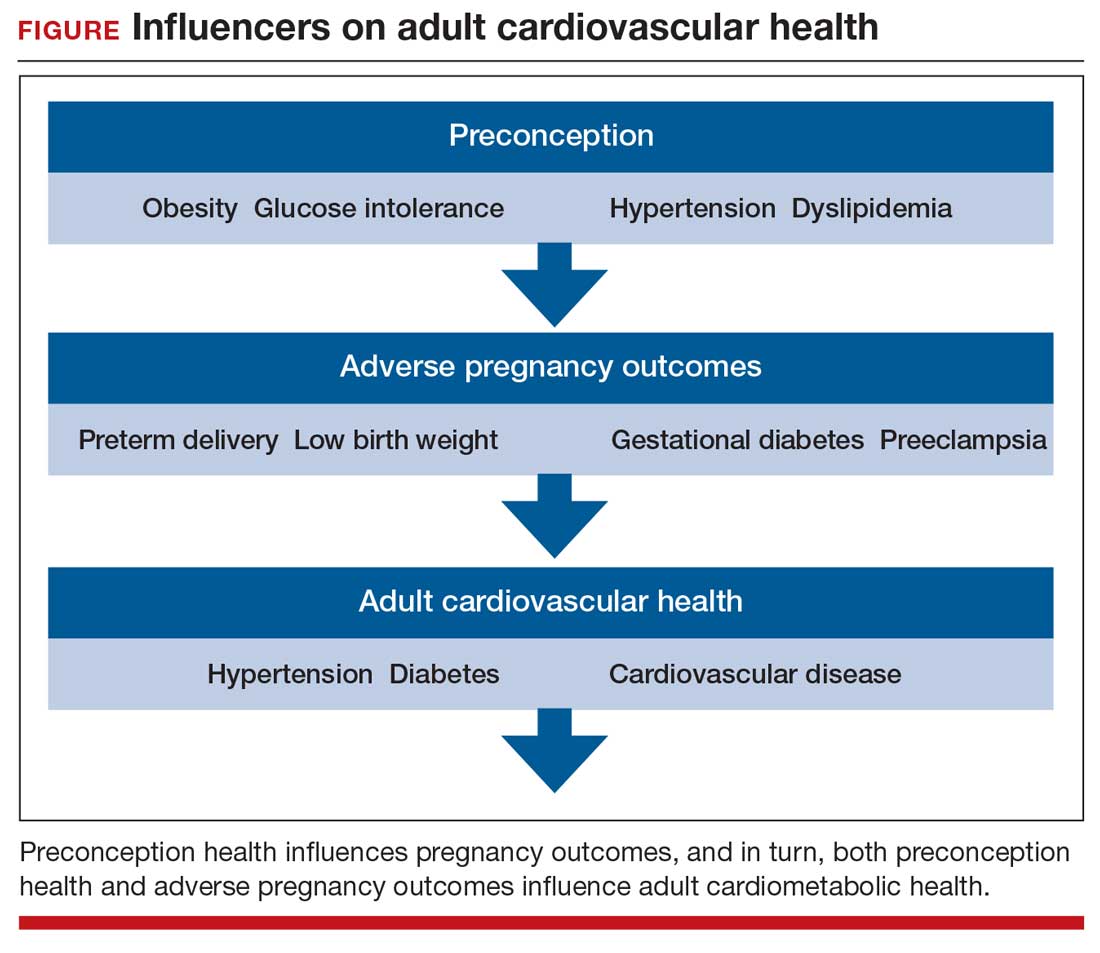

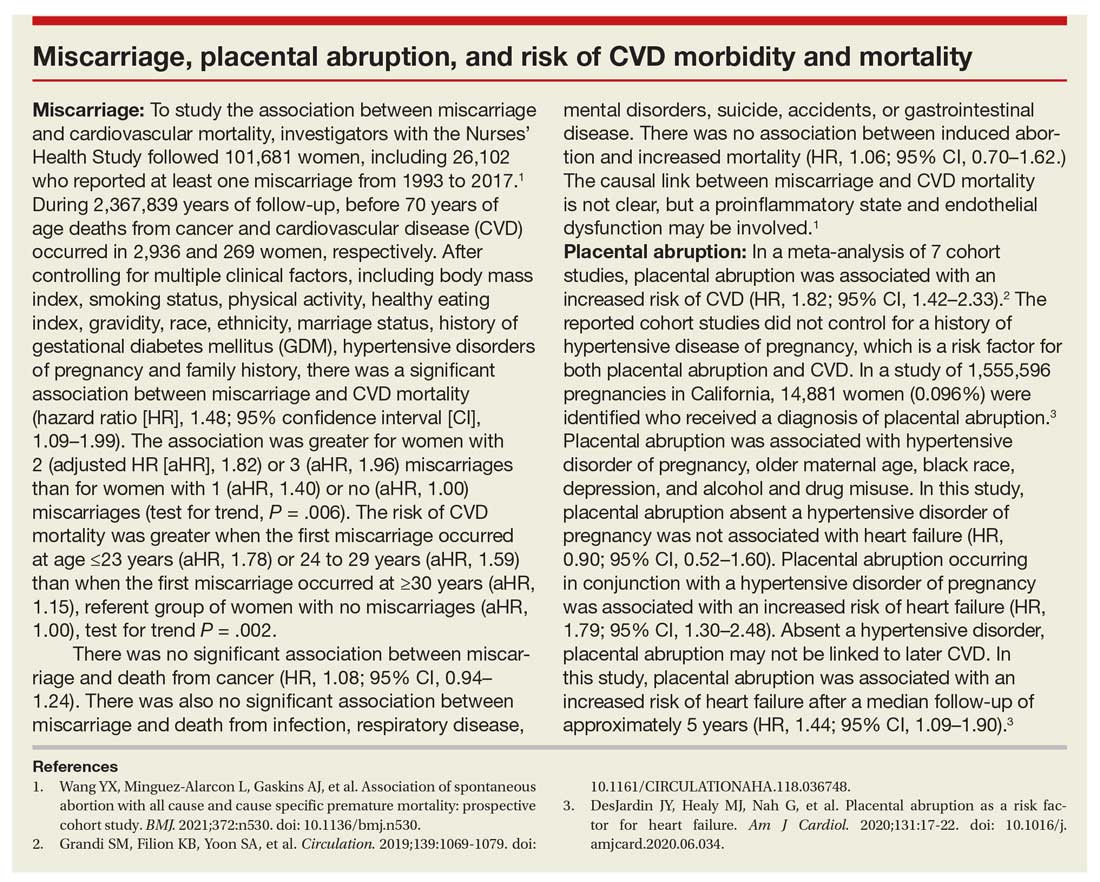

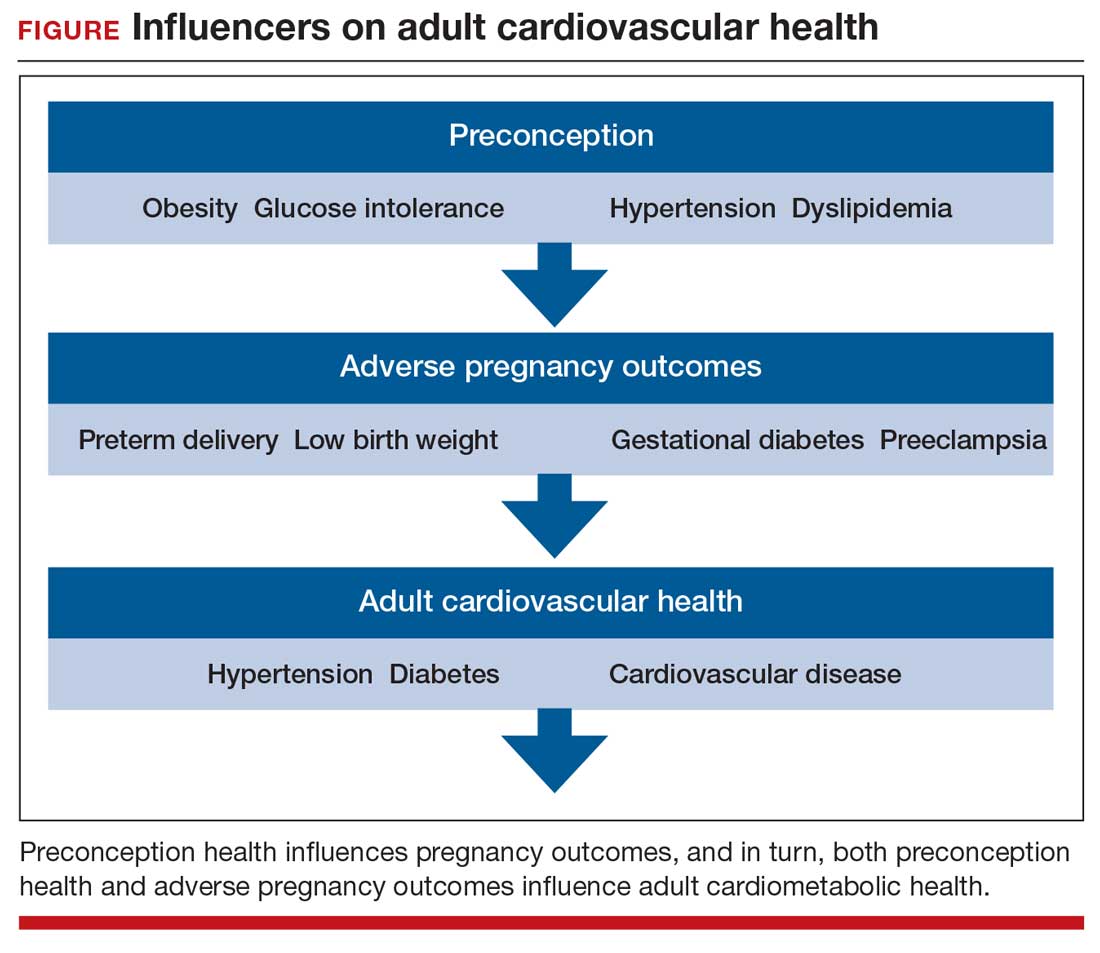

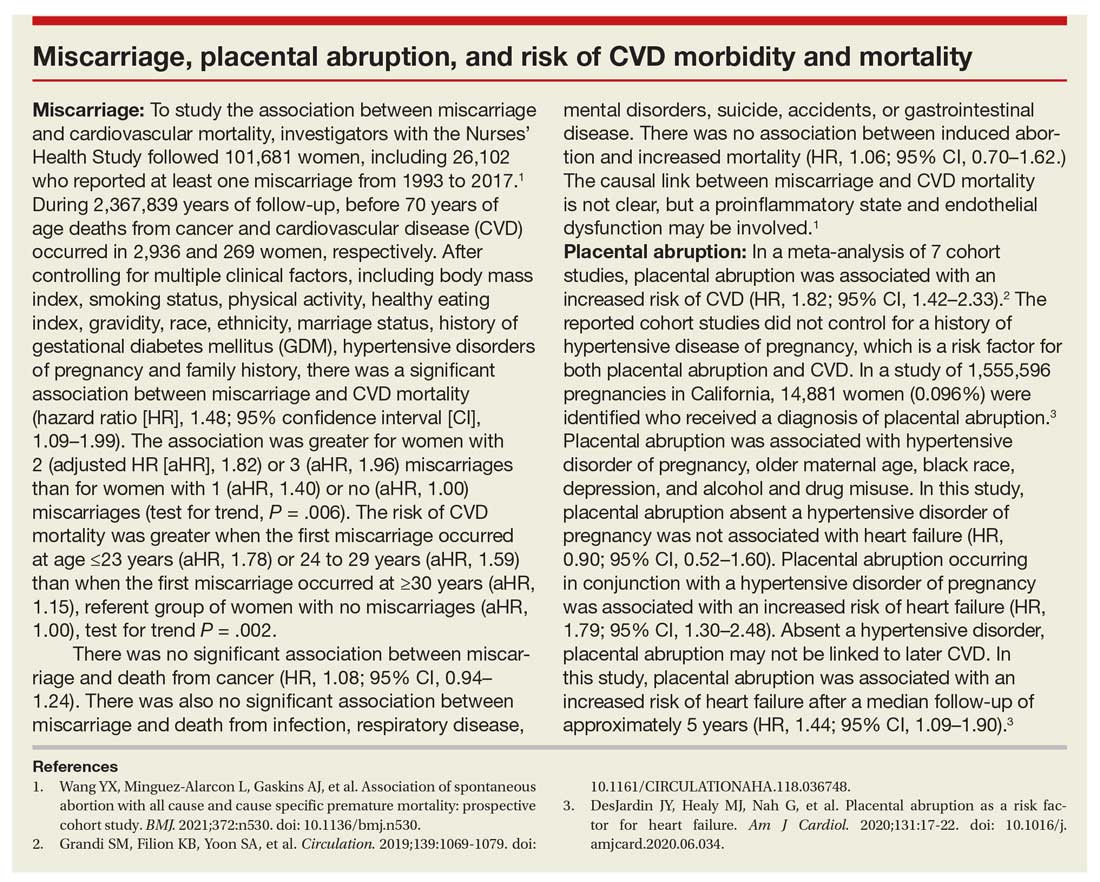

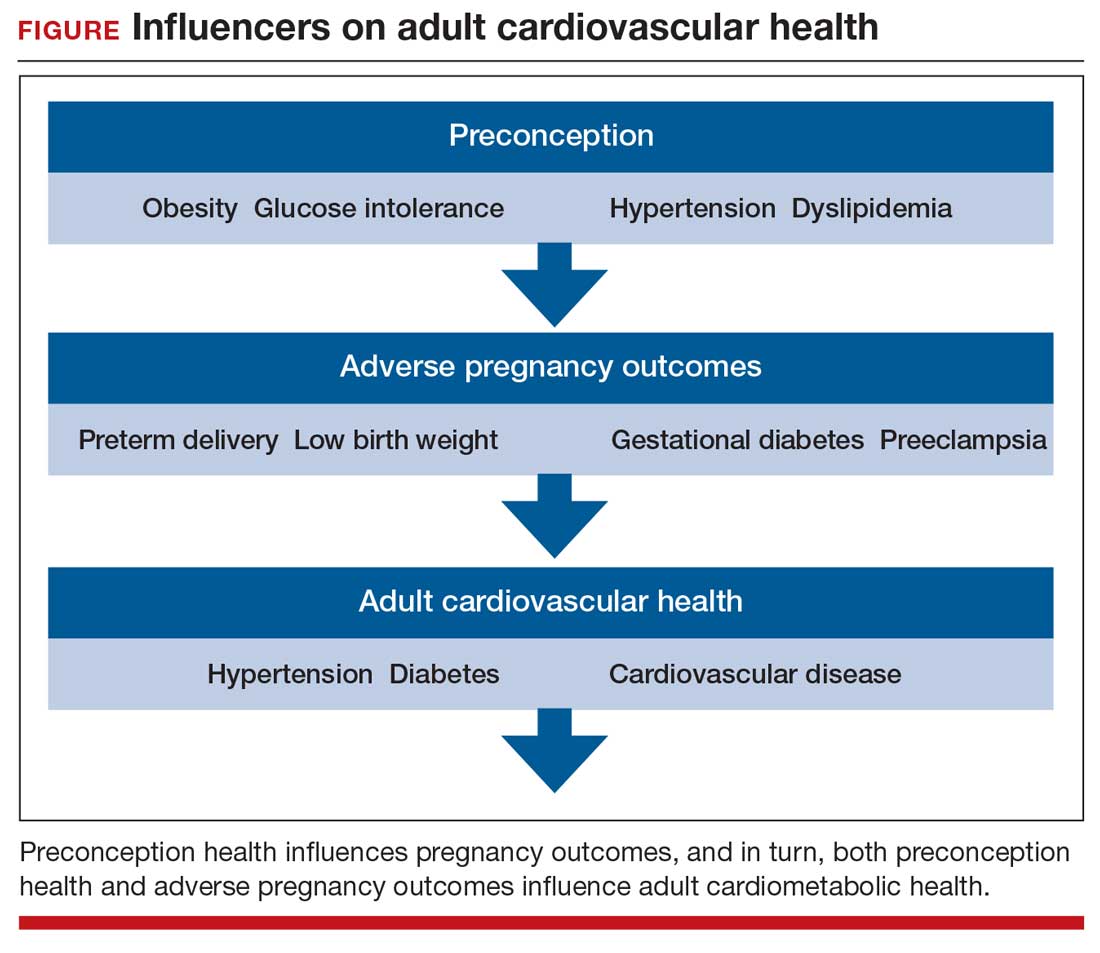

Preconception health influences pregnancy outcomes, and in turn, both preconception health and an APO influence adult cardiometabolic health (FIGURE). This editorial is focused on the link between APOs and later cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality, recognizing that preconception health greatly influences the risk of an APO and lifetime cardiometabolic disease.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

Major APOs include miscarriage, preterm birth (birth <37 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (birth weight ≤2,500 g; 5.5 lb), gestational diabetes (GDM), preeclampsia, and placental abruption. In the United States, among all births, reported rates of the following APOs are:1-3

- preterm birth, 10.2%

- low birth weight, 8.3%

- GDM, 6%

- preeclampsia, 5%

- placental abruption, 1%.

Miscarriage occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of pregnancies, influenced by both the age of the woman and the method used to diagnose pregnancy.4 Miscarriage, preterm birth, low birth weight, GDM, preeclampsia, and placental abruption have been reported to be associated with an increased risk of later cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

APOs and cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) affects the majority of people past the age of 60 years and includes 4 major subcategories:

- coronary heart disease, including myocardial infarction, angina, and heart failure

- CVD, stroke, and transient ischemic attack

- peripheral artery disease

- atherosclerosis of the aorta leading to aortic aneurysm.

Multiple meta-analyses report that APOs are associated with CVD in later life. A comprehensive review reported that the risk of CVD was increased following a pregnancy with one of these APOs: severe preeclampsia (odds ratio [OR], 2.74), GDM (OR, 1.68), preterm birth (OR, 1.93), low birth weight (OR, 1.29), and placental abruption (OR, 1.82).5

The link between APOs and CVD may be explained in part by the association of APOs with multiple risk factors for CVD, including chronic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and dyslipidemia. A meta-analysis of 43 studies reported that, compared with controls, women with a history of preeclampsia have a 3.13 times greater risk of developing chronic hypertension.6 Among women with preeclampsia, approximately 20% will develop hypertension within 15 years.7 A meta-analysis of 20 studies reported that women with a history of GDM had a 9.51-times greater risk of developing T2DM than women without GDM.8 Among women with a history of GDM, over 16 years of follow-up, T2DM was diagnosed in 16.2%, compared with 1.9% of control women.8

CVD prevention—Breastfeeding: An antidote for APOs

Pregnancy stresses both the cardiovascular and metabolic systems. Breastfeeding is an antidote to the stresses imposed by pregnancy. Breastfeeding women have lower blood glucose9 and blood pressure.10

Breastfeeding reduces the risk of CVD. In a study of 100,864 parous Australian women, with a mean age of 60 years, ever breastfeeding was associated a lower risk of CVD hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–0.96; P = .005) and CVD mortality (aHR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49–0.89; P = .006).11

Continue to: CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations...

CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations

The American Heart Association12 recommends lifestyle interventions to reduce the risk of CVD, including:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Live a tobacco- and nicotine-free life.

- Strive to maintain a normal body mass index.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

- After 40 years of age calculate CVD risk using a validated calculator such as the American Cardiology Association risk calculator.13 This calculator uses age, gender, and lipid and blood pressure measurements to calculate the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic CVD, including coronary death, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

Medications to reduce CVD risk

Historically, ObGyns have not routinely prescribed medications to treat hypertension, dyslipidemia, or to prevent diabetes. The recent increase in the valuation of return ambulatory visits and a reduction in the valuation assigned to procedural care may provide ObGyn practices the additional resources needed to manage some chronic diseases. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners may help ObGyn practices to manage hypertension, dyslipidemia, and prediabetes.

Prior to initiating a medicine, counseling about healthy living, including smoking cessation, exercise, heart-healthy diet, and achieving an optimal body mass index is warranted.

For treatment of stage II hypertension, defined as blood pressure (BP) measurements with systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, therapeutic lifestyle interventions include: optimizing weight, following the DASH diet, restricting dietary sodium, physical activity, and reducing alcohol consumption. Medication treatment for essential hypertension is guided by the magnitude of BP reduction needed to achieve normotension. For women with hypertension needing antihypertensive medication and planning another pregnancy in the near future, labetalol or extended-release nifedipine may be first-line medications. For women who have completed their families or who have no immediate plans for pregnancy, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker, or thiazide diuretic are commonly prescribed.14

For the treatment of elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in women who have not had a cardiovascular event, statin therapy is often warranted when both the LDL cholesterol is >100 mg/dL and the woman has a calculated 10-year risk of >10% for a cardiovascular event using the American Heart Association or American College of Cardiology calculator. Most women who meet these criteria will be older than age 40 years and many will be under the care of an internal medicine or family medicine specialist, limiting the role of the ObGyn.15-17

For prevention of diabetes in women with a history of GDM, both weight loss and metformin (1,750 mg daily) have been shown in clinical trials to reduce the risk of developing T2DM.18 Among 350 women with a history of GDM who were followed for 10 years, metformin 850 mg twice daily reduced the risk of developing T2DM by 40% compared with placebo.19 In the same study, lifestyle changes without metformin, including loss of 7% of body weight plus 150 minutes of exercise weekly was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk of developing T2DM.19 Metformin is one of the least expensive prescription medications and is cost-effective for the prevention of T2DM.18

Low-dose aspirin treatment for the prevention of CVD in women who have not had a cardiovascular event must balance a modest reduction in cardiovascular events with a small increased risk of bleeding events. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends low-dose aspirin for a limited group of women, those aged 50 to 59 years of age with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event >10% who are willing to take aspirin for 10 years. The USPSTF concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend low-dose aspirin prevention of CVD in women aged <50 years.20

Continue to: Beyond the fourth trimester...

Beyond the fourth trimester

The fourth trimester is the 12-week period following birth. At the comprehensive postpartum visit, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women with APOs be counseled about their increased lifetime risk of maternal cardiometabolic disease.21 In addition, ACOG recommends that at this visit the clinician who will assume primary responsibility for the woman’s ongoing medical care in her primary medical home be clarified. One option is to ensure a high-quality hand-off to an internal medicine or family medicine clinician. Another option is for a clinician in the ObGyn’s office practice, including a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or office-based ObGyn, to assume some role in the primary care of the woman.

An APO is not only a pregnancy problem

An APO reverberates across a woman’s lifetime, increasing the risk of CVD and diabetes. In the United States the mean age at first birth is 27 years.1 The mean life expectancy of US women is 81 years.22 Following a birth complicated by an APO there are 5 decades of opportunity to improve health through lifestyle changes and medication treatment of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, thereby reducing the risk of CVD.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2019. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;70:1-51.

- Deputy NP, Kim SY, Conrey EJ, et al. Prevalence and changes in preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes among women who had a live birth—United States, 2012-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1201-1207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6743a2.

- Fingar KR, Mabry-Hernandez I, Ngo-Metzger Q, et al. Delivery hospitalizations involving preeclampsia and eclampsia, 2005–2014. Statistical brief #222. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD; April 2017.

- Magnus MC, Wilcox AJ, Morken NH, et al. Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register-based study. BMJ. 2019;364:869.

- Parikh NI, Gonzalez JM, Anderson CAM, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and cardiovascular disease risk: unique opportunities for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2021;143:e902-e916. doi: 10.1161 /CIR.0000000000000961.

- Brown MC, Best KE, Pearce MS, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28:1-19. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013- 9762-6.

- Groenfol TK, Zoet GA, Franx A, et al; on behalf of the PREVENT Group. Trajectory of cardiovascular risk factors after hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertension. 2019;73:171-178. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11726.

- Vounzoulaki E, Khunti K, Abner SC, et al. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1361.

- Tarrant M, Chooniedass R, Fan HSL, et al. Breastfeeding and postpartum glucose regulation among women with prior gestational diabetes: a systematic review. J Hum Lact. 2020;36:723-738. doi: 10.1177/0890334420950259.

- Park S, Choi NK. Breastfeeding and maternal hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31:615-621. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpx219.

- Nguyen B, Gale J, Nassar N, et al. Breastfeeding and cardiovascular disease hospitalization and mortality in parous women: evidence from a large Australian cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011056. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011056.

- Eight things you can do to prevent heart disease and stroke. American Heart Association website. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living /healthy-lifestyle/prevent-heart-disease-andstroke. Last Reviewed March 14, 2019. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- ASCVD risk estimator plus. American College of Cardiology website. https://tools.acc.org /ascvd-risk-estimator-plus/#!/calculate /estimate/. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. Management of essential hypertension. Cardiol Clin. 2017;35:231-246. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2016.12.005.

- Packard CJ. LDL cholesterol: how low to go? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28:348-354. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.12.011.

- Simons L. An updated review of lipid-modifying therapy. Med J Aust. 2019;211:87-92. doi: 10.5694 /mja2.50142.

- Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, et al. Statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15629.

- Moin T, Schmittdiel JA, Flory JH, et al. Review of metformin use for type 2 diabetes mellitus prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:565-574. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.038.

- Aorda VR, Christophi CA, Edelstein SL, et al, for the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The effect of lifestyle intervention and metformin on preventing or delaying diabetes among women with and without gestational diabetes: the Diabetes Prevention Program outcomes study 10-year follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:1646- 1653. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3761.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use of the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Int Med. 2016; 164: 836-845. doi: 10.7326/M16-0577.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000002633.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2017: Table 015. Hyattsville, MD; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data /hus/2017/015.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2021.

Preconception health influences pregnancy outcomes, and in turn, both preconception health and an APO influence adult cardiometabolic health (FIGURE). This editorial is focused on the link between APOs and later cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality, recognizing that preconception health greatly influences the risk of an APO and lifetime cardiometabolic disease.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

Major APOs include miscarriage, preterm birth (birth <37 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (birth weight ≤2,500 g; 5.5 lb), gestational diabetes (GDM), preeclampsia, and placental abruption. In the United States, among all births, reported rates of the following APOs are:1-3

- preterm birth, 10.2%

- low birth weight, 8.3%

- GDM, 6%

- preeclampsia, 5%

- placental abruption, 1%.

Miscarriage occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of pregnancies, influenced by both the age of the woman and the method used to diagnose pregnancy.4 Miscarriage, preterm birth, low birth weight, GDM, preeclampsia, and placental abruption have been reported to be associated with an increased risk of later cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

APOs and cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) affects the majority of people past the age of 60 years and includes 4 major subcategories:

- coronary heart disease, including myocardial infarction, angina, and heart failure

- CVD, stroke, and transient ischemic attack

- peripheral artery disease

- atherosclerosis of the aorta leading to aortic aneurysm.

Multiple meta-analyses report that APOs are associated with CVD in later life. A comprehensive review reported that the risk of CVD was increased following a pregnancy with one of these APOs: severe preeclampsia (odds ratio [OR], 2.74), GDM (OR, 1.68), preterm birth (OR, 1.93), low birth weight (OR, 1.29), and placental abruption (OR, 1.82).5

The link between APOs and CVD may be explained in part by the association of APOs with multiple risk factors for CVD, including chronic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and dyslipidemia. A meta-analysis of 43 studies reported that, compared with controls, women with a history of preeclampsia have a 3.13 times greater risk of developing chronic hypertension.6 Among women with preeclampsia, approximately 20% will develop hypertension within 15 years.7 A meta-analysis of 20 studies reported that women with a history of GDM had a 9.51-times greater risk of developing T2DM than women without GDM.8 Among women with a history of GDM, over 16 years of follow-up, T2DM was diagnosed in 16.2%, compared with 1.9% of control women.8

CVD prevention—Breastfeeding: An antidote for APOs

Pregnancy stresses both the cardiovascular and metabolic systems. Breastfeeding is an antidote to the stresses imposed by pregnancy. Breastfeeding women have lower blood glucose9 and blood pressure.10

Breastfeeding reduces the risk of CVD. In a study of 100,864 parous Australian women, with a mean age of 60 years, ever breastfeeding was associated a lower risk of CVD hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–0.96; P = .005) and CVD mortality (aHR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49–0.89; P = .006).11

Continue to: CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations...

CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations

The American Heart Association12 recommends lifestyle interventions to reduce the risk of CVD, including:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Live a tobacco- and nicotine-free life.

- Strive to maintain a normal body mass index.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

- After 40 years of age calculate CVD risk using a validated calculator such as the American Cardiology Association risk calculator.13 This calculator uses age, gender, and lipid and blood pressure measurements to calculate the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic CVD, including coronary death, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

Medications to reduce CVD risk

Historically, ObGyns have not routinely prescribed medications to treat hypertension, dyslipidemia, or to prevent diabetes. The recent increase in the valuation of return ambulatory visits and a reduction in the valuation assigned to procedural care may provide ObGyn practices the additional resources needed to manage some chronic diseases. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners may help ObGyn practices to manage hypertension, dyslipidemia, and prediabetes.

Prior to initiating a medicine, counseling about healthy living, including smoking cessation, exercise, heart-healthy diet, and achieving an optimal body mass index is warranted.

For treatment of stage II hypertension, defined as blood pressure (BP) measurements with systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, therapeutic lifestyle interventions include: optimizing weight, following the DASH diet, restricting dietary sodium, physical activity, and reducing alcohol consumption. Medication treatment for essential hypertension is guided by the magnitude of BP reduction needed to achieve normotension. For women with hypertension needing antihypertensive medication and planning another pregnancy in the near future, labetalol or extended-release nifedipine may be first-line medications. For women who have completed their families or who have no immediate plans for pregnancy, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker, or thiazide diuretic are commonly prescribed.14

For the treatment of elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in women who have not had a cardiovascular event, statin therapy is often warranted when both the LDL cholesterol is >100 mg/dL and the woman has a calculated 10-year risk of >10% for a cardiovascular event using the American Heart Association or American College of Cardiology calculator. Most women who meet these criteria will be older than age 40 years and many will be under the care of an internal medicine or family medicine specialist, limiting the role of the ObGyn.15-17

For prevention of diabetes in women with a history of GDM, both weight loss and metformin (1,750 mg daily) have been shown in clinical trials to reduce the risk of developing T2DM.18 Among 350 women with a history of GDM who were followed for 10 years, metformin 850 mg twice daily reduced the risk of developing T2DM by 40% compared with placebo.19 In the same study, lifestyle changes without metformin, including loss of 7% of body weight plus 150 minutes of exercise weekly was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk of developing T2DM.19 Metformin is one of the least expensive prescription medications and is cost-effective for the prevention of T2DM.18

Low-dose aspirin treatment for the prevention of CVD in women who have not had a cardiovascular event must balance a modest reduction in cardiovascular events with a small increased risk of bleeding events. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends low-dose aspirin for a limited group of women, those aged 50 to 59 years of age with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event >10% who are willing to take aspirin for 10 years. The USPSTF concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend low-dose aspirin prevention of CVD in women aged <50 years.20

Continue to: Beyond the fourth trimester...

Beyond the fourth trimester

The fourth trimester is the 12-week period following birth. At the comprehensive postpartum visit, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women with APOs be counseled about their increased lifetime risk of maternal cardiometabolic disease.21 In addition, ACOG recommends that at this visit the clinician who will assume primary responsibility for the woman’s ongoing medical care in her primary medical home be clarified. One option is to ensure a high-quality hand-off to an internal medicine or family medicine clinician. Another option is for a clinician in the ObGyn’s office practice, including a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or office-based ObGyn, to assume some role in the primary care of the woman.

An APO is not only a pregnancy problem

An APO reverberates across a woman’s lifetime, increasing the risk of CVD and diabetes. In the United States the mean age at first birth is 27 years.1 The mean life expectancy of US women is 81 years.22 Following a birth complicated by an APO there are 5 decades of opportunity to improve health through lifestyle changes and medication treatment of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, thereby reducing the risk of CVD.

Preconception health influences pregnancy outcomes, and in turn, both preconception health and an APO influence adult cardiometabolic health (FIGURE). This editorial is focused on the link between APOs and later cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality, recognizing that preconception health greatly influences the risk of an APO and lifetime cardiometabolic disease.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

Major APOs include miscarriage, preterm birth (birth <37 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (birth weight ≤2,500 g; 5.5 lb), gestational diabetes (GDM), preeclampsia, and placental abruption. In the United States, among all births, reported rates of the following APOs are:1-3

- preterm birth, 10.2%

- low birth weight, 8.3%

- GDM, 6%

- preeclampsia, 5%

- placental abruption, 1%.

Miscarriage occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of pregnancies, influenced by both the age of the woman and the method used to diagnose pregnancy.4 Miscarriage, preterm birth, low birth weight, GDM, preeclampsia, and placental abruption have been reported to be associated with an increased risk of later cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

APOs and cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) affects the majority of people past the age of 60 years and includes 4 major subcategories:

- coronary heart disease, including myocardial infarction, angina, and heart failure

- CVD, stroke, and transient ischemic attack

- peripheral artery disease

- atherosclerosis of the aorta leading to aortic aneurysm.

Multiple meta-analyses report that APOs are associated with CVD in later life. A comprehensive review reported that the risk of CVD was increased following a pregnancy with one of these APOs: severe preeclampsia (odds ratio [OR], 2.74), GDM (OR, 1.68), preterm birth (OR, 1.93), low birth weight (OR, 1.29), and placental abruption (OR, 1.82).5

The link between APOs and CVD may be explained in part by the association of APOs with multiple risk factors for CVD, including chronic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and dyslipidemia. A meta-analysis of 43 studies reported that, compared with controls, women with a history of preeclampsia have a 3.13 times greater risk of developing chronic hypertension.6 Among women with preeclampsia, approximately 20% will develop hypertension within 15 years.7 A meta-analysis of 20 studies reported that women with a history of GDM had a 9.51-times greater risk of developing T2DM than women without GDM.8 Among women with a history of GDM, over 16 years of follow-up, T2DM was diagnosed in 16.2%, compared with 1.9% of control women.8

CVD prevention—Breastfeeding: An antidote for APOs

Pregnancy stresses both the cardiovascular and metabolic systems. Breastfeeding is an antidote to the stresses imposed by pregnancy. Breastfeeding women have lower blood glucose9 and blood pressure.10

Breastfeeding reduces the risk of CVD. In a study of 100,864 parous Australian women, with a mean age of 60 years, ever breastfeeding was associated a lower risk of CVD hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–0.96; P = .005) and CVD mortality (aHR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49–0.89; P = .006).11

Continue to: CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations...

CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations

The American Heart Association12 recommends lifestyle interventions to reduce the risk of CVD, including:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Live a tobacco- and nicotine-free life.

- Strive to maintain a normal body mass index.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

- After 40 years of age calculate CVD risk using a validated calculator such as the American Cardiology Association risk calculator.13 This calculator uses age, gender, and lipid and blood pressure measurements to calculate the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic CVD, including coronary death, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

Medications to reduce CVD risk

Historically, ObGyns have not routinely prescribed medications to treat hypertension, dyslipidemia, or to prevent diabetes. The recent increase in the valuation of return ambulatory visits and a reduction in the valuation assigned to procedural care may provide ObGyn practices the additional resources needed to manage some chronic diseases. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners may help ObGyn practices to manage hypertension, dyslipidemia, and prediabetes.

Prior to initiating a medicine, counseling about healthy living, including smoking cessation, exercise, heart-healthy diet, and achieving an optimal body mass index is warranted.

For treatment of stage II hypertension, defined as blood pressure (BP) measurements with systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, therapeutic lifestyle interventions include: optimizing weight, following the DASH diet, restricting dietary sodium, physical activity, and reducing alcohol consumption. Medication treatment for essential hypertension is guided by the magnitude of BP reduction needed to achieve normotension. For women with hypertension needing antihypertensive medication and planning another pregnancy in the near future, labetalol or extended-release nifedipine may be first-line medications. For women who have completed their families or who have no immediate plans for pregnancy, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker, or thiazide diuretic are commonly prescribed.14

For the treatment of elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in women who have not had a cardiovascular event, statin therapy is often warranted when both the LDL cholesterol is >100 mg/dL and the woman has a calculated 10-year risk of >10% for a cardiovascular event using the American Heart Association or American College of Cardiology calculator. Most women who meet these criteria will be older than age 40 years and many will be under the care of an internal medicine or family medicine specialist, limiting the role of the ObGyn.15-17

For prevention of diabetes in women with a history of GDM, both weight loss and metformin (1,750 mg daily) have been shown in clinical trials to reduce the risk of developing T2DM.18 Among 350 women with a history of GDM who were followed for 10 years, metformin 850 mg twice daily reduced the risk of developing T2DM by 40% compared with placebo.19 In the same study, lifestyle changes without metformin, including loss of 7% of body weight plus 150 minutes of exercise weekly was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk of developing T2DM.19 Metformin is one of the least expensive prescription medications and is cost-effective for the prevention of T2DM.18

Low-dose aspirin treatment for the prevention of CVD in women who have not had a cardiovascular event must balance a modest reduction in cardiovascular events with a small increased risk of bleeding events. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends low-dose aspirin for a limited group of women, those aged 50 to 59 years of age with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event >10% who are willing to take aspirin for 10 years. The USPSTF concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend low-dose aspirin prevention of CVD in women aged <50 years.20

Continue to: Beyond the fourth trimester...

Beyond the fourth trimester

The fourth trimester is the 12-week period following birth. At the comprehensive postpartum visit, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women with APOs be counseled about their increased lifetime risk of maternal cardiometabolic disease.21 In addition, ACOG recommends that at this visit the clinician who will assume primary responsibility for the woman’s ongoing medical care in her primary medical home be clarified. One option is to ensure a high-quality hand-off to an internal medicine or family medicine clinician. Another option is for a clinician in the ObGyn’s office practice, including a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or office-based ObGyn, to assume some role in the primary care of the woman.

An APO is not only a pregnancy problem

An APO reverberates across a woman’s lifetime, increasing the risk of CVD and diabetes. In the United States the mean age at first birth is 27 years.1 The mean life expectancy of US women is 81 years.22 Following a birth complicated by an APO there are 5 decades of opportunity to improve health through lifestyle changes and medication treatment of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, thereby reducing the risk of CVD.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2019. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;70:1-51.

- Deputy NP, Kim SY, Conrey EJ, et al. Prevalence and changes in preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes among women who had a live birth—United States, 2012-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1201-1207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6743a2.

- Fingar KR, Mabry-Hernandez I, Ngo-Metzger Q, et al. Delivery hospitalizations involving preeclampsia and eclampsia, 2005–2014. Statistical brief #222. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD; April 2017.

- Magnus MC, Wilcox AJ, Morken NH, et al. Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register-based study. BMJ. 2019;364:869.

- Parikh NI, Gonzalez JM, Anderson CAM, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and cardiovascular disease risk: unique opportunities for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2021;143:e902-e916. doi: 10.1161 /CIR.0000000000000961.

- Brown MC, Best KE, Pearce MS, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28:1-19. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013- 9762-6.

- Groenfol TK, Zoet GA, Franx A, et al; on behalf of the PREVENT Group. Trajectory of cardiovascular risk factors after hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertension. 2019;73:171-178. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11726.

- Vounzoulaki E, Khunti K, Abner SC, et al. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1361.

- Tarrant M, Chooniedass R, Fan HSL, et al. Breastfeeding and postpartum glucose regulation among women with prior gestational diabetes: a systematic review. J Hum Lact. 2020;36:723-738. doi: 10.1177/0890334420950259.

- Park S, Choi NK. Breastfeeding and maternal hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31:615-621. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpx219.

- Nguyen B, Gale J, Nassar N, et al. Breastfeeding and cardiovascular disease hospitalization and mortality in parous women: evidence from a large Australian cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011056. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011056.

- Eight things you can do to prevent heart disease and stroke. American Heart Association website. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living /healthy-lifestyle/prevent-heart-disease-andstroke. Last Reviewed March 14, 2019. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- ASCVD risk estimator plus. American College of Cardiology website. https://tools.acc.org /ascvd-risk-estimator-plus/#!/calculate /estimate/. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. Management of essential hypertension. Cardiol Clin. 2017;35:231-246. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2016.12.005.

- Packard CJ. LDL cholesterol: how low to go? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28:348-354. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.12.011.

- Simons L. An updated review of lipid-modifying therapy. Med J Aust. 2019;211:87-92. doi: 10.5694 /mja2.50142.

- Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, et al. Statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15629.

- Moin T, Schmittdiel JA, Flory JH, et al. Review of metformin use for type 2 diabetes mellitus prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:565-574. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.038.

- Aorda VR, Christophi CA, Edelstein SL, et al, for the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The effect of lifestyle intervention and metformin on preventing or delaying diabetes among women with and without gestational diabetes: the Diabetes Prevention Program outcomes study 10-year follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:1646- 1653. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3761.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use of the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Int Med. 2016; 164: 836-845. doi: 10.7326/M16-0577.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000002633.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2017: Table 015. Hyattsville, MD; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data /hus/2017/015.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2021.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2019. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;70:1-51.

- Deputy NP, Kim SY, Conrey EJ, et al. Prevalence and changes in preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes among women who had a live birth—United States, 2012-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1201-1207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6743a2.

- Fingar KR, Mabry-Hernandez I, Ngo-Metzger Q, et al. Delivery hospitalizations involving preeclampsia and eclampsia, 2005–2014. Statistical brief #222. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD; April 2017.

- Magnus MC, Wilcox AJ, Morken NH, et al. Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register-based study. BMJ. 2019;364:869.

- Parikh NI, Gonzalez JM, Anderson CAM, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and cardiovascular disease risk: unique opportunities for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2021;143:e902-e916. doi: 10.1161 /CIR.0000000000000961.

- Brown MC, Best KE, Pearce MS, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28:1-19. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013- 9762-6.

- Groenfol TK, Zoet GA, Franx A, et al; on behalf of the PREVENT Group. Trajectory of cardiovascular risk factors after hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertension. 2019;73:171-178. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11726.

- Vounzoulaki E, Khunti K, Abner SC, et al. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1361.

- Tarrant M, Chooniedass R, Fan HSL, et al. Breastfeeding and postpartum glucose regulation among women with prior gestational diabetes: a systematic review. J Hum Lact. 2020;36:723-738. doi: 10.1177/0890334420950259.

- Park S, Choi NK. Breastfeeding and maternal hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31:615-621. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpx219.

- Nguyen B, Gale J, Nassar N, et al. Breastfeeding and cardiovascular disease hospitalization and mortality in parous women: evidence from a large Australian cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011056. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011056.

- Eight things you can do to prevent heart disease and stroke. American Heart Association website. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living /healthy-lifestyle/prevent-heart-disease-andstroke. Last Reviewed March 14, 2019. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- ASCVD risk estimator plus. American College of Cardiology website. https://tools.acc.org /ascvd-risk-estimator-plus/#!/calculate /estimate/. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. Management of essential hypertension. Cardiol Clin. 2017;35:231-246. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2016.12.005.

- Packard CJ. LDL cholesterol: how low to go? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28:348-354. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.12.011.

- Simons L. An updated review of lipid-modifying therapy. Med J Aust. 2019;211:87-92. doi: 10.5694 /mja2.50142.

- Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, et al. Statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15629.

- Moin T, Schmittdiel JA, Flory JH, et al. Review of metformin use for type 2 diabetes mellitus prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:565-574. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.038.

- Aorda VR, Christophi CA, Edelstein SL, et al, for the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The effect of lifestyle intervention and metformin on preventing or delaying diabetes among women with and without gestational diabetes: the Diabetes Prevention Program outcomes study 10-year follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:1646- 1653. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3761.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use of the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Int Med. 2016; 164: 836-845. doi: 10.7326/M16-0577.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000002633.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2017: Table 015. Hyattsville, MD; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data /hus/2017/015.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2021.

Pilot study: Hybrid laser found effective for treating genitourinary syndrome of menopause

, results from a pilot trial showed.

“The genitourinary syndrome of menopause causes suffering in breast cancer survivors and postmenopausal women,” Jill S. Waibel, MD, said during the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. A common side effect for breast cancer survivors is early onset of menopause that is brought on by treatment, specifically aromatase-inhibitor therapies, she noted.

The symptoms of GSM include discomfort during sex, impaired sexual function, burning or sensation or irritation of the genital area, vaginal constriction, frequent urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, and vaginal laxity, said Dr. Waibel, owner and medical director of the Miami Dermatology and Laser Institute. Nonhormonal treatments have included OTC vaginal lubricants, OTC moisturizers, low-dose vaginal estrogen – which increases the risk of breast cancer – and systemic estrogen therapy, which also can increase the risk of breast and endometrial cancer. “So, we need a healthy, nondrug option,” she said.

The objective of the pilot study was to determine the safety and efficacy of the diVa hybrid fractional laser as a treatment for symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause, early menopause after breast cancer, or vaginal atrophy. The laser applies tunable nonablative (1,470-nm) and ablative (2,940-nm) wavelengths to the same microscopic treatment zone to maximize results and reduce downtime. The device features a motorized precision guidance system and calibrated rotation for homogeneous pulsing.

“The 2,940-nm wavelength is used to ablate to a depth of 0-800 micrometers while the 1,470-nm wavelength is used to coagulate the epithelium and the lamina propria at a depth of 100-700 micrometers,” said Dr. Waibel, who is also subsection chief of dermatology at Baptist Hospital of Miami. “This combination is used for epithelial tissue to heal quickly and the lamina propria to remodel slowly over time, laying down more collagen in tissue.” Each procedure is delivered via a single-use dilator, which expands the vaginal canal for increased treatment area. “The tip length is 5.5 cm and the diameter is 1 cm,” she said. “The clear tip acts as a hygienic barrier between the tip and the handpiece.”

Study participants included 25 women between the ages of 40 and 70 with early menopause after breast cancer or vaginal atrophy: 20 in the treatment arm and 5 in the sham-treatment arm. Dr. Waibel performed three procedures 2 weeks apart. An ob.gyn. assessed the primary endpoints, which included the Vaginal Health Index Scale (VHIS), the Vaginal Maturation Index (VMI), the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) questionnaire, and the Day-to-Day Impact of Vaginal Aging (DIVA) questionnaire. Secondary endpoints were histology and a satisfaction questionnaire.

Of the women in the treated group, there were data available for 19 at 3 months follow-up and 17 at 6 months follow-up. Based on the results in these patients, there were statistically significant improvements in nearly all domains of the FSFI treatment arm at 3 and 6 months when compared to baseline, especially arousal (P values of .05 at 3 months and .01 at 6 months) and lubrication (P values of .009 at three months and .001 at 6 months).

Between 3 and 6 months, patients in the treatment arm experienced improvements in four dimensions of the DIVA questionnaire: daily activities (P value of .01 at 3 months to .010 at 6 months), emotional well-being (P value of .06 at 3 months to .014 at 6 months), sexual function (P value of .30 at 3 months to .003 at 6 months), and self-concept/body image (P value of .002 at 3 months to .001 at 6 months).

As for satisfaction, a majority of those in the treatment arm were “somewhat satisfied” with the treatment and would “somewhat likely” repeat and recommend the treatment to friends and family, Dr. Waibel said. Results among the women in the control arm, who were also surveyed, were in the similar range, she noted. (No other results for women in the control arm were available.)

Following treatments, histology revealed that the collagen was denser, fibroblasts were more dense, and vascularity was more notable. No adverse events were observed. “The hybrid fractional laser is safe and effective for treating GSM, early menopause after breast cancer, or vaginal atrophy,” Dr. Waibel concluded. Further studies are important to improve the understanding of “laser dosimetry, frequency of treatments, and longevity of effect. Collaboration between ob.gyns. and dermatologists is important as we learn about laser therapy in GSM.”

Dr. Waibel disclosed that she is a member of the advisory board of Sciton, which manufactures the diVa laser. She has also conducted clinical trials for many other device and pharmaceutical companies.

, results from a pilot trial showed.

“The genitourinary syndrome of menopause causes suffering in breast cancer survivors and postmenopausal women,” Jill S. Waibel, MD, said during the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. A common side effect for breast cancer survivors is early onset of menopause that is brought on by treatment, specifically aromatase-inhibitor therapies, she noted.

The symptoms of GSM include discomfort during sex, impaired sexual function, burning or sensation or irritation of the genital area, vaginal constriction, frequent urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, and vaginal laxity, said Dr. Waibel, owner and medical director of the Miami Dermatology and Laser Institute. Nonhormonal treatments have included OTC vaginal lubricants, OTC moisturizers, low-dose vaginal estrogen – which increases the risk of breast cancer – and systemic estrogen therapy, which also can increase the risk of breast and endometrial cancer. “So, we need a healthy, nondrug option,” she said.

The objective of the pilot study was to determine the safety and efficacy of the diVa hybrid fractional laser as a treatment for symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause, early menopause after breast cancer, or vaginal atrophy. The laser applies tunable nonablative (1,470-nm) and ablative (2,940-nm) wavelengths to the same microscopic treatment zone to maximize results and reduce downtime. The device features a motorized precision guidance system and calibrated rotation for homogeneous pulsing.

“The 2,940-nm wavelength is used to ablate to a depth of 0-800 micrometers while the 1,470-nm wavelength is used to coagulate the epithelium and the lamina propria at a depth of 100-700 micrometers,” said Dr. Waibel, who is also subsection chief of dermatology at Baptist Hospital of Miami. “This combination is used for epithelial tissue to heal quickly and the lamina propria to remodel slowly over time, laying down more collagen in tissue.” Each procedure is delivered via a single-use dilator, which expands the vaginal canal for increased treatment area. “The tip length is 5.5 cm and the diameter is 1 cm,” she said. “The clear tip acts as a hygienic barrier between the tip and the handpiece.”

Study participants included 25 women between the ages of 40 and 70 with early menopause after breast cancer or vaginal atrophy: 20 in the treatment arm and 5 in the sham-treatment arm. Dr. Waibel performed three procedures 2 weeks apart. An ob.gyn. assessed the primary endpoints, which included the Vaginal Health Index Scale (VHIS), the Vaginal Maturation Index (VMI), the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) questionnaire, and the Day-to-Day Impact of Vaginal Aging (DIVA) questionnaire. Secondary endpoints were histology and a satisfaction questionnaire.

Of the women in the treated group, there were data available for 19 at 3 months follow-up and 17 at 6 months follow-up. Based on the results in these patients, there were statistically significant improvements in nearly all domains of the FSFI treatment arm at 3 and 6 months when compared to baseline, especially arousal (P values of .05 at 3 months and .01 at 6 months) and lubrication (P values of .009 at three months and .001 at 6 months).

Between 3 and 6 months, patients in the treatment arm experienced improvements in four dimensions of the DIVA questionnaire: daily activities (P value of .01 at 3 months to .010 at 6 months), emotional well-being (P value of .06 at 3 months to .014 at 6 months), sexual function (P value of .30 at 3 months to .003 at 6 months), and self-concept/body image (P value of .002 at 3 months to .001 at 6 months).

As for satisfaction, a majority of those in the treatment arm were “somewhat satisfied” with the treatment and would “somewhat likely” repeat and recommend the treatment to friends and family, Dr. Waibel said. Results among the women in the control arm, who were also surveyed, were in the similar range, she noted. (No other results for women in the control arm were available.)

Following treatments, histology revealed that the collagen was denser, fibroblasts were more dense, and vascularity was more notable. No adverse events were observed. “The hybrid fractional laser is safe and effective for treating GSM, early menopause after breast cancer, or vaginal atrophy,” Dr. Waibel concluded. Further studies are important to improve the understanding of “laser dosimetry, frequency of treatments, and longevity of effect. Collaboration between ob.gyns. and dermatologists is important as we learn about laser therapy in GSM.”

Dr. Waibel disclosed that she is a member of the advisory board of Sciton, which manufactures the diVa laser. She has also conducted clinical trials for many other device and pharmaceutical companies.

, results from a pilot trial showed.

“The genitourinary syndrome of menopause causes suffering in breast cancer survivors and postmenopausal women,” Jill S. Waibel, MD, said during the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. A common side effect for breast cancer survivors is early onset of menopause that is brought on by treatment, specifically aromatase-inhibitor therapies, she noted.

The symptoms of GSM include discomfort during sex, impaired sexual function, burning or sensation or irritation of the genital area, vaginal constriction, frequent urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, and vaginal laxity, said Dr. Waibel, owner and medical director of the Miami Dermatology and Laser Institute. Nonhormonal treatments have included OTC vaginal lubricants, OTC moisturizers, low-dose vaginal estrogen – which increases the risk of breast cancer – and systemic estrogen therapy, which also can increase the risk of breast and endometrial cancer. “So, we need a healthy, nondrug option,” she said.

The objective of the pilot study was to determine the safety and efficacy of the diVa hybrid fractional laser as a treatment for symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause, early menopause after breast cancer, or vaginal atrophy. The laser applies tunable nonablative (1,470-nm) and ablative (2,940-nm) wavelengths to the same microscopic treatment zone to maximize results and reduce downtime. The device features a motorized precision guidance system and calibrated rotation for homogeneous pulsing.

“The 2,940-nm wavelength is used to ablate to a depth of 0-800 micrometers while the 1,470-nm wavelength is used to coagulate the epithelium and the lamina propria at a depth of 100-700 micrometers,” said Dr. Waibel, who is also subsection chief of dermatology at Baptist Hospital of Miami. “This combination is used for epithelial tissue to heal quickly and the lamina propria to remodel slowly over time, laying down more collagen in tissue.” Each procedure is delivered via a single-use dilator, which expands the vaginal canal for increased treatment area. “The tip length is 5.5 cm and the diameter is 1 cm,” she said. “The clear tip acts as a hygienic barrier between the tip and the handpiece.”

Study participants included 25 women between the ages of 40 and 70 with early menopause after breast cancer or vaginal atrophy: 20 in the treatment arm and 5 in the sham-treatment arm. Dr. Waibel performed three procedures 2 weeks apart. An ob.gyn. assessed the primary endpoints, which included the Vaginal Health Index Scale (VHIS), the Vaginal Maturation Index (VMI), the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) questionnaire, and the Day-to-Day Impact of Vaginal Aging (DIVA) questionnaire. Secondary endpoints were histology and a satisfaction questionnaire.

Of the women in the treated group, there were data available for 19 at 3 months follow-up and 17 at 6 months follow-up. Based on the results in these patients, there were statistically significant improvements in nearly all domains of the FSFI treatment arm at 3 and 6 months when compared to baseline, especially arousal (P values of .05 at 3 months and .01 at 6 months) and lubrication (P values of .009 at three months and .001 at 6 months).

Between 3 and 6 months, patients in the treatment arm experienced improvements in four dimensions of the DIVA questionnaire: daily activities (P value of .01 at 3 months to .010 at 6 months), emotional well-being (P value of .06 at 3 months to .014 at 6 months), sexual function (P value of .30 at 3 months to .003 at 6 months), and self-concept/body image (P value of .002 at 3 months to .001 at 6 months).

As for satisfaction, a majority of those in the treatment arm were “somewhat satisfied” with the treatment and would “somewhat likely” repeat and recommend the treatment to friends and family, Dr. Waibel said. Results among the women in the control arm, who were also surveyed, were in the similar range, she noted. (No other results for women in the control arm were available.)

Following treatments, histology revealed that the collagen was denser, fibroblasts were more dense, and vascularity was more notable. No adverse events were observed. “The hybrid fractional laser is safe and effective for treating GSM, early menopause after breast cancer, or vaginal atrophy,” Dr. Waibel concluded. Further studies are important to improve the understanding of “laser dosimetry, frequency of treatments, and longevity of effect. Collaboration between ob.gyns. and dermatologists is important as we learn about laser therapy in GSM.”

Dr. Waibel disclosed that she is a member of the advisory board of Sciton, which manufactures the diVa laser. She has also conducted clinical trials for many other device and pharmaceutical companies.

FROM ASLMS 2021

Air pollution linked to increased fibroid risk in Black women

Black women exposed to ozone air pollution have an increased risk of developing fibroids, according to new research published in Human Production.

Uterine fibroids are a common type of pelvic growth, affecting up to 80% of women by the time they reach age 50, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Black women are hit hardest by fibroids; they are diagnosed two to three times the rate of White women and tend to have more severe symptoms.

Researchers are unclear on why exposure to ozone air pollution increases the risk of developing fibroids. However, they believe that when it comes to identifying causes of fibroids and explanations for racial disparities in fibroids, more research that focuses on environmental and neighborhood-level risk factors could help inform policy and interventions to improve gynecologic health.

“A large body of literature from the environmental justice field has documented that people of color, and Black people specifically, are inequitably exposed to air pollution,” study author Amelia K. Wesselink, PhD, assistant professor at Boston University School of Public Health, said in an interview. “And there is growing evidence that air pollution can influence gynecologic health and therefore may contribute to racial disparities in gynecologic outcomes.”

Dr. Wesselink and colleagues wanted to know the extent to which three air pollutants – particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and ozone (03) – were linked to the development of fibroids. To figure this out, they analyzed data on nearly 22,000 premenopausal Black women who lived in 56 metropolitan areas in the United States between 2007 and 2011. They assigned air pollution exposures to participants’ residential addresses collected at baseline and over follow-up and tried to capture long-term exposure to air pollutants.

During the study, nearly 30% of participants reported that they were diagnosed with fibroids. Researchers observed that the exposure to PM2.5 and NO2 was not associated with an increased risk of developing these fibroids.

Dr. Wesselink said the findings may have underestimated fibroid incidence, so they “need to be replicated in a prospective, ultrasound-based study that can identify all fibroid cases.”

“There has not been a lot of research on how air pollution influences fibroid risk, but the two studies that are out there show some evidence of an association,” said Dr. Wesselink. “The fact that our results were consistent with this is interesting. The surprising part of our findings was that we observed an association for ozone, but not for PM2.5 or NO2.”

Nathaniel DeNicola, MD, MSHP, FACOG, a Washington-based obstetrics and gynecology physician affiliated with John Hopkins Health System, applauded the methodology of the study and said the findings prove that patients and doctors should be talking about the environment and exposures to air pollutants.

“[Air pollution] has numerous components to it. And we should try to figure out exactly what components are most dangerous to human health and what doses and what times of life,” said Dr. DeNicola, an environmental health expert.

The increased risk of developing fibroids is a “historical observation” and air pollution may be part of a multifactorial cause of that, Dr. DeNicola said. He said he wouldn’t be surprised if future studies show that “higher exposure [to air pollution] – due to how city planning works, often communities of color are in the areas with the most dense air pollution – exacerbates some other mechanism already in place.

Although it’s unclear how ozone exposure increases fibroid risk, Dr. Wesselink said it may be through a mechanism that is unique to ozone.

“In other words, it might be that there is a factor related to ozone that we did not account for that explains our findings. Vitamin D is a factor that we were not able to account for in this study,” Dr. Wesselink said. “Future work on this topic should consider the role of vitamin D [exposure or deficiency].”

Dr. DeNicola said ozone’s impact may also be tied to its “known association” with hypertension. A 2017 study by Drew B. Day, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues, found that ozone exposure has been linked to hypertension. Meanwhile, a 2015 study has found an association between hypertension and fibroids.

“[This study] does raise an important message. It shines a light where more research needs to be done,” Dr. DeNicola said. “The ozone connection to hypertension was probably most compelling as a true risk factor for uterine fibroids.”

Dr. Wesselink said future work on fibroid etiology should focus on environmental and neighborhood-level exposures to pollutants.

Black women exposed to ozone air pollution have an increased risk of developing fibroids, according to new research published in Human Production.

Uterine fibroids are a common type of pelvic growth, affecting up to 80% of women by the time they reach age 50, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Black women are hit hardest by fibroids; they are diagnosed two to three times the rate of White women and tend to have more severe symptoms.

Researchers are unclear on why exposure to ozone air pollution increases the risk of developing fibroids. However, they believe that when it comes to identifying causes of fibroids and explanations for racial disparities in fibroids, more research that focuses on environmental and neighborhood-level risk factors could help inform policy and interventions to improve gynecologic health.

“A large body of literature from the environmental justice field has documented that people of color, and Black people specifically, are inequitably exposed to air pollution,” study author Amelia K. Wesselink, PhD, assistant professor at Boston University School of Public Health, said in an interview. “And there is growing evidence that air pollution can influence gynecologic health and therefore may contribute to racial disparities in gynecologic outcomes.”

Dr. Wesselink and colleagues wanted to know the extent to which three air pollutants – particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and ozone (03) – were linked to the development of fibroids. To figure this out, they analyzed data on nearly 22,000 premenopausal Black women who lived in 56 metropolitan areas in the United States between 2007 and 2011. They assigned air pollution exposures to participants’ residential addresses collected at baseline and over follow-up and tried to capture long-term exposure to air pollutants.

During the study, nearly 30% of participants reported that they were diagnosed with fibroids. Researchers observed that the exposure to PM2.5 and NO2 was not associated with an increased risk of developing these fibroids.

Dr. Wesselink said the findings may have underestimated fibroid incidence, so they “need to be replicated in a prospective, ultrasound-based study that can identify all fibroid cases.”

“There has not been a lot of research on how air pollution influences fibroid risk, but the two studies that are out there show some evidence of an association,” said Dr. Wesselink. “The fact that our results were consistent with this is interesting. The surprising part of our findings was that we observed an association for ozone, but not for PM2.5 or NO2.”

Nathaniel DeNicola, MD, MSHP, FACOG, a Washington-based obstetrics and gynecology physician affiliated with John Hopkins Health System, applauded the methodology of the study and said the findings prove that patients and doctors should be talking about the environment and exposures to air pollutants.

“[Air pollution] has numerous components to it. And we should try to figure out exactly what components are most dangerous to human health and what doses and what times of life,” said Dr. DeNicola, an environmental health expert.

The increased risk of developing fibroids is a “historical observation” and air pollution may be part of a multifactorial cause of that, Dr. DeNicola said. He said he wouldn’t be surprised if future studies show that “higher exposure [to air pollution] – due to how city planning works, often communities of color are in the areas with the most dense air pollution – exacerbates some other mechanism already in place.

Although it’s unclear how ozone exposure increases fibroid risk, Dr. Wesselink said it may be through a mechanism that is unique to ozone.

“In other words, it might be that there is a factor related to ozone that we did not account for that explains our findings. Vitamin D is a factor that we were not able to account for in this study,” Dr. Wesselink said. “Future work on this topic should consider the role of vitamin D [exposure or deficiency].”

Dr. DeNicola said ozone’s impact may also be tied to its “known association” with hypertension. A 2017 study by Drew B. Day, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues, found that ozone exposure has been linked to hypertension. Meanwhile, a 2015 study has found an association between hypertension and fibroids.

“[This study] does raise an important message. It shines a light where more research needs to be done,” Dr. DeNicola said. “The ozone connection to hypertension was probably most compelling as a true risk factor for uterine fibroids.”

Dr. Wesselink said future work on fibroid etiology should focus on environmental and neighborhood-level exposures to pollutants.

Black women exposed to ozone air pollution have an increased risk of developing fibroids, according to new research published in Human Production.

Uterine fibroids are a common type of pelvic growth, affecting up to 80% of women by the time they reach age 50, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Black women are hit hardest by fibroids; they are diagnosed two to three times the rate of White women and tend to have more severe symptoms.

Researchers are unclear on why exposure to ozone air pollution increases the risk of developing fibroids. However, they believe that when it comes to identifying causes of fibroids and explanations for racial disparities in fibroids, more research that focuses on environmental and neighborhood-level risk factors could help inform policy and interventions to improve gynecologic health.

“A large body of literature from the environmental justice field has documented that people of color, and Black people specifically, are inequitably exposed to air pollution,” study author Amelia K. Wesselink, PhD, assistant professor at Boston University School of Public Health, said in an interview. “And there is growing evidence that air pollution can influence gynecologic health and therefore may contribute to racial disparities in gynecologic outcomes.”

Dr. Wesselink and colleagues wanted to know the extent to which three air pollutants – particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and ozone (03) – were linked to the development of fibroids. To figure this out, they analyzed data on nearly 22,000 premenopausal Black women who lived in 56 metropolitan areas in the United States between 2007 and 2011. They assigned air pollution exposures to participants’ residential addresses collected at baseline and over follow-up and tried to capture long-term exposure to air pollutants.

During the study, nearly 30% of participants reported that they were diagnosed with fibroids. Researchers observed that the exposure to PM2.5 and NO2 was not associated with an increased risk of developing these fibroids.

Dr. Wesselink said the findings may have underestimated fibroid incidence, so they “need to be replicated in a prospective, ultrasound-based study that can identify all fibroid cases.”

“There has not been a lot of research on how air pollution influences fibroid risk, but the two studies that are out there show some evidence of an association,” said Dr. Wesselink. “The fact that our results were consistent with this is interesting. The surprising part of our findings was that we observed an association for ozone, but not for PM2.5 or NO2.”

Nathaniel DeNicola, MD, MSHP, FACOG, a Washington-based obstetrics and gynecology physician affiliated with John Hopkins Health System, applauded the methodology of the study and said the findings prove that patients and doctors should be talking about the environment and exposures to air pollutants.

“[Air pollution] has numerous components to it. And we should try to figure out exactly what components are most dangerous to human health and what doses and what times of life,” said Dr. DeNicola, an environmental health expert.

The increased risk of developing fibroids is a “historical observation” and air pollution may be part of a multifactorial cause of that, Dr. DeNicola said. He said he wouldn’t be surprised if future studies show that “higher exposure [to air pollution] – due to how city planning works, often communities of color are in the areas with the most dense air pollution – exacerbates some other mechanism already in place.

Although it’s unclear how ozone exposure increases fibroid risk, Dr. Wesselink said it may be through a mechanism that is unique to ozone.

“In other words, it might be that there is a factor related to ozone that we did not account for that explains our findings. Vitamin D is a factor that we were not able to account for in this study,” Dr. Wesselink said. “Future work on this topic should consider the role of vitamin D [exposure or deficiency].”

Dr. DeNicola said ozone’s impact may also be tied to its “known association” with hypertension. A 2017 study by Drew B. Day, PhD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues, found that ozone exposure has been linked to hypertension. Meanwhile, a 2015 study has found an association between hypertension and fibroids.

“[This study] does raise an important message. It shines a light where more research needs to be done,” Dr. DeNicola said. “The ozone connection to hypertension was probably most compelling as a true risk factor for uterine fibroids.”

Dr. Wesselink said future work on fibroid etiology should focus on environmental and neighborhood-level exposures to pollutants.

FDA approves ibrexafungerp for vaginal yeast infection

Ibrexafungerp is the first drug approved in a new antifungal class for vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) in more than 20 years, the drug’s manufacturer Scynexis said in a press release. It becomes the first and only nonazole treatment for vaginal yeast infections.

The biotechnology company said approval came after positive results from two phase 3 studies in which oral ibrexafungerp demonstrated efficacy and tolerability. The most common reactions observed in clinical trials were diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, dizziness, and vomiting.

There are few other treatments for vaginal yeast infections, which is the second most common cause of vaginitis. Those previously approved agents include several topical azole antifungals and oral fluconazole (Diflucan), which, Scynexis said, is the only other orally administered antifungal approved for the treatment of VVC in the United States and has accounted for over more than 90% of prescriptions written for the condition each year.

However, the company noted, oral fluconazole reports a 55% therapeutic cure rate on its label, which now also includes warnings of potential fetal harm, demonstrating the need for new oral options.

The new drug may not fill that need for pregnant women, however, as the company noted that ibrexafungerp should not be used during pregnancy, and administration during pregnancy “may cause fetal harm based on animal studies.”

Because of possible teratogenic effects, the company advised clinicians to verify pregnancy status in females of reproductive potential before prescribing ibrexafungerp and advises effective contraception during treatment.

VVC can come with substantial morbidity, including genital pain, itching and burning, reduced sexual pleasure, and psychological distress.

David Angulo, MD, chief medical officer for Scynexis, said in a statement the tablets brings new benefits.

Dr. Angulo said the drug “has a differentiated fungicidal mechanism of action that kills a broad range of Candida species, including azole-resistant strains. We are working on completing our CANDLE study investigating ibrexafungerp for the prevention of recurrent VVC and expect we will be submitting a supplemental NDA [new drug application] in the first half of 2022.”

Scynexis said it partnered with Amplity Health, a Pennsylvania-based pharmaceutical company, to support U.S. marketing of the drug. The commercial launch will follow the approval.

Ibrexafungerp was granted approval through both the FDA’s Qualified Infectious Disease Product and Fast Track designations. It is expected to be marketed exclusively in the United States for 10 years.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ibrexafungerp is the first drug approved in a new antifungal class for vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) in more than 20 years, the drug’s manufacturer Scynexis said in a press release. It becomes the first and only nonazole treatment for vaginal yeast infections.

The biotechnology company said approval came after positive results from two phase 3 studies in which oral ibrexafungerp demonstrated efficacy and tolerability. The most common reactions observed in clinical trials were diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, dizziness, and vomiting.

There are few other treatments for vaginal yeast infections, which is the second most common cause of vaginitis. Those previously approved agents include several topical azole antifungals and oral fluconazole (Diflucan), which, Scynexis said, is the only other orally administered antifungal approved for the treatment of VVC in the United States and has accounted for over more than 90% of prescriptions written for the condition each year.

However, the company noted, oral fluconazole reports a 55% therapeutic cure rate on its label, which now also includes warnings of potential fetal harm, demonstrating the need for new oral options.

The new drug may not fill that need for pregnant women, however, as the company noted that ibrexafungerp should not be used during pregnancy, and administration during pregnancy “may cause fetal harm based on animal studies.”

Because of possible teratogenic effects, the company advised clinicians to verify pregnancy status in females of reproductive potential before prescribing ibrexafungerp and advises effective contraception during treatment.

VVC can come with substantial morbidity, including genital pain, itching and burning, reduced sexual pleasure, and psychological distress.

David Angulo, MD, chief medical officer for Scynexis, said in a statement the tablets brings new benefits.

Dr. Angulo said the drug “has a differentiated fungicidal mechanism of action that kills a broad range of Candida species, including azole-resistant strains. We are working on completing our CANDLE study investigating ibrexafungerp for the prevention of recurrent VVC and expect we will be submitting a supplemental NDA [new drug application] in the first half of 2022.”

Scynexis said it partnered with Amplity Health, a Pennsylvania-based pharmaceutical company, to support U.S. marketing of the drug. The commercial launch will follow the approval.

Ibrexafungerp was granted approval through both the FDA’s Qualified Infectious Disease Product and Fast Track designations. It is expected to be marketed exclusively in the United States for 10 years.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ibrexafungerp is the first drug approved in a new antifungal class for vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) in more than 20 years, the drug’s manufacturer Scynexis said in a press release. It becomes the first and only nonazole treatment for vaginal yeast infections.

The biotechnology company said approval came after positive results from two phase 3 studies in which oral ibrexafungerp demonstrated efficacy and tolerability. The most common reactions observed in clinical trials were diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, dizziness, and vomiting.

There are few other treatments for vaginal yeast infections, which is the second most common cause of vaginitis. Those previously approved agents include several topical azole antifungals and oral fluconazole (Diflucan), which, Scynexis said, is the only other orally administered antifungal approved for the treatment of VVC in the United States and has accounted for over more than 90% of prescriptions written for the condition each year.

However, the company noted, oral fluconazole reports a 55% therapeutic cure rate on its label, which now also includes warnings of potential fetal harm, demonstrating the need for new oral options.

The new drug may not fill that need for pregnant women, however, as the company noted that ibrexafungerp should not be used during pregnancy, and administration during pregnancy “may cause fetal harm based on animal studies.”

Because of possible teratogenic effects, the company advised clinicians to verify pregnancy status in females of reproductive potential before prescribing ibrexafungerp and advises effective contraception during treatment.

VVC can come with substantial morbidity, including genital pain, itching and burning, reduced sexual pleasure, and psychological distress.

David Angulo, MD, chief medical officer for Scynexis, said in a statement the tablets brings new benefits.

Dr. Angulo said the drug “has a differentiated fungicidal mechanism of action that kills a broad range of Candida species, including azole-resistant strains. We are working on completing our CANDLE study investigating ibrexafungerp for the prevention of recurrent VVC and expect we will be submitting a supplemental NDA [new drug application] in the first half of 2022.”

Scynexis said it partnered with Amplity Health, a Pennsylvania-based pharmaceutical company, to support U.S. marketing of the drug. The commercial launch will follow the approval.

Ibrexafungerp was granted approval through both the FDA’s Qualified Infectious Disease Product and Fast Track designations. It is expected to be marketed exclusively in the United States for 10 years.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Addressing an uncharted front in the war on COVID-19: Vaccination during pregnancy

In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration’s Emergency Use Authorization of the first COVID-19 vaccine presented us with a new tactic in the war against SARS-COV-2—and a new dilemma for obstetricians. What we had learned about COVID-19 infection in pregnancy by that point was alarming. While the vast majority (>90%) of pregnant women who contract COVID-19 recover without requiring hospitalization, pregnant women are at increased risk for severe illness and mechanical ventilation when compared with their nonpregnant counterparts.1 Vertical transmission to the fetus is a rare event, but the increased risk of preterm birth, miscarriage, and preeclampsia makes the fetus a second victim in many cases.2 Moreover, much is still unknown about the long-term impact of severe illness on maternal and fetal health.

Gaining vaccine approval