User login

Jury still out on cardiovascular safety of testosterone

Despite a new meta-analysis claiming to show that testosterone replacement therapy for men with hypogonadism does not increase the risk of cardiovascular outcomes such as myocardial infarction or stroke, experts say the jury is still out.

A more definitive answer for cardiovascular safety of testosterone therapy will come from the TRAVERSE dedicated cardiovascular outcome trial, sponsored by AbbVie, which will have up to 5 years of follow-up, with results expected later this year.

The current meta-analysis by Jemma Hudson of Aberdeen (Scotland) University and colleagues was published online in The Lancet Healthy Longevity. The work will also be presented June 13 at ENDO 2022, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, by senior author Channa Y. Jayasena, MD, PhD.

In 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration mandated a label on testosterone products warning of possible increased cardiovascular risks and to reserve the therapy for symptomatic hypogonadism only. In contrast, the European Medicines Agency concluded that when hypogonadism is properly diagnosed and managed, there is currently no clear, consistent evidence that testosterone therapy causes increased cardiovascular risk.

To address this uncertainty, Dr. Hudson and colleagues formed a global collaborative to obtain individual patient data on cardiovascular outcomes from randomized controlled trials of testosterone therapy for men with hypogonadism.

They pooled data from 35 trials published from 1992 to Aug. 27, 2018, including 17 trials (3,431 patients) for which the researchers obtained patient-level data. The individual trials were 3-12 months long, except for one 3-year trial.

During a mean follow-up of 9.5 months, there was no significant increase in cardiovascular outcomes in men randomized to testosterone therapy versus placebo (odds ratio, 1.07; P = .62), nor were there any significantly increased risks of death, stroke, or different types of cardiovascular outcome, although those numbers were small.

This is “the most comprehensive study to date investigating the safety of testosterone treatment of hypogonadism,” according to the researchers. “The current results provide some reassurance about the short-term to medium-term safety of testosterone to treat male hypogonadism,” they conclude.

However, they also acknowledge that “long-term data are needed to fully evaluate the safety of testosterone.”

Erin D. Michos, MD, coauthor of an accompanying editorial, told this news organization, “This study doesn’t say to me that low testosterone necessarily needs to be treated. It’s still not indicated in people just for a low number [for blood testosterone] with less-severe symptoms. It really comes down to each individual person, how symptomatic they are, and their cardiovascular risk.”

‘Trial is not definitive’

Dr. Michos is not the only person to be skeptical. Together with Steven Nissen, MD, an investigator for the TRAVERSE trial, she agrees that this new evidence is not yet decisive, largely because the individual trials in the meta-analysis were short and not designed as cardiovascular outcome trials.

Dr. Nissen, a cardiologist at Cleveland Clinic, added that the individual trials were heterogeneous, with “very few real cardiovascular events,” so the meta-analysis “is not definitive,” he said in an interview.

While this meta-analysis “that pooled together a lot of smaller studies is reassuring that there’s no signal of harm, it’s really inconclusive because the follow-up was really short – a mean of only 9.5 months – and you really need a larger study with longer follow up to be more conclusive,” Dr. Michos noted.

“We should have more data soon” from TRAVERSE, said Dr. Michos, from the division of cardiology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who is not involved with that study.

Meanwhile, “I don’t think [this analysis] changes the current recommendations,” she said.

“We should continue to use caution as indicated by the FDA label and only use testosterone therapy selectively in people who have true symptoms of hypogonadism,” and be cautious about using it particularly in men at higher cardiovascular risk because of family history or known personal heart disease.

On the other hand, the meta-analysis did not show harm, she noted, “so we don’t necessarily need to pull patients off therapy if they are already taking it. But I wouldn’t right now just start new patients on it unless they had a strong indication.”

“Certainly, great caution is advised regarding the use of testosterone replacement therapy in people with established atherosclerosis due to the findings of plaque progression in the testosterone trials and the excess cardiovascular events observed in the TOM trial, write Dr. Michos and fellow editorialist Matthew J. Budoff, MD, of University of California, Los Angeles, in their editorial.

Earlier data inconclusive

Testosterone concentrations progressively decline in men with advancing age, at about 2% per year, Dr. Michos and Dr. Budoff write. In addition, men with obesity or with diabetes have low levels of testosterone, Dr. Michos noted.

Low testosterone blood levels have been associated with insulin resistance, inflammation, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis. Testosterone replacement therapy has been used to increase libido, improve erectile dysfunction, and boost energy levels, mood, and muscle strength.

But it is well known that testosterone increases hematocrit, which has the potential to increase the risk of venous thromboembolism.

Two large observational studies have reported increased risks of myocardial infarction, stroke, and death in men taking testosterone, compared with nonusers, but the study designs have been widely criticized, Dr. Hudson and coauthors say in their article.

A placebo-controlled trial was stopped early by its data- and safety-monitoring board following increased cardiovascular events in men aged 65 and older who received 6 months of testosterone. Other controlled trials have not observed these effects, but none was sufficiently powered.

Meta-analysis results

Dr. Hudson and colleagues performed a meta-analysis of 35 trials in 5,601 men aged 18 years and older with low baseline testosterone (≤ 350 nmol/dL) who had been randomized to testosterone replacement therapy or placebo for at least 3 months, for which there were data on mortality, stroke, and cardiovascular outcomes.

The men were a mean age of 65, had a mean body mass index of 30 kg/m2, and most (88%) were White. A quarter had angina, 8% had a previous myocardial infarction, and 27% had diabetes.

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes were not primary outcomes.

During a mean follow-up of 9.5 months, in the 13 trials that provided this information, the rate of cardiovascular events was similar in the men who received testosterone (120/1,601, 7.5%) compared with those who received placebo (110/1,519, 7.2%).

In the 14 trials that provided this information, fewer deaths were reported during testosterone treatment (6/1,621, 0.4%) than during placebo treatment (12/1,537, 0.8%), but these numbers were too small to establish whether testosterone reduced mortality risk.

The most common cardiovascular events were arrhythmia, followed by coronary heart disease, heart failure, and myocardial infarction.

Patient age, baseline testosterone, smoking status, or diabetes status were not associated with cardiovascular risk.

The only detected adverse effects were edema and a modest lowering of HDL cholesterol.

“Men who develop sexual dysfunction, unexplained anemia, or osteoporosis should be tested for low testosterone,” senior author of the meta-analysis Dr. Jayasena said in an email to this news organization.

However, Dr. Jayasena added, “Mass screening for testosterone has no benefit in asymptomatic men.”

“Older men may still benefit from testosterone, but only if they have the clinical features [of hypogonadism] and low testosterone levels,” he concluded.

The current study is supported by the Health Technology Assessment program of the National Institute for Health Research. The TRAVERSE trial is sponsored by AbbVie. Dr. Jayasena has reported receiving research grants from LogixX Pharma. Dr. Hudson has reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are listed in the article. Dr. Michos has reported receiving support from the Amato Fund in Women’s Cardiovascular Health at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and serving on medical advisory boards for Novartis, Esperion, Amarin, and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. Dr. Budoff has reported receiving grant support from General Electric.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite a new meta-analysis claiming to show that testosterone replacement therapy for men with hypogonadism does not increase the risk of cardiovascular outcomes such as myocardial infarction or stroke, experts say the jury is still out.

A more definitive answer for cardiovascular safety of testosterone therapy will come from the TRAVERSE dedicated cardiovascular outcome trial, sponsored by AbbVie, which will have up to 5 years of follow-up, with results expected later this year.

The current meta-analysis by Jemma Hudson of Aberdeen (Scotland) University and colleagues was published online in The Lancet Healthy Longevity. The work will also be presented June 13 at ENDO 2022, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, by senior author Channa Y. Jayasena, MD, PhD.

In 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration mandated a label on testosterone products warning of possible increased cardiovascular risks and to reserve the therapy for symptomatic hypogonadism only. In contrast, the European Medicines Agency concluded that when hypogonadism is properly diagnosed and managed, there is currently no clear, consistent evidence that testosterone therapy causes increased cardiovascular risk.

To address this uncertainty, Dr. Hudson and colleagues formed a global collaborative to obtain individual patient data on cardiovascular outcomes from randomized controlled trials of testosterone therapy for men with hypogonadism.

They pooled data from 35 trials published from 1992 to Aug. 27, 2018, including 17 trials (3,431 patients) for which the researchers obtained patient-level data. The individual trials were 3-12 months long, except for one 3-year trial.

During a mean follow-up of 9.5 months, there was no significant increase in cardiovascular outcomes in men randomized to testosterone therapy versus placebo (odds ratio, 1.07; P = .62), nor were there any significantly increased risks of death, stroke, or different types of cardiovascular outcome, although those numbers were small.

This is “the most comprehensive study to date investigating the safety of testosterone treatment of hypogonadism,” according to the researchers. “The current results provide some reassurance about the short-term to medium-term safety of testosterone to treat male hypogonadism,” they conclude.

However, they also acknowledge that “long-term data are needed to fully evaluate the safety of testosterone.”

Erin D. Michos, MD, coauthor of an accompanying editorial, told this news organization, “This study doesn’t say to me that low testosterone necessarily needs to be treated. It’s still not indicated in people just for a low number [for blood testosterone] with less-severe symptoms. It really comes down to each individual person, how symptomatic they are, and their cardiovascular risk.”

‘Trial is not definitive’

Dr. Michos is not the only person to be skeptical. Together with Steven Nissen, MD, an investigator for the TRAVERSE trial, she agrees that this new evidence is not yet decisive, largely because the individual trials in the meta-analysis were short and not designed as cardiovascular outcome trials.

Dr. Nissen, a cardiologist at Cleveland Clinic, added that the individual trials were heterogeneous, with “very few real cardiovascular events,” so the meta-analysis “is not definitive,” he said in an interview.

While this meta-analysis “that pooled together a lot of smaller studies is reassuring that there’s no signal of harm, it’s really inconclusive because the follow-up was really short – a mean of only 9.5 months – and you really need a larger study with longer follow up to be more conclusive,” Dr. Michos noted.

“We should have more data soon” from TRAVERSE, said Dr. Michos, from the division of cardiology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who is not involved with that study.

Meanwhile, “I don’t think [this analysis] changes the current recommendations,” she said.

“We should continue to use caution as indicated by the FDA label and only use testosterone therapy selectively in people who have true symptoms of hypogonadism,” and be cautious about using it particularly in men at higher cardiovascular risk because of family history or known personal heart disease.

On the other hand, the meta-analysis did not show harm, she noted, “so we don’t necessarily need to pull patients off therapy if they are already taking it. But I wouldn’t right now just start new patients on it unless they had a strong indication.”

“Certainly, great caution is advised regarding the use of testosterone replacement therapy in people with established atherosclerosis due to the findings of plaque progression in the testosterone trials and the excess cardiovascular events observed in the TOM trial, write Dr. Michos and fellow editorialist Matthew J. Budoff, MD, of University of California, Los Angeles, in their editorial.

Earlier data inconclusive

Testosterone concentrations progressively decline in men with advancing age, at about 2% per year, Dr. Michos and Dr. Budoff write. In addition, men with obesity or with diabetes have low levels of testosterone, Dr. Michos noted.

Low testosterone blood levels have been associated with insulin resistance, inflammation, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis. Testosterone replacement therapy has been used to increase libido, improve erectile dysfunction, and boost energy levels, mood, and muscle strength.

But it is well known that testosterone increases hematocrit, which has the potential to increase the risk of venous thromboembolism.

Two large observational studies have reported increased risks of myocardial infarction, stroke, and death in men taking testosterone, compared with nonusers, but the study designs have been widely criticized, Dr. Hudson and coauthors say in their article.

A placebo-controlled trial was stopped early by its data- and safety-monitoring board following increased cardiovascular events in men aged 65 and older who received 6 months of testosterone. Other controlled trials have not observed these effects, but none was sufficiently powered.

Meta-analysis results

Dr. Hudson and colleagues performed a meta-analysis of 35 trials in 5,601 men aged 18 years and older with low baseline testosterone (≤ 350 nmol/dL) who had been randomized to testosterone replacement therapy or placebo for at least 3 months, for which there were data on mortality, stroke, and cardiovascular outcomes.

The men were a mean age of 65, had a mean body mass index of 30 kg/m2, and most (88%) were White. A quarter had angina, 8% had a previous myocardial infarction, and 27% had diabetes.

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes were not primary outcomes.

During a mean follow-up of 9.5 months, in the 13 trials that provided this information, the rate of cardiovascular events was similar in the men who received testosterone (120/1,601, 7.5%) compared with those who received placebo (110/1,519, 7.2%).

In the 14 trials that provided this information, fewer deaths were reported during testosterone treatment (6/1,621, 0.4%) than during placebo treatment (12/1,537, 0.8%), but these numbers were too small to establish whether testosterone reduced mortality risk.

The most common cardiovascular events were arrhythmia, followed by coronary heart disease, heart failure, and myocardial infarction.

Patient age, baseline testosterone, smoking status, or diabetes status were not associated with cardiovascular risk.

The only detected adverse effects were edema and a modest lowering of HDL cholesterol.

“Men who develop sexual dysfunction, unexplained anemia, or osteoporosis should be tested for low testosterone,” senior author of the meta-analysis Dr. Jayasena said in an email to this news organization.

However, Dr. Jayasena added, “Mass screening for testosterone has no benefit in asymptomatic men.”

“Older men may still benefit from testosterone, but only if they have the clinical features [of hypogonadism] and low testosterone levels,” he concluded.

The current study is supported by the Health Technology Assessment program of the National Institute for Health Research. The TRAVERSE trial is sponsored by AbbVie. Dr. Jayasena has reported receiving research grants from LogixX Pharma. Dr. Hudson has reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are listed in the article. Dr. Michos has reported receiving support from the Amato Fund in Women’s Cardiovascular Health at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and serving on medical advisory boards for Novartis, Esperion, Amarin, and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. Dr. Budoff has reported receiving grant support from General Electric.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite a new meta-analysis claiming to show that testosterone replacement therapy for men with hypogonadism does not increase the risk of cardiovascular outcomes such as myocardial infarction or stroke, experts say the jury is still out.

A more definitive answer for cardiovascular safety of testosterone therapy will come from the TRAVERSE dedicated cardiovascular outcome trial, sponsored by AbbVie, which will have up to 5 years of follow-up, with results expected later this year.

The current meta-analysis by Jemma Hudson of Aberdeen (Scotland) University and colleagues was published online in The Lancet Healthy Longevity. The work will also be presented June 13 at ENDO 2022, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, by senior author Channa Y. Jayasena, MD, PhD.

In 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration mandated a label on testosterone products warning of possible increased cardiovascular risks and to reserve the therapy for symptomatic hypogonadism only. In contrast, the European Medicines Agency concluded that when hypogonadism is properly diagnosed and managed, there is currently no clear, consistent evidence that testosterone therapy causes increased cardiovascular risk.

To address this uncertainty, Dr. Hudson and colleagues formed a global collaborative to obtain individual patient data on cardiovascular outcomes from randomized controlled trials of testosterone therapy for men with hypogonadism.

They pooled data from 35 trials published from 1992 to Aug. 27, 2018, including 17 trials (3,431 patients) for which the researchers obtained patient-level data. The individual trials were 3-12 months long, except for one 3-year trial.

During a mean follow-up of 9.5 months, there was no significant increase in cardiovascular outcomes in men randomized to testosterone therapy versus placebo (odds ratio, 1.07; P = .62), nor were there any significantly increased risks of death, stroke, or different types of cardiovascular outcome, although those numbers were small.

This is “the most comprehensive study to date investigating the safety of testosterone treatment of hypogonadism,” according to the researchers. “The current results provide some reassurance about the short-term to medium-term safety of testosterone to treat male hypogonadism,” they conclude.

However, they also acknowledge that “long-term data are needed to fully evaluate the safety of testosterone.”

Erin D. Michos, MD, coauthor of an accompanying editorial, told this news organization, “This study doesn’t say to me that low testosterone necessarily needs to be treated. It’s still not indicated in people just for a low number [for blood testosterone] with less-severe symptoms. It really comes down to each individual person, how symptomatic they are, and their cardiovascular risk.”

‘Trial is not definitive’

Dr. Michos is not the only person to be skeptical. Together with Steven Nissen, MD, an investigator for the TRAVERSE trial, she agrees that this new evidence is not yet decisive, largely because the individual trials in the meta-analysis were short and not designed as cardiovascular outcome trials.

Dr. Nissen, a cardiologist at Cleveland Clinic, added that the individual trials were heterogeneous, with “very few real cardiovascular events,” so the meta-analysis “is not definitive,” he said in an interview.

While this meta-analysis “that pooled together a lot of smaller studies is reassuring that there’s no signal of harm, it’s really inconclusive because the follow-up was really short – a mean of only 9.5 months – and you really need a larger study with longer follow up to be more conclusive,” Dr. Michos noted.

“We should have more data soon” from TRAVERSE, said Dr. Michos, from the division of cardiology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who is not involved with that study.

Meanwhile, “I don’t think [this analysis] changes the current recommendations,” she said.

“We should continue to use caution as indicated by the FDA label and only use testosterone therapy selectively in people who have true symptoms of hypogonadism,” and be cautious about using it particularly in men at higher cardiovascular risk because of family history or known personal heart disease.

On the other hand, the meta-analysis did not show harm, she noted, “so we don’t necessarily need to pull patients off therapy if they are already taking it. But I wouldn’t right now just start new patients on it unless they had a strong indication.”

“Certainly, great caution is advised regarding the use of testosterone replacement therapy in people with established atherosclerosis due to the findings of plaque progression in the testosterone trials and the excess cardiovascular events observed in the TOM trial, write Dr. Michos and fellow editorialist Matthew J. Budoff, MD, of University of California, Los Angeles, in their editorial.

Earlier data inconclusive

Testosterone concentrations progressively decline in men with advancing age, at about 2% per year, Dr. Michos and Dr. Budoff write. In addition, men with obesity or with diabetes have low levels of testosterone, Dr. Michos noted.

Low testosterone blood levels have been associated with insulin resistance, inflammation, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis. Testosterone replacement therapy has been used to increase libido, improve erectile dysfunction, and boost energy levels, mood, and muscle strength.

But it is well known that testosterone increases hematocrit, which has the potential to increase the risk of venous thromboembolism.

Two large observational studies have reported increased risks of myocardial infarction, stroke, and death in men taking testosterone, compared with nonusers, but the study designs have been widely criticized, Dr. Hudson and coauthors say in their article.

A placebo-controlled trial was stopped early by its data- and safety-monitoring board following increased cardiovascular events in men aged 65 and older who received 6 months of testosterone. Other controlled trials have not observed these effects, but none was sufficiently powered.

Meta-analysis results

Dr. Hudson and colleagues performed a meta-analysis of 35 trials in 5,601 men aged 18 years and older with low baseline testosterone (≤ 350 nmol/dL) who had been randomized to testosterone replacement therapy or placebo for at least 3 months, for which there were data on mortality, stroke, and cardiovascular outcomes.

The men were a mean age of 65, had a mean body mass index of 30 kg/m2, and most (88%) were White. A quarter had angina, 8% had a previous myocardial infarction, and 27% had diabetes.

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes were not primary outcomes.

During a mean follow-up of 9.5 months, in the 13 trials that provided this information, the rate of cardiovascular events was similar in the men who received testosterone (120/1,601, 7.5%) compared with those who received placebo (110/1,519, 7.2%).

In the 14 trials that provided this information, fewer deaths were reported during testosterone treatment (6/1,621, 0.4%) than during placebo treatment (12/1,537, 0.8%), but these numbers were too small to establish whether testosterone reduced mortality risk.

The most common cardiovascular events were arrhythmia, followed by coronary heart disease, heart failure, and myocardial infarction.

Patient age, baseline testosterone, smoking status, or diabetes status were not associated with cardiovascular risk.

The only detected adverse effects were edema and a modest lowering of HDL cholesterol.

“Men who develop sexual dysfunction, unexplained anemia, or osteoporosis should be tested for low testosterone,” senior author of the meta-analysis Dr. Jayasena said in an email to this news organization.

However, Dr. Jayasena added, “Mass screening for testosterone has no benefit in asymptomatic men.”

“Older men may still benefit from testosterone, but only if they have the clinical features [of hypogonadism] and low testosterone levels,” he concluded.

The current study is supported by the Health Technology Assessment program of the National Institute for Health Research. The TRAVERSE trial is sponsored by AbbVie. Dr. Jayasena has reported receiving research grants from LogixX Pharma. Dr. Hudson has reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are listed in the article. Dr. Michos has reported receiving support from the Amato Fund in Women’s Cardiovascular Health at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and serving on medical advisory boards for Novartis, Esperion, Amarin, and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. Dr. Budoff has reported receiving grant support from General Electric.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET HEALTHY LONGEVITY

PCOS comes with high morbidity, medication use into late 40s

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) have an increased risk for several diseases and symptoms, many independent of body mass index (BMI), new research indicates.

Some diseases are linked for the first time to PCOS in this study, the authors wrote.

Researchers, led by Linda Kujanpää, MD, of the research unit for pediatrics, dermatology, clinical genetics, obstetrics, and gynecology at University of Oulu (Finland), found the morbidity risk is evident through the late reproductive years.

The paper was published online in Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.

This population-based follow-up study investigated comorbidities and medication and health care services use among women with PCOS in Finland at age 46 years via answers to a questionnaire.

The whole PCOS population (n = 280) consisted of women who reported both hirsutism and oligo/amenorrhea at age 31 (4.1%) and/or polycystic ovary morphology/PCOS at age 46 (3.1%), of which 246 replied to the 46-year questionnaire. They were compared with a control group of 1,573 women without PCOS.

Overall morbidity risk was 35% higher than for women without PCOS (risk ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.57). Medication use was 27% higher (RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.08-1.50), and the risk remained after adjusting for BMI.

Diagnoses with increased prevalence in women with PCOS were osteoarthritis, migraine, hypertension, tendinitis, and endometriosis. PCOS was also associated with autoimmune diseases and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections.

“BMI seems not to be solely responsible for the increased morbidity,” the researchers found. The average morbidity score of women with PCOS with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher was similar to that of women with PCOS and lower BMI.

Mindy Christianson, MD, medical director at Johns Hopkins Fertility Center and associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore, said in an interview that the links to diseases independent of BMI are interesting because there’s so much focus on counseling women with PCOS to lose weight.

While that message is still important, it’s important to realize that some related diseases and conditions – such as autoimmune diseases and migraine – are not driven by BMI.

“It really drives home the point that polycystic ovary syndrome is really a chronic medical condition and puts patients at risk for a number of health conditions,” she said. “Having a good primary care physician is important to help them with their overall health.”

Women with PCOS said their health was poor or very poor almost three times more often than did women in the control group.

Surprisingly few studies have looked at overall comorbidity in women with PCOS, the authors wrote.

“This should be of high priority given the high cost to society resulting from PCOS-related morbidity,” they added. As an example, they pointed out that PCOS-related type 2 diabetes alone costs an estimated $1.77 billion in the United States and £237 million ($310 million) each year in the United Kingdom.

Additionally, the focus in previous research has typically been on women in their early or mid-reproductive years, and morbidity burden data in late reproductive years are scarce.

The study population was pulled from the longitudinal Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 and included all pregnancies with estimated date of delivery during 1966 in two provinces of Finland (5,889 women).

Dr. Christianson said she hopes this study will spur more research on PCOS, which has been severely underfunded, especially in the United States.

Part of the reason for that is there is a limited number of subspecialists in the country who work with patients with PCOS and do research in the area. PCOS often gets lost in the research priorities of infertility, diabetes, and thyroid disease.

The message in this study that PCOS is not just a fertility issue or an obesity issue but an overall health issue with a substantial cost to the health system may help raise awareness, Dr. Christianson said.

This study was supported by grants from The Finnish Medical Foundation, The Academy of Finland, The Sigrid Juselius Foundation, The Finnish Cultural Foundation, The Jalmari and Rauha Ahokas Foundation, The Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, Genesis Research Trust, The Medical Research Council, University of Oulu, Oulu University Hospital, Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Regional Institute of Occupational Health, and the European Regional Development Fund. The Study authors and Dr. Christianson reported no relevant financial relationships.

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) have an increased risk for several diseases and symptoms, many independent of body mass index (BMI), new research indicates.

Some diseases are linked for the first time to PCOS in this study, the authors wrote.

Researchers, led by Linda Kujanpää, MD, of the research unit for pediatrics, dermatology, clinical genetics, obstetrics, and gynecology at University of Oulu (Finland), found the morbidity risk is evident through the late reproductive years.

The paper was published online in Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.

This population-based follow-up study investigated comorbidities and medication and health care services use among women with PCOS in Finland at age 46 years via answers to a questionnaire.

The whole PCOS population (n = 280) consisted of women who reported both hirsutism and oligo/amenorrhea at age 31 (4.1%) and/or polycystic ovary morphology/PCOS at age 46 (3.1%), of which 246 replied to the 46-year questionnaire. They were compared with a control group of 1,573 women without PCOS.

Overall morbidity risk was 35% higher than for women without PCOS (risk ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.57). Medication use was 27% higher (RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.08-1.50), and the risk remained after adjusting for BMI.

Diagnoses with increased prevalence in women with PCOS were osteoarthritis, migraine, hypertension, tendinitis, and endometriosis. PCOS was also associated with autoimmune diseases and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections.

“BMI seems not to be solely responsible for the increased morbidity,” the researchers found. The average morbidity score of women with PCOS with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher was similar to that of women with PCOS and lower BMI.

Mindy Christianson, MD, medical director at Johns Hopkins Fertility Center and associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore, said in an interview that the links to diseases independent of BMI are interesting because there’s so much focus on counseling women with PCOS to lose weight.

While that message is still important, it’s important to realize that some related diseases and conditions – such as autoimmune diseases and migraine – are not driven by BMI.

“It really drives home the point that polycystic ovary syndrome is really a chronic medical condition and puts patients at risk for a number of health conditions,” she said. “Having a good primary care physician is important to help them with their overall health.”

Women with PCOS said their health was poor or very poor almost three times more often than did women in the control group.

Surprisingly few studies have looked at overall comorbidity in women with PCOS, the authors wrote.

“This should be of high priority given the high cost to society resulting from PCOS-related morbidity,” they added. As an example, they pointed out that PCOS-related type 2 diabetes alone costs an estimated $1.77 billion in the United States and £237 million ($310 million) each year in the United Kingdom.

Additionally, the focus in previous research has typically been on women in their early or mid-reproductive years, and morbidity burden data in late reproductive years are scarce.

The study population was pulled from the longitudinal Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 and included all pregnancies with estimated date of delivery during 1966 in two provinces of Finland (5,889 women).

Dr. Christianson said she hopes this study will spur more research on PCOS, which has been severely underfunded, especially in the United States.

Part of the reason for that is there is a limited number of subspecialists in the country who work with patients with PCOS and do research in the area. PCOS often gets lost in the research priorities of infertility, diabetes, and thyroid disease.

The message in this study that PCOS is not just a fertility issue or an obesity issue but an overall health issue with a substantial cost to the health system may help raise awareness, Dr. Christianson said.

This study was supported by grants from The Finnish Medical Foundation, The Academy of Finland, The Sigrid Juselius Foundation, The Finnish Cultural Foundation, The Jalmari and Rauha Ahokas Foundation, The Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, Genesis Research Trust, The Medical Research Council, University of Oulu, Oulu University Hospital, Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Regional Institute of Occupational Health, and the European Regional Development Fund. The Study authors and Dr. Christianson reported no relevant financial relationships.

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) have an increased risk for several diseases and symptoms, many independent of body mass index (BMI), new research indicates.

Some diseases are linked for the first time to PCOS in this study, the authors wrote.

Researchers, led by Linda Kujanpää, MD, of the research unit for pediatrics, dermatology, clinical genetics, obstetrics, and gynecology at University of Oulu (Finland), found the morbidity risk is evident through the late reproductive years.

The paper was published online in Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.

This population-based follow-up study investigated comorbidities and medication and health care services use among women with PCOS in Finland at age 46 years via answers to a questionnaire.

The whole PCOS population (n = 280) consisted of women who reported both hirsutism and oligo/amenorrhea at age 31 (4.1%) and/or polycystic ovary morphology/PCOS at age 46 (3.1%), of which 246 replied to the 46-year questionnaire. They were compared with a control group of 1,573 women without PCOS.

Overall morbidity risk was 35% higher than for women without PCOS (risk ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.57). Medication use was 27% higher (RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.08-1.50), and the risk remained after adjusting for BMI.

Diagnoses with increased prevalence in women with PCOS were osteoarthritis, migraine, hypertension, tendinitis, and endometriosis. PCOS was also associated with autoimmune diseases and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections.

“BMI seems not to be solely responsible for the increased morbidity,” the researchers found. The average morbidity score of women with PCOS with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher was similar to that of women with PCOS and lower BMI.

Mindy Christianson, MD, medical director at Johns Hopkins Fertility Center and associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore, said in an interview that the links to diseases independent of BMI are interesting because there’s so much focus on counseling women with PCOS to lose weight.

While that message is still important, it’s important to realize that some related diseases and conditions – such as autoimmune diseases and migraine – are not driven by BMI.

“It really drives home the point that polycystic ovary syndrome is really a chronic medical condition and puts patients at risk for a number of health conditions,” she said. “Having a good primary care physician is important to help them with their overall health.”

Women with PCOS said their health was poor or very poor almost three times more often than did women in the control group.

Surprisingly few studies have looked at overall comorbidity in women with PCOS, the authors wrote.

“This should be of high priority given the high cost to society resulting from PCOS-related morbidity,” they added. As an example, they pointed out that PCOS-related type 2 diabetes alone costs an estimated $1.77 billion in the United States and £237 million ($310 million) each year in the United Kingdom.

Additionally, the focus in previous research has typically been on women in their early or mid-reproductive years, and morbidity burden data in late reproductive years are scarce.

The study population was pulled from the longitudinal Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 and included all pregnancies with estimated date of delivery during 1966 in two provinces of Finland (5,889 women).

Dr. Christianson said she hopes this study will spur more research on PCOS, which has been severely underfunded, especially in the United States.

Part of the reason for that is there is a limited number of subspecialists in the country who work with patients with PCOS and do research in the area. PCOS often gets lost in the research priorities of infertility, diabetes, and thyroid disease.

The message in this study that PCOS is not just a fertility issue or an obesity issue but an overall health issue with a substantial cost to the health system may help raise awareness, Dr. Christianson said.

This study was supported by grants from The Finnish Medical Foundation, The Academy of Finland, The Sigrid Juselius Foundation, The Finnish Cultural Foundation, The Jalmari and Rauha Ahokas Foundation, The Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, Genesis Research Trust, The Medical Research Council, University of Oulu, Oulu University Hospital, Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Regional Institute of Occupational Health, and the European Regional Development Fund. The Study authors and Dr. Christianson reported no relevant financial relationships.

FROM ACTA OBSTETRICIA ET GYNECOLOGICA SCANDINAVICA

Antipsychotic tied to dose-related weight gain, higher cholesterol

new research suggests.

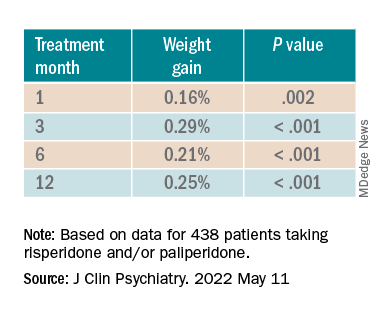

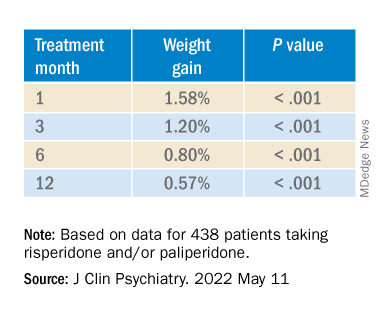

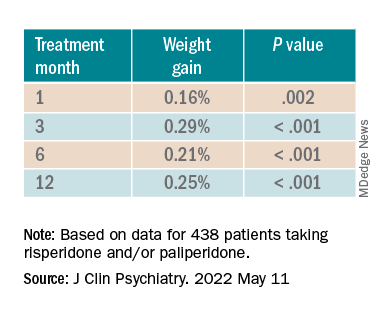

Investigators analyzed 1-year data for more than 400 patients who were taking risperidone and/or its metabolite paliperidone (Invega). Results showed increments of 1 mg of risperidone-equivalent doses were associated with an increase of 0.25% of weight within a year of follow-up.

“Although our findings report a positive and statistically significant dose-dependence of weight gain and cholesterol, both total and LDL [cholesterol], the size of the predicted changes of metabolic effects is clinically nonrelevant,” lead author Marianna Piras, PharmD, Centre for Psychiatric Neuroscience, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, said in an interview.

“Therefore, dose lowering would not have a beneficial effect on attenuating weight gain or cholesterol increases and could lead to psychiatric decompensation,” said Ms. Piras, who is also a PhD candidate in the unit of pharmacogenetics and clinical psychopharmacology at the University of Lausanne.

However, she added that because dose increments could increase risk for significant weight gain in the first month of treatment – the dose can be increased typically in a range of 1-10 grams – and strong dose increments could contribute to metabolic worsening over time, “risperidone minimum effective doses should be preferred.”

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Serious public health issue’

Compared with the general population, patients with mental illness present with a greater prevalence of metabolic disorders. In addition, several psychotropic medications, including antipsychotics, can induce metabolic alterations such as weight gain, the investigators noted.

Antipsychotic-induced metabolic adverse effects “constitute a serious public health issue” because they are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases such as obesity and/or dyslipidemia, “which have been associated with a 10-year reduced life expectancy in the psychiatric population,” Ms. Piras said.

“The dose-dependence of metabolic adverse effects is a debated subject that needs to be assessed for each psychotropic drug known to induce weight gain,” she added.

Several previous studies have examined whether there is a dose-related effect of antipsychotics on metabolic parameters, “with some results suggesting that [weight gain] seems to develop even when low off-label doses are prescribed,” Ms. Piras noted.

She and her colleagues had already studied dose-related metabolic effects of quetiapine (Seroquel) and olanzapine (Zyprexa).

Risperidone is an antipsychotic with a “medium to high metabolic risk profile,” the researchers note, and few studies have examined the impact of risperidone on metabolic parameters other than weight gain.

For the current analysis, they analyzed data from a longitudinal study that included 438 patients (mean age, 40.7 years; 50.7% men) who started treatment with risperidone and/or paliperidone between 2007 and 2018.

The participants had diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, “other,” or “unknown.”

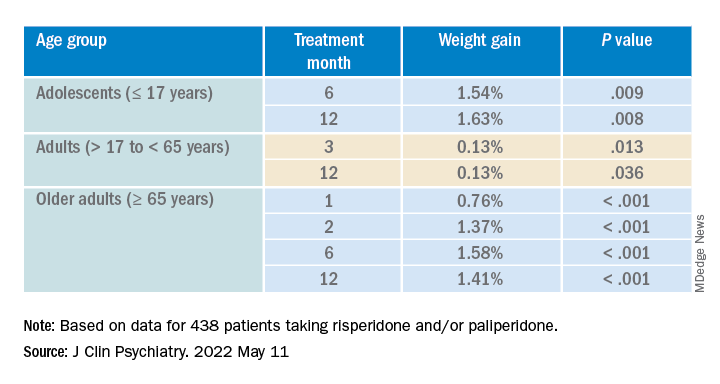

Clinical follow-up periods were up to a year, but were no shorter than 3 weeks. The investigators also assessed the data at different time intervals at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months “to appreciate the evolution of the metabolic parameters.”

In addition, they collected demographic and clinical information, such as comorbidities, and measured patients’ weight, height, waist circumference, blood pressure, plasma glucose, and lipids at baseline and at 1, 3, and 12 months and then annually. Weight, waist circumference, and BP were also assessed at 2 and 6 months.

Doses of paliperidone were converted into risperidone-equivalent doses.

Significant weight gain over time

The mean duration of follow-up for the participants, of whom 374 were being treated with risperidone and 64 with paliperidone, was 153 days. Close to half (48.2%) were taking other psychotropic medications known to be associated with some degree of metabolic risk.

Patients were divided into two cohorts based on their daily dose intake (DDI): less than 3 mg/day (n = 201) and at least 3 mg/day (n = 237).

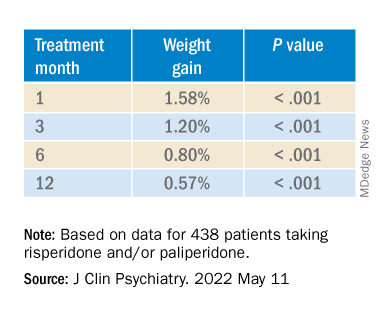

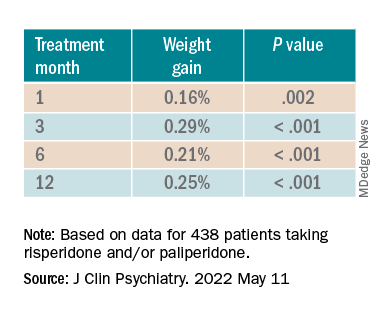

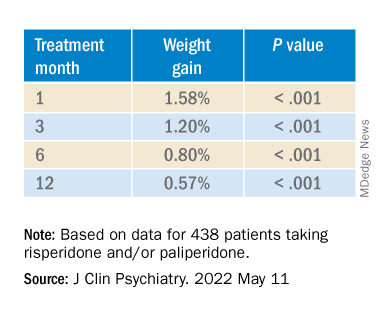

In the overall cohort, a “significant effect of time on weight change was found for each time point,” the investigators reported.

When the researchers looked at the changes according to DDI, they found that each 1-mg dose increase was associated with incremental weight gain at each time point.

Patients who had 5% or greater weight gain in the first month continued to gain weight more than patients who did not reach that threshold, leading the researchers to call that early threshold a “strong predictor of important weight gain in the long term.” There was a weight gain of 6.68% at 3 months, of 7.36% at 6 months, and of 7.7% at 12 months.

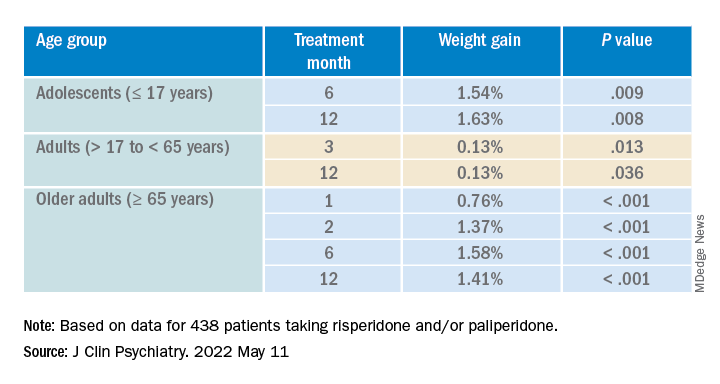

After the patients were stratified by age, there were differences in the effect of DDI on various age groups at different time points.

Dose was shown to have a significant effect on weight gain for women at all four time points (P ≥ .001), but for men only at 3 months (P = .003).

For each additional 1-mg dose, there was a 0.05 mmol/L (1.93 mg/dL) increase in total cholesterol (P = .018) after 1 year and a 0.04 mmol/L (1.54 mg/dL) increase in LDL cholesterol (P = .011).

There were no significant effects of time or DDI on triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, glucose levels, and systolic BP, and there was a negative effect of DDI on diastolic BP (P = .001).

The findings “provide evidence for a small dose effect of risperidone” on weight gain and total and LDL cholesterol levels, the investigators note.

Ms. Piras added that because each antipsychotic differs in its metabolic risk profile, “further analyses on other antipsychotics are ongoing in our laboratory, so far confirming our findings.”

Small increases, big changes

Commenting on the study, Erika Nurmi, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience, University of California, Los Angeles, said the study is “unique in the field.”

It “leverages real-world data from a large patient registry to ask a long-unanswered question: Are weight and metabolic adverse effects proportional to dose? Big data approaches like these are very powerful, given the large number of participants that can be included,” said Dr. Nurmi, who was not involved with the research.

However, she cautioned, the “biggest drawback [is that] these data are by nature much more complex and prone to confounding effects.”

In this case, a “critical confounder” for the study was that the majority of individuals taking higher risperidone doses were also taking other drugs known to cause weight gain, whereas the majority of those on lower risperidone doses were not. “This difference may explain the dose relationship observed,” she said.

Because real-world, big data are “valuable but also messy, conclusions drawn from them must be interpreted with caution,” Dr. Nurmi said.

She added that it is generally wise to use the lowest effective dose possible.

“Clinicians should appreciate that even small doses of antipsychotics can cause big changes in weight. Risks and benefits of medications must be carefully considered in clinical practice,” Dr. Nurmi said.

The research was funded in part by the Swiss National Research Foundation. Piras reports no relevant financial relationships. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Nurmi reported no relevant financial relationships, but she is an unpaid member of the Tourette Association of America’s medical advisory board and of the Myriad Genetics scientific advisory board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Investigators analyzed 1-year data for more than 400 patients who were taking risperidone and/or its metabolite paliperidone (Invega). Results showed increments of 1 mg of risperidone-equivalent doses were associated with an increase of 0.25% of weight within a year of follow-up.

“Although our findings report a positive and statistically significant dose-dependence of weight gain and cholesterol, both total and LDL [cholesterol], the size of the predicted changes of metabolic effects is clinically nonrelevant,” lead author Marianna Piras, PharmD, Centre for Psychiatric Neuroscience, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, said in an interview.

“Therefore, dose lowering would not have a beneficial effect on attenuating weight gain or cholesterol increases and could lead to psychiatric decompensation,” said Ms. Piras, who is also a PhD candidate in the unit of pharmacogenetics and clinical psychopharmacology at the University of Lausanne.

However, she added that because dose increments could increase risk for significant weight gain in the first month of treatment – the dose can be increased typically in a range of 1-10 grams – and strong dose increments could contribute to metabolic worsening over time, “risperidone minimum effective doses should be preferred.”

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Serious public health issue’

Compared with the general population, patients with mental illness present with a greater prevalence of metabolic disorders. In addition, several psychotropic medications, including antipsychotics, can induce metabolic alterations such as weight gain, the investigators noted.

Antipsychotic-induced metabolic adverse effects “constitute a serious public health issue” because they are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases such as obesity and/or dyslipidemia, “which have been associated with a 10-year reduced life expectancy in the psychiatric population,” Ms. Piras said.

“The dose-dependence of metabolic adverse effects is a debated subject that needs to be assessed for each psychotropic drug known to induce weight gain,” she added.

Several previous studies have examined whether there is a dose-related effect of antipsychotics on metabolic parameters, “with some results suggesting that [weight gain] seems to develop even when low off-label doses are prescribed,” Ms. Piras noted.

She and her colleagues had already studied dose-related metabolic effects of quetiapine (Seroquel) and olanzapine (Zyprexa).

Risperidone is an antipsychotic with a “medium to high metabolic risk profile,” the researchers note, and few studies have examined the impact of risperidone on metabolic parameters other than weight gain.

For the current analysis, they analyzed data from a longitudinal study that included 438 patients (mean age, 40.7 years; 50.7% men) who started treatment with risperidone and/or paliperidone between 2007 and 2018.

The participants had diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, “other,” or “unknown.”

Clinical follow-up periods were up to a year, but were no shorter than 3 weeks. The investigators also assessed the data at different time intervals at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months “to appreciate the evolution of the metabolic parameters.”

In addition, they collected demographic and clinical information, such as comorbidities, and measured patients’ weight, height, waist circumference, blood pressure, plasma glucose, and lipids at baseline and at 1, 3, and 12 months and then annually. Weight, waist circumference, and BP were also assessed at 2 and 6 months.

Doses of paliperidone were converted into risperidone-equivalent doses.

Significant weight gain over time

The mean duration of follow-up for the participants, of whom 374 were being treated with risperidone and 64 with paliperidone, was 153 days. Close to half (48.2%) were taking other psychotropic medications known to be associated with some degree of metabolic risk.

Patients were divided into two cohorts based on their daily dose intake (DDI): less than 3 mg/day (n = 201) and at least 3 mg/day (n = 237).

In the overall cohort, a “significant effect of time on weight change was found for each time point,” the investigators reported.

When the researchers looked at the changes according to DDI, they found that each 1-mg dose increase was associated with incremental weight gain at each time point.

Patients who had 5% or greater weight gain in the first month continued to gain weight more than patients who did not reach that threshold, leading the researchers to call that early threshold a “strong predictor of important weight gain in the long term.” There was a weight gain of 6.68% at 3 months, of 7.36% at 6 months, and of 7.7% at 12 months.

After the patients were stratified by age, there were differences in the effect of DDI on various age groups at different time points.

Dose was shown to have a significant effect on weight gain for women at all four time points (P ≥ .001), but for men only at 3 months (P = .003).

For each additional 1-mg dose, there was a 0.05 mmol/L (1.93 mg/dL) increase in total cholesterol (P = .018) after 1 year and a 0.04 mmol/L (1.54 mg/dL) increase in LDL cholesterol (P = .011).

There were no significant effects of time or DDI on triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, glucose levels, and systolic BP, and there was a negative effect of DDI on diastolic BP (P = .001).

The findings “provide evidence for a small dose effect of risperidone” on weight gain and total and LDL cholesterol levels, the investigators note.

Ms. Piras added that because each antipsychotic differs in its metabolic risk profile, “further analyses on other antipsychotics are ongoing in our laboratory, so far confirming our findings.”

Small increases, big changes

Commenting on the study, Erika Nurmi, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience, University of California, Los Angeles, said the study is “unique in the field.”

It “leverages real-world data from a large patient registry to ask a long-unanswered question: Are weight and metabolic adverse effects proportional to dose? Big data approaches like these are very powerful, given the large number of participants that can be included,” said Dr. Nurmi, who was not involved with the research.

However, she cautioned, the “biggest drawback [is that] these data are by nature much more complex and prone to confounding effects.”

In this case, a “critical confounder” for the study was that the majority of individuals taking higher risperidone doses were also taking other drugs known to cause weight gain, whereas the majority of those on lower risperidone doses were not. “This difference may explain the dose relationship observed,” she said.

Because real-world, big data are “valuable but also messy, conclusions drawn from them must be interpreted with caution,” Dr. Nurmi said.

She added that it is generally wise to use the lowest effective dose possible.

“Clinicians should appreciate that even small doses of antipsychotics can cause big changes in weight. Risks and benefits of medications must be carefully considered in clinical practice,” Dr. Nurmi said.

The research was funded in part by the Swiss National Research Foundation. Piras reports no relevant financial relationships. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Nurmi reported no relevant financial relationships, but she is an unpaid member of the Tourette Association of America’s medical advisory board and of the Myriad Genetics scientific advisory board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Investigators analyzed 1-year data for more than 400 patients who were taking risperidone and/or its metabolite paliperidone (Invega). Results showed increments of 1 mg of risperidone-equivalent doses were associated with an increase of 0.25% of weight within a year of follow-up.

“Although our findings report a positive and statistically significant dose-dependence of weight gain and cholesterol, both total and LDL [cholesterol], the size of the predicted changes of metabolic effects is clinically nonrelevant,” lead author Marianna Piras, PharmD, Centre for Psychiatric Neuroscience, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, said in an interview.

“Therefore, dose lowering would not have a beneficial effect on attenuating weight gain or cholesterol increases and could lead to psychiatric decompensation,” said Ms. Piras, who is also a PhD candidate in the unit of pharmacogenetics and clinical psychopharmacology at the University of Lausanne.

However, she added that because dose increments could increase risk for significant weight gain in the first month of treatment – the dose can be increased typically in a range of 1-10 grams – and strong dose increments could contribute to metabolic worsening over time, “risperidone minimum effective doses should be preferred.”

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Serious public health issue’

Compared with the general population, patients with mental illness present with a greater prevalence of metabolic disorders. In addition, several psychotropic medications, including antipsychotics, can induce metabolic alterations such as weight gain, the investigators noted.

Antipsychotic-induced metabolic adverse effects “constitute a serious public health issue” because they are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases such as obesity and/or dyslipidemia, “which have been associated with a 10-year reduced life expectancy in the psychiatric population,” Ms. Piras said.

“The dose-dependence of metabolic adverse effects is a debated subject that needs to be assessed for each psychotropic drug known to induce weight gain,” she added.

Several previous studies have examined whether there is a dose-related effect of antipsychotics on metabolic parameters, “with some results suggesting that [weight gain] seems to develop even when low off-label doses are prescribed,” Ms. Piras noted.

She and her colleagues had already studied dose-related metabolic effects of quetiapine (Seroquel) and olanzapine (Zyprexa).

Risperidone is an antipsychotic with a “medium to high metabolic risk profile,” the researchers note, and few studies have examined the impact of risperidone on metabolic parameters other than weight gain.

For the current analysis, they analyzed data from a longitudinal study that included 438 patients (mean age, 40.7 years; 50.7% men) who started treatment with risperidone and/or paliperidone between 2007 and 2018.

The participants had diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, “other,” or “unknown.”

Clinical follow-up periods were up to a year, but were no shorter than 3 weeks. The investigators also assessed the data at different time intervals at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months “to appreciate the evolution of the metabolic parameters.”

In addition, they collected demographic and clinical information, such as comorbidities, and measured patients’ weight, height, waist circumference, blood pressure, plasma glucose, and lipids at baseline and at 1, 3, and 12 months and then annually. Weight, waist circumference, and BP were also assessed at 2 and 6 months.

Doses of paliperidone were converted into risperidone-equivalent doses.

Significant weight gain over time

The mean duration of follow-up for the participants, of whom 374 were being treated with risperidone and 64 with paliperidone, was 153 days. Close to half (48.2%) were taking other psychotropic medications known to be associated with some degree of metabolic risk.

Patients were divided into two cohorts based on their daily dose intake (DDI): less than 3 mg/day (n = 201) and at least 3 mg/day (n = 237).

In the overall cohort, a “significant effect of time on weight change was found for each time point,” the investigators reported.

When the researchers looked at the changes according to DDI, they found that each 1-mg dose increase was associated with incremental weight gain at each time point.

Patients who had 5% or greater weight gain in the first month continued to gain weight more than patients who did not reach that threshold, leading the researchers to call that early threshold a “strong predictor of important weight gain in the long term.” There was a weight gain of 6.68% at 3 months, of 7.36% at 6 months, and of 7.7% at 12 months.

After the patients were stratified by age, there were differences in the effect of DDI on various age groups at different time points.

Dose was shown to have a significant effect on weight gain for women at all four time points (P ≥ .001), but for men only at 3 months (P = .003).

For each additional 1-mg dose, there was a 0.05 mmol/L (1.93 mg/dL) increase in total cholesterol (P = .018) after 1 year and a 0.04 mmol/L (1.54 mg/dL) increase in LDL cholesterol (P = .011).

There were no significant effects of time or DDI on triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, glucose levels, and systolic BP, and there was a negative effect of DDI on diastolic BP (P = .001).

The findings “provide evidence for a small dose effect of risperidone” on weight gain and total and LDL cholesterol levels, the investigators note.

Ms. Piras added that because each antipsychotic differs in its metabolic risk profile, “further analyses on other antipsychotics are ongoing in our laboratory, so far confirming our findings.”

Small increases, big changes

Commenting on the study, Erika Nurmi, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience, University of California, Los Angeles, said the study is “unique in the field.”

It “leverages real-world data from a large patient registry to ask a long-unanswered question: Are weight and metabolic adverse effects proportional to dose? Big data approaches like these are very powerful, given the large number of participants that can be included,” said Dr. Nurmi, who was not involved with the research.

However, she cautioned, the “biggest drawback [is that] these data are by nature much more complex and prone to confounding effects.”

In this case, a “critical confounder” for the study was that the majority of individuals taking higher risperidone doses were also taking other drugs known to cause weight gain, whereas the majority of those on lower risperidone doses were not. “This difference may explain the dose relationship observed,” she said.

Because real-world, big data are “valuable but also messy, conclusions drawn from them must be interpreted with caution,” Dr. Nurmi said.

She added that it is generally wise to use the lowest effective dose possible.

“Clinicians should appreciate that even small doses of antipsychotics can cause big changes in weight. Risks and benefits of medications must be carefully considered in clinical practice,” Dr. Nurmi said.

The research was funded in part by the Swiss National Research Foundation. Piras reports no relevant financial relationships. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Nurmi reported no relevant financial relationships, but she is an unpaid member of the Tourette Association of America’s medical advisory board and of the Myriad Genetics scientific advisory board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

Omega-3 supplement sweet spot found for BP reduction

A meta-analysis of 71 randomized controlled trials has found the sweet spot for omega-3 fatty acid intake for lowering blood pressure: between 2 and 3 g/day. The investigators also reported that people at higher risk for cardiovascular disease may benefit from higher daily intake of omega-3.

The study analyzed data from randomized controlled trials involving 4,973 individuals and published from 1987 to 2020. Most of the trials used a combined supplementation of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Outcomes analysis involved the impact of combined DHA-EPA at 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 grams daily on average changes in both systolic and diastolic BP and compared them with the placebo or control groups who had a combined intake of 0 g/day.

“We found a significant nonlinear dose-response relationship for both SBP and DBP models,” wrote senior author Xinzhi Li, MD, PhD, and colleagues. Dr. Li is program director of the school of pharmacy at Macau University of Science and Technology in Taipa, China.

Most of the trials included in the meta-analysis evaluated fish oil supplements, but a number also included EPA and DHA omega-3 fatty acids consumed in food.

When the investigators analyzed studies that used an average baseline SBP of greater than 130 mm Hg, they found that increasing omega-3 supplementation resulted in strong reductions in SBP and DBP, but not so with people with baseline SBP below 130 mm Hg.

Across the entire cohort, average SBP and DBP changes averaged –2.61 (95% confidence interval, –3.57 to –1.65) and –1.64 (95% CI, –2.29 to –0.99) mm Hg for people taking 2 g/d omega-3 supplements, and –2.61 (95% CI, –3.52 to –1.69) and –1.80 (95% CI, –2.38 to –1.23) for those on 3 g/d. The changes weren’t as robust in higher and lower intake groups overall.

However, the higher the BP, the more robust the reductions. For those with SBP greater than 130 mm Hg, 3 g/d resulted in an average change of –3.22 mm Hg (95% CI, –5.21 to –1.23). In the greater than 80 mm Hg DBP group, 3 g/d of omega-3 resulted in an average –3.81 mm Hg reduction (95% CI, –4.48 to –1.87). In patients with BP greater than 140/90 and hypertension, the reductions were even more pronounced. And in patients with BP greater than 130/80, omega-3 intake of 4-5 g/d had a greater impact than 2-3 g/d, although that benefit didn’t carry over in the greater than 140/90 group.

High cholesterol was also a factor in determining the benefits of omega-3 supplementation on BP, as Dr. Li and colleagues wrote that they found “an approximately linear relationship” between hyperlipidemia and SBP, “suggesting that increasing supplementation was associated with greater reductions in SBP.” Likewise, the study found stronger effects on BP in studies with an average patient age greater than 45 years.

In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration issued an update that consuming combined EPA and DHA may lower BP in the general population and reduce the risk of hypertension, but that “the evidence is inconsistent and inconclusive.”

“However, while our study may add a layer of credible evidence, it does not meet the threshold to make an authorized health claim for omega-3 fatty acids in compliance with FDA regulations,” Dr. Li said.

The study addresses shortcomings of previous studies of omega-3 and BP and by identifying the optimal dose, Marc George, MRCP, PhD, of the Institute of Cardiovascular Science, University College, London, and Ajay Gupta, MD, PhD, of the William Harvey Research Institute at Queen Mary University, London, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “More importantly, they have demonstrated a significantly stronger and increased BP-lowering effect in higher cardiovascular risk groups, such as those with hypertension or hyperlipidemia.”

They also noted that the 2.61–mm Hg reduction in SBP the study reported is “likely to be significant” on a population level. “A 2–mm Hg reduction in SBP is estimated to reduce stroke mortality by 10% and deaths from ischemic heart disease by 7%,” they wrote. “Expressed another way, an analysis in the U.S. population using 2010 data estimates that a population-wide reduction in SBP of 2 mm Hg in those aged 45- 64 years would translate to 30,045 fewer cardiovascular events ([coronary heart disease], stroke, and heart failure).”

The investigators and editorialists have no disclosures.

A meta-analysis of 71 randomized controlled trials has found the sweet spot for omega-3 fatty acid intake for lowering blood pressure: between 2 and 3 g/day. The investigators also reported that people at higher risk for cardiovascular disease may benefit from higher daily intake of omega-3.

The study analyzed data from randomized controlled trials involving 4,973 individuals and published from 1987 to 2020. Most of the trials used a combined supplementation of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Outcomes analysis involved the impact of combined DHA-EPA at 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 grams daily on average changes in both systolic and diastolic BP and compared them with the placebo or control groups who had a combined intake of 0 g/day.

“We found a significant nonlinear dose-response relationship for both SBP and DBP models,” wrote senior author Xinzhi Li, MD, PhD, and colleagues. Dr. Li is program director of the school of pharmacy at Macau University of Science and Technology in Taipa, China.

Most of the trials included in the meta-analysis evaluated fish oil supplements, but a number also included EPA and DHA omega-3 fatty acids consumed in food.

When the investigators analyzed studies that used an average baseline SBP of greater than 130 mm Hg, they found that increasing omega-3 supplementation resulted in strong reductions in SBP and DBP, but not so with people with baseline SBP below 130 mm Hg.

Across the entire cohort, average SBP and DBP changes averaged –2.61 (95% confidence interval, –3.57 to –1.65) and –1.64 (95% CI, –2.29 to –0.99) mm Hg for people taking 2 g/d omega-3 supplements, and –2.61 (95% CI, –3.52 to –1.69) and –1.80 (95% CI, –2.38 to –1.23) for those on 3 g/d. The changes weren’t as robust in higher and lower intake groups overall.

However, the higher the BP, the more robust the reductions. For those with SBP greater than 130 mm Hg, 3 g/d resulted in an average change of –3.22 mm Hg (95% CI, –5.21 to –1.23). In the greater than 80 mm Hg DBP group, 3 g/d of omega-3 resulted in an average –3.81 mm Hg reduction (95% CI, –4.48 to –1.87). In patients with BP greater than 140/90 and hypertension, the reductions were even more pronounced. And in patients with BP greater than 130/80, omega-3 intake of 4-5 g/d had a greater impact than 2-3 g/d, although that benefit didn’t carry over in the greater than 140/90 group.

High cholesterol was also a factor in determining the benefits of omega-3 supplementation on BP, as Dr. Li and colleagues wrote that they found “an approximately linear relationship” between hyperlipidemia and SBP, “suggesting that increasing supplementation was associated with greater reductions in SBP.” Likewise, the study found stronger effects on BP in studies with an average patient age greater than 45 years.

In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration issued an update that consuming combined EPA and DHA may lower BP in the general population and reduce the risk of hypertension, but that “the evidence is inconsistent and inconclusive.”

“However, while our study may add a layer of credible evidence, it does not meet the threshold to make an authorized health claim for omega-3 fatty acids in compliance with FDA regulations,” Dr. Li said.

The study addresses shortcomings of previous studies of omega-3 and BP and by identifying the optimal dose, Marc George, MRCP, PhD, of the Institute of Cardiovascular Science, University College, London, and Ajay Gupta, MD, PhD, of the William Harvey Research Institute at Queen Mary University, London, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “More importantly, they have demonstrated a significantly stronger and increased BP-lowering effect in higher cardiovascular risk groups, such as those with hypertension or hyperlipidemia.”

They also noted that the 2.61–mm Hg reduction in SBP the study reported is “likely to be significant” on a population level. “A 2–mm Hg reduction in SBP is estimated to reduce stroke mortality by 10% and deaths from ischemic heart disease by 7%,” they wrote. “Expressed another way, an analysis in the U.S. population using 2010 data estimates that a population-wide reduction in SBP of 2 mm Hg in those aged 45- 64 years would translate to 30,045 fewer cardiovascular events ([coronary heart disease], stroke, and heart failure).”

The investigators and editorialists have no disclosures.

A meta-analysis of 71 randomized controlled trials has found the sweet spot for omega-3 fatty acid intake for lowering blood pressure: between 2 and 3 g/day. The investigators also reported that people at higher risk for cardiovascular disease may benefit from higher daily intake of omega-3.

The study analyzed data from randomized controlled trials involving 4,973 individuals and published from 1987 to 2020. Most of the trials used a combined supplementation of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Outcomes analysis involved the impact of combined DHA-EPA at 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 grams daily on average changes in both systolic and diastolic BP and compared them with the placebo or control groups who had a combined intake of 0 g/day.

“We found a significant nonlinear dose-response relationship for both SBP and DBP models,” wrote senior author Xinzhi Li, MD, PhD, and colleagues. Dr. Li is program director of the school of pharmacy at Macau University of Science and Technology in Taipa, China.

Most of the trials included in the meta-analysis evaluated fish oil supplements, but a number also included EPA and DHA omega-3 fatty acids consumed in food.

When the investigators analyzed studies that used an average baseline SBP of greater than 130 mm Hg, they found that increasing omega-3 supplementation resulted in strong reductions in SBP and DBP, but not so with people with baseline SBP below 130 mm Hg.

Across the entire cohort, average SBP and DBP changes averaged –2.61 (95% confidence interval, –3.57 to –1.65) and –1.64 (95% CI, –2.29 to –0.99) mm Hg for people taking 2 g/d omega-3 supplements, and –2.61 (95% CI, –3.52 to –1.69) and –1.80 (95% CI, –2.38 to –1.23) for those on 3 g/d. The changes weren’t as robust in higher and lower intake groups overall.

However, the higher the BP, the more robust the reductions. For those with SBP greater than 130 mm Hg, 3 g/d resulted in an average change of –3.22 mm Hg (95% CI, –5.21 to –1.23). In the greater than 80 mm Hg DBP group, 3 g/d of omega-3 resulted in an average –3.81 mm Hg reduction (95% CI, –4.48 to –1.87). In patients with BP greater than 140/90 and hypertension, the reductions were even more pronounced. And in patients with BP greater than 130/80, omega-3 intake of 4-5 g/d had a greater impact than 2-3 g/d, although that benefit didn’t carry over in the greater than 140/90 group.

High cholesterol was also a factor in determining the benefits of omega-3 supplementation on BP, as Dr. Li and colleagues wrote that they found “an approximately linear relationship” between hyperlipidemia and SBP, “suggesting that increasing supplementation was associated with greater reductions in SBP.” Likewise, the study found stronger effects on BP in studies with an average patient age greater than 45 years.

In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration issued an update that consuming combined EPA and DHA may lower BP in the general population and reduce the risk of hypertension, but that “the evidence is inconsistent and inconclusive.”

“However, while our study may add a layer of credible evidence, it does not meet the threshold to make an authorized health claim for omega-3 fatty acids in compliance with FDA regulations,” Dr. Li said.

The study addresses shortcomings of previous studies of omega-3 and BP and by identifying the optimal dose, Marc George, MRCP, PhD, of the Institute of Cardiovascular Science, University College, London, and Ajay Gupta, MD, PhD, of the William Harvey Research Institute at Queen Mary University, London, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “More importantly, they have demonstrated a significantly stronger and increased BP-lowering effect in higher cardiovascular risk groups, such as those with hypertension or hyperlipidemia.”

They also noted that the 2.61–mm Hg reduction in SBP the study reported is “likely to be significant” on a population level. “A 2–mm Hg reduction in SBP is estimated to reduce stroke mortality by 10% and deaths from ischemic heart disease by 7%,” they wrote. “Expressed another way, an analysis in the U.S. population using 2010 data estimates that a population-wide reduction in SBP of 2 mm Hg in those aged 45- 64 years would translate to 30,045 fewer cardiovascular events ([coronary heart disease], stroke, and heart failure).”

The investigators and editorialists have no disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

ADA prioritizes heart failure in patients with diabetes

All U.S. patients with diabetes should undergo annual biomarker testing to allow for early diagnosis of progressive but presymptomatic heart failure, and treatment with an agent from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor class should expand among such patients to include everyone with stage B heart failure (“pre–heart failure”) or more advanced stages.

That’s a recommendation from an American Diabetes Association consensus report published June 1 in Diabetes Care.

The report notes that until now, “implementation of available strategies to detect asymptomatic heart failure [in patients with diabetes] has been suboptimal.” The remedy for this is that, “among individuals with diabetes, measurement of a natriuretic peptide or high-sensitivity cardiac troponin is recommended on at least a yearly basis to identify the earliest heart failure stages and to implement strategies to prevent transition to symptomatic heart failure.”