User login

Tricyclics may raise fracture risk in type 2 diabetes

VANCOUVER – , independent of any prevalent neuropathy, according to findings from an analysis of a large, randomized clinical trial.

Although the findings are suggestive, they don’t definitively pin blame on TCAs, said Rachel Elam, MD, who presented the study at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. “I think that there’s not enough information to conclude that tricyclic antidepressants directly lead to fractures, but I think it opens the door [to] something we should look into more. Is it being mediated by a better predictor, or is it the medication itself? I think it’s more hypothesis generating,” said Dr. Elam, an assistant professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

Patients with type 2 diabetes are known to be at increased risk of fracture, but prediction tools tend to underestimate this risk, Dr. Elam said. “Type 2 diabetes–specific clinical risk factors may be helpful for finding out fracture risk in this population,” Dr. Elam said during her talk.

Glycemic control is one candidate risk factor because advanced glycation end products are linked to reduced bone strength. Other factors include antidiabetic medication use, neuropathy, and microvascular disease, which has been linked to increased cortical porosity.

The study examined a somewhat younger population than previous surveys, having drawn from the Look AHEAD-C clinical trial, which examined the effects of an intensive lifestyle intervention on type 2 diabetes. Look AHEAD-C included 4,697 participants aged 45-75 from 16 U.S. clinical sites. Participants had a body mass index of 25.0 kg/m2 or higher and hemoglobin A1c levels of 11% or below.

Dr. Elam cited the database’s inclusion of factors like A1c levels, renal parameters, and diabetic neuropathy. “It gave us a really good population to look at those risk factors” in a large group of people with type 2 diabetes, she said.

Over a median follow-up of 16.6 years, there were 649 participants with incident first clinical fracture(s). Statistically significant factors predicting fracture risk included TCA use (hazard ratio, 2.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-4.43), female gender (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.83-2.66), insulin use (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.02-1.57), increases in A1c level (per 1% increase: HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.20), age (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01-1.04), other or mixed race/ethnicity (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.52-0.87), Hispanic White race/ethnicity (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.39-0.91), non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.26-0.47), and estrogen use (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.44-0.98).

During the Q&A session following the presentation, Elsa Strotmeyer, PhD, commented that TCAs have been linked to central nervous system pathways in falls in other populations. “It’s a very nice study. It’s important to look at the diabetes complications related to the fracture risk, but I thought that they should have emphasized some more of the diabetes complications being related to fracture rather than these tricyclic antidepressants, because that is not a unique factor to that population,” said Dr. Strotmeyer, who is an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh.

Instead, she noted a different strength of the study. “The study population is important because they’re a relatively young population with type 2 diabetes, compared to many studies [that] have been published in older populations. Showing similar things that we found in older populations was the unique piece and the important piece of this study,” Dr. Strotmeyer said.

Ultimately, the model wasn’t sufficient to be used as a fall risk predictor, but it should inform future work, according to Dr. Elam. “I think it does lay some new groundwork that when we’re looking forward, it may [help in building] other models to better predict fracture risk in type 2 diabetes. Things that would be important to include [in future models] would be medication use, such as tricyclic antidepressants,” and to make sure we include glycemic control, A1c, and insulin medication.

The study was independently funded. Dr. Elam and Dr. Strotmeyer report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

VANCOUVER – , independent of any prevalent neuropathy, according to findings from an analysis of a large, randomized clinical trial.

Although the findings are suggestive, they don’t definitively pin blame on TCAs, said Rachel Elam, MD, who presented the study at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. “I think that there’s not enough information to conclude that tricyclic antidepressants directly lead to fractures, but I think it opens the door [to] something we should look into more. Is it being mediated by a better predictor, or is it the medication itself? I think it’s more hypothesis generating,” said Dr. Elam, an assistant professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

Patients with type 2 diabetes are known to be at increased risk of fracture, but prediction tools tend to underestimate this risk, Dr. Elam said. “Type 2 diabetes–specific clinical risk factors may be helpful for finding out fracture risk in this population,” Dr. Elam said during her talk.

Glycemic control is one candidate risk factor because advanced glycation end products are linked to reduced bone strength. Other factors include antidiabetic medication use, neuropathy, and microvascular disease, which has been linked to increased cortical porosity.

The study examined a somewhat younger population than previous surveys, having drawn from the Look AHEAD-C clinical trial, which examined the effects of an intensive lifestyle intervention on type 2 diabetes. Look AHEAD-C included 4,697 participants aged 45-75 from 16 U.S. clinical sites. Participants had a body mass index of 25.0 kg/m2 or higher and hemoglobin A1c levels of 11% or below.

Dr. Elam cited the database’s inclusion of factors like A1c levels, renal parameters, and diabetic neuropathy. “It gave us a really good population to look at those risk factors” in a large group of people with type 2 diabetes, she said.

Over a median follow-up of 16.6 years, there were 649 participants with incident first clinical fracture(s). Statistically significant factors predicting fracture risk included TCA use (hazard ratio, 2.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-4.43), female gender (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.83-2.66), insulin use (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.02-1.57), increases in A1c level (per 1% increase: HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.20), age (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01-1.04), other or mixed race/ethnicity (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.52-0.87), Hispanic White race/ethnicity (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.39-0.91), non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.26-0.47), and estrogen use (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.44-0.98).

During the Q&A session following the presentation, Elsa Strotmeyer, PhD, commented that TCAs have been linked to central nervous system pathways in falls in other populations. “It’s a very nice study. It’s important to look at the diabetes complications related to the fracture risk, but I thought that they should have emphasized some more of the diabetes complications being related to fracture rather than these tricyclic antidepressants, because that is not a unique factor to that population,” said Dr. Strotmeyer, who is an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh.

Instead, she noted a different strength of the study. “The study population is important because they’re a relatively young population with type 2 diabetes, compared to many studies [that] have been published in older populations. Showing similar things that we found in older populations was the unique piece and the important piece of this study,” Dr. Strotmeyer said.

Ultimately, the model wasn’t sufficient to be used as a fall risk predictor, but it should inform future work, according to Dr. Elam. “I think it does lay some new groundwork that when we’re looking forward, it may [help in building] other models to better predict fracture risk in type 2 diabetes. Things that would be important to include [in future models] would be medication use, such as tricyclic antidepressants,” and to make sure we include glycemic control, A1c, and insulin medication.

The study was independently funded. Dr. Elam and Dr. Strotmeyer report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

VANCOUVER – , independent of any prevalent neuropathy, according to findings from an analysis of a large, randomized clinical trial.

Although the findings are suggestive, they don’t definitively pin blame on TCAs, said Rachel Elam, MD, who presented the study at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. “I think that there’s not enough information to conclude that tricyclic antidepressants directly lead to fractures, but I think it opens the door [to] something we should look into more. Is it being mediated by a better predictor, or is it the medication itself? I think it’s more hypothesis generating,” said Dr. Elam, an assistant professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

Patients with type 2 diabetes are known to be at increased risk of fracture, but prediction tools tend to underestimate this risk, Dr. Elam said. “Type 2 diabetes–specific clinical risk factors may be helpful for finding out fracture risk in this population,” Dr. Elam said during her talk.

Glycemic control is one candidate risk factor because advanced glycation end products are linked to reduced bone strength. Other factors include antidiabetic medication use, neuropathy, and microvascular disease, which has been linked to increased cortical porosity.

The study examined a somewhat younger population than previous surveys, having drawn from the Look AHEAD-C clinical trial, which examined the effects of an intensive lifestyle intervention on type 2 diabetes. Look AHEAD-C included 4,697 participants aged 45-75 from 16 U.S. clinical sites. Participants had a body mass index of 25.0 kg/m2 or higher and hemoglobin A1c levels of 11% or below.

Dr. Elam cited the database’s inclusion of factors like A1c levels, renal parameters, and diabetic neuropathy. “It gave us a really good population to look at those risk factors” in a large group of people with type 2 diabetes, she said.

Over a median follow-up of 16.6 years, there were 649 participants with incident first clinical fracture(s). Statistically significant factors predicting fracture risk included TCA use (hazard ratio, 2.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-4.43), female gender (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.83-2.66), insulin use (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.02-1.57), increases in A1c level (per 1% increase: HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.20), age (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01-1.04), other or mixed race/ethnicity (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.52-0.87), Hispanic White race/ethnicity (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.39-0.91), non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.26-0.47), and estrogen use (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.44-0.98).

During the Q&A session following the presentation, Elsa Strotmeyer, PhD, commented that TCAs have been linked to central nervous system pathways in falls in other populations. “It’s a very nice study. It’s important to look at the diabetes complications related to the fracture risk, but I thought that they should have emphasized some more of the diabetes complications being related to fracture rather than these tricyclic antidepressants, because that is not a unique factor to that population,” said Dr. Strotmeyer, who is an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh.

Instead, she noted a different strength of the study. “The study population is important because they’re a relatively young population with type 2 diabetes, compared to many studies [that] have been published in older populations. Showing similar things that we found in older populations was the unique piece and the important piece of this study,” Dr. Strotmeyer said.

Ultimately, the model wasn’t sufficient to be used as a fall risk predictor, but it should inform future work, according to Dr. Elam. “I think it does lay some new groundwork that when we’re looking forward, it may [help in building] other models to better predict fracture risk in type 2 diabetes. Things that would be important to include [in future models] would be medication use, such as tricyclic antidepressants,” and to make sure we include glycemic control, A1c, and insulin medication.

The study was independently funded. Dr. Elam and Dr. Strotmeyer report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ASBMR 2023

Treatment order evidence comes to light for premenopausal idiopathic osteoporosis: What to do after denosumab

VANCOUVER – With treatment with a bisphosphonate following sequential use of teriparatide (Forteo) and denosumab (Prolia) for premenopausal women with idiopathic osteoporosis, bone mineral density (BMD) was maintained over the first year following denosumab cessation, according to results from a small, nonrandomized extension of a phase 2 study.

Bisphosphonates are recommended for patients after they have completed a course of denosumab because cessation of the bone resorption blocker is known to increase bone turnover markers, decrease BMD, and raise the risk of vertebral fractures. Although there is evidence to support this treatment sequence for postmenopausal women, there was no evidence regarding premenopausal women with idiopathic osteoporosis, said Adi Cohen, MD, who presented the results of the study at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

In the extension study, neither length of treatment with denosumab nor transition to menopause affected BMD results. Weekly doses of alendronate (ALN) better suppressed C-terminal telopeptide (CTX) than did zoledronic acid (ZOL) and led to better maintenance of BMD than did a single dose of ZOL. The researchers suggested that single-dose ZOL may not prevent bone loss for an entire year.

It is too early to call the results practice changing, said Dr. Cohen, professor of medicine and endocrinology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, but she noted, “It’s important just to provide information about how sequences of osteoporosis medications might be used in a rare but certainly understudied group of premenopausal women with osteoporosis who need treatment, and these data hopefully will help make some treatment decisions.”

In the early 2000s, researchers initially believed that premenopausal women with low BMD had experienced some kind of temporary event and that they would likely improve on their own over time. “I think we now recognize that whatever it is that causes this is an ongoing issue and that this is a problem they’re going to have to deal with for the rest of their lives. This is something that they have to stay on top of,” said coauthor Elizabeth Shane, MD, who is a professor of medicine at CUIMC.

However, there are no practice guidelines for the management of osteoporosis in premenopausal women, according to Dr. Shane. She noted that there is controversy as to whether to treat women with low bone density who do not have a history of fractures. “I think that there’s pretty much agreement that anybody who has a lot of fractures has an early-onset form of osteoporosis. The controversy is what to do about the person who just has a low bone density and hasn’t yet fractured and what is the utility of trying to treat them at that point and perhaps prevent a fracture. I don’t think we have enough data to address that,” Dr. Shane said.

Still, the research has provided some clarity in her own practice. “I think if somebody would come to my office who had very low bone density, I would probably treat them. If they have fractures, I would definitely treat them. I think that our work has provided a framework for people to approach that,” she said.

The study was an extension of a sequential treatment approach that began with 2 years of teriparatide (20 mcg daily) followed by an extension study of 2–3 years of treatment with denosumab (60 mg every 6 months). Seven months after the last dose of denosumab, patients underwent 1 year of treatment with ALN (70 mg weekly; n = 18) or a single dose of ZOL (5 mg IV; n = 6), according to patient choice.

The original phase 2 study started with 41 women. At 24 months, teriparatide treatment led to BMD increases of 13% in the lumbar spine (LS), 5% in the total hip (TH), and 5% in the femoral neck (FN). There was a 2% decline in BMD in the forearm (distal radius [DR]). A group of 32 of the women participated in an extension study and took denosumab for 12 months. Of those patients, 29 continued to take it for another 12 months. At 12 months, BMD increased 5% in the LS, 3% in the TH, 3% in the FN, and 1% in the DR (P < .05 for all). At 24 months, BMD rose by 22%, 10%, and 10% at the first three of those locations. BMD in the DR remained stable, compared with the baseline after taking teriparatide.

The bisphosphonate phase of the extension study included 24 women (mean age, 43 years). The mean body mass index of the patients was 23.0 kg/m2. The patients had experienced a mean of 3.0 fractures in adulthood, and 38% of patients had a history of vertebral fracture.

Over 12 months of follow-up, the researchers found no statistically significant difference in BMD in the LS, TH, or FN, compared with bisphosphonate extension baseline. There was also no statistically significant change in serum CTX. There was evidence that, among patients with higher rates of bone turnover, there were higher rates of LS and FN bone loss during bisphosphonate treatment.

Among patients taking ZOL, at 12 months there was a statistically significant rise in CTX levels, but not among patients taking ALN. There were no new vertebral fractures among any participants during the bisphosphonate extension period.

The results represent critical data for an understudied population, according to Yumie Rhee, MD, PhD, who was comoderator of the session in which the study was presented. “They are showing that by using a bisphosphonate [patients] have this just slight decrease, but within error, so it’s maintaining the BMD, at least. I think it’s very important. It will be fascinating to see next year’s follow-up,” said Dr. Rhee, a professor of endocrinology at Yonsei University College of Medicine in Seoul, South Korea. “The problem with premenopausal osteoporosis is that we don’t have good evidence. Even though this study is very small, we’re just following that data, all of us.”

Comoderator Maria Zanchetta, MD, a professor of osteology at the Institute of Diagnostics and Metabolic Research, Universidad del Salvador, Buenos Aires, agreed. “We know what to do when we stop denosumab in postmenopausal women. We didn’t have any work about what to do when we stopped in premenopausal women. You can think that probably it’s going to be the same, but this is the first time you have the evidence that if you give bisphosphonate, you will maintain BMD.”

Limitations to the study include its small size and the lack of a placebo-treated control group. In addition, the bisphosphonate extension was not randomized.

The studies were funded by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Amgen. Dr. Cohen and Dr. Shane received research funding from Amgen. Dr. Rhee and Dr. Zanchetta have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

VANCOUVER – With treatment with a bisphosphonate following sequential use of teriparatide (Forteo) and denosumab (Prolia) for premenopausal women with idiopathic osteoporosis, bone mineral density (BMD) was maintained over the first year following denosumab cessation, according to results from a small, nonrandomized extension of a phase 2 study.

Bisphosphonates are recommended for patients after they have completed a course of denosumab because cessation of the bone resorption blocker is known to increase bone turnover markers, decrease BMD, and raise the risk of vertebral fractures. Although there is evidence to support this treatment sequence for postmenopausal women, there was no evidence regarding premenopausal women with idiopathic osteoporosis, said Adi Cohen, MD, who presented the results of the study at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

In the extension study, neither length of treatment with denosumab nor transition to menopause affected BMD results. Weekly doses of alendronate (ALN) better suppressed C-terminal telopeptide (CTX) than did zoledronic acid (ZOL) and led to better maintenance of BMD than did a single dose of ZOL. The researchers suggested that single-dose ZOL may not prevent bone loss for an entire year.

It is too early to call the results practice changing, said Dr. Cohen, professor of medicine and endocrinology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, but she noted, “It’s important just to provide information about how sequences of osteoporosis medications might be used in a rare but certainly understudied group of premenopausal women with osteoporosis who need treatment, and these data hopefully will help make some treatment decisions.”

In the early 2000s, researchers initially believed that premenopausal women with low BMD had experienced some kind of temporary event and that they would likely improve on their own over time. “I think we now recognize that whatever it is that causes this is an ongoing issue and that this is a problem they’re going to have to deal with for the rest of their lives. This is something that they have to stay on top of,” said coauthor Elizabeth Shane, MD, who is a professor of medicine at CUIMC.

However, there are no practice guidelines for the management of osteoporosis in premenopausal women, according to Dr. Shane. She noted that there is controversy as to whether to treat women with low bone density who do not have a history of fractures. “I think that there’s pretty much agreement that anybody who has a lot of fractures has an early-onset form of osteoporosis. The controversy is what to do about the person who just has a low bone density and hasn’t yet fractured and what is the utility of trying to treat them at that point and perhaps prevent a fracture. I don’t think we have enough data to address that,” Dr. Shane said.

Still, the research has provided some clarity in her own practice. “I think if somebody would come to my office who had very low bone density, I would probably treat them. If they have fractures, I would definitely treat them. I think that our work has provided a framework for people to approach that,” she said.

The study was an extension of a sequential treatment approach that began with 2 years of teriparatide (20 mcg daily) followed by an extension study of 2–3 years of treatment with denosumab (60 mg every 6 months). Seven months after the last dose of denosumab, patients underwent 1 year of treatment with ALN (70 mg weekly; n = 18) or a single dose of ZOL (5 mg IV; n = 6), according to patient choice.

The original phase 2 study started with 41 women. At 24 months, teriparatide treatment led to BMD increases of 13% in the lumbar spine (LS), 5% in the total hip (TH), and 5% in the femoral neck (FN). There was a 2% decline in BMD in the forearm (distal radius [DR]). A group of 32 of the women participated in an extension study and took denosumab for 12 months. Of those patients, 29 continued to take it for another 12 months. At 12 months, BMD increased 5% in the LS, 3% in the TH, 3% in the FN, and 1% in the DR (P < .05 for all). At 24 months, BMD rose by 22%, 10%, and 10% at the first three of those locations. BMD in the DR remained stable, compared with the baseline after taking teriparatide.

The bisphosphonate phase of the extension study included 24 women (mean age, 43 years). The mean body mass index of the patients was 23.0 kg/m2. The patients had experienced a mean of 3.0 fractures in adulthood, and 38% of patients had a history of vertebral fracture.

Over 12 months of follow-up, the researchers found no statistically significant difference in BMD in the LS, TH, or FN, compared with bisphosphonate extension baseline. There was also no statistically significant change in serum CTX. There was evidence that, among patients with higher rates of bone turnover, there were higher rates of LS and FN bone loss during bisphosphonate treatment.

Among patients taking ZOL, at 12 months there was a statistically significant rise in CTX levels, but not among patients taking ALN. There were no new vertebral fractures among any participants during the bisphosphonate extension period.

The results represent critical data for an understudied population, according to Yumie Rhee, MD, PhD, who was comoderator of the session in which the study was presented. “They are showing that by using a bisphosphonate [patients] have this just slight decrease, but within error, so it’s maintaining the BMD, at least. I think it’s very important. It will be fascinating to see next year’s follow-up,” said Dr. Rhee, a professor of endocrinology at Yonsei University College of Medicine in Seoul, South Korea. “The problem with premenopausal osteoporosis is that we don’t have good evidence. Even though this study is very small, we’re just following that data, all of us.”

Comoderator Maria Zanchetta, MD, a professor of osteology at the Institute of Diagnostics and Metabolic Research, Universidad del Salvador, Buenos Aires, agreed. “We know what to do when we stop denosumab in postmenopausal women. We didn’t have any work about what to do when we stopped in premenopausal women. You can think that probably it’s going to be the same, but this is the first time you have the evidence that if you give bisphosphonate, you will maintain BMD.”

Limitations to the study include its small size and the lack of a placebo-treated control group. In addition, the bisphosphonate extension was not randomized.

The studies were funded by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Amgen. Dr. Cohen and Dr. Shane received research funding from Amgen. Dr. Rhee and Dr. Zanchetta have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

VANCOUVER – With treatment with a bisphosphonate following sequential use of teriparatide (Forteo) and denosumab (Prolia) for premenopausal women with idiopathic osteoporosis, bone mineral density (BMD) was maintained over the first year following denosumab cessation, according to results from a small, nonrandomized extension of a phase 2 study.

Bisphosphonates are recommended for patients after they have completed a course of denosumab because cessation of the bone resorption blocker is known to increase bone turnover markers, decrease BMD, and raise the risk of vertebral fractures. Although there is evidence to support this treatment sequence for postmenopausal women, there was no evidence regarding premenopausal women with idiopathic osteoporosis, said Adi Cohen, MD, who presented the results of the study at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

In the extension study, neither length of treatment with denosumab nor transition to menopause affected BMD results. Weekly doses of alendronate (ALN) better suppressed C-terminal telopeptide (CTX) than did zoledronic acid (ZOL) and led to better maintenance of BMD than did a single dose of ZOL. The researchers suggested that single-dose ZOL may not prevent bone loss for an entire year.

It is too early to call the results practice changing, said Dr. Cohen, professor of medicine and endocrinology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, but she noted, “It’s important just to provide information about how sequences of osteoporosis medications might be used in a rare but certainly understudied group of premenopausal women with osteoporosis who need treatment, and these data hopefully will help make some treatment decisions.”

In the early 2000s, researchers initially believed that premenopausal women with low BMD had experienced some kind of temporary event and that they would likely improve on their own over time. “I think we now recognize that whatever it is that causes this is an ongoing issue and that this is a problem they’re going to have to deal with for the rest of their lives. This is something that they have to stay on top of,” said coauthor Elizabeth Shane, MD, who is a professor of medicine at CUIMC.

However, there are no practice guidelines for the management of osteoporosis in premenopausal women, according to Dr. Shane. She noted that there is controversy as to whether to treat women with low bone density who do not have a history of fractures. “I think that there’s pretty much agreement that anybody who has a lot of fractures has an early-onset form of osteoporosis. The controversy is what to do about the person who just has a low bone density and hasn’t yet fractured and what is the utility of trying to treat them at that point and perhaps prevent a fracture. I don’t think we have enough data to address that,” Dr. Shane said.

Still, the research has provided some clarity in her own practice. “I think if somebody would come to my office who had very low bone density, I would probably treat them. If they have fractures, I would definitely treat them. I think that our work has provided a framework for people to approach that,” she said.

The study was an extension of a sequential treatment approach that began with 2 years of teriparatide (20 mcg daily) followed by an extension study of 2–3 years of treatment with denosumab (60 mg every 6 months). Seven months after the last dose of denosumab, patients underwent 1 year of treatment with ALN (70 mg weekly; n = 18) or a single dose of ZOL (5 mg IV; n = 6), according to patient choice.

The original phase 2 study started with 41 women. At 24 months, teriparatide treatment led to BMD increases of 13% in the lumbar spine (LS), 5% in the total hip (TH), and 5% in the femoral neck (FN). There was a 2% decline in BMD in the forearm (distal radius [DR]). A group of 32 of the women participated in an extension study and took denosumab for 12 months. Of those patients, 29 continued to take it for another 12 months. At 12 months, BMD increased 5% in the LS, 3% in the TH, 3% in the FN, and 1% in the DR (P < .05 for all). At 24 months, BMD rose by 22%, 10%, and 10% at the first three of those locations. BMD in the DR remained stable, compared with the baseline after taking teriparatide.

The bisphosphonate phase of the extension study included 24 women (mean age, 43 years). The mean body mass index of the patients was 23.0 kg/m2. The patients had experienced a mean of 3.0 fractures in adulthood, and 38% of patients had a history of vertebral fracture.

Over 12 months of follow-up, the researchers found no statistically significant difference in BMD in the LS, TH, or FN, compared with bisphosphonate extension baseline. There was also no statistically significant change in serum CTX. There was evidence that, among patients with higher rates of bone turnover, there were higher rates of LS and FN bone loss during bisphosphonate treatment.

Among patients taking ZOL, at 12 months there was a statistically significant rise in CTX levels, but not among patients taking ALN. There were no new vertebral fractures among any participants during the bisphosphonate extension period.

The results represent critical data for an understudied population, according to Yumie Rhee, MD, PhD, who was comoderator of the session in which the study was presented. “They are showing that by using a bisphosphonate [patients] have this just slight decrease, but within error, so it’s maintaining the BMD, at least. I think it’s very important. It will be fascinating to see next year’s follow-up,” said Dr. Rhee, a professor of endocrinology at Yonsei University College of Medicine in Seoul, South Korea. “The problem with premenopausal osteoporosis is that we don’t have good evidence. Even though this study is very small, we’re just following that data, all of us.”

Comoderator Maria Zanchetta, MD, a professor of osteology at the Institute of Diagnostics and Metabolic Research, Universidad del Salvador, Buenos Aires, agreed. “We know what to do when we stop denosumab in postmenopausal women. We didn’t have any work about what to do when we stopped in premenopausal women. You can think that probably it’s going to be the same, but this is the first time you have the evidence that if you give bisphosphonate, you will maintain BMD.”

Limitations to the study include its small size and the lack of a placebo-treated control group. In addition, the bisphosphonate extension was not randomized.

The studies were funded by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Amgen. Dr. Cohen and Dr. Shane received research funding from Amgen. Dr. Rhee and Dr. Zanchetta have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ASBMR 2023

A focus on women with diabetes and their offspring

In 2021, diabetes and related complications was the 8th leading cause of death in the United States.1 As of 2022, more than 11% of the U.S. population had diabetes and 38% of the adult U.S. population had prediabetes.2 Diabetes is the most expensive chronic condition in the United States, where $1 of every $4 in health care costs is spent on care.3

Where this is most concerning is diabetes in pregnancy. While childbirth rates in the United States have decreased since the 2007 high of 4.32 million births4 to 3.66 million in 2021,5 the incidence of diabetes in pregnancy – both pregestational and gestational – has increased. The rate of pregestational diabetes in 2021 was 10.9 per 1,000 births, a 27% increase from 2016 (8.6 per 1,000).6 The percentage of those giving birth who also were diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) was 8.3% in 2021, up from 6.0% in 2016.7

Adverse outcomes for an infant born to a mother with diabetes include a higher risk of obesity and diabetes as adults, potentially leading to a forward-feeding cycle.

We and our colleagues established the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America in 1997 because we had witnessed too frequently the devastating diabetes-induced pregnancy complications in our patients. The mission we set forth was to provide a forum for dialogue among maternal-fetal medicine subspecialists. The three main goals we set forth to support this mission were to provide a catalyst for research, contribute to the creation and refinement of medical policies, and influence professional practices in diabetes in pregnancy.8

In the last quarter century, DPSG-NA, through its annual and biennial meetings, has brought together several hundred practitioners that include physicians, nurses, statisticians, researchers, nutritionists, and allied health professionals, among others. As a group, it has improved the detection and management of diabetes in pregnant women and their offspring through knowledge sharing and influencing policies on GDM screening, diagnosis, management, and treatment. Our members have shown that preconceptional counseling for women with diabetes can significantly reduce congenital malformation and perinatal mortality compared with those women with pregestational diabetes who receive no counseling.9,10

We have addressed a wide variety of topics including the paucity of data in determining the timing of delivery for women with diabetes and the Institute of Medicine/National Academy of Medicine recommendations of gestational weight gain and risks of not adhering to them. We have learned about new scientific discoveries that reveal underlying mechanisms to diabetes-related birth defects and potential therapeutic targets; and we have discussed the health literacy requirements, ethics, and opportunities for lifestyle intervention.11-16

But we need to do more.

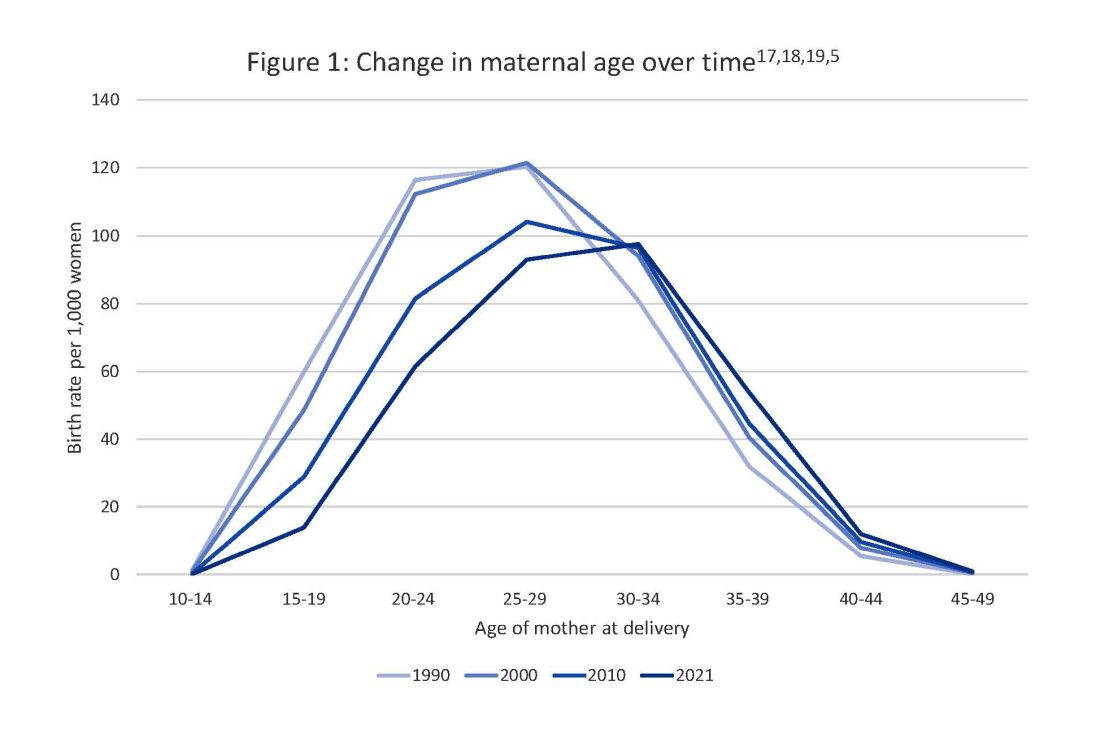

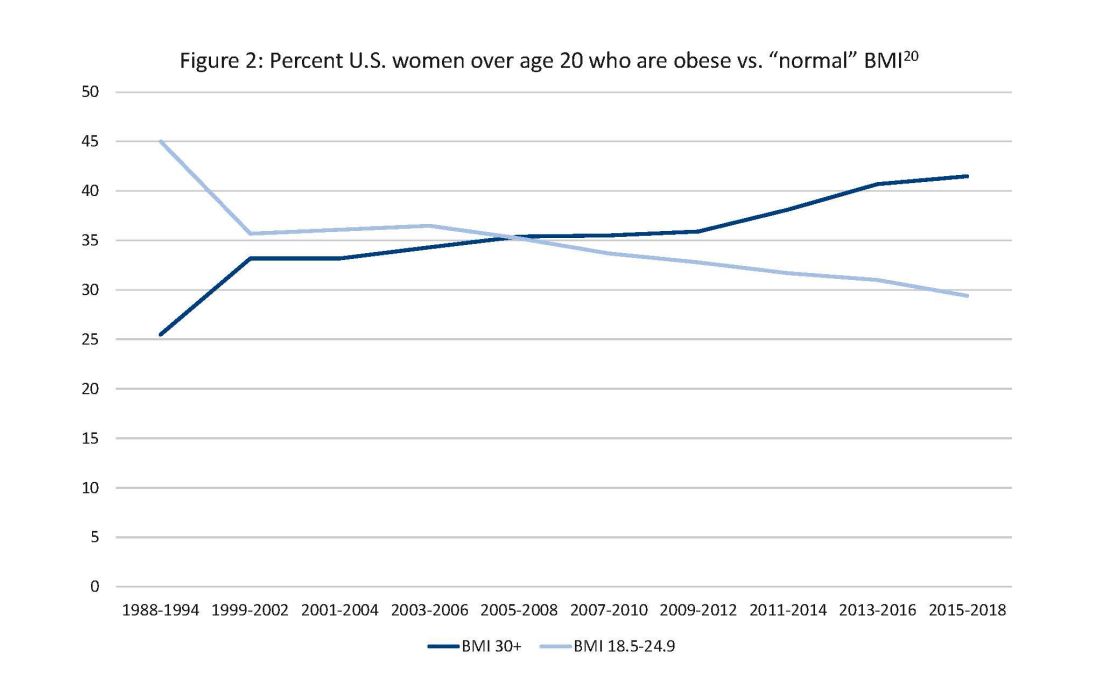

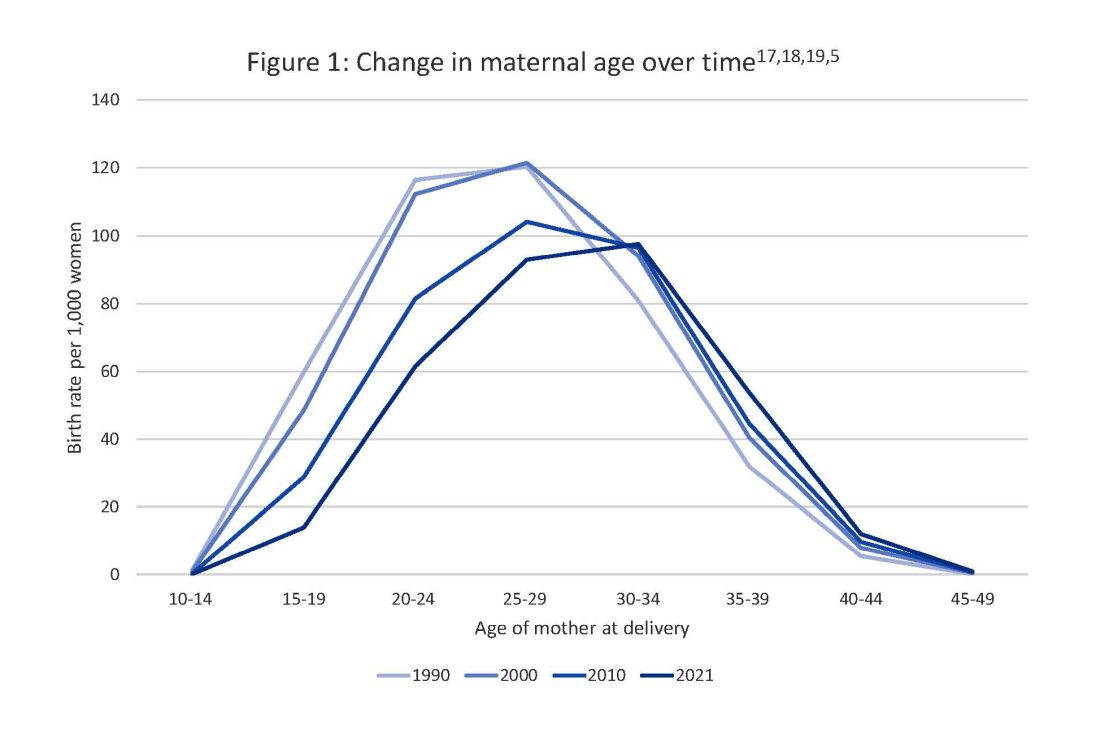

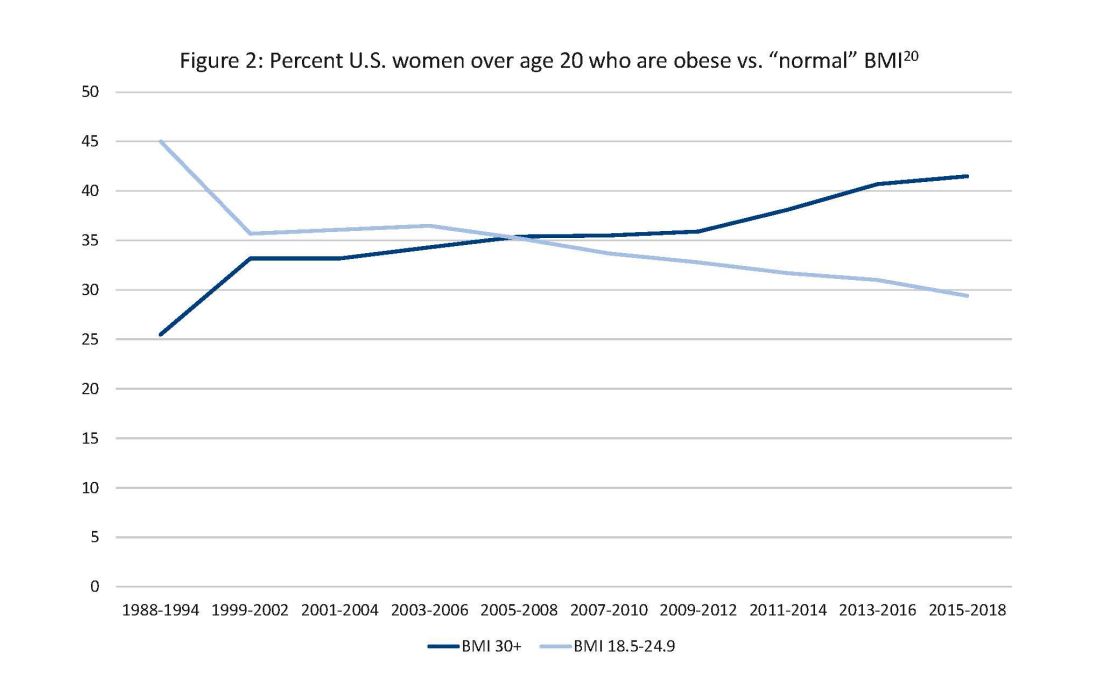

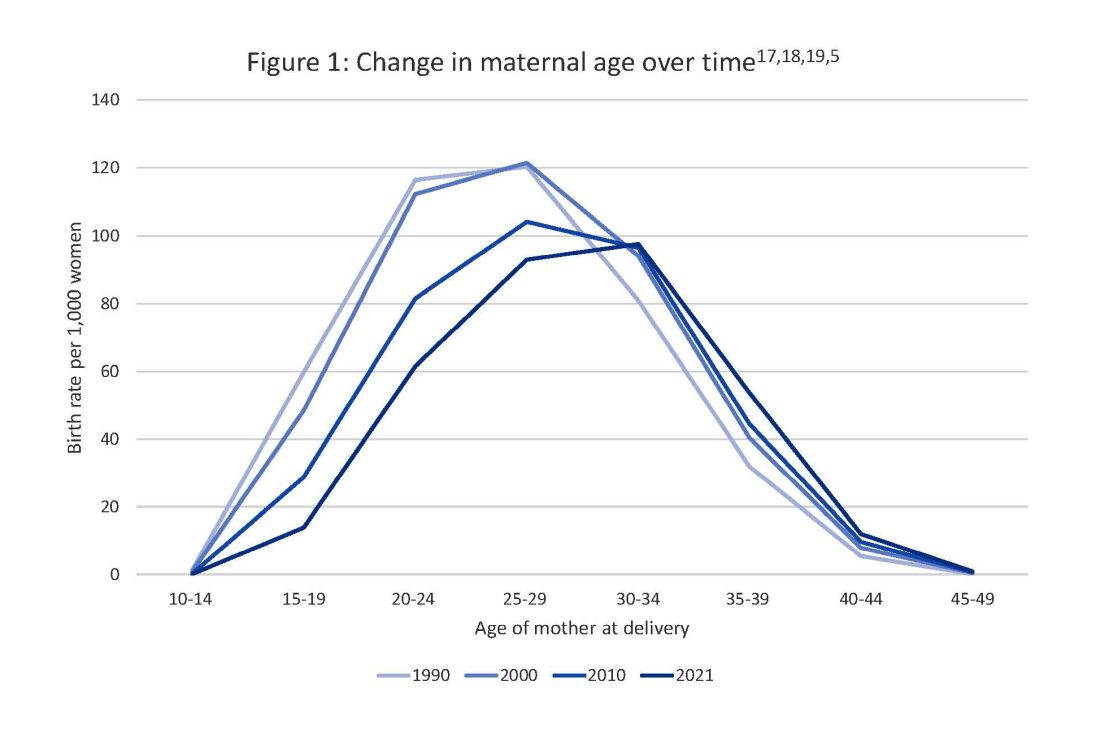

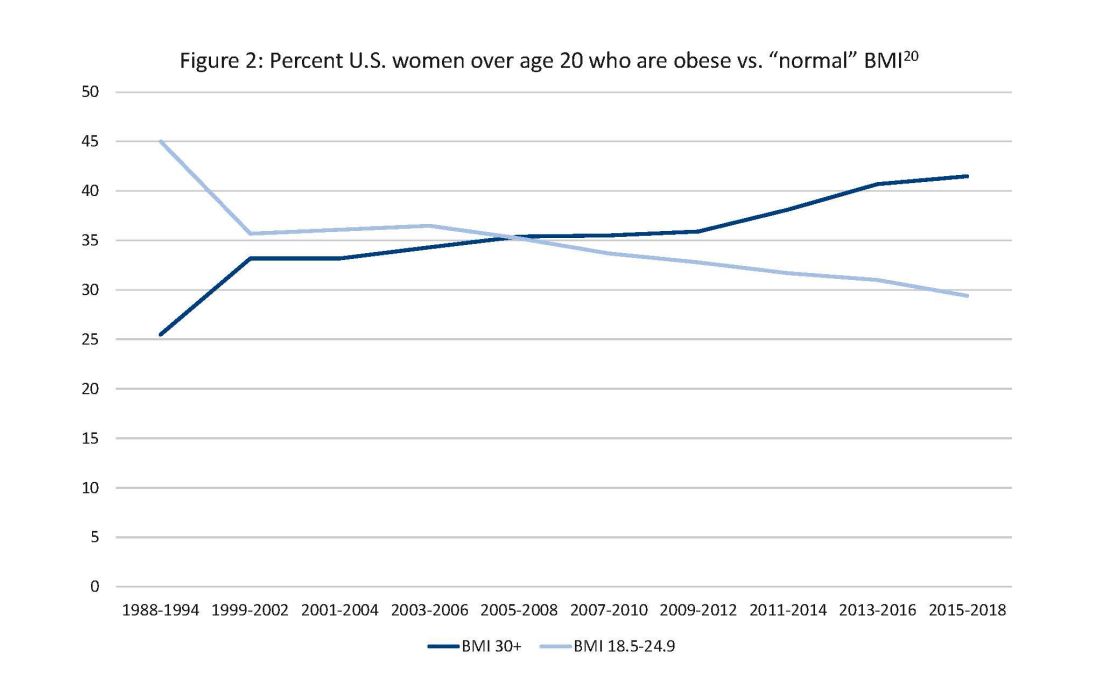

Two risk factors are at play: Women continue to choose to have babies at later ages and their pregnancies continue to be complicated by the rising incidence of obesity (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

The global obesity epidemic has become a significant concern for all aspects of health and particularly for diabetes in pregnancy.

In 1990, 24.9% of women in the United States were obese; in 2010, 35.8%; and now more than 41%. Some experts project that by 2030 more than 80% of women in the United States will be overweight or obese.21

If we are to stop this cycle of diabetes begets more diabetes, now more than ever we need to come together and accelerate the research and education around the diabetes in pregnancy. Join us at this year’s DPSG-NA meeting Oct. 26-28 to take part in the knowledge sharing, discussions, and planning. More information can be found online at https://events.dpsg-na.com/home.

Dr. Miodovnik is adjunct professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at University of Maryland School of Medicine. Dr. Reece is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences and senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research at University of Maryland School of Medicine.

References

1. Xu J et al. Mortality in the United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2022 Dec;(456):1-8. PMID: 36598387.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, diabetes data and statistics.

3. American Diabetes Association. The Cost of Diabetes.

4. Martin JA et al. Births: Final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010 Aug 9;58(24):1-85. PMID: 21254725.

5. Osterman MJK et al. Births: Final data for 2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023 Jan;72(1):1-53. PMID: 36723449.

6. Gregory ECW and Ely DM. Trends and characteristics in prepregnancy diabetes: United States, 2016-2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023 May;72(6):1-13. PMID: 37256333.

7. QuickStats: Percentage of mothers with gestational diabetes, by maternal age – National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2016 and 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 Jan 6;72(1):16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7201a4.

8. Langer O et al. The Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America – Introduction and summary statement. Prenat Neonat Med. 1998;3(6):514-6.

9. Willhoite MB et al. The impact of preconception counseling on pregnancy outcomes. The experience of the Maine Diabetes in Pregnancy Program. Diabetes Care. 1993 Feb;16(2):450-5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.2.450.

10. McElvy SS et al. A focused preconceptional and early pregnancy program in women with type 1 diabetes reduces perinatal mortality and malformation rates to general population levels. J Matern Fetal Med. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):14-20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(200001/02)9:1<14::AID-MFM5>3.0.CO;2-K.

11. Rosen JA et al. The history and contributions of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (1997-2015). Am J Perinatol. 2016 Nov;33(13):1223-6. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1585082.

12. Driggers RW and Baschat A. The 12th meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG-NA): Introduction and overview. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 Jan;25(1):3-4. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.626917.

13. Langer O et al. The proceedings of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America 2009 conference. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010 Mar;23(3):196-8. doi: 10.3109/14767050903550634.

14. Reece EA et al. A consensus report of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America Conference, Little Rock, Ark., May 2002. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002 Dec;12(6):362-4. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.6.362.364.

15. Reece EA and Maulik D. A consensus conference of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002 Dec;12(6):361. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.6.361.361.

16. Gabbe SG. Summation of the second meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG-NA). J Matern Fetal Med. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):3-9.

17. Vital Statistics of the United States 1990: Volume I – Natality.

18. Martin JA et al. Births: final data for 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2002 Feb 12;50(5):1-101. PMID: 11876093.

19. Martin JA et al. Births: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012 Aug 28;61(1):1-72. PMID: 24974589.

20. CDC Website. Normal weight, overweight, and obesity among adults aged 20 and over, by selected characteristics: United States.

21. Wang Y et al. Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and central obesity levelled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemic. Int J Epidemiol. 2020 Jun 1;49(3):810-23. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz273.

In 2021, diabetes and related complications was the 8th leading cause of death in the United States.1 As of 2022, more than 11% of the U.S. population had diabetes and 38% of the adult U.S. population had prediabetes.2 Diabetes is the most expensive chronic condition in the United States, where $1 of every $4 in health care costs is spent on care.3

Where this is most concerning is diabetes in pregnancy. While childbirth rates in the United States have decreased since the 2007 high of 4.32 million births4 to 3.66 million in 2021,5 the incidence of diabetes in pregnancy – both pregestational and gestational – has increased. The rate of pregestational diabetes in 2021 was 10.9 per 1,000 births, a 27% increase from 2016 (8.6 per 1,000).6 The percentage of those giving birth who also were diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) was 8.3% in 2021, up from 6.0% in 2016.7

Adverse outcomes for an infant born to a mother with diabetes include a higher risk of obesity and diabetes as adults, potentially leading to a forward-feeding cycle.

We and our colleagues established the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America in 1997 because we had witnessed too frequently the devastating diabetes-induced pregnancy complications in our patients. The mission we set forth was to provide a forum for dialogue among maternal-fetal medicine subspecialists. The three main goals we set forth to support this mission were to provide a catalyst for research, contribute to the creation and refinement of medical policies, and influence professional practices in diabetes in pregnancy.8

In the last quarter century, DPSG-NA, through its annual and biennial meetings, has brought together several hundred practitioners that include physicians, nurses, statisticians, researchers, nutritionists, and allied health professionals, among others. As a group, it has improved the detection and management of diabetes in pregnant women and their offspring through knowledge sharing and influencing policies on GDM screening, diagnosis, management, and treatment. Our members have shown that preconceptional counseling for women with diabetes can significantly reduce congenital malformation and perinatal mortality compared with those women with pregestational diabetes who receive no counseling.9,10

We have addressed a wide variety of topics including the paucity of data in determining the timing of delivery for women with diabetes and the Institute of Medicine/National Academy of Medicine recommendations of gestational weight gain and risks of not adhering to them. We have learned about new scientific discoveries that reveal underlying mechanisms to diabetes-related birth defects and potential therapeutic targets; and we have discussed the health literacy requirements, ethics, and opportunities for lifestyle intervention.11-16

But we need to do more.

Two risk factors are at play: Women continue to choose to have babies at later ages and their pregnancies continue to be complicated by the rising incidence of obesity (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

The global obesity epidemic has become a significant concern for all aspects of health and particularly for diabetes in pregnancy.

In 1990, 24.9% of women in the United States were obese; in 2010, 35.8%; and now more than 41%. Some experts project that by 2030 more than 80% of women in the United States will be overweight or obese.21

If we are to stop this cycle of diabetes begets more diabetes, now more than ever we need to come together and accelerate the research and education around the diabetes in pregnancy. Join us at this year’s DPSG-NA meeting Oct. 26-28 to take part in the knowledge sharing, discussions, and planning. More information can be found online at https://events.dpsg-na.com/home.

Dr. Miodovnik is adjunct professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at University of Maryland School of Medicine. Dr. Reece is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences and senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research at University of Maryland School of Medicine.

References

1. Xu J et al. Mortality in the United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2022 Dec;(456):1-8. PMID: 36598387.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, diabetes data and statistics.

3. American Diabetes Association. The Cost of Diabetes.

4. Martin JA et al. Births: Final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010 Aug 9;58(24):1-85. PMID: 21254725.

5. Osterman MJK et al. Births: Final data for 2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023 Jan;72(1):1-53. PMID: 36723449.

6. Gregory ECW and Ely DM. Trends and characteristics in prepregnancy diabetes: United States, 2016-2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023 May;72(6):1-13. PMID: 37256333.

7. QuickStats: Percentage of mothers with gestational diabetes, by maternal age – National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2016 and 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 Jan 6;72(1):16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7201a4.

8. Langer O et al. The Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America – Introduction and summary statement. Prenat Neonat Med. 1998;3(6):514-6.

9. Willhoite MB et al. The impact of preconception counseling on pregnancy outcomes. The experience of the Maine Diabetes in Pregnancy Program. Diabetes Care. 1993 Feb;16(2):450-5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.2.450.

10. McElvy SS et al. A focused preconceptional and early pregnancy program in women with type 1 diabetes reduces perinatal mortality and malformation rates to general population levels. J Matern Fetal Med. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):14-20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(200001/02)9:1<14::AID-MFM5>3.0.CO;2-K.

11. Rosen JA et al. The history and contributions of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (1997-2015). Am J Perinatol. 2016 Nov;33(13):1223-6. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1585082.

12. Driggers RW and Baschat A. The 12th meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG-NA): Introduction and overview. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 Jan;25(1):3-4. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.626917.

13. Langer O et al. The proceedings of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America 2009 conference. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010 Mar;23(3):196-8. doi: 10.3109/14767050903550634.

14. Reece EA et al. A consensus report of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America Conference, Little Rock, Ark., May 2002. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002 Dec;12(6):362-4. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.6.362.364.

15. Reece EA and Maulik D. A consensus conference of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002 Dec;12(6):361. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.6.361.361.

16. Gabbe SG. Summation of the second meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG-NA). J Matern Fetal Med. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):3-9.

17. Vital Statistics of the United States 1990: Volume I – Natality.

18. Martin JA et al. Births: final data for 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2002 Feb 12;50(5):1-101. PMID: 11876093.

19. Martin JA et al. Births: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012 Aug 28;61(1):1-72. PMID: 24974589.

20. CDC Website. Normal weight, overweight, and obesity among adults aged 20 and over, by selected characteristics: United States.

21. Wang Y et al. Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and central obesity levelled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemic. Int J Epidemiol. 2020 Jun 1;49(3):810-23. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz273.

In 2021, diabetes and related complications was the 8th leading cause of death in the United States.1 As of 2022, more than 11% of the U.S. population had diabetes and 38% of the adult U.S. population had prediabetes.2 Diabetes is the most expensive chronic condition in the United States, where $1 of every $4 in health care costs is spent on care.3

Where this is most concerning is diabetes in pregnancy. While childbirth rates in the United States have decreased since the 2007 high of 4.32 million births4 to 3.66 million in 2021,5 the incidence of diabetes in pregnancy – both pregestational and gestational – has increased. The rate of pregestational diabetes in 2021 was 10.9 per 1,000 births, a 27% increase from 2016 (8.6 per 1,000).6 The percentage of those giving birth who also were diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) was 8.3% in 2021, up from 6.0% in 2016.7

Adverse outcomes for an infant born to a mother with diabetes include a higher risk of obesity and diabetes as adults, potentially leading to a forward-feeding cycle.

We and our colleagues established the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America in 1997 because we had witnessed too frequently the devastating diabetes-induced pregnancy complications in our patients. The mission we set forth was to provide a forum for dialogue among maternal-fetal medicine subspecialists. The three main goals we set forth to support this mission were to provide a catalyst for research, contribute to the creation and refinement of medical policies, and influence professional practices in diabetes in pregnancy.8

In the last quarter century, DPSG-NA, through its annual and biennial meetings, has brought together several hundred practitioners that include physicians, nurses, statisticians, researchers, nutritionists, and allied health professionals, among others. As a group, it has improved the detection and management of diabetes in pregnant women and their offspring through knowledge sharing and influencing policies on GDM screening, diagnosis, management, and treatment. Our members have shown that preconceptional counseling for women with diabetes can significantly reduce congenital malformation and perinatal mortality compared with those women with pregestational diabetes who receive no counseling.9,10

We have addressed a wide variety of topics including the paucity of data in determining the timing of delivery for women with diabetes and the Institute of Medicine/National Academy of Medicine recommendations of gestational weight gain and risks of not adhering to them. We have learned about new scientific discoveries that reveal underlying mechanisms to diabetes-related birth defects and potential therapeutic targets; and we have discussed the health literacy requirements, ethics, and opportunities for lifestyle intervention.11-16

But we need to do more.

Two risk factors are at play: Women continue to choose to have babies at later ages and their pregnancies continue to be complicated by the rising incidence of obesity (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

The global obesity epidemic has become a significant concern for all aspects of health and particularly for diabetes in pregnancy.

In 1990, 24.9% of women in the United States were obese; in 2010, 35.8%; and now more than 41%. Some experts project that by 2030 more than 80% of women in the United States will be overweight or obese.21

If we are to stop this cycle of diabetes begets more diabetes, now more than ever we need to come together and accelerate the research and education around the diabetes in pregnancy. Join us at this year’s DPSG-NA meeting Oct. 26-28 to take part in the knowledge sharing, discussions, and planning. More information can be found online at https://events.dpsg-na.com/home.

Dr. Miodovnik is adjunct professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at University of Maryland School of Medicine. Dr. Reece is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences and senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research at University of Maryland School of Medicine.

References

1. Xu J et al. Mortality in the United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2022 Dec;(456):1-8. PMID: 36598387.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, diabetes data and statistics.

3. American Diabetes Association. The Cost of Diabetes.

4. Martin JA et al. Births: Final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010 Aug 9;58(24):1-85. PMID: 21254725.

5. Osterman MJK et al. Births: Final data for 2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023 Jan;72(1):1-53. PMID: 36723449.

6. Gregory ECW and Ely DM. Trends and characteristics in prepregnancy diabetes: United States, 2016-2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023 May;72(6):1-13. PMID: 37256333.

7. QuickStats: Percentage of mothers with gestational diabetes, by maternal age – National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2016 and 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 Jan 6;72(1):16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7201a4.

8. Langer O et al. The Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America – Introduction and summary statement. Prenat Neonat Med. 1998;3(6):514-6.

9. Willhoite MB et al. The impact of preconception counseling on pregnancy outcomes. The experience of the Maine Diabetes in Pregnancy Program. Diabetes Care. 1993 Feb;16(2):450-5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.2.450.

10. McElvy SS et al. A focused preconceptional and early pregnancy program in women with type 1 diabetes reduces perinatal mortality and malformation rates to general population levels. J Matern Fetal Med. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):14-20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(200001/02)9:1<14::AID-MFM5>3.0.CO;2-K.

11. Rosen JA et al. The history and contributions of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (1997-2015). Am J Perinatol. 2016 Nov;33(13):1223-6. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1585082.

12. Driggers RW and Baschat A. The 12th meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG-NA): Introduction and overview. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 Jan;25(1):3-4. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.626917.

13. Langer O et al. The proceedings of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America 2009 conference. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010 Mar;23(3):196-8. doi: 10.3109/14767050903550634.

14. Reece EA et al. A consensus report of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America Conference, Little Rock, Ark., May 2002. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002 Dec;12(6):362-4. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.6.362.364.

15. Reece EA and Maulik D. A consensus conference of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002 Dec;12(6):361. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.6.361.361.

16. Gabbe SG. Summation of the second meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG-NA). J Matern Fetal Med. 2000 Jan-Feb;9(1):3-9.

17. Vital Statistics of the United States 1990: Volume I – Natality.

18. Martin JA et al. Births: final data for 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2002 Feb 12;50(5):1-101. PMID: 11876093.

19. Martin JA et al. Births: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012 Aug 28;61(1):1-72. PMID: 24974589.

20. CDC Website. Normal weight, overweight, and obesity among adults aged 20 and over, by selected characteristics: United States.

21. Wang Y et al. Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and central obesity levelled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemic. Int J Epidemiol. 2020 Jun 1;49(3):810-23. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz273.

Taking a new obesity drug and birth control pills? Be careful

For women who are obese, daily life is wrought with landmines. Whether it’s the challenges of air travel because plane seats are too small, the need to shield themselves from the world’s discriminating eyes, or the great lengths many will go to achieve better health and the promise of longevity, navigating life as an obese person requires a thick skin.

So, it’s no wonder so many are willing to pay more than $1,000 a month out of pocket to get their hands on drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy) or tirzepatide (Mounjaro). The benefits of these drugs, which are part of a new class called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, include significant and rapid weight loss, blood sugar control, and improved life quality; they are unprecedented in a setting where surgery has long been considered the most effective long-term option.

On the flip side, the desire for rapid weight loss and better blood sugar control also comes with an unexpected cost. , making an unintended pregnancy more likely.

Neel Shah, MD, an endocrinologist and associate professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said he has had several patients become pregnant without intending to.

“It was when Mounjaro came out on the market when we started using it,” he said of the drug the Food and Drug Administration approved for type 2 diabetes in 2022. “It [the warning] was in the product insert, but clinically speaking, I don’t know if it was at the top of providers’ minds when they were prescribing Mounjaro.”

When asked if he believed that we were going to be seeing a significant increase in so-called Mounjaro babies, Dr. Shah was sure in his response.

“Absolutely. We will because the sheer volume [of patients] will increase,” he said.

It’s all in the gut

One of the ways that drugs like Mounjaro work is by delaying the time that it takes for food to move from the stomach to the small intestine. Although data are still evolving, it is believed that this process – delayed gastric emptying – may affect the absorption of birth control pills.

Dr. Shah said another theory is that vomiting, which is a common side effect of these types of drugs, also affects the pills’ ability to prevent pregnancy.

And “there’s a prolonged period of ramping up the dose because of the GI side effects,” said Pinar Kodaman, MD, PhD, a reproductive endocrinologist and assistant professor of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

“Initially, at the lowest dose, there may not be a lot of potential effect on absorption and gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes more common, and it can cause diarrhea, which is another condition that can affect the absorption of any medication,” she said.

Unanticipated outcomes, extra prevention

Roughly 42% of women in the United States are obese, 40% of whom are between the ages of 20 and 39. Although these new drugs can improve fertility outcomes for women who are obese (especially those with polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS), only one – Mounjaro – currently carries a warning about birth control pill effectiveness on its label. Unfortunately, it appears that some doctors are unaware or not counseling patients about this risk, and the data are unclear about whether other drugs in this class, like Ozempic and Wegovy, have the same risks.

“To date, it hasn’t been a typical thing that we counsel about,” said Dr. Kodaman. “It’s all fairly new, but when we have patients on birth control pills, we do review other medications that they are on because some can affect efficacy, and it’s something to keep in mind.”

It’s also unclear if other forms of birth control – for example, birth control patches that deliver through the skin – might carry similar pregnancy risks. Dr. Shah said some of his patients who became pregnant without intending to were using these patches. This raises even more questions, since they deliver drugs through the skin directly into the bloodstream and not through the GI system.

What can women do to help ensure that they don’t become pregnant while using these drugs?

“I really think that if patients want to protect themselves from an unplanned pregnancy, that as soon as they start the GLP receptor agonists, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to use condoms, because the onset of action is pretty quick,” said Dr. Kodaman, noting also that “at the lowest dose there may not be a lot of potential effect on gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes much more common or can cause diarrhea.”

Dr. Shah said that in his practice he’s “been telling patients to add barrier contraception” 4 weeks before they start their first dose “and at any dose adjustment.”

Zoobia Chaudhry, an obesity medicine doctor and assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, recommends that “patients just make sure that the injection and medication that they take are at least 1 hour apart.”

“Most of the time, patients do take birth control before bedtime, so if the two are spaced, it should be OK,” she said.

Another option is for women to speak to their doctors about other contraceptive options like IUDs or implantable rods, where gastric absorption is not going to be an issue.

“There’s very little research on this class of drugs,” said Emily Goodstein, a 40-year-old small-business owner in Washington, who recently switched from Ozempic to Mounjaro. “Being a person who lives in a larger body is such a horrifying experience because of the way that the world discriminates against you.”

She appreciates the feeling of being proactive that these new drugs grant. It has “opened up a bunch of opportunities for me to be seen as a full individual by the medical establishment,” she said. “I was willing to take the risk, knowing that I would be on these drugs for the rest of my life.”

In addition to being what Dr. Goodstein refers to as a guinea pig, she said she made sure that her primary care doctor was aware that she was not trying or planning to become pregnant again. (She has a 3-year-old child.) Still, her doctor mentioned only the most common side effects linked to these drugs, like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, and did not mention the risk of pregnancy.

“Folks are really not talking about the reproductive implications,” she said, referring to members of a Facebook group on these drugs that she belongs to.

Like patients themselves, many doctors are just beginning to get their arms around these agents. “Awareness, education, provider involvement, and having a multidisciplinary team could help patients achieve the goals that they set out for themselves,” said Dr. Shah.

Clear conversations are key.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

For women who are obese, daily life is wrought with landmines. Whether it’s the challenges of air travel because plane seats are too small, the need to shield themselves from the world’s discriminating eyes, or the great lengths many will go to achieve better health and the promise of longevity, navigating life as an obese person requires a thick skin.

So, it’s no wonder so many are willing to pay more than $1,000 a month out of pocket to get their hands on drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy) or tirzepatide (Mounjaro). The benefits of these drugs, which are part of a new class called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, include significant and rapid weight loss, blood sugar control, and improved life quality; they are unprecedented in a setting where surgery has long been considered the most effective long-term option.

On the flip side, the desire for rapid weight loss and better blood sugar control also comes with an unexpected cost. , making an unintended pregnancy more likely.

Neel Shah, MD, an endocrinologist and associate professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said he has had several patients become pregnant without intending to.

“It was when Mounjaro came out on the market when we started using it,” he said of the drug the Food and Drug Administration approved for type 2 diabetes in 2022. “It [the warning] was in the product insert, but clinically speaking, I don’t know if it was at the top of providers’ minds when they were prescribing Mounjaro.”

When asked if he believed that we were going to be seeing a significant increase in so-called Mounjaro babies, Dr. Shah was sure in his response.

“Absolutely. We will because the sheer volume [of patients] will increase,” he said.

It’s all in the gut

One of the ways that drugs like Mounjaro work is by delaying the time that it takes for food to move from the stomach to the small intestine. Although data are still evolving, it is believed that this process – delayed gastric emptying – may affect the absorption of birth control pills.

Dr. Shah said another theory is that vomiting, which is a common side effect of these types of drugs, also affects the pills’ ability to prevent pregnancy.

And “there’s a prolonged period of ramping up the dose because of the GI side effects,” said Pinar Kodaman, MD, PhD, a reproductive endocrinologist and assistant professor of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

“Initially, at the lowest dose, there may not be a lot of potential effect on absorption and gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes more common, and it can cause diarrhea, which is another condition that can affect the absorption of any medication,” she said.

Unanticipated outcomes, extra prevention

Roughly 42% of women in the United States are obese, 40% of whom are between the ages of 20 and 39. Although these new drugs can improve fertility outcomes for women who are obese (especially those with polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS), only one – Mounjaro – currently carries a warning about birth control pill effectiveness on its label. Unfortunately, it appears that some doctors are unaware or not counseling patients about this risk, and the data are unclear about whether other drugs in this class, like Ozempic and Wegovy, have the same risks.

“To date, it hasn’t been a typical thing that we counsel about,” said Dr. Kodaman. “It’s all fairly new, but when we have patients on birth control pills, we do review other medications that they are on because some can affect efficacy, and it’s something to keep in mind.”

It’s also unclear if other forms of birth control – for example, birth control patches that deliver through the skin – might carry similar pregnancy risks. Dr. Shah said some of his patients who became pregnant without intending to were using these patches. This raises even more questions, since they deliver drugs through the skin directly into the bloodstream and not through the GI system.

What can women do to help ensure that they don’t become pregnant while using these drugs?

“I really think that if patients want to protect themselves from an unplanned pregnancy, that as soon as they start the GLP receptor agonists, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to use condoms, because the onset of action is pretty quick,” said Dr. Kodaman, noting also that “at the lowest dose there may not be a lot of potential effect on gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes much more common or can cause diarrhea.”

Dr. Shah said that in his practice he’s “been telling patients to add barrier contraception” 4 weeks before they start their first dose “and at any dose adjustment.”

Zoobia Chaudhry, an obesity medicine doctor and assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, recommends that “patients just make sure that the injection and medication that they take are at least 1 hour apart.”

“Most of the time, patients do take birth control before bedtime, so if the two are spaced, it should be OK,” she said.

Another option is for women to speak to their doctors about other contraceptive options like IUDs or implantable rods, where gastric absorption is not going to be an issue.

“There’s very little research on this class of drugs,” said Emily Goodstein, a 40-year-old small-business owner in Washington, who recently switched from Ozempic to Mounjaro. “Being a person who lives in a larger body is such a horrifying experience because of the way that the world discriminates against you.”

She appreciates the feeling of being proactive that these new drugs grant. It has “opened up a bunch of opportunities for me to be seen as a full individual by the medical establishment,” she said. “I was willing to take the risk, knowing that I would be on these drugs for the rest of my life.”

In addition to being what Dr. Goodstein refers to as a guinea pig, she said she made sure that her primary care doctor was aware that she was not trying or planning to become pregnant again. (She has a 3-year-old child.) Still, her doctor mentioned only the most common side effects linked to these drugs, like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, and did not mention the risk of pregnancy.

“Folks are really not talking about the reproductive implications,” she said, referring to members of a Facebook group on these drugs that she belongs to.

Like patients themselves, many doctors are just beginning to get their arms around these agents. “Awareness, education, provider involvement, and having a multidisciplinary team could help patients achieve the goals that they set out for themselves,” said Dr. Shah.

Clear conversations are key.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

For women who are obese, daily life is wrought with landmines. Whether it’s the challenges of air travel because plane seats are too small, the need to shield themselves from the world’s discriminating eyes, or the great lengths many will go to achieve better health and the promise of longevity, navigating life as an obese person requires a thick skin.

So, it’s no wonder so many are willing to pay more than $1,000 a month out of pocket to get their hands on drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy) or tirzepatide (Mounjaro). The benefits of these drugs, which are part of a new class called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, include significant and rapid weight loss, blood sugar control, and improved life quality; they are unprecedented in a setting where surgery has long been considered the most effective long-term option.

On the flip side, the desire for rapid weight loss and better blood sugar control also comes with an unexpected cost. , making an unintended pregnancy more likely.

Neel Shah, MD, an endocrinologist and associate professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said he has had several patients become pregnant without intending to.

“It was when Mounjaro came out on the market when we started using it,” he said of the drug the Food and Drug Administration approved for type 2 diabetes in 2022. “It [the warning] was in the product insert, but clinically speaking, I don’t know if it was at the top of providers’ minds when they were prescribing Mounjaro.”

When asked if he believed that we were going to be seeing a significant increase in so-called Mounjaro babies, Dr. Shah was sure in his response.

“Absolutely. We will because the sheer volume [of patients] will increase,” he said.

It’s all in the gut

One of the ways that drugs like Mounjaro work is by delaying the time that it takes for food to move from the stomach to the small intestine. Although data are still evolving, it is believed that this process – delayed gastric emptying – may affect the absorption of birth control pills.

Dr. Shah said another theory is that vomiting, which is a common side effect of these types of drugs, also affects the pills’ ability to prevent pregnancy.

And “there’s a prolonged period of ramping up the dose because of the GI side effects,” said Pinar Kodaman, MD, PhD, a reproductive endocrinologist and assistant professor of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

“Initially, at the lowest dose, there may not be a lot of potential effect on absorption and gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes more common, and it can cause diarrhea, which is another condition that can affect the absorption of any medication,” she said.

Unanticipated outcomes, extra prevention

Roughly 42% of women in the United States are obese, 40% of whom are between the ages of 20 and 39. Although these new drugs can improve fertility outcomes for women who are obese (especially those with polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS), only one – Mounjaro – currently carries a warning about birth control pill effectiveness on its label. Unfortunately, it appears that some doctors are unaware or not counseling patients about this risk, and the data are unclear about whether other drugs in this class, like Ozempic and Wegovy, have the same risks.

“To date, it hasn’t been a typical thing that we counsel about,” said Dr. Kodaman. “It’s all fairly new, but when we have patients on birth control pills, we do review other medications that they are on because some can affect efficacy, and it’s something to keep in mind.”

It’s also unclear if other forms of birth control – for example, birth control patches that deliver through the skin – might carry similar pregnancy risks. Dr. Shah said some of his patients who became pregnant without intending to were using these patches. This raises even more questions, since they deliver drugs through the skin directly into the bloodstream and not through the GI system.

What can women do to help ensure that they don’t become pregnant while using these drugs?

“I really think that if patients want to protect themselves from an unplanned pregnancy, that as soon as they start the GLP receptor agonists, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to use condoms, because the onset of action is pretty quick,” said Dr. Kodaman, noting also that “at the lowest dose there may not be a lot of potential effect on gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes much more common or can cause diarrhea.”

Dr. Shah said that in his practice he’s “been telling patients to add barrier contraception” 4 weeks before they start their first dose “and at any dose adjustment.”

Zoobia Chaudhry, an obesity medicine doctor and assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, recommends that “patients just make sure that the injection and medication that they take are at least 1 hour apart.”

“Most of the time, patients do take birth control before bedtime, so if the two are spaced, it should be OK,” she said.

Another option is for women to speak to their doctors about other contraceptive options like IUDs or implantable rods, where gastric absorption is not going to be an issue.

“There’s very little research on this class of drugs,” said Emily Goodstein, a 40-year-old small-business owner in Washington, who recently switched from Ozempic to Mounjaro. “Being a person who lives in a larger body is such a horrifying experience because of the way that the world discriminates against you.”

She appreciates the feeling of being proactive that these new drugs grant. It has “opened up a bunch of opportunities for me to be seen as a full individual by the medical establishment,” she said. “I was willing to take the risk, knowing that I would be on these drugs for the rest of my life.”

In addition to being what Dr. Goodstein refers to as a guinea pig, she said she made sure that her primary care doctor was aware that she was not trying or planning to become pregnant again. (She has a 3-year-old child.) Still, her doctor mentioned only the most common side effects linked to these drugs, like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, and did not mention the risk of pregnancy.

“Folks are really not talking about the reproductive implications,” she said, referring to members of a Facebook group on these drugs that she belongs to.

Like patients themselves, many doctors are just beginning to get their arms around these agents. “Awareness, education, provider involvement, and having a multidisciplinary team could help patients achieve the goals that they set out for themselves,” said Dr. Shah.

Clear conversations are key.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Scientists find the ‘on’ switch for energy-burning brown fat

A process your body uses to stay warm in cool weather could one day lead to new therapies for obesity.

Scientists have, for the first time, mapped the precise nerve pathways that activate brown fat, or brown adipose tissue (BAT), a specialized fat that generates heat. Low temperatures kick brown fat into gear, helping the body keep its temperature and burning calories in the process.

“It has long been speculated that activating this type of fat may be useful in treating obesity and related metabolic conditions,” said Preethi Srikanthan, MD, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine who oversaw the research at the UCLA School of Medicine. “The challenge has been finding a way of selectively stimulating [it].”

Brown fat is different from the fat typically linked to obesity: the kind that accumulates around the belly, hips, and thighs. That’s white fat. White fat stores energy; brown fat burns it. That’s because brown fat cells have more mitochondria, a part of the cell that generates energy.

After dissecting the necks of eight human cadavers, Dr. Srikanthan and her team traced the sympathetic nerve branches in the fat pad above the collarbone – where the largest depot of brown fat in adults is stored. They stained the nerves, took samples, and viewed them under a microscope.

They found that nerves from brown fat traveled to the third and fourth cranial nerves of the brain, bundles of nerve fibers that control blinking and some eye movements.

In a previous case study, damage to these nerves appeared to block a chemical tracer from reaching brown fat. , Dr. Srikanthan said.

A possible mechanism for Ozempic?

Brown fat has already been linked to at least one breakthrough in obesity treatment. Some evidence suggests that popular medications like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro) may affect brown fat activity. These belong to a class of drugs known as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. They work by mimicking the hormone GLP-1, which is released in the gut and brain in response to eating glucose (sugary foods or drinks).