User login

CDC expands Zika virus travel warnings; more U.S. cases confirmed

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued an expanded travel alert for regions where travelers may be at risk of contracting Zika virus.

The mosquito-borne flavivirus may be associated with an increased risk of microcephaly and other intracranial and neurologic abnormalities in infants whose mothers were infected with Zika virus during pregnancy. Women who are pregnant or considering becoming pregnant should consider avoiding travel to countries included in the Zika virus alert.

The CDC’s expanded warning includes Barbados, Bolivia, Ecuador, Guadeloupe, Saint Martin, Guyana, Cape Verde, and Samoa. This is in addition to the previous travel alert for Puerto Rico (a U.S. territory), Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, and Venezuela.

In the United States, about a dozen cases of Zika virus have been reported, according to the CDC. States thus far where individuals have tested positive for the virus are Texas, Florida, Illinois, New Jersey, and Hawaii. These dozen cases include two pregnant women who tested positive for the Zika virus in Illinois this week. In Hawaii, a woman who had lived in Brazil while pregnant has given birth to a baby with microcephaly and congenital Zika virus infection. To date, all confirmed cases of Zika virus in the U.S. have been in individuals who traveled to areas with Zika virus transmission.

Zika virus, a member of the family of viruses that includes dengue fever, is spread by mosquitoes of the Aedes species, according to Dr. Amesh Adalja.

Dr. Adalja, a member of the public health committee of the Infectious Disease Society of America and an instructor in the department of infectious diseases at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, noted that though the virus has been known since the 1940s, “it was not considered a major public health threat” because of the generally mild course of the disease.

Infection is asymptomatic in 80% of individuals, he said. Symptoms of Zika virus infection, if they appear, include initial fever, a maculopapular rash, arthralgia, and sometimes conjunctivitis. There is no treatment for the disease and care is supportive.

A recent explosion of Zika virus cases in Brazil, however, has been associated with a large increase in cases of microcephaly in newborns. Though the association has not been confirmed, Zika virus has been found in infants born with microcephaly and in the placentas of mothers of babies with microcephaly.

The CDC has issued interim guidance for diagnosis, treatment, and management of suspected Zika virus in pregnant women. All pregnant women should be asked about travel to countries with known Zika virus exposure, with surveillance by fetal ultrasound and, in some cases, testing for Zika virus guided by symptoms and likelihood of exposure.

The CDC recommends vigilance against mosquito bites for pregnant women who do travel to areas with Zika virus activity, including the use of effective insect repellent, protective clothing, and remaining in and sleeping in air-conditioned rooms when possible.

In the United States, there is reason to be concerned about Zika virus, since “the scale of travel is very, very high” to the Central and South American and Caribbean countries where Zika virus transmission is active, Dr. Adalja said. However, since the same vector also transmits dengue fever and the Chikungunya virus – currently the focus of increasing concern in the U.S. – aggressive vector control measures are already underway in parts of the country where Aedes species mosquitoes are resident.

Though the consequences of the apparent association between maternal Zika virus infection and infant microcephaly are devastating, said Dr. Adalja, “it’s important that people put this in the proper public health perspective. Dengue fever kills thousands of people each year.”*

Dr. Adalja said that he expects commercially available testing for Zika virus to be developed; currently, testing is currently only available from the CDC and from some states’ departments of public health.

Additional resources for physicians

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories

CDC: www.cdc.gov/zika/

*Correction, 1/25/2016: An earlier version of this story misstated the number of deaths from dengue fever.

On Twitter @karioakes

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued an expanded travel alert for regions where travelers may be at risk of contracting Zika virus.

The mosquito-borne flavivirus may be associated with an increased risk of microcephaly and other intracranial and neurologic abnormalities in infants whose mothers were infected with Zika virus during pregnancy. Women who are pregnant or considering becoming pregnant should consider avoiding travel to countries included in the Zika virus alert.

The CDC’s expanded warning includes Barbados, Bolivia, Ecuador, Guadeloupe, Saint Martin, Guyana, Cape Verde, and Samoa. This is in addition to the previous travel alert for Puerto Rico (a U.S. territory), Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, and Venezuela.

In the United States, about a dozen cases of Zika virus have been reported, according to the CDC. States thus far where individuals have tested positive for the virus are Texas, Florida, Illinois, New Jersey, and Hawaii. These dozen cases include two pregnant women who tested positive for the Zika virus in Illinois this week. In Hawaii, a woman who had lived in Brazil while pregnant has given birth to a baby with microcephaly and congenital Zika virus infection. To date, all confirmed cases of Zika virus in the U.S. have been in individuals who traveled to areas with Zika virus transmission.

Zika virus, a member of the family of viruses that includes dengue fever, is spread by mosquitoes of the Aedes species, according to Dr. Amesh Adalja.

Dr. Adalja, a member of the public health committee of the Infectious Disease Society of America and an instructor in the department of infectious diseases at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, noted that though the virus has been known since the 1940s, “it was not considered a major public health threat” because of the generally mild course of the disease.

Infection is asymptomatic in 80% of individuals, he said. Symptoms of Zika virus infection, if they appear, include initial fever, a maculopapular rash, arthralgia, and sometimes conjunctivitis. There is no treatment for the disease and care is supportive.

A recent explosion of Zika virus cases in Brazil, however, has been associated with a large increase in cases of microcephaly in newborns. Though the association has not been confirmed, Zika virus has been found in infants born with microcephaly and in the placentas of mothers of babies with microcephaly.

The CDC has issued interim guidance for diagnosis, treatment, and management of suspected Zika virus in pregnant women. All pregnant women should be asked about travel to countries with known Zika virus exposure, with surveillance by fetal ultrasound and, in some cases, testing for Zika virus guided by symptoms and likelihood of exposure.

The CDC recommends vigilance against mosquito bites for pregnant women who do travel to areas with Zika virus activity, including the use of effective insect repellent, protective clothing, and remaining in and sleeping in air-conditioned rooms when possible.

In the United States, there is reason to be concerned about Zika virus, since “the scale of travel is very, very high” to the Central and South American and Caribbean countries where Zika virus transmission is active, Dr. Adalja said. However, since the same vector also transmits dengue fever and the Chikungunya virus – currently the focus of increasing concern in the U.S. – aggressive vector control measures are already underway in parts of the country where Aedes species mosquitoes are resident.

Though the consequences of the apparent association between maternal Zika virus infection and infant microcephaly are devastating, said Dr. Adalja, “it’s important that people put this in the proper public health perspective. Dengue fever kills thousands of people each year.”*

Dr. Adalja said that he expects commercially available testing for Zika virus to be developed; currently, testing is currently only available from the CDC and from some states’ departments of public health.

Additional resources for physicians

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories

CDC: www.cdc.gov/zika/

*Correction, 1/25/2016: An earlier version of this story misstated the number of deaths from dengue fever.

On Twitter @karioakes

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued an expanded travel alert for regions where travelers may be at risk of contracting Zika virus.

The mosquito-borne flavivirus may be associated with an increased risk of microcephaly and other intracranial and neurologic abnormalities in infants whose mothers were infected with Zika virus during pregnancy. Women who are pregnant or considering becoming pregnant should consider avoiding travel to countries included in the Zika virus alert.

The CDC’s expanded warning includes Barbados, Bolivia, Ecuador, Guadeloupe, Saint Martin, Guyana, Cape Verde, and Samoa. This is in addition to the previous travel alert for Puerto Rico (a U.S. territory), Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, and Venezuela.

In the United States, about a dozen cases of Zika virus have been reported, according to the CDC. States thus far where individuals have tested positive for the virus are Texas, Florida, Illinois, New Jersey, and Hawaii. These dozen cases include two pregnant women who tested positive for the Zika virus in Illinois this week. In Hawaii, a woman who had lived in Brazil while pregnant has given birth to a baby with microcephaly and congenital Zika virus infection. To date, all confirmed cases of Zika virus in the U.S. have been in individuals who traveled to areas with Zika virus transmission.

Zika virus, a member of the family of viruses that includes dengue fever, is spread by mosquitoes of the Aedes species, according to Dr. Amesh Adalja.

Dr. Adalja, a member of the public health committee of the Infectious Disease Society of America and an instructor in the department of infectious diseases at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, noted that though the virus has been known since the 1940s, “it was not considered a major public health threat” because of the generally mild course of the disease.

Infection is asymptomatic in 80% of individuals, he said. Symptoms of Zika virus infection, if they appear, include initial fever, a maculopapular rash, arthralgia, and sometimes conjunctivitis. There is no treatment for the disease and care is supportive.

A recent explosion of Zika virus cases in Brazil, however, has been associated with a large increase in cases of microcephaly in newborns. Though the association has not been confirmed, Zika virus has been found in infants born with microcephaly and in the placentas of mothers of babies with microcephaly.

The CDC has issued interim guidance for diagnosis, treatment, and management of suspected Zika virus in pregnant women. All pregnant women should be asked about travel to countries with known Zika virus exposure, with surveillance by fetal ultrasound and, in some cases, testing for Zika virus guided by symptoms and likelihood of exposure.

The CDC recommends vigilance against mosquito bites for pregnant women who do travel to areas with Zika virus activity, including the use of effective insect repellent, protective clothing, and remaining in and sleeping in air-conditioned rooms when possible.

In the United States, there is reason to be concerned about Zika virus, since “the scale of travel is very, very high” to the Central and South American and Caribbean countries where Zika virus transmission is active, Dr. Adalja said. However, since the same vector also transmits dengue fever and the Chikungunya virus – currently the focus of increasing concern in the U.S. – aggressive vector control measures are already underway in parts of the country where Aedes species mosquitoes are resident.

Though the consequences of the apparent association between maternal Zika virus infection and infant microcephaly are devastating, said Dr. Adalja, “it’s important that people put this in the proper public health perspective. Dengue fever kills thousands of people each year.”*

Dr. Adalja said that he expects commercially available testing for Zika virus to be developed; currently, testing is currently only available from the CDC and from some states’ departments of public health.

Additional resources for physicians

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories

CDC: www.cdc.gov/zika/

*Correction, 1/25/2016: An earlier version of this story misstated the number of deaths from dengue fever.

On Twitter @karioakes

CDC: Ask pregnant women about Zika virus exposure

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has released interim guidelines for the care of pregnant women during a Zika virus outbreak.

The guidelines, developed in consultation with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, come on the heels of a Jan. 15 advisory warning pregnant women to avoid traveling to tropical countries and territories with outbreaks of the mosquito-borne virus. The virus is typically associated with only mild symptoms, but has been linked with cases of microcephaly and other poor outcomes in pregnancy.

“Health care providers should ask all pregnant women about recent travel. Pregnant women with a history of travel to an area with Zika virus transmission who report two or more symptoms consistent with Zika virus disease (acute onset of fever, maculopapular rash, arthralgia, or conjunctivitis) during or within 2 weeks of travel, or who have ultrasound findings of fetal microcephaly or intracranial calcifications, should be tested for Zika virus infection in consultation with their state or local health department,” according to the guidelines, which were published Jan. 19 in an early release of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR. 2016 Jan 19;65[Early Release]:1-4).

Testing is not indicated for women who have not traveled to areas with Zika virus transmission, according to CDC.

For women who test positive for the virus, serial ultrasounds to monitor fetal growth and anatomy should be considered, as well as referral to a maternal-fetal medicine specialist or infectious disease specialist with expertise in pregnancy management, according to the guidelines.

While a positive reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) result on amniotic fluid would suggest intrauterine infection and could potentially be useful to pregnant women and their health care providers, it is currently not known how sensitive or specific the test is for congenital infection or whether a positive result is predictive of a subsequent fetal abnormality.

“Health care providers should discuss the risks and benefits of amniocentesis with their patients,” CDC officials wrote in the interim guidance.

The following tests are advised for live births with evidence of infection: histopathological examination of the placenta and umbilical cord, testing of frozen placental tissue and cord tissue for Zika virus RNA, and testing of cord serum for Zika and dengue virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies. Guidelines for infected infants are currently being developed.

No specific treatment exists for Zika virus infection; supportive care, including rest, fluids, use of analgesics and antipyretics, and acetaminophen for fever is advised.

The CDC continues to recommend that pregnant women avoid travel to areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing. Strict steps to avoid mosquito bites are advised for those who do travel to such areas. This includes use of protective clothing and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellents, as well as staying and sleeping in screened-in or air-conditioned rooms. Insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, and IR3535 are safe for pregnant women when used as directed on the label, according to the CDC.

Updates on areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission are available on the CDC website.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has released interim guidelines for the care of pregnant women during a Zika virus outbreak.

The guidelines, developed in consultation with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, come on the heels of a Jan. 15 advisory warning pregnant women to avoid traveling to tropical countries and territories with outbreaks of the mosquito-borne virus. The virus is typically associated with only mild symptoms, but has been linked with cases of microcephaly and other poor outcomes in pregnancy.

“Health care providers should ask all pregnant women about recent travel. Pregnant women with a history of travel to an area with Zika virus transmission who report two or more symptoms consistent with Zika virus disease (acute onset of fever, maculopapular rash, arthralgia, or conjunctivitis) during or within 2 weeks of travel, or who have ultrasound findings of fetal microcephaly or intracranial calcifications, should be tested for Zika virus infection in consultation with their state or local health department,” according to the guidelines, which were published Jan. 19 in an early release of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR. 2016 Jan 19;65[Early Release]:1-4).

Testing is not indicated for women who have not traveled to areas with Zika virus transmission, according to CDC.

For women who test positive for the virus, serial ultrasounds to monitor fetal growth and anatomy should be considered, as well as referral to a maternal-fetal medicine specialist or infectious disease specialist with expertise in pregnancy management, according to the guidelines.

While a positive reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) result on amniotic fluid would suggest intrauterine infection and could potentially be useful to pregnant women and their health care providers, it is currently not known how sensitive or specific the test is for congenital infection or whether a positive result is predictive of a subsequent fetal abnormality.

“Health care providers should discuss the risks and benefits of amniocentesis with their patients,” CDC officials wrote in the interim guidance.

The following tests are advised for live births with evidence of infection: histopathological examination of the placenta and umbilical cord, testing of frozen placental tissue and cord tissue for Zika virus RNA, and testing of cord serum for Zika and dengue virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies. Guidelines for infected infants are currently being developed.

No specific treatment exists for Zika virus infection; supportive care, including rest, fluids, use of analgesics and antipyretics, and acetaminophen for fever is advised.

The CDC continues to recommend that pregnant women avoid travel to areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing. Strict steps to avoid mosquito bites are advised for those who do travel to such areas. This includes use of protective clothing and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellents, as well as staying and sleeping in screened-in or air-conditioned rooms. Insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, and IR3535 are safe for pregnant women when used as directed on the label, according to the CDC.

Updates on areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission are available on the CDC website.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has released interim guidelines for the care of pregnant women during a Zika virus outbreak.

The guidelines, developed in consultation with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, come on the heels of a Jan. 15 advisory warning pregnant women to avoid traveling to tropical countries and territories with outbreaks of the mosquito-borne virus. The virus is typically associated with only mild symptoms, but has been linked with cases of microcephaly and other poor outcomes in pregnancy.

“Health care providers should ask all pregnant women about recent travel. Pregnant women with a history of travel to an area with Zika virus transmission who report two or more symptoms consistent with Zika virus disease (acute onset of fever, maculopapular rash, arthralgia, or conjunctivitis) during or within 2 weeks of travel, or who have ultrasound findings of fetal microcephaly or intracranial calcifications, should be tested for Zika virus infection in consultation with their state or local health department,” according to the guidelines, which were published Jan. 19 in an early release of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR. 2016 Jan 19;65[Early Release]:1-4).

Testing is not indicated for women who have not traveled to areas with Zika virus transmission, according to CDC.

For women who test positive for the virus, serial ultrasounds to monitor fetal growth and anatomy should be considered, as well as referral to a maternal-fetal medicine specialist or infectious disease specialist with expertise in pregnancy management, according to the guidelines.

While a positive reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) result on amniotic fluid would suggest intrauterine infection and could potentially be useful to pregnant women and their health care providers, it is currently not known how sensitive or specific the test is for congenital infection or whether a positive result is predictive of a subsequent fetal abnormality.

“Health care providers should discuss the risks and benefits of amniocentesis with their patients,” CDC officials wrote in the interim guidance.

The following tests are advised for live births with evidence of infection: histopathological examination of the placenta and umbilical cord, testing of frozen placental tissue and cord tissue for Zika virus RNA, and testing of cord serum for Zika and dengue virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies. Guidelines for infected infants are currently being developed.

No specific treatment exists for Zika virus infection; supportive care, including rest, fluids, use of analgesics and antipyretics, and acetaminophen for fever is advised.

The CDC continues to recommend that pregnant women avoid travel to areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing. Strict steps to avoid mosquito bites are advised for those who do travel to such areas. This includes use of protective clothing and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellents, as well as staying and sleeping in screened-in or air-conditioned rooms. Insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, and IR3535 are safe for pregnant women when used as directed on the label, according to the CDC.

Updates on areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission are available on the CDC website.

FROM MMWR

Zika virus: CDC warns pregnant women to avoid some tropical travel

Pregnant women and those planning to become pregnant should avoid traveling to 14 tropical countries and territories in Central and South America and the Caribbean, where there is a rapidly escalating outbreak of the mosquito-borne zika virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention in an advisory issued Jan. 15.

The CDC advisory covers Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, Venezuela, and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

Although illness due to the zika virus tends to be mild with symptoms lasting from several days to a week, research has indicated a correlation between the virus and a skyrocketing number of babies born with microcephaly and other poor outcomes in Brazil. The Brazilian Ministry of Health has declared a national health emergency (link in Portuguese) as officials there fear the numbers of cases will go higher.

“Until more is known, and out of an abundance of caution, CDC recommends special precautions for pregnant women and women trying to become pregnant,” the CDC said in a statement. Specifically, women at any trimester of pregnancy should cancel or postpone travel to the areas covered by the advisory. Any pregnant women who must travel should consult with a physician prior to travel and take great care to avoid mosquito bites. The advice should be observed by women who are thinking of becoming pregnant, according to the CDC.

The government of Canada has issued a similar travel warning for pregnant women.

CDC warns that because the mosquitoes of the Aedes aegypti species that spread zika virus are found worldwide, further outbreaks are likely in other countries. Indeed, zika virus transmission has been seen in several countries in Africa and Asia.

In December 2015, Puerto Rico reported its first confirmed zika virus case. Although zika has not been reported in the continental United States, the CDC reports there have been infected travelers returning from affected countries.

Advice for those who must travel to areas where zika virus transmission has been documented can be found on the CDC website.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Pregnant women and those planning to become pregnant should avoid traveling to 14 tropical countries and territories in Central and South America and the Caribbean, where there is a rapidly escalating outbreak of the mosquito-borne zika virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention in an advisory issued Jan. 15.

The CDC advisory covers Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, Venezuela, and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

Although illness due to the zika virus tends to be mild with symptoms lasting from several days to a week, research has indicated a correlation between the virus and a skyrocketing number of babies born with microcephaly and other poor outcomes in Brazil. The Brazilian Ministry of Health has declared a national health emergency (link in Portuguese) as officials there fear the numbers of cases will go higher.

“Until more is known, and out of an abundance of caution, CDC recommends special precautions for pregnant women and women trying to become pregnant,” the CDC said in a statement. Specifically, women at any trimester of pregnancy should cancel or postpone travel to the areas covered by the advisory. Any pregnant women who must travel should consult with a physician prior to travel and take great care to avoid mosquito bites. The advice should be observed by women who are thinking of becoming pregnant, according to the CDC.

The government of Canada has issued a similar travel warning for pregnant women.

CDC warns that because the mosquitoes of the Aedes aegypti species that spread zika virus are found worldwide, further outbreaks are likely in other countries. Indeed, zika virus transmission has been seen in several countries in Africa and Asia.

In December 2015, Puerto Rico reported its first confirmed zika virus case. Although zika has not been reported in the continental United States, the CDC reports there have been infected travelers returning from affected countries.

Advice for those who must travel to areas where zika virus transmission has been documented can be found on the CDC website.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Pregnant women and those planning to become pregnant should avoid traveling to 14 tropical countries and territories in Central and South America and the Caribbean, where there is a rapidly escalating outbreak of the mosquito-borne zika virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention in an advisory issued Jan. 15.

The CDC advisory covers Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, Venezuela, and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

Although illness due to the zika virus tends to be mild with symptoms lasting from several days to a week, research has indicated a correlation between the virus and a skyrocketing number of babies born with microcephaly and other poor outcomes in Brazil. The Brazilian Ministry of Health has declared a national health emergency (link in Portuguese) as officials there fear the numbers of cases will go higher.

“Until more is known, and out of an abundance of caution, CDC recommends special precautions for pregnant women and women trying to become pregnant,” the CDC said in a statement. Specifically, women at any trimester of pregnancy should cancel or postpone travel to the areas covered by the advisory. Any pregnant women who must travel should consult with a physician prior to travel and take great care to avoid mosquito bites. The advice should be observed by women who are thinking of becoming pregnant, according to the CDC.

The government of Canada has issued a similar travel warning for pregnant women.

CDC warns that because the mosquitoes of the Aedes aegypti species that spread zika virus are found worldwide, further outbreaks are likely in other countries. Indeed, zika virus transmission has been seen in several countries in Africa and Asia.

In December 2015, Puerto Rico reported its first confirmed zika virus case. Although zika has not been reported in the continental United States, the CDC reports there have been infected travelers returning from affected countries.

Advice for those who must travel to areas where zika virus transmission has been documented can be found on the CDC website.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

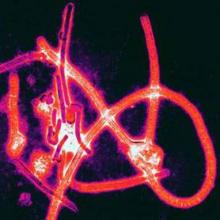

West African Ebola–virus transmission ends, then resumes

A day after the World Health Organization declared on Jan. 14 that no known cases of Ebola-virus transmission or active infection had been identified in West Africa for more than 42 days, the agency revealed the existence of a new, single case of Ebola-virus infection in Sierra Leone.

The appearance of the new case highlighted the challenges that remain in fully stamping out the West African Ebola–virus outbreak. The crisis began in December 2013, raged throughout 2014, and only wound down toward a sputtering halt near the end of 2015.

When Dr. Rick Brennan, the World Health Organization (WHO) director for Emergency Risk Management and Humanitarian Response, announced during a press conference on Jan. 14, “the end of Ebola-virus transmission in West Africa” and “the first time since 2014 that all know chains of transmission have stopped in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone,” he and his colleague, Dr. Peter Graaff, also underscored the ongoing risk for sporadic, isolated cases. The main threat for new cases comes from men who survived Ebola-virus infection but harbored significant quantities of infectious virus in various body fluids and tissues, including their semen, for a period of about 1 year following their infection.

During the press conference, both Dr. Brennan and Dr. Graaff spoke of a new, strengthened infrastructure that WHO had placed in West Africa to better monitor and react quickly to these flare-up cases – the mechanism that led to quick identification of the new Sierra Leone case.

“I think you’ll see a more responsive and effective WHO,” said Dr. Graaff, WHO’s director of Ebola response. “We will use the Ebola experience to be more agile, more operational, and better able to react more quickly to whatever future problems come our way,” including infectious-disease outbreaks by pathogens other than Ebola virus.

The 42-day period without new infections that had led to the announcement of an end to Ebola-virus transmission in West Africa represents two 21-day incubation cycles for the virus. Until the Sierra Leone case reported on Jan. 15, the last confirmed West African case had been identified in Liberia in mid-November. Liberia had previously been declared Ebola free in last May, but four new, isolated infections appeared subsequent to that transmitted by Ebola-infection survivors who still harbored infectious virus. Before the Jan. 15 case, an additional three such flare-ups occurred in Sierra Leone and another three in Guinea since last March, Dr. Brennan said.

The current tally on the West African Ebola outbreak stands at roughly 28,500 confirmed cases identified, and about 11,300 deaths. Nearly three-quarters of infections occurred during 2014. The case fatality rate at the start of the outbreak ran about 80%, noted Dr. Graaff, but gradually fell as infected patients began receiving better care. Near the outbreak’s end, the case fatality rate stood at roughly 35%, when most patients were receiving optimal clinical care.

WHO staffers are maintaining close surveillance of people who recently survived Ebola-virus infection so that they can identify and isolate any new infections. WHO personnel have also counseled these survivors on the risk they pose for potential transmission, primarily by unprotected sex by men for up to 12 months following the end of active infection. The WHO also plans to launch an investigational protocol to vaccinate sexual partners and other close contacts of adult male survivors with an as-yet unapproved Ebola vaccine to further reduce risk of new infections.

“The WHO and world community reacted slowly at the start of the Ebola outbreak” in early 2014, admitted Dr. Brennan. “Without question, the disease got away from us. In retrospect, there were a number of things that we should have done better and sooner,” he said. “We have done a lot of soul-searching and we [at WHO] have identified a number of weaknesses in our structures and systems. We have already taken several important steps, and we are undergoing major reforms of our emergency operations. I think you’ll see a much more effective WHO in the future.”

Reform of WHO systems for infection prevention and control “will be much better able to detect new cases, not only of Ebola, but of other important diseases,” said Dr. Graaff.

The United States is also strengthening its health screening and monitoring system for travelers coming from affected countries and improving its hospital preparedness to manage cases, said Alice C. Hill, senior adviser for preparedness and resilience at the National Security Council and special assistant to President Obama. Hill, who spoke Jan. 6 at the Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise stakeholders workshop, acknowledged that challenges still exist that must be addressed, including the development of safe and effective diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines for existing infectious diseases such as influenza and more emerging threats such as Ebola or MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), developing accurate disease forecasting capabilities to predict what will be the next threat, building rapid clinical trial networks and manufacturing capabilities, and the abilities for mass dispensing of medical countermeasures.

Gregory Twachtman also contributed to this story.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

A day after the World Health Organization declared on Jan. 14 that no known cases of Ebola-virus transmission or active infection had been identified in West Africa for more than 42 days, the agency revealed the existence of a new, single case of Ebola-virus infection in Sierra Leone.

The appearance of the new case highlighted the challenges that remain in fully stamping out the West African Ebola–virus outbreak. The crisis began in December 2013, raged throughout 2014, and only wound down toward a sputtering halt near the end of 2015.

When Dr. Rick Brennan, the World Health Organization (WHO) director for Emergency Risk Management and Humanitarian Response, announced during a press conference on Jan. 14, “the end of Ebola-virus transmission in West Africa” and “the first time since 2014 that all know chains of transmission have stopped in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone,” he and his colleague, Dr. Peter Graaff, also underscored the ongoing risk for sporadic, isolated cases. The main threat for new cases comes from men who survived Ebola-virus infection but harbored significant quantities of infectious virus in various body fluids and tissues, including their semen, for a period of about 1 year following their infection.

During the press conference, both Dr. Brennan and Dr. Graaff spoke of a new, strengthened infrastructure that WHO had placed in West Africa to better monitor and react quickly to these flare-up cases – the mechanism that led to quick identification of the new Sierra Leone case.

“I think you’ll see a more responsive and effective WHO,” said Dr. Graaff, WHO’s director of Ebola response. “We will use the Ebola experience to be more agile, more operational, and better able to react more quickly to whatever future problems come our way,” including infectious-disease outbreaks by pathogens other than Ebola virus.

The 42-day period without new infections that had led to the announcement of an end to Ebola-virus transmission in West Africa represents two 21-day incubation cycles for the virus. Until the Sierra Leone case reported on Jan. 15, the last confirmed West African case had been identified in Liberia in mid-November. Liberia had previously been declared Ebola free in last May, but four new, isolated infections appeared subsequent to that transmitted by Ebola-infection survivors who still harbored infectious virus. Before the Jan. 15 case, an additional three such flare-ups occurred in Sierra Leone and another three in Guinea since last March, Dr. Brennan said.

The current tally on the West African Ebola outbreak stands at roughly 28,500 confirmed cases identified, and about 11,300 deaths. Nearly three-quarters of infections occurred during 2014. The case fatality rate at the start of the outbreak ran about 80%, noted Dr. Graaff, but gradually fell as infected patients began receiving better care. Near the outbreak’s end, the case fatality rate stood at roughly 35%, when most patients were receiving optimal clinical care.

WHO staffers are maintaining close surveillance of people who recently survived Ebola-virus infection so that they can identify and isolate any new infections. WHO personnel have also counseled these survivors on the risk they pose for potential transmission, primarily by unprotected sex by men for up to 12 months following the end of active infection. The WHO also plans to launch an investigational protocol to vaccinate sexual partners and other close contacts of adult male survivors with an as-yet unapproved Ebola vaccine to further reduce risk of new infections.

“The WHO and world community reacted slowly at the start of the Ebola outbreak” in early 2014, admitted Dr. Brennan. “Without question, the disease got away from us. In retrospect, there were a number of things that we should have done better and sooner,” he said. “We have done a lot of soul-searching and we [at WHO] have identified a number of weaknesses in our structures and systems. We have already taken several important steps, and we are undergoing major reforms of our emergency operations. I think you’ll see a much more effective WHO in the future.”

Reform of WHO systems for infection prevention and control “will be much better able to detect new cases, not only of Ebola, but of other important diseases,” said Dr. Graaff.

The United States is also strengthening its health screening and monitoring system for travelers coming from affected countries and improving its hospital preparedness to manage cases, said Alice C. Hill, senior adviser for preparedness and resilience at the National Security Council and special assistant to President Obama. Hill, who spoke Jan. 6 at the Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise stakeholders workshop, acknowledged that challenges still exist that must be addressed, including the development of safe and effective diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines for existing infectious diseases such as influenza and more emerging threats such as Ebola or MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), developing accurate disease forecasting capabilities to predict what will be the next threat, building rapid clinical trial networks and manufacturing capabilities, and the abilities for mass dispensing of medical countermeasures.

Gregory Twachtman also contributed to this story.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

A day after the World Health Organization declared on Jan. 14 that no known cases of Ebola-virus transmission or active infection had been identified in West Africa for more than 42 days, the agency revealed the existence of a new, single case of Ebola-virus infection in Sierra Leone.

The appearance of the new case highlighted the challenges that remain in fully stamping out the West African Ebola–virus outbreak. The crisis began in December 2013, raged throughout 2014, and only wound down toward a sputtering halt near the end of 2015.

When Dr. Rick Brennan, the World Health Organization (WHO) director for Emergency Risk Management and Humanitarian Response, announced during a press conference on Jan. 14, “the end of Ebola-virus transmission in West Africa” and “the first time since 2014 that all know chains of transmission have stopped in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone,” he and his colleague, Dr. Peter Graaff, also underscored the ongoing risk for sporadic, isolated cases. The main threat for new cases comes from men who survived Ebola-virus infection but harbored significant quantities of infectious virus in various body fluids and tissues, including their semen, for a period of about 1 year following their infection.

During the press conference, both Dr. Brennan and Dr. Graaff spoke of a new, strengthened infrastructure that WHO had placed in West Africa to better monitor and react quickly to these flare-up cases – the mechanism that led to quick identification of the new Sierra Leone case.

“I think you’ll see a more responsive and effective WHO,” said Dr. Graaff, WHO’s director of Ebola response. “We will use the Ebola experience to be more agile, more operational, and better able to react more quickly to whatever future problems come our way,” including infectious-disease outbreaks by pathogens other than Ebola virus.

The 42-day period without new infections that had led to the announcement of an end to Ebola-virus transmission in West Africa represents two 21-day incubation cycles for the virus. Until the Sierra Leone case reported on Jan. 15, the last confirmed West African case had been identified in Liberia in mid-November. Liberia had previously been declared Ebola free in last May, but four new, isolated infections appeared subsequent to that transmitted by Ebola-infection survivors who still harbored infectious virus. Before the Jan. 15 case, an additional three such flare-ups occurred in Sierra Leone and another three in Guinea since last March, Dr. Brennan said.

The current tally on the West African Ebola outbreak stands at roughly 28,500 confirmed cases identified, and about 11,300 deaths. Nearly three-quarters of infections occurred during 2014. The case fatality rate at the start of the outbreak ran about 80%, noted Dr. Graaff, but gradually fell as infected patients began receiving better care. Near the outbreak’s end, the case fatality rate stood at roughly 35%, when most patients were receiving optimal clinical care.

WHO staffers are maintaining close surveillance of people who recently survived Ebola-virus infection so that they can identify and isolate any new infections. WHO personnel have also counseled these survivors on the risk they pose for potential transmission, primarily by unprotected sex by men for up to 12 months following the end of active infection. The WHO also plans to launch an investigational protocol to vaccinate sexual partners and other close contacts of adult male survivors with an as-yet unapproved Ebola vaccine to further reduce risk of new infections.

“The WHO and world community reacted slowly at the start of the Ebola outbreak” in early 2014, admitted Dr. Brennan. “Without question, the disease got away from us. In retrospect, there were a number of things that we should have done better and sooner,” he said. “We have done a lot of soul-searching and we [at WHO] have identified a number of weaknesses in our structures and systems. We have already taken several important steps, and we are undergoing major reforms of our emergency operations. I think you’ll see a much more effective WHO in the future.”

Reform of WHO systems for infection prevention and control “will be much better able to detect new cases, not only of Ebola, but of other important diseases,” said Dr. Graaff.

The United States is also strengthening its health screening and monitoring system for travelers coming from affected countries and improving its hospital preparedness to manage cases, said Alice C. Hill, senior adviser for preparedness and resilience at the National Security Council and special assistant to President Obama. Hill, who spoke Jan. 6 at the Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise stakeholders workshop, acknowledged that challenges still exist that must be addressed, including the development of safe and effective diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines for existing infectious diseases such as influenza and more emerging threats such as Ebola or MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), developing accurate disease forecasting capabilities to predict what will be the next threat, building rapid clinical trial networks and manufacturing capabilities, and the abilities for mass dispensing of medical countermeasures.

Gregory Twachtman also contributed to this story.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Pertussis vaccine possibly ineffective in preschoolers

Preschool-age children who have been fully vaccinated against pertussis can still develop symptoms of illness consistent with a whooping cough diagnosis, according to a study of toddlers in a Tallahassee, Fla., school that experienced an outbreak of pertussis in late 2013 (Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Feb;22[2]. doi: 10.3201/eid2202.150325)

The study, published in Emerging Infectious Diseases by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is the result of an outbreak investigation at the preschool that began after a 1-year-old and two 3-year-old children developed illness consistent with pertussis, and were confirmed to have pertussis after undergoing a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test.

The Florida Department of Health administered a questionnaire to be completed by families of the 117 students (ages 10 months to 6 years) and 26 staff members. Questionnaire completion rate was 98%, with three student households and one staff household failing to complete it.

Overall, 28 cases were determined to be “probable” pertussis and 11 were confirmed as pertussis via PCR or other laboratory testing methods. Of these, 26 were students aged 1-5 years (22% of total student population), 2 were attributed to the staff (7%), and 11 were linked to the preschool, of which 9 originated from the households of the individual students and 2 from “camp counselors who had contact with a sibling of a laboratory-confirmed case-patient who attended the preschool.”

However, 28 of the students who had pertussis had received at least three vaccinations, with 23 of them having received at least four vaccinations, meaning they were classified as being fully vaccinated against the disease. Only 5 out of the school’s 117 children had not received the complete series of vaccinations, out of which 2 ended up being case-patients; both of those children, however, had received at least one vaccination prior to falling sick.

“Poor performance of a vaccine in a defined cohort might suggest a provider-level failure to store, use, and administer the vaccine properly,” noted the researchers, led by Dr. James Matthias of the Florida Department of Health. “Although we did not assess vaccine storage and handling practices, children from this investigation were seen by multiple providers in the community [and] no general increase in reported pertussis incidence was observed in the county at the same time as this outbreak.”

The bottom line, the authors concluded, is for pediatricians and primary care doctors to be wary that vaccination against pertussis doesn’t necessarily mean patients can’t ever get it. If pertussis symptoms arise in a vaccinated child, especially one 5 years old or younger, it may still be whooping cough.

The CDC supported the study. Dr. Matthias and his coauthors are all affiliated with the Florida Department of Health and the CDC, but reported no other relevant financial disclosures.

Preschool-age children who have been fully vaccinated against pertussis can still develop symptoms of illness consistent with a whooping cough diagnosis, according to a study of toddlers in a Tallahassee, Fla., school that experienced an outbreak of pertussis in late 2013 (Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Feb;22[2]. doi: 10.3201/eid2202.150325)

The study, published in Emerging Infectious Diseases by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is the result of an outbreak investigation at the preschool that began after a 1-year-old and two 3-year-old children developed illness consistent with pertussis, and were confirmed to have pertussis after undergoing a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test.

The Florida Department of Health administered a questionnaire to be completed by families of the 117 students (ages 10 months to 6 years) and 26 staff members. Questionnaire completion rate was 98%, with three student households and one staff household failing to complete it.

Overall, 28 cases were determined to be “probable” pertussis and 11 were confirmed as pertussis via PCR or other laboratory testing methods. Of these, 26 were students aged 1-5 years (22% of total student population), 2 were attributed to the staff (7%), and 11 were linked to the preschool, of which 9 originated from the households of the individual students and 2 from “camp counselors who had contact with a sibling of a laboratory-confirmed case-patient who attended the preschool.”

However, 28 of the students who had pertussis had received at least three vaccinations, with 23 of them having received at least four vaccinations, meaning they were classified as being fully vaccinated against the disease. Only 5 out of the school’s 117 children had not received the complete series of vaccinations, out of which 2 ended up being case-patients; both of those children, however, had received at least one vaccination prior to falling sick.

“Poor performance of a vaccine in a defined cohort might suggest a provider-level failure to store, use, and administer the vaccine properly,” noted the researchers, led by Dr. James Matthias of the Florida Department of Health. “Although we did not assess vaccine storage and handling practices, children from this investigation were seen by multiple providers in the community [and] no general increase in reported pertussis incidence was observed in the county at the same time as this outbreak.”

The bottom line, the authors concluded, is for pediatricians and primary care doctors to be wary that vaccination against pertussis doesn’t necessarily mean patients can’t ever get it. If pertussis symptoms arise in a vaccinated child, especially one 5 years old or younger, it may still be whooping cough.

The CDC supported the study. Dr. Matthias and his coauthors are all affiliated with the Florida Department of Health and the CDC, but reported no other relevant financial disclosures.

Preschool-age children who have been fully vaccinated against pertussis can still develop symptoms of illness consistent with a whooping cough diagnosis, according to a study of toddlers in a Tallahassee, Fla., school that experienced an outbreak of pertussis in late 2013 (Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Feb;22[2]. doi: 10.3201/eid2202.150325)

The study, published in Emerging Infectious Diseases by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is the result of an outbreak investigation at the preschool that began after a 1-year-old and two 3-year-old children developed illness consistent with pertussis, and were confirmed to have pertussis after undergoing a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test.

The Florida Department of Health administered a questionnaire to be completed by families of the 117 students (ages 10 months to 6 years) and 26 staff members. Questionnaire completion rate was 98%, with three student households and one staff household failing to complete it.

Overall, 28 cases were determined to be “probable” pertussis and 11 were confirmed as pertussis via PCR or other laboratory testing methods. Of these, 26 were students aged 1-5 years (22% of total student population), 2 were attributed to the staff (7%), and 11 were linked to the preschool, of which 9 originated from the households of the individual students and 2 from “camp counselors who had contact with a sibling of a laboratory-confirmed case-patient who attended the preschool.”

However, 28 of the students who had pertussis had received at least three vaccinations, with 23 of them having received at least four vaccinations, meaning they were classified as being fully vaccinated against the disease. Only 5 out of the school’s 117 children had not received the complete series of vaccinations, out of which 2 ended up being case-patients; both of those children, however, had received at least one vaccination prior to falling sick.

“Poor performance of a vaccine in a defined cohort might suggest a provider-level failure to store, use, and administer the vaccine properly,” noted the researchers, led by Dr. James Matthias of the Florida Department of Health. “Although we did not assess vaccine storage and handling practices, children from this investigation were seen by multiple providers in the community [and] no general increase in reported pertussis incidence was observed in the county at the same time as this outbreak.”

The bottom line, the authors concluded, is for pediatricians and primary care doctors to be wary that vaccination against pertussis doesn’t necessarily mean patients can’t ever get it. If pertussis symptoms arise in a vaccinated child, especially one 5 years old or younger, it may still be whooping cough.

The CDC supported the study. Dr. Matthias and his coauthors are all affiliated with the Florida Department of Health and the CDC, but reported no other relevant financial disclosures.

FROM EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Preschoolers vaccinated against pertussis may still develop whooping cough or similar symptoms.

Major finding: Children who had received full series of pertussis vaccinations still developed whooping cough during an outbreak at a school of 117 children.

Data source: Survey of 117 students and 26 staff members at a Tallahassee, Fla., school in 2014.

Disclosures: The CDC supported the study. Dr. Matthias and his coauthors are all affiliated with the Florida Department of Health and the CDC, but reported no other relevant financial disclosures.

Novel treatments assessed in midst of Ebola crisis

Separate groups of researchers supported by nonprofit and government agencies have assessed two novel Ebola virus disease treatments in the midst of the recent outbreak in West Africa.

The first study was a “natural experiment” that occurred when one Liberian treatment center temporarily ran out of first-line antimalarial drugs. This allowed investigators to discover that a second-line regimen may actually be more effective in reducing mortality from Ebola infection. (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 7;374:23-32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504605).

The lack of effective therapies against the Ebola virus spurred the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to identify several potential candidate treatments among compounds that are already used to treat other diseases, including malaria. However, there is little or no evidence to date concerning the real-world efficacy of these agents that have shown in-vitro activity against Ebola, said Etienne Gignoux of Epicentre, an epidemiologic research group headquartered in Paris, and of Médecins sans Frontières in Paris and Geneva, and his associates.

At the treatment center in Foya, Liberia, infected patients were routinely prescribed prophylactic antibiotics and a 3-day course of the antimalarial combination therapy artemether-lumefantrine, along with supportive treatment such as intravenous fluids. A 2-week shortage of this first-line antimalarial occurred during a sudden surge in admissions, and patients were instead prescribed artesunate-amodiaquine. Mr. Gignoux and his associates assessed outcomes in 194 patients prescribed artemether-lumefantrine, 71 prescribed artesunate-amodiaquine, 63 prescribed no antimalarials, and 53 for whom prescription data were missing.

They found that mortality risk was 31% lower with artesunate-amodiaquine than with the first-line antimalarials (risk ratio, 0.69). This mortality benefit persisted across several subgroups of patients, as well as in an analysis that specifically adjusted for the effects of potential confounding factors.

The results suggest that artesunate-amodiaquine may be preferable for the treatment of Ebola infection, but more research is needed to confirm this and to establish the safest, most effective therapeutic dose in these patients, the investigators said.They noted that their study had several limitations. The patient records included only prescribing information, so it was impossible to assess whether patients completed the full course of treatment. And all the antimalarials were oral formulations, so severely ill patients may not have been able to swallow or to keep down all doses.

In addition, artesunate-amodiaquine is known to cause more gastrointestinal adverse effects than the other antimalarials, so it’s possible that patients in that group were less likely to complete the full course of treatment. And many patients were concomitantly given the antiemetic metoclopramide, but data on possible adverse effects of this drug or possible drug interactions were not recorded.

The Liberian study was largely supported by Médecins sans Frontières, and the researchers reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Efficacy of convalescent plasma

In the second study, researchers at an Ebola treatment center in Guinea examined whether transfusion of convalescent plasma – plasma derived from patients who recovered from Ebola infection, which presumably carries helpful antibodies to the virus – was safe and effective. Their 6-month nonrandomized study involved 84 patients given two consecutive transfusions of 200-250 mL ABO-compatible plasma plus routine supportive care and 418 historical control subjects who had been treated before the plasma transfusions became available (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 7;374:33-42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa15118212).

The primary outcome – the risk of death during the 3-16 days after diagnosis – was 31% in the intervention group and 38% in the control group, a nonsignificant difference. This indicates that convalescent plasma transfusions do not exert a marked survival effect, at least at this dosage, said Dr. Johan van Griensven of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp (Belgium), and his associates.

There were no serious adverse effects from the transfusions, and the procedure was acceptable to donors, patients, and caregivers.

The main limitation of this study was that actual levels of neutralizing antibodies in the transfused plasma could not be assessed. Such assays require biosafety level-4 laboratories, which are not available in the affected countries. “It is possible that high-titer convalescent plasma or hyperimmune globulin might be more potent” than the plasma used in this study, or that more frequent administration and higher total volumes could be more effective, Dr. van Griensven and his associates said.

They added that they “cannot exclude the possibility that some patients will benefit more than others from treatment with convalescent plasma.” For example, children younger than 5 years are known to be at high risk of death from the Ebola virus and had the highest risk of death in this study’s control group. However, four of the five patients in this age group who received convalescent plasma survived. Similarly, pregnant women infected with Ebola virus also are at high risk of death, but six of the eight in this study who received convalescent plasma survived.

The Guinea study was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, the Flemish Department of Economy, Science, and Innovation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research’s Unit on Emerging and Zoonotic Infections at the University of Liverpool, the Medical Research Council, and the Department for International Development. Dr. van Griensven and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Separate groups of researchers supported by nonprofit and government agencies have assessed two novel Ebola virus disease treatments in the midst of the recent outbreak in West Africa.

The first study was a “natural experiment” that occurred when one Liberian treatment center temporarily ran out of first-line antimalarial drugs. This allowed investigators to discover that a second-line regimen may actually be more effective in reducing mortality from Ebola infection. (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 7;374:23-32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504605).

The lack of effective therapies against the Ebola virus spurred the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to identify several potential candidate treatments among compounds that are already used to treat other diseases, including malaria. However, there is little or no evidence to date concerning the real-world efficacy of these agents that have shown in-vitro activity against Ebola, said Etienne Gignoux of Epicentre, an epidemiologic research group headquartered in Paris, and of Médecins sans Frontières in Paris and Geneva, and his associates.

At the treatment center in Foya, Liberia, infected patients were routinely prescribed prophylactic antibiotics and a 3-day course of the antimalarial combination therapy artemether-lumefantrine, along with supportive treatment such as intravenous fluids. A 2-week shortage of this first-line antimalarial occurred during a sudden surge in admissions, and patients were instead prescribed artesunate-amodiaquine. Mr. Gignoux and his associates assessed outcomes in 194 patients prescribed artemether-lumefantrine, 71 prescribed artesunate-amodiaquine, 63 prescribed no antimalarials, and 53 for whom prescription data were missing.

They found that mortality risk was 31% lower with artesunate-amodiaquine than with the first-line antimalarials (risk ratio, 0.69). This mortality benefit persisted across several subgroups of patients, as well as in an analysis that specifically adjusted for the effects of potential confounding factors.

The results suggest that artesunate-amodiaquine may be preferable for the treatment of Ebola infection, but more research is needed to confirm this and to establish the safest, most effective therapeutic dose in these patients, the investigators said.They noted that their study had several limitations. The patient records included only prescribing information, so it was impossible to assess whether patients completed the full course of treatment. And all the antimalarials were oral formulations, so severely ill patients may not have been able to swallow or to keep down all doses.

In addition, artesunate-amodiaquine is known to cause more gastrointestinal adverse effects than the other antimalarials, so it’s possible that patients in that group were less likely to complete the full course of treatment. And many patients were concomitantly given the antiemetic metoclopramide, but data on possible adverse effects of this drug or possible drug interactions were not recorded.

The Liberian study was largely supported by Médecins sans Frontières, and the researchers reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Efficacy of convalescent plasma

In the second study, researchers at an Ebola treatment center in Guinea examined whether transfusion of convalescent plasma – plasma derived from patients who recovered from Ebola infection, which presumably carries helpful antibodies to the virus – was safe and effective. Their 6-month nonrandomized study involved 84 patients given two consecutive transfusions of 200-250 mL ABO-compatible plasma plus routine supportive care and 418 historical control subjects who had been treated before the plasma transfusions became available (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 7;374:33-42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa15118212).

The primary outcome – the risk of death during the 3-16 days after diagnosis – was 31% in the intervention group and 38% in the control group, a nonsignificant difference. This indicates that convalescent plasma transfusions do not exert a marked survival effect, at least at this dosage, said Dr. Johan van Griensven of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp (Belgium), and his associates.

There were no serious adverse effects from the transfusions, and the procedure was acceptable to donors, patients, and caregivers.

The main limitation of this study was that actual levels of neutralizing antibodies in the transfused plasma could not be assessed. Such assays require biosafety level-4 laboratories, which are not available in the affected countries. “It is possible that high-titer convalescent plasma or hyperimmune globulin might be more potent” than the plasma used in this study, or that more frequent administration and higher total volumes could be more effective, Dr. van Griensven and his associates said.

They added that they “cannot exclude the possibility that some patients will benefit more than others from treatment with convalescent plasma.” For example, children younger than 5 years are known to be at high risk of death from the Ebola virus and had the highest risk of death in this study’s control group. However, four of the five patients in this age group who received convalescent plasma survived. Similarly, pregnant women infected with Ebola virus also are at high risk of death, but six of the eight in this study who received convalescent plasma survived.

The Guinea study was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, the Flemish Department of Economy, Science, and Innovation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research’s Unit on Emerging and Zoonotic Infections at the University of Liverpool, the Medical Research Council, and the Department for International Development. Dr. van Griensven and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Separate groups of researchers supported by nonprofit and government agencies have assessed two novel Ebola virus disease treatments in the midst of the recent outbreak in West Africa.

The first study was a “natural experiment” that occurred when one Liberian treatment center temporarily ran out of first-line antimalarial drugs. This allowed investigators to discover that a second-line regimen may actually be more effective in reducing mortality from Ebola infection. (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 7;374:23-32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504605).

The lack of effective therapies against the Ebola virus spurred the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to identify several potential candidate treatments among compounds that are already used to treat other diseases, including malaria. However, there is little or no evidence to date concerning the real-world efficacy of these agents that have shown in-vitro activity against Ebola, said Etienne Gignoux of Epicentre, an epidemiologic research group headquartered in Paris, and of Médecins sans Frontières in Paris and Geneva, and his associates.

At the treatment center in Foya, Liberia, infected patients were routinely prescribed prophylactic antibiotics and a 3-day course of the antimalarial combination therapy artemether-lumefantrine, along with supportive treatment such as intravenous fluids. A 2-week shortage of this first-line antimalarial occurred during a sudden surge in admissions, and patients were instead prescribed artesunate-amodiaquine. Mr. Gignoux and his associates assessed outcomes in 194 patients prescribed artemether-lumefantrine, 71 prescribed artesunate-amodiaquine, 63 prescribed no antimalarials, and 53 for whom prescription data were missing.

They found that mortality risk was 31% lower with artesunate-amodiaquine than with the first-line antimalarials (risk ratio, 0.69). This mortality benefit persisted across several subgroups of patients, as well as in an analysis that specifically adjusted for the effects of potential confounding factors.

The results suggest that artesunate-amodiaquine may be preferable for the treatment of Ebola infection, but more research is needed to confirm this and to establish the safest, most effective therapeutic dose in these patients, the investigators said.They noted that their study had several limitations. The patient records included only prescribing information, so it was impossible to assess whether patients completed the full course of treatment. And all the antimalarials were oral formulations, so severely ill patients may not have been able to swallow or to keep down all doses.

In addition, artesunate-amodiaquine is known to cause more gastrointestinal adverse effects than the other antimalarials, so it’s possible that patients in that group were less likely to complete the full course of treatment. And many patients were concomitantly given the antiemetic metoclopramide, but data on possible adverse effects of this drug or possible drug interactions were not recorded.

The Liberian study was largely supported by Médecins sans Frontières, and the researchers reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Efficacy of convalescent plasma

In the second study, researchers at an Ebola treatment center in Guinea examined whether transfusion of convalescent plasma – plasma derived from patients who recovered from Ebola infection, which presumably carries helpful antibodies to the virus – was safe and effective. Their 6-month nonrandomized study involved 84 patients given two consecutive transfusions of 200-250 mL ABO-compatible plasma plus routine supportive care and 418 historical control subjects who had been treated before the plasma transfusions became available (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 7;374:33-42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa15118212).

The primary outcome – the risk of death during the 3-16 days after diagnosis – was 31% in the intervention group and 38% in the control group, a nonsignificant difference. This indicates that convalescent plasma transfusions do not exert a marked survival effect, at least at this dosage, said Dr. Johan van Griensven of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp (Belgium), and his associates.

There were no serious adverse effects from the transfusions, and the procedure was acceptable to donors, patients, and caregivers.

The main limitation of this study was that actual levels of neutralizing antibodies in the transfused plasma could not be assessed. Such assays require biosafety level-4 laboratories, which are not available in the affected countries. “It is possible that high-titer convalescent plasma or hyperimmune globulin might be more potent” than the plasma used in this study, or that more frequent administration and higher total volumes could be more effective, Dr. van Griensven and his associates said.

They added that they “cannot exclude the possibility that some patients will benefit more than others from treatment with convalescent plasma.” For example, children younger than 5 years are known to be at high risk of death from the Ebola virus and had the highest risk of death in this study’s control group. However, four of the five patients in this age group who received convalescent plasma survived. Similarly, pregnant women infected with Ebola virus also are at high risk of death, but six of the eight in this study who received convalescent plasma survived.

The Guinea study was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, the Flemish Department of Economy, Science, and Innovation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research’s Unit on Emerging and Zoonotic Infections at the University of Liverpool, the Medical Research Council, and the Department for International Development. Dr. van Griensven and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Researchers were able to examine novel treatments in the midst of the recent Ebola crisis in West Africa.

Major finding: Mortality risk was 31% lower with artesunate-amodiaquine than with first-line antimalarials, suggesting that artesunate-amodiaquine may be preferable for the treatment of Ebola infection. Two consecutive transfusions of 200-250 mL ABO-compatible convalescent plasma do not exert a marked survival effect for Ebola virus disease patients.

Data source: A “natural experiment” comparing two different antimalarial regimens in 382 patients in Liberia, and a nonrandomized comparative study of plasma transfusions in 99 patients in Guinea.

Disclosures: The Liberian study was largely supported by Médecins sans Frontières; the Guinea study was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, the Flemish Department of Economy, Science, and Innovation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research’s Unit on Emerging and Zoonotic Infections at the University of Liverpool, the Medical Research Council, and the Department for International Development. Mr. Gignoux, Dr. van Griensven, and their associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Men seen as main source of TB transmission

More than half of tuberculosis infections among men, women, and children were seen to derive from contacts with adult men, according to findings from research teams working in the United Kingdom, Zambia, and South Africa.

Understanding TB infection incidence by age and sex of source cases, and where and how often contacts occur, is critical to controlling transmission and directing prevention and treatment efforts. For this study, published online in the American Journal of Epidemiology (Am J Epidemiol. 2015 Dec 8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv160), researchers compared TB prevalence data in adults from a recent study in South Africa and Zambia and from an earlier, related study in children with data on daily contact patterns gathered through interviews with more than 3,500 adults 18 and older (53% female).

Close contacts were defined as face-to-face conversations, while casual contacts were defined as sharing indoor space, a potentially important source of TB transmission. In the interviews, adults reported an average of 4.9 close contacts and 10.4 casual contacts daily. They also reported the age groups and sexes with which their contacts occurred.

The authors of the study, led by Dr. Peter J. Dodd of the University of Sheffield (U.K.), said the finding on adult males as the likely drivers of TB transmission in both genders was surprising, because the study also revealed that daily close contacts occurred preferentially among age groups and among members of the same sex.

More than 63% of women’s close contacts and 61% of men’s were among members of the same sex. Adults averaged 0.8 close contacts per day with children under 12, though women had a slightly higher rate of contact than men. Among adults, estimated infections from contact with adult men was 57.3% in South Africa and 65.7% in Zambia. Estimated transmission from contact with men was 50% or higher in all age groups, in both sexes, and in both countries, except in girls 12 and younger and boys 4 and younger in South Africa.

“We noticed in the study that there was preferential mixing by gender,” Dr. Dodd said in an interview. “If there was the same amount of TB in men and women, you’d have expected women to be responsible for the majority of transmission to women and vice versa. But in fact there’s so much more TB in men, that they’re still responsible for the majority of transmission in women.”

Young children’s high proportion of TB infection attributable to contact with men was surprising, they noted, because their contact rates with women were higher. This suggests “that even in this age group, the higher prevalence in males tended to outweigh the higher contact rates between young children and women,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

Prevalence of TB was markedly higher in men than women (0.9% vs. 0.4% in Zambia, and 3% vs. 2% in South Africa). While the reasons for more TB in men are not well understood, these likely include both biological and social factors, including time before seeking care, and access to care. If men are slower to report or get diagnosed, because of work or other considerations, they will have higher prevalence of infectious TB disease, Dr. Dodd said. Preferential mixing by gender means that men are also more likely to be exposed to infectious TB by other men.

The study also found that incidence of infection was between 1.5 and 6 times higher in adults than was measured in children. “Adults are likely to have higher rates of exposure to TB, because adults on average have more contact with other adults than they do with children – and it’s the adults who tend to have infectious TB disease,” Dr. Dodd said.

Tuberculosis infection incidence based on surveys in children might underestimate true incidence in adults in TB-endemic settings, the researchers cautioned in their analysis.