User login

Women’s health 2015: An update for the internist

Women's health encompasses a broad range of issues unique to the female patient, with a scope that has expanded beyond reproductive health. Providers who care for women must develop cross-disciplinary competencies and understand the complex role of sex and gender on disease expression and treatment outcomes. Staying current with the literature in this rapidly changing field can be challenging for the busy clinician.

This article reviews recent advances in the treatment of depression in pregnancy, nonhormonal therapies for menopausal symptoms, and heart failure therapy in women, highlighting notable studies published in 2014 and early 2015.

TREATMENT OF DEPRESSION IN PREGNANCY

A 32-year-old woman with well-controlled but recurrent depression presents to the clinic for preconception counseling. Her depression has been successfully managed with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). She and her husband would like to try to conceive soon, but she is worried that continuing on her current SSRI may harm her baby. How should you advise her?

Concern for teratogenic effects of SSRIs

Depression is common during pregnancy: 11.8% to 13.5% of pregnant women report symptoms of depression,1 and 7.5% of pregnant women take an antidepressant.2

SSRI use during pregnancy has drawn attention because of mixed reports of teratogenic effects on the newborn, such as omphalocele, congenital heart defects, and craniosynostosis.3 Previous observational studies have specifically linked paroxetine to small but significant increases in right ventricular outflow tract obstruction4,5 and have linked sertraline to ventricular septal defects.6

However, reports of associations of congenital malformations and SSRI use in pregnancy in observational studies have been questioned, with concern that these studies had low statistical power, self-reported data leading to recall bias, and limited assessment for confounding factors.3,7

Recent studies refute risk of cardiac malformations

Several newer studies have been published that further examine the association between SSRI use in pregnancy and congenital heart defects, and their findings suggest that once adjusted for confounding variables, SSRI use in pregnancy may not be associated with cardiac malformations.

Huybrechts et al,8 in a large study published in 2014, extracted data on 950,000 pregnant women from the Medicaid database over a 7-year period and examined it for SSRI use during the first 90 days of pregnancy. Though SSRI use was associated with cardiac malformations when unadjusted for confounding variables (unadjusted relative risk 1.25, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.13–1.38), once the cohort was restricted to women with a diagnosis of only depression and was adjusted based on propensity scoring, the association was no longer statistically significant (adjusted relative risk 1.06, 95% CI 0.93–1.22).

Additionally, there was no association between sertraline and ventricular septal defects (63 cases in 14,040 women exposed to sertraline, adjusted relative risk 1.04, 95% CI 0.76–1.41), or between paroxetine and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (93 cases in 11,126 women exposed to paroxetine, adjusted relative risk 1.07, 95% CI 0.59–1.93).8

Furu et al7 conducted a sibling-matched case-control comparison published in 2015, in which more than 2 million live births from five Nordic countries were examined in the full cohort study and 2,288 births in the sibling-matched case-control cohort. SSRI or venlafaxine use in the first 90 days of pregnancy was examined. There was a slightly higher rate of cardiac defects in infants born to SSRI or venlafaxine recipients in the cohort study (adjusted odds ratio 1.15, 95% CI 1.05–1.26). However, in the sibling-controlled analyses, neither an SSRI nor venlafaxine was associated with heart defects (adjusted odds ratio 0.92, 95% CI 0.72–1.17), leading the authors to conclude that there might be familial factors or other lifestyle factors that were not taken into consideration and that could have confounded the cohort results.

Bérard et al9 examined antidepressant use in the first trimester of pregnancy in a cohort of women in Canada and concluded that sertraline was associated with congenital atrial and ventricular defects (risk ratio 1.34; 95% CI 1.02–1.76).9 However, this association should be interpreted with caution, as the Canadian cohort was notably smaller than those in other studies we have discussed, with only 18,493 pregnancies in the total cohort, and this conclusion was drawn from 9 cases of ventricular or atrial septal defects in babies of 366 women exposed to sertraline.

Although at first glance SSRIs may appear to be associated with congenital heart defects, these recent studies are reassuring and suggest that the association may actually not be significant. As with any statistical analysis, thoughtful study design, adequate statistical power, and adjustment for confounding factors must be considered before drawing conclusions.

SSRIs, offspring psychiatric outcomes, and miscarriage rates

Clements et al10 studied a cohort extracted from Partners Healthcare consisting of newborns with autism spectrum disorder, newborns with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and healthy matched controls and found that SSRI use during pregnancy was not associated with offspring autism spectrum disorder (adjusted odds ratio 1.10, 95% CI 0.7–1.70). However, they did find an increased risk of ADHD with SSRI use during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio 1.81, 95% CI 1.22–2.70).

Andersen et al11 examined more than 1 million pregnancies in Denmark and found no difference in risk of miscarriage between women who used an SSRI during pregnancy (adjusted hazard ratio 1.27) and women who discontinued their SSRI at least 3 months before pregnancy (adjusted hazard ratio 1.24, P = .47). The authors concluded that because of the similar rate of miscarriage in both groups, there was no association between SSRI use and miscarriage, and that the small increased risk of miscarriage in both groups could have been attributable to a confounding factor that was not measured.

Should our patient continue her SSRI through pregnancy?

Our patient has recurrent depression, and her risk of relapse with antidepressant cessation is high. Though previous, less well-done studies suggested a small risk of congenital heart defects, recent larger high-quality studies provide significant reassurance that SSRI use in pregnancy is not strongly associated with cardiac malformations. Recent studies also show no association with miscarriage or autism spectrum disorder, though there may be risk of offspring ADHD.

She can be counseled that she may continue on her SSRI during pregnancy and can be reassured that the risk to her baby is small compared with her risk of recurrent or postpartum depression.

NONHORMONAL TREATMENT FOR VASOMOTOR SYMPTOMS OF MENOPAUSE

You see a patient who is struggling with symptoms of menopause. She tells you she has terrible hot flashes day and night, and she would like to try drug therapy. She does not want hormone replacement therapy because she is worried about the risk of adverse events. Are there safe and effective nonhormonal pharmacologic treatments for her vasomotor symptoms?

Paroxetine 7.5 mg is approved for vasomotor symptoms of menopause

As many as 75% of menopausal women in the United States experience vasomotor symptoms related to menopause, or hot flashes and night sweats.12 These symptoms can disrupt sleep and negatively affect quality of life. Though previously thought to occur during a short and self-limited time period, a recently published large observational study reported the median duration of vasomotor symptoms was 7.4 years, and in African American women in the cohort the median duration of vasomotor symptoms was 10.1 years—an entire decade of life.13

In 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved paroxetine 7.5 mg daily for treating moderate to severe hot flashes associated with menopause. It is the only approved nonhormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms; the only other approved treatments are estrogen therapy for women who have had a hysterectomy and combination estrogen-progesterone therapy for women who have not had a hysterectomy.

Further studies of paroxetine for menopausal symptoms

Since its approval, further studies have been published supporting the use of paroxetine 7.5 mg in treating symptoms of menopause. In addition to reducing hot flashes, this treatment also improves sleep disturbance in women with menopause.14

Pinkerton et al,14 in a pooled analysis of the data from the phase 3 clinical trials of paroxetine 7.5 mg per day, found that participants in groups assigned to paroxetine reported a 62% reduction in nighttime awakenings due to hot flashes compared with a 43% reduction in the placebo group (P < .001). Those who took paroxetine also reported a statistically significantly greater increase in duration of sleep than those who took placebo (37 minutes in the treatment group vs 27 minutes in the placebo group, P = .03).

Some patients are hesitant to take an SSRI because of concerns about adverse effects when used for psychiatric conditions. However, the dose of paroxetine that was studied and approved for vasomotor symptoms is lower than doses used for psychiatric indications and does not appear to be associated with these adverse effects.

Portman et al15 in 2014 examined the effect of paroxetine 7.5 mg vs placebo on weight gain and sexual function in women with vasomotor symptoms of menopause and found no significant increase in weight or decrease in sexual function at 24 weeks of use. Participants were weighed during study visits, and those in the paroxetine group gained on average 0.48% from baseline at 24 weeks, compared with 0.09% in the placebo group (P = .29).

Sexual dysfunction was assessed using the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale, which has been validated in psychiatric patients using antidepressants, and there was no significant difference in symptoms such as sex drive, sexual arousal, vaginal lubrication, or ability to achieve orgasm between the treatment group and placebo group.15

Of note, paroxetine is a potent inhibitor of the cytochrome P-450 CYP2D6 enzyme, and concurrent use of paroxetine with tamoxifen decreases tamoxifen activity.12,16 Since women with a history of breast cancer who cannot use estrogen for hot flashes may be seeking nonhormonal treatment for their vasomotor symptoms, providers should perform careful medication reconciliation and be aware that concomitant use of paroxetine and tamoxifen is not recommended.

Other antidepressants show promise but are not approved for menopausal symptoms

In addition to paroxetine, other nonhormonal drugs have been studied for treating hot flashes, but they have been unable to secure FDA approval for this indication. One of these is the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine, and a 2014 study17 confirmed its efficacy in treating menopausal vasomotor symptoms.

Joffe et al17 performed a three-armed trial comparing venlafaxine 75 mg/day, estradiol 0.5 mg/day, and placebo and found that both of the active treatments were better than placebo at reducing vasomotor symptoms. Compared with each other, estradiol 0.5 mg/day reduced hot flash frequency by an additional 0.6 events per day compared with venlafaxine 75 mg/day (P = .09). Though this difference was statistically significant, the authors pointed out that the clinical significance of such a small absolute difference is questionable. Additionally, providers should be aware that venlafaxine has little or no effect on the metabolism of tamoxifen.16

Shams et al,18 in a meta-analysis published in 2014, concluded that SSRIs as a class are more effective than placebo in treating hot flashes, supporting their widespread off-label use for this purpose. Their analysis examined the results of 11 studies, which included more than 2,000 patients in total, and found that compared with placebo, SSRI use was associated with a significant decrease in hot flashes (mean difference –0.93 events per day, 95% CI –1.49 to –0.37). A mixed treatment comparison analysis was also performed to try to model performance of individual SSRIs based on the pooled data, and the model suggests that escitalopram may be the most efficacious SSRI at reducing hot flash severity.

These studies support the effectiveness of SSRIs18 and venlafaxine17 in reducing hot flashes compared with placebo, though providers should be aware that they are still not FDA-approved for this indication.

Nonhormonal therapy for our patient

We would recommend paroxetine 7.5 mg nightly to this patient, as it is an FDA-approved nonhormonal medication that has been shown to help patients with vasomotor symptoms of menopause as well as sleep disturbance, without sexual side effects or weight gain. If the patient cannot tolerate paroxetine, off-label use of another SSRI or venlafaxine is supported by the recent literature.

HEART DISEASE IN WOMEN: CARDIAC RESYNCHRONIZATION THERAPY

A 68-year-old woman with a history of nonischemic cardiomyopathy presents for routine follow-up in your office. Despite maximal medical therapy on a beta-blocker, an angiotensin II receptor blocker, and a diuretic, she has New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III symptoms. Her most recent studies showed an ejection fraction of 30% by echocardiography and left bundle-branch block on electrocardiography, with a QRS duration of 140 ms. She recently saw her cardiologist, who recommended cardiac resynchronization therapy, and she wants your opinion as to whether or not to proceed with this recommendation. How should you counsel her?

Which patients are candidates for cardiac resynchronization therapy?

Heart disease continues to be the number one cause of death in the United States for both men and women, and almost the same number of women and men die from heart disease every year.19 Though coronary artery disease accounts for most cases of cardiovascular disease in the United States, heart failure is a significant and growing contributor. Approximately 6.6 million adults had heart failure in 2010 in the United States, and an additional 3 million are projected to have heart failure by 2030.20 The burden of disease on our health system is high, with about 1 million hospitalizations and more than 3 million outpatient office visits attributable to heart failure yearly.20

Patients with heart failure may have symptoms of dyspnea, fatigue, orthopnea, and peripheral edema; laboratory and radiologic findings of pulmonary edema, renal insufficiency, and hyponatremia; and electrocardiographic findings of atrial fibrillation or prolonged QRS.21 Intraventricular conduction delay (QRS duration > 120 ms) is associated with dyssynchronous ventricular contraction and impaired pump function and is present in almost one-third of patients who have advanced heart failure.21

Cardiac resynchronization therapy, or biventricular pacing, can improve symptoms and pump function and has been shown to decrease rates of hospitalization and death in these patients.22 According to the joint 2012 guidelines of the American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association, and Heart Rhythm Society,22 it is indicated for patients with an ejection fraction of 35% or less, left bundle-branch block with QRS duration of 150 ms or more, and NYHA class II to IV symptoms who are in sinus rhythm (class I recommendation, level of evidence A).

Studies of cardiac resynchronization therapy in women

Recently published studies have suggested that women may derive greater benefit than men from cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Zusterzeel et al23 (2014) evaluated sex-specific data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, which contains data on all biventricular pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantations from 80% of US hospitals.23 Of the 21,152 patients who had left bundle-branch block and received cardiac resynchronization therapy, women derived greater benefit in terms of death than men did, with a 21% lower risk of death than men (adjusted hazard ratio 0.79, 95% CI 0.74–0.84, P < .001). This study was also notable in that 36% of the patients were women, whereas in most earlier studies of cardiac resynchronization therapy women accounted for only 22% to 30% of the study population.22

Goldenberg et al24 (2014) performed a follow-up analysis of the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial With Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. Subgroup analysis showed that although both men and women had a lower risk of death if they received cardiac resynchronization therapy compared with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator only, the magnitude of benefit may be greater for women (hazard ratio 0.48, 95% CI 0.25–0.91, P = .03) than for men (hazard ratio 0.69, 95% CI 0.50–0.95, P = .02).

In addition to deriving greater mortality benefit, women may actually benefit from cardiac resynchronization therapy at shorter QRS durations than what is currently recommended. Women have a shorter baseline QRS than men, and a smaller left ventricular cavity.25 In an FDA meta-analysis published in August 2014, pooled data from more than 4,000 patients in three studies suggested that women with left bundle-branch block benefited from cardiac resynchronization therapy more than men with left bundle-branch block.26 Neither men nor women with left bundle-branch block benefited from it if their QRS duration was less than 130 ms, and both sexes benefited from it if they had left bundle-branch block and a QRS duration longer than 150 ms. However, women who received it who had left bundle-branch block and a QRS duration of 130 to 149 ms had a significant 76% reduction in the primary composite outcome of a heart failure event or death (hazard ratio 0.24, 95% CI 0.11–0.53, P < .001), while men in the same group did not derive significant benefit (hazard ratio 0.85, 95% CI 0.60–1.21, P = .38).

Despite the increasing evidence that there are sex-specific differences in the benefit from cardiac resynchronization therapy, what we know is limited by the low rates of female enrollment in most of the studies of this treatment. In a systematic review published in 2015, Herz et al27 found that 90% of the 183 studies they reviewed enrolled 35% women or less, and half of the studies enrolled less than 23% women. Furthermore, only 20 of the 183 studies reported baseline characteristics by sex.

Recognizing this lack of adequate data, in August 2014 the FDA issued an official guidance statement outlining its expectations regarding sex-specific patient recruitment, data analysis, and data reporting in future medical device studies.28 Hopefully, with this support for sex-specific research by the FDA, future studies will be able to identify therapeutic outcome differences that may exist between male and female patients.

Should our patient receive cardiac resynchronization therapy?

Regarding our patient with heart failure, the above studies suggest she will likely have a lower risk of death if she receives cardiac resynchronization therapy, even though her QRS interval is shorter than 150 ms. Providers who are aware of the emerging data regarding sex differences and treatment response can be powerful advocates for their patients, even in subspecialty areas, as highlighted by this case. We recommend counseling this patient to proceed with cardiac resynchronization therapy.

- Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ 2001; 323:257–260.

- Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM, Kelley KE, Louik C, Hernández-Díaz S; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Medication use during pregnancy, with particular focus on prescription drugs: 1976–2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 205:51.e1–e8.

- Greene MF. Teratogenicity of SSRIs—serious concern or much ado about little? N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2732–2733.

- Louik C, Lin AE, Werler MM, Hernández-Díaz S, Mitchell AA. First-trimester use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2675–2683.

- Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, Olney RS, Friedman JM; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2684–2692.

- Pedersen LH, Henriksen TB, Vestergaard M, Olsen J, Bech BH. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and congenital malformations: population based cohort study. BMJ 2009; 339:b3569.

- Furu K, Kieler H, Haglund B, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine in early pregnancy and risk of birth defects: population based cohort study and sibling design. BMJ 2015; 350:h1798.

- Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Avorn J, et al. Antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac defects. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2397–2407.

- Bérard A, Zhao J-P, Sheehy O. Sertraline use during pregnancy and the risk of major malformations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015; 212:795.e1–795.e12.

- Clements CC, Castro VM, Blumenthal SR, et al. Prenatal antidepressant exposure is associated with risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder but not autism spectrum disorder in a large health system. Mol Psychiatry 2015; 20:727–734.

- Andersen JT, Andersen NL, Horwitz H, Poulsen HE, Jimenez-Solem E. Exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in early pregnancy and the risk of miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 124:655–661.

- Orleans RJ, Li L, Kim M-J, et al. FDA approval of paroxetine for menopausal hot flushes. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1777–1779.

- Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al; Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:531–539.

- Pinkerton JV, Joffe H, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Low-dose paroxetine (7.5 mg) improves sleep in women with vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Menopause 2015; 22:50–58.

- Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Effects of low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg on weight and sexual function during treatment of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Menopause 2014; 21:1082–1090.

- Desmarais JE, Looper KJ. Interactions between tamoxifen and antidepressants via cytochrome P450 2D6. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:1688–1697.

- Joffe H, Guthrie KA, LaCroix AZ, et al. Low-dose estradiol and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine for vasomotor symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174:1058–1066.

- Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med 2014; 29:204–213.

- Kochanek KD, Xu J, Murphy SL, Minino AM, Kung H-C. Deaths: final data for 2009. Nat Vital Stat Rep 2012; 60(3):1–117.

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—-2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012; 125:e2–e220.

- McMurray JJV. Clinical practice. Systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:228–238.

- Tracy CM, Epstein AE, Darbar D, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61:e6–e75.

- Zusterzeel R, Curtis JP, Canos DA, et al. Sex-specific mortality risk by QRS morphology and duration in patients receiving CRT. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:887–894.

- Goldenberg I, Kutyifa V, Klein HU, et al. Survival with cardiac-resynchronization therapy in mild heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1694–1701.

- Dec GW. Leaning toward a better understanding of CRT in women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:895–897.

- Zusterzeel R, Selzman KA, Sanders WE, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in women: US Food and Drug Administration meta-analysis of patient-level data. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174:1340–1348.

- Herz ND, Engeda J, Zusterzeel R, et al. Sex differences in device therapy for heart failure: utilization, outcomes, and adverse events. J Women’s Health 2015; 24:261–271.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Evaluation of sex-specific data in medical device clinical studies: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. 2014; 1–30. www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/UCM283707.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2015.

Women's health encompasses a broad range of issues unique to the female patient, with a scope that has expanded beyond reproductive health. Providers who care for women must develop cross-disciplinary competencies and understand the complex role of sex and gender on disease expression and treatment outcomes. Staying current with the literature in this rapidly changing field can be challenging for the busy clinician.

This article reviews recent advances in the treatment of depression in pregnancy, nonhormonal therapies for menopausal symptoms, and heart failure therapy in women, highlighting notable studies published in 2014 and early 2015.

TREATMENT OF DEPRESSION IN PREGNANCY

A 32-year-old woman with well-controlled but recurrent depression presents to the clinic for preconception counseling. Her depression has been successfully managed with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). She and her husband would like to try to conceive soon, but she is worried that continuing on her current SSRI may harm her baby. How should you advise her?

Concern for teratogenic effects of SSRIs

Depression is common during pregnancy: 11.8% to 13.5% of pregnant women report symptoms of depression,1 and 7.5% of pregnant women take an antidepressant.2

SSRI use during pregnancy has drawn attention because of mixed reports of teratogenic effects on the newborn, such as omphalocele, congenital heart defects, and craniosynostosis.3 Previous observational studies have specifically linked paroxetine to small but significant increases in right ventricular outflow tract obstruction4,5 and have linked sertraline to ventricular septal defects.6

However, reports of associations of congenital malformations and SSRI use in pregnancy in observational studies have been questioned, with concern that these studies had low statistical power, self-reported data leading to recall bias, and limited assessment for confounding factors.3,7

Recent studies refute risk of cardiac malformations

Several newer studies have been published that further examine the association between SSRI use in pregnancy and congenital heart defects, and their findings suggest that once adjusted for confounding variables, SSRI use in pregnancy may not be associated with cardiac malformations.

Huybrechts et al,8 in a large study published in 2014, extracted data on 950,000 pregnant women from the Medicaid database over a 7-year period and examined it for SSRI use during the first 90 days of pregnancy. Though SSRI use was associated with cardiac malformations when unadjusted for confounding variables (unadjusted relative risk 1.25, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.13–1.38), once the cohort was restricted to women with a diagnosis of only depression and was adjusted based on propensity scoring, the association was no longer statistically significant (adjusted relative risk 1.06, 95% CI 0.93–1.22).

Additionally, there was no association between sertraline and ventricular septal defects (63 cases in 14,040 women exposed to sertraline, adjusted relative risk 1.04, 95% CI 0.76–1.41), or between paroxetine and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (93 cases in 11,126 women exposed to paroxetine, adjusted relative risk 1.07, 95% CI 0.59–1.93).8

Furu et al7 conducted a sibling-matched case-control comparison published in 2015, in which more than 2 million live births from five Nordic countries were examined in the full cohort study and 2,288 births in the sibling-matched case-control cohort. SSRI or venlafaxine use in the first 90 days of pregnancy was examined. There was a slightly higher rate of cardiac defects in infants born to SSRI or venlafaxine recipients in the cohort study (adjusted odds ratio 1.15, 95% CI 1.05–1.26). However, in the sibling-controlled analyses, neither an SSRI nor venlafaxine was associated with heart defects (adjusted odds ratio 0.92, 95% CI 0.72–1.17), leading the authors to conclude that there might be familial factors or other lifestyle factors that were not taken into consideration and that could have confounded the cohort results.

Bérard et al9 examined antidepressant use in the first trimester of pregnancy in a cohort of women in Canada and concluded that sertraline was associated with congenital atrial and ventricular defects (risk ratio 1.34; 95% CI 1.02–1.76).9 However, this association should be interpreted with caution, as the Canadian cohort was notably smaller than those in other studies we have discussed, with only 18,493 pregnancies in the total cohort, and this conclusion was drawn from 9 cases of ventricular or atrial septal defects in babies of 366 women exposed to sertraline.

Although at first glance SSRIs may appear to be associated with congenital heart defects, these recent studies are reassuring and suggest that the association may actually not be significant. As with any statistical analysis, thoughtful study design, adequate statistical power, and adjustment for confounding factors must be considered before drawing conclusions.

SSRIs, offspring psychiatric outcomes, and miscarriage rates

Clements et al10 studied a cohort extracted from Partners Healthcare consisting of newborns with autism spectrum disorder, newborns with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and healthy matched controls and found that SSRI use during pregnancy was not associated with offspring autism spectrum disorder (adjusted odds ratio 1.10, 95% CI 0.7–1.70). However, they did find an increased risk of ADHD with SSRI use during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio 1.81, 95% CI 1.22–2.70).

Andersen et al11 examined more than 1 million pregnancies in Denmark and found no difference in risk of miscarriage between women who used an SSRI during pregnancy (adjusted hazard ratio 1.27) and women who discontinued their SSRI at least 3 months before pregnancy (adjusted hazard ratio 1.24, P = .47). The authors concluded that because of the similar rate of miscarriage in both groups, there was no association between SSRI use and miscarriage, and that the small increased risk of miscarriage in both groups could have been attributable to a confounding factor that was not measured.

Should our patient continue her SSRI through pregnancy?

Our patient has recurrent depression, and her risk of relapse with antidepressant cessation is high. Though previous, less well-done studies suggested a small risk of congenital heart defects, recent larger high-quality studies provide significant reassurance that SSRI use in pregnancy is not strongly associated with cardiac malformations. Recent studies also show no association with miscarriage or autism spectrum disorder, though there may be risk of offspring ADHD.

She can be counseled that she may continue on her SSRI during pregnancy and can be reassured that the risk to her baby is small compared with her risk of recurrent or postpartum depression.

NONHORMONAL TREATMENT FOR VASOMOTOR SYMPTOMS OF MENOPAUSE

You see a patient who is struggling with symptoms of menopause. She tells you she has terrible hot flashes day and night, and she would like to try drug therapy. She does not want hormone replacement therapy because she is worried about the risk of adverse events. Are there safe and effective nonhormonal pharmacologic treatments for her vasomotor symptoms?

Paroxetine 7.5 mg is approved for vasomotor symptoms of menopause

As many as 75% of menopausal women in the United States experience vasomotor symptoms related to menopause, or hot flashes and night sweats.12 These symptoms can disrupt sleep and negatively affect quality of life. Though previously thought to occur during a short and self-limited time period, a recently published large observational study reported the median duration of vasomotor symptoms was 7.4 years, and in African American women in the cohort the median duration of vasomotor symptoms was 10.1 years—an entire decade of life.13

In 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved paroxetine 7.5 mg daily for treating moderate to severe hot flashes associated with menopause. It is the only approved nonhormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms; the only other approved treatments are estrogen therapy for women who have had a hysterectomy and combination estrogen-progesterone therapy for women who have not had a hysterectomy.

Further studies of paroxetine for menopausal symptoms

Since its approval, further studies have been published supporting the use of paroxetine 7.5 mg in treating symptoms of menopause. In addition to reducing hot flashes, this treatment also improves sleep disturbance in women with menopause.14

Pinkerton et al,14 in a pooled analysis of the data from the phase 3 clinical trials of paroxetine 7.5 mg per day, found that participants in groups assigned to paroxetine reported a 62% reduction in nighttime awakenings due to hot flashes compared with a 43% reduction in the placebo group (P < .001). Those who took paroxetine also reported a statistically significantly greater increase in duration of sleep than those who took placebo (37 minutes in the treatment group vs 27 minutes in the placebo group, P = .03).

Some patients are hesitant to take an SSRI because of concerns about adverse effects when used for psychiatric conditions. However, the dose of paroxetine that was studied and approved for vasomotor symptoms is lower than doses used for psychiatric indications and does not appear to be associated with these adverse effects.

Portman et al15 in 2014 examined the effect of paroxetine 7.5 mg vs placebo on weight gain and sexual function in women with vasomotor symptoms of menopause and found no significant increase in weight or decrease in sexual function at 24 weeks of use. Participants were weighed during study visits, and those in the paroxetine group gained on average 0.48% from baseline at 24 weeks, compared with 0.09% in the placebo group (P = .29).

Sexual dysfunction was assessed using the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale, which has been validated in psychiatric patients using antidepressants, and there was no significant difference in symptoms such as sex drive, sexual arousal, vaginal lubrication, or ability to achieve orgasm between the treatment group and placebo group.15

Of note, paroxetine is a potent inhibitor of the cytochrome P-450 CYP2D6 enzyme, and concurrent use of paroxetine with tamoxifen decreases tamoxifen activity.12,16 Since women with a history of breast cancer who cannot use estrogen for hot flashes may be seeking nonhormonal treatment for their vasomotor symptoms, providers should perform careful medication reconciliation and be aware that concomitant use of paroxetine and tamoxifen is not recommended.

Other antidepressants show promise but are not approved for menopausal symptoms

In addition to paroxetine, other nonhormonal drugs have been studied for treating hot flashes, but they have been unable to secure FDA approval for this indication. One of these is the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine, and a 2014 study17 confirmed its efficacy in treating menopausal vasomotor symptoms.

Joffe et al17 performed a three-armed trial comparing venlafaxine 75 mg/day, estradiol 0.5 mg/day, and placebo and found that both of the active treatments were better than placebo at reducing vasomotor symptoms. Compared with each other, estradiol 0.5 mg/day reduced hot flash frequency by an additional 0.6 events per day compared with venlafaxine 75 mg/day (P = .09). Though this difference was statistically significant, the authors pointed out that the clinical significance of such a small absolute difference is questionable. Additionally, providers should be aware that venlafaxine has little or no effect on the metabolism of tamoxifen.16

Shams et al,18 in a meta-analysis published in 2014, concluded that SSRIs as a class are more effective than placebo in treating hot flashes, supporting their widespread off-label use for this purpose. Their analysis examined the results of 11 studies, which included more than 2,000 patients in total, and found that compared with placebo, SSRI use was associated with a significant decrease in hot flashes (mean difference –0.93 events per day, 95% CI –1.49 to –0.37). A mixed treatment comparison analysis was also performed to try to model performance of individual SSRIs based on the pooled data, and the model suggests that escitalopram may be the most efficacious SSRI at reducing hot flash severity.

These studies support the effectiveness of SSRIs18 and venlafaxine17 in reducing hot flashes compared with placebo, though providers should be aware that they are still not FDA-approved for this indication.

Nonhormonal therapy for our patient

We would recommend paroxetine 7.5 mg nightly to this patient, as it is an FDA-approved nonhormonal medication that has been shown to help patients with vasomotor symptoms of menopause as well as sleep disturbance, without sexual side effects or weight gain. If the patient cannot tolerate paroxetine, off-label use of another SSRI or venlafaxine is supported by the recent literature.

HEART DISEASE IN WOMEN: CARDIAC RESYNCHRONIZATION THERAPY

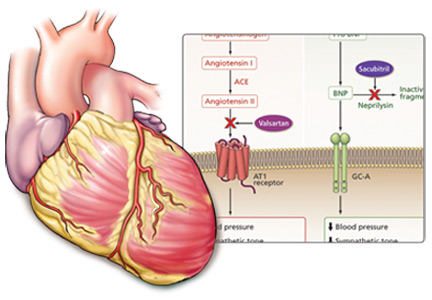

A 68-year-old woman with a history of nonischemic cardiomyopathy presents for routine follow-up in your office. Despite maximal medical therapy on a beta-blocker, an angiotensin II receptor blocker, and a diuretic, she has New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III symptoms. Her most recent studies showed an ejection fraction of 30% by echocardiography and left bundle-branch block on electrocardiography, with a QRS duration of 140 ms. She recently saw her cardiologist, who recommended cardiac resynchronization therapy, and she wants your opinion as to whether or not to proceed with this recommendation. How should you counsel her?

Which patients are candidates for cardiac resynchronization therapy?

Heart disease continues to be the number one cause of death in the United States for both men and women, and almost the same number of women and men die from heart disease every year.19 Though coronary artery disease accounts for most cases of cardiovascular disease in the United States, heart failure is a significant and growing contributor. Approximately 6.6 million adults had heart failure in 2010 in the United States, and an additional 3 million are projected to have heart failure by 2030.20 The burden of disease on our health system is high, with about 1 million hospitalizations and more than 3 million outpatient office visits attributable to heart failure yearly.20

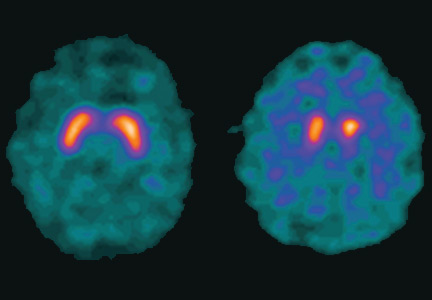

Patients with heart failure may have symptoms of dyspnea, fatigue, orthopnea, and peripheral edema; laboratory and radiologic findings of pulmonary edema, renal insufficiency, and hyponatremia; and electrocardiographic findings of atrial fibrillation or prolonged QRS.21 Intraventricular conduction delay (QRS duration > 120 ms) is associated with dyssynchronous ventricular contraction and impaired pump function and is present in almost one-third of patients who have advanced heart failure.21

Cardiac resynchronization therapy, or biventricular pacing, can improve symptoms and pump function and has been shown to decrease rates of hospitalization and death in these patients.22 According to the joint 2012 guidelines of the American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association, and Heart Rhythm Society,22 it is indicated for patients with an ejection fraction of 35% or less, left bundle-branch block with QRS duration of 150 ms or more, and NYHA class II to IV symptoms who are in sinus rhythm (class I recommendation, level of evidence A).

Studies of cardiac resynchronization therapy in women

Recently published studies have suggested that women may derive greater benefit than men from cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Zusterzeel et al23 (2014) evaluated sex-specific data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, which contains data on all biventricular pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantations from 80% of US hospitals.23 Of the 21,152 patients who had left bundle-branch block and received cardiac resynchronization therapy, women derived greater benefit in terms of death than men did, with a 21% lower risk of death than men (adjusted hazard ratio 0.79, 95% CI 0.74–0.84, P < .001). This study was also notable in that 36% of the patients were women, whereas in most earlier studies of cardiac resynchronization therapy women accounted for only 22% to 30% of the study population.22

Goldenberg et al24 (2014) performed a follow-up analysis of the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial With Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. Subgroup analysis showed that although both men and women had a lower risk of death if they received cardiac resynchronization therapy compared with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator only, the magnitude of benefit may be greater for women (hazard ratio 0.48, 95% CI 0.25–0.91, P = .03) than for men (hazard ratio 0.69, 95% CI 0.50–0.95, P = .02).

In addition to deriving greater mortality benefit, women may actually benefit from cardiac resynchronization therapy at shorter QRS durations than what is currently recommended. Women have a shorter baseline QRS than men, and a smaller left ventricular cavity.25 In an FDA meta-analysis published in August 2014, pooled data from more than 4,000 patients in three studies suggested that women with left bundle-branch block benefited from cardiac resynchronization therapy more than men with left bundle-branch block.26 Neither men nor women with left bundle-branch block benefited from it if their QRS duration was less than 130 ms, and both sexes benefited from it if they had left bundle-branch block and a QRS duration longer than 150 ms. However, women who received it who had left bundle-branch block and a QRS duration of 130 to 149 ms had a significant 76% reduction in the primary composite outcome of a heart failure event or death (hazard ratio 0.24, 95% CI 0.11–0.53, P < .001), while men in the same group did not derive significant benefit (hazard ratio 0.85, 95% CI 0.60–1.21, P = .38).

Despite the increasing evidence that there are sex-specific differences in the benefit from cardiac resynchronization therapy, what we know is limited by the low rates of female enrollment in most of the studies of this treatment. In a systematic review published in 2015, Herz et al27 found that 90% of the 183 studies they reviewed enrolled 35% women or less, and half of the studies enrolled less than 23% women. Furthermore, only 20 of the 183 studies reported baseline characteristics by sex.

Recognizing this lack of adequate data, in August 2014 the FDA issued an official guidance statement outlining its expectations regarding sex-specific patient recruitment, data analysis, and data reporting in future medical device studies.28 Hopefully, with this support for sex-specific research by the FDA, future studies will be able to identify therapeutic outcome differences that may exist between male and female patients.

Should our patient receive cardiac resynchronization therapy?

Regarding our patient with heart failure, the above studies suggest she will likely have a lower risk of death if she receives cardiac resynchronization therapy, even though her QRS interval is shorter than 150 ms. Providers who are aware of the emerging data regarding sex differences and treatment response can be powerful advocates for their patients, even in subspecialty areas, as highlighted by this case. We recommend counseling this patient to proceed with cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Women's health encompasses a broad range of issues unique to the female patient, with a scope that has expanded beyond reproductive health. Providers who care for women must develop cross-disciplinary competencies and understand the complex role of sex and gender on disease expression and treatment outcomes. Staying current with the literature in this rapidly changing field can be challenging for the busy clinician.

This article reviews recent advances in the treatment of depression in pregnancy, nonhormonal therapies for menopausal symptoms, and heart failure therapy in women, highlighting notable studies published in 2014 and early 2015.

TREATMENT OF DEPRESSION IN PREGNANCY

A 32-year-old woman with well-controlled but recurrent depression presents to the clinic for preconception counseling. Her depression has been successfully managed with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). She and her husband would like to try to conceive soon, but she is worried that continuing on her current SSRI may harm her baby. How should you advise her?

Concern for teratogenic effects of SSRIs

Depression is common during pregnancy: 11.8% to 13.5% of pregnant women report symptoms of depression,1 and 7.5% of pregnant women take an antidepressant.2

SSRI use during pregnancy has drawn attention because of mixed reports of teratogenic effects on the newborn, such as omphalocele, congenital heart defects, and craniosynostosis.3 Previous observational studies have specifically linked paroxetine to small but significant increases in right ventricular outflow tract obstruction4,5 and have linked sertraline to ventricular septal defects.6

However, reports of associations of congenital malformations and SSRI use in pregnancy in observational studies have been questioned, with concern that these studies had low statistical power, self-reported data leading to recall bias, and limited assessment for confounding factors.3,7

Recent studies refute risk of cardiac malformations

Several newer studies have been published that further examine the association between SSRI use in pregnancy and congenital heart defects, and their findings suggest that once adjusted for confounding variables, SSRI use in pregnancy may not be associated with cardiac malformations.

Huybrechts et al,8 in a large study published in 2014, extracted data on 950,000 pregnant women from the Medicaid database over a 7-year period and examined it for SSRI use during the first 90 days of pregnancy. Though SSRI use was associated with cardiac malformations when unadjusted for confounding variables (unadjusted relative risk 1.25, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.13–1.38), once the cohort was restricted to women with a diagnosis of only depression and was adjusted based on propensity scoring, the association was no longer statistically significant (adjusted relative risk 1.06, 95% CI 0.93–1.22).

Additionally, there was no association between sertraline and ventricular septal defects (63 cases in 14,040 women exposed to sertraline, adjusted relative risk 1.04, 95% CI 0.76–1.41), or between paroxetine and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (93 cases in 11,126 women exposed to paroxetine, adjusted relative risk 1.07, 95% CI 0.59–1.93).8

Furu et al7 conducted a sibling-matched case-control comparison published in 2015, in which more than 2 million live births from five Nordic countries were examined in the full cohort study and 2,288 births in the sibling-matched case-control cohort. SSRI or venlafaxine use in the first 90 days of pregnancy was examined. There was a slightly higher rate of cardiac defects in infants born to SSRI or venlafaxine recipients in the cohort study (adjusted odds ratio 1.15, 95% CI 1.05–1.26). However, in the sibling-controlled analyses, neither an SSRI nor venlafaxine was associated with heart defects (adjusted odds ratio 0.92, 95% CI 0.72–1.17), leading the authors to conclude that there might be familial factors or other lifestyle factors that were not taken into consideration and that could have confounded the cohort results.

Bérard et al9 examined antidepressant use in the first trimester of pregnancy in a cohort of women in Canada and concluded that sertraline was associated with congenital atrial and ventricular defects (risk ratio 1.34; 95% CI 1.02–1.76).9 However, this association should be interpreted with caution, as the Canadian cohort was notably smaller than those in other studies we have discussed, with only 18,493 pregnancies in the total cohort, and this conclusion was drawn from 9 cases of ventricular or atrial septal defects in babies of 366 women exposed to sertraline.

Although at first glance SSRIs may appear to be associated with congenital heart defects, these recent studies are reassuring and suggest that the association may actually not be significant. As with any statistical analysis, thoughtful study design, adequate statistical power, and adjustment for confounding factors must be considered before drawing conclusions.

SSRIs, offspring psychiatric outcomes, and miscarriage rates

Clements et al10 studied a cohort extracted from Partners Healthcare consisting of newborns with autism spectrum disorder, newborns with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and healthy matched controls and found that SSRI use during pregnancy was not associated with offspring autism spectrum disorder (adjusted odds ratio 1.10, 95% CI 0.7–1.70). However, they did find an increased risk of ADHD with SSRI use during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio 1.81, 95% CI 1.22–2.70).

Andersen et al11 examined more than 1 million pregnancies in Denmark and found no difference in risk of miscarriage between women who used an SSRI during pregnancy (adjusted hazard ratio 1.27) and women who discontinued their SSRI at least 3 months before pregnancy (adjusted hazard ratio 1.24, P = .47). The authors concluded that because of the similar rate of miscarriage in both groups, there was no association between SSRI use and miscarriage, and that the small increased risk of miscarriage in both groups could have been attributable to a confounding factor that was not measured.

Should our patient continue her SSRI through pregnancy?

Our patient has recurrent depression, and her risk of relapse with antidepressant cessation is high. Though previous, less well-done studies suggested a small risk of congenital heart defects, recent larger high-quality studies provide significant reassurance that SSRI use in pregnancy is not strongly associated with cardiac malformations. Recent studies also show no association with miscarriage or autism spectrum disorder, though there may be risk of offspring ADHD.

She can be counseled that she may continue on her SSRI during pregnancy and can be reassured that the risk to her baby is small compared with her risk of recurrent or postpartum depression.

NONHORMONAL TREATMENT FOR VASOMOTOR SYMPTOMS OF MENOPAUSE

You see a patient who is struggling with symptoms of menopause. She tells you she has terrible hot flashes day and night, and she would like to try drug therapy. She does not want hormone replacement therapy because she is worried about the risk of adverse events. Are there safe and effective nonhormonal pharmacologic treatments for her vasomotor symptoms?

Paroxetine 7.5 mg is approved for vasomotor symptoms of menopause

As many as 75% of menopausal women in the United States experience vasomotor symptoms related to menopause, or hot flashes and night sweats.12 These symptoms can disrupt sleep and negatively affect quality of life. Though previously thought to occur during a short and self-limited time period, a recently published large observational study reported the median duration of vasomotor symptoms was 7.4 years, and in African American women in the cohort the median duration of vasomotor symptoms was 10.1 years—an entire decade of life.13

In 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved paroxetine 7.5 mg daily for treating moderate to severe hot flashes associated with menopause. It is the only approved nonhormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms; the only other approved treatments are estrogen therapy for women who have had a hysterectomy and combination estrogen-progesterone therapy for women who have not had a hysterectomy.

Further studies of paroxetine for menopausal symptoms

Since its approval, further studies have been published supporting the use of paroxetine 7.5 mg in treating symptoms of menopause. In addition to reducing hot flashes, this treatment also improves sleep disturbance in women with menopause.14

Pinkerton et al,14 in a pooled analysis of the data from the phase 3 clinical trials of paroxetine 7.5 mg per day, found that participants in groups assigned to paroxetine reported a 62% reduction in nighttime awakenings due to hot flashes compared with a 43% reduction in the placebo group (P < .001). Those who took paroxetine also reported a statistically significantly greater increase in duration of sleep than those who took placebo (37 minutes in the treatment group vs 27 minutes in the placebo group, P = .03).

Some patients are hesitant to take an SSRI because of concerns about adverse effects when used for psychiatric conditions. However, the dose of paroxetine that was studied and approved for vasomotor symptoms is lower than doses used for psychiatric indications and does not appear to be associated with these adverse effects.

Portman et al15 in 2014 examined the effect of paroxetine 7.5 mg vs placebo on weight gain and sexual function in women with vasomotor symptoms of menopause and found no significant increase in weight or decrease in sexual function at 24 weeks of use. Participants were weighed during study visits, and those in the paroxetine group gained on average 0.48% from baseline at 24 weeks, compared with 0.09% in the placebo group (P = .29).

Sexual dysfunction was assessed using the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale, which has been validated in psychiatric patients using antidepressants, and there was no significant difference in symptoms such as sex drive, sexual arousal, vaginal lubrication, or ability to achieve orgasm between the treatment group and placebo group.15

Of note, paroxetine is a potent inhibitor of the cytochrome P-450 CYP2D6 enzyme, and concurrent use of paroxetine with tamoxifen decreases tamoxifen activity.12,16 Since women with a history of breast cancer who cannot use estrogen for hot flashes may be seeking nonhormonal treatment for their vasomotor symptoms, providers should perform careful medication reconciliation and be aware that concomitant use of paroxetine and tamoxifen is not recommended.

Other antidepressants show promise but are not approved for menopausal symptoms

In addition to paroxetine, other nonhormonal drugs have been studied for treating hot flashes, but they have been unable to secure FDA approval for this indication. One of these is the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine, and a 2014 study17 confirmed its efficacy in treating menopausal vasomotor symptoms.

Joffe et al17 performed a three-armed trial comparing venlafaxine 75 mg/day, estradiol 0.5 mg/day, and placebo and found that both of the active treatments were better than placebo at reducing vasomotor symptoms. Compared with each other, estradiol 0.5 mg/day reduced hot flash frequency by an additional 0.6 events per day compared with venlafaxine 75 mg/day (P = .09). Though this difference was statistically significant, the authors pointed out that the clinical significance of such a small absolute difference is questionable. Additionally, providers should be aware that venlafaxine has little or no effect on the metabolism of tamoxifen.16

Shams et al,18 in a meta-analysis published in 2014, concluded that SSRIs as a class are more effective than placebo in treating hot flashes, supporting their widespread off-label use for this purpose. Their analysis examined the results of 11 studies, which included more than 2,000 patients in total, and found that compared with placebo, SSRI use was associated with a significant decrease in hot flashes (mean difference –0.93 events per day, 95% CI –1.49 to –0.37). A mixed treatment comparison analysis was also performed to try to model performance of individual SSRIs based on the pooled data, and the model suggests that escitalopram may be the most efficacious SSRI at reducing hot flash severity.

These studies support the effectiveness of SSRIs18 and venlafaxine17 in reducing hot flashes compared with placebo, though providers should be aware that they are still not FDA-approved for this indication.

Nonhormonal therapy for our patient

We would recommend paroxetine 7.5 mg nightly to this patient, as it is an FDA-approved nonhormonal medication that has been shown to help patients with vasomotor symptoms of menopause as well as sleep disturbance, without sexual side effects or weight gain. If the patient cannot tolerate paroxetine, off-label use of another SSRI or venlafaxine is supported by the recent literature.

HEART DISEASE IN WOMEN: CARDIAC RESYNCHRONIZATION THERAPY

A 68-year-old woman with a history of nonischemic cardiomyopathy presents for routine follow-up in your office. Despite maximal medical therapy on a beta-blocker, an angiotensin II receptor blocker, and a diuretic, she has New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III symptoms. Her most recent studies showed an ejection fraction of 30% by echocardiography and left bundle-branch block on electrocardiography, with a QRS duration of 140 ms. She recently saw her cardiologist, who recommended cardiac resynchronization therapy, and she wants your opinion as to whether or not to proceed with this recommendation. How should you counsel her?

Which patients are candidates for cardiac resynchronization therapy?

Heart disease continues to be the number one cause of death in the United States for both men and women, and almost the same number of women and men die from heart disease every year.19 Though coronary artery disease accounts for most cases of cardiovascular disease in the United States, heart failure is a significant and growing contributor. Approximately 6.6 million adults had heart failure in 2010 in the United States, and an additional 3 million are projected to have heart failure by 2030.20 The burden of disease on our health system is high, with about 1 million hospitalizations and more than 3 million outpatient office visits attributable to heart failure yearly.20

Patients with heart failure may have symptoms of dyspnea, fatigue, orthopnea, and peripheral edema; laboratory and radiologic findings of pulmonary edema, renal insufficiency, and hyponatremia; and electrocardiographic findings of atrial fibrillation or prolonged QRS.21 Intraventricular conduction delay (QRS duration > 120 ms) is associated with dyssynchronous ventricular contraction and impaired pump function and is present in almost one-third of patients who have advanced heart failure.21

Cardiac resynchronization therapy, or biventricular pacing, can improve symptoms and pump function and has been shown to decrease rates of hospitalization and death in these patients.22 According to the joint 2012 guidelines of the American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association, and Heart Rhythm Society,22 it is indicated for patients with an ejection fraction of 35% or less, left bundle-branch block with QRS duration of 150 ms or more, and NYHA class II to IV symptoms who are in sinus rhythm (class I recommendation, level of evidence A).

Studies of cardiac resynchronization therapy in women

Recently published studies have suggested that women may derive greater benefit than men from cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Zusterzeel et al23 (2014) evaluated sex-specific data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, which contains data on all biventricular pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantations from 80% of US hospitals.23 Of the 21,152 patients who had left bundle-branch block and received cardiac resynchronization therapy, women derived greater benefit in terms of death than men did, with a 21% lower risk of death than men (adjusted hazard ratio 0.79, 95% CI 0.74–0.84, P < .001). This study was also notable in that 36% of the patients were women, whereas in most earlier studies of cardiac resynchronization therapy women accounted for only 22% to 30% of the study population.22

Goldenberg et al24 (2014) performed a follow-up analysis of the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial With Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. Subgroup analysis showed that although both men and women had a lower risk of death if they received cardiac resynchronization therapy compared with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator only, the magnitude of benefit may be greater for women (hazard ratio 0.48, 95% CI 0.25–0.91, P = .03) than for men (hazard ratio 0.69, 95% CI 0.50–0.95, P = .02).

In addition to deriving greater mortality benefit, women may actually benefit from cardiac resynchronization therapy at shorter QRS durations than what is currently recommended. Women have a shorter baseline QRS than men, and a smaller left ventricular cavity.25 In an FDA meta-analysis published in August 2014, pooled data from more than 4,000 patients in three studies suggested that women with left bundle-branch block benefited from cardiac resynchronization therapy more than men with left bundle-branch block.26 Neither men nor women with left bundle-branch block benefited from it if their QRS duration was less than 130 ms, and both sexes benefited from it if they had left bundle-branch block and a QRS duration longer than 150 ms. However, women who received it who had left bundle-branch block and a QRS duration of 130 to 149 ms had a significant 76% reduction in the primary composite outcome of a heart failure event or death (hazard ratio 0.24, 95% CI 0.11–0.53, P < .001), while men in the same group did not derive significant benefit (hazard ratio 0.85, 95% CI 0.60–1.21, P = .38).

Despite the increasing evidence that there are sex-specific differences in the benefit from cardiac resynchronization therapy, what we know is limited by the low rates of female enrollment in most of the studies of this treatment. In a systematic review published in 2015, Herz et al27 found that 90% of the 183 studies they reviewed enrolled 35% women or less, and half of the studies enrolled less than 23% women. Furthermore, only 20 of the 183 studies reported baseline characteristics by sex.

Recognizing this lack of adequate data, in August 2014 the FDA issued an official guidance statement outlining its expectations regarding sex-specific patient recruitment, data analysis, and data reporting in future medical device studies.28 Hopefully, with this support for sex-specific research by the FDA, future studies will be able to identify therapeutic outcome differences that may exist between male and female patients.

Should our patient receive cardiac resynchronization therapy?

Regarding our patient with heart failure, the above studies suggest she will likely have a lower risk of death if she receives cardiac resynchronization therapy, even though her QRS interval is shorter than 150 ms. Providers who are aware of the emerging data regarding sex differences and treatment response can be powerful advocates for their patients, even in subspecialty areas, as highlighted by this case. We recommend counseling this patient to proceed with cardiac resynchronization therapy.

- Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ 2001; 323:257–260.

- Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM, Kelley KE, Louik C, Hernández-Díaz S; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Medication use during pregnancy, with particular focus on prescription drugs: 1976–2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 205:51.e1–e8.

- Greene MF. Teratogenicity of SSRIs—serious concern or much ado about little? N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2732–2733.

- Louik C, Lin AE, Werler MM, Hernández-Díaz S, Mitchell AA. First-trimester use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2675–2683.

- Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, Olney RS, Friedman JM; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2684–2692.

- Pedersen LH, Henriksen TB, Vestergaard M, Olsen J, Bech BH. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and congenital malformations: population based cohort study. BMJ 2009; 339:b3569.

- Furu K, Kieler H, Haglund B, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine in early pregnancy and risk of birth defects: population based cohort study and sibling design. BMJ 2015; 350:h1798.

- Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Avorn J, et al. Antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac defects. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2397–2407.

- Bérard A, Zhao J-P, Sheehy O. Sertraline use during pregnancy and the risk of major malformations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015; 212:795.e1–795.e12.

- Clements CC, Castro VM, Blumenthal SR, et al. Prenatal antidepressant exposure is associated with risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder but not autism spectrum disorder in a large health system. Mol Psychiatry 2015; 20:727–734.

- Andersen JT, Andersen NL, Horwitz H, Poulsen HE, Jimenez-Solem E. Exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in early pregnancy and the risk of miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 124:655–661.

- Orleans RJ, Li L, Kim M-J, et al. FDA approval of paroxetine for menopausal hot flushes. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1777–1779.

- Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al; Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:531–539.

- Pinkerton JV, Joffe H, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Low-dose paroxetine (7.5 mg) improves sleep in women with vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Menopause 2015; 22:50–58.

- Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Effects of low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg on weight and sexual function during treatment of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Menopause 2014; 21:1082–1090.

- Desmarais JE, Looper KJ. Interactions between tamoxifen and antidepressants via cytochrome P450 2D6. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:1688–1697.

- Joffe H, Guthrie KA, LaCroix AZ, et al. Low-dose estradiol and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine for vasomotor symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174:1058–1066.

- Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med 2014; 29:204–213.

- Kochanek KD, Xu J, Murphy SL, Minino AM, Kung H-C. Deaths: final data for 2009. Nat Vital Stat Rep 2012; 60(3):1–117.

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—-2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012; 125:e2–e220.

- McMurray JJV. Clinical practice. Systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:228–238.

- Tracy CM, Epstein AE, Darbar D, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61:e6–e75.

- Zusterzeel R, Curtis JP, Canos DA, et al. Sex-specific mortality risk by QRS morphology and duration in patients receiving CRT. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:887–894.

- Goldenberg I, Kutyifa V, Klein HU, et al. Survival with cardiac-resynchronization therapy in mild heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1694–1701.

- Dec GW. Leaning toward a better understanding of CRT in women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:895–897.

- Zusterzeel R, Selzman KA, Sanders WE, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in women: US Food and Drug Administration meta-analysis of patient-level data. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174:1340–1348.

- Herz ND, Engeda J, Zusterzeel R, et al. Sex differences in device therapy for heart failure: utilization, outcomes, and adverse events. J Women’s Health 2015; 24:261–271.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Evaluation of sex-specific data in medical device clinical studies: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. 2014; 1–30. www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/UCM283707.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2015.

- Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ 2001; 323:257–260.

- Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM, Kelley KE, Louik C, Hernández-Díaz S; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Medication use during pregnancy, with particular focus on prescription drugs: 1976–2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 205:51.e1–e8.

- Greene MF. Teratogenicity of SSRIs—serious concern or much ado about little? N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2732–2733.

- Louik C, Lin AE, Werler MM, Hernández-Díaz S, Mitchell AA. First-trimester use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2675–2683.

- Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, Olney RS, Friedman JM; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2684–2692.

- Pedersen LH, Henriksen TB, Vestergaard M, Olsen J, Bech BH. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and congenital malformations: population based cohort study. BMJ 2009; 339:b3569.

- Furu K, Kieler H, Haglund B, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine in early pregnancy and risk of birth defects: population based cohort study and sibling design. BMJ 2015; 350:h1798.

- Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Avorn J, et al. Antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac defects. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2397–2407.

- Bérard A, Zhao J-P, Sheehy O. Sertraline use during pregnancy and the risk of major malformations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015; 212:795.e1–795.e12.

- Clements CC, Castro VM, Blumenthal SR, et al. Prenatal antidepressant exposure is associated with risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder but not autism spectrum disorder in a large health system. Mol Psychiatry 2015; 20:727–734.

- Andersen JT, Andersen NL, Horwitz H, Poulsen HE, Jimenez-Solem E. Exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in early pregnancy and the risk of miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 124:655–661.

- Orleans RJ, Li L, Kim M-J, et al. FDA approval of paroxetine for menopausal hot flushes. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1777–1779.

- Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al; Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:531–539.

- Pinkerton JV, Joffe H, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Low-dose paroxetine (7.5 mg) improves sleep in women with vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Menopause 2015; 22:50–58.

- Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Effects of low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg on weight and sexual function during treatment of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Menopause 2014; 21:1082–1090.

- Desmarais JE, Looper KJ. Interactions between tamoxifen and antidepressants via cytochrome P450 2D6. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:1688–1697.

- Joffe H, Guthrie KA, LaCroix AZ, et al. Low-dose estradiol and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine for vasomotor symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174:1058–1066.

- Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med 2014; 29:204–213.

- Kochanek KD, Xu J, Murphy SL, Minino AM, Kung H-C. Deaths: final data for 2009. Nat Vital Stat Rep 2012; 60(3):1–117.

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—-2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012; 125:e2–e220.

- McMurray JJV. Clinical practice. Systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:228–238.

- Tracy CM, Epstein AE, Darbar D, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61:e6–e75.

- Zusterzeel R, Curtis JP, Canos DA, et al. Sex-specific mortality risk by QRS morphology and duration in patients receiving CRT. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:887–894.

- Goldenberg I, Kutyifa V, Klein HU, et al. Survival with cardiac-resynchronization therapy in mild heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1694–1701.

- Dec GW. Leaning toward a better understanding of CRT in women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:895–897.

- Zusterzeel R, Selzman KA, Sanders WE, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in women: US Food and Drug Administration meta-analysis of patient-level data. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174:1340–1348.

- Herz ND, Engeda J, Zusterzeel R, et al. Sex differences in device therapy for heart failure: utilization, outcomes, and adverse events. J Women’s Health 2015; 24:261–271.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Evaluation of sex-specific data in medical device clinical studies: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. 2014; 1–30. www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/UCM283707.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2015.

KEY POINTS

- Earlier trials had raised concerns about possible teratogenic effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, but more recent trials have found no strong association between these drugs and congenital heart defects, and no association with miscarriage or autism spectrum disorder, though there may be a risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in offspring.

- Paroxetine is approved for treating vasomotor symptoms of menopause, but in a lower dose (7.5 mg) than those used for depression and other psychiatric indications. Clinical trials have also shown good results with other antidepressants for treating hot flashes, but the drugs are not yet approved for this indication.

- Women with heart failure and left bundle-branch block can decrease their risk of death with cardiac resynchronization therapy more than men with the same condition. Moreover, women may benefit from this therapy even if their QRS duration is somewhat shorter than the established cutoff, ie, if it is in the range of 130 to 149 ms.

Should all patients with significant proteinuria take a renin-angiotensin inhibitor?

Most patients with proteinuria benefit from a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitor. Exceptions due to adverse effects are discussed below.

WHY RAAS INHIBITORS?

RAAS inhibitors—particularly angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs)—reduce proteinuria and slow the progression of chronic kidney disease by improving glomerular hemodynamics, restoring the altered glomerular barrier function, and limiting the nonhemodynamic effects of angiotensin II and aldosterone, such as fibrosis and vascular endothelial dysfunction.1 Studies have shown that these protective effects are, at least in part, independent of the reduction in systemic blood pressure.2,3

EVIDENCE FOR USING RAAS INHIBITORS IN PATIENTS WITH PROTEINURIA

In nondiabetic kidney disease, there is strong evidence from the REIN and AASK trials that treatment with ACE inhibitors results in slower decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and this risk reduction is more pronounced in patients with a higher degree of proteinuria.4–6

In type 1 diabetes, treatment with an ACE inhibitor in patients with overt proteinuria was associated with a 50% decrease in the risk of the combined end point of death, dialysis, or renal transplant.7 Patients with moderately increased albuminuria who were treated with an ACE inhibitor also had a reduced incidence of progression to overt proteinuria.8 Angiotensin inhibition may be beneficial even in normotensive patients with type 1 diabetes and persistent moderately increased albuminuria.9,10

In type 2 diabetes, the IDNT and RENAAL trials showed that treatment with an ARB in patients with overt nephropathy was associated with a statistically significant decrease (20% in IDNT, 16% in RENAAL) in the risk of the combined end point of death, end-stage renal disease, or doubling of serum creatinine.11,12 While there are more data for ARBs than for ACE inhibitors in type 2 diabetes, the DETAIL study showed that an ACE inhibitor was at least as effective as an ARB in providing long-term renal protection in type 2 diabetes and moderately increased albuminuria.13

Data are limited on the role of angiotensin inhibition in normotensive patients with type 2 diabetes and persistent moderately increased albuminuria, but consensus opinion suggests treatment with an ACE inhibitor or ARB in these patients if there are no contraindications.

LIMITATIONS

Adverse effects of ACE inhibitors and ARBs include cough (more with ACE inhibitors), angioedema (more with ACE inhibitors), and hyperkalemia.