User login

Telemedicine Alopecia Assessment: Highlighting Patients With Skin of Color

Practice Gap

In accordance with World Health Organization guidelines on social distancing to limit transmission of SARS-CoV-2, dermatologists have relied on teledermatology (TD) to develop novel adaptations of traditional workflows, optimize patient care, and limit in-person appointments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pandemic-induced physical and emotional stress were anticipated to increase the incidence of dermatologic diseases with psychologic triggers.

The connection between hair loss and emotional stress is well documented for telogen effluvium and alopecia areata.1,2 As anticipated, dermatology visits increased during the COVID-19 pandemic for the diagnosis of alopecia1-4; a survey performed during the pandemic found that alopecia was one of the most common diagnoses dermatologists made through telehealth platforms.5

This article provides a practical guide for dermatology practitioners to efficiently and accurately assess alopecia by TD in all patients, with added considerations for skin of color patients.

Diagnostic Tools

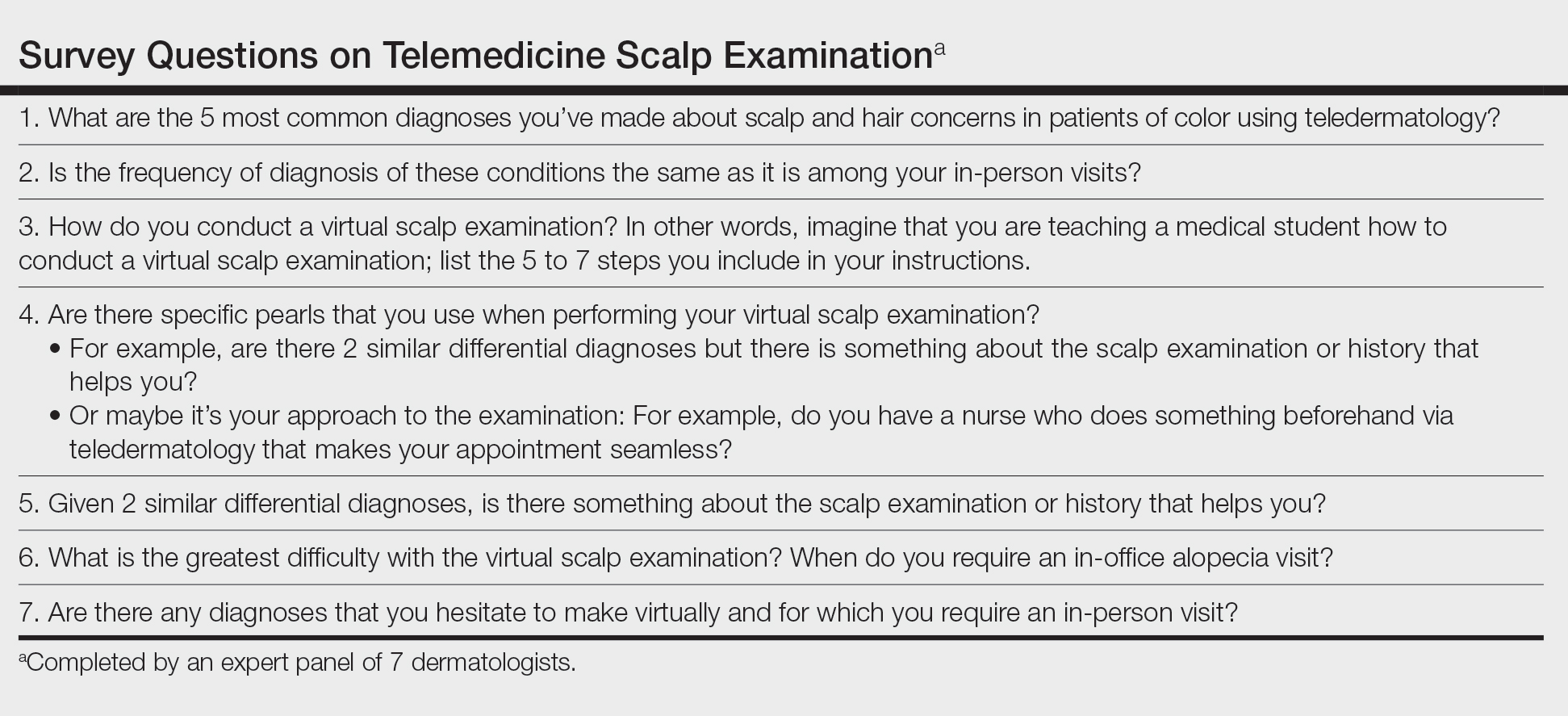

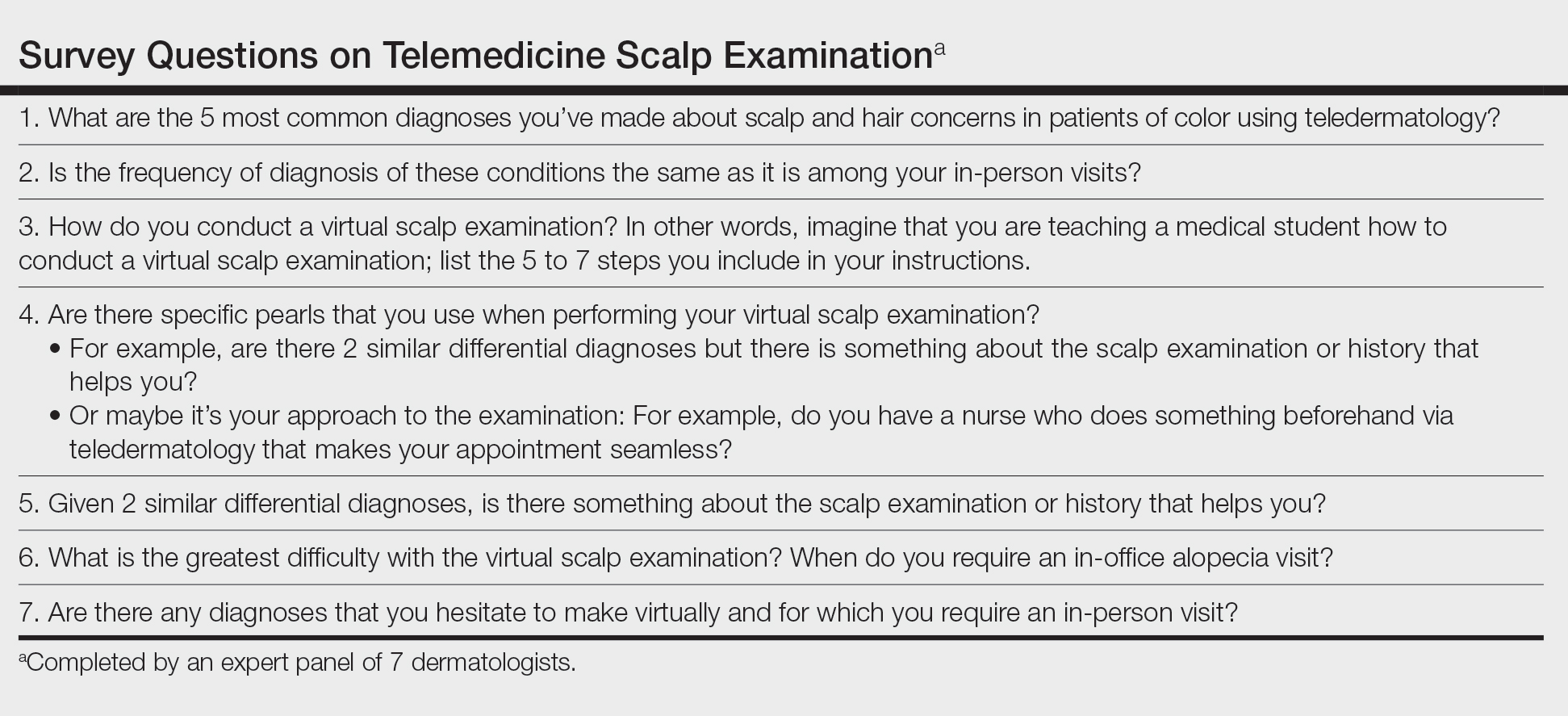

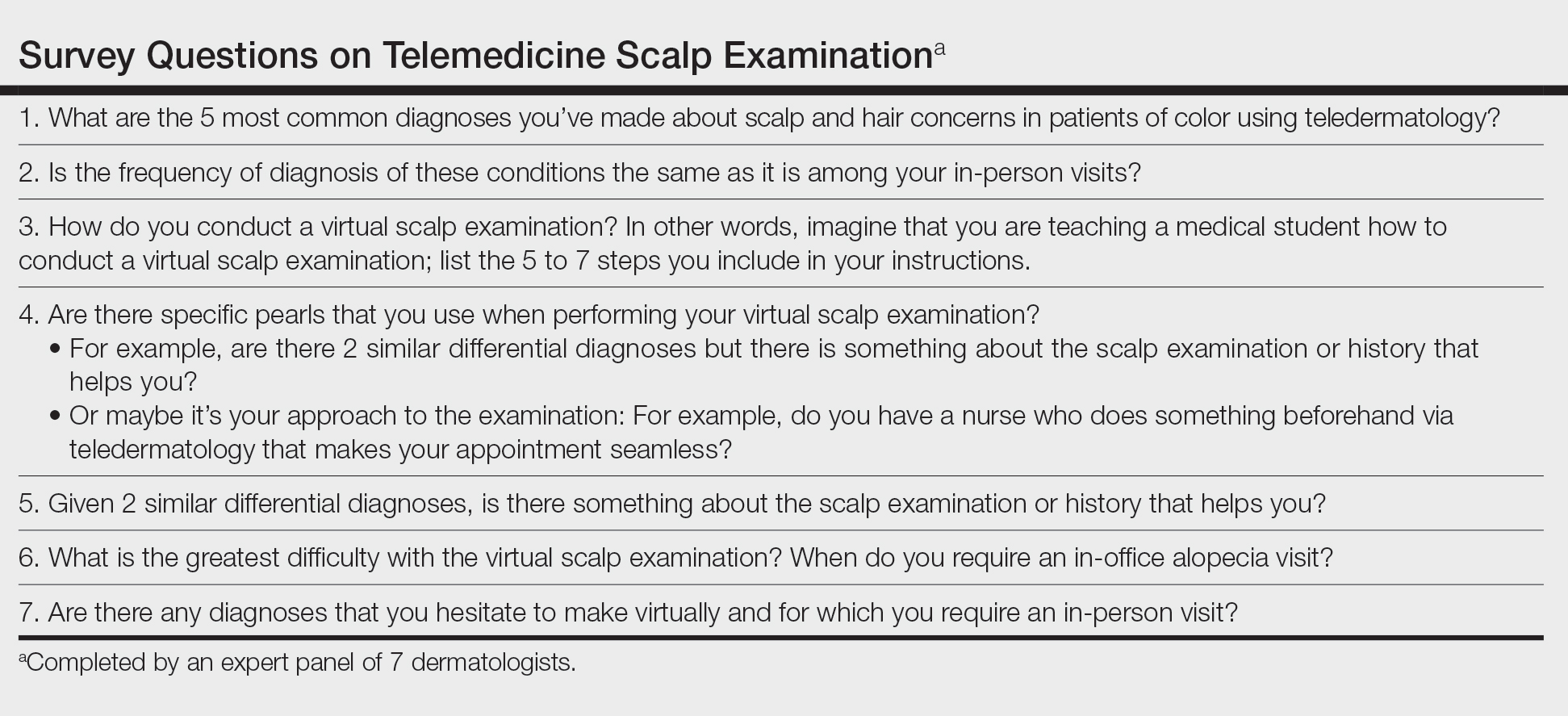

The intersection of TD, as an effective mechanism for the diagnosis and treatment of dermatologic disorders, and the increase in alopecia observed during the COVID-19 pandemic prompted us to develop a workflow for conducting virtual scalp examinations. Seven dermatologists (A.M., A.A., O.A., N.E., V.C., C.M.B., S.C.T.) who are experts in hair disorders contributed to developing workflows to optimize the assessment of alopecia through a virtual scalp examination, with an emphasis on patients of color. These experts completed a 7-question survey (Table) detailing their approach to the virtual scalp examination. One author (B.N.W.) served as an independent reviewer and collated responses into the following workflows.

Telemedicine Previsit Workflow

Components of the previsit workflow include:

• Instruct patients to provide all laboratory values and biopsy reports before the appointment.

• Test for a stable Wi-Fi connection using a speed test (available at https://www.speedtest.net/). A speed of 10 megabits/second or more is required for high-quality video via TD.6

• Provide a handout illustrating the required photographs of the anterior hairline; the mid scalp, including vertex, bilateral parietal, and occipital scalp; and posterior hairline. Photographs should be uploaded 2 hours before the visit. Figures 1 and 2 are examples of photographs that should be requested.

• Request images with 2 or 3 different angles of the area of the scalp with the greatest involvement to help appreciate primary and secondary characteristics.

• Encourage patients to present with clean, recently shampooed, dried, and detangled natural hair, unless they have an itchy or flaky scalp.

• For concerns of scalp, hairline, eyebrow, or facial flaking and scaling, instruct the patient to avoid applying a moisturizer before the visit.

• Instruct the patient to remove false eyelashes, eyelash extensions, eyebrow pencil, hair camouflage, hair accessories, braids, extensions, weaves, twists, and other hairstyles so that the hair can be maneuvered to expose the scalp surface.

• Instruct the patient to have a comb, pic, or brush, or more than one of these implements, available during the visit.

Telemedicine Visit Workflow

Components of the visit workflow include:

• If a stable Wi-Fi connection cannot be established, switch to an audio-only visit to collect a pertinent history. Advise the patient that in-person follow-up must be scheduled.

• Confirm that (1) the patient is in a private setting where the scalp can be viewed and (2) lighting is positioned in front of the patient.

• Ensure that the patient’s hairline, full face, eyebrows, and eyelashes and, upon request, the vertex and posterior scalp, are completely visible.

• Initiate the virtual scalp examination by instructing the patient how to perform a hair pull test. Then, examine the pattern and distribution of hair loss alongside supplemental photographs.

• Instruct the patient to apply pressure with the fingertips throughout the scalp to help localize tenderness, which, in combination with the pattern of hair loss observed, might inform the diagnosis.

• Instruct the patient to scan the scalp with the fingertips for “bumps” to locate papules, pustules, and keloidal scars.

Diagnostic Pearls

Distribution of Alopecia—The experts noted that the pattern, distribution, and location of hair loss determined from the telemedicine alopecia assessment provided important clues to distinguish the type of alopecia.

Diagnostic clues for diffuse or generalized alopecia include:

• Either of these findings might be indicative of telogen effluvium or acquired trichorrhexis nodosa. Results of the hair pull test can help distinguish between these diagnoses.

• Recent stressful life events along with the presence of telogen hairs extracted during a hair pull test support the diagnosis of telogen effluvium.

• A history of external stress on the hair—thermal, traction, or chemical—along with broken hair shafts following the hair pull test support the diagnosis of acquired trichorrhexis nodosa.

Diagnostic clues for focal or patchy alopecia include:

• Alopecia areata generally presents as focal hair loss in an annular distribution; pruritus, erythema, and scale are absent.

• Seborrheic dermatitis can present as pruritic erythematous patches with scale distributed on the scalp and, in some cases, in the eyebrows, nasolabial folds, or paranasal skin.7 Some skin of color patients present with petaloid seborrheic dermatitis—pink or hypopigmented polycyclic coalescing rings with minimal scale.7,8

• Discoid lupus erythematosus, similar to seborrheic dermatitis, might present as pruritic, scaly, hypopigmented patches. However, in the experience of the experts, a more common presentation is tender erythematous patches of hair loss with central hypopigmentation and surrounding hyperpigmentation.

Diagnostic clues for vertex and mid scalp alopecia include:

• Androgenetic alopecia typically presents as a reduction of terminal hair density in the vertex and mid scalp regions (with widening through the midline part) and fine hair along the anterior hairline.9 Signs of concomitant hyperandrogenism, including facial hirsutism, acne, and obesity, might be observed.10

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia typically affects the vertex and mid scalp with a shiny scalp appearance and follicular dropout.

Diagnostic clues for frontotemporal alopecia include:

• Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) often presents with spared single terminal hairs (lonely hair sign).

• Traction alopecia commonly presents with the fringe hair sign.

Scalp Symptoms—The experts noted that the presence of symptoms (eg, pain, tenderness, pruritus) in conjunction with the pattern of hair loss might support the diagnosis of an inflammatory scarring alopecia.

When do symptoms raise suspicion of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia?

• Suspected in the setting of vertex alopecia associated with tenderness, pain, or itching.

When do symptoms raise suspicion of FFA?

• Suspected when patients experience frontotemporal tenderness, pain, or burning associated with alopecia.

• The skin hue of the affected area might be lighter in color than, and contrast with, the darker hue of the photoaged upper forehead.11

• The lonely hair sign can aid in diagnosing FFA and distinguish it from the fringe sign of traction alopecia.

• Concurrent madarosis, flesh-colored papules on the cheeks, or lichen planus pigmentosus identified by visual inspection of the face confirms the diagnosis.9,12 Madarosis of the eyebrow was frequently cited by the experts as an associated symptom of FFA.

When do symptoms raise suspicion of lichen planopilaris?

• Suspected in the presence of pruritus, burning, tenderness, or pain associated with perifollicular erythema and scale in the setting of vertex and parietal alopecia.13

• Anagen hair release is observed during the hair pull test.11,14• The experts cited flesh-colored papules and lichen planus pigmentosus as frequently associated symptoms of lichen planopilaris.

Practice Implications

There are limitations to a virtual scalp examination—the inability to perform a scalp biopsy or administer certain treatments—but the consensus of the expert panel is that an initial alopecia assessment can be completed successfully utilizing TD. Although TD is not a replacement for an in-person dermatology visit, this technology has allowed for the diagnosis, treatment, and continuing care of many common dermatologic conditions without the patient needing to travel to the office.5

With the increased frequency of hair loss concerns documented over the last year and more patients seeking TD, it is imperative that dermatologists feel confident performing a virtual hair and scalp examination on all patients.1,3,4

- Kutlu Ö, Aktas¸ H, I·mren IG, et al. Short-term stress-related increasing cases of alopecia areata during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;1. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1782820

- Cline A, Kazemi A, Moy J, et al. A surge in the incidence of telogen effluvium in minority predominant communities heavily impacted by COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:773-775. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.032

- Kutlu Ö, Metin A. Relative changes in the pattern of diseases presenting in dermatology outpatient clinic in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14096. doi:10.1111/dth.14096

- Tanacan E, Aksoy Sarac G, Emeksiz MAC, et al. Changing trends in dermatology practice during COVID-19 pandemic: a single tertiary center experience. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14136. doi:10.1111/dth.14136

- Sharma A, Jindal V, Singla P, et al. Will teledermatology be the silver lining during and after COVID-19? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13643. doi:10.1111/dth.13643

- Iscrupe L. How to receive virtual medical treatment while under quarantine. Allconnect website. Published March 26, 2020. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.allconnect.com/blog/online-doctor-visit-faq

- Elgash M, Dlova N, Ogunleye T, et al. Seborrheic dermatitis in skin of color: clinical considerations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:24-27.

- McLaurin CI. Annular facial dermatoses in blacks. Cutis. 1983;32:369-370, 384.

- Suchonwanit P, Hector CE, Bin Saif GA, McMichael AJ. Factors affecting the severity of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e338-343. doi:10.1111/ijd.13061

- Gabros S, Masood S. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Updated July 20, 2021. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559187/

- Ross EK, Tan E, Shapiro J. Update on primary cicatricial alopecias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1-37. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.06.015

- Cobos G, Kim RH, Meehan S, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus and lichen planopilaris. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt7hp8n6dn.

- Lyakhovitsky A, Amichai B, Sizopoulou C, et al. A case series of 46 patients with lichen planopilaris: demographics, clinical evaluation, and treatment experience. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:275-279. doi:10.3109/09546634.2014.933165

- Tan E, Martinka M, Ball N, et al. Primary cicatricial alopecias: clinicopathology of 112 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:25-32. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.04.001

Practice Gap

In accordance with World Health Organization guidelines on social distancing to limit transmission of SARS-CoV-2, dermatologists have relied on teledermatology (TD) to develop novel adaptations of traditional workflows, optimize patient care, and limit in-person appointments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pandemic-induced physical and emotional stress were anticipated to increase the incidence of dermatologic diseases with psychologic triggers.

The connection between hair loss and emotional stress is well documented for telogen effluvium and alopecia areata.1,2 As anticipated, dermatology visits increased during the COVID-19 pandemic for the diagnosis of alopecia1-4; a survey performed during the pandemic found that alopecia was one of the most common diagnoses dermatologists made through telehealth platforms.5

This article provides a practical guide for dermatology practitioners to efficiently and accurately assess alopecia by TD in all patients, with added considerations for skin of color patients.

Diagnostic Tools

The intersection of TD, as an effective mechanism for the diagnosis and treatment of dermatologic disorders, and the increase in alopecia observed during the COVID-19 pandemic prompted us to develop a workflow for conducting virtual scalp examinations. Seven dermatologists (A.M., A.A., O.A., N.E., V.C., C.M.B., S.C.T.) who are experts in hair disorders contributed to developing workflows to optimize the assessment of alopecia through a virtual scalp examination, with an emphasis on patients of color. These experts completed a 7-question survey (Table) detailing their approach to the virtual scalp examination. One author (B.N.W.) served as an independent reviewer and collated responses into the following workflows.

Telemedicine Previsit Workflow

Components of the previsit workflow include:

• Instruct patients to provide all laboratory values and biopsy reports before the appointment.

• Test for a stable Wi-Fi connection using a speed test (available at https://www.speedtest.net/). A speed of 10 megabits/second or more is required for high-quality video via TD.6

• Provide a handout illustrating the required photographs of the anterior hairline; the mid scalp, including vertex, bilateral parietal, and occipital scalp; and posterior hairline. Photographs should be uploaded 2 hours before the visit. Figures 1 and 2 are examples of photographs that should be requested.

• Request images with 2 or 3 different angles of the area of the scalp with the greatest involvement to help appreciate primary and secondary characteristics.

• Encourage patients to present with clean, recently shampooed, dried, and detangled natural hair, unless they have an itchy or flaky scalp.

• For concerns of scalp, hairline, eyebrow, or facial flaking and scaling, instruct the patient to avoid applying a moisturizer before the visit.

• Instruct the patient to remove false eyelashes, eyelash extensions, eyebrow pencil, hair camouflage, hair accessories, braids, extensions, weaves, twists, and other hairstyles so that the hair can be maneuvered to expose the scalp surface.

• Instruct the patient to have a comb, pic, or brush, or more than one of these implements, available during the visit.

Telemedicine Visit Workflow

Components of the visit workflow include:

• If a stable Wi-Fi connection cannot be established, switch to an audio-only visit to collect a pertinent history. Advise the patient that in-person follow-up must be scheduled.

• Confirm that (1) the patient is in a private setting where the scalp can be viewed and (2) lighting is positioned in front of the patient.

• Ensure that the patient’s hairline, full face, eyebrows, and eyelashes and, upon request, the vertex and posterior scalp, are completely visible.

• Initiate the virtual scalp examination by instructing the patient how to perform a hair pull test. Then, examine the pattern and distribution of hair loss alongside supplemental photographs.

• Instruct the patient to apply pressure with the fingertips throughout the scalp to help localize tenderness, which, in combination with the pattern of hair loss observed, might inform the diagnosis.

• Instruct the patient to scan the scalp with the fingertips for “bumps” to locate papules, pustules, and keloidal scars.

Diagnostic Pearls

Distribution of Alopecia—The experts noted that the pattern, distribution, and location of hair loss determined from the telemedicine alopecia assessment provided important clues to distinguish the type of alopecia.

Diagnostic clues for diffuse or generalized alopecia include:

• Either of these findings might be indicative of telogen effluvium or acquired trichorrhexis nodosa. Results of the hair pull test can help distinguish between these diagnoses.

• Recent stressful life events along with the presence of telogen hairs extracted during a hair pull test support the diagnosis of telogen effluvium.

• A history of external stress on the hair—thermal, traction, or chemical—along with broken hair shafts following the hair pull test support the diagnosis of acquired trichorrhexis nodosa.

Diagnostic clues for focal or patchy alopecia include:

• Alopecia areata generally presents as focal hair loss in an annular distribution; pruritus, erythema, and scale are absent.

• Seborrheic dermatitis can present as pruritic erythematous patches with scale distributed on the scalp and, in some cases, in the eyebrows, nasolabial folds, or paranasal skin.7 Some skin of color patients present with petaloid seborrheic dermatitis—pink or hypopigmented polycyclic coalescing rings with minimal scale.7,8

• Discoid lupus erythematosus, similar to seborrheic dermatitis, might present as pruritic, scaly, hypopigmented patches. However, in the experience of the experts, a more common presentation is tender erythematous patches of hair loss with central hypopigmentation and surrounding hyperpigmentation.

Diagnostic clues for vertex and mid scalp alopecia include:

• Androgenetic alopecia typically presents as a reduction of terminal hair density in the vertex and mid scalp regions (with widening through the midline part) and fine hair along the anterior hairline.9 Signs of concomitant hyperandrogenism, including facial hirsutism, acne, and obesity, might be observed.10

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia typically affects the vertex and mid scalp with a shiny scalp appearance and follicular dropout.

Diagnostic clues for frontotemporal alopecia include:

• Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) often presents with spared single terminal hairs (lonely hair sign).

• Traction alopecia commonly presents with the fringe hair sign.

Scalp Symptoms—The experts noted that the presence of symptoms (eg, pain, tenderness, pruritus) in conjunction with the pattern of hair loss might support the diagnosis of an inflammatory scarring alopecia.

When do symptoms raise suspicion of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia?

• Suspected in the setting of vertex alopecia associated with tenderness, pain, or itching.

When do symptoms raise suspicion of FFA?

• Suspected when patients experience frontotemporal tenderness, pain, or burning associated with alopecia.

• The skin hue of the affected area might be lighter in color than, and contrast with, the darker hue of the photoaged upper forehead.11

• The lonely hair sign can aid in diagnosing FFA and distinguish it from the fringe sign of traction alopecia.

• Concurrent madarosis, flesh-colored papules on the cheeks, or lichen planus pigmentosus identified by visual inspection of the face confirms the diagnosis.9,12 Madarosis of the eyebrow was frequently cited by the experts as an associated symptom of FFA.

When do symptoms raise suspicion of lichen planopilaris?

• Suspected in the presence of pruritus, burning, tenderness, or pain associated with perifollicular erythema and scale in the setting of vertex and parietal alopecia.13

• Anagen hair release is observed during the hair pull test.11,14• The experts cited flesh-colored papules and lichen planus pigmentosus as frequently associated symptoms of lichen planopilaris.

Practice Implications

There are limitations to a virtual scalp examination—the inability to perform a scalp biopsy or administer certain treatments—but the consensus of the expert panel is that an initial alopecia assessment can be completed successfully utilizing TD. Although TD is not a replacement for an in-person dermatology visit, this technology has allowed for the diagnosis, treatment, and continuing care of many common dermatologic conditions without the patient needing to travel to the office.5

With the increased frequency of hair loss concerns documented over the last year and more patients seeking TD, it is imperative that dermatologists feel confident performing a virtual hair and scalp examination on all patients.1,3,4

Practice Gap

In accordance with World Health Organization guidelines on social distancing to limit transmission of SARS-CoV-2, dermatologists have relied on teledermatology (TD) to develop novel adaptations of traditional workflows, optimize patient care, and limit in-person appointments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pandemic-induced physical and emotional stress were anticipated to increase the incidence of dermatologic diseases with psychologic triggers.

The connection between hair loss and emotional stress is well documented for telogen effluvium and alopecia areata.1,2 As anticipated, dermatology visits increased during the COVID-19 pandemic for the diagnosis of alopecia1-4; a survey performed during the pandemic found that alopecia was one of the most common diagnoses dermatologists made through telehealth platforms.5

This article provides a practical guide for dermatology practitioners to efficiently and accurately assess alopecia by TD in all patients, with added considerations for skin of color patients.

Diagnostic Tools

The intersection of TD, as an effective mechanism for the diagnosis and treatment of dermatologic disorders, and the increase in alopecia observed during the COVID-19 pandemic prompted us to develop a workflow for conducting virtual scalp examinations. Seven dermatologists (A.M., A.A., O.A., N.E., V.C., C.M.B., S.C.T.) who are experts in hair disorders contributed to developing workflows to optimize the assessment of alopecia through a virtual scalp examination, with an emphasis on patients of color. These experts completed a 7-question survey (Table) detailing their approach to the virtual scalp examination. One author (B.N.W.) served as an independent reviewer and collated responses into the following workflows.

Telemedicine Previsit Workflow

Components of the previsit workflow include:

• Instruct patients to provide all laboratory values and biopsy reports before the appointment.

• Test for a stable Wi-Fi connection using a speed test (available at https://www.speedtest.net/). A speed of 10 megabits/second or more is required for high-quality video via TD.6

• Provide a handout illustrating the required photographs of the anterior hairline; the mid scalp, including vertex, bilateral parietal, and occipital scalp; and posterior hairline. Photographs should be uploaded 2 hours before the visit. Figures 1 and 2 are examples of photographs that should be requested.

• Request images with 2 or 3 different angles of the area of the scalp with the greatest involvement to help appreciate primary and secondary characteristics.

• Encourage patients to present with clean, recently shampooed, dried, and detangled natural hair, unless they have an itchy or flaky scalp.

• For concerns of scalp, hairline, eyebrow, or facial flaking and scaling, instruct the patient to avoid applying a moisturizer before the visit.

• Instruct the patient to remove false eyelashes, eyelash extensions, eyebrow pencil, hair camouflage, hair accessories, braids, extensions, weaves, twists, and other hairstyles so that the hair can be maneuvered to expose the scalp surface.

• Instruct the patient to have a comb, pic, or brush, or more than one of these implements, available during the visit.

Telemedicine Visit Workflow

Components of the visit workflow include:

• If a stable Wi-Fi connection cannot be established, switch to an audio-only visit to collect a pertinent history. Advise the patient that in-person follow-up must be scheduled.

• Confirm that (1) the patient is in a private setting where the scalp can be viewed and (2) lighting is positioned in front of the patient.

• Ensure that the patient’s hairline, full face, eyebrows, and eyelashes and, upon request, the vertex and posterior scalp, are completely visible.

• Initiate the virtual scalp examination by instructing the patient how to perform a hair pull test. Then, examine the pattern and distribution of hair loss alongside supplemental photographs.

• Instruct the patient to apply pressure with the fingertips throughout the scalp to help localize tenderness, which, in combination with the pattern of hair loss observed, might inform the diagnosis.

• Instruct the patient to scan the scalp with the fingertips for “bumps” to locate papules, pustules, and keloidal scars.

Diagnostic Pearls

Distribution of Alopecia—The experts noted that the pattern, distribution, and location of hair loss determined from the telemedicine alopecia assessment provided important clues to distinguish the type of alopecia.

Diagnostic clues for diffuse or generalized alopecia include:

• Either of these findings might be indicative of telogen effluvium or acquired trichorrhexis nodosa. Results of the hair pull test can help distinguish between these diagnoses.

• Recent stressful life events along with the presence of telogen hairs extracted during a hair pull test support the diagnosis of telogen effluvium.

• A history of external stress on the hair—thermal, traction, or chemical—along with broken hair shafts following the hair pull test support the diagnosis of acquired trichorrhexis nodosa.

Diagnostic clues for focal or patchy alopecia include:

• Alopecia areata generally presents as focal hair loss in an annular distribution; pruritus, erythema, and scale are absent.

• Seborrheic dermatitis can present as pruritic erythematous patches with scale distributed on the scalp and, in some cases, in the eyebrows, nasolabial folds, or paranasal skin.7 Some skin of color patients present with petaloid seborrheic dermatitis—pink or hypopigmented polycyclic coalescing rings with minimal scale.7,8

• Discoid lupus erythematosus, similar to seborrheic dermatitis, might present as pruritic, scaly, hypopigmented patches. However, in the experience of the experts, a more common presentation is tender erythematous patches of hair loss with central hypopigmentation and surrounding hyperpigmentation.

Diagnostic clues for vertex and mid scalp alopecia include:

• Androgenetic alopecia typically presents as a reduction of terminal hair density in the vertex and mid scalp regions (with widening through the midline part) and fine hair along the anterior hairline.9 Signs of concomitant hyperandrogenism, including facial hirsutism, acne, and obesity, might be observed.10

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia typically affects the vertex and mid scalp with a shiny scalp appearance and follicular dropout.

Diagnostic clues for frontotemporal alopecia include:

• Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) often presents with spared single terminal hairs (lonely hair sign).

• Traction alopecia commonly presents with the fringe hair sign.

Scalp Symptoms—The experts noted that the presence of symptoms (eg, pain, tenderness, pruritus) in conjunction with the pattern of hair loss might support the diagnosis of an inflammatory scarring alopecia.

When do symptoms raise suspicion of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia?

• Suspected in the setting of vertex alopecia associated with tenderness, pain, or itching.

When do symptoms raise suspicion of FFA?

• Suspected when patients experience frontotemporal tenderness, pain, or burning associated with alopecia.

• The skin hue of the affected area might be lighter in color than, and contrast with, the darker hue of the photoaged upper forehead.11

• The lonely hair sign can aid in diagnosing FFA and distinguish it from the fringe sign of traction alopecia.

• Concurrent madarosis, flesh-colored papules on the cheeks, or lichen planus pigmentosus identified by visual inspection of the face confirms the diagnosis.9,12 Madarosis of the eyebrow was frequently cited by the experts as an associated symptom of FFA.

When do symptoms raise suspicion of lichen planopilaris?

• Suspected in the presence of pruritus, burning, tenderness, or pain associated with perifollicular erythema and scale in the setting of vertex and parietal alopecia.13

• Anagen hair release is observed during the hair pull test.11,14• The experts cited flesh-colored papules and lichen planus pigmentosus as frequently associated symptoms of lichen planopilaris.

Practice Implications

There are limitations to a virtual scalp examination—the inability to perform a scalp biopsy or administer certain treatments—but the consensus of the expert panel is that an initial alopecia assessment can be completed successfully utilizing TD. Although TD is not a replacement for an in-person dermatology visit, this technology has allowed for the diagnosis, treatment, and continuing care of many common dermatologic conditions without the patient needing to travel to the office.5

With the increased frequency of hair loss concerns documented over the last year and more patients seeking TD, it is imperative that dermatologists feel confident performing a virtual hair and scalp examination on all patients.1,3,4

- Kutlu Ö, Aktas¸ H, I·mren IG, et al. Short-term stress-related increasing cases of alopecia areata during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;1. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1782820

- Cline A, Kazemi A, Moy J, et al. A surge in the incidence of telogen effluvium in minority predominant communities heavily impacted by COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:773-775. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.032

- Kutlu Ö, Metin A. Relative changes in the pattern of diseases presenting in dermatology outpatient clinic in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14096. doi:10.1111/dth.14096

- Tanacan E, Aksoy Sarac G, Emeksiz MAC, et al. Changing trends in dermatology practice during COVID-19 pandemic: a single tertiary center experience. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14136. doi:10.1111/dth.14136

- Sharma A, Jindal V, Singla P, et al. Will teledermatology be the silver lining during and after COVID-19? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13643. doi:10.1111/dth.13643

- Iscrupe L. How to receive virtual medical treatment while under quarantine. Allconnect website. Published March 26, 2020. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.allconnect.com/blog/online-doctor-visit-faq

- Elgash M, Dlova N, Ogunleye T, et al. Seborrheic dermatitis in skin of color: clinical considerations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:24-27.

- McLaurin CI. Annular facial dermatoses in blacks. Cutis. 1983;32:369-370, 384.

- Suchonwanit P, Hector CE, Bin Saif GA, McMichael AJ. Factors affecting the severity of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e338-343. doi:10.1111/ijd.13061

- Gabros S, Masood S. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Updated July 20, 2021. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559187/

- Ross EK, Tan E, Shapiro J. Update on primary cicatricial alopecias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1-37. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.06.015

- Cobos G, Kim RH, Meehan S, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus and lichen planopilaris. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt7hp8n6dn.

- Lyakhovitsky A, Amichai B, Sizopoulou C, et al. A case series of 46 patients with lichen planopilaris: demographics, clinical evaluation, and treatment experience. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:275-279. doi:10.3109/09546634.2014.933165

- Tan E, Martinka M, Ball N, et al. Primary cicatricial alopecias: clinicopathology of 112 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:25-32. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.04.001

- Kutlu Ö, Aktas¸ H, I·mren IG, et al. Short-term stress-related increasing cases of alopecia areata during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;1. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1782820

- Cline A, Kazemi A, Moy J, et al. A surge in the incidence of telogen effluvium in minority predominant communities heavily impacted by COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:773-775. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.032

- Kutlu Ö, Metin A. Relative changes in the pattern of diseases presenting in dermatology outpatient clinic in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14096. doi:10.1111/dth.14096

- Tanacan E, Aksoy Sarac G, Emeksiz MAC, et al. Changing trends in dermatology practice during COVID-19 pandemic: a single tertiary center experience. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14136. doi:10.1111/dth.14136

- Sharma A, Jindal V, Singla P, et al. Will teledermatology be the silver lining during and after COVID-19? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13643. doi:10.1111/dth.13643

- Iscrupe L. How to receive virtual medical treatment while under quarantine. Allconnect website. Published March 26, 2020. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.allconnect.com/blog/online-doctor-visit-faq

- Elgash M, Dlova N, Ogunleye T, et al. Seborrheic dermatitis in skin of color: clinical considerations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:24-27.

- McLaurin CI. Annular facial dermatoses in blacks. Cutis. 1983;32:369-370, 384.

- Suchonwanit P, Hector CE, Bin Saif GA, McMichael AJ. Factors affecting the severity of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e338-343. doi:10.1111/ijd.13061

- Gabros S, Masood S. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Updated July 20, 2021. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559187/

- Ross EK, Tan E, Shapiro J. Update on primary cicatricial alopecias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1-37. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.06.015

- Cobos G, Kim RH, Meehan S, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus and lichen planopilaris. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt7hp8n6dn.

- Lyakhovitsky A, Amichai B, Sizopoulou C, et al. A case series of 46 patients with lichen planopilaris: demographics, clinical evaluation, and treatment experience. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:275-279. doi:10.3109/09546634.2014.933165

- Tan E, Martinka M, Ball N, et al. Primary cicatricial alopecias: clinicopathology of 112 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:25-32. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.04.001

Pursuit of a Research Year or Dual Degree by Dermatology Residency Applicants: A Cross-Sectional Study

To the Editor:

Securing a dermatology residency position is extraordinarily competitive. The match rate for US allopathic seniors for dermatology is 84.7%, among the lowest of all medical specialties. Matched dermatology applicants boast a mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score of 248, the second highest of all specialties.1 To gain an edge, applicants are faced with decisions regarding pursuit of dedicated research time and additional professional degrees.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to determine how many dermatology residency applicants pursue additional years of training and how this decision relates to USMLE scores and other metrics. This study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board. Using Electronic Residency Application Service applicant data, all applicants to the University of Michigan Medical School (Ann Arbor, Michigan) dermatology residency program for the 2018-2019 application cycle were included.

Analysis of variance was performed to determine differences in mean USMLE Step 1 scores, Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores, and number of research experiences (eg, presentations, publications) between groups. A 2-tailed z test of independent samples was performed for individual pairwise subgroup analyses.

There were 608 (377 female, 231 male; mean age, 27.9 years) applicants from 199 different medical schools; 550 graduated with an MD degree, 40 with a DO degree, and 18 were international medical graduates (IMGs)(eg, MBBS, MBBCh, BAO, MBChB). One hundred eighty-four applicants (30.2%) pursued either a second professional degree or a dedicated research period lasting at least 12 months. Twenty-eight applicants (4.6%) obtained a master’s degree, 21 (3.5%) obtained a doctorate, and 135 (22.2%) pursued dedicated research.

Of the 40 DO applicants, 1 (2.5%) pursued dedicated research time; 0 (zero) completed a dual degree. None (zero) of the 18 IMGs pursued a dual degree or dedicated research time. When the scores of applicants who pursued additional training and the scores of applicants who did not were compared, neither mean USMLE Step 1 scores nor mean USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores were statistically different (P=.31 and P=.44, respectively). Applicants who completed medical school in 4 years had fewer research experiences (mean [SD] experiences, 13.9 [13.2]) than students with a master’s degree (18.5 [8.4]), doctorate (24.5 [17.5]), or dedicated research time (23.9 [14.9])(P<.001).

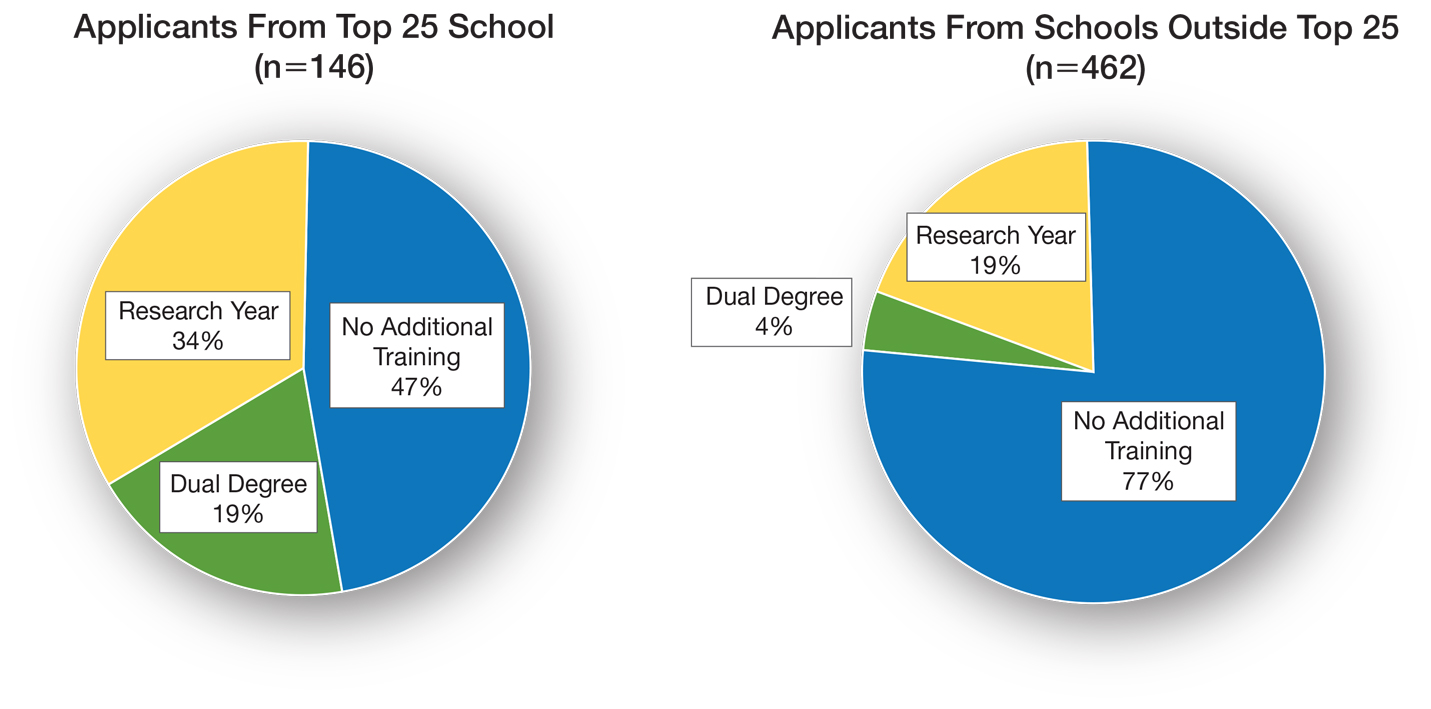

Utilizing US News & World Report rankings (2019 Best Medical Schools: Research), we determined that 146 applicants (24.0%) attended a top 25 medical school in 2019.2 Of those 146 applicants, 77 (52.7%) pursued additional training through dedicated research or a second professional degree. Only 107 of the 462 applicants (23.2%) from medical schools that were not in the top 25 as determined by the US News & World Report pursued additional training (P<.0001)(Figure).

There is sentiment among applicants that a weaker dermatology residency application can be bolstered through a dedicated research year or a second professional degree. Whether this additional training has an impact on an applicant’s chances of matching is unclear and requires further investigation. Our data showed that applicants from the top 25 medical schools were more likely to pursue additional training than graduates at other institutions. These highly ranked academic institutions might encourage students to pursue a dual degree or research fellowship. In addition, year-long research opportunities might be more available through top medical schools; these schools might be more likely to offer dual-degree programs or provide funding to support student research opportunities.

It is important to comment on the potential importance of funding to support research years; the unpaid nature of many research fellowships in dermatology tends to favor applicants from a higher socioeconomic background. In that respect, the pervasive trend of encouraging research years in dermatology might widen already apparent disparities in our field, likely impacting underrepresented minorities disproportionately.3 Importantly, students with an MD degree represent nearly all applicants who completed a dual degree or dedicated research time. This might be due to fewer opportunities available to IMGs and DO students or secondary to incentivization by MD institutions.

Our data also suggest that students who pursue additional training have academic achievement metrics similar to those who do not. Additional training might increase medical students’ debt burden, thus catering to more affluent applicants, which, in turn, might have an impact on the diversity of the dermatology residency applicant pool.

Our data come from a single institution during a single application cycle, comprising 608 applicants. Nationwide, there were 701 dermatology residency applicants for the 2018-2019 application cycle; our pool therefore represents most (86.7%) but not all applicants.

We decided to use the US News & World Report 2019 rankings to identify top medical schools. Although this ranking system is imperfect and inherently subjective, it is widely utilized by prospective applicants and administrative faculty; we deemed it the best ranking that we could utilize to identify top medical schools. Because the University of Michigan Medical School was in the top 25 of Best Medical Schools: Research, according to the US News & World Report 2019 rankings, our applicant pool might be skewed to applicants interested in a more academic, research-focused residency program.

Our study revealed that 30% (n=184) of dermatology residency applicants pursued a second professional degree or dedicated research time. There was no difference in UMLE Step 1 and Step 2 scores for those who pursued additional training compared to those who did not.

- Charting outcomes in the match: U.S. allopathic seniors. 2nd ed. National Residency Matching Program. Published July 2020. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2020_MD-Senior_final.pdf

- 2019 Best Medical Schools: Research. US News & World Report; 2019.

- Oussedik E. Important considerations for diversity in the selection of dermatology applicants. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:948-949. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1814

To the Editor:

Securing a dermatology residency position is extraordinarily competitive. The match rate for US allopathic seniors for dermatology is 84.7%, among the lowest of all medical specialties. Matched dermatology applicants boast a mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score of 248, the second highest of all specialties.1 To gain an edge, applicants are faced with decisions regarding pursuit of dedicated research time and additional professional degrees.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to determine how many dermatology residency applicants pursue additional years of training and how this decision relates to USMLE scores and other metrics. This study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board. Using Electronic Residency Application Service applicant data, all applicants to the University of Michigan Medical School (Ann Arbor, Michigan) dermatology residency program for the 2018-2019 application cycle were included.

Analysis of variance was performed to determine differences in mean USMLE Step 1 scores, Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores, and number of research experiences (eg, presentations, publications) between groups. A 2-tailed z test of independent samples was performed for individual pairwise subgroup analyses.

There were 608 (377 female, 231 male; mean age, 27.9 years) applicants from 199 different medical schools; 550 graduated with an MD degree, 40 with a DO degree, and 18 were international medical graduates (IMGs)(eg, MBBS, MBBCh, BAO, MBChB). One hundred eighty-four applicants (30.2%) pursued either a second professional degree or a dedicated research period lasting at least 12 months. Twenty-eight applicants (4.6%) obtained a master’s degree, 21 (3.5%) obtained a doctorate, and 135 (22.2%) pursued dedicated research.

Of the 40 DO applicants, 1 (2.5%) pursued dedicated research time; 0 (zero) completed a dual degree. None (zero) of the 18 IMGs pursued a dual degree or dedicated research time. When the scores of applicants who pursued additional training and the scores of applicants who did not were compared, neither mean USMLE Step 1 scores nor mean USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores were statistically different (P=.31 and P=.44, respectively). Applicants who completed medical school in 4 years had fewer research experiences (mean [SD] experiences, 13.9 [13.2]) than students with a master’s degree (18.5 [8.4]), doctorate (24.5 [17.5]), or dedicated research time (23.9 [14.9])(P<.001).

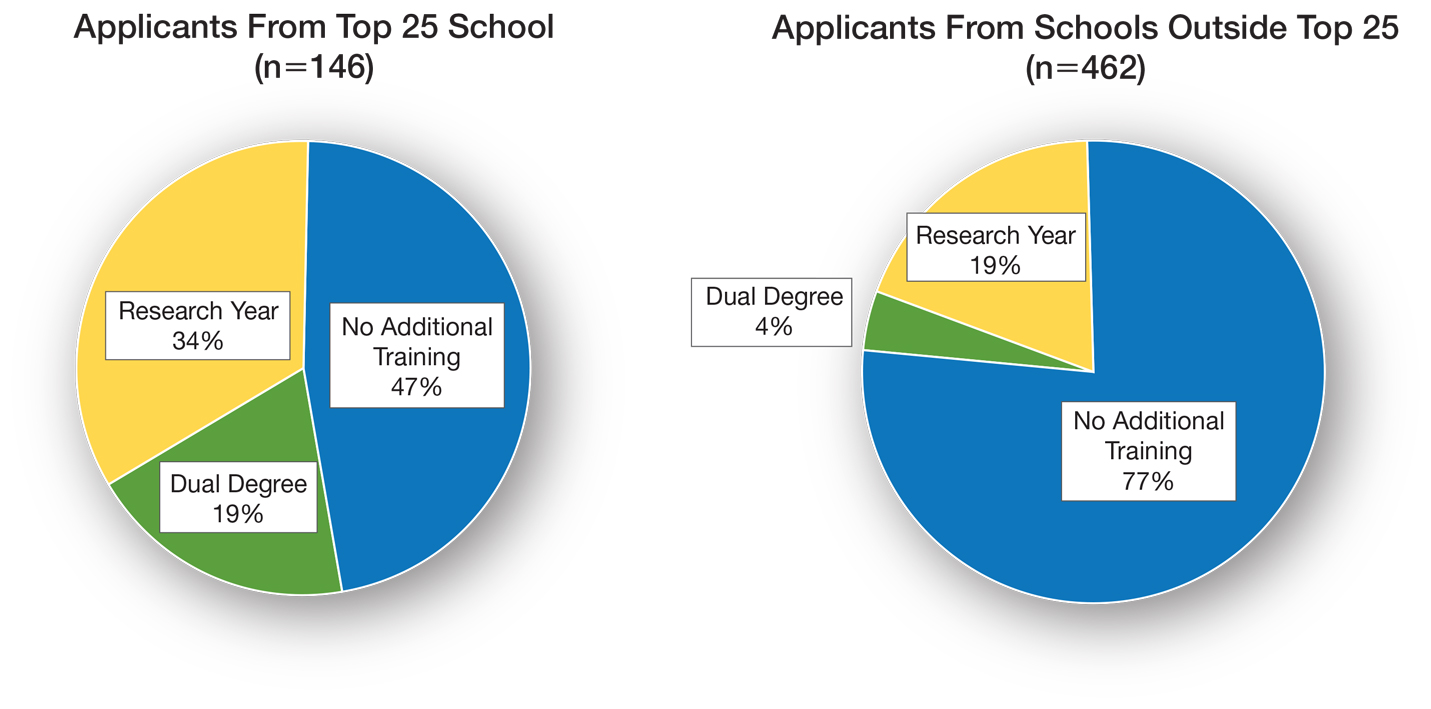

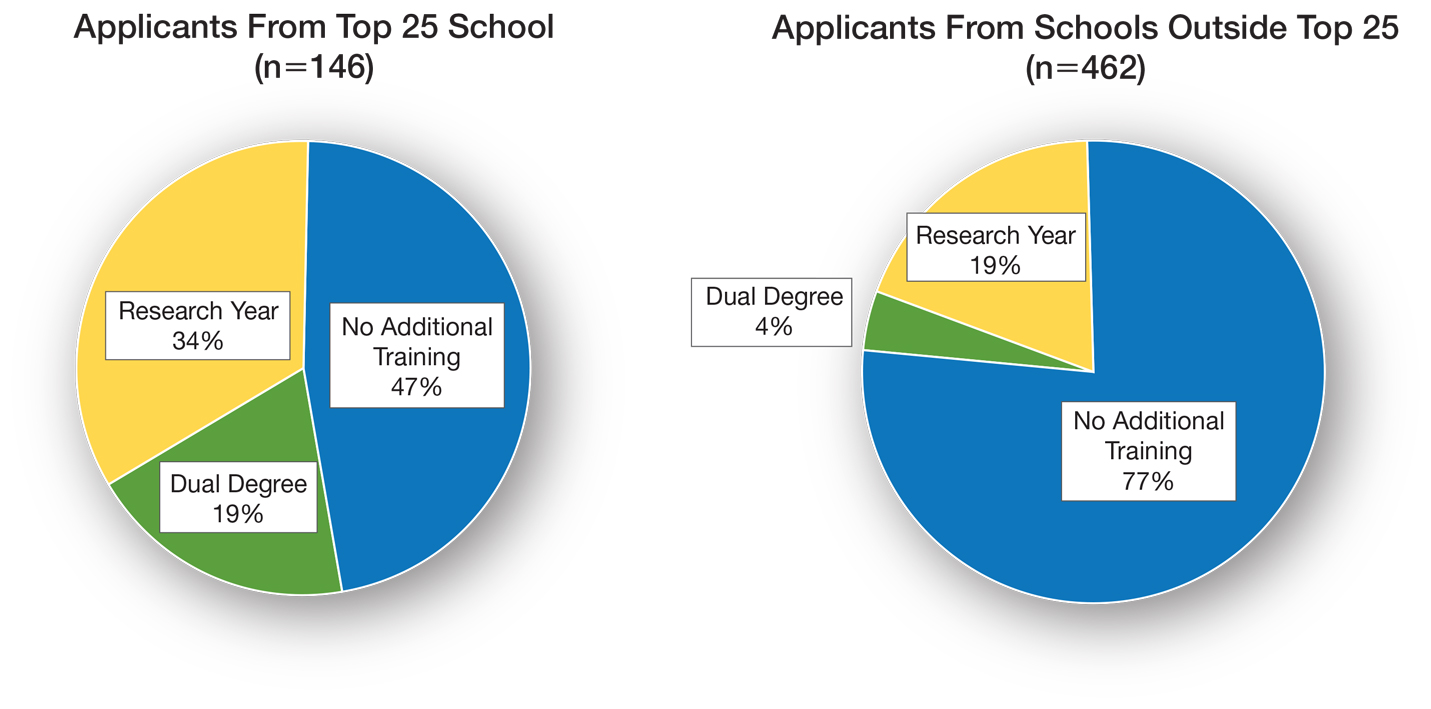

Utilizing US News & World Report rankings (2019 Best Medical Schools: Research), we determined that 146 applicants (24.0%) attended a top 25 medical school in 2019.2 Of those 146 applicants, 77 (52.7%) pursued additional training through dedicated research or a second professional degree. Only 107 of the 462 applicants (23.2%) from medical schools that were not in the top 25 as determined by the US News & World Report pursued additional training (P<.0001)(Figure).

There is sentiment among applicants that a weaker dermatology residency application can be bolstered through a dedicated research year or a second professional degree. Whether this additional training has an impact on an applicant’s chances of matching is unclear and requires further investigation. Our data showed that applicants from the top 25 medical schools were more likely to pursue additional training than graduates at other institutions. These highly ranked academic institutions might encourage students to pursue a dual degree or research fellowship. In addition, year-long research opportunities might be more available through top medical schools; these schools might be more likely to offer dual-degree programs or provide funding to support student research opportunities.

It is important to comment on the potential importance of funding to support research years; the unpaid nature of many research fellowships in dermatology tends to favor applicants from a higher socioeconomic background. In that respect, the pervasive trend of encouraging research years in dermatology might widen already apparent disparities in our field, likely impacting underrepresented minorities disproportionately.3 Importantly, students with an MD degree represent nearly all applicants who completed a dual degree or dedicated research time. This might be due to fewer opportunities available to IMGs and DO students or secondary to incentivization by MD institutions.

Our data also suggest that students who pursue additional training have academic achievement metrics similar to those who do not. Additional training might increase medical students’ debt burden, thus catering to more affluent applicants, which, in turn, might have an impact on the diversity of the dermatology residency applicant pool.

Our data come from a single institution during a single application cycle, comprising 608 applicants. Nationwide, there were 701 dermatology residency applicants for the 2018-2019 application cycle; our pool therefore represents most (86.7%) but not all applicants.

We decided to use the US News & World Report 2019 rankings to identify top medical schools. Although this ranking system is imperfect and inherently subjective, it is widely utilized by prospective applicants and administrative faculty; we deemed it the best ranking that we could utilize to identify top medical schools. Because the University of Michigan Medical School was in the top 25 of Best Medical Schools: Research, according to the US News & World Report 2019 rankings, our applicant pool might be skewed to applicants interested in a more academic, research-focused residency program.

Our study revealed that 30% (n=184) of dermatology residency applicants pursued a second professional degree or dedicated research time. There was no difference in UMLE Step 1 and Step 2 scores for those who pursued additional training compared to those who did not.

To the Editor:

Securing a dermatology residency position is extraordinarily competitive. The match rate for US allopathic seniors for dermatology is 84.7%, among the lowest of all medical specialties. Matched dermatology applicants boast a mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score of 248, the second highest of all specialties.1 To gain an edge, applicants are faced with decisions regarding pursuit of dedicated research time and additional professional degrees.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to determine how many dermatology residency applicants pursue additional years of training and how this decision relates to USMLE scores and other metrics. This study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board. Using Electronic Residency Application Service applicant data, all applicants to the University of Michigan Medical School (Ann Arbor, Michigan) dermatology residency program for the 2018-2019 application cycle were included.

Analysis of variance was performed to determine differences in mean USMLE Step 1 scores, Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores, and number of research experiences (eg, presentations, publications) between groups. A 2-tailed z test of independent samples was performed for individual pairwise subgroup analyses.

There were 608 (377 female, 231 male; mean age, 27.9 years) applicants from 199 different medical schools; 550 graduated with an MD degree, 40 with a DO degree, and 18 were international medical graduates (IMGs)(eg, MBBS, MBBCh, BAO, MBChB). One hundred eighty-four applicants (30.2%) pursued either a second professional degree or a dedicated research period lasting at least 12 months. Twenty-eight applicants (4.6%) obtained a master’s degree, 21 (3.5%) obtained a doctorate, and 135 (22.2%) pursued dedicated research.

Of the 40 DO applicants, 1 (2.5%) pursued dedicated research time; 0 (zero) completed a dual degree. None (zero) of the 18 IMGs pursued a dual degree or dedicated research time. When the scores of applicants who pursued additional training and the scores of applicants who did not were compared, neither mean USMLE Step 1 scores nor mean USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores were statistically different (P=.31 and P=.44, respectively). Applicants who completed medical school in 4 years had fewer research experiences (mean [SD] experiences, 13.9 [13.2]) than students with a master’s degree (18.5 [8.4]), doctorate (24.5 [17.5]), or dedicated research time (23.9 [14.9])(P<.001).

Utilizing US News & World Report rankings (2019 Best Medical Schools: Research), we determined that 146 applicants (24.0%) attended a top 25 medical school in 2019.2 Of those 146 applicants, 77 (52.7%) pursued additional training through dedicated research or a second professional degree. Only 107 of the 462 applicants (23.2%) from medical schools that were not in the top 25 as determined by the US News & World Report pursued additional training (P<.0001)(Figure).

There is sentiment among applicants that a weaker dermatology residency application can be bolstered through a dedicated research year or a second professional degree. Whether this additional training has an impact on an applicant’s chances of matching is unclear and requires further investigation. Our data showed that applicants from the top 25 medical schools were more likely to pursue additional training than graduates at other institutions. These highly ranked academic institutions might encourage students to pursue a dual degree or research fellowship. In addition, year-long research opportunities might be more available through top medical schools; these schools might be more likely to offer dual-degree programs or provide funding to support student research opportunities.

It is important to comment on the potential importance of funding to support research years; the unpaid nature of many research fellowships in dermatology tends to favor applicants from a higher socioeconomic background. In that respect, the pervasive trend of encouraging research years in dermatology might widen already apparent disparities in our field, likely impacting underrepresented minorities disproportionately.3 Importantly, students with an MD degree represent nearly all applicants who completed a dual degree or dedicated research time. This might be due to fewer opportunities available to IMGs and DO students or secondary to incentivization by MD institutions.

Our data also suggest that students who pursue additional training have academic achievement metrics similar to those who do not. Additional training might increase medical students’ debt burden, thus catering to more affluent applicants, which, in turn, might have an impact on the diversity of the dermatology residency applicant pool.

Our data come from a single institution during a single application cycle, comprising 608 applicants. Nationwide, there were 701 dermatology residency applicants for the 2018-2019 application cycle; our pool therefore represents most (86.7%) but not all applicants.

We decided to use the US News & World Report 2019 rankings to identify top medical schools. Although this ranking system is imperfect and inherently subjective, it is widely utilized by prospective applicants and administrative faculty; we deemed it the best ranking that we could utilize to identify top medical schools. Because the University of Michigan Medical School was in the top 25 of Best Medical Schools: Research, according to the US News & World Report 2019 rankings, our applicant pool might be skewed to applicants interested in a more academic, research-focused residency program.

Our study revealed that 30% (n=184) of dermatology residency applicants pursued a second professional degree or dedicated research time. There was no difference in UMLE Step 1 and Step 2 scores for those who pursued additional training compared to those who did not.

- Charting outcomes in the match: U.S. allopathic seniors. 2nd ed. National Residency Matching Program. Published July 2020. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2020_MD-Senior_final.pdf

- 2019 Best Medical Schools: Research. US News & World Report; 2019.

- Oussedik E. Important considerations for diversity in the selection of dermatology applicants. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:948-949. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1814

- Charting outcomes in the match: U.S. allopathic seniors. 2nd ed. National Residency Matching Program. Published July 2020. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2020_MD-Senior_final.pdf

- 2019 Best Medical Schools: Research. US News & World Report; 2019.

- Oussedik E. Important considerations for diversity in the selection of dermatology applicants. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:948-949. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1814

PRACTICE POINTS

- In our study of dermatology residency applicants (N11=608), 30% pursued a second professional degree or dedicated research time.

- US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 and Step 2 scores did not differ among applicants who pursued additional training and those who did not.

- Additional training might increase medical students’ debt burden, thus catering to more affluent applicants and reducing the diversity of applicant and resident pools.

Medicaid implements waivers for some clinical trial coverage

Federal officials will allow some flexibility in meeting new requirements on covering the costs of clinical trials for people enrolled in Medicaid, seeking to accommodate states where legislatures will not meet in time to make needed changes in rules.

Congress in 2020 ordered U.S. states to have their Medicaid programs cover expenses related to participation in certain clinical trials, a move that was hailed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and other groups as a boost to trials as well as to patients with serious illness who have lower incomes.

The mandate went into effect on Jan. 1, but the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will allow accommodations in terms of implementation time for states that have not yet been able to make needed legislative changes, Daniel Tsai, deputy administrator and director of the Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, wrote in a Dec. 7 letter. Mr. Tsai’s letter doesn’t mention specific states. The CMS did not immediately respond to a request seeking information on the states expected to apply for waivers.

Medicaid has in recent years been a rare large U.S. insurance program that does not cover the costs of clinical trials. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandated this coverage for people in private insurance plans. The federal government in 2000 decided that Medicare would do so.

‘A hidden opportunity’

A perspective article last May in the New England Journal of Medicine referred to the new Medicaid mandate on clinical trials as a “hidden opportunity,” referring to its genesis as an add-on in a massive federal spending package enacted in December 2020.

In the article, Samuel U. Takvorian, MD, MSHP, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and coauthors noted that rates of participation in clinical trials remain low for racial and ethnic minority groups, due in part to the lack of Medicaid coverage.

“For example, non-Hispanic White patients are nearly twice as likely as Black patients and three times as likely as Hispanic patients to enroll in cancer clinical trials – a gap that has widened over time,” Dr. Takvorian and coauthors wrote. “Inequities in enrollment have also manifested during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected non-White patients, without their commensurate representation in trials of COVID-19 therapeutics.”

In October, researchers from the Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Ohio State University, Columbus, published results of a retrospective study of patients with stage I-IV pancreatic cancer that also found inequities in enrollment. Mariam F. Eskander, MD, MPH, and coauthors reported what they found by examining records for 1,127 patients (0.4%) enrolled in clinical trials and 301,340 (99.6%) who did not enroll. They found that enrollment in trials increased over the study period, but not for Black patients or patients on Medicaid.

In an interview, Dr. Eskander said the new Medicaid policy will remove a major obstacle to participation in clinical trials. An oncologist, Dr. Eskander said she is looking forward to being able to help more of her patients get access to experimental medicines and treatments.

But that may not be enough to draw more people with low incomes into these studies, said Dr. Eskander, who is now at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey in New Brunswick. She urges greater use of patient navigators to help people on Medicaid understand the resources available to them, as well as broad use of Medicaid’s nonemergency medical transportation (NEMT) benefit.

“Some patients will be offered clinical trial enrollment and some will accept, but I really worry about the challenges low-income people face with things like transportation and getting time off work,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal officials will allow some flexibility in meeting new requirements on covering the costs of clinical trials for people enrolled in Medicaid, seeking to accommodate states where legislatures will not meet in time to make needed changes in rules.

Congress in 2020 ordered U.S. states to have their Medicaid programs cover expenses related to participation in certain clinical trials, a move that was hailed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and other groups as a boost to trials as well as to patients with serious illness who have lower incomes.

The mandate went into effect on Jan. 1, but the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will allow accommodations in terms of implementation time for states that have not yet been able to make needed legislative changes, Daniel Tsai, deputy administrator and director of the Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, wrote in a Dec. 7 letter. Mr. Tsai’s letter doesn’t mention specific states. The CMS did not immediately respond to a request seeking information on the states expected to apply for waivers.

Medicaid has in recent years been a rare large U.S. insurance program that does not cover the costs of clinical trials. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandated this coverage for people in private insurance plans. The federal government in 2000 decided that Medicare would do so.

‘A hidden opportunity’

A perspective article last May in the New England Journal of Medicine referred to the new Medicaid mandate on clinical trials as a “hidden opportunity,” referring to its genesis as an add-on in a massive federal spending package enacted in December 2020.

In the article, Samuel U. Takvorian, MD, MSHP, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and coauthors noted that rates of participation in clinical trials remain low for racial and ethnic minority groups, due in part to the lack of Medicaid coverage.

“For example, non-Hispanic White patients are nearly twice as likely as Black patients and three times as likely as Hispanic patients to enroll in cancer clinical trials – a gap that has widened over time,” Dr. Takvorian and coauthors wrote. “Inequities in enrollment have also manifested during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected non-White patients, without their commensurate representation in trials of COVID-19 therapeutics.”

In October, researchers from the Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Ohio State University, Columbus, published results of a retrospective study of patients with stage I-IV pancreatic cancer that also found inequities in enrollment. Mariam F. Eskander, MD, MPH, and coauthors reported what they found by examining records for 1,127 patients (0.4%) enrolled in clinical trials and 301,340 (99.6%) who did not enroll. They found that enrollment in trials increased over the study period, but not for Black patients or patients on Medicaid.

In an interview, Dr. Eskander said the new Medicaid policy will remove a major obstacle to participation in clinical trials. An oncologist, Dr. Eskander said she is looking forward to being able to help more of her patients get access to experimental medicines and treatments.

But that may not be enough to draw more people with low incomes into these studies, said Dr. Eskander, who is now at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey in New Brunswick. She urges greater use of patient navigators to help people on Medicaid understand the resources available to them, as well as broad use of Medicaid’s nonemergency medical transportation (NEMT) benefit.

“Some patients will be offered clinical trial enrollment and some will accept, but I really worry about the challenges low-income people face with things like transportation and getting time off work,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal officials will allow some flexibility in meeting new requirements on covering the costs of clinical trials for people enrolled in Medicaid, seeking to accommodate states where legislatures will not meet in time to make needed changes in rules.

Congress in 2020 ordered U.S. states to have their Medicaid programs cover expenses related to participation in certain clinical trials, a move that was hailed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and other groups as a boost to trials as well as to patients with serious illness who have lower incomes.

The mandate went into effect on Jan. 1, but the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will allow accommodations in terms of implementation time for states that have not yet been able to make needed legislative changes, Daniel Tsai, deputy administrator and director of the Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, wrote in a Dec. 7 letter. Mr. Tsai’s letter doesn’t mention specific states. The CMS did not immediately respond to a request seeking information on the states expected to apply for waivers.

Medicaid has in recent years been a rare large U.S. insurance program that does not cover the costs of clinical trials. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandated this coverage for people in private insurance plans. The federal government in 2000 decided that Medicare would do so.

‘A hidden opportunity’

A perspective article last May in the New England Journal of Medicine referred to the new Medicaid mandate on clinical trials as a “hidden opportunity,” referring to its genesis as an add-on in a massive federal spending package enacted in December 2020.

In the article, Samuel U. Takvorian, MD, MSHP, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and coauthors noted that rates of participation in clinical trials remain low for racial and ethnic minority groups, due in part to the lack of Medicaid coverage.

“For example, non-Hispanic White patients are nearly twice as likely as Black patients and three times as likely as Hispanic patients to enroll in cancer clinical trials – a gap that has widened over time,” Dr. Takvorian and coauthors wrote. “Inequities in enrollment have also manifested during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected non-White patients, without their commensurate representation in trials of COVID-19 therapeutics.”

In October, researchers from the Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Ohio State University, Columbus, published results of a retrospective study of patients with stage I-IV pancreatic cancer that also found inequities in enrollment. Mariam F. Eskander, MD, MPH, and coauthors reported what they found by examining records for 1,127 patients (0.4%) enrolled in clinical trials and 301,340 (99.6%) who did not enroll. They found that enrollment in trials increased over the study period, but not for Black patients or patients on Medicaid.

In an interview, Dr. Eskander said the new Medicaid policy will remove a major obstacle to participation in clinical trials. An oncologist, Dr. Eskander said she is looking forward to being able to help more of her patients get access to experimental medicines and treatments.

But that may not be enough to draw more people with low incomes into these studies, said Dr. Eskander, who is now at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey in New Brunswick. She urges greater use of patient navigators to help people on Medicaid understand the resources available to them, as well as broad use of Medicaid’s nonemergency medical transportation (NEMT) benefit.

“Some patients will be offered clinical trial enrollment and some will accept, but I really worry about the challenges low-income people face with things like transportation and getting time off work,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Study finds more adverse maternal outcomes in women with disabilities

Women with physical, intellectual, and sensory disabilities had higher risk for almost all pregnancy complications, obstetric interventions, and adverse outcomes, including severe maternal morbidity (SMM) and mortality compared to women without disabilities, according to an analysis of a large, retrospective cohort.

The findings, published in JAMA Network Open (2021;4[12]:e2138414 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.38414), “may be a direct reflection of the challenges women with all types of disabilities face when accessing and receiving care, which is likely compounded by poorer preconception health,” suggested lead author Jessica L. Gleason, PhD, MPH, and co-authors, all from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

“Women with disabilities have long been ignored in obstetric research and clinical practice,” added Hilary K. Brown, PhD, from the University of Toronto, in an accompanying editorial. “Inclusion of disability indicators needs to be the norm – not the exception – in health administrative data so that these disparities can be regularly tracked and addressed.”

The investigators used data from the Consortium on Safe Labor (CSL), a retrospective cohort of deliveries from 12 U.S. clinical centers between Jan. 2002 and Jan. 2008, to analyze obstetric interventions and adverse maternal outcomes in women with and without disabilities.

The analysis included a total of 223,385 women, mean age 27.6 years, of whom 2,074 (0.9%) had a disability, and 221,311 did not. Among those with disabilities, 1,733 (83.5%) were physical, 91 (4.4%) were intellectual, and 250 (12.1%) were sensory. While almost half (49.4%) of the women were White, 22.5% were Black, 17.5% were Hispanic, and 4.1% were Asian or Pacific Islander.

Outcomes were analyzed with three composite measures:

- Pregnancy-related complications (pregnancy-related hypertensive diseases, gestational diabetes, placental abruption, placenta previa, premature rupture of membranes, preterm PROM);

- All labor, delivery, and postpartum complications (chorioamnionitis, hemorrhage, blood transfusion, thromboembolism, postpartum fever, infection, cardiovascular events, cardiomyopathy, and maternal death);

- SMM only, including severe pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, hemorrhage, thromboembolism, fever, infection, cardiomyopathy, and cardiovascular events during labor and delivery.

After adjustment for covariates, women with disabilities had higher risk of pregnancy-related complications. This included a 48% higher risk of mild pre-eclampsia and double the risk of severe pre-eclampsia/eclampsia. The composite risk of any pregnancy complication was 27% higher for women with physical disabilities, 49% higher for women with intellectual disabilities, and 53% higher for women with sensory disabilities.

The findings were similar for labor, delivery, and postpartum complications, showing women with disabilities had higher risk for a range of obstetrical interventions, including cesarean delivery – both planned and intrapartum (aRR, 1.34). Additionally, women with disabilities were less likely to have a cesarean delivery that was “solely clinically indicated” (aRR, 0.79), and more likely to have a cesarean delivery for “softer” mixed indication (aRR, 1.16), “supporting a possible overuse of cesarean delivery among women with disability,” they suggested.

Women with disabilities also had a higher risk of postpartum hemorrhage (aRR, 1.27), blood transfusion (aRR, 1.64), and maternal mortality (aRR, 11.19), as well as individual markers of severe maternal morbidity, such as cardiovascular events (aRR, 4.02), infection (aRR, 2.69), and venous thromboembolism (aRR, 6.08).

The authors speculate that the increased risks for women with disabilities “may be the result of a combination of independent risk factors, including the higher rate of obstetric intervention via cesarean delivery, under-recognition of women with disabilities as a population with higher-risk pregnancies, and lack of health care practitioner knowledge or comfort in managing pregnancies among women with disabilities.”

Dr. Brown noted in her commentary that there is a need for better education of health care professionals in this area. “Given that 12% of reproductive-aged women have a disability, that pregnancy rates are similar among women with and without disabilities, and that women with disabilities are at elevated risk of a range of adverse maternal outcomes, including severe maternal morbidity and maternal mortality, disability modules should be a mandatory component of education for obstetricians and midwives as well as other obstetrical health care professionals.”

Calling the study “a serious wake-up call,” Monika Mitra, PhD, told this publication that the findings highlight the need for “urgent attention” on improving obstetric care for people with disabilities “with a focus on accessibility and inclusion, changing clinical practice to better serve disabled people, integrating disability-related training for health care practitioners, and developing evidence-based interventions to support people with disabilities during this time.” The associate professor and director of the Lurie Institute for Disability Policy, in Brandeis University, Waltham, Mass. said the risk factors for poor outcomes are present early in pregnancy or even preconception. “We know that disabled women report barriers in accessing health care and receive lower-quality care compared to nondisabled women and are more likely to experience poverty, housing and food insecurity, educational and employment barriers, abuse, chronic health conditions, and mental illness than women without disabilities.”

She noted that the study’s sample of people with disabilities was small, and the measure of disability used was based on ICD-9 codes, which captures only severe disabilities. “As noted in the commentary by [Dr.] Brown, our standard sources of health administrative data do not give us the full picture on disability, and we need other, more equitable ways of identifying disability based, for example, on self-reports of activity or participation limitations if we are to be able to understand the effects on obstetric outcomes of health and health care disparities and of social determinants of health. Moreover, researchers have generally not yet begun to incorporate knowledge of the experiences of transgender people during pregnancy, which will impact our measures and study of obstetric outcomes among people with disabilities as well as the language we use.”

The study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The study authors and Dr. Brown reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Mitra receives funding from the NICHD and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living for research on pregnancy outcomes among people with disabilities.

Women with physical, intellectual, and sensory disabilities had higher risk for almost all pregnancy complications, obstetric interventions, and adverse outcomes, including severe maternal morbidity (SMM) and mortality compared to women without disabilities, according to an analysis of a large, retrospective cohort.

The findings, published in JAMA Network Open (2021;4[12]:e2138414 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.38414), “may be a direct reflection of the challenges women with all types of disabilities face when accessing and receiving care, which is likely compounded by poorer preconception health,” suggested lead author Jessica L. Gleason, PhD, MPH, and co-authors, all from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

“Women with disabilities have long been ignored in obstetric research and clinical practice,” added Hilary K. Brown, PhD, from the University of Toronto, in an accompanying editorial. “Inclusion of disability indicators needs to be the norm – not the exception – in health administrative data so that these disparities can be regularly tracked and addressed.”

The investigators used data from the Consortium on Safe Labor (CSL), a retrospective cohort of deliveries from 12 U.S. clinical centers between Jan. 2002 and Jan. 2008, to analyze obstetric interventions and adverse maternal outcomes in women with and without disabilities.

The analysis included a total of 223,385 women, mean age 27.6 years, of whom 2,074 (0.9%) had a disability, and 221,311 did not. Among those with disabilities, 1,733 (83.5%) were physical, 91 (4.4%) were intellectual, and 250 (12.1%) were sensory. While almost half (49.4%) of the women were White, 22.5% were Black, 17.5% were Hispanic, and 4.1% were Asian or Pacific Islander.

Outcomes were analyzed with three composite measures:

- Pregnancy-related complications (pregnancy-related hypertensive diseases, gestational diabetes, placental abruption, placenta previa, premature rupture of membranes, preterm PROM);

- All labor, delivery, and postpartum complications (chorioamnionitis, hemorrhage, blood transfusion, thromboembolism, postpartum fever, infection, cardiovascular events, cardiomyopathy, and maternal death);

- SMM only, including severe pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, hemorrhage, thromboembolism, fever, infection, cardiomyopathy, and cardiovascular events during labor and delivery.

After adjustment for covariates, women with disabilities had higher risk of pregnancy-related complications. This included a 48% higher risk of mild pre-eclampsia and double the risk of severe pre-eclampsia/eclampsia. The composite risk of any pregnancy complication was 27% higher for women with physical disabilities, 49% higher for women with intellectual disabilities, and 53% higher for women with sensory disabilities.

The findings were similar for labor, delivery, and postpartum complications, showing women with disabilities had higher risk for a range of obstetrical interventions, including cesarean delivery – both planned and intrapartum (aRR, 1.34). Additionally, women with disabilities were less likely to have a cesarean delivery that was “solely clinically indicated” (aRR, 0.79), and more likely to have a cesarean delivery for “softer” mixed indication (aRR, 1.16), “supporting a possible overuse of cesarean delivery among women with disability,” they suggested.

Women with disabilities also had a higher risk of postpartum hemorrhage (aRR, 1.27), blood transfusion (aRR, 1.64), and maternal mortality (aRR, 11.19), as well as individual markers of severe maternal morbidity, such as cardiovascular events (aRR, 4.02), infection (aRR, 2.69), and venous thromboembolism (aRR, 6.08).

The authors speculate that the increased risks for women with disabilities “may be the result of a combination of independent risk factors, including the higher rate of obstetric intervention via cesarean delivery, under-recognition of women with disabilities as a population with higher-risk pregnancies, and lack of health care practitioner knowledge or comfort in managing pregnancies among women with disabilities.”

Dr. Brown noted in her commentary that there is a need for better education of health care professionals in this area. “Given that 12% of reproductive-aged women have a disability, that pregnancy rates are similar among women with and without disabilities, and that women with disabilities are at elevated risk of a range of adverse maternal outcomes, including severe maternal morbidity and maternal mortality, disability modules should be a mandatory component of education for obstetricians and midwives as well as other obstetrical health care professionals.”

Calling the study “a serious wake-up call,” Monika Mitra, PhD, told this publication that the findings highlight the need for “urgent attention” on improving obstetric care for people with disabilities “with a focus on accessibility and inclusion, changing clinical practice to better serve disabled people, integrating disability-related training for health care practitioners, and developing evidence-based interventions to support people with disabilities during this time.” The associate professor and director of the Lurie Institute for Disability Policy, in Brandeis University, Waltham, Mass. said the risk factors for poor outcomes are present early in pregnancy or even preconception. “We know that disabled women report barriers in accessing health care and receive lower-quality care compared to nondisabled women and are more likely to experience poverty, housing and food insecurity, educational and employment barriers, abuse, chronic health conditions, and mental illness than women without disabilities.”