User login

What can be new about developmental milestones?

The American Academy of Pediatrics, with funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, studied the CDC’s “Learn the Signs. Act Early” developmental surveillance milestones for children 0-5 years to update the milestones based on published studies. The goal was to improve this tool for developmental surveillance and use by the public. Developmental surveillance is not just observing a child at a check-up but rather “is a longitudinal process that involves eliciting concerns, taking a developmental history based on milestone attainment, observing milestones and other behaviors, examining the child, and applying clinical judgment during health supervision visits (HSVs).”1

While the milestones we were trained on were a good start and highlighted the developmental progression central to pediatrics, they were not based on norms or cut scores indicating significant developmental risk unless taught from a validated tool. The CDC was concerned that their public handouts and apps were based on median ages (middle number of the entire range) of attainment not the mode (most common) or even average ages. That means that about half of all typically developing children would “not have attained” that skill at the age noted, potentially evoking unnecessary concern for parents and a “wait-and-see” message from a knowledgeable provider who realized the statistical meaning and the broad range of normal. Another potential problem with using milestones set at the median age is that parents, especially those with several children or experienced friends, may see the provider as an alarmist when they have seen great variation in children who later were normal. This reaction can dampen provider willingness to discuss development or even to screen with validated tools. We have learned the hard way from COVID-19 that it is difficult to convey concepts of risk effectively both balancing fear and stimulating action.

The AAP experts reviewed the English literature for data-based milestones, finding 34 articles, 10 of which had an opinion for at least one milestone. If this sounds like a very small number, you are correct. You may not realize that almost all screening and diagnostic tools have been based on data collected by Gesell in 1928!2 While most of health care has changed since then, which milestones are measured in infants has not.

The biggest change from this review was deciding to use as milestones skills reported for 75% of children at each age of typical HSVs, adding ones for 15 and 30 months. The implication is that children not attaining these milestones are all at risk and deserving of more careful history, examination, and administration of a validated screening tool; not true when based on median data. Of the 94 existing CDC milestones retained after the review, one-third were moved to a different age with 21 of 31 assigned to an older age. Domains of functioning for the milestones were consolidated into social emotional, cognitive, language/communication, and motor, to help parents learn to distinguish these areas, and, although many milestones reflect several domains, each was included only once to reduce confusion.

Psychosocial assessment is recommended by the AAP and Bright Futures at every HSV but the fewest milestones with normative data were identified for this domain, often self-help rather than social engagement or emotion regulation skills. The cross-cultural study cited for many of the new milestones was reassuring overall in that the median ages for 67%-88% of milestones in most domains were equivalent across the four countries sampled, but only 22% of self-help skills were equivalent.3 This should remind us that parenting has more influence over psychosocial skills than other domains. Psychosocial and behavioral functioning, especially emotional regulation, also deserve “surveillance” as they have enormous impact on life outcomes but need to be measured and supported differently. Routine use of validated tools such as the Early Childhood Screening Assessment or the Ages & Stages Questionnaires: Social-Emotional for these domains are also needed.

Normal variations in temperament and patterns of attachment can affect many milestones including courage for walking, exploration, social engagement, and prosocial behaviors or self-control for social situations, attention, range of affect, and cooperation. All of these skills are among the 42 total (14 new) social-emotional milestones for 0- to 5-year-olds. Variations in these functions are at the root of the most common “challenging behaviors” in our studies in primary care. They are also the most vulnerable to suboptimal parent-child relationships, adverse childhood experiences, and social determinants of health.

As primary care providers, we not only need to detect children at risk for developmental problems but also promote and celebrate developmental progress. I hope that changing the threshold for concern to 75% will allow for a more positive review with the family (as fewer will be flagged as at risk) and chance to congratulate parents on all that is going well. But I also hope the change will not make us overlook parenting challenges, often from the psychosocial milestones most amenable to our guidance and support.

Early identification is mainly important to obtain the early intervention shown to improve outcomes. However, less than 25% of children with delays or disabilities receive early intervention before age 3 and most with emotional, behavioral, and developmental conditions, other than autism spectrum disorder, not before age 5. Since early intervention services are freely available in all states, we also need to do better at getting children to this care.

Let’s reconsider the process of developmental surveillance in this light of delayed referral: “Eliciting concerns” is key as parents have been shown to be usually correct in their worries. Listening to how they express the concerns can help you connect their specific issues when discussing reasons for referral. While most parent “recall of past milestones” is not accurate, current milestones reported are; thus, the need to have the new more accurate norms for all ages for comparison. When we make observations of a child’s abilities and behaviors ourselves we may not only pick up on issues missed by the parent, but will be more convincing in conveying the need for referral when indicated. When we “examine” the child we can use our professional skills to determine the very important risk factor of the quality of how a skill is performed, not just that it is. The recommended “use of validated screening tools” when the new milestones are not met give us an objective tool to share with parents, more confidence in when referral is warranted, which we will convey to parents (and perhaps skeptical relatives), and baseline documentation from which we can “track” referrals, progress, and, hopefully, better outcomes.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Zubler JM et al. Pediatrics. 2022;149(3):e2021052138.

2. Gessell A et al. Macmillan: New York, 1928.

3. Ertem IO et al. Lancet Glob Health. 2018 Mar;6(3):e279-91.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, with funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, studied the CDC’s “Learn the Signs. Act Early” developmental surveillance milestones for children 0-5 years to update the milestones based on published studies. The goal was to improve this tool for developmental surveillance and use by the public. Developmental surveillance is not just observing a child at a check-up but rather “is a longitudinal process that involves eliciting concerns, taking a developmental history based on milestone attainment, observing milestones and other behaviors, examining the child, and applying clinical judgment during health supervision visits (HSVs).”1

While the milestones we were trained on were a good start and highlighted the developmental progression central to pediatrics, they were not based on norms or cut scores indicating significant developmental risk unless taught from a validated tool. The CDC was concerned that their public handouts and apps were based on median ages (middle number of the entire range) of attainment not the mode (most common) or even average ages. That means that about half of all typically developing children would “not have attained” that skill at the age noted, potentially evoking unnecessary concern for parents and a “wait-and-see” message from a knowledgeable provider who realized the statistical meaning and the broad range of normal. Another potential problem with using milestones set at the median age is that parents, especially those with several children or experienced friends, may see the provider as an alarmist when they have seen great variation in children who later were normal. This reaction can dampen provider willingness to discuss development or even to screen with validated tools. We have learned the hard way from COVID-19 that it is difficult to convey concepts of risk effectively both balancing fear and stimulating action.

The AAP experts reviewed the English literature for data-based milestones, finding 34 articles, 10 of which had an opinion for at least one milestone. If this sounds like a very small number, you are correct. You may not realize that almost all screening and diagnostic tools have been based on data collected by Gesell in 1928!2 While most of health care has changed since then, which milestones are measured in infants has not.

The biggest change from this review was deciding to use as milestones skills reported for 75% of children at each age of typical HSVs, adding ones for 15 and 30 months. The implication is that children not attaining these milestones are all at risk and deserving of more careful history, examination, and administration of a validated screening tool; not true when based on median data. Of the 94 existing CDC milestones retained after the review, one-third were moved to a different age with 21 of 31 assigned to an older age. Domains of functioning for the milestones were consolidated into social emotional, cognitive, language/communication, and motor, to help parents learn to distinguish these areas, and, although many milestones reflect several domains, each was included only once to reduce confusion.

Psychosocial assessment is recommended by the AAP and Bright Futures at every HSV but the fewest milestones with normative data were identified for this domain, often self-help rather than social engagement or emotion regulation skills. The cross-cultural study cited for many of the new milestones was reassuring overall in that the median ages for 67%-88% of milestones in most domains were equivalent across the four countries sampled, but only 22% of self-help skills were equivalent.3 This should remind us that parenting has more influence over psychosocial skills than other domains. Psychosocial and behavioral functioning, especially emotional regulation, also deserve “surveillance” as they have enormous impact on life outcomes but need to be measured and supported differently. Routine use of validated tools such as the Early Childhood Screening Assessment or the Ages & Stages Questionnaires: Social-Emotional for these domains are also needed.

Normal variations in temperament and patterns of attachment can affect many milestones including courage for walking, exploration, social engagement, and prosocial behaviors or self-control for social situations, attention, range of affect, and cooperation. All of these skills are among the 42 total (14 new) social-emotional milestones for 0- to 5-year-olds. Variations in these functions are at the root of the most common “challenging behaviors” in our studies in primary care. They are also the most vulnerable to suboptimal parent-child relationships, adverse childhood experiences, and social determinants of health.

As primary care providers, we not only need to detect children at risk for developmental problems but also promote and celebrate developmental progress. I hope that changing the threshold for concern to 75% will allow for a more positive review with the family (as fewer will be flagged as at risk) and chance to congratulate parents on all that is going well. But I also hope the change will not make us overlook parenting challenges, often from the psychosocial milestones most amenable to our guidance and support.

Early identification is mainly important to obtain the early intervention shown to improve outcomes. However, less than 25% of children with delays or disabilities receive early intervention before age 3 and most with emotional, behavioral, and developmental conditions, other than autism spectrum disorder, not before age 5. Since early intervention services are freely available in all states, we also need to do better at getting children to this care.

Let’s reconsider the process of developmental surveillance in this light of delayed referral: “Eliciting concerns” is key as parents have been shown to be usually correct in their worries. Listening to how they express the concerns can help you connect their specific issues when discussing reasons for referral. While most parent “recall of past milestones” is not accurate, current milestones reported are; thus, the need to have the new more accurate norms for all ages for comparison. When we make observations of a child’s abilities and behaviors ourselves we may not only pick up on issues missed by the parent, but will be more convincing in conveying the need for referral when indicated. When we “examine” the child we can use our professional skills to determine the very important risk factor of the quality of how a skill is performed, not just that it is. The recommended “use of validated screening tools” when the new milestones are not met give us an objective tool to share with parents, more confidence in when referral is warranted, which we will convey to parents (and perhaps skeptical relatives), and baseline documentation from which we can “track” referrals, progress, and, hopefully, better outcomes.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Zubler JM et al. Pediatrics. 2022;149(3):e2021052138.

2. Gessell A et al. Macmillan: New York, 1928.

3. Ertem IO et al. Lancet Glob Health. 2018 Mar;6(3):e279-91.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, with funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, studied the CDC’s “Learn the Signs. Act Early” developmental surveillance milestones for children 0-5 years to update the milestones based on published studies. The goal was to improve this tool for developmental surveillance and use by the public. Developmental surveillance is not just observing a child at a check-up but rather “is a longitudinal process that involves eliciting concerns, taking a developmental history based on milestone attainment, observing milestones and other behaviors, examining the child, and applying clinical judgment during health supervision visits (HSVs).”1

While the milestones we were trained on were a good start and highlighted the developmental progression central to pediatrics, they were not based on norms or cut scores indicating significant developmental risk unless taught from a validated tool. The CDC was concerned that their public handouts and apps were based on median ages (middle number of the entire range) of attainment not the mode (most common) or even average ages. That means that about half of all typically developing children would “not have attained” that skill at the age noted, potentially evoking unnecessary concern for parents and a “wait-and-see” message from a knowledgeable provider who realized the statistical meaning and the broad range of normal. Another potential problem with using milestones set at the median age is that parents, especially those with several children or experienced friends, may see the provider as an alarmist when they have seen great variation in children who later were normal. This reaction can dampen provider willingness to discuss development or even to screen with validated tools. We have learned the hard way from COVID-19 that it is difficult to convey concepts of risk effectively both balancing fear and stimulating action.

The AAP experts reviewed the English literature for data-based milestones, finding 34 articles, 10 of which had an opinion for at least one milestone. If this sounds like a very small number, you are correct. You may not realize that almost all screening and diagnostic tools have been based on data collected by Gesell in 1928!2 While most of health care has changed since then, which milestones are measured in infants has not.

The biggest change from this review was deciding to use as milestones skills reported for 75% of children at each age of typical HSVs, adding ones for 15 and 30 months. The implication is that children not attaining these milestones are all at risk and deserving of more careful history, examination, and administration of a validated screening tool; not true when based on median data. Of the 94 existing CDC milestones retained after the review, one-third were moved to a different age with 21 of 31 assigned to an older age. Domains of functioning for the milestones were consolidated into social emotional, cognitive, language/communication, and motor, to help parents learn to distinguish these areas, and, although many milestones reflect several domains, each was included only once to reduce confusion.

Psychosocial assessment is recommended by the AAP and Bright Futures at every HSV but the fewest milestones with normative data were identified for this domain, often self-help rather than social engagement or emotion regulation skills. The cross-cultural study cited for many of the new milestones was reassuring overall in that the median ages for 67%-88% of milestones in most domains were equivalent across the four countries sampled, but only 22% of self-help skills were equivalent.3 This should remind us that parenting has more influence over psychosocial skills than other domains. Psychosocial and behavioral functioning, especially emotional regulation, also deserve “surveillance” as they have enormous impact on life outcomes but need to be measured and supported differently. Routine use of validated tools such as the Early Childhood Screening Assessment or the Ages & Stages Questionnaires: Social-Emotional for these domains are also needed.

Normal variations in temperament and patterns of attachment can affect many milestones including courage for walking, exploration, social engagement, and prosocial behaviors or self-control for social situations, attention, range of affect, and cooperation. All of these skills are among the 42 total (14 new) social-emotional milestones for 0- to 5-year-olds. Variations in these functions are at the root of the most common “challenging behaviors” in our studies in primary care. They are also the most vulnerable to suboptimal parent-child relationships, adverse childhood experiences, and social determinants of health.

As primary care providers, we not only need to detect children at risk for developmental problems but also promote and celebrate developmental progress. I hope that changing the threshold for concern to 75% will allow for a more positive review with the family (as fewer will be flagged as at risk) and chance to congratulate parents on all that is going well. But I also hope the change will not make us overlook parenting challenges, often from the psychosocial milestones most amenable to our guidance and support.

Early identification is mainly important to obtain the early intervention shown to improve outcomes. However, less than 25% of children with delays or disabilities receive early intervention before age 3 and most with emotional, behavioral, and developmental conditions, other than autism spectrum disorder, not before age 5. Since early intervention services are freely available in all states, we also need to do better at getting children to this care.

Let’s reconsider the process of developmental surveillance in this light of delayed referral: “Eliciting concerns” is key as parents have been shown to be usually correct in their worries. Listening to how they express the concerns can help you connect their specific issues when discussing reasons for referral. While most parent “recall of past milestones” is not accurate, current milestones reported are; thus, the need to have the new more accurate norms for all ages for comparison. When we make observations of a child’s abilities and behaviors ourselves we may not only pick up on issues missed by the parent, but will be more convincing in conveying the need for referral when indicated. When we “examine” the child we can use our professional skills to determine the very important risk factor of the quality of how a skill is performed, not just that it is. The recommended “use of validated screening tools” when the new milestones are not met give us an objective tool to share with parents, more confidence in when referral is warranted, which we will convey to parents (and perhaps skeptical relatives), and baseline documentation from which we can “track” referrals, progress, and, hopefully, better outcomes.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Zubler JM et al. Pediatrics. 2022;149(3):e2021052138.

2. Gessell A et al. Macmillan: New York, 1928.

3. Ertem IO et al. Lancet Glob Health. 2018 Mar;6(3):e279-91.

Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia

THE PRESENTATION

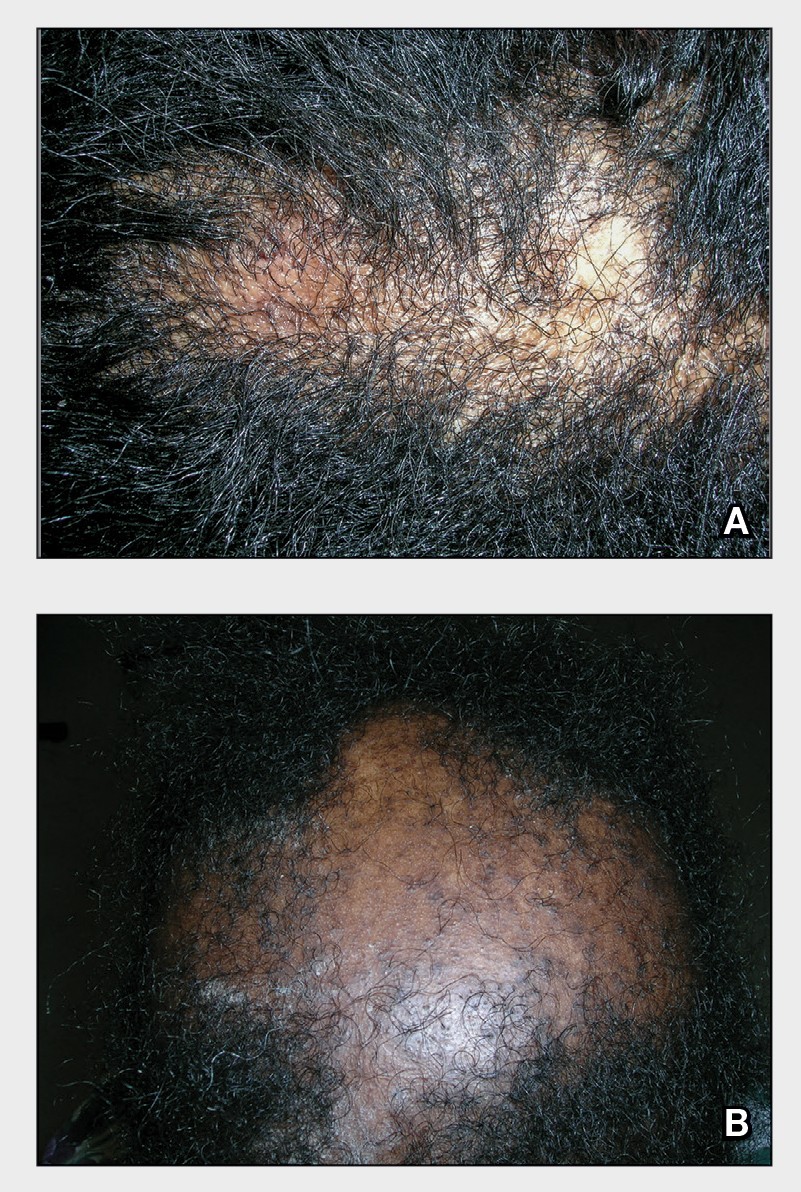

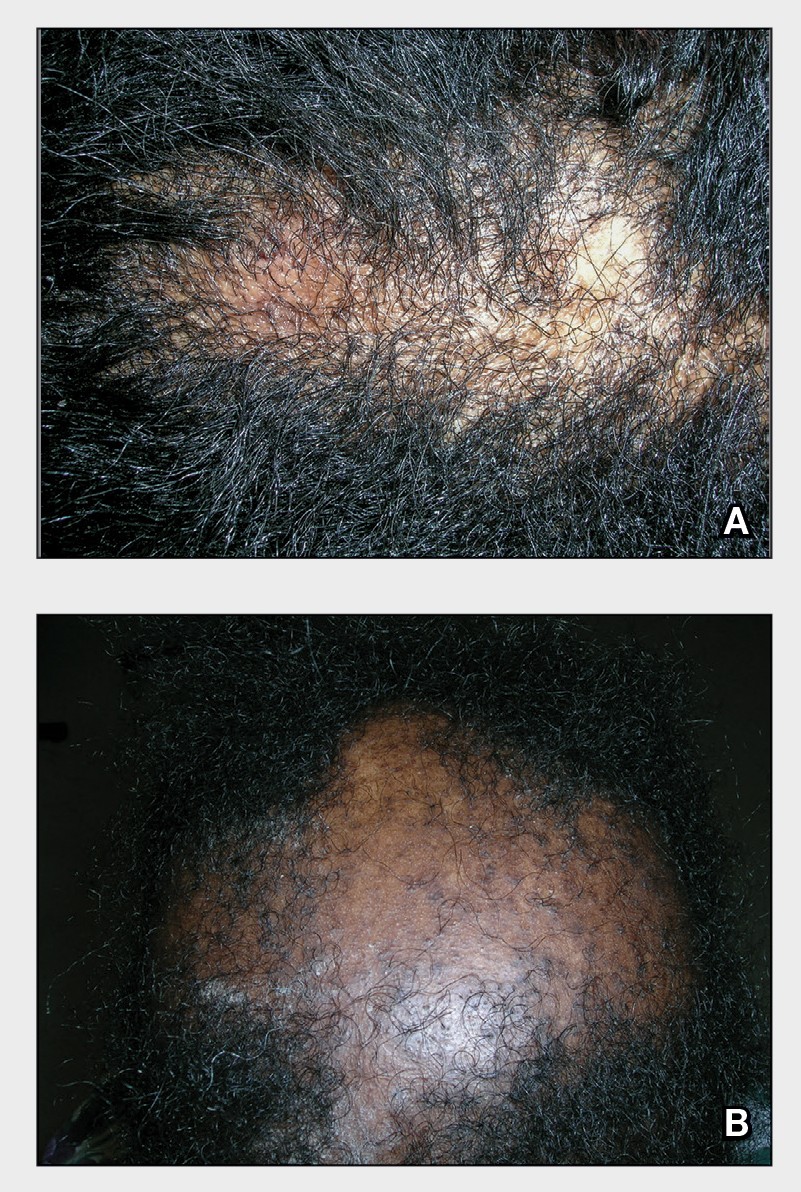

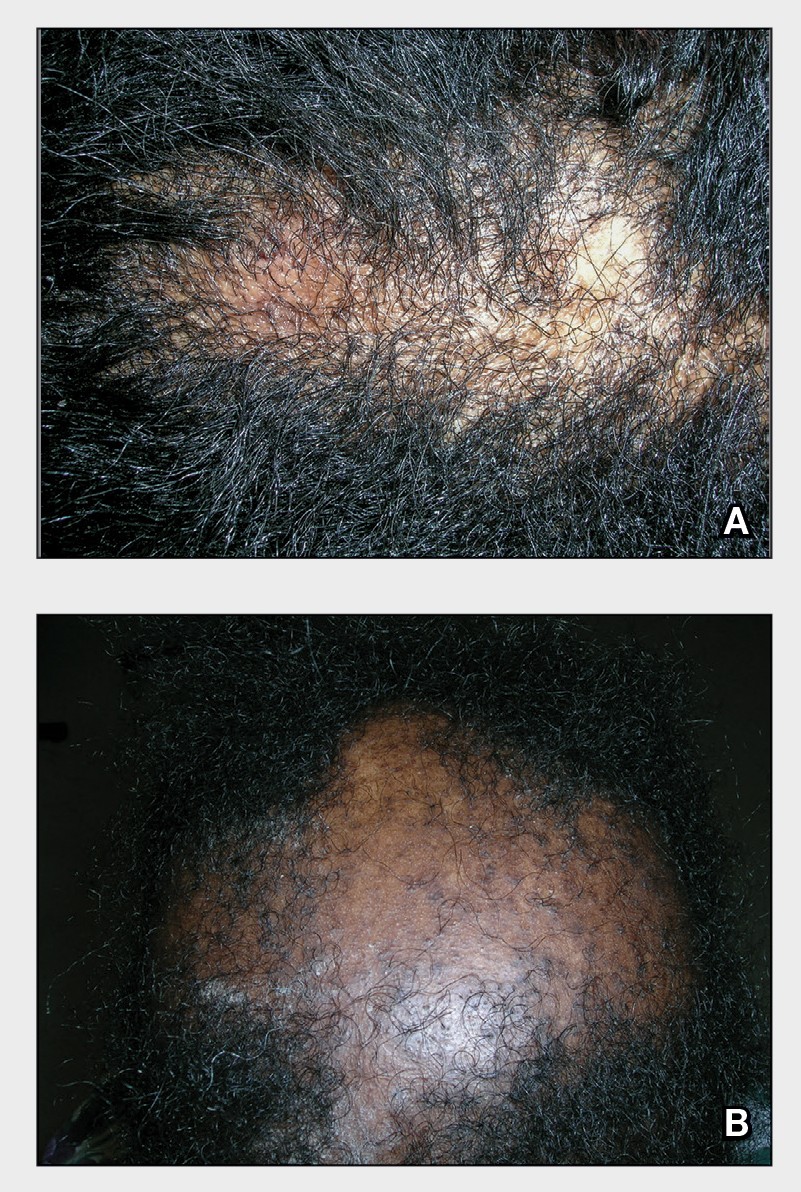

A Early central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a small central patch of hair loss in a 45-year-old Black woman.

B Late central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a large central patch of hair loss in a 43-year-old Black woman.

Scarring alopecia is a collection of hair loss disorders including chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus), lichen planopilaris, dissecting cellulitis, acne keloidalis, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA).1 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (formerly hot comb alopecia or follicular degeneration syndrome) is a progressive, scarring, inflammatory alopecia and represents the most common form of scarring alopecia in women of African descent. It results in permanent destruction of hair follicles.

Epidemiology

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia predominantly affects women of African descent but also may affect men. The prevalence of CCCA in those of African descent has varied in the literature. Khumalo2 reported a prevalence of 1.2% for women younger than 50 years and 6.7% in women older than 50 years. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia has been reported in other ethnic groups, such as those of Asian descent.3

Historically, hair care practices that are more common in those of African descent, such as high-tension hairstyles as well as heat and chemical hair relaxers, were implicated in the development of CCCA. However, the causes of CCCA are most likely multifactorial, including family history, genetic mutations, and hair care practices.4-7 PADI3 mutations likely predispose some women to CCCA. Mutations in PADI3, which encodes peptidyl arginine deiminase 3 (an enzyme that modifies proteins crucial for the formation of hair shafts), were found in some patients with CCCA.8 Moreover, other genetic defects also likely play a role.7

Key clinical features

Early recognition is key for patients with CCCA.

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia begins in the central scalp (crown area, vertex) and spreads centrifugally.

• Scalp symptoms such as tenderness, pain, a tingling or crawling sensation, and itching may occur.9 Some patients may not have any symptoms at all, and hair loss may progress painlessly.

• Central hair breakage—forme fruste CCCA—may be a presenting sign of CCCA.9

• Loss of follicular ostia and mottled hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules are common findings.6

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia can be diagnosed clinically and by histopathology.

Worth noting

Patients may experience hair loss and scalp symptoms for years before seeking medical evaluation. In some cultures, hair breakage or itching on the top of the scalp may be viewed as a normal occurrence in life.

It is important to set patient expectations that CCCA is a scarring alopecia, and the initial goal often is to maintain the patient's existing hair. However, hair and areas responding to treatment should still be treated. Without any intervention, the resulting scarring from CCCA may permanently scar follicles on the entire scalp.

Due to the inflammatory nature of CCCA, potent topical corticosteroids (eg, clobetasol propionate), intralesional corticosteroids (eg, triamcinolone acetonide), and oral anti-inflammatory agents (eg, doxycycline) are utilized in the treatment of CCCA. Minoxidil is another treatment option. Adjuvant therapies such as topical metformin also have been tried.10 Importantly, treatment of CCCA may halt further permanent destruction of hair follicles, but scalp symptoms may reappear periodically and require re-treatment with anti-inflammatory agents.

Health care highlight

Thorough scalp examination and awareness of clinical features of CCCA may prompt earlier diagnosis and prevent future severe permanent alopecia. Clinicians should encourage patients with suggestive signs or symptoms of CCCA to seek care from a dermatologist.

- Sperling LC. Scarring alopecia and the dermatopathologist. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:333-342. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001 .280701.x

- Khumalo NP. Prevalence of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1453-1454. doi:10.1001/archderm.147.12.1453

- Su HJ, Cheng AY, Liu CH, et al. Primary scarring alopecia: a retrospective study of 89 patients in Taiwan [published online January 16, 2018]. J Dermatol. 2018;45:450-455. doi:10.1111 /1346-8138.14217

- Sperling LC, Cowper SE. The histopathology of primary cicatricial alopecia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:41-50

- Dlova NC, Forder M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: possible familial aetiology in two African families from South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(supp 1):17-20, 20-23.

- Ogunleye TA, Quinn CR, McMichael A. Alopecia. In: Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill; 2016:253-264.

- Uitto J. Genetic susceptibility to alopecia [published online February 13, 2019]. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:873-876. doi:10.1056 /NEJMe1900042

- Malki L, Sarig O, Romano MT, et al. Variant PADI3 in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:833-841.

- Callender VD, Wright DR, Davis EC, et al. Hair breakage as a presenting sign of early or occult central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: clinicopathologic findings in 9 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1047-1052.

- Araoye EF, Thomas JAL, Aguh CU. Hair regrowth in 2 patients with recalcitrant central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia after use of topical metformin. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:106-108. doi:10.1016/j .jdcr.2019.12.008

THE PRESENTATION

A Early central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a small central patch of hair loss in a 45-year-old Black woman.

B Late central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a large central patch of hair loss in a 43-year-old Black woman.

Scarring alopecia is a collection of hair loss disorders including chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus), lichen planopilaris, dissecting cellulitis, acne keloidalis, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA).1 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (formerly hot comb alopecia or follicular degeneration syndrome) is a progressive, scarring, inflammatory alopecia and represents the most common form of scarring alopecia in women of African descent. It results in permanent destruction of hair follicles.

Epidemiology

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia predominantly affects women of African descent but also may affect men. The prevalence of CCCA in those of African descent has varied in the literature. Khumalo2 reported a prevalence of 1.2% for women younger than 50 years and 6.7% in women older than 50 years. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia has been reported in other ethnic groups, such as those of Asian descent.3

Historically, hair care practices that are more common in those of African descent, such as high-tension hairstyles as well as heat and chemical hair relaxers, were implicated in the development of CCCA. However, the causes of CCCA are most likely multifactorial, including family history, genetic mutations, and hair care practices.4-7 PADI3 mutations likely predispose some women to CCCA. Mutations in PADI3, which encodes peptidyl arginine deiminase 3 (an enzyme that modifies proteins crucial for the formation of hair shafts), were found in some patients with CCCA.8 Moreover, other genetic defects also likely play a role.7

Key clinical features

Early recognition is key for patients with CCCA.

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia begins in the central scalp (crown area, vertex) and spreads centrifugally.

• Scalp symptoms such as tenderness, pain, a tingling or crawling sensation, and itching may occur.9 Some patients may not have any symptoms at all, and hair loss may progress painlessly.

• Central hair breakage—forme fruste CCCA—may be a presenting sign of CCCA.9

• Loss of follicular ostia and mottled hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules are common findings.6

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia can be diagnosed clinically and by histopathology.

Worth noting

Patients may experience hair loss and scalp symptoms for years before seeking medical evaluation. In some cultures, hair breakage or itching on the top of the scalp may be viewed as a normal occurrence in life.

It is important to set patient expectations that CCCA is a scarring alopecia, and the initial goal often is to maintain the patient's existing hair. However, hair and areas responding to treatment should still be treated. Without any intervention, the resulting scarring from CCCA may permanently scar follicles on the entire scalp.

Due to the inflammatory nature of CCCA, potent topical corticosteroids (eg, clobetasol propionate), intralesional corticosteroids (eg, triamcinolone acetonide), and oral anti-inflammatory agents (eg, doxycycline) are utilized in the treatment of CCCA. Minoxidil is another treatment option. Adjuvant therapies such as topical metformin also have been tried.10 Importantly, treatment of CCCA may halt further permanent destruction of hair follicles, but scalp symptoms may reappear periodically and require re-treatment with anti-inflammatory agents.

Health care highlight

Thorough scalp examination and awareness of clinical features of CCCA may prompt earlier diagnosis and prevent future severe permanent alopecia. Clinicians should encourage patients with suggestive signs or symptoms of CCCA to seek care from a dermatologist.

THE PRESENTATION

A Early central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a small central patch of hair loss in a 45-year-old Black woman.

B Late central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a large central patch of hair loss in a 43-year-old Black woman.

Scarring alopecia is a collection of hair loss disorders including chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus), lichen planopilaris, dissecting cellulitis, acne keloidalis, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA).1 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (formerly hot comb alopecia or follicular degeneration syndrome) is a progressive, scarring, inflammatory alopecia and represents the most common form of scarring alopecia in women of African descent. It results in permanent destruction of hair follicles.

Epidemiology

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia predominantly affects women of African descent but also may affect men. The prevalence of CCCA in those of African descent has varied in the literature. Khumalo2 reported a prevalence of 1.2% for women younger than 50 years and 6.7% in women older than 50 years. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia has been reported in other ethnic groups, such as those of Asian descent.3

Historically, hair care practices that are more common in those of African descent, such as high-tension hairstyles as well as heat and chemical hair relaxers, were implicated in the development of CCCA. However, the causes of CCCA are most likely multifactorial, including family history, genetic mutations, and hair care practices.4-7 PADI3 mutations likely predispose some women to CCCA. Mutations in PADI3, which encodes peptidyl arginine deiminase 3 (an enzyme that modifies proteins crucial for the formation of hair shafts), were found in some patients with CCCA.8 Moreover, other genetic defects also likely play a role.7

Key clinical features

Early recognition is key for patients with CCCA.

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia begins in the central scalp (crown area, vertex) and spreads centrifugally.

• Scalp symptoms such as tenderness, pain, a tingling or crawling sensation, and itching may occur.9 Some patients may not have any symptoms at all, and hair loss may progress painlessly.

• Central hair breakage—forme fruste CCCA—may be a presenting sign of CCCA.9

• Loss of follicular ostia and mottled hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules are common findings.6

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia can be diagnosed clinically and by histopathology.

Worth noting

Patients may experience hair loss and scalp symptoms for years before seeking medical evaluation. In some cultures, hair breakage or itching on the top of the scalp may be viewed as a normal occurrence in life.

It is important to set patient expectations that CCCA is a scarring alopecia, and the initial goal often is to maintain the patient's existing hair. However, hair and areas responding to treatment should still be treated. Without any intervention, the resulting scarring from CCCA may permanently scar follicles on the entire scalp.

Due to the inflammatory nature of CCCA, potent topical corticosteroids (eg, clobetasol propionate), intralesional corticosteroids (eg, triamcinolone acetonide), and oral anti-inflammatory agents (eg, doxycycline) are utilized in the treatment of CCCA. Minoxidil is another treatment option. Adjuvant therapies such as topical metformin also have been tried.10 Importantly, treatment of CCCA may halt further permanent destruction of hair follicles, but scalp symptoms may reappear periodically and require re-treatment with anti-inflammatory agents.

Health care highlight

Thorough scalp examination and awareness of clinical features of CCCA may prompt earlier diagnosis and prevent future severe permanent alopecia. Clinicians should encourage patients with suggestive signs or symptoms of CCCA to seek care from a dermatologist.

- Sperling LC. Scarring alopecia and the dermatopathologist. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:333-342. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001 .280701.x

- Khumalo NP. Prevalence of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1453-1454. doi:10.1001/archderm.147.12.1453

- Su HJ, Cheng AY, Liu CH, et al. Primary scarring alopecia: a retrospective study of 89 patients in Taiwan [published online January 16, 2018]. J Dermatol. 2018;45:450-455. doi:10.1111 /1346-8138.14217

- Sperling LC, Cowper SE. The histopathology of primary cicatricial alopecia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:41-50

- Dlova NC, Forder M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: possible familial aetiology in two African families from South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(supp 1):17-20, 20-23.

- Ogunleye TA, Quinn CR, McMichael A. Alopecia. In: Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill; 2016:253-264.

- Uitto J. Genetic susceptibility to alopecia [published online February 13, 2019]. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:873-876. doi:10.1056 /NEJMe1900042

- Malki L, Sarig O, Romano MT, et al. Variant PADI3 in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:833-841.

- Callender VD, Wright DR, Davis EC, et al. Hair breakage as a presenting sign of early or occult central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: clinicopathologic findings in 9 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1047-1052.

- Araoye EF, Thomas JAL, Aguh CU. Hair regrowth in 2 patients with recalcitrant central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia after use of topical metformin. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:106-108. doi:10.1016/j .jdcr.2019.12.008

- Sperling LC. Scarring alopecia and the dermatopathologist. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:333-342. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001 .280701.x

- Khumalo NP. Prevalence of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1453-1454. doi:10.1001/archderm.147.12.1453

- Su HJ, Cheng AY, Liu CH, et al. Primary scarring alopecia: a retrospective study of 89 patients in Taiwan [published online January 16, 2018]. J Dermatol. 2018;45:450-455. doi:10.1111 /1346-8138.14217

- Sperling LC, Cowper SE. The histopathology of primary cicatricial alopecia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:41-50

- Dlova NC, Forder M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: possible familial aetiology in two African families from South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(supp 1):17-20, 20-23.

- Ogunleye TA, Quinn CR, McMichael A. Alopecia. In: Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill; 2016:253-264.

- Uitto J. Genetic susceptibility to alopecia [published online February 13, 2019]. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:873-876. doi:10.1056 /NEJMe1900042

- Malki L, Sarig O, Romano MT, et al. Variant PADI3 in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:833-841.

- Callender VD, Wright DR, Davis EC, et al. Hair breakage as a presenting sign of early or occult central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: clinicopathologic findings in 9 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1047-1052.

- Araoye EF, Thomas JAL, Aguh CU. Hair regrowth in 2 patients with recalcitrant central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia after use of topical metformin. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:106-108. doi:10.1016/j .jdcr.2019.12.008

Study finds discrepancies in biopsy decisions, diagnoses based on skin type

BOSTON – compared with White patients, new research shows.

“Our findings suggest diagnostic biases based on skin color exist in dermatology practice,” lead author Loren Krueger, MD, assistant professor in the department of dermatology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, said at the Annual Skin of Color Society Scientific Symposium. “A lower likelihood of biopsy of malignancy in darker skin types could contribute to disparities in cutaneous malignancies,” she added.

Disparities in dermatologic care among Black patients, compared with White patients, have been well documented. Recent evidence includes a 2020 study that showed significant shortcomings among medical students in correctly diagnosing squamous cell carcinoma, urticaria, and atopic dermatitis for patients with skin of color.

“It’s no secret that our images do not accurately or in the right quantity include skin of color,” Dr. Krueger said. “Yet few papers talk about how these biases actually impact our care. Importantly, this study demonstrates that diagnostic bias develops as early as the medical student level.”

To further investigate the role of skin color in the assessment of neoplastic and inflammatory skin conditions and decisions to perform biopsy, Dr. Krueger and her colleagues surveyed 144 dermatology residents and attending dermatologists to evaluate their clinical decisionmaking skills in assessing skin conditions for patients with lighter skin and those with darker skin. Almost 80% (113) provided complete responses and were included in the study.

For the survey, participants were shown photos of 10 neoplastic and 10 inflammatory skin conditions. Each image was matched in lighter (skin types I-II) and darker (skin types IV-VI) skinned patients in random order. Participants were asked to identify the suspected underlying etiology (neoplastic–benign, neoplastic–malignant, papulosquamous, lichenoid, infectious, bullous, or no suspected etiology) and whether they would choose to perform biopsy for the pictured condition.

Overall, their responses showed a slightly higher probability of recommending a biopsy for patients with skin types IV-V (odds ratio, 1.18; P = .054).

However, respondents were more than twice as likely to recommend a biopsy for benign neoplasms for patients with skin of color, compared with those with lighter skin types (OR, 2.57; P < .0001). They were significantly less likely to recommend a biopsy for a malignant neoplasm for patients with skin of color (OR, 0.42; P < .0001).

In addition, the correct etiology was much more commonly missed in diagnosing patients with skin of color, even after adjusting for years in dermatology practice (OR, 0.569; P < .0001).

Conversely, respondents were significantly less likely to recommend a biopsy for benign neoplasms and were more likely to recommend a biopsy for malignant neoplasms among White patients. Etiology was more commonly correct.

The findings underscore that “for skin of color patients, you’re more likely to have a benign neoplasm biopsied, you’re less likely to have a malignant neoplasm biopsied, and more often, your etiology may be missed,” Dr. Krueger said at the meeting.

Of note, while 45% of respondents were dermatology residents or fellows, 20.4% had 1-5 years of experience, and about 28% had 10 to more than 25 years of experience.

And while 75% of the dermatology residents, fellows, and attendings were White, there was no difference in the probability of correctly identifying the underlying etiology in dark or light skin types based on the provider’s self-identified race.

Importantly, the patterns in the study of diagnostic discrepancies are reflected in broader dermatologic outcomes. The 5-year melanoma survival rate is 74.1% among Black patients and 92.9% among White patients. Dr. Krueger referred to data showing that only 52.6% of Black patients have stage I melanoma at diagnosis, whereas among White patients, the rate is much higher, at 75.9%.

“We know skin malignancy can be more aggressive and late-stage in skin of color populations, leading to increased morbidity and later stage at initial diagnosis,” Dr. Krueger told this news organization. “We routinely attribute this to limited access to care and lack of awareness on skin malignancy. However, we have no evidence on how we, as dermatologists, may be playing a role.”

Furthermore, the decision to perform biopsy or not can affect the size and stage at diagnosis of a cutaneous malignancy, she noted.

Key changes needed to prevent the disparities – and their implications – should start at the training level, she emphasized. “I would love to see increased photo representation in training materials – this is a great place to start,” Dr. Krueger said.

In addition, “encouraging medical students, residents, and dermatologists to learn from skin of color experts is vital,” she said. “We should also provide hands-on experience and training with diverse patient populations.”

The first step to addressing biases “is to acknowledge they exist,” Dr. Krueger added. “I am hopeful this inspires others to continue to investigate these biases, as well as how we can eliminate them.”

The study was funded by the Rudin Resident Research Award. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BOSTON – compared with White patients, new research shows.

“Our findings suggest diagnostic biases based on skin color exist in dermatology practice,” lead author Loren Krueger, MD, assistant professor in the department of dermatology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, said at the Annual Skin of Color Society Scientific Symposium. “A lower likelihood of biopsy of malignancy in darker skin types could contribute to disparities in cutaneous malignancies,” she added.

Disparities in dermatologic care among Black patients, compared with White patients, have been well documented. Recent evidence includes a 2020 study that showed significant shortcomings among medical students in correctly diagnosing squamous cell carcinoma, urticaria, and atopic dermatitis for patients with skin of color.

“It’s no secret that our images do not accurately or in the right quantity include skin of color,” Dr. Krueger said. “Yet few papers talk about how these biases actually impact our care. Importantly, this study demonstrates that diagnostic bias develops as early as the medical student level.”

To further investigate the role of skin color in the assessment of neoplastic and inflammatory skin conditions and decisions to perform biopsy, Dr. Krueger and her colleagues surveyed 144 dermatology residents and attending dermatologists to evaluate their clinical decisionmaking skills in assessing skin conditions for patients with lighter skin and those with darker skin. Almost 80% (113) provided complete responses and were included in the study.

For the survey, participants were shown photos of 10 neoplastic and 10 inflammatory skin conditions. Each image was matched in lighter (skin types I-II) and darker (skin types IV-VI) skinned patients in random order. Participants were asked to identify the suspected underlying etiology (neoplastic–benign, neoplastic–malignant, papulosquamous, lichenoid, infectious, bullous, or no suspected etiology) and whether they would choose to perform biopsy for the pictured condition.

Overall, their responses showed a slightly higher probability of recommending a biopsy for patients with skin types IV-V (odds ratio, 1.18; P = .054).

However, respondents were more than twice as likely to recommend a biopsy for benign neoplasms for patients with skin of color, compared with those with lighter skin types (OR, 2.57; P < .0001). They were significantly less likely to recommend a biopsy for a malignant neoplasm for patients with skin of color (OR, 0.42; P < .0001).

In addition, the correct etiology was much more commonly missed in diagnosing patients with skin of color, even after adjusting for years in dermatology practice (OR, 0.569; P < .0001).

Conversely, respondents were significantly less likely to recommend a biopsy for benign neoplasms and were more likely to recommend a biopsy for malignant neoplasms among White patients. Etiology was more commonly correct.

The findings underscore that “for skin of color patients, you’re more likely to have a benign neoplasm biopsied, you’re less likely to have a malignant neoplasm biopsied, and more often, your etiology may be missed,” Dr. Krueger said at the meeting.

Of note, while 45% of respondents were dermatology residents or fellows, 20.4% had 1-5 years of experience, and about 28% had 10 to more than 25 years of experience.

And while 75% of the dermatology residents, fellows, and attendings were White, there was no difference in the probability of correctly identifying the underlying etiology in dark or light skin types based on the provider’s self-identified race.

Importantly, the patterns in the study of diagnostic discrepancies are reflected in broader dermatologic outcomes. The 5-year melanoma survival rate is 74.1% among Black patients and 92.9% among White patients. Dr. Krueger referred to data showing that only 52.6% of Black patients have stage I melanoma at diagnosis, whereas among White patients, the rate is much higher, at 75.9%.

“We know skin malignancy can be more aggressive and late-stage in skin of color populations, leading to increased morbidity and later stage at initial diagnosis,” Dr. Krueger told this news organization. “We routinely attribute this to limited access to care and lack of awareness on skin malignancy. However, we have no evidence on how we, as dermatologists, may be playing a role.”

Furthermore, the decision to perform biopsy or not can affect the size and stage at diagnosis of a cutaneous malignancy, she noted.

Key changes needed to prevent the disparities – and their implications – should start at the training level, she emphasized. “I would love to see increased photo representation in training materials – this is a great place to start,” Dr. Krueger said.

In addition, “encouraging medical students, residents, and dermatologists to learn from skin of color experts is vital,” she said. “We should also provide hands-on experience and training with diverse patient populations.”

The first step to addressing biases “is to acknowledge they exist,” Dr. Krueger added. “I am hopeful this inspires others to continue to investigate these biases, as well as how we can eliminate them.”

The study was funded by the Rudin Resident Research Award. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BOSTON – compared with White patients, new research shows.

“Our findings suggest diagnostic biases based on skin color exist in dermatology practice,” lead author Loren Krueger, MD, assistant professor in the department of dermatology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, said at the Annual Skin of Color Society Scientific Symposium. “A lower likelihood of biopsy of malignancy in darker skin types could contribute to disparities in cutaneous malignancies,” she added.

Disparities in dermatologic care among Black patients, compared with White patients, have been well documented. Recent evidence includes a 2020 study that showed significant shortcomings among medical students in correctly diagnosing squamous cell carcinoma, urticaria, and atopic dermatitis for patients with skin of color.

“It’s no secret that our images do not accurately or in the right quantity include skin of color,” Dr. Krueger said. “Yet few papers talk about how these biases actually impact our care. Importantly, this study demonstrates that diagnostic bias develops as early as the medical student level.”

To further investigate the role of skin color in the assessment of neoplastic and inflammatory skin conditions and decisions to perform biopsy, Dr. Krueger and her colleagues surveyed 144 dermatology residents and attending dermatologists to evaluate their clinical decisionmaking skills in assessing skin conditions for patients with lighter skin and those with darker skin. Almost 80% (113) provided complete responses and were included in the study.

For the survey, participants were shown photos of 10 neoplastic and 10 inflammatory skin conditions. Each image was matched in lighter (skin types I-II) and darker (skin types IV-VI) skinned patients in random order. Participants were asked to identify the suspected underlying etiology (neoplastic–benign, neoplastic–malignant, papulosquamous, lichenoid, infectious, bullous, or no suspected etiology) and whether they would choose to perform biopsy for the pictured condition.

Overall, their responses showed a slightly higher probability of recommending a biopsy for patients with skin types IV-V (odds ratio, 1.18; P = .054).

However, respondents were more than twice as likely to recommend a biopsy for benign neoplasms for patients with skin of color, compared with those with lighter skin types (OR, 2.57; P < .0001). They were significantly less likely to recommend a biopsy for a malignant neoplasm for patients with skin of color (OR, 0.42; P < .0001).

In addition, the correct etiology was much more commonly missed in diagnosing patients with skin of color, even after adjusting for years in dermatology practice (OR, 0.569; P < .0001).

Conversely, respondents were significantly less likely to recommend a biopsy for benign neoplasms and were more likely to recommend a biopsy for malignant neoplasms among White patients. Etiology was more commonly correct.

The findings underscore that “for skin of color patients, you’re more likely to have a benign neoplasm biopsied, you’re less likely to have a malignant neoplasm biopsied, and more often, your etiology may be missed,” Dr. Krueger said at the meeting.

Of note, while 45% of respondents were dermatology residents or fellows, 20.4% had 1-5 years of experience, and about 28% had 10 to more than 25 years of experience.

And while 75% of the dermatology residents, fellows, and attendings were White, there was no difference in the probability of correctly identifying the underlying etiology in dark or light skin types based on the provider’s self-identified race.

Importantly, the patterns in the study of diagnostic discrepancies are reflected in broader dermatologic outcomes. The 5-year melanoma survival rate is 74.1% among Black patients and 92.9% among White patients. Dr. Krueger referred to data showing that only 52.6% of Black patients have stage I melanoma at diagnosis, whereas among White patients, the rate is much higher, at 75.9%.

“We know skin malignancy can be more aggressive and late-stage in skin of color populations, leading to increased morbidity and later stage at initial diagnosis,” Dr. Krueger told this news organization. “We routinely attribute this to limited access to care and lack of awareness on skin malignancy. However, we have no evidence on how we, as dermatologists, may be playing a role.”

Furthermore, the decision to perform biopsy or not can affect the size and stage at diagnosis of a cutaneous malignancy, she noted.

Key changes needed to prevent the disparities – and their implications – should start at the training level, she emphasized. “I would love to see increased photo representation in training materials – this is a great place to start,” Dr. Krueger said.

In addition, “encouraging medical students, residents, and dermatologists to learn from skin of color experts is vital,” she said. “We should also provide hands-on experience and training with diverse patient populations.”

The first step to addressing biases “is to acknowledge they exist,” Dr. Krueger added. “I am hopeful this inspires others to continue to investigate these biases, as well as how we can eliminate them.”

The study was funded by the Rudin Resident Research Award. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender youth: Bringing evidence to the political debates

In 2021, state lawmakers introduced a record number of bills that would affect transgender and gender-diverse people. The vast majority were focused on transgender and gender-diverse youth in particular. We’ve seen bills that would take away gender-affirming medical care for minors, ones that would force trans kids to play on sports teams that don’t match their gender identity, and others that would ban trans kids from public facilities like bathrooms that match their gender identities.

These bills aren’t particularly new, but state lawmakers are putting more energy into them than ever. In response, some public figures have started pushing back. Ariana Grande just pledged to match up to 1.5 million dollars in donations to combat anti–trans youth legislative initiatives. However, doctors have been underrepresented in the political discourse.

Sadly, much of the discussion in this area has been driven by wild speculation and emotional rhetoric. It’s rare that we see actual data brought to the table. As clinicians and scientists, we have a responsibility to highlight the data relevant to these legislative debates, and to share them with our representatives. I’m going to break down what we know quantitatively about each of these issues, so that you’ll feel empowered to bring that information to these debates. My hope is that we can move toward evidence-based public policy instead of rhetoric-based public policy, so that we can ensure the best health possible for young people around the country.

Bathroom bills

Though they’ve been less of a focus recently, politicians for years have argued that trans people should be forced to use bathrooms and other public facilities that match their sex assigned at birth, not their gender identity. Their central argument is that trans-inclusive public facility policies will result in higher rates of assault. Published peer-review data show this isn’t true. A 2019 study in Sexuality Research and Social Policy examined the impacts of trans-inclusive public facility policies and found they resulted in no increase in assaults among the general (mostly cisgender) population. Another 2019 study in Pediatrics found that trans-inclusive facility policies were associated with lower odds of sexual assault victimization against transgender youth. The myth that trans-inclusive public facilities increase assault risk is simply that: a myth. All existing data indicate that trans-inclusive policies will improve public safety.

Sports bills

One of the hottest debates recently involves whether transgender girls should be allowed to participate in girls’ sports teams. Those in favor of these bills argue that transgender girls have an innate biological sports advantage over cisgender girls, and if allowed to compete in girls’ sports leagues, they will dominate the events, and cisgender girls will no longer win sports titles. The bills feed into longstanding assumptions – those who were assigned male at birth are strong, and those who were assigned female at birth are weak.

But evidence doesn’t show that trans women dominate female sports leagues. It turns out, there are shockingly few transgender athletes competing in sports leagues around the United States, and even fewer winning major titles. When the Associated Press conducted an investigation asking lawmakers introducing such sports bills to name trans athletes in their states, most couldn’t point to a single one. After Utah state legislators passed a trans sports ban, Governor Spencer Cox vetoed it, pointing out that, of 75,000 high school kids participating in sports in Utah, there was only a single transgender girl (the state legislature overrode the veto anyway).

California has explicitly protected the rights of trans athletes to compete on sports teams that match their gender identity since 2013. There’s still an underrepresentation of trans athletes in sports participation and titles. This is likely because the deck is stacked against these young people in so many other ways that are unrelated to testosterone levels. Trans youth suffer from high rates of harassment, discrimination, and subsequent anxiety and depression that make it difficult to compete in and excel in sports.

Medical bills

State legislators have introduced bills around the country that would criminalize the provision of gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth. Though such bills are opposed by all major medical organizations (including the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, and the American Psychiatric Association), misinformation continues to spread, and in some instances the bills have become law (though none are currently active due to legal challenges).

Clinicians should be aware that there have been sixteen studies to date, each with unique study designs, that have overall linked gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth to better mental health outcomes. While these interventions do (as with all medications) carry some risks (like delayed bone mineralization with pubertal suppression), the risks must be weighed against potential benefits. Unfortunately, these risks and benefits have not been accurately portrayed in state legislative debates. Politicians have spread a great deal of misinformation about gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth, including false assertions that puberty blockers cause infertility and that most transgender adolescents will grow up to identify as cisgender and regret gender-affirming medical interventions.

Minority stress

These bills have direct consequences for pediatric patients. For example, trans-inclusive bathroom policies are associated with lower rates of sexual assault. However, there are also important indirect effects to consider. The gender minority stress framework explains the ways in which stigmatizing national discourse drives higher rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidality among transgender youth. Under this model, so-called “distal factors” like the recent conversations at the national level that marginalize trans young people, are expected to drive higher rates of adverse mental health outcomes. As transgender youth hear high-profile politicians argue that they’re dangerous to their peers in bathrooms and on sports teams, it’s difficult to imagine their mental health would not worsen. Over time, such “distal factors” also lead to “proximal factors” like internalized transphobia in which youth begin to believe the negative things that are said about them. These dangerous processes can have dramatic negative impacts on self-esteem and emotional development. There is strong precedence that public policies have strong indirect mental health effects on LGBTQ youth.

We’ve entered a dangerous era in which politicians are legislating medical care and other aspects of public policy with the potential to hurt the mental health of our young patients. It’s imperative that clinicians and scientists contact their legislators to make sure they are voting for public policy based on data and fact, not misinformation and political rhetoric. The health of American children depends on it.

Dr. Turban (twitter.com/jack_turban) is a chief fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University.

In 2021, state lawmakers introduced a record number of bills that would affect transgender and gender-diverse people. The vast majority were focused on transgender and gender-diverse youth in particular. We’ve seen bills that would take away gender-affirming medical care for minors, ones that would force trans kids to play on sports teams that don’t match their gender identity, and others that would ban trans kids from public facilities like bathrooms that match their gender identities.

These bills aren’t particularly new, but state lawmakers are putting more energy into them than ever. In response, some public figures have started pushing back. Ariana Grande just pledged to match up to 1.5 million dollars in donations to combat anti–trans youth legislative initiatives. However, doctors have been underrepresented in the political discourse.

Sadly, much of the discussion in this area has been driven by wild speculation and emotional rhetoric. It’s rare that we see actual data brought to the table. As clinicians and scientists, we have a responsibility to highlight the data relevant to these legislative debates, and to share them with our representatives. I’m going to break down what we know quantitatively about each of these issues, so that you’ll feel empowered to bring that information to these debates. My hope is that we can move toward evidence-based public policy instead of rhetoric-based public policy, so that we can ensure the best health possible for young people around the country.

Bathroom bills

Though they’ve been less of a focus recently, politicians for years have argued that trans people should be forced to use bathrooms and other public facilities that match their sex assigned at birth, not their gender identity. Their central argument is that trans-inclusive public facility policies will result in higher rates of assault. Published peer-review data show this isn’t true. A 2019 study in Sexuality Research and Social Policy examined the impacts of trans-inclusive public facility policies and found they resulted in no increase in assaults among the general (mostly cisgender) population. Another 2019 study in Pediatrics found that trans-inclusive facility policies were associated with lower odds of sexual assault victimization against transgender youth. The myth that trans-inclusive public facilities increase assault risk is simply that: a myth. All existing data indicate that trans-inclusive policies will improve public safety.

Sports bills

One of the hottest debates recently involves whether transgender girls should be allowed to participate in girls’ sports teams. Those in favor of these bills argue that transgender girls have an innate biological sports advantage over cisgender girls, and if allowed to compete in girls’ sports leagues, they will dominate the events, and cisgender girls will no longer win sports titles. The bills feed into longstanding assumptions – those who were assigned male at birth are strong, and those who were assigned female at birth are weak.

But evidence doesn’t show that trans women dominate female sports leagues. It turns out, there are shockingly few transgender athletes competing in sports leagues around the United States, and even fewer winning major titles. When the Associated Press conducted an investigation asking lawmakers introducing such sports bills to name trans athletes in their states, most couldn’t point to a single one. After Utah state legislators passed a trans sports ban, Governor Spencer Cox vetoed it, pointing out that, of 75,000 high school kids participating in sports in Utah, there was only a single transgender girl (the state legislature overrode the veto anyway).

California has explicitly protected the rights of trans athletes to compete on sports teams that match their gender identity since 2013. There’s still an underrepresentation of trans athletes in sports participation and titles. This is likely because the deck is stacked against these young people in so many other ways that are unrelated to testosterone levels. Trans youth suffer from high rates of harassment, discrimination, and subsequent anxiety and depression that make it difficult to compete in and excel in sports.

Medical bills

State legislators have introduced bills around the country that would criminalize the provision of gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth. Though such bills are opposed by all major medical organizations (including the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, and the American Psychiatric Association), misinformation continues to spread, and in some instances the bills have become law (though none are currently active due to legal challenges).

Clinicians should be aware that there have been sixteen studies to date, each with unique study designs, that have overall linked gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth to better mental health outcomes. While these interventions do (as with all medications) carry some risks (like delayed bone mineralization with pubertal suppression), the risks must be weighed against potential benefits. Unfortunately, these risks and benefits have not been accurately portrayed in state legislative debates. Politicians have spread a great deal of misinformation about gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth, including false assertions that puberty blockers cause infertility and that most transgender adolescents will grow up to identify as cisgender and regret gender-affirming medical interventions.

Minority stress

These bills have direct consequences for pediatric patients. For example, trans-inclusive bathroom policies are associated with lower rates of sexual assault. However, there are also important indirect effects to consider. The gender minority stress framework explains the ways in which stigmatizing national discourse drives higher rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidality among transgender youth. Under this model, so-called “distal factors” like the recent conversations at the national level that marginalize trans young people, are expected to drive higher rates of adverse mental health outcomes. As transgender youth hear high-profile politicians argue that they’re dangerous to their peers in bathrooms and on sports teams, it’s difficult to imagine their mental health would not worsen. Over time, such “distal factors” also lead to “proximal factors” like internalized transphobia in which youth begin to believe the negative things that are said about them. These dangerous processes can have dramatic negative impacts on self-esteem and emotional development. There is strong precedence that public policies have strong indirect mental health effects on LGBTQ youth.

We’ve entered a dangerous era in which politicians are legislating medical care and other aspects of public policy with the potential to hurt the mental health of our young patients. It’s imperative that clinicians and scientists contact their legislators to make sure they are voting for public policy based on data and fact, not misinformation and political rhetoric. The health of American children depends on it.

Dr. Turban (twitter.com/jack_turban) is a chief fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University.

In 2021, state lawmakers introduced a record number of bills that would affect transgender and gender-diverse people. The vast majority were focused on transgender and gender-diverse youth in particular. We’ve seen bills that would take away gender-affirming medical care for minors, ones that would force trans kids to play on sports teams that don’t match their gender identity, and others that would ban trans kids from public facilities like bathrooms that match their gender identities.

These bills aren’t particularly new, but state lawmakers are putting more energy into them than ever. In response, some public figures have started pushing back. Ariana Grande just pledged to match up to 1.5 million dollars in donations to combat anti–trans youth legislative initiatives. However, doctors have been underrepresented in the political discourse.

Sadly, much of the discussion in this area has been driven by wild speculation and emotional rhetoric. It’s rare that we see actual data brought to the table. As clinicians and scientists, we have a responsibility to highlight the data relevant to these legislative debates, and to share them with our representatives. I’m going to break down what we know quantitatively about each of these issues, so that you’ll feel empowered to bring that information to these debates. My hope is that we can move toward evidence-based public policy instead of rhetoric-based public policy, so that we can ensure the best health possible for young people around the country.

Bathroom bills

Though they’ve been less of a focus recently, politicians for years have argued that trans people should be forced to use bathrooms and other public facilities that match their sex assigned at birth, not their gender identity. Their central argument is that trans-inclusive public facility policies will result in higher rates of assault. Published peer-review data show this isn’t true. A 2019 study in Sexuality Research and Social Policy examined the impacts of trans-inclusive public facility policies and found they resulted in no increase in assaults among the general (mostly cisgender) population. Another 2019 study in Pediatrics found that trans-inclusive facility policies were associated with lower odds of sexual assault victimization against transgender youth. The myth that trans-inclusive public facilities increase assault risk is simply that: a myth. All existing data indicate that trans-inclusive policies will improve public safety.

Sports bills

One of the hottest debates recently involves whether transgender girls should be allowed to participate in girls’ sports teams. Those in favor of these bills argue that transgender girls have an innate biological sports advantage over cisgender girls, and if allowed to compete in girls’ sports leagues, they will dominate the events, and cisgender girls will no longer win sports titles. The bills feed into longstanding assumptions – those who were assigned male at birth are strong, and those who were assigned female at birth are weak.

But evidence doesn’t show that trans women dominate female sports leagues. It turns out, there are shockingly few transgender athletes competing in sports leagues around the United States, and even fewer winning major titles. When the Associated Press conducted an investigation asking lawmakers introducing such sports bills to name trans athletes in their states, most couldn’t point to a single one. After Utah state legislators passed a trans sports ban, Governor Spencer Cox vetoed it, pointing out that, of 75,000 high school kids participating in sports in Utah, there was only a single transgender girl (the state legislature overrode the veto anyway).

California has explicitly protected the rights of trans athletes to compete on sports teams that match their gender identity since 2013. There’s still an underrepresentation of trans athletes in sports participation and titles. This is likely because the deck is stacked against these young people in so many other ways that are unrelated to testosterone levels. Trans youth suffer from high rates of harassment, discrimination, and subsequent anxiety and depression that make it difficult to compete in and excel in sports.

Medical bills

State legislators have introduced bills around the country that would criminalize the provision of gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth. Though such bills are opposed by all major medical organizations (including the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, and the American Psychiatric Association), misinformation continues to spread, and in some instances the bills have become law (though none are currently active due to legal challenges).

Clinicians should be aware that there have been sixteen studies to date, each with unique study designs, that have overall linked gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth to better mental health outcomes. While these interventions do (as with all medications) carry some risks (like delayed bone mineralization with pubertal suppression), the risks must be weighed against potential benefits. Unfortunately, these risks and benefits have not been accurately portrayed in state legislative debates. Politicians have spread a great deal of misinformation about gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth, including false assertions that puberty blockers cause infertility and that most transgender adolescents will grow up to identify as cisgender and regret gender-affirming medical interventions.

Minority stress

These bills have direct consequences for pediatric patients. For example, trans-inclusive bathroom policies are associated with lower rates of sexual assault. However, there are also important indirect effects to consider. The gender minority stress framework explains the ways in which stigmatizing national discourse drives higher rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidality among transgender youth. Under this model, so-called “distal factors” like the recent conversations at the national level that marginalize trans young people, are expected to drive higher rates of adverse mental health outcomes. As transgender youth hear high-profile politicians argue that they’re dangerous to their peers in bathrooms and on sports teams, it’s difficult to imagine their mental health would not worsen. Over time, such “distal factors” also lead to “proximal factors” like internalized transphobia in which youth begin to believe the negative things that are said about them. These dangerous processes can have dramatic negative impacts on self-esteem and emotional development. There is strong precedence that public policies have strong indirect mental health effects on LGBTQ youth.

We’ve entered a dangerous era in which politicians are legislating medical care and other aspects of public policy with the potential to hurt the mental health of our young patients. It’s imperative that clinicians and scientists contact their legislators to make sure they are voting for public policy based on data and fact, not misinformation and political rhetoric. The health of American children depends on it.

Dr. Turban (twitter.com/jack_turban) is a chief fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University.

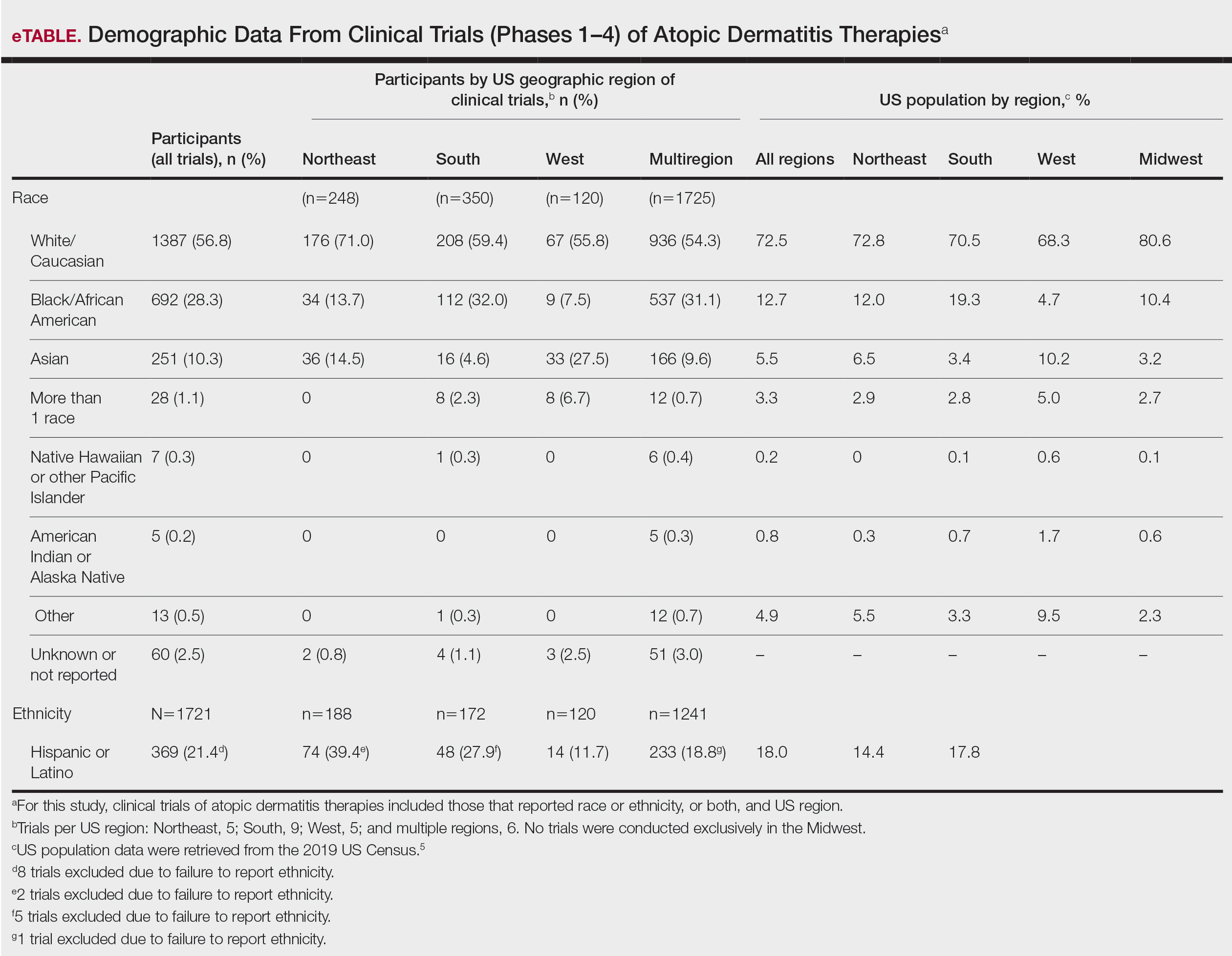

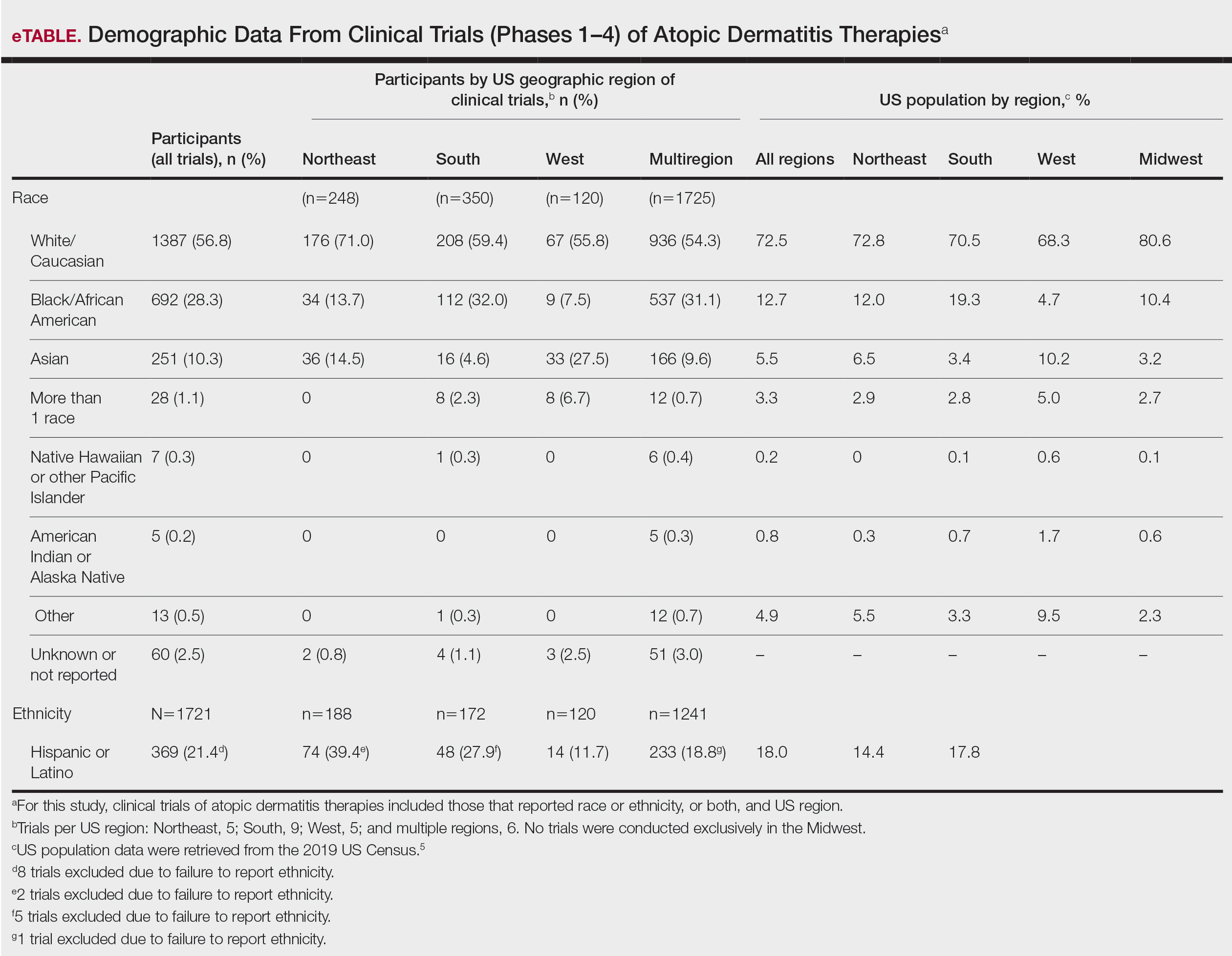

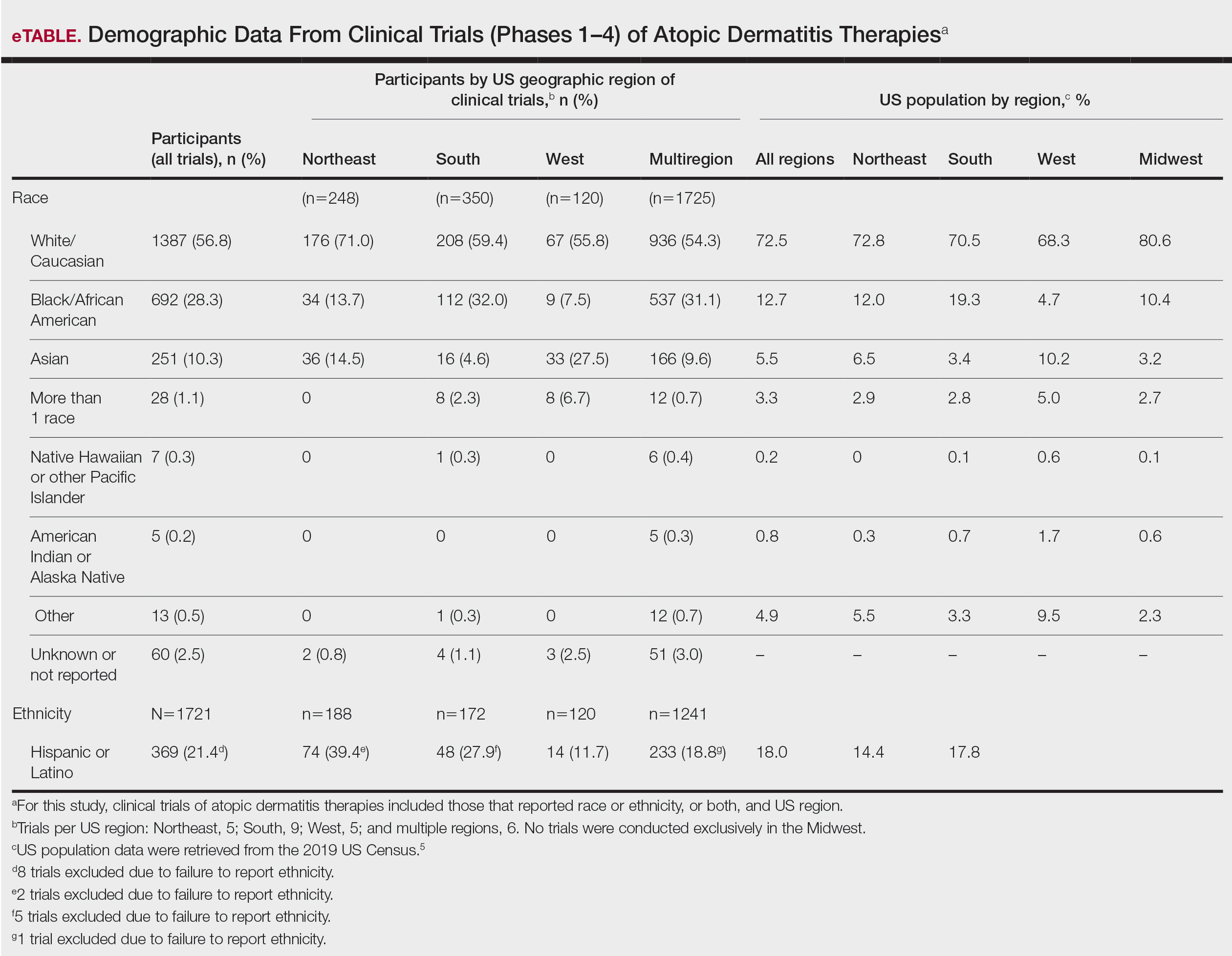

Review of Ethnoracial Representation in Clinical Trials (Phases 1 Through 4) of Atopic Dermatitis Therapies

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) affects an estimated 7.2% of adults and 10.7% of children in the United States; however, AD might affect different races at a varying rate.1 Compared to their European American counterparts, Asian/Pacific Islanders and African Americans are 7 and 3 times more likely, respectively, to be given a diagnosis of AD.2

Despite being disproportionately affected by AD, minority groups might be underrepresented in clinical trials of AD treatments.3 One explanation for this imbalance might be that ethnoracial representation differs across regions in the United States, perhaps in regions where clinical trials are conducted. Price et al3 investigated racial representation in clinical trials of AD globally and found that patients of color are consistently underrepresented.

Research on racial representation in clinical trials within the United States—on national and regional scales—is lacking from the current AD literature. We conducted a study to compare racial and ethnic disparities in AD clinical trials across regions of the United States.