User login

Pediatricians at odds over gender-affirming care for trans kids

Some members of the American Academy of Pediatrics say its association leadership is blocking discussion about a resolution asking for a “rigorous systematic review” of gender-affirming care guidelines.

At issue is 2018 guidance that states children can undergo hormonal therapy after they are deemed appropriate candidates following a thorough mental health evaluation.

Critics say minors under age 18 may be getting “fast-tracked” to hormonal treatment too quickly or inappropriately and can end up regretting the decision and facing medical conditions like sterility.

Five AAP members, which has a total membership of around 67,000 pediatricians in the United States and Canada, this year penned Resolution 27, calling for a possible update of the guidelines following consultation with stakeholders that include mental health and medical clinicians, parents, and patients “with diverse views and experiences.”

Those members and others in written comments on a members-only website accuse the AAP of deliberately silencing debate on the issue and changing resolution rules. Any AAP member can submit a resolution for consideration by the group’s leadership at its annual policy meeting.

This year, the AAP sent an email to members stating it would not allow comments on resolutions that had not been “sponsored” by one of the group’s 66 chapters or 88 internal committees, councils, or sections.

That’s why comments were not allowed on Resolution 27, said Mark Del Monte, the AAP’s CEO. A second attempt to get sponsorship during the annual leadership forum, held earlier this month in Chicago, also failed, he noted. Mr. Del Monte told this news organization that changes to the resolution process are made every year and that no rule changes were directly associated with Resolution 27.

But one of the resolution’s authors said there was sponsorship when members first drafted the suggestion. Julia Mason, MD, a board member for the Society for Evidence-based Gender Medicine and a pediatrician in private practice in Gresham, Ore., says an AAP chapter president agreed to second Resolution 27 but backed off after attending a different AAP meeting. Dr. Mason did not name the member.

On Aug. 10, AAP President Moira Szilagyi, MD, PhD, wrote in a blog on the AAP website – after the AAP leadership meeting in Chicago – that the lack of sponsorship “meant no one was willing to support their proposal.”

The AAP Leadership Council’s 154 voting entities approved 48 resolutions at the meeting, all of which will be referred to the AAP Board of Directors for potential, but not definite, action as the Board only takes resolutions under advisement, Mr. Del Monte notes.

In an email allowing members to comment on a resolution (number 28) regarding education support for caring for transgender patients, 23 chose to support Resolution 27 instead.

“I am wholeheartedly in support of Resolution 27, which interestingly has been removed from the list of resolutions for member comment,” one comment read. “I can no longer trust the AAP to provide medical evidence-based education with regard to care for transgender individuals.”

“We don’t need a formal resolution to look at the evidence around the care of transgender young people. Evaluating the evidence behind our recommendations, which the unsponsored resolution called for, is a routine part of the Academy’s policy-writing process,” wrote Dr. Szilagyi in her blog.

Mr. Del Monte says that “the 2018 policy is under review now.”

So far, “the evidence that we have seen reinforces our policy that gender-affirming care is the correct approach,” Mr. Del Monte stresses. “It is supported by every mainstream medical society in the world and is the standard of care,” he maintains.

Among those societies is the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, which in the draft of its latest Standards of Care (SOC8) – the first new guidance on the issue for 10 years – reportedly lowers the age for “top surgery” to 15 years.

The final SOC8 will most likely be published to coincide with WPATH’s annual meeting in September in Montreal.

Opponents plan to protest outside the AAP’s annual meeting, in Anaheim in October, Dr. Mason says.

“I’m concerned that kids with a transient gender identity are being funneled into medicalization that does not serve them,” Dr. Mason says. “I am worried that the trans identity is valued over the possibility of desistance,” she adds, admitting that her goal is to have fewer children transition gender.

Last summer, AAP found itself in hot water on the same topic when it barred SEGM from having a booth at the AAP annual meeting in 2021, as reported by this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some members of the American Academy of Pediatrics say its association leadership is blocking discussion about a resolution asking for a “rigorous systematic review” of gender-affirming care guidelines.

At issue is 2018 guidance that states children can undergo hormonal therapy after they are deemed appropriate candidates following a thorough mental health evaluation.

Critics say minors under age 18 may be getting “fast-tracked” to hormonal treatment too quickly or inappropriately and can end up regretting the decision and facing medical conditions like sterility.

Five AAP members, which has a total membership of around 67,000 pediatricians in the United States and Canada, this year penned Resolution 27, calling for a possible update of the guidelines following consultation with stakeholders that include mental health and medical clinicians, parents, and patients “with diverse views and experiences.”

Those members and others in written comments on a members-only website accuse the AAP of deliberately silencing debate on the issue and changing resolution rules. Any AAP member can submit a resolution for consideration by the group’s leadership at its annual policy meeting.

This year, the AAP sent an email to members stating it would not allow comments on resolutions that had not been “sponsored” by one of the group’s 66 chapters or 88 internal committees, councils, or sections.

That’s why comments were not allowed on Resolution 27, said Mark Del Monte, the AAP’s CEO. A second attempt to get sponsorship during the annual leadership forum, held earlier this month in Chicago, also failed, he noted. Mr. Del Monte told this news organization that changes to the resolution process are made every year and that no rule changes were directly associated with Resolution 27.

But one of the resolution’s authors said there was sponsorship when members first drafted the suggestion. Julia Mason, MD, a board member for the Society for Evidence-based Gender Medicine and a pediatrician in private practice in Gresham, Ore., says an AAP chapter president agreed to second Resolution 27 but backed off after attending a different AAP meeting. Dr. Mason did not name the member.

On Aug. 10, AAP President Moira Szilagyi, MD, PhD, wrote in a blog on the AAP website – after the AAP leadership meeting in Chicago – that the lack of sponsorship “meant no one was willing to support their proposal.”

The AAP Leadership Council’s 154 voting entities approved 48 resolutions at the meeting, all of which will be referred to the AAP Board of Directors for potential, but not definite, action as the Board only takes resolutions under advisement, Mr. Del Monte notes.

In an email allowing members to comment on a resolution (number 28) regarding education support for caring for transgender patients, 23 chose to support Resolution 27 instead.

“I am wholeheartedly in support of Resolution 27, which interestingly has been removed from the list of resolutions for member comment,” one comment read. “I can no longer trust the AAP to provide medical evidence-based education with regard to care for transgender individuals.”

“We don’t need a formal resolution to look at the evidence around the care of transgender young people. Evaluating the evidence behind our recommendations, which the unsponsored resolution called for, is a routine part of the Academy’s policy-writing process,” wrote Dr. Szilagyi in her blog.

Mr. Del Monte says that “the 2018 policy is under review now.”

So far, “the evidence that we have seen reinforces our policy that gender-affirming care is the correct approach,” Mr. Del Monte stresses. “It is supported by every mainstream medical society in the world and is the standard of care,” he maintains.

Among those societies is the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, which in the draft of its latest Standards of Care (SOC8) – the first new guidance on the issue for 10 years – reportedly lowers the age for “top surgery” to 15 years.

The final SOC8 will most likely be published to coincide with WPATH’s annual meeting in September in Montreal.

Opponents plan to protest outside the AAP’s annual meeting, in Anaheim in October, Dr. Mason says.

“I’m concerned that kids with a transient gender identity are being funneled into medicalization that does not serve them,” Dr. Mason says. “I am worried that the trans identity is valued over the possibility of desistance,” she adds, admitting that her goal is to have fewer children transition gender.

Last summer, AAP found itself in hot water on the same topic when it barred SEGM from having a booth at the AAP annual meeting in 2021, as reported by this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some members of the American Academy of Pediatrics say its association leadership is blocking discussion about a resolution asking for a “rigorous systematic review” of gender-affirming care guidelines.

At issue is 2018 guidance that states children can undergo hormonal therapy after they are deemed appropriate candidates following a thorough mental health evaluation.

Critics say minors under age 18 may be getting “fast-tracked” to hormonal treatment too quickly or inappropriately and can end up regretting the decision and facing medical conditions like sterility.

Five AAP members, which has a total membership of around 67,000 pediatricians in the United States and Canada, this year penned Resolution 27, calling for a possible update of the guidelines following consultation with stakeholders that include mental health and medical clinicians, parents, and patients “with diverse views and experiences.”

Those members and others in written comments on a members-only website accuse the AAP of deliberately silencing debate on the issue and changing resolution rules. Any AAP member can submit a resolution for consideration by the group’s leadership at its annual policy meeting.

This year, the AAP sent an email to members stating it would not allow comments on resolutions that had not been “sponsored” by one of the group’s 66 chapters or 88 internal committees, councils, or sections.

That’s why comments were not allowed on Resolution 27, said Mark Del Monte, the AAP’s CEO. A second attempt to get sponsorship during the annual leadership forum, held earlier this month in Chicago, also failed, he noted. Mr. Del Monte told this news organization that changes to the resolution process are made every year and that no rule changes were directly associated with Resolution 27.

But one of the resolution’s authors said there was sponsorship when members first drafted the suggestion. Julia Mason, MD, a board member for the Society for Evidence-based Gender Medicine and a pediatrician in private practice in Gresham, Ore., says an AAP chapter president agreed to second Resolution 27 but backed off after attending a different AAP meeting. Dr. Mason did not name the member.

On Aug. 10, AAP President Moira Szilagyi, MD, PhD, wrote in a blog on the AAP website – after the AAP leadership meeting in Chicago – that the lack of sponsorship “meant no one was willing to support their proposal.”

The AAP Leadership Council’s 154 voting entities approved 48 resolutions at the meeting, all of which will be referred to the AAP Board of Directors for potential, but not definite, action as the Board only takes resolutions under advisement, Mr. Del Monte notes.

In an email allowing members to comment on a resolution (number 28) regarding education support for caring for transgender patients, 23 chose to support Resolution 27 instead.

“I am wholeheartedly in support of Resolution 27, which interestingly has been removed from the list of resolutions for member comment,” one comment read. “I can no longer trust the AAP to provide medical evidence-based education with regard to care for transgender individuals.”

“We don’t need a formal resolution to look at the evidence around the care of transgender young people. Evaluating the evidence behind our recommendations, which the unsponsored resolution called for, is a routine part of the Academy’s policy-writing process,” wrote Dr. Szilagyi in her blog.

Mr. Del Monte says that “the 2018 policy is under review now.”

So far, “the evidence that we have seen reinforces our policy that gender-affirming care is the correct approach,” Mr. Del Monte stresses. “It is supported by every mainstream medical society in the world and is the standard of care,” he maintains.

Among those societies is the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, which in the draft of its latest Standards of Care (SOC8) – the first new guidance on the issue for 10 years – reportedly lowers the age for “top surgery” to 15 years.

The final SOC8 will most likely be published to coincide with WPATH’s annual meeting in September in Montreal.

Opponents plan to protest outside the AAP’s annual meeting, in Anaheim in October, Dr. Mason says.

“I’m concerned that kids with a transient gender identity are being funneled into medicalization that does not serve them,” Dr. Mason says. “I am worried that the trans identity is valued over the possibility of desistance,” she adds, admitting that her goal is to have fewer children transition gender.

Last summer, AAP found itself in hot water on the same topic when it barred SEGM from having a booth at the AAP annual meeting in 2021, as reported by this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women are underrepresented on rheumatology journal editorial boards

Only 21% of rheumatology journals showed gender-balanced editorial boards, defined as 40%-60% women members, based on data from 34 publications.

Women remain underrepresented on the editorial boards of medical journals in general, and rheumatology journals are no exception, according to Pavel V. Ovseiko, DPhil, of the University of Oxford (England) and colleagues.

“Gender representation on editorial boards matters because editorships-in-chief and editorial board memberships are prestigious roles that increase the visibility of role-holders and provide opportunities to influence research and practice through agenda setting, editorial decision making, and peer review,” the researchers wrote.

In a study published in The Lancet Rheumatology, the researchers examined the websites of 34 rheumatology publications in December 2021. The gender of the board members was estimated using a name-to-gender inference platform and checked against personal pronouns and photos used online.

Overall, six journals (15%) had female editors-in-chief or the equivalent, and 27% of the total editorial board members were women.

Occupation had a significant impact on gender representation. Gender was equally balanced (50%) for the four journals in which a publishing professional served as editor-in-chief, and women comprised 74% of the editorial board memberships held by publishing professionals.

However, women comprised only 11% of editorships and 26% of editorial board memberships held by academics or clinicians.

“Although academic rheumatology is male-dominated, academic publishing is female-dominated,” the researchers wrote.

Gender equity is important for rheumatology in part because most rheumatology patients are women, and the proportion of women in rheumatology is increasing in many countries, the researchers noted.

“Greater diversity on editorial boards is likely to have a positive effect on the quality of science through adequate consideration and reporting of sex-related and gender-related variables,” they said.

The seven journals with gender-balanced editorial boards were Acta Reumatologica Portuguesa, Arthritis & Rheumatology, Arthritis Care & Research, The Lancet Rheumatology, Lupus Science & Medicine, Nature Reviews Rheumatology, and Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism.

To achieve gender balance and diversity on editorial boards, the researchers offered strategies including advertising openings through open calls, establishing and monitoring gender diversity targets, and limiting editorial board appointments to fixed terms.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose, but several serve on the editorial boards of various rheumatology journals.

Only 21% of rheumatology journals showed gender-balanced editorial boards, defined as 40%-60% women members, based on data from 34 publications.

Women remain underrepresented on the editorial boards of medical journals in general, and rheumatology journals are no exception, according to Pavel V. Ovseiko, DPhil, of the University of Oxford (England) and colleagues.

“Gender representation on editorial boards matters because editorships-in-chief and editorial board memberships are prestigious roles that increase the visibility of role-holders and provide opportunities to influence research and practice through agenda setting, editorial decision making, and peer review,” the researchers wrote.

In a study published in The Lancet Rheumatology, the researchers examined the websites of 34 rheumatology publications in December 2021. The gender of the board members was estimated using a name-to-gender inference platform and checked against personal pronouns and photos used online.

Overall, six journals (15%) had female editors-in-chief or the equivalent, and 27% of the total editorial board members were women.

Occupation had a significant impact on gender representation. Gender was equally balanced (50%) for the four journals in which a publishing professional served as editor-in-chief, and women comprised 74% of the editorial board memberships held by publishing professionals.

However, women comprised only 11% of editorships and 26% of editorial board memberships held by academics or clinicians.

“Although academic rheumatology is male-dominated, academic publishing is female-dominated,” the researchers wrote.

Gender equity is important for rheumatology in part because most rheumatology patients are women, and the proportion of women in rheumatology is increasing in many countries, the researchers noted.

“Greater diversity on editorial boards is likely to have a positive effect on the quality of science through adequate consideration and reporting of sex-related and gender-related variables,” they said.

The seven journals with gender-balanced editorial boards were Acta Reumatologica Portuguesa, Arthritis & Rheumatology, Arthritis Care & Research, The Lancet Rheumatology, Lupus Science & Medicine, Nature Reviews Rheumatology, and Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism.

To achieve gender balance and diversity on editorial boards, the researchers offered strategies including advertising openings through open calls, establishing and monitoring gender diversity targets, and limiting editorial board appointments to fixed terms.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose, but several serve on the editorial boards of various rheumatology journals.

Only 21% of rheumatology journals showed gender-balanced editorial boards, defined as 40%-60% women members, based on data from 34 publications.

Women remain underrepresented on the editorial boards of medical journals in general, and rheumatology journals are no exception, according to Pavel V. Ovseiko, DPhil, of the University of Oxford (England) and colleagues.

“Gender representation on editorial boards matters because editorships-in-chief and editorial board memberships are prestigious roles that increase the visibility of role-holders and provide opportunities to influence research and practice through agenda setting, editorial decision making, and peer review,” the researchers wrote.

In a study published in The Lancet Rheumatology, the researchers examined the websites of 34 rheumatology publications in December 2021. The gender of the board members was estimated using a name-to-gender inference platform and checked against personal pronouns and photos used online.

Overall, six journals (15%) had female editors-in-chief or the equivalent, and 27% of the total editorial board members were women.

Occupation had a significant impact on gender representation. Gender was equally balanced (50%) for the four journals in which a publishing professional served as editor-in-chief, and women comprised 74% of the editorial board memberships held by publishing professionals.

However, women comprised only 11% of editorships and 26% of editorial board memberships held by academics or clinicians.

“Although academic rheumatology is male-dominated, academic publishing is female-dominated,” the researchers wrote.

Gender equity is important for rheumatology in part because most rheumatology patients are women, and the proportion of women in rheumatology is increasing in many countries, the researchers noted.

“Greater diversity on editorial boards is likely to have a positive effect on the quality of science through adequate consideration and reporting of sex-related and gender-related variables,” they said.

The seven journals with gender-balanced editorial boards were Acta Reumatologica Portuguesa, Arthritis & Rheumatology, Arthritis Care & Research, The Lancet Rheumatology, Lupus Science & Medicine, Nature Reviews Rheumatology, and Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism.

To achieve gender balance and diversity on editorial boards, the researchers offered strategies including advertising openings through open calls, establishing and monitoring gender diversity targets, and limiting editorial board appointments to fixed terms.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose, but several serve on the editorial boards of various rheumatology journals.

FROM THE LANCET RHEUMATOLOGY

Low-level light therapy cap shows subtle effects on CCCA

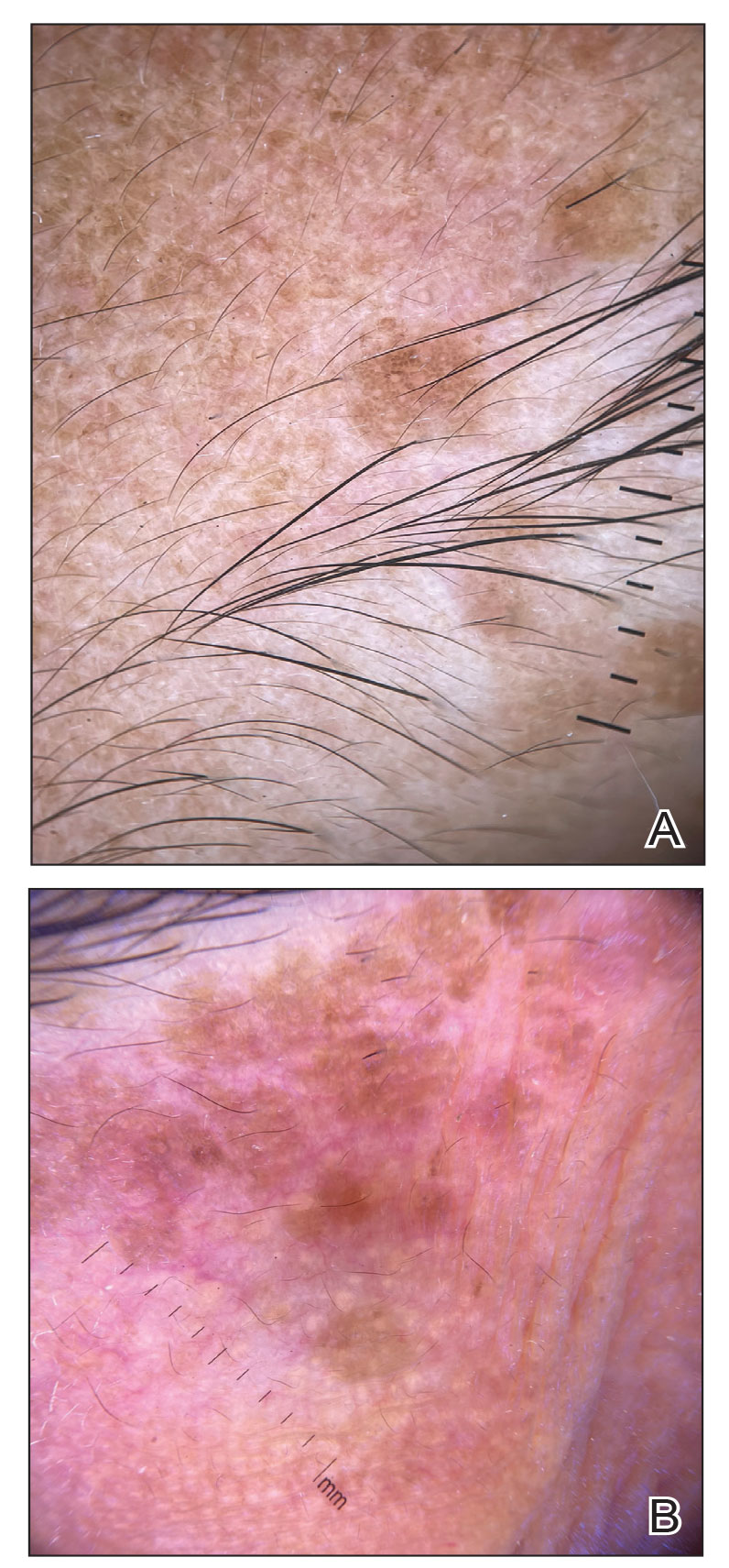

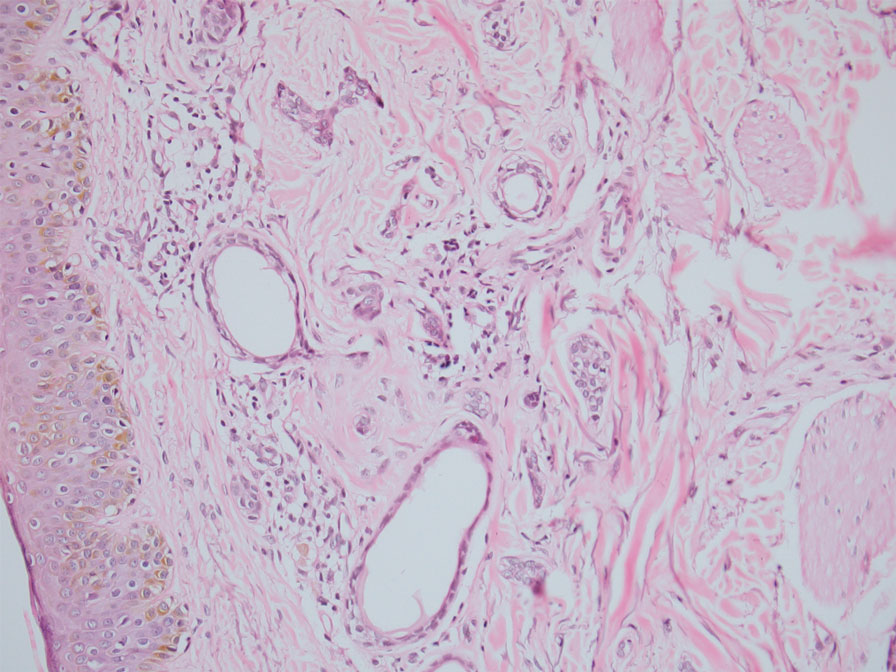

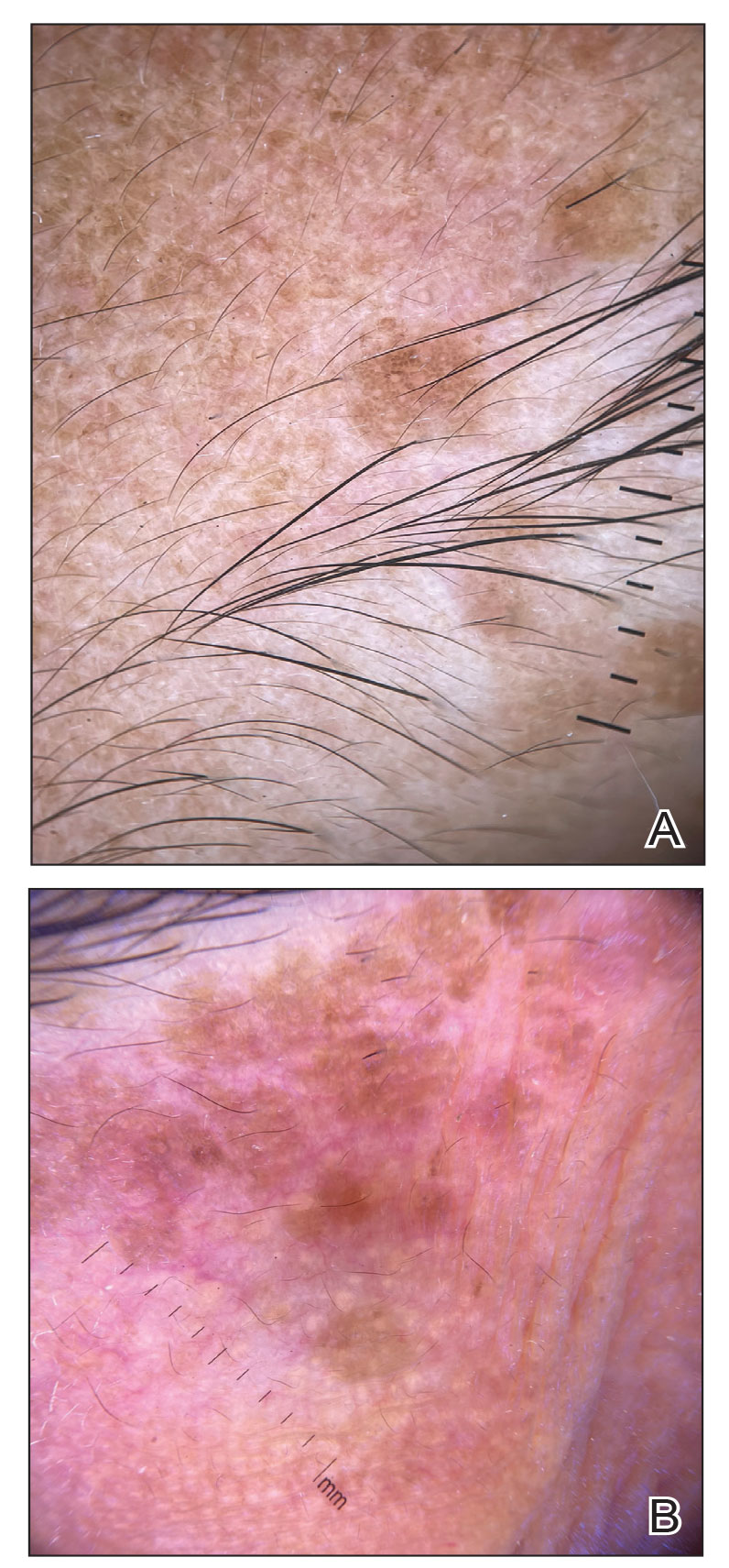

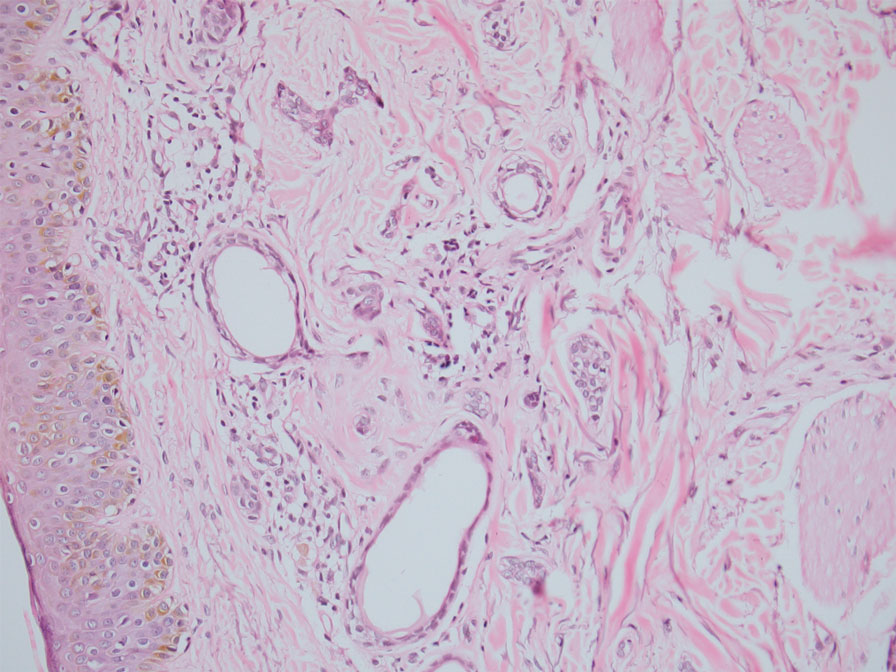

though the treatment effects from a small prospective trial appear to be subtle.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) is a form of scarring hair loss with unknown etiology and no known cure that affects mainly women of African descent.

“The low-level light therapy (LLLT) cap does indeed seem to help with symptoms and mild regrowth in CCCA,” senior study author Amy J. McMichael, MD, told this news organization. “The dual-wavelength cap we used appears to have anti-inflammatory properties, and that makes sense for a primarily inflammatory scarring from of alopecia.

“Quality of life improved with the treatment and there were no reported side effects,” added Dr. McMichael, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

The results of the study were presented in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

The REVIAN RED cap (REVIAN Inc.) used in the study contains 119 light-emitting diodes (LEDs) arrayed on the cap’s interior surface that emit orange (620 nm) and red (660 nm) light.

The hypothesis for how the dual-wavelength lights work is that light is absorbed by the chromophore cytochrome c oxidase in the mitochondrial membrane. This induces the release of nitric oxide and the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which leads to vasodilation, cytokine regulation, and increased transcription and release of growth factors.

LLLT is approved to treat androgenetic alopecia, the authors wrote, but has not been studied as a treatment for CCCA.

To assess the effects of LLLT on CCCA, Dr. McMichael and her colleagues at Wake Forest followed the condition’s progress in five Black women over their 6-month course of treatment. Four participants completed the study.

At baseline, all participants had been on individual stable CCCA treatment regimens for at least 3 months. They continued those treatments along with LLLT therapy throughout the study. The women ranged in age from 38 to 69 years, had had CCCA for an average of 12 years, and their disease severity ranged from stage IIB to IVA.

They were instructed to wear the REVIAN RED cap with the LEDs activated for 10 minutes each day.

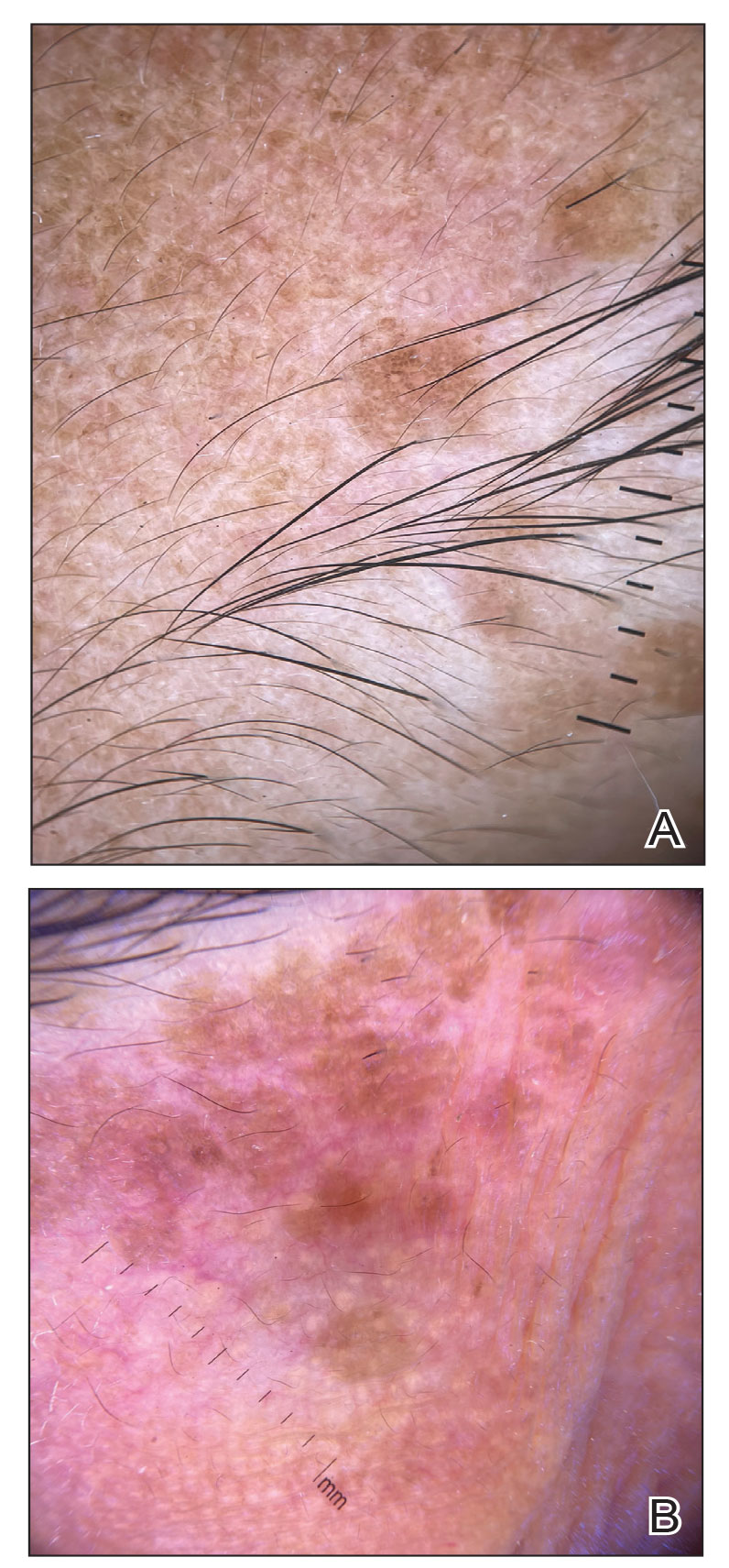

At 2, 4, and 6 months, participants self-assessed their symptoms, a clinician evaluated the condition’s severity, and digital photographs were taken.

At 6 months:

- Three patients showed improved Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).

- Three patients showed decreased loss of follicular openings and breakage.

- A dermoscopic image of the scalp of one patient revealed short, regrowing vellus hairs and minimal interfollicular and perifollicular scale.

- No patients reported side effects.

Small study raises big questions

“I hope this study will lead to a larger study that will look at the long-term outcomes of CCCA,” Dr. McMichael said. “This is a nice treatment that does not require application of something to the scalp that may affect hair styling, and it has no systemic side effects.”

Dr. McMichael acknowledges that the small sample size, participants continuing with their individual stable treatments while also undergoing light therapy, and the lack of patients with stage I disease, are weaknesses in the study.

“However, the strength is that none of the patients had side effects or stopped using the treatment due to difficulty with the system,” she added.

Dr. McMichael said she would like to investigate the effects of longer use of the cap and whether the cap can be used to prevent CCCA.

Chesahna Kindred, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at Howard University, Washington, D.C., and founder of Kindred Hair & Skin Center in Columbia, Md., told this news organization that she uses LLLT in her practice.

“I find that LLLT is mildly helpful, or at least does not worsen, androgenetic alopecia,” she said.

“Interestingly, while all four patients had stable disease upon initiating the study, it appears as though two of the four worsened after the use of LLLT, one improved, and one remained relatively stable,” noted Dr. Kindred, who was not involved in the study. “This is important because once there is complete destruction of the follicle, CCCA is difficult to improve.

“Given that there are several options to address inflammation and follicular damage in CCCA, more studies are needed before I would incorporate LLLT into my regular treatment algorithms,” she added.

“Studies like this are important and remind us to not lump all forms of hair loss together,” she said.

REVIAN Inc. provided the caps, but the study received no additional funding. Dr. McMichael and Dr. Kindred report relevant financial relationships with the pharmaceutical industry. Study coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

though the treatment effects from a small prospective trial appear to be subtle.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) is a form of scarring hair loss with unknown etiology and no known cure that affects mainly women of African descent.

“The low-level light therapy (LLLT) cap does indeed seem to help with symptoms and mild regrowth in CCCA,” senior study author Amy J. McMichael, MD, told this news organization. “The dual-wavelength cap we used appears to have anti-inflammatory properties, and that makes sense for a primarily inflammatory scarring from of alopecia.

“Quality of life improved with the treatment and there were no reported side effects,” added Dr. McMichael, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

The results of the study were presented in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

The REVIAN RED cap (REVIAN Inc.) used in the study contains 119 light-emitting diodes (LEDs) arrayed on the cap’s interior surface that emit orange (620 nm) and red (660 nm) light.

The hypothesis for how the dual-wavelength lights work is that light is absorbed by the chromophore cytochrome c oxidase in the mitochondrial membrane. This induces the release of nitric oxide and the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which leads to vasodilation, cytokine regulation, and increased transcription and release of growth factors.

LLLT is approved to treat androgenetic alopecia, the authors wrote, but has not been studied as a treatment for CCCA.

To assess the effects of LLLT on CCCA, Dr. McMichael and her colleagues at Wake Forest followed the condition’s progress in five Black women over their 6-month course of treatment. Four participants completed the study.

At baseline, all participants had been on individual stable CCCA treatment regimens for at least 3 months. They continued those treatments along with LLLT therapy throughout the study. The women ranged in age from 38 to 69 years, had had CCCA for an average of 12 years, and their disease severity ranged from stage IIB to IVA.

They were instructed to wear the REVIAN RED cap with the LEDs activated for 10 minutes each day.

At 2, 4, and 6 months, participants self-assessed their symptoms, a clinician evaluated the condition’s severity, and digital photographs were taken.

At 6 months:

- Three patients showed improved Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).

- Three patients showed decreased loss of follicular openings and breakage.

- A dermoscopic image of the scalp of one patient revealed short, regrowing vellus hairs and minimal interfollicular and perifollicular scale.

- No patients reported side effects.

Small study raises big questions

“I hope this study will lead to a larger study that will look at the long-term outcomes of CCCA,” Dr. McMichael said. “This is a nice treatment that does not require application of something to the scalp that may affect hair styling, and it has no systemic side effects.”

Dr. McMichael acknowledges that the small sample size, participants continuing with their individual stable treatments while also undergoing light therapy, and the lack of patients with stage I disease, are weaknesses in the study.

“However, the strength is that none of the patients had side effects or stopped using the treatment due to difficulty with the system,” she added.

Dr. McMichael said she would like to investigate the effects of longer use of the cap and whether the cap can be used to prevent CCCA.

Chesahna Kindred, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at Howard University, Washington, D.C., and founder of Kindred Hair & Skin Center in Columbia, Md., told this news organization that she uses LLLT in her practice.

“I find that LLLT is mildly helpful, or at least does not worsen, androgenetic alopecia,” she said.

“Interestingly, while all four patients had stable disease upon initiating the study, it appears as though two of the four worsened after the use of LLLT, one improved, and one remained relatively stable,” noted Dr. Kindred, who was not involved in the study. “This is important because once there is complete destruction of the follicle, CCCA is difficult to improve.

“Given that there are several options to address inflammation and follicular damage in CCCA, more studies are needed before I would incorporate LLLT into my regular treatment algorithms,” she added.

“Studies like this are important and remind us to not lump all forms of hair loss together,” she said.

REVIAN Inc. provided the caps, but the study received no additional funding. Dr. McMichael and Dr. Kindred report relevant financial relationships with the pharmaceutical industry. Study coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

though the treatment effects from a small prospective trial appear to be subtle.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) is a form of scarring hair loss with unknown etiology and no known cure that affects mainly women of African descent.

“The low-level light therapy (LLLT) cap does indeed seem to help with symptoms and mild regrowth in CCCA,” senior study author Amy J. McMichael, MD, told this news organization. “The dual-wavelength cap we used appears to have anti-inflammatory properties, and that makes sense for a primarily inflammatory scarring from of alopecia.

“Quality of life improved with the treatment and there were no reported side effects,” added Dr. McMichael, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

The results of the study were presented in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

The REVIAN RED cap (REVIAN Inc.) used in the study contains 119 light-emitting diodes (LEDs) arrayed on the cap’s interior surface that emit orange (620 nm) and red (660 nm) light.

The hypothesis for how the dual-wavelength lights work is that light is absorbed by the chromophore cytochrome c oxidase in the mitochondrial membrane. This induces the release of nitric oxide and the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which leads to vasodilation, cytokine regulation, and increased transcription and release of growth factors.

LLLT is approved to treat androgenetic alopecia, the authors wrote, but has not been studied as a treatment for CCCA.

To assess the effects of LLLT on CCCA, Dr. McMichael and her colleagues at Wake Forest followed the condition’s progress in five Black women over their 6-month course of treatment. Four participants completed the study.

At baseline, all participants had been on individual stable CCCA treatment regimens for at least 3 months. They continued those treatments along with LLLT therapy throughout the study. The women ranged in age from 38 to 69 years, had had CCCA for an average of 12 years, and their disease severity ranged from stage IIB to IVA.

They were instructed to wear the REVIAN RED cap with the LEDs activated for 10 minutes each day.

At 2, 4, and 6 months, participants self-assessed their symptoms, a clinician evaluated the condition’s severity, and digital photographs were taken.

At 6 months:

- Three patients showed improved Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).

- Three patients showed decreased loss of follicular openings and breakage.

- A dermoscopic image of the scalp of one patient revealed short, regrowing vellus hairs and minimal interfollicular and perifollicular scale.

- No patients reported side effects.

Small study raises big questions

“I hope this study will lead to a larger study that will look at the long-term outcomes of CCCA,” Dr. McMichael said. “This is a nice treatment that does not require application of something to the scalp that may affect hair styling, and it has no systemic side effects.”

Dr. McMichael acknowledges that the small sample size, participants continuing with their individual stable treatments while also undergoing light therapy, and the lack of patients with stage I disease, are weaknesses in the study.

“However, the strength is that none of the patients had side effects or stopped using the treatment due to difficulty with the system,” she added.

Dr. McMichael said she would like to investigate the effects of longer use of the cap and whether the cap can be used to prevent CCCA.

Chesahna Kindred, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at Howard University, Washington, D.C., and founder of Kindred Hair & Skin Center in Columbia, Md., told this news organization that she uses LLLT in her practice.

“I find that LLLT is mildly helpful, or at least does not worsen, androgenetic alopecia,” she said.

“Interestingly, while all four patients had stable disease upon initiating the study, it appears as though two of the four worsened after the use of LLLT, one improved, and one remained relatively stable,” noted Dr. Kindred, who was not involved in the study. “This is important because once there is complete destruction of the follicle, CCCA is difficult to improve.

“Given that there are several options to address inflammation and follicular damage in CCCA, more studies are needed before I would incorporate LLLT into my regular treatment algorithms,” she added.

“Studies like this are important and remind us to not lump all forms of hair loss together,” she said.

REVIAN Inc. provided the caps, but the study received no additional funding. Dr. McMichael and Dr. Kindred report relevant financial relationships with the pharmaceutical industry. Study coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SID 2022

Racial Disparities in the Diagnosis of Psoriasis

To the Editor:

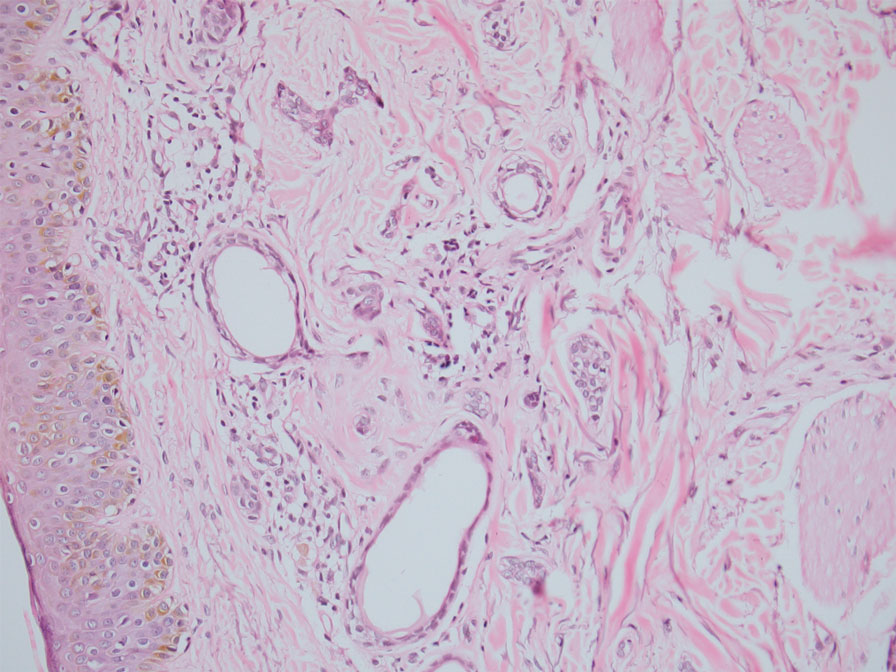

Psoriasis affects 2% to 3% of the US population and is one of the more commonly diagnosed dermatologic conditions.1-3 Experts agree that common cutaneous diseases such as psoriasis present differently in patients with skin of color (SOC) compared to non-SOC patients.3,4 Despite the prevalence of psoriasis, data on these morphologic differences are limited.3-5 We performed a retrospective chart review comparing characteristics of psoriasis in SOC and non-SOC patients.

Through a search of electronic health records, we identified patients with an International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, diagnosis of psoriasis who were 18 years or older and were evaluated in the dermatology department between August 2015 and June 2020 at University Medical Center, an academic institution in New Orleans, Louisiana. Photographs and descriptions of lesions from these patients were reviewed. Patient data collected included age, sex, psoriasis classification, insurance status, self-identified race and ethnicity, location of lesion(s), biopsy, final diagnosis, and average number of visits or days required for accurate diagnosis. Self-identified SOC race and ethnicity categories included Black or African American, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian and Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, and “other.”

All analyses were conducted using R-4.0.1 statistics software. Categorical variables were compared in SOC and non-SOC groups using Fisher exact tests. Continuous covariates were conducted using a Wilcoxon rank sum test.

In total, we reviewed 557 charts. Four patients who declined to identify their race or ethnicity were excluded, yielding 286 SOC and 267 non-SOC patients (N=553). A total of 276 patients (131 SOC; 145 non-SOC) with a prior diagnosis of psoriasis were excluded in the days to diagnosis analysis. Twenty patients (15, SOC; 5, non-SOC) were given a diagnosis of a disease other than psoriasis when evaluated in the dermatology department.

Distributions between racial groups differed for insurance status, sex, psoriasis classification, biopsy status, and days between first dermatology visit and diagnosis. Skin of color patients had significantly longer days between initial presentation to dermatology and final diagnosis vs non-SOC patients (180.11 and 60.27 days, respectively; P=.001). Skin of color patients had a higher rate of palmoplantar psoriasis and severe plaque psoriasis (ie, >10% body surface area involvement) at presentation.

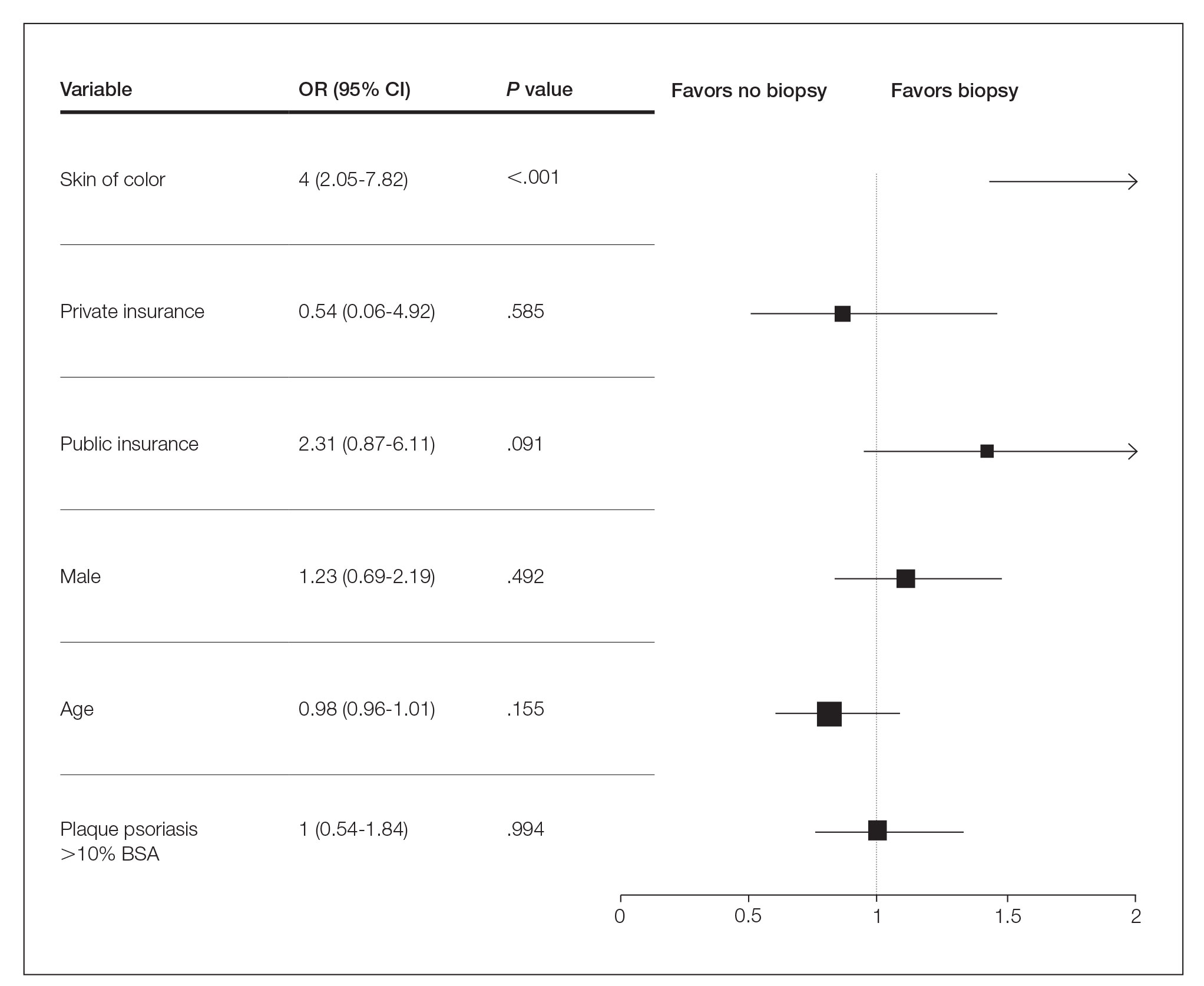

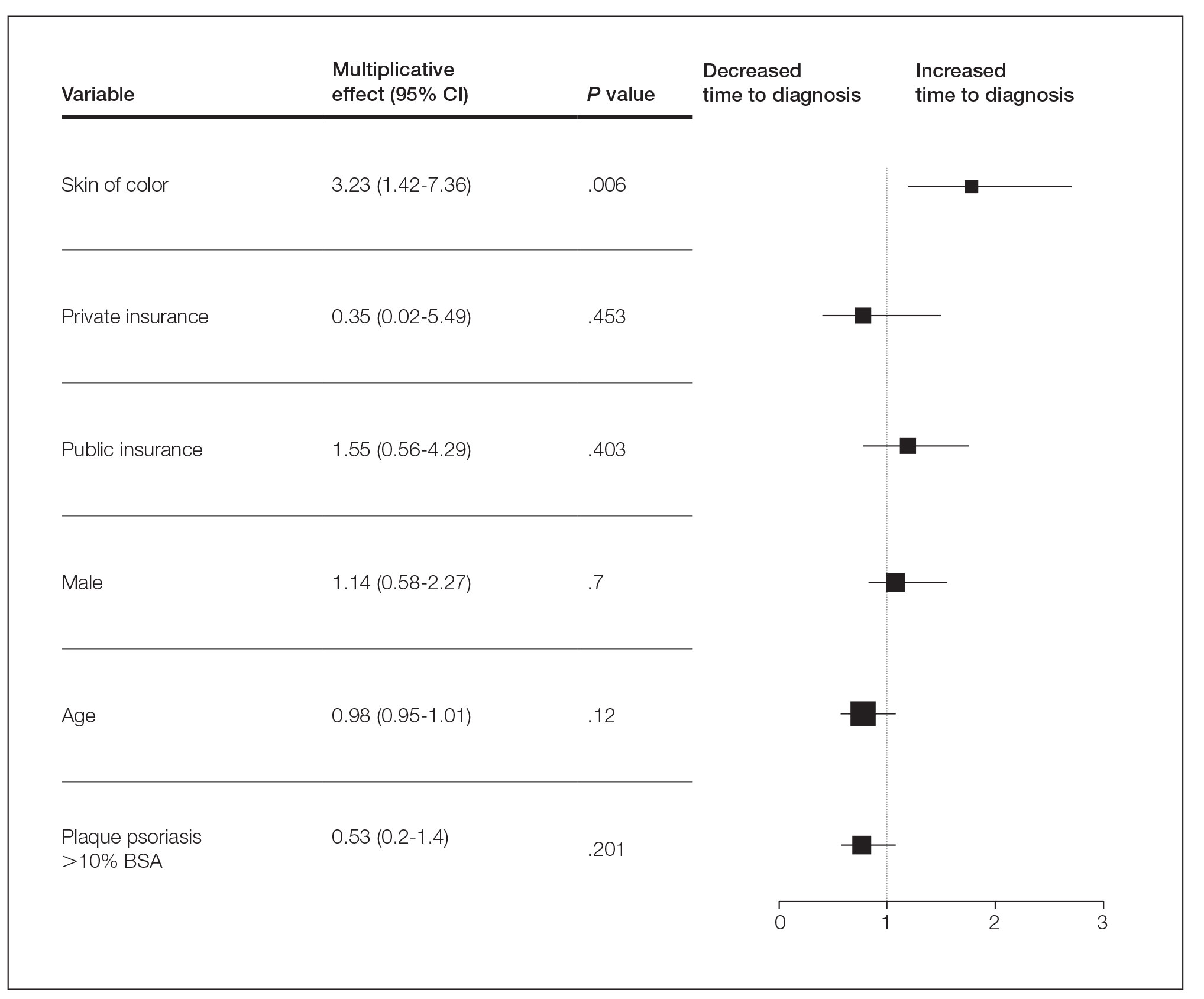

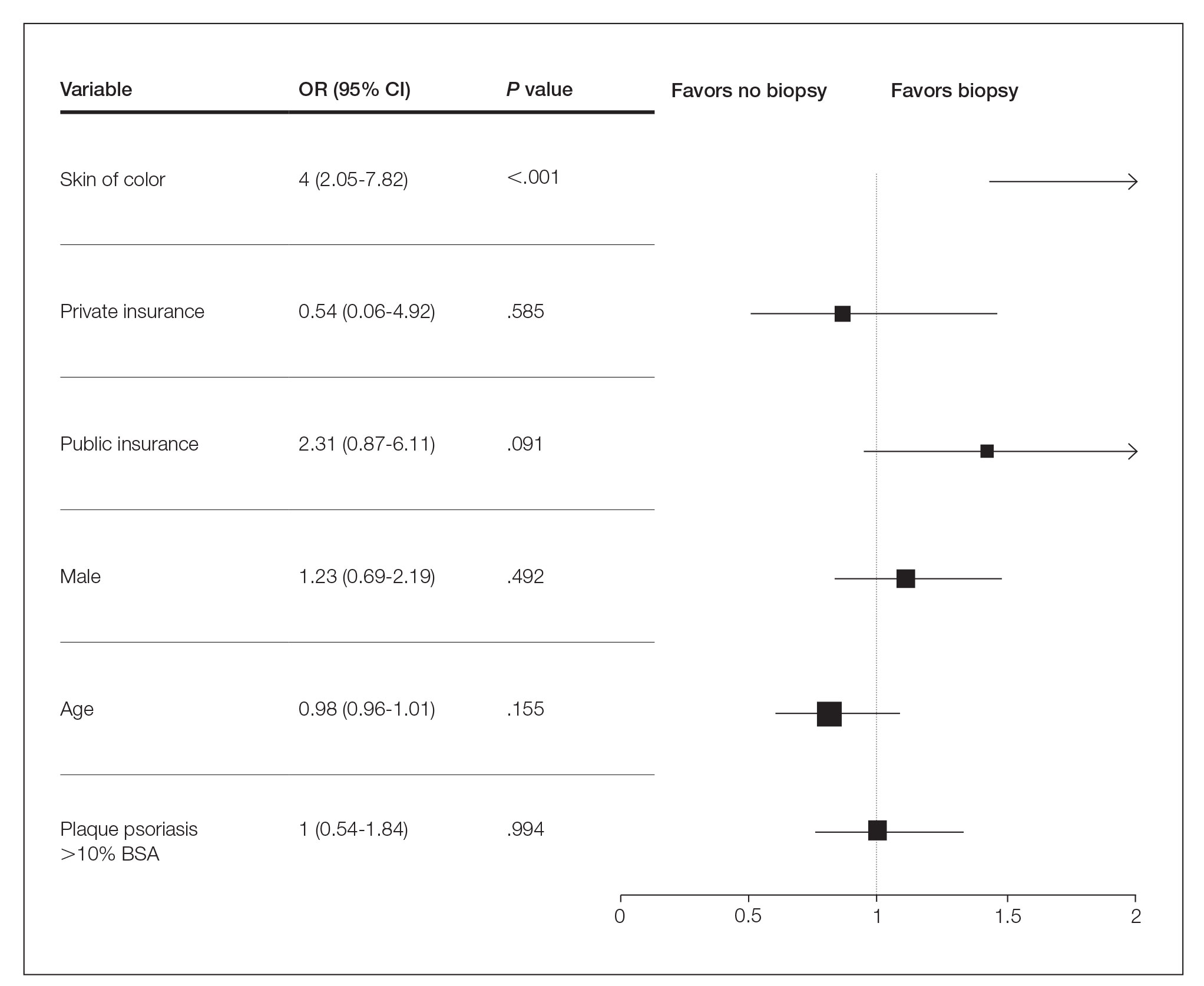

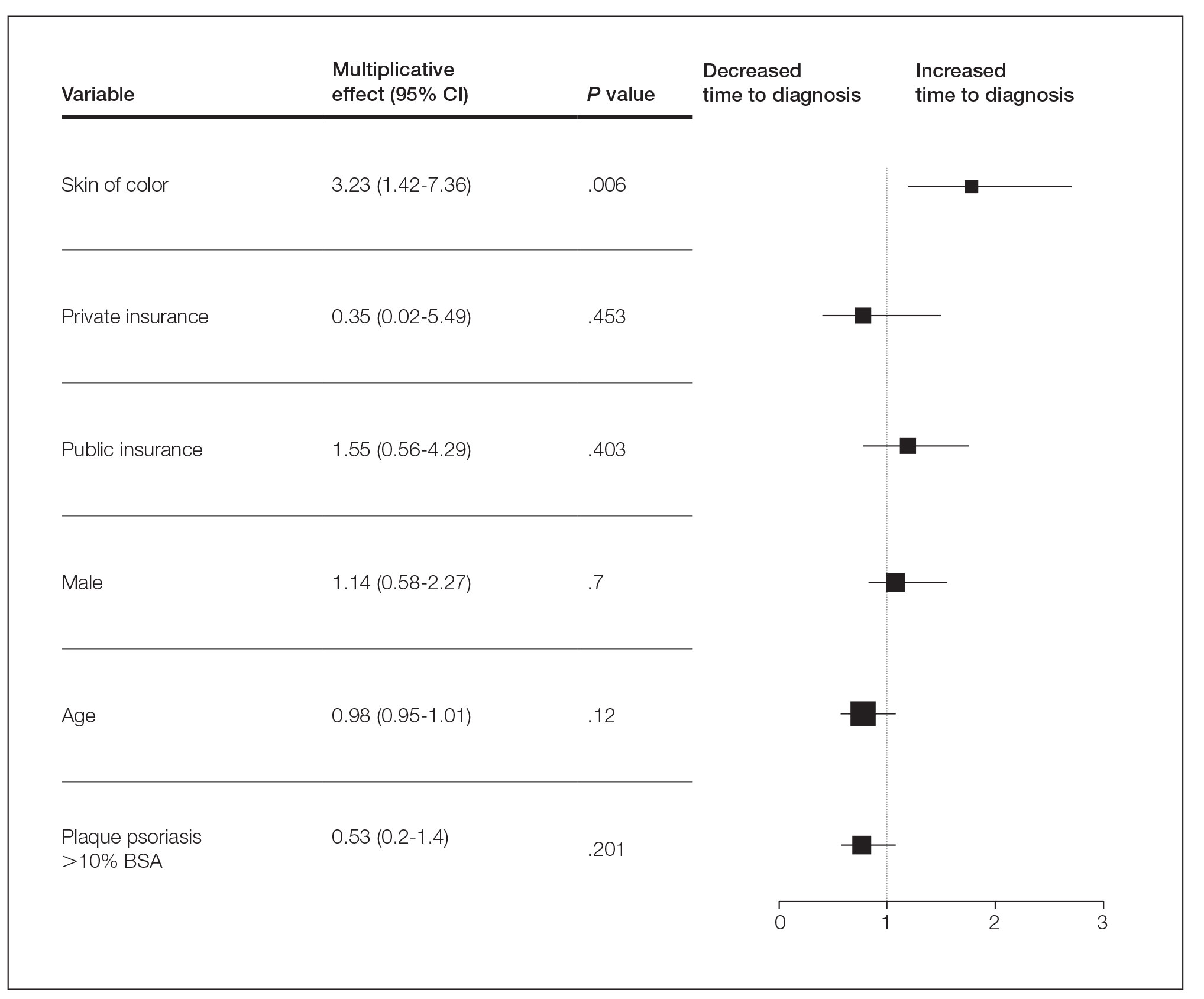

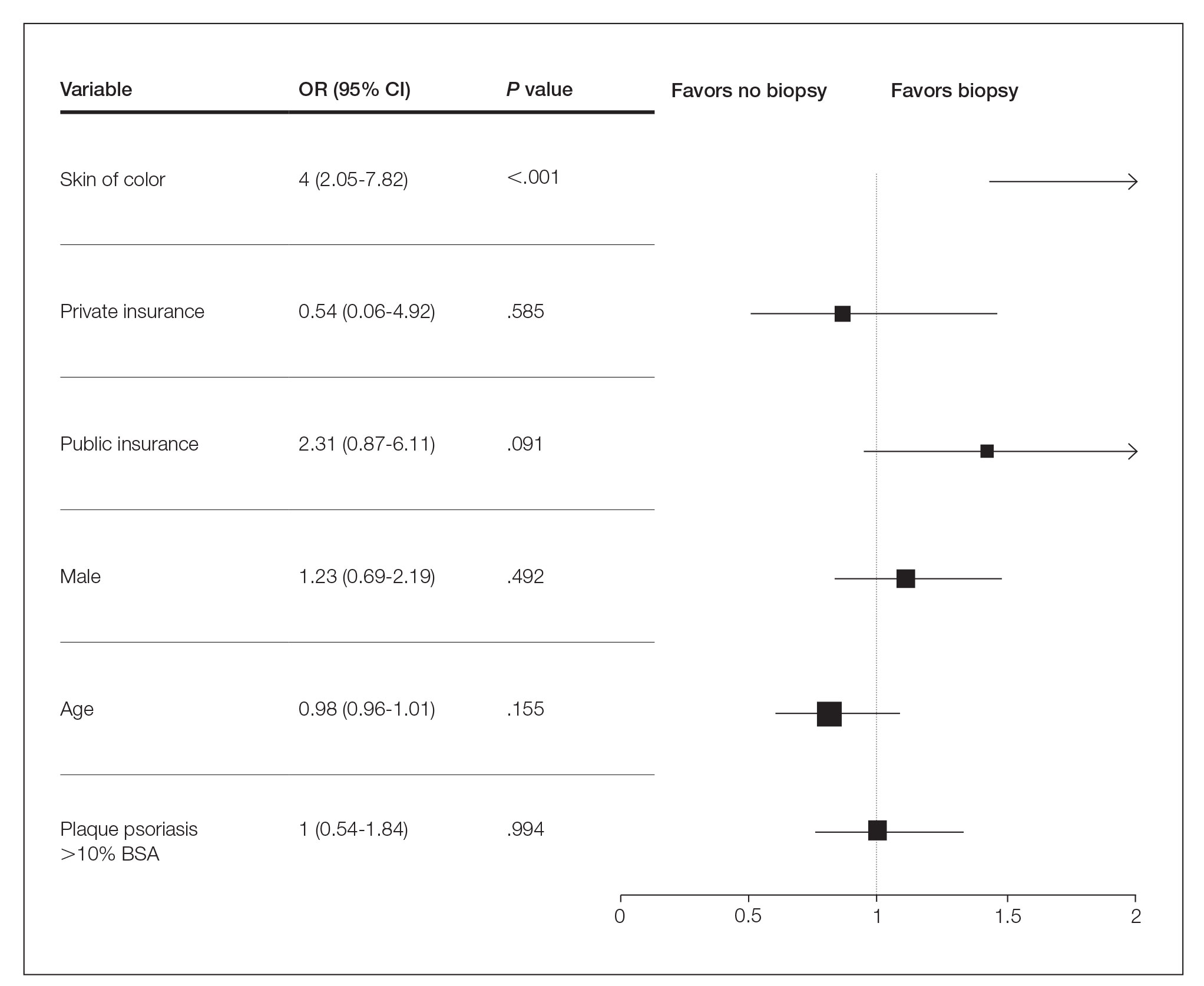

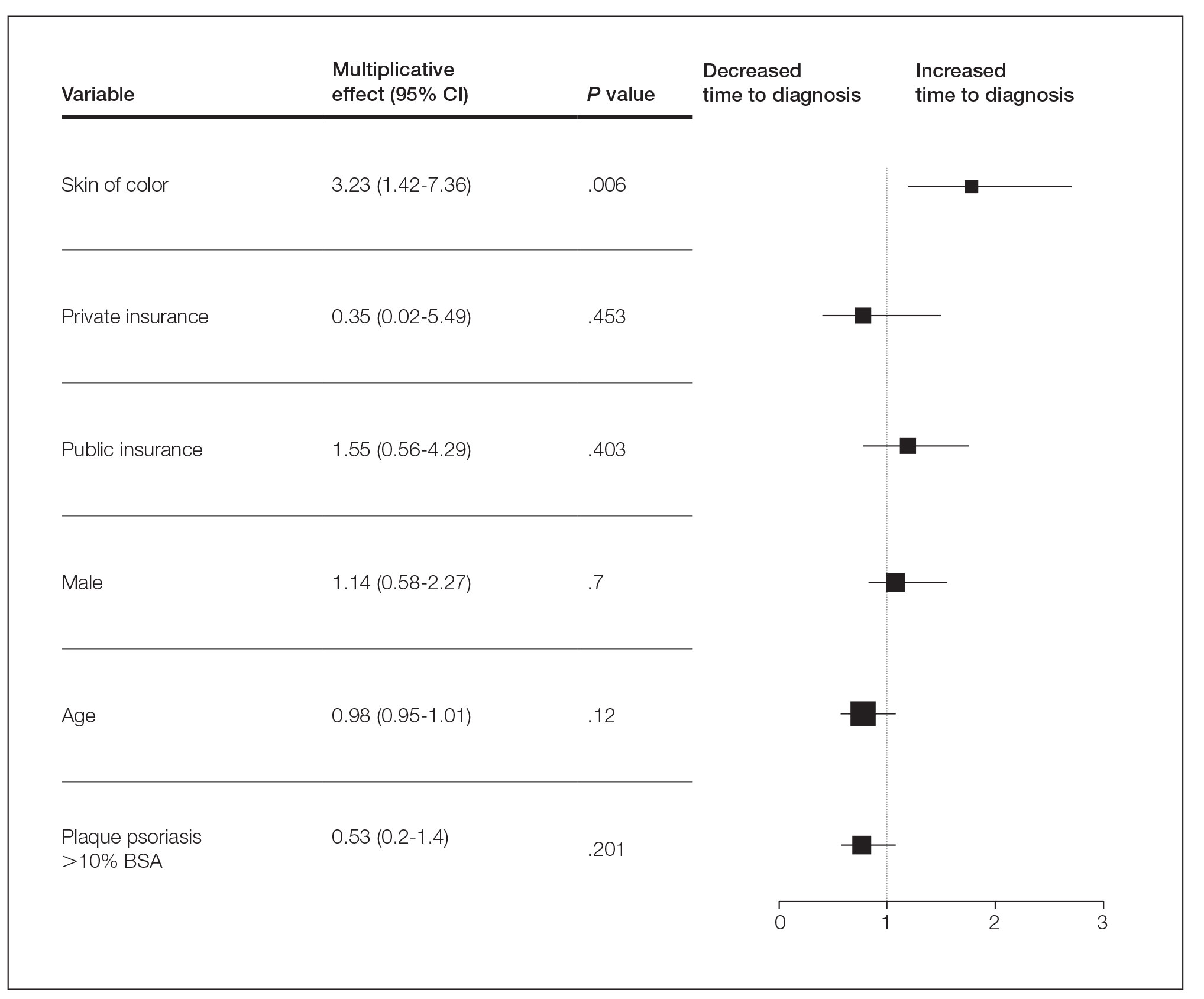

Several multivariable regression analyses were performed. Skin of color patients had significantly higher odds of biopsy compared to non-SOC patients (adjusted odds ratio [95% CI]=4 [2.05-7.82]; P<.001)(Figure 1). There were no significant predictors for severe plaque psoriasis involving more than 10% body surface area. Skin of color patients had a significantly longer time to diagnosis than non-SOC patients (P=.006)(Figure 2). On average, patients with SOC waited 3.23 times longer for a diagnosis than their non-SOC counterparts (95% CI, 1.42-7.36).

Our data reveal striking racial disparities in psoriasis care. Worse outcomes for patients with SOC compared to non-SOC patients may result from physicians’ inadequate familiarity with diverse presentations of psoriasis, including more frequent involvement of special body sites in SOC. Other likely contributing factors that we did not evaluate include socioeconomic barriers to health care, lack of physician diversity, missed appointments, and a paucity of literature on the topic of differentiating morphologies of psoriasis in SOC and non-SOC patients. Our study did not examine the effects of sex, tobacco use, or prior or current therapy, and it excluded pediatric patients.

To improve dermatologic outcomes for our increasingly diverse patient population, more studies must be undertaken to elucidate and document disparities in care for SOC populations.

- Gelfand JM, Stern RS, Nijsten T, et al. The prevalence of psoriasis in African Americans: results from a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:23-26. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.045

- Stern RS, Nijsten T, Feldman SR, et al. Psoriasis is common, carries a substantial burden even when not extensive, and is associated with widespread treatment dissatisfaction. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:136-139. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09102.x

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in skin of color: insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in non-white racial/ethnic groups. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:405-423. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0332-7

To the Editor:

Psoriasis affects 2% to 3% of the US population and is one of the more commonly diagnosed dermatologic conditions.1-3 Experts agree that common cutaneous diseases such as psoriasis present differently in patients with skin of color (SOC) compared to non-SOC patients.3,4 Despite the prevalence of psoriasis, data on these morphologic differences are limited.3-5 We performed a retrospective chart review comparing characteristics of psoriasis in SOC and non-SOC patients.

Through a search of electronic health records, we identified patients with an International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, diagnosis of psoriasis who were 18 years or older and were evaluated in the dermatology department between August 2015 and June 2020 at University Medical Center, an academic institution in New Orleans, Louisiana. Photographs and descriptions of lesions from these patients were reviewed. Patient data collected included age, sex, psoriasis classification, insurance status, self-identified race and ethnicity, location of lesion(s), biopsy, final diagnosis, and average number of visits or days required for accurate diagnosis. Self-identified SOC race and ethnicity categories included Black or African American, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian and Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, and “other.”

All analyses were conducted using R-4.0.1 statistics software. Categorical variables were compared in SOC and non-SOC groups using Fisher exact tests. Continuous covariates were conducted using a Wilcoxon rank sum test.

In total, we reviewed 557 charts. Four patients who declined to identify their race or ethnicity were excluded, yielding 286 SOC and 267 non-SOC patients (N=553). A total of 276 patients (131 SOC; 145 non-SOC) with a prior diagnosis of psoriasis were excluded in the days to diagnosis analysis. Twenty patients (15, SOC; 5, non-SOC) were given a diagnosis of a disease other than psoriasis when evaluated in the dermatology department.

Distributions between racial groups differed for insurance status, sex, psoriasis classification, biopsy status, and days between first dermatology visit and diagnosis. Skin of color patients had significantly longer days between initial presentation to dermatology and final diagnosis vs non-SOC patients (180.11 and 60.27 days, respectively; P=.001). Skin of color patients had a higher rate of palmoplantar psoriasis and severe plaque psoriasis (ie, >10% body surface area involvement) at presentation.

Several multivariable regression analyses were performed. Skin of color patients had significantly higher odds of biopsy compared to non-SOC patients (adjusted odds ratio [95% CI]=4 [2.05-7.82]; P<.001)(Figure 1). There were no significant predictors for severe plaque psoriasis involving more than 10% body surface area. Skin of color patients had a significantly longer time to diagnosis than non-SOC patients (P=.006)(Figure 2). On average, patients with SOC waited 3.23 times longer for a diagnosis than their non-SOC counterparts (95% CI, 1.42-7.36).

Our data reveal striking racial disparities in psoriasis care. Worse outcomes for patients with SOC compared to non-SOC patients may result from physicians’ inadequate familiarity with diverse presentations of psoriasis, including more frequent involvement of special body sites in SOC. Other likely contributing factors that we did not evaluate include socioeconomic barriers to health care, lack of physician diversity, missed appointments, and a paucity of literature on the topic of differentiating morphologies of psoriasis in SOC and non-SOC patients. Our study did not examine the effects of sex, tobacco use, or prior or current therapy, and it excluded pediatric patients.

To improve dermatologic outcomes for our increasingly diverse patient population, more studies must be undertaken to elucidate and document disparities in care for SOC populations.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis affects 2% to 3% of the US population and is one of the more commonly diagnosed dermatologic conditions.1-3 Experts agree that common cutaneous diseases such as psoriasis present differently in patients with skin of color (SOC) compared to non-SOC patients.3,4 Despite the prevalence of psoriasis, data on these morphologic differences are limited.3-5 We performed a retrospective chart review comparing characteristics of psoriasis in SOC and non-SOC patients.

Through a search of electronic health records, we identified patients with an International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, diagnosis of psoriasis who were 18 years or older and were evaluated in the dermatology department between August 2015 and June 2020 at University Medical Center, an academic institution in New Orleans, Louisiana. Photographs and descriptions of lesions from these patients were reviewed. Patient data collected included age, sex, psoriasis classification, insurance status, self-identified race and ethnicity, location of lesion(s), biopsy, final diagnosis, and average number of visits or days required for accurate diagnosis. Self-identified SOC race and ethnicity categories included Black or African American, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian and Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, and “other.”

All analyses were conducted using R-4.0.1 statistics software. Categorical variables were compared in SOC and non-SOC groups using Fisher exact tests. Continuous covariates were conducted using a Wilcoxon rank sum test.

In total, we reviewed 557 charts. Four patients who declined to identify their race or ethnicity were excluded, yielding 286 SOC and 267 non-SOC patients (N=553). A total of 276 patients (131 SOC; 145 non-SOC) with a prior diagnosis of psoriasis were excluded in the days to diagnosis analysis. Twenty patients (15, SOC; 5, non-SOC) were given a diagnosis of a disease other than psoriasis when evaluated in the dermatology department.

Distributions between racial groups differed for insurance status, sex, psoriasis classification, biopsy status, and days between first dermatology visit and diagnosis. Skin of color patients had significantly longer days between initial presentation to dermatology and final diagnosis vs non-SOC patients (180.11 and 60.27 days, respectively; P=.001). Skin of color patients had a higher rate of palmoplantar psoriasis and severe plaque psoriasis (ie, >10% body surface area involvement) at presentation.

Several multivariable regression analyses were performed. Skin of color patients had significantly higher odds of biopsy compared to non-SOC patients (adjusted odds ratio [95% CI]=4 [2.05-7.82]; P<.001)(Figure 1). There were no significant predictors for severe plaque psoriasis involving more than 10% body surface area. Skin of color patients had a significantly longer time to diagnosis than non-SOC patients (P=.006)(Figure 2). On average, patients with SOC waited 3.23 times longer for a diagnosis than their non-SOC counterparts (95% CI, 1.42-7.36).

Our data reveal striking racial disparities in psoriasis care. Worse outcomes for patients with SOC compared to non-SOC patients may result from physicians’ inadequate familiarity with diverse presentations of psoriasis, including more frequent involvement of special body sites in SOC. Other likely contributing factors that we did not evaluate include socioeconomic barriers to health care, lack of physician diversity, missed appointments, and a paucity of literature on the topic of differentiating morphologies of psoriasis in SOC and non-SOC patients. Our study did not examine the effects of sex, tobacco use, or prior or current therapy, and it excluded pediatric patients.

To improve dermatologic outcomes for our increasingly diverse patient population, more studies must be undertaken to elucidate and document disparities in care for SOC populations.

- Gelfand JM, Stern RS, Nijsten T, et al. The prevalence of psoriasis in African Americans: results from a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:23-26. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.045

- Stern RS, Nijsten T, Feldman SR, et al. Psoriasis is common, carries a substantial burden even when not extensive, and is associated with widespread treatment dissatisfaction. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:136-139. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09102.x

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in skin of color: insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in non-white racial/ethnic groups. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:405-423. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0332-7

- Gelfand JM, Stern RS, Nijsten T, et al. The prevalence of psoriasis in African Americans: results from a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:23-26. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.045

- Stern RS, Nijsten T, Feldman SR, et al. Psoriasis is common, carries a substantial burden even when not extensive, and is associated with widespread treatment dissatisfaction. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:136-139. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09102.x

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in skin of color: insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in non-white racial/ethnic groups. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:405-423. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0332-7

Practice Points

- Skin of color (SOC) patients can wait 3 times longer to receive a diagnosis of psoriasis than non-SOC patients.

- Patients with SOC more often present with severe forms of psoriasis and are more likely to have palmoplantar psoriasis.

- Skin of color patients can be 4 times as likely to require a biopsy to confirm psoriasis diagnosis compared to non-SOC patients.

Funding of cosmetic clinical trials linked to racial/ethnic disparity

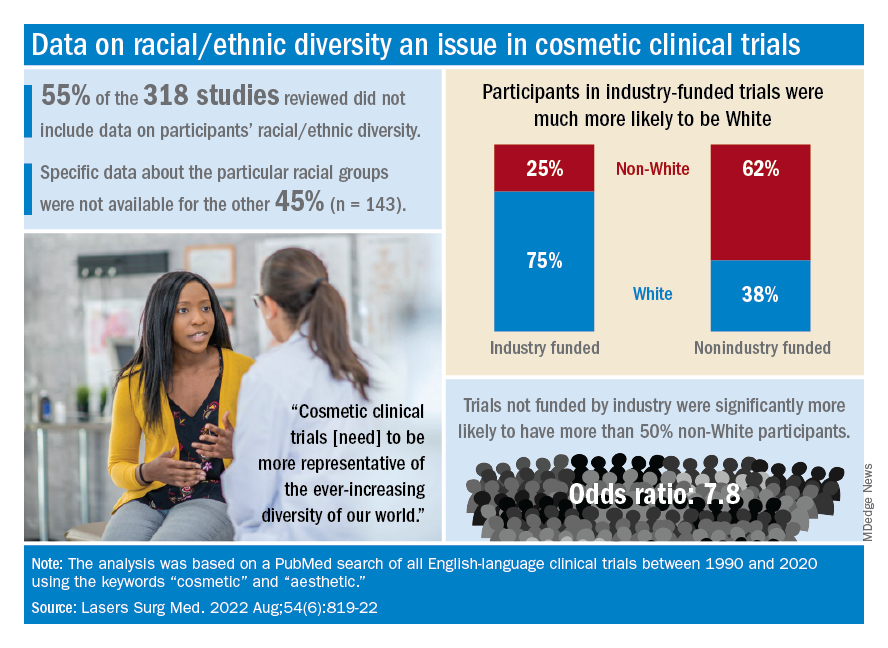

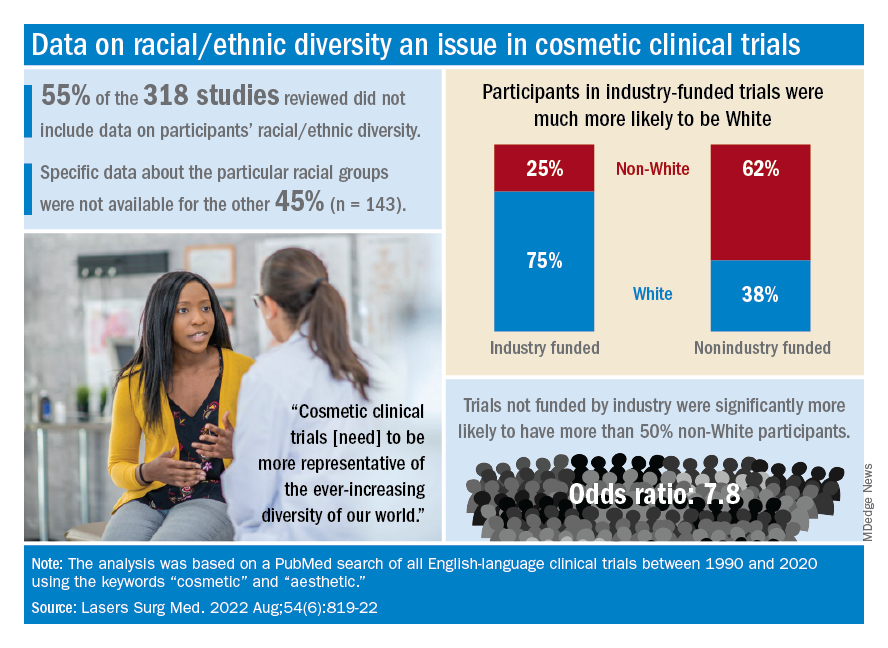

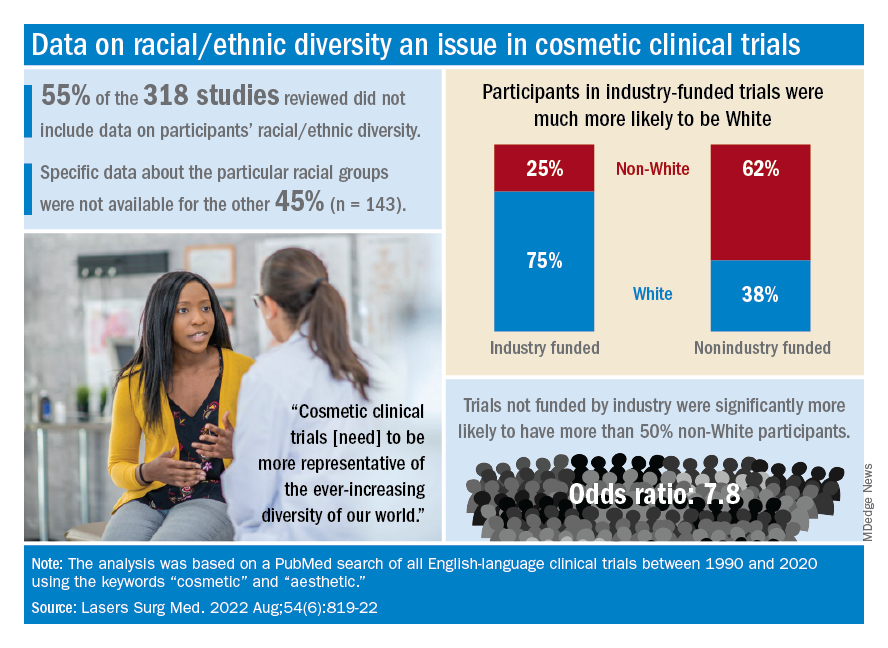

Individuals of nonwhite race/ethnicity are not underrepresented in cosmetic clinical trials, according to a recent literature review. The explanation for those contradictory conclusions comes down to money, or, more specifically, the source of the money.

Among the cosmetic studies funded by industry, non-Whites represented about 25% of the patient populations. That proportion, however, rose to 62% for studies that were funded by universities/governments or had no funding source reported, Lisa Akintilo, MD, and associates said in their review.

“Lack of inclusion of diverse patient populations is both a medical and moral issue as conclusions of such homogeneous studies may not be generalizable. In the realm of cosmetic dermatology, diverse research cohorts are needed to identify potential disparities in therapies for cosmetic concerns and fully investigate effective treatments for all,” wrote Dr. Akintilo of New York University and coauthors.

Data from the U.S. Census show that non-Hispanic Whites made up 60% of the population in 2019, with that proportion falling to about 50% by 2045, the investigators noted. A report from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that about 34% of cosmetic patients identified as skin of color in 2020.

The availability of data was an issue in the review of the literature from 1990 to 2020, as 55% of the 318 randomized controlled trials that were reviewed did not include any information on racial/ethnic diversity and the other 143 studies offered only enough to determine White/non-White status, they explained.

That limitation meant that those 143 studies had to form the basis of the funding analysis, which also indicated that the studies with funding outside of industry were significantly more likely (odds ratio, 7.8) to have more than 50% non-White participants, compared with the industry-funded trials. The projects with industry backing, however, had a larger mean sample size than did those without: 139 vs. 81, Dr. Akintilo and associates said.

“The protocols of cosmetic trials should be questioned, as many target Caucasian‐centric treatment goals that may not be in alignment with the goals of skin of color patients,” they wrote. “It is important for cosmetic providers to recognize the well-established anatomical variations between different races and ethnicities and how they can inform desired cosmetic procedures.”

The investigators said that they had no conflicts of interest.

Individuals of nonwhite race/ethnicity are not underrepresented in cosmetic clinical trials, according to a recent literature review. The explanation for those contradictory conclusions comes down to money, or, more specifically, the source of the money.

Among the cosmetic studies funded by industry, non-Whites represented about 25% of the patient populations. That proportion, however, rose to 62% for studies that were funded by universities/governments or had no funding source reported, Lisa Akintilo, MD, and associates said in their review.

“Lack of inclusion of diverse patient populations is both a medical and moral issue as conclusions of such homogeneous studies may not be generalizable. In the realm of cosmetic dermatology, diverse research cohorts are needed to identify potential disparities in therapies for cosmetic concerns and fully investigate effective treatments for all,” wrote Dr. Akintilo of New York University and coauthors.

Data from the U.S. Census show that non-Hispanic Whites made up 60% of the population in 2019, with that proportion falling to about 50% by 2045, the investigators noted. A report from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that about 34% of cosmetic patients identified as skin of color in 2020.

The availability of data was an issue in the review of the literature from 1990 to 2020, as 55% of the 318 randomized controlled trials that were reviewed did not include any information on racial/ethnic diversity and the other 143 studies offered only enough to determine White/non-White status, they explained.

That limitation meant that those 143 studies had to form the basis of the funding analysis, which also indicated that the studies with funding outside of industry were significantly more likely (odds ratio, 7.8) to have more than 50% non-White participants, compared with the industry-funded trials. The projects with industry backing, however, had a larger mean sample size than did those without: 139 vs. 81, Dr. Akintilo and associates said.

“The protocols of cosmetic trials should be questioned, as many target Caucasian‐centric treatment goals that may not be in alignment with the goals of skin of color patients,” they wrote. “It is important for cosmetic providers to recognize the well-established anatomical variations between different races and ethnicities and how they can inform desired cosmetic procedures.”

The investigators said that they had no conflicts of interest.

Individuals of nonwhite race/ethnicity are not underrepresented in cosmetic clinical trials, according to a recent literature review. The explanation for those contradictory conclusions comes down to money, or, more specifically, the source of the money.

Among the cosmetic studies funded by industry, non-Whites represented about 25% of the patient populations. That proportion, however, rose to 62% for studies that were funded by universities/governments or had no funding source reported, Lisa Akintilo, MD, and associates said in their review.

“Lack of inclusion of diverse patient populations is both a medical and moral issue as conclusions of such homogeneous studies may not be generalizable. In the realm of cosmetic dermatology, diverse research cohorts are needed to identify potential disparities in therapies for cosmetic concerns and fully investigate effective treatments for all,” wrote Dr. Akintilo of New York University and coauthors.

Data from the U.S. Census show that non-Hispanic Whites made up 60% of the population in 2019, with that proportion falling to about 50% by 2045, the investigators noted. A report from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that about 34% of cosmetic patients identified as skin of color in 2020.

The availability of data was an issue in the review of the literature from 1990 to 2020, as 55% of the 318 randomized controlled trials that were reviewed did not include any information on racial/ethnic diversity and the other 143 studies offered only enough to determine White/non-White status, they explained.

That limitation meant that those 143 studies had to form the basis of the funding analysis, which also indicated that the studies with funding outside of industry were significantly more likely (odds ratio, 7.8) to have more than 50% non-White participants, compared with the industry-funded trials. The projects with industry backing, however, had a larger mean sample size than did those without: 139 vs. 81, Dr. Akintilo and associates said.

“The protocols of cosmetic trials should be questioned, as many target Caucasian‐centric treatment goals that may not be in alignment with the goals of skin of color patients,” they wrote. “It is important for cosmetic providers to recognize the well-established anatomical variations between different races and ethnicities and how they can inform desired cosmetic procedures.”

The investigators said that they had no conflicts of interest.

FROM LASERS IN SURGERY AND MEDICINE

Differences in Underrepresented in Medicine Applicant Backgrounds and Outcomes in the 2020-2021 Dermatology Residency Match

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

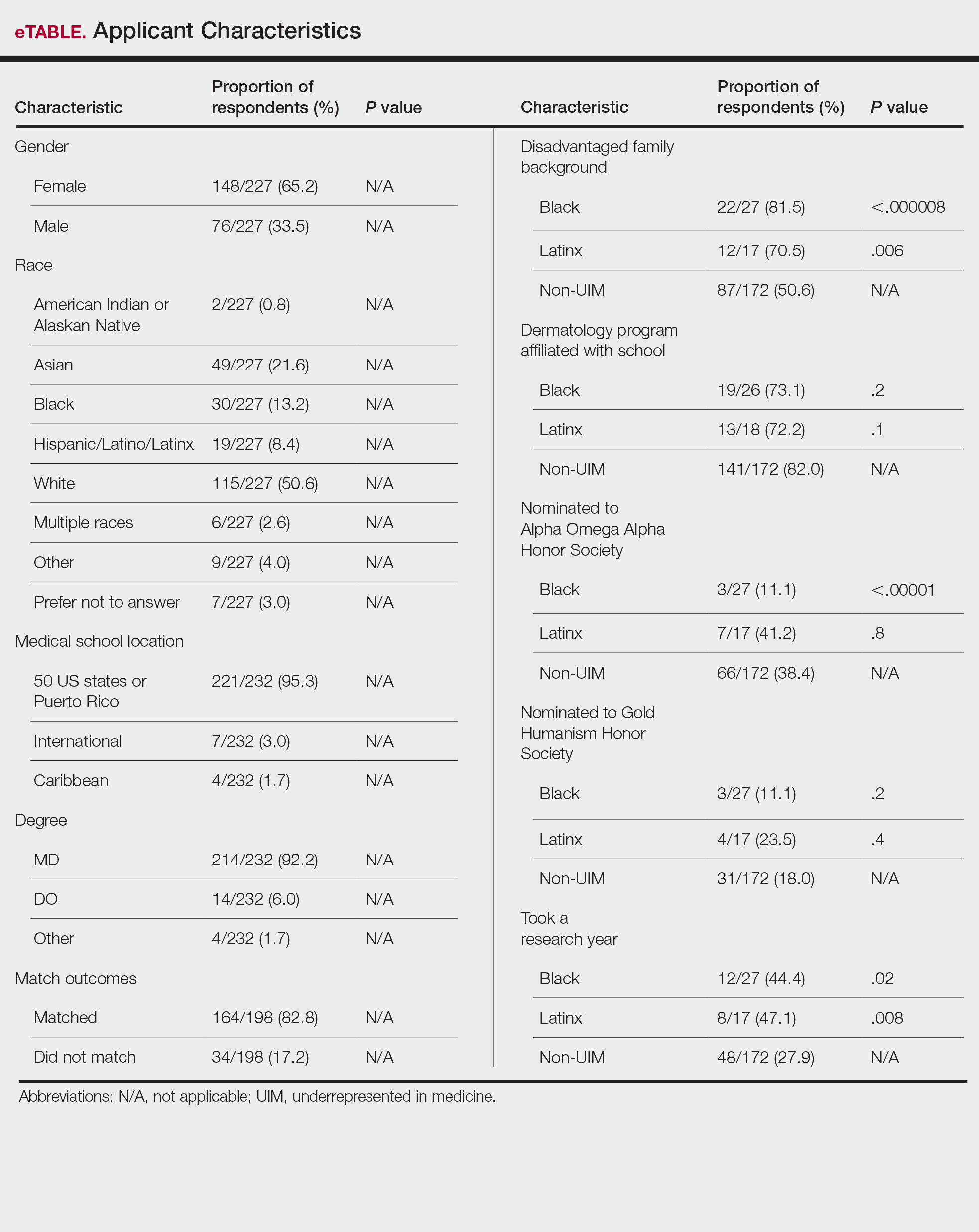

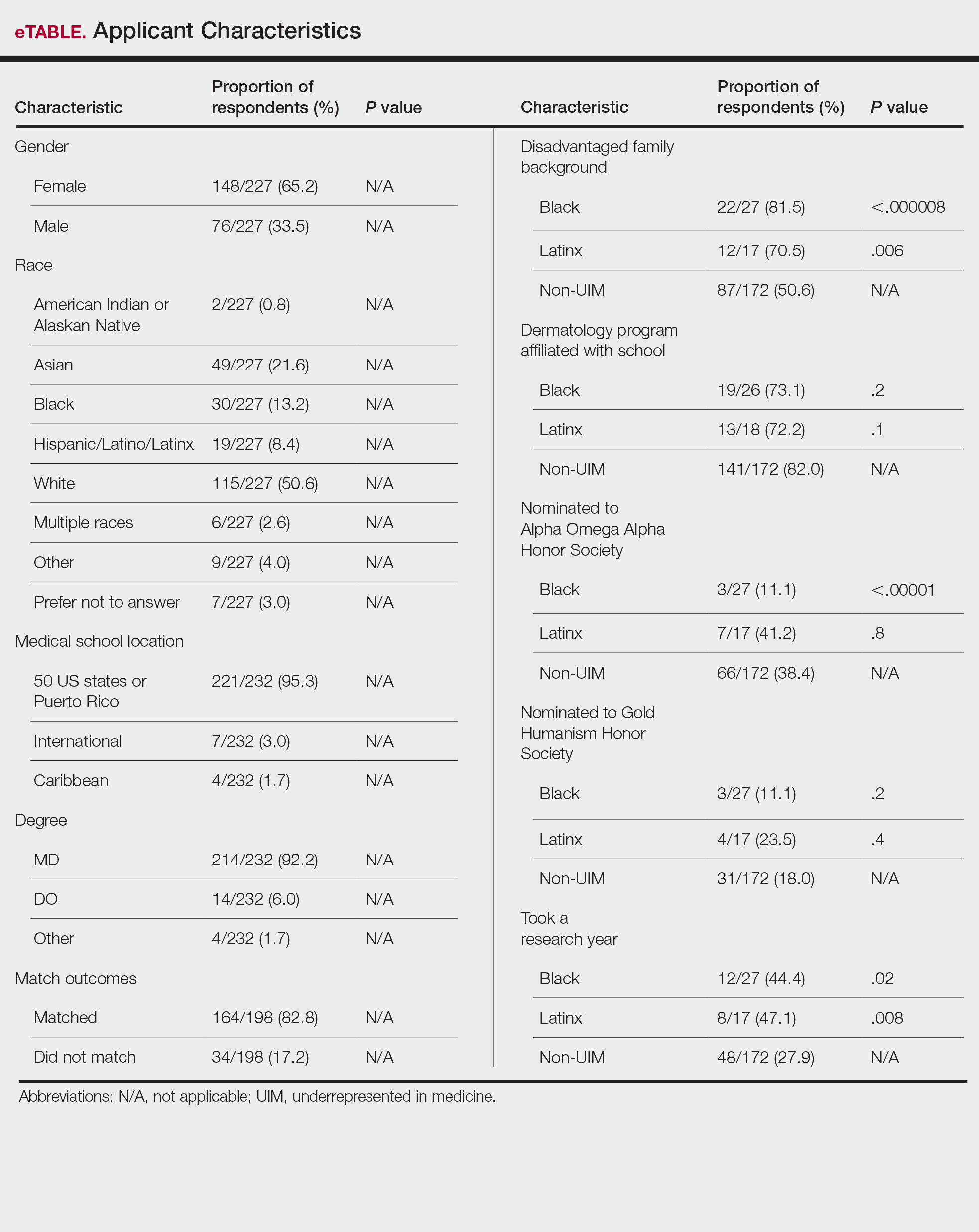

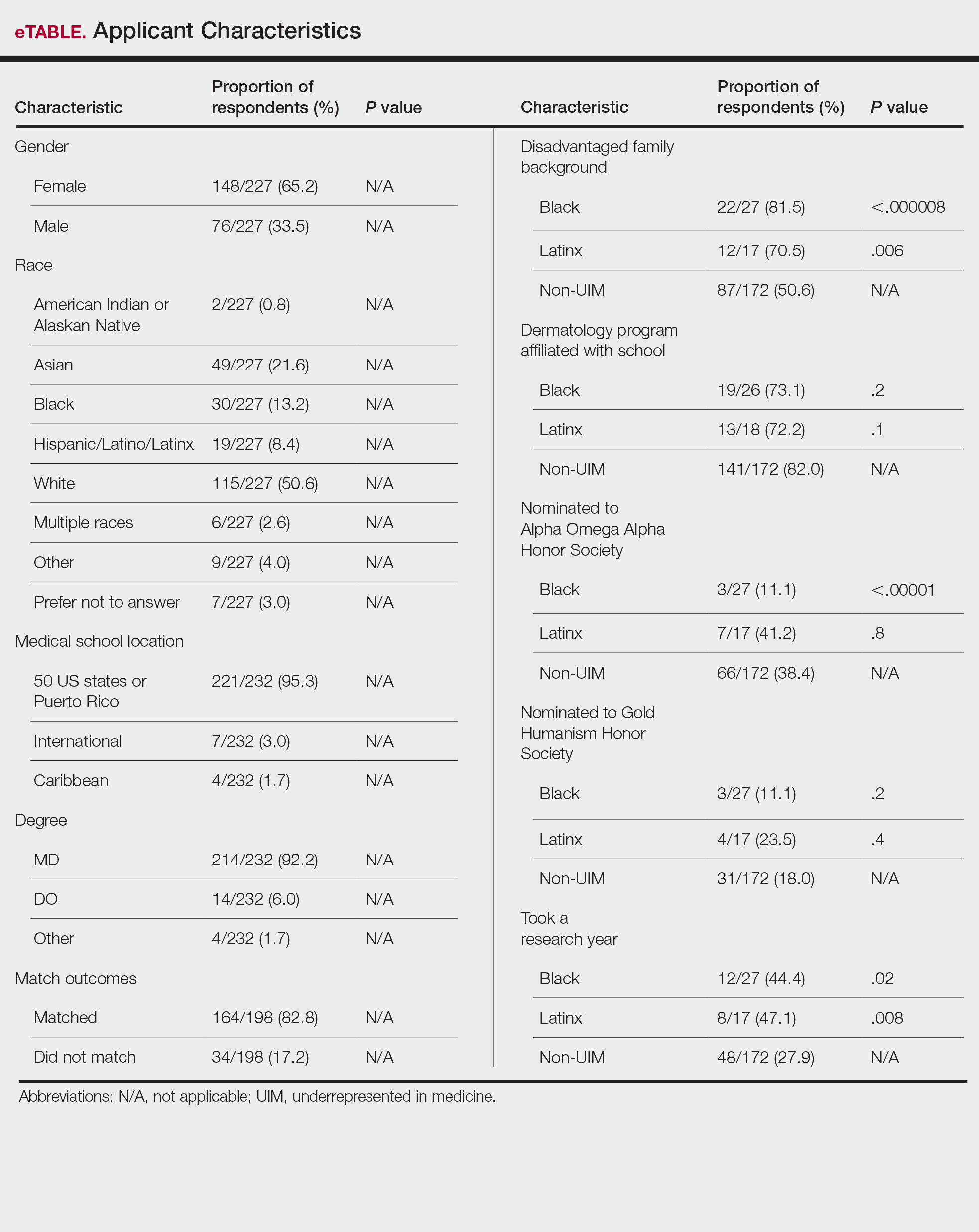

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

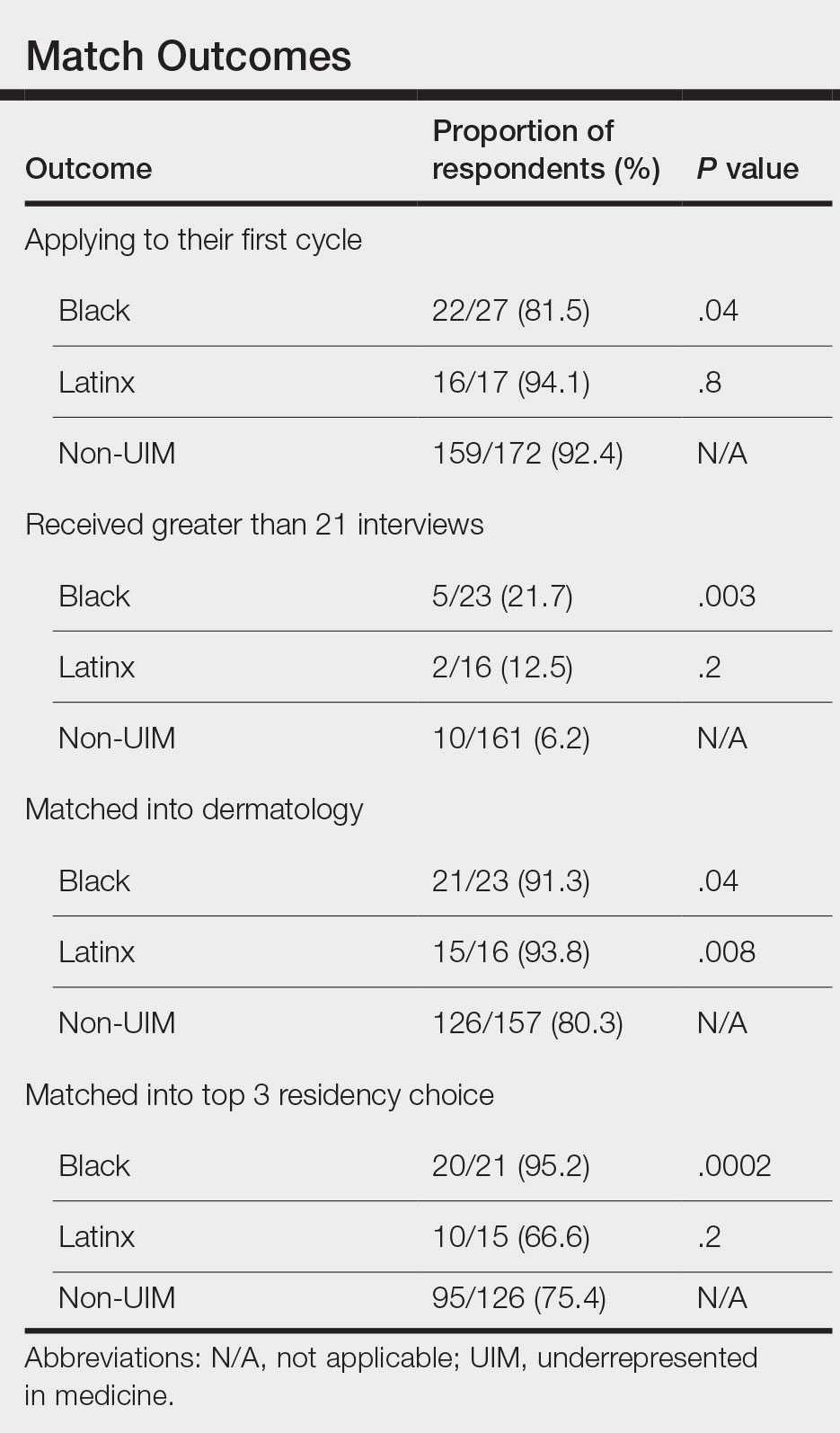

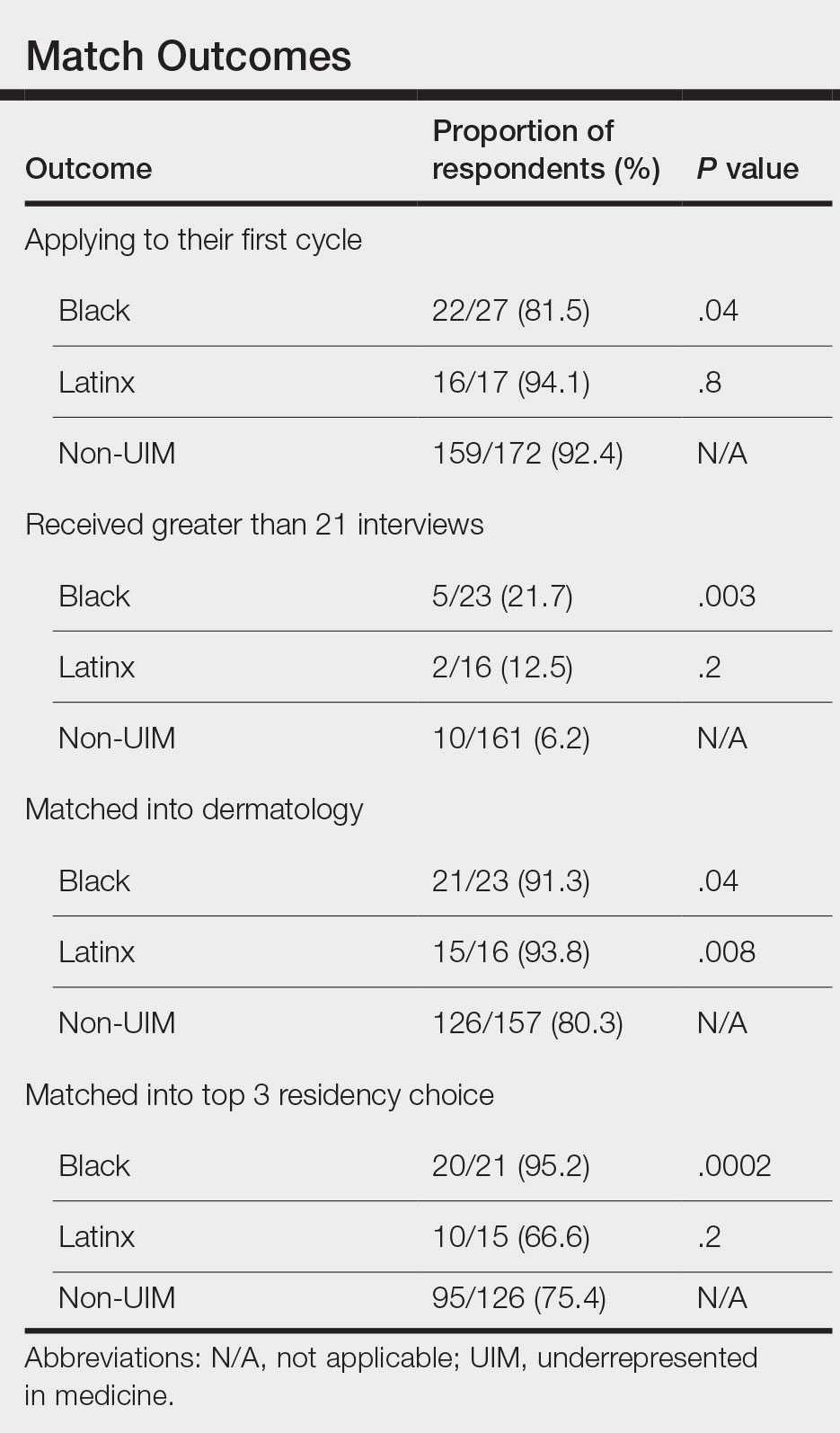

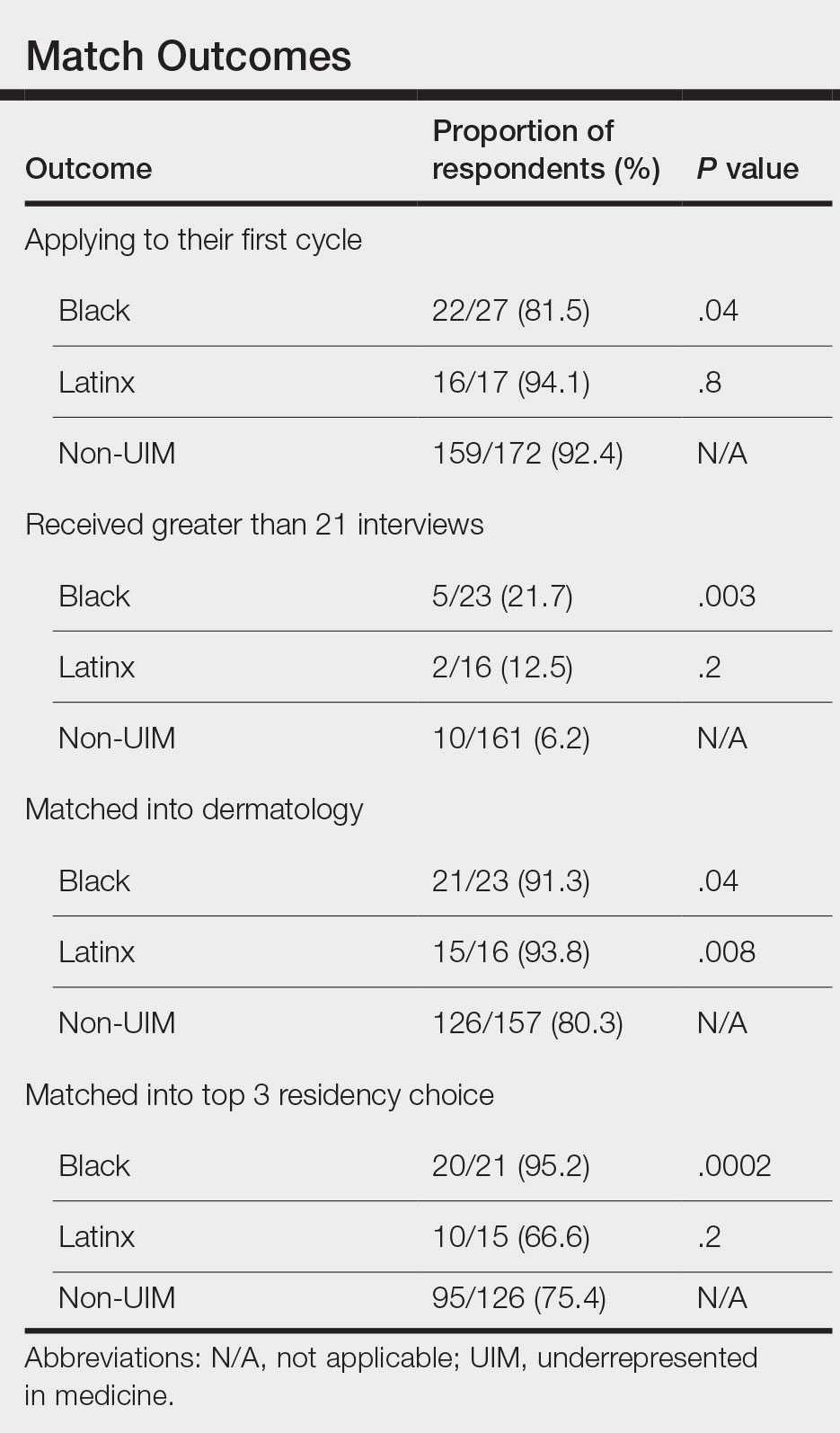

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

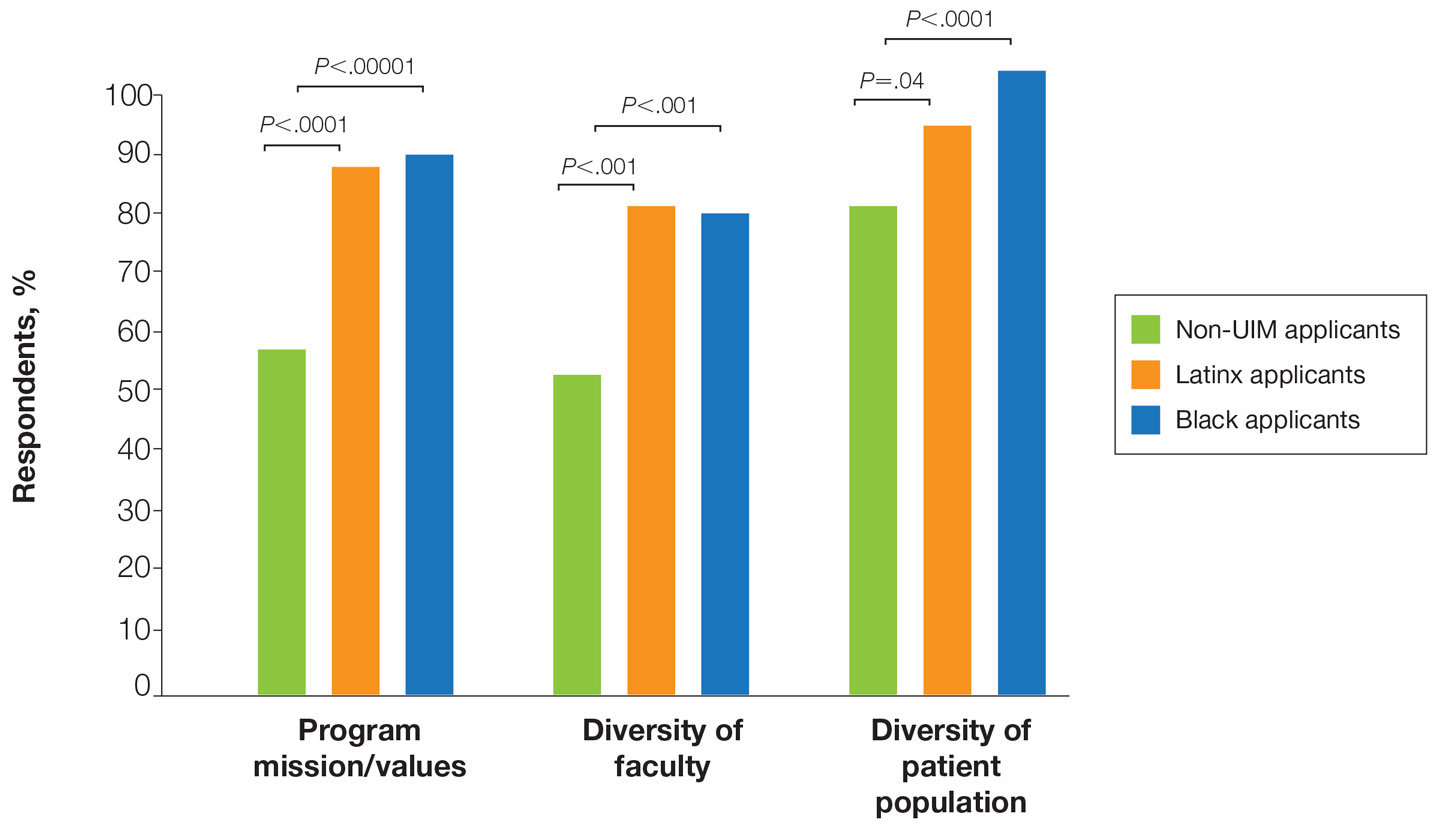

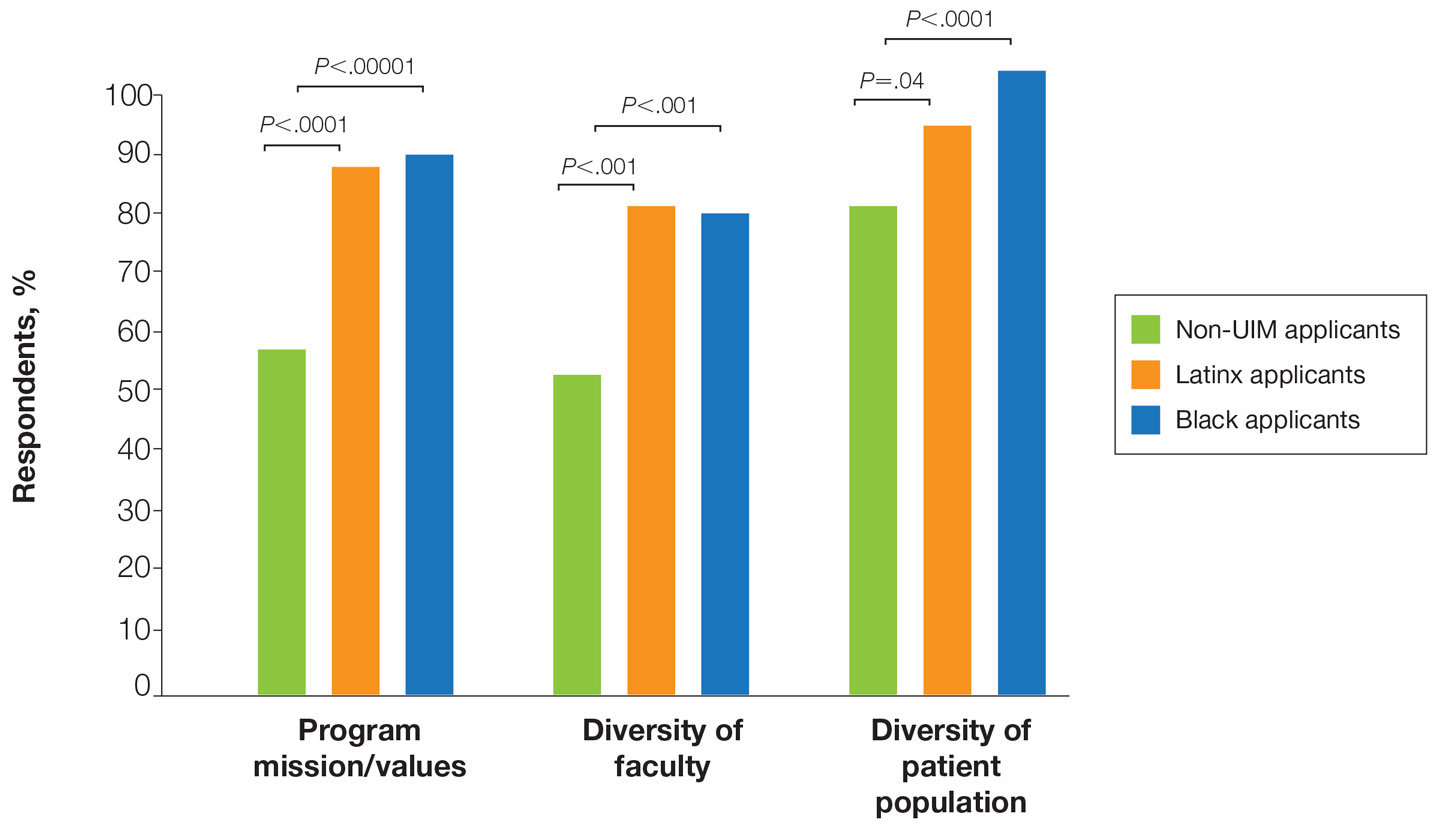

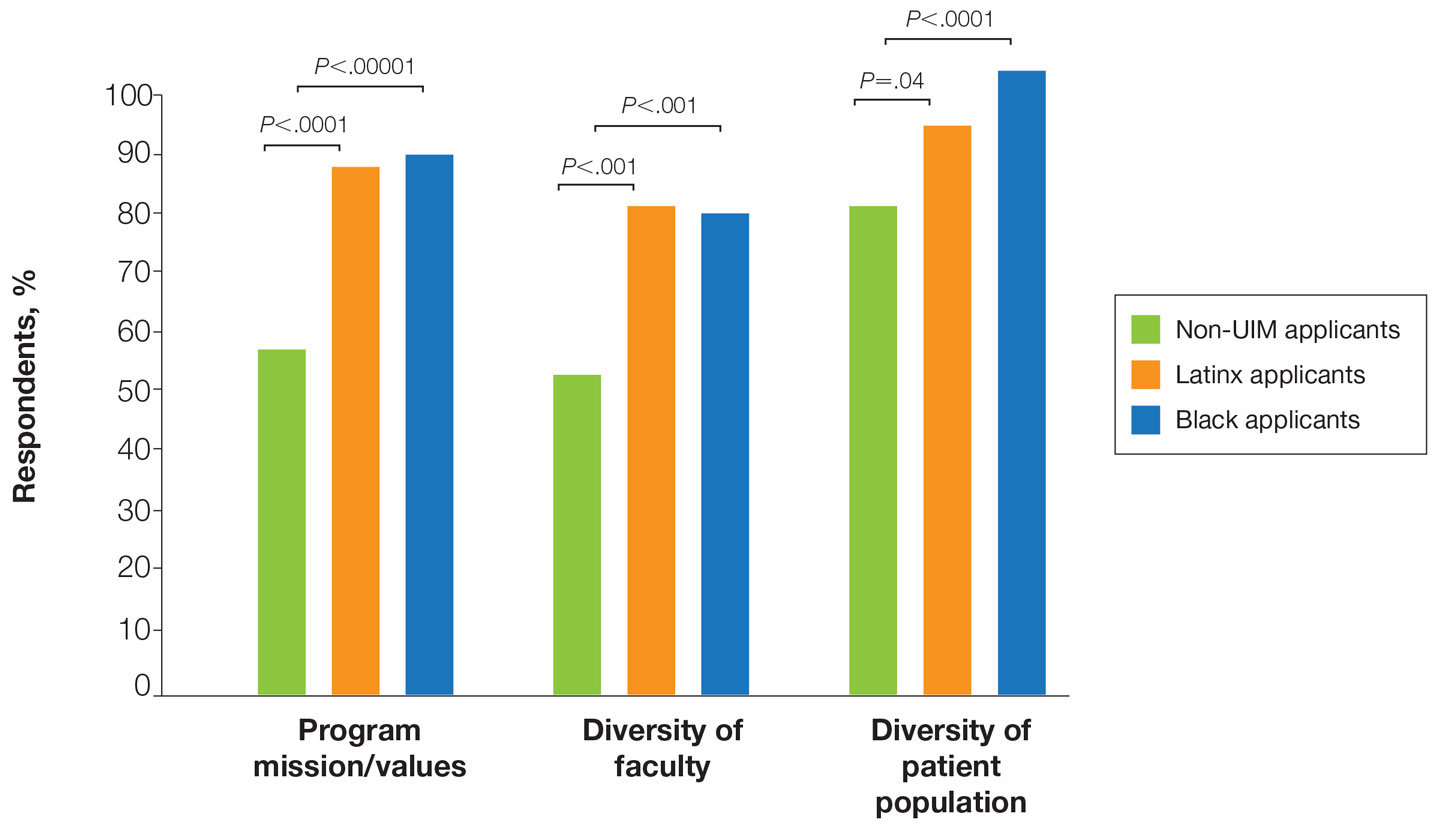

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.