User login

Black HFrEF patients get more empagliflozin benefit in EMPEROR analyses

CHICAGO – Black patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) may receive more benefit from treatment with a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor than do White patients, according to a new report.

A secondary analysis of data collected from the pivotal trials that assessed the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in patients with HFrEF, EMPEROR-Reduced, and in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), EMPEROR-Preserved, was presented by Subodh Verma, MD, PhD, at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The “hypothesis-generating” analysis of data from EMPEROR-Reduced showed “a suggestion of a greater benefit of empagliflozin” in Black, compared with White patients, for the study’s primary endpoint (cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure) as well as for first and total hospitalizations for heart failure, he reported.

However, a similar but separate analysis that compared Black and White patients with heart failure who received treatment with a second agent, dapagliflozin, from the same SGLT2-inhibitor class did not show any suggestion of heterogeneity in the drug’s effect based on race.

Race-linked heterogeneity in empagliflozin’s effect

In EMPEROR-Reduced, which randomized 3,730 patients with heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less, treatment of White patients with empagliflozin (Jardiance) produced a nonsignificant 16% relative reduction in the rate of the primary endpoint, compared with placebo, during a median 16-month follow-up.

By contrast, among Black patients, treatment with empagliflozin produced a significant 56% reduction in the primary endpoint, compared with placebo-treated patients, a significant heterogeneity (P = .02) in effect between the two race subgroups, said Dr. Verma, a cardiac surgeon and professor at the University of Toronto.

The analysis he reported used combined data from EMPEROR-Reduced and the companion trial EMPEROR-Preserved, which randomized 5,988 patients with heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction greater than 40% to treatment with either empagliflozin or placebo and followed them for a median of 26 months.

To assess the effects of the randomized treatments in the two racial subgroups, Dr. Verma and associates used pooled data from both trials, but only from the 3,502 patients enrolled in the Americas, which included 3,024 White patients and 478 Black patients. Analysis of the patients in this subgroup who were randomized to placebo showed a significantly excess rate of the primary outcome among Blacks, who tallied 49% more of the primary outcome events during follow-up than did White patients, Dr. Verma reported. The absolute rate of the primary outcome without empagliflozin treatment was 13.15 events/100 patient-years of follow-up in White patients and 20.83 events/100 patient-years in Black patients.

The impact of empagliflozin was not statistically heterogeneous in the total pool of patients that included both those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF. The drug reduced the primary outcome incidence by a significant 20% in White patients, and by a significant 44% among Black patients.

But this point-estimate difference in efficacy, when coupled with the underlying difference in risk for an event between the two racial groups, meant that the number-needed-to-treat to prevent one primary outcome event was 42 among White patients and 12 among Black patients.

Race-linked treatment responses only in HFrEF

This suggestion of an imbalance in treatment efficacy was especially apparent among patients with HFrEF. In addition to the heterogeneity for the primary outcome, the Black and White subgroups also showed significantly divergent results for the outcomes of first hospitalization for heart failure, with a nonsignificant 21% relative reduction with empagliflozin treatment in Whites but a significant 65% relative cut in this endpoint with empagliflozin in Blacks, and for total hospitalizations for heart failure, which showed a similar level of significant heterogeneity between the two race subgroups.

In contrast, the patients with HFpEF showed no signal at all for heterogeneous outcome rates between Black and White subgroups.

One other study outcome, change in symptom burden measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), also showed suggestion of a race-based imbalance. The adjusted mean difference from baseline in the KCCQ clinical summary score was 1.50 points higher with empagliflozin treatment, compared with placebo among all White patients (those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF), and compared with a 5.25-point increase with empagliflozin over placebo among all Black patients with heart failure in the pooled American EMPEROR dataset, a difference between White and Black patients that just missed significance (P = .06). Again, this difference was especially notable and significant among the patients with HFrEF, where the adjusted mean difference in KCCQ was a 0.77-point increase in White patients and a 6.71-point increase among Black patients (P = .043),

These results also appeared in a report published simultaneously with Dr. Verma’s talk.

But two other analyses that assessed a possible race-based difference in empagliflozin’s effect on renal protection and on functional status showed no suggestion of heterogeneity.

Dr. Verma stressed caution about the limitations of these analyses because they involved a relatively small number of Black patients, and were possibly subject to unadjusted confounding from differences in baseline characteristics between the Black and White patients.

Black patients also had a number-needed-to-treat advantage with dapagliflozin

The finding that Black patients with heart failure potentially get more bang for the buck from treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor by having a lower number needed to treat also showed up in a separate report at the meeting that assessed the treatment effect from dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in Black and White patients in a pooled analysis of the DAPA-HF pivotal trial of patients with HFrEF and the DELIVER pivotal trial of patients with HFpEF. The pooled cohort included a total of 11,007, but for the analysis by race the investigators also limited their focus to patients from the Americas with 2,626 White patients and 381 Black patients.

Assessment of the effect of dapagliflozin on the primary outcome of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure among all patients, both those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF, again showed that event rates among patients treated with placebo were significantly higher in Black, compared with White patients, and this led to a difference in the number needed to treat to prevent one primary outcome event of 12 in Blacks and 17 in Whites, Jawad H. Butt, MD said in a talk at the meeting.

Although treatment with dapagliflozin reduced the rate of the primary outcome in this subgroup of patients from the DAPA-HF trial and the DELIVER trial by similar rates in Black and White patients, event rates were higher in the Black patients resulting in “greater benefit in absolute terms” for Black patients, explained Dr. Butt, a cardiologist at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen.

But in contrast to the empagliflozin findings reported by Dr. Verma, the combined data from the dapagliflozin trials showed no suggestion of heterogeneity in the beneficial effect of dapagliflozin based on left ventricular ejection fraction. In the Black patients, for example, the relative benefit from dapagliflozin on the primary outcome was consistent across the full spectrum of patients with HFrEF and HFpEF.

EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved were sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). The DAPA-HF and DELIVER trials were sponsored by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). Dr. Verma has received honoraria, research support, or both from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Lilly, and from numerous other companies. Dr. Butt has been a consultant to and received travel grants from AstraZeneca, honoraria from Novartis, and has been an adviser to Bayer.

CHICAGO – Black patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) may receive more benefit from treatment with a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor than do White patients, according to a new report.

A secondary analysis of data collected from the pivotal trials that assessed the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in patients with HFrEF, EMPEROR-Reduced, and in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), EMPEROR-Preserved, was presented by Subodh Verma, MD, PhD, at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The “hypothesis-generating” analysis of data from EMPEROR-Reduced showed “a suggestion of a greater benefit of empagliflozin” in Black, compared with White patients, for the study’s primary endpoint (cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure) as well as for first and total hospitalizations for heart failure, he reported.

However, a similar but separate analysis that compared Black and White patients with heart failure who received treatment with a second agent, dapagliflozin, from the same SGLT2-inhibitor class did not show any suggestion of heterogeneity in the drug’s effect based on race.

Race-linked heterogeneity in empagliflozin’s effect

In EMPEROR-Reduced, which randomized 3,730 patients with heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less, treatment of White patients with empagliflozin (Jardiance) produced a nonsignificant 16% relative reduction in the rate of the primary endpoint, compared with placebo, during a median 16-month follow-up.

By contrast, among Black patients, treatment with empagliflozin produced a significant 56% reduction in the primary endpoint, compared with placebo-treated patients, a significant heterogeneity (P = .02) in effect between the two race subgroups, said Dr. Verma, a cardiac surgeon and professor at the University of Toronto.

The analysis he reported used combined data from EMPEROR-Reduced and the companion trial EMPEROR-Preserved, which randomized 5,988 patients with heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction greater than 40% to treatment with either empagliflozin or placebo and followed them for a median of 26 months.

To assess the effects of the randomized treatments in the two racial subgroups, Dr. Verma and associates used pooled data from both trials, but only from the 3,502 patients enrolled in the Americas, which included 3,024 White patients and 478 Black patients. Analysis of the patients in this subgroup who were randomized to placebo showed a significantly excess rate of the primary outcome among Blacks, who tallied 49% more of the primary outcome events during follow-up than did White patients, Dr. Verma reported. The absolute rate of the primary outcome without empagliflozin treatment was 13.15 events/100 patient-years of follow-up in White patients and 20.83 events/100 patient-years in Black patients.

The impact of empagliflozin was not statistically heterogeneous in the total pool of patients that included both those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF. The drug reduced the primary outcome incidence by a significant 20% in White patients, and by a significant 44% among Black patients.

But this point-estimate difference in efficacy, when coupled with the underlying difference in risk for an event between the two racial groups, meant that the number-needed-to-treat to prevent one primary outcome event was 42 among White patients and 12 among Black patients.

Race-linked treatment responses only in HFrEF

This suggestion of an imbalance in treatment efficacy was especially apparent among patients with HFrEF. In addition to the heterogeneity for the primary outcome, the Black and White subgroups also showed significantly divergent results for the outcomes of first hospitalization for heart failure, with a nonsignificant 21% relative reduction with empagliflozin treatment in Whites but a significant 65% relative cut in this endpoint with empagliflozin in Blacks, and for total hospitalizations for heart failure, which showed a similar level of significant heterogeneity between the two race subgroups.

In contrast, the patients with HFpEF showed no signal at all for heterogeneous outcome rates between Black and White subgroups.

One other study outcome, change in symptom burden measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), also showed suggestion of a race-based imbalance. The adjusted mean difference from baseline in the KCCQ clinical summary score was 1.50 points higher with empagliflozin treatment, compared with placebo among all White patients (those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF), and compared with a 5.25-point increase with empagliflozin over placebo among all Black patients with heart failure in the pooled American EMPEROR dataset, a difference between White and Black patients that just missed significance (P = .06). Again, this difference was especially notable and significant among the patients with HFrEF, where the adjusted mean difference in KCCQ was a 0.77-point increase in White patients and a 6.71-point increase among Black patients (P = .043),

These results also appeared in a report published simultaneously with Dr. Verma’s talk.

But two other analyses that assessed a possible race-based difference in empagliflozin’s effect on renal protection and on functional status showed no suggestion of heterogeneity.

Dr. Verma stressed caution about the limitations of these analyses because they involved a relatively small number of Black patients, and were possibly subject to unadjusted confounding from differences in baseline characteristics between the Black and White patients.

Black patients also had a number-needed-to-treat advantage with dapagliflozin

The finding that Black patients with heart failure potentially get more bang for the buck from treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor by having a lower number needed to treat also showed up in a separate report at the meeting that assessed the treatment effect from dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in Black and White patients in a pooled analysis of the DAPA-HF pivotal trial of patients with HFrEF and the DELIVER pivotal trial of patients with HFpEF. The pooled cohort included a total of 11,007, but for the analysis by race the investigators also limited their focus to patients from the Americas with 2,626 White patients and 381 Black patients.

Assessment of the effect of dapagliflozin on the primary outcome of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure among all patients, both those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF, again showed that event rates among patients treated with placebo were significantly higher in Black, compared with White patients, and this led to a difference in the number needed to treat to prevent one primary outcome event of 12 in Blacks and 17 in Whites, Jawad H. Butt, MD said in a talk at the meeting.

Although treatment with dapagliflozin reduced the rate of the primary outcome in this subgroup of patients from the DAPA-HF trial and the DELIVER trial by similar rates in Black and White patients, event rates were higher in the Black patients resulting in “greater benefit in absolute terms” for Black patients, explained Dr. Butt, a cardiologist at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen.

But in contrast to the empagliflozin findings reported by Dr. Verma, the combined data from the dapagliflozin trials showed no suggestion of heterogeneity in the beneficial effect of dapagliflozin based on left ventricular ejection fraction. In the Black patients, for example, the relative benefit from dapagliflozin on the primary outcome was consistent across the full spectrum of patients with HFrEF and HFpEF.

EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved were sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). The DAPA-HF and DELIVER trials were sponsored by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). Dr. Verma has received honoraria, research support, or both from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Lilly, and from numerous other companies. Dr. Butt has been a consultant to and received travel grants from AstraZeneca, honoraria from Novartis, and has been an adviser to Bayer.

CHICAGO – Black patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) may receive more benefit from treatment with a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor than do White patients, according to a new report.

A secondary analysis of data collected from the pivotal trials that assessed the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in patients with HFrEF, EMPEROR-Reduced, and in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), EMPEROR-Preserved, was presented by Subodh Verma, MD, PhD, at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The “hypothesis-generating” analysis of data from EMPEROR-Reduced showed “a suggestion of a greater benefit of empagliflozin” in Black, compared with White patients, for the study’s primary endpoint (cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure) as well as for first and total hospitalizations for heart failure, he reported.

However, a similar but separate analysis that compared Black and White patients with heart failure who received treatment with a second agent, dapagliflozin, from the same SGLT2-inhibitor class did not show any suggestion of heterogeneity in the drug’s effect based on race.

Race-linked heterogeneity in empagliflozin’s effect

In EMPEROR-Reduced, which randomized 3,730 patients with heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less, treatment of White patients with empagliflozin (Jardiance) produced a nonsignificant 16% relative reduction in the rate of the primary endpoint, compared with placebo, during a median 16-month follow-up.

By contrast, among Black patients, treatment with empagliflozin produced a significant 56% reduction in the primary endpoint, compared with placebo-treated patients, a significant heterogeneity (P = .02) in effect between the two race subgroups, said Dr. Verma, a cardiac surgeon and professor at the University of Toronto.

The analysis he reported used combined data from EMPEROR-Reduced and the companion trial EMPEROR-Preserved, which randomized 5,988 patients with heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction greater than 40% to treatment with either empagliflozin or placebo and followed them for a median of 26 months.

To assess the effects of the randomized treatments in the two racial subgroups, Dr. Verma and associates used pooled data from both trials, but only from the 3,502 patients enrolled in the Americas, which included 3,024 White patients and 478 Black patients. Analysis of the patients in this subgroup who were randomized to placebo showed a significantly excess rate of the primary outcome among Blacks, who tallied 49% more of the primary outcome events during follow-up than did White patients, Dr. Verma reported. The absolute rate of the primary outcome without empagliflozin treatment was 13.15 events/100 patient-years of follow-up in White patients and 20.83 events/100 patient-years in Black patients.

The impact of empagliflozin was not statistically heterogeneous in the total pool of patients that included both those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF. The drug reduced the primary outcome incidence by a significant 20% in White patients, and by a significant 44% among Black patients.

But this point-estimate difference in efficacy, when coupled with the underlying difference in risk for an event between the two racial groups, meant that the number-needed-to-treat to prevent one primary outcome event was 42 among White patients and 12 among Black patients.

Race-linked treatment responses only in HFrEF

This suggestion of an imbalance in treatment efficacy was especially apparent among patients with HFrEF. In addition to the heterogeneity for the primary outcome, the Black and White subgroups also showed significantly divergent results for the outcomes of first hospitalization for heart failure, with a nonsignificant 21% relative reduction with empagliflozin treatment in Whites but a significant 65% relative cut in this endpoint with empagliflozin in Blacks, and for total hospitalizations for heart failure, which showed a similar level of significant heterogeneity between the two race subgroups.

In contrast, the patients with HFpEF showed no signal at all for heterogeneous outcome rates between Black and White subgroups.

One other study outcome, change in symptom burden measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), also showed suggestion of a race-based imbalance. The adjusted mean difference from baseline in the KCCQ clinical summary score was 1.50 points higher with empagliflozin treatment, compared with placebo among all White patients (those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF), and compared with a 5.25-point increase with empagliflozin over placebo among all Black patients with heart failure in the pooled American EMPEROR dataset, a difference between White and Black patients that just missed significance (P = .06). Again, this difference was especially notable and significant among the patients with HFrEF, where the adjusted mean difference in KCCQ was a 0.77-point increase in White patients and a 6.71-point increase among Black patients (P = .043),

These results also appeared in a report published simultaneously with Dr. Verma’s talk.

But two other analyses that assessed a possible race-based difference in empagliflozin’s effect on renal protection and on functional status showed no suggestion of heterogeneity.

Dr. Verma stressed caution about the limitations of these analyses because they involved a relatively small number of Black patients, and were possibly subject to unadjusted confounding from differences in baseline characteristics between the Black and White patients.

Black patients also had a number-needed-to-treat advantage with dapagliflozin

The finding that Black patients with heart failure potentially get more bang for the buck from treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor by having a lower number needed to treat also showed up in a separate report at the meeting that assessed the treatment effect from dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in Black and White patients in a pooled analysis of the DAPA-HF pivotal trial of patients with HFrEF and the DELIVER pivotal trial of patients with HFpEF. The pooled cohort included a total of 11,007, but for the analysis by race the investigators also limited their focus to patients from the Americas with 2,626 White patients and 381 Black patients.

Assessment of the effect of dapagliflozin on the primary outcome of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure among all patients, both those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF, again showed that event rates among patients treated with placebo were significantly higher in Black, compared with White patients, and this led to a difference in the number needed to treat to prevent one primary outcome event of 12 in Blacks and 17 in Whites, Jawad H. Butt, MD said in a talk at the meeting.

Although treatment with dapagliflozin reduced the rate of the primary outcome in this subgroup of patients from the DAPA-HF trial and the DELIVER trial by similar rates in Black and White patients, event rates were higher in the Black patients resulting in “greater benefit in absolute terms” for Black patients, explained Dr. Butt, a cardiologist at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen.

But in contrast to the empagliflozin findings reported by Dr. Verma, the combined data from the dapagliflozin trials showed no suggestion of heterogeneity in the beneficial effect of dapagliflozin based on left ventricular ejection fraction. In the Black patients, for example, the relative benefit from dapagliflozin on the primary outcome was consistent across the full spectrum of patients with HFrEF and HFpEF.

EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved were sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). The DAPA-HF and DELIVER trials were sponsored by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). Dr. Verma has received honoraria, research support, or both from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Lilly, and from numerous other companies. Dr. Butt has been a consultant to and received travel grants from AstraZeneca, honoraria from Novartis, and has been an adviser to Bayer.

AT AHA 2022

Hospitals with more diverse and uninsured patients more likely to provide delayed fracture care

Regardless of individual patient-level characteristics such as race, ethnicity, or insurance status, these patients were more likely to miss the recommended 24-hour benchmark for surgery.

“Institutions that treat a less diverse patient population appeared to be more resilient to the mix of insurance status in their patient population and were more likely to meet time-to-surgery benchmarks, regardless of patient insurance status or population-based insurance mix,” write study author Ida Leah Gitajn, MD, an orthopedic trauma surgeon at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., and colleagues.

“While it is unsurprising that increased delays were associated with underfunded institutions, the association between institutional-level racial disparity and surgical delays implies structural health systems bias,” the authors wrote.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Site performance varied

Racial inequalities in health care utilization and outcomes have been documented in many medical specialties, including orthopedic trauma, the study authors write. However, previous studies evaluating racial disparities in fracture care have been limited to patient-level associations rather than hospital-level factors.

The investigators conducted a secondary analysis of prospectively collected multicenter data for 2,565 patients with hip and femur fractures enrolled in two randomized trials at 23 sites in the United States and Canada. The researchers assessed whether disparities in meeting 24-hour time-to-surgery benchmarks exist at the patient level or at the institutional level, evaluating the association of race, ethnicity, and insurance status.

The cohort study used data from the Program of Randomized Trials to Evaluate Preoperative Antiseptic Skin Solutions in Orthopaedic Trauma (PREP-IT), which enrolled patients from 2018-2021 and followed them for 1 year. All patients with hip and femur fractures enrolled in the PREP-IT program were included in the analysis, which was conducted from April to September of this year.

The cohort included 2,565 patients with an average age of about 65 years. About 82% of patients were White, 13.4% were Black, 3.2% were Asian, and 1.1% were classified as another race or ethnicity. Among the study population, 32.5% of participants were employed, and 92.2% had health insurance. Nearly 40% had a femur fracture with an average injury severity score of 10.4.

Overall, 596 patients (23.2%) didn’t meet the 24-hour time-to-operating-room benchmark. Patients who didn’t meet the 24-hour surgical window were more likely to be older, women, and have a femur fracture. They were less likely to be employed.

The 23 sites had variability in meeting the 24-hour benchmark, race and ethnicity distribution, and population-based health insurance. Institutions met benchmarks at frequencies ranging from 45.2% (for 196 of 433 procedures) to 97.4% (37 of 38 procedures). Minority race and ethnicity distribution ranged from 0% (in 99 procedures) to 58.2% (in 53 of 91 procedures). The proportion of uninsured patients ranged from 0% (in 64 procedures) to 34.2% (in 13 of 38 procedures).

At the patient level, there was no association between missing the 24-hour benchmark and race or ethnicity, and there was no independent association between hospital population racial composition and surgical delay. In an analysis that controlled for patient-level characteristics, there was no association between missing the 24-hour benchmark and patient-level insurance status.

There was an independent association, however, between the hospital population insurance coverage and hospital population racial composition as an interaction term, suggesting a moderating effect (P = .03), the study authors write.

At low rates of uninsured patients, the probability of missing the 24-hour benchmark was 12.5%-14.6% when racial composition varied from 0%-50% minority patients. In contrast, at higher rates of uninsured patients, the risk of missing the 24-hour window was higher among more diverse populations. For instance, at 30% uninsured, the risk of missing the benchmark was 0.5% when the racial composition was low and 17.6% at 50% minority patients.

Additional studies are needed to understand the findings and how health system programs or structures play a role, the authors write. For instance, well-funded health systems that care for a higher proportion of insured patients likely have quality improvement programs and other support structures, such as operating room access, that ensure appropriate time-to-surgery benchmarks for time-sensitive fractures, they say.

Addressing inequalities

Troy Amen, MD, MBA, an orthopedic surgery resident at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said, “Despite these disparities being reported and well documented in recent years, unfortunately, not enough has been done to address them or understand their fundamental root causes.”

Dr. Amen, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched racial and ethnic disparities in hip fracture surgery care across the United States. He and his colleagues found disparities in delayed time-to-surgery, particularly for Black patients.

“We live in a country and society where we want and strive for equality of care for patients regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or background,” he said. “We have a moral imperative to address these disparities as health care providers, not only among ourselves, but also in conjunction with lawmakers, hospital administrators, and health policy specialists.”

Uma Srikumaran, MD, an associate professor of orthopedic surgery at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wasn’t involved with this study but has researched racial disparities in the timing of radiographic assessment and surgical treatment of hip fractures.

“Though we understand that racial disparities are pervasive in health care, we have a great deal left to understand about the extent of those disparities and all the various factors that contribute to them,” Dr. Srikumaran told this news organization.

Dr. Srikumaran and colleagues have found that Black patients had longer wait times for evaluation and surgery than White patients.

“We all want to get to the solutions, but those can be difficult to execute without an intricate understanding of the problem,” he said. “We should encourage this type of research all throughout health care in general but also very locally, as solutions are not likely to be one-size-fits-all.”

Dr. Srikumaran pointed to the need to measure the problem in specific pathologies, populations, geographies, hospital types, and other factors.

“Studying the trends of this issue will help us determine whether our national or local initiatives are making a difference and which interventions are most effective for a particular hospital, geographic location, or particular pathology,” he said. “Accordingly, if a particular hospital or health system isn’t looking at differences in the delivery of care by race, they are missing an opportunity to ensure equity and raise overall quality.”

The study was supported by funding from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Gitajn reported receiving personal fees for consulting and teaching work from Stryker outside the submitted work. Dr. Amen and Dr. Srikumaran reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Regardless of individual patient-level characteristics such as race, ethnicity, or insurance status, these patients were more likely to miss the recommended 24-hour benchmark for surgery.

“Institutions that treat a less diverse patient population appeared to be more resilient to the mix of insurance status in their patient population and were more likely to meet time-to-surgery benchmarks, regardless of patient insurance status or population-based insurance mix,” write study author Ida Leah Gitajn, MD, an orthopedic trauma surgeon at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., and colleagues.

“While it is unsurprising that increased delays were associated with underfunded institutions, the association between institutional-level racial disparity and surgical delays implies structural health systems bias,” the authors wrote.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Site performance varied

Racial inequalities in health care utilization and outcomes have been documented in many medical specialties, including orthopedic trauma, the study authors write. However, previous studies evaluating racial disparities in fracture care have been limited to patient-level associations rather than hospital-level factors.

The investigators conducted a secondary analysis of prospectively collected multicenter data for 2,565 patients with hip and femur fractures enrolled in two randomized trials at 23 sites in the United States and Canada. The researchers assessed whether disparities in meeting 24-hour time-to-surgery benchmarks exist at the patient level or at the institutional level, evaluating the association of race, ethnicity, and insurance status.

The cohort study used data from the Program of Randomized Trials to Evaluate Preoperative Antiseptic Skin Solutions in Orthopaedic Trauma (PREP-IT), which enrolled patients from 2018-2021 and followed them for 1 year. All patients with hip and femur fractures enrolled in the PREP-IT program were included in the analysis, which was conducted from April to September of this year.

The cohort included 2,565 patients with an average age of about 65 years. About 82% of patients were White, 13.4% were Black, 3.2% were Asian, and 1.1% were classified as another race or ethnicity. Among the study population, 32.5% of participants were employed, and 92.2% had health insurance. Nearly 40% had a femur fracture with an average injury severity score of 10.4.

Overall, 596 patients (23.2%) didn’t meet the 24-hour time-to-operating-room benchmark. Patients who didn’t meet the 24-hour surgical window were more likely to be older, women, and have a femur fracture. They were less likely to be employed.

The 23 sites had variability in meeting the 24-hour benchmark, race and ethnicity distribution, and population-based health insurance. Institutions met benchmarks at frequencies ranging from 45.2% (for 196 of 433 procedures) to 97.4% (37 of 38 procedures). Minority race and ethnicity distribution ranged from 0% (in 99 procedures) to 58.2% (in 53 of 91 procedures). The proportion of uninsured patients ranged from 0% (in 64 procedures) to 34.2% (in 13 of 38 procedures).

At the patient level, there was no association between missing the 24-hour benchmark and race or ethnicity, and there was no independent association between hospital population racial composition and surgical delay. In an analysis that controlled for patient-level characteristics, there was no association between missing the 24-hour benchmark and patient-level insurance status.

There was an independent association, however, between the hospital population insurance coverage and hospital population racial composition as an interaction term, suggesting a moderating effect (P = .03), the study authors write.

At low rates of uninsured patients, the probability of missing the 24-hour benchmark was 12.5%-14.6% when racial composition varied from 0%-50% minority patients. In contrast, at higher rates of uninsured patients, the risk of missing the 24-hour window was higher among more diverse populations. For instance, at 30% uninsured, the risk of missing the benchmark was 0.5% when the racial composition was low and 17.6% at 50% minority patients.

Additional studies are needed to understand the findings and how health system programs or structures play a role, the authors write. For instance, well-funded health systems that care for a higher proportion of insured patients likely have quality improvement programs and other support structures, such as operating room access, that ensure appropriate time-to-surgery benchmarks for time-sensitive fractures, they say.

Addressing inequalities

Troy Amen, MD, MBA, an orthopedic surgery resident at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said, “Despite these disparities being reported and well documented in recent years, unfortunately, not enough has been done to address them or understand their fundamental root causes.”

Dr. Amen, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched racial and ethnic disparities in hip fracture surgery care across the United States. He and his colleagues found disparities in delayed time-to-surgery, particularly for Black patients.

“We live in a country and society where we want and strive for equality of care for patients regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or background,” he said. “We have a moral imperative to address these disparities as health care providers, not only among ourselves, but also in conjunction with lawmakers, hospital administrators, and health policy specialists.”

Uma Srikumaran, MD, an associate professor of orthopedic surgery at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wasn’t involved with this study but has researched racial disparities in the timing of radiographic assessment and surgical treatment of hip fractures.

“Though we understand that racial disparities are pervasive in health care, we have a great deal left to understand about the extent of those disparities and all the various factors that contribute to them,” Dr. Srikumaran told this news organization.

Dr. Srikumaran and colleagues have found that Black patients had longer wait times for evaluation and surgery than White patients.

“We all want to get to the solutions, but those can be difficult to execute without an intricate understanding of the problem,” he said. “We should encourage this type of research all throughout health care in general but also very locally, as solutions are not likely to be one-size-fits-all.”

Dr. Srikumaran pointed to the need to measure the problem in specific pathologies, populations, geographies, hospital types, and other factors.

“Studying the trends of this issue will help us determine whether our national or local initiatives are making a difference and which interventions are most effective for a particular hospital, geographic location, or particular pathology,” he said. “Accordingly, if a particular hospital or health system isn’t looking at differences in the delivery of care by race, they are missing an opportunity to ensure equity and raise overall quality.”

The study was supported by funding from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Gitajn reported receiving personal fees for consulting and teaching work from Stryker outside the submitted work. Dr. Amen and Dr. Srikumaran reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Regardless of individual patient-level characteristics such as race, ethnicity, or insurance status, these patients were more likely to miss the recommended 24-hour benchmark for surgery.

“Institutions that treat a less diverse patient population appeared to be more resilient to the mix of insurance status in their patient population and were more likely to meet time-to-surgery benchmarks, regardless of patient insurance status or population-based insurance mix,” write study author Ida Leah Gitajn, MD, an orthopedic trauma surgeon at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., and colleagues.

“While it is unsurprising that increased delays were associated with underfunded institutions, the association between institutional-level racial disparity and surgical delays implies structural health systems bias,” the authors wrote.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Site performance varied

Racial inequalities in health care utilization and outcomes have been documented in many medical specialties, including orthopedic trauma, the study authors write. However, previous studies evaluating racial disparities in fracture care have been limited to patient-level associations rather than hospital-level factors.

The investigators conducted a secondary analysis of prospectively collected multicenter data for 2,565 patients with hip and femur fractures enrolled in two randomized trials at 23 sites in the United States and Canada. The researchers assessed whether disparities in meeting 24-hour time-to-surgery benchmarks exist at the patient level or at the institutional level, evaluating the association of race, ethnicity, and insurance status.

The cohort study used data from the Program of Randomized Trials to Evaluate Preoperative Antiseptic Skin Solutions in Orthopaedic Trauma (PREP-IT), which enrolled patients from 2018-2021 and followed them for 1 year. All patients with hip and femur fractures enrolled in the PREP-IT program were included in the analysis, which was conducted from April to September of this year.

The cohort included 2,565 patients with an average age of about 65 years. About 82% of patients were White, 13.4% were Black, 3.2% were Asian, and 1.1% were classified as another race or ethnicity. Among the study population, 32.5% of participants were employed, and 92.2% had health insurance. Nearly 40% had a femur fracture with an average injury severity score of 10.4.

Overall, 596 patients (23.2%) didn’t meet the 24-hour time-to-operating-room benchmark. Patients who didn’t meet the 24-hour surgical window were more likely to be older, women, and have a femur fracture. They were less likely to be employed.

The 23 sites had variability in meeting the 24-hour benchmark, race and ethnicity distribution, and population-based health insurance. Institutions met benchmarks at frequencies ranging from 45.2% (for 196 of 433 procedures) to 97.4% (37 of 38 procedures). Minority race and ethnicity distribution ranged from 0% (in 99 procedures) to 58.2% (in 53 of 91 procedures). The proportion of uninsured patients ranged from 0% (in 64 procedures) to 34.2% (in 13 of 38 procedures).

At the patient level, there was no association between missing the 24-hour benchmark and race or ethnicity, and there was no independent association between hospital population racial composition and surgical delay. In an analysis that controlled for patient-level characteristics, there was no association between missing the 24-hour benchmark and patient-level insurance status.

There was an independent association, however, between the hospital population insurance coverage and hospital population racial composition as an interaction term, suggesting a moderating effect (P = .03), the study authors write.

At low rates of uninsured patients, the probability of missing the 24-hour benchmark was 12.5%-14.6% when racial composition varied from 0%-50% minority patients. In contrast, at higher rates of uninsured patients, the risk of missing the 24-hour window was higher among more diverse populations. For instance, at 30% uninsured, the risk of missing the benchmark was 0.5% when the racial composition was low and 17.6% at 50% minority patients.

Additional studies are needed to understand the findings and how health system programs or structures play a role, the authors write. For instance, well-funded health systems that care for a higher proportion of insured patients likely have quality improvement programs and other support structures, such as operating room access, that ensure appropriate time-to-surgery benchmarks for time-sensitive fractures, they say.

Addressing inequalities

Troy Amen, MD, MBA, an orthopedic surgery resident at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said, “Despite these disparities being reported and well documented in recent years, unfortunately, not enough has been done to address them or understand their fundamental root causes.”

Dr. Amen, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched racial and ethnic disparities in hip fracture surgery care across the United States. He and his colleagues found disparities in delayed time-to-surgery, particularly for Black patients.

“We live in a country and society where we want and strive for equality of care for patients regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or background,” he said. “We have a moral imperative to address these disparities as health care providers, not only among ourselves, but also in conjunction with lawmakers, hospital administrators, and health policy specialists.”

Uma Srikumaran, MD, an associate professor of orthopedic surgery at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wasn’t involved with this study but has researched racial disparities in the timing of radiographic assessment and surgical treatment of hip fractures.

“Though we understand that racial disparities are pervasive in health care, we have a great deal left to understand about the extent of those disparities and all the various factors that contribute to them,” Dr. Srikumaran told this news organization.

Dr. Srikumaran and colleagues have found that Black patients had longer wait times for evaluation and surgery than White patients.

“We all want to get to the solutions, but those can be difficult to execute without an intricate understanding of the problem,” he said. “We should encourage this type of research all throughout health care in general but also very locally, as solutions are not likely to be one-size-fits-all.”

Dr. Srikumaran pointed to the need to measure the problem in specific pathologies, populations, geographies, hospital types, and other factors.

“Studying the trends of this issue will help us determine whether our national or local initiatives are making a difference and which interventions are most effective for a particular hospital, geographic location, or particular pathology,” he said. “Accordingly, if a particular hospital or health system isn’t looking at differences in the delivery of care by race, they are missing an opportunity to ensure equity and raise overall quality.”

The study was supported by funding from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Gitajn reported receiving personal fees for consulting and teaching work from Stryker outside the submitted work. Dr. Amen and Dr. Srikumaran reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Medical degree program put on probation for ‘infrastructure’ issues

after a national accrediting agency’s onsite survey uncovered “infrastructure” problems earlier this year. Those include faculty shortages and inadequate student access to financial aid as well as to career and wellness counseling.

The inspection was conducted by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), an accrediting body sponsored by the Association of American Medical Colleges and the American Medical Association.

While participation is voluntary, institutions must comply with 12 standards to maintain their standing. These include hiring qualified faculty and providing students with financial aid and debt management counseling.

Jeannette South-Paul, MD, Meharry’s senior vice president and chief academic officer, said in an interview that the degree program remains fully accredited despite the fact that LCME representatives found “notable areas of concern,” including the “need for some infrastructure updates and additional educational and financial resources for students.”

Specifically, students did not have sufficient access to advising services, broadband internet, and study spaces. In addition, faculty shortages caused delays in student evaluations, she said.

The new status does not affect the ability of students to complete their medical degrees or residency programs, she said. Dr. South-Paul added that school officials have begun addressing several of the issues and anticipate a swift resolution “guided by an aggressive action plan over the next 18-24 months.”

The university, located in Nashville, Tenn., has had accreditation problems before. In January, following a site visit and low scores on annual resident surveys, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) placed several of the schools’ residency and fellowship programs on probationary status.

At the time, school officials said that all programs would remain accredited, and they committed to expanding available resources, such as hiring additional staff and an independent expert to make program recommendations. A follow-up site visit was scheduled for August.

Regarding the most recent accreditation challenges, Veronica M. Catanese, MD, MBA, co-secretary of LCME, said the organization could only disclose the accreditation status of a medical school.

“LCME is not able to discuss any details concerning the accreditation of individual medical education programs, including the review process, resulting decisions, or survey results,” she said.

Established medical education programs typically undergo a self-study process and a full survey visit every 8 years. According to LCME’s website, a full survey visit may be conducted sooner if concerns arise about the program’s quality or sustainability.

The LCME program directory lists Meharry Medical College’s accreditation status as “full, on probation.” The next survey visit is scheduled for the 2023-2024 school year.

LCME accreditation is a prerequisite for having access to federal grants and programs, such as Title VII funding, which helps increase minority participation in health care careers. In addition, most state licensure boards and ACGME-affiliated residency programs require applicants to graduate from an LCME-accredited school.

Last year, when Meharry Medical College received pandemic aid money as part of the CARES Act, the school distributed nearly $10 million in scholarships to students – many of whom come from modest-income families and struggle to afford college tuition.

But in general, endowments to historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are often at least 70% smaller than those made to non-HBCUs, which raises the question: Does the lack of funding make it more difficult for schools such as Meharry to maintain accreditation standards?

“Many different factors played into this finding by LCME,” said Dr. South-Paul. “It is a well-known fact that HBCUs have historically not been as well funded or possess the same size endowments as their mainstream academic peers. That is true of Meharry, but it would not be accurate to say this probation is because we are an HBCU.”

Similarly, Dr. Catanese said there is no evidence that HBCUs and non-HBCUs differ in their ability to meet LCME accreditation standards.

About half of the school’s residency and fellowship programs continue to have accreditation problems. According to ACGME’s database, the internal medicine program is currently on “continued accreditation with warning” status. The psychiatry and ob.gyn. programs are on “probationary accreditation” after receiving warnings in previous years.

Meharry was chartered in 1915 but was founded in 1876 as one of the first medical schools in the South for Black Americans.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

after a national accrediting agency’s onsite survey uncovered “infrastructure” problems earlier this year. Those include faculty shortages and inadequate student access to financial aid as well as to career and wellness counseling.

The inspection was conducted by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), an accrediting body sponsored by the Association of American Medical Colleges and the American Medical Association.

While participation is voluntary, institutions must comply with 12 standards to maintain their standing. These include hiring qualified faculty and providing students with financial aid and debt management counseling.

Jeannette South-Paul, MD, Meharry’s senior vice president and chief academic officer, said in an interview that the degree program remains fully accredited despite the fact that LCME representatives found “notable areas of concern,” including the “need for some infrastructure updates and additional educational and financial resources for students.”

Specifically, students did not have sufficient access to advising services, broadband internet, and study spaces. In addition, faculty shortages caused delays in student evaluations, she said.

The new status does not affect the ability of students to complete their medical degrees or residency programs, she said. Dr. South-Paul added that school officials have begun addressing several of the issues and anticipate a swift resolution “guided by an aggressive action plan over the next 18-24 months.”

The university, located in Nashville, Tenn., has had accreditation problems before. In January, following a site visit and low scores on annual resident surveys, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) placed several of the schools’ residency and fellowship programs on probationary status.

At the time, school officials said that all programs would remain accredited, and they committed to expanding available resources, such as hiring additional staff and an independent expert to make program recommendations. A follow-up site visit was scheduled for August.

Regarding the most recent accreditation challenges, Veronica M. Catanese, MD, MBA, co-secretary of LCME, said the organization could only disclose the accreditation status of a medical school.

“LCME is not able to discuss any details concerning the accreditation of individual medical education programs, including the review process, resulting decisions, or survey results,” she said.

Established medical education programs typically undergo a self-study process and a full survey visit every 8 years. According to LCME’s website, a full survey visit may be conducted sooner if concerns arise about the program’s quality or sustainability.

The LCME program directory lists Meharry Medical College’s accreditation status as “full, on probation.” The next survey visit is scheduled for the 2023-2024 school year.

LCME accreditation is a prerequisite for having access to federal grants and programs, such as Title VII funding, which helps increase minority participation in health care careers. In addition, most state licensure boards and ACGME-affiliated residency programs require applicants to graduate from an LCME-accredited school.

Last year, when Meharry Medical College received pandemic aid money as part of the CARES Act, the school distributed nearly $10 million in scholarships to students – many of whom come from modest-income families and struggle to afford college tuition.

But in general, endowments to historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are often at least 70% smaller than those made to non-HBCUs, which raises the question: Does the lack of funding make it more difficult for schools such as Meharry to maintain accreditation standards?

“Many different factors played into this finding by LCME,” said Dr. South-Paul. “It is a well-known fact that HBCUs have historically not been as well funded or possess the same size endowments as their mainstream academic peers. That is true of Meharry, but it would not be accurate to say this probation is because we are an HBCU.”

Similarly, Dr. Catanese said there is no evidence that HBCUs and non-HBCUs differ in their ability to meet LCME accreditation standards.

About half of the school’s residency and fellowship programs continue to have accreditation problems. According to ACGME’s database, the internal medicine program is currently on “continued accreditation with warning” status. The psychiatry and ob.gyn. programs are on “probationary accreditation” after receiving warnings in previous years.

Meharry was chartered in 1915 but was founded in 1876 as one of the first medical schools in the South for Black Americans.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

after a national accrediting agency’s onsite survey uncovered “infrastructure” problems earlier this year. Those include faculty shortages and inadequate student access to financial aid as well as to career and wellness counseling.

The inspection was conducted by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), an accrediting body sponsored by the Association of American Medical Colleges and the American Medical Association.

While participation is voluntary, institutions must comply with 12 standards to maintain their standing. These include hiring qualified faculty and providing students with financial aid and debt management counseling.

Jeannette South-Paul, MD, Meharry’s senior vice president and chief academic officer, said in an interview that the degree program remains fully accredited despite the fact that LCME representatives found “notable areas of concern,” including the “need for some infrastructure updates and additional educational and financial resources for students.”

Specifically, students did not have sufficient access to advising services, broadband internet, and study spaces. In addition, faculty shortages caused delays in student evaluations, she said.

The new status does not affect the ability of students to complete their medical degrees or residency programs, she said. Dr. South-Paul added that school officials have begun addressing several of the issues and anticipate a swift resolution “guided by an aggressive action plan over the next 18-24 months.”

The university, located in Nashville, Tenn., has had accreditation problems before. In January, following a site visit and low scores on annual resident surveys, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) placed several of the schools’ residency and fellowship programs on probationary status.

At the time, school officials said that all programs would remain accredited, and they committed to expanding available resources, such as hiring additional staff and an independent expert to make program recommendations. A follow-up site visit was scheduled for August.

Regarding the most recent accreditation challenges, Veronica M. Catanese, MD, MBA, co-secretary of LCME, said the organization could only disclose the accreditation status of a medical school.

“LCME is not able to discuss any details concerning the accreditation of individual medical education programs, including the review process, resulting decisions, or survey results,” she said.

Established medical education programs typically undergo a self-study process and a full survey visit every 8 years. According to LCME’s website, a full survey visit may be conducted sooner if concerns arise about the program’s quality or sustainability.

The LCME program directory lists Meharry Medical College’s accreditation status as “full, on probation.” The next survey visit is scheduled for the 2023-2024 school year.

LCME accreditation is a prerequisite for having access to federal grants and programs, such as Title VII funding, which helps increase minority participation in health care careers. In addition, most state licensure boards and ACGME-affiliated residency programs require applicants to graduate from an LCME-accredited school.

Last year, when Meharry Medical College received pandemic aid money as part of the CARES Act, the school distributed nearly $10 million in scholarships to students – many of whom come from modest-income families and struggle to afford college tuition.

But in general, endowments to historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are often at least 70% smaller than those made to non-HBCUs, which raises the question: Does the lack of funding make it more difficult for schools such as Meharry to maintain accreditation standards?

“Many different factors played into this finding by LCME,” said Dr. South-Paul. “It is a well-known fact that HBCUs have historically not been as well funded or possess the same size endowments as their mainstream academic peers. That is true of Meharry, but it would not be accurate to say this probation is because we are an HBCU.”

Similarly, Dr. Catanese said there is no evidence that HBCUs and non-HBCUs differ in their ability to meet LCME accreditation standards.

About half of the school’s residency and fellowship programs continue to have accreditation problems. According to ACGME’s database, the internal medicine program is currently on “continued accreditation with warning” status. The psychiatry and ob.gyn. programs are on “probationary accreditation” after receiving warnings in previous years.

Meharry was chartered in 1915 but was founded in 1876 as one of the first medical schools in the South for Black Americans.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

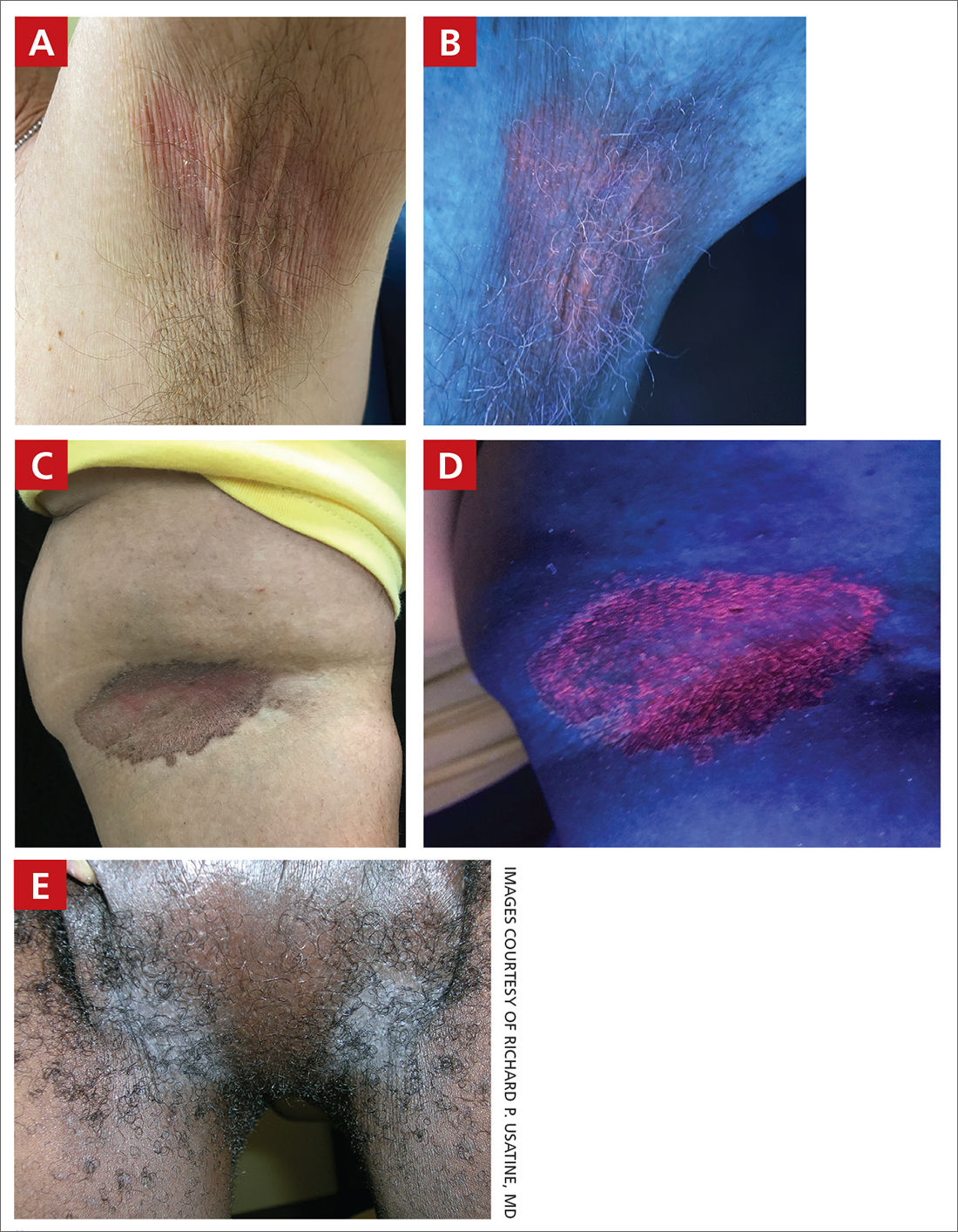

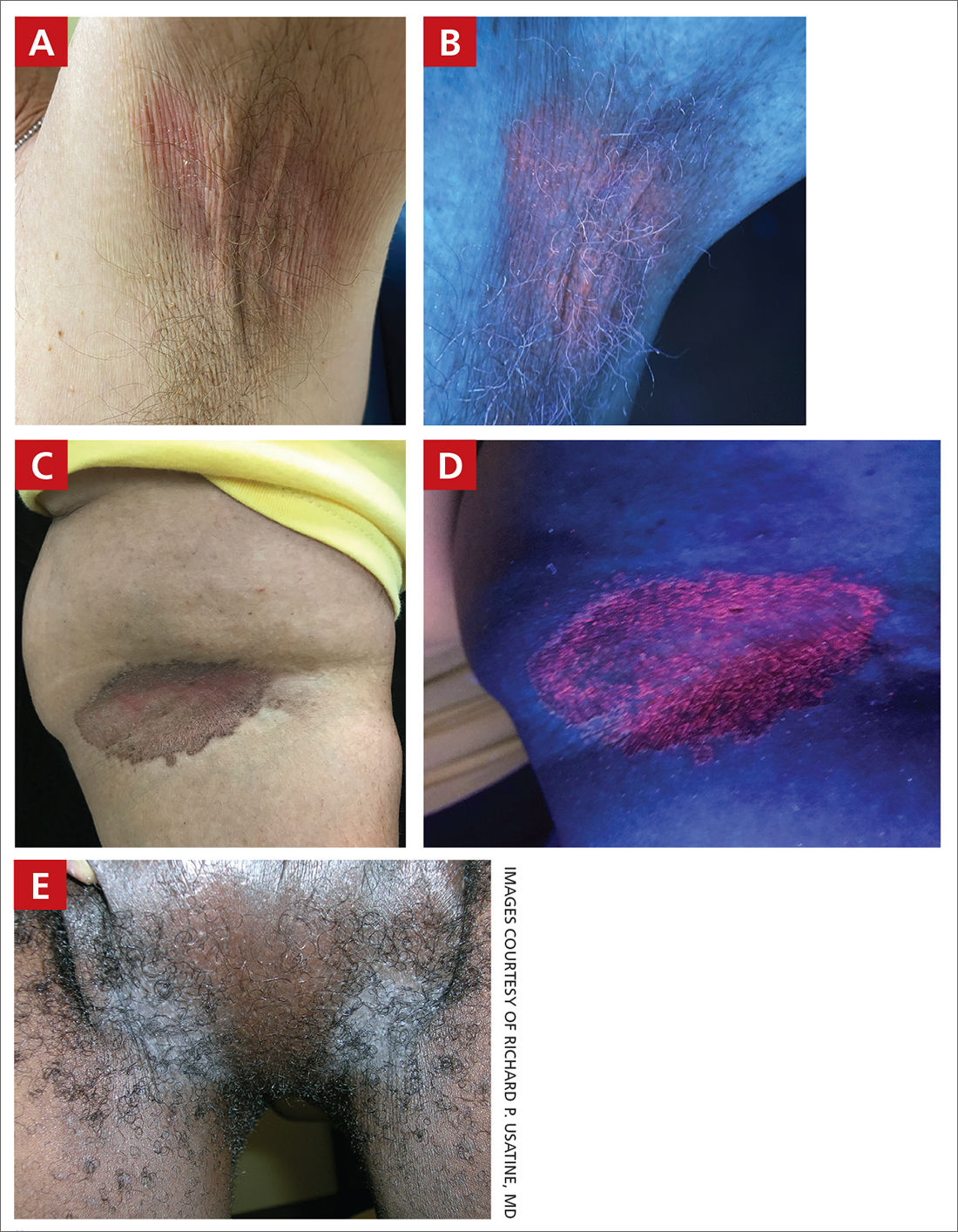

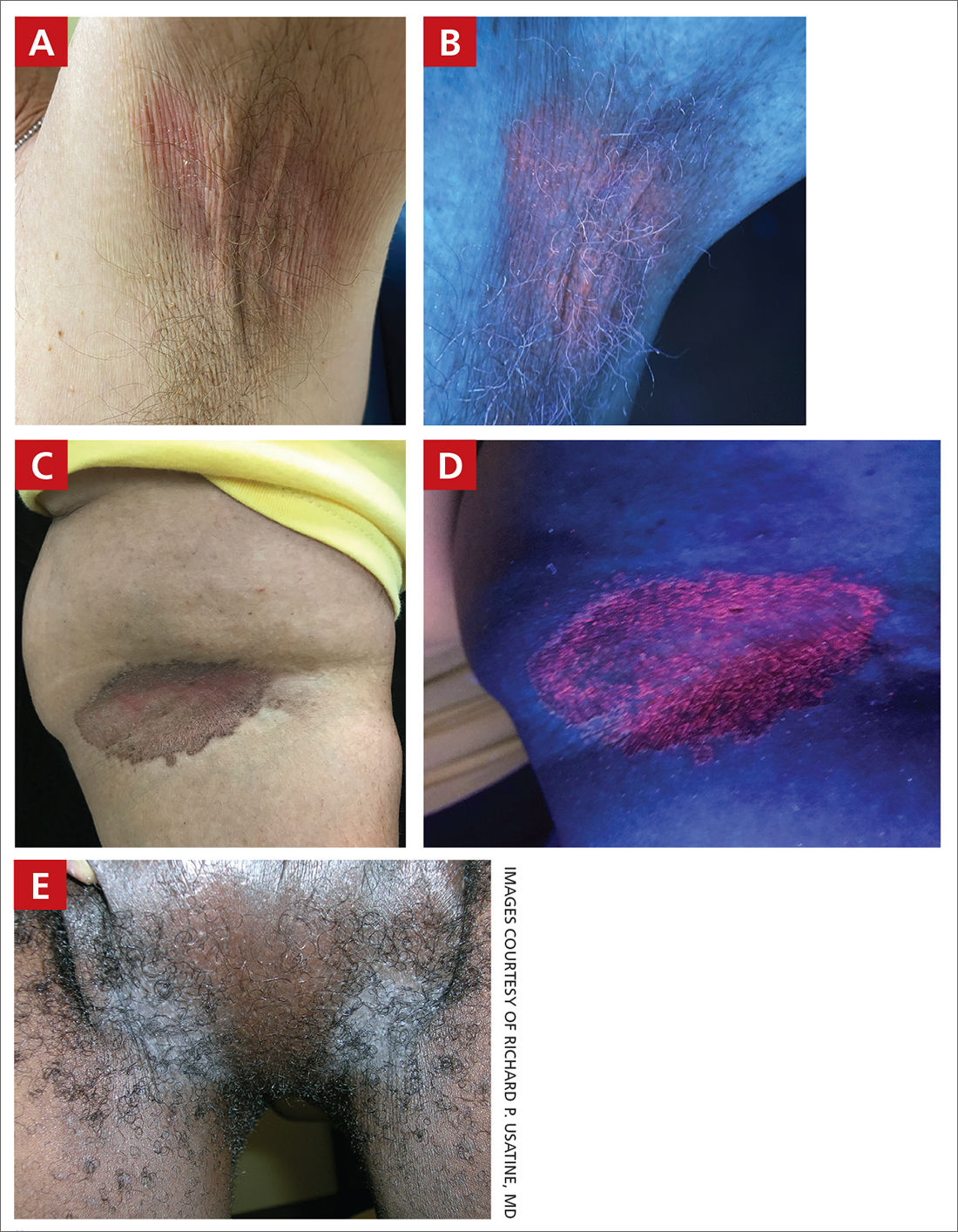

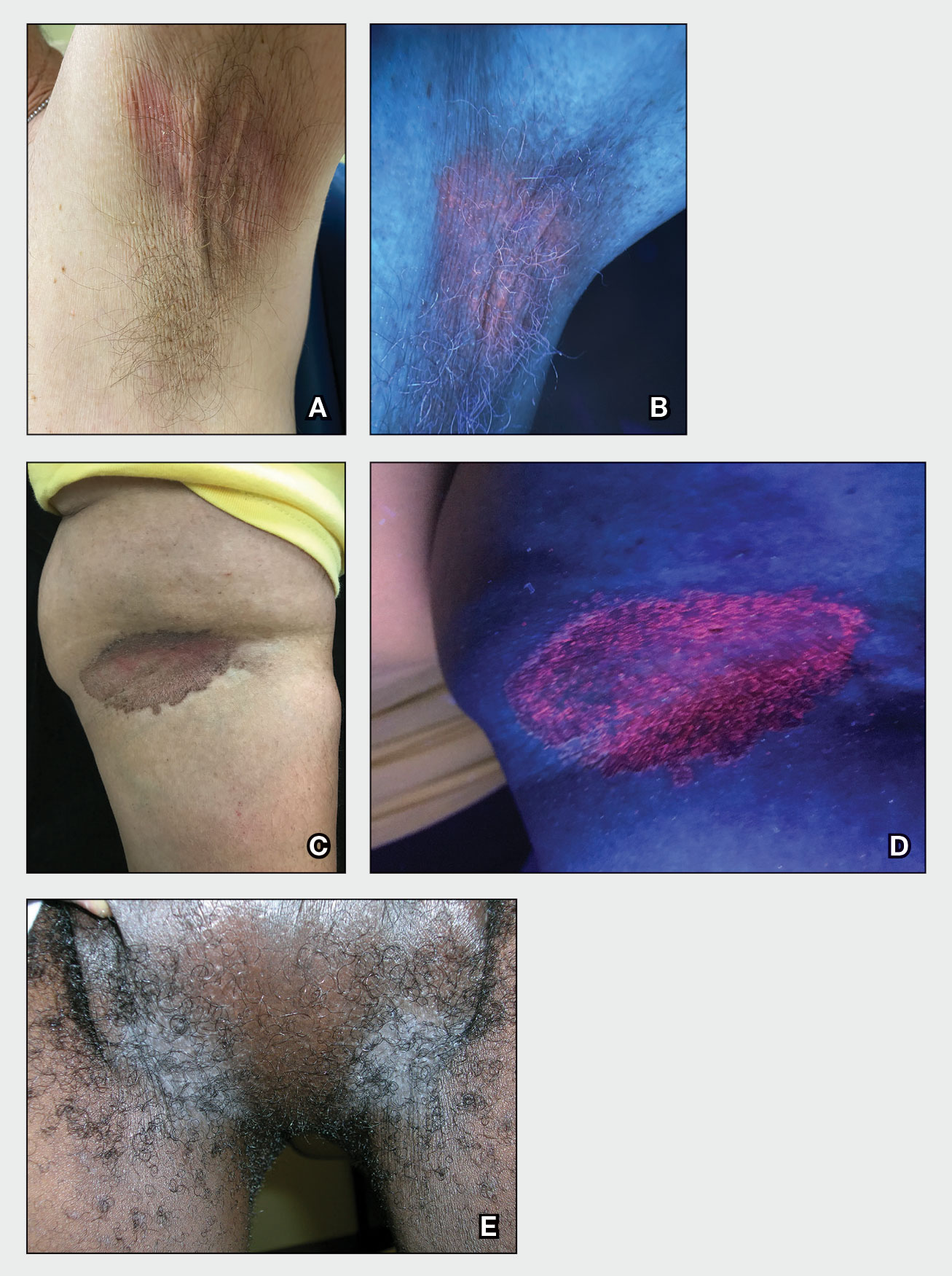

Updated materials and mentoring can boost diversity in dermatology

LAS VEGAS – in the specialty.

The growing ethnic minority population in the United States “underscores the need for medical education to ensure dermatologists are prepared to provide quality care for patients of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds,” said Dr. Taylor, the Bernett L. Johnson Jr., MD, Professor, and vice chair for diversity, equity, and inclusion in the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania.

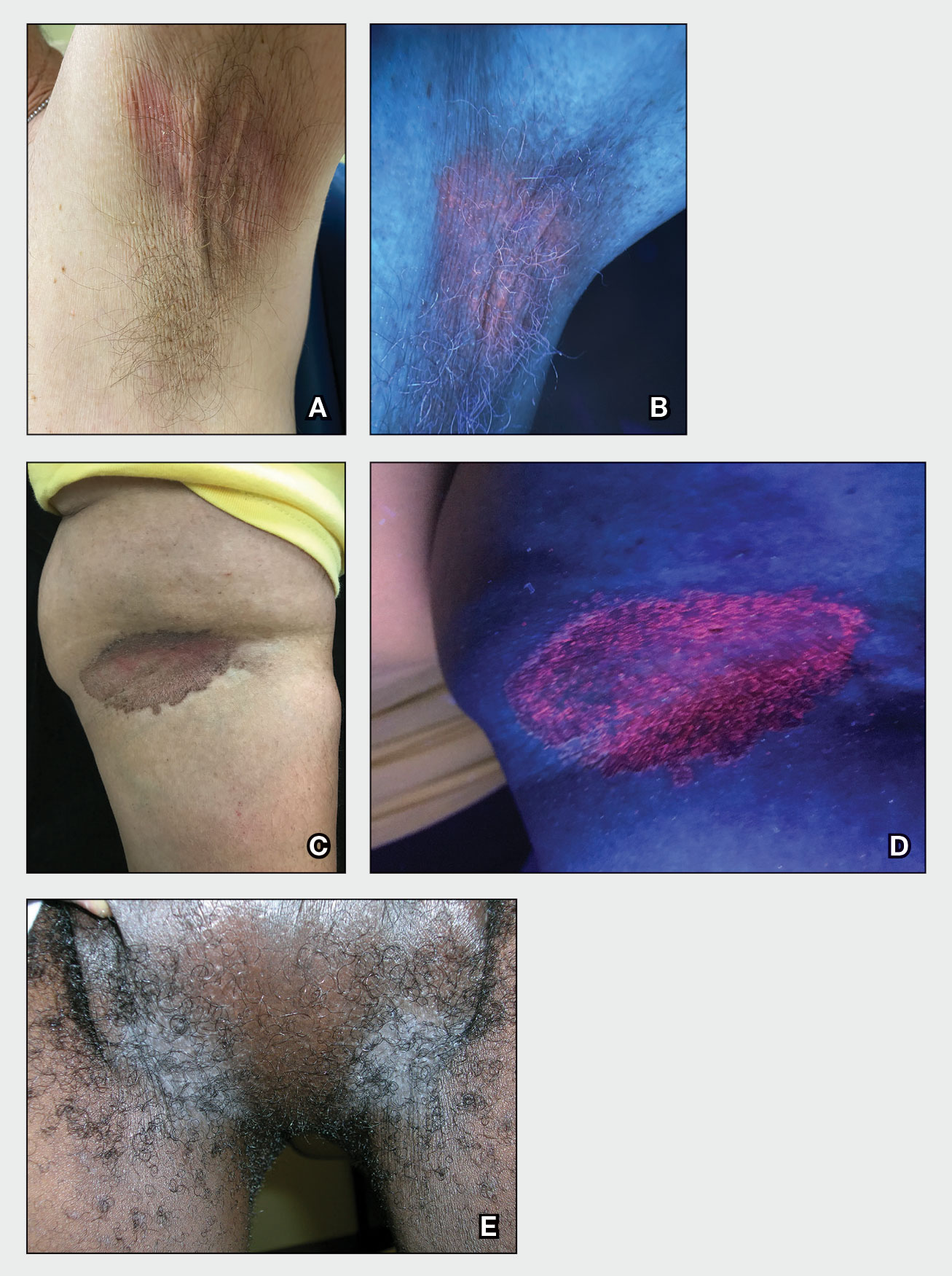

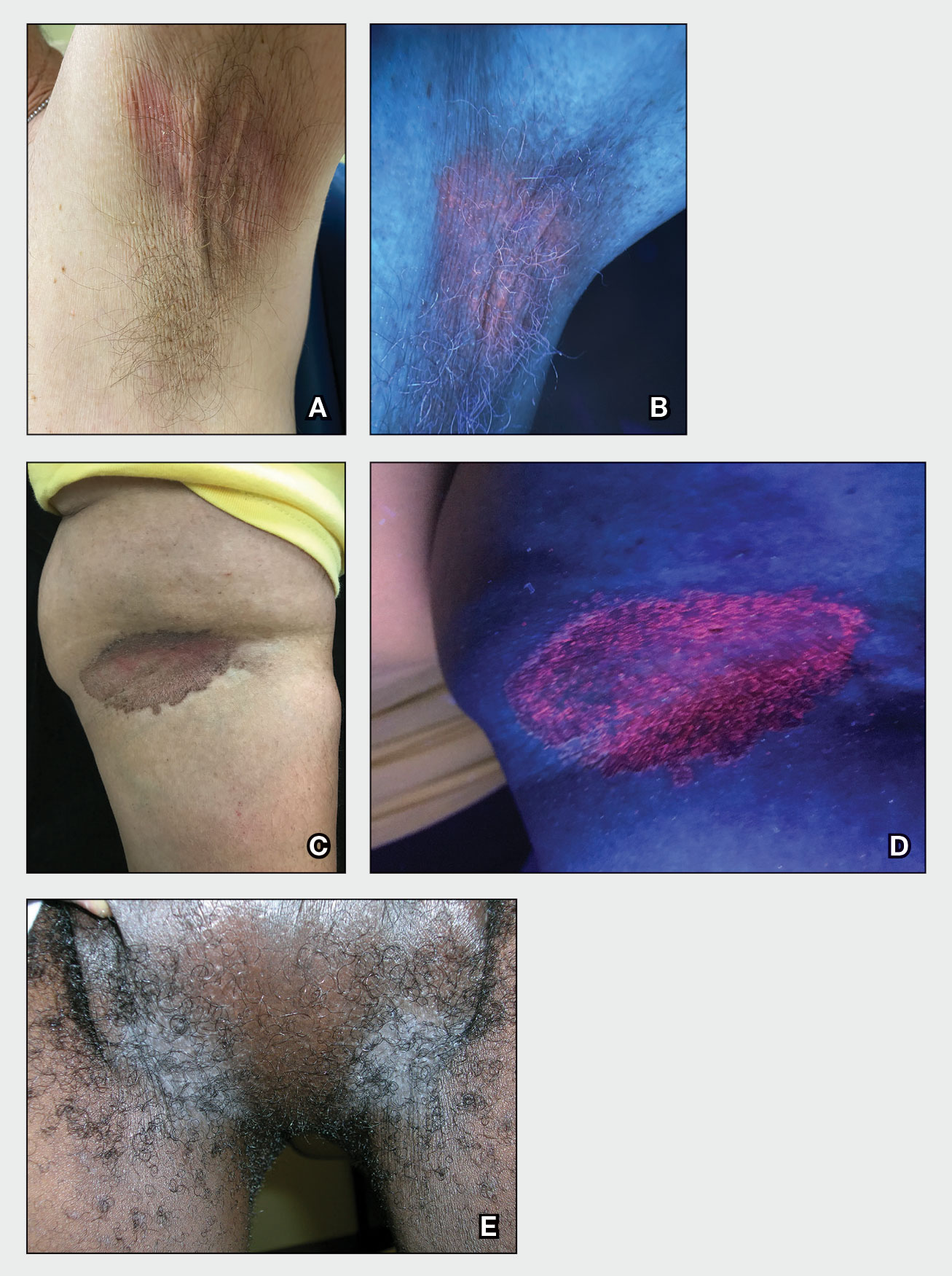

Improving education includes diversifying resource material, she said. A recent study in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology showed the representation of skin tones on Google searches for skin conditions was mostly light skin (91.7%), although non-Hispanic Whites account for less than two-thirds (approximately 60%) of the U.S. population, she said. Many people with darker skin tones “are not finding people who look like themselves” when they search skin conditions online, she noted.

The lack of diversity in images occurs not only on Google, “but in our textbooks, which are the foundational resources for our students,” said Nada M. Elbuluk, MD, founder and director of the Skin of Color and Pigmentary Disorders Program at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. She also established the Dermatology Diversity and Inclusion Program at USC.

The underrepresentation of teaching images, combined with the lack of data on epidemiology and treatment, can translate to poorer quality of care for skin of color patients and contribute to more misdiagnoses in these populations, Dr. Elbuluk emphasized.

Cultural competency and workforce diversity are ongoing issues in dermatology, added Valerie D. Callender, MD, professor of dermatology at Howard University, Washington, and medical director of the Callender Dermatology & Cosmetic Center in Glenn Dale, Md.

“We know that patients of color seek physicians of color,” she said. “We need to target our residents’ interest in dermatology,” and all physicians need to be comfortable with treating patients of all races, she added.

Although more than 13% of Americans are Black, only 3% of dermatologists in the United States are Black, Dr. Callender noted. Similarly, 4.2% of dermatologists in the United States are Hispanic or Latino, but these groups make up more than 18% of the general U.S. population, according to a recent study, she said.

Cheryl M. Burgess, MD, founder and medical director of the Center for Dermatology and Dermatologic Surgery in Washington, presented a roadmap of strategies for improving diversity in dermatology, starting with increasing STEM education at the high school and college levels among all populations and increasing the pipeline of underrepresented students to medical schools.

Then, faculty should work to increase interest in dermatology among underrepresented medical students and increase the numbers of underrepresented medical students in dermatology residency programs, said Dr. Burgess, assistant clinical professor of dermatology at Georgetown University and George Washington University, Washington.

“The more diversity we have in our specialty, the more we learn from each other,” and increased diversity can promote new research questions, said Andrew F. Alexis, MD, vice chair for diversity and inclusion in the department of dermatology and professor of clinical dermatology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Increasing the diversity of populations in clinical trials is another important strategy to improve diversity in dermatology, he emphasized.

Mentoring is an excellent way to help underrepresented students develop and pursue a career in dermatology, the panelists agreed. Time is precious for everyone, so don’t hesitate to use Zoom and other technology to help connect with mentees, Dr. Burgess advised.

Dr. Taylor added that mentoring doesn’t have to be a huge time commitment, it can be as simple as volunteering once a year at a school career forum. “It is so gratifying to have these young people looking up to you,” she said.

The panelists disclosed relationships with multiple companies, but none were relevant to this panel discussion. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – in the specialty.

The growing ethnic minority population in the United States “underscores the need for medical education to ensure dermatologists are prepared to provide quality care for patients of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds,” said Dr. Taylor, the Bernett L. Johnson Jr., MD, Professor, and vice chair for diversity, equity, and inclusion in the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Improving education includes diversifying resource material, she said. A recent study in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology showed the representation of skin tones on Google searches for skin conditions was mostly light skin (91.7%), although non-Hispanic Whites account for less than two-thirds (approximately 60%) of the U.S. population, she said. Many people with darker skin tones “are not finding people who look like themselves” when they search skin conditions online, she noted.

The lack of diversity in images occurs not only on Google, “but in our textbooks, which are the foundational resources for our students,” said Nada M. Elbuluk, MD, founder and director of the Skin of Color and Pigmentary Disorders Program at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. She also established the Dermatology Diversity and Inclusion Program at USC.

The underrepresentation of teaching images, combined with the lack of data on epidemiology and treatment, can translate to poorer quality of care for skin of color patients and contribute to more misdiagnoses in these populations, Dr. Elbuluk emphasized.

Cultural competency and workforce diversity are ongoing issues in dermatology, added Valerie D. Callender, MD, professor of dermatology at Howard University, Washington, and medical director of the Callender Dermatology & Cosmetic Center in Glenn Dale, Md.

“We know that patients of color seek physicians of color,” she said. “We need to target our residents’ interest in dermatology,” and all physicians need to be comfortable with treating patients of all races, she added.

Although more than 13% of Americans are Black, only 3% of dermatologists in the United States are Black, Dr. Callender noted. Similarly, 4.2% of dermatologists in the United States are Hispanic or Latino, but these groups make up more than 18% of the general U.S. population, according to a recent study, she said.

Cheryl M. Burgess, MD, founder and medical director of the Center for Dermatology and Dermatologic Surgery in Washington, presented a roadmap of strategies for improving diversity in dermatology, starting with increasing STEM education at the high school and college levels among all populations and increasing the pipeline of underrepresented students to medical schools.

Then, faculty should work to increase interest in dermatology among underrepresented medical students and increase the numbers of underrepresented medical students in dermatology residency programs, said Dr. Burgess, assistant clinical professor of dermatology at Georgetown University and George Washington University, Washington.

“The more diversity we have in our specialty, the more we learn from each other,” and increased diversity can promote new research questions, said Andrew F. Alexis, MD, vice chair for diversity and inclusion in the department of dermatology and professor of clinical dermatology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Increasing the diversity of populations in clinical trials is another important strategy to improve diversity in dermatology, he emphasized.

Mentoring is an excellent way to help underrepresented students develop and pursue a career in dermatology, the panelists agreed. Time is precious for everyone, so don’t hesitate to use Zoom and other technology to help connect with mentees, Dr. Burgess advised.

Dr. Taylor added that mentoring doesn’t have to be a huge time commitment, it can be as simple as volunteering once a year at a school career forum. “It is so gratifying to have these young people looking up to you,” she said.

The panelists disclosed relationships with multiple companies, but none were relevant to this panel discussion. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – in the specialty.

The growing ethnic minority population in the United States “underscores the need for medical education to ensure dermatologists are prepared to provide quality care for patients of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds,” said Dr. Taylor, the Bernett L. Johnson Jr., MD, Professor, and vice chair for diversity, equity, and inclusion in the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Improving education includes diversifying resource material, she said. A recent study in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology showed the representation of skin tones on Google searches for skin conditions was mostly light skin (91.7%), although non-Hispanic Whites account for less than two-thirds (approximately 60%) of the U.S. population, she said. Many people with darker skin tones “are not finding people who look like themselves” when they search skin conditions online, she noted.

The lack of diversity in images occurs not only on Google, “but in our textbooks, which are the foundational resources for our students,” said Nada M. Elbuluk, MD, founder and director of the Skin of Color and Pigmentary Disorders Program at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. She also established the Dermatology Diversity and Inclusion Program at USC.

The underrepresentation of teaching images, combined with the lack of data on epidemiology and treatment, can translate to poorer quality of care for skin of color patients and contribute to more misdiagnoses in these populations, Dr. Elbuluk emphasized.

Cultural competency and workforce diversity are ongoing issues in dermatology, added Valerie D. Callender, MD, professor of dermatology at Howard University, Washington, and medical director of the Callender Dermatology & Cosmetic Center in Glenn Dale, Md.

“We know that patients of color seek physicians of color,” she said. “We need to target our residents’ interest in dermatology,” and all physicians need to be comfortable with treating patients of all races, she added.

Although more than 13% of Americans are Black, only 3% of dermatologists in the United States are Black, Dr. Callender noted. Similarly, 4.2% of dermatologists in the United States are Hispanic or Latino, but these groups make up more than 18% of the general U.S. population, according to a recent study, she said.

Cheryl M. Burgess, MD, founder and medical director of the Center for Dermatology and Dermatologic Surgery in Washington, presented a roadmap of strategies for improving diversity in dermatology, starting with increasing STEM education at the high school and college levels among all populations and increasing the pipeline of underrepresented students to medical schools.

Then, faculty should work to increase interest in dermatology among underrepresented medical students and increase the numbers of underrepresented medical students in dermatology residency programs, said Dr. Burgess, assistant clinical professor of dermatology at Georgetown University and George Washington University, Washington.

“The more diversity we have in our specialty, the more we learn from each other,” and increased diversity can promote new research questions, said Andrew F. Alexis, MD, vice chair for diversity and inclusion in the department of dermatology and professor of clinical dermatology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Increasing the diversity of populations in clinical trials is another important strategy to improve diversity in dermatology, he emphasized.

Mentoring is an excellent way to help underrepresented students develop and pursue a career in dermatology, the panelists agreed. Time is precious for everyone, so don’t hesitate to use Zoom and other technology to help connect with mentees, Dr. Burgess advised.

Dr. Taylor added that mentoring doesn’t have to be a huge time commitment, it can be as simple as volunteering once a year at a school career forum. “It is so gratifying to have these young people looking up to you,” she said.

The panelists disclosed relationships with multiple companies, but none were relevant to this panel discussion. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

AT INNOVATIONS IN DERMATOLOGY

Significant racial disparities persist in status epilepticus

NASHVILLE, Tenn. – Investigators found that among Black patients with status epilepticus, the hospitalization rate was twice that of their White counterparts. Other findings reveal age and income disparities.

“The results suggest that racial minorities, those with a lower income, and the elderly are an appropriate target to improve health outcomes and reduce health inequality,” said Gabriela Tantillo Sepúlveda, MD, assistant professor of neurology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

An examination of outcomes

Status epilepticus is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality. Disparities in epilepsy care have previously been described, but little attention has been paid to the contribution of disparities to status epilepticus care and associated outcomes.

Researchers used 2010-2019 data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, a database covering a cross-section of hospitalizations in 48 states and the District of Columbia. From relevant diagnostic codes, they calculated status epilepticus prevalence as the rate per 10,000 hospitalizations and stratified this by demographics.

Over the study period, investigators identified 486,861 status epilepticus hospitalizations, most (71.3%) at urban teaching hospitals.

Status epilepticus prevalence was highest for non-Hispanic Black patients, at 27.3, followed by non-Hispanic others, at 16.1, Hispanic patients, at 15.8, and non-Hispanic-White patients, at 13.7 (P < .01).

The finding that Black patients had double the rate as White patients was “definitely surprising,” said Dr. Tantillo Sepúlveda.

Research over the past 20 years revealed similar disparities related to status epilepticus, “so it’s upsetting that these disparities have persisted. Unfortunately, we still have a lot of work to do to reduce health inequalities,” she said.

The investigators found that the prevalence of status epilepticus was higher in the lowest-income quartile, compared with the highest (18.7 vs. 14; P < .01).

Need for physician advocacy

Unlike previous studies, this research assessed various interventions in different age groups and showed that the likelihood of intubation, tracheostomy, gastrostomy, and in-hospital mortality increased with age.

For example, compared with the reference group (patients aged 18-39 years), the odds of intubation were 1.22 (95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.27) for those aged 40-59 years and 1.48 (95% CI, 1.42-1.54) for those aged 60-79. Those aged 80 and older were most likely to be intubated, at an odds ratio of 1.5 (95% CI, 1.43-1.58).

Elderly patients were most likely to undergo tracheostomy (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.75-2.27), gastrostomy (OR, 3.37; 95% CI, 2.97-3.83), and to experience in-hospital mortality (OR, 6.51; 95% CI, 5.95-7.13), compared with the youngest patients.

These intervention rates also varied by racial/ethnic groups. Minority populations, particularly Black people, had higher odds of tracheostomy and gastrostomy, compared with non-Hispanic White persons.

The odds of undergoing electroencephalography monitoring progressively rose as income level increased (OR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.34-1.62) for the highest income quartile versus the lowest quartile. The odds of undergoing EEG monitoring were also higher at urban teaching hospitals than at rural hospitals.

Tackling these disparities in this patient population include increasing resources, personnel, and health education aimed at minorities, low-income patients, and the elderly, said Dr. Tantillo Sepúlveda. She added that more research is needed “to determine the most effective ways of accomplishing this goal.”

The medical community can help reduce disparities, said Dr. Tantillo Sepúlveda, by working to improve health literacy, to reduce stigma associated with seizures, and to increase awareness of seizure risk factors.