User login

Children and COVID: Nearly 200,000 new cases reported in 1 week

, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Available state data show that 198,551 child COVID cases were added during the week of Dec. 17-23 – up by 16.8% from the nearly 170,000 new cases reported the previous week and the highest 7-day figure since Sept. 17-23, when 207,000 cases were reported, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report. Since Oct. 22-28, when the weekly count dropped to a seasonal low, the weekly count has nearly doubled.

The largest shares of the nearly 199,000 new cases were divided pretty equally between the Northeast and the South, while the West had just a small bump in cases and the Midwest was in the middle. The largest statewide percent increases came in the New England states, along with New Jersey, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. New York State does not report age ranges for COVID cases, the AAP/CHA report noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions are following a similar trend, as both have risen considerably over the last 2 months, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

COVID-related ED visits for children aged 0-11 years – measured as a proportion of all ED visits – are nearing the pandemic high of 4.1% set in late August, while visits in 12- to 15-year-olds have risen from 1.4% in early November to 5.6% on Dec. 24 and 16- to 17-year-olds have gone from 1.5% to 6% over the same period of time, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

As for hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 years, the rate was down to 0.19 per 100,000 population on Nov. 11 but had risen to 0.38 per 100,000 as of Dec. 24. The highest point reached in children during the pandemic was 0.46 per 100,000 in early September, the CDC said.

On Dec. 23, 367 children were admitted to hospitals in the United States, the highest number since Sept. 7, when 374 were hospitalized. The highest 1-day total over the course of the pandemic, 394, came just a week before that, Aug. 31, according to the Department of Health & Human Services.

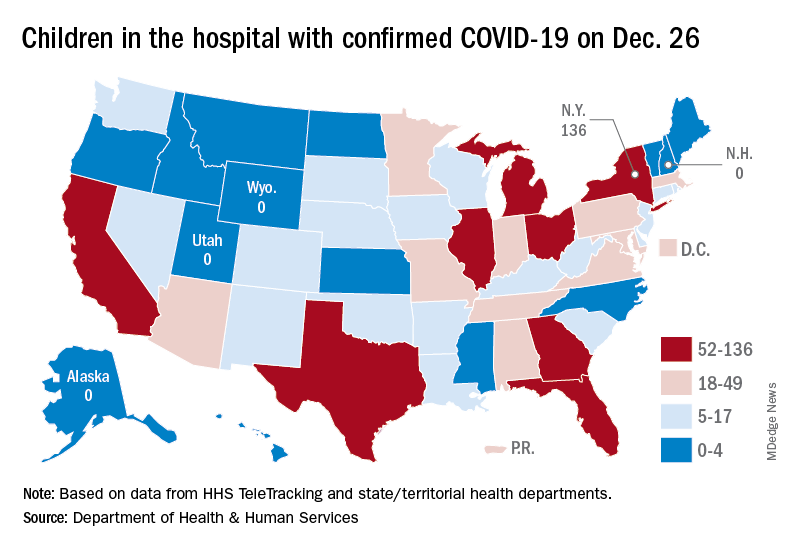

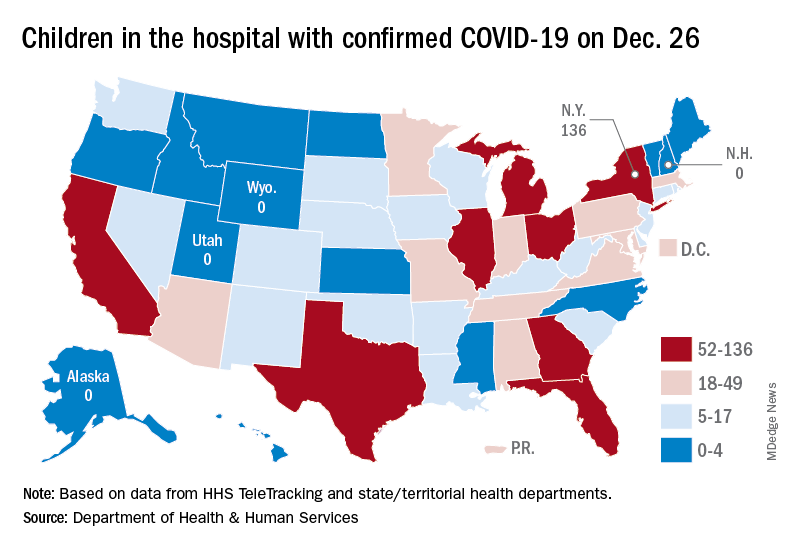

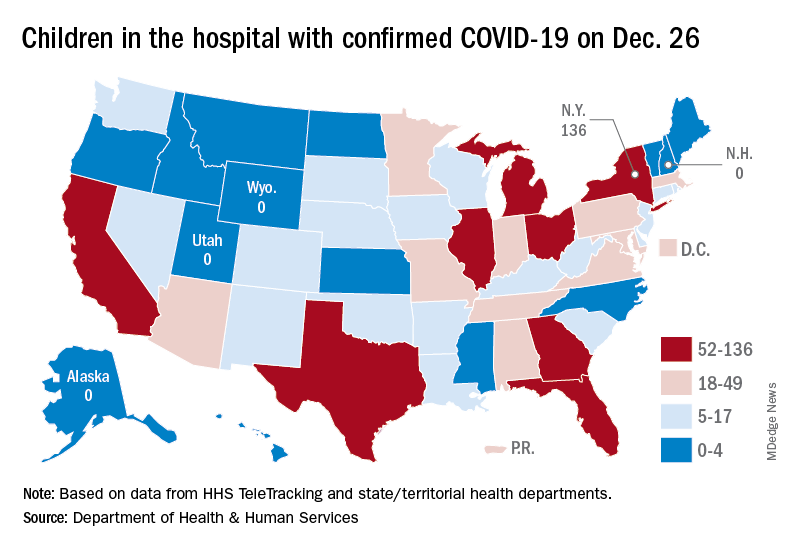

A look at the most recent HHS data shows that 1,161 children were being hospitalized in pediatric inpatient beds with confirmed COVID-19 on Dec. 26. The highest number by state was in New York (136), followed by Texas (90) and Illinois and Ohio, both with 83. There were four states – Alaska, New Hampshire, Utah, and Wyoming – with no hospitalized children, the HHS said. Puerto Rico, meanwhile, had 28 children in the hospital with COVID, more than 38 states.

, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Available state data show that 198,551 child COVID cases were added during the week of Dec. 17-23 – up by 16.8% from the nearly 170,000 new cases reported the previous week and the highest 7-day figure since Sept. 17-23, when 207,000 cases were reported, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report. Since Oct. 22-28, when the weekly count dropped to a seasonal low, the weekly count has nearly doubled.

The largest shares of the nearly 199,000 new cases were divided pretty equally between the Northeast and the South, while the West had just a small bump in cases and the Midwest was in the middle. The largest statewide percent increases came in the New England states, along with New Jersey, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. New York State does not report age ranges for COVID cases, the AAP/CHA report noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions are following a similar trend, as both have risen considerably over the last 2 months, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

COVID-related ED visits for children aged 0-11 years – measured as a proportion of all ED visits – are nearing the pandemic high of 4.1% set in late August, while visits in 12- to 15-year-olds have risen from 1.4% in early November to 5.6% on Dec. 24 and 16- to 17-year-olds have gone from 1.5% to 6% over the same period of time, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

As for hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 years, the rate was down to 0.19 per 100,000 population on Nov. 11 but had risen to 0.38 per 100,000 as of Dec. 24. The highest point reached in children during the pandemic was 0.46 per 100,000 in early September, the CDC said.

On Dec. 23, 367 children were admitted to hospitals in the United States, the highest number since Sept. 7, when 374 were hospitalized. The highest 1-day total over the course of the pandemic, 394, came just a week before that, Aug. 31, according to the Department of Health & Human Services.

A look at the most recent HHS data shows that 1,161 children were being hospitalized in pediatric inpatient beds with confirmed COVID-19 on Dec. 26. The highest number by state was in New York (136), followed by Texas (90) and Illinois and Ohio, both with 83. There were four states – Alaska, New Hampshire, Utah, and Wyoming – with no hospitalized children, the HHS said. Puerto Rico, meanwhile, had 28 children in the hospital with COVID, more than 38 states.

, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Available state data show that 198,551 child COVID cases were added during the week of Dec. 17-23 – up by 16.8% from the nearly 170,000 new cases reported the previous week and the highest 7-day figure since Sept. 17-23, when 207,000 cases were reported, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report. Since Oct. 22-28, when the weekly count dropped to a seasonal low, the weekly count has nearly doubled.

The largest shares of the nearly 199,000 new cases were divided pretty equally between the Northeast and the South, while the West had just a small bump in cases and the Midwest was in the middle. The largest statewide percent increases came in the New England states, along with New Jersey, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. New York State does not report age ranges for COVID cases, the AAP/CHA report noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions are following a similar trend, as both have risen considerably over the last 2 months, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

COVID-related ED visits for children aged 0-11 years – measured as a proportion of all ED visits – are nearing the pandemic high of 4.1% set in late August, while visits in 12- to 15-year-olds have risen from 1.4% in early November to 5.6% on Dec. 24 and 16- to 17-year-olds have gone from 1.5% to 6% over the same period of time, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

As for hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 years, the rate was down to 0.19 per 100,000 population on Nov. 11 but had risen to 0.38 per 100,000 as of Dec. 24. The highest point reached in children during the pandemic was 0.46 per 100,000 in early September, the CDC said.

On Dec. 23, 367 children were admitted to hospitals in the United States, the highest number since Sept. 7, when 374 were hospitalized. The highest 1-day total over the course of the pandemic, 394, came just a week before that, Aug. 31, according to the Department of Health & Human Services.

A look at the most recent HHS data shows that 1,161 children were being hospitalized in pediatric inpatient beds with confirmed COVID-19 on Dec. 26. The highest number by state was in New York (136), followed by Texas (90) and Illinois and Ohio, both with 83. There were four states – Alaska, New Hampshire, Utah, and Wyoming – with no hospitalized children, the HHS said. Puerto Rico, meanwhile, had 28 children in the hospital with COVID, more than 38 states.

Most cancer patients with breakthrough COVID-19 infection experience severe outcomes

Of 54 fully vaccinated patients with cancer and COVID-19, 35 (65%) were hospitalized, 10 (19%) were admitted to the intensive care unit or required mechanical ventilation, and 7 (13%) died within 30 days.

Although the study did not assess the rate of breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated patients with cancer, the findings do underscore the need for continued vigilance in protecting this vulnerable patient population by vaccinating close contacts, administering boosters, social distancing, and mask-wearing.

“Overall, vaccination remains an invaluable strategy in protecting vulnerable populations, including patients with cancer, against COVID-19. However, patients with cancer who develop breakthrough infection despite full vaccination remain at risk of severe outcomes,” Andrew L. Schmidt, MB, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and associates wrote.

The analysis, which appeared online in Annals of Oncology Dec. 24 as a pre-proof but has not yet been peer reviewed, analyzed registry data from 1,787 adults with current or prior invasive cancer and laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 between Nov. 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, before COVID vaccination was widespread. Of those, 1,656 (93%) were unvaccinated, 77 (4%) were partially vaccinated, and 54 (3%) were considered fully vaccinated at the time of COVID-19 infection.

Of the fully vaccinated patients with breakthrough infection, 52 (96%) experienced a severe outcome: two-thirds had to be hospitalized, nearly 1 in 5 went to the ICU or needed mechanical ventilation, and 13% died within 30 days.

“Comparable rates were observed in the unvaccinated group,” the investigators write, adding that there was no statistical difference in 30-day mortality between the fully vaccinated patients and the unvaccinated cohort (adjusted odds ratio, 1.08).

Factors associated with increased 30-day mortality among unvaccinated patients included lymphopenia (aOR, 1.68), comorbidities (aORs, 1.66-2.10), worse performance status (aORs, 2.26-4.34), and baseline cancer status (active/progressing vs. not active/ progressing, aOR, 6.07).

No significant differences were observed in ICU, mechanical ventilation, or hospitalization rates between the vaccinated and unvaccinated cohort after adjustment for confounders (aORs,1.13 and 1.25, respectively).

Notably, patients with an underlying hematologic malignancy were overrepresented among those with breakthrough COVID-19 (35% vs. 20%). Compared with those with solid cancers, patients with hematologic malignancies also had significantly higher rates of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and hospitalization.

This finding is “consistent with evidence that these patients may have a blunted serologic response to vaccination secondary to disease or therapy,” the authors note.

Although the investigators did not evaluate the risk of breakthrough infection post vaccination, recent research indicates that receiving a COVID-19 booster increases antibody levels among patients with cancer under active treatment and thus may provide additional protection against the virus.

Given the risk of breakthrough infection and severe outcomes in patients with cancer, the authors propose that “a mitigation approach that includes vaccination of close contacts, boosters, social distancing, and mask-wearing in public should be continued for the foreseeable future.” However, “additional research is needed to further categorize the patients that remain at risk of symptomatic COVID-19 following vaccination and test strategies that may reduce this risk.”

The findings are from a pre-proof that has not yet been peer reviewed or published. First author Dr. Schmidt reported nonfinancial support from Astellas, nonfinancial support from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. Other coauthors reported a range of disclosures as well. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Of 54 fully vaccinated patients with cancer and COVID-19, 35 (65%) were hospitalized, 10 (19%) were admitted to the intensive care unit or required mechanical ventilation, and 7 (13%) died within 30 days.

Although the study did not assess the rate of breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated patients with cancer, the findings do underscore the need for continued vigilance in protecting this vulnerable patient population by vaccinating close contacts, administering boosters, social distancing, and mask-wearing.

“Overall, vaccination remains an invaluable strategy in protecting vulnerable populations, including patients with cancer, against COVID-19. However, patients with cancer who develop breakthrough infection despite full vaccination remain at risk of severe outcomes,” Andrew L. Schmidt, MB, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and associates wrote.

The analysis, which appeared online in Annals of Oncology Dec. 24 as a pre-proof but has not yet been peer reviewed, analyzed registry data from 1,787 adults with current or prior invasive cancer and laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 between Nov. 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, before COVID vaccination was widespread. Of those, 1,656 (93%) were unvaccinated, 77 (4%) were partially vaccinated, and 54 (3%) were considered fully vaccinated at the time of COVID-19 infection.

Of the fully vaccinated patients with breakthrough infection, 52 (96%) experienced a severe outcome: two-thirds had to be hospitalized, nearly 1 in 5 went to the ICU or needed mechanical ventilation, and 13% died within 30 days.

“Comparable rates were observed in the unvaccinated group,” the investigators write, adding that there was no statistical difference in 30-day mortality between the fully vaccinated patients and the unvaccinated cohort (adjusted odds ratio, 1.08).

Factors associated with increased 30-day mortality among unvaccinated patients included lymphopenia (aOR, 1.68), comorbidities (aORs, 1.66-2.10), worse performance status (aORs, 2.26-4.34), and baseline cancer status (active/progressing vs. not active/ progressing, aOR, 6.07).

No significant differences were observed in ICU, mechanical ventilation, or hospitalization rates between the vaccinated and unvaccinated cohort after adjustment for confounders (aORs,1.13 and 1.25, respectively).

Notably, patients with an underlying hematologic malignancy were overrepresented among those with breakthrough COVID-19 (35% vs. 20%). Compared with those with solid cancers, patients with hematologic malignancies also had significantly higher rates of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and hospitalization.

This finding is “consistent with evidence that these patients may have a blunted serologic response to vaccination secondary to disease or therapy,” the authors note.

Although the investigators did not evaluate the risk of breakthrough infection post vaccination, recent research indicates that receiving a COVID-19 booster increases antibody levels among patients with cancer under active treatment and thus may provide additional protection against the virus.

Given the risk of breakthrough infection and severe outcomes in patients with cancer, the authors propose that “a mitigation approach that includes vaccination of close contacts, boosters, social distancing, and mask-wearing in public should be continued for the foreseeable future.” However, “additional research is needed to further categorize the patients that remain at risk of symptomatic COVID-19 following vaccination and test strategies that may reduce this risk.”

The findings are from a pre-proof that has not yet been peer reviewed or published. First author Dr. Schmidt reported nonfinancial support from Astellas, nonfinancial support from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. Other coauthors reported a range of disclosures as well. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Of 54 fully vaccinated patients with cancer and COVID-19, 35 (65%) were hospitalized, 10 (19%) were admitted to the intensive care unit or required mechanical ventilation, and 7 (13%) died within 30 days.

Although the study did not assess the rate of breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated patients with cancer, the findings do underscore the need for continued vigilance in protecting this vulnerable patient population by vaccinating close contacts, administering boosters, social distancing, and mask-wearing.

“Overall, vaccination remains an invaluable strategy in protecting vulnerable populations, including patients with cancer, against COVID-19. However, patients with cancer who develop breakthrough infection despite full vaccination remain at risk of severe outcomes,” Andrew L. Schmidt, MB, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and associates wrote.

The analysis, which appeared online in Annals of Oncology Dec. 24 as a pre-proof but has not yet been peer reviewed, analyzed registry data from 1,787 adults with current or prior invasive cancer and laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 between Nov. 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, before COVID vaccination was widespread. Of those, 1,656 (93%) were unvaccinated, 77 (4%) were partially vaccinated, and 54 (3%) were considered fully vaccinated at the time of COVID-19 infection.

Of the fully vaccinated patients with breakthrough infection, 52 (96%) experienced a severe outcome: two-thirds had to be hospitalized, nearly 1 in 5 went to the ICU or needed mechanical ventilation, and 13% died within 30 days.

“Comparable rates were observed in the unvaccinated group,” the investigators write, adding that there was no statistical difference in 30-day mortality between the fully vaccinated patients and the unvaccinated cohort (adjusted odds ratio, 1.08).

Factors associated with increased 30-day mortality among unvaccinated patients included lymphopenia (aOR, 1.68), comorbidities (aORs, 1.66-2.10), worse performance status (aORs, 2.26-4.34), and baseline cancer status (active/progressing vs. not active/ progressing, aOR, 6.07).

No significant differences were observed in ICU, mechanical ventilation, or hospitalization rates between the vaccinated and unvaccinated cohort after adjustment for confounders (aORs,1.13 and 1.25, respectively).

Notably, patients with an underlying hematologic malignancy were overrepresented among those with breakthrough COVID-19 (35% vs. 20%). Compared with those with solid cancers, patients with hematologic malignancies also had significantly higher rates of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and hospitalization.

This finding is “consistent with evidence that these patients may have a blunted serologic response to vaccination secondary to disease or therapy,” the authors note.

Although the investigators did not evaluate the risk of breakthrough infection post vaccination, recent research indicates that receiving a COVID-19 booster increases antibody levels among patients with cancer under active treatment and thus may provide additional protection against the virus.

Given the risk of breakthrough infection and severe outcomes in patients with cancer, the authors propose that “a mitigation approach that includes vaccination of close contacts, boosters, social distancing, and mask-wearing in public should be continued for the foreseeable future.” However, “additional research is needed to further categorize the patients that remain at risk of symptomatic COVID-19 following vaccination and test strategies that may reduce this risk.”

The findings are from a pre-proof that has not yet been peer reviewed or published. First author Dr. Schmidt reported nonfinancial support from Astellas, nonfinancial support from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. Other coauthors reported a range of disclosures as well. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF ONCOLOGY

COVID-19–associated ocular mucormycosis outbreak case study reveals high-risk group for deadly complication

Earlier this year, hospitals in India were dealing not only with the coronavirus pandemic but also with a surge in a potentially lethal fungal infection in patients previously treated for COVID-19. Mucormycosis, also known as black fungus, is typically a rare infection, but India had recorded more than 45,000 cases as of July 2021.

Now, a recent report suggests that patients with COVID-19–associated rhino-orbital cerebral mucormycosis (CAM) may have a higher mortality rate than previously estimated. The study was published Dec. 9 in JAMA Ophthalmology.

“The mortality indicators we observed, such as assisted ventilation and presence of severe orbital manifestations, can help physicians triage patients for emergency procedures, such as functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS), and administer systemic antifungal agents when in short supply,” the study authors wrote.

Mucormycosis usually infects immunocompromised patients. Previous research has found that poorly controlled diabetes – an epidemic in India – and use of high-dose systemic corticosteroids are two main risk factors for developing CAM. Even before COVID-19, India had a high incidence of mucormycosis compared to other countries, but cases exist around the world. In fact, on Dec. 17, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 10 isolated cases of COVID-19–associated mucormycosis identified in Arkansas hospitals between July and September 2021.

The disease can cause blurred vision, black lesions on the nose or inside of the mouth, and facial swelling. In rhino-orbital cerebral mucormycosis, extensive infection can necessitate orbital exenteration surgery, a disfiguring procedure that typically involves removal of the entire contents of the bony eye socket, as well as removal of the sinuses. Estimates for the mortality rate for this disease range from 14% to nearly 80%.

To better understand the cumulative morality rates for CAM and to identify additional risk factors, researchers reviewed the medical records of patients diagnosed and treated for CAM at a tertiary care multispecialty government hospital in Maharashtra, a state in the west-central region of India. The analysis included patients who died after admission or who had at minimum 30 days of documented follow-up. All diagnoses occurred between March 1 and May 30, 2021. All patients underwent comprehensive ophthalmic exams and routine blood workups.

Seventy-three patients were included in the study, with the average age of 53.5 years; 66% of the patients were male, and 74% of all patients had diabetes. Of the 47 individuals with available COVID-19 vaccination information, 89% had not had either shot of the vaccine, and 11% had the first dose. No patients in the cohort had received both doses of the vaccine; 87% of the patients were previously hospitalized for COVID-19, with 43 needing supplemental oxygen, 14 receiving noninvasive ventilation and ventilator support (NIV), and three requiring mechanical ventilation.

Patients developed CAM a median of 28 days after being discharged from the hospital for COVID-19 treatment; 26 patients died, 18 patients underwent FESS, and five underwent orbital exenteration. While 36% of patients died overall, the researchers found the cumulative probability of death from CAM rose from 26% at day 7 to 53% at day 21. They also found that the patients who died had more severe COVID-19, indicated by more days spent on supplemental oxygen (P = .003) and increased need for NIV or mechanical ventilation (P = .02) compared to patients who survived CAM. Those who died also had poorer visual acuity, with 35% of the group having no light perception during examination compared to 6% of surviving CAM patients (P = .02).

These findings are largely “confirmatory to what we previously knew, which is that [CAM] is a very bad disease with high morbidity and high mortality,” Ilan Schwartz, MD, PHD, an infectious disease physician at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, who researches emerging fungal infections, said in an interview. He was not involved with the research.

While larger studies looking at similar questions have been published, the new report has longer patient follow-up and is “better positioned to be able to estimate the mortality rate,” Dr. Schwartz noted. Even with 30 days of follow-up, “patients can have ongoing problems for many months, and so it’s possible that the true mortality rate is even higher, once you get beyond that period,” he added.

But Santosh G. Honavar, MD, the director of medical services at the Centre for Sight Eye Hospital in Hyderabad, India, also unaffiliated with the study, noted that the subset of patients included in the latest report may have had much more severe infection – and subsequently higher mortality rates – than a more generalized study in a broader patient population.

For example, a study by Mrittika Sen, PhD, Dr. Honavar, and their coauthors, published in the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology earlier this year, found a mortality rate of 14% when they examined the records of more than 2,800 patients across 102 treatment centers.

Taking that into account, “we believe that the actual mortality may be somewhere between the 14% reported by Sen et al. from the large Indian series and the 53% that we report at 3 weeks,” the JAMA Ophthalmology authors wrote.

Dr. Honavar also noted that the new report of severe infection outcomes identifies subgroups at higher risk of death due to CAM: those with severe COVID-19 infection or orbital disease. These groups “would need higher surveillance for mucormycosis, thus enabling early diagnosis and prompt initiation of amphotericin B upon diagnosis of mucormycosis,” he said in an interview. “These measures can possibly minimize the risk of death.”

Ongoing research on CAM cases will continue to inform knowledge and treatment of the disease, but there are still unanswered questions. “We still have a fairly unsatisfactory understanding of exactly why this [CAM] epidemic occurred and why it was so bad,” Dr. Schwartz noted. And while mucormycosis cases have seemed to drop off since the surge earlier this year, “I don’t think we’re out of the woods,” he added. “There’s a lot more awareness in India and around the world about this disease now, but we’re still quite vulnerable to seeing it again.”

Dr. Honavar is the editor-in-chief of the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. Dr. Schwartz reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Earlier this year, hospitals in India were dealing not only with the coronavirus pandemic but also with a surge in a potentially lethal fungal infection in patients previously treated for COVID-19. Mucormycosis, also known as black fungus, is typically a rare infection, but India had recorded more than 45,000 cases as of July 2021.

Now, a recent report suggests that patients with COVID-19–associated rhino-orbital cerebral mucormycosis (CAM) may have a higher mortality rate than previously estimated. The study was published Dec. 9 in JAMA Ophthalmology.

“The mortality indicators we observed, such as assisted ventilation and presence of severe orbital manifestations, can help physicians triage patients for emergency procedures, such as functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS), and administer systemic antifungal agents when in short supply,” the study authors wrote.

Mucormycosis usually infects immunocompromised patients. Previous research has found that poorly controlled diabetes – an epidemic in India – and use of high-dose systemic corticosteroids are two main risk factors for developing CAM. Even before COVID-19, India had a high incidence of mucormycosis compared to other countries, but cases exist around the world. In fact, on Dec. 17, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 10 isolated cases of COVID-19–associated mucormycosis identified in Arkansas hospitals between July and September 2021.

The disease can cause blurred vision, black lesions on the nose or inside of the mouth, and facial swelling. In rhino-orbital cerebral mucormycosis, extensive infection can necessitate orbital exenteration surgery, a disfiguring procedure that typically involves removal of the entire contents of the bony eye socket, as well as removal of the sinuses. Estimates for the mortality rate for this disease range from 14% to nearly 80%.

To better understand the cumulative morality rates for CAM and to identify additional risk factors, researchers reviewed the medical records of patients diagnosed and treated for CAM at a tertiary care multispecialty government hospital in Maharashtra, a state in the west-central region of India. The analysis included patients who died after admission or who had at minimum 30 days of documented follow-up. All diagnoses occurred between March 1 and May 30, 2021. All patients underwent comprehensive ophthalmic exams and routine blood workups.

Seventy-three patients were included in the study, with the average age of 53.5 years; 66% of the patients were male, and 74% of all patients had diabetes. Of the 47 individuals with available COVID-19 vaccination information, 89% had not had either shot of the vaccine, and 11% had the first dose. No patients in the cohort had received both doses of the vaccine; 87% of the patients were previously hospitalized for COVID-19, with 43 needing supplemental oxygen, 14 receiving noninvasive ventilation and ventilator support (NIV), and three requiring mechanical ventilation.

Patients developed CAM a median of 28 days after being discharged from the hospital for COVID-19 treatment; 26 patients died, 18 patients underwent FESS, and five underwent orbital exenteration. While 36% of patients died overall, the researchers found the cumulative probability of death from CAM rose from 26% at day 7 to 53% at day 21. They also found that the patients who died had more severe COVID-19, indicated by more days spent on supplemental oxygen (P = .003) and increased need for NIV or mechanical ventilation (P = .02) compared to patients who survived CAM. Those who died also had poorer visual acuity, with 35% of the group having no light perception during examination compared to 6% of surviving CAM patients (P = .02).

These findings are largely “confirmatory to what we previously knew, which is that [CAM] is a very bad disease with high morbidity and high mortality,” Ilan Schwartz, MD, PHD, an infectious disease physician at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, who researches emerging fungal infections, said in an interview. He was not involved with the research.

While larger studies looking at similar questions have been published, the new report has longer patient follow-up and is “better positioned to be able to estimate the mortality rate,” Dr. Schwartz noted. Even with 30 days of follow-up, “patients can have ongoing problems for many months, and so it’s possible that the true mortality rate is even higher, once you get beyond that period,” he added.

But Santosh G. Honavar, MD, the director of medical services at the Centre for Sight Eye Hospital in Hyderabad, India, also unaffiliated with the study, noted that the subset of patients included in the latest report may have had much more severe infection – and subsequently higher mortality rates – than a more generalized study in a broader patient population.

For example, a study by Mrittika Sen, PhD, Dr. Honavar, and their coauthors, published in the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology earlier this year, found a mortality rate of 14% when they examined the records of more than 2,800 patients across 102 treatment centers.

Taking that into account, “we believe that the actual mortality may be somewhere between the 14% reported by Sen et al. from the large Indian series and the 53% that we report at 3 weeks,” the JAMA Ophthalmology authors wrote.

Dr. Honavar also noted that the new report of severe infection outcomes identifies subgroups at higher risk of death due to CAM: those with severe COVID-19 infection or orbital disease. These groups “would need higher surveillance for mucormycosis, thus enabling early diagnosis and prompt initiation of amphotericin B upon diagnosis of mucormycosis,” he said in an interview. “These measures can possibly minimize the risk of death.”

Ongoing research on CAM cases will continue to inform knowledge and treatment of the disease, but there are still unanswered questions. “We still have a fairly unsatisfactory understanding of exactly why this [CAM] epidemic occurred and why it was so bad,” Dr. Schwartz noted. And while mucormycosis cases have seemed to drop off since the surge earlier this year, “I don’t think we’re out of the woods,” he added. “There’s a lot more awareness in India and around the world about this disease now, but we’re still quite vulnerable to seeing it again.”

Dr. Honavar is the editor-in-chief of the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. Dr. Schwartz reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Earlier this year, hospitals in India were dealing not only with the coronavirus pandemic but also with a surge in a potentially lethal fungal infection in patients previously treated for COVID-19. Mucormycosis, also known as black fungus, is typically a rare infection, but India had recorded more than 45,000 cases as of July 2021.

Now, a recent report suggests that patients with COVID-19–associated rhino-orbital cerebral mucormycosis (CAM) may have a higher mortality rate than previously estimated. The study was published Dec. 9 in JAMA Ophthalmology.

“The mortality indicators we observed, such as assisted ventilation and presence of severe orbital manifestations, can help physicians triage patients for emergency procedures, such as functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS), and administer systemic antifungal agents when in short supply,” the study authors wrote.

Mucormycosis usually infects immunocompromised patients. Previous research has found that poorly controlled diabetes – an epidemic in India – and use of high-dose systemic corticosteroids are two main risk factors for developing CAM. Even before COVID-19, India had a high incidence of mucormycosis compared to other countries, but cases exist around the world. In fact, on Dec. 17, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 10 isolated cases of COVID-19–associated mucormycosis identified in Arkansas hospitals between July and September 2021.

The disease can cause blurred vision, black lesions on the nose or inside of the mouth, and facial swelling. In rhino-orbital cerebral mucormycosis, extensive infection can necessitate orbital exenteration surgery, a disfiguring procedure that typically involves removal of the entire contents of the bony eye socket, as well as removal of the sinuses. Estimates for the mortality rate for this disease range from 14% to nearly 80%.

To better understand the cumulative morality rates for CAM and to identify additional risk factors, researchers reviewed the medical records of patients diagnosed and treated for CAM at a tertiary care multispecialty government hospital in Maharashtra, a state in the west-central region of India. The analysis included patients who died after admission or who had at minimum 30 days of documented follow-up. All diagnoses occurred between March 1 and May 30, 2021. All patients underwent comprehensive ophthalmic exams and routine blood workups.

Seventy-three patients were included in the study, with the average age of 53.5 years; 66% of the patients were male, and 74% of all patients had diabetes. Of the 47 individuals with available COVID-19 vaccination information, 89% had not had either shot of the vaccine, and 11% had the first dose. No patients in the cohort had received both doses of the vaccine; 87% of the patients were previously hospitalized for COVID-19, with 43 needing supplemental oxygen, 14 receiving noninvasive ventilation and ventilator support (NIV), and three requiring mechanical ventilation.

Patients developed CAM a median of 28 days after being discharged from the hospital for COVID-19 treatment; 26 patients died, 18 patients underwent FESS, and five underwent orbital exenteration. While 36% of patients died overall, the researchers found the cumulative probability of death from CAM rose from 26% at day 7 to 53% at day 21. They also found that the patients who died had more severe COVID-19, indicated by more days spent on supplemental oxygen (P = .003) and increased need for NIV or mechanical ventilation (P = .02) compared to patients who survived CAM. Those who died also had poorer visual acuity, with 35% of the group having no light perception during examination compared to 6% of surviving CAM patients (P = .02).

These findings are largely “confirmatory to what we previously knew, which is that [CAM] is a very bad disease with high morbidity and high mortality,” Ilan Schwartz, MD, PHD, an infectious disease physician at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, who researches emerging fungal infections, said in an interview. He was not involved with the research.

While larger studies looking at similar questions have been published, the new report has longer patient follow-up and is “better positioned to be able to estimate the mortality rate,” Dr. Schwartz noted. Even with 30 days of follow-up, “patients can have ongoing problems for many months, and so it’s possible that the true mortality rate is even higher, once you get beyond that period,” he added.

But Santosh G. Honavar, MD, the director of medical services at the Centre for Sight Eye Hospital in Hyderabad, India, also unaffiliated with the study, noted that the subset of patients included in the latest report may have had much more severe infection – and subsequently higher mortality rates – than a more generalized study in a broader patient population.

For example, a study by Mrittika Sen, PhD, Dr. Honavar, and their coauthors, published in the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology earlier this year, found a mortality rate of 14% when they examined the records of more than 2,800 patients across 102 treatment centers.

Taking that into account, “we believe that the actual mortality may be somewhere between the 14% reported by Sen et al. from the large Indian series and the 53% that we report at 3 weeks,” the JAMA Ophthalmology authors wrote.

Dr. Honavar also noted that the new report of severe infection outcomes identifies subgroups at higher risk of death due to CAM: those with severe COVID-19 infection or orbital disease. These groups “would need higher surveillance for mucormycosis, thus enabling early diagnosis and prompt initiation of amphotericin B upon diagnosis of mucormycosis,” he said in an interview. “These measures can possibly minimize the risk of death.”

Ongoing research on CAM cases will continue to inform knowledge and treatment of the disease, but there are still unanswered questions. “We still have a fairly unsatisfactory understanding of exactly why this [CAM] epidemic occurred and why it was so bad,” Dr. Schwartz noted. And while mucormycosis cases have seemed to drop off since the surge earlier this year, “I don’t think we’re out of the woods,” he added. “There’s a lot more awareness in India and around the world about this disease now, but we’re still quite vulnerable to seeing it again.”

Dr. Honavar is the editor-in-chief of the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. Dr. Schwartz reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA OPHTHALMOLOGY

Does atopic dermatitis pose an increased risk of acquiring COVID-19?

According to the best available evidence, patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) do not appear to face an increased risk of acquiring COVID-19 or becoming hospitalized because of the virus.

“This is an area that will continue to evolve, and further understanding will improve the health care advice that we provide to our patients,” Jacob P. Thyssen, MD, PhD, DmSci, said at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium. “The general recommendation for now is to continue systemic AD treatments during the pandemic, but the risk of acquiring COVID-19 is different for different drugs.”

According to Thyssen, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, early management guidance from the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis (ETFAD), the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), and the International Eczema Council (IEC) state that patients with AD who are on biologics or immunosuppressants should continue treatment if they are not infected with COVID-19. For example, the EIC statement says that the IEC “does not recommend temporary interruption of systemic AD treatments affecting the immune system in patients without COVID-19 infection or in those who have COVID-19 but are asymptomatic or have only mild symptoms.”

Guidelines from the EAACI recommend that patients with AD who become infected with COVID-19 withhold biologic treatment for a minimum of 2 weeks until they have recovered and/or have a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

“However, if you have more severe respiratory disease, the advice to dermatologists is to consult with an infectious medicine specialist or a pulmonologist,” Dr. Thyssen said. “That’s out of our specialty realm. But in terms of AD, there’s no reason to stop treatment as long as the patient has mild symptoms or is asymptomatic. AD patients treated with immunosuppressive agents may have a higher risk of COVID-19 complications. Treatment with traditional immunosuppressant medications does increase the risk of infections. But what about COVID-19?”

Traditional systemic immunosuppressive therapies in AD with azathioprine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate suppress the immune system for 1-3 months, Dr. Thyssen continued. “We do know that vaccination response is reduced when using these agents,” he said. “The half-life of dupilumab [Dupixent] is 12-21 days. It takes about 13 weeks before dupilumab is completely out of the system, but it’s such a targeted therapy that it doesn’t lead to any broad immunosuppression.”

Meanwhile, the half-life of JAK inhibitors such as baricitinib (Olumiant) is about 13 hours. “It’s a broader immune suppressant because there will be off-target effects if you have a high dose, but it’s much more specific than the traditional immunosuppressants,” he said. “We now have JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors in AD, which do not interfere with vaccine responses to the same degree as traditional immunosuppressants.”

To evaluate the risk for COVID-19 in patients with AD, researchers from the Center for Dermatology Research at the University of Manchester, United Kingdom, performed a cross-sectional study of 13,162 dermatology patients seen in the U.K. between June 2018 and Feb. 2021. Of the 13,162 patients, 624 (4.7%) had AD. They found that 4.8% of patients without a history of COVID-19 infection had AD, compared with 3.4% with a history of COVID-19. The risk for COVID-19 in patients with AD was similar to that of controls (adjusted odds ratio, 0.67).

Authors of a separate cross-sectional study published in May evaluated the health insurance medical records of 269,299 patients who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 across University of California Medical Centers. Of these, 3.6% had a positive test for SARS-CoV-2. Of 5,387 patients with AD, the infection rate was 2.9%, which was lower than in those without AD (3.7%; P = .0063). Hospitalization and mortality were not increased in patients with AD.

Another study, a case-control of more than 4.6 million HMO patients in Israel, found that the intake of systemic corticosteroids, older age, comorbid cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, and COPD were independent predictors of COVID-19–associated hospitalization. Mortality as a result of COVID-19 was independently predicted by metabolic syndrome and COPD but not by any AD-related variables.

“So, for our AD patients out there, there is no need to fear that they develop a COVID-19 infection or have a severe course, but we do have a few medications that would slightly increase the risk,” Dr. Thyssen said.

In another analysis, researchers evaluated Symphony Health–derived data from the COVID-19 Research Database to evaluate the risk for COVID-19 infection in adults with AD. The AD cohort included 39,417 patients, and the cohort without AD included 397,293 patients. Among AD patients, 8,180 were prescribed prednisone, 2,793 were prescribed dupilumab, 714 were prescribed methotrexate, and 512 were prescribed cyclosporine. The risk for COVID-19 was slightly increased in the AD cohort compared with the non-AD cohort (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.18; P < .0001).

“There can be various explanations for this,” Dr. Thyssen said. “I still think we should maintain that AD itself is not a risk factor for COVID-19, but some of the medications may slightly increase the risk.”

In other findings, the investigators observed that treatment with dupilumab versus no systemic medication decreased the risk for COVID-19 by 34% (adjusted IRR, 0.66; P < .0001), as did methotrexate by 18% (adjusted IRR 0.82; P = .32). However, compared with no systemic medication, the use of prednisone slightly increased the risk of COVID-19 (adjusted IRR, 1.13; P = .03), as did the use of cyclosporine (adjusted IRR, 1.20; P = .32) and azathioprine (adjusted IRR, 1.61; P = .16).

More recently, researchers evaluated the records of 1,237 patients with moderate-to-severe AD (aged 9-95 years) to assess the self-reported severity of COVID-19 symptoms among those who received dupilumab versus other treatments.

Of the 1,237 patients with AD, 632 were on dupilumab, 107 were on other systemic treatments, and 498 were on limited or no treatment. Patients treated with dupilumab were less likely to report moderate-to-severe COVID-19 symptoms compared with patients who were on other systemic treatments, or limited/no treatments.

Vaccines and AD

Dr. Thyssen pointed out that the risk-benefit ratio of currently approved COVID-19 vaccines is better than the risk for an infection with SARS-CoV-2. “AD is not a contraindication to vaccination,” he said. “COVID-19 vaccine does not cause AD worsening since the vaccination response is mainly Th1 skewed.” He added that systemic immunosuppressants and JAK inhibitors used to treat AD may attenuate the vaccination response, but no attenuation is expected with dupilumab. “The half-life of JAK inhibitors is so short that vaccination followed by 1 week of pause treatment is a good strategy for patients.”

Dr. Thyssen disclosed that he is a speaker, advisory board member, and/or investigator for Asian, Arena, Almirall, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi-Genzyme.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

According to the best available evidence, patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) do not appear to face an increased risk of acquiring COVID-19 or becoming hospitalized because of the virus.

“This is an area that will continue to evolve, and further understanding will improve the health care advice that we provide to our patients,” Jacob P. Thyssen, MD, PhD, DmSci, said at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium. “The general recommendation for now is to continue systemic AD treatments during the pandemic, but the risk of acquiring COVID-19 is different for different drugs.”

According to Thyssen, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, early management guidance from the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis (ETFAD), the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), and the International Eczema Council (IEC) state that patients with AD who are on biologics or immunosuppressants should continue treatment if they are not infected with COVID-19. For example, the EIC statement says that the IEC “does not recommend temporary interruption of systemic AD treatments affecting the immune system in patients without COVID-19 infection or in those who have COVID-19 but are asymptomatic or have only mild symptoms.”

Guidelines from the EAACI recommend that patients with AD who become infected with COVID-19 withhold biologic treatment for a minimum of 2 weeks until they have recovered and/or have a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

“However, if you have more severe respiratory disease, the advice to dermatologists is to consult with an infectious medicine specialist or a pulmonologist,” Dr. Thyssen said. “That’s out of our specialty realm. But in terms of AD, there’s no reason to stop treatment as long as the patient has mild symptoms or is asymptomatic. AD patients treated with immunosuppressive agents may have a higher risk of COVID-19 complications. Treatment with traditional immunosuppressant medications does increase the risk of infections. But what about COVID-19?”

Traditional systemic immunosuppressive therapies in AD with azathioprine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate suppress the immune system for 1-3 months, Dr. Thyssen continued. “We do know that vaccination response is reduced when using these agents,” he said. “The half-life of dupilumab [Dupixent] is 12-21 days. It takes about 13 weeks before dupilumab is completely out of the system, but it’s such a targeted therapy that it doesn’t lead to any broad immunosuppression.”

Meanwhile, the half-life of JAK inhibitors such as baricitinib (Olumiant) is about 13 hours. “It’s a broader immune suppressant because there will be off-target effects if you have a high dose, but it’s much more specific than the traditional immunosuppressants,” he said. “We now have JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors in AD, which do not interfere with vaccine responses to the same degree as traditional immunosuppressants.”

To evaluate the risk for COVID-19 in patients with AD, researchers from the Center for Dermatology Research at the University of Manchester, United Kingdom, performed a cross-sectional study of 13,162 dermatology patients seen in the U.K. between June 2018 and Feb. 2021. Of the 13,162 patients, 624 (4.7%) had AD. They found that 4.8% of patients without a history of COVID-19 infection had AD, compared with 3.4% with a history of COVID-19. The risk for COVID-19 in patients with AD was similar to that of controls (adjusted odds ratio, 0.67).

Authors of a separate cross-sectional study published in May evaluated the health insurance medical records of 269,299 patients who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 across University of California Medical Centers. Of these, 3.6% had a positive test for SARS-CoV-2. Of 5,387 patients with AD, the infection rate was 2.9%, which was lower than in those without AD (3.7%; P = .0063). Hospitalization and mortality were not increased in patients with AD.

Another study, a case-control of more than 4.6 million HMO patients in Israel, found that the intake of systemic corticosteroids, older age, comorbid cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, and COPD were independent predictors of COVID-19–associated hospitalization. Mortality as a result of COVID-19 was independently predicted by metabolic syndrome and COPD but not by any AD-related variables.

“So, for our AD patients out there, there is no need to fear that they develop a COVID-19 infection or have a severe course, but we do have a few medications that would slightly increase the risk,” Dr. Thyssen said.

In another analysis, researchers evaluated Symphony Health–derived data from the COVID-19 Research Database to evaluate the risk for COVID-19 infection in adults with AD. The AD cohort included 39,417 patients, and the cohort without AD included 397,293 patients. Among AD patients, 8,180 were prescribed prednisone, 2,793 were prescribed dupilumab, 714 were prescribed methotrexate, and 512 were prescribed cyclosporine. The risk for COVID-19 was slightly increased in the AD cohort compared with the non-AD cohort (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.18; P < .0001).

“There can be various explanations for this,” Dr. Thyssen said. “I still think we should maintain that AD itself is not a risk factor for COVID-19, but some of the medications may slightly increase the risk.”

In other findings, the investigators observed that treatment with dupilumab versus no systemic medication decreased the risk for COVID-19 by 34% (adjusted IRR, 0.66; P < .0001), as did methotrexate by 18% (adjusted IRR 0.82; P = .32). However, compared with no systemic medication, the use of prednisone slightly increased the risk of COVID-19 (adjusted IRR, 1.13; P = .03), as did the use of cyclosporine (adjusted IRR, 1.20; P = .32) and azathioprine (adjusted IRR, 1.61; P = .16).

More recently, researchers evaluated the records of 1,237 patients with moderate-to-severe AD (aged 9-95 years) to assess the self-reported severity of COVID-19 symptoms among those who received dupilumab versus other treatments.

Of the 1,237 patients with AD, 632 were on dupilumab, 107 were on other systemic treatments, and 498 were on limited or no treatment. Patients treated with dupilumab were less likely to report moderate-to-severe COVID-19 symptoms compared with patients who were on other systemic treatments, or limited/no treatments.

Vaccines and AD

Dr. Thyssen pointed out that the risk-benefit ratio of currently approved COVID-19 vaccines is better than the risk for an infection with SARS-CoV-2. “AD is not a contraindication to vaccination,” he said. “COVID-19 vaccine does not cause AD worsening since the vaccination response is mainly Th1 skewed.” He added that systemic immunosuppressants and JAK inhibitors used to treat AD may attenuate the vaccination response, but no attenuation is expected with dupilumab. “The half-life of JAK inhibitors is so short that vaccination followed by 1 week of pause treatment is a good strategy for patients.”

Dr. Thyssen disclosed that he is a speaker, advisory board member, and/or investigator for Asian, Arena, Almirall, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi-Genzyme.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

According to the best available evidence, patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) do not appear to face an increased risk of acquiring COVID-19 or becoming hospitalized because of the virus.

“This is an area that will continue to evolve, and further understanding will improve the health care advice that we provide to our patients,” Jacob P. Thyssen, MD, PhD, DmSci, said at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium. “The general recommendation for now is to continue systemic AD treatments during the pandemic, but the risk of acquiring COVID-19 is different for different drugs.”

According to Thyssen, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, early management guidance from the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis (ETFAD), the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), and the International Eczema Council (IEC) state that patients with AD who are on biologics or immunosuppressants should continue treatment if they are not infected with COVID-19. For example, the EIC statement says that the IEC “does not recommend temporary interruption of systemic AD treatments affecting the immune system in patients without COVID-19 infection or in those who have COVID-19 but are asymptomatic or have only mild symptoms.”

Guidelines from the EAACI recommend that patients with AD who become infected with COVID-19 withhold biologic treatment for a minimum of 2 weeks until they have recovered and/or have a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

“However, if you have more severe respiratory disease, the advice to dermatologists is to consult with an infectious medicine specialist or a pulmonologist,” Dr. Thyssen said. “That’s out of our specialty realm. But in terms of AD, there’s no reason to stop treatment as long as the patient has mild symptoms or is asymptomatic. AD patients treated with immunosuppressive agents may have a higher risk of COVID-19 complications. Treatment with traditional immunosuppressant medications does increase the risk of infections. But what about COVID-19?”

Traditional systemic immunosuppressive therapies in AD with azathioprine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate suppress the immune system for 1-3 months, Dr. Thyssen continued. “We do know that vaccination response is reduced when using these agents,” he said. “The half-life of dupilumab [Dupixent] is 12-21 days. It takes about 13 weeks before dupilumab is completely out of the system, but it’s such a targeted therapy that it doesn’t lead to any broad immunosuppression.”

Meanwhile, the half-life of JAK inhibitors such as baricitinib (Olumiant) is about 13 hours. “It’s a broader immune suppressant because there will be off-target effects if you have a high dose, but it’s much more specific than the traditional immunosuppressants,” he said. “We now have JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors in AD, which do not interfere with vaccine responses to the same degree as traditional immunosuppressants.”

To evaluate the risk for COVID-19 in patients with AD, researchers from the Center for Dermatology Research at the University of Manchester, United Kingdom, performed a cross-sectional study of 13,162 dermatology patients seen in the U.K. between June 2018 and Feb. 2021. Of the 13,162 patients, 624 (4.7%) had AD. They found that 4.8% of patients without a history of COVID-19 infection had AD, compared with 3.4% with a history of COVID-19. The risk for COVID-19 in patients with AD was similar to that of controls (adjusted odds ratio, 0.67).

Authors of a separate cross-sectional study published in May evaluated the health insurance medical records of 269,299 patients who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 across University of California Medical Centers. Of these, 3.6% had a positive test for SARS-CoV-2. Of 5,387 patients with AD, the infection rate was 2.9%, which was lower than in those without AD (3.7%; P = .0063). Hospitalization and mortality were not increased in patients with AD.

Another study, a case-control of more than 4.6 million HMO patients in Israel, found that the intake of systemic corticosteroids, older age, comorbid cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, and COPD were independent predictors of COVID-19–associated hospitalization. Mortality as a result of COVID-19 was independently predicted by metabolic syndrome and COPD but not by any AD-related variables.

“So, for our AD patients out there, there is no need to fear that they develop a COVID-19 infection or have a severe course, but we do have a few medications that would slightly increase the risk,” Dr. Thyssen said.

In another analysis, researchers evaluated Symphony Health–derived data from the COVID-19 Research Database to evaluate the risk for COVID-19 infection in adults with AD. The AD cohort included 39,417 patients, and the cohort without AD included 397,293 patients. Among AD patients, 8,180 were prescribed prednisone, 2,793 were prescribed dupilumab, 714 were prescribed methotrexate, and 512 were prescribed cyclosporine. The risk for COVID-19 was slightly increased in the AD cohort compared with the non-AD cohort (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.18; P < .0001).

“There can be various explanations for this,” Dr. Thyssen said. “I still think we should maintain that AD itself is not a risk factor for COVID-19, but some of the medications may slightly increase the risk.”

In other findings, the investigators observed that treatment with dupilumab versus no systemic medication decreased the risk for COVID-19 by 34% (adjusted IRR, 0.66; P < .0001), as did methotrexate by 18% (adjusted IRR 0.82; P = .32). However, compared with no systemic medication, the use of prednisone slightly increased the risk of COVID-19 (adjusted IRR, 1.13; P = .03), as did the use of cyclosporine (adjusted IRR, 1.20; P = .32) and azathioprine (adjusted IRR, 1.61; P = .16).

More recently, researchers evaluated the records of 1,237 patients with moderate-to-severe AD (aged 9-95 years) to assess the self-reported severity of COVID-19 symptoms among those who received dupilumab versus other treatments.

Of the 1,237 patients with AD, 632 were on dupilumab, 107 were on other systemic treatments, and 498 were on limited or no treatment. Patients treated with dupilumab were less likely to report moderate-to-severe COVID-19 symptoms compared with patients who were on other systemic treatments, or limited/no treatments.

Vaccines and AD

Dr. Thyssen pointed out that the risk-benefit ratio of currently approved COVID-19 vaccines is better than the risk for an infection with SARS-CoV-2. “AD is not a contraindication to vaccination,” he said. “COVID-19 vaccine does not cause AD worsening since the vaccination response is mainly Th1 skewed.” He added that systemic immunosuppressants and JAK inhibitors used to treat AD may attenuate the vaccination response, but no attenuation is expected with dupilumab. “The half-life of JAK inhibitors is so short that vaccination followed by 1 week of pause treatment is a good strategy for patients.”

Dr. Thyssen disclosed that he is a speaker, advisory board member, and/or investigator for Asian, Arena, Almirall, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi-Genzyme.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM REVOLUTIONIZING AD 2021

COVID-19 vaccinations in people with HIV reflect general rates despite higher mortality risk, study says

Around the world, people with HIV show variations in COVID-19 vaccination rates similar to those seen in the general population, raising concerns because of their increased risk for morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 infection.

“To our knowledge, this analysis presents the first and largest investigation of vaccination rates among people with HIV,” reported the authors in research published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

The findings reflect data on nearly 7,000 people with HIV participating in the REPRIEVE clinical trial. As of July, COVID-19 vaccination rates ranged from a high of 71% in higher income regions to just 18% in sub-Saharan Africa and bottomed out at 0% in Haiti.

“This disparity in COVID-19 vaccination rates among people with HIV across income regions may increase morbidity from COVID-19 in the most vulnerable HIV populations,” the authors noted.

In general, people with HIV have been shown in recent research to have as much as 29% higher odds of morality from COVID-19 than the general population, and a 20% higher odds of hospitalization, hence their need for vaccination is especially pressing.

To understand the vaccination rates, the authors looked at data from the ongoing REPRIEVE trial, designed to investigate primary cardiovascular prevention worldwide among people with HIV. The trial includes data on COVID-19 vaccination status, providing a unique opportunity to capture those rates.

The study specifically included 6,952 people with HIV aged 40-75 years and on stable antiretroviral therapy (ART), without known cardiovascular disease, and a low to moderate atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

The diverse participants with HIV were from 12 countries, including 66% who were people of color, as well as 32% women. Countries represented include Brazil (n = 1,042), Botswana (n = 273), Canada (n = 123), Haiti (n = 136), India (n = 469), Peru (n = 142), South Africa (n = 527), Spain (n = 198), Thailand (n = 582), Uganda (n = 175), United States (n = 3,162), and Zimbabwe (n = 123).

With vaccination defined as having received at least one vaccine shot, the overall cumulative COVID-19 vaccination rate in the study was 55% through July 2021.

By region, the highest cumulative rates were in the high-income countries of the United States and Canada (71%), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (59%) – all consistent with the general population in these areas

Lower cumulative vaccination rates were observed in South Asia (49%), Southeast/East Asia (41%), and sub-Saharan Africa (18%), also reflecting the regional vaccination rates.

The United States had the highest country-specific COVID-19 vaccination rate of 72%, followed by Peru (69%) and Brazil (63%). Countries with the lowest vaccination rates were South Africa (18%), Uganda (3%), and Haiti (0%).

Of note, South Africa and Botswana have the largest share of deaths from HIV/AIDS, and both had very low COVID-19 vaccination rates in general, compared with high-income countries.

Overall, factors linked to the likelihood of being vaccinated included residing in the high-income U.S./Canada Global Burden of Disease superregion, as well as being White, male, older, having a higher body mass index (BMI), a higher ASCVD risk score, and longer duration of ART.

Participants’ decisions regarding COVID-19 vaccination in the study were made individually and were not based on any study-related recommendations or requirements, the authors noted.

Vaccination rates were higher among men than women in most regions, with the exception of sub-Saharan Africa. Vaccination rates were higher among Whites than Blacks in the U.S./Canada high-income region, with a high proportion of participants from the United States.

“It was surprising to us – and unfortunate – that in the high-income superregion vaccination rates were higher among individuals who identified as White than those who identified as Black and among men,” senior author Steven K. Grinspoon, MD, said in an interview.

“Given data for higher morbidity from COVID-19 among people of color with HIV, this disparity is likely to have significant public health implications,” said Dr. Grinspoon, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and chief of the metabolism unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

Newer data from the REPRIEVE study through October has shown continued steady increases in the cumulative vaccination rates in all regions, Dr. Grinspoon noted, with the largest increases in the Southeast/East Asia, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, whereas a leveling off of rates was observed in the high-income regions.

Overall, “it is encouraging that rates among people with HIV are similar to and, in many regions, higher than the general population,” Dr. Grinspoon said.

However, with the data showing a higher risk for COVID-19 death in people with HIV, “it is critical that people with HIV, representing a vulnerable and immunocompromised population, be vaccinated for COVID-19,” Dr. Grinspoon said.

Commenting on the study, Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, director of the Gladstone Center for AIDS Research at the University of California, San Francisco, agreed that “it is encouraging that these rates are as high as the general population, showing that there is not excess hesitancy among those living with HIV.”

Unlike other immunocompromised groups, people with HIV were not necessarily prioritized for vaccination, since antiretroviral therapy can reconstitute the immune system, “so I am not surprised the [vaccination] rates aren’t higher,” Dr. Gandhi, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview.

Nevertheless, “it is important that those with risk factors for more severe disease, such as higher BMI and higher cardiovascular disease, are prioritized for COVID-19 vaccination, [as] these are important groups in which to increase rates,” she said.

“The take-home message is that we have to increase our rates of vaccination in this critically important population,” Dr. Gandhi emphasized. “Global vaccine equity is paramount given that the burden of HIV infections remains in sub-Saharan Africa.”

The study received support from the National Institutes of Health and funding from Kowa Pharmaceuticals and Gilead Sciences. The authors and Dr. Gandhi disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Around the world, people with HIV show variations in COVID-19 vaccination rates similar to those seen in the general population, raising concerns because of their increased risk for morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 infection.

“To our knowledge, this analysis presents the first and largest investigation of vaccination rates among people with HIV,” reported the authors in research published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

The findings reflect data on nearly 7,000 people with HIV participating in the REPRIEVE clinical trial. As of July, COVID-19 vaccination rates ranged from a high of 71% in higher income regions to just 18% in sub-Saharan Africa and bottomed out at 0% in Haiti.

“This disparity in COVID-19 vaccination rates among people with HIV across income regions may increase morbidity from COVID-19 in the most vulnerable HIV populations,” the authors noted.

In general, people with HIV have been shown in recent research to have as much as 29% higher odds of morality from COVID-19 than the general population, and a 20% higher odds of hospitalization, hence their need for vaccination is especially pressing.

To understand the vaccination rates, the authors looked at data from the ongoing REPRIEVE trial, designed to investigate primary cardiovascular prevention worldwide among people with HIV. The trial includes data on COVID-19 vaccination status, providing a unique opportunity to capture those rates.

The study specifically included 6,952 people with HIV aged 40-75 years and on stable antiretroviral therapy (ART), without known cardiovascular disease, and a low to moderate atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

The diverse participants with HIV were from 12 countries, including 66% who were people of color, as well as 32% women. Countries represented include Brazil (n = 1,042), Botswana (n = 273), Canada (n = 123), Haiti (n = 136), India (n = 469), Peru (n = 142), South Africa (n = 527), Spain (n = 198), Thailand (n = 582), Uganda (n = 175), United States (n = 3,162), and Zimbabwe (n = 123).

With vaccination defined as having received at least one vaccine shot, the overall cumulative COVID-19 vaccination rate in the study was 55% through July 2021.

By region, the highest cumulative rates were in the high-income countries of the United States and Canada (71%), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (59%) – all consistent with the general population in these areas

Lower cumulative vaccination rates were observed in South Asia (49%), Southeast/East Asia (41%), and sub-Saharan Africa (18%), also reflecting the regional vaccination rates.

The United States had the highest country-specific COVID-19 vaccination rate of 72%, followed by Peru (69%) and Brazil (63%). Countries with the lowest vaccination rates were South Africa (18%), Uganda (3%), and Haiti (0%).

Of note, South Africa and Botswana have the largest share of deaths from HIV/AIDS, and both had very low COVID-19 vaccination rates in general, compared with high-income countries.

Overall, factors linked to the likelihood of being vaccinated included residing in the high-income U.S./Canada Global Burden of Disease superregion, as well as being White, male, older, having a higher body mass index (BMI), a higher ASCVD risk score, and longer duration of ART.

Participants’ decisions regarding COVID-19 vaccination in the study were made individually and were not based on any study-related recommendations or requirements, the authors noted.

Vaccination rates were higher among men than women in most regions, with the exception of sub-Saharan Africa. Vaccination rates were higher among Whites than Blacks in the U.S./Canada high-income region, with a high proportion of participants from the United States.

“It was surprising to us – and unfortunate – that in the high-income superregion vaccination rates were higher among individuals who identified as White than those who identified as Black and among men,” senior author Steven K. Grinspoon, MD, said in an interview.

“Given data for higher morbidity from COVID-19 among people of color with HIV, this disparity is likely to have significant public health implications,” said Dr. Grinspoon, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and chief of the metabolism unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

Newer data from the REPRIEVE study through October has shown continued steady increases in the cumulative vaccination rates in all regions, Dr. Grinspoon noted, with the largest increases in the Southeast/East Asia, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, whereas a leveling off of rates was observed in the high-income regions.

Overall, “it is encouraging that rates among people with HIV are similar to and, in many regions, higher than the general population,” Dr. Grinspoon said.

However, with the data showing a higher risk for COVID-19 death in people with HIV, “it is critical that people with HIV, representing a vulnerable and immunocompromised population, be vaccinated for COVID-19,” Dr. Grinspoon said.

Commenting on the study, Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, director of the Gladstone Center for AIDS Research at the University of California, San Francisco, agreed that “it is encouraging that these rates are as high as the general population, showing that there is not excess hesitancy among those living with HIV.”

Unlike other immunocompromised groups, people with HIV were not necessarily prioritized for vaccination, since antiretroviral therapy can reconstitute the immune system, “so I am not surprised the [vaccination] rates aren’t higher,” Dr. Gandhi, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview.

Nevertheless, “it is important that those with risk factors for more severe disease, such as higher BMI and higher cardiovascular disease, are prioritized for COVID-19 vaccination, [as] these are important groups in which to increase rates,” she said.

“The take-home message is that we have to increase our rates of vaccination in this critically important population,” Dr. Gandhi emphasized. “Global vaccine equity is paramount given that the burden of HIV infections remains in sub-Saharan Africa.”

The study received support from the National Institutes of Health and funding from Kowa Pharmaceuticals and Gilead Sciences. The authors and Dr. Gandhi disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Around the world, people with HIV show variations in COVID-19 vaccination rates similar to those seen in the general population, raising concerns because of their increased risk for morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 infection.

“To our knowledge, this analysis presents the first and largest investigation of vaccination rates among people with HIV,” reported the authors in research published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

The findings reflect data on nearly 7,000 people with HIV participating in the REPRIEVE clinical trial. As of July, COVID-19 vaccination rates ranged from a high of 71% in higher income regions to just 18% in sub-Saharan Africa and bottomed out at 0% in Haiti.

“This disparity in COVID-19 vaccination rates among people with HIV across income regions may increase morbidity from COVID-19 in the most vulnerable HIV populations,” the authors noted.

In general, people with HIV have been shown in recent research to have as much as 29% higher odds of morality from COVID-19 than the general population, and a 20% higher odds of hospitalization, hence their need for vaccination is especially pressing.

To understand the vaccination rates, the authors looked at data from the ongoing REPRIEVE trial, designed to investigate primary cardiovascular prevention worldwide among people with HIV. The trial includes data on COVID-19 vaccination status, providing a unique opportunity to capture those rates.

The study specifically included 6,952 people with HIV aged 40-75 years and on stable antiretroviral therapy (ART), without known cardiovascular disease, and a low to moderate atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

The diverse participants with HIV were from 12 countries, including 66% who were people of color, as well as 32% women. Countries represented include Brazil (n = 1,042), Botswana (n = 273), Canada (n = 123), Haiti (n = 136), India (n = 469), Peru (n = 142), South Africa (n = 527), Spain (n = 198), Thailand (n = 582), Uganda (n = 175), United States (n = 3,162), and Zimbabwe (n = 123).

With vaccination defined as having received at least one vaccine shot, the overall cumulative COVID-19 vaccination rate in the study was 55% through July 2021.

By region, the highest cumulative rates were in the high-income countries of the United States and Canada (71%), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (59%) – all consistent with the general population in these areas

Lower cumulative vaccination rates were observed in South Asia (49%), Southeast/East Asia (41%), and sub-Saharan Africa (18%), also reflecting the regional vaccination rates.

The United States had the highest country-specific COVID-19 vaccination rate of 72%, followed by Peru (69%) and Brazil (63%). Countries with the lowest vaccination rates were South Africa (18%), Uganda (3%), and Haiti (0%).

Of note, South Africa and Botswana have the largest share of deaths from HIV/AIDS, and both had very low COVID-19 vaccination rates in general, compared with high-income countries.

Overall, factors linked to the likelihood of being vaccinated included residing in the high-income U.S./Canada Global Burden of Disease superregion, as well as being White, male, older, having a higher body mass index (BMI), a higher ASCVD risk score, and longer duration of ART.

Participants’ decisions regarding COVID-19 vaccination in the study were made individually and were not based on any study-related recommendations or requirements, the authors noted.

Vaccination rates were higher among men than women in most regions, with the exception of sub-Saharan Africa. Vaccination rates were higher among Whites than Blacks in the U.S./Canada high-income region, with a high proportion of participants from the United States.

“It was surprising to us – and unfortunate – that in the high-income superregion vaccination rates were higher among individuals who identified as White than those who identified as Black and among men,” senior author Steven K. Grinspoon, MD, said in an interview.

“Given data for higher morbidity from COVID-19 among people of color with HIV, this disparity is likely to have significant public health implications,” said Dr. Grinspoon, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and chief of the metabolism unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

Newer data from the REPRIEVE study through October has shown continued steady increases in the cumulative vaccination rates in all regions, Dr. Grinspoon noted, with the largest increases in the Southeast/East Asia, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, whereas a leveling off of rates was observed in the high-income regions.