User login

Monoclonal antibodies for COVID – Give IV infusion or an injection?

New research suggests that the casirivimab-imdevimab monoclonal antibody treatment for COVID-19 could have been delivered via injection instead of intravenously. There was no statistically significant difference in 28-day hospitalization or death in those treated intravenously and via subcutaneous injection.

The findings, published in JAMA Network Open, aren’t directly relevant at the moment, since the casirivimab-imdevimab treatment was abandoned when it failed to work during the Omicron outbreak. However, they point toward the importance of studying multiple routes of administration, said study lead author and pharmacist Erin K. McCreary, PharmD, of the University of Pittsburgh, in an interview.

“It would be beneficial for all future monoclonal antibodies for COVID-19 to be studied subcutaneously or intramuscularly, if possible, since that’s logistically easier than IV in the outpatient setting,” she said.

According to Dr. McCreary, an outpatient casirivimab-imdevimab treatment was used from 2020 to 2022 to treat higher-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19. The treatment was typically given intravenously as recommended by the federal government’s Emergency Use Authorization, she said. Clinical trials of the treatment, according to the study, allowed only IV administration.

“However, during the Delta surge, we were faced with so many patient referrals for treatment and staffing shortages that we couldn’t accommodate every patient unless we switched to [the] subcutaneous route,” Dr. McCreary said. This approach shortened appointment times by 30 minutes vs. infusion, she said.

There are many benefits to subcutaneous administration versus IV, Dr. McCreary said. “You don’t need to start an intravenous line, so you avoid the line kit and the nursing time needed for that. You draw up the drug directly into syringes and inject under the skin, so you avoid the need for a fluid bag to mix the drug in and run intravenously,” she said. “The appointment times are shorter, so you can accommodate more patients per day. Pharmacy interns can give subcutaneous injections, so you avoid the need for a nurse trained in placing intravenous lines.”

The researchers prospectively assigned 1,959 matched adults with mild to moderate COVID-19 to subcutaneous or intravenous treatment. Of 969 patients who received the subcutaneous treatment (mean age, 53.8; 56.4% women), the 28-day rate of hospitalization or death was 3.4%. Of 1,216 patients who received intravenous treatment (mean age, 54.3; 54.4% women), the rate was 1.7%. The difference was not statistically significant (P = .16).

Among 1,306 nontreated controls, 7.0% were hospitalized or died within 28 days (risk ratio = 0.48 vs. subcutaneous treatment group; 95% confidence interval, 0.30-0.80; P = .002).

“We did not find any patients where IV is a must,” Dr. McCreary said. “However, our study wasn’t powered to see a difference in certain subgroups.”

In an interview, University of Toronto internal medicine and pharmacology/toxicology physician Peter Wu, MD, said he agrees that the study has value because it emphasizes the importance of testing whether monoclonal antibodies can be administered in ways other than intravenously.

However, in the larger picture, he said, this may be irrelevant since it’s clear that anti-spike treatments are not holding up against COVID-19 variants.

No study funding is reported. Some study authors reported disclosures outside the submitted work. Dr. Wu has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research suggests that the casirivimab-imdevimab monoclonal antibody treatment for COVID-19 could have been delivered via injection instead of intravenously. There was no statistically significant difference in 28-day hospitalization or death in those treated intravenously and via subcutaneous injection.

The findings, published in JAMA Network Open, aren’t directly relevant at the moment, since the casirivimab-imdevimab treatment was abandoned when it failed to work during the Omicron outbreak. However, they point toward the importance of studying multiple routes of administration, said study lead author and pharmacist Erin K. McCreary, PharmD, of the University of Pittsburgh, in an interview.

“It would be beneficial for all future monoclonal antibodies for COVID-19 to be studied subcutaneously or intramuscularly, if possible, since that’s logistically easier than IV in the outpatient setting,” she said.

According to Dr. McCreary, an outpatient casirivimab-imdevimab treatment was used from 2020 to 2022 to treat higher-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19. The treatment was typically given intravenously as recommended by the federal government’s Emergency Use Authorization, she said. Clinical trials of the treatment, according to the study, allowed only IV administration.

“However, during the Delta surge, we were faced with so many patient referrals for treatment and staffing shortages that we couldn’t accommodate every patient unless we switched to [the] subcutaneous route,” Dr. McCreary said. This approach shortened appointment times by 30 minutes vs. infusion, she said.

There are many benefits to subcutaneous administration versus IV, Dr. McCreary said. “You don’t need to start an intravenous line, so you avoid the line kit and the nursing time needed for that. You draw up the drug directly into syringes and inject under the skin, so you avoid the need for a fluid bag to mix the drug in and run intravenously,” she said. “The appointment times are shorter, so you can accommodate more patients per day. Pharmacy interns can give subcutaneous injections, so you avoid the need for a nurse trained in placing intravenous lines.”

The researchers prospectively assigned 1,959 matched adults with mild to moderate COVID-19 to subcutaneous or intravenous treatment. Of 969 patients who received the subcutaneous treatment (mean age, 53.8; 56.4% women), the 28-day rate of hospitalization or death was 3.4%. Of 1,216 patients who received intravenous treatment (mean age, 54.3; 54.4% women), the rate was 1.7%. The difference was not statistically significant (P = .16).

Among 1,306 nontreated controls, 7.0% were hospitalized or died within 28 days (risk ratio = 0.48 vs. subcutaneous treatment group; 95% confidence interval, 0.30-0.80; P = .002).

“We did not find any patients where IV is a must,” Dr. McCreary said. “However, our study wasn’t powered to see a difference in certain subgroups.”

In an interview, University of Toronto internal medicine and pharmacology/toxicology physician Peter Wu, MD, said he agrees that the study has value because it emphasizes the importance of testing whether monoclonal antibodies can be administered in ways other than intravenously.

However, in the larger picture, he said, this may be irrelevant since it’s clear that anti-spike treatments are not holding up against COVID-19 variants.

No study funding is reported. Some study authors reported disclosures outside the submitted work. Dr. Wu has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research suggests that the casirivimab-imdevimab monoclonal antibody treatment for COVID-19 could have been delivered via injection instead of intravenously. There was no statistically significant difference in 28-day hospitalization or death in those treated intravenously and via subcutaneous injection.

The findings, published in JAMA Network Open, aren’t directly relevant at the moment, since the casirivimab-imdevimab treatment was abandoned when it failed to work during the Omicron outbreak. However, they point toward the importance of studying multiple routes of administration, said study lead author and pharmacist Erin K. McCreary, PharmD, of the University of Pittsburgh, in an interview.

“It would be beneficial for all future monoclonal antibodies for COVID-19 to be studied subcutaneously or intramuscularly, if possible, since that’s logistically easier than IV in the outpatient setting,” she said.

According to Dr. McCreary, an outpatient casirivimab-imdevimab treatment was used from 2020 to 2022 to treat higher-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19. The treatment was typically given intravenously as recommended by the federal government’s Emergency Use Authorization, she said. Clinical trials of the treatment, according to the study, allowed only IV administration.

“However, during the Delta surge, we were faced with so many patient referrals for treatment and staffing shortages that we couldn’t accommodate every patient unless we switched to [the] subcutaneous route,” Dr. McCreary said. This approach shortened appointment times by 30 minutes vs. infusion, she said.

There are many benefits to subcutaneous administration versus IV, Dr. McCreary said. “You don’t need to start an intravenous line, so you avoid the line kit and the nursing time needed for that. You draw up the drug directly into syringes and inject under the skin, so you avoid the need for a fluid bag to mix the drug in and run intravenously,” she said. “The appointment times are shorter, so you can accommodate more patients per day. Pharmacy interns can give subcutaneous injections, so you avoid the need for a nurse trained in placing intravenous lines.”

The researchers prospectively assigned 1,959 matched adults with mild to moderate COVID-19 to subcutaneous or intravenous treatment. Of 969 patients who received the subcutaneous treatment (mean age, 53.8; 56.4% women), the 28-day rate of hospitalization or death was 3.4%. Of 1,216 patients who received intravenous treatment (mean age, 54.3; 54.4% women), the rate was 1.7%. The difference was not statistically significant (P = .16).

Among 1,306 nontreated controls, 7.0% were hospitalized or died within 28 days (risk ratio = 0.48 vs. subcutaneous treatment group; 95% confidence interval, 0.30-0.80; P = .002).

“We did not find any patients where IV is a must,” Dr. McCreary said. “However, our study wasn’t powered to see a difference in certain subgroups.”

In an interview, University of Toronto internal medicine and pharmacology/toxicology physician Peter Wu, MD, said he agrees that the study has value because it emphasizes the importance of testing whether monoclonal antibodies can be administered in ways other than intravenously.

However, in the larger picture, he said, this may be irrelevant since it’s clear that anti-spike treatments are not holding up against COVID-19 variants.

No study funding is reported. Some study authors reported disclosures outside the submitted work. Dr. Wu has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Woman who faked medical degree practiced for 3 years

Who needs medical degrees anyway?

It’s no secret that doctors make a fair chunk of change. It’s a lucrative profession, but that big fat paycheck is siloed behind long, tough years of medical school and residency. It’s not an easy path doctors walk. Or at least, it’s not supposed to be. Anything’s easy if you’re willing to lie.

That brings us to Sonia, a 31-year-old woman from northern France with a bachelor’s degree in real estate management who wasn’t bringing in enough money for her three children, at least not to her satisfaction. Naturally, the only decision was to forge some diplomas from the University of Strasbourg, as well as a certificate from the French Order of Physicians. Sonia got hired as a general practitioner by using the identities of two doctors who shared her name. She had no experience, had no idea what she was doing, and was wearing a GPS tagging bracelet for an unrelated crime, so she was quickly caught and exposed in October 2021, after, um, 3 years of fake doctoring, according to France Live.

Not to be deterred by this temporary setback, Sonia proceeded to immediately find work as an ophthalmologist, a career that requires more than 10 years of training, continuing her fraudulent medical career until recently, when she was caught again and sentenced to 3 years in prison. She did make 70,000 euros a year as a fake doctor, which isn’t exactly huge money, but certainly not bad either.

We certainly hope she’s learned her lesson about impersonating a doctor, at this point, but maybe she should just go to medical school. If not, northern France might just end up with a new endocrinologist or oncologist floating around in 3 years.

No need to ‘guess what size horse you are’

Is COVID-19 warming up for yet another surge? Maybe. That means it’s also time for the return of its remora-like follower, ivermectin. Our thanks go out to the Tennessee state legislature for bringing the proven-to-be-ineffective treatment for COVID back into our hearts and minds and emergency rooms.

Both the state House and Senate have approved a bill that allows pharmacists to dispense the antiparasitic drug without a prescription while shielding them “from any liability that could arise from dispensing ivermectin,” Nashville Public Radio reported.

The drug’s manufacturer, Merck, said over a year ago that there is “no scientific basis for a potential therapeutic effect against COVID-19 from preclinical studies … and a concerning lack of safety data.” More recently, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that ivermectin treatment had no important benefits in patients with COVID.

Last week, the bill’s Senate sponsor, Frank Niceley of Strawberry Plains, said that it was all about safety, as he explained to NPR station WPLN: “It’s a lot safer to go to your pharmacist and let him tell you how much ivermectin to take than it is to go to the co-op and guess what size horse you are.”

And on that note, here are a few more items of business that just might end up on the legislature’s calendar:

- Horses will be allowed to “share” their unused ivermectin with humans and other mammals.

- An apple a day not only keeps the doctor away, but the IRS and the FDA as well.

- Colon cleansing is more fun than humans should be allowed to have.

- TikTok videos qualify as CME.

Who needs medical degrees anyway?

It’s no secret that doctors make a fair chunk of change. It’s a lucrative profession, but that big fat paycheck is siloed behind long, tough years of medical school and residency. It’s not an easy path doctors walk. Or at least, it’s not supposed to be. Anything’s easy if you’re willing to lie.

That brings us to Sonia, a 31-year-old woman from northern France with a bachelor’s degree in real estate management who wasn’t bringing in enough money for her three children, at least not to her satisfaction. Naturally, the only decision was to forge some diplomas from the University of Strasbourg, as well as a certificate from the French Order of Physicians. Sonia got hired as a general practitioner by using the identities of two doctors who shared her name. She had no experience, had no idea what she was doing, and was wearing a GPS tagging bracelet for an unrelated crime, so she was quickly caught and exposed in October 2021, after, um, 3 years of fake doctoring, according to France Live.

Not to be deterred by this temporary setback, Sonia proceeded to immediately find work as an ophthalmologist, a career that requires more than 10 years of training, continuing her fraudulent medical career until recently, when she was caught again and sentenced to 3 years in prison. She did make 70,000 euros a year as a fake doctor, which isn’t exactly huge money, but certainly not bad either.

We certainly hope she’s learned her lesson about impersonating a doctor, at this point, but maybe she should just go to medical school. If not, northern France might just end up with a new endocrinologist or oncologist floating around in 3 years.

Speak louder, I can’t see you

With the introduction of FaceTime and the pandemic pushing work and social events to Zoom, video calls have become ubiquitous. Along the way, however, we’ve had to learn to adjust to technical difficulties. Often by yelling at the screen when the video quality is disrupted. Waving our hands and arms, speaking louder. Sound like you?

Well, a new study published in Royal Society Open Science shows that it sounds like a lot of us.

James Trujillo of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, who was lead author of the paper, said on Eurekalert that “previous research has shown that speech and gestures are linked, but ours is the first to look into how visuals impact our behavior in those fields.”

He and his associates set up 40 participants in separate rooms to have conversations in pairs over a video chat. Over the course of 40 minutes, the video quality started to deteriorate from clear to extremely blurry. When the video quality was affected, participants started with gestures but as the quality continued to lessen the gestures increased and so did the decibels of their voices.

Even when the participants could barely see each other, they still gestured and their voices were even louder, positively supporting the idea that gestures and speech are a dynamically linked when it comes to communication. Even on regular phone calls, when we can’t see each other at all, people make small movements and gestures, Mr. Trujillo said.

So, the next time the Wifi is terrible and your video calls keep cutting out, don’t worry about looking foolish screaming at the computer. We’ve all been there.

Seek a doctor if standing at attention for more than 4 hours

Imbrochável. In Brazil, it means “unfloppable” or “flaccid proof.” It’s also a word that Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro likes to use when referring to himself. Gives you a good idea of what he’s all about. Imagine his embarrassment when news recently broke about more than 30,000 pills of Viagra that had been secretly distributed to the Brazilian military.

The military offered a simple and plausible explanation: The Viagra had been prescribed to treat pulmonary hypertension. Fair, but when a Brazilian newspaper dug a little deeper, they found that this was not the case. The Viagra was, in general, being used for its, shall we say, traditional purpose.

Many Brazilians reacted poorly to the news that their tax dollars were being used to provide Brazilian soldiers with downstairs assistance, with the standard associated furor on social media. A rival politician, Ciro Gomes, who is planning on challenging the president in an upcoming election, had perhaps the best remark on the situation: “Unless they’re able to prove they’re developing some kind of secret weapon – capable of revolutionizing the international arms industry – it’ll be tough to justify the purchase of 35,000 units of a erectile dysfunction drug.”

Hmm, secret weapon. Well, a certain Russian fellow has made a bit of a thrust into world affairs recently. Does anyone know if Putin is sitting on a big Viagra stash?

Who needs medical degrees anyway?

It’s no secret that doctors make a fair chunk of change. It’s a lucrative profession, but that big fat paycheck is siloed behind long, tough years of medical school and residency. It’s not an easy path doctors walk. Or at least, it’s not supposed to be. Anything’s easy if you’re willing to lie.

That brings us to Sonia, a 31-year-old woman from northern France with a bachelor’s degree in real estate management who wasn’t bringing in enough money for her three children, at least not to her satisfaction. Naturally, the only decision was to forge some diplomas from the University of Strasbourg, as well as a certificate from the French Order of Physicians. Sonia got hired as a general practitioner by using the identities of two doctors who shared her name. She had no experience, had no idea what she was doing, and was wearing a GPS tagging bracelet for an unrelated crime, so she was quickly caught and exposed in October 2021, after, um, 3 years of fake doctoring, according to France Live.

Not to be deterred by this temporary setback, Sonia proceeded to immediately find work as an ophthalmologist, a career that requires more than 10 years of training, continuing her fraudulent medical career until recently, when she was caught again and sentenced to 3 years in prison. She did make 70,000 euros a year as a fake doctor, which isn’t exactly huge money, but certainly not bad either.

We certainly hope she’s learned her lesson about impersonating a doctor, at this point, but maybe she should just go to medical school. If not, northern France might just end up with a new endocrinologist or oncologist floating around in 3 years.

No need to ‘guess what size horse you are’

Is COVID-19 warming up for yet another surge? Maybe. That means it’s also time for the return of its remora-like follower, ivermectin. Our thanks go out to the Tennessee state legislature for bringing the proven-to-be-ineffective treatment for COVID back into our hearts and minds and emergency rooms.

Both the state House and Senate have approved a bill that allows pharmacists to dispense the antiparasitic drug without a prescription while shielding them “from any liability that could arise from dispensing ivermectin,” Nashville Public Radio reported.

The drug’s manufacturer, Merck, said over a year ago that there is “no scientific basis for a potential therapeutic effect against COVID-19 from preclinical studies … and a concerning lack of safety data.” More recently, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that ivermectin treatment had no important benefits in patients with COVID.

Last week, the bill’s Senate sponsor, Frank Niceley of Strawberry Plains, said that it was all about safety, as he explained to NPR station WPLN: “It’s a lot safer to go to your pharmacist and let him tell you how much ivermectin to take than it is to go to the co-op and guess what size horse you are.”

And on that note, here are a few more items of business that just might end up on the legislature’s calendar:

- Horses will be allowed to “share” their unused ivermectin with humans and other mammals.

- An apple a day not only keeps the doctor away, but the IRS and the FDA as well.

- Colon cleansing is more fun than humans should be allowed to have.

- TikTok videos qualify as CME.

Who needs medical degrees anyway?

It’s no secret that doctors make a fair chunk of change. It’s a lucrative profession, but that big fat paycheck is siloed behind long, tough years of medical school and residency. It’s not an easy path doctors walk. Or at least, it’s not supposed to be. Anything’s easy if you’re willing to lie.

That brings us to Sonia, a 31-year-old woman from northern France with a bachelor’s degree in real estate management who wasn’t bringing in enough money for her three children, at least not to her satisfaction. Naturally, the only decision was to forge some diplomas from the University of Strasbourg, as well as a certificate from the French Order of Physicians. Sonia got hired as a general practitioner by using the identities of two doctors who shared her name. She had no experience, had no idea what she was doing, and was wearing a GPS tagging bracelet for an unrelated crime, so she was quickly caught and exposed in October 2021, after, um, 3 years of fake doctoring, according to France Live.

Not to be deterred by this temporary setback, Sonia proceeded to immediately find work as an ophthalmologist, a career that requires more than 10 years of training, continuing her fraudulent medical career until recently, when she was caught again and sentenced to 3 years in prison. She did make 70,000 euros a year as a fake doctor, which isn’t exactly huge money, but certainly not bad either.

We certainly hope she’s learned her lesson about impersonating a doctor, at this point, but maybe she should just go to medical school. If not, northern France might just end up with a new endocrinologist or oncologist floating around in 3 years.

Speak louder, I can’t see you

With the introduction of FaceTime and the pandemic pushing work and social events to Zoom, video calls have become ubiquitous. Along the way, however, we’ve had to learn to adjust to technical difficulties. Often by yelling at the screen when the video quality is disrupted. Waving our hands and arms, speaking louder. Sound like you?

Well, a new study published in Royal Society Open Science shows that it sounds like a lot of us.

James Trujillo of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, who was lead author of the paper, said on Eurekalert that “previous research has shown that speech and gestures are linked, but ours is the first to look into how visuals impact our behavior in those fields.”

He and his associates set up 40 participants in separate rooms to have conversations in pairs over a video chat. Over the course of 40 minutes, the video quality started to deteriorate from clear to extremely blurry. When the video quality was affected, participants started with gestures but as the quality continued to lessen the gestures increased and so did the decibels of their voices.

Even when the participants could barely see each other, they still gestured and their voices were even louder, positively supporting the idea that gestures and speech are a dynamically linked when it comes to communication. Even on regular phone calls, when we can’t see each other at all, people make small movements and gestures, Mr. Trujillo said.

So, the next time the Wifi is terrible and your video calls keep cutting out, don’t worry about looking foolish screaming at the computer. We’ve all been there.

Seek a doctor if standing at attention for more than 4 hours

Imbrochável. In Brazil, it means “unfloppable” or “flaccid proof.” It’s also a word that Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro likes to use when referring to himself. Gives you a good idea of what he’s all about. Imagine his embarrassment when news recently broke about more than 30,000 pills of Viagra that had been secretly distributed to the Brazilian military.

The military offered a simple and plausible explanation: The Viagra had been prescribed to treat pulmonary hypertension. Fair, but when a Brazilian newspaper dug a little deeper, they found that this was not the case. The Viagra was, in general, being used for its, shall we say, traditional purpose.

Many Brazilians reacted poorly to the news that their tax dollars were being used to provide Brazilian soldiers with downstairs assistance, with the standard associated furor on social media. A rival politician, Ciro Gomes, who is planning on challenging the president in an upcoming election, had perhaps the best remark on the situation: “Unless they’re able to prove they’re developing some kind of secret weapon – capable of revolutionizing the international arms industry – it’ll be tough to justify the purchase of 35,000 units of a erectile dysfunction drug.”

Hmm, secret weapon. Well, a certain Russian fellow has made a bit of a thrust into world affairs recently. Does anyone know if Putin is sitting on a big Viagra stash?

Who needs medical degrees anyway?

It’s no secret that doctors make a fair chunk of change. It’s a lucrative profession, but that big fat paycheck is siloed behind long, tough years of medical school and residency. It’s not an easy path doctors walk. Or at least, it’s not supposed to be. Anything’s easy if you’re willing to lie.

That brings us to Sonia, a 31-year-old woman from northern France with a bachelor’s degree in real estate management who wasn’t bringing in enough money for her three children, at least not to her satisfaction. Naturally, the only decision was to forge some diplomas from the University of Strasbourg, as well as a certificate from the French Order of Physicians. Sonia got hired as a general practitioner by using the identities of two doctors who shared her name. She had no experience, had no idea what she was doing, and was wearing a GPS tagging bracelet for an unrelated crime, so she was quickly caught and exposed in October 2021, after, um, 3 years of fake doctoring, according to France Live.

Not to be deterred by this temporary setback, Sonia proceeded to immediately find work as an ophthalmologist, a career that requires more than 10 years of training, continuing her fraudulent medical career until recently, when she was caught again and sentenced to 3 years in prison. She did make 70,000 euros a year as a fake doctor, which isn’t exactly huge money, but certainly not bad either.

We certainly hope she’s learned her lesson about impersonating a doctor, at this point, but maybe she should just go to medical school. If not, northern France might just end up with a new endocrinologist or oncologist floating around in 3 years.

No need to ‘guess what size horse you are’

Is COVID-19 warming up for yet another surge? Maybe. That means it’s also time for the return of its remora-like follower, ivermectin. Our thanks go out to the Tennessee state legislature for bringing the proven-to-be-ineffective treatment for COVID back into our hearts and minds and emergency rooms.

Both the state House and Senate have approved a bill that allows pharmacists to dispense the antiparasitic drug without a prescription while shielding them “from any liability that could arise from dispensing ivermectin,” Nashville Public Radio reported.

The drug’s manufacturer, Merck, said over a year ago that there is “no scientific basis for a potential therapeutic effect against COVID-19 from preclinical studies … and a concerning lack of safety data.” More recently, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that ivermectin treatment had no important benefits in patients with COVID.

Last week, the bill’s Senate sponsor, Frank Niceley of Strawberry Plains, said that it was all about safety, as he explained to NPR station WPLN: “It’s a lot safer to go to your pharmacist and let him tell you how much ivermectin to take than it is to go to the co-op and guess what size horse you are.”

And on that note, here are a few more items of business that just might end up on the legislature’s calendar:

- Horses will be allowed to “share” their unused ivermectin with humans and other mammals.

- An apple a day not only keeps the doctor away, but the IRS and the FDA as well.

- Colon cleansing is more fun than humans should be allowed to have.

- TikTok videos qualify as CME.

Who needs medical degrees anyway?

It’s no secret that doctors make a fair chunk of change. It’s a lucrative profession, but that big fat paycheck is siloed behind long, tough years of medical school and residency. It’s not an easy path doctors walk. Or at least, it’s not supposed to be. Anything’s easy if you’re willing to lie.

That brings us to Sonia, a 31-year-old woman from northern France with a bachelor’s degree in real estate management who wasn’t bringing in enough money for her three children, at least not to her satisfaction. Naturally, the only decision was to forge some diplomas from the University of Strasbourg, as well as a certificate from the French Order of Physicians. Sonia got hired as a general practitioner by using the identities of two doctors who shared her name. She had no experience, had no idea what she was doing, and was wearing a GPS tagging bracelet for an unrelated crime, so she was quickly caught and exposed in October 2021, after, um, 3 years of fake doctoring, according to France Live.

Not to be deterred by this temporary setback, Sonia proceeded to immediately find work as an ophthalmologist, a career that requires more than 10 years of training, continuing her fraudulent medical career until recently, when she was caught again and sentenced to 3 years in prison. She did make 70,000 euros a year as a fake doctor, which isn’t exactly huge money, but certainly not bad either.

We certainly hope she’s learned her lesson about impersonating a doctor, at this point, but maybe she should just go to medical school. If not, northern France might just end up with a new endocrinologist or oncologist floating around in 3 years.

Speak louder, I can’t see you

With the introduction of FaceTime and the pandemic pushing work and social events to Zoom, video calls have become ubiquitous. Along the way, however, we’ve had to learn to adjust to technical difficulties. Often by yelling at the screen when the video quality is disrupted. Waving our hands and arms, speaking louder. Sound like you?

Well, a new study published in Royal Society Open Science shows that it sounds like a lot of us.

James Trujillo of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, who was lead author of the paper, said on Eurekalert that “previous research has shown that speech and gestures are linked, but ours is the first to look into how visuals impact our behavior in those fields.”

He and his associates set up 40 participants in separate rooms to have conversations in pairs over a video chat. Over the course of 40 minutes, the video quality started to deteriorate from clear to extremely blurry. When the video quality was affected, participants started with gestures but as the quality continued to lessen the gestures increased and so did the decibels of their voices.

Even when the participants could barely see each other, they still gestured and their voices were even louder, positively supporting the idea that gestures and speech are a dynamically linked when it comes to communication. Even on regular phone calls, when we can’t see each other at all, people make small movements and gestures, Mr. Trujillo said.

So, the next time the Wifi is terrible and your video calls keep cutting out, don’t worry about looking foolish screaming at the computer. We’ve all been there.

Seek a doctor if standing at attention for more than 4 hours

Imbrochável. In Brazil, it means “unfloppable” or “flaccid proof.” It’s also a word that Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro likes to use when referring to himself. Gives you a good idea of what he’s all about. Imagine his embarrassment when news recently broke about more than 30,000 pills of Viagra that had been secretly distributed to the Brazilian military.

The military offered a simple and plausible explanation: The Viagra had been prescribed to treat pulmonary hypertension. Fair, but when a Brazilian newspaper dug a little deeper, they found that this was not the case. The Viagra was, in general, being used for its, shall we say, traditional purpose.

Many Brazilians reacted poorly to the news that their tax dollars were being used to provide Brazilian soldiers with downstairs assistance, with the standard associated furor on social media. A rival politician, Ciro Gomes, who is planning on challenging the president in an upcoming election, had perhaps the best remark on the situation: “Unless they’re able to prove they’re developing some kind of secret weapon – capable of revolutionizing the international arms industry – it’ll be tough to justify the purchase of 35,000 units of a erectile dysfunction drug.”

Hmm, secret weapon. Well, a certain Russian fellow has made a bit of a thrust into world affairs recently. Does anyone know if Putin is sitting on a big Viagra stash?

COVID-19 cardiovascular complications in children: AHA statement

Cardiovascular complications are uncommon for children and young adults after COVID-19 disease or SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to a new scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

However, the infection can cause some children and young people to experience arrhythmias, myocarditis, pericarditis, or multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), a new condition identified during the pandemic, it notes.

The statement details what has been learned about how to treat, manage, and prevent cardiovascular complications associated with COVID-19 in children and young adults and calls for more research, including studies following the short- and long-term cardiovascular effects.

It also reports that COVID-19 vaccines have been found to prevent severe COVID-19 disease and decrease the risk of developing MIS-C by 91% among children ages 12-18 years.

On returning to sports, it says data suggest it is safe for young people with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 to resume exercise after recovery from symptoms. For those with more serious infections, it recommends additional tests, including cardiac enzyme levels, electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram, before returning to sports or strenuous physical exercise.

The scientific statement was published online on in Circulation.

“Two years into the pandemic and with vast amounts of research conducted in children with COVID-19, this statement summarizes what we know so far related to COVID-19 in children,” said chair of the statement writing group Pei-Ni Jone, MD, from the Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

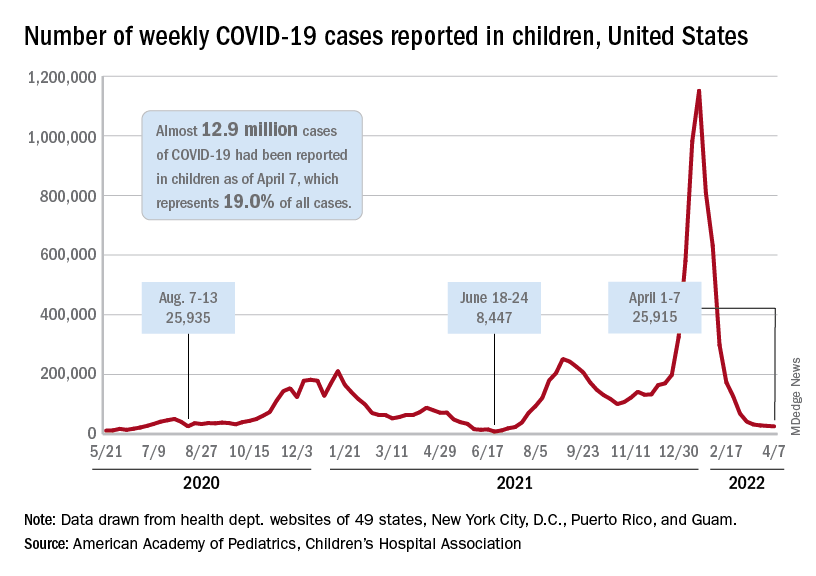

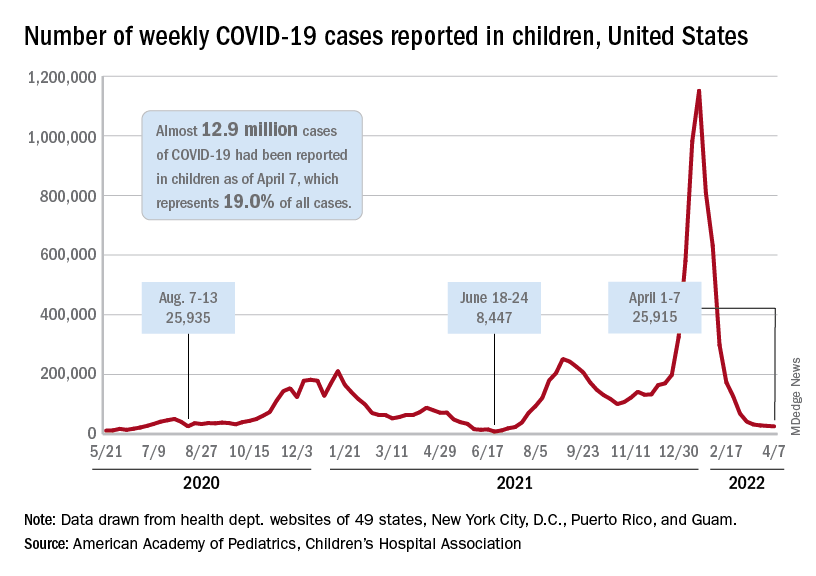

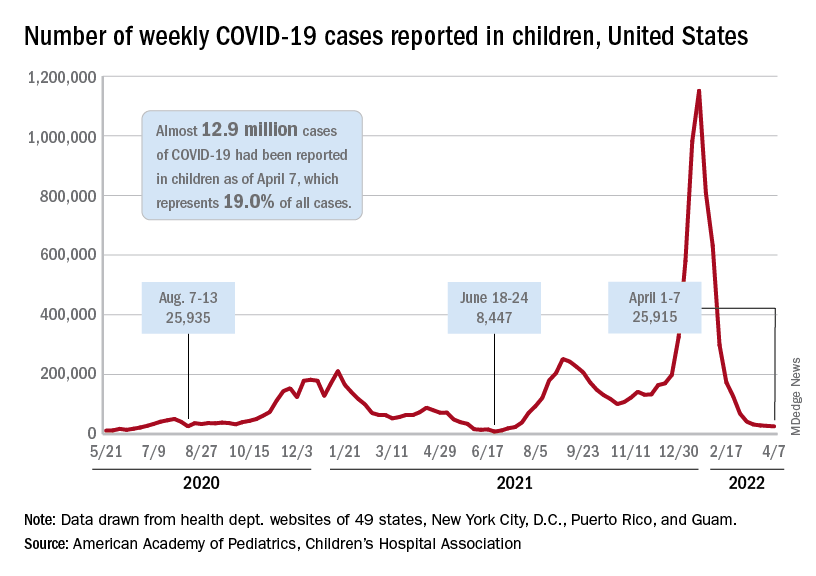

Analysis of the latest research indicates children generally have mild symptoms from SARS-CoV-2 infection. In the U.S., as of Feb. 24, 2022, children under 18 years of age have accounted for 17.6% of total COVID-19 cases and about 0.1% of deaths from the virus, the report states.

In addition, young adults, ages 18-29 years, have accounted for 21.3% of cases and 0.8% of deaths from COVID-19.

Like adults, children with underlying medical conditions such as chronic lung disease or obesity and those who are immunocompromised are more likely to be hospitalized, to be admitted to an intensive care unit, and to die of COVID-19, the statement notes. There are conflicting reports on the risk of severe COVID-19 in children and young adults with congenital heart disease, with some reports suggesting a slightly increased risk of severe COVID-19.

In terms of cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 in children, arrhythmias have included ventricular tachycardia and atrial tachycardia, as well as first-degree atrioventricular block. Although arrhythmias generally self-resolve without the need for treatment, prophylactic antiarrhythmics have been administered in some cases, and death caused by recurrent ventricular tachycardia in an adolescent with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has been described.

Elevations of troponin, electrocardiographic abnormalities, including ST-segment changes, and delayed gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging have been seen in those with myocardial involvement. Although death is rare, both sudden cardiac death and death after intensive medical and supportive therapies have occurred in children with severe myocardial involvement.

In a large retrospective pediatric case series of SARS-CoV-2–associated deaths in individuals under 21 years of age, the median age at death was 17 years, 63% were male, 28% were Black, and 46% were Hispanic. Of those who died, 86% had a comorbid condition, with obesity (42%) and asthma (29%) being the most common.

But the report concludes that: “Although children with comorbidities are at increased risk for symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection, compared with healthy children, cardiovascular complications, severe illness, and death are uncommon.”

MIS-C: Rare but severe

The authors of the statement explain that children and some young adults may develop MIS-C, a relatively rare but severe inflammatory syndrome generally occurring 2-6 weeks after infection with SARS-CoV-2 that can affect the heart and multiple organ systems.

In the first year of the pandemic, more than 2,600 cases of MIS-C were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, at an estimated rate of 1 case per 3,164 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children, with MIS-C disproportionately affecting Hispanic and Black children.

As many as 50% of children with MIS-C have myocardial involvement, including decreased left ventricular function, coronary artery dilation or aneurysms, myocarditis, elevated troponin and BNP or NT-proBNP, or pericardial effusion. Acute-phase reactants, including C-reactive protein, D-dimer, ferritin, and fibrinogen, can be significantly elevated in MIS-C, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio may be higher, and platelet counts lower than those with non–MIS-C febrile illnesses.

Fortunately, the outcome of MIS-C is generally very good, with resolution of inflammation and cardiovascular abnormalities within 1-4 weeks of diagnosis, the report says.

However, there have been reports of progression of coronary artery aneurysms after discharge, highlighting the potential for long-term complications. Death resulting from MIS-C is rare, with a mortality rate of 1.4%-1.9%.

Compared with children and young adults who died of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, most of the fatalities from MIS-C were in previously healthy individuals without comorbidities.

The authors recommend structured follow-up of patients with MIS-C because of concern about progression of cardiac complications and an unclear long-term prognosis.

The statement notes that the first-line treatment for MIS-C is typically intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and patients with poor ventricular function may need to have IVIG in divided doses to tolerate the fluid load.

Supportive treatment for heart failure and vasoplegic shock often requires aggressive management in an ICU for administration of inotropes and vasoactive medications. Antiplatelet therapy with low-dose aspirin is considered in patients with coronary artery involvement, and anticoagulation is added, depending on the degree of coronary artery dilation.

COVID-19 vaccination

The statement notes that vaccines can prevent patients from getting COVID-19 and decrease the risk of MIS-C by 91% among children 12-18 years of age.

On vaccine-associated myocarditis, it concludes the benefits of getting the vaccines outweigh the risks.

For example, for every 1 million doses of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in males ages 12-29 years (the highest risk group for vaccine-associated myocarditis), it is estimated that 11,000 COVID-19 cases, 560 hospitalizations, and six deaths would be prevented, whereas 39-47 cases of myocarditis would be expected.

But it adds that the CDC is continuing to follow myocarditis in children and young adults closely, particularly a possible connection to the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines.

The statement says that more research is needed to better understand the mechanisms and optimal treatment approaches for SARS-CoV-2 infection, vaccine-associated myocarditis, the long-term outcomes of both COVID-19 and MIS-C, and the impact of these various conditions on the heart in children and young adults. In addition, any new antiviral therapies need to be tested in clinical trials focused on children.

“Although much has been learned about how the virus impacts children’s and young adult’s hearts, how to best treat cardiovascular complications, and prevent severe illness, continued clinical research trials are needed to better understand the long-term cardiovascular impacts,” Dr. Jone said. “It is also important to address health disparities that have become more apparent during the pandemic. We must work to ensure all children receive equal access to vaccination and high-quality care.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiovascular complications are uncommon for children and young adults after COVID-19 disease or SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to a new scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

However, the infection can cause some children and young people to experience arrhythmias, myocarditis, pericarditis, or multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), a new condition identified during the pandemic, it notes.

The statement details what has been learned about how to treat, manage, and prevent cardiovascular complications associated with COVID-19 in children and young adults and calls for more research, including studies following the short- and long-term cardiovascular effects.

It also reports that COVID-19 vaccines have been found to prevent severe COVID-19 disease and decrease the risk of developing MIS-C by 91% among children ages 12-18 years.

On returning to sports, it says data suggest it is safe for young people with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 to resume exercise after recovery from symptoms. For those with more serious infections, it recommends additional tests, including cardiac enzyme levels, electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram, before returning to sports or strenuous physical exercise.

The scientific statement was published online on in Circulation.

“Two years into the pandemic and with vast amounts of research conducted in children with COVID-19, this statement summarizes what we know so far related to COVID-19 in children,” said chair of the statement writing group Pei-Ni Jone, MD, from the Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

Analysis of the latest research indicates children generally have mild symptoms from SARS-CoV-2 infection. In the U.S., as of Feb. 24, 2022, children under 18 years of age have accounted for 17.6% of total COVID-19 cases and about 0.1% of deaths from the virus, the report states.

In addition, young adults, ages 18-29 years, have accounted for 21.3% of cases and 0.8% of deaths from COVID-19.

Like adults, children with underlying medical conditions such as chronic lung disease or obesity and those who are immunocompromised are more likely to be hospitalized, to be admitted to an intensive care unit, and to die of COVID-19, the statement notes. There are conflicting reports on the risk of severe COVID-19 in children and young adults with congenital heart disease, with some reports suggesting a slightly increased risk of severe COVID-19.

In terms of cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 in children, arrhythmias have included ventricular tachycardia and atrial tachycardia, as well as first-degree atrioventricular block. Although arrhythmias generally self-resolve without the need for treatment, prophylactic antiarrhythmics have been administered in some cases, and death caused by recurrent ventricular tachycardia in an adolescent with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has been described.

Elevations of troponin, electrocardiographic abnormalities, including ST-segment changes, and delayed gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging have been seen in those with myocardial involvement. Although death is rare, both sudden cardiac death and death after intensive medical and supportive therapies have occurred in children with severe myocardial involvement.

In a large retrospective pediatric case series of SARS-CoV-2–associated deaths in individuals under 21 years of age, the median age at death was 17 years, 63% were male, 28% were Black, and 46% were Hispanic. Of those who died, 86% had a comorbid condition, with obesity (42%) and asthma (29%) being the most common.

But the report concludes that: “Although children with comorbidities are at increased risk for symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection, compared with healthy children, cardiovascular complications, severe illness, and death are uncommon.”

MIS-C: Rare but severe

The authors of the statement explain that children and some young adults may develop MIS-C, a relatively rare but severe inflammatory syndrome generally occurring 2-6 weeks after infection with SARS-CoV-2 that can affect the heart and multiple organ systems.

In the first year of the pandemic, more than 2,600 cases of MIS-C were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, at an estimated rate of 1 case per 3,164 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children, with MIS-C disproportionately affecting Hispanic and Black children.

As many as 50% of children with MIS-C have myocardial involvement, including decreased left ventricular function, coronary artery dilation or aneurysms, myocarditis, elevated troponin and BNP or NT-proBNP, or pericardial effusion. Acute-phase reactants, including C-reactive protein, D-dimer, ferritin, and fibrinogen, can be significantly elevated in MIS-C, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio may be higher, and platelet counts lower than those with non–MIS-C febrile illnesses.

Fortunately, the outcome of MIS-C is generally very good, with resolution of inflammation and cardiovascular abnormalities within 1-4 weeks of diagnosis, the report says.

However, there have been reports of progression of coronary artery aneurysms after discharge, highlighting the potential for long-term complications. Death resulting from MIS-C is rare, with a mortality rate of 1.4%-1.9%.

Compared with children and young adults who died of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, most of the fatalities from MIS-C were in previously healthy individuals without comorbidities.

The authors recommend structured follow-up of patients with MIS-C because of concern about progression of cardiac complications and an unclear long-term prognosis.

The statement notes that the first-line treatment for MIS-C is typically intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and patients with poor ventricular function may need to have IVIG in divided doses to tolerate the fluid load.

Supportive treatment for heart failure and vasoplegic shock often requires aggressive management in an ICU for administration of inotropes and vasoactive medications. Antiplatelet therapy with low-dose aspirin is considered in patients with coronary artery involvement, and anticoagulation is added, depending on the degree of coronary artery dilation.

COVID-19 vaccination

The statement notes that vaccines can prevent patients from getting COVID-19 and decrease the risk of MIS-C by 91% among children 12-18 years of age.

On vaccine-associated myocarditis, it concludes the benefits of getting the vaccines outweigh the risks.

For example, for every 1 million doses of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in males ages 12-29 years (the highest risk group for vaccine-associated myocarditis), it is estimated that 11,000 COVID-19 cases, 560 hospitalizations, and six deaths would be prevented, whereas 39-47 cases of myocarditis would be expected.

But it adds that the CDC is continuing to follow myocarditis in children and young adults closely, particularly a possible connection to the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines.

The statement says that more research is needed to better understand the mechanisms and optimal treatment approaches for SARS-CoV-2 infection, vaccine-associated myocarditis, the long-term outcomes of both COVID-19 and MIS-C, and the impact of these various conditions on the heart in children and young adults. In addition, any new antiviral therapies need to be tested in clinical trials focused on children.

“Although much has been learned about how the virus impacts children’s and young adult’s hearts, how to best treat cardiovascular complications, and prevent severe illness, continued clinical research trials are needed to better understand the long-term cardiovascular impacts,” Dr. Jone said. “It is also important to address health disparities that have become more apparent during the pandemic. We must work to ensure all children receive equal access to vaccination and high-quality care.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiovascular complications are uncommon for children and young adults after COVID-19 disease or SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to a new scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

However, the infection can cause some children and young people to experience arrhythmias, myocarditis, pericarditis, or multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), a new condition identified during the pandemic, it notes.

The statement details what has been learned about how to treat, manage, and prevent cardiovascular complications associated with COVID-19 in children and young adults and calls for more research, including studies following the short- and long-term cardiovascular effects.

It also reports that COVID-19 vaccines have been found to prevent severe COVID-19 disease and decrease the risk of developing MIS-C by 91% among children ages 12-18 years.

On returning to sports, it says data suggest it is safe for young people with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 to resume exercise after recovery from symptoms. For those with more serious infections, it recommends additional tests, including cardiac enzyme levels, electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram, before returning to sports or strenuous physical exercise.

The scientific statement was published online on in Circulation.

“Two years into the pandemic and with vast amounts of research conducted in children with COVID-19, this statement summarizes what we know so far related to COVID-19 in children,” said chair of the statement writing group Pei-Ni Jone, MD, from the Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

Analysis of the latest research indicates children generally have mild symptoms from SARS-CoV-2 infection. In the U.S., as of Feb. 24, 2022, children under 18 years of age have accounted for 17.6% of total COVID-19 cases and about 0.1% of deaths from the virus, the report states.

In addition, young adults, ages 18-29 years, have accounted for 21.3% of cases and 0.8% of deaths from COVID-19.

Like adults, children with underlying medical conditions such as chronic lung disease or obesity and those who are immunocompromised are more likely to be hospitalized, to be admitted to an intensive care unit, and to die of COVID-19, the statement notes. There are conflicting reports on the risk of severe COVID-19 in children and young adults with congenital heart disease, with some reports suggesting a slightly increased risk of severe COVID-19.

In terms of cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 in children, arrhythmias have included ventricular tachycardia and atrial tachycardia, as well as first-degree atrioventricular block. Although arrhythmias generally self-resolve without the need for treatment, prophylactic antiarrhythmics have been administered in some cases, and death caused by recurrent ventricular tachycardia in an adolescent with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has been described.

Elevations of troponin, electrocardiographic abnormalities, including ST-segment changes, and delayed gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging have been seen in those with myocardial involvement. Although death is rare, both sudden cardiac death and death after intensive medical and supportive therapies have occurred in children with severe myocardial involvement.

In a large retrospective pediatric case series of SARS-CoV-2–associated deaths in individuals under 21 years of age, the median age at death was 17 years, 63% were male, 28% were Black, and 46% were Hispanic. Of those who died, 86% had a comorbid condition, with obesity (42%) and asthma (29%) being the most common.

But the report concludes that: “Although children with comorbidities are at increased risk for symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection, compared with healthy children, cardiovascular complications, severe illness, and death are uncommon.”

MIS-C: Rare but severe

The authors of the statement explain that children and some young adults may develop MIS-C, a relatively rare but severe inflammatory syndrome generally occurring 2-6 weeks after infection with SARS-CoV-2 that can affect the heart and multiple organ systems.

In the first year of the pandemic, more than 2,600 cases of MIS-C were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, at an estimated rate of 1 case per 3,164 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children, with MIS-C disproportionately affecting Hispanic and Black children.

As many as 50% of children with MIS-C have myocardial involvement, including decreased left ventricular function, coronary artery dilation or aneurysms, myocarditis, elevated troponin and BNP or NT-proBNP, or pericardial effusion. Acute-phase reactants, including C-reactive protein, D-dimer, ferritin, and fibrinogen, can be significantly elevated in MIS-C, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio may be higher, and platelet counts lower than those with non–MIS-C febrile illnesses.

Fortunately, the outcome of MIS-C is generally very good, with resolution of inflammation and cardiovascular abnormalities within 1-4 weeks of diagnosis, the report says.

However, there have been reports of progression of coronary artery aneurysms after discharge, highlighting the potential for long-term complications. Death resulting from MIS-C is rare, with a mortality rate of 1.4%-1.9%.

Compared with children and young adults who died of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, most of the fatalities from MIS-C were in previously healthy individuals without comorbidities.

The authors recommend structured follow-up of patients with MIS-C because of concern about progression of cardiac complications and an unclear long-term prognosis.

The statement notes that the first-line treatment for MIS-C is typically intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and patients with poor ventricular function may need to have IVIG in divided doses to tolerate the fluid load.

Supportive treatment for heart failure and vasoplegic shock often requires aggressive management in an ICU for administration of inotropes and vasoactive medications. Antiplatelet therapy with low-dose aspirin is considered in patients with coronary artery involvement, and anticoagulation is added, depending on the degree of coronary artery dilation.

COVID-19 vaccination

The statement notes that vaccines can prevent patients from getting COVID-19 and decrease the risk of MIS-C by 91% among children 12-18 years of age.

On vaccine-associated myocarditis, it concludes the benefits of getting the vaccines outweigh the risks.

For example, for every 1 million doses of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in males ages 12-29 years (the highest risk group for vaccine-associated myocarditis), it is estimated that 11,000 COVID-19 cases, 560 hospitalizations, and six deaths would be prevented, whereas 39-47 cases of myocarditis would be expected.

But it adds that the CDC is continuing to follow myocarditis in children and young adults closely, particularly a possible connection to the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines.

The statement says that more research is needed to better understand the mechanisms and optimal treatment approaches for SARS-CoV-2 infection, vaccine-associated myocarditis, the long-term outcomes of both COVID-19 and MIS-C, and the impact of these various conditions on the heart in children and young adults. In addition, any new antiviral therapies need to be tested in clinical trials focused on children.

“Although much has been learned about how the virus impacts children’s and young adult’s hearts, how to best treat cardiovascular complications, and prevent severe illness, continued clinical research trials are needed to better understand the long-term cardiovascular impacts,” Dr. Jone said. “It is also important to address health disparities that have become more apparent during the pandemic. We must work to ensure all children receive equal access to vaccination and high-quality care.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CIRCULATION

Breakthrough COVID dangerous for vaccinated cancer patients

, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

The risks were highest among patients who had certain cancers and those who had received cancer treatment within the past year.

“These results emphasize the need for patients with cancer to maintain mitigation practice, especially with the emergence of different virus variants and the waning immunity of vaccines,” the study authors wrote.

Researchers at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland analyzed electronic health record data for more than 636,000 vaccinated patients, including more than 45,000 vaccinated patients with cancer. They looked for the time trends, risks, and outcomes of breakthrough COVID-19 infections for vaccinated cancer patients in the United States between December 2020 and November 2021.

Overall, the cumulative risk of breakthrough infections in vaccinated cancer patients was 13.6%, with the highest risk for pancreatic (24.7%), liver (22.8%), lung (20.4%), and colorectal (17.5%) cancers and the lowest risk for thyroid (10.3%), endometrial (11.9%), and breast (11.9%) cancers, versus 4.9% in vaccinated patients without cancer.

Patients who had medical encounters for their cancer within the past year had a higher risk for a breakthrough infection, particularly those with breast cancer, blood cancers, colorectal cancer, bladder cancer, and pancreatic cancer.

Among patients with cancer, the overall risk for hospitalization after a breakthrough infection was 31.6%, as compared with 3.9% in those without a breakthrough infection. In addition, the risk of death was 6.7% after a breakthrough infection, as compared with 1.3% in those without a breakthrough infection.

Among patients who didn’t have cancer, the overall hospitalization risk was 25.9% in patients with a breakthrough infection, as compared with 3% in those without a breakthrough infection. The overall risk of death was 2.7% after a breakthrough infection, as compared with 0.5% in those without a breakthrough infection.

In addition, breakthrough infections continuously increased for all patients from December 2020 to November 2021, with the numbers consistently higher among patients with cancer.

“This increasing time trend may reflect waning immunity of vaccines, the emergence of different virus variants, and varied measures taken by individuals and communities over time during the pandemic,” the study authors wrote.

Vaccines are likely less protective against coronavirus infection in cancer patients, and in turn, cancer patients may be more susceptible to COVID-19 infections, the researchers wrote. As breakthrough infections continue to increase for everyone, patients with cancer will face increased risks for severe breakthroughs, hospitalization, and death, they concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

The risks were highest among patients who had certain cancers and those who had received cancer treatment within the past year.

“These results emphasize the need for patients with cancer to maintain mitigation practice, especially with the emergence of different virus variants and the waning immunity of vaccines,” the study authors wrote.

Researchers at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland analyzed electronic health record data for more than 636,000 vaccinated patients, including more than 45,000 vaccinated patients with cancer. They looked for the time trends, risks, and outcomes of breakthrough COVID-19 infections for vaccinated cancer patients in the United States between December 2020 and November 2021.

Overall, the cumulative risk of breakthrough infections in vaccinated cancer patients was 13.6%, with the highest risk for pancreatic (24.7%), liver (22.8%), lung (20.4%), and colorectal (17.5%) cancers and the lowest risk for thyroid (10.3%), endometrial (11.9%), and breast (11.9%) cancers, versus 4.9% in vaccinated patients without cancer.

Patients who had medical encounters for their cancer within the past year had a higher risk for a breakthrough infection, particularly those with breast cancer, blood cancers, colorectal cancer, bladder cancer, and pancreatic cancer.

Among patients with cancer, the overall risk for hospitalization after a breakthrough infection was 31.6%, as compared with 3.9% in those without a breakthrough infection. In addition, the risk of death was 6.7% after a breakthrough infection, as compared with 1.3% in those without a breakthrough infection.

Among patients who didn’t have cancer, the overall hospitalization risk was 25.9% in patients with a breakthrough infection, as compared with 3% in those without a breakthrough infection. The overall risk of death was 2.7% after a breakthrough infection, as compared with 0.5% in those without a breakthrough infection.

In addition, breakthrough infections continuously increased for all patients from December 2020 to November 2021, with the numbers consistently higher among patients with cancer.

“This increasing time trend may reflect waning immunity of vaccines, the emergence of different virus variants, and varied measures taken by individuals and communities over time during the pandemic,” the study authors wrote.

Vaccines are likely less protective against coronavirus infection in cancer patients, and in turn, cancer patients may be more susceptible to COVID-19 infections, the researchers wrote. As breakthrough infections continue to increase for everyone, patients with cancer will face increased risks for severe breakthroughs, hospitalization, and death, they concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

The risks were highest among patients who had certain cancers and those who had received cancer treatment within the past year.

“These results emphasize the need for patients with cancer to maintain mitigation practice, especially with the emergence of different virus variants and the waning immunity of vaccines,” the study authors wrote.

Researchers at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland analyzed electronic health record data for more than 636,000 vaccinated patients, including more than 45,000 vaccinated patients with cancer. They looked for the time trends, risks, and outcomes of breakthrough COVID-19 infections for vaccinated cancer patients in the United States between December 2020 and November 2021.

Overall, the cumulative risk of breakthrough infections in vaccinated cancer patients was 13.6%, with the highest risk for pancreatic (24.7%), liver (22.8%), lung (20.4%), and colorectal (17.5%) cancers and the lowest risk for thyroid (10.3%), endometrial (11.9%), and breast (11.9%) cancers, versus 4.9% in vaccinated patients without cancer.

Patients who had medical encounters for their cancer within the past year had a higher risk for a breakthrough infection, particularly those with breast cancer, blood cancers, colorectal cancer, bladder cancer, and pancreatic cancer.

Among patients with cancer, the overall risk for hospitalization after a breakthrough infection was 31.6%, as compared with 3.9% in those without a breakthrough infection. In addition, the risk of death was 6.7% after a breakthrough infection, as compared with 1.3% in those without a breakthrough infection.

Among patients who didn’t have cancer, the overall hospitalization risk was 25.9% in patients with a breakthrough infection, as compared with 3% in those without a breakthrough infection. The overall risk of death was 2.7% after a breakthrough infection, as compared with 0.5% in those without a breakthrough infection.

In addition, breakthrough infections continuously increased for all patients from December 2020 to November 2021, with the numbers consistently higher among patients with cancer.

“This increasing time trend may reflect waning immunity of vaccines, the emergence of different virus variants, and varied measures taken by individuals and communities over time during the pandemic,” the study authors wrote.

Vaccines are likely less protective against coronavirus infection in cancer patients, and in turn, cancer patients may be more susceptible to COVID-19 infections, the researchers wrote. As breakthrough infections continue to increase for everyone, patients with cancer will face increased risks for severe breakthroughs, hospitalization, and death, they concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Long-term smell loss in COVID-19 tied to damage in the brain’s olfactory bulb

Patients with COVID-19, especially those with an altered sense of smell, have significantly more axon and microvasculopathy damage in the brain’s olfactory tissue versus non-COVID patients. These new findings from a postmortem study may explain long-term loss of smell in some patients with the virus.

“The striking axonal pathology in some cases indicates that olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19 may be severe and permanent,” the investigators led by Cheng-Ying Ho, MD, PhD, associate professor, department of pathology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, write.

“The results show the damage caused by COVID can extend beyond the nasal cavity and involve the brain,” Dr. Ho told this news organization.

The study was published online April 11 in JAMA Neurology.

A more thorough investigation

Patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, present with a wide range of symptoms. In addition to respiratory illnesses, they may exhibit various nonrespiratory manifestations of COVID-19.

One of the most prevalent of these is olfactory dysfunction. Research shows such dysfunction, including anosmia (loss of smell), hyposmia (reduced sense of smell), and parosmia (smells that are distorted or unpleasant), affects 30%-60% of patients with COVID-19, said Dr. Ho.

However, these statistics come from research before the advent of the Omicron variant, which evidence suggests causes less smell loss in patients with COVID, she said.

Previous studies in this area mainly focused on the lining of the nasal cavity. “We wanted to go a step beyond to see how the olfactory bulb was affected by COVID infection,” said Dr. Ho.

The study included 23 deceased patients with confirmed COVID-19 ranging in age from 28 to 93 years at death (median 62 years, 60.9% men). It also included 14 controls who tested negative for COVID-19, ranging in age from 20 to 77 years (median 53.5 years, 50% men).

Researchers collected postmortem tissue from the brain, lung, and other organs and reviewed pertinent clinical information.

Most patients with COVID died of COVID pneumonia or related complications, although some died from a different cause. Some had an active COVID infection and others were “post infection, meaning they were in the recovery stage,” said Dr. Ho.

Six patients with COVID-19 and eight controls had significant brain pathology.

Compared with controls, those with COVID-19 showed significantly worse olfactory axonal damage. The mean axon pathology score (range 1-3 with 3 the worst) was 1.921 in patients with COVID-19 and 1.198 in controls (95% confidence interval, 0.444-1.002; P < .001).

The mean axon density in the lateral olfactory tract was significantly less in patients with COVID-19 than in controls (P = .002), indicating a 23% loss of olfactory axons in the COVID group.

Comparing COVID patients with and without reported loss of smell, researchers found those with an altered sense of smell had significantly more severe olfactory axon pathology.

Vascular damage

Patients with COVID also had worse vascular damage. The mean microvasculopathy score (range, 1-3) was 1.907 in patients with COVID-19 and 1.405 in controls (95% CI, 0.259-0.745; P < .001).

There was no evidence of the virus in the olfactory tissue of most patients, suggesting the olfactory pathology was likely caused by vascular damage, said Dr. Ho.

What’s unique about SARS-CoV-2 is that, although it’s a respiratory virus, it’s capable of infecting endothelial cells lining vessels.

“Other respiratory viruses only attack the airways and won’t attack vessels, but vascular damage has been seen in the heart and lung in COVID patients, and our study showed the same findings in the olfactory bulb,” Dr. Ho explained.

The researchers divided patients with COVID by infection severity: mild, moderate, severe, and critical. Interestingly, those with the most severe olfactory pathology were the ones with milder infections, said Dr. Ho.

She noted other studies have reported patients with mild infection are more likely to lose the sense of smell than those with severe infection, but she’s skeptical about this finding.

“Patients with severe COVID are usually hospitalized and intubated, so it’s hard to get them to tell you whether they’ve lost smell or not; they have other more important issues to deal with like respiratory failure,” said Dr. Ho.

Advanced age is associated with neuropathologic changes, such as tau deposits, so the researchers conducted an analysis factoring in age-related brain changes. They found a COVID-19 diagnosis remained associated with increased axonal pathology, reduced axonal density, and increased vascular pathology.

“This means that the COVID patients had more severe olfactory pathology not just because they had more tau pathology,” Dr. Ho added.

New guidance for patients

Commenting for this news organization, Davangere P. Devanand, MD, professor of psychiatry and neurology and director of geriatric psychiatry, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said the findings indicate the damage from COVID in the olfactory pathway may not be reversible as was previously thought.

“This has been suggested before as a possibility, but the autopsy findings in this case series indicate clearly that there may be permanent damage,” he said.

The results highlight the need to monitor patients with COVID for a smell deficit, said Dr. Devanand.

“Assuring patients of a full recovery in smell and taste may not be sound advice, although recovery does occur in many patients,” he added.

He praised the study design, especially the blinding of raters, but noted a number of weaknesses, including the small sample size and the age and gender discrepancies between the groups.

Another possible limitation was inclusion of patients with Alzheimer’s and Lewy body pathology, said Dr. Devanand.

“These patients typically already have pathology in the olfactory pathways, which means we don’t know if it was COVID or the underlying brain pathology contributing to smell difficulties in these patients,” he said.

He noted that, unlike deceased COVID cases in the study, patients who survive COVID may not experience axonal and microvascular injury in olfactory neurons and pathways and their sense of smell may make a full return.

Dr. Devanand said he would have liked more detailed information on the clinical history and course of study participants and whether these factors affected the pathology findings.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Ho and Dr. Devanand have reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with COVID-19, especially those with an altered sense of smell, have significantly more axon and microvasculopathy damage in the brain’s olfactory tissue versus non-COVID patients. These new findings from a postmortem study may explain long-term loss of smell in some patients with the virus.

“The striking axonal pathology in some cases indicates that olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19 may be severe and permanent,” the investigators led by Cheng-Ying Ho, MD, PhD, associate professor, department of pathology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, write.

“The results show the damage caused by COVID can extend beyond the nasal cavity and involve the brain,” Dr. Ho told this news organization.

The study was published online April 11 in JAMA Neurology.

A more thorough investigation

Patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, present with a wide range of symptoms. In addition to respiratory illnesses, they may exhibit various nonrespiratory manifestations of COVID-19.

One of the most prevalent of these is olfactory dysfunction. Research shows such dysfunction, including anosmia (loss of smell), hyposmia (reduced sense of smell), and parosmia (smells that are distorted or unpleasant), affects 30%-60% of patients with COVID-19, said Dr. Ho.

However, these statistics come from research before the advent of the Omicron variant, which evidence suggests causes less smell loss in patients with COVID, she said.

Previous studies in this area mainly focused on the lining of the nasal cavity. “We wanted to go a step beyond to see how the olfactory bulb was affected by COVID infection,” said Dr. Ho.

The study included 23 deceased patients with confirmed COVID-19 ranging in age from 28 to 93 years at death (median 62 years, 60.9% men). It also included 14 controls who tested negative for COVID-19, ranging in age from 20 to 77 years (median 53.5 years, 50% men).

Researchers collected postmortem tissue from the brain, lung, and other organs and reviewed pertinent clinical information.

Most patients with COVID died of COVID pneumonia or related complications, although some died from a different cause. Some had an active COVID infection and others were “post infection, meaning they were in the recovery stage,” said Dr. Ho.

Six patients with COVID-19 and eight controls had significant brain pathology.

Compared with controls, those with COVID-19 showed significantly worse olfactory axonal damage. The mean axon pathology score (range 1-3 with 3 the worst) was 1.921 in patients with COVID-19 and 1.198 in controls (95% confidence interval, 0.444-1.002; P < .001).

The mean axon density in the lateral olfactory tract was significantly less in patients with COVID-19 than in controls (P = .002), indicating a 23% loss of olfactory axons in the COVID group.

Comparing COVID patients with and without reported loss of smell, researchers found those with an altered sense of smell had significantly more severe olfactory axon pathology.

Vascular damage

Patients with COVID also had worse vascular damage. The mean microvasculopathy score (range, 1-3) was 1.907 in patients with COVID-19 and 1.405 in controls (95% CI, 0.259-0.745; P < .001).

There was no evidence of the virus in the olfactory tissue of most patients, suggesting the olfactory pathology was likely caused by vascular damage, said Dr. Ho.

What’s unique about SARS-CoV-2 is that, although it’s a respiratory virus, it’s capable of infecting endothelial cells lining vessels.

“Other respiratory viruses only attack the airways and won’t attack vessels, but vascular damage has been seen in the heart and lung in COVID patients, and our study showed the same findings in the olfactory bulb,” Dr. Ho explained.