User login

Direct-to-Consumer Teledermatology Growth: A Review and Outlook for the Future

In recent years, direct-to-consumer (DTC) teledermatology platforms have gained popularity as telehealth business models, allowing patients to directly initiate visits with physicians and purchase medications from single platforms. A shortage of dermatologists, improved technology, drug patent expirations, and rising health care costs accelerated the growth of DTC dermatology.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic, teledermatology adoption surged due to the need to provide care while social distancing and minimizing viral exposure. These needs prompted additional federal funding and loosened regulatory provisions.2 As the userbase of these companies has grown, so have their valuations.3 Although the DTC model has attracted the attention of patients and investors, its rise provokes many questions about patients acting as consumers in health care. Indeed, DTC telemedicine offers greater autonomy and convenience for patients, but it may impact the quality of care and the nature of physician-patient relationships, perhaps making them more transactional.

Evolution of DTC in Health Care

The DTC model emphasizes individual choice and accessible health care. Although the definition has evolved, the core idea is not new.4 Over decades, pharmaceutical companies have spent billions of dollars on DTC advertising, circumventing physicians by directly reaching patients with campaigns on prescription drugs and laboratory tests and shaping public definitions of diseases.5

The DTC model of care is fundamentally different from traditional care models in that it changes the roles of the patient and physician. Whereas early telehealth models required a health care provider to initiate teleconsultations with specialists, DTC telemedicine bypasses this step (eg, the patient can consult a dermatologist without needing a primary care provider’s input first). This care can then be provided by dermatologists with whom patients may or may not have pre-established relationships.4,6

Dermatology was an early adopter of DTC telemedicine. The shortage of dermatologists in the United States created demand for increasing accessibility to dermatologic care. Additionally, the visual nature of diagnosing dermatologic disease was ideal for platforms supporting image sharing.7 Early DTC providers were primarily individual companies offering teledermatology. However, many dermatologists can now offer DTC capabilities via companies such as Amwell and Teladoc Health.8

Over the last 2 decades, start-ups such as Warby Parker (eyeglasses) and Casper (mattresses) defined the DTC industry using borrowed supply chains, cohesive branding, heavy social media marketing, and web-only retail. Scalability, lack of competition, and abundant venture capital created competition across numerous markets.9 Health care capitalized on this DTC model, creating a $700 billion market for products ranging from hearing aids to over-the-counter medications.10

Borrowing from this DTC playbook, platforms were created to offer delivery of generic prescription drugs to patients’ doorsteps. However, unlike with other products bought online, a consumer cannot simply add prescription drugs to their shopping cart and check out. In all models of American medical practice, physicians still serve as gatekeepers, providing a safeguard for patients to ensure appropriate prescription and avoid negative consequences of unnecessary drug use. This new model effectively streamlines diagnosis, prescription, and drug delivery without the patient ever having to leave home. Combining the prescribing and selling of medications (2 tasks that traditionally have been separated) potentially creates financial conflicts of interest (COIs). Additionally, high utilization of health care, including more prescriptions and visits, does not necessarily equal high quality of care. The companies stand to benefit from extra care regardless of need, and thus these models must be scrutinized for any incentives driving unnecessary care and prescriptions.

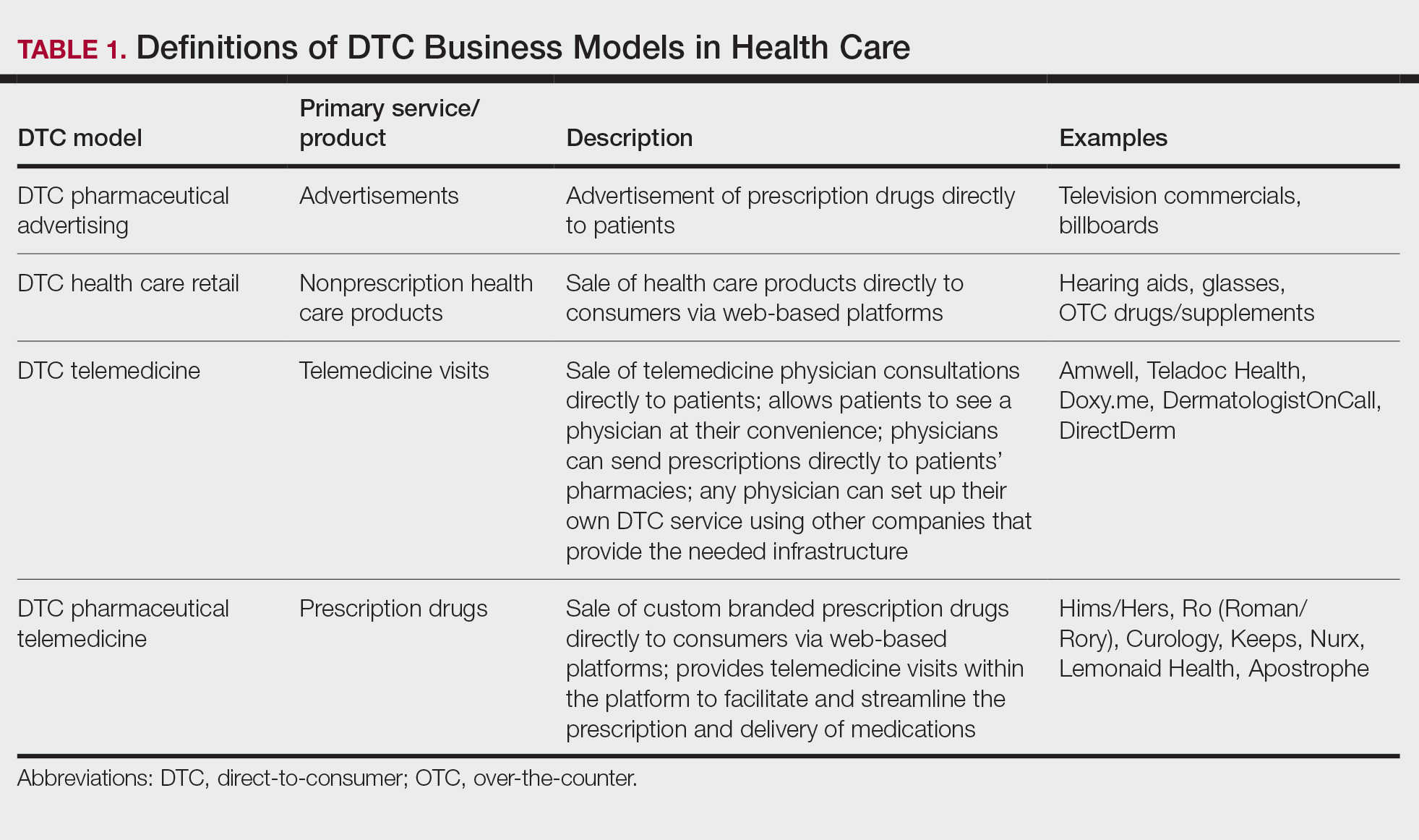

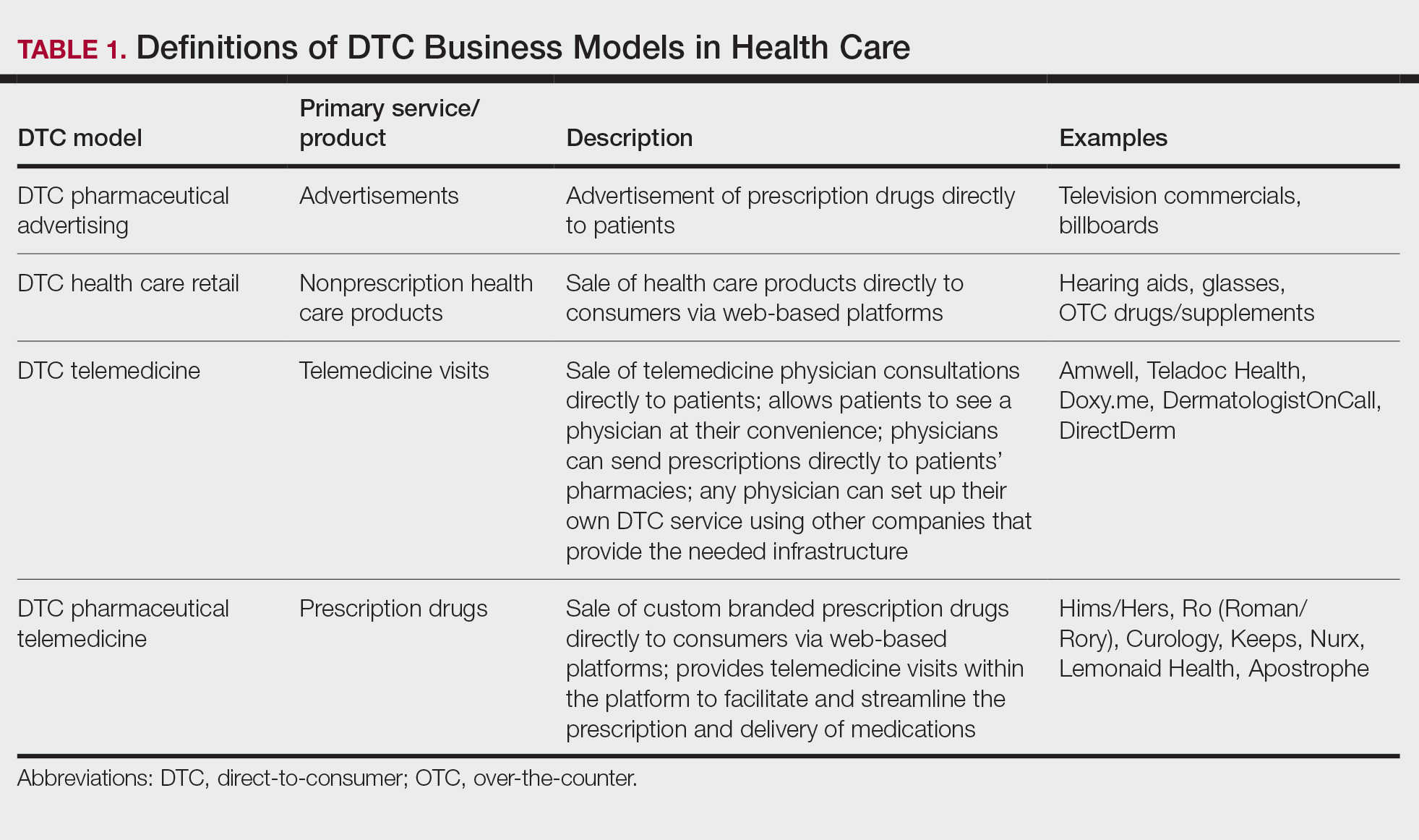

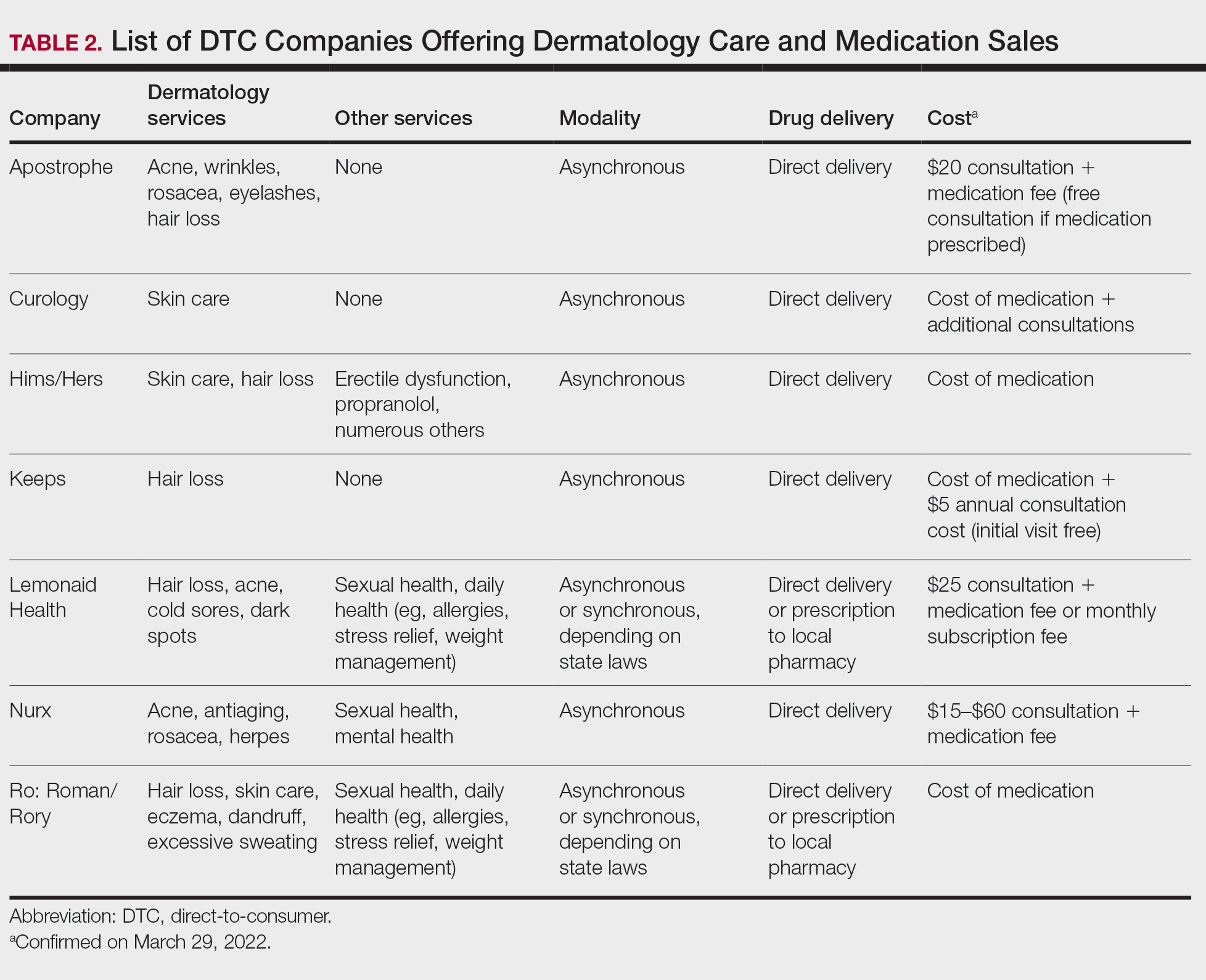

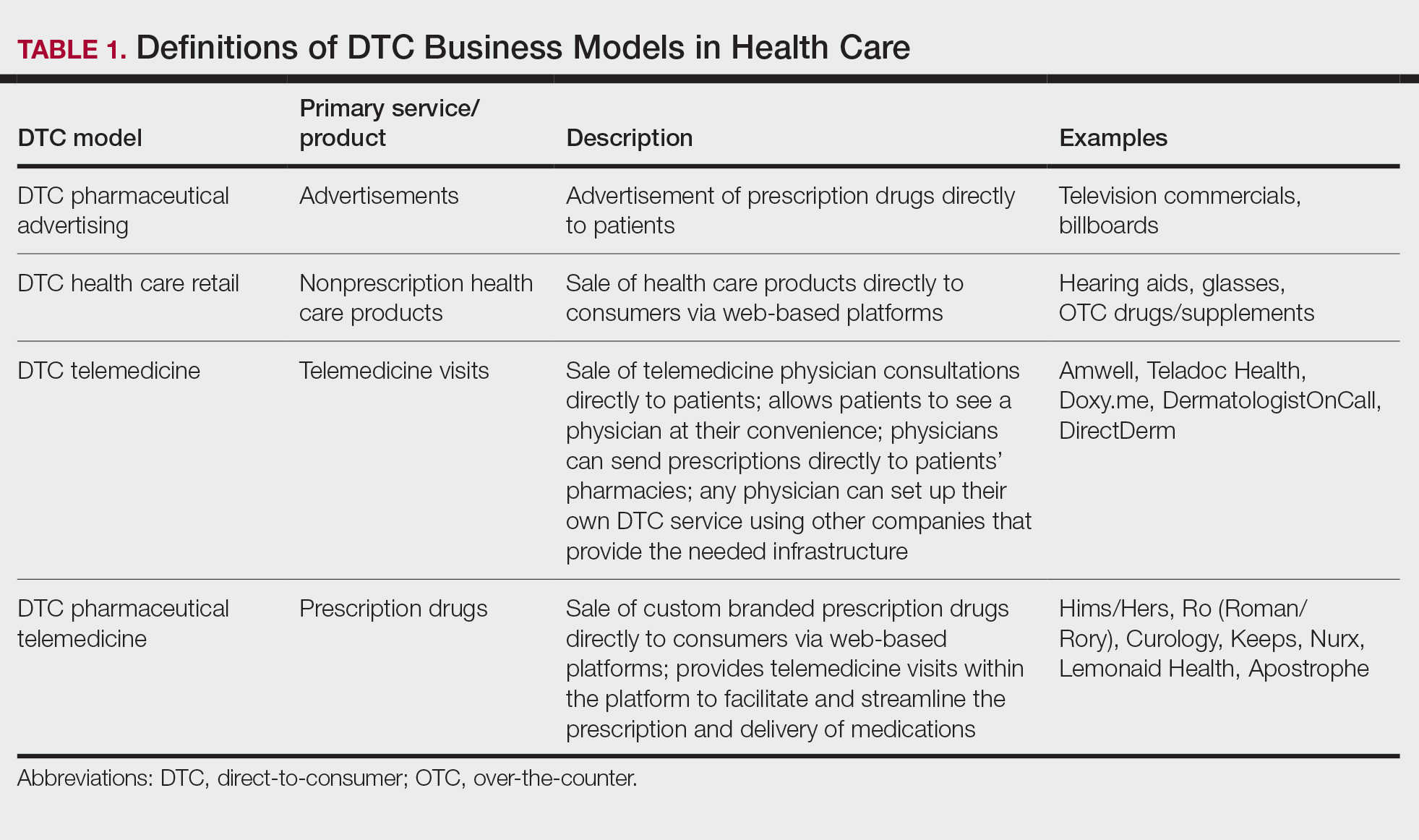

Ultimately, DTC has evolved to encompass multiple definitions in health care (Table 1). Although all models provide health care, each offers a different modality of delivery. The primary service may be the sale of prescription drugs or simply telemedicine visits. This review primarily discusses DTC pharmaceutical telemedicine platforms that sell private-label drugs and also offer telemedicine services to streamline care. However, the history, risks, and benefits discussed may apply to all models.

The DTC Landscape

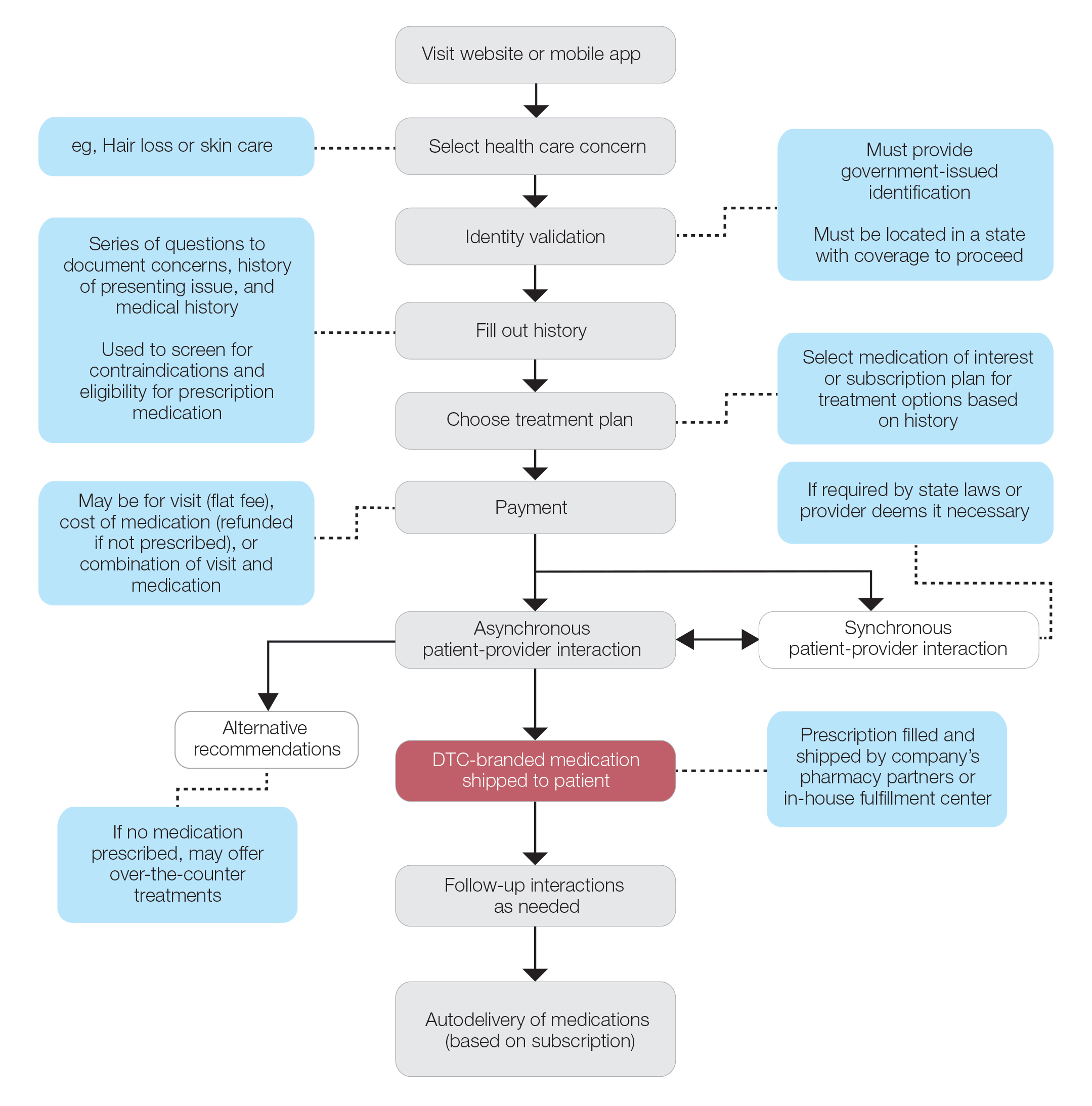

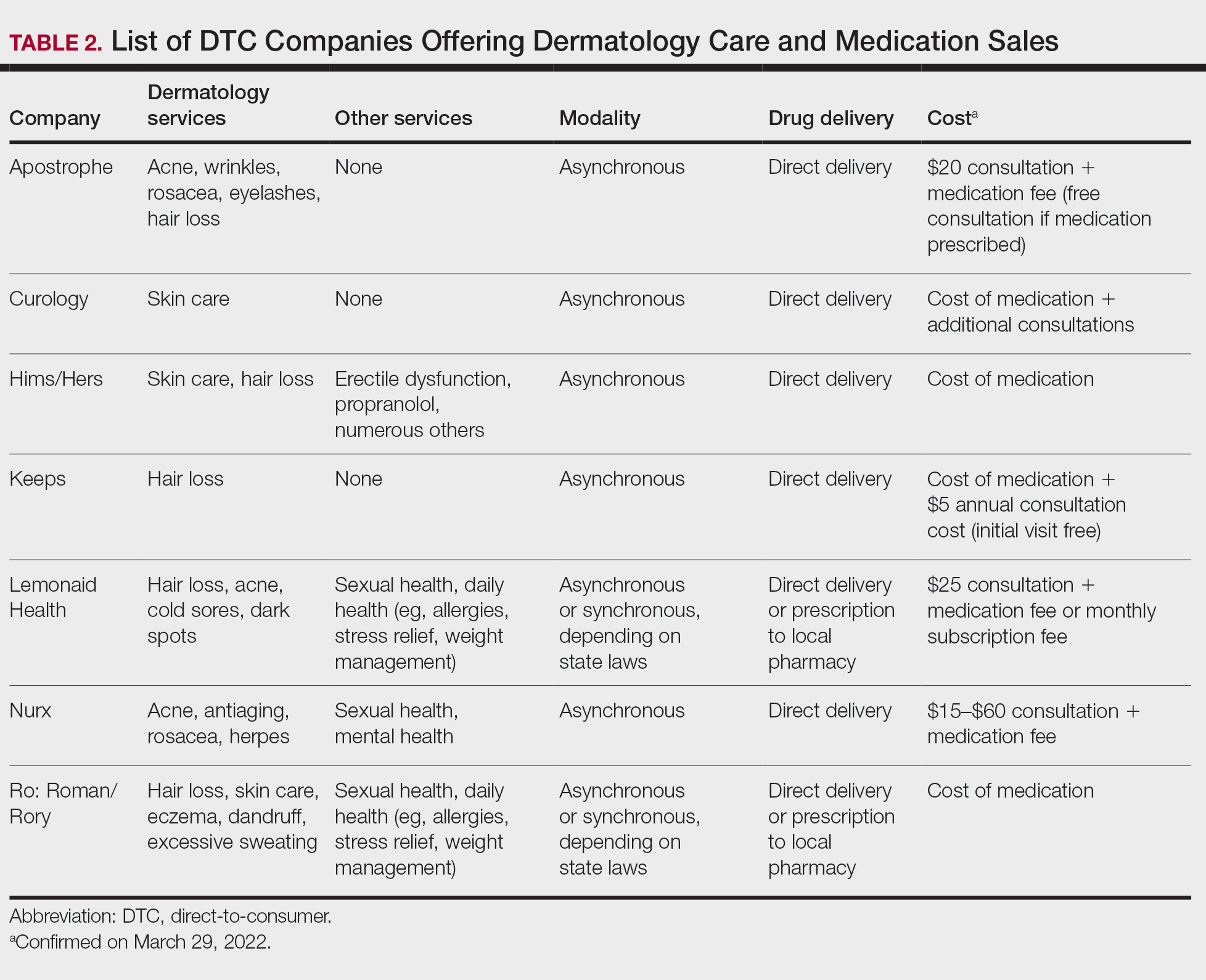

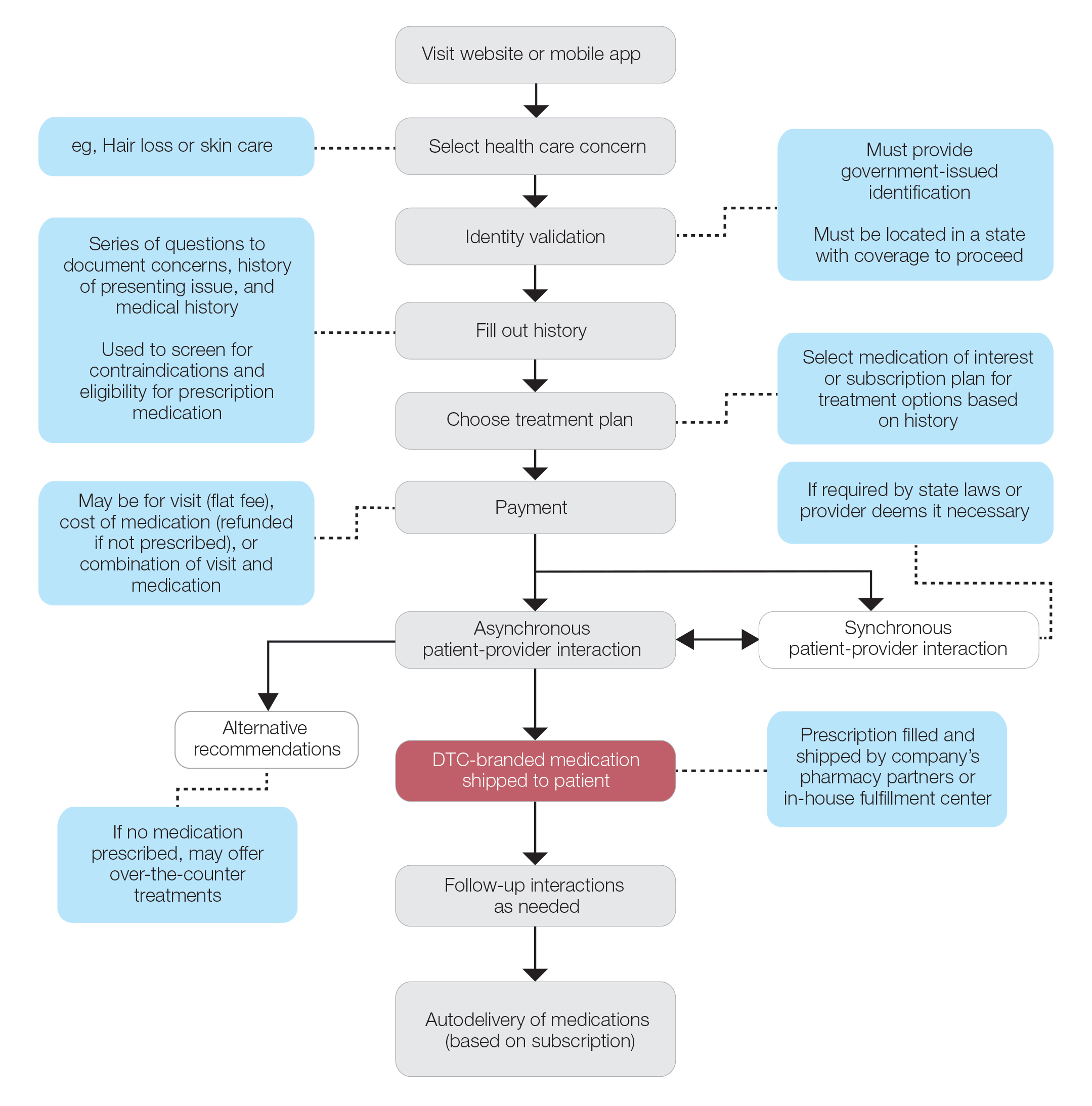

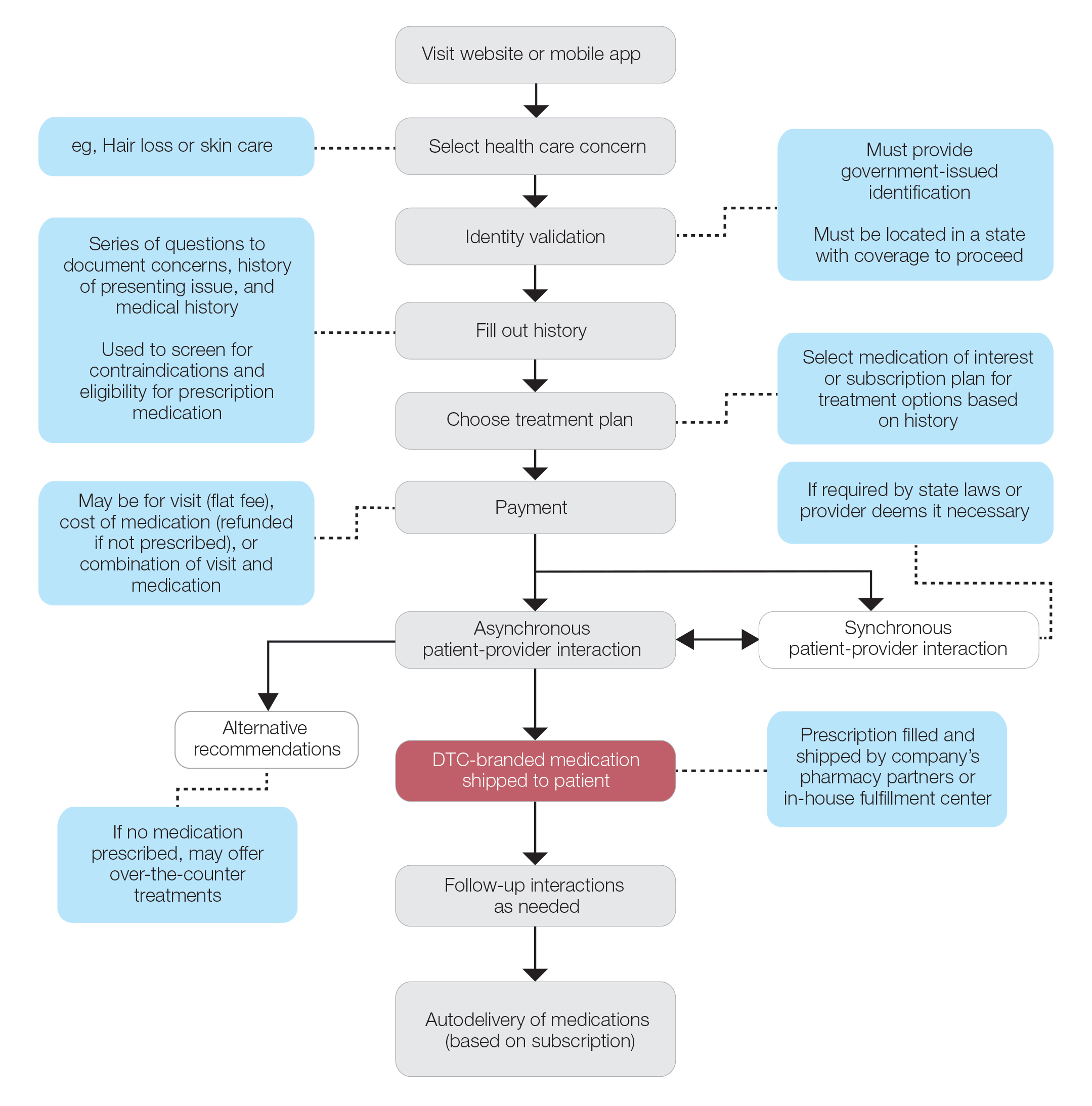

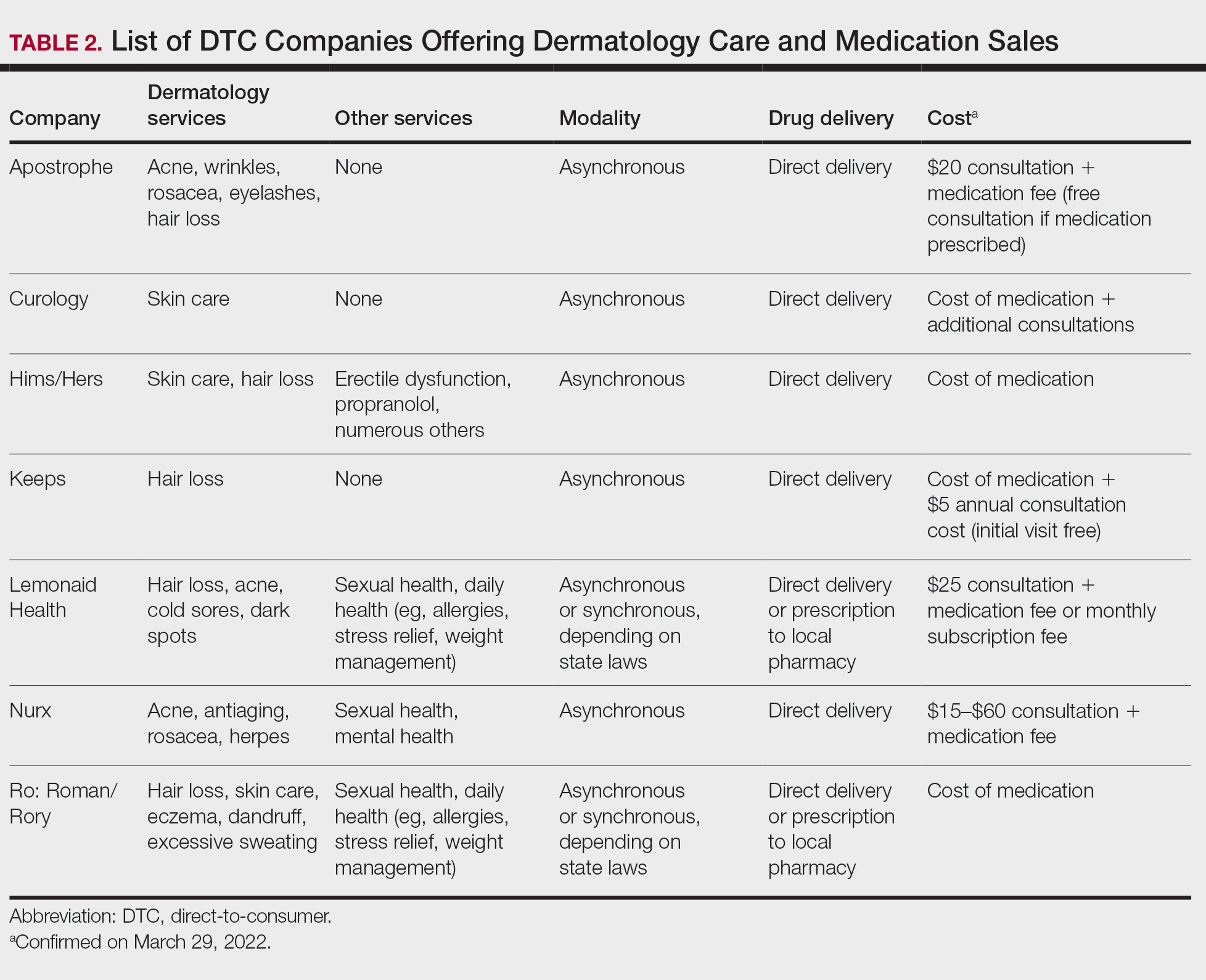

Most DTC companies employ variations on a model with the same 3 main components: a triage questionnaire, telehealth services, and prescription/drug delivery (Figure). The triage questionnaire elicits a history of the patient’s presentation and medical history. Some companies may use artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to tailor questions to patient needs. There are 2 modalities for patient-provider communication: synchronous and asynchronous. Synchronous communication entails real-time patient-physician conversations via audio only or video call. Asynchronous (or store-and-forward) communication refers to consultations provided via messaging or text-based modality, where a provider may respond to a patient within 24 hours.6 Direct-to-consumer platforms primarily use asynchronous visits (Table 2). However, some also use synchronous modalities if the provider deems it necessary or if state laws require it.

Once a provider has consulted with the patient, they can prescribe medication as needed. In certain cases, with adequate history, a prescription may be issued without a full physician visit. Furthermore, DTC companies require purchase of their custom-branded generic drugs. Prescriptions are fulfilled by the company’s pharmacy network and directly shipped to patients; few will allow patients to transfer a prescription to a pharmacy of their choice. Some platforms also sell supplements and over-the-counter medications.

Payment models vary among these companies, and most do not accept insurance (Table 2). Select models may provide free consultations and only require payment for pharmaceuticals. Others charge for consultations but reallocate payment to the cost of medication if prescribed. Another model involves flat rates for consultations and additional charges for drugs but unlimited messaging with providers for the duration of the prescription. Moreover, patients can subscribe to monthly deliveries of their medications.

Foundation of DTC

Technological advances have enabled patients to receive remote treatment from a single platform offering video calls, AI, electronic medical record interoperability, and integration of drug supply chains. Even in its simplest form, AI is increasingly used, as it allows for programs and chatbots to screen and triage patients.11 Technology also has improved at targeted mass marketing through social media platforms and search engines (eg, companies can use age, interests, location, and other parameters to target individuals likely needing acne treatment).

Drug patent expirations are a key catalyst for the rise of DTC companies, creating an attractive business model with generic drugs as the core product. Since 2008, patents for medications treating chronic conditions, such as erectile dysfunction, have expired. These patent expirations are responsible for $198 billion in projected prescription sales between 2019 and 2024.1 Thus, it follows that DTC companies have seized this opportunity to act as middlemen, taking advantage of these generic medications’ lower costs to create platforms focused on personalization and accessibility.

Rising deductibles have led patients to consider cheaper out-of-pocket alternatives that are not covered by insurance.1 For example, insurers typically do not cover finasteride treatment for conditions deemed cosmetic, such as androgenetic alopecia.12 The low cost of generic drugs creates an attractive business model for patients and investors. According to GoodRx, the average retail price for a 30-day supply of brand-name finasteride (Propecia [Merck]) is $135.92, whereas generic finasteride is $75.24.13 Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical companies offer a 30-day supply of generic finasteride ranging from $8.33 to $30.14 The average wholesale cost for retailers is an estimated $2.31 for 30 days.15 Although profit margins on generic medications may be lower, more affordable drugs increase the size of the total market. These prescriptions are available as subscription plans, resulting in recurring revenue.

Lax US pharmaceutical marketing regulations allow direct advertising to the general public.16 In 1997, the US Food and Drug Administration allowed DTC advertisements to replace summaries of serious and common adverse effects with short statements covering important risks or referrals to other sources for complete information. In 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration guidelines preventing encouragement of self-diagnosis and self-treatment were withdrawn.5 These changes enable DTC companies to launch large advertising campaigns and to accelerate customer acquisition, as the industry often describes it, with ease.

Rapid Growth and Implications

Increasing generic drug availability and improving telemedicine capabilities have the potential to reduce costs and barriers but also have the potential for financial gain. Venture capital funds have recognized this opportunity, reflected by millions of dollars of investments, and accelerated the growth of DTC health care start-ups. For example, Ro has raised $376 million from venture capital, valuing the company at $1.5 billion.3

Direct-to-consumer companies require a heavy focus on marketing campaigns for customer acquisition. Their aesthetically pleasing websites and aggressive campaigns target specific audiences based on demographics, digital use habits, and purchasing behavior.4 Some campaigns celebrate the ease of obtaining prescriptions.17 Companies have been effective in recruiting so-called millennial and Generation Z patients, known to search the internet for remedies prior to seeking physician consultations.18 Recognizing these needs, some platforms offer guides on diseases they treat, creating effective customer-acquisition funnels. Recruitment of these technology-friendly patients has proven effective, especially given the largely positive media coverage of DTC platforms––potentially serving as a surrogate for medical credibility for patients.18

Some DTC companies also market physically; skin care ads may be strategically placed in social media feeds, or even found near mirrors in public bathrooms.19 Marketing campaigns also involve disease awareness; such efforts serve to increase diagnoses and prescribed treatments while destigmatizing diseases. Although DTC companies argue this strategy empowers patients, these marketing habits have the potential to take advantage of uninformed patients. Campaigns could potentially medicalize normal experiences and expand disease definitions resulting in overdiagnosis, overtreatment, and wasted resources.5 For example, off-label propranolol use has been advertised to attract patients who might have “nerves that come creeping before an important presentation.”17 Disease awareness campaigns also may lead people to falsely believe unproven drug benefits.5 According to studies, DTC pharmaceutical advertisements are low in informational quality and result in increased patient visits and prescriptions despite cost-effective alternatives.5,20-22

Fragmentation of the health care system is another possible complication of DTC teledermatology. These companies operate as for-profit organizations separated from the rest of the health care system, raising concerns about care coordination.8 Vital health data may not be conveyed as patients move among different providers and pharmacies. One study found DTC teledermatology rarely offered to provide medical records or facilitate a referral to a local physician.23 Such a lack of communication is concerning, as medication errors are the leading cause of avoidable harm in health care.24

Direct-to-consumer care models also seemingly redefine the physician-patient relationship by turning patients into consumers. Patient interactions may seem transactional and streamlined toward sales. For these platforms, a visit often is set up as an evaluation of a patient’s suitability for a prescription, not necessarily for the best treatment modality for the problem. These companies primarily make money through the sale of prescription drugs, creating a potential COI that may undermine the patient-physician relationship. Although some companies have made it clear that medical care and pharmaceutical sales are provided by legally separate business entities and that they do not pay physicians on commission, a conflict may still exist given the financial importance of physicians prescribing medication to the success of the business.16

Even as DTC models advertise upon expanded access and choice, the companies largely prohibit patients from choosing their own pharmacy. Instead, they encourage patients to fill prescriptions with the company’s pharmacy network by claiming lower costs compared with competitors. One DTC company, Hims, is launching a prescription-fulfillment center to further consolidate their business.17,19,25 The inherent COI of issuing and fulfilling prescriptions raises concerns of patient harm.26 For example, when Dermatology.com launched as a DTC prescription skin medication shop backed by Bausch Health Companies Inc, its model included telemedicine consultation. Although consultations were provided by RxDefine, a third party, only Dermatology.com drugs were prescribed. Given the poor quality of care and obvious financial COI, an uproar in the dermatology community and advocacy by the American Academy of Dermatology led to the shutdown of Dermatology.com’s online prescription services.26

The quality of care among DTC telemedicine platforms has been equivocal. Some studies have reported equivalent care in person and online, while others have reported poor adherence to guidelines, overuse of antibiotics, and misdiagnosis.8,23 A vital portion of the DTC experience is the history questionnaire, which is geared to diagnosis and risk assessment.25 Resneck et al23 found diagnostic quality to be adequate for simple dermatologic clinical scenarios but poor for scenarios requiring more than basic histories. Although Ro has reported leveraging data from millions of interactions to ask the right questions and streamline visits, it is still unclear whether history questionnaires are adequate.17,27 Additionally, consultations may lack sufficient counseling on adverse effects, risks, or pregnancy warnings, as well as discussions on alternative treatments and preventative care.17,23 Finally, patients often are limited in their choice of dermatologist; the lack of a fully developed relationship increases concerns of follow-up and monitoring practices. Although some DTC platforms offer unlimited interactions with physicians for the duration of a prescription, it is unknown how often these services are utilized or how adequate the quality of these interactions is. This potential for lax follow-up is especially concerning for prescriptions that autorenew on a monthly basis and could result in unnecessary overtreatment.

Postpandemic and Future Outlook

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically impacted the use of telemedicine. To minimize COVID-19 transmission, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and private payers expanded telehealth coverage and eliminated reimbursement and licensing barriers.28 A decade’s worth of regulatory changes and consumer adoption was accelerated to weeks, resulting in telemedicine companies reaching record-high visit numbers.29 McKinsey & Company estimated that telehealth visit numbers surged 50- to 175-fold compared with pre–COVID-19 numbers. Additionally, 76% of patients were interested in future telehealth use, and 64% of providers were more comfortable using telehealth than before the pandemic.30 For their part, US dermatologists reported an increase in telemedicine use from 14.1% to 96.9% since COVID-19.31

Exactly how much DTC pharmaceutical telemedicine companies are growing is unclear, but private investments may be an indication. A record $14.7 billion was invested in the digital health sector in the first half of 2021; the majority went to telehealth companies.30 Ro, which reported $230 million in revenue in 2020 and has served 6 million visits, raised $200 milllion in July 2020 and $500 million in March 2021.32 Although post–COVID-19 health care will certainly involve increased telemedicine, the extent remains unclear, as telehealth vendors saw decreased usage upon reopening of state economies. Ultimately, the postpandemic regulatory landscape is hard to predict.30

Although COVID-19 appears to have caused rapid growth for DTC platforms, it also may have spurred competition. Telemedicine providers have given independent dermatologists and health care systems the infrastructure to implement custom DTC services.33 Although systems do not directly sell prescription drugs, the target market is essentially the same: patients looking for instant virtual dermatologic care. Therefore, sustained telemedicine services offered by traditional practices and systems may prove detrimental to DTC companies. However, unlike most telemedicine services, DTC models are less affected by certain changes in regulation since they do not rely on insurance. If regulations are tightened and reimbursements for telehealth are not attractive for dermatologists, teledermatology services may see an overall decrease. If so, patients who appreciate teledermatology may shift to using DTC platforms, even if their insurance does not cover them. Still, a nationwide survey found 56% of respondents felt an established relationship with a physician prior to a telemedicine visit is important, which may create a barrier for DTC adoption.34

Conclusion

Direct-to-consumer teledermatology represents a growing for-profit model of health care that provides patients with seemingly affordable and convenient care. However, there is potential for overtreatment, misdiagnosis, and fragmentation of health care. It will be important to monitor and evaluate the quality of care that DTC teledermatology offers and advocate for appropriate regulations and oversight. Eventually, more patients will have medications prescribed and dermatologic care administered through DTC companies. Dermatologists will benefit from this knowledge of DTC models to properly counsel patients on the risks and benefits of their use.

- Vennare J. The DTC healthcare report. Fitt Insider. September 15, 2019. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://insider.fitt.co/direct-to-consumer-healthcare-startups/

- Kannampallil T, Ma J. Digital translucence: adapting telemedicine delivery post-COVID-19. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26:1120-1122.

- Farr C. Ro, a 3-year-old online health provider, just raised a new round that values it at $1.5 billion. CNBC. July 27, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/27/ro-raises-200-million-at-1point5-billion-valuation-250-million-sales.html

- Elliott T, Shih J. Direct to consumer telemedicine. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;19:1.

- Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Medical marketing in the United States, 1997-2016. JAMA. 2019;321:80-96.

- Peart JM, Kovarik C. Direct-to-patient teledermatology practices. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:907-909.

- Coates SJ, Kvedar J, Granstein RD. Teledermatology: from historical perspective to emerging techniques of the modern era. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:563-574.

- Rheuban KS, Krupinski EA, eds. Understanding Telehealth. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

- Schlesinger LA, Higgins M, Roseman S. Reinventing the direct-to-consumer business model. Harvard Business Review. March 31, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://hbr.org/2020/03/reinventing-the-direct-to-consumer-business-model

- Cohen AB, Mathews SC, Dorsey ER, et al. Direct-to-consumer digital health. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2:E163-E165.

- 6 telehealth trends for 2020. Wolters Kluwer. Published January 27, 2021. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/6-telehealth-trends-for-2020

- Jadoo SA, Lipoff JB. Prescribing to save patients money: ethical considerations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:826-828.

- Propecia. GoodRx. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.goodrx.com/propecia

- Lauer A. The truth about online hair-loss treatments like Roman and Hims, according to a dermatologist. InsideHook. January 13, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.insidehook.com/article/grooming/men-hair-loss-treatments-dermatologist-review

- Friedman Y. Drug price trends for NDC 16729-0089. DrugPatentWatch. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/p/drug-price/ndc/index.php?query=16729-0089

- Curtis H, Milner J. Ethical concerns with online direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical companies. J Med Ethics. 2020;46:168-171.

- Jain T, Lu RJ, Mehrotra A. Prescriptions on demand: the growth of direct-to-consumer telemedicine companies. JAMA. 2019;322:925-926.

- Shahinyan RH, Amighi A, Carey AN, et al. Direct-to-consumer internet prescription platforms overlook crucial pathology found during traditional office evaluation of young men with erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2020;143:165-172.

- Ali M. Andrew Dudum—bold strategies that propelled Hims & Hers into unicorn status. Exit Strategy with Moiz Ali. Published April 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://open.spotify.com/episode/6DtaJxwZDjvZSJI88DTf24?si=b3FHQiUIQY62YjfRHmnJBQ

- Klara K, Kim J, Ross JS. Direct-to-consumer broadcast advertisements for pharmaceuticals: off-label promotion and adherence to FDA guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:651-658.

- Sullivan HW, Aikin KJ, Poehlman J. Communicating risk information in direct-to-consumer prescription drug television ads: a content analysis. Health Commun. 2019;34:212-219.

- Applequist J, Ball JG. An updated analysis of direct-to-consumer television advertisements for prescription drugs. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16:211-216.

- Resneck JS Jr, Abrouk M, Steuer M, et al. Choice, transparency, coordination, and quality among direct-to-consumer telemedicine websites and apps treating skin disease. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:768-775.

- Patient safety. World Health Organization. Published September 13, 2019. Accessed February 1, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety

- Bollmeier SG, Stevenson E, Finnegan P, et al. Direct to consumer telemedicine: is healthcare from home best? Mo Med. 2020;117:303-309.

26. Court E. Bausch yanked online prescribing after dermatologist backlash. Bloomberg.com. Published March 11, 2020. Accessed September 25, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-11/bausch-yanked-online-prescribing-after-dermatologist-backlash

27. Reitano Z. The future of healthcare: how Ro helps providers treat patients 2 minutes, 2 days, 2 weeks, and 2 years at a time. Medium. Published March 4, 2019. Accessed February 1, 2022. https://medium.com/ro-co/the-future-of-healthcare-how-ro-helps-providers-treat-patients-2-mins-2-days-2-weeks-and-2-10efc0679d7

28. Lee I, Kovarik C, Tejasvi T, et al. Telehealth: helping your patients and practice survive and thrive during the COVID-19 crisis with rapid quality implementation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1213-1214.

29. Pifer R. “Weeks where decades happen”: telehealth 6 months into COVID-19. Healthcare Dive. Published July 27, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/telehealth-6-months-coronavirus/581447/

30. Bestsennyy O, Gilbert G, Harris A, et al. Telehealth: a quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? McKinsey & Company. Updated July 9, 2021. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality

31. Kennedy J, Arey S, Hopkins Z, et al. Dermatologist perceptions of teledermatology implementation and future use after COVID-19: demographics, barriers, and insights. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:595-597.

32. Jennings K. Digital health startup Ro raised $500 million at $5 billion valuation. Forbes. March 22, 2021. Accessed March 29, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/katiejennings/2021/03/22/digital-health-startup-ro-raised-500-million-at-5-billion-valuation/?sh=695be0e462f5

33. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? telemedicine for COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679-1681.

34. Welch BM, Harvey J, O’Connell NS, et al. Patient preferences for direct-to-consumer telemedicine services: a nationwide survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:784.

In recent years, direct-to-consumer (DTC) teledermatology platforms have gained popularity as telehealth business models, allowing patients to directly initiate visits with physicians and purchase medications from single platforms. A shortage of dermatologists, improved technology, drug patent expirations, and rising health care costs accelerated the growth of DTC dermatology.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic, teledermatology adoption surged due to the need to provide care while social distancing and minimizing viral exposure. These needs prompted additional federal funding and loosened regulatory provisions.2 As the userbase of these companies has grown, so have their valuations.3 Although the DTC model has attracted the attention of patients and investors, its rise provokes many questions about patients acting as consumers in health care. Indeed, DTC telemedicine offers greater autonomy and convenience for patients, but it may impact the quality of care and the nature of physician-patient relationships, perhaps making them more transactional.

Evolution of DTC in Health Care

The DTC model emphasizes individual choice and accessible health care. Although the definition has evolved, the core idea is not new.4 Over decades, pharmaceutical companies have spent billions of dollars on DTC advertising, circumventing physicians by directly reaching patients with campaigns on prescription drugs and laboratory tests and shaping public definitions of diseases.5

The DTC model of care is fundamentally different from traditional care models in that it changes the roles of the patient and physician. Whereas early telehealth models required a health care provider to initiate teleconsultations with specialists, DTC telemedicine bypasses this step (eg, the patient can consult a dermatologist without needing a primary care provider’s input first). This care can then be provided by dermatologists with whom patients may or may not have pre-established relationships.4,6

Dermatology was an early adopter of DTC telemedicine. The shortage of dermatologists in the United States created demand for increasing accessibility to dermatologic care. Additionally, the visual nature of diagnosing dermatologic disease was ideal for platforms supporting image sharing.7 Early DTC providers were primarily individual companies offering teledermatology. However, many dermatologists can now offer DTC capabilities via companies such as Amwell and Teladoc Health.8

Over the last 2 decades, start-ups such as Warby Parker (eyeglasses) and Casper (mattresses) defined the DTC industry using borrowed supply chains, cohesive branding, heavy social media marketing, and web-only retail. Scalability, lack of competition, and abundant venture capital created competition across numerous markets.9 Health care capitalized on this DTC model, creating a $700 billion market for products ranging from hearing aids to over-the-counter medications.10

Borrowing from this DTC playbook, platforms were created to offer delivery of generic prescription drugs to patients’ doorsteps. However, unlike with other products bought online, a consumer cannot simply add prescription drugs to their shopping cart and check out. In all models of American medical practice, physicians still serve as gatekeepers, providing a safeguard for patients to ensure appropriate prescription and avoid negative consequences of unnecessary drug use. This new model effectively streamlines diagnosis, prescription, and drug delivery without the patient ever having to leave home. Combining the prescribing and selling of medications (2 tasks that traditionally have been separated) potentially creates financial conflicts of interest (COIs). Additionally, high utilization of health care, including more prescriptions and visits, does not necessarily equal high quality of care. The companies stand to benefit from extra care regardless of need, and thus these models must be scrutinized for any incentives driving unnecessary care and prescriptions.

Ultimately, DTC has evolved to encompass multiple definitions in health care (Table 1). Although all models provide health care, each offers a different modality of delivery. The primary service may be the sale of prescription drugs or simply telemedicine visits. This review primarily discusses DTC pharmaceutical telemedicine platforms that sell private-label drugs and also offer telemedicine services to streamline care. However, the history, risks, and benefits discussed may apply to all models.

The DTC Landscape

Most DTC companies employ variations on a model with the same 3 main components: a triage questionnaire, telehealth services, and prescription/drug delivery (Figure). The triage questionnaire elicits a history of the patient’s presentation and medical history. Some companies may use artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to tailor questions to patient needs. There are 2 modalities for patient-provider communication: synchronous and asynchronous. Synchronous communication entails real-time patient-physician conversations via audio only or video call. Asynchronous (or store-and-forward) communication refers to consultations provided via messaging or text-based modality, where a provider may respond to a patient within 24 hours.6 Direct-to-consumer platforms primarily use asynchronous visits (Table 2). However, some also use synchronous modalities if the provider deems it necessary or if state laws require it.

Once a provider has consulted with the patient, they can prescribe medication as needed. In certain cases, with adequate history, a prescription may be issued without a full physician visit. Furthermore, DTC companies require purchase of their custom-branded generic drugs. Prescriptions are fulfilled by the company’s pharmacy network and directly shipped to patients; few will allow patients to transfer a prescription to a pharmacy of their choice. Some platforms also sell supplements and over-the-counter medications.

Payment models vary among these companies, and most do not accept insurance (Table 2). Select models may provide free consultations and only require payment for pharmaceuticals. Others charge for consultations but reallocate payment to the cost of medication if prescribed. Another model involves flat rates for consultations and additional charges for drugs but unlimited messaging with providers for the duration of the prescription. Moreover, patients can subscribe to monthly deliveries of their medications.

Foundation of DTC

Technological advances have enabled patients to receive remote treatment from a single platform offering video calls, AI, electronic medical record interoperability, and integration of drug supply chains. Even in its simplest form, AI is increasingly used, as it allows for programs and chatbots to screen and triage patients.11 Technology also has improved at targeted mass marketing through social media platforms and search engines (eg, companies can use age, interests, location, and other parameters to target individuals likely needing acne treatment).

Drug patent expirations are a key catalyst for the rise of DTC companies, creating an attractive business model with generic drugs as the core product. Since 2008, patents for medications treating chronic conditions, such as erectile dysfunction, have expired. These patent expirations are responsible for $198 billion in projected prescription sales between 2019 and 2024.1 Thus, it follows that DTC companies have seized this opportunity to act as middlemen, taking advantage of these generic medications’ lower costs to create platforms focused on personalization and accessibility.

Rising deductibles have led patients to consider cheaper out-of-pocket alternatives that are not covered by insurance.1 For example, insurers typically do not cover finasteride treatment for conditions deemed cosmetic, such as androgenetic alopecia.12 The low cost of generic drugs creates an attractive business model for patients and investors. According to GoodRx, the average retail price for a 30-day supply of brand-name finasteride (Propecia [Merck]) is $135.92, whereas generic finasteride is $75.24.13 Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical companies offer a 30-day supply of generic finasteride ranging from $8.33 to $30.14 The average wholesale cost for retailers is an estimated $2.31 for 30 days.15 Although profit margins on generic medications may be lower, more affordable drugs increase the size of the total market. These prescriptions are available as subscription plans, resulting in recurring revenue.

Lax US pharmaceutical marketing regulations allow direct advertising to the general public.16 In 1997, the US Food and Drug Administration allowed DTC advertisements to replace summaries of serious and common adverse effects with short statements covering important risks or referrals to other sources for complete information. In 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration guidelines preventing encouragement of self-diagnosis and self-treatment were withdrawn.5 These changes enable DTC companies to launch large advertising campaigns and to accelerate customer acquisition, as the industry often describes it, with ease.

Rapid Growth and Implications

Increasing generic drug availability and improving telemedicine capabilities have the potential to reduce costs and barriers but also have the potential for financial gain. Venture capital funds have recognized this opportunity, reflected by millions of dollars of investments, and accelerated the growth of DTC health care start-ups. For example, Ro has raised $376 million from venture capital, valuing the company at $1.5 billion.3

Direct-to-consumer companies require a heavy focus on marketing campaigns for customer acquisition. Their aesthetically pleasing websites and aggressive campaigns target specific audiences based on demographics, digital use habits, and purchasing behavior.4 Some campaigns celebrate the ease of obtaining prescriptions.17 Companies have been effective in recruiting so-called millennial and Generation Z patients, known to search the internet for remedies prior to seeking physician consultations.18 Recognizing these needs, some platforms offer guides on diseases they treat, creating effective customer-acquisition funnels. Recruitment of these technology-friendly patients has proven effective, especially given the largely positive media coverage of DTC platforms––potentially serving as a surrogate for medical credibility for patients.18

Some DTC companies also market physically; skin care ads may be strategically placed in social media feeds, or even found near mirrors in public bathrooms.19 Marketing campaigns also involve disease awareness; such efforts serve to increase diagnoses and prescribed treatments while destigmatizing diseases. Although DTC companies argue this strategy empowers patients, these marketing habits have the potential to take advantage of uninformed patients. Campaigns could potentially medicalize normal experiences and expand disease definitions resulting in overdiagnosis, overtreatment, and wasted resources.5 For example, off-label propranolol use has been advertised to attract patients who might have “nerves that come creeping before an important presentation.”17 Disease awareness campaigns also may lead people to falsely believe unproven drug benefits.5 According to studies, DTC pharmaceutical advertisements are low in informational quality and result in increased patient visits and prescriptions despite cost-effective alternatives.5,20-22

Fragmentation of the health care system is another possible complication of DTC teledermatology. These companies operate as for-profit organizations separated from the rest of the health care system, raising concerns about care coordination.8 Vital health data may not be conveyed as patients move among different providers and pharmacies. One study found DTC teledermatology rarely offered to provide medical records or facilitate a referral to a local physician.23 Such a lack of communication is concerning, as medication errors are the leading cause of avoidable harm in health care.24

Direct-to-consumer care models also seemingly redefine the physician-patient relationship by turning patients into consumers. Patient interactions may seem transactional and streamlined toward sales. For these platforms, a visit often is set up as an evaluation of a patient’s suitability for a prescription, not necessarily for the best treatment modality for the problem. These companies primarily make money through the sale of prescription drugs, creating a potential COI that may undermine the patient-physician relationship. Although some companies have made it clear that medical care and pharmaceutical sales are provided by legally separate business entities and that they do not pay physicians on commission, a conflict may still exist given the financial importance of physicians prescribing medication to the success of the business.16

Even as DTC models advertise upon expanded access and choice, the companies largely prohibit patients from choosing their own pharmacy. Instead, they encourage patients to fill prescriptions with the company’s pharmacy network by claiming lower costs compared with competitors. One DTC company, Hims, is launching a prescription-fulfillment center to further consolidate their business.17,19,25 The inherent COI of issuing and fulfilling prescriptions raises concerns of patient harm.26 For example, when Dermatology.com launched as a DTC prescription skin medication shop backed by Bausch Health Companies Inc, its model included telemedicine consultation. Although consultations were provided by RxDefine, a third party, only Dermatology.com drugs were prescribed. Given the poor quality of care and obvious financial COI, an uproar in the dermatology community and advocacy by the American Academy of Dermatology led to the shutdown of Dermatology.com’s online prescription services.26

The quality of care among DTC telemedicine platforms has been equivocal. Some studies have reported equivalent care in person and online, while others have reported poor adherence to guidelines, overuse of antibiotics, and misdiagnosis.8,23 A vital portion of the DTC experience is the history questionnaire, which is geared to diagnosis and risk assessment.25 Resneck et al23 found diagnostic quality to be adequate for simple dermatologic clinical scenarios but poor for scenarios requiring more than basic histories. Although Ro has reported leveraging data from millions of interactions to ask the right questions and streamline visits, it is still unclear whether history questionnaires are adequate.17,27 Additionally, consultations may lack sufficient counseling on adverse effects, risks, or pregnancy warnings, as well as discussions on alternative treatments and preventative care.17,23 Finally, patients often are limited in their choice of dermatologist; the lack of a fully developed relationship increases concerns of follow-up and monitoring practices. Although some DTC platforms offer unlimited interactions with physicians for the duration of a prescription, it is unknown how often these services are utilized or how adequate the quality of these interactions is. This potential for lax follow-up is especially concerning for prescriptions that autorenew on a monthly basis and could result in unnecessary overtreatment.

Postpandemic and Future Outlook

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically impacted the use of telemedicine. To minimize COVID-19 transmission, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and private payers expanded telehealth coverage and eliminated reimbursement and licensing barriers.28 A decade’s worth of regulatory changes and consumer adoption was accelerated to weeks, resulting in telemedicine companies reaching record-high visit numbers.29 McKinsey & Company estimated that telehealth visit numbers surged 50- to 175-fold compared with pre–COVID-19 numbers. Additionally, 76% of patients were interested in future telehealth use, and 64% of providers were more comfortable using telehealth than before the pandemic.30 For their part, US dermatologists reported an increase in telemedicine use from 14.1% to 96.9% since COVID-19.31

Exactly how much DTC pharmaceutical telemedicine companies are growing is unclear, but private investments may be an indication. A record $14.7 billion was invested in the digital health sector in the first half of 2021; the majority went to telehealth companies.30 Ro, which reported $230 million in revenue in 2020 and has served 6 million visits, raised $200 milllion in July 2020 and $500 million in March 2021.32 Although post–COVID-19 health care will certainly involve increased telemedicine, the extent remains unclear, as telehealth vendors saw decreased usage upon reopening of state economies. Ultimately, the postpandemic regulatory landscape is hard to predict.30

Although COVID-19 appears to have caused rapid growth for DTC platforms, it also may have spurred competition. Telemedicine providers have given independent dermatologists and health care systems the infrastructure to implement custom DTC services.33 Although systems do not directly sell prescription drugs, the target market is essentially the same: patients looking for instant virtual dermatologic care. Therefore, sustained telemedicine services offered by traditional practices and systems may prove detrimental to DTC companies. However, unlike most telemedicine services, DTC models are less affected by certain changes in regulation since they do not rely on insurance. If regulations are tightened and reimbursements for telehealth are not attractive for dermatologists, teledermatology services may see an overall decrease. If so, patients who appreciate teledermatology may shift to using DTC platforms, even if their insurance does not cover them. Still, a nationwide survey found 56% of respondents felt an established relationship with a physician prior to a telemedicine visit is important, which may create a barrier for DTC adoption.34

Conclusion

Direct-to-consumer teledermatology represents a growing for-profit model of health care that provides patients with seemingly affordable and convenient care. However, there is potential for overtreatment, misdiagnosis, and fragmentation of health care. It will be important to monitor and evaluate the quality of care that DTC teledermatology offers and advocate for appropriate regulations and oversight. Eventually, more patients will have medications prescribed and dermatologic care administered through DTC companies. Dermatologists will benefit from this knowledge of DTC models to properly counsel patients on the risks and benefits of their use.

In recent years, direct-to-consumer (DTC) teledermatology platforms have gained popularity as telehealth business models, allowing patients to directly initiate visits with physicians and purchase medications from single platforms. A shortage of dermatologists, improved technology, drug patent expirations, and rising health care costs accelerated the growth of DTC dermatology.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic, teledermatology adoption surged due to the need to provide care while social distancing and minimizing viral exposure. These needs prompted additional federal funding and loosened regulatory provisions.2 As the userbase of these companies has grown, so have their valuations.3 Although the DTC model has attracted the attention of patients and investors, its rise provokes many questions about patients acting as consumers in health care. Indeed, DTC telemedicine offers greater autonomy and convenience for patients, but it may impact the quality of care and the nature of physician-patient relationships, perhaps making them more transactional.

Evolution of DTC in Health Care

The DTC model emphasizes individual choice and accessible health care. Although the definition has evolved, the core idea is not new.4 Over decades, pharmaceutical companies have spent billions of dollars on DTC advertising, circumventing physicians by directly reaching patients with campaigns on prescription drugs and laboratory tests and shaping public definitions of diseases.5

The DTC model of care is fundamentally different from traditional care models in that it changes the roles of the patient and physician. Whereas early telehealth models required a health care provider to initiate teleconsultations with specialists, DTC telemedicine bypasses this step (eg, the patient can consult a dermatologist without needing a primary care provider’s input first). This care can then be provided by dermatologists with whom patients may or may not have pre-established relationships.4,6

Dermatology was an early adopter of DTC telemedicine. The shortage of dermatologists in the United States created demand for increasing accessibility to dermatologic care. Additionally, the visual nature of diagnosing dermatologic disease was ideal for platforms supporting image sharing.7 Early DTC providers were primarily individual companies offering teledermatology. However, many dermatologists can now offer DTC capabilities via companies such as Amwell and Teladoc Health.8

Over the last 2 decades, start-ups such as Warby Parker (eyeglasses) and Casper (mattresses) defined the DTC industry using borrowed supply chains, cohesive branding, heavy social media marketing, and web-only retail. Scalability, lack of competition, and abundant venture capital created competition across numerous markets.9 Health care capitalized on this DTC model, creating a $700 billion market for products ranging from hearing aids to over-the-counter medications.10

Borrowing from this DTC playbook, platforms were created to offer delivery of generic prescription drugs to patients’ doorsteps. However, unlike with other products bought online, a consumer cannot simply add prescription drugs to their shopping cart and check out. In all models of American medical practice, physicians still serve as gatekeepers, providing a safeguard for patients to ensure appropriate prescription and avoid negative consequences of unnecessary drug use. This new model effectively streamlines diagnosis, prescription, and drug delivery without the patient ever having to leave home. Combining the prescribing and selling of medications (2 tasks that traditionally have been separated) potentially creates financial conflicts of interest (COIs). Additionally, high utilization of health care, including more prescriptions and visits, does not necessarily equal high quality of care. The companies stand to benefit from extra care regardless of need, and thus these models must be scrutinized for any incentives driving unnecessary care and prescriptions.

Ultimately, DTC has evolved to encompass multiple definitions in health care (Table 1). Although all models provide health care, each offers a different modality of delivery. The primary service may be the sale of prescription drugs or simply telemedicine visits. This review primarily discusses DTC pharmaceutical telemedicine platforms that sell private-label drugs and also offer telemedicine services to streamline care. However, the history, risks, and benefits discussed may apply to all models.

The DTC Landscape

Most DTC companies employ variations on a model with the same 3 main components: a triage questionnaire, telehealth services, and prescription/drug delivery (Figure). The triage questionnaire elicits a history of the patient’s presentation and medical history. Some companies may use artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to tailor questions to patient needs. There are 2 modalities for patient-provider communication: synchronous and asynchronous. Synchronous communication entails real-time patient-physician conversations via audio only or video call. Asynchronous (or store-and-forward) communication refers to consultations provided via messaging or text-based modality, where a provider may respond to a patient within 24 hours.6 Direct-to-consumer platforms primarily use asynchronous visits (Table 2). However, some also use synchronous modalities if the provider deems it necessary or if state laws require it.

Once a provider has consulted with the patient, they can prescribe medication as needed. In certain cases, with adequate history, a prescription may be issued without a full physician visit. Furthermore, DTC companies require purchase of their custom-branded generic drugs. Prescriptions are fulfilled by the company’s pharmacy network and directly shipped to patients; few will allow patients to transfer a prescription to a pharmacy of their choice. Some platforms also sell supplements and over-the-counter medications.

Payment models vary among these companies, and most do not accept insurance (Table 2). Select models may provide free consultations and only require payment for pharmaceuticals. Others charge for consultations but reallocate payment to the cost of medication if prescribed. Another model involves flat rates for consultations and additional charges for drugs but unlimited messaging with providers for the duration of the prescription. Moreover, patients can subscribe to monthly deliveries of their medications.

Foundation of DTC

Technological advances have enabled patients to receive remote treatment from a single platform offering video calls, AI, electronic medical record interoperability, and integration of drug supply chains. Even in its simplest form, AI is increasingly used, as it allows for programs and chatbots to screen and triage patients.11 Technology also has improved at targeted mass marketing through social media platforms and search engines (eg, companies can use age, interests, location, and other parameters to target individuals likely needing acne treatment).

Drug patent expirations are a key catalyst for the rise of DTC companies, creating an attractive business model with generic drugs as the core product. Since 2008, patents for medications treating chronic conditions, such as erectile dysfunction, have expired. These patent expirations are responsible for $198 billion in projected prescription sales between 2019 and 2024.1 Thus, it follows that DTC companies have seized this opportunity to act as middlemen, taking advantage of these generic medications’ lower costs to create platforms focused on personalization and accessibility.

Rising deductibles have led patients to consider cheaper out-of-pocket alternatives that are not covered by insurance.1 For example, insurers typically do not cover finasteride treatment for conditions deemed cosmetic, such as androgenetic alopecia.12 The low cost of generic drugs creates an attractive business model for patients and investors. According to GoodRx, the average retail price for a 30-day supply of brand-name finasteride (Propecia [Merck]) is $135.92, whereas generic finasteride is $75.24.13 Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical companies offer a 30-day supply of generic finasteride ranging from $8.33 to $30.14 The average wholesale cost for retailers is an estimated $2.31 for 30 days.15 Although profit margins on generic medications may be lower, more affordable drugs increase the size of the total market. These prescriptions are available as subscription plans, resulting in recurring revenue.

Lax US pharmaceutical marketing regulations allow direct advertising to the general public.16 In 1997, the US Food and Drug Administration allowed DTC advertisements to replace summaries of serious and common adverse effects with short statements covering important risks or referrals to other sources for complete information. In 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration guidelines preventing encouragement of self-diagnosis and self-treatment were withdrawn.5 These changes enable DTC companies to launch large advertising campaigns and to accelerate customer acquisition, as the industry often describes it, with ease.

Rapid Growth and Implications

Increasing generic drug availability and improving telemedicine capabilities have the potential to reduce costs and barriers but also have the potential for financial gain. Venture capital funds have recognized this opportunity, reflected by millions of dollars of investments, and accelerated the growth of DTC health care start-ups. For example, Ro has raised $376 million from venture capital, valuing the company at $1.5 billion.3

Direct-to-consumer companies require a heavy focus on marketing campaigns for customer acquisition. Their aesthetically pleasing websites and aggressive campaigns target specific audiences based on demographics, digital use habits, and purchasing behavior.4 Some campaigns celebrate the ease of obtaining prescriptions.17 Companies have been effective in recruiting so-called millennial and Generation Z patients, known to search the internet for remedies prior to seeking physician consultations.18 Recognizing these needs, some platforms offer guides on diseases they treat, creating effective customer-acquisition funnels. Recruitment of these technology-friendly patients has proven effective, especially given the largely positive media coverage of DTC platforms––potentially serving as a surrogate for medical credibility for patients.18

Some DTC companies also market physically; skin care ads may be strategically placed in social media feeds, or even found near mirrors in public bathrooms.19 Marketing campaigns also involve disease awareness; such efforts serve to increase diagnoses and prescribed treatments while destigmatizing diseases. Although DTC companies argue this strategy empowers patients, these marketing habits have the potential to take advantage of uninformed patients. Campaigns could potentially medicalize normal experiences and expand disease definitions resulting in overdiagnosis, overtreatment, and wasted resources.5 For example, off-label propranolol use has been advertised to attract patients who might have “nerves that come creeping before an important presentation.”17 Disease awareness campaigns also may lead people to falsely believe unproven drug benefits.5 According to studies, DTC pharmaceutical advertisements are low in informational quality and result in increased patient visits and prescriptions despite cost-effective alternatives.5,20-22

Fragmentation of the health care system is another possible complication of DTC teledermatology. These companies operate as for-profit organizations separated from the rest of the health care system, raising concerns about care coordination.8 Vital health data may not be conveyed as patients move among different providers and pharmacies. One study found DTC teledermatology rarely offered to provide medical records or facilitate a referral to a local physician.23 Such a lack of communication is concerning, as medication errors are the leading cause of avoidable harm in health care.24

Direct-to-consumer care models also seemingly redefine the physician-patient relationship by turning patients into consumers. Patient interactions may seem transactional and streamlined toward sales. For these platforms, a visit often is set up as an evaluation of a patient’s suitability for a prescription, not necessarily for the best treatment modality for the problem. These companies primarily make money through the sale of prescription drugs, creating a potential COI that may undermine the patient-physician relationship. Although some companies have made it clear that medical care and pharmaceutical sales are provided by legally separate business entities and that they do not pay physicians on commission, a conflict may still exist given the financial importance of physicians prescribing medication to the success of the business.16

Even as DTC models advertise upon expanded access and choice, the companies largely prohibit patients from choosing their own pharmacy. Instead, they encourage patients to fill prescriptions with the company’s pharmacy network by claiming lower costs compared with competitors. One DTC company, Hims, is launching a prescription-fulfillment center to further consolidate their business.17,19,25 The inherent COI of issuing and fulfilling prescriptions raises concerns of patient harm.26 For example, when Dermatology.com launched as a DTC prescription skin medication shop backed by Bausch Health Companies Inc, its model included telemedicine consultation. Although consultations were provided by RxDefine, a third party, only Dermatology.com drugs were prescribed. Given the poor quality of care and obvious financial COI, an uproar in the dermatology community and advocacy by the American Academy of Dermatology led to the shutdown of Dermatology.com’s online prescription services.26

The quality of care among DTC telemedicine platforms has been equivocal. Some studies have reported equivalent care in person and online, while others have reported poor adherence to guidelines, overuse of antibiotics, and misdiagnosis.8,23 A vital portion of the DTC experience is the history questionnaire, which is geared to diagnosis and risk assessment.25 Resneck et al23 found diagnostic quality to be adequate for simple dermatologic clinical scenarios but poor for scenarios requiring more than basic histories. Although Ro has reported leveraging data from millions of interactions to ask the right questions and streamline visits, it is still unclear whether history questionnaires are adequate.17,27 Additionally, consultations may lack sufficient counseling on adverse effects, risks, or pregnancy warnings, as well as discussions on alternative treatments and preventative care.17,23 Finally, patients often are limited in their choice of dermatologist; the lack of a fully developed relationship increases concerns of follow-up and monitoring practices. Although some DTC platforms offer unlimited interactions with physicians for the duration of a prescription, it is unknown how often these services are utilized or how adequate the quality of these interactions is. This potential for lax follow-up is especially concerning for prescriptions that autorenew on a monthly basis and could result in unnecessary overtreatment.

Postpandemic and Future Outlook

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically impacted the use of telemedicine. To minimize COVID-19 transmission, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and private payers expanded telehealth coverage and eliminated reimbursement and licensing barriers.28 A decade’s worth of regulatory changes and consumer adoption was accelerated to weeks, resulting in telemedicine companies reaching record-high visit numbers.29 McKinsey & Company estimated that telehealth visit numbers surged 50- to 175-fold compared with pre–COVID-19 numbers. Additionally, 76% of patients were interested in future telehealth use, and 64% of providers were more comfortable using telehealth than before the pandemic.30 For their part, US dermatologists reported an increase in telemedicine use from 14.1% to 96.9% since COVID-19.31

Exactly how much DTC pharmaceutical telemedicine companies are growing is unclear, but private investments may be an indication. A record $14.7 billion was invested in the digital health sector in the first half of 2021; the majority went to telehealth companies.30 Ro, which reported $230 million in revenue in 2020 and has served 6 million visits, raised $200 milllion in July 2020 and $500 million in March 2021.32 Although post–COVID-19 health care will certainly involve increased telemedicine, the extent remains unclear, as telehealth vendors saw decreased usage upon reopening of state economies. Ultimately, the postpandemic regulatory landscape is hard to predict.30

Although COVID-19 appears to have caused rapid growth for DTC platforms, it also may have spurred competition. Telemedicine providers have given independent dermatologists and health care systems the infrastructure to implement custom DTC services.33 Although systems do not directly sell prescription drugs, the target market is essentially the same: patients looking for instant virtual dermatologic care. Therefore, sustained telemedicine services offered by traditional practices and systems may prove detrimental to DTC companies. However, unlike most telemedicine services, DTC models are less affected by certain changes in regulation since they do not rely on insurance. If regulations are tightened and reimbursements for telehealth are not attractive for dermatologists, teledermatology services may see an overall decrease. If so, patients who appreciate teledermatology may shift to using DTC platforms, even if their insurance does not cover them. Still, a nationwide survey found 56% of respondents felt an established relationship with a physician prior to a telemedicine visit is important, which may create a barrier for DTC adoption.34

Conclusion

Direct-to-consumer teledermatology represents a growing for-profit model of health care that provides patients with seemingly affordable and convenient care. However, there is potential for overtreatment, misdiagnosis, and fragmentation of health care. It will be important to monitor and evaluate the quality of care that DTC teledermatology offers and advocate for appropriate regulations and oversight. Eventually, more patients will have medications prescribed and dermatologic care administered through DTC companies. Dermatologists will benefit from this knowledge of DTC models to properly counsel patients on the risks and benefits of their use.

- Vennare J. The DTC healthcare report. Fitt Insider. September 15, 2019. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://insider.fitt.co/direct-to-consumer-healthcare-startups/

- Kannampallil T, Ma J. Digital translucence: adapting telemedicine delivery post-COVID-19. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26:1120-1122.

- Farr C. Ro, a 3-year-old online health provider, just raised a new round that values it at $1.5 billion. CNBC. July 27, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/27/ro-raises-200-million-at-1point5-billion-valuation-250-million-sales.html

- Elliott T, Shih J. Direct to consumer telemedicine. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;19:1.

- Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Medical marketing in the United States, 1997-2016. JAMA. 2019;321:80-96.

- Peart JM, Kovarik C. Direct-to-patient teledermatology practices. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:907-909.

- Coates SJ, Kvedar J, Granstein RD. Teledermatology: from historical perspective to emerging techniques of the modern era. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:563-574.

- Rheuban KS, Krupinski EA, eds. Understanding Telehealth. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

- Schlesinger LA, Higgins M, Roseman S. Reinventing the direct-to-consumer business model. Harvard Business Review. March 31, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://hbr.org/2020/03/reinventing-the-direct-to-consumer-business-model

- Cohen AB, Mathews SC, Dorsey ER, et al. Direct-to-consumer digital health. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2:E163-E165.

- 6 telehealth trends for 2020. Wolters Kluwer. Published January 27, 2021. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/6-telehealth-trends-for-2020

- Jadoo SA, Lipoff JB. Prescribing to save patients money: ethical considerations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:826-828.

- Propecia. GoodRx. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.goodrx.com/propecia

- Lauer A. The truth about online hair-loss treatments like Roman and Hims, according to a dermatologist. InsideHook. January 13, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.insidehook.com/article/grooming/men-hair-loss-treatments-dermatologist-review

- Friedman Y. Drug price trends for NDC 16729-0089. DrugPatentWatch. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/p/drug-price/ndc/index.php?query=16729-0089

- Curtis H, Milner J. Ethical concerns with online direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical companies. J Med Ethics. 2020;46:168-171.

- Jain T, Lu RJ, Mehrotra A. Prescriptions on demand: the growth of direct-to-consumer telemedicine companies. JAMA. 2019;322:925-926.

- Shahinyan RH, Amighi A, Carey AN, et al. Direct-to-consumer internet prescription platforms overlook crucial pathology found during traditional office evaluation of young men with erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2020;143:165-172.

- Ali M. Andrew Dudum—bold strategies that propelled Hims & Hers into unicorn status. Exit Strategy with Moiz Ali. Published April 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://open.spotify.com/episode/6DtaJxwZDjvZSJI88DTf24?si=b3FHQiUIQY62YjfRHmnJBQ

- Klara K, Kim J, Ross JS. Direct-to-consumer broadcast advertisements for pharmaceuticals: off-label promotion and adherence to FDA guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:651-658.

- Sullivan HW, Aikin KJ, Poehlman J. Communicating risk information in direct-to-consumer prescription drug television ads: a content analysis. Health Commun. 2019;34:212-219.

- Applequist J, Ball JG. An updated analysis of direct-to-consumer television advertisements for prescription drugs. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16:211-216.

- Resneck JS Jr, Abrouk M, Steuer M, et al. Choice, transparency, coordination, and quality among direct-to-consumer telemedicine websites and apps treating skin disease. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:768-775.

- Patient safety. World Health Organization. Published September 13, 2019. Accessed February 1, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety

- Bollmeier SG, Stevenson E, Finnegan P, et al. Direct to consumer telemedicine: is healthcare from home best? Mo Med. 2020;117:303-309.

26. Court E. Bausch yanked online prescribing after dermatologist backlash. Bloomberg.com. Published March 11, 2020. Accessed September 25, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-11/bausch-yanked-online-prescribing-after-dermatologist-backlash

27. Reitano Z. The future of healthcare: how Ro helps providers treat patients 2 minutes, 2 days, 2 weeks, and 2 years at a time. Medium. Published March 4, 2019. Accessed February 1, 2022. https://medium.com/ro-co/the-future-of-healthcare-how-ro-helps-providers-treat-patients-2-mins-2-days-2-weeks-and-2-10efc0679d7

28. Lee I, Kovarik C, Tejasvi T, et al. Telehealth: helping your patients and practice survive and thrive during the COVID-19 crisis with rapid quality implementation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1213-1214.

29. Pifer R. “Weeks where decades happen”: telehealth 6 months into COVID-19. Healthcare Dive. Published July 27, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/telehealth-6-months-coronavirus/581447/

30. Bestsennyy O, Gilbert G, Harris A, et al. Telehealth: a quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? McKinsey & Company. Updated July 9, 2021. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality

31. Kennedy J, Arey S, Hopkins Z, et al. Dermatologist perceptions of teledermatology implementation and future use after COVID-19: demographics, barriers, and insights. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:595-597.

32. Jennings K. Digital health startup Ro raised $500 million at $5 billion valuation. Forbes. March 22, 2021. Accessed March 29, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/katiejennings/2021/03/22/digital-health-startup-ro-raised-500-million-at-5-billion-valuation/?sh=695be0e462f5

33. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? telemedicine for COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679-1681.

34. Welch BM, Harvey J, O’Connell NS, et al. Patient preferences for direct-to-consumer telemedicine services: a nationwide survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:784.

- Vennare J. The DTC healthcare report. Fitt Insider. September 15, 2019. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://insider.fitt.co/direct-to-consumer-healthcare-startups/

- Kannampallil T, Ma J. Digital translucence: adapting telemedicine delivery post-COVID-19. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26:1120-1122.

- Farr C. Ro, a 3-year-old online health provider, just raised a new round that values it at $1.5 billion. CNBC. July 27, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/27/ro-raises-200-million-at-1point5-billion-valuation-250-million-sales.html

- Elliott T, Shih J. Direct to consumer telemedicine. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;19:1.

- Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Medical marketing in the United States, 1997-2016. JAMA. 2019;321:80-96.

- Peart JM, Kovarik C. Direct-to-patient teledermatology practices. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:907-909.

- Coates SJ, Kvedar J, Granstein RD. Teledermatology: from historical perspective to emerging techniques of the modern era. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:563-574.

- Rheuban KS, Krupinski EA, eds. Understanding Telehealth. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

- Schlesinger LA, Higgins M, Roseman S. Reinventing the direct-to-consumer business model. Harvard Business Review. March 31, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://hbr.org/2020/03/reinventing-the-direct-to-consumer-business-model

- Cohen AB, Mathews SC, Dorsey ER, et al. Direct-to-consumer digital health. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2:E163-E165.

- 6 telehealth trends for 2020. Wolters Kluwer. Published January 27, 2021. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/6-telehealth-trends-for-2020

- Jadoo SA, Lipoff JB. Prescribing to save patients money: ethical considerations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:826-828.

- Propecia. GoodRx. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.goodrx.com/propecia

- Lauer A. The truth about online hair-loss treatments like Roman and Hims, according to a dermatologist. InsideHook. January 13, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.insidehook.com/article/grooming/men-hair-loss-treatments-dermatologist-review

- Friedman Y. Drug price trends for NDC 16729-0089. DrugPatentWatch. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/p/drug-price/ndc/index.php?query=16729-0089

- Curtis H, Milner J. Ethical concerns with online direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical companies. J Med Ethics. 2020;46:168-171.

- Jain T, Lu RJ, Mehrotra A. Prescriptions on demand: the growth of direct-to-consumer telemedicine companies. JAMA. 2019;322:925-926.

- Shahinyan RH, Amighi A, Carey AN, et al. Direct-to-consumer internet prescription platforms overlook crucial pathology found during traditional office evaluation of young men with erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2020;143:165-172.

- Ali M. Andrew Dudum—bold strategies that propelled Hims & Hers into unicorn status. Exit Strategy with Moiz Ali. Published April 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://open.spotify.com/episode/6DtaJxwZDjvZSJI88DTf24?si=b3FHQiUIQY62YjfRHmnJBQ

- Klara K, Kim J, Ross JS. Direct-to-consumer broadcast advertisements for pharmaceuticals: off-label promotion and adherence to FDA guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:651-658.

- Sullivan HW, Aikin KJ, Poehlman J. Communicating risk information in direct-to-consumer prescription drug television ads: a content analysis. Health Commun. 2019;34:212-219.

- Applequist J, Ball JG. An updated analysis of direct-to-consumer television advertisements for prescription drugs. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16:211-216.

- Resneck JS Jr, Abrouk M, Steuer M, et al. Choice, transparency, coordination, and quality among direct-to-consumer telemedicine websites and apps treating skin disease. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:768-775.

- Patient safety. World Health Organization. Published September 13, 2019. Accessed February 1, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety

- Bollmeier SG, Stevenson E, Finnegan P, et al. Direct to consumer telemedicine: is healthcare from home best? Mo Med. 2020;117:303-309.

26. Court E. Bausch yanked online prescribing after dermatologist backlash. Bloomberg.com. Published March 11, 2020. Accessed September 25, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-11/bausch-yanked-online-prescribing-after-dermatologist-backlash

27. Reitano Z. The future of healthcare: how Ro helps providers treat patients 2 minutes, 2 days, 2 weeks, and 2 years at a time. Medium. Published March 4, 2019. Accessed February 1, 2022. https://medium.com/ro-co/the-future-of-healthcare-how-ro-helps-providers-treat-patients-2-mins-2-days-2-weeks-and-2-10efc0679d7

28. Lee I, Kovarik C, Tejasvi T, et al. Telehealth: helping your patients and practice survive and thrive during the COVID-19 crisis with rapid quality implementation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1213-1214.

29. Pifer R. “Weeks where decades happen”: telehealth 6 months into COVID-19. Healthcare Dive. Published July 27, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/telehealth-6-months-coronavirus/581447/

30. Bestsennyy O, Gilbert G, Harris A, et al. Telehealth: a quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? McKinsey & Company. Updated July 9, 2021. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality

31. Kennedy J, Arey S, Hopkins Z, et al. Dermatologist perceptions of teledermatology implementation and future use after COVID-19: demographics, barriers, and insights. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:595-597.

32. Jennings K. Digital health startup Ro raised $500 million at $5 billion valuation. Forbes. March 22, 2021. Accessed March 29, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/katiejennings/2021/03/22/digital-health-startup-ro-raised-500-million-at-5-billion-valuation/?sh=695be0e462f5

33. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? telemedicine for COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679-1681.

34. Welch BM, Harvey J, O’Connell NS, et al. Patient preferences for direct-to-consumer telemedicine services: a nationwide survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:784.

Practice Points

- Direct-to-consumer (DTC) teledermatology platforms are for-profit companies that provide telemedicine visits and sell prescription drugs directly to patients.

- Although they are growing in popularity, DTC teledermatology platforms may lead to overdiagnosis, overtreatment, and fragmentation of health care. Knowledge of teledermatology will be vital to counsel patients on the risks and benefits of these platforms.

FDA to decide by June on future of COVID vaccines

April 6.

But members of the panel also acknowledged that it will be an uphill battle to reach that goal, especially given how quickly the virus continues to change.

The members of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee said they want to find the balance that makes sure Americans are protected against severe illness and death but doesn’t wear them out with constant recommendations for boosters.

“We don’t feel comfortable with multiple boosters every 8 weeks,” said committee chairman Arnold Monto, MD, professor emeritus of public health at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “We’d love to see an annual vaccination similar to influenza but realize that the evolution of the virus will dictate how we respond in terms of additional vaccine doses.”

The virus itself will dictate vaccination plans, he said.

The government must also keep its focus on convincing Americans who haven’t been vaccinated to join the club, said committee member Henry H. Bernstein, DO, given that “it seems quite obvious that those who are vaccinated do better than those who aren’t vaccinated.”

The government should clearly communicate to the public the goals of vaccination, he said.

“I would suggest that our overall aim is to prevent severe disease, hospitalization, and death more than just infection prevention,” said Dr. Bernstein, professor of pediatrics at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y.

The FDA called the meeting of its advisers to discuss overall booster and vaccine strategy, even though it already authorized a fourth dose of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines for certain immune compromised adults and for everyone over age 50.

Early in the all-day meeting, temporary committee member James Hildreth, MD, the president of Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tenn., asked why that authorization was given without the panel’s input. Peter Marks, MD, the director of FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said the decision was based on data from the United Kingdom and Israel that suggested immunity from a third shot was already waning.

Dr. Marks later said the fourth dose was “authorized as a stopgap measure until we could get something else in place,” because the aim was to protect older Americans who had died at a higher rate than younger individuals.

“I think we’re very much on board that we simply can’t be boosting people as frequently as we are,” said Dr. Marks.

Not enough information to make broader plan

The meeting was meant to be a larger conversation about how to keep pace with the evolving virus and to set up a vaccine selection and development process to better and more quickly respond to changes, such as new variants.

But committee members said they felt stymied by a lack of information. They wanted more data from vaccine manufacturers’ clinical trials. And they noted that so far, there’s no objective, reliable lab-based measurement of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness – known as a correlate of immunity. Instead, public health officials have looked at rates of hospitalizations and deaths to measure whether the vaccine is still offering protection.

“The question is, what is insufficient protection?” asked H. Cody Meissner, MD, director of pediatric infectious disease at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. “At what point will we say the vaccine isn’t working well enough?”

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention officials presented data showing that a third shot has been more effective than a two-shot regimen in preventing serious disease and death, and that the three shots were significantly more protective than being unvaccinated.