User login

Children and COVID: Downward trend reverses with small increase in new cases

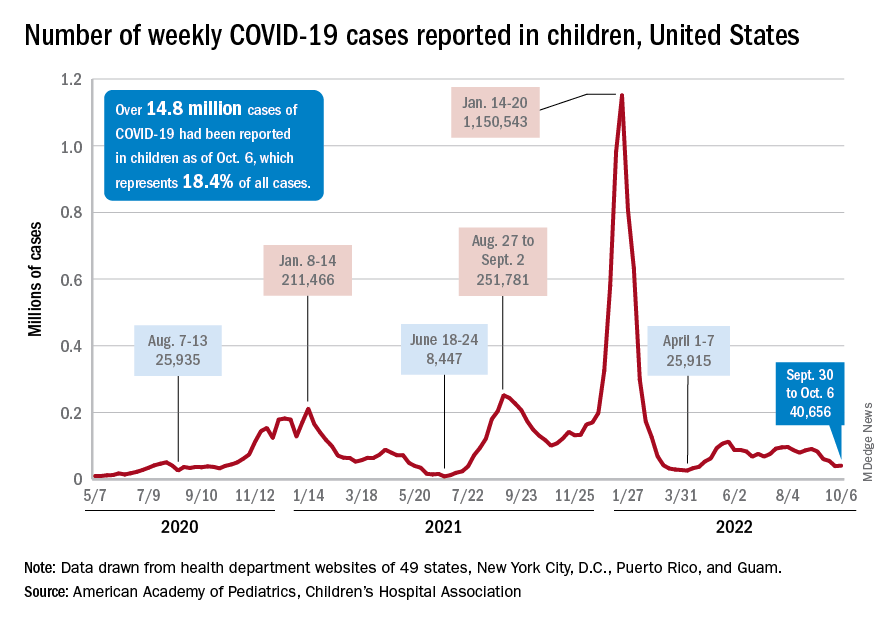

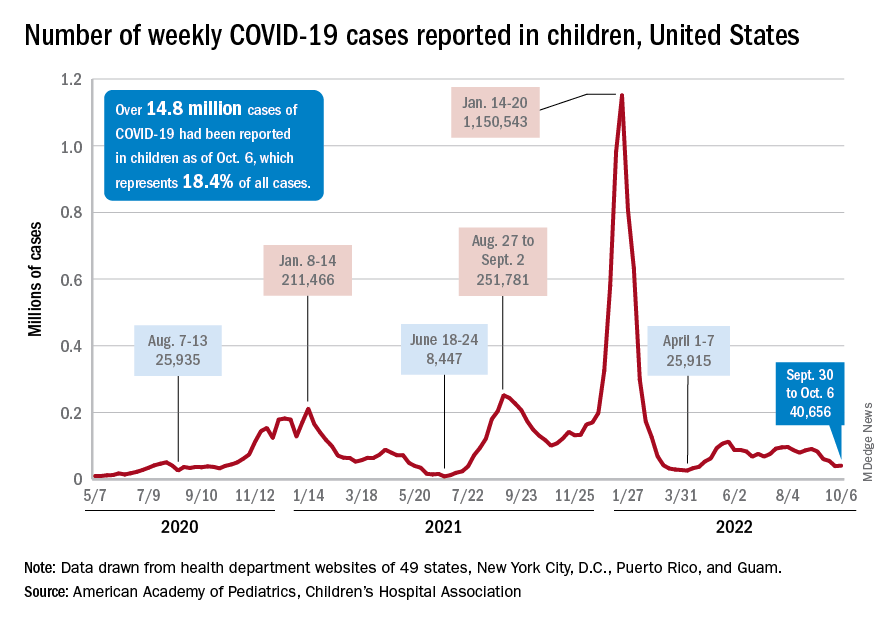

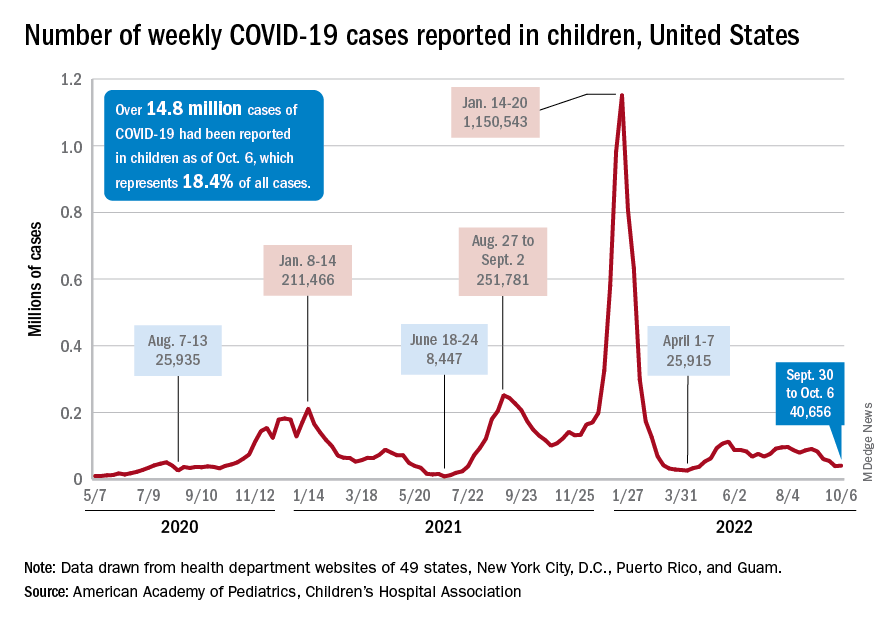

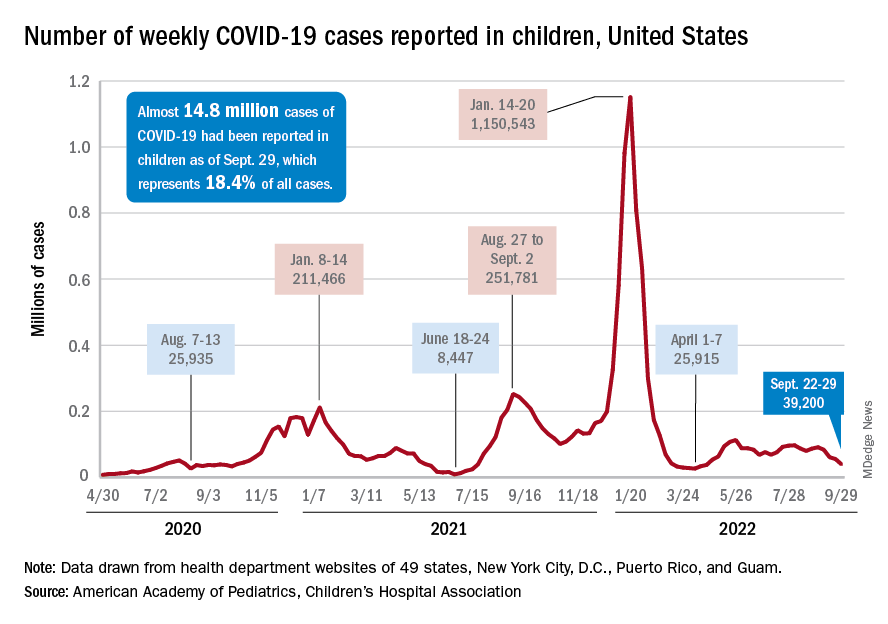

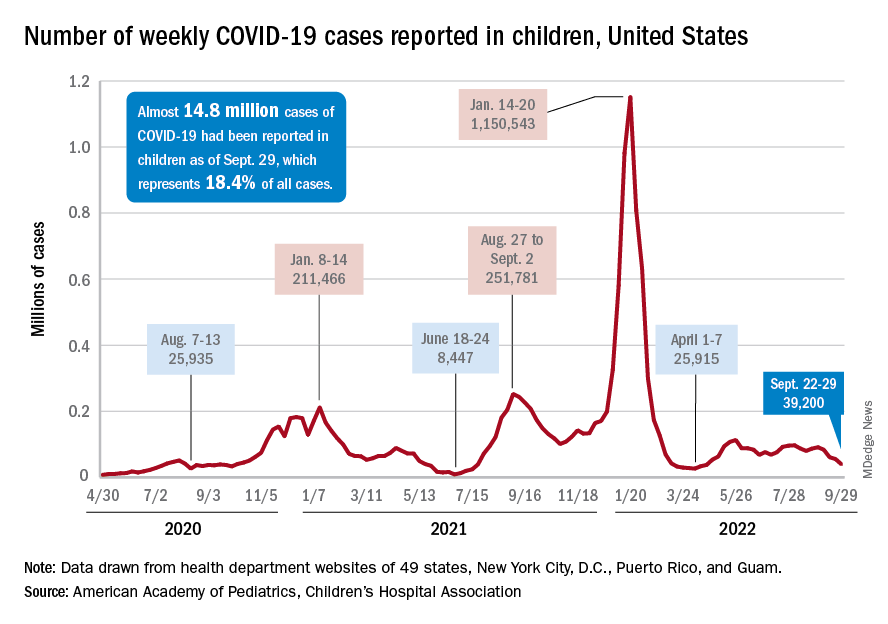

A small increase in new cases brought COVID-19’s latest losing streak to an end at 4 weeks, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The 40,656 new cases reported bring the U.S. cumulative count of child COVID-19 cases to over 14.8 million since the pandemic began, which represents 18.4% of all cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report based on state-level data.

The increase in new cases was not reflected in emergency department visits or hospital admissions, which both continued sustained declines that started in August. In the week from Sept. 27 to Oct. 4, the 7-day averages for ED visits with diagnosed COVID were down by 21.5% (age 0-11), 27.3% (12-15), and 18.2% (16-17), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, while the most recent 7-day average for new admissions – 127 per day for Oct. 2-8 – among children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID was down from 161 per day the previous week, a drop of over 21%.

The state-level data that are currently available (several states are no longer reporting) show Alaska (25.5%) and Vermont (25.4%) have the highest proportions of cumulative cases in children, and Florida (12.3%) and Utah (13.5%) have the lowest. Rhode Island has the highest rate of COVID-19 per 100,000 children at 40,427, while Missouri has the lowest at 14,252. The national average is 19,687 per 100,000, the AAP and CHA reported.

Taking a look at vaccination

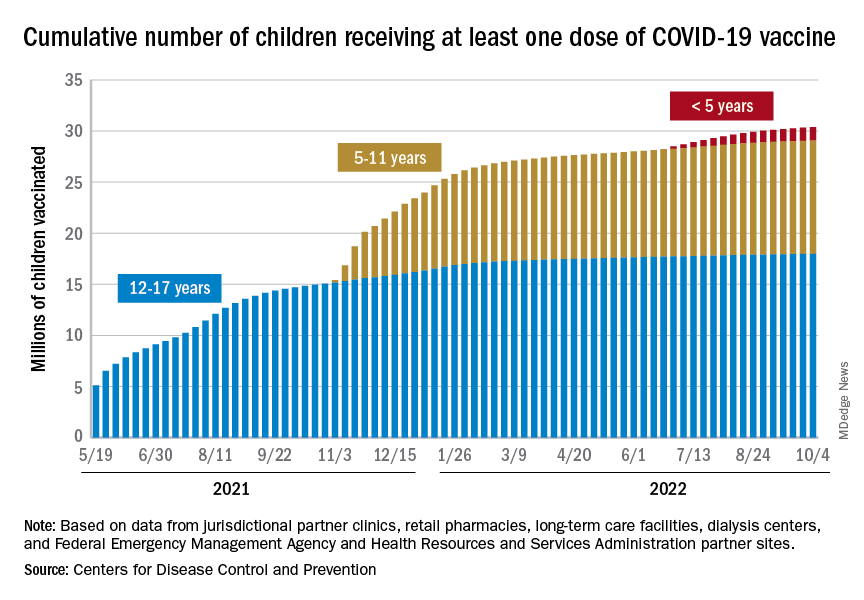

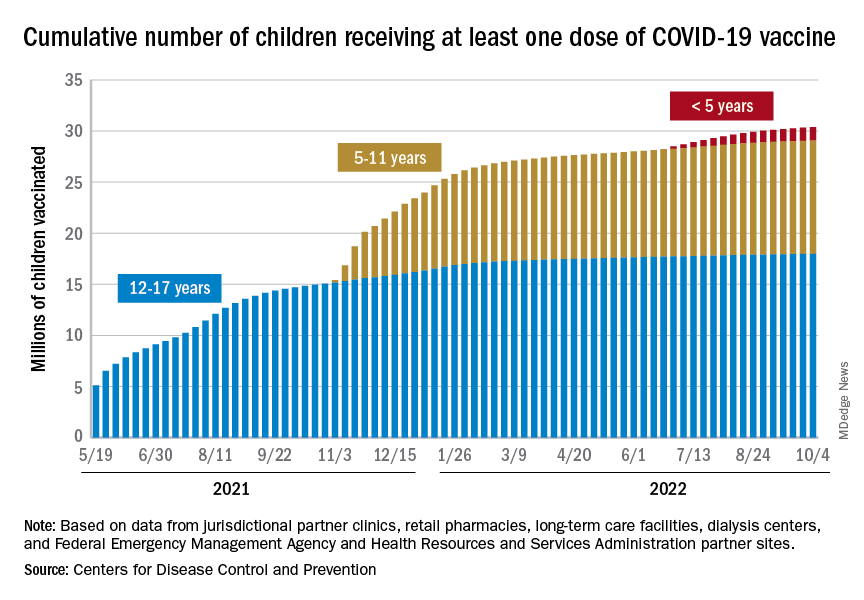

Vaccinations were up slightly in children aged 12-17 years, as 20,000 initial doses were given during the week of Sept. 29 to Oct. 5, compared with 17,000 and 18,000 the previous 2 weeks. Initial vaccinations in younger children, however, continued declines dating back to August, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination trends report.

The District of Columbia and Massachusetts have the most highly vaccinated groups of 12- to 17-year-olds, as 100% and 95%, respectively, have received initial doses, while Wyoming (39%) and Idaho (42%) have the lowest. D.C. (73%) and Vermont (68%) have the highest proportions of vaccinated 5- to 11-year-olds, and Alabama (17%) and Mississippi (18%) have the lowest. For children under age 5 years, those in D.C. (33%) and Vermont (26%) are the most likely to have received an initial COVID vaccination, while Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi share national-low rates of 2%, the AAP said its report, which is based on CDC data.

When all states and territories are combined, 71% of children aged 12-17 have received at least one dose of vaccine, as have 38.6% of all children 5-11 years old and 6.7% of those under age 5. Almost 61% of the nation’s 16- to 17-year-olds have been fully vaccinated, along with 31.5% of those aged 5-11 and 2.4% of children younger than 5 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

About 42 million children – 58% of the population under the age of 18 years – have not received any vaccine yet, the AAP noted. Meanwhile, CDC data indicate that 36 children died of COVID in the last week, with pediatric deaths now totaling 1,781 over the course of the pandemic.

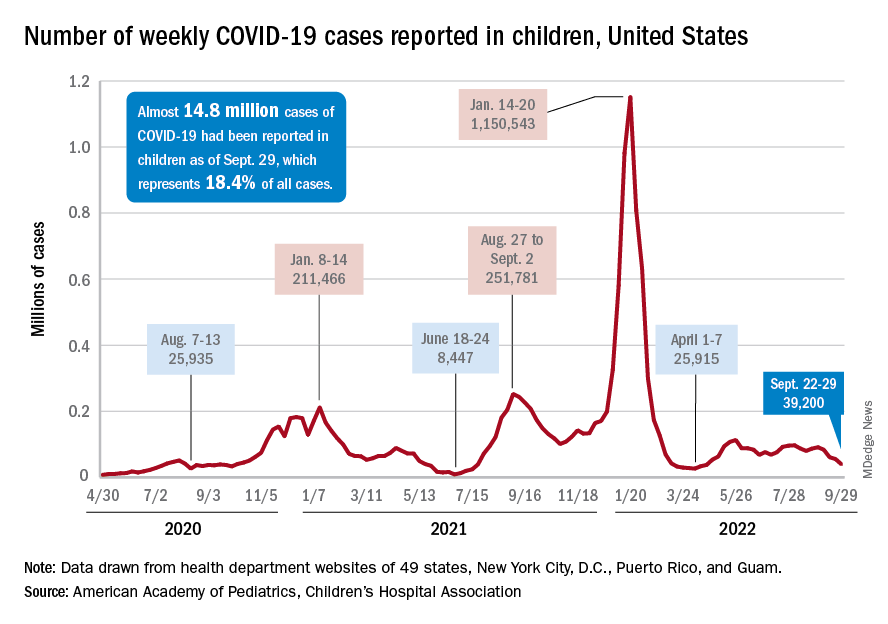

A small increase in new cases brought COVID-19’s latest losing streak to an end at 4 weeks, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The 40,656 new cases reported bring the U.S. cumulative count of child COVID-19 cases to over 14.8 million since the pandemic began, which represents 18.4% of all cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report based on state-level data.

The increase in new cases was not reflected in emergency department visits or hospital admissions, which both continued sustained declines that started in August. In the week from Sept. 27 to Oct. 4, the 7-day averages for ED visits with diagnosed COVID were down by 21.5% (age 0-11), 27.3% (12-15), and 18.2% (16-17), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, while the most recent 7-day average for new admissions – 127 per day for Oct. 2-8 – among children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID was down from 161 per day the previous week, a drop of over 21%.

The state-level data that are currently available (several states are no longer reporting) show Alaska (25.5%) and Vermont (25.4%) have the highest proportions of cumulative cases in children, and Florida (12.3%) and Utah (13.5%) have the lowest. Rhode Island has the highest rate of COVID-19 per 100,000 children at 40,427, while Missouri has the lowest at 14,252. The national average is 19,687 per 100,000, the AAP and CHA reported.

Taking a look at vaccination

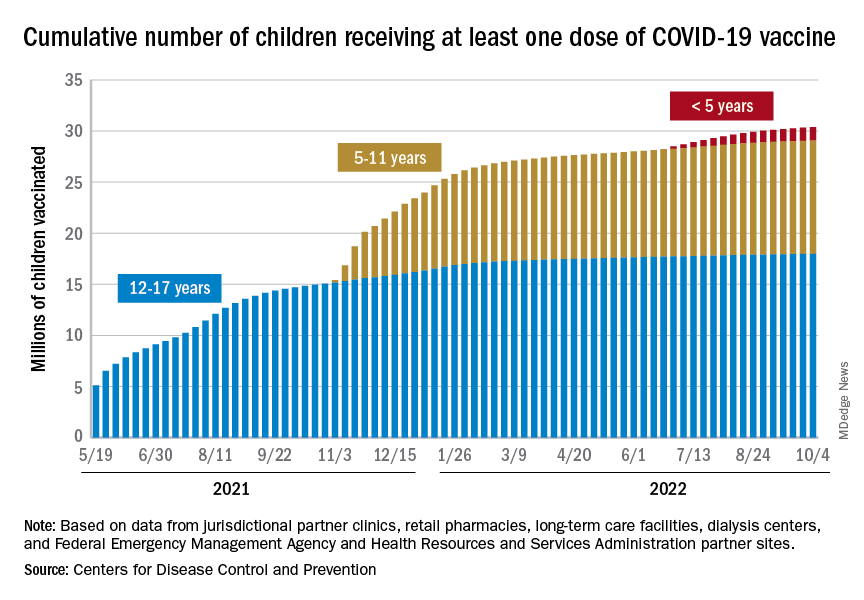

Vaccinations were up slightly in children aged 12-17 years, as 20,000 initial doses were given during the week of Sept. 29 to Oct. 5, compared with 17,000 and 18,000 the previous 2 weeks. Initial vaccinations in younger children, however, continued declines dating back to August, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination trends report.

The District of Columbia and Massachusetts have the most highly vaccinated groups of 12- to 17-year-olds, as 100% and 95%, respectively, have received initial doses, while Wyoming (39%) and Idaho (42%) have the lowest. D.C. (73%) and Vermont (68%) have the highest proportions of vaccinated 5- to 11-year-olds, and Alabama (17%) and Mississippi (18%) have the lowest. For children under age 5 years, those in D.C. (33%) and Vermont (26%) are the most likely to have received an initial COVID vaccination, while Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi share national-low rates of 2%, the AAP said its report, which is based on CDC data.

When all states and territories are combined, 71% of children aged 12-17 have received at least one dose of vaccine, as have 38.6% of all children 5-11 years old and 6.7% of those under age 5. Almost 61% of the nation’s 16- to 17-year-olds have been fully vaccinated, along with 31.5% of those aged 5-11 and 2.4% of children younger than 5 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

About 42 million children – 58% of the population under the age of 18 years – have not received any vaccine yet, the AAP noted. Meanwhile, CDC data indicate that 36 children died of COVID in the last week, with pediatric deaths now totaling 1,781 over the course of the pandemic.

A small increase in new cases brought COVID-19’s latest losing streak to an end at 4 weeks, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The 40,656 new cases reported bring the U.S. cumulative count of child COVID-19 cases to over 14.8 million since the pandemic began, which represents 18.4% of all cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report based on state-level data.

The increase in new cases was not reflected in emergency department visits or hospital admissions, which both continued sustained declines that started in August. In the week from Sept. 27 to Oct. 4, the 7-day averages for ED visits with diagnosed COVID were down by 21.5% (age 0-11), 27.3% (12-15), and 18.2% (16-17), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, while the most recent 7-day average for new admissions – 127 per day for Oct. 2-8 – among children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID was down from 161 per day the previous week, a drop of over 21%.

The state-level data that are currently available (several states are no longer reporting) show Alaska (25.5%) and Vermont (25.4%) have the highest proportions of cumulative cases in children, and Florida (12.3%) and Utah (13.5%) have the lowest. Rhode Island has the highest rate of COVID-19 per 100,000 children at 40,427, while Missouri has the lowest at 14,252. The national average is 19,687 per 100,000, the AAP and CHA reported.

Taking a look at vaccination

Vaccinations were up slightly in children aged 12-17 years, as 20,000 initial doses were given during the week of Sept. 29 to Oct. 5, compared with 17,000 and 18,000 the previous 2 weeks. Initial vaccinations in younger children, however, continued declines dating back to August, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination trends report.

The District of Columbia and Massachusetts have the most highly vaccinated groups of 12- to 17-year-olds, as 100% and 95%, respectively, have received initial doses, while Wyoming (39%) and Idaho (42%) have the lowest. D.C. (73%) and Vermont (68%) have the highest proportions of vaccinated 5- to 11-year-olds, and Alabama (17%) and Mississippi (18%) have the lowest. For children under age 5 years, those in D.C. (33%) and Vermont (26%) are the most likely to have received an initial COVID vaccination, while Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi share national-low rates of 2%, the AAP said its report, which is based on CDC data.

When all states and territories are combined, 71% of children aged 12-17 have received at least one dose of vaccine, as have 38.6% of all children 5-11 years old and 6.7% of those under age 5. Almost 61% of the nation’s 16- to 17-year-olds have been fully vaccinated, along with 31.5% of those aged 5-11 and 2.4% of children younger than 5 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

About 42 million children – 58% of the population under the age of 18 years – have not received any vaccine yet, the AAP noted. Meanwhile, CDC data indicate that 36 children died of COVID in the last week, with pediatric deaths now totaling 1,781 over the course of the pandemic.

Mother-to-child transmission of SARS-CoV-2 may be underestimated

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – The rate of mother-to-child transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection is likely higher than the current estimate of 2%-8%, suggests a recent study using cord blood serology to determine incidence. The study was presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

“Cord blood screening is a potential tool to identify SARS-CoV-2 infected and/or exposed neonates who should then be followed for long-term consequences of mother-to-child transmission,” Amy Yeh, MD, an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, told attendees at the meeting.

Dr. Yeh and her colleagues collected cord blood from more than 500 mothers at LAC+USC Medical Center from October 2021 to April 2022 and tested them for IgG antibodies against three SARS-CoV-2 antigens: nucleoprotein (N), receptor-binding domain (RBD), and spike protein (S1). Results with an IgG mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) above 700 were considered positive for IgG antibodies. A positive result for N as well as RBD or S1 indicated a natural infection while a positive result for only RBD or S1 indicated a vaccine response or past infection.

The researchers also tested a subset of the IgG positive samples for IgM and IgA antibodies against N, S1, and RBD, with an IgM MFI greater than 24 and an IgA MFI greater than 102 used as the thresholds for positive results.

Among 384 cord blood samples analyzed, 85.4% were positive for IgG against RBD, indicating that the mother had SARS-CoV-2 immunity from either a past infection or vaccination. Of these anti-RBD positive samples, 60.7% were anti-N IgG negative, suggesting that N had waned since vaccination or the past infection.

Since the other 39.3% that were anti-N IgG positive suggest a past maternal infection, the researchers assessed these 129 samples for IgM and IgA antibodies against RBD. They found that 16 of them had high levels of anti-RBD IgA and/or IgM antibodies, pointing to a rate of mother-to-child-transmission of up to 12.4%.

Sallie Permar, MD, PhD, a professor and the chair of pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, who was not involved in the research, said most studies of placental transmission have focused on virologic testing, such as PCR. “Serologic tests for congenital infections are inherently challenged by the transfer of maternal IgG across the placenta and therefore must rely on non-IgG isotype response detection, which have inherently been more susceptible to false-positive results than IgG-based tests,” Dr. Permar said.

Also, “it is unclear if virologic testing was performed in the infants, which, if positive in the same infants for which cord blood IgM/IgA responses were identified, could further validate positive serologic findings,” added Dr. Permar, who is also pediatrician-in-chief at New York-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital.

Given these limitations, Dr. Permar reiterated that diagnostics for congenital SARS-CoV-2 continue to evolve, even if congenital SARS-CoV-2 infection currently appears rare. Dr. Permar said she agreed with Dr. Yeh that following those who do develop this infection is important.

“There have been initial reports of neurodevelopmental and other outcomes from long-term follow-up cohorts of infants exposed to SARS-CoV-2 infection in utero with variable results and it should continue to be pursued using cohorts both enrolled early in the pandemic and those enrolled more recently after population-level immunity to SARS-CoV-2 was achieved,” said Dr. Permar.

Dr. Permar serves as a consultant to Moderna, Pfizer, Merck, Dynavax, and Hoopika on their CMV vaccine programs and has led sponsored research programs with Moderna and Merck. Information on study funding and on disclosures for Dr. Yeh was unavailable.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – The rate of mother-to-child transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection is likely higher than the current estimate of 2%-8%, suggests a recent study using cord blood serology to determine incidence. The study was presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

“Cord blood screening is a potential tool to identify SARS-CoV-2 infected and/or exposed neonates who should then be followed for long-term consequences of mother-to-child transmission,” Amy Yeh, MD, an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, told attendees at the meeting.

Dr. Yeh and her colleagues collected cord blood from more than 500 mothers at LAC+USC Medical Center from October 2021 to April 2022 and tested them for IgG antibodies against three SARS-CoV-2 antigens: nucleoprotein (N), receptor-binding domain (RBD), and spike protein (S1). Results with an IgG mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) above 700 were considered positive for IgG antibodies. A positive result for N as well as RBD or S1 indicated a natural infection while a positive result for only RBD or S1 indicated a vaccine response or past infection.

The researchers also tested a subset of the IgG positive samples for IgM and IgA antibodies against N, S1, and RBD, with an IgM MFI greater than 24 and an IgA MFI greater than 102 used as the thresholds for positive results.

Among 384 cord blood samples analyzed, 85.4% were positive for IgG against RBD, indicating that the mother had SARS-CoV-2 immunity from either a past infection or vaccination. Of these anti-RBD positive samples, 60.7% were anti-N IgG negative, suggesting that N had waned since vaccination or the past infection.

Since the other 39.3% that were anti-N IgG positive suggest a past maternal infection, the researchers assessed these 129 samples for IgM and IgA antibodies against RBD. They found that 16 of them had high levels of anti-RBD IgA and/or IgM antibodies, pointing to a rate of mother-to-child-transmission of up to 12.4%.

Sallie Permar, MD, PhD, a professor and the chair of pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, who was not involved in the research, said most studies of placental transmission have focused on virologic testing, such as PCR. “Serologic tests for congenital infections are inherently challenged by the transfer of maternal IgG across the placenta and therefore must rely on non-IgG isotype response detection, which have inherently been more susceptible to false-positive results than IgG-based tests,” Dr. Permar said.

Also, “it is unclear if virologic testing was performed in the infants, which, if positive in the same infants for which cord blood IgM/IgA responses were identified, could further validate positive serologic findings,” added Dr. Permar, who is also pediatrician-in-chief at New York-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital.

Given these limitations, Dr. Permar reiterated that diagnostics for congenital SARS-CoV-2 continue to evolve, even if congenital SARS-CoV-2 infection currently appears rare. Dr. Permar said she agreed with Dr. Yeh that following those who do develop this infection is important.

“There have been initial reports of neurodevelopmental and other outcomes from long-term follow-up cohorts of infants exposed to SARS-CoV-2 infection in utero with variable results and it should continue to be pursued using cohorts both enrolled early in the pandemic and those enrolled more recently after population-level immunity to SARS-CoV-2 was achieved,” said Dr. Permar.

Dr. Permar serves as a consultant to Moderna, Pfizer, Merck, Dynavax, and Hoopika on their CMV vaccine programs and has led sponsored research programs with Moderna and Merck. Information on study funding and on disclosures for Dr. Yeh was unavailable.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – The rate of mother-to-child transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection is likely higher than the current estimate of 2%-8%, suggests a recent study using cord blood serology to determine incidence. The study was presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

“Cord blood screening is a potential tool to identify SARS-CoV-2 infected and/or exposed neonates who should then be followed for long-term consequences of mother-to-child transmission,” Amy Yeh, MD, an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, told attendees at the meeting.

Dr. Yeh and her colleagues collected cord blood from more than 500 mothers at LAC+USC Medical Center from October 2021 to April 2022 and tested them for IgG antibodies against three SARS-CoV-2 antigens: nucleoprotein (N), receptor-binding domain (RBD), and spike protein (S1). Results with an IgG mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) above 700 were considered positive for IgG antibodies. A positive result for N as well as RBD or S1 indicated a natural infection while a positive result for only RBD or S1 indicated a vaccine response or past infection.

The researchers also tested a subset of the IgG positive samples for IgM and IgA antibodies against N, S1, and RBD, with an IgM MFI greater than 24 and an IgA MFI greater than 102 used as the thresholds for positive results.

Among 384 cord blood samples analyzed, 85.4% were positive for IgG against RBD, indicating that the mother had SARS-CoV-2 immunity from either a past infection or vaccination. Of these anti-RBD positive samples, 60.7% were anti-N IgG negative, suggesting that N had waned since vaccination or the past infection.

Since the other 39.3% that were anti-N IgG positive suggest a past maternal infection, the researchers assessed these 129 samples for IgM and IgA antibodies against RBD. They found that 16 of them had high levels of anti-RBD IgA and/or IgM antibodies, pointing to a rate of mother-to-child-transmission of up to 12.4%.

Sallie Permar, MD, PhD, a professor and the chair of pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, who was not involved in the research, said most studies of placental transmission have focused on virologic testing, such as PCR. “Serologic tests for congenital infections are inherently challenged by the transfer of maternal IgG across the placenta and therefore must rely on non-IgG isotype response detection, which have inherently been more susceptible to false-positive results than IgG-based tests,” Dr. Permar said.

Also, “it is unclear if virologic testing was performed in the infants, which, if positive in the same infants for which cord blood IgM/IgA responses were identified, could further validate positive serologic findings,” added Dr. Permar, who is also pediatrician-in-chief at New York-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital.

Given these limitations, Dr. Permar reiterated that diagnostics for congenital SARS-CoV-2 continue to evolve, even if congenital SARS-CoV-2 infection currently appears rare. Dr. Permar said she agreed with Dr. Yeh that following those who do develop this infection is important.

“There have been initial reports of neurodevelopmental and other outcomes from long-term follow-up cohorts of infants exposed to SARS-CoV-2 infection in utero with variable results and it should continue to be pursued using cohorts both enrolled early in the pandemic and those enrolled more recently after population-level immunity to SARS-CoV-2 was achieved,” said Dr. Permar.

Dr. Permar serves as a consultant to Moderna, Pfizer, Merck, Dynavax, and Hoopika on their CMV vaccine programs and has led sponsored research programs with Moderna and Merck. Information on study funding and on disclosures for Dr. Yeh was unavailable.

AT AAP 2022

Three COVID scenarios that could spell trouble for the fall

As the United States enters a third fall with COVID-19, the virus for many is seemingly gone – or at least out of mind. But for those keeping watch, it is far from forgotten as deaths and infections continue to mount at a lower but steady pace.

What does that mean for the upcoming months? Experts predict different scenarios, some more dire than others – with one more encouraging.

In the United States, more than 300 people still die every day from COVID and more than 44,000 new daily cases are reported, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But progress is undeniable. The stark daily death tolls of 2020 have plummeted. Vaccines and treatments have dramatically reduced severe illness, and mask requirements have mostly turned to personal preference.

among them more-resistant variants coupled with waning immunity, the potential for a “twindemic” with a flu/COVID onslaught, and underuse of lifesaving vaccines and treatments.

Variants loom/waning immunity

Omicron variant BA.5 still makes up about 80% of infections in the United States, followed by BA4.6, according to the CDC, but other subvariants are emerging and showing signs of resistance to current antiviral treatments.

Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in San Diego, said about COVID this fall: “There will be another wave, magnitude unknown.”

He said subvariants XBB and BQ.1.1 “have extreme levels of immune evasion and both could pose a challenge,” explaining that XBB is more likely to cause trouble than BQ.1.1 because it is even more resistant to natural or vaccine-induced immunity.

Dr. Topol pointed to new research on those variants in a preprint posted on bioRxiv. The authors’ conclusion: “These results suggest that current herd immunity and BA.5 vaccine boosters may not provide sufficiently broad protection against infection.”

Another variant to watch, some experts say, is Omicron subvariant BA.2.75.2, which has shown resistance to antiviral treatments. It is also growing at a rather alarming rate, says Michael Sweat, PhD, director of the Medical University of South Carolina Center for Global Health in Charleston. That subvariant currently makes up under 2% of U.S. cases but has spread to at least 55 countries and 43 U.S. states after first appearing at the end of last year globally and in mid-June in the United States.

A non–peer-reviewed preprint study from Sweden found that the variant in blood samples was neutralized on average “at titers approximately 6.5 times lower than BA.5, making BA.2.75.2 the most [neutralization-resistant] variant evaluated to date.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology at University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, said in an interview the U.S. waves often follow Europe’s, and Europe has seen a recent spike in cases and hospitalizations not related to Omicron subvariants, but to weather changes, waning immunity, and changes in behavior.

The World Health Organization reported on Oct. 5 that, while cases were down in every other region of the world, Europe’s numbers stand out, with an 8% increase in cases from the week before.

Dr. Jetelina cited events such as Oktoberfest in Germany, which ended in the first week of October after drawing nearly 6 million people over 2 weeks, as a potential contributor, and people heading indoors as weather patterns change in Europe.

Ali Mokdad, PhD, chief strategy officer for population health at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview he is less worried about the documented variants we know about than he is about the potential for a new immune-escape variety yet to emerge.

“Right now we know the Chinese are gearing up to open up the country, and because they have low immunity and little infection, we expect in China there will be a lot of spread of Omicron,” he said. “It’s possible because of the number of infections we could see a new variant.”

Dr. Mokdad said waning immunity could also leave populations vulnerable to variants.

“Even if you get infected, after about 5 months, you’re susceptible again. Remember, most of the infections from Omicron happened in January or February 2022, and we had two waves after that,” he said.

The new bivalent vaccines tweaked to target some Omicron variants will help, Dr. Mokdad said, but he noted, “people are very reluctant to take it.”

Jennifer Nuzzo, DrPH, professor of epidemiology and director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University, Providence, R.I., worries that in the United States we have less ability this year to track variants as funding has receded for testing kits and testing sites. Most people are testing at home – which doesn’t show up in the numbers – and the United States is relying more on other countries’ data to spot trends.

“I think we’re just going to have less visibility into the circulation of this virus,” she said in an interview.

‘Twindemic’: COVID and flu

Dr. Jetelina noted Australia and New Zealand just wrapped up a flu season that saw flu numbers returning to normal after a sharp drop in the last 2 years, and North America typically follows suit.

“We do expect flu will be here in the United States and probably at levels that we saw prepandemic. We’re all holding our breath to see how our health systems hold up with COVID-19 and flu. We haven’t really experienced that yet,” she said.

There is some disagreement, however, about the possibility of a so-called “twindemic” of influenza and COVID.

Richard Webby, PhD, an infectious disease specialist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, said in an interview he thinks the possibility of both viruses spiking at the same time is unlikely.

“That’s not to say we won’t get flu and COVID activity in the same winter,” he explained, “but I think both roaring at the same time is unlikely.”

As an indicator, he said, at the beginning of the flu season last year in the Northern Hemisphere, flu activity started to pick up, but when the Omicron variant came along, “flu just wasn’t able to compete in that same environment and flu numbers dropped right off.” Previous literature suggests that when one virus is spiking it’s hard for another respiratory virus to take hold.

Vaccine, treatment underuse

Another threat is vaccines, boosters, and treatments sitting on shelves.

Dr. Sweat referred to frustration with vaccine uptake that seems to be “frozen in amber.”

As of Oct. 4, only 5.3% of people in the United States who were eligible had received the updated booster launched in early September.

Dr. Nuzzo said boosters for people at least 65 years old will be key to severity of COVID this season.

“I think that’s probably the biggest factor going into the fall and winter,” she said.

Only 38% of people at least 50 years old and 45% of those at least 65 years old had gotten a second booster as of early October.

“If we do nothing else, we have to increase booster uptake in that group,” Dr. Nuzzo said.

She said the treatment nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid, Pfizer) for treating mild to moderate COVID-19 in patients at high risk for severe disease is greatly underused, often because providers aren’t prescribing it because they don’t think it helps, are worried about drug interactions, or are worried about its “rebound” effect.

Dr. Nuzzo urged greater use of the drug and education on how to manage drug interactions.

“We have very strong data that it does help keep people out of hospital. Sure, there may be a rebound, but that pales in comparison to the risk of being hospitalized,” she said.

Calm COVID season?

Not all predictions are dire. There is another little-talked-about scenario, Dr. Sweat said – that we could be in for a calm COVID season, and those who seem to be only mildly concerned about COVID may find those thoughts justified in the numbers.

Omicron blew through with such strength, he noted, that it may have left wide immunity in its wake. Because variants seem to be staying in the Omicron family, that may signal optimism.

“If the next variant is a descendant of the Omicron lineage, I would suspect that all these people who just got infected will have some protection, not perfect, but quite a bit of protection,” Dr. Sweat said.

Dr. Topol, Dr. Nuzzo, Dr. Sweat, Dr. Webby, Dr. Mokdad, and Dr. Jetelina reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As the United States enters a third fall with COVID-19, the virus for many is seemingly gone – or at least out of mind. But for those keeping watch, it is far from forgotten as deaths and infections continue to mount at a lower but steady pace.

What does that mean for the upcoming months? Experts predict different scenarios, some more dire than others – with one more encouraging.

In the United States, more than 300 people still die every day from COVID and more than 44,000 new daily cases are reported, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But progress is undeniable. The stark daily death tolls of 2020 have plummeted. Vaccines and treatments have dramatically reduced severe illness, and mask requirements have mostly turned to personal preference.

among them more-resistant variants coupled with waning immunity, the potential for a “twindemic” with a flu/COVID onslaught, and underuse of lifesaving vaccines and treatments.

Variants loom/waning immunity

Omicron variant BA.5 still makes up about 80% of infections in the United States, followed by BA4.6, according to the CDC, but other subvariants are emerging and showing signs of resistance to current antiviral treatments.

Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in San Diego, said about COVID this fall: “There will be another wave, magnitude unknown.”

He said subvariants XBB and BQ.1.1 “have extreme levels of immune evasion and both could pose a challenge,” explaining that XBB is more likely to cause trouble than BQ.1.1 because it is even more resistant to natural or vaccine-induced immunity.

Dr. Topol pointed to new research on those variants in a preprint posted on bioRxiv. The authors’ conclusion: “These results suggest that current herd immunity and BA.5 vaccine boosters may not provide sufficiently broad protection against infection.”

Another variant to watch, some experts say, is Omicron subvariant BA.2.75.2, which has shown resistance to antiviral treatments. It is also growing at a rather alarming rate, says Michael Sweat, PhD, director of the Medical University of South Carolina Center for Global Health in Charleston. That subvariant currently makes up under 2% of U.S. cases but has spread to at least 55 countries and 43 U.S. states after first appearing at the end of last year globally and in mid-June in the United States.

A non–peer-reviewed preprint study from Sweden found that the variant in blood samples was neutralized on average “at titers approximately 6.5 times lower than BA.5, making BA.2.75.2 the most [neutralization-resistant] variant evaluated to date.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology at University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, said in an interview the U.S. waves often follow Europe’s, and Europe has seen a recent spike in cases and hospitalizations not related to Omicron subvariants, but to weather changes, waning immunity, and changes in behavior.

The World Health Organization reported on Oct. 5 that, while cases were down in every other region of the world, Europe’s numbers stand out, with an 8% increase in cases from the week before.

Dr. Jetelina cited events such as Oktoberfest in Germany, which ended in the first week of October after drawing nearly 6 million people over 2 weeks, as a potential contributor, and people heading indoors as weather patterns change in Europe.

Ali Mokdad, PhD, chief strategy officer for population health at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview he is less worried about the documented variants we know about than he is about the potential for a new immune-escape variety yet to emerge.

“Right now we know the Chinese are gearing up to open up the country, and because they have low immunity and little infection, we expect in China there will be a lot of spread of Omicron,” he said. “It’s possible because of the number of infections we could see a new variant.”

Dr. Mokdad said waning immunity could also leave populations vulnerable to variants.

“Even if you get infected, after about 5 months, you’re susceptible again. Remember, most of the infections from Omicron happened in January or February 2022, and we had two waves after that,” he said.

The new bivalent vaccines tweaked to target some Omicron variants will help, Dr. Mokdad said, but he noted, “people are very reluctant to take it.”

Jennifer Nuzzo, DrPH, professor of epidemiology and director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University, Providence, R.I., worries that in the United States we have less ability this year to track variants as funding has receded for testing kits and testing sites. Most people are testing at home – which doesn’t show up in the numbers – and the United States is relying more on other countries’ data to spot trends.

“I think we’re just going to have less visibility into the circulation of this virus,” she said in an interview.

‘Twindemic’: COVID and flu

Dr. Jetelina noted Australia and New Zealand just wrapped up a flu season that saw flu numbers returning to normal after a sharp drop in the last 2 years, and North America typically follows suit.

“We do expect flu will be here in the United States and probably at levels that we saw prepandemic. We’re all holding our breath to see how our health systems hold up with COVID-19 and flu. We haven’t really experienced that yet,” she said.

There is some disagreement, however, about the possibility of a so-called “twindemic” of influenza and COVID.

Richard Webby, PhD, an infectious disease specialist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, said in an interview he thinks the possibility of both viruses spiking at the same time is unlikely.

“That’s not to say we won’t get flu and COVID activity in the same winter,” he explained, “but I think both roaring at the same time is unlikely.”

As an indicator, he said, at the beginning of the flu season last year in the Northern Hemisphere, flu activity started to pick up, but when the Omicron variant came along, “flu just wasn’t able to compete in that same environment and flu numbers dropped right off.” Previous literature suggests that when one virus is spiking it’s hard for another respiratory virus to take hold.

Vaccine, treatment underuse

Another threat is vaccines, boosters, and treatments sitting on shelves.

Dr. Sweat referred to frustration with vaccine uptake that seems to be “frozen in amber.”

As of Oct. 4, only 5.3% of people in the United States who were eligible had received the updated booster launched in early September.

Dr. Nuzzo said boosters for people at least 65 years old will be key to severity of COVID this season.

“I think that’s probably the biggest factor going into the fall and winter,” she said.

Only 38% of people at least 50 years old and 45% of those at least 65 years old had gotten a second booster as of early October.

“If we do nothing else, we have to increase booster uptake in that group,” Dr. Nuzzo said.

She said the treatment nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid, Pfizer) for treating mild to moderate COVID-19 in patients at high risk for severe disease is greatly underused, often because providers aren’t prescribing it because they don’t think it helps, are worried about drug interactions, or are worried about its “rebound” effect.

Dr. Nuzzo urged greater use of the drug and education on how to manage drug interactions.

“We have very strong data that it does help keep people out of hospital. Sure, there may be a rebound, but that pales in comparison to the risk of being hospitalized,” she said.

Calm COVID season?

Not all predictions are dire. There is another little-talked-about scenario, Dr. Sweat said – that we could be in for a calm COVID season, and those who seem to be only mildly concerned about COVID may find those thoughts justified in the numbers.

Omicron blew through with such strength, he noted, that it may have left wide immunity in its wake. Because variants seem to be staying in the Omicron family, that may signal optimism.

“If the next variant is a descendant of the Omicron lineage, I would suspect that all these people who just got infected will have some protection, not perfect, but quite a bit of protection,” Dr. Sweat said.

Dr. Topol, Dr. Nuzzo, Dr. Sweat, Dr. Webby, Dr. Mokdad, and Dr. Jetelina reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As the United States enters a third fall with COVID-19, the virus for many is seemingly gone – or at least out of mind. But for those keeping watch, it is far from forgotten as deaths and infections continue to mount at a lower but steady pace.

What does that mean for the upcoming months? Experts predict different scenarios, some more dire than others – with one more encouraging.

In the United States, more than 300 people still die every day from COVID and more than 44,000 new daily cases are reported, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But progress is undeniable. The stark daily death tolls of 2020 have plummeted. Vaccines and treatments have dramatically reduced severe illness, and mask requirements have mostly turned to personal preference.

among them more-resistant variants coupled with waning immunity, the potential for a “twindemic” with a flu/COVID onslaught, and underuse of lifesaving vaccines and treatments.

Variants loom/waning immunity

Omicron variant BA.5 still makes up about 80% of infections in the United States, followed by BA4.6, according to the CDC, but other subvariants are emerging and showing signs of resistance to current antiviral treatments.

Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in San Diego, said about COVID this fall: “There will be another wave, magnitude unknown.”

He said subvariants XBB and BQ.1.1 “have extreme levels of immune evasion and both could pose a challenge,” explaining that XBB is more likely to cause trouble than BQ.1.1 because it is even more resistant to natural or vaccine-induced immunity.

Dr. Topol pointed to new research on those variants in a preprint posted on bioRxiv. The authors’ conclusion: “These results suggest that current herd immunity and BA.5 vaccine boosters may not provide sufficiently broad protection against infection.”

Another variant to watch, some experts say, is Omicron subvariant BA.2.75.2, which has shown resistance to antiviral treatments. It is also growing at a rather alarming rate, says Michael Sweat, PhD, director of the Medical University of South Carolina Center for Global Health in Charleston. That subvariant currently makes up under 2% of U.S. cases but has spread to at least 55 countries and 43 U.S. states after first appearing at the end of last year globally and in mid-June in the United States.

A non–peer-reviewed preprint study from Sweden found that the variant in blood samples was neutralized on average “at titers approximately 6.5 times lower than BA.5, making BA.2.75.2 the most [neutralization-resistant] variant evaluated to date.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology at University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, said in an interview the U.S. waves often follow Europe’s, and Europe has seen a recent spike in cases and hospitalizations not related to Omicron subvariants, but to weather changes, waning immunity, and changes in behavior.

The World Health Organization reported on Oct. 5 that, while cases were down in every other region of the world, Europe’s numbers stand out, with an 8% increase in cases from the week before.

Dr. Jetelina cited events such as Oktoberfest in Germany, which ended in the first week of October after drawing nearly 6 million people over 2 weeks, as a potential contributor, and people heading indoors as weather patterns change in Europe.

Ali Mokdad, PhD, chief strategy officer for population health at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview he is less worried about the documented variants we know about than he is about the potential for a new immune-escape variety yet to emerge.

“Right now we know the Chinese are gearing up to open up the country, and because they have low immunity and little infection, we expect in China there will be a lot of spread of Omicron,” he said. “It’s possible because of the number of infections we could see a new variant.”

Dr. Mokdad said waning immunity could also leave populations vulnerable to variants.

“Even if you get infected, after about 5 months, you’re susceptible again. Remember, most of the infections from Omicron happened in January or February 2022, and we had two waves after that,” he said.

The new bivalent vaccines tweaked to target some Omicron variants will help, Dr. Mokdad said, but he noted, “people are very reluctant to take it.”

Jennifer Nuzzo, DrPH, professor of epidemiology and director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University, Providence, R.I., worries that in the United States we have less ability this year to track variants as funding has receded for testing kits and testing sites. Most people are testing at home – which doesn’t show up in the numbers – and the United States is relying more on other countries’ data to spot trends.

“I think we’re just going to have less visibility into the circulation of this virus,” she said in an interview.

‘Twindemic’: COVID and flu

Dr. Jetelina noted Australia and New Zealand just wrapped up a flu season that saw flu numbers returning to normal after a sharp drop in the last 2 years, and North America typically follows suit.

“We do expect flu will be here in the United States and probably at levels that we saw prepandemic. We’re all holding our breath to see how our health systems hold up with COVID-19 and flu. We haven’t really experienced that yet,” she said.

There is some disagreement, however, about the possibility of a so-called “twindemic” of influenza and COVID.

Richard Webby, PhD, an infectious disease specialist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, said in an interview he thinks the possibility of both viruses spiking at the same time is unlikely.

“That’s not to say we won’t get flu and COVID activity in the same winter,” he explained, “but I think both roaring at the same time is unlikely.”

As an indicator, he said, at the beginning of the flu season last year in the Northern Hemisphere, flu activity started to pick up, but when the Omicron variant came along, “flu just wasn’t able to compete in that same environment and flu numbers dropped right off.” Previous literature suggests that when one virus is spiking it’s hard for another respiratory virus to take hold.

Vaccine, treatment underuse

Another threat is vaccines, boosters, and treatments sitting on shelves.

Dr. Sweat referred to frustration with vaccine uptake that seems to be “frozen in amber.”

As of Oct. 4, only 5.3% of people in the United States who were eligible had received the updated booster launched in early September.

Dr. Nuzzo said boosters for people at least 65 years old will be key to severity of COVID this season.

“I think that’s probably the biggest factor going into the fall and winter,” she said.

Only 38% of people at least 50 years old and 45% of those at least 65 years old had gotten a second booster as of early October.

“If we do nothing else, we have to increase booster uptake in that group,” Dr. Nuzzo said.

She said the treatment nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid, Pfizer) for treating mild to moderate COVID-19 in patients at high risk for severe disease is greatly underused, often because providers aren’t prescribing it because they don’t think it helps, are worried about drug interactions, or are worried about its “rebound” effect.

Dr. Nuzzo urged greater use of the drug and education on how to manage drug interactions.

“We have very strong data that it does help keep people out of hospital. Sure, there may be a rebound, but that pales in comparison to the risk of being hospitalized,” she said.

Calm COVID season?

Not all predictions are dire. There is another little-talked-about scenario, Dr. Sweat said – that we could be in for a calm COVID season, and those who seem to be only mildly concerned about COVID may find those thoughts justified in the numbers.

Omicron blew through with such strength, he noted, that it may have left wide immunity in its wake. Because variants seem to be staying in the Omicron family, that may signal optimism.

“If the next variant is a descendant of the Omicron lineage, I would suspect that all these people who just got infected will have some protection, not perfect, but quite a bit of protection,” Dr. Sweat said.

Dr. Topol, Dr. Nuzzo, Dr. Sweat, Dr. Webby, Dr. Mokdad, and Dr. Jetelina reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MD and APP-only care benefit patients in the ED

A provider-only patient care protocol was safe and efficient for delivery of emergency department care in response to pandemic-related staff shortages, based on data from nearly 3,000 patients.

The COVID-19 pandemic sparked a shortage of health care personnel, according to Tanveer Gaibi, MD, of INOVA Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Va., and colleagues. To help manage these challenges, the INOVA emergency department developed a Provider-Only Patients (POP) protocol for patients who required minimal nursing care.

In a study presented at the American College of Emergency Physicians 2022 Scientific Assembly, the researchers reported the outcomes of a cohort of patients with suspected COVID-19 who were treated in the emergency department using the POP protocol between Dec. 1, 2021, and Jan. 15, 2022. The patients ranged in age from 21 to 64, and all presented with COVID-19-related complaints, with an Emergency Severity Index (ESI) of 4 or 5, with 1 being the most urgent and 5 being the least urgent.

Patients were triaged by a physician or nurse to determine POP status. The researchers reviewed data from a total of 640 patients treated via the POP protocol and 2,386 patients who were not POP with ESI of 4 or 5.

Overall, the mean time from when a patient was initially seen by a provider to the discharge disposition was 48 minutes shorter for POP, and the mean time from discharge disposition placement to leaving the ED was 66 minutes shorter. None of the POP-protocol patients were readmitted within 72 hours of discharge. The researchers estimated that the 640 patients in the POP protocol saved approximately 1892.27 hours of nursing and 705.1 provider hours during the study period, and no additional physician hours or advanced-practice provider hours were needed.

The study findings suggest that POP holds up as a safe, efficient, and effective process that can reduce discharge length of stay and provider to disposition times. Although more research is needed, the POP model also may be considered to address staffing challenges unrelated to the pandemic, the researchers concluded.

“This study was conducted at [a] time when our emergency department was experiencing a sudden and disproportionate increase in volume related to the Omicron variant of COVID-19,” Dr. Gaibi told this news organization. “This novel process was developed by brainstorming untested ways of managing this increased demand. The research study was a natural outcome once the process was implemented,” he said.

“Once barriers to implementing this process were overcome, we were not surprised by the results,” Dr. Gaibi said. “Subtracting at the time for nursing process was anticipated to shorten cycle times.”

The clinical implications of POP relate to generalizability outside of the pandemic setting, Dr. Gaibi noted. “We anticipate that POP could be used for patients with minor complaints to greatly shorten their time in the emergency department,” he said.

“Potential barriers to the generalized use of POP relate, in part, to local administrative barriers related to nursing assessments,” Dr. Gaibi explained. “Further, POP patients should be simple and require little or no testing. Keeping to this strict definition of the provider-only patient may be a pitfall in terms of its hard wiring,” he added.

Looking ahead, more research is needed to study POP in ED patients with minor complaints not necessarily related to COVID-19, Dr. Gaibi said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A provider-only patient care protocol was safe and efficient for delivery of emergency department care in response to pandemic-related staff shortages, based on data from nearly 3,000 patients.

The COVID-19 pandemic sparked a shortage of health care personnel, according to Tanveer Gaibi, MD, of INOVA Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Va., and colleagues. To help manage these challenges, the INOVA emergency department developed a Provider-Only Patients (POP) protocol for patients who required minimal nursing care.

In a study presented at the American College of Emergency Physicians 2022 Scientific Assembly, the researchers reported the outcomes of a cohort of patients with suspected COVID-19 who were treated in the emergency department using the POP protocol between Dec. 1, 2021, and Jan. 15, 2022. The patients ranged in age from 21 to 64, and all presented with COVID-19-related complaints, with an Emergency Severity Index (ESI) of 4 or 5, with 1 being the most urgent and 5 being the least urgent.

Patients were triaged by a physician or nurse to determine POP status. The researchers reviewed data from a total of 640 patients treated via the POP protocol and 2,386 patients who were not POP with ESI of 4 or 5.

Overall, the mean time from when a patient was initially seen by a provider to the discharge disposition was 48 minutes shorter for POP, and the mean time from discharge disposition placement to leaving the ED was 66 minutes shorter. None of the POP-protocol patients were readmitted within 72 hours of discharge. The researchers estimated that the 640 patients in the POP protocol saved approximately 1892.27 hours of nursing and 705.1 provider hours during the study period, and no additional physician hours or advanced-practice provider hours were needed.

The study findings suggest that POP holds up as a safe, efficient, and effective process that can reduce discharge length of stay and provider to disposition times. Although more research is needed, the POP model also may be considered to address staffing challenges unrelated to the pandemic, the researchers concluded.

“This study was conducted at [a] time when our emergency department was experiencing a sudden and disproportionate increase in volume related to the Omicron variant of COVID-19,” Dr. Gaibi told this news organization. “This novel process was developed by brainstorming untested ways of managing this increased demand. The research study was a natural outcome once the process was implemented,” he said.

“Once barriers to implementing this process were overcome, we were not surprised by the results,” Dr. Gaibi said. “Subtracting at the time for nursing process was anticipated to shorten cycle times.”

The clinical implications of POP relate to generalizability outside of the pandemic setting, Dr. Gaibi noted. “We anticipate that POP could be used for patients with minor complaints to greatly shorten their time in the emergency department,” he said.

“Potential barriers to the generalized use of POP relate, in part, to local administrative barriers related to nursing assessments,” Dr. Gaibi explained. “Further, POP patients should be simple and require little or no testing. Keeping to this strict definition of the provider-only patient may be a pitfall in terms of its hard wiring,” he added.

Looking ahead, more research is needed to study POP in ED patients with minor complaints not necessarily related to COVID-19, Dr. Gaibi said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A provider-only patient care protocol was safe and efficient for delivery of emergency department care in response to pandemic-related staff shortages, based on data from nearly 3,000 patients.

The COVID-19 pandemic sparked a shortage of health care personnel, according to Tanveer Gaibi, MD, of INOVA Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Va., and colleagues. To help manage these challenges, the INOVA emergency department developed a Provider-Only Patients (POP) protocol for patients who required minimal nursing care.

In a study presented at the American College of Emergency Physicians 2022 Scientific Assembly, the researchers reported the outcomes of a cohort of patients with suspected COVID-19 who were treated in the emergency department using the POP protocol between Dec. 1, 2021, and Jan. 15, 2022. The patients ranged in age from 21 to 64, and all presented with COVID-19-related complaints, with an Emergency Severity Index (ESI) of 4 or 5, with 1 being the most urgent and 5 being the least urgent.

Patients were triaged by a physician or nurse to determine POP status. The researchers reviewed data from a total of 640 patients treated via the POP protocol and 2,386 patients who were not POP with ESI of 4 or 5.

Overall, the mean time from when a patient was initially seen by a provider to the discharge disposition was 48 minutes shorter for POP, and the mean time from discharge disposition placement to leaving the ED was 66 minutes shorter. None of the POP-protocol patients were readmitted within 72 hours of discharge. The researchers estimated that the 640 patients in the POP protocol saved approximately 1892.27 hours of nursing and 705.1 provider hours during the study period, and no additional physician hours or advanced-practice provider hours were needed.

The study findings suggest that POP holds up as a safe, efficient, and effective process that can reduce discharge length of stay and provider to disposition times. Although more research is needed, the POP model also may be considered to address staffing challenges unrelated to the pandemic, the researchers concluded.

“This study was conducted at [a] time when our emergency department was experiencing a sudden and disproportionate increase in volume related to the Omicron variant of COVID-19,” Dr. Gaibi told this news organization. “This novel process was developed by brainstorming untested ways of managing this increased demand. The research study was a natural outcome once the process was implemented,” he said.

“Once barriers to implementing this process were overcome, we were not surprised by the results,” Dr. Gaibi said. “Subtracting at the time for nursing process was anticipated to shorten cycle times.”

The clinical implications of POP relate to generalizability outside of the pandemic setting, Dr. Gaibi noted. “We anticipate that POP could be used for patients with minor complaints to greatly shorten their time in the emergency department,” he said.

“Potential barriers to the generalized use of POP relate, in part, to local administrative barriers related to nursing assessments,” Dr. Gaibi explained. “Further, POP patients should be simple and require little or no testing. Keeping to this strict definition of the provider-only patient may be a pitfall in terms of its hard wiring,” he added.

Looking ahead, more research is needed to study POP in ED patients with minor complaints not necessarily related to COVID-19, Dr. Gaibi said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACEP 2022

Evusheld PrEP may protect immunocompromised patients from severe COVID-19

Tixagevimab copackaged with cilgavimab (Evusheld) is a safe and effective preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in patients undergoing B-cell-depleting therapies who have poor immune response to COVID-19 vaccination and are at high risk for serious COVID-19 illness, a small, single-site study suggests.

Evusheld, the only COVID-19 PrEP option available, has Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) from the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of immunocompromised patients who may not respond sufficiently to COVID-19 vaccination and patients who’ve had a severe adverse reaction to COVID-19 vaccination.

“We report the largest real-world experience of Evusheld in this population, and our findings are encouraging,” lead study author Cassandra Calabrese, DO, rheumatologist and infectious disease specialist at Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

“Of 412 patients who received Evusheld, 12 [2.9%] developed breakthrough COVID-19, with 11 having mild courses and 1 who required hospitalization but recovered,” she added.

“Our data suggest that Evusheld PrEP, in combination with aggressive outpatient treatment of COVID-19, is likely effective in lowering risk of severe COVID in this vulnerable group.

“Practitioners who care for patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases should triage high-risk patients for Evusheld as well as rapid diagnosis and aggressive outpatient therapy if infected,” Dr. Calabrese advised.

For the study, Dr. Calabrese and colleagues at Cleveland Clinic searched the health care system pharmacy records for patients with immune‐mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) or inborn errors of humoral immunity (IEI) who met the criteria to receive Evusheld. The researchers included patients on B-cell-depleting therapies or with humoral IEI who had received at least one dose of Evusheld and were later diagnosed with COVID-19, and they excluded those treated with B-cell-depleting therapies for cancer.

EVUSHELD was well tolerated

After extracting data on COVID-19 infection, vaccination status, and outcomes, they found that, between Jan. 18 and May 28, 2022, 412 patients with IMIDs or humoral IEI received Evusheld. No deaths occurred among these patients and, overall, they tolerated the medication well.

All 12 patients who experienced breakthrough COVID-19 infection were treated with B-cell-depleting therapies. Among the 12 patients:

- Six patients developed infection 13-84 (median 19) days after receiving 150 mg/150 mg tixagevimab/cilgavimab.

- Six patients developed infection 19-72 (median of 38.5) days after either a single dose of 300 mg/300 mg or a second dose of 150 mg/150 mg.

- Eleven patients had mild illness and recovered at home; one patient was hospitalized and treated with high-flow oxygen. All cases had been vaccinated against COVID-19 (five received two vaccinations, six received three, and one received four).

- One possible serious adverse event involved a patient with COVID-19 and immune-mediated thrombocytopenia (ITP) who was hospitalized soon after receiving Evusheld with ITP flare that resolved with intravenous immunoglobulin.

Dr. Calabrese acknowledged limitations to the study, including few patients, lack of a comparator group, and the study period falling during the Omicron wave.

“Also, nine of the breakthrough cases received additional COVID-19 therapy (oral antiviral or monoclonal antibody), which falls within standard of care for this high-risk group but prevents ascribing effectiveness to individual components of the regimen,” she added.

“Evusheld is authorized for PrEP against COVID-19 in patients at high risk for severe COVID due to suboptimal vaccine responses. This includes patients receiving B-cell-depleting drugs like rituximab, and patients with inborn errors of humoral immunity,” Dr. Calabrese explained.

“It is well known that this group of patients is at very high risk for severe COVID and death, even when fully vaccinated, and it has become clear that more strategies are needed to protect this vulnerable group, including use of Evusheld as well as aggressive treatment if infected,” she added.

Evusheld not always easy to obtain

Although the medication has been available in the United States since January 2022, Dr. Calabrese said, patients may not receive it because of barriers including lack of both awareness and access.

Davey Smith, MD, professor of medicine and head of infectious diseases and global public health at the University of California San Diego, in La Jolla, said in an interview that he was not surprised by the results, but added that the study was conducted in too few patients to draw any strong conclusions or affect patient care.

“This small study that showed that breakthrough infections occurred but were generally mild, provides a small glimpse of real-world use of tixagevimab/cilgavimab as PrEP for immunocompromised persons,” said Dr. Smith, who was not involved in the study.

“In the setting of Omicron and vaccination, I would expect the same outcomes reported even without the treatment,” he added.

Dr. Smith recommends larger related randomized, controlled trials to provide clinicians with sufficient data to guide them in their patient care.

Graham Snyder, MD, associate professor in the division of infectious diseases at the University of Pittsburgh and medical director of infection prevention and hospital epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, noted that the study “adds to a quickly growing literature on the real-world benefits of tixagevimab/cilgavimab to protect vulnerable individuals with weakened immune systems from the complications of COVID-19.

“This study provides a modest addition to our understanding of the role and benefit of Evusheld,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview. “By characterizing only patients who have received Evusheld without an untreated comparison group, we can’t draw any inference about the extent of benefit the agent provided to these patients.

“Substantial data already show that this agent is effective in preventing complications of COVID-19 infection in immunocompromised individuals,” added Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the study.

“ ‘Immunocompromised’ represents a very diverse set of clinical conditions,” he said. “The research agenda should therefore focus on a more refined description of the effect in specific populations and a continued understanding of the effect of Evusheld in the context of updated vaccination strategies and changing virus ecology.”

Dr. Calabrese and her colleagues wrote that larger, controlled trials are underway.

FDA: Evusheld may not neutralize certain SARS-CoV-2 variants

“The biggest unanswered question is how Evusheld will hold up against new variants,” Dr. Calabrese said.

In an Oct. 3, 2022, update, the Food and Drug Administration released a statement about the risk of developing COVID-19 from SARS-CoV-2 variants that are not neutralized by Evusheld. The statement mentions an updated fact sheet that describes reduced protection from Evusheld against the Omicron subvariant BA.4.6, which accounted for nearly 13% of all new COVID-19 cases in the United States in the week ending Oct. 1.

There was no outside funding for the study. Dr. Smith reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Snyder said he is an unpaid adviser to an AstraZeneca observational study that’s assessing the real-world effectiveness of Evusheld.

Tixagevimab copackaged with cilgavimab (Evusheld) is a safe and effective preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in patients undergoing B-cell-depleting therapies who have poor immune response to COVID-19 vaccination and are at high risk for serious COVID-19 illness, a small, single-site study suggests.

Evusheld, the only COVID-19 PrEP option available, has Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) from the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of immunocompromised patients who may not respond sufficiently to COVID-19 vaccination and patients who’ve had a severe adverse reaction to COVID-19 vaccination.

“We report the largest real-world experience of Evusheld in this population, and our findings are encouraging,” lead study author Cassandra Calabrese, DO, rheumatologist and infectious disease specialist at Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

“Of 412 patients who received Evusheld, 12 [2.9%] developed breakthrough COVID-19, with 11 having mild courses and 1 who required hospitalization but recovered,” she added.

“Our data suggest that Evusheld PrEP, in combination with aggressive outpatient treatment of COVID-19, is likely effective in lowering risk of severe COVID in this vulnerable group.

“Practitioners who care for patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases should triage high-risk patients for Evusheld as well as rapid diagnosis and aggressive outpatient therapy if infected,” Dr. Calabrese advised.

For the study, Dr. Calabrese and colleagues at Cleveland Clinic searched the health care system pharmacy records for patients with immune‐mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) or inborn errors of humoral immunity (IEI) who met the criteria to receive Evusheld. The researchers included patients on B-cell-depleting therapies or with humoral IEI who had received at least one dose of Evusheld and were later diagnosed with COVID-19, and they excluded those treated with B-cell-depleting therapies for cancer.

EVUSHELD was well tolerated

After extracting data on COVID-19 infection, vaccination status, and outcomes, they found that, between Jan. 18 and May 28, 2022, 412 patients with IMIDs or humoral IEI received Evusheld. No deaths occurred among these patients and, overall, they tolerated the medication well.

All 12 patients who experienced breakthrough COVID-19 infection were treated with B-cell-depleting therapies. Among the 12 patients:

- Six patients developed infection 13-84 (median 19) days after receiving 150 mg/150 mg tixagevimab/cilgavimab.

- Six patients developed infection 19-72 (median of 38.5) days after either a single dose of 300 mg/300 mg or a second dose of 150 mg/150 mg.

- Eleven patients had mild illness and recovered at home; one patient was hospitalized and treated with high-flow oxygen. All cases had been vaccinated against COVID-19 (five received two vaccinations, six received three, and one received four).

- One possible serious adverse event involved a patient with COVID-19 and immune-mediated thrombocytopenia (ITP) who was hospitalized soon after receiving Evusheld with ITP flare that resolved with intravenous immunoglobulin.

Dr. Calabrese acknowledged limitations to the study, including few patients, lack of a comparator group, and the study period falling during the Omicron wave.

“Also, nine of the breakthrough cases received additional COVID-19 therapy (oral antiviral or monoclonal antibody), which falls within standard of care for this high-risk group but prevents ascribing effectiveness to individual components of the regimen,” she added.

“Evusheld is authorized for PrEP against COVID-19 in patients at high risk for severe COVID due to suboptimal vaccine responses. This includes patients receiving B-cell-depleting drugs like rituximab, and patients with inborn errors of humoral immunity,” Dr. Calabrese explained.

“It is well known that this group of patients is at very high risk for severe COVID and death, even when fully vaccinated, and it has become clear that more strategies are needed to protect this vulnerable group, including use of Evusheld as well as aggressive treatment if infected,” she added.

Evusheld not always easy to obtain

Although the medication has been available in the United States since January 2022, Dr. Calabrese said, patients may not receive it because of barriers including lack of both awareness and access.

Davey Smith, MD, professor of medicine and head of infectious diseases and global public health at the University of California San Diego, in La Jolla, said in an interview that he was not surprised by the results, but added that the study was conducted in too few patients to draw any strong conclusions or affect patient care.

“This small study that showed that breakthrough infections occurred but were generally mild, provides a small glimpse of real-world use of tixagevimab/cilgavimab as PrEP for immunocompromised persons,” said Dr. Smith, who was not involved in the study.

“In the setting of Omicron and vaccination, I would expect the same outcomes reported even without the treatment,” he added.

Dr. Smith recommends larger related randomized, controlled trials to provide clinicians with sufficient data to guide them in their patient care.

Graham Snyder, MD, associate professor in the division of infectious diseases at the University of Pittsburgh and medical director of infection prevention and hospital epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, noted that the study “adds to a quickly growing literature on the real-world benefits of tixagevimab/cilgavimab to protect vulnerable individuals with weakened immune systems from the complications of COVID-19.

“This study provides a modest addition to our understanding of the role and benefit of Evusheld,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview. “By characterizing only patients who have received Evusheld without an untreated comparison group, we can’t draw any inference about the extent of benefit the agent provided to these patients.

“Substantial data already show that this agent is effective in preventing complications of COVID-19 infection in immunocompromised individuals,” added Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the study.

“ ‘Immunocompromised’ represents a very diverse set of clinical conditions,” he said. “The research agenda should therefore focus on a more refined description of the effect in specific populations and a continued understanding of the effect of Evusheld in the context of updated vaccination strategies and changing virus ecology.”

Dr. Calabrese and her colleagues wrote that larger, controlled trials are underway.

FDA: Evusheld may not neutralize certain SARS-CoV-2 variants

“The biggest unanswered question is how Evusheld will hold up against new variants,” Dr. Calabrese said.

In an Oct. 3, 2022, update, the Food and Drug Administration released a statement about the risk of developing COVID-19 from SARS-CoV-2 variants that are not neutralized by Evusheld. The statement mentions an updated fact sheet that describes reduced protection from Evusheld against the Omicron subvariant BA.4.6, which accounted for nearly 13% of all new COVID-19 cases in the United States in the week ending Oct. 1.

There was no outside funding for the study. Dr. Smith reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Snyder said he is an unpaid adviser to an AstraZeneca observational study that’s assessing the real-world effectiveness of Evusheld.

Tixagevimab copackaged with cilgavimab (Evusheld) is a safe and effective preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in patients undergoing B-cell-depleting therapies who have poor immune response to COVID-19 vaccination and are at high risk for serious COVID-19 illness, a small, single-site study suggests.

Evusheld, the only COVID-19 PrEP option available, has Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) from the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of immunocompromised patients who may not respond sufficiently to COVID-19 vaccination and patients who’ve had a severe adverse reaction to COVID-19 vaccination.

“We report the largest real-world experience of Evusheld in this population, and our findings are encouraging,” lead study author Cassandra Calabrese, DO, rheumatologist and infectious disease specialist at Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

“Of 412 patients who received Evusheld, 12 [2.9%] developed breakthrough COVID-19, with 11 having mild courses and 1 who required hospitalization but recovered,” she added.

“Our data suggest that Evusheld PrEP, in combination with aggressive outpatient treatment of COVID-19, is likely effective in lowering risk of severe COVID in this vulnerable group.

“Practitioners who care for patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases should triage high-risk patients for Evusheld as well as rapid diagnosis and aggressive outpatient therapy if infected,” Dr. Calabrese advised.

For the study, Dr. Calabrese and colleagues at Cleveland Clinic searched the health care system pharmacy records for patients with immune‐mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) or inborn errors of humoral immunity (IEI) who met the criteria to receive Evusheld. The researchers included patients on B-cell-depleting therapies or with humoral IEI who had received at least one dose of Evusheld and were later diagnosed with COVID-19, and they excluded those treated with B-cell-depleting therapies for cancer.

EVUSHELD was well tolerated

After extracting data on COVID-19 infection, vaccination status, and outcomes, they found that, between Jan. 18 and May 28, 2022, 412 patients with IMIDs or humoral IEI received Evusheld. No deaths occurred among these patients and, overall, they tolerated the medication well.

All 12 patients who experienced breakthrough COVID-19 infection were treated with B-cell-depleting therapies. Among the 12 patients:

- Six patients developed infection 13-84 (median 19) days after receiving 150 mg/150 mg tixagevimab/cilgavimab.

- Six patients developed infection 19-72 (median of 38.5) days after either a single dose of 300 mg/300 mg or a second dose of 150 mg/150 mg.

- Eleven patients had mild illness and recovered at home; one patient was hospitalized and treated with high-flow oxygen. All cases had been vaccinated against COVID-19 (five received two vaccinations, six received three, and one received four).

- One possible serious adverse event involved a patient with COVID-19 and immune-mediated thrombocytopenia (ITP) who was hospitalized soon after receiving Evusheld with ITP flare that resolved with intravenous immunoglobulin.

Dr. Calabrese acknowledged limitations to the study, including few patients, lack of a comparator group, and the study period falling during the Omicron wave.

“Also, nine of the breakthrough cases received additional COVID-19 therapy (oral antiviral or monoclonal antibody), which falls within standard of care for this high-risk group but prevents ascribing effectiveness to individual components of the regimen,” she added.

“Evusheld is authorized for PrEP against COVID-19 in patients at high risk for severe COVID due to suboptimal vaccine responses. This includes patients receiving B-cell-depleting drugs like rituximab, and patients with inborn errors of humoral immunity,” Dr. Calabrese explained.

“It is well known that this group of patients is at very high risk for severe COVID and death, even when fully vaccinated, and it has become clear that more strategies are needed to protect this vulnerable group, including use of Evusheld as well as aggressive treatment if infected,” she added.

Evusheld not always easy to obtain

Although the medication has been available in the United States since January 2022, Dr. Calabrese said, patients may not receive it because of barriers including lack of both awareness and access.

Davey Smith, MD, professor of medicine and head of infectious diseases and global public health at the University of California San Diego, in La Jolla, said in an interview that he was not surprised by the results, but added that the study was conducted in too few patients to draw any strong conclusions or affect patient care.

“This small study that showed that breakthrough infections occurred but were generally mild, provides a small glimpse of real-world use of tixagevimab/cilgavimab as PrEP for immunocompromised persons,” said Dr. Smith, who was not involved in the study.

“In the setting of Omicron and vaccination, I would expect the same outcomes reported even without the treatment,” he added.

Dr. Smith recommends larger related randomized, controlled trials to provide clinicians with sufficient data to guide them in their patient care.

Graham Snyder, MD, associate professor in the division of infectious diseases at the University of Pittsburgh and medical director of infection prevention and hospital epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, noted that the study “adds to a quickly growing literature on the real-world benefits of tixagevimab/cilgavimab to protect vulnerable individuals with weakened immune systems from the complications of COVID-19.

“This study provides a modest addition to our understanding of the role and benefit of Evusheld,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview. “By characterizing only patients who have received Evusheld without an untreated comparison group, we can’t draw any inference about the extent of benefit the agent provided to these patients.