User login

Psychiatrists’ income, wealth gain ground despite COVID-19 challenges

Although many physicians endured pandemic-related income struggles in 2020, psychiatrists are doing fairly well with building their nest egg and paying down debt, according to the Medscape Psychiatrist Wealth and Debt Report 2021.

Surprisingly, despite COVID-19, psychiatrists’ income improved somewhat this year – from $268,000 in 2020 to $275,000 in 2021.

However, that still puts psychiatrists among the lower-paid specialists.

The highest-paying specialty is plastic surgery ($526,000), followed by orthopedics and orthopedic surgery ($511,000) and cardiology ($459,000), according to the overall Medscape Physician Wealth and Debt Report 2021. The report is based on responses from nearly 18,000 physicians in 29 specialties. All were surveyed between Oct. 6, 2020, and Feb. 11, 2021.

Psychiatrists’ overall wealth gained some ground over the past year, with 40% reporting a net worth of $1 million to $5 million this year – up from 38% last year. Just 6% of psychiatrists have a net worth north of $5 million, up slightly from 5% last year.

Keeping up with bills

based in St. Louis Park, Minn. He noted that the rise in the stock market also played a role, with the S&P 500 finishing the year up over 18%.

“I’ve seen clients accumulate cash, which has added to their net worth. They cut back on spending because they were worried about big declines in income and also because there was simply less to spend money on,” Dr. Greenwald said.

The percentage of psychiatrists with a net worth under $500,000 decreased from 37% last year to 32% this year. Psychiatry is still among the specialties reporting a high percentage of members with net worth below $500,000.

But gender matters. Earnings overall are higher for male than female psychiatrists, and that is reflected in net worth. Fewer female than male psychiatrists are worth more than $5 million (4% vs. 7%), and more female psychiatrists have a net worth of less than $500,000 (41% vs. 26%).

As in prior years, most psychiatrists are paying down a home mortgage on their primary residence (66%). Psychiatrists’ mortgage payments span a wide range, from less than $100,000 (23%) to more than $500,000 (15%). However, 27% report having no mortgage.

Mortgage aside, other top expenses or debts for psychiatrists are car loan payments (36%), paying off college and medical school debt (26%), credit card debt (25%), and medical expenses for self or loved ones (19%).

Other expenses include college tuition for children (16%), car lease payments (14%), mortgage on a second home (13%), private-school tuition for a child (12%), and child care (12%).

Despite some financially challenging months, the vast majority of psychiatrists (94%) kept up with paying their bills.

That’s better than what much of America experienced. According to a U.S. Census Bureau survey conducted last July, roughly 25% of adults missed a mortgage or rent payment because of COVID-related difficulties.

About half of psychiatrists pool their income to pay for bills. One-quarter do not have joint accounts with a spouse or partner.

Spender or saver?

About three-quarters of psychiatrists continued to spend as usual in 2020. About one-quarter took significant steps to lower their expenses, such as refinancing their home or moving to a less costly home.

In line with prior Medscape surveys, about half of psychiatrists have a general idea of how much they spend and on what, but they do not track or formalize it.

According to a recent survey by Intuit, only 35% of Americans say they know how much they spent last month. Viewed by age, 27% of millennials, 34% of Gen Xers, and 46% of baby boomers knew how much they spent.

Many psychiatrists have a higher-than-average number of credit cards; 42% have at least five. By comparison, the average American has four.

Savings was mixed for psychiatrists this past year; 61% put in the same amount or more each month into their 401(k) plans, but 33% put in less money, compared with last year.

For taxable savings accounts, half of psychiatrists put the same amount or more into after-tax accounts – but 22% put in less money, compared with last year. Another one-quarter did not use these savings accounts at all.

The percentage of psychiatrists who experienced losses because of practice problems rose from 6% to 9% in the past year. Much of that was likely because of COVID. However, about the same percentage reported no financial losses this year (76%), compared with last year (75%).

The vast majority of psychiatrists report living within or below their means; only 5% live above their means.

“There are certainly folks who believe that, as long as they pay off their credit card each month and contribute to their 401(k) enough to get their employer match, they’re doing okay,” Dr. Greenwald said.

However, “living within one’s means is having a 3-6 months’ emergency fund; saving at least 20% of gross income toward retirement; adequately funding 529 college accounts; and, for younger docs, paying down high-interest-rate debt at a good clip,” he added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although many physicians endured pandemic-related income struggles in 2020, psychiatrists are doing fairly well with building their nest egg and paying down debt, according to the Medscape Psychiatrist Wealth and Debt Report 2021.

Surprisingly, despite COVID-19, psychiatrists’ income improved somewhat this year – from $268,000 in 2020 to $275,000 in 2021.

However, that still puts psychiatrists among the lower-paid specialists.

The highest-paying specialty is plastic surgery ($526,000), followed by orthopedics and orthopedic surgery ($511,000) and cardiology ($459,000), according to the overall Medscape Physician Wealth and Debt Report 2021. The report is based on responses from nearly 18,000 physicians in 29 specialties. All were surveyed between Oct. 6, 2020, and Feb. 11, 2021.

Psychiatrists’ overall wealth gained some ground over the past year, with 40% reporting a net worth of $1 million to $5 million this year – up from 38% last year. Just 6% of psychiatrists have a net worth north of $5 million, up slightly from 5% last year.

Keeping up with bills

based in St. Louis Park, Minn. He noted that the rise in the stock market also played a role, with the S&P 500 finishing the year up over 18%.

“I’ve seen clients accumulate cash, which has added to their net worth. They cut back on spending because they were worried about big declines in income and also because there was simply less to spend money on,” Dr. Greenwald said.

The percentage of psychiatrists with a net worth under $500,000 decreased from 37% last year to 32% this year. Psychiatry is still among the specialties reporting a high percentage of members with net worth below $500,000.

But gender matters. Earnings overall are higher for male than female psychiatrists, and that is reflected in net worth. Fewer female than male psychiatrists are worth more than $5 million (4% vs. 7%), and more female psychiatrists have a net worth of less than $500,000 (41% vs. 26%).

As in prior years, most psychiatrists are paying down a home mortgage on their primary residence (66%). Psychiatrists’ mortgage payments span a wide range, from less than $100,000 (23%) to more than $500,000 (15%). However, 27% report having no mortgage.

Mortgage aside, other top expenses or debts for psychiatrists are car loan payments (36%), paying off college and medical school debt (26%), credit card debt (25%), and medical expenses for self or loved ones (19%).

Other expenses include college tuition for children (16%), car lease payments (14%), mortgage on a second home (13%), private-school tuition for a child (12%), and child care (12%).

Despite some financially challenging months, the vast majority of psychiatrists (94%) kept up with paying their bills.

That’s better than what much of America experienced. According to a U.S. Census Bureau survey conducted last July, roughly 25% of adults missed a mortgage or rent payment because of COVID-related difficulties.

About half of psychiatrists pool their income to pay for bills. One-quarter do not have joint accounts with a spouse or partner.

Spender or saver?

About three-quarters of psychiatrists continued to spend as usual in 2020. About one-quarter took significant steps to lower their expenses, such as refinancing their home or moving to a less costly home.

In line with prior Medscape surveys, about half of psychiatrists have a general idea of how much they spend and on what, but they do not track or formalize it.

According to a recent survey by Intuit, only 35% of Americans say they know how much they spent last month. Viewed by age, 27% of millennials, 34% of Gen Xers, and 46% of baby boomers knew how much they spent.

Many psychiatrists have a higher-than-average number of credit cards; 42% have at least five. By comparison, the average American has four.

Savings was mixed for psychiatrists this past year; 61% put in the same amount or more each month into their 401(k) plans, but 33% put in less money, compared with last year.

For taxable savings accounts, half of psychiatrists put the same amount or more into after-tax accounts – but 22% put in less money, compared with last year. Another one-quarter did not use these savings accounts at all.

The percentage of psychiatrists who experienced losses because of practice problems rose from 6% to 9% in the past year. Much of that was likely because of COVID. However, about the same percentage reported no financial losses this year (76%), compared with last year (75%).

The vast majority of psychiatrists report living within or below their means; only 5% live above their means.

“There are certainly folks who believe that, as long as they pay off their credit card each month and contribute to their 401(k) enough to get their employer match, they’re doing okay,” Dr. Greenwald said.

However, “living within one’s means is having a 3-6 months’ emergency fund; saving at least 20% of gross income toward retirement; adequately funding 529 college accounts; and, for younger docs, paying down high-interest-rate debt at a good clip,” he added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although many physicians endured pandemic-related income struggles in 2020, psychiatrists are doing fairly well with building their nest egg and paying down debt, according to the Medscape Psychiatrist Wealth and Debt Report 2021.

Surprisingly, despite COVID-19, psychiatrists’ income improved somewhat this year – from $268,000 in 2020 to $275,000 in 2021.

However, that still puts psychiatrists among the lower-paid specialists.

The highest-paying specialty is plastic surgery ($526,000), followed by orthopedics and orthopedic surgery ($511,000) and cardiology ($459,000), according to the overall Medscape Physician Wealth and Debt Report 2021. The report is based on responses from nearly 18,000 physicians in 29 specialties. All were surveyed between Oct. 6, 2020, and Feb. 11, 2021.

Psychiatrists’ overall wealth gained some ground over the past year, with 40% reporting a net worth of $1 million to $5 million this year – up from 38% last year. Just 6% of psychiatrists have a net worth north of $5 million, up slightly from 5% last year.

Keeping up with bills

based in St. Louis Park, Minn. He noted that the rise in the stock market also played a role, with the S&P 500 finishing the year up over 18%.

“I’ve seen clients accumulate cash, which has added to their net worth. They cut back on spending because they were worried about big declines in income and also because there was simply less to spend money on,” Dr. Greenwald said.

The percentage of psychiatrists with a net worth under $500,000 decreased from 37% last year to 32% this year. Psychiatry is still among the specialties reporting a high percentage of members with net worth below $500,000.

But gender matters. Earnings overall are higher for male than female psychiatrists, and that is reflected in net worth. Fewer female than male psychiatrists are worth more than $5 million (4% vs. 7%), and more female psychiatrists have a net worth of less than $500,000 (41% vs. 26%).

As in prior years, most psychiatrists are paying down a home mortgage on their primary residence (66%). Psychiatrists’ mortgage payments span a wide range, from less than $100,000 (23%) to more than $500,000 (15%). However, 27% report having no mortgage.

Mortgage aside, other top expenses or debts for psychiatrists are car loan payments (36%), paying off college and medical school debt (26%), credit card debt (25%), and medical expenses for self or loved ones (19%).

Other expenses include college tuition for children (16%), car lease payments (14%), mortgage on a second home (13%), private-school tuition for a child (12%), and child care (12%).

Despite some financially challenging months, the vast majority of psychiatrists (94%) kept up with paying their bills.

That’s better than what much of America experienced. According to a U.S. Census Bureau survey conducted last July, roughly 25% of adults missed a mortgage or rent payment because of COVID-related difficulties.

About half of psychiatrists pool their income to pay for bills. One-quarter do not have joint accounts with a spouse or partner.

Spender or saver?

About three-quarters of psychiatrists continued to spend as usual in 2020. About one-quarter took significant steps to lower their expenses, such as refinancing their home or moving to a less costly home.

In line with prior Medscape surveys, about half of psychiatrists have a general idea of how much they spend and on what, but they do not track or formalize it.

According to a recent survey by Intuit, only 35% of Americans say they know how much they spent last month. Viewed by age, 27% of millennials, 34% of Gen Xers, and 46% of baby boomers knew how much they spent.

Many psychiatrists have a higher-than-average number of credit cards; 42% have at least five. By comparison, the average American has four.

Savings was mixed for psychiatrists this past year; 61% put in the same amount or more each month into their 401(k) plans, but 33% put in less money, compared with last year.

For taxable savings accounts, half of psychiatrists put the same amount or more into after-tax accounts – but 22% put in less money, compared with last year. Another one-quarter did not use these savings accounts at all.

The percentage of psychiatrists who experienced losses because of practice problems rose from 6% to 9% in the past year. Much of that was likely because of COVID. However, about the same percentage reported no financial losses this year (76%), compared with last year (75%).

The vast majority of psychiatrists report living within or below their means; only 5% live above their means.

“There are certainly folks who believe that, as long as they pay off their credit card each month and contribute to their 401(k) enough to get their employer match, they’re doing okay,” Dr. Greenwald said.

However, “living within one’s means is having a 3-6 months’ emergency fund; saving at least 20% of gross income toward retirement; adequately funding 529 college accounts; and, for younger docs, paying down high-interest-rate debt at a good clip,” he added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and COVID: New cases rise to winter levels

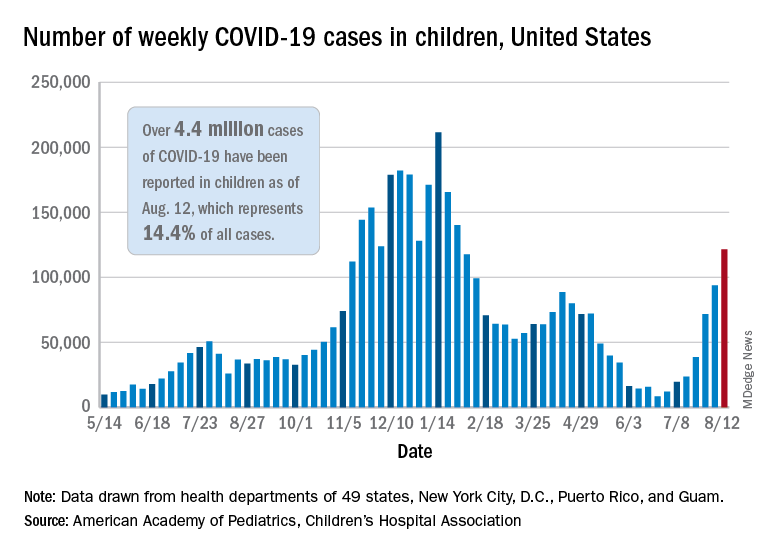

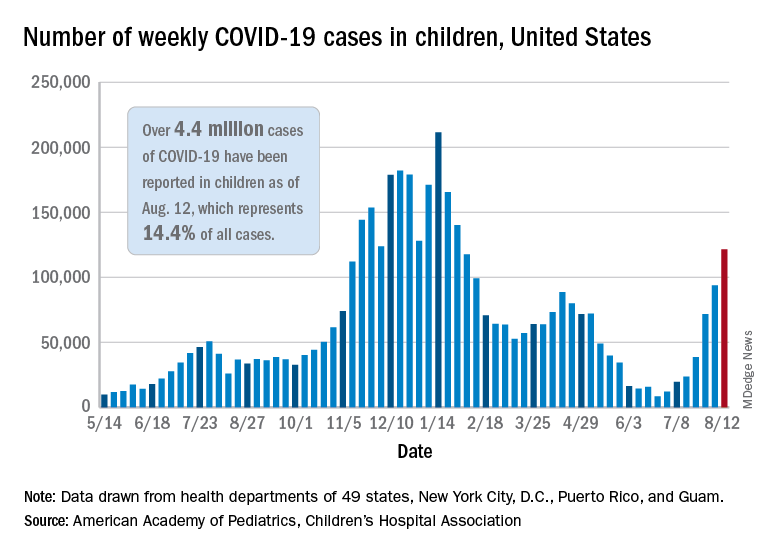

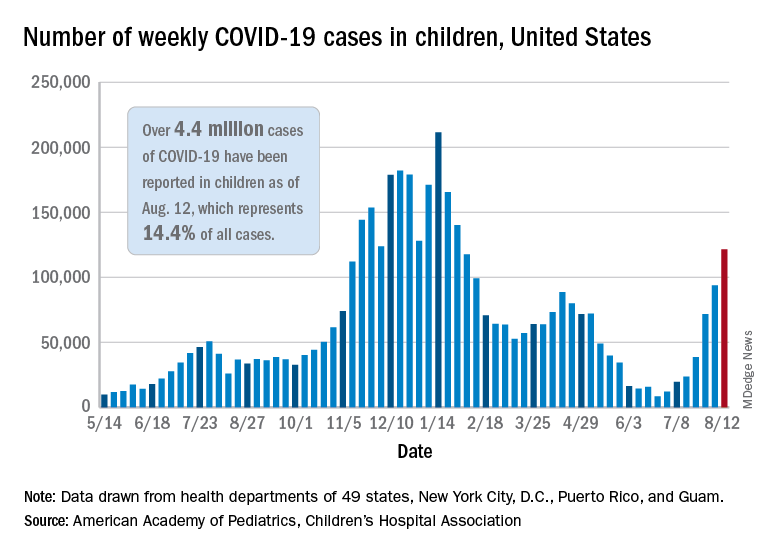

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children topped 100,000 for the first time since early February, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVD-19 report. The recent surge in child COVID has also brought a record high in hospitalizations and shortages of pediatric ICU beds in some areas.

The 121,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 1,400% since June 18-24, when the weekly tally was just 8,447 and at its lowest point in over a year, the AAP/CHA data show.

On the vaccination front in the last week (Aug. 10-16), vaccine initiation for 12- to 17-year-olds was fairly robust but still down slightly, compared with the previous week. Just over 402,000 children aged 12-15 years received a first vaccination, which was down slightly from 411,000 the week before but still higher than any of the 6 weeks from June 22 to Aug. 2, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccinations were down by a similar margin for 15- to-17-year-olds.

Over 10.9 million children aged 12-17 have had at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine administered, of whom 8.1 million are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 12-15 years, 44.5% have gotten at least one dose and 31.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding figures of 53.9% and 42.5% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The number of COVID-19 cases reported in children since the start of the pandemic is up to 4.4 million, which makes up 14.4% of all cases in the United States, the AAP and CHA said. Other cumulative figures through Aug. 12 include almost 18,000 hospitalizations – reported by 23 states and New York City – and 378 deaths – reported by 43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

In the latest edition of their ongoing report, compiled using state data since the summer of 2020, the two groups noted that, “in the summer of 2021, some states have revised cases counts previously reported, begun reporting less frequently, or dropped metrics previously reported.” Among those states are Nebraska, which shut down its online COVID dashboard in late June, and Alabama, which stopped reporting cumulative cases and deaths after July 29.

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children topped 100,000 for the first time since early February, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVD-19 report. The recent surge in child COVID has also brought a record high in hospitalizations and shortages of pediatric ICU beds in some areas.

The 121,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 1,400% since June 18-24, when the weekly tally was just 8,447 and at its lowest point in over a year, the AAP/CHA data show.

On the vaccination front in the last week (Aug. 10-16), vaccine initiation for 12- to 17-year-olds was fairly robust but still down slightly, compared with the previous week. Just over 402,000 children aged 12-15 years received a first vaccination, which was down slightly from 411,000 the week before but still higher than any of the 6 weeks from June 22 to Aug. 2, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccinations were down by a similar margin for 15- to-17-year-olds.

Over 10.9 million children aged 12-17 have had at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine administered, of whom 8.1 million are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 12-15 years, 44.5% have gotten at least one dose and 31.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding figures of 53.9% and 42.5% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The number of COVID-19 cases reported in children since the start of the pandemic is up to 4.4 million, which makes up 14.4% of all cases in the United States, the AAP and CHA said. Other cumulative figures through Aug. 12 include almost 18,000 hospitalizations – reported by 23 states and New York City – and 378 deaths – reported by 43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

In the latest edition of their ongoing report, compiled using state data since the summer of 2020, the two groups noted that, “in the summer of 2021, some states have revised cases counts previously reported, begun reporting less frequently, or dropped metrics previously reported.” Among those states are Nebraska, which shut down its online COVID dashboard in late June, and Alabama, which stopped reporting cumulative cases and deaths after July 29.

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children topped 100,000 for the first time since early February, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVD-19 report. The recent surge in child COVID has also brought a record high in hospitalizations and shortages of pediatric ICU beds in some areas.

The 121,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 1,400% since June 18-24, when the weekly tally was just 8,447 and at its lowest point in over a year, the AAP/CHA data show.

On the vaccination front in the last week (Aug. 10-16), vaccine initiation for 12- to 17-year-olds was fairly robust but still down slightly, compared with the previous week. Just over 402,000 children aged 12-15 years received a first vaccination, which was down slightly from 411,000 the week before but still higher than any of the 6 weeks from June 22 to Aug. 2, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccinations were down by a similar margin for 15- to-17-year-olds.

Over 10.9 million children aged 12-17 have had at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine administered, of whom 8.1 million are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 12-15 years, 44.5% have gotten at least one dose and 31.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding figures of 53.9% and 42.5% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The number of COVID-19 cases reported in children since the start of the pandemic is up to 4.4 million, which makes up 14.4% of all cases in the United States, the AAP and CHA said. Other cumulative figures through Aug. 12 include almost 18,000 hospitalizations – reported by 23 states and New York City – and 378 deaths – reported by 43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

In the latest edition of their ongoing report, compiled using state data since the summer of 2020, the two groups noted that, “in the summer of 2021, some states have revised cases counts previously reported, begun reporting less frequently, or dropped metrics previously reported.” Among those states are Nebraska, which shut down its online COVID dashboard in late June, and Alabama, which stopped reporting cumulative cases and deaths after July 29.

COVID-19 hospitalizations for 30- to 39-year-olds hit record high

Hospitals are reporting record numbers of COVID-19 patients in their 30s, largely because of the contagious Delta variant, according to The Wall Street Journal.

The rate of new hospitalizations for ages 30-39 reached 2.5 per 100,000 people last week, according to the latest CDC data, which is up from the previous peak of 2 per 100,000 people in January.

What’s more, new hospital admissions for patients in their 30s reached an average of 1,113 a day during the last week, which was up from 908 the week before.

“It means Delta is really bad,” James Lawler, MD, an infectious disease doctor and codirector of the Global Center for Health Security at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, told the newspaper.

People in the age group mostly avoided hospitalization throughout the pandemic because of their relatively good health and young age, the newspaper reported. But in recent weeks, those between ages 30 and 39 are contracting the coronavirus because of their active lifestyle – for many in their 30s, these are prime years for working, parenting, and socializing.

Hospitalizations are mostly among unvaccinated adults, according to the Wall Street Journal. Nationally, less than half of those ages 25-39 are fully vaccinated, compared with 61% of all adults, according to CDC data updated Sunday.

“It loves social mobility,” James Fiorica, MD, chief medical officer of Sarasota Memorial Health Care System in Florida, told the newspaper.

“An unvaccinated 30-year-old can be a perfect carrier,” he said.

On top of that, COVID-19 patients in their 30s are arriving at hospitals with more severe disease than in earlier waves, the Journal reported. At the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences hospital, for instance, doctors are now monitoring younger patients daily with a scoring system for possible organ failure. That wasn’t necessary earlier in the pandemic for people in their 30s.

“This age group pretty much went unscathed,” Nikhil Meena, MD, director of the hospital’s Medical Intensive Care Unit, told the newspaper.

Now, he said, “they’re all out there doing their thing and getting infected and getting sick enough to be in this hospital.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Hospitals are reporting record numbers of COVID-19 patients in their 30s, largely because of the contagious Delta variant, according to The Wall Street Journal.

The rate of new hospitalizations for ages 30-39 reached 2.5 per 100,000 people last week, according to the latest CDC data, which is up from the previous peak of 2 per 100,000 people in January.

What’s more, new hospital admissions for patients in their 30s reached an average of 1,113 a day during the last week, which was up from 908 the week before.

“It means Delta is really bad,” James Lawler, MD, an infectious disease doctor and codirector of the Global Center for Health Security at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, told the newspaper.

People in the age group mostly avoided hospitalization throughout the pandemic because of their relatively good health and young age, the newspaper reported. But in recent weeks, those between ages 30 and 39 are contracting the coronavirus because of their active lifestyle – for many in their 30s, these are prime years for working, parenting, and socializing.

Hospitalizations are mostly among unvaccinated adults, according to the Wall Street Journal. Nationally, less than half of those ages 25-39 are fully vaccinated, compared with 61% of all adults, according to CDC data updated Sunday.

“It loves social mobility,” James Fiorica, MD, chief medical officer of Sarasota Memorial Health Care System in Florida, told the newspaper.

“An unvaccinated 30-year-old can be a perfect carrier,” he said.

On top of that, COVID-19 patients in their 30s are arriving at hospitals with more severe disease than in earlier waves, the Journal reported. At the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences hospital, for instance, doctors are now monitoring younger patients daily with a scoring system for possible organ failure. That wasn’t necessary earlier in the pandemic for people in their 30s.

“This age group pretty much went unscathed,” Nikhil Meena, MD, director of the hospital’s Medical Intensive Care Unit, told the newspaper.

Now, he said, “they’re all out there doing their thing and getting infected and getting sick enough to be in this hospital.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Hospitals are reporting record numbers of COVID-19 patients in their 30s, largely because of the contagious Delta variant, according to The Wall Street Journal.

The rate of new hospitalizations for ages 30-39 reached 2.5 per 100,000 people last week, according to the latest CDC data, which is up from the previous peak of 2 per 100,000 people in January.

What’s more, new hospital admissions for patients in their 30s reached an average of 1,113 a day during the last week, which was up from 908 the week before.

“It means Delta is really bad,” James Lawler, MD, an infectious disease doctor and codirector of the Global Center for Health Security at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, told the newspaper.

People in the age group mostly avoided hospitalization throughout the pandemic because of their relatively good health and young age, the newspaper reported. But in recent weeks, those between ages 30 and 39 are contracting the coronavirus because of their active lifestyle – for many in their 30s, these are prime years for working, parenting, and socializing.

Hospitalizations are mostly among unvaccinated adults, according to the Wall Street Journal. Nationally, less than half of those ages 25-39 are fully vaccinated, compared with 61% of all adults, according to CDC data updated Sunday.

“It loves social mobility,” James Fiorica, MD, chief medical officer of Sarasota Memorial Health Care System in Florida, told the newspaper.

“An unvaccinated 30-year-old can be a perfect carrier,” he said.

On top of that, COVID-19 patients in their 30s are arriving at hospitals with more severe disease than in earlier waves, the Journal reported. At the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences hospital, for instance, doctors are now monitoring younger patients daily with a scoring system for possible organ failure. That wasn’t necessary earlier in the pandemic for people in their 30s.

“This age group pretty much went unscathed,” Nikhil Meena, MD, director of the hospital’s Medical Intensive Care Unit, told the newspaper.

Now, he said, “they’re all out there doing their thing and getting infected and getting sick enough to be in this hospital.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

U.S. pediatric hospitals in peril as Delta hits children

Over the course of the pandemic, COVID-19 has been a less serious illness for children than it has been for adults, and that continues to be true. But with the arrival of Delta, the risk for kids is rising, and that’s creating a perilous situation for hospitals across the United States that treat them.

Roughly 1,800 kids were hospitalized with COVID-19 in the United States last week, a 500% increase in the rate of COVID-19 hospitalizations for children since early July, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Emerging data from a large study in Canada suggest that children who test positive for COVID-19 during the Delta wave may be more than twice as likely to be hospitalized as they were when previous variants were dominating transmission. The new data support what many pediatric infectious disease experts say they’ve been seeing: Younger kids with more serious symptoms.

That may sound concerning, but keep in mind that the overall risk of hospitalization for kids who have COVID-19 is still very low – about one child for every hundred who test positive for the virus will end up needing hospital care for their symptoms, according to current statistics maintained by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

‘This is different’

At Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis, they saw Delta coming.

Since last year, every kid that comes to the emergency department at the hospital gets a screening test for COVID-19.

In past waves, doctors usually found kids who were infected by accident – they tested positive after coming in for some other problem, a broken leg or appendicitis, said Nick Hysmith, MD, medical director of infection prevention at the hospital. But within the last few weeks, kids with fevers, sore throats, coughs, and runny noses started testing positive for COVID-19.

“We have seen our positive numbers go from, you know, close to about 8%-10% jump up to 20%, and then in recent weeks, we can get as high as 26% or 30%,” Dr. Hysmith said. “Then we started seeing kids sick enough to be admitted.”

“Over the last week, we’ve really seen an increase,” he said. As of August 16, the hospital had 24 children with COVID-19 admitted. Seven of the children were in the PICU, and two were on ventilators.

Arkansas Children’s Hospital had 23 young COVID-19 patients, 10 in intensive care, and five on ventilators, as of Friday, according to the Washington Post. At Children’s of Mississippi, the only hospital for kids in that state, 22 youth were hospitalized as of Monday, with three in intensive care as of August 16, according to the hospital. The nonprofit relief organization Samaritan’s Purse is setting up a second field hospital in the basement of Children’s to expand the hospital’s capacity.

“This is different,” Dr. Hysmith said. “What we’re seeing now is previously healthy kids coming in with symptomatic infection.”

This increased virulence is happening at a bad time. Schools around the United States are reopening for in-person classes, some for the first time in more than a year. Eight states have blocked districts from requiring masks, while many more have made them optional.

Children under 12 still have no access to a vaccine, so they are facing increased exposure to a germ that’s become more dangerous with little protection, especially in schools that have eschewed masks.

More than just COVID-19

Then there are the latent effects of the virus to contend with.

“We’re not only seeing more children now with acute SARS-CoV-2 in the hospital, we’re starting also to see an uptick of MISC – or Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children,” said Charlotte Hobbs, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Mississippi Children’s Hospital. “We are just beginning to [see] those cases, and we anticipate that’s going to get worse.”

Adding to COVID-19’s misery, another virus is also capitalizing on this increased mixing of kids back into the community. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) hospitalizes about 58,000 children under age 5 in the United States each year. The typical RSV season starts in the fall and peaks in February, along with influenza. This year, the RSV season is early, and it is ferocious.

The combination of the two infections is hitting children’s hospitals hard, and it’s layered on top of the indirect effects of the pandemic, such as the increased population of kids and teens who need mental health care in the wake of the crisis.

“It’s all these things happening at the same time,” said Mark Wietecha, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. “To have our hospitals this crowded in August is unusual.

And children’s hospitals are grappling with the same workforce shortages as hospitals that treat adults, while their pool of potential staff is much smaller.

“We can’t easily recruit physicians and nurses from adult hospitals in any practical way to staff a kids’ hospital,” Mr. Wietecha said.

Although pediatric doctors and nurses were trained to care for adults before they specialized, clinicians who primarily care for adults typically haven’t been taught how to care for kids.

Clinicians have fewer tools to fight COVID-19 infections in children than are available for adults.

“There have been many studies in terms of therapies and treatments for acute SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults. We have less data and information in children, and on top of that, some of these treatments aren’t even available under an EUA [emergency use authorization] to children: For example, the monoclonal antibodies,” Dr. Hobbs said.

Antibody treatments are being widely deployed to ease the pressure on hospitals that treat adults. But these therapies aren’t available for kids.

That means children’s hospitals could quickly become overwhelmed, especially in areas where community transmission is high, vaccination rates are low, and parents are screaming about masks.

“So we really have this constellation of events that really doesn’t favor children under the age of 12,” Dr. Hobbs said.

“Universal masking shouldn’t be a debate, because it’s the one thing, with adult vaccination, that can be done to protect this vulnerable population,” she said. “This isn’t a political issue. It’s a public health issue. Period.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Over the course of the pandemic, COVID-19 has been a less serious illness for children than it has been for adults, and that continues to be true. But with the arrival of Delta, the risk for kids is rising, and that’s creating a perilous situation for hospitals across the United States that treat them.

Roughly 1,800 kids were hospitalized with COVID-19 in the United States last week, a 500% increase in the rate of COVID-19 hospitalizations for children since early July, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Emerging data from a large study in Canada suggest that children who test positive for COVID-19 during the Delta wave may be more than twice as likely to be hospitalized as they were when previous variants were dominating transmission. The new data support what many pediatric infectious disease experts say they’ve been seeing: Younger kids with more serious symptoms.

That may sound concerning, but keep in mind that the overall risk of hospitalization for kids who have COVID-19 is still very low – about one child for every hundred who test positive for the virus will end up needing hospital care for their symptoms, according to current statistics maintained by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

‘This is different’

At Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis, they saw Delta coming.

Since last year, every kid that comes to the emergency department at the hospital gets a screening test for COVID-19.

In past waves, doctors usually found kids who were infected by accident – they tested positive after coming in for some other problem, a broken leg or appendicitis, said Nick Hysmith, MD, medical director of infection prevention at the hospital. But within the last few weeks, kids with fevers, sore throats, coughs, and runny noses started testing positive for COVID-19.

“We have seen our positive numbers go from, you know, close to about 8%-10% jump up to 20%, and then in recent weeks, we can get as high as 26% or 30%,” Dr. Hysmith said. “Then we started seeing kids sick enough to be admitted.”

“Over the last week, we’ve really seen an increase,” he said. As of August 16, the hospital had 24 children with COVID-19 admitted. Seven of the children were in the PICU, and two were on ventilators.

Arkansas Children’s Hospital had 23 young COVID-19 patients, 10 in intensive care, and five on ventilators, as of Friday, according to the Washington Post. At Children’s of Mississippi, the only hospital for kids in that state, 22 youth were hospitalized as of Monday, with three in intensive care as of August 16, according to the hospital. The nonprofit relief organization Samaritan’s Purse is setting up a second field hospital in the basement of Children’s to expand the hospital’s capacity.

“This is different,” Dr. Hysmith said. “What we’re seeing now is previously healthy kids coming in with symptomatic infection.”

This increased virulence is happening at a bad time. Schools around the United States are reopening for in-person classes, some for the first time in more than a year. Eight states have blocked districts from requiring masks, while many more have made them optional.

Children under 12 still have no access to a vaccine, so they are facing increased exposure to a germ that’s become more dangerous with little protection, especially in schools that have eschewed masks.

More than just COVID-19

Then there are the latent effects of the virus to contend with.

“We’re not only seeing more children now with acute SARS-CoV-2 in the hospital, we’re starting also to see an uptick of MISC – or Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children,” said Charlotte Hobbs, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Mississippi Children’s Hospital. “We are just beginning to [see] those cases, and we anticipate that’s going to get worse.”

Adding to COVID-19’s misery, another virus is also capitalizing on this increased mixing of kids back into the community. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) hospitalizes about 58,000 children under age 5 in the United States each year. The typical RSV season starts in the fall and peaks in February, along with influenza. This year, the RSV season is early, and it is ferocious.

The combination of the two infections is hitting children’s hospitals hard, and it’s layered on top of the indirect effects of the pandemic, such as the increased population of kids and teens who need mental health care in the wake of the crisis.

“It’s all these things happening at the same time,” said Mark Wietecha, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. “To have our hospitals this crowded in August is unusual.

And children’s hospitals are grappling with the same workforce shortages as hospitals that treat adults, while their pool of potential staff is much smaller.

“We can’t easily recruit physicians and nurses from adult hospitals in any practical way to staff a kids’ hospital,” Mr. Wietecha said.

Although pediatric doctors and nurses were trained to care for adults before they specialized, clinicians who primarily care for adults typically haven’t been taught how to care for kids.

Clinicians have fewer tools to fight COVID-19 infections in children than are available for adults.

“There have been many studies in terms of therapies and treatments for acute SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults. We have less data and information in children, and on top of that, some of these treatments aren’t even available under an EUA [emergency use authorization] to children: For example, the monoclonal antibodies,” Dr. Hobbs said.

Antibody treatments are being widely deployed to ease the pressure on hospitals that treat adults. But these therapies aren’t available for kids.

That means children’s hospitals could quickly become overwhelmed, especially in areas where community transmission is high, vaccination rates are low, and parents are screaming about masks.

“So we really have this constellation of events that really doesn’t favor children under the age of 12,” Dr. Hobbs said.

“Universal masking shouldn’t be a debate, because it’s the one thing, with adult vaccination, that can be done to protect this vulnerable population,” she said. “This isn’t a political issue. It’s a public health issue. Period.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Over the course of the pandemic, COVID-19 has been a less serious illness for children than it has been for adults, and that continues to be true. But with the arrival of Delta, the risk for kids is rising, and that’s creating a perilous situation for hospitals across the United States that treat them.

Roughly 1,800 kids were hospitalized with COVID-19 in the United States last week, a 500% increase in the rate of COVID-19 hospitalizations for children since early July, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Emerging data from a large study in Canada suggest that children who test positive for COVID-19 during the Delta wave may be more than twice as likely to be hospitalized as they were when previous variants were dominating transmission. The new data support what many pediatric infectious disease experts say they’ve been seeing: Younger kids with more serious symptoms.

That may sound concerning, but keep in mind that the overall risk of hospitalization for kids who have COVID-19 is still very low – about one child for every hundred who test positive for the virus will end up needing hospital care for their symptoms, according to current statistics maintained by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

‘This is different’

At Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis, they saw Delta coming.

Since last year, every kid that comes to the emergency department at the hospital gets a screening test for COVID-19.

In past waves, doctors usually found kids who were infected by accident – they tested positive after coming in for some other problem, a broken leg or appendicitis, said Nick Hysmith, MD, medical director of infection prevention at the hospital. But within the last few weeks, kids with fevers, sore throats, coughs, and runny noses started testing positive for COVID-19.

“We have seen our positive numbers go from, you know, close to about 8%-10% jump up to 20%, and then in recent weeks, we can get as high as 26% or 30%,” Dr. Hysmith said. “Then we started seeing kids sick enough to be admitted.”

“Over the last week, we’ve really seen an increase,” he said. As of August 16, the hospital had 24 children with COVID-19 admitted. Seven of the children were in the PICU, and two were on ventilators.

Arkansas Children’s Hospital had 23 young COVID-19 patients, 10 in intensive care, and five on ventilators, as of Friday, according to the Washington Post. At Children’s of Mississippi, the only hospital for kids in that state, 22 youth were hospitalized as of Monday, with three in intensive care as of August 16, according to the hospital. The nonprofit relief organization Samaritan’s Purse is setting up a second field hospital in the basement of Children’s to expand the hospital’s capacity.

“This is different,” Dr. Hysmith said. “What we’re seeing now is previously healthy kids coming in with symptomatic infection.”

This increased virulence is happening at a bad time. Schools around the United States are reopening for in-person classes, some for the first time in more than a year. Eight states have blocked districts from requiring masks, while many more have made them optional.

Children under 12 still have no access to a vaccine, so they are facing increased exposure to a germ that’s become more dangerous with little protection, especially in schools that have eschewed masks.

More than just COVID-19

Then there are the latent effects of the virus to contend with.

“We’re not only seeing more children now with acute SARS-CoV-2 in the hospital, we’re starting also to see an uptick of MISC – or Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children,” said Charlotte Hobbs, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Mississippi Children’s Hospital. “We are just beginning to [see] those cases, and we anticipate that’s going to get worse.”

Adding to COVID-19’s misery, another virus is also capitalizing on this increased mixing of kids back into the community. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) hospitalizes about 58,000 children under age 5 in the United States each year. The typical RSV season starts in the fall and peaks in February, along with influenza. This year, the RSV season is early, and it is ferocious.

The combination of the two infections is hitting children’s hospitals hard, and it’s layered on top of the indirect effects of the pandemic, such as the increased population of kids and teens who need mental health care in the wake of the crisis.

“It’s all these things happening at the same time,” said Mark Wietecha, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. “To have our hospitals this crowded in August is unusual.

And children’s hospitals are grappling with the same workforce shortages as hospitals that treat adults, while their pool of potential staff is much smaller.

“We can’t easily recruit physicians and nurses from adult hospitals in any practical way to staff a kids’ hospital,” Mr. Wietecha said.

Although pediatric doctors and nurses were trained to care for adults before they specialized, clinicians who primarily care for adults typically haven’t been taught how to care for kids.

Clinicians have fewer tools to fight COVID-19 infections in children than are available for adults.

“There have been many studies in terms of therapies and treatments for acute SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults. We have less data and information in children, and on top of that, some of these treatments aren’t even available under an EUA [emergency use authorization] to children: For example, the monoclonal antibodies,” Dr. Hobbs said.

Antibody treatments are being widely deployed to ease the pressure on hospitals that treat adults. But these therapies aren’t available for kids.

That means children’s hospitals could quickly become overwhelmed, especially in areas where community transmission is high, vaccination rates are low, and parents are screaming about masks.

“So we really have this constellation of events that really doesn’t favor children under the age of 12,” Dr. Hobbs said.

“Universal masking shouldn’t be a debate, because it’s the one thing, with adult vaccination, that can be done to protect this vulnerable population,” she said. “This isn’t a political issue. It’s a public health issue. Period.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Youngest children more likely to spread SARS-CoV-2 to family: Study

Young children are more likely than are their older siblings to transmit SARS-CoV-2 in their households, according to an analysis of public health records in Ontario, Canada – a finding that upends the common belief that children play a minimal role in COVID-19 spread.

The study by researchers from Public Health Ontario, published online in JAMA Pediatrics, found that teenagers (14- to 17-year-olds) were more likely than were their younger siblings to bring the virus into the household, while infants and toddlers (up to age 3) were about 43% more likely than were the older teens to spread it to others in the home.

Children or teens were the source of SARS-CoV-2 in about 1 in 13 Ontario households between June and December 2020, the study shows. The researchers analyzed health records from 6,280 households with a pediatric COVID-19 case and a subset of 1,717 households in which a child up to age 17 was the source of transmission in a household.

When analyzing the data, the researchers controlled for gender differences, month of disease onset, testing delay, and mean family size.

The role of young children in transmission seemed logical to some experts who have been tracking the evolution of the pandemic. “I think what was more surprising was how long the narrative persisted that children weren’t transmitting SARS-CoV-2,” said Samuel Scarpino, PhD, managing director of pathogen surveillance at the Rockefeller Foundation.

Meanwhile, less mask-wearing, the return to school and activities, and the onslaught of the Delta variant have changed the dynamics of spread, said Andrew Pavia, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Utah.

“Adolescents and high-school-aged kids have had much, much higher rates of infection in the past,” he said. “Now when we look at the rates of school-aged kids, they are the same as high-school-aged kids, and we’re seeing more and more in the preschool age groups.”

Cases may be underestimated

If anything, the study may underestimate the role young children play in spreading COVID-19 in families, since it included only symptomatic cases as the initial source and young children are more likely to be asymptomatic, Dr. Pavia said.

The Delta variant heightens the concern; it is more than twice as infectious as previous strains and has spurred a rise in pediatric cases, including some coinfection with other circulating respiratory diseases, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The Ontario study covers a period before vaccination and the spread of the Delta variant. “As the number of pediatric cases increases worldwide, the role of children in household transmission will continue to grow,” the authors concluded.

Following recommended respiratory hygiene is clearly more difficult with very young children. For example, parents, caregivers, and older siblings aren’t going to stay 6 feet away from a sick baby or toddler, Susan Coffin, MD, MPH, a pediatric infectious disease physician, and David Rubin, MD, a pediatrician and director of PolicyLab at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, noted in an accompanying commentary.

“Cuddling and touching are part and parcel of taking care of a sick young child, and that will obviously come with an increased risk of transmission to parents as well as to older siblings who may be helping to care for their sick brother or sister,” they wrote.

While parents may wash their hands more frequently when caring for a sick child, they aren’t likely to wear a mask, said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

“I imagine some moms even take a sick child into bed with them,” he said. “It’s probably just the extensive contact one has with a sick, very small child that augments their capacity to transmit this infection.”

What can be done

What can be done, then, to reduce the household spread of COVID-19? “The obvious solution to protect a household with a sick young infant or toddler is to make sure that all eligible members of the household are vaccinated,” Dr. Coffin and Dr. Rubin stated in their commentary.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recently wrote to Janet Woodcock, MD, acting commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, asking for the agency to authorize use of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for children under age 12 “as soon as possible,” noting that “the Delta variant has created a new and pressing risk to children and adolescents across this country, as it has also done for unvaccinated adults.”

The FDA reportedly asked vaccine makers Pfizer and Moderna to expand the clinical trials of children, which may delay authorization for younger age groups. Pfizer has said it plans to submit a request for emergency use authorization of its vaccine for 5- to 11-year-olds in September or October.

As with adult vaccination, hesitancy is likely to be a barrier. Less than half of parents said they are very or somewhat likely to have their children get a COVID-19 vaccine, according to a national survey conducted by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The Ontario study provides valuable evidence to support taking steps to protect children from transmission in schools, including mask requirements, frequent testing, and improved ventilation, said Dr. Scarpino.

“We’re not going to be able to control COVID without vaccinating younger individuals,” he said.

Dr. Pavia has consulted for GlaxoSmithKline on non–COVID-19–related issues. Sarah Buchan, PhD, study author and scientist at Public Health Ontario, reported grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for research on influenza, RSV, and COVID-19, and grants from the Canadian Immunity Task Force for COVID-19 outside the submitted work. Dr. Coffin reported grants as a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention coinvestigator at a Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Unit site conducting COVID-19 vaccine trials in children. Dr. Scarpino holds unexercised options in ILiAD Biotechnologies, which is focused on the prevention and treatment of pertussis. Dr. Schaffner is a consultant for VBI Vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Young children are more likely than are their older siblings to transmit SARS-CoV-2 in their households, according to an analysis of public health records in Ontario, Canada – a finding that upends the common belief that children play a minimal role in COVID-19 spread.

The study by researchers from Public Health Ontario, published online in JAMA Pediatrics, found that teenagers (14- to 17-year-olds) were more likely than were their younger siblings to bring the virus into the household, while infants and toddlers (up to age 3) were about 43% more likely than were the older teens to spread it to others in the home.

Children or teens were the source of SARS-CoV-2 in about 1 in 13 Ontario households between June and December 2020, the study shows. The researchers analyzed health records from 6,280 households with a pediatric COVID-19 case and a subset of 1,717 households in which a child up to age 17 was the source of transmission in a household.

When analyzing the data, the researchers controlled for gender differences, month of disease onset, testing delay, and mean family size.

The role of young children in transmission seemed logical to some experts who have been tracking the evolution of the pandemic. “I think what was more surprising was how long the narrative persisted that children weren’t transmitting SARS-CoV-2,” said Samuel Scarpino, PhD, managing director of pathogen surveillance at the Rockefeller Foundation.

Meanwhile, less mask-wearing, the return to school and activities, and the onslaught of the Delta variant have changed the dynamics of spread, said Andrew Pavia, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Utah.

“Adolescents and high-school-aged kids have had much, much higher rates of infection in the past,” he said. “Now when we look at the rates of school-aged kids, they are the same as high-school-aged kids, and we’re seeing more and more in the preschool age groups.”

Cases may be underestimated

If anything, the study may underestimate the role young children play in spreading COVID-19 in families, since it included only symptomatic cases as the initial source and young children are more likely to be asymptomatic, Dr. Pavia said.

The Delta variant heightens the concern; it is more than twice as infectious as previous strains and has spurred a rise in pediatric cases, including some coinfection with other circulating respiratory diseases, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The Ontario study covers a period before vaccination and the spread of the Delta variant. “As the number of pediatric cases increases worldwide, the role of children in household transmission will continue to grow,” the authors concluded.

Following recommended respiratory hygiene is clearly more difficult with very young children. For example, parents, caregivers, and older siblings aren’t going to stay 6 feet away from a sick baby or toddler, Susan Coffin, MD, MPH, a pediatric infectious disease physician, and David Rubin, MD, a pediatrician and director of PolicyLab at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, noted in an accompanying commentary.

“Cuddling and touching are part and parcel of taking care of a sick young child, and that will obviously come with an increased risk of transmission to parents as well as to older siblings who may be helping to care for their sick brother or sister,” they wrote.

While parents may wash their hands more frequently when caring for a sick child, they aren’t likely to wear a mask, said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

“I imagine some moms even take a sick child into bed with them,” he said. “It’s probably just the extensive contact one has with a sick, very small child that augments their capacity to transmit this infection.”

What can be done

What can be done, then, to reduce the household spread of COVID-19? “The obvious solution to protect a household with a sick young infant or toddler is to make sure that all eligible members of the household are vaccinated,” Dr. Coffin and Dr. Rubin stated in their commentary.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recently wrote to Janet Woodcock, MD, acting commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, asking for the agency to authorize use of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for children under age 12 “as soon as possible,” noting that “the Delta variant has created a new and pressing risk to children and adolescents across this country, as it has also done for unvaccinated adults.”

The FDA reportedly asked vaccine makers Pfizer and Moderna to expand the clinical trials of children, which may delay authorization for younger age groups. Pfizer has said it plans to submit a request for emergency use authorization of its vaccine for 5- to 11-year-olds in September or October.

As with adult vaccination, hesitancy is likely to be a barrier. Less than half of parents said they are very or somewhat likely to have their children get a COVID-19 vaccine, according to a national survey conducted by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The Ontario study provides valuable evidence to support taking steps to protect children from transmission in schools, including mask requirements, frequent testing, and improved ventilation, said Dr. Scarpino.

“We’re not going to be able to control COVID without vaccinating younger individuals,” he said.

Dr. Pavia has consulted for GlaxoSmithKline on non–COVID-19–related issues. Sarah Buchan, PhD, study author and scientist at Public Health Ontario, reported grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for research on influenza, RSV, and COVID-19, and grants from the Canadian Immunity Task Force for COVID-19 outside the submitted work. Dr. Coffin reported grants as a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention coinvestigator at a Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Unit site conducting COVID-19 vaccine trials in children. Dr. Scarpino holds unexercised options in ILiAD Biotechnologies, which is focused on the prevention and treatment of pertussis. Dr. Schaffner is a consultant for VBI Vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Young children are more likely than are their older siblings to transmit SARS-CoV-2 in their households, according to an analysis of public health records in Ontario, Canada – a finding that upends the common belief that children play a minimal role in COVID-19 spread.

The study by researchers from Public Health Ontario, published online in JAMA Pediatrics, found that teenagers (14- to 17-year-olds) were more likely than were their younger siblings to bring the virus into the household, while infants and toddlers (up to age 3) were about 43% more likely than were the older teens to spread it to others in the home.

Children or teens were the source of SARS-CoV-2 in about 1 in 13 Ontario households between June and December 2020, the study shows. The researchers analyzed health records from 6,280 households with a pediatric COVID-19 case and a subset of 1,717 households in which a child up to age 17 was the source of transmission in a household.

When analyzing the data, the researchers controlled for gender differences, month of disease onset, testing delay, and mean family size.

The role of young children in transmission seemed logical to some experts who have been tracking the evolution of the pandemic. “I think what was more surprising was how long the narrative persisted that children weren’t transmitting SARS-CoV-2,” said Samuel Scarpino, PhD, managing director of pathogen surveillance at the Rockefeller Foundation.

Meanwhile, less mask-wearing, the return to school and activities, and the onslaught of the Delta variant have changed the dynamics of spread, said Andrew Pavia, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Utah.

“Adolescents and high-school-aged kids have had much, much higher rates of infection in the past,” he said. “Now when we look at the rates of school-aged kids, they are the same as high-school-aged kids, and we’re seeing more and more in the preschool age groups.”

Cases may be underestimated

If anything, the study may underestimate the role young children play in spreading COVID-19 in families, since it included only symptomatic cases as the initial source and young children are more likely to be asymptomatic, Dr. Pavia said.

The Delta variant heightens the concern; it is more than twice as infectious as previous strains and has spurred a rise in pediatric cases, including some coinfection with other circulating respiratory diseases, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The Ontario study covers a period before vaccination and the spread of the Delta variant. “As the number of pediatric cases increases worldwide, the role of children in household transmission will continue to grow,” the authors concluded.

Following recommended respiratory hygiene is clearly more difficult with very young children. For example, parents, caregivers, and older siblings aren’t going to stay 6 feet away from a sick baby or toddler, Susan Coffin, MD, MPH, a pediatric infectious disease physician, and David Rubin, MD, a pediatrician and director of PolicyLab at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, noted in an accompanying commentary.

“Cuddling and touching are part and parcel of taking care of a sick young child, and that will obviously come with an increased risk of transmission to parents as well as to older siblings who may be helping to care for their sick brother or sister,” they wrote.

While parents may wash their hands more frequently when caring for a sick child, they aren’t likely to wear a mask, said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

“I imagine some moms even take a sick child into bed with them,” he said. “It’s probably just the extensive contact one has with a sick, very small child that augments their capacity to transmit this infection.”

What can be done

What can be done, then, to reduce the household spread of COVID-19? “The obvious solution to protect a household with a sick young infant or toddler is to make sure that all eligible members of the household are vaccinated,” Dr. Coffin and Dr. Rubin stated in their commentary.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recently wrote to Janet Woodcock, MD, acting commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, asking for the agency to authorize use of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for children under age 12 “as soon as possible,” noting that “the Delta variant has created a new and pressing risk to children and adolescents across this country, as it has also done for unvaccinated adults.”

The FDA reportedly asked vaccine makers Pfizer and Moderna to expand the clinical trials of children, which may delay authorization for younger age groups. Pfizer has said it plans to submit a request for emergency use authorization of its vaccine for 5- to 11-year-olds in September or October.

As with adult vaccination, hesitancy is likely to be a barrier. Less than half of parents said they are very or somewhat likely to have their children get a COVID-19 vaccine, according to a national survey conducted by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The Ontario study provides valuable evidence to support taking steps to protect children from transmission in schools, including mask requirements, frequent testing, and improved ventilation, said Dr. Scarpino.

“We’re not going to be able to control COVID without vaccinating younger individuals,” he said.

Dr. Pavia has consulted for GlaxoSmithKline on non–COVID-19–related issues. Sarah Buchan, PhD, study author and scientist at Public Health Ontario, reported grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for research on influenza, RSV, and COVID-19, and grants from the Canadian Immunity Task Force for COVID-19 outside the submitted work. Dr. Coffin reported grants as a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention coinvestigator at a Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Unit site conducting COVID-19 vaccine trials in children. Dr. Scarpino holds unexercised options in ILiAD Biotechnologies, which is focused on the prevention and treatment of pertussis. Dr. Schaffner is a consultant for VBI Vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. reports record COVID-19 hospitalizations of children

The number of children hospitalized with COVID-19 in the U.S. hit a record high on Aug. 14, with more than 1,900 in hospitals.

Hospitals across the South are running out of beds as the contagious Delta variant spreads, mostly among unvaccinated people. Children make up about 2.4% of the country’s COVID-19 hospitalizations, and those under 12 are particularly vulnerable since they’re not eligible to receive a vaccine.

“This is not last year’s COVID,” Sally Goza, MD, former president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, told CNN on Aug. 14.

“This one is worse, and our children are the ones that are going to be affected by it the most,” she said.

The number of newly hospitalized COVID-19 patients for ages 18-49 also hit record highs during the week of Aug. 9. A fifth of the nation’s hospitalizations are in Florida, where the number of COVID-19 patients hit a record high of 16,100 on Aug. 14. More than 90% of the state’s intensive care unit beds are filled.

More than 90% of the ICU beds in Texas are full as well. On Aug. 13, there were no pediatric ICU beds available in Dallas or the 19 surrounding counties, which means that young patients would be transported father away for care – even Oklahoma City.

“That means if your child’s in a car wreck, if your child has a congenital heart defect or something and needs an ICU bed, or more likely, if they have COVID and need an ICU bed, we don’t have one,” Clay Jenkins, a Dallas County judge, said on Aug. 13.

“Your child will wait for another child to die,” he said.

As children return to classes, educators are talking about the possibility of vaccine mandates. The National Education Association announced its support of mandatory vaccination for its members.

“Our students under 12 can’t get vaccinated,” Becky Pringle, president of the association, told CNN.

“It’s our responsibility to keep them safe,” she said. “Keeping them safe means that everyone who can be vaccinated should be vaccinated.”

The U.S. now has an average of about 129,000 new COVID-19 cases per day, Reuters reported, which has doubled in about 2 weeks. The number of hospitalized patients is at a 6-month high, and about 600 people are dying each day.

Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Oregon have reported record numbers of COVID-19 hospitalizations.

In addition, eight states make up half of all the COVID-19 hospitalizations in the U.S. but only 24% of the nation’s population – Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada, and Texas. These states have vaccination rates lower than the national average, and their COVID-19 patients account for at least 15% of their overall hospitalizations.

To address the surge in hospitalizations, Oregon Gov. Kate Brown has ordered the deployment of up to 1,500 Oregon National Guard members to help health care workers.

“I know this is not the summer many of us envisioned,” Gov. Brown said Aug. 13. “The harsh and frustrating reality is that the Delta variant has changed everything. Delta is highly contagious, and we must take action now.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The number of children hospitalized with COVID-19 in the U.S. hit a record high on Aug. 14, with more than 1,900 in hospitals.

Hospitals across the South are running out of beds as the contagious Delta variant spreads, mostly among unvaccinated people. Children make up about 2.4% of the country’s COVID-19 hospitalizations, and those under 12 are particularly vulnerable since they’re not eligible to receive a vaccine.

“This is not last year’s COVID,” Sally Goza, MD, former president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, told CNN on Aug. 14.

“This one is worse, and our children are the ones that are going to be affected by it the most,” she said.

The number of newly hospitalized COVID-19 patients for ages 18-49 also hit record highs during the week of Aug. 9. A fifth of the nation’s hospitalizations are in Florida, where the number of COVID-19 patients hit a record high of 16,100 on Aug. 14. More than 90% of the state’s intensive care unit beds are filled.

More than 90% of the ICU beds in Texas are full as well. On Aug. 13, there were no pediatric ICU beds available in Dallas or the 19 surrounding counties, which means that young patients would be transported father away for care – even Oklahoma City.

“That means if your child’s in a car wreck, if your child has a congenital heart defect or something and needs an ICU bed, or more likely, if they have COVID and need an ICU bed, we don’t have one,” Clay Jenkins, a Dallas County judge, said on Aug. 13.

“Your child will wait for another child to die,” he said.

As children return to classes, educators are talking about the possibility of vaccine mandates. The National Education Association announced its support of mandatory vaccination for its members.

“Our students under 12 can’t get vaccinated,” Becky Pringle, president of the association, told CNN.

“It’s our responsibility to keep them safe,” she said. “Keeping them safe means that everyone who can be vaccinated should be vaccinated.”

The U.S. now has an average of about 129,000 new COVID-19 cases per day, Reuters reported, which has doubled in about 2 weeks. The number of hospitalized patients is at a 6-month high, and about 600 people are dying each day.

Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Oregon have reported record numbers of COVID-19 hospitalizations.

In addition, eight states make up half of all the COVID-19 hospitalizations in the U.S. but only 24% of the nation’s population – Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada, and Texas. These states have vaccination rates lower than the national average, and their COVID-19 patients account for at least 15% of their overall hospitalizations.

To address the surge in hospitalizations, Oregon Gov. Kate Brown has ordered the deployment of up to 1,500 Oregon National Guard members to help health care workers.

“I know this is not the summer many of us envisioned,” Gov. Brown said Aug. 13. “The harsh and frustrating reality is that the Delta variant has changed everything. Delta is highly contagious, and we must take action now.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The number of children hospitalized with COVID-19 in the U.S. hit a record high on Aug. 14, with more than 1,900 in hospitals.

Hospitals across the South are running out of beds as the contagious Delta variant spreads, mostly among unvaccinated people. Children make up about 2.4% of the country’s COVID-19 hospitalizations, and those under 12 are particularly vulnerable since they’re not eligible to receive a vaccine.

“This is not last year’s COVID,” Sally Goza, MD, former president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, told CNN on Aug. 14.

“This one is worse, and our children are the ones that are going to be affected by it the most,” she said.

The number of newly hospitalized COVID-19 patients for ages 18-49 also hit record highs during the week of Aug. 9. A fifth of the nation’s hospitalizations are in Florida, where the number of COVID-19 patients hit a record high of 16,100 on Aug. 14. More than 90% of the state’s intensive care unit beds are filled.

More than 90% of the ICU beds in Texas are full as well. On Aug. 13, there were no pediatric ICU beds available in Dallas or the 19 surrounding counties, which means that young patients would be transported father away for care – even Oklahoma City.

“That means if your child’s in a car wreck, if your child has a congenital heart defect or something and needs an ICU bed, or more likely, if they have COVID and need an ICU bed, we don’t have one,” Clay Jenkins, a Dallas County judge, said on Aug. 13.

“Your child will wait for another child to die,” he said.

As children return to classes, educators are talking about the possibility of vaccine mandates. The National Education Association announced its support of mandatory vaccination for its members.

“Our students under 12 can’t get vaccinated,” Becky Pringle, president of the association, told CNN.

“It’s our responsibility to keep them safe,” she said. “Keeping them safe means that everyone who can be vaccinated should be vaccinated.”

The U.S. now has an average of about 129,000 new COVID-19 cases per day, Reuters reported, which has doubled in about 2 weeks. The number of hospitalized patients is at a 6-month high, and about 600 people are dying each day.

Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Oregon have reported record numbers of COVID-19 hospitalizations.

In addition, eight states make up half of all the COVID-19 hospitalizations in the U.S. but only 24% of the nation’s population – Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada, and Texas. These states have vaccination rates lower than the national average, and their COVID-19 patients account for at least 15% of their overall hospitalizations.

To address the surge in hospitalizations, Oregon Gov. Kate Brown has ordered the deployment of up to 1,500 Oregon National Guard members to help health care workers.

“I know this is not the summer many of us envisioned,” Gov. Brown said Aug. 13. “The harsh and frustrating reality is that the Delta variant has changed everything. Delta is highly contagious, and we must take action now.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Universal masking is the key to safe school attendance

“I want my child to go back to school,” the mother said to me. “I just want you to tell me it will be safe.”

As the summer break winds down for children across the United States, pediatric COVID-19 cases are rising. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, nearly 94,000 cases were reported for the week ending Aug. 5, more than double the case count from 2 weeks earlier.1

Anecdotally, some children’s hospitals are reporting an increase in pediatric COVID-19 admissions. In the hospital in which I practice, we are seeing numbers similar to those we saw in December and January: a typical daily census of 10 kids admitted with COVID-19, with 4 of them in the intensive care unit. It is a stark contrast to June when, most days, we had no patients with COVID-19 in the hospital. About half of our hospitalized patients are too young to be vaccinated against COVID-19, while the rest are unvaccinated children 12 years and older.

Vaccination of eligible children and teachers is an essential strategy for preventing the spread of COVID-19 in schools, but as children head back to school, immunization rates of educators are largely unknown and are suboptimal among students in most states. As of Aug. 11, 10.7 million U.S. children had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, representing 43% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 53% of 16- to 17-year-olds.2 Rates vary substantially by state, with more than 70% of kids in Vermont receiving at least one dose of vaccine, compared with less than 25% in Wyoming and Alabama.

Still, in the absence of robust immunization rates, we have data that schools can still reopen successfully. We need to follow the science and implement universal masking, a safe, effective, and practical mitigation strategy.

It worked in Wisconsin. Seventeen K-12 schools in rural Wisconsin opened last fall for in-person instruction.3 Reported compliance with masking was high, ranging from 92.1% to 97.4%, and in-school transmission of COVID-19 was low, with seven cases among 4,876 students.