User login

Plastic IUD placement instruments prevent uterine perforations

Key clinical point: In a biomechanical ex vivo analysis, metal uterine sounds caused uterine perforation, but the manufacturer’s plastic intrauterine device placement rod did not.

Major finding: The lowest mean maximum force generated for IUD placement was 12.3 Newtons with the levonorgestrel intrauterine system placement instrument, followed by 14.1 Newtons with the copper T380A intrauterine device placement instrument 14.1 Newtons; the highest mean maximum force of 17.9 N occurred with the metal sound (P < 0.01).

Study details: The data come from 16 premenopausal women with benign conditions who provided hysterectomy sections at a single center.

Disclosures: The study was funded indirectly through grants to the University of Utah from Bayer, Bioceptive, Sebela, Medicines 360, Merck, and Cooper Surgical. Lead author Dr. Duncan had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Duncan J et al. BMC Womens Health. 2021 Apr 7. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01285-6.

Key clinical point: In a biomechanical ex vivo analysis, metal uterine sounds caused uterine perforation, but the manufacturer’s plastic intrauterine device placement rod did not.

Major finding: The lowest mean maximum force generated for IUD placement was 12.3 Newtons with the levonorgestrel intrauterine system placement instrument, followed by 14.1 Newtons with the copper T380A intrauterine device placement instrument 14.1 Newtons; the highest mean maximum force of 17.9 N occurred with the metal sound (P < 0.01).

Study details: The data come from 16 premenopausal women with benign conditions who provided hysterectomy sections at a single center.

Disclosures: The study was funded indirectly through grants to the University of Utah from Bayer, Bioceptive, Sebela, Medicines 360, Merck, and Cooper Surgical. Lead author Dr. Duncan had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Duncan J et al. BMC Womens Health. 2021 Apr 7. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01285-6.

Key clinical point: In a biomechanical ex vivo analysis, metal uterine sounds caused uterine perforation, but the manufacturer’s plastic intrauterine device placement rod did not.

Major finding: The lowest mean maximum force generated for IUD placement was 12.3 Newtons with the levonorgestrel intrauterine system placement instrument, followed by 14.1 Newtons with the copper T380A intrauterine device placement instrument 14.1 Newtons; the highest mean maximum force of 17.9 N occurred with the metal sound (P < 0.01).

Study details: The data come from 16 premenopausal women with benign conditions who provided hysterectomy sections at a single center.

Disclosures: The study was funded indirectly through grants to the University of Utah from Bayer, Bioceptive, Sebela, Medicines 360, Merck, and Cooper Surgical. Lead author Dr. Duncan had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Duncan J et al. BMC Womens Health. 2021 Apr 7. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01285-6.

Oral contraceptive use shows no impact on later heart failure risk

Key clinical point: Use of oral contraceptives by women of reproductive age was not associated with increased risk of heart failure later in life, but the potential impact of different formulations and dosages deserves further research.

Major finding: Over an average of 12 years’ follow-up, the researchers identified 138 incident cases of heart failure. The incidence of heart failure was not significantly associated with heart failure in multivariate analysis (hazard ratio 0.96); however, any OC use was positively associated with left ventricular end-diastolic mass (P = 0.006) and stroke volume (P = 0.01 and P = 0.005 for left and right ventricles, respectively).

Study details: The data come from a retrospective study of 3,594 women with an average age of 62 years who were enrolled in the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and could provide data on oral contraceptive use.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Guangdong Peak Project, the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, and the National Key Research and Development Program of China. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Luo D et al. ESC Heart Fail. 2021 Apr 9. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13328.

Key clinical point: Use of oral contraceptives by women of reproductive age was not associated with increased risk of heart failure later in life, but the potential impact of different formulations and dosages deserves further research.

Major finding: Over an average of 12 years’ follow-up, the researchers identified 138 incident cases of heart failure. The incidence of heart failure was not significantly associated with heart failure in multivariate analysis (hazard ratio 0.96); however, any OC use was positively associated with left ventricular end-diastolic mass (P = 0.006) and stroke volume (P = 0.01 and P = 0.005 for left and right ventricles, respectively).

Study details: The data come from a retrospective study of 3,594 women with an average age of 62 years who were enrolled in the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and could provide data on oral contraceptive use.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Guangdong Peak Project, the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, and the National Key Research and Development Program of China. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Luo D et al. ESC Heart Fail. 2021 Apr 9. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13328.

Key clinical point: Use of oral contraceptives by women of reproductive age was not associated with increased risk of heart failure later in life, but the potential impact of different formulations and dosages deserves further research.

Major finding: Over an average of 12 years’ follow-up, the researchers identified 138 incident cases of heart failure. The incidence of heart failure was not significantly associated with heart failure in multivariate analysis (hazard ratio 0.96); however, any OC use was positively associated with left ventricular end-diastolic mass (P = 0.006) and stroke volume (P = 0.01 and P = 0.005 for left and right ventricles, respectively).

Study details: The data come from a retrospective study of 3,594 women with an average age of 62 years who were enrolled in the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and could provide data on oral contraceptive use.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Guangdong Peak Project, the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, and the National Key Research and Development Program of China. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Luo D et al. ESC Heart Fail. 2021 Apr 9. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13328.

Oral contraceptive with new estrogen earns approval

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a new estrogen for the first time in more than 50 years.

The novel combined oral contraceptive, marketed as Nextstellis, contains 3 mg drospirenone (DRSP) and 14.2 mg of estetrol (E4) in tablet form. Estetrol is an estrogen that is naturally produced during pregnancy, but will now be produced from a plant source; it has not previously been used in oral contraceptives.

Approval of the unique estetrol/drospirenone combination was based on data from a pair of phase 3 clinical trials including 3,725 women. Overall, Nextstellis was safe and effective while meeting its primary endpoint of pregnancy prevention, according to a company press release. Participants also reported favorable results on secondary endpoints including cycle control, bleeding profile, safety, and tolerability.

Although many women take short-acting contraceptives containing estrogen and progestin, concerns persist about side effects, said Mitchell Creinin, MD, of the University of California, in the press release. In addition to providing effective contraception, the drug showed minimal impact on specific markers of concern, including triglycerides, cholesterol, and glucose, as well as weight and endocrine markers, Dr. Creinin said.

Nextstellis was developed by the Belgian biotech company Mithra Pharmaceuticals, and the drug is licensed for distribution in Australia and the United States by Mayne Pharma, with an expected launch at the end of June 2021.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a new estrogen for the first time in more than 50 years.

The novel combined oral contraceptive, marketed as Nextstellis, contains 3 mg drospirenone (DRSP) and 14.2 mg of estetrol (E4) in tablet form. Estetrol is an estrogen that is naturally produced during pregnancy, but will now be produced from a plant source; it has not previously been used in oral contraceptives.

Approval of the unique estetrol/drospirenone combination was based on data from a pair of phase 3 clinical trials including 3,725 women. Overall, Nextstellis was safe and effective while meeting its primary endpoint of pregnancy prevention, according to a company press release. Participants also reported favorable results on secondary endpoints including cycle control, bleeding profile, safety, and tolerability.

Although many women take short-acting contraceptives containing estrogen and progestin, concerns persist about side effects, said Mitchell Creinin, MD, of the University of California, in the press release. In addition to providing effective contraception, the drug showed minimal impact on specific markers of concern, including triglycerides, cholesterol, and glucose, as well as weight and endocrine markers, Dr. Creinin said.

Nextstellis was developed by the Belgian biotech company Mithra Pharmaceuticals, and the drug is licensed for distribution in Australia and the United States by Mayne Pharma, with an expected launch at the end of June 2021.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a new estrogen for the first time in more than 50 years.

The novel combined oral contraceptive, marketed as Nextstellis, contains 3 mg drospirenone (DRSP) and 14.2 mg of estetrol (E4) in tablet form. Estetrol is an estrogen that is naturally produced during pregnancy, but will now be produced from a plant source; it has not previously been used in oral contraceptives.

Approval of the unique estetrol/drospirenone combination was based on data from a pair of phase 3 clinical trials including 3,725 women. Overall, Nextstellis was safe and effective while meeting its primary endpoint of pregnancy prevention, according to a company press release. Participants also reported favorable results on secondary endpoints including cycle control, bleeding profile, safety, and tolerability.

Although many women take short-acting contraceptives containing estrogen and progestin, concerns persist about side effects, said Mitchell Creinin, MD, of the University of California, in the press release. In addition to providing effective contraception, the drug showed minimal impact on specific markers of concern, including triglycerides, cholesterol, and glucose, as well as weight and endocrine markers, Dr. Creinin said.

Nextstellis was developed by the Belgian biotech company Mithra Pharmaceuticals, and the drug is licensed for distribution in Australia and the United States by Mayne Pharma, with an expected launch at the end of June 2021.

Patient-centered contraceptive care for medically complex patients

CASE Patient-centered counseling for contraception

A 19-year-old woman (G0) with moderately well-controlled seizure disorder while taking levetiracetam, who reports migraines, and has a BMI of 32 kg/m2 presents to your office seeking contraception. She is currently sexually active with her second lifetime partner and uses condoms inconsistently. She is otherwise healthy and has no problems to report. Her last menstrual period (LMP) was 1 week ago, and a pregnancy test today is negative. How do you approach counseling for this patient?

The modern contraceptive patient

Our patients are becoming increasingly medically and socially complicated. Meeting the contraceptive needs of patients with multiple comorbidities can be a daunting task. Doing so in a patient-centered way that also recognizes the social contexts and intimacy inherent to contraceptive care can feel overwhelming. However, by employing a systematic approach to each patient, we can provide safe, effective, individualized care to our medically complex patients. Having a few “go-to tools” can streamline the process.

Medically complex patients are often told that they need to avoid pregnancy or optimize their health conditions prior to becoming pregnant, but they may not receive medically-appropriate contraception.1-3 Additionally, obesity rates in women of reproductive age in the United States are increasing, along with related medical complexities.4 Disparities in contraceptive access and use of particular methods exist by socioeconomic status, body mass index (BMI), age, and geography. 5,6 Evidence-based, shared decision making can improve contraceptive satisfaction.7

Clinicians need to stay attuned to all options. Staying current on available contraceptive methods can broaden clinicians’ thinking and allow patients more choices that are compatible with their medical needs. In the last 2 years alone, a 1-year combined estrogen-progestin vaginal ring, a drospirinone-only pill, and a nonhormonal spermicide have become available for prescription.8-10 Both 52 mg levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine devices (IUDs) are now US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for 6 years, and there is excellent data for off-label use to 7 years.11

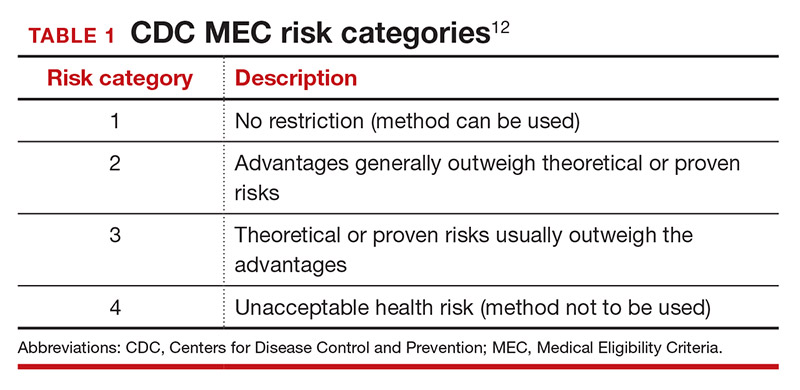

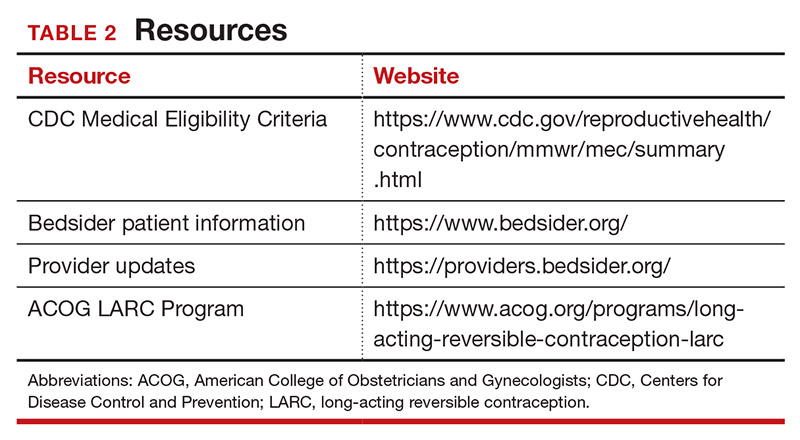

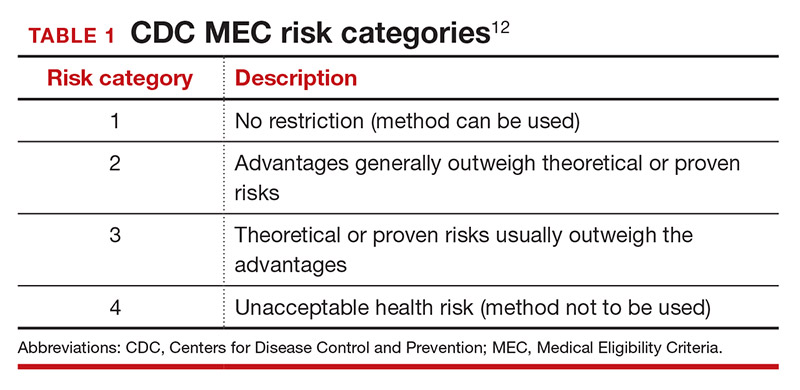

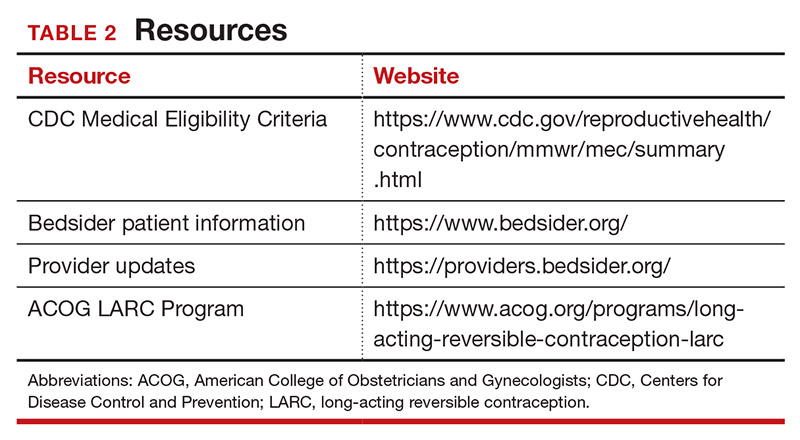

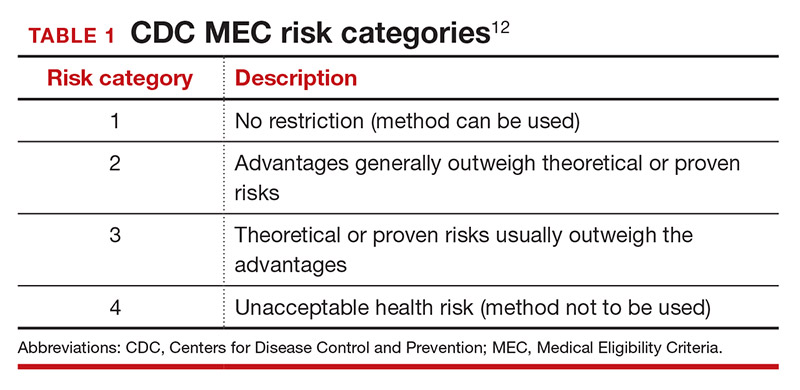

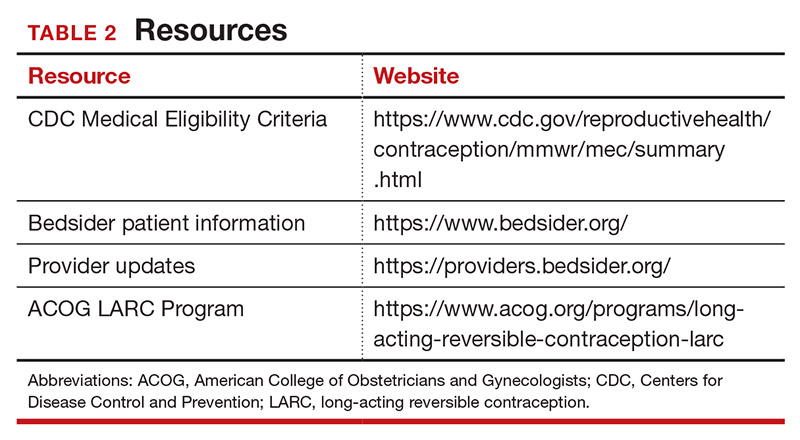

Tools are available for use. To ensure patient safety, we must evaluate the relative risks of each method given their specific medical history. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) provides a comprehensive reference for using each contraceptive method category with preexisting medical conditions on a scale from 1 (no restrictions) to 4 (unacceptable health risk) (TABLE 1).12 It is important to remember that pregnancy often poses a larger risk even than category 4 methods. With proper counseling and documentation, a category 3 method may be appropriate in some circumstances. The CDC MEC can serve as an excellent counseling tool and is available as a free smartphone app. The app can be downloaded via https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/mmwr/mec/summary.html (TABLE 2).

In a shared decision-making model, we contribute our medical knowledge, and the patient provides expertise on her own values and social context.13 By starting the contraceptive conversation with open-ended questions, we invite the patient to lead the discussion. We partner with them in finding a safe, effective method that is compatible with both the medical history and stated preferences. Bedsider.org has an interactive tool that allows patients to explore different contraceptive methods and compare their various characteristics. While tiered efficacy models may help us to organize our thinking as clinicians, it is important to recognize that patients may consider side effect profiles, nonreliance on clinicians for discontinuation, or other priorities above effectiveness.

Continue to: How to craft your approach...

How to craft your approach

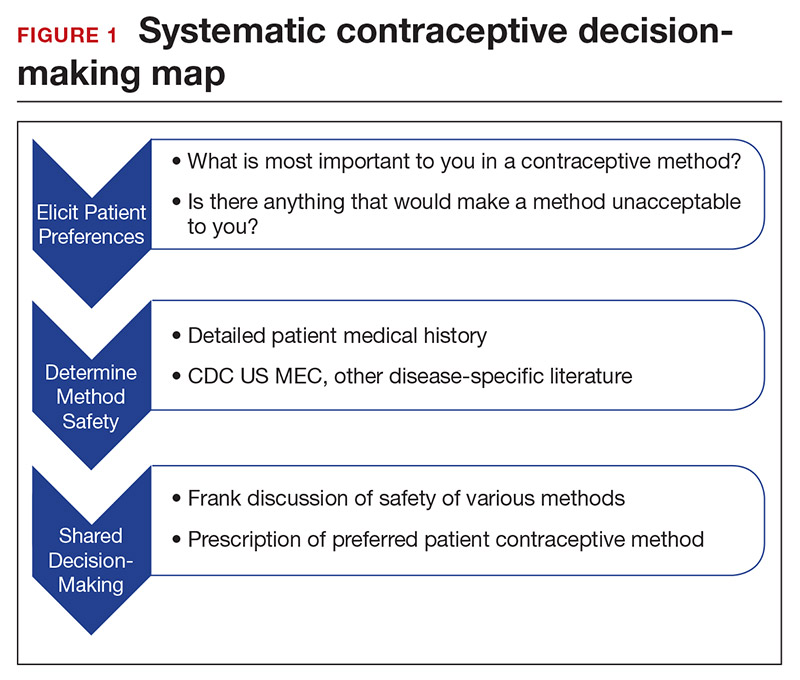

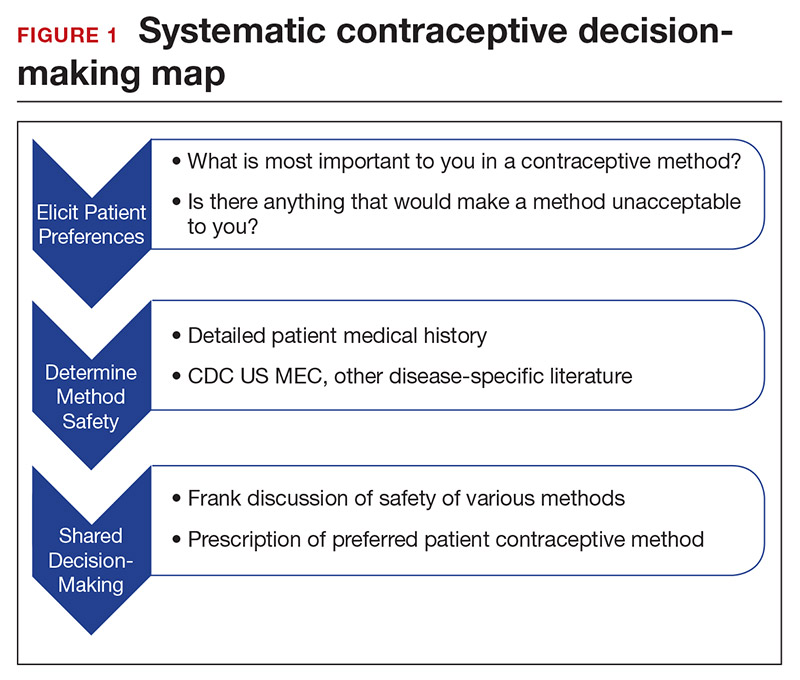

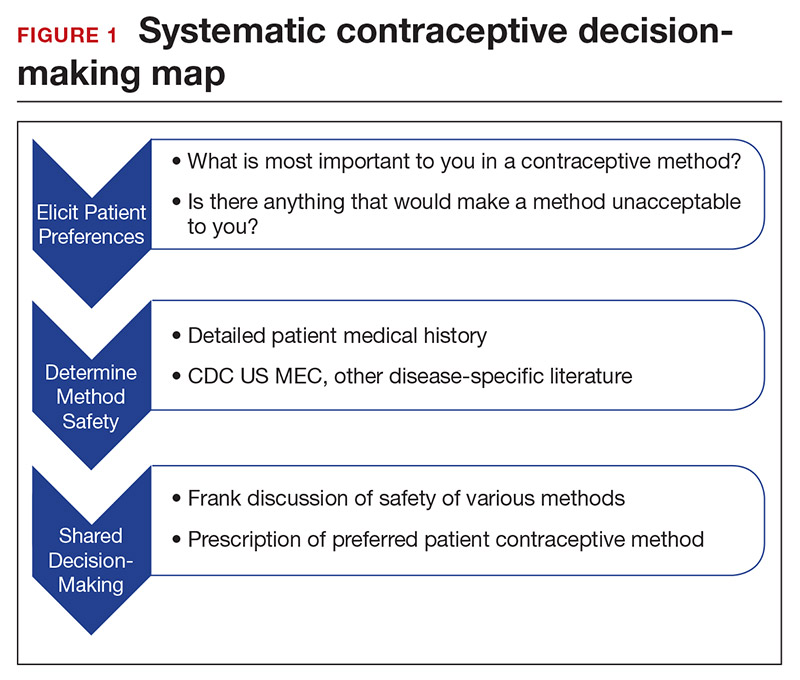

Developing a systematic approach to the medically complex patient seeking contraception can help to change an initially daunting task into a fulfilling experience (FIGURE 1). Begin by eliciting patient priorities. Then frame the discussion around them, rather than around efficacy. Although anecdotal reasoning can initially be frustrating (“My best friend’s IUD was really painful and I don’t want anything like that inside me!”), learning about these experiences prior to counseling can be incredibly informative. Ask detailed questions about medical comorbidities, as these subtleties may change the relative safety of each method. Finally, engage the patient in a frank discussion of the relative merits, safety, and use of all medically appropriate contraceptive methods. The right method is the method that the patient will use.

CASE Continued: Applying our counseling method

Upon open-ended questioning, the patient tells you that she absolutely cannot be on a contraceptive method that will make her gain weight. She has several friends who told her that they gained weight on “the shot” and “the implant.” She wants to avoid these at all costs and thinks she might want to take “the pill.” She also tells you that she is in college and that her daily routine varies significantly between weekdays and weekends. She definitely does not want to get pregnant until she has completed her education, which will be at least 3 years from now.

To best counsel this patient and arrive at the most appropriate contraceptive option for her, clarify her medical history and employ shared decision-making for her chosen method.

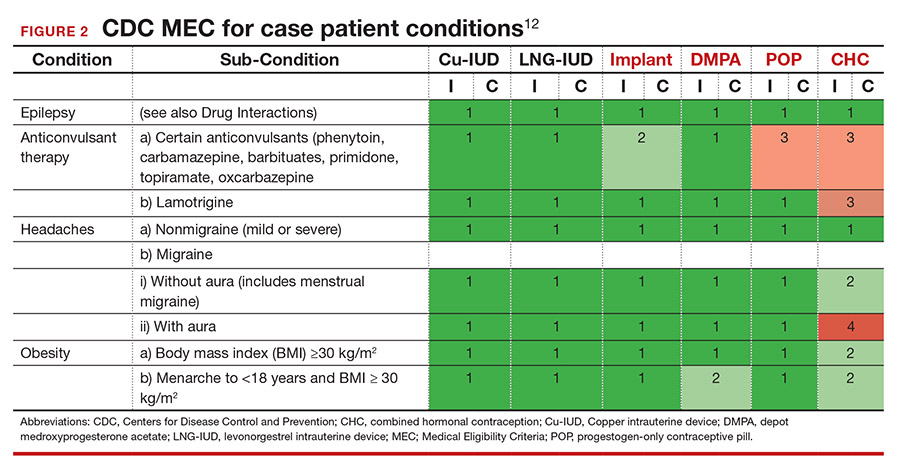

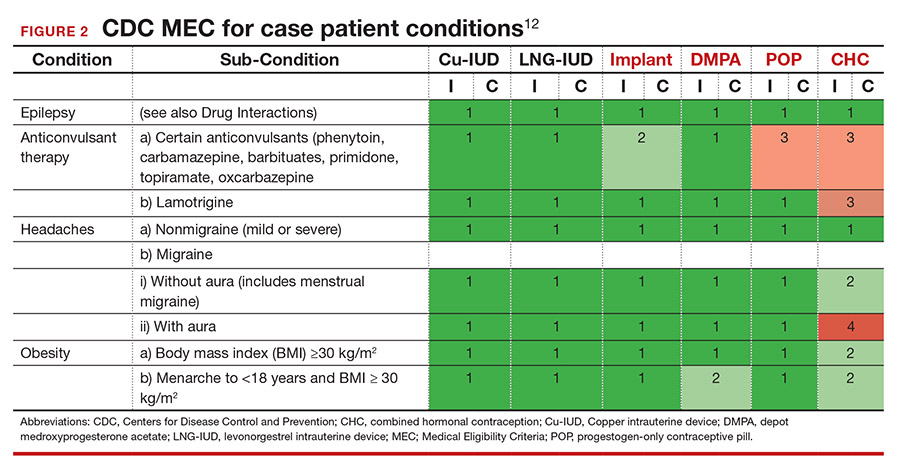

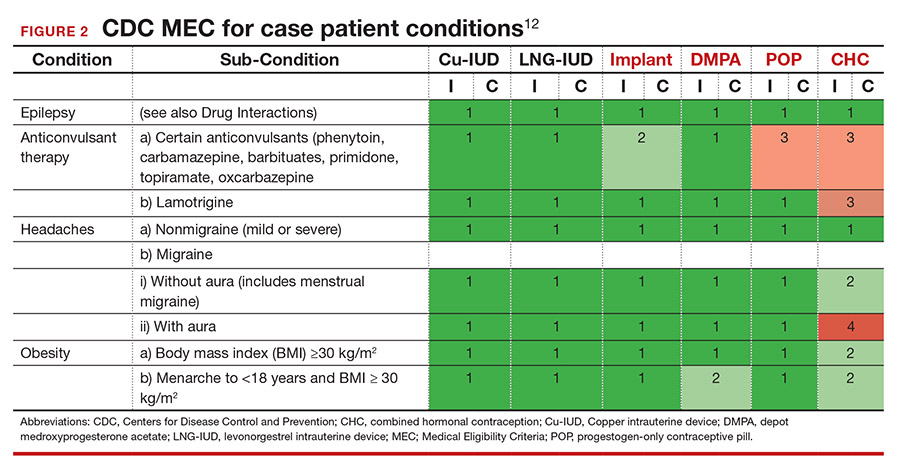

Probe her seizure history

She tells you that she has had seizures since she was a child, and the last one occurred 4 months ago when she ran out of her anticonvulsant medication. Her seizures have never been associated with her menses. This is an important piece of information. The frequency of catamenial seizures can be decreased with use of any method that suppresses ovulation, such as depot-medroxyprogesterone (DMPA) injections, continuous combined hormonal contraceptive (CHC) pills or ring, or the implant. Noncatamenial seizures also can be suppressed by DMPA, which increases the seizure threshold.14 Many anticonvulsants are metabolized through cytochrome P450 in the liver and, therefore, interact with all oral contraceptive formulations. However, levetiracetam is not among them and may be safely taken with progestin-only pills. At this point, all contraceptive methods remain CDC MEC category 1 (FIGURE 2).12

Ask migraine specifics

It is important to clarify whether or not the patient experiences aura with her migraines. She says that she always knows when a migraine is coming on because she sees floaters in her vision for about 30 minutes prior to the onset of excruciating headache. One tool that may aid in the diagnosis of aura is the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS).15 The presence of aura renders all CHCs category 4 by the CDC MEC.12 (See FIGURE 2.)

Discuss contraceptive pros and cons

Have a frank discussion about the relative risks and benefits of each method. For instance, although DMPA may improve the patient’s seizures, she has expressed a desire to avoid weight gain, and DMPA is the only method consistently shown in studies to do so.16 Her seizures are not associated with menses, so menstrual suppression is neither beneficial nor deleterious. Although her current medication levetiracetam does not influence the metabolism of contraceptive methods, many anticonvulsants do. Offer anticipatory guidance around seeking gynecologic consultation with any future seizure medication changes.

Allow for shared decision-making on a final choice

The patient indicated that she had been considering “the pill” when she made this appointment, but you have explained that CHCs are contraindicated for her. She is concerned that she will not be able to stick to the strict dosing schedule of a progestin-only pill. Although you inform her that the drospirinone-only pill has a more forgiving window, the patient decides that she wants a “set it and forget it” method and opts for an IUD.

CASE Resolved

Following recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), you provide for same-day insertion of a 52-mg levonorgestrel IUD.17 You use a paracervical block in addition to ibuprofen for pain control.18 The patient undergoes same-day testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and she understands that if a test is found to be positive, she can be treated without removing the IUD. You provide instruction on the importance of dual contraceptive use with barrier methods for the prevention of STIs. The patient is instructed on self-string checks, and she acknowledges that she will call if she has any concerns; no routine follow-up is required. She leaves her visit satisfied with her preferred, safe, effective contraceptive method in situ. ●

- Lauring JR, Lehman EB, Deimling TA, et al. Combined hormonal contraception use in reproductive-age women with contraindications to estrogen use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:330.e1-e7.

- Mendel A, Bernatsky S, Pineau CA, et al. Use of combined hormonal contraceptives among women with systemic lupus erythematosus with and without medical contraindications to oestrogen. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58:1259-1267.

- Judge CP, Zhao X, Sileanu FE, et al. Medical contraindications to estrogen and contraceptive use among women veterans. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:234.e1-234.e9.

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;360:1-8.

- Guttmacher Institute. Contraceptive use in the United States. April 2020. . Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Mosher WD, Lantos H, Burke AE. Obesity and contraceptive use among women 20–44 years of age in the United States: results from the 2011–15 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). Contraception. 2018:97:392-398.

- Dehlendorf C, Grumbach K, Schmittdiel JA, et al. Shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2017;95:452-455.

- Annovera [package insert]. Boca Raton, FL: TherapeuticsMD, Inc; 2020.

- Slynd [package insert]. Florham Park, NJ: Exeltis; 2019.

- Phexxi [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Evofem; 2020.

- , et al. Safety and efficacy in parous women of a 52-mg levonorgestrel-medicated intrauterine device: a 7-year randomized comparative study with the TCu380A. Contraception. 2016;93:498-506.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) for Contraceptive Use, 2016. . Accessed March 23, 2021.

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681-692.

- Dutton C, Foldvary‐Schaefer N. Contraception in women with epilepsy: pharmacokinetic interactions, contraceptive options, and management. Int Rev Neurobiol. 83;2008:113-134.

- Eriksen MK, Thomsen LL, Olesen J. The visual aura rating scale (VARS) for migraine aura diagnosis. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:801-810.

- ME, , , et al. Prospective study of weight change in new adolescent users of DMPA, NET-EN, COCs, nonusers and discontinuers of hormonal contraception. Contraception. 2010;81:30-34.

- Espey E, Hofler L. Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Practice bulletin 186. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-269.

- Akers AY, Steinway C, Sonalkar S, et al. Reducing pain during intrauterine device insertion: a randomized controlled trial in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:795-802.

CASE Patient-centered counseling for contraception

A 19-year-old woman (G0) with moderately well-controlled seizure disorder while taking levetiracetam, who reports migraines, and has a BMI of 32 kg/m2 presents to your office seeking contraception. She is currently sexually active with her second lifetime partner and uses condoms inconsistently. She is otherwise healthy and has no problems to report. Her last menstrual period (LMP) was 1 week ago, and a pregnancy test today is negative. How do you approach counseling for this patient?

The modern contraceptive patient

Our patients are becoming increasingly medically and socially complicated. Meeting the contraceptive needs of patients with multiple comorbidities can be a daunting task. Doing so in a patient-centered way that also recognizes the social contexts and intimacy inherent to contraceptive care can feel overwhelming. However, by employing a systematic approach to each patient, we can provide safe, effective, individualized care to our medically complex patients. Having a few “go-to tools” can streamline the process.

Medically complex patients are often told that they need to avoid pregnancy or optimize their health conditions prior to becoming pregnant, but they may not receive medically-appropriate contraception.1-3 Additionally, obesity rates in women of reproductive age in the United States are increasing, along with related medical complexities.4 Disparities in contraceptive access and use of particular methods exist by socioeconomic status, body mass index (BMI), age, and geography. 5,6 Evidence-based, shared decision making can improve contraceptive satisfaction.7

Clinicians need to stay attuned to all options. Staying current on available contraceptive methods can broaden clinicians’ thinking and allow patients more choices that are compatible with their medical needs. In the last 2 years alone, a 1-year combined estrogen-progestin vaginal ring, a drospirinone-only pill, and a nonhormonal spermicide have become available for prescription.8-10 Both 52 mg levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine devices (IUDs) are now US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for 6 years, and there is excellent data for off-label use to 7 years.11

Tools are available for use. To ensure patient safety, we must evaluate the relative risks of each method given their specific medical history. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) provides a comprehensive reference for using each contraceptive method category with preexisting medical conditions on a scale from 1 (no restrictions) to 4 (unacceptable health risk) (TABLE 1).12 It is important to remember that pregnancy often poses a larger risk even than category 4 methods. With proper counseling and documentation, a category 3 method may be appropriate in some circumstances. The CDC MEC can serve as an excellent counseling tool and is available as a free smartphone app. The app can be downloaded via https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/mmwr/mec/summary.html (TABLE 2).

In a shared decision-making model, we contribute our medical knowledge, and the patient provides expertise on her own values and social context.13 By starting the contraceptive conversation with open-ended questions, we invite the patient to lead the discussion. We partner with them in finding a safe, effective method that is compatible with both the medical history and stated preferences. Bedsider.org has an interactive tool that allows patients to explore different contraceptive methods and compare their various characteristics. While tiered efficacy models may help us to organize our thinking as clinicians, it is important to recognize that patients may consider side effect profiles, nonreliance on clinicians for discontinuation, or other priorities above effectiveness.

Continue to: How to craft your approach...

How to craft your approach

Developing a systematic approach to the medically complex patient seeking contraception can help to change an initially daunting task into a fulfilling experience (FIGURE 1). Begin by eliciting patient priorities. Then frame the discussion around them, rather than around efficacy. Although anecdotal reasoning can initially be frustrating (“My best friend’s IUD was really painful and I don’t want anything like that inside me!”), learning about these experiences prior to counseling can be incredibly informative. Ask detailed questions about medical comorbidities, as these subtleties may change the relative safety of each method. Finally, engage the patient in a frank discussion of the relative merits, safety, and use of all medically appropriate contraceptive methods. The right method is the method that the patient will use.

CASE Continued: Applying our counseling method

Upon open-ended questioning, the patient tells you that she absolutely cannot be on a contraceptive method that will make her gain weight. She has several friends who told her that they gained weight on “the shot” and “the implant.” She wants to avoid these at all costs and thinks she might want to take “the pill.” She also tells you that she is in college and that her daily routine varies significantly between weekdays and weekends. She definitely does not want to get pregnant until she has completed her education, which will be at least 3 years from now.

To best counsel this patient and arrive at the most appropriate contraceptive option for her, clarify her medical history and employ shared decision-making for her chosen method.

Probe her seizure history

She tells you that she has had seizures since she was a child, and the last one occurred 4 months ago when she ran out of her anticonvulsant medication. Her seizures have never been associated with her menses. This is an important piece of information. The frequency of catamenial seizures can be decreased with use of any method that suppresses ovulation, such as depot-medroxyprogesterone (DMPA) injections, continuous combined hormonal contraceptive (CHC) pills or ring, or the implant. Noncatamenial seizures also can be suppressed by DMPA, which increases the seizure threshold.14 Many anticonvulsants are metabolized through cytochrome P450 in the liver and, therefore, interact with all oral contraceptive formulations. However, levetiracetam is not among them and may be safely taken with progestin-only pills. At this point, all contraceptive methods remain CDC MEC category 1 (FIGURE 2).12

Ask migraine specifics

It is important to clarify whether or not the patient experiences aura with her migraines. She says that she always knows when a migraine is coming on because she sees floaters in her vision for about 30 minutes prior to the onset of excruciating headache. One tool that may aid in the diagnosis of aura is the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS).15 The presence of aura renders all CHCs category 4 by the CDC MEC.12 (See FIGURE 2.)

Discuss contraceptive pros and cons

Have a frank discussion about the relative risks and benefits of each method. For instance, although DMPA may improve the patient’s seizures, she has expressed a desire to avoid weight gain, and DMPA is the only method consistently shown in studies to do so.16 Her seizures are not associated with menses, so menstrual suppression is neither beneficial nor deleterious. Although her current medication levetiracetam does not influence the metabolism of contraceptive methods, many anticonvulsants do. Offer anticipatory guidance around seeking gynecologic consultation with any future seizure medication changes.

Allow for shared decision-making on a final choice

The patient indicated that she had been considering “the pill” when she made this appointment, but you have explained that CHCs are contraindicated for her. She is concerned that she will not be able to stick to the strict dosing schedule of a progestin-only pill. Although you inform her that the drospirinone-only pill has a more forgiving window, the patient decides that she wants a “set it and forget it” method and opts for an IUD.

CASE Resolved

Following recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), you provide for same-day insertion of a 52-mg levonorgestrel IUD.17 You use a paracervical block in addition to ibuprofen for pain control.18 The patient undergoes same-day testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and she understands that if a test is found to be positive, she can be treated without removing the IUD. You provide instruction on the importance of dual contraceptive use with barrier methods for the prevention of STIs. The patient is instructed on self-string checks, and she acknowledges that she will call if she has any concerns; no routine follow-up is required. She leaves her visit satisfied with her preferred, safe, effective contraceptive method in situ. ●

CASE Patient-centered counseling for contraception

A 19-year-old woman (G0) with moderately well-controlled seizure disorder while taking levetiracetam, who reports migraines, and has a BMI of 32 kg/m2 presents to your office seeking contraception. She is currently sexually active with her second lifetime partner and uses condoms inconsistently. She is otherwise healthy and has no problems to report. Her last menstrual period (LMP) was 1 week ago, and a pregnancy test today is negative. How do you approach counseling for this patient?

The modern contraceptive patient

Our patients are becoming increasingly medically and socially complicated. Meeting the contraceptive needs of patients with multiple comorbidities can be a daunting task. Doing so in a patient-centered way that also recognizes the social contexts and intimacy inherent to contraceptive care can feel overwhelming. However, by employing a systematic approach to each patient, we can provide safe, effective, individualized care to our medically complex patients. Having a few “go-to tools” can streamline the process.

Medically complex patients are often told that they need to avoid pregnancy or optimize their health conditions prior to becoming pregnant, but they may not receive medically-appropriate contraception.1-3 Additionally, obesity rates in women of reproductive age in the United States are increasing, along with related medical complexities.4 Disparities in contraceptive access and use of particular methods exist by socioeconomic status, body mass index (BMI), age, and geography. 5,6 Evidence-based, shared decision making can improve contraceptive satisfaction.7

Clinicians need to stay attuned to all options. Staying current on available contraceptive methods can broaden clinicians’ thinking and allow patients more choices that are compatible with their medical needs. In the last 2 years alone, a 1-year combined estrogen-progestin vaginal ring, a drospirinone-only pill, and a nonhormonal spermicide have become available for prescription.8-10 Both 52 mg levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine devices (IUDs) are now US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for 6 years, and there is excellent data for off-label use to 7 years.11

Tools are available for use. To ensure patient safety, we must evaluate the relative risks of each method given their specific medical history. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) provides a comprehensive reference for using each contraceptive method category with preexisting medical conditions on a scale from 1 (no restrictions) to 4 (unacceptable health risk) (TABLE 1).12 It is important to remember that pregnancy often poses a larger risk even than category 4 methods. With proper counseling and documentation, a category 3 method may be appropriate in some circumstances. The CDC MEC can serve as an excellent counseling tool and is available as a free smartphone app. The app can be downloaded via https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/mmwr/mec/summary.html (TABLE 2).

In a shared decision-making model, we contribute our medical knowledge, and the patient provides expertise on her own values and social context.13 By starting the contraceptive conversation with open-ended questions, we invite the patient to lead the discussion. We partner with them in finding a safe, effective method that is compatible with both the medical history and stated preferences. Bedsider.org has an interactive tool that allows patients to explore different contraceptive methods and compare their various characteristics. While tiered efficacy models may help us to organize our thinking as clinicians, it is important to recognize that patients may consider side effect profiles, nonreliance on clinicians for discontinuation, or other priorities above effectiveness.

Continue to: How to craft your approach...

How to craft your approach

Developing a systematic approach to the medically complex patient seeking contraception can help to change an initially daunting task into a fulfilling experience (FIGURE 1). Begin by eliciting patient priorities. Then frame the discussion around them, rather than around efficacy. Although anecdotal reasoning can initially be frustrating (“My best friend’s IUD was really painful and I don’t want anything like that inside me!”), learning about these experiences prior to counseling can be incredibly informative. Ask detailed questions about medical comorbidities, as these subtleties may change the relative safety of each method. Finally, engage the patient in a frank discussion of the relative merits, safety, and use of all medically appropriate contraceptive methods. The right method is the method that the patient will use.

CASE Continued: Applying our counseling method

Upon open-ended questioning, the patient tells you that she absolutely cannot be on a contraceptive method that will make her gain weight. She has several friends who told her that they gained weight on “the shot” and “the implant.” She wants to avoid these at all costs and thinks she might want to take “the pill.” She also tells you that she is in college and that her daily routine varies significantly between weekdays and weekends. She definitely does not want to get pregnant until she has completed her education, which will be at least 3 years from now.

To best counsel this patient and arrive at the most appropriate contraceptive option for her, clarify her medical history and employ shared decision-making for her chosen method.

Probe her seizure history

She tells you that she has had seizures since she was a child, and the last one occurred 4 months ago when she ran out of her anticonvulsant medication. Her seizures have never been associated with her menses. This is an important piece of information. The frequency of catamenial seizures can be decreased with use of any method that suppresses ovulation, such as depot-medroxyprogesterone (DMPA) injections, continuous combined hormonal contraceptive (CHC) pills or ring, or the implant. Noncatamenial seizures also can be suppressed by DMPA, which increases the seizure threshold.14 Many anticonvulsants are metabolized through cytochrome P450 in the liver and, therefore, interact with all oral contraceptive formulations. However, levetiracetam is not among them and may be safely taken with progestin-only pills. At this point, all contraceptive methods remain CDC MEC category 1 (FIGURE 2).12

Ask migraine specifics

It is important to clarify whether or not the patient experiences aura with her migraines. She says that she always knows when a migraine is coming on because she sees floaters in her vision for about 30 minutes prior to the onset of excruciating headache. One tool that may aid in the diagnosis of aura is the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS).15 The presence of aura renders all CHCs category 4 by the CDC MEC.12 (See FIGURE 2.)

Discuss contraceptive pros and cons

Have a frank discussion about the relative risks and benefits of each method. For instance, although DMPA may improve the patient’s seizures, she has expressed a desire to avoid weight gain, and DMPA is the only method consistently shown in studies to do so.16 Her seizures are not associated with menses, so menstrual suppression is neither beneficial nor deleterious. Although her current medication levetiracetam does not influence the metabolism of contraceptive methods, many anticonvulsants do. Offer anticipatory guidance around seeking gynecologic consultation with any future seizure medication changes.

Allow for shared decision-making on a final choice

The patient indicated that she had been considering “the pill” when she made this appointment, but you have explained that CHCs are contraindicated for her. She is concerned that she will not be able to stick to the strict dosing schedule of a progestin-only pill. Although you inform her that the drospirinone-only pill has a more forgiving window, the patient decides that she wants a “set it and forget it” method and opts for an IUD.

CASE Resolved

Following recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), you provide for same-day insertion of a 52-mg levonorgestrel IUD.17 You use a paracervical block in addition to ibuprofen for pain control.18 The patient undergoes same-day testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and she understands that if a test is found to be positive, she can be treated without removing the IUD. You provide instruction on the importance of dual contraceptive use with barrier methods for the prevention of STIs. The patient is instructed on self-string checks, and she acknowledges that she will call if she has any concerns; no routine follow-up is required. She leaves her visit satisfied with her preferred, safe, effective contraceptive method in situ. ●

- Lauring JR, Lehman EB, Deimling TA, et al. Combined hormonal contraception use in reproductive-age women with contraindications to estrogen use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:330.e1-e7.

- Mendel A, Bernatsky S, Pineau CA, et al. Use of combined hormonal contraceptives among women with systemic lupus erythematosus with and without medical contraindications to oestrogen. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58:1259-1267.

- Judge CP, Zhao X, Sileanu FE, et al. Medical contraindications to estrogen and contraceptive use among women veterans. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:234.e1-234.e9.

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;360:1-8.

- Guttmacher Institute. Contraceptive use in the United States. April 2020. . Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Mosher WD, Lantos H, Burke AE. Obesity and contraceptive use among women 20–44 years of age in the United States: results from the 2011–15 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). Contraception. 2018:97:392-398.

- Dehlendorf C, Grumbach K, Schmittdiel JA, et al. Shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2017;95:452-455.

- Annovera [package insert]. Boca Raton, FL: TherapeuticsMD, Inc; 2020.

- Slynd [package insert]. Florham Park, NJ: Exeltis; 2019.

- Phexxi [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Evofem; 2020.

- , et al. Safety and efficacy in parous women of a 52-mg levonorgestrel-medicated intrauterine device: a 7-year randomized comparative study with the TCu380A. Contraception. 2016;93:498-506.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) for Contraceptive Use, 2016. . Accessed March 23, 2021.

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681-692.

- Dutton C, Foldvary‐Schaefer N. Contraception in women with epilepsy: pharmacokinetic interactions, contraceptive options, and management. Int Rev Neurobiol. 83;2008:113-134.

- Eriksen MK, Thomsen LL, Olesen J. The visual aura rating scale (VARS) for migraine aura diagnosis. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:801-810.

- ME, , , et al. Prospective study of weight change in new adolescent users of DMPA, NET-EN, COCs, nonusers and discontinuers of hormonal contraception. Contraception. 2010;81:30-34.

- Espey E, Hofler L. Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Practice bulletin 186. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-269.

- Akers AY, Steinway C, Sonalkar S, et al. Reducing pain during intrauterine device insertion: a randomized controlled trial in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:795-802.

- Lauring JR, Lehman EB, Deimling TA, et al. Combined hormonal contraception use in reproductive-age women with contraindications to estrogen use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:330.e1-e7.

- Mendel A, Bernatsky S, Pineau CA, et al. Use of combined hormonal contraceptives among women with systemic lupus erythematosus with and without medical contraindications to oestrogen. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58:1259-1267.

- Judge CP, Zhao X, Sileanu FE, et al. Medical contraindications to estrogen and contraceptive use among women veterans. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:234.e1-234.e9.

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;360:1-8.

- Guttmacher Institute. Contraceptive use in the United States. April 2020. . Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Mosher WD, Lantos H, Burke AE. Obesity and contraceptive use among women 20–44 years of age in the United States: results from the 2011–15 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). Contraception. 2018:97:392-398.

- Dehlendorf C, Grumbach K, Schmittdiel JA, et al. Shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2017;95:452-455.

- Annovera [package insert]. Boca Raton, FL: TherapeuticsMD, Inc; 2020.

- Slynd [package insert]. Florham Park, NJ: Exeltis; 2019.

- Phexxi [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Evofem; 2020.

- , et al. Safety and efficacy in parous women of a 52-mg levonorgestrel-medicated intrauterine device: a 7-year randomized comparative study with the TCu380A. Contraception. 2016;93:498-506.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) for Contraceptive Use, 2016. . Accessed March 23, 2021.

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681-692.

- Dutton C, Foldvary‐Schaefer N. Contraception in women with epilepsy: pharmacokinetic interactions, contraceptive options, and management. Int Rev Neurobiol. 83;2008:113-134.

- Eriksen MK, Thomsen LL, Olesen J. The visual aura rating scale (VARS) for migraine aura diagnosis. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:801-810.

- ME, , , et al. Prospective study of weight change in new adolescent users of DMPA, NET-EN, COCs, nonusers and discontinuers of hormonal contraception. Contraception. 2010;81:30-34.

- Espey E, Hofler L. Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Practice bulletin 186. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-269.

- Akers AY, Steinway C, Sonalkar S, et al. Reducing pain during intrauterine device insertion: a randomized controlled trial in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:795-802.

Optimize your treatment of endometriosis by using an FDA-approved hormonal medication

Women with endometriosis often present for medical care for one or more of the following health issues: pelvic pain, infertility, and/or an adnexal cyst (endometrioma). For women with moderate or severe pelvic pain and laparoscopically diagnosed endometriosis, hormone therapy is often necessary to achieve maximal long-term reduction in pain and optimize health. I focus on opportunities to optimize hormonal treatment of endometriosis in this editorial.

When plan A is not working, move expeditiously to plan B

Cyclic or continuous combination estrogen-progestin contraceptives are commonly prescribed to treat pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. Although endometriosis pain may initially improve with estrogen-progestin contraceptives, many women on this medication will eventually report that they have worsening pelvic pain that adversely impacts their daily activities. Surprisingly, clinicians often continue to prescribe estrogen-progestin contraceptives even after the patient reports that the treatment is not effective, and their pain continues to be bothersome.

Patients benefit when they have access to the full range of hormone treatments that have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of moderate to severe pelvic pain caused by endometriosis (TABLE). In the situation where an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is no longer effective at reducing the pelvic pain, I will often offer the patient the option of norethindrone acetate (NEA) or elagolix treatment. My experience is that stopping the estrogen-progestin contraceptive and starting NEA or elagolix will result in a significant decrease in pain symptoms and improvement in the patient’s quality of life.

Other FDA-approved options to treat pelvic pain caused by endometriosis include depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injectable suspension, depot leuprolide acetate, goserelin implant, and danazol. I do not routinely prescribe depot medroxyprogesterone acetate because some patients report new onset or worsening symptoms of depression on the medication. I prescribe depot-leuprolide acetate less often than in the past, because many patients report moderate to severe hypoestrogenic symptoms on this medication. In women taking depot-leuprolide acetate, moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms can be improved by prescribing NEA pills, but the alternative of norethindrone monotherapy is less expensive. I seldom use goserelin or danazol in my practice. The needle required to place the goserelin implant has a diameter of approximately 1.7 mm (16 gauge) or 2.1 mm (14 gauge), for the 3.6 mg and 10 mg doses, respectively. The large diameter of the needle can cause pain and bruising at the implant site. As a comparison, the progestin subdermal implant needle is approximately 2.1 mm in diameter. Danazol is associated with weight gain, and most women prefer to avoid this side effect.

Continue to: Norethindrone acetate...

Norethindrone acetate

NEA 5 mg daily is approved by the FDA to treat endometriosis.1 NEA was approved at a time when large controlled clinical trials were not routinely required for a medicine to be approved. The data to support NEA treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis is based on cohort studies. In a study of 194 women, median age 21 years with moderate to severe pelvic pain and surgically proven endometriosis, the effect of NEA on pelvic pain was explored.2 The initial dose of NEA was 5 mg daily. If the patient did not achieve a reduction in pelvic pain and amenorrhea on the NEA dose of 5 mg daily, the dose was increased by 2.5 mg every 2 weeks, up to a maximum of 15 mg, until amenorrhea and/or a decrease in pelvic pain was achieved. Ninety-five percent of the women in this cohort had previously been treated with an estrogen-progestin contraceptive or a GnRH antagonist and had discontinued those medications because of inadequate control of pelvic pain or because of side effects of the medication.

In this large cohort, 65% of women reported significant improvement in pelvic pain, with a median pain score of 5 before treatment and 0 following NEA treatment. About 55% of the women reported no side effects. The most commonly reported side effects were weight gain (16%; mean weight gain, 3.1 kg), acne (10%), mood lability (9%), hot flashes (8%), depression (6%), scalp hair loss (4%), headache (4%), nausea (3%), and deepening of the voice (1%). (In this study women could report more than one side effect.)

In another cohort study of 52 women with pelvic pain and surgically confirmed endometriosis, NEA treatment resulted in pain relief in 94% of the women.3 Breakthrough bleeding was a common side effect, reported by 58% of participants. The investigators concluded that NEA treatment was a “cost-effective alternative with relatively mild side effects in the treatment of symptomatic endometriosis.” A conclusion which I endorse.

NEA has been reported to effectively treat ovarian endometriomas and rectovaginal endometriosis.4,5 In a cohort of 18 women who had previously had the surgical resection of an ovarian endometriosis cyst and had postoperative recurrence of pelvic pain and ovarian endometriosis, treatment was initiated with an escalating NEA regimen.4 Treatment was initiated with NEA 5 mg daily, with the dosage increased every 2 weeks by 2.5 mg until amenorrhea was established. Most women achieved amenorrhea with NEA 5 mg daily, and 89% had reduced pelvic pain. The investigators reported complete regression of the endometriosis cyst(s) in 74% of the women. In my experience, NEA does not result in complete regression of endometriosis cysts, but it does cause a reduction in cyst diameter and total volume.

In a retrospective cohort study, 61 women with pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis had 5 years of treatment with NEA 2.5 mg or 5.0 mg daily.5 NEA treatment resulted in a decrease in dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, and dyschezia. The most common side effects attributed to NEA treatment were weight gain (30%), vaginal bleeding (23%), decreased libido (11%), headache (9%), bloating or swelling (8%), depression (7%), and acne (5%). In women who had sequential imaging studies, NEA treatment resulted in a decrease in rectovaginal lesion volume, stable disease volume, or an increase in lesion volume in 56%, 32%, and 12% of the women, respectively. The investigators concluded that for women with rectovaginal endometriosis, NEA treatment is a low-cost option for long-term treatment.

In my practice, I do not prescribe NEA at doses greater than 5 mg daily. There are case reports that NEA at a dose of ≥10 mg daily is associated with the development of a hepatic adenoma,6 elevated liver transaminase concentration,7 and jaundice.8 If NEA 5 mg daily is not effective in controlling pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, I stop the NEA and start a GnRH analogue, most often elagolix.

NEA 5 mg is not FDA approved as a contraceptive. However, norethindrone 0.35 mg daily, also known as the “mini-pill”, is approved as a progestin-only contraceptive.9 NEA is rapidly and completely deacetylated to norethindrone, and the disposition of oral NEA is indistinguishable from that of norethindrone.1 Since norethindrone 0.35 mg daily is approved as a contraceptive, it is highly likely that NEA 5 mg has contraceptive properties if taken daily.

Continue to: Elagolix...

Elagolix

Elagolix is FDA approved for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. I reviewed the key studies resulting in FDA approval in the November 2018 issue of

In the Elaris Endometriosis-I study, 872 women with endometriosis and pelvic pain were randomly assigned to treatment with 1 of 2 doses of elagolix (high-dose [200 mg twice daily] and low-dose [150 mg once daily]) or placebo.11 After 3 months of therapy, a clinically meaningful reduction in dysmenorrhea pain was reported by 76%, 46%, and 20% of the women in the high-dose elagolix, low-dose elagolix, and placebo groups, respectively (P<.001 for comparisons of elagolix to placebo). After 3 months of therapy, a clinically meaningful reduction in nonmenstrual pain or decreased or stable use of rescue analgesics was reported by 55%, 50%, and 37% of the women in the high-dose elagolix, low-dose elagolix, and placebo groups, respectively (P<.01 low-dose elagolix vs placebo and P<.001 high-dose elagolix vs placebo).

Hot flashes that were severe enough to be reported as an adverse event by the study participants were reported by 42%, 24%, and 7% of the women in the high-dose elagolix, low-dose elagolix, and placebo groups. Bone density was measured at baseline and after 6 months of treatment. Lumbar bone density changes were -2.61%, -0.32%, and +0.47% and hip femoral neck bone density changes were -1.89%, -0.39%, and +0.02% in the high-dose elagolix, low-dose elagolix, and placebo groups, respectively.

Another large clinical trial of elagolix for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, Elaris EM-II, involving 817 women, produced results very similar to those reported in Elaris EM-I. The elagolix continuation studies, Elaris EM-III and -IV, demonstrated efficacy and safety of elagolix through 12 months of treatment.12

In my 2018 review,10 I noted that elagolix dose adjustment can be utilized to attempt to achieve maximal pain relief with minimal vasomotor symptoms. Elagolix at 200 mg twice daily produces a mean estradiol concentration of 12 pg/mL, whereas elagolix at 150 mg daily resulted in a mean estradiol concentration of 41 pg/mL.13 The estrogen threshold hypothesis posits that in women with endometriosis a stable estradiol concentration of 20 to 30 pg/mL is often associated with decreased pain and fewer vasomotor events.14 To achieve the target estradiol range of 20 to 30 pg/mL, I often initiate elagolix treatment with 200 mg twice daily. This enables a rapid onset of amenorrhea and a reduction in pelvic pain. Once amenorrhea has been achieved and a decrease in pelvic pain has occurred, I adjust the dose downward to 200 mg twice daily on even calendar days of each month and 200 mg once daily on odd calendar days each month. Some women will have continued pain relief and amenorrhea when the dose is further decreased to 200 mg once daily. If bothersome bleeding recurs and/or pain symptoms increase in severity, the dose can be increased to 200 mg twice daily or an alternating regimen of 200 mg twice daily and 200 mg once daily, every 2 days. An alternative to dose adjustment is to combine elagolix with NEA, which can reduce the severity of hot flashes and reduce bone loss caused by hypoestrogenism.15,16

Health insurers and pharmacy benefits managers may require a prior authorization before approving and dispensing elagolix. The prior authorization process can be burdensome for clinicians, consuming limited healthcare resources, contributing to burnout and frustrating patients.17 Elagolix is less expensive than depot-leuprolide acetate and nafarelin nasal spray and somewhat more expensive than a goserelin implant.18,19

Elagolix is not approved as a contraceptive. In the Elaris EM-I and -II trials women were advised to use 2 forms of contraception, although pregnancies did occur. There were 6 pregnancies among 475 women taking elagolix 150 mg daily and 2 pregnancies among 477 women taking elagolix 200 mg twice daily.20 Women taking elagolix should be advised to use a contraceptive, but not an estrogen-progestin contraceptive.

Continue to: Do not use opioids to treat chronic pelvic pain caused by endometriosis...

Do not use opioids to treat chronic pelvic pain caused by endometriosis

One of the greatest public health tragedies of our era is the opioid misuse epidemic. Hundreds of thousands of deaths have been caused by opioid misuse. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that for the 12-month period ending in May 2020, there were 81,000 opioid-related deaths, the greatest number ever reported in a 12-month period.21 Many authorities believe that in the United States opioid medications have been over-prescribed, contributing to the opioid misuse epidemic. There is little evidence that chronic pelvic pain is optimally managed by chronic treatment with an opioid.22,23 Prescribing opioids to vulnerable individuals to treat chronic pelvic pain may result in opioid dependency and adversely affect the patient’s health. It is best to pledge not to prescribe an opioid medication for a woman with chronic pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. In situations when pelvic pain is difficult to control with hormonal therapy and nonopioid pain medications, referral to a specialty pain practice may be warranted.

Post–conservative surgery hormone treatment reduces pelvic pain recurrence

In a meta-analysis of 14 studies that reported on endometriosis recurrence rates following conservative surgery, recurrence (defined as recurrent pelvic pain or an imaging study showing recurrent endometriosis) was significantly reduced with the use of hormone treatment compared with expectant management or placebo treatment.24 The postoperative relative risk of endometriosis recurrence was reduced by 83% with progestin treatment, 64% with estrogen-progestin contraceptive treatment, and 38% with GnRH analogue treatment. Overall, the number of patients that needed to be treated to prevent one endometriosis recurrence was 10, assuming a recurrence rate of 25% in the placebo treatment or expectant management groups.

For women with pelvic pain caused by endometriosis who develop a recurrence of pelvic pain while on postoperative hormone treatment, it is important for the prescribing clinician to be flexible and consider changing the hormone regimen. For example, if a postoperative patient is treated with a continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptive and develops recurrent pain, I will stop the contraceptive and initiate treatment with either NEA or elagolix.

Capitalize on opportunities to improve the medical care of women with endometriosis

Early diagnosis of endometriosis can be facilitated by recognizing that the condition is a common cause of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea. In 5 studies involving 1,187 women, the mean length of time from onset of pelvic pain symptoms to diagnosis of endometriosis was 8.6 years.25 If a woman with pelvic pain caused by endometriosis has not had sufficient pain relief with one brand of continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptive, it is best not to prescribe an alternative brand but rather to switch to a progestin-only treatment or a GnRH antagonist. If plan A is not working, move expeditiously to plan B. ●

- Aygestin [package insert]. Barr Laboratories: Pomona, NY; 2007.

- Kaser DJ, Missmer SA, Berry KF, et al. Use of norethindrone acetate alone for postoperative suppression of endometriosis symptoms. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25:105-108.

- Muneyyirci-Delale O, Karacan M. Effect of norethindrone acetate in the treatment of symptomatic endometriosis. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 1998;43:24-27.

- Muneyyirci-Delale O, Anopa J, Charles C, et al. Medical management of recurrent endometrioma with long-term norethindrone acetate. Int J Women Health. 2012;4:149-154.

- Morotti M, Venturini PL, Biscaldi E, et al. Efficacy and acceptability of long-term norethindrone acetate for the treatment of rectovaginal endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2017;213:4-10.

- Brady PC, Missmer SA, Laufer MR. Hepatic adenomas in adolescents and young women with endometriosis treated with norethindrone acetate. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30:422-424.

- Choudhary NS, Bodh V, Chaudhari S, et al. Norethisterone related drug induced liver injury: a series of 3 cases. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2017;7:266- 268.

- Perez-Mera RA, Shields CE. Jaundice associated with norethindrone acetate therapy. N Engl J Med. 1962;267:1137-1138.

- Camila [package insert]. Mayne Pharma Inc: Greenville, NC; 2018.

- Barbieri RL. Elagolix: a new treatment for pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. OBG Manag. 2018;30:10,12-14, 20.

- Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:28-40.

- Surrey E, Taylor HS, Giudice L, et al. Long-term outcomes of elagolix in women with endometriosis: results from two extension studies. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:147-160.

- Orilissa [package insert]. AbbVie Inc; North Chicago, IL; 2018.

- Barbieri RL. Hormonal treatment of endometriosis: the estrogen threshold hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:740-745.

- Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, et al. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:16-24.

- Gallagher JS, Missmer SA, Hornstein MD, et al. Long-term effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and add-back in adolescent endometriosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2018;31:376- 381.

- Miller A, Shor R, Waites T, et al. Prior authorization reform for better patient care. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1937-1939.

- Depot-leuprolide acetate. Good Rx website. https://www.goodrx.com/. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- Goserelin. Good Rx website. https://www .goodrx.com/. Accessed January 22, 2021

- Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:28-40.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose deaths accelerating during COVID19. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020 /p1218-overdose-deaths-covid-19.html. Reviewed December 18, 2020. Accessed March 24, 2021.

- Till SR, As-Sanie S. 3 cases of chronic pelvic pain with nonsurgical, nonopioid therapies. OBG Manag. 2018;30:41-48.

- Steele A. Opioid use and depression in chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41:491-501.

- Zakhari A, Delpero E, McKeown S, et al. Endometriosis recurrence following post-operative hormonal suppression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2021;27:96- 107.

- Barbieri RL. Why are there delays in the diagnosis of endometriosis? OBG Manag. 2017;29:8, 10-11, 16.

Women with endometriosis often present for medical care for one or more of the following health issues: pelvic pain, infertility, and/or an adnexal cyst (endometrioma). For women with moderate or severe pelvic pain and laparoscopically diagnosed endometriosis, hormone therapy is often necessary to achieve maximal long-term reduction in pain and optimize health. I focus on opportunities to optimize hormonal treatment of endometriosis in this editorial.

When plan A is not working, move expeditiously to plan B

Cyclic or continuous combination estrogen-progestin contraceptives are commonly prescribed to treat pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. Although endometriosis pain may initially improve with estrogen-progestin contraceptives, many women on this medication will eventually report that they have worsening pelvic pain that adversely impacts their daily activities. Surprisingly, clinicians often continue to prescribe estrogen-progestin contraceptives even after the patient reports that the treatment is not effective, and their pain continues to be bothersome.

Patients benefit when they have access to the full range of hormone treatments that have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of moderate to severe pelvic pain caused by endometriosis (TABLE). In the situation where an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is no longer effective at reducing the pelvic pain, I will often offer the patient the option of norethindrone acetate (NEA) or elagolix treatment. My experience is that stopping the estrogen-progestin contraceptive and starting NEA or elagolix will result in a significant decrease in pain symptoms and improvement in the patient’s quality of life.

Other FDA-approved options to treat pelvic pain caused by endometriosis include depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injectable suspension, depot leuprolide acetate, goserelin implant, and danazol. I do not routinely prescribe depot medroxyprogesterone acetate because some patients report new onset or worsening symptoms of depression on the medication. I prescribe depot-leuprolide acetate less often than in the past, because many patients report moderate to severe hypoestrogenic symptoms on this medication. In women taking depot-leuprolide acetate, moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms can be improved by prescribing NEA pills, but the alternative of norethindrone monotherapy is less expensive. I seldom use goserelin or danazol in my practice. The needle required to place the goserelin implant has a diameter of approximately 1.7 mm (16 gauge) or 2.1 mm (14 gauge), for the 3.6 mg and 10 mg doses, respectively. The large diameter of the needle can cause pain and bruising at the implant site. As a comparison, the progestin subdermal implant needle is approximately 2.1 mm in diameter. Danazol is associated with weight gain, and most women prefer to avoid this side effect.

Continue to: Norethindrone acetate...

Norethindrone acetate

NEA 5 mg daily is approved by the FDA to treat endometriosis.1 NEA was approved at a time when large controlled clinical trials were not routinely required for a medicine to be approved. The data to support NEA treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis is based on cohort studies. In a study of 194 women, median age 21 years with moderate to severe pelvic pain and surgically proven endometriosis, the effect of NEA on pelvic pain was explored.2 The initial dose of NEA was 5 mg daily. If the patient did not achieve a reduction in pelvic pain and amenorrhea on the NEA dose of 5 mg daily, the dose was increased by 2.5 mg every 2 weeks, up to a maximum of 15 mg, until amenorrhea and/or a decrease in pelvic pain was achieved. Ninety-five percent of the women in this cohort had previously been treated with an estrogen-progestin contraceptive or a GnRH antagonist and had discontinued those medications because of inadequate control of pelvic pain or because of side effects of the medication.

In this large cohort, 65% of women reported significant improvement in pelvic pain, with a median pain score of 5 before treatment and 0 following NEA treatment. About 55% of the women reported no side effects. The most commonly reported side effects were weight gain (16%; mean weight gain, 3.1 kg), acne (10%), mood lability (9%), hot flashes (8%), depression (6%), scalp hair loss (4%), headache (4%), nausea (3%), and deepening of the voice (1%). (In this study women could report more than one side effect.)

In another cohort study of 52 women with pelvic pain and surgically confirmed endometriosis, NEA treatment resulted in pain relief in 94% of the women.3 Breakthrough bleeding was a common side effect, reported by 58% of participants. The investigators concluded that NEA treatment was a “cost-effective alternative with relatively mild side effects in the treatment of symptomatic endometriosis.” A conclusion which I endorse.

NEA has been reported to effectively treat ovarian endometriomas and rectovaginal endometriosis.4,5 In a cohort of 18 women who had previously had the surgical resection of an ovarian endometriosis cyst and had postoperative recurrence of pelvic pain and ovarian endometriosis, treatment was initiated with an escalating NEA regimen.4 Treatment was initiated with NEA 5 mg daily, with the dosage increased every 2 weeks by 2.5 mg until amenorrhea was established. Most women achieved amenorrhea with NEA 5 mg daily, and 89% had reduced pelvic pain. The investigators reported complete regression of the endometriosis cyst(s) in 74% of the women. In my experience, NEA does not result in complete regression of endometriosis cysts, but it does cause a reduction in cyst diameter and total volume.

In a retrospective cohort study, 61 women with pelvic pain and rectovaginal endometriosis had 5 years of treatment with NEA 2.5 mg or 5.0 mg daily.5 NEA treatment resulted in a decrease in dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, and dyschezia. The most common side effects attributed to NEA treatment were weight gain (30%), vaginal bleeding (23%), decreased libido (11%), headache (9%), bloating or swelling (8%), depression (7%), and acne (5%). In women who had sequential imaging studies, NEA treatment resulted in a decrease in rectovaginal lesion volume, stable disease volume, or an increase in lesion volume in 56%, 32%, and 12% of the women, respectively. The investigators concluded that for women with rectovaginal endometriosis, NEA treatment is a low-cost option for long-term treatment.

In my practice, I do not prescribe NEA at doses greater than 5 mg daily. There are case reports that NEA at a dose of ≥10 mg daily is associated with the development of a hepatic adenoma,6 elevated liver transaminase concentration,7 and jaundice.8 If NEA 5 mg daily is not effective in controlling pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, I stop the NEA and start a GnRH analogue, most often elagolix.

NEA 5 mg is not FDA approved as a contraceptive. However, norethindrone 0.35 mg daily, also known as the “mini-pill”, is approved as a progestin-only contraceptive.9 NEA is rapidly and completely deacetylated to norethindrone, and the disposition of oral NEA is indistinguishable from that of norethindrone.1 Since norethindrone 0.35 mg daily is approved as a contraceptive, it is highly likely that NEA 5 mg has contraceptive properties if taken daily.

Continue to: Elagolix...

Elagolix

Elagolix is FDA approved for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. I reviewed the key studies resulting in FDA approval in the November 2018 issue of

In the Elaris Endometriosis-I study, 872 women with endometriosis and pelvic pain were randomly assigned to treatment with 1 of 2 doses of elagolix (high-dose [200 mg twice daily] and low-dose [150 mg once daily]) or placebo.11 After 3 months of therapy, a clinically meaningful reduction in dysmenorrhea pain was reported by 76%, 46%, and 20% of the women in the high-dose elagolix, low-dose elagolix, and placebo groups, respectively (P<.001 for comparisons of elagolix to placebo). After 3 months of therapy, a clinically meaningful reduction in nonmenstrual pain or decreased or stable use of rescue analgesics was reported by 55%, 50%, and 37% of the women in the high-dose elagolix, low-dose elagolix, and placebo groups, respectively (P<.01 low-dose elagolix vs placebo and P<.001 high-dose elagolix vs placebo).

Hot flashes that were severe enough to be reported as an adverse event by the study participants were reported by 42%, 24%, and 7% of the women in the high-dose elagolix, low-dose elagolix, and placebo groups. Bone density was measured at baseline and after 6 months of treatment. Lumbar bone density changes were -2.61%, -0.32%, and +0.47% and hip femoral neck bone density changes were -1.89%, -0.39%, and +0.02% in the high-dose elagolix, low-dose elagolix, and placebo groups, respectively.

Another large clinical trial of elagolix for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis, Elaris EM-II, involving 817 women, produced results very similar to those reported in Elaris EM-I. The elagolix continuation studies, Elaris EM-III and -IV, demonstrated efficacy and safety of elagolix through 12 months of treatment.12

In my 2018 review,10 I noted that elagolix dose adjustment can be utilized to attempt to achieve maximal pain relief with minimal vasomotor symptoms. Elagolix at 200 mg twice daily produces a mean estradiol concentration of 12 pg/mL, whereas elagolix at 150 mg daily resulted in a mean estradiol concentration of 41 pg/mL.13 The estrogen threshold hypothesis posits that in women with endometriosis a stable estradiol concentration of 20 to 30 pg/mL is often associated with decreased pain and fewer vasomotor events.14 To achieve the target estradiol range of 20 to 30 pg/mL, I often initiate elagolix treatment with 200 mg twice daily. This enables a rapid onset of amenorrhea and a reduction in pelvic pain. Once amenorrhea has been achieved and a decrease in pelvic pain has occurred, I adjust the dose downward to 200 mg twice daily on even calendar days of each month and 200 mg once daily on odd calendar days each month. Some women will have continued pain relief and amenorrhea when the dose is further decreased to 200 mg once daily. If bothersome bleeding recurs and/or pain symptoms increase in severity, the dose can be increased to 200 mg twice daily or an alternating regimen of 200 mg twice daily and 200 mg once daily, every 2 days. An alternative to dose adjustment is to combine elagolix with NEA, which can reduce the severity of hot flashes and reduce bone loss caused by hypoestrogenism.15,16

Health insurers and pharmacy benefits managers may require a prior authorization before approving and dispensing elagolix. The prior authorization process can be burdensome for clinicians, consuming limited healthcare resources, contributing to burnout and frustrating patients.17 Elagolix is less expensive than depot-leuprolide acetate and nafarelin nasal spray and somewhat more expensive than a goserelin implant.18,19

Elagolix is not approved as a contraceptive. In the Elaris EM-I and -II trials women were advised to use 2 forms of contraception, although pregnancies did occur. There were 6 pregnancies among 475 women taking elagolix 150 mg daily and 2 pregnancies among 477 women taking elagolix 200 mg twice daily.20 Women taking elagolix should be advised to use a contraceptive, but not an estrogen-progestin contraceptive.

Continue to: Do not use opioids to treat chronic pelvic pain caused by endometriosis...

Do not use opioids to treat chronic pelvic pain caused by endometriosis

One of the greatest public health tragedies of our era is the opioid misuse epidemic. Hundreds of thousands of deaths have been caused by opioid misuse. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that for the 12-month period ending in May 2020, there were 81,000 opioid-related deaths, the greatest number ever reported in a 12-month period.21 Many authorities believe that in the United States opioid medications have been over-prescribed, contributing to the opioid misuse epidemic. There is little evidence that chronic pelvic pain is optimally managed by chronic treatment with an opioid.22,23 Prescribing opioids to vulnerable individuals to treat chronic pelvic pain may result in opioid dependency and adversely affect the patient’s health. It is best to pledge not to prescribe an opioid medication for a woman with chronic pelvic pain caused by endometriosis. In situations when pelvic pain is difficult to control with hormonal therapy and nonopioid pain medications, referral to a specialty pain practice may be warranted.

Post–conservative surgery hormone treatment reduces pelvic pain recurrence

In a meta-analysis of 14 studies that reported on endometriosis recurrence rates following conservative surgery, recurrence (defined as recurrent pelvic pain or an imaging study showing recurrent endometriosis) was significantly reduced with the use of hormone treatment compared with expectant management or placebo treatment.24 The postoperative relative risk of endometriosis recurrence was reduced by 83% with progestin treatment, 64% with estrogen-progestin contraceptive treatment, and 38% with GnRH analogue treatment. Overall, the number of patients that needed to be treated to prevent one endometriosis recurrence was 10, assuming a recurrence rate of 25% in the placebo treatment or expectant management groups.

For women with pelvic pain caused by endometriosis who develop a recurrence of pelvic pain while on postoperative hormone treatment, it is important for the prescribing clinician to be flexible and consider changing the hormone regimen. For example, if a postoperative patient is treated with a continuous estrogen-progestin contraceptive and develops recurrent pain, I will stop the contraceptive and initiate treatment with either NEA or elagolix.

Capitalize on opportunities to improve the medical care of women with endometriosis