User login

Etonogestrel implants may be bent, fractured by trauma or during sports

In 2017, Global Pediatric Health published a case report series associated with the use of long-acting reversible contraceptives, specifically the etonogestrel implant.

In November 2020, the makers of the etonogestrel implant (Merck) recommended a change in practice with the release of a notice to health care providers certified in the training of this product. This mass marketing blast included an updated warning and cautions for prescribers as well as patient information on the potential risks of migration, fracture, and bent devices attributable to trauma or sports. “Broken or Bent Implant (Section 5.16). The addition of the following underlined language: “There have been reports of broken or bent implants, which may be related to external forces (e.g., manipulation of the implant or contact sports) while in the patient’s arm. There have also been reports of migration of a broken implant fragment within the arm.”

Clearly the etonogestrel subdermal hormonal implant is an effective form of contraception and particularly beneficial in nonadherent sexually active teens who struggle to remember oral contraceptives. But it is important to be aware of this alert. Little is known about the type of trauma or rate of external force required to cause migration, fracture, or bend implants. This update requires adequate counseling of potential risks and complications of the etonogestrel implant, including the risk of migration, fracture, or bent devices specifically in the event of contact sports and trauma.

Ms. Thew is medical director of the department of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin in Milwaukee. She is a member of the Pediatric News editorial advisory board. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Ms. Thew at [email protected].

In 2017, Global Pediatric Health published a case report series associated with the use of long-acting reversible contraceptives, specifically the etonogestrel implant.

In November 2020, the makers of the etonogestrel implant (Merck) recommended a change in practice with the release of a notice to health care providers certified in the training of this product. This mass marketing blast included an updated warning and cautions for prescribers as well as patient information on the potential risks of migration, fracture, and bent devices attributable to trauma or sports. “Broken or Bent Implant (Section 5.16). The addition of the following underlined language: “There have been reports of broken or bent implants, which may be related to external forces (e.g., manipulation of the implant or contact sports) while in the patient’s arm. There have also been reports of migration of a broken implant fragment within the arm.”

Clearly the etonogestrel subdermal hormonal implant is an effective form of contraception and particularly beneficial in nonadherent sexually active teens who struggle to remember oral contraceptives. But it is important to be aware of this alert. Little is known about the type of trauma or rate of external force required to cause migration, fracture, or bend implants. This update requires adequate counseling of potential risks and complications of the etonogestrel implant, including the risk of migration, fracture, or bent devices specifically in the event of contact sports and trauma.

Ms. Thew is medical director of the department of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin in Milwaukee. She is a member of the Pediatric News editorial advisory board. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Ms. Thew at [email protected].

In 2017, Global Pediatric Health published a case report series associated with the use of long-acting reversible contraceptives, specifically the etonogestrel implant.

In November 2020, the makers of the etonogestrel implant (Merck) recommended a change in practice with the release of a notice to health care providers certified in the training of this product. This mass marketing blast included an updated warning and cautions for prescribers as well as patient information on the potential risks of migration, fracture, and bent devices attributable to trauma or sports. “Broken or Bent Implant (Section 5.16). The addition of the following underlined language: “There have been reports of broken or bent implants, which may be related to external forces (e.g., manipulation of the implant or contact sports) while in the patient’s arm. There have also been reports of migration of a broken implant fragment within the arm.”

Clearly the etonogestrel subdermal hormonal implant is an effective form of contraception and particularly beneficial in nonadherent sexually active teens who struggle to remember oral contraceptives. But it is important to be aware of this alert. Little is known about the type of trauma or rate of external force required to cause migration, fracture, or bend implants. This update requires adequate counseling of potential risks and complications of the etonogestrel implant, including the risk of migration, fracture, or bent devices specifically in the event of contact sports and trauma.

Ms. Thew is medical director of the department of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin in Milwaukee. She is a member of the Pediatric News editorial advisory board. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Ms. Thew at [email protected].

The pill toolbox: How to choose a combined oral contraceptive

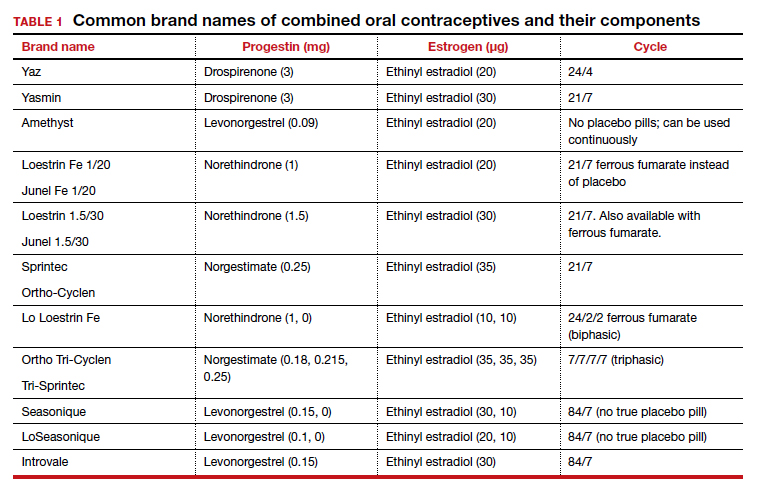

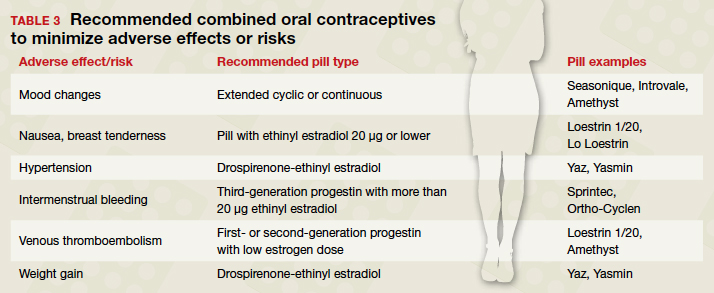

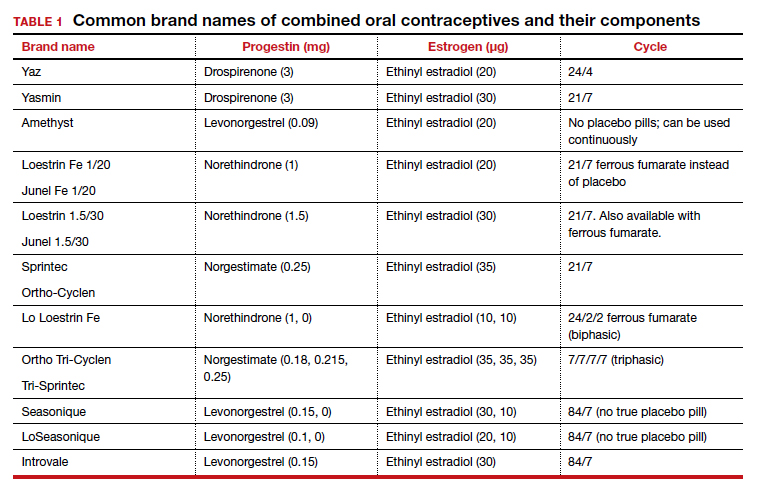

In the era of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), the pill can seem obsolete. However, it is still the second most commonly used birth control method in the United States, chosen by 19% of female contraceptive users as of 2015–2017.1 It also has noncontraceptive benefits, so it is important that obstetrician-gynecologists are well-versed in its uses. In this article, I will focus on combined oral contraceptives (COCs; TABLE 1), reviewing the major risks, benefits, and adverse effects of COCs before focusing on recommendations for particular formulations of COCs for various patient populations.

Benefits and risks

There are numerous noncontraceptive benefits of COCs, including menstrual cycle regulation; reduced risk of ovarian, endometrial, and colorectal cancer; and treatment of menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, acne, menstrual migraine, premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder, pelvic pain due to endometriosis, and hirsutism.

Common patient concerns

In terms of adverse effects, there are more potential unwanted effects of concern to women than there are ones validated in the literature. Accepted adverse effects include nausea, breast tenderness, and decreased libido. However, one of the most common concerns voiced during contraceptive counseling is that COCs will cause weight gain. A 2014 Cochrane review identified 49 trials studying the weight gain question.2 Of those, only 4 had a placebo or nonintervention group. Of these 4, there was no significant difference in weight change between the COC-receiving group and the control group. When patients bring up their concerns, it may help to remind them that women tend to gain weight over time whether or not they are taking a COC.

Another common concern is that COCs cause mood changes. A 2016 review by Schaffir and colleagues sheds some light on this topic,3 albeit limited by the paucity of prospective studies. This review identified only 1 randomized controlled trial comparing depression incidence among women initiating a COC versus a placebo. There was no difference in the incidence of depression among the groups at 3 months. Among 4 large retrospective studies of women using COCs, the agents either had no or a beneficial effect on mood. Schaffir’s review reports that there may be greater mood adverse effects with COCs among women with underlying mood disorders.

Patients may worry that COC use will permanently impair their fertility or delay return to fertility after discontinuation. Research does indicate that return of fertility after stopping COCs often takes several months (compared with immediate fertility after discontinuing a barrier method). However, there still seem to be comparable conception rates within 12 months after discontinuing COCs as there are after discontinuing other common nonhormonal or hormonal contraceptive methods. Fertility is not impacted by the duration of COC use. In addition, return to fertility seems to be comparable after discontinuation of extended cycle or continuous COCs compared with traditional-cycle COCs.4

COC safety

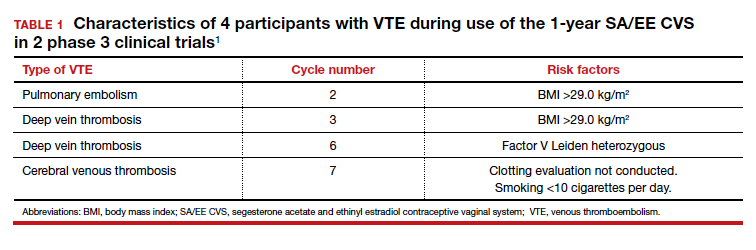

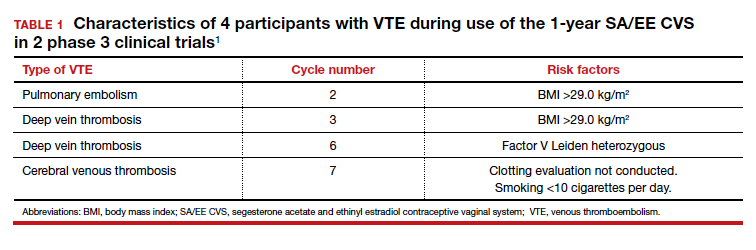

Known major risks of COCs include venous thromboembolism (VTE). The risk of VTE is about double among COC users than among nonpregnant nonusers: 3–9 per 10,000 woman-years compared with 1–5.5 In a study by the US Food and Drug Administration, drospirenone-containing COCs had double the risk of VTE than other COCs. However, the position of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists on this increased risk of VTE with drospirenone-containing pills is that it is “possible” and “minimal.”5 It is important to remember that an alternative to COC use is pregnancy, in which the VTE risk is about double that among COC users, at 5–20 per 10,000 woman-years. This risk increases further in the postpartum period, to 40–65 per 10,000 woman-years.5

Another known major risk of COCs is arterial embolic disease, including cerebrovascular accidents and myocardial infarctions. Women at increased risk for these complications include those with hypertension, diabetes, and/or obesity and women who are aged 35 or older and smoke. Interestingly, women with migraines with aura are at increased risk for stroke but not for myocardial infarction. These women increase their risk of stroke 2- to 4-fold if they use COCs.

Continue to: Different pills for different problems...

Different pills for different problems

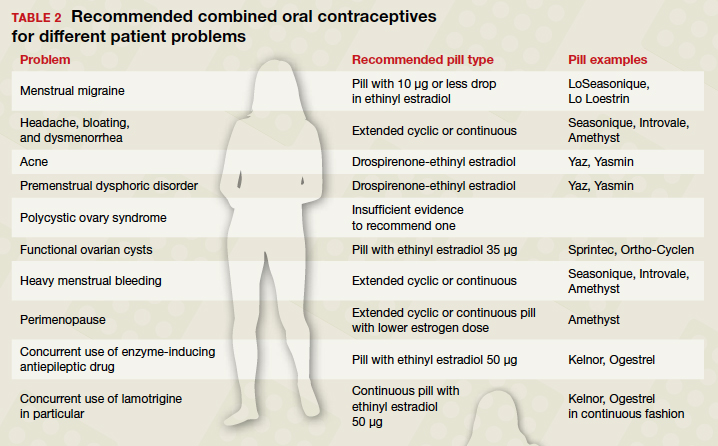

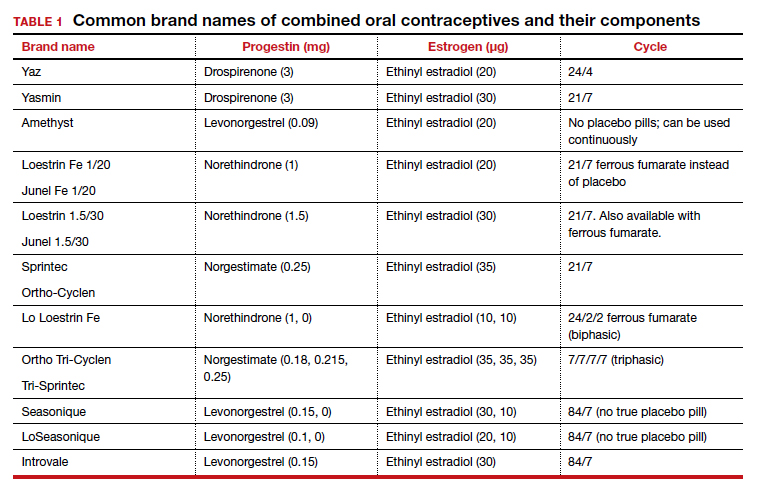

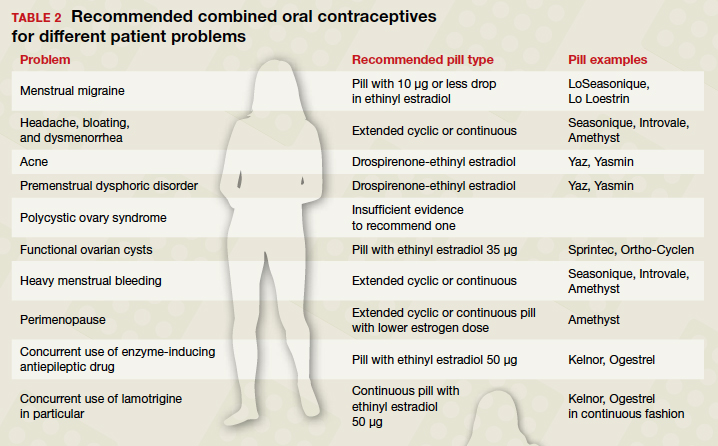

With so many pills on the market, it is important for clinicians to know how to choose a particular pill for a particular patient. The following discussion assumes that the patient in question desires a COC for contraception, then offers guidance on how to choose a pill with patient-specific noncontraceptive benefits (TABLE 2).

When HMB is a concern. Patients with heavy menstrual bleeding may experience fewer bleeding and/or spotting days with extended cyclic or continuous use of a COC rather than with traditional cyclic use.6 Examples of such COC options include:

- Introvale and Seasonique, both extended-cycle formulations

- Amethyst, which is formulated without placebo pills so that it can be used continuously

- any other COC prescribed with instructions for the patient to skip placebo pills.

An extrapolated benefit to extended-cycle or continuous COCs use for heavy menstrual bleeding is addressing anemia.

For premenstrual dysphoric disorder, the only randomized controlled trials showing improvement involve drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol pills (Yaz and Yasmin).7 There is also evidence that extended cyclic or continuous use of these formulations is more impactful for premenstrual dysphoric disorder than a traditional cycle.8

Keeping migraine avoidance and prevention in mind. Various studies have looked at the impact of different COC formulations on menstrual-related symptoms. There is evidence of greater improvement in headache, bloating, and dysmenorrhea with extended cyclic or continuous use compared with traditional cyclic use.6

In terms of headache, let us delve into menstrual migraine in particular. Menstrual migraines occur sometime between 2 days prior to 2 days after the first day of menses and are linked to a sharp drop in estrogen levels. COCs are contraindicated in women with menstrual migraines with aura because of the increased stroke risk. For women with menstrual migraines without aura, COCs can prevent migraines. Prevention depends on minimizing fluctuations in estrogen levels; any change in estrogen level greater than 10 µg of ethinyl estradiol may trigger an estrogen-related migraine. All currently available regimens of COCs that comprise 21 days of active pills and 7 days of placebo involve a drop of more than 10 µg. Options that involve a drop of 10 µg or less include any continuous formulation, the extended formulation LoSeasonique (levonorgestrel 0.1 mg and ethinyl estradiol 20 µg for 84 days, then ethinyl estradiol 10 µg for 7 days), and Lo Loestrin (ethinyl estradiol 10 µg and norethindrone 1 mg for 24 days, then ethinyl estradiol 10 µg for 2 days, then placebo for 2 days).9

What’s best for acne-prone patients? All COCs should improve acne by increasing levels of sex hormone binding globulin. However, some comparative studies have shown drospirenone-containing COCs to be the most effective for acne. This finding makes sense in light of studies demonstrating antiandrogenic effects of drospirenone.10

Managing PCOS symptoms. It seems logical, by extension, that drospirenone-containing COCs would be particularly beneficial for treating hirsutism associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Other low‒androgenic-potential progestins, such as a third-generation progestin (norgestimate or desogestrel), might similarly be hypothesized to be advantageous. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to recommend any one COC formulation over another for the indication of PCOS.11

Ovarian cysts: Can COCs be helpful? COCs are commonly prescribed by gynecologists for patients with functional ovarian cysts. It is important to note that COCs have not been found to hasten the resolution of existing cysts, so they should not be used for this purpose.12 Studies of early COCs, which had high doses of estrogen (on the order of 50 µg), showed lower rates of cysts among users. This effect seems to be attenuated with the lower-estrogen-dose pills that are currently available, but there still appears to be benefit. Therefore, for a patient prone to cysts who desires an oral contraceptive, a COC containing estrogen 35 µg is likely to be the most beneficial of COCs currently on the market.13,14

Lower-dosage COCs in perimenopause may be beneficial. COCs can ameliorate perimenopausal symptoms including abnormal uterine bleeding and vasomotor symptoms. Clinicians are often hesitant to prescribe COCs for perimenopausal women because of increased risk of VTE, stroke, myocardial infarction, and breast cancer with increasing age. However, age alone is not a contraindication to any contraceptive method. An extended cyclic or continuous regimen COC may be the best choice for a perimenopausal woman in order to avoid vasomotor symptoms that occur during hormone-free intervals. In addition, given the increasing risk of adverse effects like VTE with estrogen dose, a lower estrogen formulation is advisable.15

Patients with epilepsy who are taking antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are a special population when it comes to COCs. Certain AEDs induce hepatic enzymes involved in the metabolism and protein binding of COCs, which can result in contraceptive failure. Strong inducers are carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, perampanel, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and primidone. Weak inducers are clobazam, eslicarbazepine, felbamate, lamotrigine, rufinamide, and topiramate. Women taking any of the above AEDs are recommended to choose a different form of contraception than a COC. However, if they are limited to COCs for some reason, a preparation containing estrogen 50 µg is recommended. It is speculated that the efficacy and adverse effects of COCs with increased hormone doses, used in combination with enzyme-inducing AEDs, should be comparable to those with standard doses when not combined with AEDs; however, this speculation is unproven.16 There are few COCs on the market with estrogen doses of 50 µg, but a couple of examples are Kelnor and Ogestrel.

Additional factors have to be considered with concurrent COC use with the AED lamotrigine since COCs increase clearance of this agent. Therefore, patients taking lamotrigine who start COCs will need an increase in lamotrigine dose. To avoid fluctuations in lamotrigine serum levels, use of a continuous COC is recommended.17

Continue to: Pill types to minimize adverse effects or risks...

Pill types to minimize adverse effects or risks

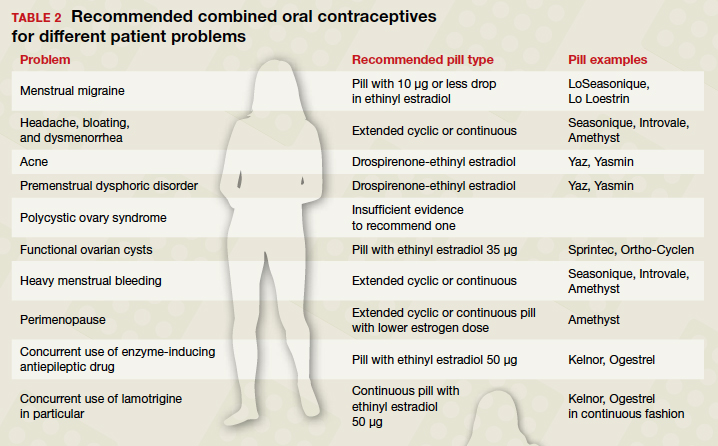

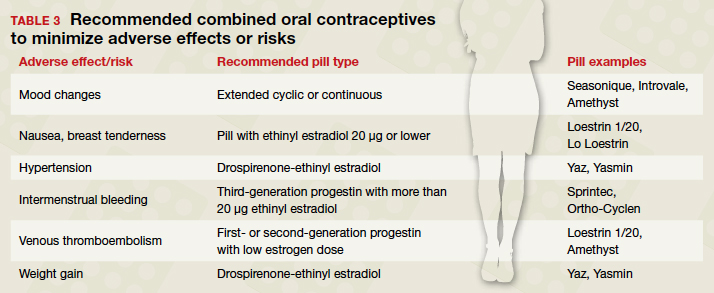

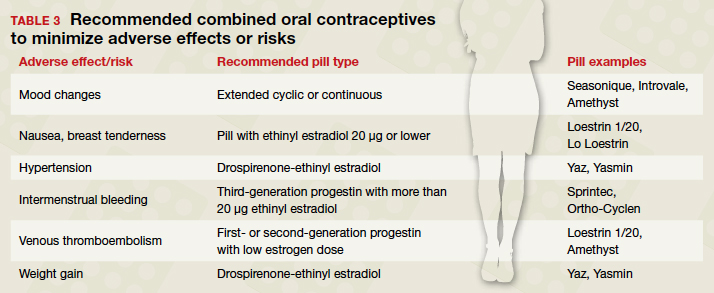

For women who desire to use a COC for contraception but who are at risk for a particular complication or are bothered by a particular adverse effect, ObGyns can optimize the choice of pill (TABLE 3). For example, women who have adverse effects of nausea and/or breast tenderness may benefit from reducing the estrogen dose to 20 µg or lower.18

Considering VTE

As discussed previously, VTE is a risk with all COCs, but some pills confer greater risk than others. For one, VTE risk increases with estrogen dose. In addition, VTE risk depends on the type of progestin. Drospirenone and third-generation progestins (norgestimate, gestodene, and desogestrel) confer a higher risk of VTE than first- or second-generation progestins. For example, a pill with estradiol 30 µg and either a third-generation progestin or drospirenone has a 50% to 80% higher risk of VTE compared with a pill with estradiol 30 µg and levonorgestrel.

For patients at particularly high risk for VTE, COCs are contraindicated. For patients for whom COCs are considered medically appropriate but who are at higher risk (eg, obese women), it is wise to use a pill containing a first-generation (norethindrone) or second-generation progestin (levonorgestrel) combined with the lowest dose of estrogen that has tolerable adverse effects.19

What about hypertension concerns?

Let us turn our attention briefly to hypertension and its relation to COC use. While the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association redefined hypertension in 2017 using a threshold of 130/80 mm Hg, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) considers hypertension to be 140/90 mm Hg in terms of safety of using COCs. ACOG states, “women with blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg may use any hormonal contraceptive method.”20 In women with hypertension in the range of 140‒159 mm Hg systolic or 90‒99 mm Hg diastolic, COCs are category 3 according to the US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, meaning that the risks usually outweigh the benefits. For women with blood pressures of 160/110 mm Hg or greater, COCs are category 4 (contraindicated). If a woman with mild hypertension is started on a COC, a drospirenone-containing pill may be the best choice because of its diuretic effects. While other contemporary COCs have been associated with a mild increase in blood pressure, drospirenone-containing pills have not shown this association.21

Continue to: At issue: Break-through bleeding, mood, and weight gain...

At issue: Break-through bleeding, mood, and weight gain

For women bothered by intermenstrual bleeding, use of a COC with a third-generation progestin may be preferable to use of one with a first- or second-generation. It may be because of decreased abnormal bleeding that COCs with third-generation progestins have lower discontinuation rates.22 In addition, COCs containing estrogen 20 µg or less are associated with more intermenstrual bleeding than those with more than 20 µg estrogen.23 Keep in mind that it is common with any COC to have intermenstrual bleeding for the first several months.

For women with pre-existing mood disorders or who report mood changes with COCs, it appears that fluctuations in hormone levels are problematic. Consistently, there is evidence that monophasic pills are preferable to multiphasic and that extended cyclic or continuous use is preferable to traditional cyclic use for mitigating mood adverse effects. There is mixed evidence on whether a low dose of ethinyl estradiol is better for mood.3

Although it is discussed above that randomized controlled trials have not shown an association between COC use and weight gain, many women remain concerned. For these women, a drospirenone-containing COC may be the best choice. Drospirenone has antimineralocorticoid activity, so it may help prevent water retention.

A brief word about multiphasic COCs. While these pills were designed to mimic physiologic hormone fluctuations and minimize hormonal adverse effects, there is insufficient evidence to compare their effects to those of monophasic pills.24 Without such evidence, there is little reason to recommend a multiphasic pill to a patient over the more straightforward monophasic formulation.

Conclusion

There are more nuances to prescribing an optimal COC for a patient than may initially come to mind. It is useful to remember that any formulation of pill may be prescribed in an extended or continuous fashion, and there are benefits for such use for premenstrual dysphoric disorder, heavy menstrual bleeding, perimenopause, and menstrual symptoms. Although there are numerous brands of COCs available, a small cadre will suffice for almost all purposes. Such a “toolbox” of pills could include a pill formatted for continuous use (Seasonique), a low estrogen pill (Loestrin), a drospirenone-containing pill (Yaz), and a pill containing a third-generation progestin and a higher dose of estrogen (Sprintec). ●

- Daniels K, Abma JC. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15-49: United States, 2015-2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 327. Hyattsville, MD; 2018.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003987.

- Schaffir J, Worly BL, Gur TL. Combined hormonal contraception and its effects on mood: a critical review. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21:347-355.

- Barnhart KT, Schreiber CA. Return to fertility following discontinuation of oral contraceptives. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:659-663.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion #540: Risk of Venous Thromboembolism Among Users of Drospirenone-Containing Oral Contraceptive Pills. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1239-1242.

- Edelman A, Micks E, Gallo MF, et al. Continuous or extended cycle vs. cyclic use of combined hormonal contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD004695.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin #110: Noncontraceptive Uses of Hormonal Contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2010:206-218.

- Coffee AL, Kuehl TJ, Willis S, et al. Oral contraceptives and premenstrual symptoms: comparison of a 21/7 and extended regimen. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1311-1319.

- Calhoun AH, Batur P. Combined hormonal contraceptives and migraine: an update on the evidence. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84:631-638.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD004425.

- McCartney CR, Marshall JC. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:54-64.

- Grimes DA, Jones LB, Lopez LM, et al. Oral contraceptives for functional ovarian cysts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD006134.

- Grimes DA, Godwin AJ, Rubin A, et al. Ovulation and follicular development associated with three low-dose oral contraceptives: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:29-34.

- Christensen JT, Boldsen JL, Westergaard JG. Functional ovarian cysts in premenopausal and gynecologically healthy women. Contraception. 2002;66:153-157.

- Hardman SM, Gebbie AE. Hormonal contraceptive regimens in the perimenopause. Maturitas. 2009;63:204-212.

- Zupanc ML. Antiepileptic drugs and hormonal contraceptives in adolescent women with epilepsy. Neurology. 2006;66 (6 suppl 3):S37-S45.

- Wegner I, Edelbroek PM, Bulk S, et al. Lamotrigine kinetics within the menstrual cycle, after menopause, and with oral contraceptives. Neurology. 2009;73:1388-1393.

- Stewart M, Black K. Choosing a combined oral contraceptive pill. Australian Prescriber. 2015;38:6-11.

- de Bastos M, Stegeman BH, Rosendaal FR, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: venous thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD010813.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin #206: use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e128-e150.

- de Morais TL, Giribela C, Nisenbaum MG, et al. Effects of a contraceptive containing drospirenone and ethinylestradiol on blood pressure, metabolic profile and neurohumoral axis in hypertensive women at reproductive age. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:113-117.

- Lawrie TA, Helmerhorst FM, Maitra NK, et al. Types of progestogens in combined oral contraception: effectiveness and side-effects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD004861.

- Gallo MF, Nanda K, Grimes DA, et al. 20 µg versus >20 µg estrogen combined oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD003989.

- van Vliet HA, Grimes DA, Lopez LM, et al. Triphasic versus monophasic oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003553

In the era of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), the pill can seem obsolete. However, it is still the second most commonly used birth control method in the United States, chosen by 19% of female contraceptive users as of 2015–2017.1 It also has noncontraceptive benefits, so it is important that obstetrician-gynecologists are well-versed in its uses. In this article, I will focus on combined oral contraceptives (COCs; TABLE 1), reviewing the major risks, benefits, and adverse effects of COCs before focusing on recommendations for particular formulations of COCs for various patient populations.

Benefits and risks

There are numerous noncontraceptive benefits of COCs, including menstrual cycle regulation; reduced risk of ovarian, endometrial, and colorectal cancer; and treatment of menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, acne, menstrual migraine, premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder, pelvic pain due to endometriosis, and hirsutism.

Common patient concerns

In terms of adverse effects, there are more potential unwanted effects of concern to women than there are ones validated in the literature. Accepted adverse effects include nausea, breast tenderness, and decreased libido. However, one of the most common concerns voiced during contraceptive counseling is that COCs will cause weight gain. A 2014 Cochrane review identified 49 trials studying the weight gain question.2 Of those, only 4 had a placebo or nonintervention group. Of these 4, there was no significant difference in weight change between the COC-receiving group and the control group. When patients bring up their concerns, it may help to remind them that women tend to gain weight over time whether or not they are taking a COC.

Another common concern is that COCs cause mood changes. A 2016 review by Schaffir and colleagues sheds some light on this topic,3 albeit limited by the paucity of prospective studies. This review identified only 1 randomized controlled trial comparing depression incidence among women initiating a COC versus a placebo. There was no difference in the incidence of depression among the groups at 3 months. Among 4 large retrospective studies of women using COCs, the agents either had no or a beneficial effect on mood. Schaffir’s review reports that there may be greater mood adverse effects with COCs among women with underlying mood disorders.

Patients may worry that COC use will permanently impair their fertility or delay return to fertility after discontinuation. Research does indicate that return of fertility after stopping COCs often takes several months (compared with immediate fertility after discontinuing a barrier method). However, there still seem to be comparable conception rates within 12 months after discontinuing COCs as there are after discontinuing other common nonhormonal or hormonal contraceptive methods. Fertility is not impacted by the duration of COC use. In addition, return to fertility seems to be comparable after discontinuation of extended cycle or continuous COCs compared with traditional-cycle COCs.4

COC safety

Known major risks of COCs include venous thromboembolism (VTE). The risk of VTE is about double among COC users than among nonpregnant nonusers: 3–9 per 10,000 woman-years compared with 1–5.5 In a study by the US Food and Drug Administration, drospirenone-containing COCs had double the risk of VTE than other COCs. However, the position of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists on this increased risk of VTE with drospirenone-containing pills is that it is “possible” and “minimal.”5 It is important to remember that an alternative to COC use is pregnancy, in which the VTE risk is about double that among COC users, at 5–20 per 10,000 woman-years. This risk increases further in the postpartum period, to 40–65 per 10,000 woman-years.5

Another known major risk of COCs is arterial embolic disease, including cerebrovascular accidents and myocardial infarctions. Women at increased risk for these complications include those with hypertension, diabetes, and/or obesity and women who are aged 35 or older and smoke. Interestingly, women with migraines with aura are at increased risk for stroke but not for myocardial infarction. These women increase their risk of stroke 2- to 4-fold if they use COCs.

Continue to: Different pills for different problems...

Different pills for different problems

With so many pills on the market, it is important for clinicians to know how to choose a particular pill for a particular patient. The following discussion assumes that the patient in question desires a COC for contraception, then offers guidance on how to choose a pill with patient-specific noncontraceptive benefits (TABLE 2).

When HMB is a concern. Patients with heavy menstrual bleeding may experience fewer bleeding and/or spotting days with extended cyclic or continuous use of a COC rather than with traditional cyclic use.6 Examples of such COC options include:

- Introvale and Seasonique, both extended-cycle formulations

- Amethyst, which is formulated without placebo pills so that it can be used continuously

- any other COC prescribed with instructions for the patient to skip placebo pills.

An extrapolated benefit to extended-cycle or continuous COCs use for heavy menstrual bleeding is addressing anemia.

For premenstrual dysphoric disorder, the only randomized controlled trials showing improvement involve drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol pills (Yaz and Yasmin).7 There is also evidence that extended cyclic or continuous use of these formulations is more impactful for premenstrual dysphoric disorder than a traditional cycle.8

Keeping migraine avoidance and prevention in mind. Various studies have looked at the impact of different COC formulations on menstrual-related symptoms. There is evidence of greater improvement in headache, bloating, and dysmenorrhea with extended cyclic or continuous use compared with traditional cyclic use.6

In terms of headache, let us delve into menstrual migraine in particular. Menstrual migraines occur sometime between 2 days prior to 2 days after the first day of menses and are linked to a sharp drop in estrogen levels. COCs are contraindicated in women with menstrual migraines with aura because of the increased stroke risk. For women with menstrual migraines without aura, COCs can prevent migraines. Prevention depends on minimizing fluctuations in estrogen levels; any change in estrogen level greater than 10 µg of ethinyl estradiol may trigger an estrogen-related migraine. All currently available regimens of COCs that comprise 21 days of active pills and 7 days of placebo involve a drop of more than 10 µg. Options that involve a drop of 10 µg or less include any continuous formulation, the extended formulation LoSeasonique (levonorgestrel 0.1 mg and ethinyl estradiol 20 µg for 84 days, then ethinyl estradiol 10 µg for 7 days), and Lo Loestrin (ethinyl estradiol 10 µg and norethindrone 1 mg for 24 days, then ethinyl estradiol 10 µg for 2 days, then placebo for 2 days).9

What’s best for acne-prone patients? All COCs should improve acne by increasing levels of sex hormone binding globulin. However, some comparative studies have shown drospirenone-containing COCs to be the most effective for acne. This finding makes sense in light of studies demonstrating antiandrogenic effects of drospirenone.10

Managing PCOS symptoms. It seems logical, by extension, that drospirenone-containing COCs would be particularly beneficial for treating hirsutism associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Other low‒androgenic-potential progestins, such as a third-generation progestin (norgestimate or desogestrel), might similarly be hypothesized to be advantageous. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to recommend any one COC formulation over another for the indication of PCOS.11

Ovarian cysts: Can COCs be helpful? COCs are commonly prescribed by gynecologists for patients with functional ovarian cysts. It is important to note that COCs have not been found to hasten the resolution of existing cysts, so they should not be used for this purpose.12 Studies of early COCs, which had high doses of estrogen (on the order of 50 µg), showed lower rates of cysts among users. This effect seems to be attenuated with the lower-estrogen-dose pills that are currently available, but there still appears to be benefit. Therefore, for a patient prone to cysts who desires an oral contraceptive, a COC containing estrogen 35 µg is likely to be the most beneficial of COCs currently on the market.13,14

Lower-dosage COCs in perimenopause may be beneficial. COCs can ameliorate perimenopausal symptoms including abnormal uterine bleeding and vasomotor symptoms. Clinicians are often hesitant to prescribe COCs for perimenopausal women because of increased risk of VTE, stroke, myocardial infarction, and breast cancer with increasing age. However, age alone is not a contraindication to any contraceptive method. An extended cyclic or continuous regimen COC may be the best choice for a perimenopausal woman in order to avoid vasomotor symptoms that occur during hormone-free intervals. In addition, given the increasing risk of adverse effects like VTE with estrogen dose, a lower estrogen formulation is advisable.15

Patients with epilepsy who are taking antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are a special population when it comes to COCs. Certain AEDs induce hepatic enzymes involved in the metabolism and protein binding of COCs, which can result in contraceptive failure. Strong inducers are carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, perampanel, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and primidone. Weak inducers are clobazam, eslicarbazepine, felbamate, lamotrigine, rufinamide, and topiramate. Women taking any of the above AEDs are recommended to choose a different form of contraception than a COC. However, if they are limited to COCs for some reason, a preparation containing estrogen 50 µg is recommended. It is speculated that the efficacy and adverse effects of COCs with increased hormone doses, used in combination with enzyme-inducing AEDs, should be comparable to those with standard doses when not combined with AEDs; however, this speculation is unproven.16 There are few COCs on the market with estrogen doses of 50 µg, but a couple of examples are Kelnor and Ogestrel.

Additional factors have to be considered with concurrent COC use with the AED lamotrigine since COCs increase clearance of this agent. Therefore, patients taking lamotrigine who start COCs will need an increase in lamotrigine dose. To avoid fluctuations in lamotrigine serum levels, use of a continuous COC is recommended.17

Continue to: Pill types to minimize adverse effects or risks...

Pill types to minimize adverse effects or risks

For women who desire to use a COC for contraception but who are at risk for a particular complication or are bothered by a particular adverse effect, ObGyns can optimize the choice of pill (TABLE 3). For example, women who have adverse effects of nausea and/or breast tenderness may benefit from reducing the estrogen dose to 20 µg or lower.18

Considering VTE

As discussed previously, VTE is a risk with all COCs, but some pills confer greater risk than others. For one, VTE risk increases with estrogen dose. In addition, VTE risk depends on the type of progestin. Drospirenone and third-generation progestins (norgestimate, gestodene, and desogestrel) confer a higher risk of VTE than first- or second-generation progestins. For example, a pill with estradiol 30 µg and either a third-generation progestin or drospirenone has a 50% to 80% higher risk of VTE compared with a pill with estradiol 30 µg and levonorgestrel.

For patients at particularly high risk for VTE, COCs are contraindicated. For patients for whom COCs are considered medically appropriate but who are at higher risk (eg, obese women), it is wise to use a pill containing a first-generation (norethindrone) or second-generation progestin (levonorgestrel) combined with the lowest dose of estrogen that has tolerable adverse effects.19

What about hypertension concerns?

Let us turn our attention briefly to hypertension and its relation to COC use. While the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association redefined hypertension in 2017 using a threshold of 130/80 mm Hg, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) considers hypertension to be 140/90 mm Hg in terms of safety of using COCs. ACOG states, “women with blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg may use any hormonal contraceptive method.”20 In women with hypertension in the range of 140‒159 mm Hg systolic or 90‒99 mm Hg diastolic, COCs are category 3 according to the US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, meaning that the risks usually outweigh the benefits. For women with blood pressures of 160/110 mm Hg or greater, COCs are category 4 (contraindicated). If a woman with mild hypertension is started on a COC, a drospirenone-containing pill may be the best choice because of its diuretic effects. While other contemporary COCs have been associated with a mild increase in blood pressure, drospirenone-containing pills have not shown this association.21

Continue to: At issue: Break-through bleeding, mood, and weight gain...

At issue: Break-through bleeding, mood, and weight gain

For women bothered by intermenstrual bleeding, use of a COC with a third-generation progestin may be preferable to use of one with a first- or second-generation. It may be because of decreased abnormal bleeding that COCs with third-generation progestins have lower discontinuation rates.22 In addition, COCs containing estrogen 20 µg or less are associated with more intermenstrual bleeding than those with more than 20 µg estrogen.23 Keep in mind that it is common with any COC to have intermenstrual bleeding for the first several months.

For women with pre-existing mood disorders or who report mood changes with COCs, it appears that fluctuations in hormone levels are problematic. Consistently, there is evidence that monophasic pills are preferable to multiphasic and that extended cyclic or continuous use is preferable to traditional cyclic use for mitigating mood adverse effects. There is mixed evidence on whether a low dose of ethinyl estradiol is better for mood.3

Although it is discussed above that randomized controlled trials have not shown an association between COC use and weight gain, many women remain concerned. For these women, a drospirenone-containing COC may be the best choice. Drospirenone has antimineralocorticoid activity, so it may help prevent water retention.

A brief word about multiphasic COCs. While these pills were designed to mimic physiologic hormone fluctuations and minimize hormonal adverse effects, there is insufficient evidence to compare their effects to those of monophasic pills.24 Without such evidence, there is little reason to recommend a multiphasic pill to a patient over the more straightforward monophasic formulation.

Conclusion

There are more nuances to prescribing an optimal COC for a patient than may initially come to mind. It is useful to remember that any formulation of pill may be prescribed in an extended or continuous fashion, and there are benefits for such use for premenstrual dysphoric disorder, heavy menstrual bleeding, perimenopause, and menstrual symptoms. Although there are numerous brands of COCs available, a small cadre will suffice for almost all purposes. Such a “toolbox” of pills could include a pill formatted for continuous use (Seasonique), a low estrogen pill (Loestrin), a drospirenone-containing pill (Yaz), and a pill containing a third-generation progestin and a higher dose of estrogen (Sprintec). ●

In the era of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), the pill can seem obsolete. However, it is still the second most commonly used birth control method in the United States, chosen by 19% of female contraceptive users as of 2015–2017.1 It also has noncontraceptive benefits, so it is important that obstetrician-gynecologists are well-versed in its uses. In this article, I will focus on combined oral contraceptives (COCs; TABLE 1), reviewing the major risks, benefits, and adverse effects of COCs before focusing on recommendations for particular formulations of COCs for various patient populations.

Benefits and risks

There are numerous noncontraceptive benefits of COCs, including menstrual cycle regulation; reduced risk of ovarian, endometrial, and colorectal cancer; and treatment of menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, acne, menstrual migraine, premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder, pelvic pain due to endometriosis, and hirsutism.

Common patient concerns

In terms of adverse effects, there are more potential unwanted effects of concern to women than there are ones validated in the literature. Accepted adverse effects include nausea, breast tenderness, and decreased libido. However, one of the most common concerns voiced during contraceptive counseling is that COCs will cause weight gain. A 2014 Cochrane review identified 49 trials studying the weight gain question.2 Of those, only 4 had a placebo or nonintervention group. Of these 4, there was no significant difference in weight change between the COC-receiving group and the control group. When patients bring up their concerns, it may help to remind them that women tend to gain weight over time whether or not they are taking a COC.

Another common concern is that COCs cause mood changes. A 2016 review by Schaffir and colleagues sheds some light on this topic,3 albeit limited by the paucity of prospective studies. This review identified only 1 randomized controlled trial comparing depression incidence among women initiating a COC versus a placebo. There was no difference in the incidence of depression among the groups at 3 months. Among 4 large retrospective studies of women using COCs, the agents either had no or a beneficial effect on mood. Schaffir’s review reports that there may be greater mood adverse effects with COCs among women with underlying mood disorders.

Patients may worry that COC use will permanently impair their fertility or delay return to fertility after discontinuation. Research does indicate that return of fertility after stopping COCs often takes several months (compared with immediate fertility after discontinuing a barrier method). However, there still seem to be comparable conception rates within 12 months after discontinuing COCs as there are after discontinuing other common nonhormonal or hormonal contraceptive methods. Fertility is not impacted by the duration of COC use. In addition, return to fertility seems to be comparable after discontinuation of extended cycle or continuous COCs compared with traditional-cycle COCs.4

COC safety

Known major risks of COCs include venous thromboembolism (VTE). The risk of VTE is about double among COC users than among nonpregnant nonusers: 3–9 per 10,000 woman-years compared with 1–5.5 In a study by the US Food and Drug Administration, drospirenone-containing COCs had double the risk of VTE than other COCs. However, the position of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists on this increased risk of VTE with drospirenone-containing pills is that it is “possible” and “minimal.”5 It is important to remember that an alternative to COC use is pregnancy, in which the VTE risk is about double that among COC users, at 5–20 per 10,000 woman-years. This risk increases further in the postpartum period, to 40–65 per 10,000 woman-years.5

Another known major risk of COCs is arterial embolic disease, including cerebrovascular accidents and myocardial infarctions. Women at increased risk for these complications include those with hypertension, diabetes, and/or obesity and women who are aged 35 or older and smoke. Interestingly, women with migraines with aura are at increased risk for stroke but not for myocardial infarction. These women increase their risk of stroke 2- to 4-fold if they use COCs.

Continue to: Different pills for different problems...

Different pills for different problems

With so many pills on the market, it is important for clinicians to know how to choose a particular pill for a particular patient. The following discussion assumes that the patient in question desires a COC for contraception, then offers guidance on how to choose a pill with patient-specific noncontraceptive benefits (TABLE 2).

When HMB is a concern. Patients with heavy menstrual bleeding may experience fewer bleeding and/or spotting days with extended cyclic or continuous use of a COC rather than with traditional cyclic use.6 Examples of such COC options include:

- Introvale and Seasonique, both extended-cycle formulations

- Amethyst, which is formulated without placebo pills so that it can be used continuously

- any other COC prescribed with instructions for the patient to skip placebo pills.

An extrapolated benefit to extended-cycle or continuous COCs use for heavy menstrual bleeding is addressing anemia.

For premenstrual dysphoric disorder, the only randomized controlled trials showing improvement involve drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol pills (Yaz and Yasmin).7 There is also evidence that extended cyclic or continuous use of these formulations is more impactful for premenstrual dysphoric disorder than a traditional cycle.8

Keeping migraine avoidance and prevention in mind. Various studies have looked at the impact of different COC formulations on menstrual-related symptoms. There is evidence of greater improvement in headache, bloating, and dysmenorrhea with extended cyclic or continuous use compared with traditional cyclic use.6

In terms of headache, let us delve into menstrual migraine in particular. Menstrual migraines occur sometime between 2 days prior to 2 days after the first day of menses and are linked to a sharp drop in estrogen levels. COCs are contraindicated in women with menstrual migraines with aura because of the increased stroke risk. For women with menstrual migraines without aura, COCs can prevent migraines. Prevention depends on minimizing fluctuations in estrogen levels; any change in estrogen level greater than 10 µg of ethinyl estradiol may trigger an estrogen-related migraine. All currently available regimens of COCs that comprise 21 days of active pills and 7 days of placebo involve a drop of more than 10 µg. Options that involve a drop of 10 µg or less include any continuous formulation, the extended formulation LoSeasonique (levonorgestrel 0.1 mg and ethinyl estradiol 20 µg for 84 days, then ethinyl estradiol 10 µg for 7 days), and Lo Loestrin (ethinyl estradiol 10 µg and norethindrone 1 mg for 24 days, then ethinyl estradiol 10 µg for 2 days, then placebo for 2 days).9

What’s best for acne-prone patients? All COCs should improve acne by increasing levels of sex hormone binding globulin. However, some comparative studies have shown drospirenone-containing COCs to be the most effective for acne. This finding makes sense in light of studies demonstrating antiandrogenic effects of drospirenone.10

Managing PCOS symptoms. It seems logical, by extension, that drospirenone-containing COCs would be particularly beneficial for treating hirsutism associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Other low‒androgenic-potential progestins, such as a third-generation progestin (norgestimate or desogestrel), might similarly be hypothesized to be advantageous. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to recommend any one COC formulation over another for the indication of PCOS.11

Ovarian cysts: Can COCs be helpful? COCs are commonly prescribed by gynecologists for patients with functional ovarian cysts. It is important to note that COCs have not been found to hasten the resolution of existing cysts, so they should not be used for this purpose.12 Studies of early COCs, which had high doses of estrogen (on the order of 50 µg), showed lower rates of cysts among users. This effect seems to be attenuated with the lower-estrogen-dose pills that are currently available, but there still appears to be benefit. Therefore, for a patient prone to cysts who desires an oral contraceptive, a COC containing estrogen 35 µg is likely to be the most beneficial of COCs currently on the market.13,14

Lower-dosage COCs in perimenopause may be beneficial. COCs can ameliorate perimenopausal symptoms including abnormal uterine bleeding and vasomotor symptoms. Clinicians are often hesitant to prescribe COCs for perimenopausal women because of increased risk of VTE, stroke, myocardial infarction, and breast cancer with increasing age. However, age alone is not a contraindication to any contraceptive method. An extended cyclic or continuous regimen COC may be the best choice for a perimenopausal woman in order to avoid vasomotor symptoms that occur during hormone-free intervals. In addition, given the increasing risk of adverse effects like VTE with estrogen dose, a lower estrogen formulation is advisable.15

Patients with epilepsy who are taking antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are a special population when it comes to COCs. Certain AEDs induce hepatic enzymes involved in the metabolism and protein binding of COCs, which can result in contraceptive failure. Strong inducers are carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, perampanel, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and primidone. Weak inducers are clobazam, eslicarbazepine, felbamate, lamotrigine, rufinamide, and topiramate. Women taking any of the above AEDs are recommended to choose a different form of contraception than a COC. However, if they are limited to COCs for some reason, a preparation containing estrogen 50 µg is recommended. It is speculated that the efficacy and adverse effects of COCs with increased hormone doses, used in combination with enzyme-inducing AEDs, should be comparable to those with standard doses when not combined with AEDs; however, this speculation is unproven.16 There are few COCs on the market with estrogen doses of 50 µg, but a couple of examples are Kelnor and Ogestrel.

Additional factors have to be considered with concurrent COC use with the AED lamotrigine since COCs increase clearance of this agent. Therefore, patients taking lamotrigine who start COCs will need an increase in lamotrigine dose. To avoid fluctuations in lamotrigine serum levels, use of a continuous COC is recommended.17

Continue to: Pill types to minimize adverse effects or risks...

Pill types to minimize adverse effects or risks

For women who desire to use a COC for contraception but who are at risk for a particular complication or are bothered by a particular adverse effect, ObGyns can optimize the choice of pill (TABLE 3). For example, women who have adverse effects of nausea and/or breast tenderness may benefit from reducing the estrogen dose to 20 µg or lower.18

Considering VTE

As discussed previously, VTE is a risk with all COCs, but some pills confer greater risk than others. For one, VTE risk increases with estrogen dose. In addition, VTE risk depends on the type of progestin. Drospirenone and third-generation progestins (norgestimate, gestodene, and desogestrel) confer a higher risk of VTE than first- or second-generation progestins. For example, a pill with estradiol 30 µg and either a third-generation progestin or drospirenone has a 50% to 80% higher risk of VTE compared with a pill with estradiol 30 µg and levonorgestrel.

For patients at particularly high risk for VTE, COCs are contraindicated. For patients for whom COCs are considered medically appropriate but who are at higher risk (eg, obese women), it is wise to use a pill containing a first-generation (norethindrone) or second-generation progestin (levonorgestrel) combined with the lowest dose of estrogen that has tolerable adverse effects.19

What about hypertension concerns?

Let us turn our attention briefly to hypertension and its relation to COC use. While the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association redefined hypertension in 2017 using a threshold of 130/80 mm Hg, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) considers hypertension to be 140/90 mm Hg in terms of safety of using COCs. ACOG states, “women with blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg may use any hormonal contraceptive method.”20 In women with hypertension in the range of 140‒159 mm Hg systolic or 90‒99 mm Hg diastolic, COCs are category 3 according to the US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, meaning that the risks usually outweigh the benefits. For women with blood pressures of 160/110 mm Hg or greater, COCs are category 4 (contraindicated). If a woman with mild hypertension is started on a COC, a drospirenone-containing pill may be the best choice because of its diuretic effects. While other contemporary COCs have been associated with a mild increase in blood pressure, drospirenone-containing pills have not shown this association.21

Continue to: At issue: Break-through bleeding, mood, and weight gain...

At issue: Break-through bleeding, mood, and weight gain

For women bothered by intermenstrual bleeding, use of a COC with a third-generation progestin may be preferable to use of one with a first- or second-generation. It may be because of decreased abnormal bleeding that COCs with third-generation progestins have lower discontinuation rates.22 In addition, COCs containing estrogen 20 µg or less are associated with more intermenstrual bleeding than those with more than 20 µg estrogen.23 Keep in mind that it is common with any COC to have intermenstrual bleeding for the first several months.

For women with pre-existing mood disorders or who report mood changes with COCs, it appears that fluctuations in hormone levels are problematic. Consistently, there is evidence that monophasic pills are preferable to multiphasic and that extended cyclic or continuous use is preferable to traditional cyclic use for mitigating mood adverse effects. There is mixed evidence on whether a low dose of ethinyl estradiol is better for mood.3

Although it is discussed above that randomized controlled trials have not shown an association between COC use and weight gain, many women remain concerned. For these women, a drospirenone-containing COC may be the best choice. Drospirenone has antimineralocorticoid activity, so it may help prevent water retention.

A brief word about multiphasic COCs. While these pills were designed to mimic physiologic hormone fluctuations and minimize hormonal adverse effects, there is insufficient evidence to compare their effects to those of monophasic pills.24 Without such evidence, there is little reason to recommend a multiphasic pill to a patient over the more straightforward monophasic formulation.

Conclusion

There are more nuances to prescribing an optimal COC for a patient than may initially come to mind. It is useful to remember that any formulation of pill may be prescribed in an extended or continuous fashion, and there are benefits for such use for premenstrual dysphoric disorder, heavy menstrual bleeding, perimenopause, and menstrual symptoms. Although there are numerous brands of COCs available, a small cadre will suffice for almost all purposes. Such a “toolbox” of pills could include a pill formatted for continuous use (Seasonique), a low estrogen pill (Loestrin), a drospirenone-containing pill (Yaz), and a pill containing a third-generation progestin and a higher dose of estrogen (Sprintec). ●

- Daniels K, Abma JC. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15-49: United States, 2015-2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 327. Hyattsville, MD; 2018.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003987.

- Schaffir J, Worly BL, Gur TL. Combined hormonal contraception and its effects on mood: a critical review. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21:347-355.

- Barnhart KT, Schreiber CA. Return to fertility following discontinuation of oral contraceptives. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:659-663.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion #540: Risk of Venous Thromboembolism Among Users of Drospirenone-Containing Oral Contraceptive Pills. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1239-1242.

- Edelman A, Micks E, Gallo MF, et al. Continuous or extended cycle vs. cyclic use of combined hormonal contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD004695.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin #110: Noncontraceptive Uses of Hormonal Contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2010:206-218.

- Coffee AL, Kuehl TJ, Willis S, et al. Oral contraceptives and premenstrual symptoms: comparison of a 21/7 and extended regimen. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1311-1319.

- Calhoun AH, Batur P. Combined hormonal contraceptives and migraine: an update on the evidence. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84:631-638.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD004425.

- McCartney CR, Marshall JC. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:54-64.

- Grimes DA, Jones LB, Lopez LM, et al. Oral contraceptives for functional ovarian cysts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD006134.

- Grimes DA, Godwin AJ, Rubin A, et al. Ovulation and follicular development associated with three low-dose oral contraceptives: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:29-34.

- Christensen JT, Boldsen JL, Westergaard JG. Functional ovarian cysts in premenopausal and gynecologically healthy women. Contraception. 2002;66:153-157.

- Hardman SM, Gebbie AE. Hormonal contraceptive regimens in the perimenopause. Maturitas. 2009;63:204-212.

- Zupanc ML. Antiepileptic drugs and hormonal contraceptives in adolescent women with epilepsy. Neurology. 2006;66 (6 suppl 3):S37-S45.

- Wegner I, Edelbroek PM, Bulk S, et al. Lamotrigine kinetics within the menstrual cycle, after menopause, and with oral contraceptives. Neurology. 2009;73:1388-1393.

- Stewart M, Black K. Choosing a combined oral contraceptive pill. Australian Prescriber. 2015;38:6-11.

- de Bastos M, Stegeman BH, Rosendaal FR, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: venous thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD010813.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin #206: use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e128-e150.

- de Morais TL, Giribela C, Nisenbaum MG, et al. Effects of a contraceptive containing drospirenone and ethinylestradiol on blood pressure, metabolic profile and neurohumoral axis in hypertensive women at reproductive age. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:113-117.

- Lawrie TA, Helmerhorst FM, Maitra NK, et al. Types of progestogens in combined oral contraception: effectiveness and side-effects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD004861.

- Gallo MF, Nanda K, Grimes DA, et al. 20 µg versus >20 µg estrogen combined oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD003989.

- van Vliet HA, Grimes DA, Lopez LM, et al. Triphasic versus monophasic oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003553

- Daniels K, Abma JC. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15-49: United States, 2015-2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 327. Hyattsville, MD; 2018.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003987.

- Schaffir J, Worly BL, Gur TL. Combined hormonal contraception and its effects on mood: a critical review. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21:347-355.

- Barnhart KT, Schreiber CA. Return to fertility following discontinuation of oral contraceptives. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:659-663.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion #540: Risk of Venous Thromboembolism Among Users of Drospirenone-Containing Oral Contraceptive Pills. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1239-1242.

- Edelman A, Micks E, Gallo MF, et al. Continuous or extended cycle vs. cyclic use of combined hormonal contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD004695.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin #110: Noncontraceptive Uses of Hormonal Contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2010:206-218.

- Coffee AL, Kuehl TJ, Willis S, et al. Oral contraceptives and premenstrual symptoms: comparison of a 21/7 and extended regimen. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1311-1319.

- Calhoun AH, Batur P. Combined hormonal contraceptives and migraine: an update on the evidence. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84:631-638.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD004425.

- McCartney CR, Marshall JC. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:54-64.

- Grimes DA, Jones LB, Lopez LM, et al. Oral contraceptives for functional ovarian cysts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD006134.

- Grimes DA, Godwin AJ, Rubin A, et al. Ovulation and follicular development associated with three low-dose oral contraceptives: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:29-34.

- Christensen JT, Boldsen JL, Westergaard JG. Functional ovarian cysts in premenopausal and gynecologically healthy women. Contraception. 2002;66:153-157.

- Hardman SM, Gebbie AE. Hormonal contraceptive regimens in the perimenopause. Maturitas. 2009;63:204-212.

- Zupanc ML. Antiepileptic drugs and hormonal contraceptives in adolescent women with epilepsy. Neurology. 2006;66 (6 suppl 3):S37-S45.

- Wegner I, Edelbroek PM, Bulk S, et al. Lamotrigine kinetics within the menstrual cycle, after menopause, and with oral contraceptives. Neurology. 2009;73:1388-1393.

- Stewart M, Black K. Choosing a combined oral contraceptive pill. Australian Prescriber. 2015;38:6-11.

- de Bastos M, Stegeman BH, Rosendaal FR, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: venous thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD010813.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin #206: use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e128-e150.

- de Morais TL, Giribela C, Nisenbaum MG, et al. Effects of a contraceptive containing drospirenone and ethinylestradiol on blood pressure, metabolic profile and neurohumoral axis in hypertensive women at reproductive age. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:113-117.

- Lawrie TA, Helmerhorst FM, Maitra NK, et al. Types of progestogens in combined oral contraception: effectiveness and side-effects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD004861.

- Gallo MF, Nanda K, Grimes DA, et al. 20 µg versus >20 µg estrogen combined oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD003989.

- van Vliet HA, Grimes DA, Lopez LM, et al. Triphasic versus monophasic oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003553

COVID-19 impacts women’s contraception choices

The rate of unintended pregnancies in the United States has decreased to approximately 45%, based on data published in 2016, and “for the first time in many years, this decrease affected women of all race/ethnicity, income levels, and education levels,” Eve Espey, MD, said at the 2020 virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Changes in contraceptive choices drove much of this decrease, said Dr. Espey, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

“What is really striking is the very large increase in use of the IUD,” she noted. However, the increased use of IUDs has raised concerns about coercive tactics being used to push for IUD use in communities of color.

“The focus we should have is on reproductive autonomy and not on unintended pregnancy, a metric that is classist and racist and may value the reproduction of some groups over others,” Dr. Espey said. Previous studies have suggested that providers are biased in how they promote long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), and reports from patients suggest that women and people of color particularly may feel marginalized, not heard, and coerced, she noted.

Help patients feel empowered

Overall, the goal of contraception should be to empower women and people to make the reproductive decisions that are best for them. “My own approach to contraceptive counseling has changed over the years; I currently start by asking if the patient wants to talk about contraception,” Dr. Espey said.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted many women’s reproductive options and plans, she said.

A survey showed that after COVID-19, more than 40% of women reported changing their plans about childbearing, 34% wanted to get pregnant later, and 33% reported trouble getting birth control or getting an appointment with a health care provider, she said.

ACOG issued a statement in March 2020 about the provision of contraception and how contraception is an essential component of comprehensive health care. The COVID-19 ACOG guidance on contraception includes use of telehealth for services including screening new patients, offering prescriptions and refills as appropriate, and managing side effects. Providers can counsel patients on the use of emergency contraception and provide advance prescriptions for ulipristal acetate, and ideally provide a year’s worth of prescription refills to reduce pharmacy visits, although not all insurance companies allow this, Dr. Espey noted.

ACOG’s COVID-19 guidance on the use of LARCs includes preserving access when possible, and focusing on postpartum contraception as a key access point.

“The postpartum period is a very convenient time for patients who want contraceptives, including LARC,” especially since they are already in the hospital setting, Dr. Espey said. However, it is important to preserve patients’ reproductive autonomy and avoid placing barriers to LARC removal for those who request it, she emphasized.

Consider MEC categories for contraception

When advising patients about contraception, Dr. Espey noted the development of a simple app with the U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) as a useful tool. The app includes the four MEC categories based on the latest evidence-based guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on contraceptive practice.

Patients in category 1 have no restriction on the use of a particular contraceptive method; category 2 means that “advantages generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks”; in category 3, these risks usually outweigh the advantages; and category 4 indicates “unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive method is used,” according to the MEC.

“What complicates category 3 is that many patients have a condition that is associated with adverse outcomes in pregnancy,” Dr. Espey noted, “So it is even more important that category 3 options only be considered if other options are not available or not acceptable to the patient,”

For example, a patient with complicated diabetes who wants depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) for contraception for a year must weigh the benefits with the theoretical risk of thromboembolic disease related to a higher dose progestin, and the fact that the injection is not reversible in the case of an adverse event. “Close follow-up is recommended for patients using contraception with category 3 recommendations,” Dr. Espey emphasized.

Some new elements of contraception that are ongoing in the pandemic health care setting include increased pharmacist prescribing of hormonal contraception, Dr. Espey said. Over-the-counter access to contraception is not yet an option, but a progestin-only pill will likely be the first, she added.

Although the Essure birth control implant is no longer available in the United States, new options for a contraceptive patch (Twirla [ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel] and Xulane [ethinyl estradiol and norelgestromin]) offer weekly contraceptive options for women with a body mass index less than 30 kg/m2.

Annovera offers more options

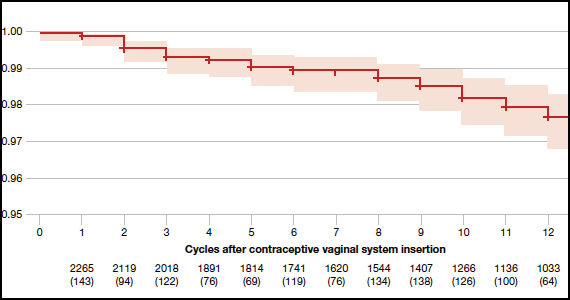

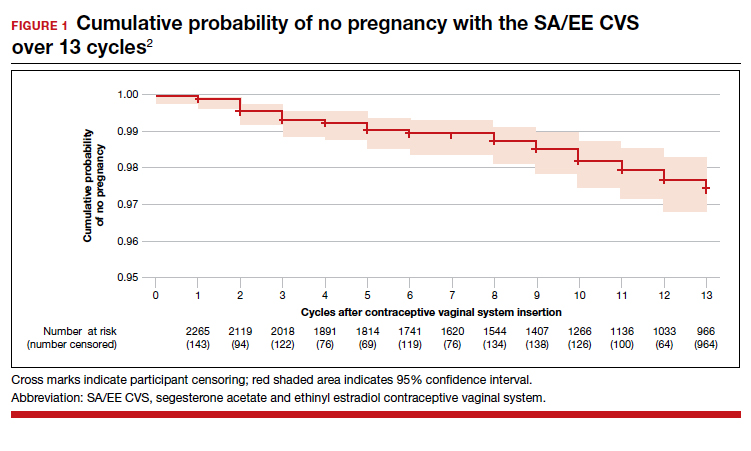

The newest choice on the market is Annovera, a flexible ring that delivers 150 mcg/day of segesterone acetate and 13 mcg/day of ethinyl estradiol. The ring is meant to remain in place for 21 days, with 7 days out, to repeat for a year.

During the question-and-answer session, Dr. Espey was asked whether it would be an off-label use to leave Annovera in continuously. Although this has not been studied, there is no biologically plausible reason not to leave it in for a year without taking it out. In either case, this is a patient-controlled LARC, she said.

Overall, “it remains to be seen how Annovera will do, as a potentially exciting, new, long-acting option” she said. “A major advantage is that it is controlled by the user,” she noted. However, “the price point will be very important as well.”

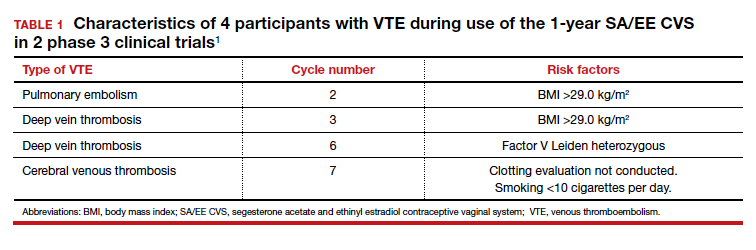

As for the off-label use by women with a BMI greater than 29 kg/m2, it is complicated. Two women with higher BMIs enrolled in clinical trials developed venous thromboembolisms, so an increased risk can’t be ruled out, although the good news is that BMI has not been shown to impact effectiveness of the product, she added.

IUDs appropriate for younger women

When asked for her guidelines about IUD options in the absence of head-to-head trials, Dr. Espey said that she often recommends either Mirena and Liletta. These levonorgestrel-releasing IUDS are essentially the same, can be used off label for 7 years (both are currently Food and Drug Administration approved for 6 years), and have a favorable bleeding profile. Other IUDs are marketed as having a smaller diameter designed for increased patient comfort with insertion, but she views this as less important than bleeding profile and duration given the length of time the device is in place.

Dr. Espey added that she doesn’t see age as a barrier to IUD use, and that the evidence does not support an increased risk of infertility. In fact, “we are seeing a higher demand among younger and nulliparous women.”

“We should respect the reproductive autonomy and the choices that our patients make,” Dr. Espey concluded.

Dr. Espey had no relevant financial disclosures. She is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

The rate of unintended pregnancies in the United States has decreased to approximately 45%, based on data published in 2016, and “for the first time in many years, this decrease affected women of all race/ethnicity, income levels, and education levels,” Eve Espey, MD, said at the 2020 virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Changes in contraceptive choices drove much of this decrease, said Dr. Espey, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

“What is really striking is the very large increase in use of the IUD,” she noted. However, the increased use of IUDs has raised concerns about coercive tactics being used to push for IUD use in communities of color.

“The focus we should have is on reproductive autonomy and not on unintended pregnancy, a metric that is classist and racist and may value the reproduction of some groups over others,” Dr. Espey said. Previous studies have suggested that providers are biased in how they promote long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), and reports from patients suggest that women and people of color particularly may feel marginalized, not heard, and coerced, she noted.

Help patients feel empowered

Overall, the goal of contraception should be to empower women and people to make the reproductive decisions that are best for them. “My own approach to contraceptive counseling has changed over the years; I currently start by asking if the patient wants to talk about contraception,” Dr. Espey said.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted many women’s reproductive options and plans, she said.

A survey showed that after COVID-19, more than 40% of women reported changing their plans about childbearing, 34% wanted to get pregnant later, and 33% reported trouble getting birth control or getting an appointment with a health care provider, she said.

ACOG issued a statement in March 2020 about the provision of contraception and how contraception is an essential component of comprehensive health care. The COVID-19 ACOG guidance on contraception includes use of telehealth for services including screening new patients, offering prescriptions and refills as appropriate, and managing side effects. Providers can counsel patients on the use of emergency contraception and provide advance prescriptions for ulipristal acetate, and ideally provide a year’s worth of prescription refills to reduce pharmacy visits, although not all insurance companies allow this, Dr. Espey noted.

ACOG’s COVID-19 guidance on the use of LARCs includes preserving access when possible, and focusing on postpartum contraception as a key access point.

“The postpartum period is a very convenient time for patients who want contraceptives, including LARC,” especially since they are already in the hospital setting, Dr. Espey said. However, it is important to preserve patients’ reproductive autonomy and avoid placing barriers to LARC removal for those who request it, she emphasized.

Consider MEC categories for contraception

When advising patients about contraception, Dr. Espey noted the development of a simple app with the U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) as a useful tool. The app includes the four MEC categories based on the latest evidence-based guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on contraceptive practice.

Patients in category 1 have no restriction on the use of a particular contraceptive method; category 2 means that “advantages generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks”; in category 3, these risks usually outweigh the advantages; and category 4 indicates “unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive method is used,” according to the MEC.

“What complicates category 3 is that many patients have a condition that is associated with adverse outcomes in pregnancy,” Dr. Espey noted, “So it is even more important that category 3 options only be considered if other options are not available or not acceptable to the patient,”

For example, a patient with complicated diabetes who wants depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) for contraception for a year must weigh the benefits with the theoretical risk of thromboembolic disease related to a higher dose progestin, and the fact that the injection is not reversible in the case of an adverse event. “Close follow-up is recommended for patients using contraception with category 3 recommendations,” Dr. Espey emphasized.

Some new elements of contraception that are ongoing in the pandemic health care setting include increased pharmacist prescribing of hormonal contraception, Dr. Espey said. Over-the-counter access to contraception is not yet an option, but a progestin-only pill will likely be the first, she added.

Although the Essure birth control implant is no longer available in the United States, new options for a contraceptive patch (Twirla [ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel] and Xulane [ethinyl estradiol and norelgestromin]) offer weekly contraceptive options for women with a body mass index less than 30 kg/m2.

Annovera offers more options

The newest choice on the market is Annovera, a flexible ring that delivers 150 mcg/day of segesterone acetate and 13 mcg/day of ethinyl estradiol. The ring is meant to remain in place for 21 days, with 7 days out, to repeat for a year.

During the question-and-answer session, Dr. Espey was asked whether it would be an off-label use to leave Annovera in continuously. Although this has not been studied, there is no biologically plausible reason not to leave it in for a year without taking it out. In either case, this is a patient-controlled LARC, she said.

Overall, “it remains to be seen how Annovera will do, as a potentially exciting, new, long-acting option” she said. “A major advantage is that it is controlled by the user,” she noted. However, “the price point will be very important as well.”

As for the off-label use by women with a BMI greater than 29 kg/m2, it is complicated. Two women with higher BMIs enrolled in clinical trials developed venous thromboembolisms, so an increased risk can’t be ruled out, although the good news is that BMI has not been shown to impact effectiveness of the product, she added.

IUDs appropriate for younger women

When asked for her guidelines about IUD options in the absence of head-to-head trials, Dr. Espey said that she often recommends either Mirena and Liletta. These levonorgestrel-releasing IUDS are essentially the same, can be used off label for 7 years (both are currently Food and Drug Administration approved for 6 years), and have a favorable bleeding profile. Other IUDs are marketed as having a smaller diameter designed for increased patient comfort with insertion, but she views this as less important than bleeding profile and duration given the length of time the device is in place.

Dr. Espey added that she doesn’t see age as a barrier to IUD use, and that the evidence does not support an increased risk of infertility. In fact, “we are seeing a higher demand among younger and nulliparous women.”

“We should respect the reproductive autonomy and the choices that our patients make,” Dr. Espey concluded.