User login

Clues to eczematous cheilitis may lie in the history

NEW YORK – , but patients may be slow to seek help, Bethanee Schlosser, MD, PhD, said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

One of the challenges in helping patients with lip problems is that lips are constantly in motion and constantly interacting with the outside world, said Dr. Schlosser, of the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago. There’s ongoing low-level trauma with phonation, eating, drinking, and general environmental exposure, she said. Eczematous cheilitis will present with scaling and erythema of the vermilion lips, with lower lip involvement often more pronounced than symptoms on the upper lip. Fissuring and erosion are sometimes, but not always, present as well.

In addition to flaking and redness, Dr. Schlosser noted that patients will complain of dry lips, irritation, itching, and sometimes tingling.

Sorting out the etiology of eczematous cheilitis requires a thorough history. “Ask about habits, such as lip licking, picking, or biting,” she said. Recent dental work, braces, or other appliances for alignment or temporomandibular joint problems can introduce both mechanical irritation and potential allergens, and even musical instruments can be culprits, such as when an oboe reed causes an allergic reaction.

Personal hygiene products, cosmetics, gum chewing, and candy consumption can be the irritant culprits, noted Dr. Schlosser. Careful questioning of patients and examination of the products used can provide clues, since dyes and pigments in cosmetics and gum may provoke reactions.

History taking should also include questions about tobacco in all forms, marijuana, and prescription medication, which can cause lip problems. And it’s important to ask about skin disease in general, to determine if symptoms are present in other anatomic locations, and to ask about any family history of skin disease, she said.

Endogenous contributors can include true atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and nutritional deficiencies. Psoriatic cheilitis can have prominent crusting and exfoliation. In a Brazilian study that evaluated patents with cutaneous psoriasis and age-, race-, and sex-matched controls with no history of skin disease, psoriasis was associated with geographic tongue, with an odds ratio of 5.0 (95% CI 1.5-16.8). Geographic stomatitis can also be seen, said Dr. Schlosser. Tongue fissures were also more common among those with psoriasis cheilitis (OR 2.7, 95% confidence interval, 1.3-5.6) in the same study (Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009 Aug 1;14[8]:e371-5).

For psoriatic cheilitis, looking beyond the lips can help refine the diagnosis, she noted. There may be intra-oral signs or signs of extra-oral involvement, especially on the scalp, ears, and genitalia. Koebnerization may be difficult to detect on the lips, but may be present elsewhere. A family history of psoriasis may also tip the scales toward this diagnosis.

Exogenous causes of eczematous cheilitis are much more common and can include contact with irritants and allergens, factitial cheilitis, and cheilitis medicamentosa, Dr Schlosser pointed out.

Allergic contact dermatitis can come from local exposure (to cosmetics and other personal care items, for example) or from incidental exposures. Components of saliva can become concentrated when saliva dries outside the oral cavity, so for chronic lip lickers, saliva alone can be sufficiently irritating to provoke a cheilitis, Dr. Schlosser said.

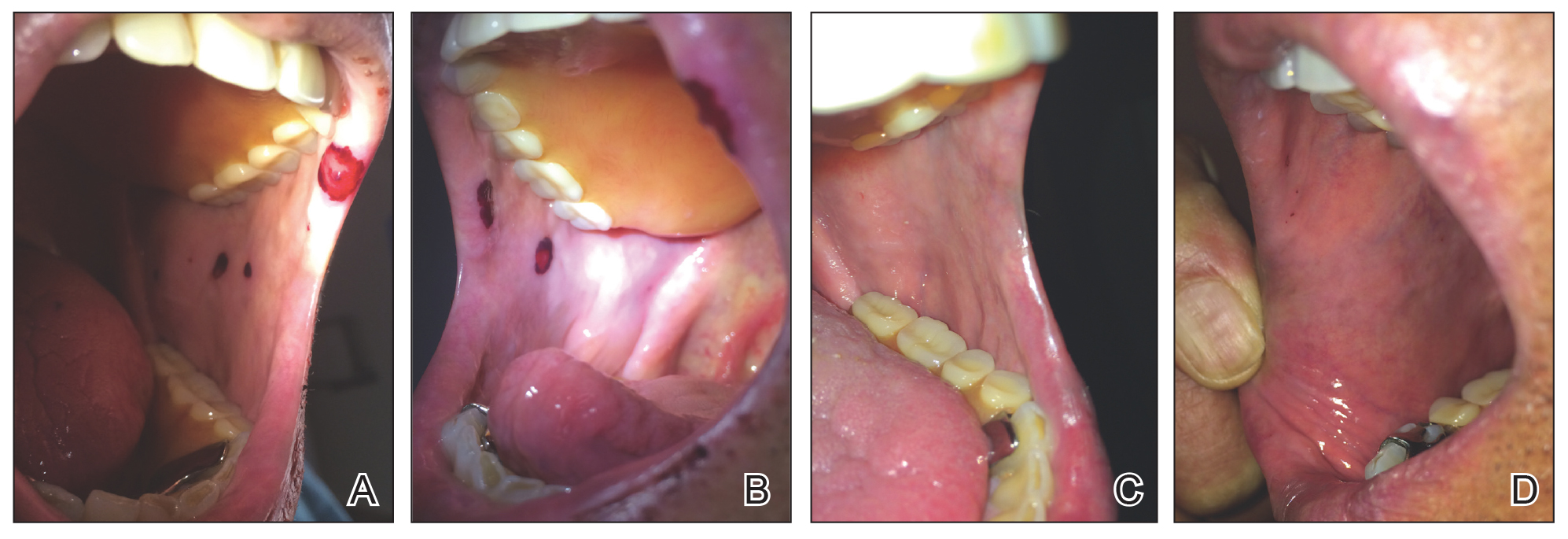

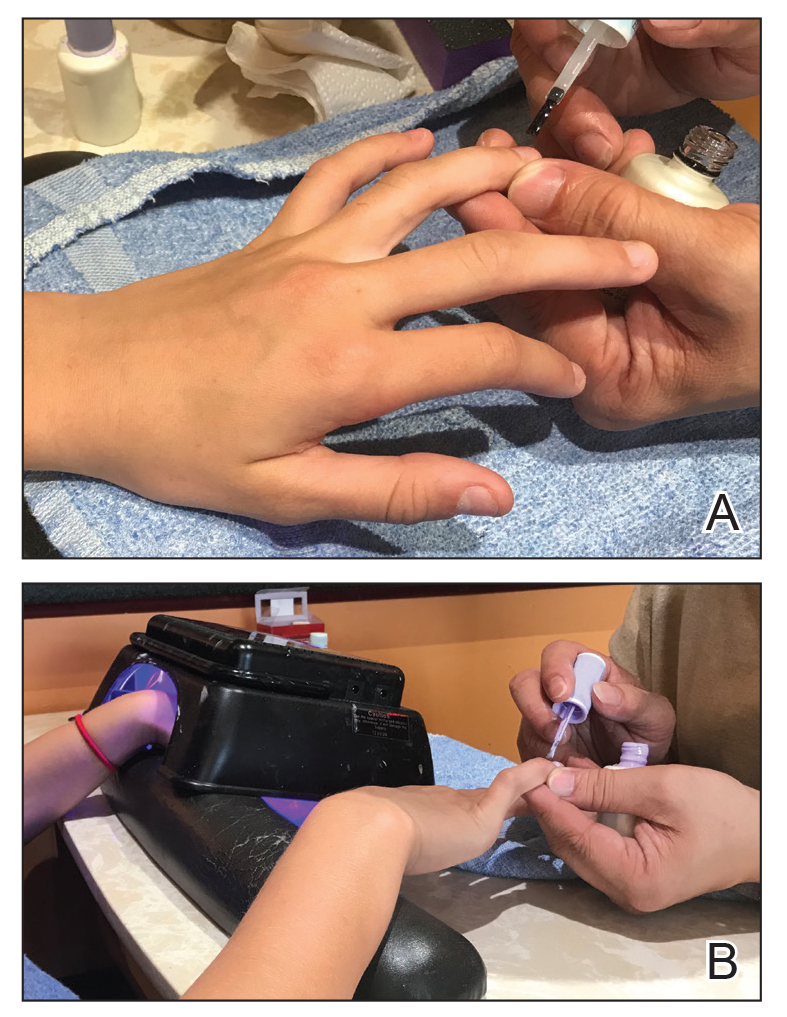

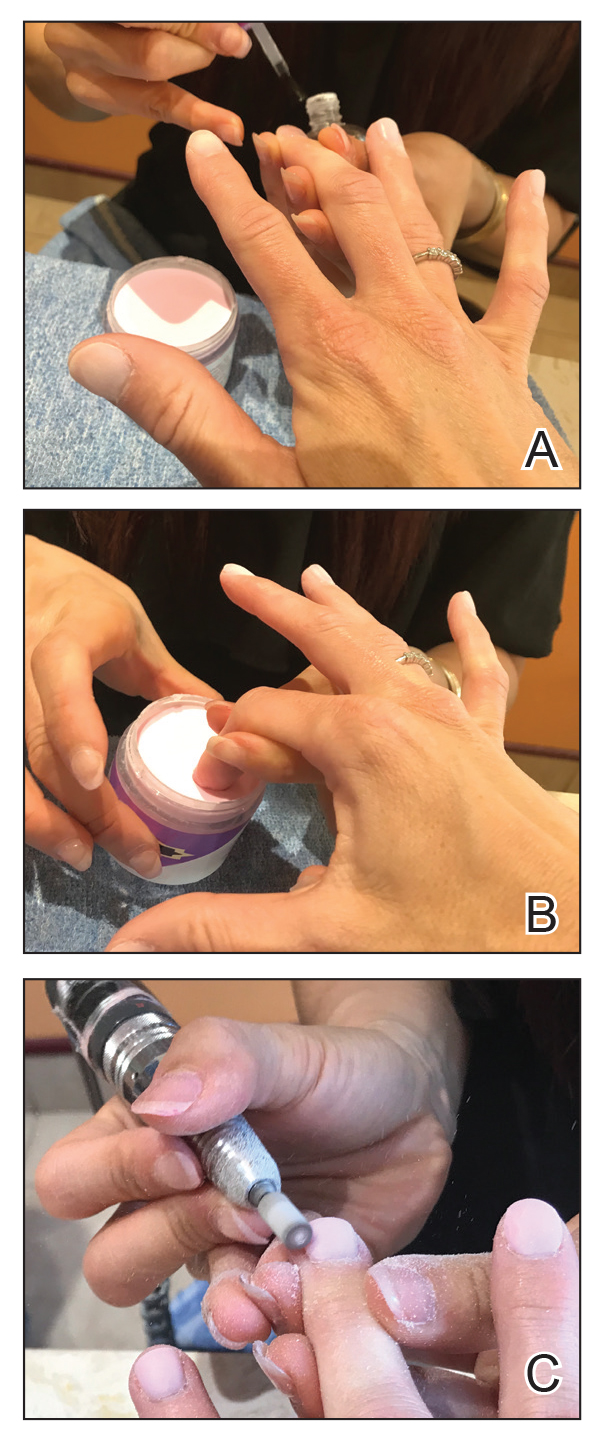

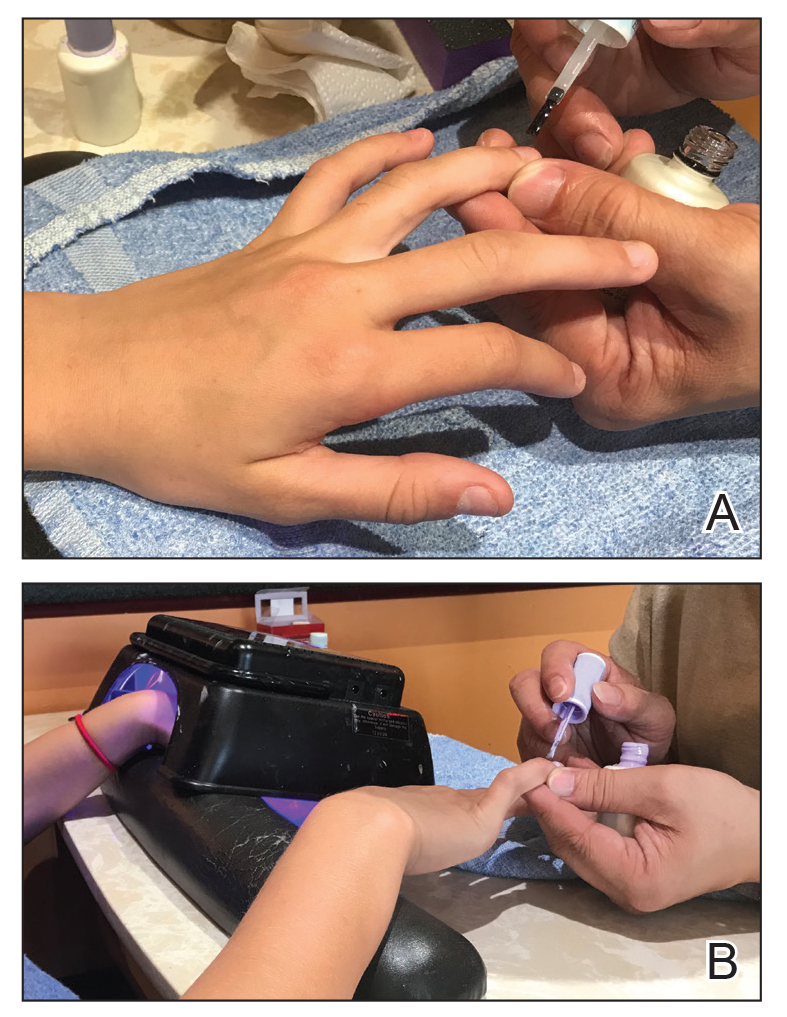

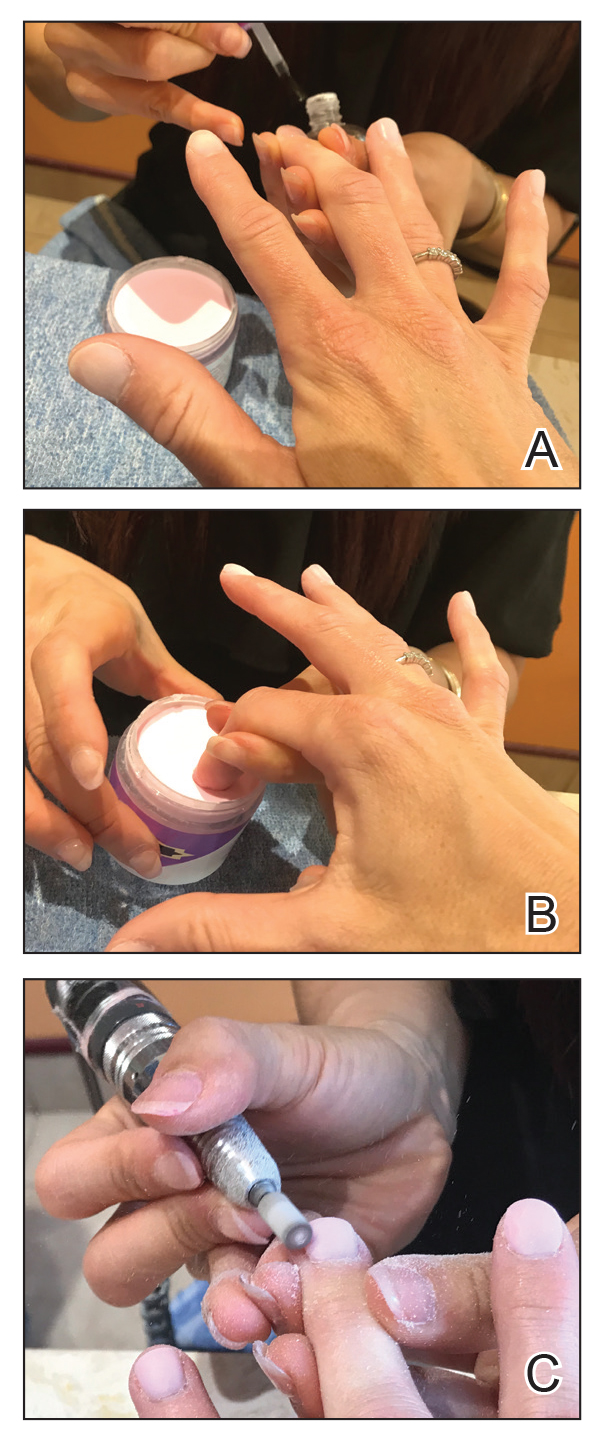

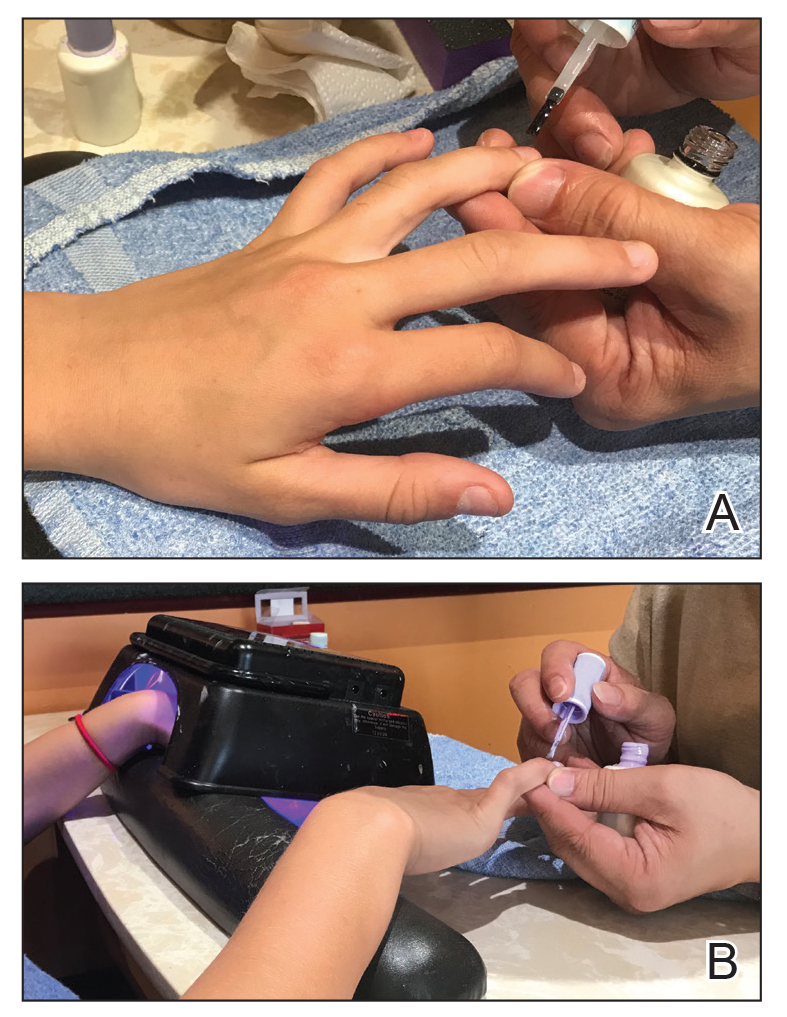

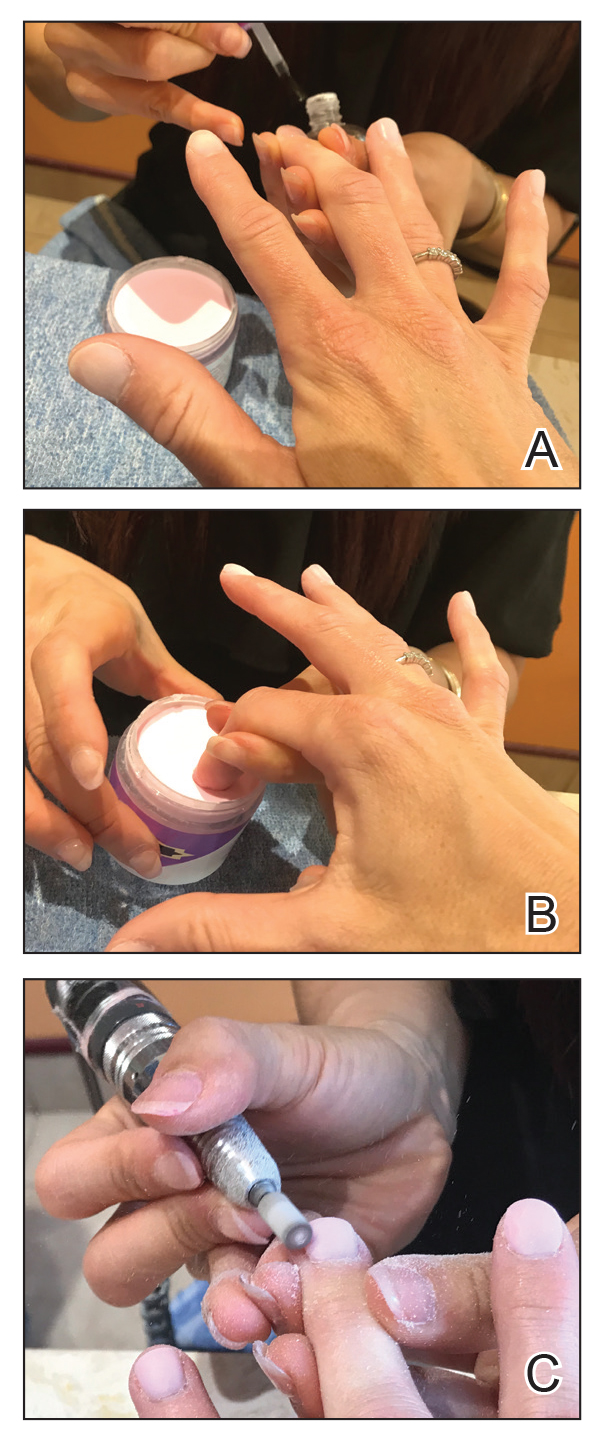

Transfer of an irritant or allergen is also possible from other body sites, as when a nail-chewer develops allergic cheilitis from an ingredient in nail polish. Transfer from products used on other facial areas and the hair is also possible, as is “connubial transfer,” when an allergen is transferred from an intimate partner.

Cutaneous patch tests can be helpful in pinpointing the offending agent, or agents, according to Dr. Schlosser. She cited a study of 91 patients (77% of whom were female) who underwent patch testing for eczematous cheilitis. The researchers determined that 45% of patients had allergic contact cheilitis (Int J Dermatol. 2016 Jul;55[7]:e386-91).

The patch testing revealed that fragrances, balsam of Peru (Myroxylon pereirae resin), preservatives, and even metals such as nickel and gold were common allergens. The findings echo those in another database review that showed fragrances, M. pereirae, and nickel as the top three allergens on patch testing for lip cheilitis.

Dr. Schlosser said that the most common offending sources are lipsticks, makeup, other cosmetic products, and moisturizer, which are responsible for 10% or more of reactions.

Whatever the etiology, the treatment of eczematous cheilitis can be divided conceptually into two phases. During the induction phase, use of a low- to mid-potency topical corticosteroid ointment quiets inflammation. Examples include alclometasone 0.05%, desonide 0.05%, fluticasone 0.005%, or triamcinolone 0.1%. “Ointment formulations are preferred,” said Dr. Schlosser, since they won’t dissolve so easily with lip licking and will adhere well to the surface of the vermilion lip.

Next, a topical calcineurin inhibitor such as tacrolimus 0.1% can be used for maintenance. Other topical medications, especially topical anesthetics, should be used with caution, she said.

For psoriatic cheilitis, induction with 5% salicylic acid ointment can be followed by the topical calcineurin inhibitor phase, said Dr. Schlosser.

Dr. Schlosser disclosed financial relationships with Beiersdorf, Decision Support in Medicine, and UpToDate.

[email protected]

NEW YORK – , but patients may be slow to seek help, Bethanee Schlosser, MD, PhD, said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

One of the challenges in helping patients with lip problems is that lips are constantly in motion and constantly interacting with the outside world, said Dr. Schlosser, of the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago. There’s ongoing low-level trauma with phonation, eating, drinking, and general environmental exposure, she said. Eczematous cheilitis will present with scaling and erythema of the vermilion lips, with lower lip involvement often more pronounced than symptoms on the upper lip. Fissuring and erosion are sometimes, but not always, present as well.

In addition to flaking and redness, Dr. Schlosser noted that patients will complain of dry lips, irritation, itching, and sometimes tingling.

Sorting out the etiology of eczematous cheilitis requires a thorough history. “Ask about habits, such as lip licking, picking, or biting,” she said. Recent dental work, braces, or other appliances for alignment or temporomandibular joint problems can introduce both mechanical irritation and potential allergens, and even musical instruments can be culprits, such as when an oboe reed causes an allergic reaction.

Personal hygiene products, cosmetics, gum chewing, and candy consumption can be the irritant culprits, noted Dr. Schlosser. Careful questioning of patients and examination of the products used can provide clues, since dyes and pigments in cosmetics and gum may provoke reactions.

History taking should also include questions about tobacco in all forms, marijuana, and prescription medication, which can cause lip problems. And it’s important to ask about skin disease in general, to determine if symptoms are present in other anatomic locations, and to ask about any family history of skin disease, she said.

Endogenous contributors can include true atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and nutritional deficiencies. Psoriatic cheilitis can have prominent crusting and exfoliation. In a Brazilian study that evaluated patents with cutaneous psoriasis and age-, race-, and sex-matched controls with no history of skin disease, psoriasis was associated with geographic tongue, with an odds ratio of 5.0 (95% CI 1.5-16.8). Geographic stomatitis can also be seen, said Dr. Schlosser. Tongue fissures were also more common among those with psoriasis cheilitis (OR 2.7, 95% confidence interval, 1.3-5.6) in the same study (Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009 Aug 1;14[8]:e371-5).

For psoriatic cheilitis, looking beyond the lips can help refine the diagnosis, she noted. There may be intra-oral signs or signs of extra-oral involvement, especially on the scalp, ears, and genitalia. Koebnerization may be difficult to detect on the lips, but may be present elsewhere. A family history of psoriasis may also tip the scales toward this diagnosis.

Exogenous causes of eczematous cheilitis are much more common and can include contact with irritants and allergens, factitial cheilitis, and cheilitis medicamentosa, Dr Schlosser pointed out.

Allergic contact dermatitis can come from local exposure (to cosmetics and other personal care items, for example) or from incidental exposures. Components of saliva can become concentrated when saliva dries outside the oral cavity, so for chronic lip lickers, saliva alone can be sufficiently irritating to provoke a cheilitis, Dr. Schlosser said.

Transfer of an irritant or allergen is also possible from other body sites, as when a nail-chewer develops allergic cheilitis from an ingredient in nail polish. Transfer from products used on other facial areas and the hair is also possible, as is “connubial transfer,” when an allergen is transferred from an intimate partner.

Cutaneous patch tests can be helpful in pinpointing the offending agent, or agents, according to Dr. Schlosser. She cited a study of 91 patients (77% of whom were female) who underwent patch testing for eczematous cheilitis. The researchers determined that 45% of patients had allergic contact cheilitis (Int J Dermatol. 2016 Jul;55[7]:e386-91).

The patch testing revealed that fragrances, balsam of Peru (Myroxylon pereirae resin), preservatives, and even metals such as nickel and gold were common allergens. The findings echo those in another database review that showed fragrances, M. pereirae, and nickel as the top three allergens on patch testing for lip cheilitis.

Dr. Schlosser said that the most common offending sources are lipsticks, makeup, other cosmetic products, and moisturizer, which are responsible for 10% or more of reactions.

Whatever the etiology, the treatment of eczematous cheilitis can be divided conceptually into two phases. During the induction phase, use of a low- to mid-potency topical corticosteroid ointment quiets inflammation. Examples include alclometasone 0.05%, desonide 0.05%, fluticasone 0.005%, or triamcinolone 0.1%. “Ointment formulations are preferred,” said Dr. Schlosser, since they won’t dissolve so easily with lip licking and will adhere well to the surface of the vermilion lip.

Next, a topical calcineurin inhibitor such as tacrolimus 0.1% can be used for maintenance. Other topical medications, especially topical anesthetics, should be used with caution, she said.

For psoriatic cheilitis, induction with 5% salicylic acid ointment can be followed by the topical calcineurin inhibitor phase, said Dr. Schlosser.

Dr. Schlosser disclosed financial relationships with Beiersdorf, Decision Support in Medicine, and UpToDate.

[email protected]

NEW YORK – , but patients may be slow to seek help, Bethanee Schlosser, MD, PhD, said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

One of the challenges in helping patients with lip problems is that lips are constantly in motion and constantly interacting with the outside world, said Dr. Schlosser, of the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago. There’s ongoing low-level trauma with phonation, eating, drinking, and general environmental exposure, she said. Eczematous cheilitis will present with scaling and erythema of the vermilion lips, with lower lip involvement often more pronounced than symptoms on the upper lip. Fissuring and erosion are sometimes, but not always, present as well.

In addition to flaking and redness, Dr. Schlosser noted that patients will complain of dry lips, irritation, itching, and sometimes tingling.

Sorting out the etiology of eczematous cheilitis requires a thorough history. “Ask about habits, such as lip licking, picking, or biting,” she said. Recent dental work, braces, or other appliances for alignment or temporomandibular joint problems can introduce both mechanical irritation and potential allergens, and even musical instruments can be culprits, such as when an oboe reed causes an allergic reaction.

Personal hygiene products, cosmetics, gum chewing, and candy consumption can be the irritant culprits, noted Dr. Schlosser. Careful questioning of patients and examination of the products used can provide clues, since dyes and pigments in cosmetics and gum may provoke reactions.

History taking should also include questions about tobacco in all forms, marijuana, and prescription medication, which can cause lip problems. And it’s important to ask about skin disease in general, to determine if symptoms are present in other anatomic locations, and to ask about any family history of skin disease, she said.

Endogenous contributors can include true atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and nutritional deficiencies. Psoriatic cheilitis can have prominent crusting and exfoliation. In a Brazilian study that evaluated patents with cutaneous psoriasis and age-, race-, and sex-matched controls with no history of skin disease, psoriasis was associated with geographic tongue, with an odds ratio of 5.0 (95% CI 1.5-16.8). Geographic stomatitis can also be seen, said Dr. Schlosser. Tongue fissures were also more common among those with psoriasis cheilitis (OR 2.7, 95% confidence interval, 1.3-5.6) in the same study (Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009 Aug 1;14[8]:e371-5).

For psoriatic cheilitis, looking beyond the lips can help refine the diagnosis, she noted. There may be intra-oral signs or signs of extra-oral involvement, especially on the scalp, ears, and genitalia. Koebnerization may be difficult to detect on the lips, but may be present elsewhere. A family history of psoriasis may also tip the scales toward this diagnosis.

Exogenous causes of eczematous cheilitis are much more common and can include contact with irritants and allergens, factitial cheilitis, and cheilitis medicamentosa, Dr Schlosser pointed out.

Allergic contact dermatitis can come from local exposure (to cosmetics and other personal care items, for example) or from incidental exposures. Components of saliva can become concentrated when saliva dries outside the oral cavity, so for chronic lip lickers, saliva alone can be sufficiently irritating to provoke a cheilitis, Dr. Schlosser said.

Transfer of an irritant or allergen is also possible from other body sites, as when a nail-chewer develops allergic cheilitis from an ingredient in nail polish. Transfer from products used on other facial areas and the hair is also possible, as is “connubial transfer,” when an allergen is transferred from an intimate partner.

Cutaneous patch tests can be helpful in pinpointing the offending agent, or agents, according to Dr. Schlosser. She cited a study of 91 patients (77% of whom were female) who underwent patch testing for eczematous cheilitis. The researchers determined that 45% of patients had allergic contact cheilitis (Int J Dermatol. 2016 Jul;55[7]:e386-91).

The patch testing revealed that fragrances, balsam of Peru (Myroxylon pereirae resin), preservatives, and even metals such as nickel and gold were common allergens. The findings echo those in another database review that showed fragrances, M. pereirae, and nickel as the top three allergens on patch testing for lip cheilitis.

Dr. Schlosser said that the most common offending sources are lipsticks, makeup, other cosmetic products, and moisturizer, which are responsible for 10% or more of reactions.

Whatever the etiology, the treatment of eczematous cheilitis can be divided conceptually into two phases. During the induction phase, use of a low- to mid-potency topical corticosteroid ointment quiets inflammation. Examples include alclometasone 0.05%, desonide 0.05%, fluticasone 0.005%, or triamcinolone 0.1%. “Ointment formulations are preferred,” said Dr. Schlosser, since they won’t dissolve so easily with lip licking and will adhere well to the surface of the vermilion lip.

Next, a topical calcineurin inhibitor such as tacrolimus 0.1% can be used for maintenance. Other topical medications, especially topical anesthetics, should be used with caution, she said.

For psoriatic cheilitis, induction with 5% salicylic acid ointment can be followed by the topical calcineurin inhibitor phase, said Dr. Schlosser.

Dr. Schlosser disclosed financial relationships with Beiersdorf, Decision Support in Medicine, and UpToDate.

[email protected]

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SUMMER AAD 2019

Expert shares contact dermatitis trends

AUSTIN – Not long ago, Rajani Katta, MD, received a text message from a friend who expressed concern about a rash that developed in the underarm of her teenage daughter.

The culprit turned out to be the lavender essential oil contained in an “all natural” deodorant that her daughter had recently switched to – a storyline that Dr. Katta encounters with increasing frequency in her role as clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Dr. Katta said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “When you talk about a natural allergy, it is more likely to occur if your skin barrier is compromised, so I think that’s why we’re seeing it, especially in young girls in the underarm area. If you shave the underarm, you impair that skin barrier and you’re more likely to develop a reaction to something you’re using over it.”

Her list of recommended deodorants includes Almay Roll-On Antiperspirant & Deodorant, Crystal Body Deodorant Stick, Crystal Roll-On Body Deodorant, Vanicream Deodorant for Sensitive Skin (aluminum-free), Vanicream Antiperspirant/Deodorant, and CertainDri Clinical Strength Roll-On. They are fragrance-free and lack propylene glycol, which is a common allergen.

Increasingly, essential oils are being added to lip balms and toothpastes, said Dr. Katta, who is also author of the 2018 book “Glow: The Dermatologist’s Guide to a Whole Foods Younger Skin Diet.” She recalled one patient who presented with chronic chapped lips. “It doesn’t matter how many lip glosses I try; it just keeps getting worse,” the patient told her. The likely culprit turned out to be ingredients contained in flavored lip balm from EOS. Reports of blistering and cracking of the lips from use of the products prompted a class action lawsuit and a notice to consumers from the Food and Drug Administration.

Another patient presented with cracked lips after switching to an “all natural” toothpaste that was labeled “gluten free.”

“It looked great,” Dr. Katta recalled. “Unfortunately it was not flavoring free. She reacted to multiple essential oils, including tea tree oil, contained in the toothpaste. This is being added to a number of toothpastes, and I think we’re going to see more of these types of reactions.”

Other toothpastes contain balsam of Peru, “which is consistently one of the top allergens in patch test clinics,” she said. “One of the components of balsam of Peru is a cinnamon compound, which can be an issue.”

Dr. Katta advises her patients to use Vaseline petroleum jelly as a lip balm and recommends Tom’s of Maine Silly Strawberry Flavor (this flavor only) toothpaste for children.

A few years ago, a teenager presented to Dr. Katta with intense bullae on the dorsum of the foot after wearing shoes without socks. “She was wearing white canvas Keds, which looked very innocuous,” she said. Patch testing revealed that the teen reacted to four different rubber accelerators. “When we contacted the company, they [acknowledged] using rubber cement to make the canvas Keds,” Dr. Katta said. “Rubber cement is an adhesive and it does contain rubber accelerators. Later, I saw two cases of children who had walked around all day at the amusement park wearing their Sperry Topsiders without any socks. We couldn’t get any information from that manufacturer, but I suspect that they also use a rubber-based glue to make those shoes.” She characterized shoes as “a real setup for a foot allergy because you have friction, sweat that’s pulling allergen out of an object, and sweat is carrying it over, especially to the dorsum of the foot.”

Dr. Katta has also noticed an uptick in the number of young patients who develop allergic reactions to dyes used to make workout clothing. “If you ever see rashes that do not involve the axillary vault but do have peraxillary accentuation, think textile allergy,” she said. “We’re seeing a lot of reactions to disperse blue clothing dyes. When you think about textile allergy from the dyes, it tends to be the blue and black clothing. It’s more likely in the setting of synthetic fabrics because they leach out dyes more easily, and it’s more likely in the setting of sweat because sweat helps pull allergen out. I’m seeing it a lot from sports uniforms and tight black leggings and tight sports bras that people are wearing. I’m also seeing some from bathing suits and swim shirts.”

Exposure to products containing the preservative methylisothiazolinone (MI) is also on the rise. It ranks as the second most frequent allergen for which the North American Contact Dermatitis Group is seeing positive results on patch testing, with rates of 13.4%. MI can be found in many skin care products and “probably about half of school glues, fabric glues, and craft glues,” Dr. Katta said. “Stick versus liquid doesn’t make a difference.” Children and teens often use craft glues, laundry detergents, and other products to create “slime” as a way to learn about viscosity, polymers, and chemical reactions. “Sometimes these children have sensitive skin, or they’re using it with prolonged contact, so they may be sensitizing themselves to the MI,” she said.

She concluded her remarks by noting that an increasing number of young patients are developing reactions to wearable medical devices such as insulin pumps and glucose monitors. “With this, the first thing to think about is frictional irritant dermatitis,” she said. “You can put Scanpor medical paper tape on people’s back for 48 hours straight to patch test them. Some people are incredibly reactive to the friction of just that tape. You also have to think about trapped allergen. One of my patients reacted to colophony, fragrance mix, and propylene glycol, all of which were contained in his skin care products. Some people are getting advice from other patients to use Mastisol liquid adhesive to help their glucose monitors stick better. Mastisol has a high rate of cross-reactivity with balsam of Peru, so it’s a fragrance allergen. That’s the first thing you want to ask patients about: what products they’re using.”

One of her patients thought she was reacting to adhesive tape on her skin, but in fact she was reacting to two different acrylates: ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) and hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA). “I know about these allergens because I see reactions from butterfly needles in dialysis patients,” Dr. Katta explained. “What happens is, these acrylates are glues or plastics used somewhere else on the device, and they can migrate through barriers.”

In one published case, a 9-year-old boy developed a reaction to ethyl cyanoacrylate contained in a glucose sensor adhesive (Dermatitis. 2017; 28[4]:289-91). It never touched the boy’s skin directly but was presumed to migrate through that tape. “The bottom line is that acrylates may induce contact dermatitis even through perceived barriers,” she said. “Their use anywhere in medical devices may prove problematic.”

Dr. Katta reported that she is a member of the advisory board for Vichy Laboratories.

AUSTIN – Not long ago, Rajani Katta, MD, received a text message from a friend who expressed concern about a rash that developed in the underarm of her teenage daughter.

The culprit turned out to be the lavender essential oil contained in an “all natural” deodorant that her daughter had recently switched to – a storyline that Dr. Katta encounters with increasing frequency in her role as clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Dr. Katta said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “When you talk about a natural allergy, it is more likely to occur if your skin barrier is compromised, so I think that’s why we’re seeing it, especially in young girls in the underarm area. If you shave the underarm, you impair that skin barrier and you’re more likely to develop a reaction to something you’re using over it.”

Her list of recommended deodorants includes Almay Roll-On Antiperspirant & Deodorant, Crystal Body Deodorant Stick, Crystal Roll-On Body Deodorant, Vanicream Deodorant for Sensitive Skin (aluminum-free), Vanicream Antiperspirant/Deodorant, and CertainDri Clinical Strength Roll-On. They are fragrance-free and lack propylene glycol, which is a common allergen.

Increasingly, essential oils are being added to lip balms and toothpastes, said Dr. Katta, who is also author of the 2018 book “Glow: The Dermatologist’s Guide to a Whole Foods Younger Skin Diet.” She recalled one patient who presented with chronic chapped lips. “It doesn’t matter how many lip glosses I try; it just keeps getting worse,” the patient told her. The likely culprit turned out to be ingredients contained in flavored lip balm from EOS. Reports of blistering and cracking of the lips from use of the products prompted a class action lawsuit and a notice to consumers from the Food and Drug Administration.

Another patient presented with cracked lips after switching to an “all natural” toothpaste that was labeled “gluten free.”

“It looked great,” Dr. Katta recalled. “Unfortunately it was not flavoring free. She reacted to multiple essential oils, including tea tree oil, contained in the toothpaste. This is being added to a number of toothpastes, and I think we’re going to see more of these types of reactions.”

Other toothpastes contain balsam of Peru, “which is consistently one of the top allergens in patch test clinics,” she said. “One of the components of balsam of Peru is a cinnamon compound, which can be an issue.”

Dr. Katta advises her patients to use Vaseline petroleum jelly as a lip balm and recommends Tom’s of Maine Silly Strawberry Flavor (this flavor only) toothpaste for children.

A few years ago, a teenager presented to Dr. Katta with intense bullae on the dorsum of the foot after wearing shoes without socks. “She was wearing white canvas Keds, which looked very innocuous,” she said. Patch testing revealed that the teen reacted to four different rubber accelerators. “When we contacted the company, they [acknowledged] using rubber cement to make the canvas Keds,” Dr. Katta said. “Rubber cement is an adhesive and it does contain rubber accelerators. Later, I saw two cases of children who had walked around all day at the amusement park wearing their Sperry Topsiders without any socks. We couldn’t get any information from that manufacturer, but I suspect that they also use a rubber-based glue to make those shoes.” She characterized shoes as “a real setup for a foot allergy because you have friction, sweat that’s pulling allergen out of an object, and sweat is carrying it over, especially to the dorsum of the foot.”

Dr. Katta has also noticed an uptick in the number of young patients who develop allergic reactions to dyes used to make workout clothing. “If you ever see rashes that do not involve the axillary vault but do have peraxillary accentuation, think textile allergy,” she said. “We’re seeing a lot of reactions to disperse blue clothing dyes. When you think about textile allergy from the dyes, it tends to be the blue and black clothing. It’s more likely in the setting of synthetic fabrics because they leach out dyes more easily, and it’s more likely in the setting of sweat because sweat helps pull allergen out. I’m seeing it a lot from sports uniforms and tight black leggings and tight sports bras that people are wearing. I’m also seeing some from bathing suits and swim shirts.”

Exposure to products containing the preservative methylisothiazolinone (MI) is also on the rise. It ranks as the second most frequent allergen for which the North American Contact Dermatitis Group is seeing positive results on patch testing, with rates of 13.4%. MI can be found in many skin care products and “probably about half of school glues, fabric glues, and craft glues,” Dr. Katta said. “Stick versus liquid doesn’t make a difference.” Children and teens often use craft glues, laundry detergents, and other products to create “slime” as a way to learn about viscosity, polymers, and chemical reactions. “Sometimes these children have sensitive skin, or they’re using it with prolonged contact, so they may be sensitizing themselves to the MI,” she said.

She concluded her remarks by noting that an increasing number of young patients are developing reactions to wearable medical devices such as insulin pumps and glucose monitors. “With this, the first thing to think about is frictional irritant dermatitis,” she said. “You can put Scanpor medical paper tape on people’s back for 48 hours straight to patch test them. Some people are incredibly reactive to the friction of just that tape. You also have to think about trapped allergen. One of my patients reacted to colophony, fragrance mix, and propylene glycol, all of which were contained in his skin care products. Some people are getting advice from other patients to use Mastisol liquid adhesive to help their glucose monitors stick better. Mastisol has a high rate of cross-reactivity with balsam of Peru, so it’s a fragrance allergen. That’s the first thing you want to ask patients about: what products they’re using.”

One of her patients thought she was reacting to adhesive tape on her skin, but in fact she was reacting to two different acrylates: ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) and hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA). “I know about these allergens because I see reactions from butterfly needles in dialysis patients,” Dr. Katta explained. “What happens is, these acrylates are glues or plastics used somewhere else on the device, and they can migrate through barriers.”

In one published case, a 9-year-old boy developed a reaction to ethyl cyanoacrylate contained in a glucose sensor adhesive (Dermatitis. 2017; 28[4]:289-91). It never touched the boy’s skin directly but was presumed to migrate through that tape. “The bottom line is that acrylates may induce contact dermatitis even through perceived barriers,” she said. “Their use anywhere in medical devices may prove problematic.”

Dr. Katta reported that she is a member of the advisory board for Vichy Laboratories.

AUSTIN – Not long ago, Rajani Katta, MD, received a text message from a friend who expressed concern about a rash that developed in the underarm of her teenage daughter.

The culprit turned out to be the lavender essential oil contained in an “all natural” deodorant that her daughter had recently switched to – a storyline that Dr. Katta encounters with increasing frequency in her role as clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Dr. Katta said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “When you talk about a natural allergy, it is more likely to occur if your skin barrier is compromised, so I think that’s why we’re seeing it, especially in young girls in the underarm area. If you shave the underarm, you impair that skin barrier and you’re more likely to develop a reaction to something you’re using over it.”

Her list of recommended deodorants includes Almay Roll-On Antiperspirant & Deodorant, Crystal Body Deodorant Stick, Crystal Roll-On Body Deodorant, Vanicream Deodorant for Sensitive Skin (aluminum-free), Vanicream Antiperspirant/Deodorant, and CertainDri Clinical Strength Roll-On. They are fragrance-free and lack propylene glycol, which is a common allergen.

Increasingly, essential oils are being added to lip balms and toothpastes, said Dr. Katta, who is also author of the 2018 book “Glow: The Dermatologist’s Guide to a Whole Foods Younger Skin Diet.” She recalled one patient who presented with chronic chapped lips. “It doesn’t matter how many lip glosses I try; it just keeps getting worse,” the patient told her. The likely culprit turned out to be ingredients contained in flavored lip balm from EOS. Reports of blistering and cracking of the lips from use of the products prompted a class action lawsuit and a notice to consumers from the Food and Drug Administration.

Another patient presented with cracked lips after switching to an “all natural” toothpaste that was labeled “gluten free.”

“It looked great,” Dr. Katta recalled. “Unfortunately it was not flavoring free. She reacted to multiple essential oils, including tea tree oil, contained in the toothpaste. This is being added to a number of toothpastes, and I think we’re going to see more of these types of reactions.”

Other toothpastes contain balsam of Peru, “which is consistently one of the top allergens in patch test clinics,” she said. “One of the components of balsam of Peru is a cinnamon compound, which can be an issue.”

Dr. Katta advises her patients to use Vaseline petroleum jelly as a lip balm and recommends Tom’s of Maine Silly Strawberry Flavor (this flavor only) toothpaste for children.

A few years ago, a teenager presented to Dr. Katta with intense bullae on the dorsum of the foot after wearing shoes without socks. “She was wearing white canvas Keds, which looked very innocuous,” she said. Patch testing revealed that the teen reacted to four different rubber accelerators. “When we contacted the company, they [acknowledged] using rubber cement to make the canvas Keds,” Dr. Katta said. “Rubber cement is an adhesive and it does contain rubber accelerators. Later, I saw two cases of children who had walked around all day at the amusement park wearing their Sperry Topsiders without any socks. We couldn’t get any information from that manufacturer, but I suspect that they also use a rubber-based glue to make those shoes.” She characterized shoes as “a real setup for a foot allergy because you have friction, sweat that’s pulling allergen out of an object, and sweat is carrying it over, especially to the dorsum of the foot.”

Dr. Katta has also noticed an uptick in the number of young patients who develop allergic reactions to dyes used to make workout clothing. “If you ever see rashes that do not involve the axillary vault but do have peraxillary accentuation, think textile allergy,” she said. “We’re seeing a lot of reactions to disperse blue clothing dyes. When you think about textile allergy from the dyes, it tends to be the blue and black clothing. It’s more likely in the setting of synthetic fabrics because they leach out dyes more easily, and it’s more likely in the setting of sweat because sweat helps pull allergen out. I’m seeing it a lot from sports uniforms and tight black leggings and tight sports bras that people are wearing. I’m also seeing some from bathing suits and swim shirts.”

Exposure to products containing the preservative methylisothiazolinone (MI) is also on the rise. It ranks as the second most frequent allergen for which the North American Contact Dermatitis Group is seeing positive results on patch testing, with rates of 13.4%. MI can be found in many skin care products and “probably about half of school glues, fabric glues, and craft glues,” Dr. Katta said. “Stick versus liquid doesn’t make a difference.” Children and teens often use craft glues, laundry detergents, and other products to create “slime” as a way to learn about viscosity, polymers, and chemical reactions. “Sometimes these children have sensitive skin, or they’re using it with prolonged contact, so they may be sensitizing themselves to the MI,” she said.

She concluded her remarks by noting that an increasing number of young patients are developing reactions to wearable medical devices such as insulin pumps and glucose monitors. “With this, the first thing to think about is frictional irritant dermatitis,” she said. “You can put Scanpor medical paper tape on people’s back for 48 hours straight to patch test them. Some people are incredibly reactive to the friction of just that tape. You also have to think about trapped allergen. One of my patients reacted to colophony, fragrance mix, and propylene glycol, all of which were contained in his skin care products. Some people are getting advice from other patients to use Mastisol liquid adhesive to help their glucose monitors stick better. Mastisol has a high rate of cross-reactivity with balsam of Peru, so it’s a fragrance allergen. That’s the first thing you want to ask patients about: what products they’re using.”

One of her patients thought she was reacting to adhesive tape on her skin, but in fact she was reacting to two different acrylates: ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA) and hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA). “I know about these allergens because I see reactions from butterfly needles in dialysis patients,” Dr. Katta explained. “What happens is, these acrylates are glues or plastics used somewhere else on the device, and they can migrate through barriers.”

In one published case, a 9-year-old boy developed a reaction to ethyl cyanoacrylate contained in a glucose sensor adhesive (Dermatitis. 2017; 28[4]:289-91). It never touched the boy’s skin directly but was presumed to migrate through that tape. “The bottom line is that acrylates may induce contact dermatitis even through perceived barriers,” she said. “Their use anywhere in medical devices may prove problematic.”

Dr. Katta reported that she is a member of the advisory board for Vichy Laboratories.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SPD 2019

Parabens – friend or foe?

Parabens were named nonallergen of the year! It is time that we help consumers understand that the substitutes for parabens are often worse than parabens, and parabens are not as sensitizing as we thought. Preservatives are essential parts of most cosmetics and cosmeceuticals. (I say “most” because many organic products do not have them and consequently have shorter shelf lives.) Without them, products are vulnerable to rapid decomposition and infiltration by bacteria, fungi, and molds. The preservatives that are used in the place of parabens often are sensitizers. What do we tell our patients about the safety of parabens with all of these conflicting reports? This column will focus on current thoughts regarding the safety of parabens used as preservatives. I would love to hear your thoughts.

Background

Parabens are alkyl esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid and have been used as a class of preservatives since the late 1920s and early 1930s. Parabens are found naturally in raspberries, blackberries, carrots, and cucumbers and are common ingredients in food and pharmaceuticals. They are still widely used in skin, hair, and body care products, despite the public outcry against them.1-4

There are many kinds of parabens such as butylparaben, isobutylparaben, ethylparaben, methylparaben, propylparaben, isopropylparaben, and benzylparaben, each with its own characteristics.5 Parabens are considered ideal preservative ingredients because they exhibit a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity, stability over a large pH and temperature range, have no odor, do not change color, and are water soluble enough to yield an effective concentration in a hydrophilic formulation.3 As the alkyl chain length of parabens increases, they become less water soluble and more oil soluble. Parabens penetrate the skin barrier in inverse relation to its ester chain length.6 Often, several parabens will be combined to take advantage of each paraben’s solubility characteristics.

Many patients avoid parabens because of “health risks.” Now other preservatives are being substituted for parabens, even though these ingredients may be less studied or even less safe than parabens. It is important not to lump all parabens together as they each have different characteristics. Methylparaben and propylparaben are the most commonly used parabens in skin care products.7 Combinations of parabens are notably more effective than the use of single parabens.3,8 High concentrations of any type of paraben can cause an irritant reaction on the skin, but those with longer ester chain lengths are more likely to cause irritation.

Methylparaben

The methyl ester of p-hydroxybenzoic acid is found in many skin care products. It is readily absorbed through the skin and gastrointestinal tract. It is quickly hydrolyzed and excreted in the urine and does not accumulate in the body. Studies have shown it is nontoxic, nonirritating, and nonsensitizing. It is not teratogenic, embryotoxic, or carcinogenic. Methylparaben, because of its shorter side chain groups and greater lipophilicity, has been shown to be more readily absorbed by the skin than other paraben chemicals.8,9 It is also on the low order of ingredients provoking acute and chronic toxicity.3

Propylparaben

Propylparaben is the ester form of p-hydroxybenzoic acid that has been esterified with n-propanol. It is the most commonly used antimicrobial preservative in foods, cosmetics, and drugs. It is readily absorbed through the skin and GI tract. It is quickly hydrolyzed and excreted in the urine and does not accumulate in the body.

Estrogenic activity of parabens

In a 2004 study, Darbre et al. reported on the discovery of parabens-like substances in breast tissue and published these findings in the Journal of Applied Toxicology.10 The media and public panicked, saying that parabens have estrogenic activity and can cause breast cancer. However, many studies have shown that certain parabens do not have estrogenic activity. Although some parabens have been shown to impart estrogenic effects in vitro, these are very weak. The four most commonly used parabens in cosmetic products are 10,000-fold or less potent than 17beta-estradiol.11 The potential to result in an adverse effect mediated via an estrogen mode of action has not been established in humans.6 Paraben exposure differs geographically. No correlation has been found between the amount of parabens in a geographic location and the incidence of breast cancer. Current scientific knowledge is insufficient to demonstrate a clear cancer risk caused by the topical application of cosmetics that contain parabens on normal intact skin.11

Parabens and contact dermatitis

Paraben compounds are capable of minimal penetrance through intact skin.12 When they are able to penetrate the skin – a capacity that varies among the class – parabens are rapidly metabolized to p-hydroxybenzoic acid and promptly excreted in the urine.3,11 Parabens for many years were thought to cause contact dermatitis, and there are many reports of this. However, the incidence is much lower than previously thought. In fact, parabens were named “Nonallergen of the Year in 2018” because of the low incidence of reactions in patch tests.13 Higher concentrations of parabens applied topically to skin – especially “nonintact” skin – have been shown to cause mild irritant reactions. It is likely that many of these reported cases of “contact dermatitis” were actually irritant dermatitis. Longstanding concerns about the allergenicity of parabens in relation to the skin have been rendered insignificant, as the wealth of evidence reveals little to no support for the cutaneous toxicity of these substances.11 Yim et al. add that parabens remain far less sensitizing than agents newly introduced for use in personal care products.4

Daily average exposure to parabens

It is estimated that parabens are found in 10% of personal care products. In most cases, these products contain 1% or less of parabens. If the average patient uses 50 g of personal care products a day, then the average daily exposure to parabens topically is 0.05 g. Parabens also are found in food and drugs, so the total paraben exposure per day is assumed to be about 1 mg/day. (See the 2002 Food and Chemical Toxicology article for details of how this was calculated.)7 When food, personal care products, and drug exposure rates are added, the average person is exposed to 1.29 mg/kg per day or 77.5 mg/day for a 60-kg individual. You can see that personal care products account for a fraction of exposure, as most paraben exposure comes from food.

Government opinion on the safety of parabens for the skin

Parabens long have been assessed as safe for use in cosmetic products in many countries. The European Commission stipulated a maximum concentration of 0.4% for each paraben and 0.8% for total mixture of paraben esters.4,6 While the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 prohibits the Food and Drug Administration from ruling on cosmetic ingredients, the industry-sponsored Cosmetic Ingredient Review expert panel has endorsed the European guidelines.4,6 Further, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group has pointed out that parabens continue to demonstrate the lowest prevalence of positivity (0.6%) of any major preservative available on the North American market, which includes over 10,000 cosmetic and personal care products, and remain one of the safest classes of preservatives for the skin.14 Further, the FDA has listed or classified parabens as generally regarded as safe.8

Safety of parabens

Parabens do not accumulate in tissues or organs for any appreciable length of time.6,8 In addition, carcinogenicity, cytotoxicity, or mutagenicity has not been proven in relation to parabens.8 Indeed, classical assays have shown no activity from parabens in terms of mutagenicity or carcinogenicity.11,15 Some estrogenic effects or activity that mimics estrogen have been associated with parabens in vitro, but this activity has been noted as very weak and there are no established reports of human cases in which parabens have elicited an estrogen-mediated adverse event.6,11

Concerns about a possible link between parabens and breast cancer have been largely diminished or relegated to the status of unknown and difficult to ascertain.13 Further, present knowledge provides no established link between the topical application of parabens-containing skin care formulations on healthy skin and cancer risk.10 Only intact skin should come in touch with products containing parabens to prevent irritant reactions.

Conclusion

Despite the fearful hype and reaction to one report 15 years ago, parabens continue to be safely used in numerous topical formulations. Their widespread use and lack of association with adverse events are a testament to their safety. From a dermatologic perspective, this nonallergen of the year deserves a better reputation.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems. Write to her at [email protected]

References

1. “Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics,” 6th ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1980, p. 969).

2. Toxicity: The Butyl, Ethyl, Methyl, and Propyl Esters have been found to promote allergic sensitization in humans, in “Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials,” 4th ed. (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1975, p. 929).

3. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001 Jun;39(6):513-32.

4. Dermatitis. 2014 Sep-Oct;25(5):215-31.

5. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2005 Jun;35(5):435-58.

6. Int J Toxicol. 2008;27 Suppl 4:1-82.

7. Food Chem Toxicol. 2002 Oct;40(10):1335-73.

8. Dermatitis. 2019 Jan/Feb;30(1):3-31.

9. Exp Dermatol. 2007 Oct;16(10):830-6.

10. J Appl Toxicol. 2004 Jan-Feb;24(1):5-13.

11. Dermatitis. 2019 Jan/Feb;30(1):32-45.

12. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005 Feb;43(2):279-91.

13. Dermatitis. 2018 Dec 18. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000429.

14. Dermatitis. 2018 Nov/Dec;29(6):297-309.

15. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005 Jul;43(7):985-1015.

Parabens were named nonallergen of the year! It is time that we help consumers understand that the substitutes for parabens are often worse than parabens, and parabens are not as sensitizing as we thought. Preservatives are essential parts of most cosmetics and cosmeceuticals. (I say “most” because many organic products do not have them and consequently have shorter shelf lives.) Without them, products are vulnerable to rapid decomposition and infiltration by bacteria, fungi, and molds. The preservatives that are used in the place of parabens often are sensitizers. What do we tell our patients about the safety of parabens with all of these conflicting reports? This column will focus on current thoughts regarding the safety of parabens used as preservatives. I would love to hear your thoughts.

Background

Parabens are alkyl esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid and have been used as a class of preservatives since the late 1920s and early 1930s. Parabens are found naturally in raspberries, blackberries, carrots, and cucumbers and are common ingredients in food and pharmaceuticals. They are still widely used in skin, hair, and body care products, despite the public outcry against them.1-4

There are many kinds of parabens such as butylparaben, isobutylparaben, ethylparaben, methylparaben, propylparaben, isopropylparaben, and benzylparaben, each with its own characteristics.5 Parabens are considered ideal preservative ingredients because they exhibit a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity, stability over a large pH and temperature range, have no odor, do not change color, and are water soluble enough to yield an effective concentration in a hydrophilic formulation.3 As the alkyl chain length of parabens increases, they become less water soluble and more oil soluble. Parabens penetrate the skin barrier in inverse relation to its ester chain length.6 Often, several parabens will be combined to take advantage of each paraben’s solubility characteristics.

Many patients avoid parabens because of “health risks.” Now other preservatives are being substituted for parabens, even though these ingredients may be less studied or even less safe than parabens. It is important not to lump all parabens together as they each have different characteristics. Methylparaben and propylparaben are the most commonly used parabens in skin care products.7 Combinations of parabens are notably more effective than the use of single parabens.3,8 High concentrations of any type of paraben can cause an irritant reaction on the skin, but those with longer ester chain lengths are more likely to cause irritation.

Methylparaben

The methyl ester of p-hydroxybenzoic acid is found in many skin care products. It is readily absorbed through the skin and gastrointestinal tract. It is quickly hydrolyzed and excreted in the urine and does not accumulate in the body. Studies have shown it is nontoxic, nonirritating, and nonsensitizing. It is not teratogenic, embryotoxic, or carcinogenic. Methylparaben, because of its shorter side chain groups and greater lipophilicity, has been shown to be more readily absorbed by the skin than other paraben chemicals.8,9 It is also on the low order of ingredients provoking acute and chronic toxicity.3

Propylparaben

Propylparaben is the ester form of p-hydroxybenzoic acid that has been esterified with n-propanol. It is the most commonly used antimicrobial preservative in foods, cosmetics, and drugs. It is readily absorbed through the skin and GI tract. It is quickly hydrolyzed and excreted in the urine and does not accumulate in the body.

Estrogenic activity of parabens

In a 2004 study, Darbre et al. reported on the discovery of parabens-like substances in breast tissue and published these findings in the Journal of Applied Toxicology.10 The media and public panicked, saying that parabens have estrogenic activity and can cause breast cancer. However, many studies have shown that certain parabens do not have estrogenic activity. Although some parabens have been shown to impart estrogenic effects in vitro, these are very weak. The four most commonly used parabens in cosmetic products are 10,000-fold or less potent than 17beta-estradiol.11 The potential to result in an adverse effect mediated via an estrogen mode of action has not been established in humans.6 Paraben exposure differs geographically. No correlation has been found between the amount of parabens in a geographic location and the incidence of breast cancer. Current scientific knowledge is insufficient to demonstrate a clear cancer risk caused by the topical application of cosmetics that contain parabens on normal intact skin.11

Parabens and contact dermatitis

Paraben compounds are capable of minimal penetrance through intact skin.12 When they are able to penetrate the skin – a capacity that varies among the class – parabens are rapidly metabolized to p-hydroxybenzoic acid and promptly excreted in the urine.3,11 Parabens for many years were thought to cause contact dermatitis, and there are many reports of this. However, the incidence is much lower than previously thought. In fact, parabens were named “Nonallergen of the Year in 2018” because of the low incidence of reactions in patch tests.13 Higher concentrations of parabens applied topically to skin – especially “nonintact” skin – have been shown to cause mild irritant reactions. It is likely that many of these reported cases of “contact dermatitis” were actually irritant dermatitis. Longstanding concerns about the allergenicity of parabens in relation to the skin have been rendered insignificant, as the wealth of evidence reveals little to no support for the cutaneous toxicity of these substances.11 Yim et al. add that parabens remain far less sensitizing than agents newly introduced for use in personal care products.4

Daily average exposure to parabens

It is estimated that parabens are found in 10% of personal care products. In most cases, these products contain 1% or less of parabens. If the average patient uses 50 g of personal care products a day, then the average daily exposure to parabens topically is 0.05 g. Parabens also are found in food and drugs, so the total paraben exposure per day is assumed to be about 1 mg/day. (See the 2002 Food and Chemical Toxicology article for details of how this was calculated.)7 When food, personal care products, and drug exposure rates are added, the average person is exposed to 1.29 mg/kg per day or 77.5 mg/day for a 60-kg individual. You can see that personal care products account for a fraction of exposure, as most paraben exposure comes from food.

Government opinion on the safety of parabens for the skin

Parabens long have been assessed as safe for use in cosmetic products in many countries. The European Commission stipulated a maximum concentration of 0.4% for each paraben and 0.8% for total mixture of paraben esters.4,6 While the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 prohibits the Food and Drug Administration from ruling on cosmetic ingredients, the industry-sponsored Cosmetic Ingredient Review expert panel has endorsed the European guidelines.4,6 Further, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group has pointed out that parabens continue to demonstrate the lowest prevalence of positivity (0.6%) of any major preservative available on the North American market, which includes over 10,000 cosmetic and personal care products, and remain one of the safest classes of preservatives for the skin.14 Further, the FDA has listed or classified parabens as generally regarded as safe.8

Safety of parabens

Parabens do not accumulate in tissues or organs for any appreciable length of time.6,8 In addition, carcinogenicity, cytotoxicity, or mutagenicity has not been proven in relation to parabens.8 Indeed, classical assays have shown no activity from parabens in terms of mutagenicity or carcinogenicity.11,15 Some estrogenic effects or activity that mimics estrogen have been associated with parabens in vitro, but this activity has been noted as very weak and there are no established reports of human cases in which parabens have elicited an estrogen-mediated adverse event.6,11

Concerns about a possible link between parabens and breast cancer have been largely diminished or relegated to the status of unknown and difficult to ascertain.13 Further, present knowledge provides no established link between the topical application of parabens-containing skin care formulations on healthy skin and cancer risk.10 Only intact skin should come in touch with products containing parabens to prevent irritant reactions.

Conclusion

Despite the fearful hype and reaction to one report 15 years ago, parabens continue to be safely used in numerous topical formulations. Their widespread use and lack of association with adverse events are a testament to their safety. From a dermatologic perspective, this nonallergen of the year deserves a better reputation.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems. Write to her at [email protected]

References

1. “Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics,” 6th ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1980, p. 969).

2. Toxicity: The Butyl, Ethyl, Methyl, and Propyl Esters have been found to promote allergic sensitization in humans, in “Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials,” 4th ed. (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1975, p. 929).

3. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001 Jun;39(6):513-32.

4. Dermatitis. 2014 Sep-Oct;25(5):215-31.

5. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2005 Jun;35(5):435-58.

6. Int J Toxicol. 2008;27 Suppl 4:1-82.

7. Food Chem Toxicol. 2002 Oct;40(10):1335-73.

8. Dermatitis. 2019 Jan/Feb;30(1):3-31.

9. Exp Dermatol. 2007 Oct;16(10):830-6.

10. J Appl Toxicol. 2004 Jan-Feb;24(1):5-13.

11. Dermatitis. 2019 Jan/Feb;30(1):32-45.

12. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005 Feb;43(2):279-91.

13. Dermatitis. 2018 Dec 18. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000429.

14. Dermatitis. 2018 Nov/Dec;29(6):297-309.

15. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005 Jul;43(7):985-1015.

Parabens were named nonallergen of the year! It is time that we help consumers understand that the substitutes for parabens are often worse than parabens, and parabens are not as sensitizing as we thought. Preservatives are essential parts of most cosmetics and cosmeceuticals. (I say “most” because many organic products do not have them and consequently have shorter shelf lives.) Without them, products are vulnerable to rapid decomposition and infiltration by bacteria, fungi, and molds. The preservatives that are used in the place of parabens often are sensitizers. What do we tell our patients about the safety of parabens with all of these conflicting reports? This column will focus on current thoughts regarding the safety of parabens used as preservatives. I would love to hear your thoughts.

Background

Parabens are alkyl esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid and have been used as a class of preservatives since the late 1920s and early 1930s. Parabens are found naturally in raspberries, blackberries, carrots, and cucumbers and are common ingredients in food and pharmaceuticals. They are still widely used in skin, hair, and body care products, despite the public outcry against them.1-4

There are many kinds of parabens such as butylparaben, isobutylparaben, ethylparaben, methylparaben, propylparaben, isopropylparaben, and benzylparaben, each with its own characteristics.5 Parabens are considered ideal preservative ingredients because they exhibit a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity, stability over a large pH and temperature range, have no odor, do not change color, and are water soluble enough to yield an effective concentration in a hydrophilic formulation.3 As the alkyl chain length of parabens increases, they become less water soluble and more oil soluble. Parabens penetrate the skin barrier in inverse relation to its ester chain length.6 Often, several parabens will be combined to take advantage of each paraben’s solubility characteristics.

Many patients avoid parabens because of “health risks.” Now other preservatives are being substituted for parabens, even though these ingredients may be less studied or even less safe than parabens. It is important not to lump all parabens together as they each have different characteristics. Methylparaben and propylparaben are the most commonly used parabens in skin care products.7 Combinations of parabens are notably more effective than the use of single parabens.3,8 High concentrations of any type of paraben can cause an irritant reaction on the skin, but those with longer ester chain lengths are more likely to cause irritation.

Methylparaben

The methyl ester of p-hydroxybenzoic acid is found in many skin care products. It is readily absorbed through the skin and gastrointestinal tract. It is quickly hydrolyzed and excreted in the urine and does not accumulate in the body. Studies have shown it is nontoxic, nonirritating, and nonsensitizing. It is not teratogenic, embryotoxic, or carcinogenic. Methylparaben, because of its shorter side chain groups and greater lipophilicity, has been shown to be more readily absorbed by the skin than other paraben chemicals.8,9 It is also on the low order of ingredients provoking acute and chronic toxicity.3

Propylparaben

Propylparaben is the ester form of p-hydroxybenzoic acid that has been esterified with n-propanol. It is the most commonly used antimicrobial preservative in foods, cosmetics, and drugs. It is readily absorbed through the skin and GI tract. It is quickly hydrolyzed and excreted in the urine and does not accumulate in the body.

Estrogenic activity of parabens

In a 2004 study, Darbre et al. reported on the discovery of parabens-like substances in breast tissue and published these findings in the Journal of Applied Toxicology.10 The media and public panicked, saying that parabens have estrogenic activity and can cause breast cancer. However, many studies have shown that certain parabens do not have estrogenic activity. Although some parabens have been shown to impart estrogenic effects in vitro, these are very weak. The four most commonly used parabens in cosmetic products are 10,000-fold or less potent than 17beta-estradiol.11 The potential to result in an adverse effect mediated via an estrogen mode of action has not been established in humans.6 Paraben exposure differs geographically. No correlation has been found between the amount of parabens in a geographic location and the incidence of breast cancer. Current scientific knowledge is insufficient to demonstrate a clear cancer risk caused by the topical application of cosmetics that contain parabens on normal intact skin.11

Parabens and contact dermatitis

Paraben compounds are capable of minimal penetrance through intact skin.12 When they are able to penetrate the skin – a capacity that varies among the class – parabens are rapidly metabolized to p-hydroxybenzoic acid and promptly excreted in the urine.3,11 Parabens for many years were thought to cause contact dermatitis, and there are many reports of this. However, the incidence is much lower than previously thought. In fact, parabens were named “Nonallergen of the Year in 2018” because of the low incidence of reactions in patch tests.13 Higher concentrations of parabens applied topically to skin – especially “nonintact” skin – have been shown to cause mild irritant reactions. It is likely that many of these reported cases of “contact dermatitis” were actually irritant dermatitis. Longstanding concerns about the allergenicity of parabens in relation to the skin have been rendered insignificant, as the wealth of evidence reveals little to no support for the cutaneous toxicity of these substances.11 Yim et al. add that parabens remain far less sensitizing than agents newly introduced for use in personal care products.4

Daily average exposure to parabens

It is estimated that parabens are found in 10% of personal care products. In most cases, these products contain 1% or less of parabens. If the average patient uses 50 g of personal care products a day, then the average daily exposure to parabens topically is 0.05 g. Parabens also are found in food and drugs, so the total paraben exposure per day is assumed to be about 1 mg/day. (See the 2002 Food and Chemical Toxicology article for details of how this was calculated.)7 When food, personal care products, and drug exposure rates are added, the average person is exposed to 1.29 mg/kg per day or 77.5 mg/day for a 60-kg individual. You can see that personal care products account for a fraction of exposure, as most paraben exposure comes from food.

Government opinion on the safety of parabens for the skin

Parabens long have been assessed as safe for use in cosmetic products in many countries. The European Commission stipulated a maximum concentration of 0.4% for each paraben and 0.8% for total mixture of paraben esters.4,6 While the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 prohibits the Food and Drug Administration from ruling on cosmetic ingredients, the industry-sponsored Cosmetic Ingredient Review expert panel has endorsed the European guidelines.4,6 Further, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group has pointed out that parabens continue to demonstrate the lowest prevalence of positivity (0.6%) of any major preservative available on the North American market, which includes over 10,000 cosmetic and personal care products, and remain one of the safest classes of preservatives for the skin.14 Further, the FDA has listed or classified parabens as generally regarded as safe.8

Safety of parabens

Parabens do not accumulate in tissues or organs for any appreciable length of time.6,8 In addition, carcinogenicity, cytotoxicity, or mutagenicity has not been proven in relation to parabens.8 Indeed, classical assays have shown no activity from parabens in terms of mutagenicity or carcinogenicity.11,15 Some estrogenic effects or activity that mimics estrogen have been associated with parabens in vitro, but this activity has been noted as very weak and there are no established reports of human cases in which parabens have elicited an estrogen-mediated adverse event.6,11

Concerns about a possible link between parabens and breast cancer have been largely diminished or relegated to the status of unknown and difficult to ascertain.13 Further, present knowledge provides no established link between the topical application of parabens-containing skin care formulations on healthy skin and cancer risk.10 Only intact skin should come in touch with products containing parabens to prevent irritant reactions.

Conclusion

Despite the fearful hype and reaction to one report 15 years ago, parabens continue to be safely used in numerous topical formulations. Their widespread use and lack of association with adverse events are a testament to their safety. From a dermatologic perspective, this nonallergen of the year deserves a better reputation.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems. Write to her at [email protected]

References

1. “Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics,” 6th ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1980, p. 969).

2. Toxicity: The Butyl, Ethyl, Methyl, and Propyl Esters have been found to promote allergic sensitization in humans, in “Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials,” 4th ed. (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1975, p. 929).

3. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001 Jun;39(6):513-32.

4. Dermatitis. 2014 Sep-Oct;25(5):215-31.

5. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2005 Jun;35(5):435-58.

6. Int J Toxicol. 2008;27 Suppl 4:1-82.

7. Food Chem Toxicol. 2002 Oct;40(10):1335-73.

8. Dermatitis. 2019 Jan/Feb;30(1):3-31.

9. Exp Dermatol. 2007 Oct;16(10):830-6.

10. J Appl Toxicol. 2004 Jan-Feb;24(1):5-13.

11. Dermatitis. 2019 Jan/Feb;30(1):32-45.

12. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005 Feb;43(2):279-91.

13. Dermatitis. 2018 Dec 18. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000429.

14. Dermatitis. 2018 Nov/Dec;29(6):297-309.

15. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005 Jul;43(7):985-1015.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis With Sparing of Exposed Psoriasis Plaques

To the Editor:

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction against antigens to which the skin’s immune system was previously sensitized. The initial sensitization requires penetration of the antigen through the stratum corneum. Thus, the ability of a particle to cause ACD is related to its molecular structure and size, lipophilicity, and protein-binding affinity, as well as the dose and duration of exposure.1 Psoriasis typically presents as well-demarcated areas of skin that may be erythematous, indurated, and scaly to variable degrees. Histologically, psoriasis plaques are characterized by epidermal hyperplasia in the presence of a T-cell infiltrate and neutrophilic microabscesses. We report a case of a patient with plaque-type psoriasis who experienced ACD with sparing of exposed psoriatic plaques.

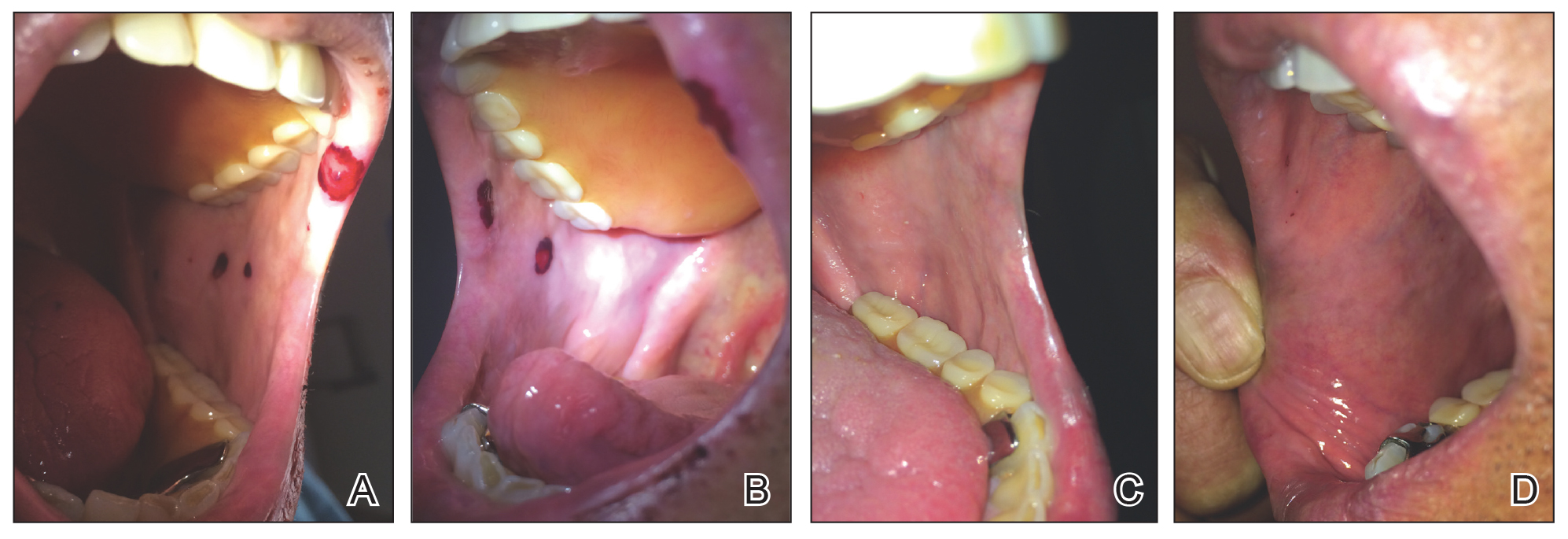

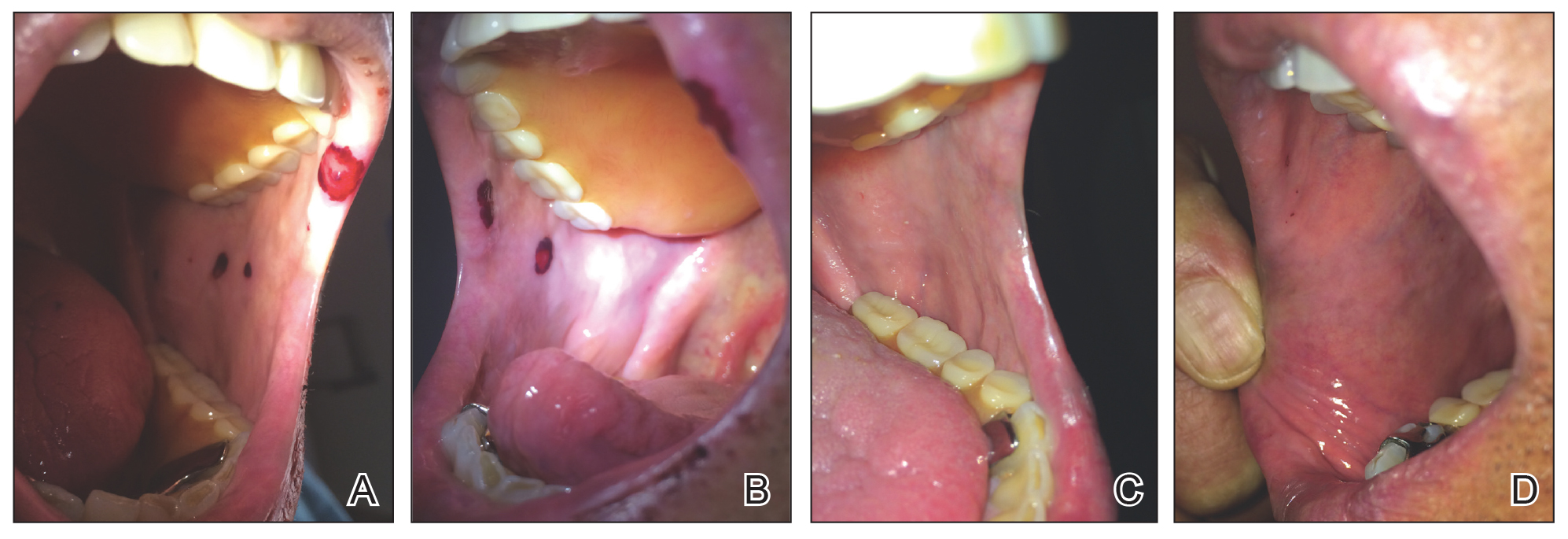

A 45-year-old man with a 5-year history of generalized moderate to severe psoriasis undergoing therapy with ustekinumab 45 mg subcutaneously once every 12 weeks presented to the emergency department with intensely erythematous, pruritic, vesicular lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs within 24 hours of exposure to poison oak while hiking. The patient reported pruritus, pain, and swelling of the affected areas. On physical examination, he was afebrile. Widespread erythematous vesicular lesions were noted on the face, trunk, arms, and legs, sparing the well-demarcated scaly psoriatic plaques on the arms and legs (Figure). The patient was given intravenous fluids and intravenous diphenhydramine. After responding to initial treatment, the patient was discharged with ibuprofen and a tapering dose of oral prednisone from 60 mg 5 times daily, to 40 mg 5 times daily, to 20 mg 5 times daily over 15 days.

star), with a linear border demarcating the ACD lesion and the unaffected psoriatic plaque (black arrow).

Allergic contact dermatitis occurs after sensitization to environmental allergens or haptens. Clinically, ACD is characterized by pruritic, erythematous, vesicular papules and plaques. The predominant effector cells in ACD are CD8+ T cells, along with contributions from helper T cells (TH2). Together, these cell types produce an environment enriched in IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-17, and tumor necrosis factor α.2 Ultimately, the ACD response induces keratinocyte apoptosis via cytotoxic effects.3,4

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease that presents clinically as erythematous well-demarcated plaques with a micaceous scale. The immunologic environment of psoriasis plaques is characterized by infiltration of CD4+ TH17 cells and elevated levels of IL-17, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-1β, which induce keratinocyte hyperproliferation through a complex mechanism resulting in hyperkeratosis composed of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis, a neutrophilic infiltrate, and Munro microabscesses.5

The predominant effector cells and the final effects on keratinocyte survival are divergent in psoriasis and ACD. The possibly antagonistic relationship between these immunologic processes is further supported by epidemiologic studies demonstrating a decreased incidence of ACD in patients with psoriasis.6,7

Our patient demonstrated a typical ACD reaction in response to exposure to urushiol, the allergen present in poison oak, in areas unaffected by psoriasis plaques. Interestingly, the patient displayed this response even while undergoing therapy with ustekinumab, a fully humanized antibody that binds IL-12 and IL-23 and ultimately downregulates TH17 cell-mediated release of IL-17 in the treatment of psoriasis. Although IL-17 also has been implicated in ACD, the lack of inhibition of ACD with ustekinumab treatment was previously demonstrated in a small retrospective study, indicating a potentially different source of IL-17 in ACD.8

Our patient did not demonstrate a typical ACD response in areas of active psoriasis plaques. This phenomenon was of great interest to us. It is possible that the presence of hyperkeratosis, manifested clinically as scaling, served as a mechanical barrier preventing the diffusion and exposure of cutaneous immune cells to urushiol. On the other hand, it is possible that the immunologic environment of the active psoriasis plaque was altered in such a way that it did not demonstrate the typical response to allergen exposure.

We hypothesize that the lack of a typical ACD response at sites of psoriatic plaques in our patient may be attributed to the intensity and duration of exposure to the allergen. Quaranta et al9 reported a typical ACD clinical response and a mixed immunohistologic response to nickel patch testing at sites of active plaques in nickel-sensitized psoriasis patients. Patch testing involves 48 hours of direct contact with an allergen, while our patient experienced an estimated 8 to 10 hours of exposure to the allergen prior to removal via washing. Supporting this line of reasoning, a proportion of patients who are responsive to nickel patch testing do not exhibit clinical symptoms in response to casual nickel exposure.10 Although a physical barrier effect due to hyperkeratosis may have contributed to the lack of ACD response in sites of psoriasis plaques in our patient, it remains possible that a more limited duration of exposure to the allergen is not sufficient to overcome the native immunologic milieu of the psoriasis plaque and induce the immunologic cascade resulting in ACD. Further research into the potentially antagonistic relationship of psoriasis and ACD should be performed to elucidate the interaction between these two common conditions.

- Kimber I, Basketter DA, Gerberick GF, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:201-211.

- Vocanson M, Hennino A, Cluzel-Tailhardat M, et al. CD8+ T cells are effector cells of contact dermatitis to common skin allergens in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:815-820.

- Akiba H, Kehren J, Ducluzeau MT, et al. Skin inflammation during contact hypersensitivity is mediated by early recruitment of CD8+ T cytotoxic 1 cells inducing keratinocyte apoptosis. J Immunol. 2002;168:3079-3087.

- Trautmann A, Akdis M, Kleemann D, et al. T cell-mediated Fas-induced keratinocyte apoptosis plays a key pathogenetic role in eczematous dermatitis. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:25-35.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Bangsgaard N, Engkilde K, Thyssen JP, et al. Inverse relationship between contact allergy and psoriasis: results from a patient- and a population-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1119-1123.

- Henseler T, Christophers E. Disease concomitance in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:982-986.

- Bangsgaard N, Zachariae C, Menne T, et al. Lack of effect of ustekinumab in treatment of allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;65:227-230.

- Quaranta M, Eyerich S, Knapp B, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis in psoriasis patients: typical, delayed, and non-interacting. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101814.

- Kimber I, Basketter DA, Gerberick GF, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:201-211.

To the Editor:

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction against antigens to which the skin’s immune system was previously sensitized. The initial sensitization requires penetration of the antigen through the stratum corneum. Thus, the ability of a particle to cause ACD is related to its molecular structure and size, lipophilicity, and protein-binding affinity, as well as the dose and duration of exposure.1 Psoriasis typically presents as well-demarcated areas of skin that may be erythematous, indurated, and scaly to variable degrees. Histologically, psoriasis plaques are characterized by epidermal hyperplasia in the presence of a T-cell infiltrate and neutrophilic microabscesses. We report a case of a patient with plaque-type psoriasis who experienced ACD with sparing of exposed psoriatic plaques.