User login

Orbital Granuloma Formation Following Autoinjection of Paraffin Oil: Management Considerations

To the Editor:

Injectable fillers are an increasingly common means of achieving minimally invasive facial rejuvenation. In the hands of well-trained practitioners, these compounds typically are well tolerated, effective, and have a strong safety profile1; however, there have been reports of complications, including vision loss,2 orbital infarction,3 persistent inflammatory nodules,4 and infection.4,5 Paraffin, a derivative of mineral oil, currently is used in cosmetic products and medical ointments.6 In the early 1900s, it often was injected into the body for various medical procedures, such as to create prosthetic testicles, to treat bladder incontinence, and eventually to correct facial contour defects.7,8 Due to adverse effects, injection of paraffin oil was discontinued in the Western medical community around the time of World War I.7 Unfortunately, some patients continue to self-inject paraffin oil for cosmetic purposes today. We present a case of foreign-body granuloma formation mimicking periorbital cellulitis following self-injection of paraffin oil. Our patient developed serious periorbital sequelae that required surgical intervention to restore normal anatomic function.

A 60-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented to the emergency department with facial swelling and a rash of 2 weeks’ duration. She reported that she had purchased what she believed was a cosmetic product at a local flea market 2 weeks prior to presentation. Her purchase included needles and a syringe with verbal instructions for injection into the face. She was told the product was used to treat wrinkles and referred to the injectable material as “oil” when providing her history. She reported that she had injected the material into the bilateral lower eyelids, left lateral lip, and left lateral chin. Three days later, she developed tingling and itching with swelling and redness at the injection sites. The patient was evaluated by the emergency department team and was prescribed a 10-day course of clindamycin empirically for suspected facial cellulitis.

The patient returned to the emergency department 12 days later upon completion of the antibiotic course with worsening edema and erythema. Examination revealed indurated, erythematous, and edematous warm plaques on the face that were concentrated around the prior injection sites with substantial periorbital erythema and edema (Figure 1). A consultation with oculoplastic surgery was obtained. Mechanical ptosis of the right eyelid was noted. Visual acuity was 20/30 in both eyes with habitual correction. Intraocular pressure was soft to palpation, and the pupils were round and reactive with no evidence of a relative afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular motility was intact bilaterally. Examination of the conjunctiva and sclera revealed bilateral conjunctival injection with chemosis of the right eye. The remainder of the anterior and posterior segment examination was within normal limits bilaterally.

Computed tomography of the face showed extensive facial and periorbital swelling without abscess. A dermatology consultation was obtained. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained from the left lower face and were sent for hematoxylin and eosin stain and tissue culture (bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacillus). Given the possibility of facial and periorbital cellulitis, empiric intravenous antibiotic therapy was initiated.

The tissue culture revealed normal skin flora. The biopsy results indicated a foreign-body reaction consistent with paraffin granuloma (Figures 2 and 3). Fite-Faraco, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and periodic acid–Schiff stains were all negative for infection. A diagnosis of foreign-body granuloma was established. Oral minocycline at a dosage of 100 mg twice daily was started, and the patient was discharged.

After 4 weeks of minocycline therapy, the patient showed no improvement and returned to the emergency department with worsening symptoms. She was readmitted and started on intravenous prednisone (1.5 mg/kg/d). Over the ensuing 5 days, the edema, erythema, conjunctival injection, and chemosis demonstrated notable improvement. She was subsequently discharged on an oral prednisone taper. Unfortunately, she did not respond to a trial of intralesional steroid injections to an area of granuloma formation on the left chin performed in the hospital before she was discharged.

In the ensuing months, she began to develop cicatricial ectropion of the right lower eyelid and mechanical ptosis of the right upper eyelid. Ten months after initial self-injection, staged surgical excision was initiated by an oculoplastic surgeon (I.V.) with the goal of debulking the periorbital region to correct the ectropion and mechanical ptosis. A transconjunctival approach was used to carefully excise the material while still maintaining the architecture of the lower eyelid. The ectropion was surgically corrected concurrently.

One month after excision, serial injections of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg/mL were administered to the right lower eyelid and anterior orbit for 3 months. Fifteen weeks after the first surgery, a second surgery was performed to address residual medial right lower eyelid induration, right upper eyelid mechanical ptosis, and left orbital inflammation. During the postoperative period, serial monthly injections of 5-FU and triamcinolone acetonide were again performed beginning at the first postoperative month.

The surgical excisions resulted in notable improvement 3 months following excision (Figure 4). The patient noted improved ocular surface comfort with decreased foreign-body sensation and tearing. She also was pleased with the improved cosmetic outcome.

Crude substances such as paraffin, petroleum jelly, and lanolin were used for aesthetic purposes in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, initially with satisfying results; however, long-term adverse effects such as hardening of the skin, swelling, granuloma formation, ulceration, infections, and abscesses have discouraged its use by medical professionals today.5 Since paraffin is resistant to degradation and absorption, foreign-body reactions may occur upon injection. These reactions are characterized by replacement of normal subcutaneous tissue by cystic spaces of paraffin oil and/or calcification, similar to the appearance of Swiss cheese on histology and surrounded by various inflammatory cells and fibrous tissue.9,10

Clinically, there is an acute inflammatory phase followed by a latent phase of chronic granulomatous inflammation that can last for years.10 Our patient presented during the acute phase, with erythematous and edematous warm plaques around the eye mimicking an orbital infection.

The treatment of choice for paraffin granuloma is complete surgical excision to prevent recurrence.6,9 However, intralesional corticosteroids are preferred in the facial area, especially if complete removal is not possible.10 Intralesional corticosteroid injections inhibit fibroblast and macrophage activity as well as the deposition of collagen, leading to reduced pain and swelling in most cases.11 Additionally, combining antimitotic agents such as 5-FU with a corticosteroid might reduce the risk for cortisone skin atrophy.12 In our case, the patient did not respond to combined 5-FU with intralesional steroids and required oral corticosteroids while awaiting serial excisions.

Our case highlights several important points in the management of paraffin granuloma. First, the clinician must perform a thorough patient history, as surreptitious use of non–medical-grade fillers is more common than one might think.13 Second, the initial presentation of these patients can mimic an infectious process. Careful history, testing, and observation can aid in making the appropriate diagnosis. Finally, treatment of these patients is complex. The mainstays of therapy are systemic anti-inflammatory medications, time, and supportive care. In some cases, surgery may be required. When processes such as paraffin granulomas involve the periorbital region, particular care is required to avoid cicatricial lagophthalmos, ectropion, or retraction. Thoughtful surgical manipulation is required to avoid these complications, which indeed may occur even with the most appropriate interventions.

- Duker D, Erdmann R, Hartmann V, et al. The impact of adverse reactions to injectable filler substances on quality of life: results from the Berlin Injectable Filler Safety (IFS)—study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1013-1020.

- Prado G, Rodriguez-Feliz J. Ocular pain and impending blindness during facial cosmetic injections: is your office prepared? [published online December 28, 2016]. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:199-203.

- Roberts SA, Arthurs BP. Severe visual loss and orbital infarction following periorbital aesthetic poly-(L)-lactic acid (PLLA) injection. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28:E68-E70.

- Cassuto D, Pignatti M, Pacchioni L, et al. Management of complications caused by permanent fillers in the face: a treatment algorithm. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:215E-227E.

- Haneke E. Adverse effects of fillers and their histopathology. Facial Plast Surg. 2014;30:599-614.

- Friedrich RE, Zustin J. Paraffinoma of lips and oral mucosa: case report and brief review of literature. GMS Interdiscip Plast Reconstr Surg DGPW. 2014;3:Doc05.

- Matton G, Anseeuw A, De Keyser F. The history of injectable biomaterials and the biology of collagen. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1985;9:133-140.

- Glicenstein J. Les premiers fillers, Vaseline et paraffine. du miracle a la catastrope. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2007;52:157-161.

- Cohen JL, Keoleian CM, Krull EA. Penile paraffinoma: self-injection with mineral oil. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;47:S251-S253.

- Legaspi-Vicerra ME, Field LM. Paraffin granulomata, “witch’s chin,” and nasal deformities excision and reconstruction with reduction chinplasty and open rhinotomy resection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2010;3:54-58.

- Carlos-Fabuel L, Marzal-Gamarra C, Marti-Alamo S, et al. Foreign body granulomatous reactions to cosmetic fillers. J Clin Exp Dent. 2012;4:E244-E247.

- Lemperle G, Gauthier-Hazan N. Foreign body granulomas after all injectable dermal fillers: part 2. treatment options. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1864-1873.

- Seok J, Hong JY, Park KY, et al. Delayed immunologic complications due to injectable fillers by unlicensed practitioners: our experiences and a review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:41-44.

To the Editor:

Injectable fillers are an increasingly common means of achieving minimally invasive facial rejuvenation. In the hands of well-trained practitioners, these compounds typically are well tolerated, effective, and have a strong safety profile1; however, there have been reports of complications, including vision loss,2 orbital infarction,3 persistent inflammatory nodules,4 and infection.4,5 Paraffin, a derivative of mineral oil, currently is used in cosmetic products and medical ointments.6 In the early 1900s, it often was injected into the body for various medical procedures, such as to create prosthetic testicles, to treat bladder incontinence, and eventually to correct facial contour defects.7,8 Due to adverse effects, injection of paraffin oil was discontinued in the Western medical community around the time of World War I.7 Unfortunately, some patients continue to self-inject paraffin oil for cosmetic purposes today. We present a case of foreign-body granuloma formation mimicking periorbital cellulitis following self-injection of paraffin oil. Our patient developed serious periorbital sequelae that required surgical intervention to restore normal anatomic function.

A 60-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented to the emergency department with facial swelling and a rash of 2 weeks’ duration. She reported that she had purchased what she believed was a cosmetic product at a local flea market 2 weeks prior to presentation. Her purchase included needles and a syringe with verbal instructions for injection into the face. She was told the product was used to treat wrinkles and referred to the injectable material as “oil” when providing her history. She reported that she had injected the material into the bilateral lower eyelids, left lateral lip, and left lateral chin. Three days later, she developed tingling and itching with swelling and redness at the injection sites. The patient was evaluated by the emergency department team and was prescribed a 10-day course of clindamycin empirically for suspected facial cellulitis.

The patient returned to the emergency department 12 days later upon completion of the antibiotic course with worsening edema and erythema. Examination revealed indurated, erythematous, and edematous warm plaques on the face that were concentrated around the prior injection sites with substantial periorbital erythema and edema (Figure 1). A consultation with oculoplastic surgery was obtained. Mechanical ptosis of the right eyelid was noted. Visual acuity was 20/30 in both eyes with habitual correction. Intraocular pressure was soft to palpation, and the pupils were round and reactive with no evidence of a relative afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular motility was intact bilaterally. Examination of the conjunctiva and sclera revealed bilateral conjunctival injection with chemosis of the right eye. The remainder of the anterior and posterior segment examination was within normal limits bilaterally.

Computed tomography of the face showed extensive facial and periorbital swelling without abscess. A dermatology consultation was obtained. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained from the left lower face and were sent for hematoxylin and eosin stain and tissue culture (bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacillus). Given the possibility of facial and periorbital cellulitis, empiric intravenous antibiotic therapy was initiated.

The tissue culture revealed normal skin flora. The biopsy results indicated a foreign-body reaction consistent with paraffin granuloma (Figures 2 and 3). Fite-Faraco, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and periodic acid–Schiff stains were all negative for infection. A diagnosis of foreign-body granuloma was established. Oral minocycline at a dosage of 100 mg twice daily was started, and the patient was discharged.

After 4 weeks of minocycline therapy, the patient showed no improvement and returned to the emergency department with worsening symptoms. She was readmitted and started on intravenous prednisone (1.5 mg/kg/d). Over the ensuing 5 days, the edema, erythema, conjunctival injection, and chemosis demonstrated notable improvement. She was subsequently discharged on an oral prednisone taper. Unfortunately, she did not respond to a trial of intralesional steroid injections to an area of granuloma formation on the left chin performed in the hospital before she was discharged.

In the ensuing months, she began to develop cicatricial ectropion of the right lower eyelid and mechanical ptosis of the right upper eyelid. Ten months after initial self-injection, staged surgical excision was initiated by an oculoplastic surgeon (I.V.) with the goal of debulking the periorbital region to correct the ectropion and mechanical ptosis. A transconjunctival approach was used to carefully excise the material while still maintaining the architecture of the lower eyelid. The ectropion was surgically corrected concurrently.

One month after excision, serial injections of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg/mL were administered to the right lower eyelid and anterior orbit for 3 months. Fifteen weeks after the first surgery, a second surgery was performed to address residual medial right lower eyelid induration, right upper eyelid mechanical ptosis, and left orbital inflammation. During the postoperative period, serial monthly injections of 5-FU and triamcinolone acetonide were again performed beginning at the first postoperative month.

The surgical excisions resulted in notable improvement 3 months following excision (Figure 4). The patient noted improved ocular surface comfort with decreased foreign-body sensation and tearing. She also was pleased with the improved cosmetic outcome.

Crude substances such as paraffin, petroleum jelly, and lanolin were used for aesthetic purposes in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, initially with satisfying results; however, long-term adverse effects such as hardening of the skin, swelling, granuloma formation, ulceration, infections, and abscesses have discouraged its use by medical professionals today.5 Since paraffin is resistant to degradation and absorption, foreign-body reactions may occur upon injection. These reactions are characterized by replacement of normal subcutaneous tissue by cystic spaces of paraffin oil and/or calcification, similar to the appearance of Swiss cheese on histology and surrounded by various inflammatory cells and fibrous tissue.9,10

Clinically, there is an acute inflammatory phase followed by a latent phase of chronic granulomatous inflammation that can last for years.10 Our patient presented during the acute phase, with erythematous and edematous warm plaques around the eye mimicking an orbital infection.

The treatment of choice for paraffin granuloma is complete surgical excision to prevent recurrence.6,9 However, intralesional corticosteroids are preferred in the facial area, especially if complete removal is not possible.10 Intralesional corticosteroid injections inhibit fibroblast and macrophage activity as well as the deposition of collagen, leading to reduced pain and swelling in most cases.11 Additionally, combining antimitotic agents such as 5-FU with a corticosteroid might reduce the risk for cortisone skin atrophy.12 In our case, the patient did not respond to combined 5-FU with intralesional steroids and required oral corticosteroids while awaiting serial excisions.

Our case highlights several important points in the management of paraffin granuloma. First, the clinician must perform a thorough patient history, as surreptitious use of non–medical-grade fillers is more common than one might think.13 Second, the initial presentation of these patients can mimic an infectious process. Careful history, testing, and observation can aid in making the appropriate diagnosis. Finally, treatment of these patients is complex. The mainstays of therapy are systemic anti-inflammatory medications, time, and supportive care. In some cases, surgery may be required. When processes such as paraffin granulomas involve the periorbital region, particular care is required to avoid cicatricial lagophthalmos, ectropion, or retraction. Thoughtful surgical manipulation is required to avoid these complications, which indeed may occur even with the most appropriate interventions.

To the Editor:

Injectable fillers are an increasingly common means of achieving minimally invasive facial rejuvenation. In the hands of well-trained practitioners, these compounds typically are well tolerated, effective, and have a strong safety profile1; however, there have been reports of complications, including vision loss,2 orbital infarction,3 persistent inflammatory nodules,4 and infection.4,5 Paraffin, a derivative of mineral oil, currently is used in cosmetic products and medical ointments.6 In the early 1900s, it often was injected into the body for various medical procedures, such as to create prosthetic testicles, to treat bladder incontinence, and eventually to correct facial contour defects.7,8 Due to adverse effects, injection of paraffin oil was discontinued in the Western medical community around the time of World War I.7 Unfortunately, some patients continue to self-inject paraffin oil for cosmetic purposes today. We present a case of foreign-body granuloma formation mimicking periorbital cellulitis following self-injection of paraffin oil. Our patient developed serious periorbital sequelae that required surgical intervention to restore normal anatomic function.

A 60-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented to the emergency department with facial swelling and a rash of 2 weeks’ duration. She reported that she had purchased what she believed was a cosmetic product at a local flea market 2 weeks prior to presentation. Her purchase included needles and a syringe with verbal instructions for injection into the face. She was told the product was used to treat wrinkles and referred to the injectable material as “oil” when providing her history. She reported that she had injected the material into the bilateral lower eyelids, left lateral lip, and left lateral chin. Three days later, she developed tingling and itching with swelling and redness at the injection sites. The patient was evaluated by the emergency department team and was prescribed a 10-day course of clindamycin empirically for suspected facial cellulitis.

The patient returned to the emergency department 12 days later upon completion of the antibiotic course with worsening edema and erythema. Examination revealed indurated, erythematous, and edematous warm plaques on the face that were concentrated around the prior injection sites with substantial periorbital erythema and edema (Figure 1). A consultation with oculoplastic surgery was obtained. Mechanical ptosis of the right eyelid was noted. Visual acuity was 20/30 in both eyes with habitual correction. Intraocular pressure was soft to palpation, and the pupils were round and reactive with no evidence of a relative afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular motility was intact bilaterally. Examination of the conjunctiva and sclera revealed bilateral conjunctival injection with chemosis of the right eye. The remainder of the anterior and posterior segment examination was within normal limits bilaterally.

Computed tomography of the face showed extensive facial and periorbital swelling without abscess. A dermatology consultation was obtained. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained from the left lower face and were sent for hematoxylin and eosin stain and tissue culture (bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacillus). Given the possibility of facial and periorbital cellulitis, empiric intravenous antibiotic therapy was initiated.

The tissue culture revealed normal skin flora. The biopsy results indicated a foreign-body reaction consistent with paraffin granuloma (Figures 2 and 3). Fite-Faraco, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and periodic acid–Schiff stains were all negative for infection. A diagnosis of foreign-body granuloma was established. Oral minocycline at a dosage of 100 mg twice daily was started, and the patient was discharged.

After 4 weeks of minocycline therapy, the patient showed no improvement and returned to the emergency department with worsening symptoms. She was readmitted and started on intravenous prednisone (1.5 mg/kg/d). Over the ensuing 5 days, the edema, erythema, conjunctival injection, and chemosis demonstrated notable improvement. She was subsequently discharged on an oral prednisone taper. Unfortunately, she did not respond to a trial of intralesional steroid injections to an area of granuloma formation on the left chin performed in the hospital before she was discharged.

In the ensuing months, she began to develop cicatricial ectropion of the right lower eyelid and mechanical ptosis of the right upper eyelid. Ten months after initial self-injection, staged surgical excision was initiated by an oculoplastic surgeon (I.V.) with the goal of debulking the periorbital region to correct the ectropion and mechanical ptosis. A transconjunctival approach was used to carefully excise the material while still maintaining the architecture of the lower eyelid. The ectropion was surgically corrected concurrently.

One month after excision, serial injections of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg/mL were administered to the right lower eyelid and anterior orbit for 3 months. Fifteen weeks after the first surgery, a second surgery was performed to address residual medial right lower eyelid induration, right upper eyelid mechanical ptosis, and left orbital inflammation. During the postoperative period, serial monthly injections of 5-FU and triamcinolone acetonide were again performed beginning at the first postoperative month.

The surgical excisions resulted in notable improvement 3 months following excision (Figure 4). The patient noted improved ocular surface comfort with decreased foreign-body sensation and tearing. She also was pleased with the improved cosmetic outcome.

Crude substances such as paraffin, petroleum jelly, and lanolin were used for aesthetic purposes in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, initially with satisfying results; however, long-term adverse effects such as hardening of the skin, swelling, granuloma formation, ulceration, infections, and abscesses have discouraged its use by medical professionals today.5 Since paraffin is resistant to degradation and absorption, foreign-body reactions may occur upon injection. These reactions are characterized by replacement of normal subcutaneous tissue by cystic spaces of paraffin oil and/or calcification, similar to the appearance of Swiss cheese on histology and surrounded by various inflammatory cells and fibrous tissue.9,10

Clinically, there is an acute inflammatory phase followed by a latent phase of chronic granulomatous inflammation that can last for years.10 Our patient presented during the acute phase, with erythematous and edematous warm plaques around the eye mimicking an orbital infection.

The treatment of choice for paraffin granuloma is complete surgical excision to prevent recurrence.6,9 However, intralesional corticosteroids are preferred in the facial area, especially if complete removal is not possible.10 Intralesional corticosteroid injections inhibit fibroblast and macrophage activity as well as the deposition of collagen, leading to reduced pain and swelling in most cases.11 Additionally, combining antimitotic agents such as 5-FU with a corticosteroid might reduce the risk for cortisone skin atrophy.12 In our case, the patient did not respond to combined 5-FU with intralesional steroids and required oral corticosteroids while awaiting serial excisions.

Our case highlights several important points in the management of paraffin granuloma. First, the clinician must perform a thorough patient history, as surreptitious use of non–medical-grade fillers is more common than one might think.13 Second, the initial presentation of these patients can mimic an infectious process. Careful history, testing, and observation can aid in making the appropriate diagnosis. Finally, treatment of these patients is complex. The mainstays of therapy are systemic anti-inflammatory medications, time, and supportive care. In some cases, surgery may be required. When processes such as paraffin granulomas involve the periorbital region, particular care is required to avoid cicatricial lagophthalmos, ectropion, or retraction. Thoughtful surgical manipulation is required to avoid these complications, which indeed may occur even with the most appropriate interventions.

- Duker D, Erdmann R, Hartmann V, et al. The impact of adverse reactions to injectable filler substances on quality of life: results from the Berlin Injectable Filler Safety (IFS)—study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1013-1020.

- Prado G, Rodriguez-Feliz J. Ocular pain and impending blindness during facial cosmetic injections: is your office prepared? [published online December 28, 2016]. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:199-203.

- Roberts SA, Arthurs BP. Severe visual loss and orbital infarction following periorbital aesthetic poly-(L)-lactic acid (PLLA) injection. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28:E68-E70.

- Cassuto D, Pignatti M, Pacchioni L, et al. Management of complications caused by permanent fillers in the face: a treatment algorithm. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:215E-227E.

- Haneke E. Adverse effects of fillers and their histopathology. Facial Plast Surg. 2014;30:599-614.

- Friedrich RE, Zustin J. Paraffinoma of lips and oral mucosa: case report and brief review of literature. GMS Interdiscip Plast Reconstr Surg DGPW. 2014;3:Doc05.

- Matton G, Anseeuw A, De Keyser F. The history of injectable biomaterials and the biology of collagen. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1985;9:133-140.

- Glicenstein J. Les premiers fillers, Vaseline et paraffine. du miracle a la catastrope. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2007;52:157-161.

- Cohen JL, Keoleian CM, Krull EA. Penile paraffinoma: self-injection with mineral oil. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;47:S251-S253.

- Legaspi-Vicerra ME, Field LM. Paraffin granulomata, “witch’s chin,” and nasal deformities excision and reconstruction with reduction chinplasty and open rhinotomy resection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2010;3:54-58.

- Carlos-Fabuel L, Marzal-Gamarra C, Marti-Alamo S, et al. Foreign body granulomatous reactions to cosmetic fillers. J Clin Exp Dent. 2012;4:E244-E247.

- Lemperle G, Gauthier-Hazan N. Foreign body granulomas after all injectable dermal fillers: part 2. treatment options. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1864-1873.

- Seok J, Hong JY, Park KY, et al. Delayed immunologic complications due to injectable fillers by unlicensed practitioners: our experiences and a review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:41-44.

- Duker D, Erdmann R, Hartmann V, et al. The impact of adverse reactions to injectable filler substances on quality of life: results from the Berlin Injectable Filler Safety (IFS)—study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1013-1020.

- Prado G, Rodriguez-Feliz J. Ocular pain and impending blindness during facial cosmetic injections: is your office prepared? [published online December 28, 2016]. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:199-203.

- Roberts SA, Arthurs BP. Severe visual loss and orbital infarction following periorbital aesthetic poly-(L)-lactic acid (PLLA) injection. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28:E68-E70.

- Cassuto D, Pignatti M, Pacchioni L, et al. Management of complications caused by permanent fillers in the face: a treatment algorithm. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:215E-227E.

- Haneke E. Adverse effects of fillers and their histopathology. Facial Plast Surg. 2014;30:599-614.

- Friedrich RE, Zustin J. Paraffinoma of lips and oral mucosa: case report and brief review of literature. GMS Interdiscip Plast Reconstr Surg DGPW. 2014;3:Doc05.

- Matton G, Anseeuw A, De Keyser F. The history of injectable biomaterials and the biology of collagen. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1985;9:133-140.

- Glicenstein J. Les premiers fillers, Vaseline et paraffine. du miracle a la catastrope. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2007;52:157-161.

- Cohen JL, Keoleian CM, Krull EA. Penile paraffinoma: self-injection with mineral oil. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;47:S251-S253.

- Legaspi-Vicerra ME, Field LM. Paraffin granulomata, “witch’s chin,” and nasal deformities excision and reconstruction with reduction chinplasty and open rhinotomy resection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2010;3:54-58.

- Carlos-Fabuel L, Marzal-Gamarra C, Marti-Alamo S, et al. Foreign body granulomatous reactions to cosmetic fillers. J Clin Exp Dent. 2012;4:E244-E247.

- Lemperle G, Gauthier-Hazan N. Foreign body granulomas after all injectable dermal fillers: part 2. treatment options. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1864-1873.

- Seok J, Hong JY, Park KY, et al. Delayed immunologic complications due to injectable fillers by unlicensed practitioners: our experiences and a review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:41-44.

Practice Points

- The initial presentation of a foreign-body granulomatous process in a patient with surreptitious use of nonmedical filler can mimic infection; thus, careful history and diagnostic measures are paramount.

- Treatment of paraffin oil granuloma can be multifactorial and involves supportive care, systemic anti-inflammatory medications, time, and surgery.

- When a paraffin granuloma involves the orbital region, particular care is required to avoid long-term complications including cicatricial lagophthalmos, ectropion, or retractions, which can be mitigated with the help of oculoplastic surgery.

A teen presents with a severe, tender rash on the extremities

“There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me; we may call it herb of grace o’ Sundays. O, you must wear your rue with a difference.”

— Ophelia in Hamlet by William Shakespeare

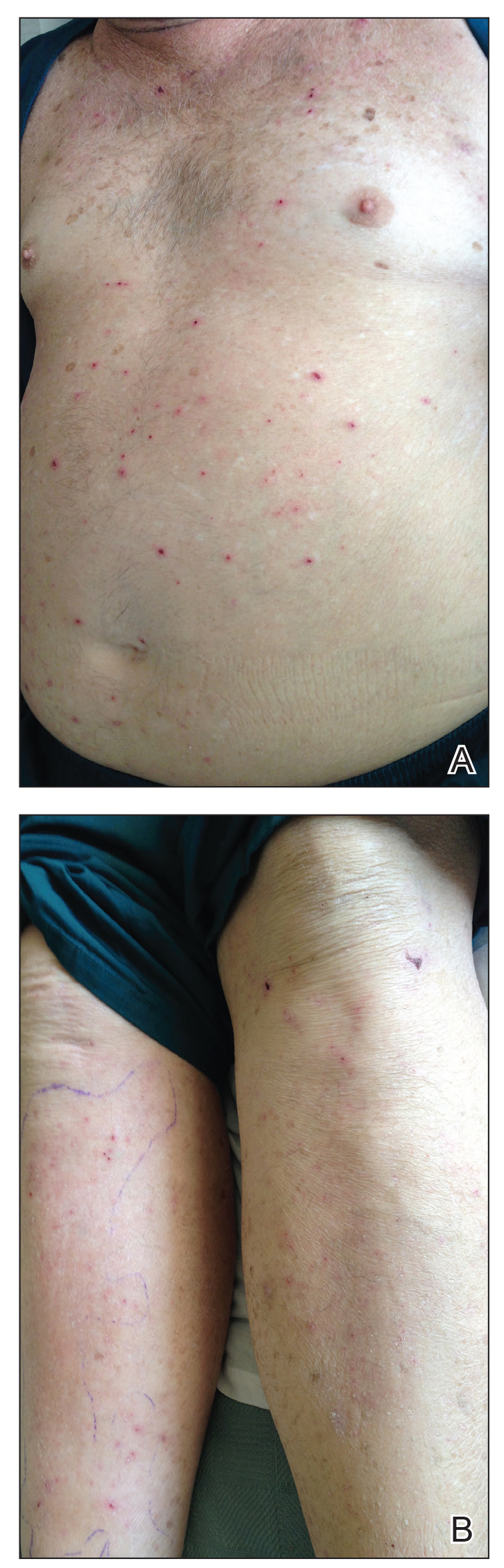

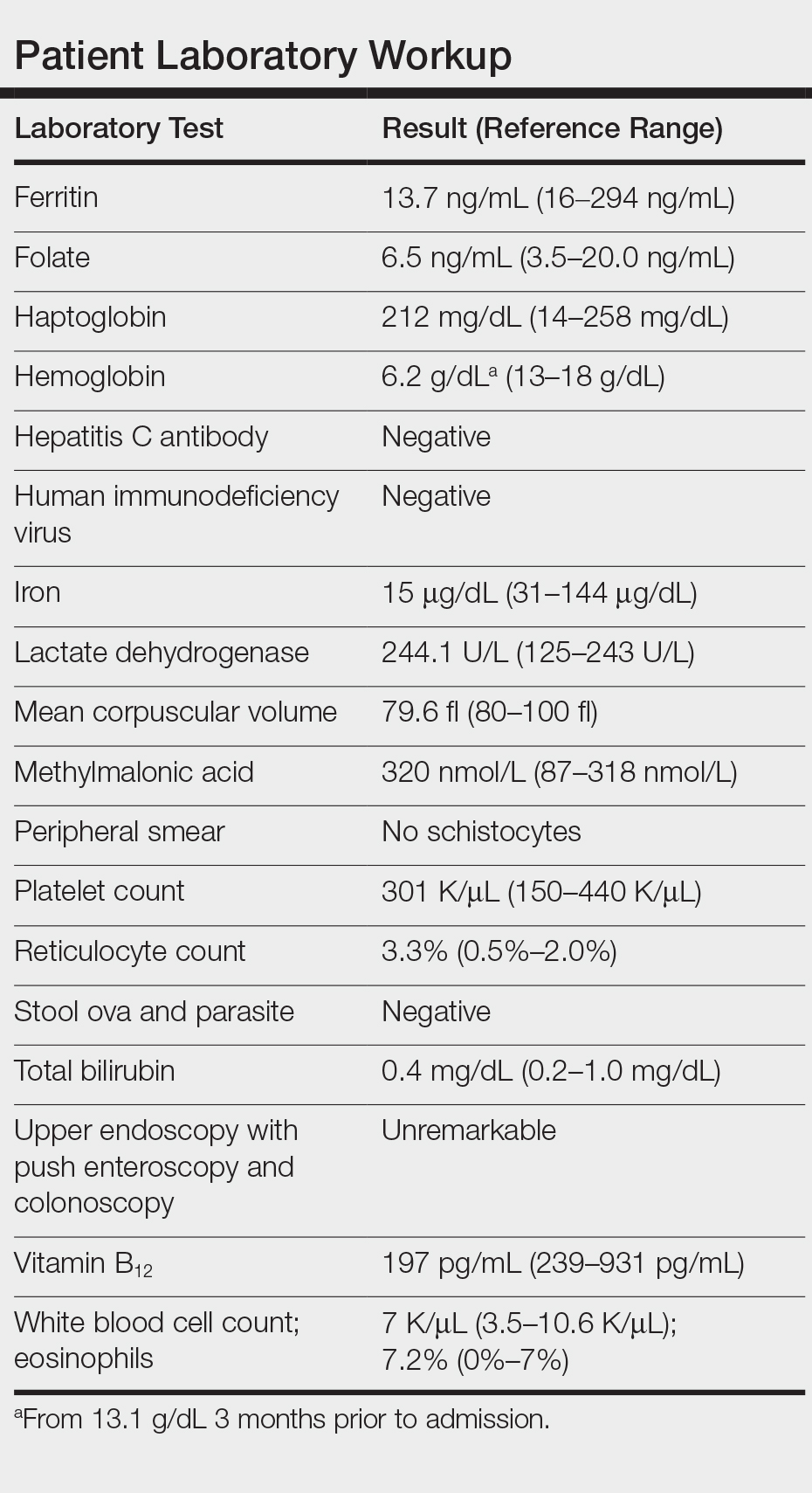

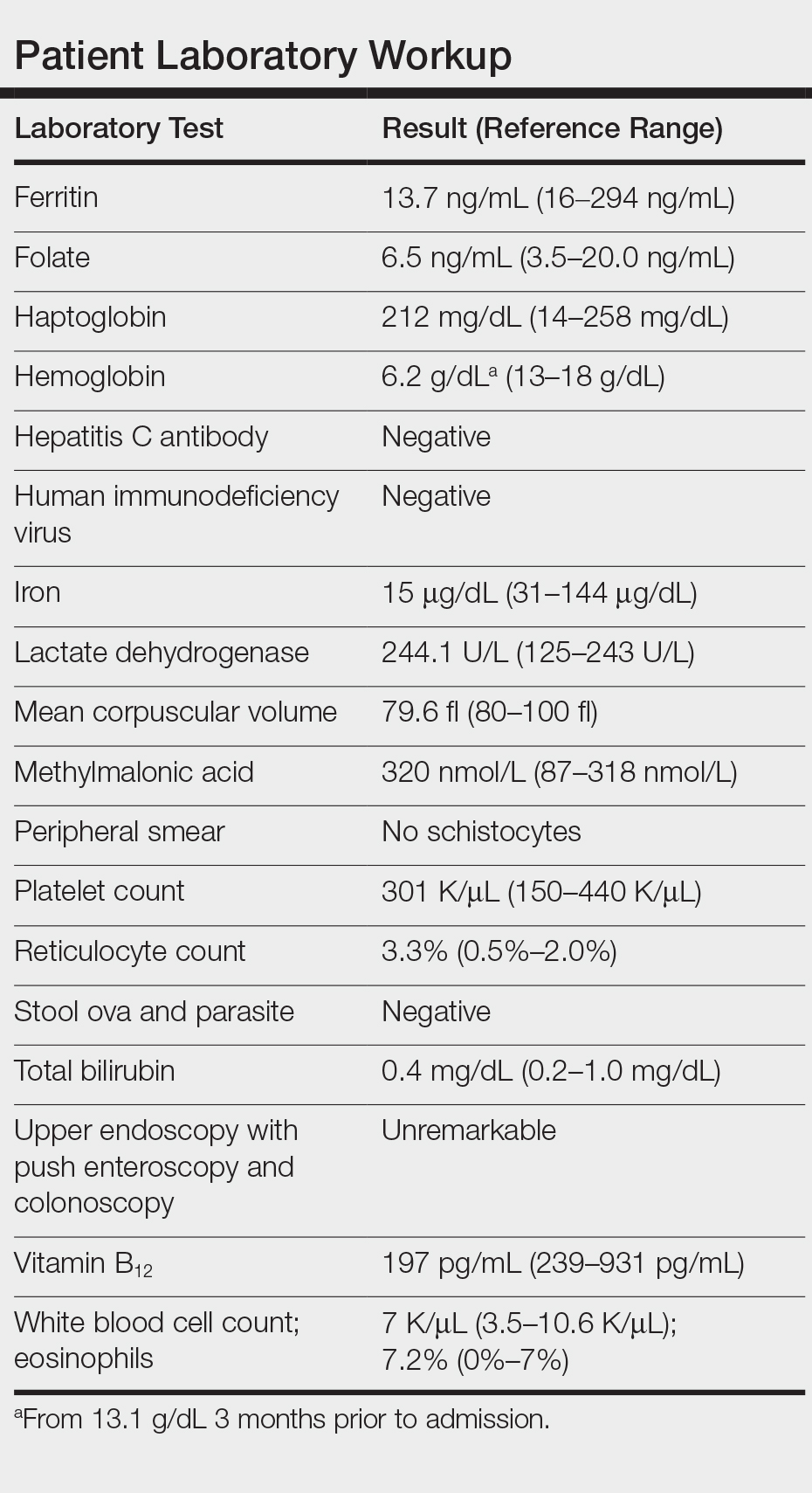

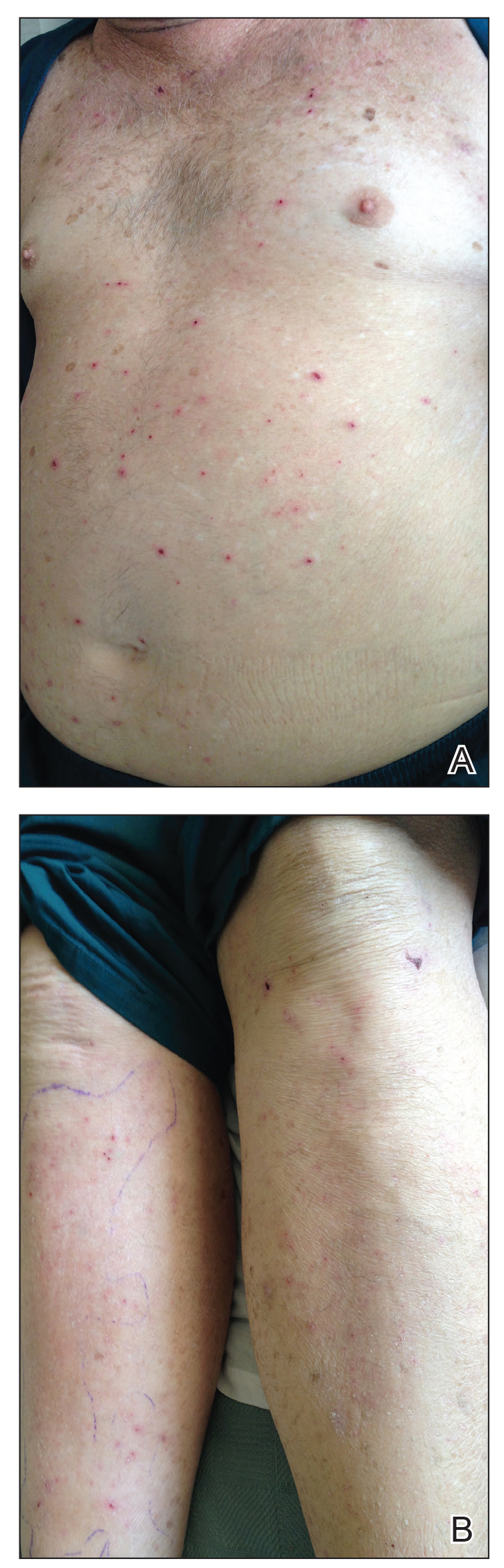

The patient was admitted to the hospital for IV fluids, pain control, and observation. The following day she admitted using the leaves of a plant on the trail as a bug repellent, as one time was taught by her grandfather. She rubbed some of the leaves on the brother as well. The grandfather shared some pictures of the bushes, and the plant was identified as Ruta graveolens.

The blisters were deroofed, cleaned with saline, and wrapped with triamcinolone ointment and petrolatum. The patient was also started on a prednisone taper and received analgesics for the severe pain.

Ruta graveolens also known as common rue or herb of grace, is an ornamental plant from the Rutaceae family. This plant is also used as a medicinal herb, condiment, and as an insect repellent. If ingested in large doses, it can cause severe abdominal pain and vomiting. It also can be hepatotoxic.

The herb contains furocumarines, such as 8-methoxypsoralen and 5-methoxypsoralen and furoquinoline alkaloids. These chemicals when exposed to UVA radiation cause cell injury and inflammation of the skin. This is considered a phototoxic reaction of the skin, compared with allergic reactions, such as poison ivy dermatitis, which need a prior sensitization to the allergen for the T cells to be activated and cause injury in the skin. Other common plants and fruits that can cause phytophotodermatitis include citrus fruits, figs, carrots, celery, parsnips, parsley, and other wildflowers like hogweed.

Depending on the degree of injury, the patients can be treated with topical corticosteroids, petrolatum wraps, and pain control. In severe cases like our patient, systemic prednisone may help stop the progression of the lesions and help with the inflammation. Skin hyperpigmentation after the initial injury may take months to clear, and some patient can develop scars.

The differential diagnosis should include severe bullous contact dermatitis like exposure to urushiol in poison ivy; second- and third-degree burns; severe medications reactions such Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis, and inmunobullous diseases such as bullous lupus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, or bullous pemphigoid. If there is no history of exposure or there are any other systemic symptoms, consider performing a skin biopsy of one of the lesions.

In this patient’s case, the history of exposure and skin findings helped the dermatologist on call make the right diagnosis.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

J Burn Care Res. 2018 Oct 23;39(6):1064-6.

Dermatitis. 2007 Mar;18(1):52-5.

BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Dec 23;2015:bcr2015213388.

“There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me; we may call it herb of grace o’ Sundays. O, you must wear your rue with a difference.”

— Ophelia in Hamlet by William Shakespeare

The patient was admitted to the hospital for IV fluids, pain control, and observation. The following day she admitted using the leaves of a plant on the trail as a bug repellent, as one time was taught by her grandfather. She rubbed some of the leaves on the brother as well. The grandfather shared some pictures of the bushes, and the plant was identified as Ruta graveolens.

The blisters were deroofed, cleaned with saline, and wrapped with triamcinolone ointment and petrolatum. The patient was also started on a prednisone taper and received analgesics for the severe pain.

Ruta graveolens also known as common rue or herb of grace, is an ornamental plant from the Rutaceae family. This plant is also used as a medicinal herb, condiment, and as an insect repellent. If ingested in large doses, it can cause severe abdominal pain and vomiting. It also can be hepatotoxic.

The herb contains furocumarines, such as 8-methoxypsoralen and 5-methoxypsoralen and furoquinoline alkaloids. These chemicals when exposed to UVA radiation cause cell injury and inflammation of the skin. This is considered a phototoxic reaction of the skin, compared with allergic reactions, such as poison ivy dermatitis, which need a prior sensitization to the allergen for the T cells to be activated and cause injury in the skin. Other common plants and fruits that can cause phytophotodermatitis include citrus fruits, figs, carrots, celery, parsnips, parsley, and other wildflowers like hogweed.

Depending on the degree of injury, the patients can be treated with topical corticosteroids, petrolatum wraps, and pain control. In severe cases like our patient, systemic prednisone may help stop the progression of the lesions and help with the inflammation. Skin hyperpigmentation after the initial injury may take months to clear, and some patient can develop scars.

The differential diagnosis should include severe bullous contact dermatitis like exposure to urushiol in poison ivy; second- and third-degree burns; severe medications reactions such Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis, and inmunobullous diseases such as bullous lupus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, or bullous pemphigoid. If there is no history of exposure or there are any other systemic symptoms, consider performing a skin biopsy of one of the lesions.

In this patient’s case, the history of exposure and skin findings helped the dermatologist on call make the right diagnosis.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

J Burn Care Res. 2018 Oct 23;39(6):1064-6.

Dermatitis. 2007 Mar;18(1):52-5.

BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Dec 23;2015:bcr2015213388.

“There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me; we may call it herb of grace o’ Sundays. O, you must wear your rue with a difference.”

— Ophelia in Hamlet by William Shakespeare

The patient was admitted to the hospital for IV fluids, pain control, and observation. The following day she admitted using the leaves of a plant on the trail as a bug repellent, as one time was taught by her grandfather. She rubbed some of the leaves on the brother as well. The grandfather shared some pictures of the bushes, and the plant was identified as Ruta graveolens.

The blisters were deroofed, cleaned with saline, and wrapped with triamcinolone ointment and petrolatum. The patient was also started on a prednisone taper and received analgesics for the severe pain.

Ruta graveolens also known as common rue or herb of grace, is an ornamental plant from the Rutaceae family. This plant is also used as a medicinal herb, condiment, and as an insect repellent. If ingested in large doses, it can cause severe abdominal pain and vomiting. It also can be hepatotoxic.

The herb contains furocumarines, such as 8-methoxypsoralen and 5-methoxypsoralen and furoquinoline alkaloids. These chemicals when exposed to UVA radiation cause cell injury and inflammation of the skin. This is considered a phototoxic reaction of the skin, compared with allergic reactions, such as poison ivy dermatitis, which need a prior sensitization to the allergen for the T cells to be activated and cause injury in the skin. Other common plants and fruits that can cause phytophotodermatitis include citrus fruits, figs, carrots, celery, parsnips, parsley, and other wildflowers like hogweed.

Depending on the degree of injury, the patients can be treated with topical corticosteroids, petrolatum wraps, and pain control. In severe cases like our patient, systemic prednisone may help stop the progression of the lesions and help with the inflammation. Skin hyperpigmentation after the initial injury may take months to clear, and some patient can develop scars.

The differential diagnosis should include severe bullous contact dermatitis like exposure to urushiol in poison ivy; second- and third-degree burns; severe medications reactions such Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis, and inmunobullous diseases such as bullous lupus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, or bullous pemphigoid. If there is no history of exposure or there are any other systemic symptoms, consider performing a skin biopsy of one of the lesions.

In this patient’s case, the history of exposure and skin findings helped the dermatologist on call make the right diagnosis.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

J Burn Care Res. 2018 Oct 23;39(6):1064-6.

Dermatitis. 2007 Mar;18(1):52-5.

BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Dec 23;2015:bcr2015213388.

She started taking lithium for depression and anxiety 3 weeks prior to her developing the rash. She denies taking any other medications, supplements, or recreational drugs.

She denied any prior history of photosensitivity, no history of mouth ulcers, joint pain, muscle weakness, hair loss, or any other symptoms.

Besides her brother, there are no other affected family members, and no history of immune bullous disorders or other skin conditions.

On physical exam, the girl appears in a lot of pain and is uncomfortable. The skin is red and hot, and there are tense bullae on the neck, arms, and legs. There are no ocular or mucosal lesions.

Patch Testing 101, Part 1: Performing the Test

Our apologies, dear reader. It seems we have gotten ahead of ourselves. While we were writing about the Allergen of the Year, systemic dermatitis, and patch testing in children, we forgot to start with the basics. Let us remedy that. This is the first of a 2-part series addressing the basics of patch testing. In this article, we examine patch test systems, allergens, patch test readings, testing while on medications, and patch testing pearls and pitfalls. Let us begin!

Patch Test Systems

There are 2 patch test systems in North America: the Thin-layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test (SmartPractice), which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for those 6 years and older, and the chamber method.

The T.R.U.E. test consists of 3 panels with 35 allergens and 1 negative control. The T.R.U.E. package insert1 describes surgical tape with individual polyester patches, each coated with an allergen film. Benefits of T.R.U.E. include ease of use (ie, easy storage and preparation, quick and straightforward application) and a readily identifiable set of allergens. The main drawback of T.R.U.E. is that only a limited number of allergens are tested, and as a result, it may miss the identification of some contact allergies. In an analysis of the 2015-2016 North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) patch test screening series, 25% to 40% of positive patch tests would have been missed if patch testing was performed with T.R.U.E. alone.2

Chamber method patch testing describes the process by which allergens are loaded into either metal or plastic chambers and then applied to the patient’s skin. The major benefit of the chamber method is that patches may be truly customized for the patient. The chamber method is time and labor intensive for patch preparation and application. Most comprehensive patch test clinics in North America use the chamber method, including the NACDG.

Patch test chambers largely can be divided into 2 categories: metal (aluminum) or plastic. Aluminum chambers, also known as Finn chambers, traditionally are used in patch testing. There are rare reports of hypersensitivity to aluminum chambers with associated diffuse positive patch test reactions,3,4 which may be more common in the pediatric population and likely is due to the fact that aluminum is present as an adjuvant in many childhood vaccines. As a precaution, some patch text experts recommend using plastic chambers in children younger than 16 to 18 years (M.R. and A.R.A., personal communication). Metal chambers require the additional application of diffusion discs for liquid allergens, and plastic chambers typically already contain the necessary diffusion discs. Finn chambers traditionally are applied with hypoallergenic porous surgical tape, but a waterproof tape also is available. To keep the chambers in place for the necessary 48 hours, additional tape may be applied over the patches.

Allergens

In patch test clinics, many dermatologists use a standard or screening allergen series. An appropriate standard series encompasses allergens that are most likely to be positive and relevant in the tested population. Some patch test experts recommend that allergens with a positive patch test frequency of greater than 0.5% to 1% should be included in a standard series.5 However, geographic differences in positive reactions can influence which allergens are appropriate to include. As a result, there is no universal standard series. Examples of standard or screening series include the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) allergen series,6 North American Baseline Series or North American 80 Comprehensive Series, European Baseline Series, NACDG series,2 and the Pediatric Baseline Series,7 as well as many other country- or region-specific series. There currently are 2 major commercial allergen distribution companies—Chemotechnique Diagnostics/Dormer Laboratories (series, individual allergens) and SmartPractice/allerGEAZE (series, individual allergens, T.R.U.E.).

In addition to a properly selected standard or screening series, supplemental patch testing with additional allergens can increase the diagnostic yield. Numerous supplemental series exist, including cosmetic, dental, textile, rubber, adhesive, plastics, and glue, among many others. In the NACDG 2015-2016 patch test cycle, it was found that 23% of 5597 patients reacted to an allergen that was not present on the NACDG screening series.2

In some situations, it is appropriate to patch test patient products, or nonstandard allergens. An abundance of caution, understanding of patch testing, and experience is necessary; for example, some chemicals are not recommended for testing, such as cleaning products, certain industrial chemicals, and those that may be carcinogens. We frequently consult De Groot’s Patch Testing8 for recommended allergen test concentrations and vehicles.

Patch Test Readings

The timing of the patch test reading is an important component of the test. Most North American comprehensive patch test clinics perform both first and delayed readings. After application, patches remain in place for 48 hours and then are removed, and a first reading is completed. Results are recorded as +/− (weak/doubtful), + (mild), ++ (strong), +++ (very strong), irritant, and negative.2 Many patch test specialists use side lighting to achieve the best reading and palpate to confirm the presence of induration; panel alignment devices commonly are utilized. There are some scenarios where shorter or longer application times are indicated, but this is beyond the scope of this article. A second, or delayed, reading should be completed 72 to 144 hours after initial application. We usually complete the delayed reading at 96 to 120 hours.

Certain patch test reactions may peak at different times, with fragrances often reacting earlier, and metals, topical antibiotics, and textile dyes reacting later.9 In the scenario of delayed peak reactions, third readings may be indicated.

Neglecting to complete a delayed reading is a potential pitfall and can increase the risk for both false-positive and false-negative reactions.10,11 In 1996, Uter et al10 published a large study of 9946 patients who were patch tested over a 4-year period. The authors compared patch test reactions at 48 and 72 hours and found that 34.5% of all positive reactions occurred at 72 hours; an additional 15.1% were positive at 96 hours. Importantly, one reading at 48 hours missed approximately one-third of positive patch test reactions, emphasizing the importance of delayed patch test readings.10 Furthermore, another study of 9997 consecutively patch tested patients examined reactions that were either negative or doubtful between days 3 or 4 and followed to see which of those reactions were positive at days 6 or 7. Of the negative reactions, the authors found that 4.4% were positive on days 6 or 7, and of the doubtful reactions, 9.1% were positive on days 6 or 7, meaning that up to 13.5% of positive reactions can be missed when a later reading is not performed.11

Medications During Patch Testing

Topical Medications

Topical medications generally can be continued during patch testing; however, patients should not apply topical medications to the patch test application site. Ideally, there should be no topical medication applied to the patch test application site for 1 to 2 weeks prior to patch test placement.12 Use of topical medications such as corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and theoretically even phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors can not only result in suppression of positive patch test reactions but also can make patch adherence difficult.

Phototherapy

Phototherapy can result in local cutaneous immune suppression; therefore, it is recommended that it not be applied to the patch test area either during the patch test process or for 1 to 2 weeks prior to patch test application. In addition, if heat or sweating are generated during phototherapy, they can affect the success of patch testing by poor patch adherence and/or disruption of allergen distribution.

Systemic Medications

Oral antihistamines do not affect patch testing and can be continued during the patch test process.

It is ideal to avoid systemic immunomodulatory agents during the patch test process, but they occasionally are unavoidable, either because they are necessary to manage other medical conditions or because they are needed to achieve clear enough skin to proceed with patch testing. If it is required, prednisone is not recommended to exceed 10 mg daily.12,13 If intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide has been administered, patch testing should occur at least 1 month after the most recent injection.12 Oral methotrexate can probably be continued during patch testing but should be kept at the lowest possible dose and should be held during the week of testing, if possible. Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and ustekinumab can be continued, as they are unlikely to interfere with patch testing.12 There are reports of positive patch test reactions on dupilumab,14,15 and some authors have described the response as variable and potentially allergen dependent.16,17 We believe that it generally is acceptable to continue dupilumab during patch testing. Data on cyclosporine during patch testing are mixed, and caution is advised as higher doses may suppress a positive patch test. Azathioprine and mycophenolate should be avoided, if possible.12

Pearls and Pitfalls

A few tips along the way can help assure your success in patch testing.

- Proper patient counseling determines a successful test. Provide your patient with verbal and written instructions about the patch test process, patch care, and any other necessary information.

- A simple sponge bath is permissible during patch testing provided the back stays dry. One of the authors (A.R.A.) advises patients to sit in a small amount of water in a bathtub to bathe, wash only the front of the body in the shower, and wash hair in the sink.

- No sweating, swimming, heavy exercise, or heavy physical labor. If your patient is planning to run a marathon the week of patch testing, they will be sorely disappointed when you tell them no sweating or showering is allowed! Patients with an occupation that requires physical labor may require a work excuse.

- Tape does not adhere to areas of the skin with excess hair. A scissor trim or electric shave will help the patches stay occluded and in place. We use an electric razor with a disposable replaceable head. A traditional straight razor should not be used, as it can increase the risk for folliculitis, which can make patch readings quite difficult.

- Securing the patches in place with an extra layer of tape provides added security. Large sheets of transparent medical dressings work particularly well for children or if there is difficulty with tape adherence.

Avoid application of patches to areas of the skin with tattoos. In theory, tattooed skin may have a decreased immune response, and tattoo pigment can obscure results.18 However, this is sometimes unavoidable, and Fowler and McTigue18 described a case of successful patch testing on a diffusely tattooed back.

- Avoid skin lesions (eg, scars, seborrheic keratoses, dermatitis) that can affect tape application, patch adherence, or patch readings.

Final Interpretation

The first step to excellent patch testing is understanding the patch test process. Patch test systems include T.R.U.E. and the chamber method. There are several allergen screening series, and the best series for each patient is determined based on geographic region, exposures, and allergen prevalence. The timing and practice of the patch test reading is vital, and physicians should be cognizant of medications and phototherapy use during the patch test process. An understanding of common pearls and pitfalls makes the difference between a good and great patch tester.

Now that you are an expert in performing the test, watch out for part 2 of this series on patch test interpretation, relevance, education, and counseling. Happy testing!

- T.R.U.E TEST [package insert]. Phoenix, AZ: SmartPractice; 1994.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Zug KA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2015-2016. Dermatitis. 2018;29:297-309.

- Ward JM, Walsh RK, Bellet JS, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to aluminum-based chambers during routine patch testing. Paper presented at: American Contact Dermatitis Society Annual Meeting; March 19, 2020; Denver, CO.

- Deleuran MG, Ahlström MG, Zachariae C, et al. Patch test reactivity to aluminum chambers. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:318-319.

- Bruze M, Condé-Salazar L, Goossens A, et al. European Society of Contact Dermatitis. thoughts on sensitizers in a standard patch test series. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:241-250.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2017 update. Dermatitis. 2017;28:141-143.

- Yu J, Atwater AR, Brod B, et al. Pediatric baseline patch test series: Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Workgroup. Dermatitis. 2018;29:206-212.

- De Groot AC. Patch Testing: Test Concentrations and Vehicles for 4900 Chemicals. 4th ed. Wapserveen, The Netherlands: Acdegroot Publishing; 2018.

- Chaudhry HM, Drage LA, El-Azhary RA, et al. Delayed patch-test reading after 5 days: an update from the Mayo Clinic Contact Dermatitis Group. Dermatitis. 2017;28:253-260.

- Uter WJ, Geier J, Schnuch A. Good clinical practice in patch testing: readings beyond day 2 are necessary: a confirmatory analysis. Members of the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology. Am J Contact Dermat. 1996;7:231-237.

- Madsen JT, Andersen KE. Outcome of a second patch test reading of T.R.U.E. Tests® on D6/7. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:94-97.

- Lampel H, Atwater AR. Patch testing tools of the trade: use of immunosuppressants and antihistamines during patch testing. J Dermatol Nurses’ Assoc. 2016;8:209-211.

- Fowler JF, Maibach HI, Zirwas M, et al. Effects of immunomodulatory agents on patch testing: expert opinion 2012. Dermatitis. 2012;23:301-303.

- Puza CJ, Atwater AR. Positive patch test reaction in a patient taking dupilumab. Dermatitis. 2018;29:89.

- Hoot JW, Douglas JD, Falo LD. Patch testing in a patient on dupilumab. Dermatitis. 2018;29:164.

- Stout M, Silverberg JI. Variable impact of dupilumab on patch testing results and allergic contact dermatitis in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:157-162.

- Raffi J, Botto N. Patch testing and allergen-specific inhibition in a patient taking dupilumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:120-121.

- Fowler JF, McTigue MK. Patch testing over tattoos. Am J Contact Dermat. 2002;13:19-20.

Our apologies, dear reader. It seems we have gotten ahead of ourselves. While we were writing about the Allergen of the Year, systemic dermatitis, and patch testing in children, we forgot to start with the basics. Let us remedy that. This is the first of a 2-part series addressing the basics of patch testing. In this article, we examine patch test systems, allergens, patch test readings, testing while on medications, and patch testing pearls and pitfalls. Let us begin!

Patch Test Systems

There are 2 patch test systems in North America: the Thin-layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test (SmartPractice), which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for those 6 years and older, and the chamber method.

The T.R.U.E. test consists of 3 panels with 35 allergens and 1 negative control. The T.R.U.E. package insert1 describes surgical tape with individual polyester patches, each coated with an allergen film. Benefits of T.R.U.E. include ease of use (ie, easy storage and preparation, quick and straightforward application) and a readily identifiable set of allergens. The main drawback of T.R.U.E. is that only a limited number of allergens are tested, and as a result, it may miss the identification of some contact allergies. In an analysis of the 2015-2016 North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) patch test screening series, 25% to 40% of positive patch tests would have been missed if patch testing was performed with T.R.U.E. alone.2

Chamber method patch testing describes the process by which allergens are loaded into either metal or plastic chambers and then applied to the patient’s skin. The major benefit of the chamber method is that patches may be truly customized for the patient. The chamber method is time and labor intensive for patch preparation and application. Most comprehensive patch test clinics in North America use the chamber method, including the NACDG.

Patch test chambers largely can be divided into 2 categories: metal (aluminum) or plastic. Aluminum chambers, also known as Finn chambers, traditionally are used in patch testing. There are rare reports of hypersensitivity to aluminum chambers with associated diffuse positive patch test reactions,3,4 which may be more common in the pediatric population and likely is due to the fact that aluminum is present as an adjuvant in many childhood vaccines. As a precaution, some patch text experts recommend using plastic chambers in children younger than 16 to 18 years (M.R. and A.R.A., personal communication). Metal chambers require the additional application of diffusion discs for liquid allergens, and plastic chambers typically already contain the necessary diffusion discs. Finn chambers traditionally are applied with hypoallergenic porous surgical tape, but a waterproof tape also is available. To keep the chambers in place for the necessary 48 hours, additional tape may be applied over the patches.

Allergens

In patch test clinics, many dermatologists use a standard or screening allergen series. An appropriate standard series encompasses allergens that are most likely to be positive and relevant in the tested population. Some patch test experts recommend that allergens with a positive patch test frequency of greater than 0.5% to 1% should be included in a standard series.5 However, geographic differences in positive reactions can influence which allergens are appropriate to include. As a result, there is no universal standard series. Examples of standard or screening series include the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) allergen series,6 North American Baseline Series or North American 80 Comprehensive Series, European Baseline Series, NACDG series,2 and the Pediatric Baseline Series,7 as well as many other country- or region-specific series. There currently are 2 major commercial allergen distribution companies—Chemotechnique Diagnostics/Dormer Laboratories (series, individual allergens) and SmartPractice/allerGEAZE (series, individual allergens, T.R.U.E.).

In addition to a properly selected standard or screening series, supplemental patch testing with additional allergens can increase the diagnostic yield. Numerous supplemental series exist, including cosmetic, dental, textile, rubber, adhesive, plastics, and glue, among many others. In the NACDG 2015-2016 patch test cycle, it was found that 23% of 5597 patients reacted to an allergen that was not present on the NACDG screening series.2

In some situations, it is appropriate to patch test patient products, or nonstandard allergens. An abundance of caution, understanding of patch testing, and experience is necessary; for example, some chemicals are not recommended for testing, such as cleaning products, certain industrial chemicals, and those that may be carcinogens. We frequently consult De Groot’s Patch Testing8 for recommended allergen test concentrations and vehicles.

Patch Test Readings

The timing of the patch test reading is an important component of the test. Most North American comprehensive patch test clinics perform both first and delayed readings. After application, patches remain in place for 48 hours and then are removed, and a first reading is completed. Results are recorded as +/− (weak/doubtful), + (mild), ++ (strong), +++ (very strong), irritant, and negative.2 Many patch test specialists use side lighting to achieve the best reading and palpate to confirm the presence of induration; panel alignment devices commonly are utilized. There are some scenarios where shorter or longer application times are indicated, but this is beyond the scope of this article. A second, or delayed, reading should be completed 72 to 144 hours after initial application. We usually complete the delayed reading at 96 to 120 hours.

Certain patch test reactions may peak at different times, with fragrances often reacting earlier, and metals, topical antibiotics, and textile dyes reacting later.9 In the scenario of delayed peak reactions, third readings may be indicated.

Neglecting to complete a delayed reading is a potential pitfall and can increase the risk for both false-positive and false-negative reactions.10,11 In 1996, Uter et al10 published a large study of 9946 patients who were patch tested over a 4-year period. The authors compared patch test reactions at 48 and 72 hours and found that 34.5% of all positive reactions occurred at 72 hours; an additional 15.1% were positive at 96 hours. Importantly, one reading at 48 hours missed approximately one-third of positive patch test reactions, emphasizing the importance of delayed patch test readings.10 Furthermore, another study of 9997 consecutively patch tested patients examined reactions that were either negative or doubtful between days 3 or 4 and followed to see which of those reactions were positive at days 6 or 7. Of the negative reactions, the authors found that 4.4% were positive on days 6 or 7, and of the doubtful reactions, 9.1% were positive on days 6 or 7, meaning that up to 13.5% of positive reactions can be missed when a later reading is not performed.11

Medications During Patch Testing

Topical Medications

Topical medications generally can be continued during patch testing; however, patients should not apply topical medications to the patch test application site. Ideally, there should be no topical medication applied to the patch test application site for 1 to 2 weeks prior to patch test placement.12 Use of topical medications such as corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and theoretically even phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors can not only result in suppression of positive patch test reactions but also can make patch adherence difficult.

Phototherapy

Phototherapy can result in local cutaneous immune suppression; therefore, it is recommended that it not be applied to the patch test area either during the patch test process or for 1 to 2 weeks prior to patch test application. In addition, if heat or sweating are generated during phototherapy, they can affect the success of patch testing by poor patch adherence and/or disruption of allergen distribution.

Systemic Medications

Oral antihistamines do not affect patch testing and can be continued during the patch test process.

It is ideal to avoid systemic immunomodulatory agents during the patch test process, but they occasionally are unavoidable, either because they are necessary to manage other medical conditions or because they are needed to achieve clear enough skin to proceed with patch testing. If it is required, prednisone is not recommended to exceed 10 mg daily.12,13 If intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide has been administered, patch testing should occur at least 1 month after the most recent injection.12 Oral methotrexate can probably be continued during patch testing but should be kept at the lowest possible dose and should be held during the week of testing, if possible. Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and ustekinumab can be continued, as they are unlikely to interfere with patch testing.12 There are reports of positive patch test reactions on dupilumab,14,15 and some authors have described the response as variable and potentially allergen dependent.16,17 We believe that it generally is acceptable to continue dupilumab during patch testing. Data on cyclosporine during patch testing are mixed, and caution is advised as higher doses may suppress a positive patch test. Azathioprine and mycophenolate should be avoided, if possible.12

Pearls and Pitfalls

A few tips along the way can help assure your success in patch testing.

- Proper patient counseling determines a successful test. Provide your patient with verbal and written instructions about the patch test process, patch care, and any other necessary information.

- A simple sponge bath is permissible during patch testing provided the back stays dry. One of the authors (A.R.A.) advises patients to sit in a small amount of water in a bathtub to bathe, wash only the front of the body in the shower, and wash hair in the sink.

- No sweating, swimming, heavy exercise, or heavy physical labor. If your patient is planning to run a marathon the week of patch testing, they will be sorely disappointed when you tell them no sweating or showering is allowed! Patients with an occupation that requires physical labor may require a work excuse.

- Tape does not adhere to areas of the skin with excess hair. A scissor trim or electric shave will help the patches stay occluded and in place. We use an electric razor with a disposable replaceable head. A traditional straight razor should not be used, as it can increase the risk for folliculitis, which can make patch readings quite difficult.

- Securing the patches in place with an extra layer of tape provides added security. Large sheets of transparent medical dressings work particularly well for children or if there is difficulty with tape adherence.

Avoid application of patches to areas of the skin with tattoos. In theory, tattooed skin may have a decreased immune response, and tattoo pigment can obscure results.18 However, this is sometimes unavoidable, and Fowler and McTigue18 described a case of successful patch testing on a diffusely tattooed back.

- Avoid skin lesions (eg, scars, seborrheic keratoses, dermatitis) that can affect tape application, patch adherence, or patch readings.

Final Interpretation

The first step to excellent patch testing is understanding the patch test process. Patch test systems include T.R.U.E. and the chamber method. There are several allergen screening series, and the best series for each patient is determined based on geographic region, exposures, and allergen prevalence. The timing and practice of the patch test reading is vital, and physicians should be cognizant of medications and phototherapy use during the patch test process. An understanding of common pearls and pitfalls makes the difference between a good and great patch tester.

Now that you are an expert in performing the test, watch out for part 2 of this series on patch test interpretation, relevance, education, and counseling. Happy testing!

Our apologies, dear reader. It seems we have gotten ahead of ourselves. While we were writing about the Allergen of the Year, systemic dermatitis, and patch testing in children, we forgot to start with the basics. Let us remedy that. This is the first of a 2-part series addressing the basics of patch testing. In this article, we examine patch test systems, allergens, patch test readings, testing while on medications, and patch testing pearls and pitfalls. Let us begin!

Patch Test Systems

There are 2 patch test systems in North America: the Thin-layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test (SmartPractice), which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for those 6 years and older, and the chamber method.

The T.R.U.E. test consists of 3 panels with 35 allergens and 1 negative control. The T.R.U.E. package insert1 describes surgical tape with individual polyester patches, each coated with an allergen film. Benefits of T.R.U.E. include ease of use (ie, easy storage and preparation, quick and straightforward application) and a readily identifiable set of allergens. The main drawback of T.R.U.E. is that only a limited number of allergens are tested, and as a result, it may miss the identification of some contact allergies. In an analysis of the 2015-2016 North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) patch test screening series, 25% to 40% of positive patch tests would have been missed if patch testing was performed with T.R.U.E. alone.2

Chamber method patch testing describes the process by which allergens are loaded into either metal or plastic chambers and then applied to the patient’s skin. The major benefit of the chamber method is that patches may be truly customized for the patient. The chamber method is time and labor intensive for patch preparation and application. Most comprehensive patch test clinics in North America use the chamber method, including the NACDG.

Patch test chambers largely can be divided into 2 categories: metal (aluminum) or plastic. Aluminum chambers, also known as Finn chambers, traditionally are used in patch testing. There are rare reports of hypersensitivity to aluminum chambers with associated diffuse positive patch test reactions,3,4 which may be more common in the pediatric population and likely is due to the fact that aluminum is present as an adjuvant in many childhood vaccines. As a precaution, some patch text experts recommend using plastic chambers in children younger than 16 to 18 years (M.R. and A.R.A., personal communication). Metal chambers require the additional application of diffusion discs for liquid allergens, and plastic chambers typically already contain the necessary diffusion discs. Finn chambers traditionally are applied with hypoallergenic porous surgical tape, but a waterproof tape also is available. To keep the chambers in place for the necessary 48 hours, additional tape may be applied over the patches.

Allergens

In patch test clinics, many dermatologists use a standard or screening allergen series. An appropriate standard series encompasses allergens that are most likely to be positive and relevant in the tested population. Some patch test experts recommend that allergens with a positive patch test frequency of greater than 0.5% to 1% should be included in a standard series.5 However, geographic differences in positive reactions can influence which allergens are appropriate to include. As a result, there is no universal standard series. Examples of standard or screening series include the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) allergen series,6 North American Baseline Series or North American 80 Comprehensive Series, European Baseline Series, NACDG series,2 and the Pediatric Baseline Series,7 as well as many other country- or region-specific series. There currently are 2 major commercial allergen distribution companies—Chemotechnique Diagnostics/Dormer Laboratories (series, individual allergens) and SmartPractice/allerGEAZE (series, individual allergens, T.R.U.E.).

In addition to a properly selected standard or screening series, supplemental patch testing with additional allergens can increase the diagnostic yield. Numerous supplemental series exist, including cosmetic, dental, textile, rubber, adhesive, plastics, and glue, among many others. In the NACDG 2015-2016 patch test cycle, it was found that 23% of 5597 patients reacted to an allergen that was not present on the NACDG screening series.2

In some situations, it is appropriate to patch test patient products, or nonstandard allergens. An abundance of caution, understanding of patch testing, and experience is necessary; for example, some chemicals are not recommended for testing, such as cleaning products, certain industrial chemicals, and those that may be carcinogens. We frequently consult De Groot’s Patch Testing8 for recommended allergen test concentrations and vehicles.

Patch Test Readings

The timing of the patch test reading is an important component of the test. Most North American comprehensive patch test clinics perform both first and delayed readings. After application, patches remain in place for 48 hours and then are removed, and a first reading is completed. Results are recorded as +/− (weak/doubtful), + (mild), ++ (strong), +++ (very strong), irritant, and negative.2 Many patch test specialists use side lighting to achieve the best reading and palpate to confirm the presence of induration; panel alignment devices commonly are utilized. There are some scenarios where shorter or longer application times are indicated, but this is beyond the scope of this article. A second, or delayed, reading should be completed 72 to 144 hours after initial application. We usually complete the delayed reading at 96 to 120 hours.

Certain patch test reactions may peak at different times, with fragrances often reacting earlier, and metals, topical antibiotics, and textile dyes reacting later.9 In the scenario of delayed peak reactions, third readings may be indicated.

Neglecting to complete a delayed reading is a potential pitfall and can increase the risk for both false-positive and false-negative reactions.10,11 In 1996, Uter et al10 published a large study of 9946 patients who were patch tested over a 4-year period. The authors compared patch test reactions at 48 and 72 hours and found that 34.5% of all positive reactions occurred at 72 hours; an additional 15.1% were positive at 96 hours. Importantly, one reading at 48 hours missed approximately one-third of positive patch test reactions, emphasizing the importance of delayed patch test readings.10 Furthermore, another study of 9997 consecutively patch tested patients examined reactions that were either negative or doubtful between days 3 or 4 and followed to see which of those reactions were positive at days 6 or 7. Of the negative reactions, the authors found that 4.4% were positive on days 6 or 7, and of the doubtful reactions, 9.1% were positive on days 6 or 7, meaning that up to 13.5% of positive reactions can be missed when a later reading is not performed.11

Medications During Patch Testing

Topical Medications

Topical medications generally can be continued during patch testing; however, patients should not apply topical medications to the patch test application site. Ideally, there should be no topical medication applied to the patch test application site for 1 to 2 weeks prior to patch test placement.12 Use of topical medications such as corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and theoretically even phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors can not only result in suppression of positive patch test reactions but also can make patch adherence difficult.

Phototherapy

Phototherapy can result in local cutaneous immune suppression; therefore, it is recommended that it not be applied to the patch test area either during the patch test process or for 1 to 2 weeks prior to patch test application. In addition, if heat or sweating are generated during phototherapy, they can affect the success of patch testing by poor patch adherence and/or disruption of allergen distribution.

Systemic Medications

Oral antihistamines do not affect patch testing and can be continued during the patch test process.

It is ideal to avoid systemic immunomodulatory agents during the patch test process, but they occasionally are unavoidable, either because they are necessary to manage other medical conditions or because they are needed to achieve clear enough skin to proceed with patch testing. If it is required, prednisone is not recommended to exceed 10 mg daily.12,13 If intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide has been administered, patch testing should occur at least 1 month after the most recent injection.12 Oral methotrexate can probably be continued during patch testing but should be kept at the lowest possible dose and should be held during the week of testing, if possible. Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and ustekinumab can be continued, as they are unlikely to interfere with patch testing.12 There are reports of positive patch test reactions on dupilumab,14,15 and some authors have described the response as variable and potentially allergen dependent.16,17 We believe that it generally is acceptable to continue dupilumab during patch testing. Data on cyclosporine during patch testing are mixed, and caution is advised as higher doses may suppress a positive patch test. Azathioprine and mycophenolate should be avoided, if possible.12

Pearls and Pitfalls

A few tips along the way can help assure your success in patch testing.

- Proper patient counseling determines a successful test. Provide your patient with verbal and written instructions about the patch test process, patch care, and any other necessary information.

- A simple sponge bath is permissible during patch testing provided the back stays dry. One of the authors (A.R.A.) advises patients to sit in a small amount of water in a bathtub to bathe, wash only the front of the body in the shower, and wash hair in the sink.