User login

Radiation Recall Dermatitis Triggered by Prednisone

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman presented to the allergy clinic for evaluation of a rash on the left breast. The patient had a history of breast cancer that was treated with a lumpectomy followed by external beam radiation therapy (total dose, 6000 cGy) to the lateral aspect of the left breast approximately 4 years prior. She developed acute breast dermatitis from the radiation, which was self-treated with over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream. The patient subsequently developed a blistering skin eruption over the area where she applied the cream. She did not recall the subtype of hydrocortisone she used (butyrate and acetate are available over-the-counter). She discontinued the hydrocortisone and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1%, which was well tolerated, and the rash resolved.

The patient had a history of a similar reaction to hydrocortisone butyrate after blepharoplasty approximately 10 years prior to the current presentation, characterized by facial erythema, pruritus, and blistering. A patch test confirmed reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and tixocortol pivalate. However, a skin-prick test for hydrocortisone acetate cream 1% was negative.

Subsequently, the patient developed acute-onset dyspepsia, gnawing epigastric pain, regurgitation, and bloating. A diagnosis of eosinophilic gastritis was established via biopsy, which found increased eosinophils in the lamina propria (>50 eosinophils per high-power field). Helicobacter pylori was not identified. She was started on the proton-pump inhibitor dexlansoprazole but symptoms did not improve. Her other medications included benazepril, alprazolam as needed, vitamin D, and magnesium. The patient subsequently was started on a trial of oral prednisone 40 mg/d. Three days after initiation, she developed an erythematous macular rash over the left breast.

The next day she presented to the allergy clinic. Physical examination of the left breast revealed a 20×10-cm, nipple-sparing patch of well-demarcated erythema without fluctuance or overlying lesions. The area of erythema overlapped with the prior radiation field based on radiation marker tattoos and the lumpectomy scar (Figure). There was no evidence to suggest inflammation of deeper tissue or the pectoral muscles. Vital signs were normal, and the remainder of the examination was unremarkable, including breast, lymph node, and complete skin examinations.

At evaluation, the differential diagnosis included contact dermatitis, fixed drug eruption, infection, tumor recurrence with overlying skin changes, and radiation recall dermatitis. Given that the dermatitis had developed at the site of previously irradiated skin in the absence of fever or an associated mass, the presentation was thought to be most consistent with radiation recall dermatitis.

Oral prednisone was discontinued, and the dermatitis spontaneously improved in a few weeks. Given the patient’s test results and prior tolerance to triamcinolone, eosinophilic gastroenteritis was treated with triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg via intramuscular injection, which was well tolerated.

Radiation recall dermatitis is an acute inflammatory reaction over an area of skin that was previously irradiated. It is most often triggered by chemotherapy agents and occurs in as many as 9% of patients who receive chemotherapy after radiation.1 Commonly implicated chemotherapy agents include anthracyclines, taxanes, antimetabolites, and alkylating agents. Newer targeted cancer treatments also have been reported to trigger radiation recall dermatitis, including epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, and anti–programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibodies.2-5 Radiation recall dermatitis also has been reported to be triggered by intravenous contrast dye.6

The clinical presentation of radiation recall dermatitis ranges from mild rash to skin necrosis and desquamation. Patients often report pruritus or pain in the affected area. The US National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) includes a 5-point scale for grading the severity of radiation recall dermatitis: grade 1, faint erythema or dry desquamation; grade 2, moderate to brisk erythema or patchy moist desquamation, mostly confined to skin folds and creases; grade 3, moist desquamation in areas other than skin folds and creases, with bleeding induced by minor trauma or abrasion; grade 4, skin necrosis or ulceration of full-thickness dermis, with spontaneous bleeding; grade 5, death.7 Based on these criteria, our patient had grade 2 radiation recall dermatitis.

In addition to cutaneous inflammation, additional sites can be inflamed, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and oral mucosa. Cases of myocarditis, sialadenitis, and cystitis also have been reported.⁷

Radiation recall dermatitis can occur even if dermatitis did not occur upon initial treatment. The inflammatory reaction can occur weeks or years after initial irradiation. A study evaluating targeted chemotherapy agents found the median time from initiation of chemotherapy to radiation recall dermatitis was 16.9 weeks (range, 1–86.9 weeks). Inflammation usually lasts approximately 1 to 2 weeks but has been reported to persist as long as 14 weeks.8 Withdrawal of the offending agent in addition to administration of corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents typically results in clinical improvement. Histology on skin biopsy is nonspecific and can reveal mixed infiltrates.7

The pathophysiology of radiation recall dermatitis remains unknown; the condition might be an idiosyncratic drug reaction. It has been hypothesized that prior radiation lowers the threshold for an inflammatory reaction, an example of Ruocco immunocompromised cutaneous districts, in which a prior injury at a cutaneous site increases the likelihood of opportunistic infection, tumor, and immune reactions.9 Because radiation can induce expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, platelet-derived growth factor β, and tumor necrosis factor α, cells in irradiated areas can continue to secrete low levels of these cytokines after radiation therapy, thus priming an inflammatory reaction in the future.10 An alternative theory is that radiation induces mutations within surviving stem cells, rendering them unable to tolerate or unusually sensitive to subsequent chemotherapy and cytotoxic drugs. However, this premise would not explain how noncytotoxic drugs also can trigger radiation recall dermatitis, as described in our case.11

Prednisone-triggered radiation recall dermatitis is curious, as corticosteroids are used to treat the condition. Corticosteroids are classified by their chemical structure, and patch testing can be used to distinguish allergies across the various classes. Hydrocortisone acetate,

In contrast, triamcinolone is a class B steroid, which has a C16,17-cis-diol or -ketal. Other than budesonide, which can cross-react with D2 steroids, class B steroids do not cross-react with hydrocortisone or prednisone. Triamcinolone does not usually cross-react with D2 corticosteroids, which likely explains why our patient was later able to tolerate triamcinolone to treat eosinophilic gastrointestinal tract disease.

In summary, we present a case of radiation recall dermatitis triggered by prednisone. Radiation can prime an area for a future inflammatory response by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines or triggering stem cell mutation. In our case, clinical reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and sensitization to tixocortol pivalate via patch testing could have increased the likelihood of a reaction with prednisone use due to cross-reactivity. This case instructs dermatologists, allergists, and oncologists to be aware of prednisone as a potential trigger of radiation recall dermatitis.

- Kodym E, Kalinska R, Ehringfeld C, et al. Frequency of radiation recall dermatitis in adult cancer patients. Onkologie. 2005;28:18-21.

- Seidel C, Janssen S, Karstens JH, et al. Recall pneumonitis during systemic treatment with sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2119-2120.

- Togashi Y, Masago K, Mishima M, et al. A case of radiation recall pneumonitis induced by erlotinib, which can be related to high plasma concentration. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:924-925.

- Bourgier C, Massard C, Moldovan C, et al. Total recall of radiotherapy with mTOR inhibitors: a novel and potentially frequent side-effect? Ann Oncol. 2011;22:485-486.

- Korman AM, Tyler KH, Kaffenberger BH. Radiation recall dermatitis associated with nivolumab for metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e75-e77.

- Lau SKM, Rahimi A. Radiation recall precipitated by iodinated nonionic contrast. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015;5:263-266.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic

_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Published November 27, 2017. Accessed June 10, 2020.] - Levy A, Hollebecque A, Bourgier C, et al. Targeted therapy-induced radiation recall. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1662-1668.

- Piccolo V, Baroni A, Russo T, et al. Ruocco’s immunocompromised cutaneous district. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:135-141.

- Johnson CJ, Piedboeuf P, Rubin P, et al. Early and persistent alterations in the expression of interleukin-1 alpha, interleukin-1 beta and tumour necrosis factor alpha mRNA levels in fibrosis-resistant and sensitive mice after thoracic irradiation. Radiat Res. 1996;145:762-767.

- Azira D, Magné N, Zouhair A, et al. Radiation recall: a well recognized but neglected phenomenon. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:555-570.

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman presented to the allergy clinic for evaluation of a rash on the left breast. The patient had a history of breast cancer that was treated with a lumpectomy followed by external beam radiation therapy (total dose, 6000 cGy) to the lateral aspect of the left breast approximately 4 years prior. She developed acute breast dermatitis from the radiation, which was self-treated with over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream. The patient subsequently developed a blistering skin eruption over the area where she applied the cream. She did not recall the subtype of hydrocortisone she used (butyrate and acetate are available over-the-counter). She discontinued the hydrocortisone and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1%, which was well tolerated, and the rash resolved.

The patient had a history of a similar reaction to hydrocortisone butyrate after blepharoplasty approximately 10 years prior to the current presentation, characterized by facial erythema, pruritus, and blistering. A patch test confirmed reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and tixocortol pivalate. However, a skin-prick test for hydrocortisone acetate cream 1% was negative.

Subsequently, the patient developed acute-onset dyspepsia, gnawing epigastric pain, regurgitation, and bloating. A diagnosis of eosinophilic gastritis was established via biopsy, which found increased eosinophils in the lamina propria (>50 eosinophils per high-power field). Helicobacter pylori was not identified. She was started on the proton-pump inhibitor dexlansoprazole but symptoms did not improve. Her other medications included benazepril, alprazolam as needed, vitamin D, and magnesium. The patient subsequently was started on a trial of oral prednisone 40 mg/d. Three days after initiation, she developed an erythematous macular rash over the left breast.

The next day she presented to the allergy clinic. Physical examination of the left breast revealed a 20×10-cm, nipple-sparing patch of well-demarcated erythema without fluctuance or overlying lesions. The area of erythema overlapped with the prior radiation field based on radiation marker tattoos and the lumpectomy scar (Figure). There was no evidence to suggest inflammation of deeper tissue or the pectoral muscles. Vital signs were normal, and the remainder of the examination was unremarkable, including breast, lymph node, and complete skin examinations.

At evaluation, the differential diagnosis included contact dermatitis, fixed drug eruption, infection, tumor recurrence with overlying skin changes, and radiation recall dermatitis. Given that the dermatitis had developed at the site of previously irradiated skin in the absence of fever or an associated mass, the presentation was thought to be most consistent with radiation recall dermatitis.

Oral prednisone was discontinued, and the dermatitis spontaneously improved in a few weeks. Given the patient’s test results and prior tolerance to triamcinolone, eosinophilic gastroenteritis was treated with triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg via intramuscular injection, which was well tolerated.

Radiation recall dermatitis is an acute inflammatory reaction over an area of skin that was previously irradiated. It is most often triggered by chemotherapy agents and occurs in as many as 9% of patients who receive chemotherapy after radiation.1 Commonly implicated chemotherapy agents include anthracyclines, taxanes, antimetabolites, and alkylating agents. Newer targeted cancer treatments also have been reported to trigger radiation recall dermatitis, including epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, and anti–programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibodies.2-5 Radiation recall dermatitis also has been reported to be triggered by intravenous contrast dye.6

The clinical presentation of radiation recall dermatitis ranges from mild rash to skin necrosis and desquamation. Patients often report pruritus or pain in the affected area. The US National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) includes a 5-point scale for grading the severity of radiation recall dermatitis: grade 1, faint erythema or dry desquamation; grade 2, moderate to brisk erythema or patchy moist desquamation, mostly confined to skin folds and creases; grade 3, moist desquamation in areas other than skin folds and creases, with bleeding induced by minor trauma or abrasion; grade 4, skin necrosis or ulceration of full-thickness dermis, with spontaneous bleeding; grade 5, death.7 Based on these criteria, our patient had grade 2 radiation recall dermatitis.

In addition to cutaneous inflammation, additional sites can be inflamed, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and oral mucosa. Cases of myocarditis, sialadenitis, and cystitis also have been reported.⁷

Radiation recall dermatitis can occur even if dermatitis did not occur upon initial treatment. The inflammatory reaction can occur weeks or years after initial irradiation. A study evaluating targeted chemotherapy agents found the median time from initiation of chemotherapy to radiation recall dermatitis was 16.9 weeks (range, 1–86.9 weeks). Inflammation usually lasts approximately 1 to 2 weeks but has been reported to persist as long as 14 weeks.8 Withdrawal of the offending agent in addition to administration of corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents typically results in clinical improvement. Histology on skin biopsy is nonspecific and can reveal mixed infiltrates.7

The pathophysiology of radiation recall dermatitis remains unknown; the condition might be an idiosyncratic drug reaction. It has been hypothesized that prior radiation lowers the threshold for an inflammatory reaction, an example of Ruocco immunocompromised cutaneous districts, in which a prior injury at a cutaneous site increases the likelihood of opportunistic infection, tumor, and immune reactions.9 Because radiation can induce expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, platelet-derived growth factor β, and tumor necrosis factor α, cells in irradiated areas can continue to secrete low levels of these cytokines after radiation therapy, thus priming an inflammatory reaction in the future.10 An alternative theory is that radiation induces mutations within surviving stem cells, rendering them unable to tolerate or unusually sensitive to subsequent chemotherapy and cytotoxic drugs. However, this premise would not explain how noncytotoxic drugs also can trigger radiation recall dermatitis, as described in our case.11

Prednisone-triggered radiation recall dermatitis is curious, as corticosteroids are used to treat the condition. Corticosteroids are classified by their chemical structure, and patch testing can be used to distinguish allergies across the various classes. Hydrocortisone acetate,

In contrast, triamcinolone is a class B steroid, which has a C16,17-cis-diol or -ketal. Other than budesonide, which can cross-react with D2 steroids, class B steroids do not cross-react with hydrocortisone or prednisone. Triamcinolone does not usually cross-react with D2 corticosteroids, which likely explains why our patient was later able to tolerate triamcinolone to treat eosinophilic gastrointestinal tract disease.

In summary, we present a case of radiation recall dermatitis triggered by prednisone. Radiation can prime an area for a future inflammatory response by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines or triggering stem cell mutation. In our case, clinical reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and sensitization to tixocortol pivalate via patch testing could have increased the likelihood of a reaction with prednisone use due to cross-reactivity. This case instructs dermatologists, allergists, and oncologists to be aware of prednisone as a potential trigger of radiation recall dermatitis.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman presented to the allergy clinic for evaluation of a rash on the left breast. The patient had a history of breast cancer that was treated with a lumpectomy followed by external beam radiation therapy (total dose, 6000 cGy) to the lateral aspect of the left breast approximately 4 years prior. She developed acute breast dermatitis from the radiation, which was self-treated with over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream. The patient subsequently developed a blistering skin eruption over the area where she applied the cream. She did not recall the subtype of hydrocortisone she used (butyrate and acetate are available over-the-counter). She discontinued the hydrocortisone and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1%, which was well tolerated, and the rash resolved.

The patient had a history of a similar reaction to hydrocortisone butyrate after blepharoplasty approximately 10 years prior to the current presentation, characterized by facial erythema, pruritus, and blistering. A patch test confirmed reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and tixocortol pivalate. However, a skin-prick test for hydrocortisone acetate cream 1% was negative.

Subsequently, the patient developed acute-onset dyspepsia, gnawing epigastric pain, regurgitation, and bloating. A diagnosis of eosinophilic gastritis was established via biopsy, which found increased eosinophils in the lamina propria (>50 eosinophils per high-power field). Helicobacter pylori was not identified. She was started on the proton-pump inhibitor dexlansoprazole but symptoms did not improve. Her other medications included benazepril, alprazolam as needed, vitamin D, and magnesium. The patient subsequently was started on a trial of oral prednisone 40 mg/d. Three days after initiation, she developed an erythematous macular rash over the left breast.

The next day she presented to the allergy clinic. Physical examination of the left breast revealed a 20×10-cm, nipple-sparing patch of well-demarcated erythema without fluctuance or overlying lesions. The area of erythema overlapped with the prior radiation field based on radiation marker tattoos and the lumpectomy scar (Figure). There was no evidence to suggest inflammation of deeper tissue or the pectoral muscles. Vital signs were normal, and the remainder of the examination was unremarkable, including breast, lymph node, and complete skin examinations.

At evaluation, the differential diagnosis included contact dermatitis, fixed drug eruption, infection, tumor recurrence with overlying skin changes, and radiation recall dermatitis. Given that the dermatitis had developed at the site of previously irradiated skin in the absence of fever or an associated mass, the presentation was thought to be most consistent with radiation recall dermatitis.

Oral prednisone was discontinued, and the dermatitis spontaneously improved in a few weeks. Given the patient’s test results and prior tolerance to triamcinolone, eosinophilic gastroenteritis was treated with triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg via intramuscular injection, which was well tolerated.

Radiation recall dermatitis is an acute inflammatory reaction over an area of skin that was previously irradiated. It is most often triggered by chemotherapy agents and occurs in as many as 9% of patients who receive chemotherapy after radiation.1 Commonly implicated chemotherapy agents include anthracyclines, taxanes, antimetabolites, and alkylating agents. Newer targeted cancer treatments also have been reported to trigger radiation recall dermatitis, including epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, and anti–programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibodies.2-5 Radiation recall dermatitis also has been reported to be triggered by intravenous contrast dye.6

The clinical presentation of radiation recall dermatitis ranges from mild rash to skin necrosis and desquamation. Patients often report pruritus or pain in the affected area. The US National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) includes a 5-point scale for grading the severity of radiation recall dermatitis: grade 1, faint erythema or dry desquamation; grade 2, moderate to brisk erythema or patchy moist desquamation, mostly confined to skin folds and creases; grade 3, moist desquamation in areas other than skin folds and creases, with bleeding induced by minor trauma or abrasion; grade 4, skin necrosis or ulceration of full-thickness dermis, with spontaneous bleeding; grade 5, death.7 Based on these criteria, our patient had grade 2 radiation recall dermatitis.

In addition to cutaneous inflammation, additional sites can be inflamed, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and oral mucosa. Cases of myocarditis, sialadenitis, and cystitis also have been reported.⁷

Radiation recall dermatitis can occur even if dermatitis did not occur upon initial treatment. The inflammatory reaction can occur weeks or years after initial irradiation. A study evaluating targeted chemotherapy agents found the median time from initiation of chemotherapy to radiation recall dermatitis was 16.9 weeks (range, 1–86.9 weeks). Inflammation usually lasts approximately 1 to 2 weeks but has been reported to persist as long as 14 weeks.8 Withdrawal of the offending agent in addition to administration of corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents typically results in clinical improvement. Histology on skin biopsy is nonspecific and can reveal mixed infiltrates.7

The pathophysiology of radiation recall dermatitis remains unknown; the condition might be an idiosyncratic drug reaction. It has been hypothesized that prior radiation lowers the threshold for an inflammatory reaction, an example of Ruocco immunocompromised cutaneous districts, in which a prior injury at a cutaneous site increases the likelihood of opportunistic infection, tumor, and immune reactions.9 Because radiation can induce expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, platelet-derived growth factor β, and tumor necrosis factor α, cells in irradiated areas can continue to secrete low levels of these cytokines after radiation therapy, thus priming an inflammatory reaction in the future.10 An alternative theory is that radiation induces mutations within surviving stem cells, rendering them unable to tolerate or unusually sensitive to subsequent chemotherapy and cytotoxic drugs. However, this premise would not explain how noncytotoxic drugs also can trigger radiation recall dermatitis, as described in our case.11

Prednisone-triggered radiation recall dermatitis is curious, as corticosteroids are used to treat the condition. Corticosteroids are classified by their chemical structure, and patch testing can be used to distinguish allergies across the various classes. Hydrocortisone acetate,

In contrast, triamcinolone is a class B steroid, which has a C16,17-cis-diol or -ketal. Other than budesonide, which can cross-react with D2 steroids, class B steroids do not cross-react with hydrocortisone or prednisone. Triamcinolone does not usually cross-react with D2 corticosteroids, which likely explains why our patient was later able to tolerate triamcinolone to treat eosinophilic gastrointestinal tract disease.

In summary, we present a case of radiation recall dermatitis triggered by prednisone. Radiation can prime an area for a future inflammatory response by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines or triggering stem cell mutation. In our case, clinical reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and sensitization to tixocortol pivalate via patch testing could have increased the likelihood of a reaction with prednisone use due to cross-reactivity. This case instructs dermatologists, allergists, and oncologists to be aware of prednisone as a potential trigger of radiation recall dermatitis.

- Kodym E, Kalinska R, Ehringfeld C, et al. Frequency of radiation recall dermatitis in adult cancer patients. Onkologie. 2005;28:18-21.

- Seidel C, Janssen S, Karstens JH, et al. Recall pneumonitis during systemic treatment with sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2119-2120.

- Togashi Y, Masago K, Mishima M, et al. A case of radiation recall pneumonitis induced by erlotinib, which can be related to high plasma concentration. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:924-925.

- Bourgier C, Massard C, Moldovan C, et al. Total recall of radiotherapy with mTOR inhibitors: a novel and potentially frequent side-effect? Ann Oncol. 2011;22:485-486.

- Korman AM, Tyler KH, Kaffenberger BH. Radiation recall dermatitis associated with nivolumab for metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e75-e77.

- Lau SKM, Rahimi A. Radiation recall precipitated by iodinated nonionic contrast. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015;5:263-266.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic

_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Published November 27, 2017. Accessed June 10, 2020.] - Levy A, Hollebecque A, Bourgier C, et al. Targeted therapy-induced radiation recall. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1662-1668.

- Piccolo V, Baroni A, Russo T, et al. Ruocco’s immunocompromised cutaneous district. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:135-141.

- Johnson CJ, Piedboeuf P, Rubin P, et al. Early and persistent alterations in the expression of interleukin-1 alpha, interleukin-1 beta and tumour necrosis factor alpha mRNA levels in fibrosis-resistant and sensitive mice after thoracic irradiation. Radiat Res. 1996;145:762-767.

- Azira D, Magné N, Zouhair A, et al. Radiation recall: a well recognized but neglected phenomenon. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:555-570.

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727.

- Kodym E, Kalinska R, Ehringfeld C, et al. Frequency of radiation recall dermatitis in adult cancer patients. Onkologie. 2005;28:18-21.

- Seidel C, Janssen S, Karstens JH, et al. Recall pneumonitis during systemic treatment with sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2119-2120.

- Togashi Y, Masago K, Mishima M, et al. A case of radiation recall pneumonitis induced by erlotinib, which can be related to high plasma concentration. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:924-925.

- Bourgier C, Massard C, Moldovan C, et al. Total recall of radiotherapy with mTOR inhibitors: a novel and potentially frequent side-effect? Ann Oncol. 2011;22:485-486.

- Korman AM, Tyler KH, Kaffenberger BH. Radiation recall dermatitis associated with nivolumab for metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e75-e77.

- Lau SKM, Rahimi A. Radiation recall precipitated by iodinated nonionic contrast. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015;5:263-266.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic

_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Published November 27, 2017. Accessed June 10, 2020.] - Levy A, Hollebecque A, Bourgier C, et al. Targeted therapy-induced radiation recall. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1662-1668.

- Piccolo V, Baroni A, Russo T, et al. Ruocco’s immunocompromised cutaneous district. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:135-141.

- Johnson CJ, Piedboeuf P, Rubin P, et al. Early and persistent alterations in the expression of interleukin-1 alpha, interleukin-1 beta and tumour necrosis factor alpha mRNA levels in fibrosis-resistant and sensitive mice after thoracic irradiation. Radiat Res. 1996;145:762-767.

- Azira D, Magné N, Zouhair A, et al. Radiation recall: a well recognized but neglected phenomenon. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:555-570.

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727.

Practice Points

- Consider the diagnosis of radiation recall dermatitis for a skin eruption that occurs in the same location as prior radiation exposure.

- Prednisone may be a trigger for radiation recall dermatitis in patients with sensitization to cross-reactive topical steroids such as tixocortol pivalate.

- Radiation therapy may prime the skin for a future inflammatory response by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines that persist after the conclusion of treatment.

Isobornyl Acrylate and Diabetic Devices Steal the Show for the 2020 American Contact Dermatitis Society Allergen of the Year

Each year, the American Contact Dermatitis Society names an Allergen of the Year with the purpose of promoting greater awareness of a key allergen and its impact on patients. Often, the Allergen of the Year is an emerging allergen that may represent an underrecognized or novel cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).In 2020, the American Contact Dermatitis Society chose isobornyl acrylate as the Allergen of the Year.1 Not only has isobornyl acrylate been implicated in an epidemic of contact allergy to diabetic devices, but it also illustrates the challenges of investigating contact allergy to medical devices in general.

What Is Isobornyl Acrylate?

Isobornyl acrylate, also known as the isobornyl ester of acrylic acid, is a chemical used in glues, adhesives, coatings, sealants, inks, and paints. Similar to other acrylates, such as those involved in gel nail treatments, it is photopolymerizable; that is, when exposed to UV light, it can transform from a liquid monomer into a hard polymer, contributing to its utility as an adhesive. Prior to its recent implication in diabetic device contact allergy, isobornyl acrylate was not thought to be a common skin sensitizer. In a 2013 Dutch study of patients with acrylate allergy, only 1 of 14 patients with a contact allergy to other acrylates had a positive patch test reaction to isobornyl acrylate, which led the authors to conclude that adding it to their acrylate patch test series was not indicated.2

Isobornyl Acrylate in Diabetic Devices

Devices such as glucose monitoring systems and insulin pumps are used by millions of patients with diabetes worldwide. Not only are continuous glucose monitoring devices more convenient than self-monitoring of blood glucose, but they also are associated with a reduction in hemoglobin A1c levels and lower risk for hypoglycemia.3 However, these devices have been increasingly recognized as a source of irritant contact dermatitis and ACD.

Early cases of contact allergy to isobornyl acrylate in diabetic devices were reported in 1995 when 2 Belgian patients using insulin pumps developed ACD.4 The patients had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum and other allergens including acrylates. In addition, patch testing with plastic scrapings from their insulin pumps also was positive, and it was determined that the glue affixing the needle to the plastic had diffused into the plastic. The patients were switched to insulin pumps produced by heat staking instead of glue, and their symptoms resolved. In retrospect, this case series may seem prescient, as it was written 2 decades before isobornyl acrylate became recognized as a widespread cause of ACD in users of diabetic devices. Admittedly, other acrylate components of the glue also were positive on patch testing in these patients, so it was not until much later that the focus turned more exclusively to isobornyl acrylate.4

Similar to the insulin pumps in the 1995 Belgian series, diffusion of glue to other parts of modern glucose sensors also appears to cause isobornyl acrylate contact allergy. This theory was supported by a 2017 study from Belgian and Swedish investigators in which gas chromatography–mass spectrometry was used to identify concentrations of isobornyl acrylate in various components of a popular continuous glucose monitoring sensor.5 The concentration of isobornyl acrylate was approximately 100-fold higher at the site where the top and bottom plastic components of the sensor were joined as compared to the adhesive patch in contact with the patient’s skin. Therefore, the adhesive patch itself was not the source of the isobornyl acrylate exposure; rather, the isobornyl acrylate diffused into the adhesive patch from the glue used to join the components of the sensor together.5 One ramification is that patients with diabetic device contact allergy can have a false-negative patch test result if the adhesive patch is tested by itself, whereas they may react to patch testing with the whole sensor or an acetonic extract thereof.

Frequency of Sensitization to Isobornyl Acrylate

It is difficult to estimate the frequency of sensitization to isobornyl acrylate among users of diabetic devices, in part because those with mild allergy may not seek medical treatment. Nevertheless, there are studies that demonstrate a high prevalence of sensitization among users with suspected allergy. In a 2019 Finnish study of 6567 patients using an isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor, 63 were patch tested for suspected ACD.6 Of these 63 patients, 51 (81%) had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum. These findings were consistent with the original 2017 study from Belgium and Sweden, in which 10 of 11 (91%) patients who used an isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor and had suspected contact allergy had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum compared to no positive reactions in the 14 control patients.5 Given that there are more than 1.5 million users of this isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor across 46 countries,7 it requires no stretch of the imagination to understand why investigators refer to isobornyl acrylate allergy as an epidemic, even if only a small percentage of users are sensitized to the device.

The Journey to Discover Isobornyl Acrylate as a Culprit Allergen

Similar to the discoveries of radiography and penicillin, the discovery of isobornyl acrylate as a culprit allergen in a modern glucose sensor was purely accidental. In 2016, a 9-year-old boy with diabetes presented to a Belgian dermatology department with ACD to a glucose sensor.1 A patch test nurse serendipitously applied isobornyl acrylate—0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% in petrolatum—which was not intended to be applied as part of the typical acrylate series. The only positive patch test reactions in this patient were to isobornyl acrylate at all 3 concentrations. This lucky error inspired isobornyl acrylate to be tested at multiple other dermatology departments in Europe in patients with ACD to their glucose sensors, leading to its discovery as a culprit allergen.1

One challenge facing investigators was obtaining information and materials from the diabetic device industry. Medical device manufacturers are not required to disclose chemicals present in a device on its label.8 Therefore, for patients or investigators to determine whether a potential allergen is present in a given device, they must request that information from the manufacturer, which can be a time-consuming and frustrating effort. Luckily, investigators collaborated with one another, and Belgian investigators suggested that Swedish investigators performing chemical analyses on a glucose monitoring device should focus on isobornyl acrylate, which enabled its detection in an extract from the device.5

Testing for Isobornyl Acrylate Allergy in Your Clinic

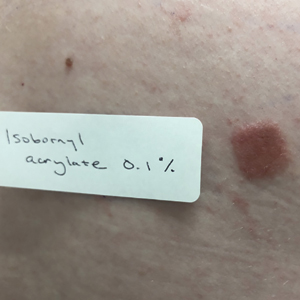

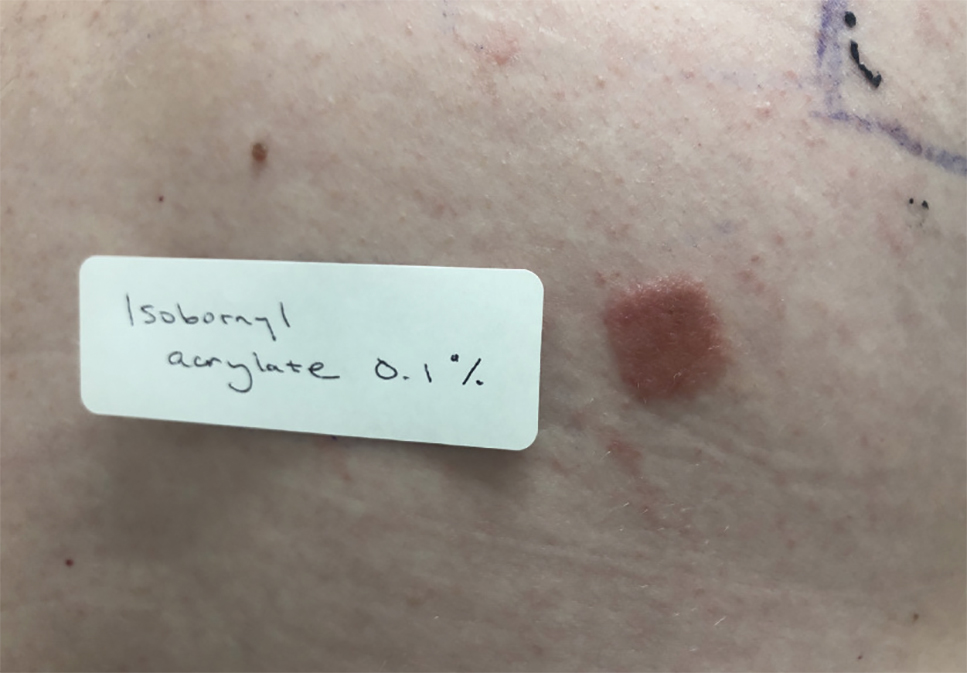

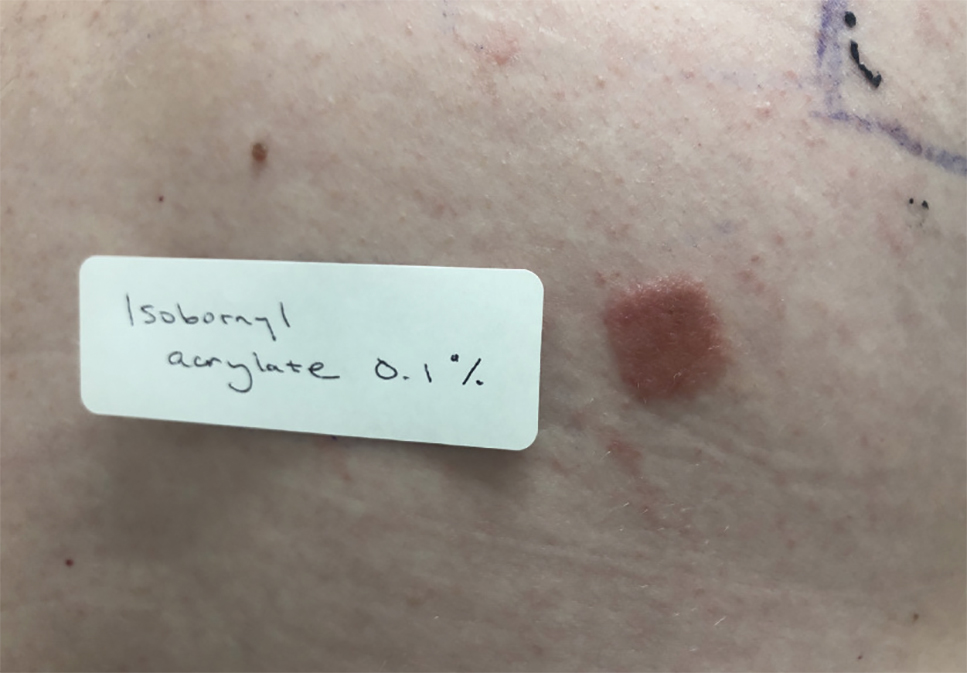

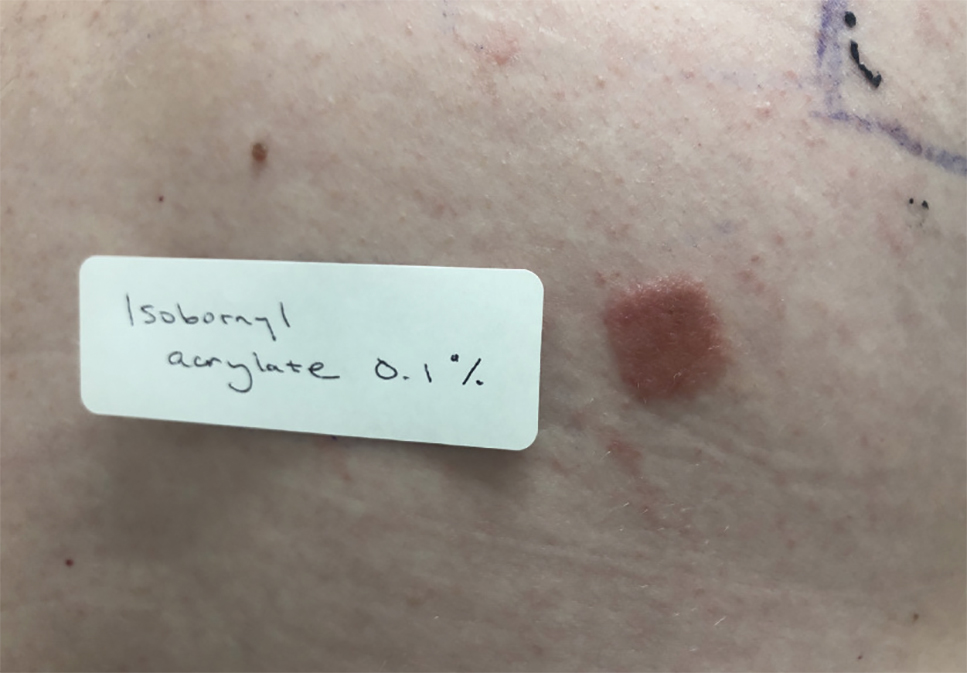

Patients with suspected ACD to a diabetic device—insulin pump or glucose sensor—should be patch tested with isobornyl acrylate, in addition to other previously reported allergens. The vehicle typically is petrolatum, and the commonly tested concentration is 0.1%. Testing with lower concentrations such as 0.01% can result in false-negative reactions,9 and testing at higher concentrations such as 0.3% can result in irritant skin reactions.2 Isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum currently is available from one commercial allergen supplier (Chemotechnique Diagnostics). A positive patch test reaction to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is shown in the Figure.

Management of Diabetic Device ACD

For patients with diabetic device ACD, there are several strategies that can reduce direct contact between the device and the patient’s skin. Methods that have been tried with varying success to allow patients to continue using their glucose sensors include barrier sprays (eg, Cavilon [3M], Silesse Skin Barrier [ConvaTec]); barrier pads (eg, Compeed [HRA Pharma], Surround skin protectors [Eakin], DuoDERM dressings [ConvaTec], Tegaderm dressings [3M]); and topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors. Nevertheless, a 2019 Finnish study showed that only 14 of 63 (22%) patients with ACD to their isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor were able to continue using the device, with all 14 requiring use of a barrier agent. Despite using the barrier agent, 13 (93%) of these patients had residual dermatitis.6 There also is concern that use of barrier methods might hamper the proper functioning of glucose sensors and related devices.

Patients with known isobornyl acrylate contact allergy also may switch to a different diabetic device. A 2019 German study showed that in 5 patients with isobornyl acrylate ACD, none had reactions to the one particular system that has been shown by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to not contain isobornyl acrylate.10 However, as a word of caution, the same device also has been associated with ACD11,12 but has been resolved by using heat staking during the production process.13 As manufacturers update device components, identification of other isobornyl acrylate–free devices may require a degree of trial and error, as neither isobornyl acrylate nor any other potential allergen is listed on device labels.

Final Interpretation

Isobornyl acrylate is not a common sensitizer in general patch test populations but is a recently identified major culprit in ACD to diabetic devices. Patch testing with isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is not necessary in standard screening panels but should be considered in patients with suspected ACD to glucose sensors or insulin pumps. If a patient with ACD wants to continue to experience the convenience provided by a diabetic device, options include using topical steroids or barrier agents and/or changing the brand of the diabetic device, though none of these methods are foolproof. Hopefully, the identification of isobornyl acrylate as a culprit allergen will help to improve the lives of patients who use diabetic devices worldwide.

- Aerts O, Herman A, Mowitz M, et al. Isobornyl acrylate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:4-12.

- Christoffers WA, Coenraads PJ, Schuttelaar ML. Two decades of occupational (meth)acrylate patch test results and focus on isobornyl acrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;69:86-92.

- Pickup JC, Freeman SC, Sutton AJ. Glycaemic control in type 1 diabetes during real time continuous glucose monitoring compared with self monitoring of blood glucose: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials using individual patient data. BMJ. 2011;343:d3805.

- Busschots AM, Meuleman V, Poesen N, et al. Contact allergy to components of glue in insulin pump infusion sets. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:205-206.

- Herman A, Aerts O, Baeck M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in Freestyle® Libre, a newly introduced glucose sensor. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:367-373.

- Hyry HSI, Liippo JP, Virtanen HM. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by glucose sensors in type 1 diabetes patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:161-166.

- Abbott’s Revolutionary FreeStyle® Libre system now reimbursed in the two largest provinces in Canada [press release]. Abbott Park, IL: Abbott; September 13, 2019. https://abbott.mediaroom.com/2019-09-13-Abbotts-Revolutionary-FreeStyle-R-Libre-System-Now-Reimbursed-in-the-Two-Largest-Provinces-in-Canada. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- Herman A, Goossens A. The need to disclose the composition of medical devices at the European level. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:159-160.

- Raison-Peyron N, Mowitz M, Bonardel N, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in OmniPod, an innovative tubeless insulin pump. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:76-80.

- Oppel E, Kamann S, Reichl FX, et al. The Dexcom glucose monitoring system—an isobornyl acrylate-free alternative for diabetic patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:32-36.

- Peeters C, Herman A, Goossens A, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by 2-ethyl cyanoacrylate contained in glucose sensor sets in two diabetic adults. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:426-429.

- Aschenbeck KA, Hylwa SA. A diabetic’s allergy: ethyl cyanoacrylate in glucose sensor adhesive. Dermatitis. 2017;28:289-291.

- Gisin V, Chan A, Welsh B. Manufacturing process changes and reduced skin irritations of an adhesive patch used for continuous glucose monitoring devices. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12:725-726.

Each year, the American Contact Dermatitis Society names an Allergen of the Year with the purpose of promoting greater awareness of a key allergen and its impact on patients. Often, the Allergen of the Year is an emerging allergen that may represent an underrecognized or novel cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).In 2020, the American Contact Dermatitis Society chose isobornyl acrylate as the Allergen of the Year.1 Not only has isobornyl acrylate been implicated in an epidemic of contact allergy to diabetic devices, but it also illustrates the challenges of investigating contact allergy to medical devices in general.

What Is Isobornyl Acrylate?

Isobornyl acrylate, also known as the isobornyl ester of acrylic acid, is a chemical used in glues, adhesives, coatings, sealants, inks, and paints. Similar to other acrylates, such as those involved in gel nail treatments, it is photopolymerizable; that is, when exposed to UV light, it can transform from a liquid monomer into a hard polymer, contributing to its utility as an adhesive. Prior to its recent implication in diabetic device contact allergy, isobornyl acrylate was not thought to be a common skin sensitizer. In a 2013 Dutch study of patients with acrylate allergy, only 1 of 14 patients with a contact allergy to other acrylates had a positive patch test reaction to isobornyl acrylate, which led the authors to conclude that adding it to their acrylate patch test series was not indicated.2

Isobornyl Acrylate in Diabetic Devices

Devices such as glucose monitoring systems and insulin pumps are used by millions of patients with diabetes worldwide. Not only are continuous glucose monitoring devices more convenient than self-monitoring of blood glucose, but they also are associated with a reduction in hemoglobin A1c levels and lower risk for hypoglycemia.3 However, these devices have been increasingly recognized as a source of irritant contact dermatitis and ACD.

Early cases of contact allergy to isobornyl acrylate in diabetic devices were reported in 1995 when 2 Belgian patients using insulin pumps developed ACD.4 The patients had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum and other allergens including acrylates. In addition, patch testing with plastic scrapings from their insulin pumps also was positive, and it was determined that the glue affixing the needle to the plastic had diffused into the plastic. The patients were switched to insulin pumps produced by heat staking instead of glue, and their symptoms resolved. In retrospect, this case series may seem prescient, as it was written 2 decades before isobornyl acrylate became recognized as a widespread cause of ACD in users of diabetic devices. Admittedly, other acrylate components of the glue also were positive on patch testing in these patients, so it was not until much later that the focus turned more exclusively to isobornyl acrylate.4

Similar to the insulin pumps in the 1995 Belgian series, diffusion of glue to other parts of modern glucose sensors also appears to cause isobornyl acrylate contact allergy. This theory was supported by a 2017 study from Belgian and Swedish investigators in which gas chromatography–mass spectrometry was used to identify concentrations of isobornyl acrylate in various components of a popular continuous glucose monitoring sensor.5 The concentration of isobornyl acrylate was approximately 100-fold higher at the site where the top and bottom plastic components of the sensor were joined as compared to the adhesive patch in contact with the patient’s skin. Therefore, the adhesive patch itself was not the source of the isobornyl acrylate exposure; rather, the isobornyl acrylate diffused into the adhesive patch from the glue used to join the components of the sensor together.5 One ramification is that patients with diabetic device contact allergy can have a false-negative patch test result if the adhesive patch is tested by itself, whereas they may react to patch testing with the whole sensor or an acetonic extract thereof.

Frequency of Sensitization to Isobornyl Acrylate

It is difficult to estimate the frequency of sensitization to isobornyl acrylate among users of diabetic devices, in part because those with mild allergy may not seek medical treatment. Nevertheless, there are studies that demonstrate a high prevalence of sensitization among users with suspected allergy. In a 2019 Finnish study of 6567 patients using an isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor, 63 were patch tested for suspected ACD.6 Of these 63 patients, 51 (81%) had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum. These findings were consistent with the original 2017 study from Belgium and Sweden, in which 10 of 11 (91%) patients who used an isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor and had suspected contact allergy had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum compared to no positive reactions in the 14 control patients.5 Given that there are more than 1.5 million users of this isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor across 46 countries,7 it requires no stretch of the imagination to understand why investigators refer to isobornyl acrylate allergy as an epidemic, even if only a small percentage of users are sensitized to the device.

The Journey to Discover Isobornyl Acrylate as a Culprit Allergen

Similar to the discoveries of radiography and penicillin, the discovery of isobornyl acrylate as a culprit allergen in a modern glucose sensor was purely accidental. In 2016, a 9-year-old boy with diabetes presented to a Belgian dermatology department with ACD to a glucose sensor.1 A patch test nurse serendipitously applied isobornyl acrylate—0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% in petrolatum—which was not intended to be applied as part of the typical acrylate series. The only positive patch test reactions in this patient were to isobornyl acrylate at all 3 concentrations. This lucky error inspired isobornyl acrylate to be tested at multiple other dermatology departments in Europe in patients with ACD to their glucose sensors, leading to its discovery as a culprit allergen.1

One challenge facing investigators was obtaining information and materials from the diabetic device industry. Medical device manufacturers are not required to disclose chemicals present in a device on its label.8 Therefore, for patients or investigators to determine whether a potential allergen is present in a given device, they must request that information from the manufacturer, which can be a time-consuming and frustrating effort. Luckily, investigators collaborated with one another, and Belgian investigators suggested that Swedish investigators performing chemical analyses on a glucose monitoring device should focus on isobornyl acrylate, which enabled its detection in an extract from the device.5

Testing for Isobornyl Acrylate Allergy in Your Clinic

Patients with suspected ACD to a diabetic device—insulin pump or glucose sensor—should be patch tested with isobornyl acrylate, in addition to other previously reported allergens. The vehicle typically is petrolatum, and the commonly tested concentration is 0.1%. Testing with lower concentrations such as 0.01% can result in false-negative reactions,9 and testing at higher concentrations such as 0.3% can result in irritant skin reactions.2 Isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum currently is available from one commercial allergen supplier (Chemotechnique Diagnostics). A positive patch test reaction to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is shown in the Figure.

Management of Diabetic Device ACD

For patients with diabetic device ACD, there are several strategies that can reduce direct contact between the device and the patient’s skin. Methods that have been tried with varying success to allow patients to continue using their glucose sensors include barrier sprays (eg, Cavilon [3M], Silesse Skin Barrier [ConvaTec]); barrier pads (eg, Compeed [HRA Pharma], Surround skin protectors [Eakin], DuoDERM dressings [ConvaTec], Tegaderm dressings [3M]); and topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors. Nevertheless, a 2019 Finnish study showed that only 14 of 63 (22%) patients with ACD to their isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor were able to continue using the device, with all 14 requiring use of a barrier agent. Despite using the barrier agent, 13 (93%) of these patients had residual dermatitis.6 There also is concern that use of barrier methods might hamper the proper functioning of glucose sensors and related devices.

Patients with known isobornyl acrylate contact allergy also may switch to a different diabetic device. A 2019 German study showed that in 5 patients with isobornyl acrylate ACD, none had reactions to the one particular system that has been shown by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to not contain isobornyl acrylate.10 However, as a word of caution, the same device also has been associated with ACD11,12 but has been resolved by using heat staking during the production process.13 As manufacturers update device components, identification of other isobornyl acrylate–free devices may require a degree of trial and error, as neither isobornyl acrylate nor any other potential allergen is listed on device labels.

Final Interpretation

Isobornyl acrylate is not a common sensitizer in general patch test populations but is a recently identified major culprit in ACD to diabetic devices. Patch testing with isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is not necessary in standard screening panels but should be considered in patients with suspected ACD to glucose sensors or insulin pumps. If a patient with ACD wants to continue to experience the convenience provided by a diabetic device, options include using topical steroids or barrier agents and/or changing the brand of the diabetic device, though none of these methods are foolproof. Hopefully, the identification of isobornyl acrylate as a culprit allergen will help to improve the lives of patients who use diabetic devices worldwide.

Each year, the American Contact Dermatitis Society names an Allergen of the Year with the purpose of promoting greater awareness of a key allergen and its impact on patients. Often, the Allergen of the Year is an emerging allergen that may represent an underrecognized or novel cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).In 2020, the American Contact Dermatitis Society chose isobornyl acrylate as the Allergen of the Year.1 Not only has isobornyl acrylate been implicated in an epidemic of contact allergy to diabetic devices, but it also illustrates the challenges of investigating contact allergy to medical devices in general.

What Is Isobornyl Acrylate?

Isobornyl acrylate, also known as the isobornyl ester of acrylic acid, is a chemical used in glues, adhesives, coatings, sealants, inks, and paints. Similar to other acrylates, such as those involved in gel nail treatments, it is photopolymerizable; that is, when exposed to UV light, it can transform from a liquid monomer into a hard polymer, contributing to its utility as an adhesive. Prior to its recent implication in diabetic device contact allergy, isobornyl acrylate was not thought to be a common skin sensitizer. In a 2013 Dutch study of patients with acrylate allergy, only 1 of 14 patients with a contact allergy to other acrylates had a positive patch test reaction to isobornyl acrylate, which led the authors to conclude that adding it to their acrylate patch test series was not indicated.2

Isobornyl Acrylate in Diabetic Devices

Devices such as glucose monitoring systems and insulin pumps are used by millions of patients with diabetes worldwide. Not only are continuous glucose monitoring devices more convenient than self-monitoring of blood glucose, but they also are associated with a reduction in hemoglobin A1c levels and lower risk for hypoglycemia.3 However, these devices have been increasingly recognized as a source of irritant contact dermatitis and ACD.

Early cases of contact allergy to isobornyl acrylate in diabetic devices were reported in 1995 when 2 Belgian patients using insulin pumps developed ACD.4 The patients had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum and other allergens including acrylates. In addition, patch testing with plastic scrapings from their insulin pumps also was positive, and it was determined that the glue affixing the needle to the plastic had diffused into the plastic. The patients were switched to insulin pumps produced by heat staking instead of glue, and their symptoms resolved. In retrospect, this case series may seem prescient, as it was written 2 decades before isobornyl acrylate became recognized as a widespread cause of ACD in users of diabetic devices. Admittedly, other acrylate components of the glue also were positive on patch testing in these patients, so it was not until much later that the focus turned more exclusively to isobornyl acrylate.4

Similar to the insulin pumps in the 1995 Belgian series, diffusion of glue to other parts of modern glucose sensors also appears to cause isobornyl acrylate contact allergy. This theory was supported by a 2017 study from Belgian and Swedish investigators in which gas chromatography–mass spectrometry was used to identify concentrations of isobornyl acrylate in various components of a popular continuous glucose monitoring sensor.5 The concentration of isobornyl acrylate was approximately 100-fold higher at the site where the top and bottom plastic components of the sensor were joined as compared to the adhesive patch in contact with the patient’s skin. Therefore, the adhesive patch itself was not the source of the isobornyl acrylate exposure; rather, the isobornyl acrylate diffused into the adhesive patch from the glue used to join the components of the sensor together.5 One ramification is that patients with diabetic device contact allergy can have a false-negative patch test result if the adhesive patch is tested by itself, whereas they may react to patch testing with the whole sensor or an acetonic extract thereof.

Frequency of Sensitization to Isobornyl Acrylate

It is difficult to estimate the frequency of sensitization to isobornyl acrylate among users of diabetic devices, in part because those with mild allergy may not seek medical treatment. Nevertheless, there are studies that demonstrate a high prevalence of sensitization among users with suspected allergy. In a 2019 Finnish study of 6567 patients using an isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor, 63 were patch tested for suspected ACD.6 Of these 63 patients, 51 (81%) had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum. These findings were consistent with the original 2017 study from Belgium and Sweden, in which 10 of 11 (91%) patients who used an isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor and had suspected contact allergy had positive patch test reactions to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum compared to no positive reactions in the 14 control patients.5 Given that there are more than 1.5 million users of this isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor across 46 countries,7 it requires no stretch of the imagination to understand why investigators refer to isobornyl acrylate allergy as an epidemic, even if only a small percentage of users are sensitized to the device.

The Journey to Discover Isobornyl Acrylate as a Culprit Allergen

Similar to the discoveries of radiography and penicillin, the discovery of isobornyl acrylate as a culprit allergen in a modern glucose sensor was purely accidental. In 2016, a 9-year-old boy with diabetes presented to a Belgian dermatology department with ACD to a glucose sensor.1 A patch test nurse serendipitously applied isobornyl acrylate—0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% in petrolatum—which was not intended to be applied as part of the typical acrylate series. The only positive patch test reactions in this patient were to isobornyl acrylate at all 3 concentrations. This lucky error inspired isobornyl acrylate to be tested at multiple other dermatology departments in Europe in patients with ACD to their glucose sensors, leading to its discovery as a culprit allergen.1

One challenge facing investigators was obtaining information and materials from the diabetic device industry. Medical device manufacturers are not required to disclose chemicals present in a device on its label.8 Therefore, for patients or investigators to determine whether a potential allergen is present in a given device, they must request that information from the manufacturer, which can be a time-consuming and frustrating effort. Luckily, investigators collaborated with one another, and Belgian investigators suggested that Swedish investigators performing chemical analyses on a glucose monitoring device should focus on isobornyl acrylate, which enabled its detection in an extract from the device.5

Testing for Isobornyl Acrylate Allergy in Your Clinic

Patients with suspected ACD to a diabetic device—insulin pump or glucose sensor—should be patch tested with isobornyl acrylate, in addition to other previously reported allergens. The vehicle typically is petrolatum, and the commonly tested concentration is 0.1%. Testing with lower concentrations such as 0.01% can result in false-negative reactions,9 and testing at higher concentrations such as 0.3% can result in irritant skin reactions.2 Isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum currently is available from one commercial allergen supplier (Chemotechnique Diagnostics). A positive patch test reaction to isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is shown in the Figure.

Management of Diabetic Device ACD

For patients with diabetic device ACD, there are several strategies that can reduce direct contact between the device and the patient’s skin. Methods that have been tried with varying success to allow patients to continue using their glucose sensors include barrier sprays (eg, Cavilon [3M], Silesse Skin Barrier [ConvaTec]); barrier pads (eg, Compeed [HRA Pharma], Surround skin protectors [Eakin], DuoDERM dressings [ConvaTec], Tegaderm dressings [3M]); and topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors. Nevertheless, a 2019 Finnish study showed that only 14 of 63 (22%) patients with ACD to their isobornyl acrylate–containing glucose sensor were able to continue using the device, with all 14 requiring use of a barrier agent. Despite using the barrier agent, 13 (93%) of these patients had residual dermatitis.6 There also is concern that use of barrier methods might hamper the proper functioning of glucose sensors and related devices.

Patients with known isobornyl acrylate contact allergy also may switch to a different diabetic device. A 2019 German study showed that in 5 patients with isobornyl acrylate ACD, none had reactions to the one particular system that has been shown by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to not contain isobornyl acrylate.10 However, as a word of caution, the same device also has been associated with ACD11,12 but has been resolved by using heat staking during the production process.13 As manufacturers update device components, identification of other isobornyl acrylate–free devices may require a degree of trial and error, as neither isobornyl acrylate nor any other potential allergen is listed on device labels.

Final Interpretation

Isobornyl acrylate is not a common sensitizer in general patch test populations but is a recently identified major culprit in ACD to diabetic devices. Patch testing with isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum is not necessary in standard screening panels but should be considered in patients with suspected ACD to glucose sensors or insulin pumps. If a patient with ACD wants to continue to experience the convenience provided by a diabetic device, options include using topical steroids or barrier agents and/or changing the brand of the diabetic device, though none of these methods are foolproof. Hopefully, the identification of isobornyl acrylate as a culprit allergen will help to improve the lives of patients who use diabetic devices worldwide.

- Aerts O, Herman A, Mowitz M, et al. Isobornyl acrylate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:4-12.

- Christoffers WA, Coenraads PJ, Schuttelaar ML. Two decades of occupational (meth)acrylate patch test results and focus on isobornyl acrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;69:86-92.

- Pickup JC, Freeman SC, Sutton AJ. Glycaemic control in type 1 diabetes during real time continuous glucose monitoring compared with self monitoring of blood glucose: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials using individual patient data. BMJ. 2011;343:d3805.

- Busschots AM, Meuleman V, Poesen N, et al. Contact allergy to components of glue in insulin pump infusion sets. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:205-206.

- Herman A, Aerts O, Baeck M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in Freestyle® Libre, a newly introduced glucose sensor. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:367-373.

- Hyry HSI, Liippo JP, Virtanen HM. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by glucose sensors in type 1 diabetes patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:161-166.

- Abbott’s Revolutionary FreeStyle® Libre system now reimbursed in the two largest provinces in Canada [press release]. Abbott Park, IL: Abbott; September 13, 2019. https://abbott.mediaroom.com/2019-09-13-Abbotts-Revolutionary-FreeStyle-R-Libre-System-Now-Reimbursed-in-the-Two-Largest-Provinces-in-Canada. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- Herman A, Goossens A. The need to disclose the composition of medical devices at the European level. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:159-160.

- Raison-Peyron N, Mowitz M, Bonardel N, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in OmniPod, an innovative tubeless insulin pump. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:76-80.

- Oppel E, Kamann S, Reichl FX, et al. The Dexcom glucose monitoring system—an isobornyl acrylate-free alternative for diabetic patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:32-36.

- Peeters C, Herman A, Goossens A, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by 2-ethyl cyanoacrylate contained in glucose sensor sets in two diabetic adults. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:426-429.

- Aschenbeck KA, Hylwa SA. A diabetic’s allergy: ethyl cyanoacrylate in glucose sensor adhesive. Dermatitis. 2017;28:289-291.

- Gisin V, Chan A, Welsh B. Manufacturing process changes and reduced skin irritations of an adhesive patch used for continuous glucose monitoring devices. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12:725-726.

- Aerts O, Herman A, Mowitz M, et al. Isobornyl acrylate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:4-12.

- Christoffers WA, Coenraads PJ, Schuttelaar ML. Two decades of occupational (meth)acrylate patch test results and focus on isobornyl acrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;69:86-92.

- Pickup JC, Freeman SC, Sutton AJ. Glycaemic control in type 1 diabetes during real time continuous glucose monitoring compared with self monitoring of blood glucose: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials using individual patient data. BMJ. 2011;343:d3805.

- Busschots AM, Meuleman V, Poesen N, et al. Contact allergy to components of glue in insulin pump infusion sets. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:205-206.

- Herman A, Aerts O, Baeck M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in Freestyle® Libre, a newly introduced glucose sensor. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:367-373.

- Hyry HSI, Liippo JP, Virtanen HM. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by glucose sensors in type 1 diabetes patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:161-166.

- Abbott’s Revolutionary FreeStyle® Libre system now reimbursed in the two largest provinces in Canada [press release]. Abbott Park, IL: Abbott; September 13, 2019. https://abbott.mediaroom.com/2019-09-13-Abbotts-Revolutionary-FreeStyle-R-Libre-System-Now-Reimbursed-in-the-Two-Largest-Provinces-in-Canada. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- Herman A, Goossens A. The need to disclose the composition of medical devices at the European level. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:159-160.

- Raison-Peyron N, Mowitz M, Bonardel N, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in OmniPod, an innovative tubeless insulin pump. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:76-80.

- Oppel E, Kamann S, Reichl FX, et al. The Dexcom glucose monitoring system—an isobornyl acrylate-free alternative for diabetic patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:32-36.

- Peeters C, Herman A, Goossens A, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by 2-ethyl cyanoacrylate contained in glucose sensor sets in two diabetic adults. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:426-429.

- Aschenbeck KA, Hylwa SA. A diabetic’s allergy: ethyl cyanoacrylate in glucose sensor adhesive. Dermatitis. 2017;28:289-291.

- Gisin V, Chan A, Welsh B. Manufacturing process changes and reduced skin irritations of an adhesive patch used for continuous glucose monitoring devices. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12:725-726.

Practice Points

- In patients with suspected allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to a diabetic device, patch testing with isobornyl acrylate 0.1% in petrolatum should be considered.

- If patients with ACD to their diabetic device want to continue using the device, options include utilizing topical steroids or barrier agents and/or changing the brand of the diabetic device, though these steps may not be effective for every patient.

Hand Hygiene in Preventing COVID-19 Transmission

Handwashing with antimicrobial soaps or alcohol-based sanitizers is an effective measure in preventing microbial disease transmission. In the context of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) prevention, the World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have recommended handwashing with soap and water after coughing/sneezing, visiting a public place, touching surfaces outside the home, and taking care of a sick person(s), as well as before and after eating. When soap and water are not available, alcohol-based sanitizers may be used.1,2

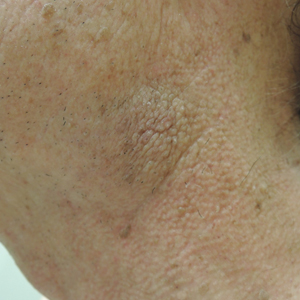

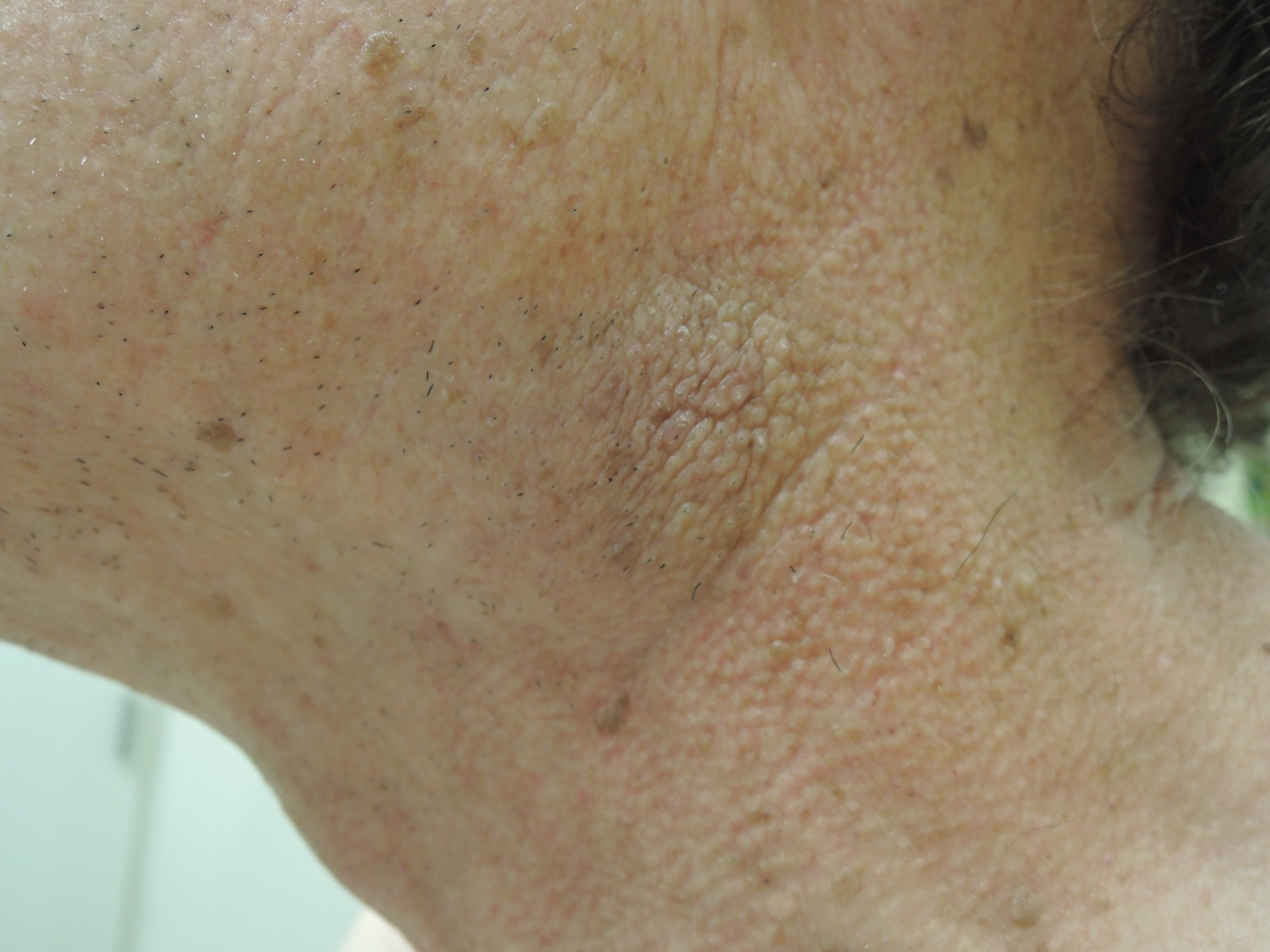

Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) is most commonly associated with wet work and is frequently seen in health care workers in relation to hand hygiene, with survey-based studies reporting 25% to 55% of nurses affected.3-5 In a prospective study (N=102), health care workers who washed their hands more than 10 times per day were55% more likely to develop hand dermatitis.6 Frequent ICD of the hands has been reported in Chinese health care workers in association with COVID-19.7 Handwashing and/or glove wearing may be newly prioritized by workers who handle frequently touched goods and surfaces, such as flight attendants (Figure). Patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder may be another vulnerable population.8

Alcohol-based sanitizers and detergents or antimicrobials in soaps may cause ICD of the hands by denaturation of stratum corneum proteins, depletion of intercellular lipids, and decreased corneocyte cohesion. These agents alter the skin flora, with increased colonization by staphylococci and gram-negative bacilli.9 Clinical findings include xerosis, scaling, fissuring, and bleeding. Physicians may evaluate severity of ICD of the hands using the

Cleansing the hands with alcohol-based sanitizers has consistently shown equivalent or greater efficacy than antimicrobial soaps for eradication of most microbes, with exception of bacterial spores and protozoan oocysts.11 In an in vivo experiment, 70% ethanol solution was more effective in eradicating rotavirus from the fingerpads of adults than 10% povidone-iodine solution, nonmedicated soaps, and soaps containing chloroxylenol 4.8% or chlorhexidine gluconate 4%.12 Coronavirus disease 2019 is a lipophilic enveloped virus. The lipid-dissolving effects of alcohol-based sanitizers is especially effective against these kinds of viruses. An in vitro experiment showed that alcohol solutions are effective against enveloped viruses including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Ebola virus, and Zika virus.13 There are limited data for the virucidal efficacy of non–alcohol-based sanitizers containing quaternary ammonium compounds (most commonly benzalkonium chloride) and therefore they are not recommended for protection against COVID-19. Handwashing is preferred over alcohol-based solutions when hands are visibly dirty.

Alcohol-based sanitizers typically are less likely to cause ICD than handwashing with detergent-based or antimicrobial soaps. Antimicrobial ingredients in soaps such as chlorhexidine, chloroxylenol, and triclosan are frequent culprits.11 Detergents in soap such as sodium laureth sulfate cause more skin irritation and transepidermal water loss than alcohol14; however, among health care workers, alcohol-based sanitizers often are perceived as more damaging to the skin.15 During the 2014 Ebola outbreak, use of alcohol-based sanitizers vs handwashing resulted in lower hand eczema severity index scores (n=108).16

Propensity for ICD is a limiting factor in hand hygiene adherence.17 In a double-blind randomized trial (N=54), scheduled use of an oil-containing lotion was shown to increase compliance with hand hygiene protocols in health care workers by preventing cracks, scaling, and pain.18 Using sanitizers containing humectants (eg, aloe vera gel) or moisturizers with petrolatum, liquid paraffin, glycerin, or mineral oil have all been shown to decrease the incidence of ICD in frequent handwashers.19,20 Thorough hand drying also is important in preventing dermatitis. Drying with disposable paper towels is preferred over automated air dryers to prevent aerosolization of microbes.21 Because latex has been implicated in development of ICD, use of latex-free gloves is recommended.22

Alcohol-based sanitizer is not only an effective virucidal agent but also is less likely to cause ICD, therefore promoting hand hygiene adherence. Handwashing with soap still is necessary when hands are visibly dirty but should be performed less frequently if feasible. Hand hygiene and emollient usage education is important for physicians and patients alike, particularly during the COVID-19 crisis.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019. how to protect yourself & others. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prepare/prevention.html. Updated April 13, 2020. Accessed April 21, 2020.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public. Updated March 31, 2020. Accessed April 21, 2020.

- Carøe TK, Ebbehøj NE, Bonde JPE, et al. Hand eczema and wet work: dose-response relationship and effect of leaving the profession. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:341-347.

- Larson E, Friedman C, Cohran J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of skin damage on the hands of nurses. Heart Lung. 1997;26:404-412.

- Lampel HP, Patel N, Boyse K, et al. Prevalence of hand dermatitis in inpatient nurses at a United States hospital. Dermatitis. 2007;18:140-142.

- Callahan A, Baron E, Fekedulegn D, et al. Winter season, frequent hand washing, and irritant patch test reactions to detergents are associated with hand dermatitis in health care workers. Dermatitis. 2013;24:170-175.

- Lan J, Song Z, Miao X, et al. Skin damage among healthcare workers managing coronavirus disease-2019 [published online March 18, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1215-1216.

- Katz RJ, Landau P, DeVeaugh-Geiss J, et al. Pharmacological responsiveness of dermatitis secondary to compulsive washing. Psychiatry Res. 1990;34:223-226.

- Larson EL, Hughes CA, Pyrek JD, et al. Changes in bacterial flora associated with skin damage on hands of health care personnel. Am J Infect Control. 1998;26:513-521.

- Held E, Skoet R, Johansen JD, et al. The hand eczema severity index (HECSI): a scoring system for clinical assessment of hand eczema. a study of inter- and intraobserver reliability. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:302-307.

- Boyce JM, Pittet D, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, et al. Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health-Care Settings. Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HIPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Am J Infect Control. 2002;30:S1-S46.

- Ansari SA, Sattar SA, Springthorpe VS, et al. Invivo protocol for testing efficacy of hand-washing agents against viruses and bacteria—experiments with rotavirus and Escherichi coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:3113-3118.

- Siddharta A, Pfaender S, Vielle NJ, et al. virucidal activity of world health organization-recommended formulations against enveloped viruses, including Zika, Ebola, and emerging coronaviruses. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:902-906.

- Pedersen LK, Held E, Johansen JD, et al. Less skin irritation from alcohol-based disinfectant than from detergent used for hand disinfection. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1142-1146.

- Stutz N, Becker D, Jappe U, et al. Nurses’ perceptions of the benefits and adverse effects of hand disinfection: alcohol-based hand rubs vs. hygienic handwashing: a multicentre questionnaire study with additional patch testing by the German Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:565-572.

- Wolfe MK, Wells E, Mitro B, et al. Seeking clearer recommendations for hand hygiene in communities facing Ebola: a randomized trial investigating the impact of six handwashing methods on skin irritation and dermatitis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167378.

- Pittet D, Allegranzi B, Storr J. The WHO Clean Care is Safer Care programme: field-testing to enhance sustainability and spread of hand hygiene improvements. J Infect Public Health. 2008;1:4-10.

- McCormick RD, Buchman TL, Maki DG. Double-blind, randomized trial of scheduled use of a novel barrier cream and an oil-containing lotion for protecting the hands of health care workers. Am J Infect Control. 2000;28:302-310.

- Berndt U, Wigger-Alberti W, Gabard B, et al. Efficacy of a barrier cream and its vehicle as protective measures against occupational irritant contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:77-80.

- Kampf G, Ennen J. Regular use of a hand cream can attenuate skin dryness and roughness caused by frequent hand washing. BMC Dermatol. 2006;6:1.

- Gammon J, Hunt J. The neglected element of hand hygiene - significance of hand drying, efficiency of different methods, and clinical implication: a review. J Infect Prev. 2019;20:66-74.

- Elston DM. Letter from the editor: occupational skin disease among healthcare workers during the coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemic [published online March 18, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1085-1086.

Handwashing with antimicrobial soaps or alcohol-based sanitizers is an effective measure in preventing microbial disease transmission. In the context of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) prevention, the World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have recommended handwashing with soap and water after coughing/sneezing, visiting a public place, touching surfaces outside the home, and taking care of a sick person(s), as well as before and after eating. When soap and water are not available, alcohol-based sanitizers may be used.1,2

Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) is most commonly associated with wet work and is frequently seen in health care workers in relation to hand hygiene, with survey-based studies reporting 25% to 55% of nurses affected.3-5 In a prospective study (N=102), health care workers who washed their hands more than 10 times per day were55% more likely to develop hand dermatitis.6 Frequent ICD of the hands has been reported in Chinese health care workers in association with COVID-19.7 Handwashing and/or glove wearing may be newly prioritized by workers who handle frequently touched goods and surfaces, such as flight attendants (Figure). Patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder may be another vulnerable population.8