User login

Racial disparities in colon cancer survival mainly driven by tumor stage at presentation

Although black patients with colon cancer received significantly less treatment than white patients, particularly for late stage disease, much of the overall survival disparity between black and white patients was explained by tumor presentation at diagnosis rather than treatment differences, according to an analysis of SEER data.

Among demographically matched black and white patients, the 5-year survival difference was 8.3% (P less than .0001). Presentation match reduced the difference to 5.0% (P less than .0001), which accounted for 39.8% of the overall disparity. Additional matching by treatment reduced the difference only slightly to 4.9% (P less than .0001), which accounted for 1.2% of the overall disparity. Black patients had lower rates for most treatments, including surgery, than presentation-matched white patients (88.5% vs. 91.4%), and these differences were most pronounced at advanced stages. For example, significant differences between black and white patients in the use of chemotherapy was observed for stage III (53.1% vs. 64.2%; P less than .0001) and stage IV (56.1% vs. 63.3%; P = .001).

“Our results indicate that tumor presentation, including tumor stage, is indeed one of the most important factors contributing to the racial disparity in colon cancer survival. We observed that, after controlling for demographic factors, black patients in comparison with white patients had a significantly higher proportion of stage IV and lower proportions of stages I and II disease. Adequately matching on tumor presentation variables (e.g., stage, grade, size, and comorbidity) significantly reduced survival disparities,” wrote Dr. Yinzhi Lai of the Department of Medical Oncology at Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center, Philadelphia, and colleagues (Gastroenterology. 2016 Apr 4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.030).

Treatment differences in advanced-stage patients, compared with early-stage patients, explained a higher proportion of the demographic-matched survival disparity. For example, in stage II patients, treatment match resulted in modest reductions in 2-, 3-, and 5-year survival rate disparities (2.7%-2.8%, 4.1%-3.6%, and 4.6%-4.0%, respectively); by contrast, in stage III patients, treatment match resulted in more substantial reductions in 2-, 3-, and 5-year survival rate disparities (4.5%-2.2%, 3.1%-2.0%, and 4.3%-2.8%, respectively). A similar effect was observed in patients with stage IV disease. The results suggest that, “to control survival disparity, more efforts may need to be tailored to minimize treatment disparities (especially chemotherapy use) in patients with advanced-stage disease,” the investigators wrote.

The retrospective data analysis used patient information from 68,141 patients (6,190 black, 61,951 white) aged 66 years and older with colon cancer identified from the National Cancer Institute SEER-Medicare database. Using a novel minimum distance matching strategy, investigators drew from the pool of white patients to match three distinct comparison cohorts to the same 6,190 black patients. Close matches between black and white patients bypassed the need for model-based analysis.

The primary matching analysis was limited by the inability to control for substantial differences in socioeconomic status, marital status, and urban/rural residence. A subcohort analysis of 2,000 matched black and white patients showed that when socioeconomic status was added to the demographic match, survival differences were reduced, indicating the important role of socioeconomic status on racial survival disparities.

Significantly better survival was observed in all patients who were diagnosed in 2004 or later, the year the Food and Drug Administration approved the important chemotherapy medicines oxaliplatin and bevacizumab. Separating the cohorts into those who were diagnosed before and after 2004 revealed that the racial survival disparity was lower in the more recent group, indicating a favorable impact of oxaliplatin and/or bevacizumab in reducing the survival disparity.

Prior studies have documented racial disparities in the incidence and outcomes of colon cancer in the United States. Black men and women have a higher overall incidence and more advanced stage of disease at diagnosis than white men and women, while being less likely to receive guideline-concordant treatment.

|

| Dr. Jennifer Lund |

To extend this work, the authors evaluated treatment disparities between black and white colon cancer patients aged 66 years and older and examined the impact of a variety of patient characteristics on racial disparities in overall survival using a novel, sequential matching algorithm that minimized the overall distance between black and white patients based on demographic-, tumor specific–, and treatment-related variables. The authors found that differences in overall survival were mainly driven by tumor presentation; however, advanced-stage black colon cancer patients received less guideline concordant-treatment than white patients. While this minimum-distance algorithm provided close black-white matches on prespecified factors, it could not accommodate other factors (for example, socioeconomic, marital, and urban/rural status); therefore, methodologic improvements to this method and comparisons to other commonly used approaches (that is, propensity score matching and weighting) are warranted.

Finally, these results apply to older black and white colon cancer patients with Medicare fee-for-service coverage only. Additional research using similar methods in older Medicare Advantage populations or younger adults may uncover unique drivers of overall survival disparities by race, which may require tailored interventions.

Jennifer L. Lund, Ph.D., is an assistant professor, department of epidemiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She receives research support from the UNC Oncology Clinical Translational Research Training Program (K12 CA120780), as well as through a Research Starter Award from the PhRMA Foundation to the UNC Department of Epidemiology.

Prior studies have documented racial disparities in the incidence and outcomes of colon cancer in the United States. Black men and women have a higher overall incidence and more advanced stage of disease at diagnosis than white men and women, while being less likely to receive guideline-concordant treatment.

|

| Dr. Jennifer Lund |

To extend this work, the authors evaluated treatment disparities between black and white colon cancer patients aged 66 years and older and examined the impact of a variety of patient characteristics on racial disparities in overall survival using a novel, sequential matching algorithm that minimized the overall distance between black and white patients based on demographic-, tumor specific–, and treatment-related variables. The authors found that differences in overall survival were mainly driven by tumor presentation; however, advanced-stage black colon cancer patients received less guideline concordant-treatment than white patients. While this minimum-distance algorithm provided close black-white matches on prespecified factors, it could not accommodate other factors (for example, socioeconomic, marital, and urban/rural status); therefore, methodologic improvements to this method and comparisons to other commonly used approaches (that is, propensity score matching and weighting) are warranted.

Finally, these results apply to older black and white colon cancer patients with Medicare fee-for-service coverage only. Additional research using similar methods in older Medicare Advantage populations or younger adults may uncover unique drivers of overall survival disparities by race, which may require tailored interventions.

Jennifer L. Lund, Ph.D., is an assistant professor, department of epidemiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She receives research support from the UNC Oncology Clinical Translational Research Training Program (K12 CA120780), as well as through a Research Starter Award from the PhRMA Foundation to the UNC Department of Epidemiology.

Prior studies have documented racial disparities in the incidence and outcomes of colon cancer in the United States. Black men and women have a higher overall incidence and more advanced stage of disease at diagnosis than white men and women, while being less likely to receive guideline-concordant treatment.

|

| Dr. Jennifer Lund |

To extend this work, the authors evaluated treatment disparities between black and white colon cancer patients aged 66 years and older and examined the impact of a variety of patient characteristics on racial disparities in overall survival using a novel, sequential matching algorithm that minimized the overall distance between black and white patients based on demographic-, tumor specific–, and treatment-related variables. The authors found that differences in overall survival were mainly driven by tumor presentation; however, advanced-stage black colon cancer patients received less guideline concordant-treatment than white patients. While this minimum-distance algorithm provided close black-white matches on prespecified factors, it could not accommodate other factors (for example, socioeconomic, marital, and urban/rural status); therefore, methodologic improvements to this method and comparisons to other commonly used approaches (that is, propensity score matching and weighting) are warranted.

Finally, these results apply to older black and white colon cancer patients with Medicare fee-for-service coverage only. Additional research using similar methods in older Medicare Advantage populations or younger adults may uncover unique drivers of overall survival disparities by race, which may require tailored interventions.

Jennifer L. Lund, Ph.D., is an assistant professor, department of epidemiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She receives research support from the UNC Oncology Clinical Translational Research Training Program (K12 CA120780), as well as through a Research Starter Award from the PhRMA Foundation to the UNC Department of Epidemiology.

Although black patients with colon cancer received significantly less treatment than white patients, particularly for late stage disease, much of the overall survival disparity between black and white patients was explained by tumor presentation at diagnosis rather than treatment differences, according to an analysis of SEER data.

Among demographically matched black and white patients, the 5-year survival difference was 8.3% (P less than .0001). Presentation match reduced the difference to 5.0% (P less than .0001), which accounted for 39.8% of the overall disparity. Additional matching by treatment reduced the difference only slightly to 4.9% (P less than .0001), which accounted for 1.2% of the overall disparity. Black patients had lower rates for most treatments, including surgery, than presentation-matched white patients (88.5% vs. 91.4%), and these differences were most pronounced at advanced stages. For example, significant differences between black and white patients in the use of chemotherapy was observed for stage III (53.1% vs. 64.2%; P less than .0001) and stage IV (56.1% vs. 63.3%; P = .001).

“Our results indicate that tumor presentation, including tumor stage, is indeed one of the most important factors contributing to the racial disparity in colon cancer survival. We observed that, after controlling for demographic factors, black patients in comparison with white patients had a significantly higher proportion of stage IV and lower proportions of stages I and II disease. Adequately matching on tumor presentation variables (e.g., stage, grade, size, and comorbidity) significantly reduced survival disparities,” wrote Dr. Yinzhi Lai of the Department of Medical Oncology at Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center, Philadelphia, and colleagues (Gastroenterology. 2016 Apr 4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.030).

Treatment differences in advanced-stage patients, compared with early-stage patients, explained a higher proportion of the demographic-matched survival disparity. For example, in stage II patients, treatment match resulted in modest reductions in 2-, 3-, and 5-year survival rate disparities (2.7%-2.8%, 4.1%-3.6%, and 4.6%-4.0%, respectively); by contrast, in stage III patients, treatment match resulted in more substantial reductions in 2-, 3-, and 5-year survival rate disparities (4.5%-2.2%, 3.1%-2.0%, and 4.3%-2.8%, respectively). A similar effect was observed in patients with stage IV disease. The results suggest that, “to control survival disparity, more efforts may need to be tailored to minimize treatment disparities (especially chemotherapy use) in patients with advanced-stage disease,” the investigators wrote.

The retrospective data analysis used patient information from 68,141 patients (6,190 black, 61,951 white) aged 66 years and older with colon cancer identified from the National Cancer Institute SEER-Medicare database. Using a novel minimum distance matching strategy, investigators drew from the pool of white patients to match three distinct comparison cohorts to the same 6,190 black patients. Close matches between black and white patients bypassed the need for model-based analysis.

The primary matching analysis was limited by the inability to control for substantial differences in socioeconomic status, marital status, and urban/rural residence. A subcohort analysis of 2,000 matched black and white patients showed that when socioeconomic status was added to the demographic match, survival differences were reduced, indicating the important role of socioeconomic status on racial survival disparities.

Significantly better survival was observed in all patients who were diagnosed in 2004 or later, the year the Food and Drug Administration approved the important chemotherapy medicines oxaliplatin and bevacizumab. Separating the cohorts into those who were diagnosed before and after 2004 revealed that the racial survival disparity was lower in the more recent group, indicating a favorable impact of oxaliplatin and/or bevacizumab in reducing the survival disparity.

Although black patients with colon cancer received significantly less treatment than white patients, particularly for late stage disease, much of the overall survival disparity between black and white patients was explained by tumor presentation at diagnosis rather than treatment differences, according to an analysis of SEER data.

Among demographically matched black and white patients, the 5-year survival difference was 8.3% (P less than .0001). Presentation match reduced the difference to 5.0% (P less than .0001), which accounted for 39.8% of the overall disparity. Additional matching by treatment reduced the difference only slightly to 4.9% (P less than .0001), which accounted for 1.2% of the overall disparity. Black patients had lower rates for most treatments, including surgery, than presentation-matched white patients (88.5% vs. 91.4%), and these differences were most pronounced at advanced stages. For example, significant differences between black and white patients in the use of chemotherapy was observed for stage III (53.1% vs. 64.2%; P less than .0001) and stage IV (56.1% vs. 63.3%; P = .001).

“Our results indicate that tumor presentation, including tumor stage, is indeed one of the most important factors contributing to the racial disparity in colon cancer survival. We observed that, after controlling for demographic factors, black patients in comparison with white patients had a significantly higher proportion of stage IV and lower proportions of stages I and II disease. Adequately matching on tumor presentation variables (e.g., stage, grade, size, and comorbidity) significantly reduced survival disparities,” wrote Dr. Yinzhi Lai of the Department of Medical Oncology at Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center, Philadelphia, and colleagues (Gastroenterology. 2016 Apr 4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.030).

Treatment differences in advanced-stage patients, compared with early-stage patients, explained a higher proportion of the demographic-matched survival disparity. For example, in stage II patients, treatment match resulted in modest reductions in 2-, 3-, and 5-year survival rate disparities (2.7%-2.8%, 4.1%-3.6%, and 4.6%-4.0%, respectively); by contrast, in stage III patients, treatment match resulted in more substantial reductions in 2-, 3-, and 5-year survival rate disparities (4.5%-2.2%, 3.1%-2.0%, and 4.3%-2.8%, respectively). A similar effect was observed in patients with stage IV disease. The results suggest that, “to control survival disparity, more efforts may need to be tailored to minimize treatment disparities (especially chemotherapy use) in patients with advanced-stage disease,” the investigators wrote.

The retrospective data analysis used patient information from 68,141 patients (6,190 black, 61,951 white) aged 66 years and older with colon cancer identified from the National Cancer Institute SEER-Medicare database. Using a novel minimum distance matching strategy, investigators drew from the pool of white patients to match three distinct comparison cohorts to the same 6,190 black patients. Close matches between black and white patients bypassed the need for model-based analysis.

The primary matching analysis was limited by the inability to control for substantial differences in socioeconomic status, marital status, and urban/rural residence. A subcohort analysis of 2,000 matched black and white patients showed that when socioeconomic status was added to the demographic match, survival differences were reduced, indicating the important role of socioeconomic status on racial survival disparities.

Significantly better survival was observed in all patients who were diagnosed in 2004 or later, the year the Food and Drug Administration approved the important chemotherapy medicines oxaliplatin and bevacizumab. Separating the cohorts into those who were diagnosed before and after 2004 revealed that the racial survival disparity was lower in the more recent group, indicating a favorable impact of oxaliplatin and/or bevacizumab in reducing the survival disparity.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Tumor stage at diagnosis had a greater effect on survival disparities between black and white patients with colon cancer than treatment differences.

Major finding: Among demographically matched black and white patients, the 5-year survival difference was 8.3% (P less than .0001); matching by presentation reduced the difference to 5.0% (P less than .0001), and additional matching by treatment reduced the difference only slightly to 4.9% (P less than .0001).

Data sources: In total, 68,141 patients (6,190 black, 61,951 white) aged 66 years and older with colon cancer were identified from the National Cancer Institute SEER-Medicare database. Three white comparison cohorts were assembled and matched to the same 6,190 black patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Lai and coauthors reported having no disclosures.

Thromboprophylaxis efficacy similar before and after colorectal surgery

CHICAGO – Lower extremity duplex scans should be performed prior to colorectal surgery, and anticoagulation should be tailored to the result, findings from a randomized clinical trial suggest.

The findings also raise questions about the fairness of financial penalties imposed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for perioperative venous thromboembolism, Dr. Karen Zaghiyan of Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

In 376 consecutive adult patients undergoing laparoscopic or open major colorectal surgery who had no occult preoperative deep vein thrombosis (DVT) on lower extremity venous duplex scan and who were randomized to preoperative or postoperative chemical thromboprophylaxis (CTP) with 5,000 U of subcutaneous heparin, no differences were seen with respect to the primary outcome of venous thromboembolism within 48 hours of surgery, Dr. Zaghiyan said.

“There was no significant difference in our primary outcome – early postoperative VTE [venous thromboembolism] – in patients managed with postoperative or preoperative prophylaxis,” she said, noting that three patients in each group developed asymptomatic intraoperative DVT, and two additional patients in the postoperative treatment group developed asymptomatic DVT between postoperative day 0 and 2.

Two additional patients in the postoperative treatment group developed clinically significant DVT between postoperative day 2 and 30.

“Both patients had a complicated prolonged hospital course, and developed DVT while still hospitalized. This difference still did not reach statistical significance, and there were no post-discharge DVT or PEs [pulmonary embolisms] in the entire cohort,” she said.

Bleeding complications, including estimated blood loss and number receiving transfusion, were similar in the two groups, she said, noting that no patients developed heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and that hospital stay, readmissions, and overall complications were similar between the two groups.

Study subjects had a mean age of 53 years, and 52% were women. The preoperative- and postoperative treatment groups were similar with respect to demographics and preoperative characteristics. They underwent lower extremity venous duplex just prior to surgery, immediately after surgery in the recovery room, on day 2 after surgery, and subsequently as clinically indicated.

Thromboprophylaxis in the preoperative treatment group was given in the “pre-op holding area” then 8 hours after surgery and every 8 hours thereafter until discharge. Thromboprophylaxis in the postoperative treatment group was given within 24 hours after surgery, and then every 8 hours until discharge.

Preoperative and postoperative CTP were equally safe and effective, and since occult preoperative DVT is twice as common as postoperative DVT, occurring in a surprising 4% of patients in this study, the findings support preoperative scans and anticoagulation based on the results – especially in older patients and those with comorbid disease, Dr. Zaghiyan said.

The findings could help improve patients care; although VTE prevention and chemical prophylaxis in colorectal surgery have been extensively studied, current guidelines are vague, with both the American College of Chest Physicians and the Surgical Care Improvement Project recommending that prophylaxis be initiated 24 hours prior to or after major colorectal surgery, she said.

The findings could also help avoid CMS penalties for postoperatively identified VTE,” she added.

Further, those penalties may not be supported by the clinical data; in this study, the majority of early postoperative DVTs were unpreventable, with no additional protection provided with preoperative prophylaxis, she explained.

“CMS should reevaluate the financial penalties, taking preventability into account,” she said.

Dr. Zaghiyan reported having no disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this presentation is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

CHICAGO – Lower extremity duplex scans should be performed prior to colorectal surgery, and anticoagulation should be tailored to the result, findings from a randomized clinical trial suggest.

The findings also raise questions about the fairness of financial penalties imposed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for perioperative venous thromboembolism, Dr. Karen Zaghiyan of Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

In 376 consecutive adult patients undergoing laparoscopic or open major colorectal surgery who had no occult preoperative deep vein thrombosis (DVT) on lower extremity venous duplex scan and who were randomized to preoperative or postoperative chemical thromboprophylaxis (CTP) with 5,000 U of subcutaneous heparin, no differences were seen with respect to the primary outcome of venous thromboembolism within 48 hours of surgery, Dr. Zaghiyan said.

“There was no significant difference in our primary outcome – early postoperative VTE [venous thromboembolism] – in patients managed with postoperative or preoperative prophylaxis,” she said, noting that three patients in each group developed asymptomatic intraoperative DVT, and two additional patients in the postoperative treatment group developed asymptomatic DVT between postoperative day 0 and 2.

Two additional patients in the postoperative treatment group developed clinically significant DVT between postoperative day 2 and 30.

“Both patients had a complicated prolonged hospital course, and developed DVT while still hospitalized. This difference still did not reach statistical significance, and there were no post-discharge DVT or PEs [pulmonary embolisms] in the entire cohort,” she said.

Bleeding complications, including estimated blood loss and number receiving transfusion, were similar in the two groups, she said, noting that no patients developed heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and that hospital stay, readmissions, and overall complications were similar between the two groups.

Study subjects had a mean age of 53 years, and 52% were women. The preoperative- and postoperative treatment groups were similar with respect to demographics and preoperative characteristics. They underwent lower extremity venous duplex just prior to surgery, immediately after surgery in the recovery room, on day 2 after surgery, and subsequently as clinically indicated.

Thromboprophylaxis in the preoperative treatment group was given in the “pre-op holding area” then 8 hours after surgery and every 8 hours thereafter until discharge. Thromboprophylaxis in the postoperative treatment group was given within 24 hours after surgery, and then every 8 hours until discharge.

Preoperative and postoperative CTP were equally safe and effective, and since occult preoperative DVT is twice as common as postoperative DVT, occurring in a surprising 4% of patients in this study, the findings support preoperative scans and anticoagulation based on the results – especially in older patients and those with comorbid disease, Dr. Zaghiyan said.

The findings could help improve patients care; although VTE prevention and chemical prophylaxis in colorectal surgery have been extensively studied, current guidelines are vague, with both the American College of Chest Physicians and the Surgical Care Improvement Project recommending that prophylaxis be initiated 24 hours prior to or after major colorectal surgery, she said.

The findings could also help avoid CMS penalties for postoperatively identified VTE,” she added.

Further, those penalties may not be supported by the clinical data; in this study, the majority of early postoperative DVTs were unpreventable, with no additional protection provided with preoperative prophylaxis, she explained.

“CMS should reevaluate the financial penalties, taking preventability into account,” she said.

Dr. Zaghiyan reported having no disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this presentation is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

CHICAGO – Lower extremity duplex scans should be performed prior to colorectal surgery, and anticoagulation should be tailored to the result, findings from a randomized clinical trial suggest.

The findings also raise questions about the fairness of financial penalties imposed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for perioperative venous thromboembolism, Dr. Karen Zaghiyan of Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

In 376 consecutive adult patients undergoing laparoscopic or open major colorectal surgery who had no occult preoperative deep vein thrombosis (DVT) on lower extremity venous duplex scan and who were randomized to preoperative or postoperative chemical thromboprophylaxis (CTP) with 5,000 U of subcutaneous heparin, no differences were seen with respect to the primary outcome of venous thromboembolism within 48 hours of surgery, Dr. Zaghiyan said.

“There was no significant difference in our primary outcome – early postoperative VTE [venous thromboembolism] – in patients managed with postoperative or preoperative prophylaxis,” she said, noting that three patients in each group developed asymptomatic intraoperative DVT, and two additional patients in the postoperative treatment group developed asymptomatic DVT between postoperative day 0 and 2.

Two additional patients in the postoperative treatment group developed clinically significant DVT between postoperative day 2 and 30.

“Both patients had a complicated prolonged hospital course, and developed DVT while still hospitalized. This difference still did not reach statistical significance, and there were no post-discharge DVT or PEs [pulmonary embolisms] in the entire cohort,” she said.

Bleeding complications, including estimated blood loss and number receiving transfusion, were similar in the two groups, she said, noting that no patients developed heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and that hospital stay, readmissions, and overall complications were similar between the two groups.

Study subjects had a mean age of 53 years, and 52% were women. The preoperative- and postoperative treatment groups were similar with respect to demographics and preoperative characteristics. They underwent lower extremity venous duplex just prior to surgery, immediately after surgery in the recovery room, on day 2 after surgery, and subsequently as clinically indicated.

Thromboprophylaxis in the preoperative treatment group was given in the “pre-op holding area” then 8 hours after surgery and every 8 hours thereafter until discharge. Thromboprophylaxis in the postoperative treatment group was given within 24 hours after surgery, and then every 8 hours until discharge.

Preoperative and postoperative CTP were equally safe and effective, and since occult preoperative DVT is twice as common as postoperative DVT, occurring in a surprising 4% of patients in this study, the findings support preoperative scans and anticoagulation based on the results – especially in older patients and those with comorbid disease, Dr. Zaghiyan said.

The findings could help improve patients care; although VTE prevention and chemical prophylaxis in colorectal surgery have been extensively studied, current guidelines are vague, with both the American College of Chest Physicians and the Surgical Care Improvement Project recommending that prophylaxis be initiated 24 hours prior to or after major colorectal surgery, she said.

The findings could also help avoid CMS penalties for postoperatively identified VTE,” she added.

Further, those penalties may not be supported by the clinical data; in this study, the majority of early postoperative DVTs were unpreventable, with no additional protection provided with preoperative prophylaxis, she explained.

“CMS should reevaluate the financial penalties, taking preventability into account,” she said.

Dr. Zaghiyan reported having no disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this presentation is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Lower extremity duplex scans should be performed prior to colorectal surgery, and anticoagulation should be tailored to the result, findings from a randomized clinical trial suggest.

Major finding: No differences were seen with respect to the primary outcome of venous thromboembolism within 48 hours of surgery in patients treated with pre- or post-operative chemical thromboprophylaxis.

Data source: A randomized clinical trial of 376 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Zaghiyan reported having no disclosures.

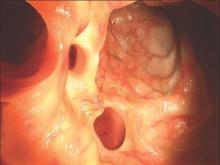

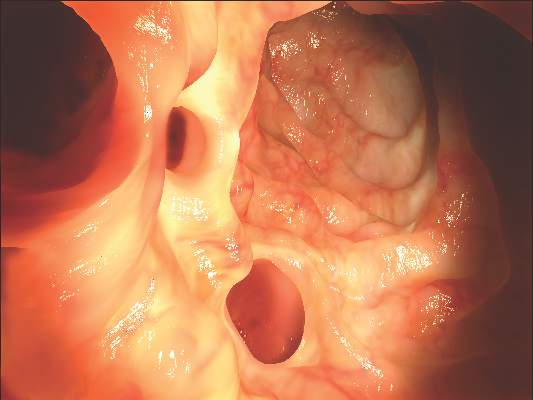

VIDEO: Anesthesia services during colonoscopy increase risk of near-term complications

Receiving anesthesia services while undergoing a colonoscopy may not be in your patients’ best interest, as doing so could significantly increase the likelihood of patients experiencing serious complications within 30 days of the procedure.

This is according to a new study published in the April issue of Gastroenterology, in which Dr. Karen J. Wernli and her coinvestigators analyzed claims data, collected from the Truven Health MarketScan Research Database, related to 3,168,228 colonoscopy procedures that took place between 2008 and 2011, to determine whether patients who received anesthesia were at a higher risk of developing complications after the procedure (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.018).

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

“The involvement of anesthesia services for colonoscopy sedation, mainly to administer propofol, has increased accordingly, from 11.0% of colonoscopies in 2001 to 23.4% in 2006, with projections of more than 50% in 2015,” wrote Dr. Wernli of the Group Health Research Institute in Seattle, and her coauthors. “Whether the use of propofol is associated with higher rates of short-term complications compared with standard sedation is not well understood.”

Men and women whose data was included in the study were between 40 and 64 years of age; men accounted for 46.8% of those receiving standard sedation (53.2% women) and 46.5% of those receiving anesthesia services (53.5% women). A total of 4,939,993 individuals were initially screened for enrollment, with 39,784 excluded because of a previous colorectal cancer diagnosis, 240,038 for “noncancer exclusions,” and 1,491,943 for being enrolled in the study less than 1 year.

Standard sedation was done in 2,079,784 (65.6%) of the procedures included in the study, while the other 1,088,444 (34.4%) colonoscopies involved anesthesia services. Use of anesthesia services resulted in a 13% increase in likelihood for patients to experience some kind of complication within 30 days of colonoscopy (95% confidence interval, 1.12-1.14). The most common complications were perforation (odds ratio, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.00-1.15), hemorrhage (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.27-1.30), abdominal pain (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.05-1.08), complications secondary to anesthesia (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.05-1.28), and “stroke and other central nervous system events” (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08).

Analysis of geographic distribution of colonoscopies performed with and without anesthesia services showed that all areas of the United States had a higher likelihood of postcolonoscopy complications associated with anesthesia except in the Southeast, where there was no association between the two. Additionally, in the western U.S., use of anesthesia services was less common than in any other geographic area, but was associated with a staggering 60% higher chance of complication within 30 days for patients who did opt for it.

“Although the use of anesthesia agents can directly impact colonoscopy outcomes, it is not solely the anesthesia agent that could lead to additional complications,” the study authors wrote. “In the absence of patient feedback, increased colonic-wall tension from colonoscopy pressure may not be identified by the endoscopist, and, consistent with our results, could lead to increased risks of colonic complications, such as perforation and abdominal pain.”

Dr. Wernli and her coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

We are approaching a time when half of all colonoscopies are performed with anesthesia assistance, most using propofol. Undeniably, some patients require anesthesia support for medical reasons, or because they do not sedate adequately with opiate-benzodiazepine combinations endoscopists can administer. The popularity of propofol-based anesthesia for routine colonoscopy, however, is based on several perceived benefits: patient demand for a discomfort-free procedure, rapid sedation followed by quick recovery, and good reimbursement for the anesthesia service itself, added to the benefits of faster overall procedure turnaround time. And presently, there is no disincentive — financial or otherwise — to continuing or expanding this practice. Colonoscopy with anesthesia looks like a win-win for both patient and endoscopist, as long as the added cost of anesthesia can be justified.

However, while anesthesia-assisted colonoscopy appears to possess several advantages, growing evidence suggests that a lower risk of complications is not one of them.

A smaller study (165,000 colonoscopies) using NCI SEER registry data suggested that adding anesthesia to colonoscopy may increase some adverse events. Cooper et al. (JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:551-6) showed an increase in overall complications and, specifically, aspiration, although not in technical complications of colonoscopy, including perforation and splenic rupture. However, this study did not include patients who underwent polypectomy. Wernli, et al. now show evidence derived from over 3 million patients demonstrating that adding anesthesia to colonoscopy increases complications significantly — not only aspiration, but also technical aspects of colonoscopy, including perforation, bleeding, and abdominal pain.

Colonoscopy is extremely safe, so complications are infrequent. Thus, data sets of colonoscopy complications large enough to be statistically meaningful for studies of this type require an extraordinarily large patient pool. For this prospective, observational cohort study, the authors obtained the large sample size by mining administrative claims data for 3 years, not through examining clinical data. As a result, several assumptions were made. These 3 million colonoscopies represented all indications — not just colorectal cancer screening. Billing claims for anesthesia represented surrogate markers for administration of propofol-based anesthesia. While anesthesia assistance was associated with increased risk of perforation, hemorrhage, abdominal pain, anesthesia complications, and stroke; risk of perforation associated with anesthesia was increased only in patients who underwent polypectomy.

Study methodology and confounding variables aside, it is hard to ignore the core message here: a large body of data analyzed rigorously demonstrate that anesthesia support for colonoscopy increases risk of procedure-related complications.

Patients who are ill, have certain cardiopulmonary issues, or do not sedate adequately with moderate sedation benefit from anesthesia assistance for colonoscopy. But for patients undergoing routine colonoscopy, without such issues, who could safely undergo colonoscopy under moderate sedation without unreasonable discomfort, we must now ask ourselves and discuss with our patients honestly, not only whether the added cost of anesthesia is reasonable — but also whether the apparent added risk of anesthesia justifies perceived benefits.

Dr. John A. Martin is senior associate consultant and associate professor, associate chair for endoscopy, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

We are approaching a time when half of all colonoscopies are performed with anesthesia assistance, most using propofol. Undeniably, some patients require anesthesia support for medical reasons, or because they do not sedate adequately with opiate-benzodiazepine combinations endoscopists can administer. The popularity of propofol-based anesthesia for routine colonoscopy, however, is based on several perceived benefits: patient demand for a discomfort-free procedure, rapid sedation followed by quick recovery, and good reimbursement for the anesthesia service itself, added to the benefits of faster overall procedure turnaround time. And presently, there is no disincentive — financial or otherwise — to continuing or expanding this practice. Colonoscopy with anesthesia looks like a win-win for both patient and endoscopist, as long as the added cost of anesthesia can be justified.

However, while anesthesia-assisted colonoscopy appears to possess several advantages, growing evidence suggests that a lower risk of complications is not one of them.

A smaller study (165,000 colonoscopies) using NCI SEER registry data suggested that adding anesthesia to colonoscopy may increase some adverse events. Cooper et al. (JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:551-6) showed an increase in overall complications and, specifically, aspiration, although not in technical complications of colonoscopy, including perforation and splenic rupture. However, this study did not include patients who underwent polypectomy. Wernli, et al. now show evidence derived from over 3 million patients demonstrating that adding anesthesia to colonoscopy increases complications significantly — not only aspiration, but also technical aspects of colonoscopy, including perforation, bleeding, and abdominal pain.

Colonoscopy is extremely safe, so complications are infrequent. Thus, data sets of colonoscopy complications large enough to be statistically meaningful for studies of this type require an extraordinarily large patient pool. For this prospective, observational cohort study, the authors obtained the large sample size by mining administrative claims data for 3 years, not through examining clinical data. As a result, several assumptions were made. These 3 million colonoscopies represented all indications — not just colorectal cancer screening. Billing claims for anesthesia represented surrogate markers for administration of propofol-based anesthesia. While anesthesia assistance was associated with increased risk of perforation, hemorrhage, abdominal pain, anesthesia complications, and stroke; risk of perforation associated with anesthesia was increased only in patients who underwent polypectomy.

Study methodology and confounding variables aside, it is hard to ignore the core message here: a large body of data analyzed rigorously demonstrate that anesthesia support for colonoscopy increases risk of procedure-related complications.

Patients who are ill, have certain cardiopulmonary issues, or do not sedate adequately with moderate sedation benefit from anesthesia assistance for colonoscopy. But for patients undergoing routine colonoscopy, without such issues, who could safely undergo colonoscopy under moderate sedation without unreasonable discomfort, we must now ask ourselves and discuss with our patients honestly, not only whether the added cost of anesthesia is reasonable — but also whether the apparent added risk of anesthesia justifies perceived benefits.

Dr. John A. Martin is senior associate consultant and associate professor, associate chair for endoscopy, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

We are approaching a time when half of all colonoscopies are performed with anesthesia assistance, most using propofol. Undeniably, some patients require anesthesia support for medical reasons, or because they do not sedate adequately with opiate-benzodiazepine combinations endoscopists can administer. The popularity of propofol-based anesthesia for routine colonoscopy, however, is based on several perceived benefits: patient demand for a discomfort-free procedure, rapid sedation followed by quick recovery, and good reimbursement for the anesthesia service itself, added to the benefits of faster overall procedure turnaround time. And presently, there is no disincentive — financial or otherwise — to continuing or expanding this practice. Colonoscopy with anesthesia looks like a win-win for both patient and endoscopist, as long as the added cost of anesthesia can be justified.

However, while anesthesia-assisted colonoscopy appears to possess several advantages, growing evidence suggests that a lower risk of complications is not one of them.

A smaller study (165,000 colonoscopies) using NCI SEER registry data suggested that adding anesthesia to colonoscopy may increase some adverse events. Cooper et al. (JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:551-6) showed an increase in overall complications and, specifically, aspiration, although not in technical complications of colonoscopy, including perforation and splenic rupture. However, this study did not include patients who underwent polypectomy. Wernli, et al. now show evidence derived from over 3 million patients demonstrating that adding anesthesia to colonoscopy increases complications significantly — not only aspiration, but also technical aspects of colonoscopy, including perforation, bleeding, and abdominal pain.

Colonoscopy is extremely safe, so complications are infrequent. Thus, data sets of colonoscopy complications large enough to be statistically meaningful for studies of this type require an extraordinarily large patient pool. For this prospective, observational cohort study, the authors obtained the large sample size by mining administrative claims data for 3 years, not through examining clinical data. As a result, several assumptions were made. These 3 million colonoscopies represented all indications — not just colorectal cancer screening. Billing claims for anesthesia represented surrogate markers for administration of propofol-based anesthesia. While anesthesia assistance was associated with increased risk of perforation, hemorrhage, abdominal pain, anesthesia complications, and stroke; risk of perforation associated with anesthesia was increased only in patients who underwent polypectomy.

Study methodology and confounding variables aside, it is hard to ignore the core message here: a large body of data analyzed rigorously demonstrate that anesthesia support for colonoscopy increases risk of procedure-related complications.

Patients who are ill, have certain cardiopulmonary issues, or do not sedate adequately with moderate sedation benefit from anesthesia assistance for colonoscopy. But for patients undergoing routine colonoscopy, without such issues, who could safely undergo colonoscopy under moderate sedation without unreasonable discomfort, we must now ask ourselves and discuss with our patients honestly, not only whether the added cost of anesthesia is reasonable — but also whether the apparent added risk of anesthesia justifies perceived benefits.

Dr. John A. Martin is senior associate consultant and associate professor, associate chair for endoscopy, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Receiving anesthesia services while undergoing a colonoscopy may not be in your patients’ best interest, as doing so could significantly increase the likelihood of patients experiencing serious complications within 30 days of the procedure.

This is according to a new study published in the April issue of Gastroenterology, in which Dr. Karen J. Wernli and her coinvestigators analyzed claims data, collected from the Truven Health MarketScan Research Database, related to 3,168,228 colonoscopy procedures that took place between 2008 and 2011, to determine whether patients who received anesthesia were at a higher risk of developing complications after the procedure (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.018).

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

“The involvement of anesthesia services for colonoscopy sedation, mainly to administer propofol, has increased accordingly, from 11.0% of colonoscopies in 2001 to 23.4% in 2006, with projections of more than 50% in 2015,” wrote Dr. Wernli of the Group Health Research Institute in Seattle, and her coauthors. “Whether the use of propofol is associated with higher rates of short-term complications compared with standard sedation is not well understood.”

Men and women whose data was included in the study were between 40 and 64 years of age; men accounted for 46.8% of those receiving standard sedation (53.2% women) and 46.5% of those receiving anesthesia services (53.5% women). A total of 4,939,993 individuals were initially screened for enrollment, with 39,784 excluded because of a previous colorectal cancer diagnosis, 240,038 for “noncancer exclusions,” and 1,491,943 for being enrolled in the study less than 1 year.

Standard sedation was done in 2,079,784 (65.6%) of the procedures included in the study, while the other 1,088,444 (34.4%) colonoscopies involved anesthesia services. Use of anesthesia services resulted in a 13% increase in likelihood for patients to experience some kind of complication within 30 days of colonoscopy (95% confidence interval, 1.12-1.14). The most common complications were perforation (odds ratio, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.00-1.15), hemorrhage (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.27-1.30), abdominal pain (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.05-1.08), complications secondary to anesthesia (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.05-1.28), and “stroke and other central nervous system events” (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08).

Analysis of geographic distribution of colonoscopies performed with and without anesthesia services showed that all areas of the United States had a higher likelihood of postcolonoscopy complications associated with anesthesia except in the Southeast, where there was no association between the two. Additionally, in the western U.S., use of anesthesia services was less common than in any other geographic area, but was associated with a staggering 60% higher chance of complication within 30 days for patients who did opt for it.

“Although the use of anesthesia agents can directly impact colonoscopy outcomes, it is not solely the anesthesia agent that could lead to additional complications,” the study authors wrote. “In the absence of patient feedback, increased colonic-wall tension from colonoscopy pressure may not be identified by the endoscopist, and, consistent with our results, could lead to increased risks of colonic complications, such as perforation and abdominal pain.”

Dr. Wernli and her coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Receiving anesthesia services while undergoing a colonoscopy may not be in your patients’ best interest, as doing so could significantly increase the likelihood of patients experiencing serious complications within 30 days of the procedure.

This is according to a new study published in the April issue of Gastroenterology, in which Dr. Karen J. Wernli and her coinvestigators analyzed claims data, collected from the Truven Health MarketScan Research Database, related to 3,168,228 colonoscopy procedures that took place between 2008 and 2011, to determine whether patients who received anesthesia were at a higher risk of developing complications after the procedure (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.018).

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

“The involvement of anesthesia services for colonoscopy sedation, mainly to administer propofol, has increased accordingly, from 11.0% of colonoscopies in 2001 to 23.4% in 2006, with projections of more than 50% in 2015,” wrote Dr. Wernli of the Group Health Research Institute in Seattle, and her coauthors. “Whether the use of propofol is associated with higher rates of short-term complications compared with standard sedation is not well understood.”

Men and women whose data was included in the study were between 40 and 64 years of age; men accounted for 46.8% of those receiving standard sedation (53.2% women) and 46.5% of those receiving anesthesia services (53.5% women). A total of 4,939,993 individuals were initially screened for enrollment, with 39,784 excluded because of a previous colorectal cancer diagnosis, 240,038 for “noncancer exclusions,” and 1,491,943 for being enrolled in the study less than 1 year.

Standard sedation was done in 2,079,784 (65.6%) of the procedures included in the study, while the other 1,088,444 (34.4%) colonoscopies involved anesthesia services. Use of anesthesia services resulted in a 13% increase in likelihood for patients to experience some kind of complication within 30 days of colonoscopy (95% confidence interval, 1.12-1.14). The most common complications were perforation (odds ratio, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.00-1.15), hemorrhage (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.27-1.30), abdominal pain (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.05-1.08), complications secondary to anesthesia (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.05-1.28), and “stroke and other central nervous system events” (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08).

Analysis of geographic distribution of colonoscopies performed with and without anesthesia services showed that all areas of the United States had a higher likelihood of postcolonoscopy complications associated with anesthesia except in the Southeast, where there was no association between the two. Additionally, in the western U.S., use of anesthesia services was less common than in any other geographic area, but was associated with a staggering 60% higher chance of complication within 30 days for patients who did opt for it.

“Although the use of anesthesia agents can directly impact colonoscopy outcomes, it is not solely the anesthesia agent that could lead to additional complications,” the study authors wrote. “In the absence of patient feedback, increased colonic-wall tension from colonoscopy pressure may not be identified by the endoscopist, and, consistent with our results, could lead to increased risks of colonic complications, such as perforation and abdominal pain.”

Dr. Wernli and her coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Using anesthesia services on individuals receiving colonoscopy increases the overall risk of complications associated with the procedure.

Major finding: Colonoscopy patients who received anesthesia had a 13% higher risk of complication within 30 days, including perforation, hemorrhage, abdominal pain, and stroke.

Data source: A prospective cohort study of claims data from 3,168,228 colonoscopy procedures in the Truven Health MarketScan Research Databases from 2008 to 2011.

Disclosures: Funding provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Wernli and her coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Late-week discharges to home after CRC surgery prone to readmission

BOSTON – The day of the week a patient is discharged from the hospital may have an impact the likelihood of readmission.

Patients discharged home from the hospital on a Thursday after colorectal cancer surgery are more likely to be readmitted within 30 days than those discharged on any other day of the week, investigators found.

In contrast, there were no significant day-dependent differences in readmission rates among patients discharged to a skilled nursing facility or acute rehabilitation program, although patients admitted to clinical facilities had higher overall readmission rates, reported Anna Gustin and coinvestigators at the Levine Cancer Institute at the Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, N.C.

“For a patient discharged on a Thursday, if you’re going to get an infection, it’s going to be probably during the weekend, when it’s difficult to contact your primary physician, and when other resources are not as readily available,” said Ms. Gustin, who conducts epidemiologic research at Levine Cancer Center and is also a pre-med student and Japanese major at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C.

In a study presented in a poster session at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium, Ms. Gustin and her coauthors looked at factors influencing readmission rates among patients undergoing surgery for primary, nonmetastatic colorectal cancer resections.

They drew on the to evaluate outcomes for 93,04 SEER-(Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) Medicare database seven patients aged 66 years and older treated for primary colorectal cancer from 1998 through 2009.

They looked at potential contributing factors such as patient demographics, socioeconomic status, length of stay, days of admission and discharge, and discharge setting (home or clinical facility).

They use multivariate logistic regression models to analyze readmission rates at 14 and 30 days after initial discharge.

Focusing on home discharges, they found that as the week progressed, there was a significant likelihood that a patient discharged home would be readmitted (P less then .001 by chi-square and Cochran-Armitage tests). As noted before, the highest rate of readmission was for patients discharged on Thursday, at 12.4%, compared with 10.1% for patients discharged on Sunday, the discharge day least likely to be associated with rehospitalization.

In multivariate analysis, factors significantly associated with risk for 30-day readmission included male vs. female (hazard ratio, 1.16), black vs. other race (HR, 1.22), length of stay 5, 6-7, or 8-10 vs. 12 or more days (HR, 0.48, 0.59, 0.77, respectively), Charlson comorbidity index score 0, 1 or 3 vs. 3 (HR, 0.59, 0.73, 0.82, respectively), and home discharge vs. other (HR, 0.66; all above comparisons significant as shown by 95% confidence intervals).

The authors concluded that although home discharge itself reduces the likelihood of readmission, “improvements in preparing patients for discharge to home are needed. Additional outpatient interventions could rescue patients from readmission.”

They also suggested reexamining staffing policies and weekend availability of resources for patients, and call for addressing disparities in readmissions based on race, sex, length of stay, and comorbidities.

The study was internally supported. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

BOSTON – The day of the week a patient is discharged from the hospital may have an impact the likelihood of readmission.

Patients discharged home from the hospital on a Thursday after colorectal cancer surgery are more likely to be readmitted within 30 days than those discharged on any other day of the week, investigators found.

In contrast, there were no significant day-dependent differences in readmission rates among patients discharged to a skilled nursing facility or acute rehabilitation program, although patients admitted to clinical facilities had higher overall readmission rates, reported Anna Gustin and coinvestigators at the Levine Cancer Institute at the Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, N.C.

“For a patient discharged on a Thursday, if you’re going to get an infection, it’s going to be probably during the weekend, when it’s difficult to contact your primary physician, and when other resources are not as readily available,” said Ms. Gustin, who conducts epidemiologic research at Levine Cancer Center and is also a pre-med student and Japanese major at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C.

In a study presented in a poster session at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium, Ms. Gustin and her coauthors looked at factors influencing readmission rates among patients undergoing surgery for primary, nonmetastatic colorectal cancer resections.

They drew on the to evaluate outcomes for 93,04 SEER-(Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) Medicare database seven patients aged 66 years and older treated for primary colorectal cancer from 1998 through 2009.

They looked at potential contributing factors such as patient demographics, socioeconomic status, length of stay, days of admission and discharge, and discharge setting (home or clinical facility).

They use multivariate logistic regression models to analyze readmission rates at 14 and 30 days after initial discharge.

Focusing on home discharges, they found that as the week progressed, there was a significant likelihood that a patient discharged home would be readmitted (P less then .001 by chi-square and Cochran-Armitage tests). As noted before, the highest rate of readmission was for patients discharged on Thursday, at 12.4%, compared with 10.1% for patients discharged on Sunday, the discharge day least likely to be associated with rehospitalization.

In multivariate analysis, factors significantly associated with risk for 30-day readmission included male vs. female (hazard ratio, 1.16), black vs. other race (HR, 1.22), length of stay 5, 6-7, or 8-10 vs. 12 or more days (HR, 0.48, 0.59, 0.77, respectively), Charlson comorbidity index score 0, 1 or 3 vs. 3 (HR, 0.59, 0.73, 0.82, respectively), and home discharge vs. other (HR, 0.66; all above comparisons significant as shown by 95% confidence intervals).

The authors concluded that although home discharge itself reduces the likelihood of readmission, “improvements in preparing patients for discharge to home are needed. Additional outpatient interventions could rescue patients from readmission.”

They also suggested reexamining staffing policies and weekend availability of resources for patients, and call for addressing disparities in readmissions based on race, sex, length of stay, and comorbidities.

The study was internally supported. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

BOSTON – The day of the week a patient is discharged from the hospital may have an impact the likelihood of readmission.

Patients discharged home from the hospital on a Thursday after colorectal cancer surgery are more likely to be readmitted within 30 days than those discharged on any other day of the week, investigators found.

In contrast, there were no significant day-dependent differences in readmission rates among patients discharged to a skilled nursing facility or acute rehabilitation program, although patients admitted to clinical facilities had higher overall readmission rates, reported Anna Gustin and coinvestigators at the Levine Cancer Institute at the Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, N.C.

“For a patient discharged on a Thursday, if you’re going to get an infection, it’s going to be probably during the weekend, when it’s difficult to contact your primary physician, and when other resources are not as readily available,” said Ms. Gustin, who conducts epidemiologic research at Levine Cancer Center and is also a pre-med student and Japanese major at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C.

In a study presented in a poster session at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium, Ms. Gustin and her coauthors looked at factors influencing readmission rates among patients undergoing surgery for primary, nonmetastatic colorectal cancer resections.

They drew on the to evaluate outcomes for 93,04 SEER-(Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) Medicare database seven patients aged 66 years and older treated for primary colorectal cancer from 1998 through 2009.

They looked at potential contributing factors such as patient demographics, socioeconomic status, length of stay, days of admission and discharge, and discharge setting (home or clinical facility).

They use multivariate logistic regression models to analyze readmission rates at 14 and 30 days after initial discharge.

Focusing on home discharges, they found that as the week progressed, there was a significant likelihood that a patient discharged home would be readmitted (P less then .001 by chi-square and Cochran-Armitage tests). As noted before, the highest rate of readmission was for patients discharged on Thursday, at 12.4%, compared with 10.1% for patients discharged on Sunday, the discharge day least likely to be associated with rehospitalization.

In multivariate analysis, factors significantly associated with risk for 30-day readmission included male vs. female (hazard ratio, 1.16), black vs. other race (HR, 1.22), length of stay 5, 6-7, or 8-10 vs. 12 or more days (HR, 0.48, 0.59, 0.77, respectively), Charlson comorbidity index score 0, 1 or 3 vs. 3 (HR, 0.59, 0.73, 0.82, respectively), and home discharge vs. other (HR, 0.66; all above comparisons significant as shown by 95% confidence intervals).

The authors concluded that although home discharge itself reduces the likelihood of readmission, “improvements in preparing patients for discharge to home are needed. Additional outpatient interventions could rescue patients from readmission.”

They also suggested reexamining staffing policies and weekend availability of resources for patients, and call for addressing disparities in readmissions based on race, sex, length of stay, and comorbidities.

The study was internally supported. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

Key clinical point: Patients discharged home on a Thursday following surgery for primary colorectal cancer are more likely to be readmitted with 30 days than are patients discharged home on any other day of the week.

Major finding: The highest rate of readmission was for patients discharged on Thursday, at 12.4%, compared with lowest rate of 10.1% for patients discharged on Sunday.

Data source: Retrospective SEER-Medicare database review of records on 93,047 patients treated for colorectal cancer.

Disclosures: The study was internally supported. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

Elective CRC resections increase with universal insurance

BOSTON – Expanding access to health insurance for low- and moderate-income families has apparently improved colorectal cancer care in Massachusetts, and may do the same for other states that participate in Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.

That assertion comes from investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. They found that following the introduction in 2006 of a universal health insurance law in the Bay State – the law that would serve as a model for the Affordable Care Act – the rate of elective colorectal resections increased while the rate of emergent resections decreased.

In contrast, in three states used as controls, the opposite occurred.

“This could be due to a variety of different factors, including earlier diagnosis, presenting with disease more amenable to surgical resection. It could also be due to increased referrals from primary care providers or GI doctors,” said Dr. Andrew P. Loehrer from the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Surgery, at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

He acknowledged, however, that the administrative dataset he and his colleagues used in the study lacks information about clinical staging or use of neoadjuvant therapy, making it difficult to determine whether insured patients actually present at an earlier, more readily treatable disease stage.

Nonetheless, “from a cancer standpoint, my study provides early, hopeful evidence. In order to definitively say that this improves care, we need to have some more of the cancer-specific variables, but with this study, combined with some other work that we and other groups have done, we see that patients in Massachusetts are presenting with earlier stage disease, whether it’s acute disease or cancer, and they’re getting more appropriate care in a more timely fashion,” he said in an interview.

Role model

Dr. Loehrer noted that disparities in access to health care have been shown in previous studies to be associated with the likelihood of unfavorable outcomes for patients with colorectal cancer. For example, a 2008 study (Lancet Oncol. 2008 Mar;9:222-31) showed that uninsured patients with colorectal cancer had a twofold greater risk for presenting with advanced disease than privately insured patients. Additionally, a 2004 study (Br J Surg. 91:605-9) showed that patients who presented with colorectal cancer requiring emergent resection had significantly lower 5-year overall survival than patients who underwent elective resection.

Massachusetts implemented its pioneering health insurance reform law in 2006. The law increased eligibility for persons with incomes up to 150% of the Federal Poverty Level, created government-subsidized insurance for those with incomes from 150% to 300% of the poverty line, mandated that all Bay State residents have some form of health insurance, and allowed young adults up to the age of 26 to remain on their parents’ plans.

To see whether insurance reform could have a salutary effect on cancer care, the investigators drew on Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) State Inpatient Databases for Massachusetts and for Florida, New Jersey, and New York as control states. They used ICD-9 diagnosis codes to identify patients with colorectal cancer, including those who underwent resection.

To establish procedure rates, they used U.S. Census Bureau data to establish the population of denominators, which included all adults 18-54 years of age who were insured either through Medicaid, Commonwealth Care (in Massachusetts), or were listed as uninsured or self-pay. Medicare-insured patients were not included, as they were not directly affected by the reform law.

They identified 18,598 patients admitted to Massachusetts hospitals for colorectal cancer from 2001 through 2011, and 147,482 admitted during the same period to hospitals in the control states.

The authors created Poisson difference-in-differences models which compare changes in the selected outcomes in Massachusetts with changes in the control states. The models were adjusted for age, sex, race, hospital type, and secular trends.

They found that admission rates for colorectal cancer increased over time in Massachusetts by 13.3 per 100,000 residents per quarter, compared with 8.3/100,000 in the control states, translating into an adjusted rate ratio (ARR) of 1.13. Resection rates for cancer, the primary study outcome, also grew by a significantly larger margin in Massachusetts, by 5.5/100,000, compared with 0.5/100,000 in control states, with an ARR of 1.37 (P less than .001 for both comparisons).

For the secondary outcome of changes in emergent and elective resections after admission, they found that emergent surgeries in Massachusetts declined by 2.7/100,000, but increased by 4.4/100,000 in the states without insurance reform. Similarly, elective resections after admission increased in the Bay State by 7.4/100,000, but decreased by 1.8/100,000 in control states.

Relative to controls, the adjusted probability that a patient with colorectal cancer in Massachusetts would have emergent surgery after admission declined by 6.1% (P = .014) and the probability that he or she would have elective resection increased by 7.8% (P = .005).

An analysis of the odds ratio of resection during admission, adjusted for age, race, presentation with metastatic disease, hospital type, and secular trends, showed that prior to reform uninsured patients in both Massachusetts and control states were significantly less likely than privately insured patients to have resections (odds ratio, 0.42 in Mass.; 0.45 in control states).

However, after the implementation of reform the gap between previously uninsured and privately insured in Massachusetts narrowed (OR, 0.63) but remained the same in control states (OR, 0.44).

Dr. Loehrer acknowledged in an interview that Massachusetts differs from other states in some regards, including in concentrations of health providers and in requirements for insurance coverage that were in place even before the 2006 reforms, but is optimistic that improvements in colorectal cancer care can occur in states that have embraced the Affordable Care Act.

“There are a lot of services that were available and we had high colonoscopy rates prior to all of this, but that said, the mechanism is exactly the same, there are still vulnerable populations, and at this point I think it’s hopeful and promising that we will see similar results in other states,” he said.

BOSTON – Expanding access to health insurance for low- and moderate-income families has apparently improved colorectal cancer care in Massachusetts, and may do the same for other states that participate in Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.

That assertion comes from investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. They found that following the introduction in 2006 of a universal health insurance law in the Bay State – the law that would serve as a model for the Affordable Care Act – the rate of elective colorectal resections increased while the rate of emergent resections decreased.

In contrast, in three states used as controls, the opposite occurred.

“This could be due to a variety of different factors, including earlier diagnosis, presenting with disease more amenable to surgical resection. It could also be due to increased referrals from primary care providers or GI doctors,” said Dr. Andrew P. Loehrer from the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Surgery, at the annual Society of Surgical Oncology Cancer Symposium.

He acknowledged, however, that the administrative dataset he and his colleagues used in the study lacks information about clinical staging or use of neoadjuvant therapy, making it difficult to determine whether insured patients actually present at an earlier, more readily treatable disease stage.

Nonetheless, “from a cancer standpoint, my study provides early, hopeful evidence. In order to definitively say that this improves care, we need to have some more of the cancer-specific variables, but with this study, combined with some other work that we and other groups have done, we see that patients in Massachusetts are presenting with earlier stage disease, whether it’s acute disease or cancer, and they’re getting more appropriate care in a more timely fashion,” he said in an interview.

Role model

Dr. Loehrer noted that disparities in access to health care have been shown in previous studies to be associated with the likelihood of unfavorable outcomes for patients with colorectal cancer. For example, a 2008 study (Lancet Oncol. 2008 Mar;9:222-31) showed that uninsured patients with colorectal cancer had a twofold greater risk for presenting with advanced disease than privately insured patients. Additionally, a 2004 study (Br J Surg. 91:605-9) showed that patients who presented with colorectal cancer requiring emergent resection had significantly lower 5-year overall survival than patients who underwent elective resection.

Massachusetts implemented its pioneering health insurance reform law in 2006. The law increased eligibility for persons with incomes up to 150% of the Federal Poverty Level, created government-subsidized insurance for those with incomes from 150% to 300% of the poverty line, mandated that all Bay State residents have some form of health insurance, and allowed young adults up to the age of 26 to remain on their parents’ plans.

To see whether insurance reform could have a salutary effect on cancer care, the investigators drew on Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) State Inpatient Databases for Massachusetts and for Florida, New Jersey, and New York as control states. They used ICD-9 diagnosis codes to identify patients with colorectal cancer, including those who underwent resection.

To establish procedure rates, they used U.S. Census Bureau data to establish the population of denominators, which included all adults 18-54 years of age who were insured either through Medicaid, Commonwealth Care (in Massachusetts), or were listed as uninsured or self-pay. Medicare-insured patients were not included, as they were not directly affected by the reform law.

They identified 18,598 patients admitted to Massachusetts hospitals for colorectal cancer from 2001 through 2011, and 147,482 admitted during the same period to hospitals in the control states.

The authors created Poisson difference-in-differences models which compare changes in the selected outcomes in Massachusetts with changes in the control states. The models were adjusted for age, sex, race, hospital type, and secular trends.

They found that admission rates for colorectal cancer increased over time in Massachusetts by 13.3 per 100,000 residents per quarter, compared with 8.3/100,000 in the control states, translating into an adjusted rate ratio (ARR) of 1.13. Resection rates for cancer, the primary study outcome, also grew by a significantly larger margin in Massachusetts, by 5.5/100,000, compared with 0.5/100,000 in control states, with an ARR of 1.37 (P less than .001 for both comparisons).

For the secondary outcome of changes in emergent and elective resections after admission, they found that emergent surgeries in Massachusetts declined by 2.7/100,000, but increased by 4.4/100,000 in the states without insurance reform. Similarly, elective resections after admission increased in the Bay State by 7.4/100,000, but decreased by 1.8/100,000 in control states.

Relative to controls, the adjusted probability that a patient with colorectal cancer in Massachusetts would have emergent surgery after admission declined by 6.1% (P = .014) and the probability that he or she would have elective resection increased by 7.8% (P = .005).

An analysis of the odds ratio of resection during admission, adjusted for age, race, presentation with metastatic disease, hospital type, and secular trends, showed that prior to reform uninsured patients in both Massachusetts and control states were significantly less likely than privately insured patients to have resections (odds ratio, 0.42 in Mass.; 0.45 in control states).

However, after the implementation of reform the gap between previously uninsured and privately insured in Massachusetts narrowed (OR, 0.63) but remained the same in control states (OR, 0.44).

Dr. Loehrer acknowledged in an interview that Massachusetts differs from other states in some regards, including in concentrations of health providers and in requirements for insurance coverage that were in place even before the 2006 reforms, but is optimistic that improvements in colorectal cancer care can occur in states that have embraced the Affordable Care Act.

“There are a lot of services that were available and we had high colonoscopy rates prior to all of this, but that said, the mechanism is exactly the same, there are still vulnerable populations, and at this point I think it’s hopeful and promising that we will see similar results in other states,” he said.

BOSTON – Expanding access to health insurance for low- and moderate-income families has apparently improved colorectal cancer care in Massachusetts, and may do the same for other states that participate in Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.

That assertion comes from investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. They found that following the introduction in 2006 of a universal health insurance law in the Bay State – the law that would serve as a model for the Affordable Care Act – the rate of elective colorectal resections increased while the rate of emergent resections decreased.

In contrast, in three states used as controls, the opposite occurred.