User login

Gaps persist in awareness, treatment of high LDL cholesterol

TOPLINE:

The prevalence of elevated LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) has declined over the past 2 decades, but 1 in 17 Americans still have a level of 160-189 mg/dL, and 1 in 48 have a level of at least 190 mg/dL, new research shows. Among people with the higher LDL-C level, one in four are both unaware and untreated, the authors report.

METHODOLOGY:

- Using data on 23,667 adult participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey conducted from 1999 to 2020, researchers identified 1,851 (7.8%) with an LDL-C level of 160-189 mg/dL and 669 (2.8%) with an LDL-C level of at least 190 mg/dL.

- Individuals were classified as “unaware” if they had never had their LDL-C measured or had never been informed of having elevated LDL-C and as “untreated” if their medications didn’t include a statin, ezetimibe, a bile acid sequestrant, or a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor.

- The authors compared the prevalence of “unaware” and “untreated” by age, sex, race and ethnicity, educational attainment, poverty index, and insurance status.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the study period, the age-adjusted prevalence of an LDL-C level of 160-189 mg/dL declined from 12.4% (95% confidence interval, 10.0%-15.3%), representing 21.5 million U.S. adults, to 6.1% (95% CI, 4.8%-7.6%), representing 14.0 million adults (P < .001).

- The age-adjusted prevalence of an LDL-C level of at least 190 mg/dL declined from 3.8% (95% CI, 2.8%-5.2%), representing 6.6 million adults, to 2.1% (95% CI, 1.4%-3.0%), representing 4.8 million adults (P = .001).

- Among those with an LDL-C level of 160-189 mg/dL, the proportion of who were unaware and untreated declined from 52.1% to 42.7%, and among those with an LDL-C level of at least 190 mg/dL, it declined from 40.8% to 26.8%.

- Being unaware and untreated was more common in younger adults, men, racial and ethnic minority groups, those with lower educational attainment, those with lower income, and those without health insurance.

IN PRACTICE:

The lack of awareness and treatment of high LDL-C uncovered by the study “may be due to difficulties accessing primary care, low rates of screening in primary care, lack of consensus on screening recommendations, insufficient emphasis on LDL-C as a quality measure, and hesitance to treat asymptomatic individuals,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The research was led by Ahmed Sayed, MBBS, faculty of medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. It was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis was limited by a small number of participants with LDL-C levels of at least 190 mg/dL, possible nonresponse bias, and dependency on participant recall of whether LDL-C was previously measured. The inclusion of pregnant women may have influenced LDL-C levels.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Sayed has no relevant conflict of interest. The disclosures of the other authors are listed in the original publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The prevalence of elevated LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) has declined over the past 2 decades, but 1 in 17 Americans still have a level of 160-189 mg/dL, and 1 in 48 have a level of at least 190 mg/dL, new research shows. Among people with the higher LDL-C level, one in four are both unaware and untreated, the authors report.

METHODOLOGY:

- Using data on 23,667 adult participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey conducted from 1999 to 2020, researchers identified 1,851 (7.8%) with an LDL-C level of 160-189 mg/dL and 669 (2.8%) with an LDL-C level of at least 190 mg/dL.

- Individuals were classified as “unaware” if they had never had their LDL-C measured or had never been informed of having elevated LDL-C and as “untreated” if their medications didn’t include a statin, ezetimibe, a bile acid sequestrant, or a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor.

- The authors compared the prevalence of “unaware” and “untreated” by age, sex, race and ethnicity, educational attainment, poverty index, and insurance status.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the study period, the age-adjusted prevalence of an LDL-C level of 160-189 mg/dL declined from 12.4% (95% confidence interval, 10.0%-15.3%), representing 21.5 million U.S. adults, to 6.1% (95% CI, 4.8%-7.6%), representing 14.0 million adults (P < .001).

- The age-adjusted prevalence of an LDL-C level of at least 190 mg/dL declined from 3.8% (95% CI, 2.8%-5.2%), representing 6.6 million adults, to 2.1% (95% CI, 1.4%-3.0%), representing 4.8 million adults (P = .001).

- Among those with an LDL-C level of 160-189 mg/dL, the proportion of who were unaware and untreated declined from 52.1% to 42.7%, and among those with an LDL-C level of at least 190 mg/dL, it declined from 40.8% to 26.8%.

- Being unaware and untreated was more common in younger adults, men, racial and ethnic minority groups, those with lower educational attainment, those with lower income, and those without health insurance.

IN PRACTICE:

The lack of awareness and treatment of high LDL-C uncovered by the study “may be due to difficulties accessing primary care, low rates of screening in primary care, lack of consensus on screening recommendations, insufficient emphasis on LDL-C as a quality measure, and hesitance to treat asymptomatic individuals,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The research was led by Ahmed Sayed, MBBS, faculty of medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. It was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis was limited by a small number of participants with LDL-C levels of at least 190 mg/dL, possible nonresponse bias, and dependency on participant recall of whether LDL-C was previously measured. The inclusion of pregnant women may have influenced LDL-C levels.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Sayed has no relevant conflict of interest. The disclosures of the other authors are listed in the original publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The prevalence of elevated LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) has declined over the past 2 decades, but 1 in 17 Americans still have a level of 160-189 mg/dL, and 1 in 48 have a level of at least 190 mg/dL, new research shows. Among people with the higher LDL-C level, one in four are both unaware and untreated, the authors report.

METHODOLOGY:

- Using data on 23,667 adult participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey conducted from 1999 to 2020, researchers identified 1,851 (7.8%) with an LDL-C level of 160-189 mg/dL and 669 (2.8%) with an LDL-C level of at least 190 mg/dL.

- Individuals were classified as “unaware” if they had never had their LDL-C measured or had never been informed of having elevated LDL-C and as “untreated” if their medications didn’t include a statin, ezetimibe, a bile acid sequestrant, or a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor.

- The authors compared the prevalence of “unaware” and “untreated” by age, sex, race and ethnicity, educational attainment, poverty index, and insurance status.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the study period, the age-adjusted prevalence of an LDL-C level of 160-189 mg/dL declined from 12.4% (95% confidence interval, 10.0%-15.3%), representing 21.5 million U.S. adults, to 6.1% (95% CI, 4.8%-7.6%), representing 14.0 million adults (P < .001).

- The age-adjusted prevalence of an LDL-C level of at least 190 mg/dL declined from 3.8% (95% CI, 2.8%-5.2%), representing 6.6 million adults, to 2.1% (95% CI, 1.4%-3.0%), representing 4.8 million adults (P = .001).

- Among those with an LDL-C level of 160-189 mg/dL, the proportion of who were unaware and untreated declined from 52.1% to 42.7%, and among those with an LDL-C level of at least 190 mg/dL, it declined from 40.8% to 26.8%.

- Being unaware and untreated was more common in younger adults, men, racial and ethnic minority groups, those with lower educational attainment, those with lower income, and those without health insurance.

IN PRACTICE:

The lack of awareness and treatment of high LDL-C uncovered by the study “may be due to difficulties accessing primary care, low rates of screening in primary care, lack of consensus on screening recommendations, insufficient emphasis on LDL-C as a quality measure, and hesitance to treat asymptomatic individuals,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

The research was led by Ahmed Sayed, MBBS, faculty of medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. It was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis was limited by a small number of participants with LDL-C levels of at least 190 mg/dL, possible nonresponse bias, and dependency on participant recall of whether LDL-C was previously measured. The inclusion of pregnant women may have influenced LDL-C levels.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Sayed has no relevant conflict of interest. The disclosures of the other authors are listed in the original publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AF tied to 45% increase in mild cognitive impairment

TOPLINE:

results of a new study suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- From over 4.3 million people in the UK primary electronic health record (EHR) database, researchers identified 233,833 (5.4%) with AF (mean age, 74.2 years) and randomly selected one age- and sex-matched control person without AF for each AF case patient.

- The primary outcome was incidence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

- The authors adjusted for age, sex, year at study entry, socioeconomic status, smoking, and a number of comorbid conditions.

- During a median of 5.3 years of follow-up, there were 4,269 incident MCI cases among both AF and non-AF patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with AF had a higher risk of MCI than that of those without AF (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35-1.56).

- Besides AF, older age (risk ratio [RR], 1.08) and history of depression (RR, 1.44) were associated with greater risk of MCI, as were female sex, greater socioeconomic deprivation, stroke, and multimorbidity, including, for example, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and peripheral artery disease (all P < .001).

- Individuals with AF who received oral anticoagulants or amiodarone were not at increased risk of MCI, as was the case for those treated with digoxin.

- Individuals with AF and MCI were at greater risk of dementia (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.09-1.42). Sex, smoking, chronic kidney disease, and multi-comorbidity were among factors linked to elevated dementia risk.

IN PRACTICE:

The findings emphasize the association of multi-comorbidity and cardiovascular risk factors with development of MCI and progression to dementia in AF patients, the authors wrote. They noted that the data suggest combining anticoagulation and symptom and comorbidity management may prevent cognitive deterioration.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Sheng-Chia Chung, PhD, Institute of Health informatics Research, University College London, and colleagues. It was published online Oct. 25, 2023, as a research letter in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC): Advances.

LIMITATIONS:

The EHR dataset may have lacked granularity and detail, and some risk factors or comorbidities may not have been measured. While those with AF receiving digoxin or amiodarone treatment had no higher risk of MCI than their non-AF peers, the study’s observational design and very wide confidence intervals for these subgroups prevent making solid inferences about causality or a potential protective role of these drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Chung is supported by the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) Author Rui Providencia, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Health informatics Research, University College London, is supported by the University College London British Heart Foundation and NIHR. All other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

results of a new study suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- From over 4.3 million people in the UK primary electronic health record (EHR) database, researchers identified 233,833 (5.4%) with AF (mean age, 74.2 years) and randomly selected one age- and sex-matched control person without AF for each AF case patient.

- The primary outcome was incidence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

- The authors adjusted for age, sex, year at study entry, socioeconomic status, smoking, and a number of comorbid conditions.

- During a median of 5.3 years of follow-up, there were 4,269 incident MCI cases among both AF and non-AF patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with AF had a higher risk of MCI than that of those without AF (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35-1.56).

- Besides AF, older age (risk ratio [RR], 1.08) and history of depression (RR, 1.44) were associated with greater risk of MCI, as were female sex, greater socioeconomic deprivation, stroke, and multimorbidity, including, for example, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and peripheral artery disease (all P < .001).

- Individuals with AF who received oral anticoagulants or amiodarone were not at increased risk of MCI, as was the case for those treated with digoxin.

- Individuals with AF and MCI were at greater risk of dementia (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.09-1.42). Sex, smoking, chronic kidney disease, and multi-comorbidity were among factors linked to elevated dementia risk.

IN PRACTICE:

The findings emphasize the association of multi-comorbidity and cardiovascular risk factors with development of MCI and progression to dementia in AF patients, the authors wrote. They noted that the data suggest combining anticoagulation and symptom and comorbidity management may prevent cognitive deterioration.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Sheng-Chia Chung, PhD, Institute of Health informatics Research, University College London, and colleagues. It was published online Oct. 25, 2023, as a research letter in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC): Advances.

LIMITATIONS:

The EHR dataset may have lacked granularity and detail, and some risk factors or comorbidities may not have been measured. While those with AF receiving digoxin or amiodarone treatment had no higher risk of MCI than their non-AF peers, the study’s observational design and very wide confidence intervals for these subgroups prevent making solid inferences about causality or a potential protective role of these drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Chung is supported by the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) Author Rui Providencia, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Health informatics Research, University College London, is supported by the University College London British Heart Foundation and NIHR. All other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

results of a new study suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- From over 4.3 million people in the UK primary electronic health record (EHR) database, researchers identified 233,833 (5.4%) with AF (mean age, 74.2 years) and randomly selected one age- and sex-matched control person without AF for each AF case patient.

- The primary outcome was incidence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

- The authors adjusted for age, sex, year at study entry, socioeconomic status, smoking, and a number of comorbid conditions.

- During a median of 5.3 years of follow-up, there were 4,269 incident MCI cases among both AF and non-AF patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with AF had a higher risk of MCI than that of those without AF (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35-1.56).

- Besides AF, older age (risk ratio [RR], 1.08) and history of depression (RR, 1.44) were associated with greater risk of MCI, as were female sex, greater socioeconomic deprivation, stroke, and multimorbidity, including, for example, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and peripheral artery disease (all P < .001).

- Individuals with AF who received oral anticoagulants or amiodarone were not at increased risk of MCI, as was the case for those treated with digoxin.

- Individuals with AF and MCI were at greater risk of dementia (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.09-1.42). Sex, smoking, chronic kidney disease, and multi-comorbidity were among factors linked to elevated dementia risk.

IN PRACTICE:

The findings emphasize the association of multi-comorbidity and cardiovascular risk factors with development of MCI and progression to dementia in AF patients, the authors wrote. They noted that the data suggest combining anticoagulation and symptom and comorbidity management may prevent cognitive deterioration.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Sheng-Chia Chung, PhD, Institute of Health informatics Research, University College London, and colleagues. It was published online Oct. 25, 2023, as a research letter in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC): Advances.

LIMITATIONS:

The EHR dataset may have lacked granularity and detail, and some risk factors or comorbidities may not have been measured. While those with AF receiving digoxin or amiodarone treatment had no higher risk of MCI than their non-AF peers, the study’s observational design and very wide confidence intervals for these subgroups prevent making solid inferences about causality or a potential protective role of these drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Chung is supported by the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) Author Rui Providencia, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Health informatics Research, University College London, is supported by the University College London British Heart Foundation and NIHR. All other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Nightmare on CIL Street: A Simulation Series to Increase Confidence and Skill in Responding to Clinical Emergencies

The Central Texas Veteran’s Health Care System (CTVHCS) in Temple, Texas, is a 189-bed teaching hospital. CTVHCS opened the Center for Innovation and Learning (CIL) in 2022. The CIL has about 279 m2 of simulation space that includes high- and low-fidelity simulation equipment and multiple laboratories, which can be used to simulate inpatient and outpatient settings. The CIL high-fidelity manikins and environment allow learners to be immersed in the simulation for maximum realism. Computer and video systems provide clear viewing of training, which allows for more in-depth debriefing and learning. CIL simulation training is used by CTVHCS staff, medical residents, and medical and physician assistant students.

The utility of technology in medical education is rapidly evolving. As noted in many studies, simulation creates an environment that can imitate real patients in the format of a lifelike manikin, anatomic regions stations, clinical tasks, and many real-life circumstances.1 Task trainers for procedure simulation have been widely used and studied. A 2020 study noted that simulation training is effective for developing procedural skills in surgery and prevents the decay of surgical skills.2

In reviewing health care education curriculums, we noted that most of the rapid response situations are learned through active patient experiences. Rapid responses are managed by the intensive care unit and primary care teams during the day but at night are run primarily by the postgraduate year 2 (PGY2) night resident and intern. Knowing these logistics and current studies, we decided to build a rapid response simulation curriculum to improve preparedness for PGY1 residents, medical students, and physician assistant students.

Curriculum Planning

Planning the simulation curriculum began with the CTVHCS internal medicine chief resident and registered nurse (RN) educator. CTVHCS data were reviewed to identify the 3 most common rapid response calls from the past 3 years; research on the most common systems affected by rapid responses also was evaluated.

A 2019 study by Lyons and colleagues evaluated 402,023 rapid response activations across 360 hospitals and found that respiratory scenarios made up 38% and cardiac scenarios made up 37%.3 In addition, the CTVHCS has limited support in stroke neurology. Therefore, the internal medicine chief resident and RN educator decided to run 3 evolving rapid response scenarios per session that included cardiac, respiratory, and neurological scenarios. Capabilities and limitations of different high-fidelity manikins were discussed to identify and use the most appropriate simulator for each situation. Objectives that met both general medicine and site-specific education were discussed, and the program was formulated.

Program Description

Nightmare on CIL Street is a simulation-based program designed for new internal medicine residents and students to encounter difficult situations (late at night, on call, or when resources are limited; ie, weekends/holidays) in a controlled simulation environment. During the simulation, learners will be unable to transfer the patient and no additional help is available. Each learner must determine a differential diagnosis and make appropriate medical interventions with only the assistance of a nurse. Scenarios are derived from common rapid response team calls and low-volume/high-impact situations where clinical decisions must be made quickly to ensure the best patient outcomes. High-fidelity manikins that have abilities to respond to questions, simulate breathing, reproduce pathological heart and breath sounds and more are used to create a realistic patient environment.

This program aligns with 2 national Veterans Health Administration priorities: (1) connect veterans to the soonest and best care; and (2) accelerate the Veterans Health Administration journey to be a high-reliability organization (sensitivity to operations, preoccupation with failure, commitment to resilience, and deference to expertise). Nightmare on CIL Street has 3 clinical episodes: 2 cardiac (A Tell-Tale Heart), respiratory (Don’t Breathe), and neurologic (Brain Scan). Additional clinical episodes will be added based on learner feedback and assessed need.

Each simulation event encompassed all 3 episodes that an individual or a team of 2 learners rotate through in a round-robin fashion. The overarching theme for each episode was a rapid response team call with minimal resources that the learner would have to provide care and stabilization. A literature search for rapid response team training programs found few results, but the literature assisted with providing a foundation for Nightmare on CIL Street.4,5 The goal was to completely envelop the learners in a nightmare scenario that required a solution.

After the safety brief and predata collection, learners received a phone call with minimal information about a patient in need of care. The learners responded to the requested area and provided treatment to the emergency over 25 minutes with the bedside nurse (who is an embedded participant). At the conclusion of the scenario, a physician subject matter expert who has been observing, provided a personalized 10-minute debriefing to the learner, which presented specific learning points and opportunities for the learner’s educational development. After the debriefing, learners returned to a conference room and awaited the next call. After all learners completed the 3 episodes, a group debriefing was conducted using the gather, analyze, summarize debriefing framework. The debriefing begins with an open-ended forum for learners to express their thoughts. Then, each scenario is discussed and broken down by key learning objectives. Starting with cardiac and ending with neurology, the logistics of the cases are discussed based on the trajectory of the learners during the scenarios. Each objective is discussed, and learners are allowed to ask questions before moving to the next scenario. After the debriefing, postevent data were gathered.

Objectives

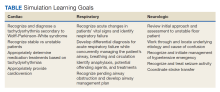

The program objective was to educate residents and students on common rapid response scenarios. We devised each scenario as an evolving simulation where various interventions would improve or worsen vital signs and symptoms. Each scenario had an end goal: cardioversion (cardiac), intubation (respiratory), and transfer (neurologic). Objectives were tailored to the trainees present during the specific simulation (Table).

IMPLEMENTATION

The initial run of the simulation curriculum was implemented on February 22, 2023, and ended on May 17, 2023, with 5 events. Participants included internal medicine PGY1 residents, third-year medical students, and fourth-year physician assistant students. Internal medicine residents ran each scenario with a subject matter expert monitoring; the undergraduate medical trainees partnered with another student. Students were pulled from their ward rotations to attend the simulation, and residents were pulled from electives and wards. Each trainee was able to experience each planned scenario. They were then briefed, participated in each scenario, and ended with a debriefing, discussing each case in detail. Two subject matter experts were always available, and occasionally 4 were present to provide additional knowledge transfer to learners. These included board-certified physicians in internal medicine and pulmonary critical care. Most scenarios were conducted on Wednesday afternoon or Thursday.

The CIL provided 6 staff minimum for every event. The staff controlled the manikins and acted as embedded players for the learners to interact and work with at the bedside. Every embedded RN was provided the same script: They were a new nurse just off orientation and did not know what to do. In addition, they were instructed that no matter who the learner wanted to call/page, that person or service was not answering or unavailable. This forced learners to respond and treat the simulated patient on their own.

Survey Responses

To evaluate the effect of this program on medical education, we administered surveys to the trainees before and after the simulation (Appendix). All questions were evaluated on a 10-point Likert scale (1, minimal comfort; 10, maximum comfort). The postsurvey added an additional Likert scale question and an open-ended question.

Sixteen trainees underwent the simulation curriculum during the 2022 to 2023 academic year, 9 internal medicine PGY1 residents, 4 medical students, and 3 physician assistant students. Postsimulation surveys indicated a mean 2.2 point increase in comfort compared with the presimulation surveys across all questions and participants.

DISCUSSION

The simulation curriculum proved to be successful for all parties, including trainees, medical educators, and simulation staff. Trainees expressed gratitude for the teaching ability of the simulation and the challenge of confronting an evolving scenario. Students also stated that the simulation allowed them to identify knowledge weaknesses.

Medical technology is rapidly advancing. A study evaluating high-fidelity medical simulations between 1969 and 2003 found that they are educationally effective and complement other medical education modalities.6 It is also noted that care provided by junior physicians with a lack of prior exposure to emergencies and unusual clinical syndromes can lead to more adverse effects.7 Simulation curriculums can be used to educate junior physicians as well as trainees on a multitude of medical emergencies, teach systematic approaches to medical scenarios, and increase exposure to unfamiliar experiences.

The goals of this article are to share program details and encourage other training programs with similar capabilities to incorporate simulation into medical education. Using pre- and postsimulation surveys, there was a concrete improvement in the value obtained by participating in this simulation. The Nightmare on CIL Street learners experienced a mean 2.2 point improvement from presimulation survey to postsimulation survey. Some notable improvements were the feelings of preparedness for rapid response situations and developing a systematic approach. As the students who participated in our Nightmare on CIL Street simulation were early in training, we believe the improvement in preparation and developing a systematic approach can be key to their success in their practical environments.

From a site-specific standpoint, improvement in confidence working through cardiac, respiratory, and neurological emergencies will be very useful. The anesthesiology service intubates during respiratory failures and there is no stroke neurologist available at the CTVHCS hospital. Giving trainees experience in these conditions may allow them to better understand their role in coordination during these times and potentially improve patient outcomes. A follow-up questionnaire administered a year after this simulation may be useful in ascertaining the usefulness of the simulation and what items may have been approached differently. We encourage other institutions to build in aspects of their site-specific challenges to improve trainee awareness in approaches to critical scenarios.

Challenges

The greatest challenge for Nightmare on CIL Street was the ability to pull internal medicine residents from their clinical duties to participate in the simulation. As there are many moving parts to their clinical scheduling, residents do not always have sufficient coverage to participate in training. There were also instances where residents needed to cover for another resident preventing them from attending the simulation. In the future, this program will schedule residents months in advance and will have the simulation training built into their rotations.

Medical and physician assistant students were pulled from their ward rotations as well. They rotate on a 2-to-4-week basis and often had already experienced the simulation the week prior, leaving out students for the following week. With more longitudinal planning, students can be pulled on a rotating monthly basis to maximize their participation. Another challenge was deciding whether residents should partner or experience the simulation on their own. After some feedback, it was noted that residents preferred to experience the simulation on their own as this improves their learning value. With the limited resources available, only rotating 3 residents on a scenario limits the number of trainees who can be reached with the program. Running this program throughout an academic year can help to reach more trainees.

CONCLUSIONS

Educating trainees on rapid response scenarios by using a simulation curriculum provides many benefits. Our trainees reported improvement in addressing cardiac, respiratory, and neurological rapid response scenarios after experiencing the simulation. They felt better prepared and had developed a better systematic approach for the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pawan Sikka, MD, George Martinez, MD and Braden Anderson, MD for participating as physician experts and educating our students. We thank Naomi Devers; Dinetra Jones; Stephanie Garrett; Sara Holton; Evelina Bartnick; Tanelle Smith; Michael Lomax; Shaun Kelemen for their participation as nurses, assistants, and simulation technology experts.

1. Guze PA. Using technology to meet the challenges of medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:260-270.

2. Higgins M, Madan C, Patel R. Development and decay of procedural skills in surgery: a systematic review of the effectiveness of simulation-based medical education interventions. Surgeon. 2021;19(4):e67-e77. doi:10.1016/j.surge.2020.07.013

3. Lyons PG, Edelson DP, Carey KA, et al. Characteristics of rapid response calls in the United States: an analysis of the first 402,023 adult cases from the Get With the Guidelines Resuscitation-Medical Emergency Team registry. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(10):1283-1289. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000003912

4. McMurray L, Hall AK, Rich J, Merchant S, Chaplin T. The nightmares course: a longitudinal, multidisciplinary, simulation-based curriculum to train and assess resident competence in resuscitation. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):503-508. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00462.1

5. Gilic F, Schultz K, Sempowski I, Blagojevic A. “Nightmares-Family Medicine” course is an effective acute care teaching tool for family medicine residents. Simul Healthc. 2019;14(3):157-162. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000355

6. Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005;27(1):10-28. doi:10.1080/01421590500046924

7. Datta R, Upadhyay K, Jaideep C. Simulation and its role in medical education. Med J Armed Forces India. 2012;68(2):167-172. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(12)60040-9

The Central Texas Veteran’s Health Care System (CTVHCS) in Temple, Texas, is a 189-bed teaching hospital. CTVHCS opened the Center for Innovation and Learning (CIL) in 2022. The CIL has about 279 m2 of simulation space that includes high- and low-fidelity simulation equipment and multiple laboratories, which can be used to simulate inpatient and outpatient settings. The CIL high-fidelity manikins and environment allow learners to be immersed in the simulation for maximum realism. Computer and video systems provide clear viewing of training, which allows for more in-depth debriefing and learning. CIL simulation training is used by CTVHCS staff, medical residents, and medical and physician assistant students.

The utility of technology in medical education is rapidly evolving. As noted in many studies, simulation creates an environment that can imitate real patients in the format of a lifelike manikin, anatomic regions stations, clinical tasks, and many real-life circumstances.1 Task trainers for procedure simulation have been widely used and studied. A 2020 study noted that simulation training is effective for developing procedural skills in surgery and prevents the decay of surgical skills.2

In reviewing health care education curriculums, we noted that most of the rapid response situations are learned through active patient experiences. Rapid responses are managed by the intensive care unit and primary care teams during the day but at night are run primarily by the postgraduate year 2 (PGY2) night resident and intern. Knowing these logistics and current studies, we decided to build a rapid response simulation curriculum to improve preparedness for PGY1 residents, medical students, and physician assistant students.

Curriculum Planning

Planning the simulation curriculum began with the CTVHCS internal medicine chief resident and registered nurse (RN) educator. CTVHCS data were reviewed to identify the 3 most common rapid response calls from the past 3 years; research on the most common systems affected by rapid responses also was evaluated.

A 2019 study by Lyons and colleagues evaluated 402,023 rapid response activations across 360 hospitals and found that respiratory scenarios made up 38% and cardiac scenarios made up 37%.3 In addition, the CTVHCS has limited support in stroke neurology. Therefore, the internal medicine chief resident and RN educator decided to run 3 evolving rapid response scenarios per session that included cardiac, respiratory, and neurological scenarios. Capabilities and limitations of different high-fidelity manikins were discussed to identify and use the most appropriate simulator for each situation. Objectives that met both general medicine and site-specific education were discussed, and the program was formulated.

Program Description

Nightmare on CIL Street is a simulation-based program designed for new internal medicine residents and students to encounter difficult situations (late at night, on call, or when resources are limited; ie, weekends/holidays) in a controlled simulation environment. During the simulation, learners will be unable to transfer the patient and no additional help is available. Each learner must determine a differential diagnosis and make appropriate medical interventions with only the assistance of a nurse. Scenarios are derived from common rapid response team calls and low-volume/high-impact situations where clinical decisions must be made quickly to ensure the best patient outcomes. High-fidelity manikins that have abilities to respond to questions, simulate breathing, reproduce pathological heart and breath sounds and more are used to create a realistic patient environment.

This program aligns with 2 national Veterans Health Administration priorities: (1) connect veterans to the soonest and best care; and (2) accelerate the Veterans Health Administration journey to be a high-reliability organization (sensitivity to operations, preoccupation with failure, commitment to resilience, and deference to expertise). Nightmare on CIL Street has 3 clinical episodes: 2 cardiac (A Tell-Tale Heart), respiratory (Don’t Breathe), and neurologic (Brain Scan). Additional clinical episodes will be added based on learner feedback and assessed need.

Each simulation event encompassed all 3 episodes that an individual or a team of 2 learners rotate through in a round-robin fashion. The overarching theme for each episode was a rapid response team call with minimal resources that the learner would have to provide care and stabilization. A literature search for rapid response team training programs found few results, but the literature assisted with providing a foundation for Nightmare on CIL Street.4,5 The goal was to completely envelop the learners in a nightmare scenario that required a solution.

After the safety brief and predata collection, learners received a phone call with minimal information about a patient in need of care. The learners responded to the requested area and provided treatment to the emergency over 25 minutes with the bedside nurse (who is an embedded participant). At the conclusion of the scenario, a physician subject matter expert who has been observing, provided a personalized 10-minute debriefing to the learner, which presented specific learning points and opportunities for the learner’s educational development. After the debriefing, learners returned to a conference room and awaited the next call. After all learners completed the 3 episodes, a group debriefing was conducted using the gather, analyze, summarize debriefing framework. The debriefing begins with an open-ended forum for learners to express their thoughts. Then, each scenario is discussed and broken down by key learning objectives. Starting with cardiac and ending with neurology, the logistics of the cases are discussed based on the trajectory of the learners during the scenarios. Each objective is discussed, and learners are allowed to ask questions before moving to the next scenario. After the debriefing, postevent data were gathered.

Objectives

The program objective was to educate residents and students on common rapid response scenarios. We devised each scenario as an evolving simulation where various interventions would improve or worsen vital signs and symptoms. Each scenario had an end goal: cardioversion (cardiac), intubation (respiratory), and transfer (neurologic). Objectives were tailored to the trainees present during the specific simulation (Table).

IMPLEMENTATION

The initial run of the simulation curriculum was implemented on February 22, 2023, and ended on May 17, 2023, with 5 events. Participants included internal medicine PGY1 residents, third-year medical students, and fourth-year physician assistant students. Internal medicine residents ran each scenario with a subject matter expert monitoring; the undergraduate medical trainees partnered with another student. Students were pulled from their ward rotations to attend the simulation, and residents were pulled from electives and wards. Each trainee was able to experience each planned scenario. They were then briefed, participated in each scenario, and ended with a debriefing, discussing each case in detail. Two subject matter experts were always available, and occasionally 4 were present to provide additional knowledge transfer to learners. These included board-certified physicians in internal medicine and pulmonary critical care. Most scenarios were conducted on Wednesday afternoon or Thursday.

The CIL provided 6 staff minimum for every event. The staff controlled the manikins and acted as embedded players for the learners to interact and work with at the bedside. Every embedded RN was provided the same script: They were a new nurse just off orientation and did not know what to do. In addition, they were instructed that no matter who the learner wanted to call/page, that person or service was not answering or unavailable. This forced learners to respond and treat the simulated patient on their own.

Survey Responses

To evaluate the effect of this program on medical education, we administered surveys to the trainees before and after the simulation (Appendix). All questions were evaluated on a 10-point Likert scale (1, minimal comfort; 10, maximum comfort). The postsurvey added an additional Likert scale question and an open-ended question.

Sixteen trainees underwent the simulation curriculum during the 2022 to 2023 academic year, 9 internal medicine PGY1 residents, 4 medical students, and 3 physician assistant students. Postsimulation surveys indicated a mean 2.2 point increase in comfort compared with the presimulation surveys across all questions and participants.

DISCUSSION

The simulation curriculum proved to be successful for all parties, including trainees, medical educators, and simulation staff. Trainees expressed gratitude for the teaching ability of the simulation and the challenge of confronting an evolving scenario. Students also stated that the simulation allowed them to identify knowledge weaknesses.

Medical technology is rapidly advancing. A study evaluating high-fidelity medical simulations between 1969 and 2003 found that they are educationally effective and complement other medical education modalities.6 It is also noted that care provided by junior physicians with a lack of prior exposure to emergencies and unusual clinical syndromes can lead to more adverse effects.7 Simulation curriculums can be used to educate junior physicians as well as trainees on a multitude of medical emergencies, teach systematic approaches to medical scenarios, and increase exposure to unfamiliar experiences.

The goals of this article are to share program details and encourage other training programs with similar capabilities to incorporate simulation into medical education. Using pre- and postsimulation surveys, there was a concrete improvement in the value obtained by participating in this simulation. The Nightmare on CIL Street learners experienced a mean 2.2 point improvement from presimulation survey to postsimulation survey. Some notable improvements were the feelings of preparedness for rapid response situations and developing a systematic approach. As the students who participated in our Nightmare on CIL Street simulation were early in training, we believe the improvement in preparation and developing a systematic approach can be key to their success in their practical environments.

From a site-specific standpoint, improvement in confidence working through cardiac, respiratory, and neurological emergencies will be very useful. The anesthesiology service intubates during respiratory failures and there is no stroke neurologist available at the CTVHCS hospital. Giving trainees experience in these conditions may allow them to better understand their role in coordination during these times and potentially improve patient outcomes. A follow-up questionnaire administered a year after this simulation may be useful in ascertaining the usefulness of the simulation and what items may have been approached differently. We encourage other institutions to build in aspects of their site-specific challenges to improve trainee awareness in approaches to critical scenarios.

Challenges

The greatest challenge for Nightmare on CIL Street was the ability to pull internal medicine residents from their clinical duties to participate in the simulation. As there are many moving parts to their clinical scheduling, residents do not always have sufficient coverage to participate in training. There were also instances where residents needed to cover for another resident preventing them from attending the simulation. In the future, this program will schedule residents months in advance and will have the simulation training built into their rotations.

Medical and physician assistant students were pulled from their ward rotations as well. They rotate on a 2-to-4-week basis and often had already experienced the simulation the week prior, leaving out students for the following week. With more longitudinal planning, students can be pulled on a rotating monthly basis to maximize their participation. Another challenge was deciding whether residents should partner or experience the simulation on their own. After some feedback, it was noted that residents preferred to experience the simulation on their own as this improves their learning value. With the limited resources available, only rotating 3 residents on a scenario limits the number of trainees who can be reached with the program. Running this program throughout an academic year can help to reach more trainees.

CONCLUSIONS

Educating trainees on rapid response scenarios by using a simulation curriculum provides many benefits. Our trainees reported improvement in addressing cardiac, respiratory, and neurological rapid response scenarios after experiencing the simulation. They felt better prepared and had developed a better systematic approach for the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pawan Sikka, MD, George Martinez, MD and Braden Anderson, MD for participating as physician experts and educating our students. We thank Naomi Devers; Dinetra Jones; Stephanie Garrett; Sara Holton; Evelina Bartnick; Tanelle Smith; Michael Lomax; Shaun Kelemen for their participation as nurses, assistants, and simulation technology experts.

The Central Texas Veteran’s Health Care System (CTVHCS) in Temple, Texas, is a 189-bed teaching hospital. CTVHCS opened the Center for Innovation and Learning (CIL) in 2022. The CIL has about 279 m2 of simulation space that includes high- and low-fidelity simulation equipment and multiple laboratories, which can be used to simulate inpatient and outpatient settings. The CIL high-fidelity manikins and environment allow learners to be immersed in the simulation for maximum realism. Computer and video systems provide clear viewing of training, which allows for more in-depth debriefing and learning. CIL simulation training is used by CTVHCS staff, medical residents, and medical and physician assistant students.

The utility of technology in medical education is rapidly evolving. As noted in many studies, simulation creates an environment that can imitate real patients in the format of a lifelike manikin, anatomic regions stations, clinical tasks, and many real-life circumstances.1 Task trainers for procedure simulation have been widely used and studied. A 2020 study noted that simulation training is effective for developing procedural skills in surgery and prevents the decay of surgical skills.2

In reviewing health care education curriculums, we noted that most of the rapid response situations are learned through active patient experiences. Rapid responses are managed by the intensive care unit and primary care teams during the day but at night are run primarily by the postgraduate year 2 (PGY2) night resident and intern. Knowing these logistics and current studies, we decided to build a rapid response simulation curriculum to improve preparedness for PGY1 residents, medical students, and physician assistant students.

Curriculum Planning

Planning the simulation curriculum began with the CTVHCS internal medicine chief resident and registered nurse (RN) educator. CTVHCS data were reviewed to identify the 3 most common rapid response calls from the past 3 years; research on the most common systems affected by rapid responses also was evaluated.

A 2019 study by Lyons and colleagues evaluated 402,023 rapid response activations across 360 hospitals and found that respiratory scenarios made up 38% and cardiac scenarios made up 37%.3 In addition, the CTVHCS has limited support in stroke neurology. Therefore, the internal medicine chief resident and RN educator decided to run 3 evolving rapid response scenarios per session that included cardiac, respiratory, and neurological scenarios. Capabilities and limitations of different high-fidelity manikins were discussed to identify and use the most appropriate simulator for each situation. Objectives that met both general medicine and site-specific education were discussed, and the program was formulated.

Program Description

Nightmare on CIL Street is a simulation-based program designed for new internal medicine residents and students to encounter difficult situations (late at night, on call, or when resources are limited; ie, weekends/holidays) in a controlled simulation environment. During the simulation, learners will be unable to transfer the patient and no additional help is available. Each learner must determine a differential diagnosis and make appropriate medical interventions with only the assistance of a nurse. Scenarios are derived from common rapid response team calls and low-volume/high-impact situations where clinical decisions must be made quickly to ensure the best patient outcomes. High-fidelity manikins that have abilities to respond to questions, simulate breathing, reproduce pathological heart and breath sounds and more are used to create a realistic patient environment.

This program aligns with 2 national Veterans Health Administration priorities: (1) connect veterans to the soonest and best care; and (2) accelerate the Veterans Health Administration journey to be a high-reliability organization (sensitivity to operations, preoccupation with failure, commitment to resilience, and deference to expertise). Nightmare on CIL Street has 3 clinical episodes: 2 cardiac (A Tell-Tale Heart), respiratory (Don’t Breathe), and neurologic (Brain Scan). Additional clinical episodes will be added based on learner feedback and assessed need.

Each simulation event encompassed all 3 episodes that an individual or a team of 2 learners rotate through in a round-robin fashion. The overarching theme for each episode was a rapid response team call with minimal resources that the learner would have to provide care and stabilization. A literature search for rapid response team training programs found few results, but the literature assisted with providing a foundation for Nightmare on CIL Street.4,5 The goal was to completely envelop the learners in a nightmare scenario that required a solution.

After the safety brief and predata collection, learners received a phone call with minimal information about a patient in need of care. The learners responded to the requested area and provided treatment to the emergency over 25 minutes with the bedside nurse (who is an embedded participant). At the conclusion of the scenario, a physician subject matter expert who has been observing, provided a personalized 10-minute debriefing to the learner, which presented specific learning points and opportunities for the learner’s educational development. After the debriefing, learners returned to a conference room and awaited the next call. After all learners completed the 3 episodes, a group debriefing was conducted using the gather, analyze, summarize debriefing framework. The debriefing begins with an open-ended forum for learners to express their thoughts. Then, each scenario is discussed and broken down by key learning objectives. Starting with cardiac and ending with neurology, the logistics of the cases are discussed based on the trajectory of the learners during the scenarios. Each objective is discussed, and learners are allowed to ask questions before moving to the next scenario. After the debriefing, postevent data were gathered.

Objectives

The program objective was to educate residents and students on common rapid response scenarios. We devised each scenario as an evolving simulation where various interventions would improve or worsen vital signs and symptoms. Each scenario had an end goal: cardioversion (cardiac), intubation (respiratory), and transfer (neurologic). Objectives were tailored to the trainees present during the specific simulation (Table).

IMPLEMENTATION

The initial run of the simulation curriculum was implemented on February 22, 2023, and ended on May 17, 2023, with 5 events. Participants included internal medicine PGY1 residents, third-year medical students, and fourth-year physician assistant students. Internal medicine residents ran each scenario with a subject matter expert monitoring; the undergraduate medical trainees partnered with another student. Students were pulled from their ward rotations to attend the simulation, and residents were pulled from electives and wards. Each trainee was able to experience each planned scenario. They were then briefed, participated in each scenario, and ended with a debriefing, discussing each case in detail. Two subject matter experts were always available, and occasionally 4 were present to provide additional knowledge transfer to learners. These included board-certified physicians in internal medicine and pulmonary critical care. Most scenarios were conducted on Wednesday afternoon or Thursday.

The CIL provided 6 staff minimum for every event. The staff controlled the manikins and acted as embedded players for the learners to interact and work with at the bedside. Every embedded RN was provided the same script: They were a new nurse just off orientation and did not know what to do. In addition, they were instructed that no matter who the learner wanted to call/page, that person or service was not answering or unavailable. This forced learners to respond and treat the simulated patient on their own.

Survey Responses

To evaluate the effect of this program on medical education, we administered surveys to the trainees before and after the simulation (Appendix). All questions were evaluated on a 10-point Likert scale (1, minimal comfort; 10, maximum comfort). The postsurvey added an additional Likert scale question and an open-ended question.

Sixteen trainees underwent the simulation curriculum during the 2022 to 2023 academic year, 9 internal medicine PGY1 residents, 4 medical students, and 3 physician assistant students. Postsimulation surveys indicated a mean 2.2 point increase in comfort compared with the presimulation surveys across all questions and participants.

DISCUSSION

The simulation curriculum proved to be successful for all parties, including trainees, medical educators, and simulation staff. Trainees expressed gratitude for the teaching ability of the simulation and the challenge of confronting an evolving scenario. Students also stated that the simulation allowed them to identify knowledge weaknesses.

Medical technology is rapidly advancing. A study evaluating high-fidelity medical simulations between 1969 and 2003 found that they are educationally effective and complement other medical education modalities.6 It is also noted that care provided by junior physicians with a lack of prior exposure to emergencies and unusual clinical syndromes can lead to more adverse effects.7 Simulation curriculums can be used to educate junior physicians as well as trainees on a multitude of medical emergencies, teach systematic approaches to medical scenarios, and increase exposure to unfamiliar experiences.

The goals of this article are to share program details and encourage other training programs with similar capabilities to incorporate simulation into medical education. Using pre- and postsimulation surveys, there was a concrete improvement in the value obtained by participating in this simulation. The Nightmare on CIL Street learners experienced a mean 2.2 point improvement from presimulation survey to postsimulation survey. Some notable improvements were the feelings of preparedness for rapid response situations and developing a systematic approach. As the students who participated in our Nightmare on CIL Street simulation were early in training, we believe the improvement in preparation and developing a systematic approach can be key to their success in their practical environments.

From a site-specific standpoint, improvement in confidence working through cardiac, respiratory, and neurological emergencies will be very useful. The anesthesiology service intubates during respiratory failures and there is no stroke neurologist available at the CTVHCS hospital. Giving trainees experience in these conditions may allow them to better understand their role in coordination during these times and potentially improve patient outcomes. A follow-up questionnaire administered a year after this simulation may be useful in ascertaining the usefulness of the simulation and what items may have been approached differently. We encourage other institutions to build in aspects of their site-specific challenges to improve trainee awareness in approaches to critical scenarios.

Challenges

The greatest challenge for Nightmare on CIL Street was the ability to pull internal medicine residents from their clinical duties to participate in the simulation. As there are many moving parts to their clinical scheduling, residents do not always have sufficient coverage to participate in training. There were also instances where residents needed to cover for another resident preventing them from attending the simulation. In the future, this program will schedule residents months in advance and will have the simulation training built into their rotations.

Medical and physician assistant students were pulled from their ward rotations as well. They rotate on a 2-to-4-week basis and often had already experienced the simulation the week prior, leaving out students for the following week. With more longitudinal planning, students can be pulled on a rotating monthly basis to maximize their participation. Another challenge was deciding whether residents should partner or experience the simulation on their own. After some feedback, it was noted that residents preferred to experience the simulation on their own as this improves their learning value. With the limited resources available, only rotating 3 residents on a scenario limits the number of trainees who can be reached with the program. Running this program throughout an academic year can help to reach more trainees.

CONCLUSIONS

Educating trainees on rapid response scenarios by using a simulation curriculum provides many benefits. Our trainees reported improvement in addressing cardiac, respiratory, and neurological rapid response scenarios after experiencing the simulation. They felt better prepared and had developed a better systematic approach for the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pawan Sikka, MD, George Martinez, MD and Braden Anderson, MD for participating as physician experts and educating our students. We thank Naomi Devers; Dinetra Jones; Stephanie Garrett; Sara Holton; Evelina Bartnick; Tanelle Smith; Michael Lomax; Shaun Kelemen for their participation as nurses, assistants, and simulation technology experts.

1. Guze PA. Using technology to meet the challenges of medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:260-270.

2. Higgins M, Madan C, Patel R. Development and decay of procedural skills in surgery: a systematic review of the effectiveness of simulation-based medical education interventions. Surgeon. 2021;19(4):e67-e77. doi:10.1016/j.surge.2020.07.013

3. Lyons PG, Edelson DP, Carey KA, et al. Characteristics of rapid response calls in the United States: an analysis of the first 402,023 adult cases from the Get With the Guidelines Resuscitation-Medical Emergency Team registry. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(10):1283-1289. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000003912

4. McMurray L, Hall AK, Rich J, Merchant S, Chaplin T. The nightmares course: a longitudinal, multidisciplinary, simulation-based curriculum to train and assess resident competence in resuscitation. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):503-508. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00462.1

5. Gilic F, Schultz K, Sempowski I, Blagojevic A. “Nightmares-Family Medicine” course is an effective acute care teaching tool for family medicine residents. Simul Healthc. 2019;14(3):157-162. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000355

6. Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005;27(1):10-28. doi:10.1080/01421590500046924

7. Datta R, Upadhyay K, Jaideep C. Simulation and its role in medical education. Med J Armed Forces India. 2012;68(2):167-172. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(12)60040-9

1. Guze PA. Using technology to meet the challenges of medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:260-270.

2. Higgins M, Madan C, Patel R. Development and decay of procedural skills in surgery: a systematic review of the effectiveness of simulation-based medical education interventions. Surgeon. 2021;19(4):e67-e77. doi:10.1016/j.surge.2020.07.013

3. Lyons PG, Edelson DP, Carey KA, et al. Characteristics of rapid response calls in the United States: an analysis of the first 402,023 adult cases from the Get With the Guidelines Resuscitation-Medical Emergency Team registry. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(10):1283-1289. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000003912

4. McMurray L, Hall AK, Rich J, Merchant S, Chaplin T. The nightmares course: a longitudinal, multidisciplinary, simulation-based curriculum to train and assess resident competence in resuscitation. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):503-508. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00462.1

5. Gilic F, Schultz K, Sempowski I, Blagojevic A. “Nightmares-Family Medicine” course is an effective acute care teaching tool for family medicine residents. Simul Healthc. 2019;14(3):157-162. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000355

6. Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005;27(1):10-28. doi:10.1080/01421590500046924

7. Datta R, Upadhyay K, Jaideep C. Simulation and its role in medical education. Med J Armed Forces India. 2012;68(2):167-172. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(12)60040-9

Second pig heart recipient dies

the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC), Baltimore, reported in a statement.

Mr. Faucette, a former lab tech who was turned down repeatedly for a standard allograft transplantation because of his various medical conditions, received the pig heart transplant on Sept. 20, 2023.

He first came to UMMC as a patient on Sept. 14. When he was admitted, he was in end-stage heart failure. Shortly before the surgery, his heart stopped, and he required resuscitation.

On Sept. 15, the Food and Drug Administration granted an emergency authorization for the surgery through its single-patient investigational new drug compassionate use pathway.

“My only real hope left is to go with the pig heart, the xenotransplant,” Mr. Faucette said in an interview from his hospital room a few days before his surgery. “At least now I have hope, and I have a chance.” He made “significant progress” in the month after the surgery, participating in physical therapy and spending time with family, according to the university. But in the days before his death, the heart showed signs of rejection.

“Mr. Faucette’s last wish was for us to make the most of what we have learned from our experience, so others may be guaranteed a chance for a new heart when a human organ is unavailable,” said Bartley P. Griffith, MD, who transplanted the pig heart into Mr. Faucette at UMMC. “He then told the team of doctors and nurses who gathered around him that he loved us. We will miss him tremendously.”

Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, MD, professor of surgery and scientific/program director of the Cardiac Xenotransplantation Program at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, said that “Mr. Faucette was a scientist who not only read and interpreted his own biopsies, but who understood the important contribution he was making in advancing the field.

“As with the first patient, David Bennett Sr., we intend to conduct an extensive analysis to identify factors that can be prevented in future transplants; this will allow us to continue to move forward and educate our colleagues in the field on our experience,” Dr. Mohiuddin added.

The researchers don’t plan to make further comments until their investigation is complete, a university spokesperson said in an interview.

UMMC performed the first transplant of a genetically modified pig heart in January 2022. Mr. Bennett, the recipient of that heart, survived for 60 days. The researchers published their initial findings in The New England Journal of Medicine, and then the results of their follow-up investigation in The Lancet.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC), Baltimore, reported in a statement.

Mr. Faucette, a former lab tech who was turned down repeatedly for a standard allograft transplantation because of his various medical conditions, received the pig heart transplant on Sept. 20, 2023.

He first came to UMMC as a patient on Sept. 14. When he was admitted, he was in end-stage heart failure. Shortly before the surgery, his heart stopped, and he required resuscitation.

On Sept. 15, the Food and Drug Administration granted an emergency authorization for the surgery through its single-patient investigational new drug compassionate use pathway.

“My only real hope left is to go with the pig heart, the xenotransplant,” Mr. Faucette said in an interview from his hospital room a few days before his surgery. “At least now I have hope, and I have a chance.” He made “significant progress” in the month after the surgery, participating in physical therapy and spending time with family, according to the university. But in the days before his death, the heart showed signs of rejection.

“Mr. Faucette’s last wish was for us to make the most of what we have learned from our experience, so others may be guaranteed a chance for a new heart when a human organ is unavailable,” said Bartley P. Griffith, MD, who transplanted the pig heart into Mr. Faucette at UMMC. “He then told the team of doctors and nurses who gathered around him that he loved us. We will miss him tremendously.”

Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, MD, professor of surgery and scientific/program director of the Cardiac Xenotransplantation Program at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, said that “Mr. Faucette was a scientist who not only read and interpreted his own biopsies, but who understood the important contribution he was making in advancing the field.

“As with the first patient, David Bennett Sr., we intend to conduct an extensive analysis to identify factors that can be prevented in future transplants; this will allow us to continue to move forward and educate our colleagues in the field on our experience,” Dr. Mohiuddin added.

The researchers don’t plan to make further comments until their investigation is complete, a university spokesperson said in an interview.

UMMC performed the first transplant of a genetically modified pig heart in January 2022. Mr. Bennett, the recipient of that heart, survived for 60 days. The researchers published their initial findings in The New England Journal of Medicine, and then the results of their follow-up investigation in The Lancet.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC), Baltimore, reported in a statement.

Mr. Faucette, a former lab tech who was turned down repeatedly for a standard allograft transplantation because of his various medical conditions, received the pig heart transplant on Sept. 20, 2023.

He first came to UMMC as a patient on Sept. 14. When he was admitted, he was in end-stage heart failure. Shortly before the surgery, his heart stopped, and he required resuscitation.

On Sept. 15, the Food and Drug Administration granted an emergency authorization for the surgery through its single-patient investigational new drug compassionate use pathway.

“My only real hope left is to go with the pig heart, the xenotransplant,” Mr. Faucette said in an interview from his hospital room a few days before his surgery. “At least now I have hope, and I have a chance.” He made “significant progress” in the month after the surgery, participating in physical therapy and spending time with family, according to the university. But in the days before his death, the heart showed signs of rejection.

“Mr. Faucette’s last wish was for us to make the most of what we have learned from our experience, so others may be guaranteed a chance for a new heart when a human organ is unavailable,” said Bartley P. Griffith, MD, who transplanted the pig heart into Mr. Faucette at UMMC. “He then told the team of doctors and nurses who gathered around him that he loved us. We will miss him tremendously.”

Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, MD, professor of surgery and scientific/program director of the Cardiac Xenotransplantation Program at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, said that “Mr. Faucette was a scientist who not only read and interpreted his own biopsies, but who understood the important contribution he was making in advancing the field.

“As with the first patient, David Bennett Sr., we intend to conduct an extensive analysis to identify factors that can be prevented in future transplants; this will allow us to continue to move forward and educate our colleagues in the field on our experience,” Dr. Mohiuddin added.

The researchers don’t plan to make further comments until their investigation is complete, a university spokesperson said in an interview.

UMMC performed the first transplant of a genetically modified pig heart in January 2022. Mr. Bennett, the recipient of that heart, survived for 60 days. The researchers published their initial findings in The New England Journal of Medicine, and then the results of their follow-up investigation in The Lancet.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Another study ties statins to T2D: Should practice change?

Studies have shown links between statin use and type 2 diabetes (T2D) for more than a decade. A U.S. Food and Drug Administration label change for the drugs warned in 2012 about reports of increased risks of high blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin (A1c) levels. However, in the same warning, the FDA said it “continues to believe that the cardiovascular benefits of statins outweigh these small increased risks.”

Indeed, although the warning triggered much discussion at the time and a number of meta-analyses and other observational studies in more recent years, that conclusion seems to hold among clinicians and society guidelines.

For example, in a recent practice pointer on the risk of diabetes with statins published in the BMJ, Ishak Mansi, MD, of the Orlando VA Health Care System, and colleagues write, “This potential adverse effect of diabetes with statin use should not be a barrier to starting statin treatment when indicated.”

They also called for further research to answer such questions as, “Is statin-associated diabetes reversible upon statin discontinuation? Would intermittent use minimize this risk while maintaining cardiovascular benefits?”

An earlier study among individuals at high risk for diabetes found significantly higher rates of incident diabetes at 10 years among patients on placebo, metformin, or lifestyle intervention who also initiated statin therapy. Jill Crandall, MD, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and colleagues conclude, “For individual patients, a potential modest increase in diabetes risk clearly needs to be balanced against the consistent and highly significant reductions in myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death associated with statin treatment.”

In the same vein, a recent review by Byron Hoogwerf, MD, Emeritus, department of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism, Cleveland Clinic, is titled, “Statins may increase diabetes, but benefit still outweighs risk.”

Rosuvastatin versus Atorvastatin

The latest study in this arena is an analysis of the LODESTAR randomized controlled trial of 4,400 patients with coronary artery disease in 12 hospitals in Korea which compares the risks associated with individual statins.

Senior author Myeong-Ki Hong, MD, PhD, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Seoul, South Korea, said in an interview that the study was prompted by the “limited” studies evaluating clinical outcomes, including diabetes risk, according to statin type.

Dr. Hong and colleagues compared the risk of developing diabetes among those taking rosuvastatin (mean daily dose, 17.1 mg) or atorvastatin (mean daily dose 36 mg) for 3 years. While both statins effectively prevented myocardial infarction, stroke, and death, (2.5% vs. 1.5%; HR, 1.66).

Overall, the HR of new-onset T2D was 1.29 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.63; P = .04).

“The percentages of new-onset diabetes and cataract are in line with previous studies regarding statin therapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Hong said. “Additional research specifically focusing on these outcomes is required, with more frequent measurement of glucose and A1c levels to detect new-onset diabetes and regular ophthalmologic examinations to detect cataracts.”

“However,” he added, “when using rosuvastatin over atorvastatin, we ... emphasize the importance of meticulous monitoring and appropriate lifestyle interventions to mitigate the risk of new-onset diabetes or cataracts.”

Steven Nissen, MD, chief academic officer of Cleveland Clinic’s Heart and Vascular Institute, was not convinced, and said the study “does not provide useful insights into the use of these drugs.”

The investigators used whatever dose they wanted, “and the authors report only the median dose after 3 years,” he said in an interview. “Because there was a slightly greater reduction in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol with rosuvastatin, the relative dose was actually higher.”

“We know that new-onset diabetes with statins is dose-dependent,” he said. “The P-values for diabetes incidence were marginal (very close to P = .05). Accordingly, the diabetes data are unconvincing. ... The similar efficacy is not surprising given the open-label dosing with relatively similar effects on lipids.”

Seth Shay Martin, MD, MHS, director of the Advanced Lipid Disorders Program and Digital Health Lab, Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, also commented on the results. The findings are “in line with existing knowledge and current guidelines,” he said. “Therefore, the study should not influence prescribing.”

“Although the study suggests that rosuvastatin was associated with a higher risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus requiring antidiabetics and cataract surgery, compared with atorvastatin, these findings should be interpreted with caution given the open-label nature of the study and require further investigation,” he said.

“The mean daily doses of statins were somewhat below target for secondary prevention,” he noted. “Ideally, patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) take 20-40 mg daily of rosuvastatin or 40-80 mg daily of atorvastatin.”

“Furthermore, the LDL cholesterol levels were not optimized in the patients,” he said. “The mean LDL-C was 1.8-1.9 mmol/L, which is equivalent to 70-73 mg/dL. In the current treatment era, we generally treat to LDL-C levels less than 70 mg/dL and often less than 55 mg/dL in CAD patients.”

“The cataracts finding is particularly odd,” he added. “There was historic concern for cataracts with statin therapy, initially because of studies in beagle dogs. However, high-quality evidence from statin trials has not shown a risk for cataracts.”

So which statin has the lowest risk of triggering new-onset diabetes? As Dr. Hong noted, the literature is sparse when it comes to comparing the risk among specific statins. Some studies suggest that the risk may depend on the individual and their specific risk factors, as well as the dose and intensity of the prescribed statin.

One recent study suggests that while the overall chance of developing diabetes is small, when looking at risk by years of exposure, atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, and lovastatin carried the largest risk, whereas the risk was lower with pravastatin and simvastatin.

Risks also seemed lower with fluvastatin and pitavastatin, but there were too few study patients taking those drugs long-term to include in the subanalysis.

With input from the latest guidelines from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association, as well as findings from a clinical guide on statin-associated diabetes, Dr. Hoogwerf suggests in his review that shared decision-making before starting statin therapy of any type include the following considerations/discussion points:

- For all patients: Screening to determine baseline glycemic status; nonstatin therapies to lower cholesterol; and variables associated with an increased risk of diabetes, including antihypertensive drugs.

- For patients without T2D: The possibility of developing T2D, types and doses of statins, and the fact that statin benefits “generally far outweigh” risks of developing diabetes.

- For patients with T2D: Possible small adverse effects on glycemic control; statin benefits in reducing risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, which “significantly outweigh” the small increase in A1c; and mitigation of adverse glycemic effects of statins with glucose-lowering therapies.