User login

Potential dapagliflozin benefit post MI is not a ‘mandate’

PHILADELPHIA – Giving the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) to patients with acute myocardial infarction and impaired left ventricular systolic function but no diabetes or chronic heart failure significantly improved a composite of cardiovascular outcomes, a European registry-based randomized trial suggests.

In presenting these results from the DAPA-MI trial, Stefan James, MD, of Uppsala University (Sweden), noted that which the trial described as the hierarchical “win ratio” composite outcomes, compared with patients randomized to placebo plus standard of care.

“The ‘win ratio’ tells us that there’s a 34% higher likelihood of patients having a better cardiometabolic outcome with dapagliflozin vs placebo in terms of the seven components,” James said in an interview. The win ratio was achieved in 32.9% of dapagliflozin patients versus 24.6% of placebo (P < .001).

Dr. James presented the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and they were published online simultaneously in NEJM Evidence.

Lower-risk patients

DAPA-MI enrolled 4,017 patients from the SWEDEHEART and Myocardial Ischemia National Audit Project registries in Sweden and the United Kingdom, randomly assigning patients to dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo along with guideline-directed therapy for both groups.

Eligible patients were hemodynamically stable, had an acute MI within 10 days of enrollment, and impaired left ventricular systolic function or a Q-wave MI. Exclusion criteria included history of either type 1 or 2 diabetes, chronic heart failure, poor kidney function, or current treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor. Baseline demographic characteristics were similar between trial arms.

- The hierarchical seven primary endpoints were:

- Death, with cardiovascular death ranked first followed by noncardiovascular death

- Hospitalization because of heart failure, with adjudicated first followed by investigator-reported HF

- Nonfatal MI

- Atrial fibrillation/flutter event

- New diagnosis of type 2 diabetes

- New York Heart Association functional class at the last visit

- Drop in body weight of at least 5% at the last visit

The key secondary endpoint, Dr. James said, was the primary outcome minus the body weight component, with time to first occurrence of hospitalization for HF or cardiovascular death.

When the seventh factor, body weight decrease, was removed, the differential narrowed: 20.3% versus 16.9% (P = .015). When two or more variables were removed from the composite, the differences were not statistically significant.

For 11 secondary and exploratory outcomes, ranging from CV death or hospitalization for HF to all-cause hospitalization, the outcomes were similar in both the dapagliflozin and placebo groups across the board.

However, the dapagliflozin patients had about half the rate of developing diabetes, compared with the placebo group: 2.1 % versus 3.9%.

The trial initially used the composite of CV death and hospitalization for HF as the primary endpoint, but switched to the seven-item composite endpoint in February because the number of primary composite outcomes was substantially lower than anticipated, Dr. James said.

He acknowledged the study was underpowered for the low-risk population it enrolled. “But if you extended the trial to a larger population and enriched it with a higher-risk population you would probably see an effect,” he said.

“The cardiometabolic benefit was consistent across all prespecified subgroups and there were no new safety concerns,” Dr. James told the attendees. “Clinical event rates were low with no significant difference between randomized groups.”

Not a ringing endorsement

But for invited discussant Stephen D. Wiviott, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, the DAPA-MI trial result isn’t quite a ringing endorsement of SGLT2 inhibition in these patients.

“From my perspective, DAPA-MI does not suggest a new mandate to expand SGLT2 inhibition to an isolated MI population without other SGLT2 inhibitor indications,” Dr. Wiviott told attendees. “But it does support the safety of its use among patients with acute coronary syndromes.”

However, “these results do not indicate a lack of clinical benefit in patients with prior MI and any of those previously identified conditions – a history of diabetes, coronary heart failure or chronic kidney disease – where SGLT2 inhibition remains a pillar of guideline-directed medical therapy,” Dr. Wiviott said.

In an interview, Dr. Wiviott described the trial design as a “hybrid” in that it used a registry but then added, in his words, “some of the bells and whistles that we have with normal cardiovascular clinical trials.” He further explained: “This is a nice combination of those two things, where they use that as part of the endpoint for the trial but they’re able to add in some of the pieces that you would in a regular registration pathway trial.”

The trial design could serve as a model for future pragmatic therapeutic trials in acute MI, he said, but he acknowledged that DAPA-MI was underpowered to discern many key outcomes.

“They anticipated they were going to have a rate of around 11% of events so they needed to enroll about 6,000 people, but somewhere in the middle of the trial they saw the rate was 2.5%, not 11%, so they had to completely change the trial,” he said of the DAPA-MI investigators.

But an appropriately powered study of SGLT2 inhibition in this population would need about 28,000 patients. “This would be an enormous trial to actually clinically power, so in my sense it’s not going to happen,” Dr. Wiviott said.

The DAPA-MI trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. James disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Amgen. Dr. Wiviott disclosed relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Icon Clinical, Novo Nordisk, and Varian.

PHILADELPHIA – Giving the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) to patients with acute myocardial infarction and impaired left ventricular systolic function but no diabetes or chronic heart failure significantly improved a composite of cardiovascular outcomes, a European registry-based randomized trial suggests.

In presenting these results from the DAPA-MI trial, Stefan James, MD, of Uppsala University (Sweden), noted that which the trial described as the hierarchical “win ratio” composite outcomes, compared with patients randomized to placebo plus standard of care.

“The ‘win ratio’ tells us that there’s a 34% higher likelihood of patients having a better cardiometabolic outcome with dapagliflozin vs placebo in terms of the seven components,” James said in an interview. The win ratio was achieved in 32.9% of dapagliflozin patients versus 24.6% of placebo (P < .001).

Dr. James presented the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and they were published online simultaneously in NEJM Evidence.

Lower-risk patients

DAPA-MI enrolled 4,017 patients from the SWEDEHEART and Myocardial Ischemia National Audit Project registries in Sweden and the United Kingdom, randomly assigning patients to dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo along with guideline-directed therapy for both groups.

Eligible patients were hemodynamically stable, had an acute MI within 10 days of enrollment, and impaired left ventricular systolic function or a Q-wave MI. Exclusion criteria included history of either type 1 or 2 diabetes, chronic heart failure, poor kidney function, or current treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor. Baseline demographic characteristics were similar between trial arms.

- The hierarchical seven primary endpoints were:

- Death, with cardiovascular death ranked first followed by noncardiovascular death

- Hospitalization because of heart failure, with adjudicated first followed by investigator-reported HF

- Nonfatal MI

- Atrial fibrillation/flutter event

- New diagnosis of type 2 diabetes

- New York Heart Association functional class at the last visit

- Drop in body weight of at least 5% at the last visit

The key secondary endpoint, Dr. James said, was the primary outcome minus the body weight component, with time to first occurrence of hospitalization for HF or cardiovascular death.

When the seventh factor, body weight decrease, was removed, the differential narrowed: 20.3% versus 16.9% (P = .015). When two or more variables were removed from the composite, the differences were not statistically significant.

For 11 secondary and exploratory outcomes, ranging from CV death or hospitalization for HF to all-cause hospitalization, the outcomes were similar in both the dapagliflozin and placebo groups across the board.

However, the dapagliflozin patients had about half the rate of developing diabetes, compared with the placebo group: 2.1 % versus 3.9%.

The trial initially used the composite of CV death and hospitalization for HF as the primary endpoint, but switched to the seven-item composite endpoint in February because the number of primary composite outcomes was substantially lower than anticipated, Dr. James said.

He acknowledged the study was underpowered for the low-risk population it enrolled. “But if you extended the trial to a larger population and enriched it with a higher-risk population you would probably see an effect,” he said.

“The cardiometabolic benefit was consistent across all prespecified subgroups and there were no new safety concerns,” Dr. James told the attendees. “Clinical event rates were low with no significant difference between randomized groups.”

Not a ringing endorsement

But for invited discussant Stephen D. Wiviott, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, the DAPA-MI trial result isn’t quite a ringing endorsement of SGLT2 inhibition in these patients.

“From my perspective, DAPA-MI does not suggest a new mandate to expand SGLT2 inhibition to an isolated MI population without other SGLT2 inhibitor indications,” Dr. Wiviott told attendees. “But it does support the safety of its use among patients with acute coronary syndromes.”

However, “these results do not indicate a lack of clinical benefit in patients with prior MI and any of those previously identified conditions – a history of diabetes, coronary heart failure or chronic kidney disease – where SGLT2 inhibition remains a pillar of guideline-directed medical therapy,” Dr. Wiviott said.

In an interview, Dr. Wiviott described the trial design as a “hybrid” in that it used a registry but then added, in his words, “some of the bells and whistles that we have with normal cardiovascular clinical trials.” He further explained: “This is a nice combination of those two things, where they use that as part of the endpoint for the trial but they’re able to add in some of the pieces that you would in a regular registration pathway trial.”

The trial design could serve as a model for future pragmatic therapeutic trials in acute MI, he said, but he acknowledged that DAPA-MI was underpowered to discern many key outcomes.

“They anticipated they were going to have a rate of around 11% of events so they needed to enroll about 6,000 people, but somewhere in the middle of the trial they saw the rate was 2.5%, not 11%, so they had to completely change the trial,” he said of the DAPA-MI investigators.

But an appropriately powered study of SGLT2 inhibition in this population would need about 28,000 patients. “This would be an enormous trial to actually clinically power, so in my sense it’s not going to happen,” Dr. Wiviott said.

The DAPA-MI trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. James disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Amgen. Dr. Wiviott disclosed relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Icon Clinical, Novo Nordisk, and Varian.

PHILADELPHIA – Giving the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) to patients with acute myocardial infarction and impaired left ventricular systolic function but no diabetes or chronic heart failure significantly improved a composite of cardiovascular outcomes, a European registry-based randomized trial suggests.

In presenting these results from the DAPA-MI trial, Stefan James, MD, of Uppsala University (Sweden), noted that which the trial described as the hierarchical “win ratio” composite outcomes, compared with patients randomized to placebo plus standard of care.

“The ‘win ratio’ tells us that there’s a 34% higher likelihood of patients having a better cardiometabolic outcome with dapagliflozin vs placebo in terms of the seven components,” James said in an interview. The win ratio was achieved in 32.9% of dapagliflozin patients versus 24.6% of placebo (P < .001).

Dr. James presented the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and they were published online simultaneously in NEJM Evidence.

Lower-risk patients

DAPA-MI enrolled 4,017 patients from the SWEDEHEART and Myocardial Ischemia National Audit Project registries in Sweden and the United Kingdom, randomly assigning patients to dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo along with guideline-directed therapy for both groups.

Eligible patients were hemodynamically stable, had an acute MI within 10 days of enrollment, and impaired left ventricular systolic function or a Q-wave MI. Exclusion criteria included history of either type 1 or 2 diabetes, chronic heart failure, poor kidney function, or current treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor. Baseline demographic characteristics were similar between trial arms.

- The hierarchical seven primary endpoints were:

- Death, with cardiovascular death ranked first followed by noncardiovascular death

- Hospitalization because of heart failure, with adjudicated first followed by investigator-reported HF

- Nonfatal MI

- Atrial fibrillation/flutter event

- New diagnosis of type 2 diabetes

- New York Heart Association functional class at the last visit

- Drop in body weight of at least 5% at the last visit

The key secondary endpoint, Dr. James said, was the primary outcome minus the body weight component, with time to first occurrence of hospitalization for HF or cardiovascular death.

When the seventh factor, body weight decrease, was removed, the differential narrowed: 20.3% versus 16.9% (P = .015). When two or more variables were removed from the composite, the differences were not statistically significant.

For 11 secondary and exploratory outcomes, ranging from CV death or hospitalization for HF to all-cause hospitalization, the outcomes were similar in both the dapagliflozin and placebo groups across the board.

However, the dapagliflozin patients had about half the rate of developing diabetes, compared with the placebo group: 2.1 % versus 3.9%.

The trial initially used the composite of CV death and hospitalization for HF as the primary endpoint, but switched to the seven-item composite endpoint in February because the number of primary composite outcomes was substantially lower than anticipated, Dr. James said.

He acknowledged the study was underpowered for the low-risk population it enrolled. “But if you extended the trial to a larger population and enriched it with a higher-risk population you would probably see an effect,” he said.

“The cardiometabolic benefit was consistent across all prespecified subgroups and there were no new safety concerns,” Dr. James told the attendees. “Clinical event rates were low with no significant difference between randomized groups.”

Not a ringing endorsement

But for invited discussant Stephen D. Wiviott, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, the DAPA-MI trial result isn’t quite a ringing endorsement of SGLT2 inhibition in these patients.

“From my perspective, DAPA-MI does not suggest a new mandate to expand SGLT2 inhibition to an isolated MI population without other SGLT2 inhibitor indications,” Dr. Wiviott told attendees. “But it does support the safety of its use among patients with acute coronary syndromes.”

However, “these results do not indicate a lack of clinical benefit in patients with prior MI and any of those previously identified conditions – a history of diabetes, coronary heart failure or chronic kidney disease – where SGLT2 inhibition remains a pillar of guideline-directed medical therapy,” Dr. Wiviott said.

In an interview, Dr. Wiviott described the trial design as a “hybrid” in that it used a registry but then added, in his words, “some of the bells and whistles that we have with normal cardiovascular clinical trials.” He further explained: “This is a nice combination of those two things, where they use that as part of the endpoint for the trial but they’re able to add in some of the pieces that you would in a regular registration pathway trial.”

The trial design could serve as a model for future pragmatic therapeutic trials in acute MI, he said, but he acknowledged that DAPA-MI was underpowered to discern many key outcomes.

“They anticipated they were going to have a rate of around 11% of events so they needed to enroll about 6,000 people, but somewhere in the middle of the trial they saw the rate was 2.5%, not 11%, so they had to completely change the trial,” he said of the DAPA-MI investigators.

But an appropriately powered study of SGLT2 inhibition in this population would need about 28,000 patients. “This would be an enormous trial to actually clinically power, so in my sense it’s not going to happen,” Dr. Wiviott said.

The DAPA-MI trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. James disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Amgen. Dr. Wiviott disclosed relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Icon Clinical, Novo Nordisk, and Varian.

AT AHA 2023

Semaglutide ‘a new pathway’ to CVD risk reduction: SELECT

over the approximately 3-year follow-up in patients with overweight or obesity and cardiovascular disease but not diabetes.

“This is a very exciting set of results. I think it is going to have a big impact on a large number of people,” lead investigator A. Michael Lincoff, MD, vice chair for research in the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

“And from a scientific standpoint, these data show that we now have a new pathway or a new modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease that we can use in our patients who have overweight or obesity,” he added.

The trial involved 17,604 patients with a history of cardiovascular disease and a body mass index of 27 kg/m2 or above (mean BMI was 33), who were randomly assigned to the glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonist semaglutide, given by subcutaneous injection once weekly at a gradually escalating dose up to 2.4 mg daily by week 16, or placebo. The mean baseline glycated hemoglobin level was 5.8% and 66.4% of patients met the criteria for prediabetes.

Patients lost a mean of 9.4% of body weight over the first 2 years with semaglutide versus 0.88% with placebo.

The primary cardiovascular endpoint – a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke – was reduced significantly, with a hazard ratio of 0.80 (95% confidence interval, 0.72-0.90; P < .001).

Death from cardiovascular causes, the first confirmatory secondary endpoint, showed a 15% reduction (HR, 0.85; P = .07) but this missed meeting criteria for statistical significance, and because of the hierarchical design of the trial, this meant that superiority testing was not performed for the remaining confirmatory secondary endpoints.

However, results showed reductions of around 20% for the heart failure composite endpoint and for all-cause mortality, with confidence intervals that did not cross 1.0, and directionally consistent effects were observed for all supportive secondary endpoints.

The HR for the heart failure composite endpoint was 0.82 (95% CI, 0.71-0.96), and the HR for death from any cause was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.71-0.93). Nonfatal MI was reduced by 28% (HR 0.72; 95% CI, 0.61-0.85).

The effects of semaglutide on the primary endpoint appeared to be similar across all prespecified subgroups.

Adverse events leading to discontinuation of treatment occurred in 16.6% in the semaglutide group, mostly gastrointestinal effects, and in 8.2% in the placebo group.

The trial results were presented by Dr. Lincoff at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association . They were also simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Lincoff explained that there is a growing pandemic of overweight and obesity worldwide with clear evidence for years that these conditions increase the risk of cardiovascular events – and yet there has been no evidence, until now, that any pharmacologic or lifestyle therapy can reduce the increased risk conferred by overweight/obesity.

“Patients in the trial were already taking standard of care therapies for other risk factors, such as hypertension and cholesterol, so this drug is giving additional benefit,” he said.

Dr. Lincoff believes these data will lead to a large increase in use of semaglutide, which is already available for the treatment of obesity and diabetes but can be difficult to get reimbursed.

“There is a lot of difficulty getting payors to pay for this drug for weight management. But with this new data from the SELECT trial there should be more willingness – at least in the population with a history of cardiovascular disease,” he commented. In diabetes, where it is already established that there is a cardiovascular risk reduction, it is easier to get these drugs reimbursed, he noted.

On the outcome data, Dr. Lincoff said he could not explain why cardiovascular death was not significantly reduced while all-cause mortality appeared to be cut more definitively.

“The cardiovascular death curves separated, then merged, then separated again. We don’t really know what is going on there. It may be that some deaths were misclassified. This trial was conducted through the COVID era and there may have been less information available on some patients because of that.”

But he added: “The all-cause mortality is more reassuring, as it doesn’t depend on classifying cause of death. Because of the design of the trial, we can’t formally claim a reduction in all-cause mortality, but the results do suggest there is an effect on this endpoint. And all the different types of cardiovascular events were similarly reduced in a consistent way, with similar effects seen across all subgroups. That is very reassuring.”

‘A new era’ for patients with obesity

Outside experts in the field were also impressed with the data.

Designated discussant of the trial at the AHA meeting, Ania Jastreboff, MD, associate professor medicine (endocrinology) at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said the SELECT trial was “a turning point in the treatment of obesity and a call to action.

“Now is the time to treat obesity to improve health outcomes in people with cardiovascular disease,” she said.

Dr. Jastreboff noted that high BMI was estimated to have accounted for 4 million deaths worldwide in 2015, two-thirds of which were caused by cardiovascular disease. And she presented data showing that U.S. individuals meeting the SELECT criteria increased from 4.3 million in 2011-12 to 6.6 million in 2017-18.

She highlighted one major limitation of the SELECT trial: it enrolled a low number of women (38%) and ethnic minorities, with only 12% of the trial population being Black.

Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, director of Mount Sinai Fuster Heart Hospital, New York, described the SELECT results as “altogether a compelling package of data.”

“These results are even better than I had expected,” Dr. Bhatt said in an interview. “There is a significant reduction in MI as I had anticipated, but additionally, there is a reduction in all-cause death. One can debate the statistics, though on a common-sense level, I think it is a real finding,” he noted.

“Given that MI, heart failure, nephropathy, and revascularization are all reduced, and even stroke is numerically lower, it makes sense that all-cause mortality would be reduced,” he said. “To me, apart from the GI side effects, this counts as a home run.”

Steve Nissen, MD, chief academic officer at the Cleveland Clinic’s Heart, Vascular and Thoracic Institute, was similarly upbeat.

“These data prove what many of us have long suspected – that losing weight can reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. This is great news for patients living with obesity. The obesity epidemic is out of control,” he added. “We need to have therapies that improve cardiovascular outcomes caused by obesity and this shows that semaglutide can do that. I think this is the beginning of a whole new era for patients with obesity.”

Michelle O’Donoghue, MD, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, called the results of SELECT “both intriguing and compelling. Certainly, these findings lend further support to the use of semaglutide in a much broader secondary prevention population of individuals with obesity.”

Christie Ballantyne, MD, director of the center for cardiometabolic disease prevention at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, described the SELECT study as “a landmark trial which will change the practice of medicine in regard to how we treat obesity.”

He compared it with the landmark 4S trial in 1994, the first study in the area of cholesterol lowering therapy to show a clear benefit in reducing cardiovascular events and total mortality, and “began a drastic change in the way that physicians approached treatment of cholesterol.”

On the more robust reduction in all-cause death, compared with cardiovascular death,

Dr. Ballantyne pointed out: “Adjudication of dead or alive is something that everyone gets right. In contrast, the cause of death is sometime difficult to ascertain. Most importantly, the benefit on total mortality also provides assurance that this therapy does not have some adverse effect on increasing noncardiovascular deaths.”

Gastrointestinal adverse effects

On the side effects seen with semaglutide, Dr. Lincoff reported that 10% of patients in the semaglutide group discontinued treatment because of GI side effects versus 2% in the placebo arm. He said this was “an expected issue.”

“GI effects, such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, are known side effects of this whole class of drugs. The dose is slowly escalated to manage these adverse effects but there will be a proportion of patients who can’t tolerate it, although the vast majority are able to continue.”

He noted that, while dose reduction was allowed, of the patients who were still on the drug at 2 years, 77% were on the full dose, and 23% were on a reduced dose.

Dr. Lincoff pointed out that there were no serious adverse events with semaglutide. “This is the largest database by far now on the drug with a long-term follow up and we didn’t see the emergence of any new safety signals, which is very reassuring.”

Dr. Nissen said the 16% rate of patients stopping the drug because of tolerability “is not a trivial number.”

He noted that the semaglutide dose used in this study was larger than that used in diabetes.

“They did this to try to achieve more weight loss but then you get more issues with tolerability. It’s a trade-off. If patients are experiencing adverse effects, the dose can be reduced, but then you will lose some effect. All the GLP-1 agonists have GI side effects – it’s part of the way that they work.”

Just weight loss or other actions too?

Speculating on the mechanism behind the reduction in cardiovascular events with semaglutide, Dr. Lincoff does not think it is just weight reduction.

“The event curves start to diverge very soon after the start of the trial and yet the maximum weight loss doesn’t occur until about 65 weeks. I think something else is going on.”

In the paper, the researchers noted that GLP-1 agonists have been shown in animal studies to reduce inflammation, improve endothelial and left ventricular function, promote plaque stability, and decrease platelet aggregation. In this trial, semaglutide was associated with changes in multiple biomarkers of cardiovascular risk, including blood pressure, waist circumference, glycemic control, nephropathy, and levels of lipids and C-reactive protein.

Dr. Lincoff also pointed out that similar benefits were seen in patients with different levels of overweight, and in those who were prediabetic and those who weren’t, so benefit was not dependent on baseline BMI or glycated hemoglobin levels.

Dr. O’Donoghue agreed that other effects, as well as weight loss, could be involved. “The reduction in events with semaglutide appeared very early after initiation and far preceded the drug’s maximal effects on weight reduction. This might suggest that the drug offers other cardioprotective effects through pathways independent of weight loss. Certainly, semaglutide and the other GLP-1 agonists appear to attenuate inflammation, and the patterns of redistribution of adipose tissue may also be of interest.”

She also pointed out that the reduction in cardiovascular events appeared even earlier in this population of obese nondiabetic patients with cardiovascular disease than in prior studies of patients with diabetes. “It may suggest that there is particular benefit for this type of therapy in patients with an inflammatory milieu. I look forward to seeing further analyses to help tease apart the correlation between changes in inflammation, observed weight loss and cardiovascular benefit.”

Effect on clinical practice

With the majority of patients with cardiovascular disease being overweight, these results are obviously going to increase demand for semaglutide, but cost and availability are going to be an issue.

Dr. Bhatt noted that semaglutide is already very popular. “Weight loss drugs are somewhat different from other medications. I can spend 30 minutes trying to convince a patient to take a statin, but here people realize it’s going to cause weight loss and they come in asking for it even if they don’t strictly need it. I think it’s good to have cardiovascular outcome data because now at least for this population of patients, we have evidence to prescribe it.”

He agreed with Dr. Lincoff that these new data should encourage insurance companies to cover the drug, because in reducing cardiovascular events it should also improve downstream health care costs.

“It is providing clear cardiovascular and kidney benefit, so it is in the best interest to the health care system to fund this drug,” he said. “I hope insurers look at it rationally in this way, but they may also be frightened of the explosion of patients wanting this drug and now doctors wanting to prescribe it and how that would affect their shorter-term costs.”

Dr. Lincoff said it would not be easy to prioritize certain groups. “We couldn’t identify any subgroup who showed particularly more benefit than any others. But in the evolution of any therapy, there is a time period where it is in short supply and prohibitively expensive, then over time when there is some competition and pricing deals occur as more people are advocating for it, they become more available.”

‘A welcome treatment option’

In an editorial accompanying publication of the trial, Amit Khera, MD, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and Tiffany Powell-Wiley, MD, MPH, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, noted that baseline risk factors such as LDL cholesterol (78 mg/dL) and systolic blood pressure (131 mm Hg) were not ideal in the semaglutide group in this trial, and they suggest that the benefits of semaglutide may be attenuated when these measures are better controlled.

But given that more than 20 million people in the United States have coronary artery disease, with the majority having overweight or obesity and only approximately 30% having concomitant diabetes, they said that, even in the context of well-controlled risk factors and very low LDL cholesterol levels, the residual risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in these persons is unacceptably high. “Thus, the SELECT trial provides a welcome treatment option that can be extended to millions of additional patients.”

However, the editorialists cautioned that semaglutide at current pricing comes with a significant cost to both patients and society, which makes this treatment inaccessible for many.

They added that intensive lifestyle interventions and bariatric surgery remain effective but underutilized options for obesity, and that the prevention of obesity before it develops should be the primary goal.

The SELECT trial was supported by Novo Nordisk, and several coauthors are employees of the company. Dr. Lincoff is a consultant for Novo Nordisk. Dr. Bhatt and Dr. Nissen are involved in a cardiovascular outcomes trial with a new investigational weight loss drug from Lilly. Dr. Bhatt and Dr. Ballantyne are also investigators in a Novo Nordisk trial of a new anti-inflammatory drug.

over the approximately 3-year follow-up in patients with overweight or obesity and cardiovascular disease but not diabetes.

“This is a very exciting set of results. I think it is going to have a big impact on a large number of people,” lead investigator A. Michael Lincoff, MD, vice chair for research in the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

“And from a scientific standpoint, these data show that we now have a new pathway or a new modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease that we can use in our patients who have overweight or obesity,” he added.

The trial involved 17,604 patients with a history of cardiovascular disease and a body mass index of 27 kg/m2 or above (mean BMI was 33), who were randomly assigned to the glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonist semaglutide, given by subcutaneous injection once weekly at a gradually escalating dose up to 2.4 mg daily by week 16, or placebo. The mean baseline glycated hemoglobin level was 5.8% and 66.4% of patients met the criteria for prediabetes.

Patients lost a mean of 9.4% of body weight over the first 2 years with semaglutide versus 0.88% with placebo.

The primary cardiovascular endpoint – a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke – was reduced significantly, with a hazard ratio of 0.80 (95% confidence interval, 0.72-0.90; P < .001).

Death from cardiovascular causes, the first confirmatory secondary endpoint, showed a 15% reduction (HR, 0.85; P = .07) but this missed meeting criteria for statistical significance, and because of the hierarchical design of the trial, this meant that superiority testing was not performed for the remaining confirmatory secondary endpoints.

However, results showed reductions of around 20% for the heart failure composite endpoint and for all-cause mortality, with confidence intervals that did not cross 1.0, and directionally consistent effects were observed for all supportive secondary endpoints.

The HR for the heart failure composite endpoint was 0.82 (95% CI, 0.71-0.96), and the HR for death from any cause was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.71-0.93). Nonfatal MI was reduced by 28% (HR 0.72; 95% CI, 0.61-0.85).

The effects of semaglutide on the primary endpoint appeared to be similar across all prespecified subgroups.

Adverse events leading to discontinuation of treatment occurred in 16.6% in the semaglutide group, mostly gastrointestinal effects, and in 8.2% in the placebo group.

The trial results were presented by Dr. Lincoff at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association . They were also simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Lincoff explained that there is a growing pandemic of overweight and obesity worldwide with clear evidence for years that these conditions increase the risk of cardiovascular events – and yet there has been no evidence, until now, that any pharmacologic or lifestyle therapy can reduce the increased risk conferred by overweight/obesity.

“Patients in the trial were already taking standard of care therapies for other risk factors, such as hypertension and cholesterol, so this drug is giving additional benefit,” he said.

Dr. Lincoff believes these data will lead to a large increase in use of semaglutide, which is already available for the treatment of obesity and diabetes but can be difficult to get reimbursed.

“There is a lot of difficulty getting payors to pay for this drug for weight management. But with this new data from the SELECT trial there should be more willingness – at least in the population with a history of cardiovascular disease,” he commented. In diabetes, where it is already established that there is a cardiovascular risk reduction, it is easier to get these drugs reimbursed, he noted.

On the outcome data, Dr. Lincoff said he could not explain why cardiovascular death was not significantly reduced while all-cause mortality appeared to be cut more definitively.

“The cardiovascular death curves separated, then merged, then separated again. We don’t really know what is going on there. It may be that some deaths were misclassified. This trial was conducted through the COVID era and there may have been less information available on some patients because of that.”

But he added: “The all-cause mortality is more reassuring, as it doesn’t depend on classifying cause of death. Because of the design of the trial, we can’t formally claim a reduction in all-cause mortality, but the results do suggest there is an effect on this endpoint. And all the different types of cardiovascular events were similarly reduced in a consistent way, with similar effects seen across all subgroups. That is very reassuring.”

‘A new era’ for patients with obesity

Outside experts in the field were also impressed with the data.

Designated discussant of the trial at the AHA meeting, Ania Jastreboff, MD, associate professor medicine (endocrinology) at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said the SELECT trial was “a turning point in the treatment of obesity and a call to action.

“Now is the time to treat obesity to improve health outcomes in people with cardiovascular disease,” she said.

Dr. Jastreboff noted that high BMI was estimated to have accounted for 4 million deaths worldwide in 2015, two-thirds of which were caused by cardiovascular disease. And she presented data showing that U.S. individuals meeting the SELECT criteria increased from 4.3 million in 2011-12 to 6.6 million in 2017-18.

She highlighted one major limitation of the SELECT trial: it enrolled a low number of women (38%) and ethnic minorities, with only 12% of the trial population being Black.

Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, director of Mount Sinai Fuster Heart Hospital, New York, described the SELECT results as “altogether a compelling package of data.”

“These results are even better than I had expected,” Dr. Bhatt said in an interview. “There is a significant reduction in MI as I had anticipated, but additionally, there is a reduction in all-cause death. One can debate the statistics, though on a common-sense level, I think it is a real finding,” he noted.

“Given that MI, heart failure, nephropathy, and revascularization are all reduced, and even stroke is numerically lower, it makes sense that all-cause mortality would be reduced,” he said. “To me, apart from the GI side effects, this counts as a home run.”

Steve Nissen, MD, chief academic officer at the Cleveland Clinic’s Heart, Vascular and Thoracic Institute, was similarly upbeat.

“These data prove what many of us have long suspected – that losing weight can reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. This is great news for patients living with obesity. The obesity epidemic is out of control,” he added. “We need to have therapies that improve cardiovascular outcomes caused by obesity and this shows that semaglutide can do that. I think this is the beginning of a whole new era for patients with obesity.”

Michelle O’Donoghue, MD, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, called the results of SELECT “both intriguing and compelling. Certainly, these findings lend further support to the use of semaglutide in a much broader secondary prevention population of individuals with obesity.”

Christie Ballantyne, MD, director of the center for cardiometabolic disease prevention at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, described the SELECT study as “a landmark trial which will change the practice of medicine in regard to how we treat obesity.”

He compared it with the landmark 4S trial in 1994, the first study in the area of cholesterol lowering therapy to show a clear benefit in reducing cardiovascular events and total mortality, and “began a drastic change in the way that physicians approached treatment of cholesterol.”

On the more robust reduction in all-cause death, compared with cardiovascular death,

Dr. Ballantyne pointed out: “Adjudication of dead or alive is something that everyone gets right. In contrast, the cause of death is sometime difficult to ascertain. Most importantly, the benefit on total mortality also provides assurance that this therapy does not have some adverse effect on increasing noncardiovascular deaths.”

Gastrointestinal adverse effects

On the side effects seen with semaglutide, Dr. Lincoff reported that 10% of patients in the semaglutide group discontinued treatment because of GI side effects versus 2% in the placebo arm. He said this was “an expected issue.”

“GI effects, such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, are known side effects of this whole class of drugs. The dose is slowly escalated to manage these adverse effects but there will be a proportion of patients who can’t tolerate it, although the vast majority are able to continue.”

He noted that, while dose reduction was allowed, of the patients who were still on the drug at 2 years, 77% were on the full dose, and 23% were on a reduced dose.

Dr. Lincoff pointed out that there were no serious adverse events with semaglutide. “This is the largest database by far now on the drug with a long-term follow up and we didn’t see the emergence of any new safety signals, which is very reassuring.”

Dr. Nissen said the 16% rate of patients stopping the drug because of tolerability “is not a trivial number.”

He noted that the semaglutide dose used in this study was larger than that used in diabetes.

“They did this to try to achieve more weight loss but then you get more issues with tolerability. It’s a trade-off. If patients are experiencing adverse effects, the dose can be reduced, but then you will lose some effect. All the GLP-1 agonists have GI side effects – it’s part of the way that they work.”

Just weight loss or other actions too?

Speculating on the mechanism behind the reduction in cardiovascular events with semaglutide, Dr. Lincoff does not think it is just weight reduction.

“The event curves start to diverge very soon after the start of the trial and yet the maximum weight loss doesn’t occur until about 65 weeks. I think something else is going on.”

In the paper, the researchers noted that GLP-1 agonists have been shown in animal studies to reduce inflammation, improve endothelial and left ventricular function, promote plaque stability, and decrease platelet aggregation. In this trial, semaglutide was associated with changes in multiple biomarkers of cardiovascular risk, including blood pressure, waist circumference, glycemic control, nephropathy, and levels of lipids and C-reactive protein.

Dr. Lincoff also pointed out that similar benefits were seen in patients with different levels of overweight, and in those who were prediabetic and those who weren’t, so benefit was not dependent on baseline BMI or glycated hemoglobin levels.

Dr. O’Donoghue agreed that other effects, as well as weight loss, could be involved. “The reduction in events with semaglutide appeared very early after initiation and far preceded the drug’s maximal effects on weight reduction. This might suggest that the drug offers other cardioprotective effects through pathways independent of weight loss. Certainly, semaglutide and the other GLP-1 agonists appear to attenuate inflammation, and the patterns of redistribution of adipose tissue may also be of interest.”

She also pointed out that the reduction in cardiovascular events appeared even earlier in this population of obese nondiabetic patients with cardiovascular disease than in prior studies of patients with diabetes. “It may suggest that there is particular benefit for this type of therapy in patients with an inflammatory milieu. I look forward to seeing further analyses to help tease apart the correlation between changes in inflammation, observed weight loss and cardiovascular benefit.”

Effect on clinical practice

With the majority of patients with cardiovascular disease being overweight, these results are obviously going to increase demand for semaglutide, but cost and availability are going to be an issue.

Dr. Bhatt noted that semaglutide is already very popular. “Weight loss drugs are somewhat different from other medications. I can spend 30 minutes trying to convince a patient to take a statin, but here people realize it’s going to cause weight loss and they come in asking for it even if they don’t strictly need it. I think it’s good to have cardiovascular outcome data because now at least for this population of patients, we have evidence to prescribe it.”

He agreed with Dr. Lincoff that these new data should encourage insurance companies to cover the drug, because in reducing cardiovascular events it should also improve downstream health care costs.

“It is providing clear cardiovascular and kidney benefit, so it is in the best interest to the health care system to fund this drug,” he said. “I hope insurers look at it rationally in this way, but they may also be frightened of the explosion of patients wanting this drug and now doctors wanting to prescribe it and how that would affect their shorter-term costs.”

Dr. Lincoff said it would not be easy to prioritize certain groups. “We couldn’t identify any subgroup who showed particularly more benefit than any others. But in the evolution of any therapy, there is a time period where it is in short supply and prohibitively expensive, then over time when there is some competition and pricing deals occur as more people are advocating for it, they become more available.”

‘A welcome treatment option’

In an editorial accompanying publication of the trial, Amit Khera, MD, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and Tiffany Powell-Wiley, MD, MPH, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, noted that baseline risk factors such as LDL cholesterol (78 mg/dL) and systolic blood pressure (131 mm Hg) were not ideal in the semaglutide group in this trial, and they suggest that the benefits of semaglutide may be attenuated when these measures are better controlled.

But given that more than 20 million people in the United States have coronary artery disease, with the majority having overweight or obesity and only approximately 30% having concomitant diabetes, they said that, even in the context of well-controlled risk factors and very low LDL cholesterol levels, the residual risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in these persons is unacceptably high. “Thus, the SELECT trial provides a welcome treatment option that can be extended to millions of additional patients.”

However, the editorialists cautioned that semaglutide at current pricing comes with a significant cost to both patients and society, which makes this treatment inaccessible for many.

They added that intensive lifestyle interventions and bariatric surgery remain effective but underutilized options for obesity, and that the prevention of obesity before it develops should be the primary goal.

The SELECT trial was supported by Novo Nordisk, and several coauthors are employees of the company. Dr. Lincoff is a consultant for Novo Nordisk. Dr. Bhatt and Dr. Nissen are involved in a cardiovascular outcomes trial with a new investigational weight loss drug from Lilly. Dr. Bhatt and Dr. Ballantyne are also investigators in a Novo Nordisk trial of a new anti-inflammatory drug.

over the approximately 3-year follow-up in patients with overweight or obesity and cardiovascular disease but not diabetes.

“This is a very exciting set of results. I think it is going to have a big impact on a large number of people,” lead investigator A. Michael Lincoff, MD, vice chair for research in the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

“And from a scientific standpoint, these data show that we now have a new pathway or a new modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease that we can use in our patients who have overweight or obesity,” he added.

The trial involved 17,604 patients with a history of cardiovascular disease and a body mass index of 27 kg/m2 or above (mean BMI was 33), who were randomly assigned to the glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonist semaglutide, given by subcutaneous injection once weekly at a gradually escalating dose up to 2.4 mg daily by week 16, or placebo. The mean baseline glycated hemoglobin level was 5.8% and 66.4% of patients met the criteria for prediabetes.

Patients lost a mean of 9.4% of body weight over the first 2 years with semaglutide versus 0.88% with placebo.

The primary cardiovascular endpoint – a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke – was reduced significantly, with a hazard ratio of 0.80 (95% confidence interval, 0.72-0.90; P < .001).

Death from cardiovascular causes, the first confirmatory secondary endpoint, showed a 15% reduction (HR, 0.85; P = .07) but this missed meeting criteria for statistical significance, and because of the hierarchical design of the trial, this meant that superiority testing was not performed for the remaining confirmatory secondary endpoints.

However, results showed reductions of around 20% for the heart failure composite endpoint and for all-cause mortality, with confidence intervals that did not cross 1.0, and directionally consistent effects were observed for all supportive secondary endpoints.

The HR for the heart failure composite endpoint was 0.82 (95% CI, 0.71-0.96), and the HR for death from any cause was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.71-0.93). Nonfatal MI was reduced by 28% (HR 0.72; 95% CI, 0.61-0.85).

The effects of semaglutide on the primary endpoint appeared to be similar across all prespecified subgroups.

Adverse events leading to discontinuation of treatment occurred in 16.6% in the semaglutide group, mostly gastrointestinal effects, and in 8.2% in the placebo group.

The trial results were presented by Dr. Lincoff at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association . They were also simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Lincoff explained that there is a growing pandemic of overweight and obesity worldwide with clear evidence for years that these conditions increase the risk of cardiovascular events – and yet there has been no evidence, until now, that any pharmacologic or lifestyle therapy can reduce the increased risk conferred by overweight/obesity.

“Patients in the trial were already taking standard of care therapies for other risk factors, such as hypertension and cholesterol, so this drug is giving additional benefit,” he said.

Dr. Lincoff believes these data will lead to a large increase in use of semaglutide, which is already available for the treatment of obesity and diabetes but can be difficult to get reimbursed.

“There is a lot of difficulty getting payors to pay for this drug for weight management. But with this new data from the SELECT trial there should be more willingness – at least in the population with a history of cardiovascular disease,” he commented. In diabetes, where it is already established that there is a cardiovascular risk reduction, it is easier to get these drugs reimbursed, he noted.

On the outcome data, Dr. Lincoff said he could not explain why cardiovascular death was not significantly reduced while all-cause mortality appeared to be cut more definitively.

“The cardiovascular death curves separated, then merged, then separated again. We don’t really know what is going on there. It may be that some deaths were misclassified. This trial was conducted through the COVID era and there may have been less information available on some patients because of that.”

But he added: “The all-cause mortality is more reassuring, as it doesn’t depend on classifying cause of death. Because of the design of the trial, we can’t formally claim a reduction in all-cause mortality, but the results do suggest there is an effect on this endpoint. And all the different types of cardiovascular events were similarly reduced in a consistent way, with similar effects seen across all subgroups. That is very reassuring.”

‘A new era’ for patients with obesity

Outside experts in the field were also impressed with the data.

Designated discussant of the trial at the AHA meeting, Ania Jastreboff, MD, associate professor medicine (endocrinology) at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said the SELECT trial was “a turning point in the treatment of obesity and a call to action.

“Now is the time to treat obesity to improve health outcomes in people with cardiovascular disease,” she said.

Dr. Jastreboff noted that high BMI was estimated to have accounted for 4 million deaths worldwide in 2015, two-thirds of which were caused by cardiovascular disease. And she presented data showing that U.S. individuals meeting the SELECT criteria increased from 4.3 million in 2011-12 to 6.6 million in 2017-18.

She highlighted one major limitation of the SELECT trial: it enrolled a low number of women (38%) and ethnic minorities, with only 12% of the trial population being Black.

Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, director of Mount Sinai Fuster Heart Hospital, New York, described the SELECT results as “altogether a compelling package of data.”

“These results are even better than I had expected,” Dr. Bhatt said in an interview. “There is a significant reduction in MI as I had anticipated, but additionally, there is a reduction in all-cause death. One can debate the statistics, though on a common-sense level, I think it is a real finding,” he noted.

“Given that MI, heart failure, nephropathy, and revascularization are all reduced, and even stroke is numerically lower, it makes sense that all-cause mortality would be reduced,” he said. “To me, apart from the GI side effects, this counts as a home run.”

Steve Nissen, MD, chief academic officer at the Cleveland Clinic’s Heart, Vascular and Thoracic Institute, was similarly upbeat.

“These data prove what many of us have long suspected – that losing weight can reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. This is great news for patients living with obesity. The obesity epidemic is out of control,” he added. “We need to have therapies that improve cardiovascular outcomes caused by obesity and this shows that semaglutide can do that. I think this is the beginning of a whole new era for patients with obesity.”

Michelle O’Donoghue, MD, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, called the results of SELECT “both intriguing and compelling. Certainly, these findings lend further support to the use of semaglutide in a much broader secondary prevention population of individuals with obesity.”

Christie Ballantyne, MD, director of the center for cardiometabolic disease prevention at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, described the SELECT study as “a landmark trial which will change the practice of medicine in regard to how we treat obesity.”

He compared it with the landmark 4S trial in 1994, the first study in the area of cholesterol lowering therapy to show a clear benefit in reducing cardiovascular events and total mortality, and “began a drastic change in the way that physicians approached treatment of cholesterol.”

On the more robust reduction in all-cause death, compared with cardiovascular death,

Dr. Ballantyne pointed out: “Adjudication of dead or alive is something that everyone gets right. In contrast, the cause of death is sometime difficult to ascertain. Most importantly, the benefit on total mortality also provides assurance that this therapy does not have some adverse effect on increasing noncardiovascular deaths.”

Gastrointestinal adverse effects

On the side effects seen with semaglutide, Dr. Lincoff reported that 10% of patients in the semaglutide group discontinued treatment because of GI side effects versus 2% in the placebo arm. He said this was “an expected issue.”

“GI effects, such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, are known side effects of this whole class of drugs. The dose is slowly escalated to manage these adverse effects but there will be a proportion of patients who can’t tolerate it, although the vast majority are able to continue.”

He noted that, while dose reduction was allowed, of the patients who were still on the drug at 2 years, 77% were on the full dose, and 23% were on a reduced dose.

Dr. Lincoff pointed out that there were no serious adverse events with semaglutide. “This is the largest database by far now on the drug with a long-term follow up and we didn’t see the emergence of any new safety signals, which is very reassuring.”

Dr. Nissen said the 16% rate of patients stopping the drug because of tolerability “is not a trivial number.”

He noted that the semaglutide dose used in this study was larger than that used in diabetes.

“They did this to try to achieve more weight loss but then you get more issues with tolerability. It’s a trade-off. If patients are experiencing adverse effects, the dose can be reduced, but then you will lose some effect. All the GLP-1 agonists have GI side effects – it’s part of the way that they work.”

Just weight loss or other actions too?

Speculating on the mechanism behind the reduction in cardiovascular events with semaglutide, Dr. Lincoff does not think it is just weight reduction.

“The event curves start to diverge very soon after the start of the trial and yet the maximum weight loss doesn’t occur until about 65 weeks. I think something else is going on.”

In the paper, the researchers noted that GLP-1 agonists have been shown in animal studies to reduce inflammation, improve endothelial and left ventricular function, promote plaque stability, and decrease platelet aggregation. In this trial, semaglutide was associated with changes in multiple biomarkers of cardiovascular risk, including blood pressure, waist circumference, glycemic control, nephropathy, and levels of lipids and C-reactive protein.

Dr. Lincoff also pointed out that similar benefits were seen in patients with different levels of overweight, and in those who were prediabetic and those who weren’t, so benefit was not dependent on baseline BMI or glycated hemoglobin levels.

Dr. O’Donoghue agreed that other effects, as well as weight loss, could be involved. “The reduction in events with semaglutide appeared very early after initiation and far preceded the drug’s maximal effects on weight reduction. This might suggest that the drug offers other cardioprotective effects through pathways independent of weight loss. Certainly, semaglutide and the other GLP-1 agonists appear to attenuate inflammation, and the patterns of redistribution of adipose tissue may also be of interest.”

She also pointed out that the reduction in cardiovascular events appeared even earlier in this population of obese nondiabetic patients with cardiovascular disease than in prior studies of patients with diabetes. “It may suggest that there is particular benefit for this type of therapy in patients with an inflammatory milieu. I look forward to seeing further analyses to help tease apart the correlation between changes in inflammation, observed weight loss and cardiovascular benefit.”

Effect on clinical practice

With the majority of patients with cardiovascular disease being overweight, these results are obviously going to increase demand for semaglutide, but cost and availability are going to be an issue.

Dr. Bhatt noted that semaglutide is already very popular. “Weight loss drugs are somewhat different from other medications. I can spend 30 minutes trying to convince a patient to take a statin, but here people realize it’s going to cause weight loss and they come in asking for it even if they don’t strictly need it. I think it’s good to have cardiovascular outcome data because now at least for this population of patients, we have evidence to prescribe it.”

He agreed with Dr. Lincoff that these new data should encourage insurance companies to cover the drug, because in reducing cardiovascular events it should also improve downstream health care costs.

“It is providing clear cardiovascular and kidney benefit, so it is in the best interest to the health care system to fund this drug,” he said. “I hope insurers look at it rationally in this way, but they may also be frightened of the explosion of patients wanting this drug and now doctors wanting to prescribe it and how that would affect their shorter-term costs.”

Dr. Lincoff said it would not be easy to prioritize certain groups. “We couldn’t identify any subgroup who showed particularly more benefit than any others. But in the evolution of any therapy, there is a time period where it is in short supply and prohibitively expensive, then over time when there is some competition and pricing deals occur as more people are advocating for it, they become more available.”

‘A welcome treatment option’

In an editorial accompanying publication of the trial, Amit Khera, MD, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and Tiffany Powell-Wiley, MD, MPH, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, noted that baseline risk factors such as LDL cholesterol (78 mg/dL) and systolic blood pressure (131 mm Hg) were not ideal in the semaglutide group in this trial, and they suggest that the benefits of semaglutide may be attenuated when these measures are better controlled.

But given that more than 20 million people in the United States have coronary artery disease, with the majority having overweight or obesity and only approximately 30% having concomitant diabetes, they said that, even in the context of well-controlled risk factors and very low LDL cholesterol levels, the residual risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in these persons is unacceptably high. “Thus, the SELECT trial provides a welcome treatment option that can be extended to millions of additional patients.”

However, the editorialists cautioned that semaglutide at current pricing comes with a significant cost to both patients and society, which makes this treatment inaccessible for many.

They added that intensive lifestyle interventions and bariatric surgery remain effective but underutilized options for obesity, and that the prevention of obesity before it develops should be the primary goal.

The SELECT trial was supported by Novo Nordisk, and several coauthors are employees of the company. Dr. Lincoff is a consultant for Novo Nordisk. Dr. Bhatt and Dr. Nissen are involved in a cardiovascular outcomes trial with a new investigational weight loss drug from Lilly. Dr. Bhatt and Dr. Ballantyne are also investigators in a Novo Nordisk trial of a new anti-inflammatory drug.

FROM AHA 2023

Does vaginal estrogen use increase the risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes?

Evidence summary

Cohort studies demonstrate no adverse CV outcomes

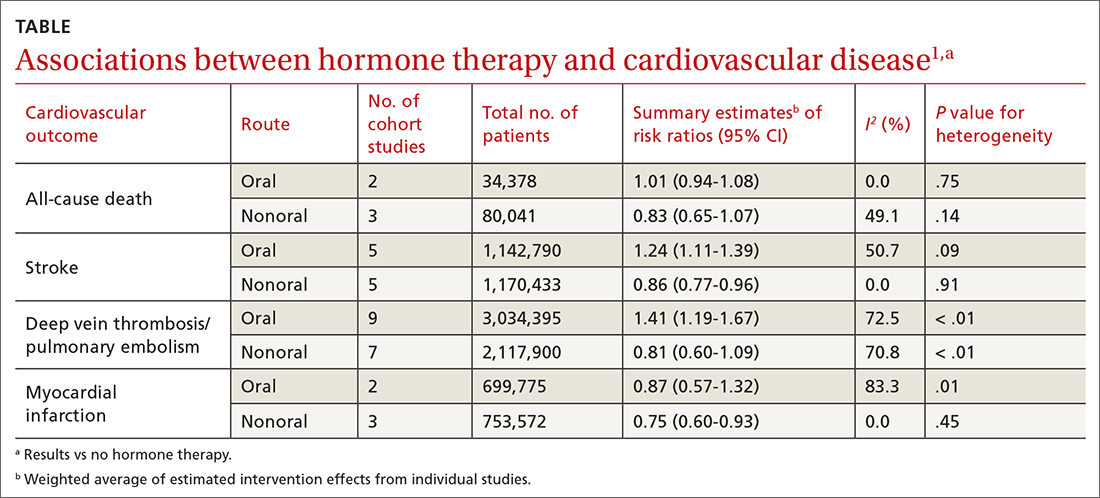

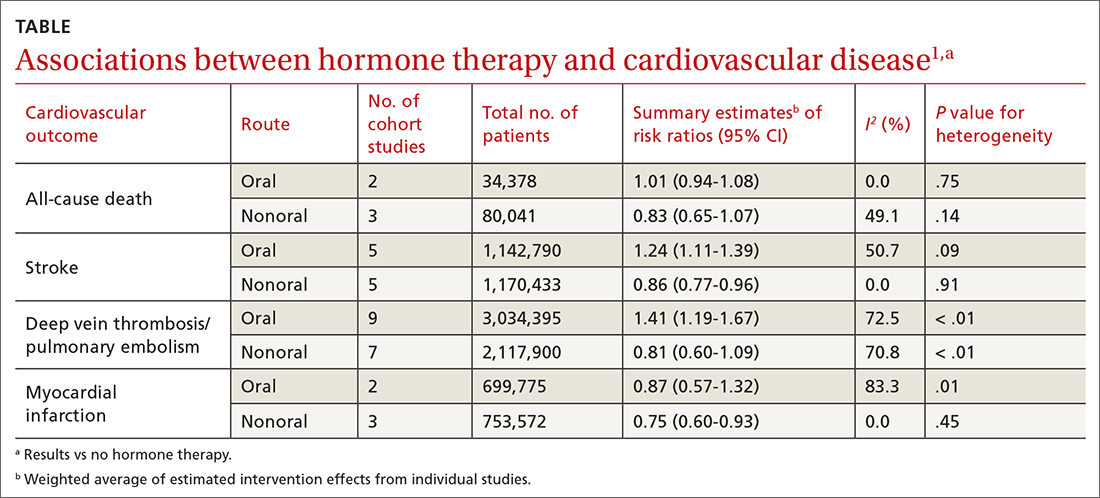

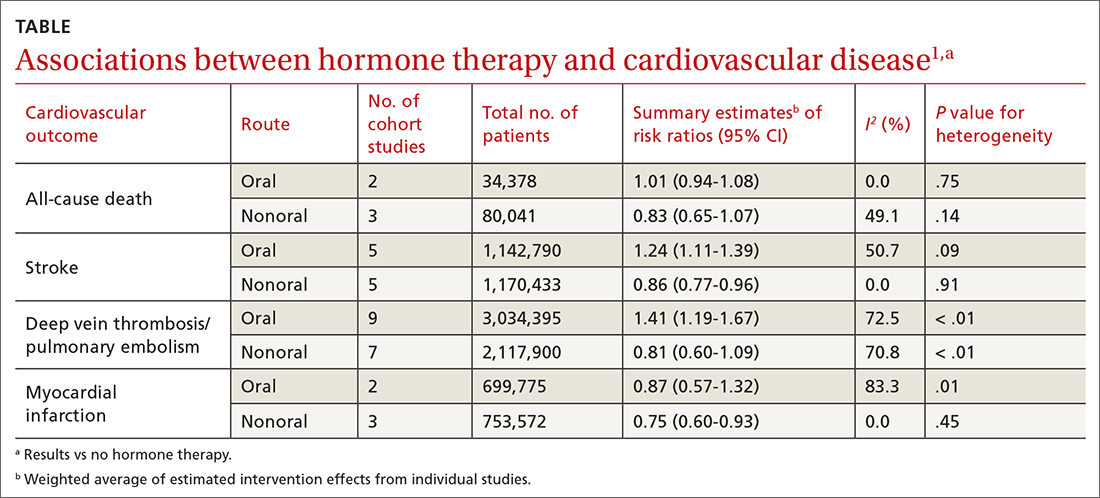

A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies to examine the association between menopausal hormone therapy and CV disease.1 The 26 RCTs primarily evaluated oral hormone administration. The observational studies comprised 30 cohort studies, 13 case-control studies, and 5 nested case-control studies, primarily in Europe and North America; 21 reported the route of administration. The trials evaluated women ages 49 to 77 years (mean, 61 years), and follow-up ranged from 1 to 21.5 years (mean, 7 years). In subgroup analyses of the observational studies, nonoral hormone therapy was associated with a lower risk for stroke and MI compared to oral administration (see TABLE1). Study limitations included enrollment of patients with few comorbidities, from limited geographic regions. Results in the meta-analysis were not stratified by the type of nonoral hormone therapy; only 4 studies evaluated vaginal estrogen use.

Two large cohort studies included in the systematic review provided more specific data on vaginal estrogens. The first used data from the Women’s Health Initiative in a subset of women ages 50 to 79 years (n = 46,566) who were not already on systemic hormone therapy and who did not have prior history of breast, endometrial, or ovarian cancer.2 Data were collected from self-assessment questionnaires and medical record reviews. The median duration of vaginal estrogen use was 2 years, and median follow-up duration was 7.2 years. Vaginal estrogen users had a 48% lower risk for CHD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 0.52; 95% CI, 0.31-0.85) than nonusers. Rates for all-cause mortality (aHR = 0.78; 95% CI, 0.58-1.04), stroke (aHR = 0.78; 95% CI, 0.49-1.24), and DVT/PE (aHR = 0.68; 95% CI, 0.36-1.28) were similar. In this and the other cohort studies to be discussed, outcome data for all vaginal estrogen preparations (eg, cream, ring, tablet) were combined.

The other large cohort study in the systematic review evaluated data on postmenopausal women from the Nurses’ Health Study.3 The authors evaluated health reports on 53,797 women as they transitioned through menopause. Patients with systemic hormone therapy use, history of cancer, and self-reported CV disease were excluded. After adjusting for covariates, the authors found no statistically significant difference between users and nonusers of vaginal estrogen and risk for total MI (aHR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.47-1.13), stroke (aHR = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.56-1.29), or DVT/PE (aHR = 1.06; 95% CI, 0.58-1.93). Study limitations included low prevalence of vaginal estrogen use (< 3%), short duration of use (mean, 37.5 months), and lack of data on the type or dose of vaginal estrogen used. The study only included health professionals, which limits generalizability.

A Finnish cohort study (excluded from the systematic review because it used historical controls) compared rates of CHD and stroke in postmenopausal women who used vaginal estrogen against an age-matched background population. Researchers collected data from a nationwide prescription registry for women at least 50 years old who had purchased vaginal estrogens between 1994 and 2009 (n = 195,756).4 Women who purchased systemic hormone therapy at any point were excluded. After 3 to 5 years of exposure, use of vaginal estrogen was associated with a decreased risk for mortality from CHD (relative risk [RR] = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.57-0.70) and stroke (RR = 0.79; 95% CI, 0.69-0.91). However, after 10 years, these benefits were not seen (CHD: RR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.90-1.00; stroke: RR = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.85-1.01). All confidence interval data were presented graphically. Key weaknesses of this study included use of both vaginal and systemic estrogen in the comparator background population, and the failure to collect data for other CV risk variables such as weight, tobacco exposure, and blood pressure.

Recommendations from others

In 2022, the North American Menopause Society issued a Hormone Therapy Position Statement that acknowledged the lack of clinical trials directly comparing risk for adverse CV endpoints with different estrogen administration routes.5 They stated nonoral routes of administration might offer advantages by bypassing first-pass hepatic metabolism.

Similarly, the 2015 Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline on the Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause also stated that the effects of low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy on CV disease or DVT/PE risk had not been adequately studied.6

A 2013 opinion by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists stated that topical estrogen vaginal creams, tablets, and rings had low levels of systemic absorption and were not associated with an increased risk for DVT/PE.7

Editor’s takeaway

The available evidence on vaginal estrogen replacement reassures us of its safety. After decades spent studying hormone replacement therapy with vacillating conclusions and opinions, these cohorts—the best evidence we may ever get—along with a consensus of expert opinions, consistently demonstrate no adverse CV outcomes.

1. Kim JE, Chang JH, Jeong MJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of effects of menopausal hormone therapy on cardiovascular diseases. Sci Rep. 2020;10:20631. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77534-9

2. Crandall CJ, Hovey KM, Andrews CA, et al. Breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and cardiovascular events in participants who used vaginal estrogen in the WHI Observational Study. Menopause. 2018;25:11-20. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000956

3. Bhupathiraju SN, Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, et al. Vaginal estrogen use and chronic disease risk in the Nurses’ Health Study. Menopause. 2018;26:603-610. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001284

4. Mikkola TS, Tuomikoski P, Lyytinen H, et al. Vaginal estrogen use and the risk for cardiovascular mortality. Human Reproduction. 2016;31:804-809. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew014

5. North American Menopause Society. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2022;29:767-794. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002028

6. Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Gompel A, et al. Treatment of symptoms of the menopause: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:3975-4011. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2236

7. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No 565: hormone therapy and heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:1407-1410. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000431053.33593.2d

Evidence summary

Cohort studies demonstrate no adverse CV outcomes

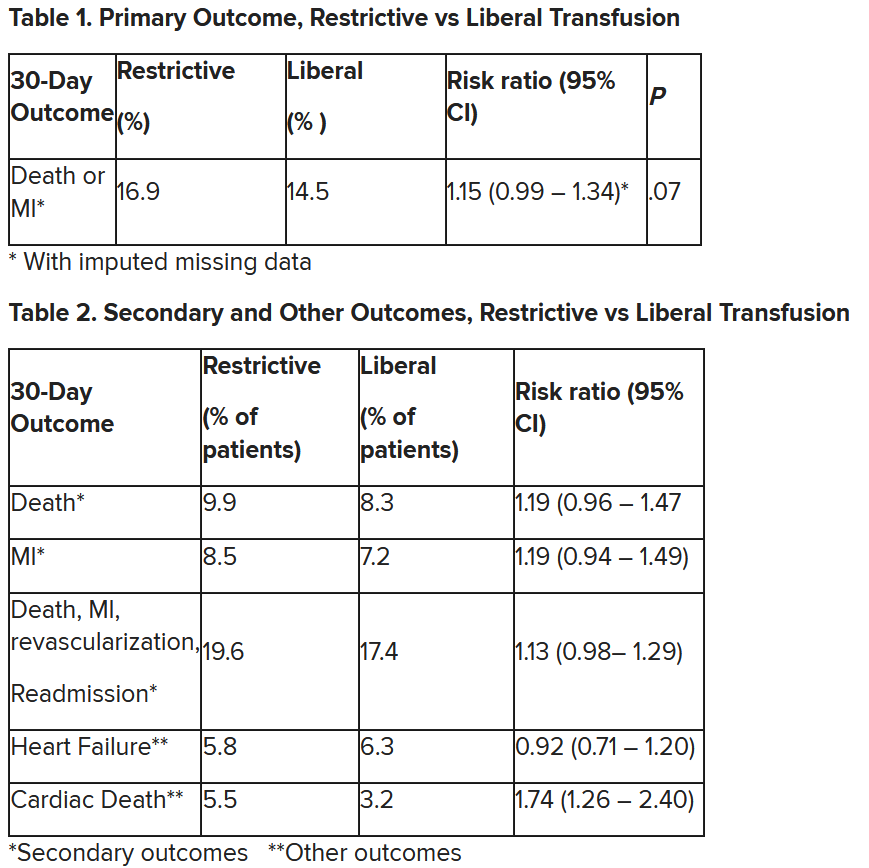

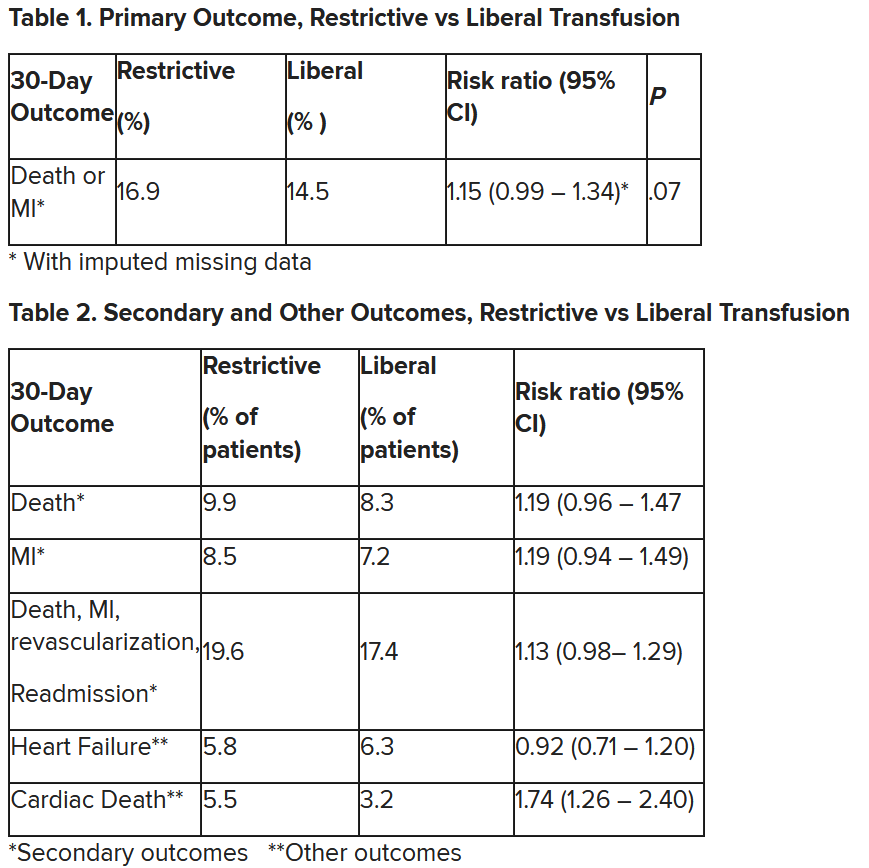

A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies to examine the association between menopausal hormone therapy and CV disease.1 The 26 RCTs primarily evaluated oral hormone administration. The observational studies comprised 30 cohort studies, 13 case-control studies, and 5 nested case-control studies, primarily in Europe and North America; 21 reported the route of administration. The trials evaluated women ages 49 to 77 years (mean, 61 years), and follow-up ranged from 1 to 21.5 years (mean, 7 years). In subgroup analyses of the observational studies, nonoral hormone therapy was associated with a lower risk for stroke and MI compared to oral administration (see TABLE1). Study limitations included enrollment of patients with few comorbidities, from limited geographic regions. Results in the meta-analysis were not stratified by the type of nonoral hormone therapy; only 4 studies evaluated vaginal estrogen use.

Two large cohort studies included in the systematic review provided more specific data on vaginal estrogens. The first used data from the Women’s Health Initiative in a subset of women ages 50 to 79 years (n = 46,566) who were not already on systemic hormone therapy and who did not have prior history of breast, endometrial, or ovarian cancer.2 Data were collected from self-assessment questionnaires and medical record reviews. The median duration of vaginal estrogen use was 2 years, and median follow-up duration was 7.2 years. Vaginal estrogen users had a 48% lower risk for CHD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 0.52; 95% CI, 0.31-0.85) than nonusers. Rates for all-cause mortality (aHR = 0.78; 95% CI, 0.58-1.04), stroke (aHR = 0.78; 95% CI, 0.49-1.24), and DVT/PE (aHR = 0.68; 95% CI, 0.36-1.28) were similar. In this and the other cohort studies to be discussed, outcome data for all vaginal estrogen preparations (eg, cream, ring, tablet) were combined.

The other large cohort study in the systematic review evaluated data on postmenopausal women from the Nurses’ Health Study.3 The authors evaluated health reports on 53,797 women as they transitioned through menopause. Patients with systemic hormone therapy use, history of cancer, and self-reported CV disease were excluded. After adjusting for covariates, the authors found no statistically significant difference between users and nonusers of vaginal estrogen and risk for total MI (aHR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.47-1.13), stroke (aHR = 0.85; 95% CI, 0.56-1.29), or DVT/PE (aHR = 1.06; 95% CI, 0.58-1.93). Study limitations included low prevalence of vaginal estrogen use (< 3%), short duration of use (mean, 37.5 months), and lack of data on the type or dose of vaginal estrogen used. The study only included health professionals, which limits generalizability.

A Finnish cohort study (excluded from the systematic review because it used historical controls) compared rates of CHD and stroke in postmenopausal women who used vaginal estrogen against an age-matched background population. Researchers collected data from a nationwide prescription registry for women at least 50 years old who had purchased vaginal estrogens between 1994 and 2009 (n = 195,756).4 Women who purchased systemic hormone therapy at any point were excluded. After 3 to 5 years of exposure, use of vaginal estrogen was associated with a decreased risk for mortality from CHD (relative risk [RR] = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.57-0.70) and stroke (RR = 0.79; 95% CI, 0.69-0.91). However, after 10 years, these benefits were not seen (CHD: RR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.90-1.00; stroke: RR = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.85-1.01). All confidence interval data were presented graphically. Key weaknesses of this study included use of both vaginal and systemic estrogen in the comparator background population, and the failure to collect data for other CV risk variables such as weight, tobacco exposure, and blood pressure.

Recommendations from others

In 2022, the North American Menopause Society issued a Hormone Therapy Position Statement that acknowledged the lack of clinical trials directly comparing risk for adverse CV endpoints with different estrogen administration routes.5 They stated nonoral routes of administration might offer advantages by bypassing first-pass hepatic metabolism.

Similarly, the 2015 Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline on the Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause also stated that the effects of low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy on CV disease or DVT/PE risk had not been adequately studied.6

A 2013 opinion by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists stated that topical estrogen vaginal creams, tablets, and rings had low levels of systemic absorption and were not associated with an increased risk for DVT/PE.7

Editor’s takeaway

The available evidence on vaginal estrogen replacement reassures us of its safety. After decades spent studying hormone replacement therapy with vacillating conclusions and opinions, these cohorts—the best evidence we may ever get—along with a consensus of expert opinions, consistently demonstrate no adverse CV outcomes.

Evidence summary

Cohort studies demonstrate no adverse CV outcomes

A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies to examine the association between menopausal hormone therapy and CV disease.1 The 26 RCTs primarily evaluated oral hormone administration. The observational studies comprised 30 cohort studies, 13 case-control studies, and 5 nested case-control studies, primarily in Europe and North America; 21 reported the route of administration. The trials evaluated women ages 49 to 77 years (mean, 61 years), and follow-up ranged from 1 to 21.5 years (mean, 7 years). In subgroup analyses of the observational studies, nonoral hormone therapy was associated with a lower risk for stroke and MI compared to oral administration (see TABLE1). Study limitations included enrollment of patients with few comorbidities, from limited geographic regions. Results in the meta-analysis were not stratified by the type of nonoral hormone therapy; only 4 studies evaluated vaginal estrogen use.

Two large cohort studies included in the systematic review provided more specific data on vaginal estrogens. The first used data from the Women’s Health Initiative in a subset of women ages 50 to 79 years (n = 46,566) who were not already on systemic hormone therapy and who did not have prior history of breast, endometrial, or ovarian cancer.2 Data were collected from self-assessment questionnaires and medical record reviews. The median duration of vaginal estrogen use was 2 years, and median follow-up duration was 7.2 years. Vaginal estrogen users had a 48% lower risk for CHD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 0.52; 95% CI, 0.31-0.85) than nonusers. Rates for all-cause mortality (aHR = 0.78; 95% CI, 0.58-1.04), stroke (aHR = 0.78; 95% CI, 0.49-1.24), and DVT/PE (aHR = 0.68; 95% CI, 0.36-1.28) were similar. In this and the other cohort studies to be discussed, outcome data for all vaginal estrogen preparations (eg, cream, ring, tablet) were combined.