User login

Colistin Resistance Reinforces Antibiotic Stewardship Efforts

In 2015, researchers in China announced they had found for the first time a bacterial gene conferring resistance to colistin. The gene was present in samples from agricultural animals and in 1% of tested patients.1 Colistin, an antibiotic from the 1950s, is rarely prescribed; it is often considered an antibiotic of last resort.

In May 2016, the U.S. Department of Defense announced this gene, called mcr-1, had been found in E. coli isolated from the urine of a patient in Pennsylvania presenting with symptoms of a urinary tract infection.2 Subsequent surveillance also found mcr-1 E. coli in a pig.

The news has been met with grave concern by public health officials, scientists, infectious disease specialists, and countless physicians around the U.S. It has also served as a reminder that good antibiotic stewardship is a national, if not international, imperative.

“The recent discovery of a plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene, mcr-1, heralds the emergence of truly pan-drug resistant bacteria,” the authors of the recent U.S. study, from the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, wrote in their opening sentence.

In November 2015, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) launched an antibiotic stewardship campaign, “Fight the Resistance,” in partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hospitalists around the country have taken the lead on confronting the issue head on.

When the CDC and the White House called for action last year, “SHM jumped in with both feet,” says Eric Howell, MD, MHM, SHM’s senior physician advisor, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview, and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. The “Fight the Resistance” campaign calls for the nation’s 44,000 hospitalists to commit to responsible antibiotic-prescribing practices.

“While it’s extremely alarming, leading up to this, we knew there was a crisis of antibiotic resistance,” says Megan Mack, MD, a hospitalist and clinical instructor in the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “We know more antibiotic use is not the answer, stronger is not the answer. We need to be peeling back antibiotic use, honing when we need them, narrowing how we use them as much as possible, and keeping the duration as short as possible.”

Dr. Mack is first author of a new study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine that examines hospitalist-driven antibiotic stewardship efforts in five hospitals around the country.3

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement, with the CDC, recruited Dr. Mack and her study coauthors, hospitalists Jeff Rohde, MD, and Scott Flanders, MD, MHM, to participate.

“We were interested in the opportunity to put into place interventions in five different hospitals and to be able to share our successes and our barriers, which we did twice monthly,” Dr. Mack says.

Each hospital in the collaborative, which included teaching and non-teaching community hospitals and academic medical centers, focused on its own data and tailored its stewardship interventions to three strategies shown to be quality indicators of successful stewardship programs.

These strategies included:

- Enhanced documentation with regard to antimicrobial prescribing and use

- Improved quality and accessibility of guidelines for common infections

- Adoption of a 72-hour antibiotic timeout to reassess a patient’s antibiotic treatment plan once culture results were available

Each hospital used its own particular antibiotic stewardship practice data to educate and inform its physicians, which Dr. Mack says was important to the success of interventions because it was “concrete and realistic.”

The study found that in two hospitals, complete antibiotic documentation in patient records increased to 51% from 4% and to 65% from 8%. It also recorded 726 antibiotic timeouts, resulting in 218 antibiotic treatment adjustments or discontinuations. It also found several barriers to improved antibiotic stewardship.

“[Hospitalists] are stretched for time. We’re constantly being pulled in multiple directions,” Dr. Mack says. “We are bombarded daily with quality improvement initiatives and with constantly meeting metrics deemed to be priorities, so we tried interventions that were easily incorporated into daily workflow.”

The team learned that workflow integration was a requirement for success. For instance, Dr. Mack suggests building antibiotic prescribing into hospitalists’ electronic health records, with automatic stop dates that must be overridden by a physician. “It’s too easy to overlook it, and 10 days later, your patient is still on vancomycin.”

The experience, she says, made her fellow physicians in the collaborative realize that, despite some skepticism, good antimicrobial stewardship can be achieved without significant disruption.

“If we don’t change our practice patterns, there are not enough antibiotics in the pipeline to mitigate the effects,” of resistance, says Dr. Howell, who was not involved in the study. “We can’t stop resistance, but we can change our practice patterns so we slow the rate of resistance and give ourselves time to develop new therapies to treat infections.”

This includes behavioral changes hospitalists can easily incorporate, Dr. Howell says, which align with the strategies assessed in Dr. Mack’s study. These include rethinking the treatment time course, antibiotic timeouts, and adhering to prescribing guidelines.

Hospitalists, he says, are well-positioned to lead antibiotic stewardship efforts.

“We’re quality improvement experts … and there are not enough infectious disease physicians in the country to roll out antibiotic stewardship programs, so there is space for hospitalists,” Dr. Howell explains. “In every hospital, we are prescribing these medications, so we own the problem.” TH

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

References

- Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(2):161-168. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7.

- McGann P, Snesrud E, Maybank R, et al. Escherichia coli harboring mcr-1 and blaCTX-M on a novel IncF plasmid: First report of mcr-1 in the USA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(7):4420-4421.

- Mack MR, Rohde JM, Jacobsen D, et al. Engaging hospitalists in antimicrobial stewardship: Lessons from a multihospital collaborative [published online ahead of print on April 30, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2599.

In 2015, researchers in China announced they had found for the first time a bacterial gene conferring resistance to colistin. The gene was present in samples from agricultural animals and in 1% of tested patients.1 Colistin, an antibiotic from the 1950s, is rarely prescribed; it is often considered an antibiotic of last resort.

In May 2016, the U.S. Department of Defense announced this gene, called mcr-1, had been found in E. coli isolated from the urine of a patient in Pennsylvania presenting with symptoms of a urinary tract infection.2 Subsequent surveillance also found mcr-1 E. coli in a pig.

The news has been met with grave concern by public health officials, scientists, infectious disease specialists, and countless physicians around the U.S. It has also served as a reminder that good antibiotic stewardship is a national, if not international, imperative.

“The recent discovery of a plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene, mcr-1, heralds the emergence of truly pan-drug resistant bacteria,” the authors of the recent U.S. study, from the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, wrote in their opening sentence.

In November 2015, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) launched an antibiotic stewardship campaign, “Fight the Resistance,” in partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hospitalists around the country have taken the lead on confronting the issue head on.

When the CDC and the White House called for action last year, “SHM jumped in with both feet,” says Eric Howell, MD, MHM, SHM’s senior physician advisor, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview, and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. The “Fight the Resistance” campaign calls for the nation’s 44,000 hospitalists to commit to responsible antibiotic-prescribing practices.

“While it’s extremely alarming, leading up to this, we knew there was a crisis of antibiotic resistance,” says Megan Mack, MD, a hospitalist and clinical instructor in the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “We know more antibiotic use is not the answer, stronger is not the answer. We need to be peeling back antibiotic use, honing when we need them, narrowing how we use them as much as possible, and keeping the duration as short as possible.”

Dr. Mack is first author of a new study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine that examines hospitalist-driven antibiotic stewardship efforts in five hospitals around the country.3

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement, with the CDC, recruited Dr. Mack and her study coauthors, hospitalists Jeff Rohde, MD, and Scott Flanders, MD, MHM, to participate.

“We were interested in the opportunity to put into place interventions in five different hospitals and to be able to share our successes and our barriers, which we did twice monthly,” Dr. Mack says.

Each hospital in the collaborative, which included teaching and non-teaching community hospitals and academic medical centers, focused on its own data and tailored its stewardship interventions to three strategies shown to be quality indicators of successful stewardship programs.

These strategies included:

- Enhanced documentation with regard to antimicrobial prescribing and use

- Improved quality and accessibility of guidelines for common infections

- Adoption of a 72-hour antibiotic timeout to reassess a patient’s antibiotic treatment plan once culture results were available

Each hospital used its own particular antibiotic stewardship practice data to educate and inform its physicians, which Dr. Mack says was important to the success of interventions because it was “concrete and realistic.”

The study found that in two hospitals, complete antibiotic documentation in patient records increased to 51% from 4% and to 65% from 8%. It also recorded 726 antibiotic timeouts, resulting in 218 antibiotic treatment adjustments or discontinuations. It also found several barriers to improved antibiotic stewardship.

“[Hospitalists] are stretched for time. We’re constantly being pulled in multiple directions,” Dr. Mack says. “We are bombarded daily with quality improvement initiatives and with constantly meeting metrics deemed to be priorities, so we tried interventions that were easily incorporated into daily workflow.”

The team learned that workflow integration was a requirement for success. For instance, Dr. Mack suggests building antibiotic prescribing into hospitalists’ electronic health records, with automatic stop dates that must be overridden by a physician. “It’s too easy to overlook it, and 10 days later, your patient is still on vancomycin.”

The experience, she says, made her fellow physicians in the collaborative realize that, despite some skepticism, good antimicrobial stewardship can be achieved without significant disruption.

“If we don’t change our practice patterns, there are not enough antibiotics in the pipeline to mitigate the effects,” of resistance, says Dr. Howell, who was not involved in the study. “We can’t stop resistance, but we can change our practice patterns so we slow the rate of resistance and give ourselves time to develop new therapies to treat infections.”

This includes behavioral changes hospitalists can easily incorporate, Dr. Howell says, which align with the strategies assessed in Dr. Mack’s study. These include rethinking the treatment time course, antibiotic timeouts, and adhering to prescribing guidelines.

Hospitalists, he says, are well-positioned to lead antibiotic stewardship efforts.

“We’re quality improvement experts … and there are not enough infectious disease physicians in the country to roll out antibiotic stewardship programs, so there is space for hospitalists,” Dr. Howell explains. “In every hospital, we are prescribing these medications, so we own the problem.” TH

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

References

- Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(2):161-168. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7.

- McGann P, Snesrud E, Maybank R, et al. Escherichia coli harboring mcr-1 and blaCTX-M on a novel IncF plasmid: First report of mcr-1 in the USA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(7):4420-4421.

- Mack MR, Rohde JM, Jacobsen D, et al. Engaging hospitalists in antimicrobial stewardship: Lessons from a multihospital collaborative [published online ahead of print on April 30, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2599.

In 2015, researchers in China announced they had found for the first time a bacterial gene conferring resistance to colistin. The gene was present in samples from agricultural animals and in 1% of tested patients.1 Colistin, an antibiotic from the 1950s, is rarely prescribed; it is often considered an antibiotic of last resort.

In May 2016, the U.S. Department of Defense announced this gene, called mcr-1, had been found in E. coli isolated from the urine of a patient in Pennsylvania presenting with symptoms of a urinary tract infection.2 Subsequent surveillance also found mcr-1 E. coli in a pig.

The news has been met with grave concern by public health officials, scientists, infectious disease specialists, and countless physicians around the U.S. It has also served as a reminder that good antibiotic stewardship is a national, if not international, imperative.

“The recent discovery of a plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene, mcr-1, heralds the emergence of truly pan-drug resistant bacteria,” the authors of the recent U.S. study, from the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, wrote in their opening sentence.

In November 2015, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) launched an antibiotic stewardship campaign, “Fight the Resistance,” in partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hospitalists around the country have taken the lead on confronting the issue head on.

When the CDC and the White House called for action last year, “SHM jumped in with both feet,” says Eric Howell, MD, MHM, SHM’s senior physician advisor, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview, and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. The “Fight the Resistance” campaign calls for the nation’s 44,000 hospitalists to commit to responsible antibiotic-prescribing practices.

“While it’s extremely alarming, leading up to this, we knew there was a crisis of antibiotic resistance,” says Megan Mack, MD, a hospitalist and clinical instructor in the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “We know more antibiotic use is not the answer, stronger is not the answer. We need to be peeling back antibiotic use, honing when we need them, narrowing how we use them as much as possible, and keeping the duration as short as possible.”

Dr. Mack is first author of a new study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine that examines hospitalist-driven antibiotic stewardship efforts in five hospitals around the country.3

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement, with the CDC, recruited Dr. Mack and her study coauthors, hospitalists Jeff Rohde, MD, and Scott Flanders, MD, MHM, to participate.

“We were interested in the opportunity to put into place interventions in five different hospitals and to be able to share our successes and our barriers, which we did twice monthly,” Dr. Mack says.

Each hospital in the collaborative, which included teaching and non-teaching community hospitals and academic medical centers, focused on its own data and tailored its stewardship interventions to three strategies shown to be quality indicators of successful stewardship programs.

These strategies included:

- Enhanced documentation with regard to antimicrobial prescribing and use

- Improved quality and accessibility of guidelines for common infections

- Adoption of a 72-hour antibiotic timeout to reassess a patient’s antibiotic treatment plan once culture results were available

Each hospital used its own particular antibiotic stewardship practice data to educate and inform its physicians, which Dr. Mack says was important to the success of interventions because it was “concrete and realistic.”

The study found that in two hospitals, complete antibiotic documentation in patient records increased to 51% from 4% and to 65% from 8%. It also recorded 726 antibiotic timeouts, resulting in 218 antibiotic treatment adjustments or discontinuations. It also found several barriers to improved antibiotic stewardship.

“[Hospitalists] are stretched for time. We’re constantly being pulled in multiple directions,” Dr. Mack says. “We are bombarded daily with quality improvement initiatives and with constantly meeting metrics deemed to be priorities, so we tried interventions that were easily incorporated into daily workflow.”

The team learned that workflow integration was a requirement for success. For instance, Dr. Mack suggests building antibiotic prescribing into hospitalists’ electronic health records, with automatic stop dates that must be overridden by a physician. “It’s too easy to overlook it, and 10 days later, your patient is still on vancomycin.”

The experience, she says, made her fellow physicians in the collaborative realize that, despite some skepticism, good antimicrobial stewardship can be achieved without significant disruption.

“If we don’t change our practice patterns, there are not enough antibiotics in the pipeline to mitigate the effects,” of resistance, says Dr. Howell, who was not involved in the study. “We can’t stop resistance, but we can change our practice patterns so we slow the rate of resistance and give ourselves time to develop new therapies to treat infections.”

This includes behavioral changes hospitalists can easily incorporate, Dr. Howell says, which align with the strategies assessed in Dr. Mack’s study. These include rethinking the treatment time course, antibiotic timeouts, and adhering to prescribing guidelines.

Hospitalists, he says, are well-positioned to lead antibiotic stewardship efforts.

“We’re quality improvement experts … and there are not enough infectious disease physicians in the country to roll out antibiotic stewardship programs, so there is space for hospitalists,” Dr. Howell explains. “In every hospital, we are prescribing these medications, so we own the problem.” TH

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

References

- Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(2):161-168. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7.

- McGann P, Snesrud E, Maybank R, et al. Escherichia coli harboring mcr-1 and blaCTX-M on a novel IncF plasmid: First report of mcr-1 in the USA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(7):4420-4421.

- Mack MR, Rohde JM, Jacobsen D, et al. Engaging hospitalists in antimicrobial stewardship: Lessons from a multihospital collaborative [published online ahead of print on April 30, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2599.

MCR-1 gene a growing concern for antibiotic resistance

The MCR-1 gene is quickly emerging as a powerful roadblock in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacteria, according to experts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Alex J. Kallen, MD, of the CDC in Atlanta, said in an Aug. 2 webinar – cohosted by CDC and the Partnership for Quality Care – that the CDC is closely monitoring the emergence of antibiotic resistant bacteria in the United States. The prevailing message of Dr. Kallen and his CDC colleague Arjun Srinivasan, MD was that the importance of the MCR-1 gene should not be underestimated.

First discovered in a human patient last year, the presence of the MCR-1 gene makes bacteria resistant to colistin, an antibiotic used often as a last resort to “treat patients with multidrug-resistant infections,” according to the CDC. Because the MCR-1 gene exists on a plasmid, or a small piece of DNA, it is easily transferable among bacteria, making it a problem for health care providers treating a patient infected with bacteria that has the gene.

“As of this year, all state and some local health departments will be funded to respond to [antibiotic resistance] threats, including emerging threats like [MCR-1], within their jurisdiction,” Dr. Kallen said. This funding could be used to support technical assistance, contact investigations, and laboratory testing, among other things.

In order to help prevent the spread of MCR-1 and mitigate cases of novel antimicrobial resistance, health care providers and facilities should institute recommended intensive care precautions as soon as resistance is identified, along with alerting their local public health office. Isolates should be saved, and prospective and retrospective surveillance should be implemented to “identify isolates with similar phenotypes.” If an infected patient is being transferred to another facility, that facility should be notified ahead of time about the patient and what protocols to follow.

Because antibiotic-resistant organisms do not spread through the air like influenza, the risk that these organisms pose to health care workers is relatively low, Dr. Srinivasan explained. However, he stressed that a multifaceted, team-based approach to antibiotic stewardship and decontamination of health care facilities is absolutely necessary to achieve the best results for both patients and staff.

“We are now beginning to recognize that the contamination of surfaces and items in our health care environment is increasingly a problem in the transmission of these drug-resistant organisms,” Dr. Srinivasan explained. He said that, given the complexity of a typical health care environment, such as a hospital room or operating theater, it’s perhaps not so surprising that keeping everything clean is not the top priority.

In addition to making sure hospital rooms and other areas are properly cleaned, simple things like washing hands and keeping surfaces clean are just as important. Dr. Srinivasan pointed to a 2006 study by Philip C. Carling, MD, and his associates which showed that educational interventions can lead to substantial increases in hygiene and cleanliness, and that training of new staff is also important. Furthermore, giving staff enough time to properly clean rooms could significantly contribute to curtailing MCR-1 bacteria from spreading, he said.

“The other thing to keep in mind is that if we lose effective therapy, if we lose antibiotic therapy, the infections that are currently very treatable and are seldom deadly could again become very, very serious threats to life,” Dr. Srinivasan warned, specifically citing Escherichia coli, which is the leading cause of urinary tract infections. If community strains of E.coli become resistant to typical antibiotic treatment, these cases could become “difficult, if not impossible to treat.”

According to data shared by Dr. Srinivasan, in 2013 there were 2,049,422 illnesses in the United States attributed to antibiotic resistance and 23,000 fatalities.

The MCR-1 gene is quickly emerging as a powerful roadblock in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacteria, according to experts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Alex J. Kallen, MD, of the CDC in Atlanta, said in an Aug. 2 webinar – cohosted by CDC and the Partnership for Quality Care – that the CDC is closely monitoring the emergence of antibiotic resistant bacteria in the United States. The prevailing message of Dr. Kallen and his CDC colleague Arjun Srinivasan, MD was that the importance of the MCR-1 gene should not be underestimated.

First discovered in a human patient last year, the presence of the MCR-1 gene makes bacteria resistant to colistin, an antibiotic used often as a last resort to “treat patients with multidrug-resistant infections,” according to the CDC. Because the MCR-1 gene exists on a plasmid, or a small piece of DNA, it is easily transferable among bacteria, making it a problem for health care providers treating a patient infected with bacteria that has the gene.

“As of this year, all state and some local health departments will be funded to respond to [antibiotic resistance] threats, including emerging threats like [MCR-1], within their jurisdiction,” Dr. Kallen said. This funding could be used to support technical assistance, contact investigations, and laboratory testing, among other things.

In order to help prevent the spread of MCR-1 and mitigate cases of novel antimicrobial resistance, health care providers and facilities should institute recommended intensive care precautions as soon as resistance is identified, along with alerting their local public health office. Isolates should be saved, and prospective and retrospective surveillance should be implemented to “identify isolates with similar phenotypes.” If an infected patient is being transferred to another facility, that facility should be notified ahead of time about the patient and what protocols to follow.

Because antibiotic-resistant organisms do not spread through the air like influenza, the risk that these organisms pose to health care workers is relatively low, Dr. Srinivasan explained. However, he stressed that a multifaceted, team-based approach to antibiotic stewardship and decontamination of health care facilities is absolutely necessary to achieve the best results for both patients and staff.

“We are now beginning to recognize that the contamination of surfaces and items in our health care environment is increasingly a problem in the transmission of these drug-resistant organisms,” Dr. Srinivasan explained. He said that, given the complexity of a typical health care environment, such as a hospital room or operating theater, it’s perhaps not so surprising that keeping everything clean is not the top priority.

In addition to making sure hospital rooms and other areas are properly cleaned, simple things like washing hands and keeping surfaces clean are just as important. Dr. Srinivasan pointed to a 2006 study by Philip C. Carling, MD, and his associates which showed that educational interventions can lead to substantial increases in hygiene and cleanliness, and that training of new staff is also important. Furthermore, giving staff enough time to properly clean rooms could significantly contribute to curtailing MCR-1 bacteria from spreading, he said.

“The other thing to keep in mind is that if we lose effective therapy, if we lose antibiotic therapy, the infections that are currently very treatable and are seldom deadly could again become very, very serious threats to life,” Dr. Srinivasan warned, specifically citing Escherichia coli, which is the leading cause of urinary tract infections. If community strains of E.coli become resistant to typical antibiotic treatment, these cases could become “difficult, if not impossible to treat.”

According to data shared by Dr. Srinivasan, in 2013 there were 2,049,422 illnesses in the United States attributed to antibiotic resistance and 23,000 fatalities.

The MCR-1 gene is quickly emerging as a powerful roadblock in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacteria, according to experts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Alex J. Kallen, MD, of the CDC in Atlanta, said in an Aug. 2 webinar – cohosted by CDC and the Partnership for Quality Care – that the CDC is closely monitoring the emergence of antibiotic resistant bacteria in the United States. The prevailing message of Dr. Kallen and his CDC colleague Arjun Srinivasan, MD was that the importance of the MCR-1 gene should not be underestimated.

First discovered in a human patient last year, the presence of the MCR-1 gene makes bacteria resistant to colistin, an antibiotic used often as a last resort to “treat patients with multidrug-resistant infections,” according to the CDC. Because the MCR-1 gene exists on a plasmid, or a small piece of DNA, it is easily transferable among bacteria, making it a problem for health care providers treating a patient infected with bacteria that has the gene.

“As of this year, all state and some local health departments will be funded to respond to [antibiotic resistance] threats, including emerging threats like [MCR-1], within their jurisdiction,” Dr. Kallen said. This funding could be used to support technical assistance, contact investigations, and laboratory testing, among other things.

In order to help prevent the spread of MCR-1 and mitigate cases of novel antimicrobial resistance, health care providers and facilities should institute recommended intensive care precautions as soon as resistance is identified, along with alerting their local public health office. Isolates should be saved, and prospective and retrospective surveillance should be implemented to “identify isolates with similar phenotypes.” If an infected patient is being transferred to another facility, that facility should be notified ahead of time about the patient and what protocols to follow.

Because antibiotic-resistant organisms do not spread through the air like influenza, the risk that these organisms pose to health care workers is relatively low, Dr. Srinivasan explained. However, he stressed that a multifaceted, team-based approach to antibiotic stewardship and decontamination of health care facilities is absolutely necessary to achieve the best results for both patients and staff.

“We are now beginning to recognize that the contamination of surfaces and items in our health care environment is increasingly a problem in the transmission of these drug-resistant organisms,” Dr. Srinivasan explained. He said that, given the complexity of a typical health care environment, such as a hospital room or operating theater, it’s perhaps not so surprising that keeping everything clean is not the top priority.

In addition to making sure hospital rooms and other areas are properly cleaned, simple things like washing hands and keeping surfaces clean are just as important. Dr. Srinivasan pointed to a 2006 study by Philip C. Carling, MD, and his associates which showed that educational interventions can lead to substantial increases in hygiene and cleanliness, and that training of new staff is also important. Furthermore, giving staff enough time to properly clean rooms could significantly contribute to curtailing MCR-1 bacteria from spreading, he said.

“The other thing to keep in mind is that if we lose effective therapy, if we lose antibiotic therapy, the infections that are currently very treatable and are seldom deadly could again become very, very serious threats to life,” Dr. Srinivasan warned, specifically citing Escherichia coli, which is the leading cause of urinary tract infections. If community strains of E.coli become resistant to typical antibiotic treatment, these cases could become “difficult, if not impossible to treat.”

According to data shared by Dr. Srinivasan, in 2013 there were 2,049,422 illnesses in the United States attributed to antibiotic resistance and 23,000 fatalities.

U.S. to jump-start antibiotic resistance research

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing $67 million to help U.S. health departments address antibiotic resistance and related patient safety concerns.

The new funding was made available through the CDC’s Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement (ELC), according to a CDC statement, and will support seven new regional laboratories with specialized capabilities allowing rapid detection and identification of emerging antibiotic resistant threats.

The CDC said it would distribute funds to all 50 state health departments, six local health departments (Chicago, the District of Columbia, Houston, Los Angeles County, New York City, and Philadelphia), and Puerto Rico, beginning Aug. 1, 2016. The agency said the grants would allow every state health department lab to test for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and ultimately perform whole genome sequencing on intestinal bacteria, including Salmonella, Shigella, and many Campylobacter strains.

The agency intends to provide support teams in nine state health departments for rapid response activities designed to “quickly identify and respond to the threat” of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea in the United States, and will support high-level expertise to implement antimicrobial resistance activities in six states.

The CDC also said the promised funding would strengthen states’ ability to conduct foodborne disease tracking, investigation, and prevention, as it includes increased support for the PulseNet and OutbreakNet systems and for the Integrated Food Safety Centers of Excellence, as well as support for the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS).

Global partnerships

Complementing the new CDC grants was an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services that it would partner with the Wellcome Trust of London, the AMR Centre of Alderley Park (Cheshire, U.K.), and Boston University School of Law to create one of the world’s largest public-private partnerships focused on preclinical discovery and development of new antimicrobial products.

According to an HHS statement, the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) will bring together “multiple domestic and international partners and capabilities to find potential antibiotics and move them through preclinical testing to enable safety and efficacy testing in humans and greatly reducing the business risk,” to make antimicrobial development more attractive to private sector investment.

HHS said the federal Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) would provide $30 million during the first year of CARB-X, and up to $250 million during the 5-year project. CARB-X will provide funding for research and development, and technical assistance for companies with innovative and promising solutions to antibiotic resistance, HHS said.

“Our hope is that the combination of technical expertise and life science entrepreneurship experience within the CARB-X’s life science accelerators will remove barriers for companies pursuing the development of the next novel drug, diagnostic, or vaccine to combat this public health threat,” said Joe Larsen, PhD, acting BARDA deputy director, in the HHS statement.

On Twitter @richpizzi

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing $67 million to help U.S. health departments address antibiotic resistance and related patient safety concerns.

The new funding was made available through the CDC’s Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement (ELC), according to a CDC statement, and will support seven new regional laboratories with specialized capabilities allowing rapid detection and identification of emerging antibiotic resistant threats.

The CDC said it would distribute funds to all 50 state health departments, six local health departments (Chicago, the District of Columbia, Houston, Los Angeles County, New York City, and Philadelphia), and Puerto Rico, beginning Aug. 1, 2016. The agency said the grants would allow every state health department lab to test for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and ultimately perform whole genome sequencing on intestinal bacteria, including Salmonella, Shigella, and many Campylobacter strains.

The agency intends to provide support teams in nine state health departments for rapid response activities designed to “quickly identify and respond to the threat” of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea in the United States, and will support high-level expertise to implement antimicrobial resistance activities in six states.

The CDC also said the promised funding would strengthen states’ ability to conduct foodborne disease tracking, investigation, and prevention, as it includes increased support for the PulseNet and OutbreakNet systems and for the Integrated Food Safety Centers of Excellence, as well as support for the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS).

Global partnerships

Complementing the new CDC grants was an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services that it would partner with the Wellcome Trust of London, the AMR Centre of Alderley Park (Cheshire, U.K.), and Boston University School of Law to create one of the world’s largest public-private partnerships focused on preclinical discovery and development of new antimicrobial products.

According to an HHS statement, the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) will bring together “multiple domestic and international partners and capabilities to find potential antibiotics and move them through preclinical testing to enable safety and efficacy testing in humans and greatly reducing the business risk,” to make antimicrobial development more attractive to private sector investment.

HHS said the federal Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) would provide $30 million during the first year of CARB-X, and up to $250 million during the 5-year project. CARB-X will provide funding for research and development, and technical assistance for companies with innovative and promising solutions to antibiotic resistance, HHS said.

“Our hope is that the combination of technical expertise and life science entrepreneurship experience within the CARB-X’s life science accelerators will remove barriers for companies pursuing the development of the next novel drug, diagnostic, or vaccine to combat this public health threat,” said Joe Larsen, PhD, acting BARDA deputy director, in the HHS statement.

On Twitter @richpizzi

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing $67 million to help U.S. health departments address antibiotic resistance and related patient safety concerns.

The new funding was made available through the CDC’s Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement (ELC), according to a CDC statement, and will support seven new regional laboratories with specialized capabilities allowing rapid detection and identification of emerging antibiotic resistant threats.

The CDC said it would distribute funds to all 50 state health departments, six local health departments (Chicago, the District of Columbia, Houston, Los Angeles County, New York City, and Philadelphia), and Puerto Rico, beginning Aug. 1, 2016. The agency said the grants would allow every state health department lab to test for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and ultimately perform whole genome sequencing on intestinal bacteria, including Salmonella, Shigella, and many Campylobacter strains.

The agency intends to provide support teams in nine state health departments for rapid response activities designed to “quickly identify and respond to the threat” of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea in the United States, and will support high-level expertise to implement antimicrobial resistance activities in six states.

The CDC also said the promised funding would strengthen states’ ability to conduct foodborne disease tracking, investigation, and prevention, as it includes increased support for the PulseNet and OutbreakNet systems and for the Integrated Food Safety Centers of Excellence, as well as support for the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS).

Global partnerships

Complementing the new CDC grants was an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services that it would partner with the Wellcome Trust of London, the AMR Centre of Alderley Park (Cheshire, U.K.), and Boston University School of Law to create one of the world’s largest public-private partnerships focused on preclinical discovery and development of new antimicrobial products.

According to an HHS statement, the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) will bring together “multiple domestic and international partners and capabilities to find potential antibiotics and move them through preclinical testing to enable safety and efficacy testing in humans and greatly reducing the business risk,” to make antimicrobial development more attractive to private sector investment.

HHS said the federal Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) would provide $30 million during the first year of CARB-X, and up to $250 million during the 5-year project. CARB-X will provide funding for research and development, and technical assistance for companies with innovative and promising solutions to antibiotic resistance, HHS said.

“Our hope is that the combination of technical expertise and life science entrepreneurship experience within the CARB-X’s life science accelerators will remove barriers for companies pursuing the development of the next novel drug, diagnostic, or vaccine to combat this public health threat,” said Joe Larsen, PhD, acting BARDA deputy director, in the HHS statement.

On Twitter @richpizzi

Superbug Infections On the Rise With No Antibiotic Success Yet

NEW YORK - After two confirmed U.S. cases of a superbug that thwarts a last-resort antibiotic, infectious disease experts say they expect more cases in coming months because the bacterial gene behind it is likely far more widespread than previously believed.

Army scientists in May reported finding E. coli bacteria that harbor a gene which renders the antibiotic colistin useless. The gene, called mcr-1, was found in a urine sample of a Pennsylvania woman being treated for a urinary tract infection.

On Monday, researchers confirmed preliminary findings that E. coli carrying the same mcr-1 gene were found in a stored bacterial sample of a New York patient who had been treated for an infection last year, as well as in patient samples from nine other countries.

The report came from a global effort called the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, led by Mariana Castanheira of JMI Laboratories based in North Liberty, Iowa.

The mcr-1 superbug has been identified over the past six months in farm animals and people in about 20 countries, including China, Germany and Italy.

The bacteria can be transmitted by fecal contact and poor hygiene, which suggests a far wider likely presence than the documented cases so far, according to leading infectious disease experts.

Health officials fear the mcr-1 gene, carried by a highly mobile piece of DNA called a plasmid, will soon be found in bacteria already resistant to all or virtually all other types of antibiotics, potentially making infections untreatable.

"You can be sure (mcr-1) is already in the guts of people throughout the United States and will continue to spread," said Dr. Brad Spellberg, professor of medicine at the University of Southern California.

Dr. David Van Duin, an infectious disease expert at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, said he expects more documented U.S. cases of mcr-1 in coming months because it is already here and will spread from abroad. "We will see a lot more of this gene."

Colistin causes kidney damage, but doctors have opted for it as other antibiotics increasingly fail. Its overuse, especially in overseas farm animals, has allowed bacteria to develop resistance to it.

PAST AND PRESENT INFECTIONS

To track the mcr-1 gene, U.S. hospitals are working together with state and federal agencies to test bacteria samples of patients that have recently been treated for infections. Many of the largest research hospitals are examining samples of antibiotic-resistant bacteria that have long been stored in their freezers.

Gautam Dantas, associate professor of pathology at Washington University Medical Center in St. Louis, has tested hundreds of U.S. samples of archived bacteria in recent months and has not yet detected mcr-1. But he expects dozens of confirmed cases of the gene will be documented by next year in the country, mostly among current patients.

The concern of many disease experts is that mcr-1 could soon show up in bacteria also resistant to carbapenems, one of the few remaining dependable classes of antibiotics. In that event, with colistin no longer a last-ditch option, some patients would have to rely on their immune systems to fight off infection.

"Within the next two to three years, it's going to be fairly routine for infections to occur in the United States for which we have no (effective) drugs available," Dantas said.

Castanheira also believes mcr-1 will find its way into carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE).

In an interview, she said the resulting virtually impervious bacterium would likely spread slowly inside the United States because CRE themselves are not yet widespread in the country, giving drugmakers some time to create new antibiotics.

Beginning in August, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will use $21 million to expand surveillance at laboratories operated by all 50 state health departments and seven larger regional labs. The federal funding will help pay for more-sensitive equipment to test for antibiotic resistance in bacteria samples provided by hospitals.

Jean Patel, deputy director of the CDC's Office of Antimicrobial Resistance, said the effort will provide the CDC improved national surveillance of antibiotic-resistance trends, including any spread of mcr-1.

"This is data for action," she said, adding that special procedures to prevent infections from spreading in hospitals could be taken once a patient is identified with mcr-1 related infections or with multidrug-resistant bacteria.

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/29yFekw

Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016.

NEW YORK - After two confirmed U.S. cases of a superbug that thwarts a last-resort antibiotic, infectious disease experts say they expect more cases in coming months because the bacterial gene behind it is likely far more widespread than previously believed.

Army scientists in May reported finding E. coli bacteria that harbor a gene which renders the antibiotic colistin useless. The gene, called mcr-1, was found in a urine sample of a Pennsylvania woman being treated for a urinary tract infection.

On Monday, researchers confirmed preliminary findings that E. coli carrying the same mcr-1 gene were found in a stored bacterial sample of a New York patient who had been treated for an infection last year, as well as in patient samples from nine other countries.

The report came from a global effort called the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, led by Mariana Castanheira of JMI Laboratories based in North Liberty, Iowa.

The mcr-1 superbug has been identified over the past six months in farm animals and people in about 20 countries, including China, Germany and Italy.

The bacteria can be transmitted by fecal contact and poor hygiene, which suggests a far wider likely presence than the documented cases so far, according to leading infectious disease experts.

Health officials fear the mcr-1 gene, carried by a highly mobile piece of DNA called a plasmid, will soon be found in bacteria already resistant to all or virtually all other types of antibiotics, potentially making infections untreatable.

"You can be sure (mcr-1) is already in the guts of people throughout the United States and will continue to spread," said Dr. Brad Spellberg, professor of medicine at the University of Southern California.

Dr. David Van Duin, an infectious disease expert at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, said he expects more documented U.S. cases of mcr-1 in coming months because it is already here and will spread from abroad. "We will see a lot more of this gene."

Colistin causes kidney damage, but doctors have opted for it as other antibiotics increasingly fail. Its overuse, especially in overseas farm animals, has allowed bacteria to develop resistance to it.

PAST AND PRESENT INFECTIONS

To track the mcr-1 gene, U.S. hospitals are working together with state and federal agencies to test bacteria samples of patients that have recently been treated for infections. Many of the largest research hospitals are examining samples of antibiotic-resistant bacteria that have long been stored in their freezers.

Gautam Dantas, associate professor of pathology at Washington University Medical Center in St. Louis, has tested hundreds of U.S. samples of archived bacteria in recent months and has not yet detected mcr-1. But he expects dozens of confirmed cases of the gene will be documented by next year in the country, mostly among current patients.

The concern of many disease experts is that mcr-1 could soon show up in bacteria also resistant to carbapenems, one of the few remaining dependable classes of antibiotics. In that event, with colistin no longer a last-ditch option, some patients would have to rely on their immune systems to fight off infection.

"Within the next two to three years, it's going to be fairly routine for infections to occur in the United States for which we have no (effective) drugs available," Dantas said.

Castanheira also believes mcr-1 will find its way into carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE).

In an interview, she said the resulting virtually impervious bacterium would likely spread slowly inside the United States because CRE themselves are not yet widespread in the country, giving drugmakers some time to create new antibiotics.

Beginning in August, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will use $21 million to expand surveillance at laboratories operated by all 50 state health departments and seven larger regional labs. The federal funding will help pay for more-sensitive equipment to test for antibiotic resistance in bacteria samples provided by hospitals.

Jean Patel, deputy director of the CDC's Office of Antimicrobial Resistance, said the effort will provide the CDC improved national surveillance of antibiotic-resistance trends, including any spread of mcr-1.

"This is data for action," she said, adding that special procedures to prevent infections from spreading in hospitals could be taken once a patient is identified with mcr-1 related infections or with multidrug-resistant bacteria.

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/29yFekw

Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016.

NEW YORK - After two confirmed U.S. cases of a superbug that thwarts a last-resort antibiotic, infectious disease experts say they expect more cases in coming months because the bacterial gene behind it is likely far more widespread than previously believed.

Army scientists in May reported finding E. coli bacteria that harbor a gene which renders the antibiotic colistin useless. The gene, called mcr-1, was found in a urine sample of a Pennsylvania woman being treated for a urinary tract infection.

On Monday, researchers confirmed preliminary findings that E. coli carrying the same mcr-1 gene were found in a stored bacterial sample of a New York patient who had been treated for an infection last year, as well as in patient samples from nine other countries.

The report came from a global effort called the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, led by Mariana Castanheira of JMI Laboratories based in North Liberty, Iowa.

The mcr-1 superbug has been identified over the past six months in farm animals and people in about 20 countries, including China, Germany and Italy.

The bacteria can be transmitted by fecal contact and poor hygiene, which suggests a far wider likely presence than the documented cases so far, according to leading infectious disease experts.

Health officials fear the mcr-1 gene, carried by a highly mobile piece of DNA called a plasmid, will soon be found in bacteria already resistant to all or virtually all other types of antibiotics, potentially making infections untreatable.

"You can be sure (mcr-1) is already in the guts of people throughout the United States and will continue to spread," said Dr. Brad Spellberg, professor of medicine at the University of Southern California.

Dr. David Van Duin, an infectious disease expert at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, said he expects more documented U.S. cases of mcr-1 in coming months because it is already here and will spread from abroad. "We will see a lot more of this gene."

Colistin causes kidney damage, but doctors have opted for it as other antibiotics increasingly fail. Its overuse, especially in overseas farm animals, has allowed bacteria to develop resistance to it.

PAST AND PRESENT INFECTIONS

To track the mcr-1 gene, U.S. hospitals are working together with state and federal agencies to test bacteria samples of patients that have recently been treated for infections. Many of the largest research hospitals are examining samples of antibiotic-resistant bacteria that have long been stored in their freezers.

Gautam Dantas, associate professor of pathology at Washington University Medical Center in St. Louis, has tested hundreds of U.S. samples of archived bacteria in recent months and has not yet detected mcr-1. But he expects dozens of confirmed cases of the gene will be documented by next year in the country, mostly among current patients.

The concern of many disease experts is that mcr-1 could soon show up in bacteria also resistant to carbapenems, one of the few remaining dependable classes of antibiotics. In that event, with colistin no longer a last-ditch option, some patients would have to rely on their immune systems to fight off infection.

"Within the next two to three years, it's going to be fairly routine for infections to occur in the United States for which we have no (effective) drugs available," Dantas said.

Castanheira also believes mcr-1 will find its way into carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE).

In an interview, she said the resulting virtually impervious bacterium would likely spread slowly inside the United States because CRE themselves are not yet widespread in the country, giving drugmakers some time to create new antibiotics.

Beginning in August, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will use $21 million to expand surveillance at laboratories operated by all 50 state health departments and seven larger regional labs. The federal funding will help pay for more-sensitive equipment to test for antibiotic resistance in bacteria samples provided by hospitals.

Jean Patel, deputy director of the CDC's Office of Antimicrobial Resistance, said the effort will provide the CDC improved national surveillance of antibiotic-resistance trends, including any spread of mcr-1.

"This is data for action," she said, adding that special procedures to prevent infections from spreading in hospitals could be taken once a patient is identified with mcr-1 related infections or with multidrug-resistant bacteria.

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/29yFekw

Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016.

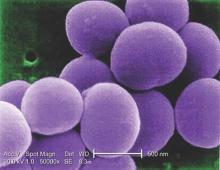

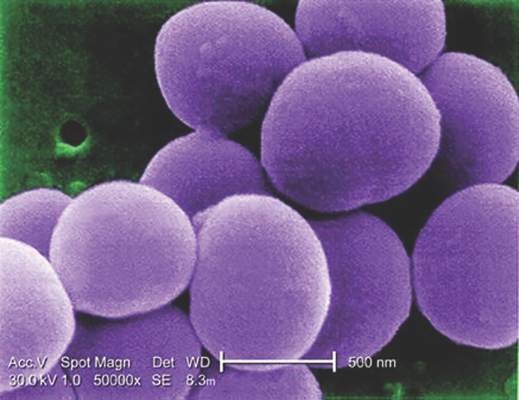

Staph aureus prevalent on U.S. freshwater beaches

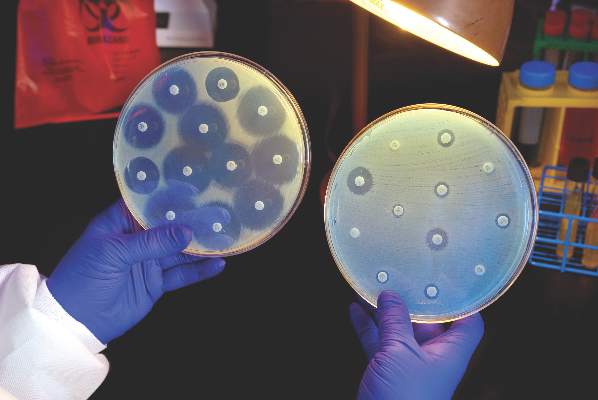

BOSTON – Almost half of all sand and water samples taken from Midwestern freshwater public beaches tested positive for Staphylococcus aureus isolates during the summertime, but numbers fell dramatically in the fall and spring.

Overall, according to a study of 10 public beaches in Ohio, almost half of the isolates were resistant to erythromycin, 41% were multidrug resistant, and about 7% were methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).

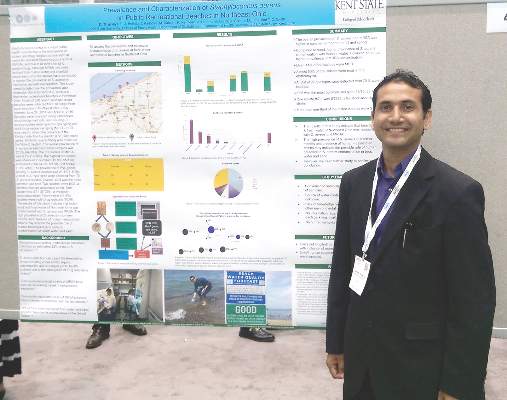

In addition, among the 70 S. aureus isolates, 21.4% had the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) gene, which encodes for a pore-forming toxin identified as a virulence factor in some strains of staphylococcus. The study results were presented by Dipendra Thapaliya, a research associate at Kent State University, Ohio,, during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

In light of these findings, the study’s senior author, Tara Smith, PhD, professor of epidemiology at the university, said in an interview that beachgoers should take reasonable precautions, including washing lake water and sand off young children upon returning home, and making sure to shower at the beach if facilities are available.

“Staphylococcus does well in a salty environment, but it is a fairly hardy organism,” Dr. Smith said, noting that S. aureus has been found in the sand and water of marine beaches, but it has been less well studied in freshwater environments.

Public beaches in Ohio were the source of the samples. Some sampling was done along the shores of Lake Erie, but smaller inland lakes also were tested, In all, 280 sand and water samples were collected in a 3:1 water to sand ratio.

The samples were incubated and plated for culture and subculture according to established methods, and then tested for S. aureus via catalase and coagulase testing, as well as latex agglutination testing. Isolates were then subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing, as well as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for the PVL gene and for the mecA genes found in MRSA. Final isolate identification was achieved by staphylococcal protein A (spa) and multilocus sequence typing.

Of the 27 spa types found from 70 isolates, two common strains, t008 and t002, were the most frequently detected. One livestock-associated strain, t571, was also identified.

Though beaches are frequently contaminated with E. coli and other enteric pathogens, the source is often birds or other wildlife, said Dr. Smith. To try to ascertain the source of the staphylococcus in the summer samples, Mr. Thapaliya and his collaborators repeated testing during the winter months and in the spring, before beachgoers had spent time at the waterside.

Those samples from the months when the beaches were empty of people showed much lower levels of S. aureus: In the summer, S. aureus isolates were found in almost half of the samples obtained (55/120, 45.8%). By contrast, only 5 of the 120 fall samples (4.8%) and 4 of the 40 spring samples (10%) were positive for S. aureus.

“The high prevalence of S. aureus in summer months and presence of human-associated strains may indicate the possible role of human presence in S. aureus contamination in beach water and sand. However, we need further study to confirm such a conclusion,” wrote Mr. Thapaliya and his coauthors.

To that end, Dr. Smith said that another, stronger piece of supporting evidence that the S. aureus does come from “the crush of human bathers” would be to identify and match isolates from individuals who frequent the beaches with isolates found in sand and water. Dr. Smith said that she and her team are currently seeking funding to carry out these next steps.

The investigators reported no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – Almost half of all sand and water samples taken from Midwestern freshwater public beaches tested positive for Staphylococcus aureus isolates during the summertime, but numbers fell dramatically in the fall and spring.

Overall, according to a study of 10 public beaches in Ohio, almost half of the isolates were resistant to erythromycin, 41% were multidrug resistant, and about 7% were methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).

In addition, among the 70 S. aureus isolates, 21.4% had the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) gene, which encodes for a pore-forming toxin identified as a virulence factor in some strains of staphylococcus. The study results were presented by Dipendra Thapaliya, a research associate at Kent State University, Ohio,, during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

In light of these findings, the study’s senior author, Tara Smith, PhD, professor of epidemiology at the university, said in an interview that beachgoers should take reasonable precautions, including washing lake water and sand off young children upon returning home, and making sure to shower at the beach if facilities are available.

“Staphylococcus does well in a salty environment, but it is a fairly hardy organism,” Dr. Smith said, noting that S. aureus has been found in the sand and water of marine beaches, but it has been less well studied in freshwater environments.

Public beaches in Ohio were the source of the samples. Some sampling was done along the shores of Lake Erie, but smaller inland lakes also were tested, In all, 280 sand and water samples were collected in a 3:1 water to sand ratio.

The samples were incubated and plated for culture and subculture according to established methods, and then tested for S. aureus via catalase and coagulase testing, as well as latex agglutination testing. Isolates were then subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing, as well as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for the PVL gene and for the mecA genes found in MRSA. Final isolate identification was achieved by staphylococcal protein A (spa) and multilocus sequence typing.

Of the 27 spa types found from 70 isolates, two common strains, t008 and t002, were the most frequently detected. One livestock-associated strain, t571, was also identified.

Though beaches are frequently contaminated with E. coli and other enteric pathogens, the source is often birds or other wildlife, said Dr. Smith. To try to ascertain the source of the staphylococcus in the summer samples, Mr. Thapaliya and his collaborators repeated testing during the winter months and in the spring, before beachgoers had spent time at the waterside.

Those samples from the months when the beaches were empty of people showed much lower levels of S. aureus: In the summer, S. aureus isolates were found in almost half of the samples obtained (55/120, 45.8%). By contrast, only 5 of the 120 fall samples (4.8%) and 4 of the 40 spring samples (10%) were positive for S. aureus.

“The high prevalence of S. aureus in summer months and presence of human-associated strains may indicate the possible role of human presence in S. aureus contamination in beach water and sand. However, we need further study to confirm such a conclusion,” wrote Mr. Thapaliya and his coauthors.

To that end, Dr. Smith said that another, stronger piece of supporting evidence that the S. aureus does come from “the crush of human bathers” would be to identify and match isolates from individuals who frequent the beaches with isolates found in sand and water. Dr. Smith said that she and her team are currently seeking funding to carry out these next steps.

The investigators reported no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – Almost half of all sand and water samples taken from Midwestern freshwater public beaches tested positive for Staphylococcus aureus isolates during the summertime, but numbers fell dramatically in the fall and spring.

Overall, according to a study of 10 public beaches in Ohio, almost half of the isolates were resistant to erythromycin, 41% were multidrug resistant, and about 7% were methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).

In addition, among the 70 S. aureus isolates, 21.4% had the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) gene, which encodes for a pore-forming toxin identified as a virulence factor in some strains of staphylococcus. The study results were presented by Dipendra Thapaliya, a research associate at Kent State University, Ohio,, during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

In light of these findings, the study’s senior author, Tara Smith, PhD, professor of epidemiology at the university, said in an interview that beachgoers should take reasonable precautions, including washing lake water and sand off young children upon returning home, and making sure to shower at the beach if facilities are available.

“Staphylococcus does well in a salty environment, but it is a fairly hardy organism,” Dr. Smith said, noting that S. aureus has been found in the sand and water of marine beaches, but it has been less well studied in freshwater environments.

Public beaches in Ohio were the source of the samples. Some sampling was done along the shores of Lake Erie, but smaller inland lakes also were tested, In all, 280 sand and water samples were collected in a 3:1 water to sand ratio.

The samples were incubated and plated for culture and subculture according to established methods, and then tested for S. aureus via catalase and coagulase testing, as well as latex agglutination testing. Isolates were then subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing, as well as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for the PVL gene and for the mecA genes found in MRSA. Final isolate identification was achieved by staphylococcal protein A (spa) and multilocus sequence typing.

Of the 27 spa types found from 70 isolates, two common strains, t008 and t002, were the most frequently detected. One livestock-associated strain, t571, was also identified.

Though beaches are frequently contaminated with E. coli and other enteric pathogens, the source is often birds or other wildlife, said Dr. Smith. To try to ascertain the source of the staphylococcus in the summer samples, Mr. Thapaliya and his collaborators repeated testing during the winter months and in the spring, before beachgoers had spent time at the waterside.

Those samples from the months when the beaches were empty of people showed much lower levels of S. aureus: In the summer, S. aureus isolates were found in almost half of the samples obtained (55/120, 45.8%). By contrast, only 5 of the 120 fall samples (4.8%) and 4 of the 40 spring samples (10%) were positive for S. aureus.

“The high prevalence of S. aureus in summer months and presence of human-associated strains may indicate the possible role of human presence in S. aureus contamination in beach water and sand. However, we need further study to confirm such a conclusion,” wrote Mr. Thapaliya and his coauthors.

To that end, Dr. Smith said that another, stronger piece of supporting evidence that the S. aureus does come from “the crush of human bathers” would be to identify and match isolates from individuals who frequent the beaches with isolates found in sand and water. Dr. Smith said that she and her team are currently seeking funding to carry out these next steps.

The investigators reported no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT ASM MICROBE 2016

Key clinical point: Almost half of summertime sand and water samples were positive for Staphylococcus aureus.

Major finding: Of 120 summertime samples, 55 (45.8%) were positive for S. aureus.

Data source: Sand and water samples (n = 280) from 10 freshwater beaches in the upper Midwest.

Disclosures: The study investigators reported no disclosures.

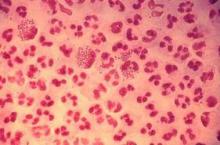

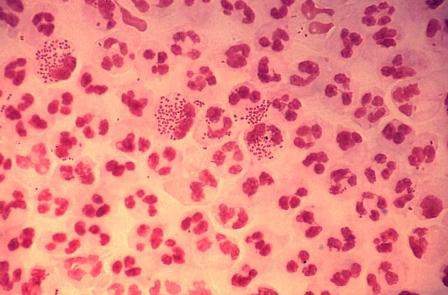

Study finds emergence of azithromycin-resistant gonorrhea

Resistance to azithromycin and to a lesser degree cephalosporin antibiotics was observed in patients with gonorrhea, according to an analysis of 2014 data from a national surveillance system,

“It is unclear whether these increases mark the beginning of trends, but emergence of cephalosporin and azithromycin resistance would complicate gonorrhea treatment substantially,” reported Robert D. Kirkcaldy, MD, and his colleagues. The results were published July 15 in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Dr. Kirkcaldy of the CDC’s Division of STD Prevention, Atlanta, and his coinvestigators evaluated 2014 data from the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP), which the CDC established in 1986 to monitor trends in antimicrobial susceptibilities of Neisseri. gonorrhoeae strains in the United States. The N. gonorrhoeae isolates are collected at 27 participating STD clinics each month from up to the first 25 men with gonococcal urethritis who present to the clinics.

In 2014, a total of 5,093 isolates were collected at the 27 sites. Among these, 25% demonstrated resistance to tetracycline, 19% to ciprofloxacin, and 16% to penicillin. At the same time, resistance to azithromycin increased from 0.6% in 2013 to 2.5% in 2014, predominantly in the Midwest.

Resistance to the cephalosporin antibiotic cefixime, meanwhile, increased from 0.1% in 2006 to 1.4% in 2010 and 2011, fell to 0.4% in 2013, and increased to 0.8% in 2014.

Resistance to the cephalosporin antibiotic ceftriaxone increased from 0.1% in 2008 to 0.4% in 2011, and decreased to 0.1% in 2013 and 2014).

“Local and state health departments can use GISP data to determine allocation of STD prevention services and resources, guide prevention planning, and communicate best treatment practices to health care providers,” the researchers wrote. “Continued surveillance, appropriate treatment, development of new antibiotics, and prevention of transmission remain the best strategies to reduce gonorrhea incidence and morbidity.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Resistance to azithromycin and to a lesser degree cephalosporin antibiotics was observed in patients with gonorrhea, according to an analysis of 2014 data from a national surveillance system,

“It is unclear whether these increases mark the beginning of trends, but emergence of cephalosporin and azithromycin resistance would complicate gonorrhea treatment substantially,” reported Robert D. Kirkcaldy, MD, and his colleagues. The results were published July 15 in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Dr. Kirkcaldy of the CDC’s Division of STD Prevention, Atlanta, and his coinvestigators evaluated 2014 data from the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP), which the CDC established in 1986 to monitor trends in antimicrobial susceptibilities of Neisseri. gonorrhoeae strains in the United States. The N. gonorrhoeae isolates are collected at 27 participating STD clinics each month from up to the first 25 men with gonococcal urethritis who present to the clinics.

In 2014, a total of 5,093 isolates were collected at the 27 sites. Among these, 25% demonstrated resistance to tetracycline, 19% to ciprofloxacin, and 16% to penicillin. At the same time, resistance to azithromycin increased from 0.6% in 2013 to 2.5% in 2014, predominantly in the Midwest.

Resistance to the cephalosporin antibiotic cefixime, meanwhile, increased from 0.1% in 2006 to 1.4% in 2010 and 2011, fell to 0.4% in 2013, and increased to 0.8% in 2014.

Resistance to the cephalosporin antibiotic ceftriaxone increased from 0.1% in 2008 to 0.4% in 2011, and decreased to 0.1% in 2013 and 2014).

“Local and state health departments can use GISP data to determine allocation of STD prevention services and resources, guide prevention planning, and communicate best treatment practices to health care providers,” the researchers wrote. “Continued surveillance, appropriate treatment, development of new antibiotics, and prevention of transmission remain the best strategies to reduce gonorrhea incidence and morbidity.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Resistance to azithromycin and to a lesser degree cephalosporin antibiotics was observed in patients with gonorrhea, according to an analysis of 2014 data from a national surveillance system,

“It is unclear whether these increases mark the beginning of trends, but emergence of cephalosporin and azithromycin resistance would complicate gonorrhea treatment substantially,” reported Robert D. Kirkcaldy, MD, and his colleagues. The results were published July 15 in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Dr. Kirkcaldy of the CDC’s Division of STD Prevention, Atlanta, and his coinvestigators evaluated 2014 data from the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP), which the CDC established in 1986 to monitor trends in antimicrobial susceptibilities of Neisseri. gonorrhoeae strains in the United States. The N. gonorrhoeae isolates are collected at 27 participating STD clinics each month from up to the first 25 men with gonococcal urethritis who present to the clinics.

In 2014, a total of 5,093 isolates were collected at the 27 sites. Among these, 25% demonstrated resistance to tetracycline, 19% to ciprofloxacin, and 16% to penicillin. At the same time, resistance to azithromycin increased from 0.6% in 2013 to 2.5% in 2014, predominantly in the Midwest.

Resistance to the cephalosporin antibiotic cefixime, meanwhile, increased from 0.1% in 2006 to 1.4% in 2010 and 2011, fell to 0.4% in 2013, and increased to 0.8% in 2014.

Resistance to the cephalosporin antibiotic ceftriaxone increased from 0.1% in 2008 to 0.4% in 2011, and decreased to 0.1% in 2013 and 2014).

“Local and state health departments can use GISP data to determine allocation of STD prevention services and resources, guide prevention planning, and communicate best treatment practices to health care providers,” the researchers wrote. “Continued surveillance, appropriate treatment, development of new antibiotics, and prevention of transmission remain the best strategies to reduce gonorrhea incidence and morbidity.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Key clinical point: Resistance to azithromycin is emerging among patients diagnosed with gonorrhea.

Major finding: Among patients with gonorrhea, resistance to azithromycin increased from 0.6% in 2013 to 2.5% in 2014, predominantly in the Midwest.

Data source: An analysis of 5,093 Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from 27 clinics as part of the CDC’s Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial disclosures.

New antibiotics targeting MDR pathogens are expensive, but not impressive

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved a number of new antibiotics targeting multidrug-resistant bacteria in the past 5 years, but the new drugs have not led to a substantial improvement in patient outcomes when compared with existing antibiotics, according to a recent analysis in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The eight new antibiotics approved by the FDA between January 2010 and December 2015 were ceftaroline, fidaxomicin, bedaquiline, dalbavancin, tedizolid, oritavancin, ceftolozane/tazobactam, and ceftazidime/avibactam. Of those eight drugs, only three showed in vitro activity against the so-called ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species). Only one drug, fidaxomicin, demonstrated in vitro activity against an urgent-threat pathogen from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Clostridium difficile. Bedaquiline was the only new antibiotic specifically indicated for a disease from a multidrug-resistant pathogen, although the investigators said most of the drugs demonstrated in vitro activity against gram-positive drug-resistant pathogens.

Importantly, the authors noted that in vitro activity does not necessarily reflect benefits on actual patient clinical outcomes, as exemplified by such drugs as tigecycline and doripenem.

The researchers found what they called “important deficiencies in the clinical trials leading to approval of these new antibiotic products.” Most pivotal trial designs were primarily noninferiority trials, and the antibiotics were not studied to evaluate whether they have substantial benefits in efficacy over what is currently available, they noted. Additionally, none of the trials evaluated direct patient outcomes as primary end points, and some drugs did not have confirmatory evidence from a second independent trial or did not have any confirmatory trials.

Researchers also examined the prices of a single dose of the new antibiotics. The prices ranged from $1,195 to $4,183 (4-14 days of ceftolozane/tazobactam for acute pyelonephritis and intra-abdominal infections) to $69,702 (24 weeks of bedaquiline) – quite a premium for antibiotics showing unclear evidence of additional benefit.

“As antibiotic innovation continues to move forward, greater attention needs to be paid to incentives for developing high-quality new products with demonstrated superiority to existing products on outcomes in patients with multidrug-resistant disease, replacing the current focus on quantity and presumed future benefits,” researchers concluded.

Read the full study in the Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M16-0291).

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved a number of new antibiotics targeting multidrug-resistant bacteria in the past 5 years, but the new drugs have not led to a substantial improvement in patient outcomes when compared with existing antibiotics, according to a recent analysis in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The eight new antibiotics approved by the FDA between January 2010 and December 2015 were ceftaroline, fidaxomicin, bedaquiline, dalbavancin, tedizolid, oritavancin, ceftolozane/tazobactam, and ceftazidime/avibactam. Of those eight drugs, only three showed in vitro activity against the so-called ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species). Only one drug, fidaxomicin, demonstrated in vitro activity against an urgent-threat pathogen from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Clostridium difficile. Bedaquiline was the only new antibiotic specifically indicated for a disease from a multidrug-resistant pathogen, although the investigators said most of the drugs demonstrated in vitro activity against gram-positive drug-resistant pathogens.

Importantly, the authors noted that in vitro activity does not necessarily reflect benefits on actual patient clinical outcomes, as exemplified by such drugs as tigecycline and doripenem.