User login

Ten recommendations for building and growing a cosmetic dermatology practice

SAN DIEGO – When Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD, opened his own cosmetic dermatology practice in Stamford, Conn., in 2012, he sensed that he had his work cut out for him.

“I was a fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon who wanted to do aesthetics,” Dr. Ibrahimi, medical director of the Connecticut Skin Institute, recalled during the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “I was in a geographic area that was new to me. I didn’t know any referring doctors, but I started to network and tried to grow my practice.”

Someone once told him that the “three As” of being a medical specialist are “Available, Affable, and Ability,” so he applied that principle as he began to cultivate relationships with physicians in his geographic area. “I told my referring doctors, ‘If you’re kind enough to send me Mohs cases, I’ll help you out if there’s something you don’t like doing, whether it’s a nail biopsy or treating male genital warts,’” he said. “You want to make it easy for doctors to refer to you, but you also want to make their lives easier.”

Dr. Ibrahimi, who is also on the board of directors for the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery and the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, offered . They include:

Know yourself. Do what you love to do, not what you feel like you should do. “Whatever you’re doing in your practice, it should be something that you’re passionate about and excited about,” he said. “I do a mix of Mohs surgery and procedural aesthetic dermatology. Most of my practice is shaped toward energy-based devices and laser procedures. Pick the things that you enjoy doing and try to deliver good results.”

Know your patients. When dermatologists who plan to open their own practice ask Dr. Ibrahimi what kind of laser they should buy, he typically responds by asking them to consider what procedures their patients are asking for. “Depending on where you are geographically and the economic profile of the community in which you practice, it can be a different answer,” Dr. Ibrahimi said. “If you practice in the Northeast and do a lot of medical dermatology, it might mean getting a vascular laser to treat rosacea. If you’re in Southern California, treating pigment might be a bigger concern than treating rosacea.” The annual ASDS Survey on Dermatologic Procedures provides a snapshot of trends and can be useful for decision-making, he said.

Know your practice. “Make sure you are capable of entering the aesthetics field,” he advised. “You cannot have a practice that runs like the DMV, with people waiting 30 to 40 minutes to be seen.” Proper training of staff is also key and representatives from device and injectable companies can provide advice and support. As for marketing, some dermatologists hire a public relations agency, but Dr. Ibrahimi finds that the best source of his referrals is word of mouth. “If I do a good job taking care of patients, they will send their friends and family over to me, but social media is also important,” he said. Taking quality before-and-after photos, and obtaining consent from patients to use them online in educational posts is a good approach, he noted.

Know your market. When Dr. Ibrahimi first opened his practice, offering laser hair removal was not a priority because so many other dermatologists and medical spas in his area were already providing it. With time, though, he added laser hair removal to his menu of treatment offerings because “I knew that if my patients weren’t getting that service from me, they would be getting it from somewhere else,” he said. “Initially it wasn’t important for me, but as my practice matured, I wanted to make sure that I was comprehensive.”

Start cautiously. Think safety first. “I tell people that starting a cosmetic practice is like baseball: don’t try to hit home runs,” Dr. Ibrahimi said. “Just aim for base hits and keep your patients happy. Make sure you deliver safe, good results.” This means knowing everything possible about the devices used in the office, because if the use of a laser is delegated to a staff member and a problem arises, “you have to know everything about how that device works so that you can troubleshoot,” he said. “A lot of problems that arise are from lack of intimacy with your device.”

Seek knowledge. Attend courses in cosmetic dermatology and read literature from journals like Dermatologic Surgery and Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, he advised. “People will see the success, but they won’t know how much hard work it takes to get there,” he said. “You have to develop your reputation to develop the kind of practice that you want.”

Understand the business of aesthetics. Most energy devices carry a steep price tag, and leasing or financing devices come with a monthly payment, he said. “Make sure that what you’re bringing in on that device is going to be sufficient to cover the monthly payment. With something like tissue microcoring, you don’t have to use that five times a day to cover that lease payment. But if you have a vascular laser, you probably need to be treating more than a couple patients per day to make that lease payment. If you can recover the amount the device costs in about a year, that’s going to be a good investment. Many devices come with consumables, so you have to remember that.”

Don’t be afraid to be unique/change directions. Becoming an early adopter of new technologies and procedures can make someone stand out. “Other providers feel more comfortable waiting to allow more data to come out about a new technology before they make a purchase,” he said. “But if you’re established and have a busy practice, that’s an opportunity that can draw people in.”

Have patience and realistic expectations. It’s smart to offer a variety of services, he said, such as medical or surgical dermatology in addition to cosmetic dermatology. “That’s going to help you through any kind of economic downturn,” he said. “Success depends on a lot of factors going right. Make sure you set short- and long-term goals.”

Dr. Ibrahimi disclosed that he is a member of the Advisory Board for Accure Acne, AbbVie, Cutera, Lutronic, Blueberry Therapeutics, Cytrellis, and Quthero. He also holds stock in many device and pharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO – When Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD, opened his own cosmetic dermatology practice in Stamford, Conn., in 2012, he sensed that he had his work cut out for him.

“I was a fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon who wanted to do aesthetics,” Dr. Ibrahimi, medical director of the Connecticut Skin Institute, recalled during the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “I was in a geographic area that was new to me. I didn’t know any referring doctors, but I started to network and tried to grow my practice.”

Someone once told him that the “three As” of being a medical specialist are “Available, Affable, and Ability,” so he applied that principle as he began to cultivate relationships with physicians in his geographic area. “I told my referring doctors, ‘If you’re kind enough to send me Mohs cases, I’ll help you out if there’s something you don’t like doing, whether it’s a nail biopsy or treating male genital warts,’” he said. “You want to make it easy for doctors to refer to you, but you also want to make their lives easier.”

Dr. Ibrahimi, who is also on the board of directors for the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery and the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, offered . They include:

Know yourself. Do what you love to do, not what you feel like you should do. “Whatever you’re doing in your practice, it should be something that you’re passionate about and excited about,” he said. “I do a mix of Mohs surgery and procedural aesthetic dermatology. Most of my practice is shaped toward energy-based devices and laser procedures. Pick the things that you enjoy doing and try to deliver good results.”

Know your patients. When dermatologists who plan to open their own practice ask Dr. Ibrahimi what kind of laser they should buy, he typically responds by asking them to consider what procedures their patients are asking for. “Depending on where you are geographically and the economic profile of the community in which you practice, it can be a different answer,” Dr. Ibrahimi said. “If you practice in the Northeast and do a lot of medical dermatology, it might mean getting a vascular laser to treat rosacea. If you’re in Southern California, treating pigment might be a bigger concern than treating rosacea.” The annual ASDS Survey on Dermatologic Procedures provides a snapshot of trends and can be useful for decision-making, he said.

Know your practice. “Make sure you are capable of entering the aesthetics field,” he advised. “You cannot have a practice that runs like the DMV, with people waiting 30 to 40 minutes to be seen.” Proper training of staff is also key and representatives from device and injectable companies can provide advice and support. As for marketing, some dermatologists hire a public relations agency, but Dr. Ibrahimi finds that the best source of his referrals is word of mouth. “If I do a good job taking care of patients, they will send their friends and family over to me, but social media is also important,” he said. Taking quality before-and-after photos, and obtaining consent from patients to use them online in educational posts is a good approach, he noted.

Know your market. When Dr. Ibrahimi first opened his practice, offering laser hair removal was not a priority because so many other dermatologists and medical spas in his area were already providing it. With time, though, he added laser hair removal to his menu of treatment offerings because “I knew that if my patients weren’t getting that service from me, they would be getting it from somewhere else,” he said. “Initially it wasn’t important for me, but as my practice matured, I wanted to make sure that I was comprehensive.”

Start cautiously. Think safety first. “I tell people that starting a cosmetic practice is like baseball: don’t try to hit home runs,” Dr. Ibrahimi said. “Just aim for base hits and keep your patients happy. Make sure you deliver safe, good results.” This means knowing everything possible about the devices used in the office, because if the use of a laser is delegated to a staff member and a problem arises, “you have to know everything about how that device works so that you can troubleshoot,” he said. “A lot of problems that arise are from lack of intimacy with your device.”

Seek knowledge. Attend courses in cosmetic dermatology and read literature from journals like Dermatologic Surgery and Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, he advised. “People will see the success, but they won’t know how much hard work it takes to get there,” he said. “You have to develop your reputation to develop the kind of practice that you want.”

Understand the business of aesthetics. Most energy devices carry a steep price tag, and leasing or financing devices come with a monthly payment, he said. “Make sure that what you’re bringing in on that device is going to be sufficient to cover the monthly payment. With something like tissue microcoring, you don’t have to use that five times a day to cover that lease payment. But if you have a vascular laser, you probably need to be treating more than a couple patients per day to make that lease payment. If you can recover the amount the device costs in about a year, that’s going to be a good investment. Many devices come with consumables, so you have to remember that.”

Don’t be afraid to be unique/change directions. Becoming an early adopter of new technologies and procedures can make someone stand out. “Other providers feel more comfortable waiting to allow more data to come out about a new technology before they make a purchase,” he said. “But if you’re established and have a busy practice, that’s an opportunity that can draw people in.”

Have patience and realistic expectations. It’s smart to offer a variety of services, he said, such as medical or surgical dermatology in addition to cosmetic dermatology. “That’s going to help you through any kind of economic downturn,” he said. “Success depends on a lot of factors going right. Make sure you set short- and long-term goals.”

Dr. Ibrahimi disclosed that he is a member of the Advisory Board for Accure Acne, AbbVie, Cutera, Lutronic, Blueberry Therapeutics, Cytrellis, and Quthero. He also holds stock in many device and pharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO – When Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD, opened his own cosmetic dermatology practice in Stamford, Conn., in 2012, he sensed that he had his work cut out for him.

“I was a fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon who wanted to do aesthetics,” Dr. Ibrahimi, medical director of the Connecticut Skin Institute, recalled during the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “I was in a geographic area that was new to me. I didn’t know any referring doctors, but I started to network and tried to grow my practice.”

Someone once told him that the “three As” of being a medical specialist are “Available, Affable, and Ability,” so he applied that principle as he began to cultivate relationships with physicians in his geographic area. “I told my referring doctors, ‘If you’re kind enough to send me Mohs cases, I’ll help you out if there’s something you don’t like doing, whether it’s a nail biopsy or treating male genital warts,’” he said. “You want to make it easy for doctors to refer to you, but you also want to make their lives easier.”

Dr. Ibrahimi, who is also on the board of directors for the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery and the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, offered . They include:

Know yourself. Do what you love to do, not what you feel like you should do. “Whatever you’re doing in your practice, it should be something that you’re passionate about and excited about,” he said. “I do a mix of Mohs surgery and procedural aesthetic dermatology. Most of my practice is shaped toward energy-based devices and laser procedures. Pick the things that you enjoy doing and try to deliver good results.”

Know your patients. When dermatologists who plan to open their own practice ask Dr. Ibrahimi what kind of laser they should buy, he typically responds by asking them to consider what procedures their patients are asking for. “Depending on where you are geographically and the economic profile of the community in which you practice, it can be a different answer,” Dr. Ibrahimi said. “If you practice in the Northeast and do a lot of medical dermatology, it might mean getting a vascular laser to treat rosacea. If you’re in Southern California, treating pigment might be a bigger concern than treating rosacea.” The annual ASDS Survey on Dermatologic Procedures provides a snapshot of trends and can be useful for decision-making, he said.

Know your practice. “Make sure you are capable of entering the aesthetics field,” he advised. “You cannot have a practice that runs like the DMV, with people waiting 30 to 40 minutes to be seen.” Proper training of staff is also key and representatives from device and injectable companies can provide advice and support. As for marketing, some dermatologists hire a public relations agency, but Dr. Ibrahimi finds that the best source of his referrals is word of mouth. “If I do a good job taking care of patients, they will send their friends and family over to me, but social media is also important,” he said. Taking quality before-and-after photos, and obtaining consent from patients to use them online in educational posts is a good approach, he noted.

Know your market. When Dr. Ibrahimi first opened his practice, offering laser hair removal was not a priority because so many other dermatologists and medical spas in his area were already providing it. With time, though, he added laser hair removal to his menu of treatment offerings because “I knew that if my patients weren’t getting that service from me, they would be getting it from somewhere else,” he said. “Initially it wasn’t important for me, but as my practice matured, I wanted to make sure that I was comprehensive.”

Start cautiously. Think safety first. “I tell people that starting a cosmetic practice is like baseball: don’t try to hit home runs,” Dr. Ibrahimi said. “Just aim for base hits and keep your patients happy. Make sure you deliver safe, good results.” This means knowing everything possible about the devices used in the office, because if the use of a laser is delegated to a staff member and a problem arises, “you have to know everything about how that device works so that you can troubleshoot,” he said. “A lot of problems that arise are from lack of intimacy with your device.”

Seek knowledge. Attend courses in cosmetic dermatology and read literature from journals like Dermatologic Surgery and Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, he advised. “People will see the success, but they won’t know how much hard work it takes to get there,” he said. “You have to develop your reputation to develop the kind of practice that you want.”

Understand the business of aesthetics. Most energy devices carry a steep price tag, and leasing or financing devices come with a monthly payment, he said. “Make sure that what you’re bringing in on that device is going to be sufficient to cover the monthly payment. With something like tissue microcoring, you don’t have to use that five times a day to cover that lease payment. But if you have a vascular laser, you probably need to be treating more than a couple patients per day to make that lease payment. If you can recover the amount the device costs in about a year, that’s going to be a good investment. Many devices come with consumables, so you have to remember that.”

Don’t be afraid to be unique/change directions. Becoming an early adopter of new technologies and procedures can make someone stand out. “Other providers feel more comfortable waiting to allow more data to come out about a new technology before they make a purchase,” he said. “But if you’re established and have a busy practice, that’s an opportunity that can draw people in.”

Have patience and realistic expectations. It’s smart to offer a variety of services, he said, such as medical or surgical dermatology in addition to cosmetic dermatology. “That’s going to help you through any kind of economic downturn,” he said. “Success depends on a lot of factors going right. Make sure you set short- and long-term goals.”

Dr. Ibrahimi disclosed that he is a member of the Advisory Board for Accure Acne, AbbVie, Cutera, Lutronic, Blueberry Therapeutics, Cytrellis, and Quthero. He also holds stock in many device and pharmaceutical companies.

AT MOAS 2022

For optimal results, fractional RF microneedling requires multiple treatments

SAN DIEGO – , according to Catherine M. DiGiorgio, MD.

Most core fractional RF microneedling indications – acne scars, rhytides, skin tightening – require multiple treatments, Dr. DiGiorgio, a laser and cosmetic dermatologist who practices in Boston, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “That’s an important expectation to set for your patients,” she said. “You also want to select depth and density parameters based on pathophysiology of the condition being treated, and combination treatments always provide the best results. So, whether you’re treating someone for acne scars or rhytides, you want to treat them for their erythema or their dermatoheliosis. The same goes for skin tightening procedures.”

Many nonpolar and bipolar devices are available for use, most of which feature adjustable depths and energies. Tips can be insulated or noninsulated. Generally, the insulated tips are safer for darker skin types because the energy is not delivered to the epidermis. However, the Sylfirm X device from Benev has a noninsulated tip but is safe for all skin types because the energy is delivered from the tip of a conically shaped needle and moves proximally but never reaches the epidermis, said Dr. DiGiorgio. Continuous wave mode is used for tightening and wrinkles while pulsed mode is used for pigment and vascular lesions.

Treatment with most fractional RF microneedling devices is painful so topical anesthesia is required. Dr. DiGiorgio typically uses topical 23% lidocaine and 7% tetracaine. The downtime varies depending on which device is being used. For anesthesia prior to aggressive fractional microneedle RF treatments such as with the Profound RF for skin tightening, Dr. DiGiorgio typically uses a Mesoram needle with a cocktail of 30 ccs of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine, 15 ccs of bicarbonate, and 5 ccs of saline. “More aggressive RF procedures can result in bruising for 7 to 8 days,” she said. “It can be covered with makeup. Wearing masks during the COVID-19 pandemic have also helped patients cover the bruising.”

In her clinical experience, the ideal patient for skin tightening with fractional RF microneedling has mild to moderate skin laxity that does not require surgical intervention. “Nonsurgical treatments provide nonsurgical results,” she said. “If a patient comes in holding their skin back and there is a lot of laxity, this is not going to be the right treatment for that person.”

Dr. DiGiorgio offers fractional RF microneedling in the context of a full-face rejuvenation. She begins by addressing volume loss and dynamic rhytides with injectables prior to skin tightening devices such as fractional RF microneedling or ultrasound-based tightening devices such as Sofwave or Ulthera (also referred to as Ultherapy). “You can add an ablative fractional to target deeper rhytides or pigment-targeting laser to address their dermatoheliosis, which will enhance their results,” she said. “Finally, you can follow up with a thread lift two weeks after the microneedle RF to achieve greater skin tightening. If the thread lift is performed before the microneedle RF, you want to wait about 2 months because the microneedle RF can damage the thread.”

Despite the limited efficacy for tissue tightening with fractional RF microneedling, “it’s a good alternative to lasers, especially for darker skin types,” she said. “Combination treatments will always enhance your results.”

Dr. DiGiorgio disclosed that she is a member of the advisory board for Quthero. She is also a consultant for Revelle and has received equipment from Acclaro.

SAN DIEGO – , according to Catherine M. DiGiorgio, MD.

Most core fractional RF microneedling indications – acne scars, rhytides, skin tightening – require multiple treatments, Dr. DiGiorgio, a laser and cosmetic dermatologist who practices in Boston, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “That’s an important expectation to set for your patients,” she said. “You also want to select depth and density parameters based on pathophysiology of the condition being treated, and combination treatments always provide the best results. So, whether you’re treating someone for acne scars or rhytides, you want to treat them for their erythema or their dermatoheliosis. The same goes for skin tightening procedures.”

Many nonpolar and bipolar devices are available for use, most of which feature adjustable depths and energies. Tips can be insulated or noninsulated. Generally, the insulated tips are safer for darker skin types because the energy is not delivered to the epidermis. However, the Sylfirm X device from Benev has a noninsulated tip but is safe for all skin types because the energy is delivered from the tip of a conically shaped needle and moves proximally but never reaches the epidermis, said Dr. DiGiorgio. Continuous wave mode is used for tightening and wrinkles while pulsed mode is used for pigment and vascular lesions.

Treatment with most fractional RF microneedling devices is painful so topical anesthesia is required. Dr. DiGiorgio typically uses topical 23% lidocaine and 7% tetracaine. The downtime varies depending on which device is being used. For anesthesia prior to aggressive fractional microneedle RF treatments such as with the Profound RF for skin tightening, Dr. DiGiorgio typically uses a Mesoram needle with a cocktail of 30 ccs of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine, 15 ccs of bicarbonate, and 5 ccs of saline. “More aggressive RF procedures can result in bruising for 7 to 8 days,” she said. “It can be covered with makeup. Wearing masks during the COVID-19 pandemic have also helped patients cover the bruising.”

In her clinical experience, the ideal patient for skin tightening with fractional RF microneedling has mild to moderate skin laxity that does not require surgical intervention. “Nonsurgical treatments provide nonsurgical results,” she said. “If a patient comes in holding their skin back and there is a lot of laxity, this is not going to be the right treatment for that person.”

Dr. DiGiorgio offers fractional RF microneedling in the context of a full-face rejuvenation. She begins by addressing volume loss and dynamic rhytides with injectables prior to skin tightening devices such as fractional RF microneedling or ultrasound-based tightening devices such as Sofwave or Ulthera (also referred to as Ultherapy). “You can add an ablative fractional to target deeper rhytides or pigment-targeting laser to address their dermatoheliosis, which will enhance their results,” she said. “Finally, you can follow up with a thread lift two weeks after the microneedle RF to achieve greater skin tightening. If the thread lift is performed before the microneedle RF, you want to wait about 2 months because the microneedle RF can damage the thread.”

Despite the limited efficacy for tissue tightening with fractional RF microneedling, “it’s a good alternative to lasers, especially for darker skin types,” she said. “Combination treatments will always enhance your results.”

Dr. DiGiorgio disclosed that she is a member of the advisory board for Quthero. She is also a consultant for Revelle and has received equipment from Acclaro.

SAN DIEGO – , according to Catherine M. DiGiorgio, MD.

Most core fractional RF microneedling indications – acne scars, rhytides, skin tightening – require multiple treatments, Dr. DiGiorgio, a laser and cosmetic dermatologist who practices in Boston, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “That’s an important expectation to set for your patients,” she said. “You also want to select depth and density parameters based on pathophysiology of the condition being treated, and combination treatments always provide the best results. So, whether you’re treating someone for acne scars or rhytides, you want to treat them for their erythema or their dermatoheliosis. The same goes for skin tightening procedures.”

Many nonpolar and bipolar devices are available for use, most of which feature adjustable depths and energies. Tips can be insulated or noninsulated. Generally, the insulated tips are safer for darker skin types because the energy is not delivered to the epidermis. However, the Sylfirm X device from Benev has a noninsulated tip but is safe for all skin types because the energy is delivered from the tip of a conically shaped needle and moves proximally but never reaches the epidermis, said Dr. DiGiorgio. Continuous wave mode is used for tightening and wrinkles while pulsed mode is used for pigment and vascular lesions.

Treatment with most fractional RF microneedling devices is painful so topical anesthesia is required. Dr. DiGiorgio typically uses topical 23% lidocaine and 7% tetracaine. The downtime varies depending on which device is being used. For anesthesia prior to aggressive fractional microneedle RF treatments such as with the Profound RF for skin tightening, Dr. DiGiorgio typically uses a Mesoram needle with a cocktail of 30 ccs of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine, 15 ccs of bicarbonate, and 5 ccs of saline. “More aggressive RF procedures can result in bruising for 7 to 8 days,” she said. “It can be covered with makeup. Wearing masks during the COVID-19 pandemic have also helped patients cover the bruising.”

In her clinical experience, the ideal patient for skin tightening with fractional RF microneedling has mild to moderate skin laxity that does not require surgical intervention. “Nonsurgical treatments provide nonsurgical results,” she said. “If a patient comes in holding their skin back and there is a lot of laxity, this is not going to be the right treatment for that person.”

Dr. DiGiorgio offers fractional RF microneedling in the context of a full-face rejuvenation. She begins by addressing volume loss and dynamic rhytides with injectables prior to skin tightening devices such as fractional RF microneedling or ultrasound-based tightening devices such as Sofwave or Ulthera (also referred to as Ultherapy). “You can add an ablative fractional to target deeper rhytides or pigment-targeting laser to address their dermatoheliosis, which will enhance their results,” she said. “Finally, you can follow up with a thread lift two weeks after the microneedle RF to achieve greater skin tightening. If the thread lift is performed before the microneedle RF, you want to wait about 2 months because the microneedle RF can damage the thread.”

Despite the limited efficacy for tissue tightening with fractional RF microneedling, “it’s a good alternative to lasers, especially for darker skin types,” she said. “Combination treatments will always enhance your results.”

Dr. DiGiorgio disclosed that she is a member of the advisory board for Quthero. She is also a consultant for Revelle and has received equipment from Acclaro.

AT MOAS 2022

Hair supplements

in JAMA Dermatology in November 2022.

Drake and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of nutritional supplements for treating hair loss. In a systematic database review from inception to Oct. 20, 2021, they evaluated and compiled the findings of all dietary and nutritional interventions for treatment of hair loss among individuals without a known baseline nutritional deficiency. Thirty articles were included, including 17 randomized clinical trials, 11 clinical trials, and 2 case series.

They found the highest-quality evidence showing the most potential benefit were for 12 of the 20 nutritional interventions in their review: Pumpkin seed oil capsules, omega-3 and -6 combined with antioxidants, tocotrienol, Pantogar, capsaicin and isoflavone, Viviscal (multiple formulations), Nourkrin, Nutrafol, apple nutraceutical, Lambdapil, total glucosides of paeony and compound glycyrrhizin tablets, and zinc. Vitamin D3, kimchi and cheonggukjang, and Forti5 had lower-quality evidence for disease course improvement. Adverse effects associated with the supplements were described as mild and rare.

In practice, for patients with nonscarring alopecia, I typically check screening labs for hair loss, in addition to the clinical exam, before starting treatment (including supplements), as addressing the underlying reason, if found, is always paramount. These labs are best performed when the patient is not taking biotin, as biotin has been shown numerous times to potentially be associated with endocrine lab abnormalities, most commonly thyroid-stimulating hormone, especially at higher doses, as well as troponin levels. Some over-the-counter hair supplements will contain much higher doses than the recommended 30 micrograms per day.

Separately, if ferritin levels are within normal range, but below 50 mcg/L, supplementation with Slow Fe or another slow-release iron supplement may also result in improved hair growth. Ferritin levels are typically rechecked 6 months after supplementation to see if levels of 50 mcg/L or above have been achieved.

Another point to consider before beginning supplementation is to educate patients about potential effects of supplementation, including increased hair growth in other areas besides the scalp. For some patients who are self-conscious about potential hirsutism, this could be an issue, whereas for others, this risk does not outweigh the benefit. Unwanted hair growth, should it occur, may also be addressed with hair removal methods including shaving, waxing, plucking, threading, depilatories, prescription eflornithine cream (Vaniqa), or laser hair removal if desired.

Our armamentarium for treating hair loss includes: addressing underlying systemic causes; topical treatments including topical minoxidil; oral supplements; platelet-rich plasma injections; prescription oral medications including finasteride in men or postmenopausal women or off-label oral minoxidil; and hair transplant surgery if warranted. Having this thorough review of the most common hair supplements currently available is extremely helpful and valuable in our specialty.

Dr. Wesley and Lily Talakoub, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Write to them at [email protected]. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. She had no relevant disclosures.

in JAMA Dermatology in November 2022.

Drake and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of nutritional supplements for treating hair loss. In a systematic database review from inception to Oct. 20, 2021, they evaluated and compiled the findings of all dietary and nutritional interventions for treatment of hair loss among individuals without a known baseline nutritional deficiency. Thirty articles were included, including 17 randomized clinical trials, 11 clinical trials, and 2 case series.

They found the highest-quality evidence showing the most potential benefit were for 12 of the 20 nutritional interventions in their review: Pumpkin seed oil capsules, omega-3 and -6 combined with antioxidants, tocotrienol, Pantogar, capsaicin and isoflavone, Viviscal (multiple formulations), Nourkrin, Nutrafol, apple nutraceutical, Lambdapil, total glucosides of paeony and compound glycyrrhizin tablets, and zinc. Vitamin D3, kimchi and cheonggukjang, and Forti5 had lower-quality evidence for disease course improvement. Adverse effects associated with the supplements were described as mild and rare.

In practice, for patients with nonscarring alopecia, I typically check screening labs for hair loss, in addition to the clinical exam, before starting treatment (including supplements), as addressing the underlying reason, if found, is always paramount. These labs are best performed when the patient is not taking biotin, as biotin has been shown numerous times to potentially be associated with endocrine lab abnormalities, most commonly thyroid-stimulating hormone, especially at higher doses, as well as troponin levels. Some over-the-counter hair supplements will contain much higher doses than the recommended 30 micrograms per day.

Separately, if ferritin levels are within normal range, but below 50 mcg/L, supplementation with Slow Fe or another slow-release iron supplement may also result in improved hair growth. Ferritin levels are typically rechecked 6 months after supplementation to see if levels of 50 mcg/L or above have been achieved.

Another point to consider before beginning supplementation is to educate patients about potential effects of supplementation, including increased hair growth in other areas besides the scalp. For some patients who are self-conscious about potential hirsutism, this could be an issue, whereas for others, this risk does not outweigh the benefit. Unwanted hair growth, should it occur, may also be addressed with hair removal methods including shaving, waxing, plucking, threading, depilatories, prescription eflornithine cream (Vaniqa), or laser hair removal if desired.

Our armamentarium for treating hair loss includes: addressing underlying systemic causes; topical treatments including topical minoxidil; oral supplements; platelet-rich plasma injections; prescription oral medications including finasteride in men or postmenopausal women or off-label oral minoxidil; and hair transplant surgery if warranted. Having this thorough review of the most common hair supplements currently available is extremely helpful and valuable in our specialty.

Dr. Wesley and Lily Talakoub, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Write to them at [email protected]. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. She had no relevant disclosures.

in JAMA Dermatology in November 2022.

Drake and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of nutritional supplements for treating hair loss. In a systematic database review from inception to Oct. 20, 2021, they evaluated and compiled the findings of all dietary and nutritional interventions for treatment of hair loss among individuals without a known baseline nutritional deficiency. Thirty articles were included, including 17 randomized clinical trials, 11 clinical trials, and 2 case series.

They found the highest-quality evidence showing the most potential benefit were for 12 of the 20 nutritional interventions in their review: Pumpkin seed oil capsules, omega-3 and -6 combined with antioxidants, tocotrienol, Pantogar, capsaicin and isoflavone, Viviscal (multiple formulations), Nourkrin, Nutrafol, apple nutraceutical, Lambdapil, total glucosides of paeony and compound glycyrrhizin tablets, and zinc. Vitamin D3, kimchi and cheonggukjang, and Forti5 had lower-quality evidence for disease course improvement. Adverse effects associated with the supplements were described as mild and rare.

In practice, for patients with nonscarring alopecia, I typically check screening labs for hair loss, in addition to the clinical exam, before starting treatment (including supplements), as addressing the underlying reason, if found, is always paramount. These labs are best performed when the patient is not taking biotin, as biotin has been shown numerous times to potentially be associated with endocrine lab abnormalities, most commonly thyroid-stimulating hormone, especially at higher doses, as well as troponin levels. Some over-the-counter hair supplements will contain much higher doses than the recommended 30 micrograms per day.

Separately, if ferritin levels are within normal range, but below 50 mcg/L, supplementation with Slow Fe or another slow-release iron supplement may also result in improved hair growth. Ferritin levels are typically rechecked 6 months after supplementation to see if levels of 50 mcg/L or above have been achieved.

Another point to consider before beginning supplementation is to educate patients about potential effects of supplementation, including increased hair growth in other areas besides the scalp. For some patients who are self-conscious about potential hirsutism, this could be an issue, whereas for others, this risk does not outweigh the benefit. Unwanted hair growth, should it occur, may also be addressed with hair removal methods including shaving, waxing, plucking, threading, depilatories, prescription eflornithine cream (Vaniqa), or laser hair removal if desired.

Our armamentarium for treating hair loss includes: addressing underlying systemic causes; topical treatments including topical minoxidil; oral supplements; platelet-rich plasma injections; prescription oral medications including finasteride in men or postmenopausal women or off-label oral minoxidil; and hair transplant surgery if warranted. Having this thorough review of the most common hair supplements currently available is extremely helpful and valuable in our specialty.

Dr. Wesley and Lily Talakoub, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Write to them at [email protected]. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. She had no relevant disclosures.

‘Dr. Pimple Popper’ offers tips for building a social media presence

SAN DIEGO – In the fall of 2014, Sandra Lee, MD, posted a blackhead extraction video on her Instagram account, a decision that changed her professional life forever.

“I got these crazy comments,” Dr. Lee, a dermatologist who practices in Upland, Calif., recalled at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “Either people loved it – they were obsessed – or they thought it was the most disgusting thing they’d ever seen. It created a strong reaction. Either way, they shared it with their friends.”

Soon after she started posting videos, she discovered Reddit, which has a subreddit for “popping addicts” and the “pop-curious.” “I thought, ‘These videos are so amateur. They’re culling them from the Internet. Or, they’re pinning down their son at the beach and trying to squeeze out a blackhead,’ ” Dr. Lee said. “I thought, ‘I could give them pristine videos,’ ” and that is exactly what she did.

Turning to YouTube as a platform, she began to post videos showing everything from Mohs surgery and Botox injections to keloid removals and ear lobe repair surgeries. With this, . She also grew 16.2 million subscribers on TikTok, 4.5 million followers on Instagram, 2.9 million on Facebook, and 136,700 on Twitter.

About 80% of her followers are women who range between 18 and 40 years of age. “I have over 5 billion views on YouTube, which is mind-blowing,” she said. “That tells you something about the content. It’s not something people watch once. They watch it over and over again.” These include videos compiled as a “bedtime story.”

Dr. Lee offered the following pearls of advice for dermatologists looking to build and maintain a presence on social media:

Use it to showcase what makes you unique. Post what you do on social media, and people will find you. “It’s an opportunity to freely advertise,” Dr. Lee said. “I’m super nitpicky about posting good before-and-after photos. You can also show off how nice and warm and inviting your office is. People come to see me because they know my voice. They know how I interact with patients. That is reason for them enough to travel from far away to see me. It doesn’t mean that I’m the person who is best at treating whatever condition they have.”

Make it interesting. “I say that the special sauce is entertainment and education,” said Dr. Lee, who is in the fifth season of “Dr. Pimple Popper,” her TV show that airs internationally. “The only way you can draw people in is by entertaining them, catching their interest. But I try to trick them into educating them. Five-year-old kids come up to me now and know what a lipoma is. I’m proud of that.”

Be authentic. You may be using social media to promote your dermatology practice, but it’s important for followers to get a glimpse of your nonwork personality as well. Maybe that means posting a photo of yourself at a concert, baseball game, or dinner with family and friends. “Show that you have a sense of humor, because you want them to like you,” Dr. Lee added. “That’s why someone follows you, because they want to be your friend. They enjoy spending time with you on the Internet. It’s like gambling. In order to win, you have to play. So, you have to post.”

Avoid hot-button topics. “I don’t post about my kids, and I try to choose sponsorships wisely,” she said. “I do very few branding deals. Be careful about your brand and how you present yourself. Present yourself in an authentic way, but not in a way that hurts yourself or the dermatology profession.”

Be mindful of the time investment. “It’s like running a whole other business,” Dr. Lee said. “There are also trolls out there, so you have to have thick skin.”

Don’t sweat it if you don’t want to engage. “Not everybody wants to do it, and not everybody will be good at it, but that’s okay,” she said.

Dr. Lee reported having no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – In the fall of 2014, Sandra Lee, MD, posted a blackhead extraction video on her Instagram account, a decision that changed her professional life forever.

“I got these crazy comments,” Dr. Lee, a dermatologist who practices in Upland, Calif., recalled at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “Either people loved it – they were obsessed – or they thought it was the most disgusting thing they’d ever seen. It created a strong reaction. Either way, they shared it with their friends.”

Soon after she started posting videos, she discovered Reddit, which has a subreddit for “popping addicts” and the “pop-curious.” “I thought, ‘These videos are so amateur. They’re culling them from the Internet. Or, they’re pinning down their son at the beach and trying to squeeze out a blackhead,’ ” Dr. Lee said. “I thought, ‘I could give them pristine videos,’ ” and that is exactly what she did.

Turning to YouTube as a platform, she began to post videos showing everything from Mohs surgery and Botox injections to keloid removals and ear lobe repair surgeries. With this, . She also grew 16.2 million subscribers on TikTok, 4.5 million followers on Instagram, 2.9 million on Facebook, and 136,700 on Twitter.

About 80% of her followers are women who range between 18 and 40 years of age. “I have over 5 billion views on YouTube, which is mind-blowing,” she said. “That tells you something about the content. It’s not something people watch once. They watch it over and over again.” These include videos compiled as a “bedtime story.”

Dr. Lee offered the following pearls of advice for dermatologists looking to build and maintain a presence on social media:

Use it to showcase what makes you unique. Post what you do on social media, and people will find you. “It’s an opportunity to freely advertise,” Dr. Lee said. “I’m super nitpicky about posting good before-and-after photos. You can also show off how nice and warm and inviting your office is. People come to see me because they know my voice. They know how I interact with patients. That is reason for them enough to travel from far away to see me. It doesn’t mean that I’m the person who is best at treating whatever condition they have.”

Make it interesting. “I say that the special sauce is entertainment and education,” said Dr. Lee, who is in the fifth season of “Dr. Pimple Popper,” her TV show that airs internationally. “The only way you can draw people in is by entertaining them, catching their interest. But I try to trick them into educating them. Five-year-old kids come up to me now and know what a lipoma is. I’m proud of that.”

Be authentic. You may be using social media to promote your dermatology practice, but it’s important for followers to get a glimpse of your nonwork personality as well. Maybe that means posting a photo of yourself at a concert, baseball game, or dinner with family and friends. “Show that you have a sense of humor, because you want them to like you,” Dr. Lee added. “That’s why someone follows you, because they want to be your friend. They enjoy spending time with you on the Internet. It’s like gambling. In order to win, you have to play. So, you have to post.”

Avoid hot-button topics. “I don’t post about my kids, and I try to choose sponsorships wisely,” she said. “I do very few branding deals. Be careful about your brand and how you present yourself. Present yourself in an authentic way, but not in a way that hurts yourself or the dermatology profession.”

Be mindful of the time investment. “It’s like running a whole other business,” Dr. Lee said. “There are also trolls out there, so you have to have thick skin.”

Don’t sweat it if you don’t want to engage. “Not everybody wants to do it, and not everybody will be good at it, but that’s okay,” she said.

Dr. Lee reported having no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – In the fall of 2014, Sandra Lee, MD, posted a blackhead extraction video on her Instagram account, a decision that changed her professional life forever.

“I got these crazy comments,” Dr. Lee, a dermatologist who practices in Upland, Calif., recalled at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “Either people loved it – they were obsessed – or they thought it was the most disgusting thing they’d ever seen. It created a strong reaction. Either way, they shared it with their friends.”

Soon after she started posting videos, she discovered Reddit, which has a subreddit for “popping addicts” and the “pop-curious.” “I thought, ‘These videos are so amateur. They’re culling them from the Internet. Or, they’re pinning down their son at the beach and trying to squeeze out a blackhead,’ ” Dr. Lee said. “I thought, ‘I could give them pristine videos,’ ” and that is exactly what she did.

Turning to YouTube as a platform, she began to post videos showing everything from Mohs surgery and Botox injections to keloid removals and ear lobe repair surgeries. With this, . She also grew 16.2 million subscribers on TikTok, 4.5 million followers on Instagram, 2.9 million on Facebook, and 136,700 on Twitter.

About 80% of her followers are women who range between 18 and 40 years of age. “I have over 5 billion views on YouTube, which is mind-blowing,” she said. “That tells you something about the content. It’s not something people watch once. They watch it over and over again.” These include videos compiled as a “bedtime story.”

Dr. Lee offered the following pearls of advice for dermatologists looking to build and maintain a presence on social media:

Use it to showcase what makes you unique. Post what you do on social media, and people will find you. “It’s an opportunity to freely advertise,” Dr. Lee said. “I’m super nitpicky about posting good before-and-after photos. You can also show off how nice and warm and inviting your office is. People come to see me because they know my voice. They know how I interact with patients. That is reason for them enough to travel from far away to see me. It doesn’t mean that I’m the person who is best at treating whatever condition they have.”

Make it interesting. “I say that the special sauce is entertainment and education,” said Dr. Lee, who is in the fifth season of “Dr. Pimple Popper,” her TV show that airs internationally. “The only way you can draw people in is by entertaining them, catching their interest. But I try to trick them into educating them. Five-year-old kids come up to me now and know what a lipoma is. I’m proud of that.”

Be authentic. You may be using social media to promote your dermatology practice, but it’s important for followers to get a glimpse of your nonwork personality as well. Maybe that means posting a photo of yourself at a concert, baseball game, or dinner with family and friends. “Show that you have a sense of humor, because you want them to like you,” Dr. Lee added. “That’s why someone follows you, because they want to be your friend. They enjoy spending time with you on the Internet. It’s like gambling. In order to win, you have to play. So, you have to post.”

Avoid hot-button topics. “I don’t post about my kids, and I try to choose sponsorships wisely,” she said. “I do very few branding deals. Be careful about your brand and how you present yourself. Present yourself in an authentic way, but not in a way that hurts yourself or the dermatology profession.”

Be mindful of the time investment. “It’s like running a whole other business,” Dr. Lee said. “There are also trolls out there, so you have to have thick skin.”

Don’t sweat it if you don’t want to engage. “Not everybody wants to do it, and not everybody will be good at it, but that’s okay,” she said.

Dr. Lee reported having no relevant disclosures.

AT MOAS 2022

Experts dispel incorrect dogmas in aesthetic medicine

At least once a week,

Those images may help Dr. Stankiewicz understand patient preferences in terms of lip size and proportion, but she points out that shape is unique to each person. “I tell them: ‘All we can do is enhance that lip shape with filler. We can’t give you somebody else’s lip shape with an injection of filler.’ ”

During a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy, she and Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD, dispelled this and other false dogmas that they hear from some clinicians who practice aesthetic medicine and the patients who see them.

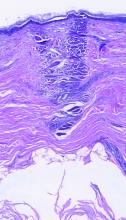

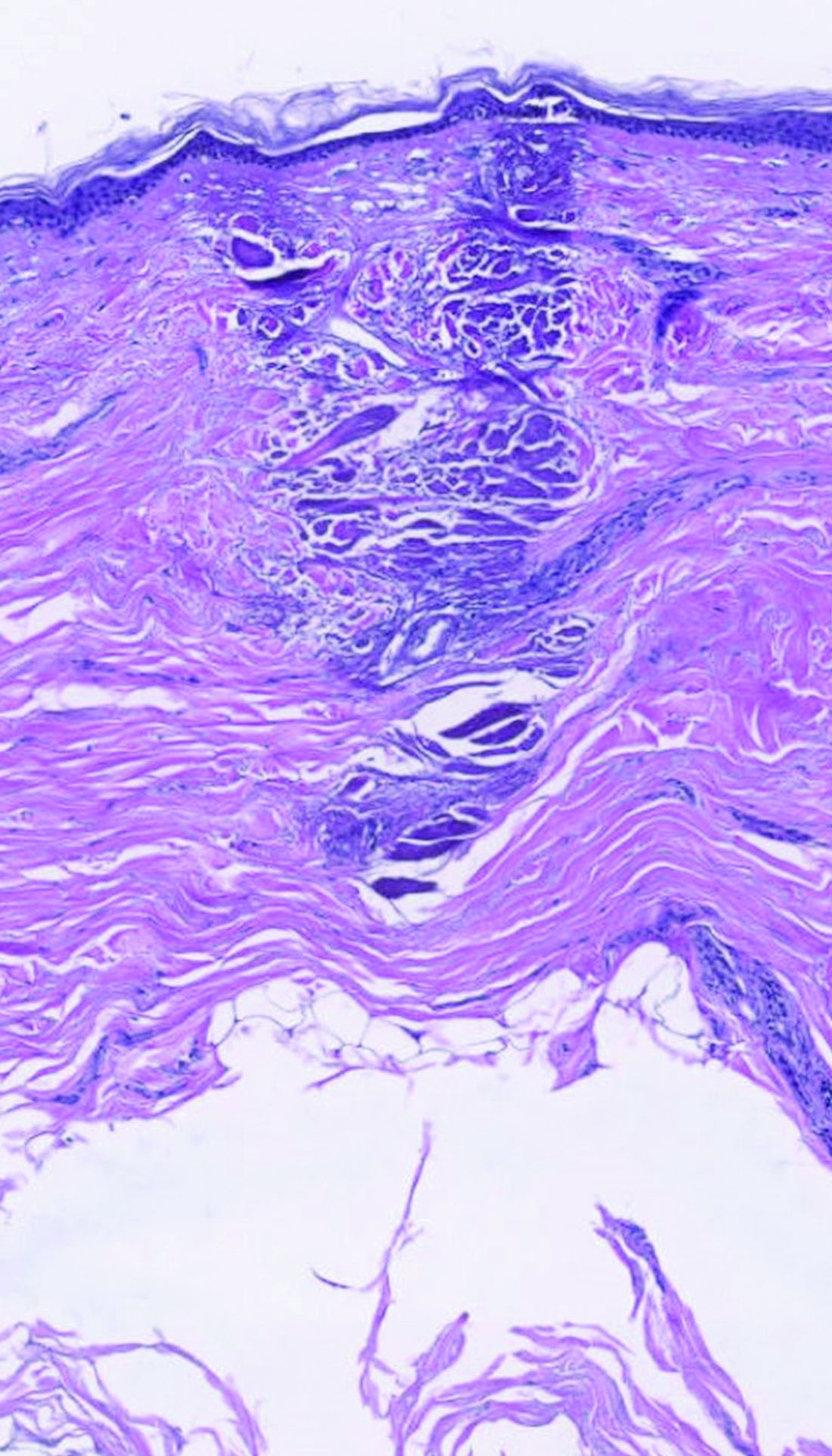

Wait 1 year before treating traumatic and surgical scars with vascular and fractional CO2 lasers. “I don’t think this is controversial anymore, because there is a boatload of data, which has shown that early treatment can prevent hypertrophic scarring and promote scar maturation,” said Dr. Stankiewicz, who practices dermatology in Park City, Utah. “Histology has also shown more organized dermal collagen from early treatment. Of course, there will be situations where you may want to hold off, like doing an ablative fractional [laser treatment] over the scar of a joint replacement ... where you may risk infection.” In her clinic, she routinely treats scars on the same day as suture removal, “as long as the healing looks appropriate.”

Dr. Ibrahimi, a dermatologist and medical director of the Connecticut Skin Institute, Stamford, also jumps on treating scars early. For a patient with postacne erythema, for example, he will use a pulsed-dye laser, which he believes will prevent scars from becoming atrophic.

Used equipment is a better investment than new equipment. While purchasing used laser and light devices can save money, especially when starting out, be wary of potential pitfalls, including the fact that many devices have disposable tips. “If your laser isn’t certified or you’re not the authorized owner of the device, you won’t be able to buy the disposables,” Dr. Stankiewicz noted. “So, before you buy a used device, ensure that you can buy them.”

Also, consider the cost of service if the device breaks down, she advised. Some lasers are complicated to service and others have codes set by the manufacturer so that only contracted engineers can work on them. “Otherwise, third-party engineers and service providers have to figure out how to crack the code to get into the machine,” she said. “If you’re in the situation where you have to ask the manufacturer to service your device, you have to pay a lot of money to recertify your device. Then you’ve lost all the savings you thought you made by buying a used machine.” She prefers to negotiate a good deal on a new device. “Often, a very good deal on a new device can rival the offer of a used one.”

Dr. Ibrahimi recalled buying a used fractional laser that came with a 30-day guarantee, but it stopped working around day 45. “I didn’t have much recourse there,” he said during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “You can’t go back to the company [for repair] unless you pay a recertification fee.”

Avoid exercise after Botox treatment. Although inverted yoga poses and lying down should be avoided for several hours after receiving Botox, there are no other limits to other forms of exercise post treatment, Dr. Stankiewicz said. If she suspects that a patient will develop bruising on one or more injection sites, she treats the areas with a laser. “Doing this on the same day as Botox treatment doesn’t always stop or treat bruising, many times it does.”

Another myth she hears is that it is not safe to fly in an airplane after Botox treatment. “That recommendation comes from the fact that the atmospheric pressure is lower in an airplane, so we worry about the risk of Botox spread,” Dr. Stankiewicz said. “But I practice at 7,000 feet above sea level, which is the same atmospheric pressure as that in an airplane,” she added, noting Botox is administered throughout the day in her practice and she does not see increased complications or worry about spread.

Clinician self-treatment is okay. In the opinion of Dr. Stankiewicz, aesthetic clinicians who treat themselves “have a fool for a patient.” She added: “Although no one is going to blame you and may not even know if you give yourself a little Botox touch-up at home, glorifying self-treatment on social media must stop. It’s dangerous and it can be ineffective.”

Self-treatment can also impair judgment and the objectivity of cosmetic therapies. “Also, when you’re pointing a laser at your own face and posting it on social media, it gives viewers the impression that this is not a serious medical treatment when it really is,” she emphasized. In addition, “when you treat yourself, you lose the ability to see the proper clinical endpoint. You also lose the ability to see the angle and the appropriate position for injection to avoid intervascular occlusion.”

Neither Dr. Stankiewicz nor Dr. Ibrahimi reported having relevant financial disclosures.

At least once a week,

Those images may help Dr. Stankiewicz understand patient preferences in terms of lip size and proportion, but she points out that shape is unique to each person. “I tell them: ‘All we can do is enhance that lip shape with filler. We can’t give you somebody else’s lip shape with an injection of filler.’ ”

During a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy, she and Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD, dispelled this and other false dogmas that they hear from some clinicians who practice aesthetic medicine and the patients who see them.

Wait 1 year before treating traumatic and surgical scars with vascular and fractional CO2 lasers. “I don’t think this is controversial anymore, because there is a boatload of data, which has shown that early treatment can prevent hypertrophic scarring and promote scar maturation,” said Dr. Stankiewicz, who practices dermatology in Park City, Utah. “Histology has also shown more organized dermal collagen from early treatment. Of course, there will be situations where you may want to hold off, like doing an ablative fractional [laser treatment] over the scar of a joint replacement ... where you may risk infection.” In her clinic, she routinely treats scars on the same day as suture removal, “as long as the healing looks appropriate.”

Dr. Ibrahimi, a dermatologist and medical director of the Connecticut Skin Institute, Stamford, also jumps on treating scars early. For a patient with postacne erythema, for example, he will use a pulsed-dye laser, which he believes will prevent scars from becoming atrophic.

Used equipment is a better investment than new equipment. While purchasing used laser and light devices can save money, especially when starting out, be wary of potential pitfalls, including the fact that many devices have disposable tips. “If your laser isn’t certified or you’re not the authorized owner of the device, you won’t be able to buy the disposables,” Dr. Stankiewicz noted. “So, before you buy a used device, ensure that you can buy them.”

Also, consider the cost of service if the device breaks down, she advised. Some lasers are complicated to service and others have codes set by the manufacturer so that only contracted engineers can work on them. “Otherwise, third-party engineers and service providers have to figure out how to crack the code to get into the machine,” she said. “If you’re in the situation where you have to ask the manufacturer to service your device, you have to pay a lot of money to recertify your device. Then you’ve lost all the savings you thought you made by buying a used machine.” She prefers to negotiate a good deal on a new device. “Often, a very good deal on a new device can rival the offer of a used one.”

Dr. Ibrahimi recalled buying a used fractional laser that came with a 30-day guarantee, but it stopped working around day 45. “I didn’t have much recourse there,” he said during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “You can’t go back to the company [for repair] unless you pay a recertification fee.”

Avoid exercise after Botox treatment. Although inverted yoga poses and lying down should be avoided for several hours after receiving Botox, there are no other limits to other forms of exercise post treatment, Dr. Stankiewicz said. If she suspects that a patient will develop bruising on one or more injection sites, she treats the areas with a laser. “Doing this on the same day as Botox treatment doesn’t always stop or treat bruising, many times it does.”

Another myth she hears is that it is not safe to fly in an airplane after Botox treatment. “That recommendation comes from the fact that the atmospheric pressure is lower in an airplane, so we worry about the risk of Botox spread,” Dr. Stankiewicz said. “But I practice at 7,000 feet above sea level, which is the same atmospheric pressure as that in an airplane,” she added, noting Botox is administered throughout the day in her practice and she does not see increased complications or worry about spread.

Clinician self-treatment is okay. In the opinion of Dr. Stankiewicz, aesthetic clinicians who treat themselves “have a fool for a patient.” She added: “Although no one is going to blame you and may not even know if you give yourself a little Botox touch-up at home, glorifying self-treatment on social media must stop. It’s dangerous and it can be ineffective.”

Self-treatment can also impair judgment and the objectivity of cosmetic therapies. “Also, when you’re pointing a laser at your own face and posting it on social media, it gives viewers the impression that this is not a serious medical treatment when it really is,” she emphasized. In addition, “when you treat yourself, you lose the ability to see the proper clinical endpoint. You also lose the ability to see the angle and the appropriate position for injection to avoid intervascular occlusion.”

Neither Dr. Stankiewicz nor Dr. Ibrahimi reported having relevant financial disclosures.

At least once a week,

Those images may help Dr. Stankiewicz understand patient preferences in terms of lip size and proportion, but she points out that shape is unique to each person. “I tell them: ‘All we can do is enhance that lip shape with filler. We can’t give you somebody else’s lip shape with an injection of filler.’ ”

During a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy, she and Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD, dispelled this and other false dogmas that they hear from some clinicians who practice aesthetic medicine and the patients who see them.

Wait 1 year before treating traumatic and surgical scars with vascular and fractional CO2 lasers. “I don’t think this is controversial anymore, because there is a boatload of data, which has shown that early treatment can prevent hypertrophic scarring and promote scar maturation,” said Dr. Stankiewicz, who practices dermatology in Park City, Utah. “Histology has also shown more organized dermal collagen from early treatment. Of course, there will be situations where you may want to hold off, like doing an ablative fractional [laser treatment] over the scar of a joint replacement ... where you may risk infection.” In her clinic, she routinely treats scars on the same day as suture removal, “as long as the healing looks appropriate.”

Dr. Ibrahimi, a dermatologist and medical director of the Connecticut Skin Institute, Stamford, also jumps on treating scars early. For a patient with postacne erythema, for example, he will use a pulsed-dye laser, which he believes will prevent scars from becoming atrophic.

Used equipment is a better investment than new equipment. While purchasing used laser and light devices can save money, especially when starting out, be wary of potential pitfalls, including the fact that many devices have disposable tips. “If your laser isn’t certified or you’re not the authorized owner of the device, you won’t be able to buy the disposables,” Dr. Stankiewicz noted. “So, before you buy a used device, ensure that you can buy them.”

Also, consider the cost of service if the device breaks down, she advised. Some lasers are complicated to service and others have codes set by the manufacturer so that only contracted engineers can work on them. “Otherwise, third-party engineers and service providers have to figure out how to crack the code to get into the machine,” she said. “If you’re in the situation where you have to ask the manufacturer to service your device, you have to pay a lot of money to recertify your device. Then you’ve lost all the savings you thought you made by buying a used machine.” She prefers to negotiate a good deal on a new device. “Often, a very good deal on a new device can rival the offer of a used one.”

Dr. Ibrahimi recalled buying a used fractional laser that came with a 30-day guarantee, but it stopped working around day 45. “I didn’t have much recourse there,” he said during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “You can’t go back to the company [for repair] unless you pay a recertification fee.”

Avoid exercise after Botox treatment. Although inverted yoga poses and lying down should be avoided for several hours after receiving Botox, there are no other limits to other forms of exercise post treatment, Dr. Stankiewicz said. If she suspects that a patient will develop bruising on one or more injection sites, she treats the areas with a laser. “Doing this on the same day as Botox treatment doesn’t always stop or treat bruising, many times it does.”

Another myth she hears is that it is not safe to fly in an airplane after Botox treatment. “That recommendation comes from the fact that the atmospheric pressure is lower in an airplane, so we worry about the risk of Botox spread,” Dr. Stankiewicz said. “But I practice at 7,000 feet above sea level, which is the same atmospheric pressure as that in an airplane,” she added, noting Botox is administered throughout the day in her practice and she does not see increased complications or worry about spread.

Clinician self-treatment is okay. In the opinion of Dr. Stankiewicz, aesthetic clinicians who treat themselves “have a fool for a patient.” She added: “Although no one is going to blame you and may not even know if you give yourself a little Botox touch-up at home, glorifying self-treatment on social media must stop. It’s dangerous and it can be ineffective.”

Self-treatment can also impair judgment and the objectivity of cosmetic therapies. “Also, when you’re pointing a laser at your own face and posting it on social media, it gives viewers the impression that this is not a serious medical treatment when it really is,” she emphasized. In addition, “when you treat yourself, you lose the ability to see the proper clinical endpoint. You also lose the ability to see the angle and the appropriate position for injection to avoid intervascular occlusion.”

Neither Dr. Stankiewicz nor Dr. Ibrahimi reported having relevant financial disclosures.

FROM A LASER & AESTHETIC SKIN THERAPY COURSE

Saururus chinensis

Also known as Asian or Chinese lizard’s tail (or Sam-baekcho in Korea), Saururus chinensis is an East Asian plant used in traditional medicine for various indications including edema, gonorrhea, jaundice, hypertension, leproma, pneumonia, and rheumatoid arthritis.1,2 Specifically, Korean traditional medicine practitioners as well as Native Americans and early colonists in what is now the United States used the botanical to treat cancer, edema, rheumatoid arthritis, and other inflammatory conditions.2-4 Modern research has produced evidence supporting the use of this plant in the dermatologic realm. This column focuses on the relevant bench science and possible applications.

Various beneficial effects

In 2008, Yoo et al. found that the ethanol extract of the dried aerial parts of S. chinensis exhibit anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antinociceptive properties, which they suggested may partially account for the established therapeutic effects of the plant.2 Also, Lee et al. reported in 2012 on the antiproliferative effects against human cancer cell lines of neolignans found in S. chinensis.5

Antioxidant properties have been associated with S. chinensis. In 2014, Kim et al. reported that S. chinensis extract attenuated the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated neuroinflammatory response in BV-2 microglia cells, a result that the authors partly ascribed to the antioxidant constituents (particularly quercetin) of the plant.3

Atopic dermatitis

In 2008, Choi et al. determined that the leaves of S. chinensis impeded the formation of atopic dermatitis–like skin lesions in NC/Nga mice caused by repeated application of picryl chloride, potentially by stimulating the Th1 cell response, thus modulating Th1/Th2 imbalance. They concluded that S. chinensis has potential as an adjunct treatment option for atopic dermatitis.6

Anti-inflammatory activity

In 2010, Bae et al. studied the anti-inflammatory properties of sauchinone, a lignan derived from S. chinensis reputed to exert antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and hepatoprotective activity,7 using LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. They found that the lignan lowered tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha synthesis by inhibiting the c-Raf-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 phosphorylation pathway, accounting for the anti-inflammatory effects of the S. chinensis constituent.8

More recently, Zhang et al. determined that the ethanol extract of S. chinensis leaves impaired proinflammatory gene expression by blocking the TAK1/AP-1 pathway in LPS-treated RAW264.7 macrophages. They suggested that such suppression is a significant step in the anti-inflammatory function exhibited by the plant.1

Photoprotection

Park et al. investigated in 2013 the beneficial effects of sauchinone. Specifically, they studied potential photoprotective effects of the lignan against UVB in HaCaT human epidermal keratinocytes. They found that sauchinone (5-40 mcm) conferred significant protection as evaluated by cell viability and a toxicity assay. At 20-40 mcm, sauchinone blocked the upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)–1 proteins and decrease of type 1 collagen engendered by UVB exposure. The investigators further discovered that sauchinone diminished the synthesis of reactive oxygen species. Overall, they determined that sauchinone imparted protection by suppressing extracellular signal-regulated kinase, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and p38 MAPK signaling through the activation of oxidative defense enzymes.7

Potential use as a depigmenting agent

In 2009, Seo et al. isolated the lignans manassantin A and B from S. chinensis and determined that these compounds dose-dependently impeded melanin synthesis in alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone (alpha-MSH)–activated melanoma B16 cells. They also noted that manassantin A suppressed forskolin- or 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX)–induced melanin production and diminished cellular levels of IBMX-inducible tyrosinase protein. The lignan had no effect on the catalytic activity of cell-free tyrosinase, an important enzyme in melanin pigment production. The researchers concluded that their results suggest the potential for S. chinensis to be used to treat hyperpigmentation disorders.9

Two years later Lee et al. found that manassantin A, derived from S. chinensis, steadily suppressed the cAMP elevator IBMX- or dibutyryl cAMP-induced melanin synthesis in B16 cells or in melan-a melanocytes by down-regulating the expression of tyrosinase or the TRP1 gene. The lignan also inhibited microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) induction via the IBMX-activated cAMP-responsive element-binding protein (CREB) pathway, thus preventing the Ser-133 phosphorylation of CREB. The researchers concluded that this molecular disruption of melanin production suggests the potential for the use of manassantin A as a skin depigmenting agent.10

That same year, another S. chinensis lignan gained interest. Yun et al. investigated the effects of the S. chinensis lignan component saucerneol D on melanin synthesis in cAMP-elevated melanocytes. They found that the lignan efficiently impeded melanin product in B16 melanoma cells stimulated with alpha-MSH or other cAMP elevators. Saucerneol D was also credited with down-regulating alpha-MSH–induced gene expression of tyrosinase at the transcription level in B16 cells, suppressing alpha-MSH–induced phosphorylation of CREB in the cells, and inhibiting MITF induction. The investigators concluded that their results point to the potential of the S. chinensis lignan saucerneol D for the treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders.11

In 2012, Chang et al. observed that an extract of S. chinensis and one of its constituent lignans, manassantin B, prevented melanosome transport in normal human melanocytes and Melan-a melanocytes, by interrupting the interaction between melanophilin and myosin Va. The investigators concluded that as a substance that can hinder melanosome transport, manassantin B displays potential for use as depigmenting product.12

The following year, Lee et al. studied the effects of S. chinensis extracts on the melanogenesis signaling pathway activated by alpha-MSH, finding dose-dependent inhibition without provoking cytotoxicity in B16F10 cells. Further, the team found evidence that the depigmenting activity exhibited by S. chinensis extracts may occur as a result of MITF and tyrosinase expression stemming from elevated activity of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). They concluded that their results support further examination of S. chinensis for its potential to contribute to skin whitening.5

Conclusion

Multiple lignan constituents in this plant-derived ingredient appear to yield anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, photoprotective, and antitumor properties. Its inhibitory effects on melanin production and its antiaging abilities make it worthy of further study and consideration of inclusion in antiaging skin care products.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the division of cosmetic dermatology at the University of Miami in 1997. The third edition of her bestselling textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology,” was published in 2022. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions, a SaaS company used to generate skin care routines in the office and as an e-commerce solution. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Zhang J et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021 Oct 28;279:114400.

2. Yoo HJ et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008 Nov 20;120(2):282-6.

3. Kim BW et al. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014 Dec 16;14:502.

4. Lee DH et al. Biol Pharm Bull. 2013;36(5):772-9.

5. Lee YJ et al. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35(8):1361-6.

6. Choi MS et al. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008 Jan;31(1):51-6.

7. Park G et al. Biol Pharm Bull. 2013;36(7):1134-9.

8. Bae HB et al. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010 Sep;10(9):1022-8.

9. Seo CS et al. Phytother Res. 2009 Nov;23(11):1531-6.

10. Lee HD et al. Exp Dermatol. 2011 Sep;20(9):761-3.

11. Yun JY et al. Arch Pharm Res. 2011 Aug;34(8):1339-45.

12. Chang H et al. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012 Nov;25(6):765-72.

Also known as Asian or Chinese lizard’s tail (or Sam-baekcho in Korea), Saururus chinensis is an East Asian plant used in traditional medicine for various indications including edema, gonorrhea, jaundice, hypertension, leproma, pneumonia, and rheumatoid arthritis.1,2 Specifically, Korean traditional medicine practitioners as well as Native Americans and early colonists in what is now the United States used the botanical to treat cancer, edema, rheumatoid arthritis, and other inflammatory conditions.2-4 Modern research has produced evidence supporting the use of this plant in the dermatologic realm. This column focuses on the relevant bench science and possible applications.

Various beneficial effects

In 2008, Yoo et al. found that the ethanol extract of the dried aerial parts of S. chinensis exhibit anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antinociceptive properties, which they suggested may partially account for the established therapeutic effects of the plant.2 Also, Lee et al. reported in 2012 on the antiproliferative effects against human cancer cell lines of neolignans found in S. chinensis.5

Antioxidant properties have been associated with S. chinensis. In 2014, Kim et al. reported that S. chinensis extract attenuated the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated neuroinflammatory response in BV-2 microglia cells, a result that the authors partly ascribed to the antioxidant constituents (particularly quercetin) of the plant.3

Atopic dermatitis

In 2008, Choi et al. determined that the leaves of S. chinensis impeded the formation of atopic dermatitis–like skin lesions in NC/Nga mice caused by repeated application of picryl chloride, potentially by stimulating the Th1 cell response, thus modulating Th1/Th2 imbalance. They concluded that S. chinensis has potential as an adjunct treatment option for atopic dermatitis.6

Anti-inflammatory activity

In 2010, Bae et al. studied the anti-inflammatory properties of sauchinone, a lignan derived from S. chinensis reputed to exert antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and hepatoprotective activity,7 using LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. They found that the lignan lowered tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha synthesis by inhibiting the c-Raf-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 phosphorylation pathway, accounting for the anti-inflammatory effects of the S. chinensis constituent.8

More recently, Zhang et al. determined that the ethanol extract of S. chinensis leaves impaired proinflammatory gene expression by blocking the TAK1/AP-1 pathway in LPS-treated RAW264.7 macrophages. They suggested that such suppression is a significant step in the anti-inflammatory function exhibited by the plant.1

Photoprotection

Park et al. investigated in 2013 the beneficial effects of sauchinone. Specifically, they studied potential photoprotective effects of the lignan against UVB in HaCaT human epidermal keratinocytes. They found that sauchinone (5-40 mcm) conferred significant protection as evaluated by cell viability and a toxicity assay. At 20-40 mcm, sauchinone blocked the upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)–1 proteins and decrease of type 1 collagen engendered by UVB exposure. The investigators further discovered that sauchinone diminished the synthesis of reactive oxygen species. Overall, they determined that sauchinone imparted protection by suppressing extracellular signal-regulated kinase, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and p38 MAPK signaling through the activation of oxidative defense enzymes.7

Potential use as a depigmenting agent