User login

Teens & tobacco use: USPSTF issues draft recs on prevention, cessation

Reference

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Draft Evidence Review for Prevention and Cessation of Tobacco Use in Children and Adolescents: Primary Care Interventions. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-evidence-review/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions. Accessed July 8, 2019.

Reference

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Draft Evidence Review for Prevention and Cessation of Tobacco Use in Children and Adolescents: Primary Care Interventions. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-evidence-review/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions. Accessed July 8, 2019.

Reference

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Draft Evidence Review for Prevention and Cessation of Tobacco Use in Children and Adolescents: Primary Care Interventions. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-evidence-review/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions. Accessed July 8, 2019.

Fetal alcohol exposure overlooked again?

New study on large youth sample is well done – with a glaring exception

In 2016, two researchers published a meta-analysis on gray matter abnormalities in youth who had conduct problems.

The study by Jack C. Rogers, PhD, and Stephane A. De Brito, PhD, found 13 well-done studies that included 394 youth with conduct problems and 390 typically developing youth. Compared with the typically developing youth, the conduct-disordered youth had decreased gray matter volume (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Jan;73[1]:64-72).

As I knew one of the researchers in one of the studies that made the cut, I called him up and asked whether their research had controlled for fetal alcohol exposure. They had not. I found this very curious because my experience is that youth who have been labeled with conduct disorder often have histories of prenatal fetal alcohol exposure. In addition, my understanding is that youth who have been exposed to prenatal alcohol often have symptoms of conduct disorder. Furthermore, research has shown that such youth have smaller brains (Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001 Mar;43[3]:148-54). I wondered whether the youth studied in that trial had been exposed to alcohol prenatally.

More recently, this problem has resurfaced. An article by Antonia N. Kaczkurkin, PhD, and associates about a large sample of youth was nicely done. But again, the variable of fetal alcohol exposure was not considered. The study was an elegant one that provides a strong rationale for consideration of a “psychopathology factor” in human life (Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Jun 24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.1807035). It shored up that argument by doing neuroimaging studies on a reasonably large sample of youth and showed that reduced cortical thickness (gray matter volume) was associated with overall psychopathology. With the exception of failing to consider the variable of fetal alcohol exposure, the study is a valuable addition to our understanding of what might be going on with psychiatric disorders.

Unfortunately – while hating to sound like a broken record – I noticed that there was no consideration of fetal alcohol exposure as a cause for the findings of the study. It does not seem like a large leap to hypothesize some of these brain imaging studies that find smaller brain components associated with psychopathology and conduct disorder to be a dynamic of fetal alcohol exposure.

It seems to me that we made a huge mistake in public health in asking women only whether they were drinking while they were pregnant because it was the wrong question. The right question is – “When did you realize you were pregnant, and were you doing any social drinking before you knew you were pregnant?”

The former editor of the American Journal of Psychiatry – Robert A. Freedman, MD – suggests that by giving phosphatidyl choline to pregnant women, such problems could be prevented.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s Medical/Surgical-Psychiatry Inpatient Unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago. In 2019, he was awarded the Adolph Meyer Award by the American Psychiatric Association for lifetime achievement in psychiatric research.

New study on large youth sample is well done – with a glaring exception

New study on large youth sample is well done – with a glaring exception

In 2016, two researchers published a meta-analysis on gray matter abnormalities in youth who had conduct problems.

The study by Jack C. Rogers, PhD, and Stephane A. De Brito, PhD, found 13 well-done studies that included 394 youth with conduct problems and 390 typically developing youth. Compared with the typically developing youth, the conduct-disordered youth had decreased gray matter volume (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Jan;73[1]:64-72).

As I knew one of the researchers in one of the studies that made the cut, I called him up and asked whether their research had controlled for fetal alcohol exposure. They had not. I found this very curious because my experience is that youth who have been labeled with conduct disorder often have histories of prenatal fetal alcohol exposure. In addition, my understanding is that youth who have been exposed to prenatal alcohol often have symptoms of conduct disorder. Furthermore, research has shown that such youth have smaller brains (Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001 Mar;43[3]:148-54). I wondered whether the youth studied in that trial had been exposed to alcohol prenatally.

More recently, this problem has resurfaced. An article by Antonia N. Kaczkurkin, PhD, and associates about a large sample of youth was nicely done. But again, the variable of fetal alcohol exposure was not considered. The study was an elegant one that provides a strong rationale for consideration of a “psychopathology factor” in human life (Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Jun 24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.1807035). It shored up that argument by doing neuroimaging studies on a reasonably large sample of youth and showed that reduced cortical thickness (gray matter volume) was associated with overall psychopathology. With the exception of failing to consider the variable of fetal alcohol exposure, the study is a valuable addition to our understanding of what might be going on with psychiatric disorders.

Unfortunately – while hating to sound like a broken record – I noticed that there was no consideration of fetal alcohol exposure as a cause for the findings of the study. It does not seem like a large leap to hypothesize some of these brain imaging studies that find smaller brain components associated with psychopathology and conduct disorder to be a dynamic of fetal alcohol exposure.

It seems to me that we made a huge mistake in public health in asking women only whether they were drinking while they were pregnant because it was the wrong question. The right question is – “When did you realize you were pregnant, and were you doing any social drinking before you knew you were pregnant?”

The former editor of the American Journal of Psychiatry – Robert A. Freedman, MD – suggests that by giving phosphatidyl choline to pregnant women, such problems could be prevented.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s Medical/Surgical-Psychiatry Inpatient Unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago. In 2019, he was awarded the Adolph Meyer Award by the American Psychiatric Association for lifetime achievement in psychiatric research.

In 2016, two researchers published a meta-analysis on gray matter abnormalities in youth who had conduct problems.

The study by Jack C. Rogers, PhD, and Stephane A. De Brito, PhD, found 13 well-done studies that included 394 youth with conduct problems and 390 typically developing youth. Compared with the typically developing youth, the conduct-disordered youth had decreased gray matter volume (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Jan;73[1]:64-72).

As I knew one of the researchers in one of the studies that made the cut, I called him up and asked whether their research had controlled for fetal alcohol exposure. They had not. I found this very curious because my experience is that youth who have been labeled with conduct disorder often have histories of prenatal fetal alcohol exposure. In addition, my understanding is that youth who have been exposed to prenatal alcohol often have symptoms of conduct disorder. Furthermore, research has shown that such youth have smaller brains (Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001 Mar;43[3]:148-54). I wondered whether the youth studied in that trial had been exposed to alcohol prenatally.

More recently, this problem has resurfaced. An article by Antonia N. Kaczkurkin, PhD, and associates about a large sample of youth was nicely done. But again, the variable of fetal alcohol exposure was not considered. The study was an elegant one that provides a strong rationale for consideration of a “psychopathology factor” in human life (Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Jun 24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.1807035). It shored up that argument by doing neuroimaging studies on a reasonably large sample of youth and showed that reduced cortical thickness (gray matter volume) was associated with overall psychopathology. With the exception of failing to consider the variable of fetal alcohol exposure, the study is a valuable addition to our understanding of what might be going on with psychiatric disorders.

Unfortunately – while hating to sound like a broken record – I noticed that there was no consideration of fetal alcohol exposure as a cause for the findings of the study. It does not seem like a large leap to hypothesize some of these brain imaging studies that find smaller brain components associated with psychopathology and conduct disorder to be a dynamic of fetal alcohol exposure.

It seems to me that we made a huge mistake in public health in asking women only whether they were drinking while they were pregnant because it was the wrong question. The right question is – “When did you realize you were pregnant, and were you doing any social drinking before you knew you were pregnant?”

The former editor of the American Journal of Psychiatry – Robert A. Freedman, MD – suggests that by giving phosphatidyl choline to pregnant women, such problems could be prevented.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s Medical/Surgical-Psychiatry Inpatient Unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago. In 2019, he was awarded the Adolph Meyer Award by the American Psychiatric Association for lifetime achievement in psychiatric research.

Depression, anxiety among elderly breast cancer survivors linked to increased opioid use, death

Mental health comorbidities increase the rates of opioid use and mortality among breast cancer survivors on endocrine therapy, based on a retrospective study of more than 10,000 patients in a Medicare-linked database.

Screen for mental health conditions in the early stages of cancer care and lean toward opioid alternatives for pain management, advised lead author Raj Desai, MS, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and colleagues.

“The complex relationship among breast cancer, mental health problems, and the use of opioids is not well understood, despite the high prevalence of mental health comorbidities like depression and anxiety in breast cancer survivors, and the high rate of opioid use in those on AET [adjuvant endocrine therapy],” the investigators wrote in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

“Therefore, this study aimed to determine whether breast cancer survivors with varying levels of mental health comorbidities, such as depression and anxiety, are more likely to use opioids for AET-related pain,” they added.

The study involved 10,452 breast cancer survivors who first filled an AET prescription from 2006 to 2012 and had follow-up records available for at least 2 years. All patients had a diagnosis of incident, primary, hormone receptor–positive, stage I-III breast cancer. Data were drawn from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare linked database. Records were evaluated for diagnoses of mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety, opioid use, and survival.

Analysis showed that the most common mental health conditions were depression and anxiety, diagnosed in 554 and 246 women, respectively. Patients with mental health comorbidities were compared with patients who did not have such problems, using both unmatched and matched cohorts. While unmatched comparison for opioid use was not statistically significant, matched comparison showed that survivors with mental health comorbidities were 33% more likely to use opioids than those without mental health comorbidities (95% confidence interval, 1.06-1.68). Similarly, greater adjusted probabilities of opioid use were reported in the mental health comorbidity cohort (72.5% vs. 66.9%; P = .01).

Concerning survival, unmatched comparison revealed a 44% higher risk of death among women with depression and a 32% increase associated with anxiety. Matched comparison showed an even higher increased risk of mortality among women with any mental health comorbidity (49%; P less than .05).

The investigators concluded that opioid use among breast cancer survivors with mental health comorbidities “remains a significant problem.”

“A need exists for collaborative care in the management of mental health comorbidities in women with breast cancer, which could improve symptoms, adherence to treatment, and recovery from these mental conditions,” the investigators wrote. “Mental health treatments also are recommended to be offered in primary care, which not only would be convenient for patients, but also would reduce the stigma associated with treatments for mental health comorbidities and improve the patient-provider relationship.”

The investigators reported financial relationships with Merck.

SOURCE: Desai R et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Jul 19. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00781.

Mental health comorbidities increase the rates of opioid use and mortality among breast cancer survivors on endocrine therapy, based on a retrospective study of more than 10,000 patients in a Medicare-linked database.

Screen for mental health conditions in the early stages of cancer care and lean toward opioid alternatives for pain management, advised lead author Raj Desai, MS, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and colleagues.

“The complex relationship among breast cancer, mental health problems, and the use of opioids is not well understood, despite the high prevalence of mental health comorbidities like depression and anxiety in breast cancer survivors, and the high rate of opioid use in those on AET [adjuvant endocrine therapy],” the investigators wrote in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

“Therefore, this study aimed to determine whether breast cancer survivors with varying levels of mental health comorbidities, such as depression and anxiety, are more likely to use opioids for AET-related pain,” they added.

The study involved 10,452 breast cancer survivors who first filled an AET prescription from 2006 to 2012 and had follow-up records available for at least 2 years. All patients had a diagnosis of incident, primary, hormone receptor–positive, stage I-III breast cancer. Data were drawn from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare linked database. Records were evaluated for diagnoses of mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety, opioid use, and survival.

Analysis showed that the most common mental health conditions were depression and anxiety, diagnosed in 554 and 246 women, respectively. Patients with mental health comorbidities were compared with patients who did not have such problems, using both unmatched and matched cohorts. While unmatched comparison for opioid use was not statistically significant, matched comparison showed that survivors with mental health comorbidities were 33% more likely to use opioids than those without mental health comorbidities (95% confidence interval, 1.06-1.68). Similarly, greater adjusted probabilities of opioid use were reported in the mental health comorbidity cohort (72.5% vs. 66.9%; P = .01).

Concerning survival, unmatched comparison revealed a 44% higher risk of death among women with depression and a 32% increase associated with anxiety. Matched comparison showed an even higher increased risk of mortality among women with any mental health comorbidity (49%; P less than .05).

The investigators concluded that opioid use among breast cancer survivors with mental health comorbidities “remains a significant problem.”

“A need exists for collaborative care in the management of mental health comorbidities in women with breast cancer, which could improve symptoms, adherence to treatment, and recovery from these mental conditions,” the investigators wrote. “Mental health treatments also are recommended to be offered in primary care, which not only would be convenient for patients, but also would reduce the stigma associated with treatments for mental health comorbidities and improve the patient-provider relationship.”

The investigators reported financial relationships with Merck.

SOURCE: Desai R et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Jul 19. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00781.

Mental health comorbidities increase the rates of opioid use and mortality among breast cancer survivors on endocrine therapy, based on a retrospective study of more than 10,000 patients in a Medicare-linked database.

Screen for mental health conditions in the early stages of cancer care and lean toward opioid alternatives for pain management, advised lead author Raj Desai, MS, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and colleagues.

“The complex relationship among breast cancer, mental health problems, and the use of opioids is not well understood, despite the high prevalence of mental health comorbidities like depression and anxiety in breast cancer survivors, and the high rate of opioid use in those on AET [adjuvant endocrine therapy],” the investigators wrote in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

“Therefore, this study aimed to determine whether breast cancer survivors with varying levels of mental health comorbidities, such as depression and anxiety, are more likely to use opioids for AET-related pain,” they added.

The study involved 10,452 breast cancer survivors who first filled an AET prescription from 2006 to 2012 and had follow-up records available for at least 2 years. All patients had a diagnosis of incident, primary, hormone receptor–positive, stage I-III breast cancer. Data were drawn from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare linked database. Records were evaluated for diagnoses of mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety, opioid use, and survival.

Analysis showed that the most common mental health conditions were depression and anxiety, diagnosed in 554 and 246 women, respectively. Patients with mental health comorbidities were compared with patients who did not have such problems, using both unmatched and matched cohorts. While unmatched comparison for opioid use was not statistically significant, matched comparison showed that survivors with mental health comorbidities were 33% more likely to use opioids than those without mental health comorbidities (95% confidence interval, 1.06-1.68). Similarly, greater adjusted probabilities of opioid use were reported in the mental health comorbidity cohort (72.5% vs. 66.9%; P = .01).

Concerning survival, unmatched comparison revealed a 44% higher risk of death among women with depression and a 32% increase associated with anxiety. Matched comparison showed an even higher increased risk of mortality among women with any mental health comorbidity (49%; P less than .05).

The investigators concluded that opioid use among breast cancer survivors with mental health comorbidities “remains a significant problem.”

“A need exists for collaborative care in the management of mental health comorbidities in women with breast cancer, which could improve symptoms, adherence to treatment, and recovery from these mental conditions,” the investigators wrote. “Mental health treatments also are recommended to be offered in primary care, which not only would be convenient for patients, but also would reduce the stigma associated with treatments for mental health comorbidities and improve the patient-provider relationship.”

The investigators reported financial relationships with Merck.

SOURCE: Desai R et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Jul 19. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00781.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

Pharmacist stigma a barrier to rural buprenorphine access

SAN ANTONIO – Most attention paid to barriers for medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder has focused on prescribers and patients, but pharmacists are “a neglected link in the chain,” according to Hannah Cooper, ScD, an assistant professor of behavioral sciences and health education at Emory University, Atlanta.

“Pharmacy-based dispensing of buprenorphine is one of the medication’s major advances over methadone,” Dr. Cooper told attendees at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence. Yet, early interviews she and her colleagues conducted with rural Kentucky pharmacist colleagues in the CARE2HOPE study “revealed that pharmacy-level barriers might also curtail access to buprenorphine.”

Little research has examined those barriers, but Dr. Cooper noted. Further, anecdotal evidence has suggested that wholesaler concerns about Drug Enforcement Administration restrictions on dispensing buprenorphine has caused shortages at pharmacies.

Dr. Cooper and colleagues, therefore, designed a qualitative study aimed at learning about pharmacists’ attitudes and dispensing practices related to buprenorphine. They also looked at whether DEA limits actually exist on dispensing the drug. They interviewed 14 pharmacists operating 15 pharmacies across all 12 counties in two rural Kentucky health districts. Eleven of the pharmacists worked in independent pharmacies; the others worked at chains. Six pharmacies dispensed more than 100 buprenorphine prescriptions a month, five dispensed only several dozen a month, and four refused to dispense it at all.

Perceptions of federal restrictions

“Variations in buprenorphine dispensing did not solely reflect underlying variations in local need or prescribing practices,” Dr. Cooper said. At 12 of the 15 pharmacies, limits on buprenorphine resulted from a perceived DEA “cap” on dispensing the drug or “because of distrust in buprenorphine itself, its prescribers and its patients.”

The perceived cap from the DEA was shrouded in uncertainty: 10 of the pharmacists said the DEA capped the percentage of controlled substances pharmacists could dispense that were opioids, yet the pharmacists did not know what that percentage was.

Five of those interviewed said the cap often significantly cut short how many buprenorphine prescriptions they would dispense. Since they did not know how much the cap was, they internally set arbitrary limits, such as dispensing two prescriptions per day, to avoid risk of the DEA investigating their pharmacy.

Yet, those limits could not meet patient demand, so several pharmacists rationed buprenorphine only to local residents or long-term customers, causing additional problems. That practice strained relationships with prescribers, who then had to call multiple pharmacies to find one that would dispense the drug to new patients. It also put pharmacy staff at risk when a rejection angered a customer and “undermined local recovery efforts,” Dr. Cooper said.

Five other pharmacists, however, did not ration their buprenorphine and did not worry about exceeding the DEA cap.

No numerical cap appears to exist, but DEA regulations and the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act do require internal opioid surveillance systems at wholesalers that flag suspicious orders of controlled substances, including buprenorphine. And they enforce it: An $80 million settlement in 2013 resulted from the DEA’s charge that Walgreens distribution centers did not report suspicious drug orders.

Stigma among some pharmacists

Six of the pharmacists had low trust in buprenorphine and in those who prescribed it and used it, Dr. Cooper reported. Three would not dispense the drug at all, and two would not take new buprenorphine patients.

One such pharmacist told researchers: “It is supposed to be the drug to help them [recover.] They want Suboxone worse than they do the hydrocodone. … It’s not what it’s designed to be.”

Those pharmacists also reported believing that malpractice was common among prescribers, who, for example, did not provide required counseling to patients or did not quickly wean them off buprenorphine. The pharmacists perceived the physicians prescribing buprenorphine as doing so only to make more money, just as they had done by prescribing opioids in the first place.

Those pharmacists also believed the patients themselves sold buprenorphine to make money and that opioid use disorder was a choice. They told researchers that dispensing buprenorphine would bring more drug users to their stores and subsequently hurt business.

Yet, those beliefs were not universal among the pharmacists. Eight believed buprenorphine was an appropriate opioid use disorder treatment and had positive attitudes toward patients. Unlike those who viewed the disorder as a choice, those pharmacists saw it as a disease and viewed the patients admirably for their commitment to recovery.

Though a small, qualitative study, those findings suggest a need to more closely examine how pharmacies affect access to medication to treat opioid use disorder, Dr. Cooper said.

“In an epicenter of the U.S. opioid epidemic, policies and stigma curtail access to buprenorphine,” she told attendees. “DEA regulations, the SUPPORT Act, and related lawsuits have led wholesalers to develop proprietary caps that force some pharmacists to ration the number of buprenorphine prescriptions they filled.” Some pharmacists will not dispense the drug at all, while others “limited dispensing to known or local patients and prescribers, a practice that pharmacists recognized hurt patients who had to travel far to reach prescribers.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health through CARE2HOPE, Rural Health Project, and the Emory Center for AIDS Research. The authors reported no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – Most attention paid to barriers for medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder has focused on prescribers and patients, but pharmacists are “a neglected link in the chain,” according to Hannah Cooper, ScD, an assistant professor of behavioral sciences and health education at Emory University, Atlanta.

“Pharmacy-based dispensing of buprenorphine is one of the medication’s major advances over methadone,” Dr. Cooper told attendees at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence. Yet, early interviews she and her colleagues conducted with rural Kentucky pharmacist colleagues in the CARE2HOPE study “revealed that pharmacy-level barriers might also curtail access to buprenorphine.”

Little research has examined those barriers, but Dr. Cooper noted. Further, anecdotal evidence has suggested that wholesaler concerns about Drug Enforcement Administration restrictions on dispensing buprenorphine has caused shortages at pharmacies.

Dr. Cooper and colleagues, therefore, designed a qualitative study aimed at learning about pharmacists’ attitudes and dispensing practices related to buprenorphine. They also looked at whether DEA limits actually exist on dispensing the drug. They interviewed 14 pharmacists operating 15 pharmacies across all 12 counties in two rural Kentucky health districts. Eleven of the pharmacists worked in independent pharmacies; the others worked at chains. Six pharmacies dispensed more than 100 buprenorphine prescriptions a month, five dispensed only several dozen a month, and four refused to dispense it at all.

Perceptions of federal restrictions

“Variations in buprenorphine dispensing did not solely reflect underlying variations in local need or prescribing practices,” Dr. Cooper said. At 12 of the 15 pharmacies, limits on buprenorphine resulted from a perceived DEA “cap” on dispensing the drug or “because of distrust in buprenorphine itself, its prescribers and its patients.”

The perceived cap from the DEA was shrouded in uncertainty: 10 of the pharmacists said the DEA capped the percentage of controlled substances pharmacists could dispense that were opioids, yet the pharmacists did not know what that percentage was.

Five of those interviewed said the cap often significantly cut short how many buprenorphine prescriptions they would dispense. Since they did not know how much the cap was, they internally set arbitrary limits, such as dispensing two prescriptions per day, to avoid risk of the DEA investigating their pharmacy.

Yet, those limits could not meet patient demand, so several pharmacists rationed buprenorphine only to local residents or long-term customers, causing additional problems. That practice strained relationships with prescribers, who then had to call multiple pharmacies to find one that would dispense the drug to new patients. It also put pharmacy staff at risk when a rejection angered a customer and “undermined local recovery efforts,” Dr. Cooper said.

Five other pharmacists, however, did not ration their buprenorphine and did not worry about exceeding the DEA cap.

No numerical cap appears to exist, but DEA regulations and the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act do require internal opioid surveillance systems at wholesalers that flag suspicious orders of controlled substances, including buprenorphine. And they enforce it: An $80 million settlement in 2013 resulted from the DEA’s charge that Walgreens distribution centers did not report suspicious drug orders.

Stigma among some pharmacists

Six of the pharmacists had low trust in buprenorphine and in those who prescribed it and used it, Dr. Cooper reported. Three would not dispense the drug at all, and two would not take new buprenorphine patients.

One such pharmacist told researchers: “It is supposed to be the drug to help them [recover.] They want Suboxone worse than they do the hydrocodone. … It’s not what it’s designed to be.”

Those pharmacists also reported believing that malpractice was common among prescribers, who, for example, did not provide required counseling to patients or did not quickly wean them off buprenorphine. The pharmacists perceived the physicians prescribing buprenorphine as doing so only to make more money, just as they had done by prescribing opioids in the first place.

Those pharmacists also believed the patients themselves sold buprenorphine to make money and that opioid use disorder was a choice. They told researchers that dispensing buprenorphine would bring more drug users to their stores and subsequently hurt business.

Yet, those beliefs were not universal among the pharmacists. Eight believed buprenorphine was an appropriate opioid use disorder treatment and had positive attitudes toward patients. Unlike those who viewed the disorder as a choice, those pharmacists saw it as a disease and viewed the patients admirably for their commitment to recovery.

Though a small, qualitative study, those findings suggest a need to more closely examine how pharmacies affect access to medication to treat opioid use disorder, Dr. Cooper said.

“In an epicenter of the U.S. opioid epidemic, policies and stigma curtail access to buprenorphine,” she told attendees. “DEA regulations, the SUPPORT Act, and related lawsuits have led wholesalers to develop proprietary caps that force some pharmacists to ration the number of buprenorphine prescriptions they filled.” Some pharmacists will not dispense the drug at all, while others “limited dispensing to known or local patients and prescribers, a practice that pharmacists recognized hurt patients who had to travel far to reach prescribers.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health through CARE2HOPE, Rural Health Project, and the Emory Center for AIDS Research. The authors reported no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – Most attention paid to barriers for medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder has focused on prescribers and patients, but pharmacists are “a neglected link in the chain,” according to Hannah Cooper, ScD, an assistant professor of behavioral sciences and health education at Emory University, Atlanta.

“Pharmacy-based dispensing of buprenorphine is one of the medication’s major advances over methadone,” Dr. Cooper told attendees at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence. Yet, early interviews she and her colleagues conducted with rural Kentucky pharmacist colleagues in the CARE2HOPE study “revealed that pharmacy-level barriers might also curtail access to buprenorphine.”

Little research has examined those barriers, but Dr. Cooper noted. Further, anecdotal evidence has suggested that wholesaler concerns about Drug Enforcement Administration restrictions on dispensing buprenorphine has caused shortages at pharmacies.

Dr. Cooper and colleagues, therefore, designed a qualitative study aimed at learning about pharmacists’ attitudes and dispensing practices related to buprenorphine. They also looked at whether DEA limits actually exist on dispensing the drug. They interviewed 14 pharmacists operating 15 pharmacies across all 12 counties in two rural Kentucky health districts. Eleven of the pharmacists worked in independent pharmacies; the others worked at chains. Six pharmacies dispensed more than 100 buprenorphine prescriptions a month, five dispensed only several dozen a month, and four refused to dispense it at all.

Perceptions of federal restrictions

“Variations in buprenorphine dispensing did not solely reflect underlying variations in local need or prescribing practices,” Dr. Cooper said. At 12 of the 15 pharmacies, limits on buprenorphine resulted from a perceived DEA “cap” on dispensing the drug or “because of distrust in buprenorphine itself, its prescribers and its patients.”

The perceived cap from the DEA was shrouded in uncertainty: 10 of the pharmacists said the DEA capped the percentage of controlled substances pharmacists could dispense that were opioids, yet the pharmacists did not know what that percentage was.

Five of those interviewed said the cap often significantly cut short how many buprenorphine prescriptions they would dispense. Since they did not know how much the cap was, they internally set arbitrary limits, such as dispensing two prescriptions per day, to avoid risk of the DEA investigating their pharmacy.

Yet, those limits could not meet patient demand, so several pharmacists rationed buprenorphine only to local residents or long-term customers, causing additional problems. That practice strained relationships with prescribers, who then had to call multiple pharmacies to find one that would dispense the drug to new patients. It also put pharmacy staff at risk when a rejection angered a customer and “undermined local recovery efforts,” Dr. Cooper said.

Five other pharmacists, however, did not ration their buprenorphine and did not worry about exceeding the DEA cap.

No numerical cap appears to exist, but DEA regulations and the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act do require internal opioid surveillance systems at wholesalers that flag suspicious orders of controlled substances, including buprenorphine. And they enforce it: An $80 million settlement in 2013 resulted from the DEA’s charge that Walgreens distribution centers did not report suspicious drug orders.

Stigma among some pharmacists

Six of the pharmacists had low trust in buprenorphine and in those who prescribed it and used it, Dr. Cooper reported. Three would not dispense the drug at all, and two would not take new buprenorphine patients.

One such pharmacist told researchers: “It is supposed to be the drug to help them [recover.] They want Suboxone worse than they do the hydrocodone. … It’s not what it’s designed to be.”

Those pharmacists also reported believing that malpractice was common among prescribers, who, for example, did not provide required counseling to patients or did not quickly wean them off buprenorphine. The pharmacists perceived the physicians prescribing buprenorphine as doing so only to make more money, just as they had done by prescribing opioids in the first place.

Those pharmacists also believed the patients themselves sold buprenorphine to make money and that opioid use disorder was a choice. They told researchers that dispensing buprenorphine would bring more drug users to their stores and subsequently hurt business.

Yet, those beliefs were not universal among the pharmacists. Eight believed buprenorphine was an appropriate opioid use disorder treatment and had positive attitudes toward patients. Unlike those who viewed the disorder as a choice, those pharmacists saw it as a disease and viewed the patients admirably for their commitment to recovery.

Though a small, qualitative study, those findings suggest a need to more closely examine how pharmacies affect access to medication to treat opioid use disorder, Dr. Cooper said.

“In an epicenter of the U.S. opioid epidemic, policies and stigma curtail access to buprenorphine,” she told attendees. “DEA regulations, the SUPPORT Act, and related lawsuits have led wholesalers to develop proprietary caps that force some pharmacists to ration the number of buprenorphine prescriptions they filled.” Some pharmacists will not dispense the drug at all, while others “limited dispensing to known or local patients and prescribers, a practice that pharmacists recognized hurt patients who had to travel far to reach prescribers.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health through CARE2HOPE, Rural Health Project, and the Emory Center for AIDS Research. The authors reported no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM CPDD 2019

Smoking-cessation attempts changed little over 7-year span

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The median percentage of adult smokers who tried to quit cigarettes over the past year went from 64.9% in 2011 to 65.4% in 2017, CDC investigators reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, but the rate has gone down since 2014, when it reached 66.9%.

“The limited progress in increasing quit attempts … together with the variation in quit attempt prevalence among states, underscores the importance of enhanced efforts to motivate and help smokers to quit,” wrote Kimp Walton, MS, of the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion and associates.

State-specific trends in quit-attempt rates reflected the national situation. The prevalence of past-year cessation attempts went up significantly in four states (Kansas, Louisiana, Virginia, and West Virginia) from 2011 to 2017, went down significantly in two states (New York and Tennessee), and did not change significantly in the other 44 states and the District of Columbia, they wrote.

In 2017, cigarette smokers in Connecticut were the most likely to have tried to quit in the past year, with a rate of 71.6%. The only other places with rates greater than 70% were Delaware, D.C., New Jersey, and Texas. The lowest quit-attempt rate that year, 58.6%, belonged to Wisconsin, with Iowa and Missouri the only other states under 60%, the investigators reported based on data from annual Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System surveys.

“Because most smokers make multiple quit attempts before succeeding, as many as 30 on average, tobacco dependence is viewed as a chronic, relapsing condition that requires repeated intervention. Smokers should be encouraged to keep trying to quit until they succeed, and health care providers should be encouraged to keep supporting smokers until they quit,” investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Walton K et al. MMWR. 2019 Jul 19;68(28):621-6.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The median percentage of adult smokers who tried to quit cigarettes over the past year went from 64.9% in 2011 to 65.4% in 2017, CDC investigators reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, but the rate has gone down since 2014, when it reached 66.9%.

“The limited progress in increasing quit attempts … together with the variation in quit attempt prevalence among states, underscores the importance of enhanced efforts to motivate and help smokers to quit,” wrote Kimp Walton, MS, of the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion and associates.

State-specific trends in quit-attempt rates reflected the national situation. The prevalence of past-year cessation attempts went up significantly in four states (Kansas, Louisiana, Virginia, and West Virginia) from 2011 to 2017, went down significantly in two states (New York and Tennessee), and did not change significantly in the other 44 states and the District of Columbia, they wrote.

In 2017, cigarette smokers in Connecticut were the most likely to have tried to quit in the past year, with a rate of 71.6%. The only other places with rates greater than 70% were Delaware, D.C., New Jersey, and Texas. The lowest quit-attempt rate that year, 58.6%, belonged to Wisconsin, with Iowa and Missouri the only other states under 60%, the investigators reported based on data from annual Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System surveys.

“Because most smokers make multiple quit attempts before succeeding, as many as 30 on average, tobacco dependence is viewed as a chronic, relapsing condition that requires repeated intervention. Smokers should be encouraged to keep trying to quit until they succeed, and health care providers should be encouraged to keep supporting smokers until they quit,” investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Walton K et al. MMWR. 2019 Jul 19;68(28):621-6.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The median percentage of adult smokers who tried to quit cigarettes over the past year went from 64.9% in 2011 to 65.4% in 2017, CDC investigators reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, but the rate has gone down since 2014, when it reached 66.9%.

“The limited progress in increasing quit attempts … together with the variation in quit attempt prevalence among states, underscores the importance of enhanced efforts to motivate and help smokers to quit,” wrote Kimp Walton, MS, of the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion and associates.

State-specific trends in quit-attempt rates reflected the national situation. The prevalence of past-year cessation attempts went up significantly in four states (Kansas, Louisiana, Virginia, and West Virginia) from 2011 to 2017, went down significantly in two states (New York and Tennessee), and did not change significantly in the other 44 states and the District of Columbia, they wrote.

In 2017, cigarette smokers in Connecticut were the most likely to have tried to quit in the past year, with a rate of 71.6%. The only other places with rates greater than 70% were Delaware, D.C., New Jersey, and Texas. The lowest quit-attempt rate that year, 58.6%, belonged to Wisconsin, with Iowa and Missouri the only other states under 60%, the investigators reported based on data from annual Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System surveys.

“Because most smokers make multiple quit attempts before succeeding, as many as 30 on average, tobacco dependence is viewed as a chronic, relapsing condition that requires repeated intervention. Smokers should be encouraged to keep trying to quit until they succeed, and health care providers should be encouraged to keep supporting smokers until they quit,” investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Walton K et al. MMWR. 2019 Jul 19;68(28):621-6.

FROM MMWR

Drug overdose deaths declined in 2018

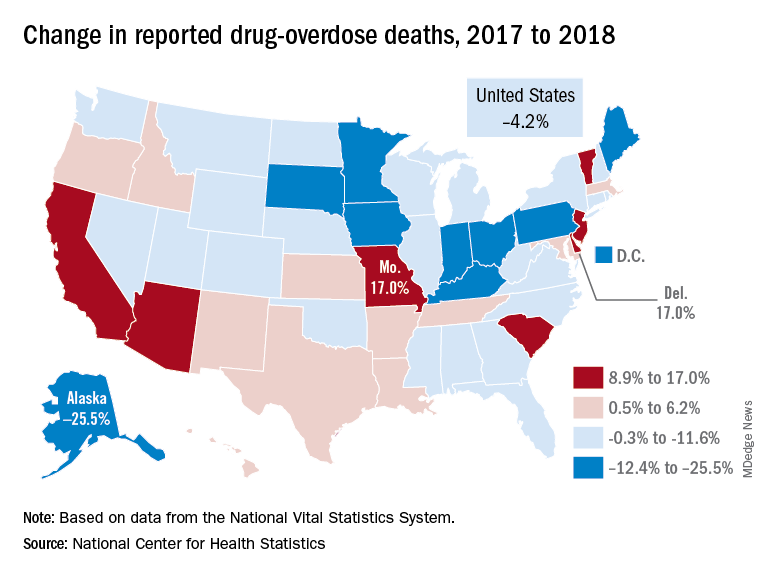

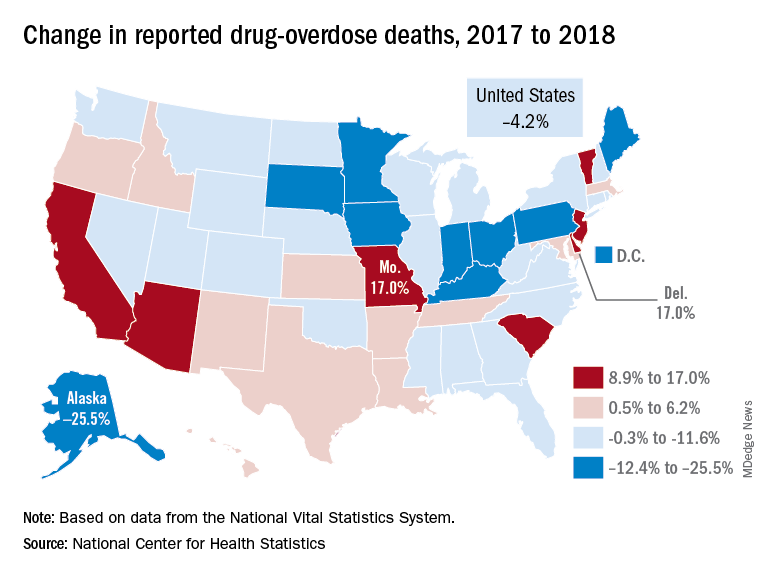

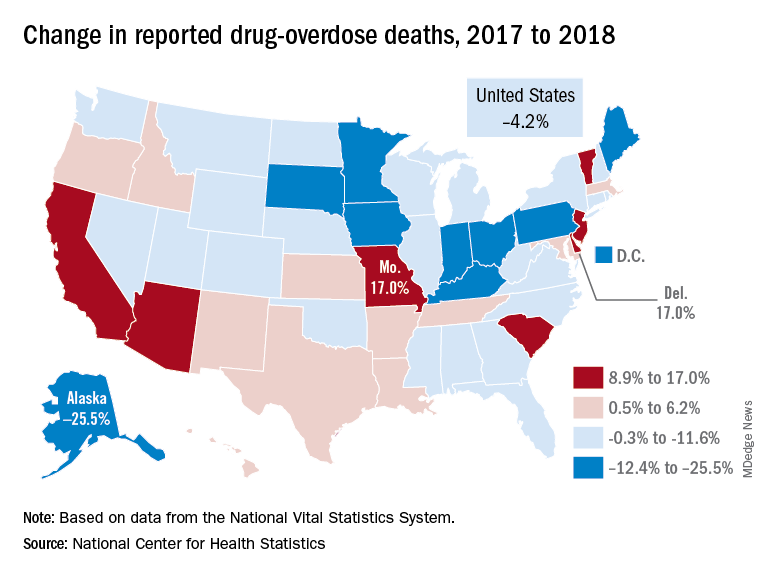

Reported drug overdose deaths in the United States declined by 4.2% from December 2017 to December 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported on July 17.

“The latest provisional data on overdose deaths show that America’s united efforts to curb opioid use disorder and addiction are working. Lives are being saved, and we’re beginning to win the fight against this crisis,” Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a written statement. “Under President Trump’s leadership, and thanks to efforts on the ground by communities across America, the number of patients receiving medication-assisted treatment has risen, distribution of overdose-reversing drugs is up, and nationwide opioid prescriptions are down.”

The new data show that total drug overdose deaths were down from 70,699 in 2017 to 67,744 in 2018, a drop of 4.2%, the CDC said.

States, of course, fell on both sides of that national figure. Delaware and Missouri wound up on the other end of the scale with increases of 17.0% from 2017 to 2018. Deaths in Vermont, Arizona, and South Carolina also rose by double digits, data from the National Vital Statistics System show.

“While the declining trend of overdose deaths is an encouraging sign, by no means have we declared victory against the epidemic or addiction in general,” Secretary Azar said. “This crisis developed over 2 decades and it will not be solved overnight. We also face other emerging threats, like concerning trends in cocaine and methamphetamine overdoses.”

Reported drug overdose deaths in the United States declined by 4.2% from December 2017 to December 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported on July 17.

“The latest provisional data on overdose deaths show that America’s united efforts to curb opioid use disorder and addiction are working. Lives are being saved, and we’re beginning to win the fight against this crisis,” Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a written statement. “Under President Trump’s leadership, and thanks to efforts on the ground by communities across America, the number of patients receiving medication-assisted treatment has risen, distribution of overdose-reversing drugs is up, and nationwide opioid prescriptions are down.”

The new data show that total drug overdose deaths were down from 70,699 in 2017 to 67,744 in 2018, a drop of 4.2%, the CDC said.

States, of course, fell on both sides of that national figure. Delaware and Missouri wound up on the other end of the scale with increases of 17.0% from 2017 to 2018. Deaths in Vermont, Arizona, and South Carolina also rose by double digits, data from the National Vital Statistics System show.

“While the declining trend of overdose deaths is an encouraging sign, by no means have we declared victory against the epidemic or addiction in general,” Secretary Azar said. “This crisis developed over 2 decades and it will not be solved overnight. We also face other emerging threats, like concerning trends in cocaine and methamphetamine overdoses.”

Reported drug overdose deaths in the United States declined by 4.2% from December 2017 to December 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported on July 17.

“The latest provisional data on overdose deaths show that America’s united efforts to curb opioid use disorder and addiction are working. Lives are being saved, and we’re beginning to win the fight against this crisis,” Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a written statement. “Under President Trump’s leadership, and thanks to efforts on the ground by communities across America, the number of patients receiving medication-assisted treatment has risen, distribution of overdose-reversing drugs is up, and nationwide opioid prescriptions are down.”

The new data show that total drug overdose deaths were down from 70,699 in 2017 to 67,744 in 2018, a drop of 4.2%, the CDC said.

States, of course, fell on both sides of that national figure. Delaware and Missouri wound up on the other end of the scale with increases of 17.0% from 2017 to 2018. Deaths in Vermont, Arizona, and South Carolina also rose by double digits, data from the National Vital Statistics System show.

“While the declining trend of overdose deaths is an encouraging sign, by no means have we declared victory against the epidemic or addiction in general,” Secretary Azar said. “This crisis developed over 2 decades and it will not be solved overnight. We also face other emerging threats, like concerning trends in cocaine and methamphetamine overdoses.”

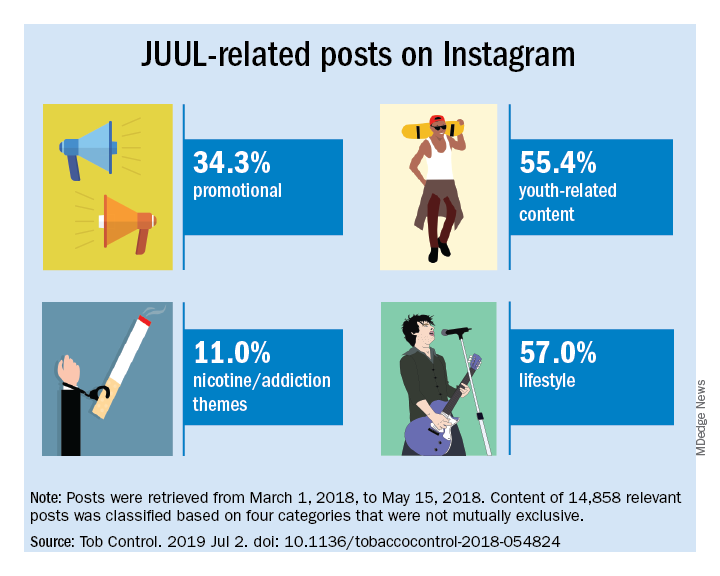

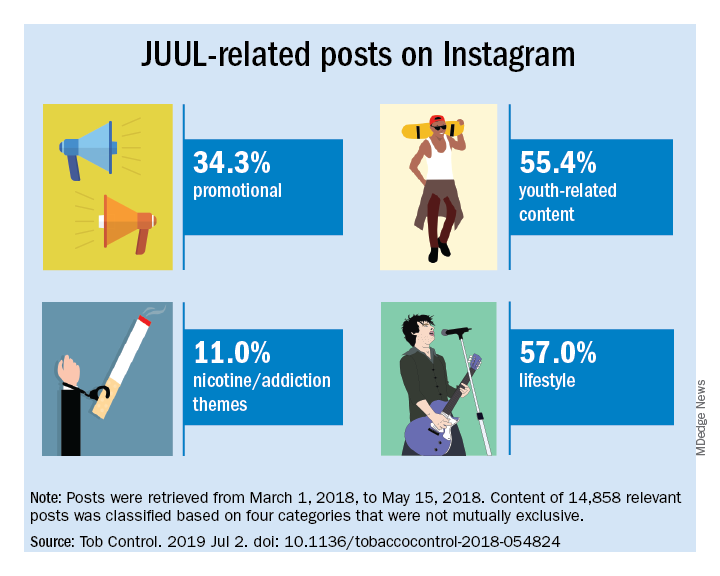

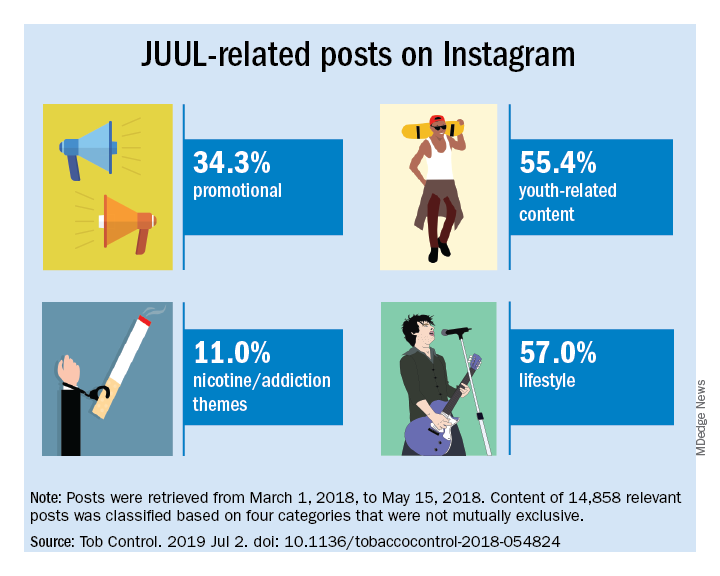

Vaping device marketers take aim at youth through social media

with targeted messages and images, a study of e-cigarette promotion has found.

In 2018, the JUUL company declared a commitment to support efforts to raise the age of legal purchase of tobacco to age 21 years in all U.S. states. In addition, JUUL deleted its official Facebook and Instagram accounts in November 2018, but the promotion of these products has continued through affiliated marketing campaigns from other online vendors.

Vaping among teens has shot up in popularity in recent years. The prevalence of vaping among young people aged 16-19 years has been estimated at 16% in 2018, up from 11% in 2017 (BMJ. 2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.12219. A study published in JAMA Pediatrics (2019;173[7]:690-92) found that an estimated 81% of users following a popular Twitter account (@JUULvapor) were aged 13-20 years, with 45% in the 13-17 year age range.

Elizabeth C. Hair, PhD, senior vice president of the Truth Initiative Schroeder Institute, and a team of investigators conducted a study of the “proliferation of JUUL-related content across four themes over a 3-month period: overt promotional content, nicotine and addiction-related content, lifestyle content, and content related to youth culture.” The study appeared online in Tobacco Control (2019 Jul 2; doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054824).

The investigators did a content analysis of social media posts on Instagram related to JUUL and JUUL-like products from March 1 to May 15, 2018. Hash-tag keyword queries of JUUL-related posts on Instagram were collected from the Instagram application programming interface through NUVI, a licensed syndicator of the Instagram firehose. The researchers used 50 hashtags to capture and enumerate individual posts. Examples of the hashtags used are #juul, #juuling, #juulvapor, #juulpod, #switchtojuul, and #juulgang. All posts were included from the official JUUL account and JUUL-related accounts with the highest number of followers at the time of data collection (e.g., @juulcentral, @juulnation, @juul_university, @juul.girls).

The search identified 14,838 posts by 5,201 unique users that featured content relating to product promotion, nicotine and addiction messages, youth culture, and lifestyle themes. Posts were rated promotional incluced branded content, URLs linking to commercial websites, and hashtags indicating affiliations with commercial sites.

Nicotine/addiction posts contained “references to nicotine, including compatible pod-related brand names and nicotine content, as well as any references to addiction or nicotine dependence (e.g., daily use, being an addict, junkie, “nichead,” fiend, maniac), or effects of nicotine use (e.g., “buzz”).

Youth-themed posts included stylistic features such as jargon or slang, acronyms common among youth (e.g., di4j, doit4juul), youth-oriented cartoons, JUUL wrap imagery, youth entertainment, and music. Posts with references to school, the classroom, and other places frequented by youth and youth social networks, family, and peers were included in the youth-themed category.

Lifestyle content referenced "social norms and acceptability-related messages contained any mentions of online or offline communitiesand peer groups (eg, collegelife, juulgirls, juulgang, vapeusa, collegedaily, vapelyfe hashtags) as well as JUUL use during social activities, events, social acceptance of JUULing and any mentions of JUULing as a characteristic of cultural or social identity."

Content analysis of the posts found that 34.3% were promotional, 11% referenced nicotine and addiction themes, and 55.4% featured youth-oriented cultural themes, and 57% featured lifestyle themes. There was overlap among the categories, for example, the 71.9% of the promotional posts had lifestyle messages included and 86.3% of the nicotine/addiction posts contained lifestyle elements. The promotional posts also contained some hashtags referencing cannabis (#420, #710).

An additional feature of the promotional posts is the incentivizing messages. “More than more than a third of JUUL-related posts containing overt promotional content that highlights ways to obtain products at reduced cost, such as giveaways and incentivized friend-tagging. This finding is consistent with previous research which found that Twitter users employed person-tagging (e.g., @username) when purchasing JUUL, suggesting friend-tagging plays an important role in motivating product use,” the researchers wrote.

The study was limited by the short time frame, the analysis of Instagram postings only, and the limitation of only 50 hashtags. These limitations may result in underreporting of the amount of JUUL-related social media messaging that targets youth. In addition, the investigators did not analyze the origin of accounts or the identity of the individuals creating the content.

“The results of this study demonstrate the reach of organic posts that contain JUUL-related content, and posts by third-party vendors of vaping products, who continue to push explicitly youth-targeted advertisements for JUUL and similar e-cigarette products under JUUL-related hashtags,” Dr. Hair wrote. “Our research and studies done by others in the field are one way to build the evidence base to advocate for stricter social media marketing restrictions on tobacco products that are applicable to all players in the field.”

She added that the Food and Drug Administration should use its power to restrict e-cigarette manufacturers from using social media to market to young people. “We also think that social media platforms should do more to adopt and enforce strong and well-enforced policies against the promotion of any tobacco products to young adults,” she concluded.

The study was sponsored by the Truth Initiative. The Truth Initiative was created as a part of the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) that was negotiated between the tobacco industry and 46 states and the District of Columbia in 1998. The MSA created the American Legacy Foundation (now known as the Truth Initiative), a nonprofit research and educational organization that focuses its efforts on preventing teen smoking and encouraging smokers to quit.

SOURCE: Czaplicki L et al. Tob Control. 2019 Jul 2; doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054824.

This article was updated 7/17/2019.

with targeted messages and images, a study of e-cigarette promotion has found.

In 2018, the JUUL company declared a commitment to support efforts to raise the age of legal purchase of tobacco to age 21 years in all U.S. states. In addition, JUUL deleted its official Facebook and Instagram accounts in November 2018, but the promotion of these products has continued through affiliated marketing campaigns from other online vendors.

Vaping among teens has shot up in popularity in recent years. The prevalence of vaping among young people aged 16-19 years has been estimated at 16% in 2018, up from 11% in 2017 (BMJ. 2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.12219. A study published in JAMA Pediatrics (2019;173[7]:690-92) found that an estimated 81% of users following a popular Twitter account (@JUULvapor) were aged 13-20 years, with 45% in the 13-17 year age range.

Elizabeth C. Hair, PhD, senior vice president of the Truth Initiative Schroeder Institute, and a team of investigators conducted a study of the “proliferation of JUUL-related content across four themes over a 3-month period: overt promotional content, nicotine and addiction-related content, lifestyle content, and content related to youth culture.” The study appeared online in Tobacco Control (2019 Jul 2; doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054824).

The investigators did a content analysis of social media posts on Instagram related to JUUL and JUUL-like products from March 1 to May 15, 2018. Hash-tag keyword queries of JUUL-related posts on Instagram were collected from the Instagram application programming interface through NUVI, a licensed syndicator of the Instagram firehose. The researchers used 50 hashtags to capture and enumerate individual posts. Examples of the hashtags used are #juul, #juuling, #juulvapor, #juulpod, #switchtojuul, and #juulgang. All posts were included from the official JUUL account and JUUL-related accounts with the highest number of followers at the time of data collection (e.g., @juulcentral, @juulnation, @juul_university, @juul.girls).

The search identified 14,838 posts by 5,201 unique users that featured content relating to product promotion, nicotine and addiction messages, youth culture, and lifestyle themes. Posts were rated promotional incluced branded content, URLs linking to commercial websites, and hashtags indicating affiliations with commercial sites.

Nicotine/addiction posts contained “references to nicotine, including compatible pod-related brand names and nicotine content, as well as any references to addiction or nicotine dependence (e.g., daily use, being an addict, junkie, “nichead,” fiend, maniac), or effects of nicotine use (e.g., “buzz”).

Youth-themed posts included stylistic features such as jargon or slang, acronyms common among youth (e.g., di4j, doit4juul), youth-oriented cartoons, JUUL wrap imagery, youth entertainment, and music. Posts with references to school, the classroom, and other places frequented by youth and youth social networks, family, and peers were included in the youth-themed category.

Lifestyle content referenced "social norms and acceptability-related messages contained any mentions of online or offline communitiesand peer groups (eg, collegelife, juulgirls, juulgang, vapeusa, collegedaily, vapelyfe hashtags) as well as JUUL use during social activities, events, social acceptance of JUULing and any mentions of JUULing as a characteristic of cultural or social identity."

Content analysis of the posts found that 34.3% were promotional, 11% referenced nicotine and addiction themes, and 55.4% featured youth-oriented cultural themes, and 57% featured lifestyle themes. There was overlap among the categories, for example, the 71.9% of the promotional posts had lifestyle messages included and 86.3% of the nicotine/addiction posts contained lifestyle elements. The promotional posts also contained some hashtags referencing cannabis (#420, #710).

An additional feature of the promotional posts is the incentivizing messages. “More than more than a third of JUUL-related posts containing overt promotional content that highlights ways to obtain products at reduced cost, such as giveaways and incentivized friend-tagging. This finding is consistent with previous research which found that Twitter users employed person-tagging (e.g., @username) when purchasing JUUL, suggesting friend-tagging plays an important role in motivating product use,” the researchers wrote.

The study was limited by the short time frame, the analysis of Instagram postings only, and the limitation of only 50 hashtags. These limitations may result in underreporting of the amount of JUUL-related social media messaging that targets youth. In addition, the investigators did not analyze the origin of accounts or the identity of the individuals creating the content.

“The results of this study demonstrate the reach of organic posts that contain JUUL-related content, and posts by third-party vendors of vaping products, who continue to push explicitly youth-targeted advertisements for JUUL and similar e-cigarette products under JUUL-related hashtags,” Dr. Hair wrote. “Our research and studies done by others in the field are one way to build the evidence base to advocate for stricter social media marketing restrictions on tobacco products that are applicable to all players in the field.”

She added that the Food and Drug Administration should use its power to restrict e-cigarette manufacturers from using social media to market to young people. “We also think that social media platforms should do more to adopt and enforce strong and well-enforced policies against the promotion of any tobacco products to young adults,” she concluded.

The study was sponsored by the Truth Initiative. The Truth Initiative was created as a part of the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) that was negotiated between the tobacco industry and 46 states and the District of Columbia in 1998. The MSA created the American Legacy Foundation (now known as the Truth Initiative), a nonprofit research and educational organization that focuses its efforts on preventing teen smoking and encouraging smokers to quit.

SOURCE: Czaplicki L et al. Tob Control. 2019 Jul 2; doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054824.

This article was updated 7/17/2019.

with targeted messages and images, a study of e-cigarette promotion has found.

In 2018, the JUUL company declared a commitment to support efforts to raise the age of legal purchase of tobacco to age 21 years in all U.S. states. In addition, JUUL deleted its official Facebook and Instagram accounts in November 2018, but the promotion of these products has continued through affiliated marketing campaigns from other online vendors.

Vaping among teens has shot up in popularity in recent years. The prevalence of vaping among young people aged 16-19 years has been estimated at 16% in 2018, up from 11% in 2017 (BMJ. 2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.12219. A study published in JAMA Pediatrics (2019;173[7]:690-92) found that an estimated 81% of users following a popular Twitter account (@JUULvapor) were aged 13-20 years, with 45% in the 13-17 year age range.

Elizabeth C. Hair, PhD, senior vice president of the Truth Initiative Schroeder Institute, and a team of investigators conducted a study of the “proliferation of JUUL-related content across four themes over a 3-month period: overt promotional content, nicotine and addiction-related content, lifestyle content, and content related to youth culture.” The study appeared online in Tobacco Control (2019 Jul 2; doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054824).

The investigators did a content analysis of social media posts on Instagram related to JUUL and JUUL-like products from March 1 to May 15, 2018. Hash-tag keyword queries of JUUL-related posts on Instagram were collected from the Instagram application programming interface through NUVI, a licensed syndicator of the Instagram firehose. The researchers used 50 hashtags to capture and enumerate individual posts. Examples of the hashtags used are #juul, #juuling, #juulvapor, #juulpod, #switchtojuul, and #juulgang. All posts were included from the official JUUL account and JUUL-related accounts with the highest number of followers at the time of data collection (e.g., @juulcentral, @juulnation, @juul_university, @juul.girls).

The search identified 14,838 posts by 5,201 unique users that featured content relating to product promotion, nicotine and addiction messages, youth culture, and lifestyle themes. Posts were rated promotional incluced branded content, URLs linking to commercial websites, and hashtags indicating affiliations with commercial sites.

Nicotine/addiction posts contained “references to nicotine, including compatible pod-related brand names and nicotine content, as well as any references to addiction or nicotine dependence (e.g., daily use, being an addict, junkie, “nichead,” fiend, maniac), or effects of nicotine use (e.g., “buzz”).

Youth-themed posts included stylistic features such as jargon or slang, acronyms common among youth (e.g., di4j, doit4juul), youth-oriented cartoons, JUUL wrap imagery, youth entertainment, and music. Posts with references to school, the classroom, and other places frequented by youth and youth social networks, family, and peers were included in the youth-themed category.

Lifestyle content referenced "social norms and acceptability-related messages contained any mentions of online or offline communitiesand peer groups (eg, collegelife, juulgirls, juulgang, vapeusa, collegedaily, vapelyfe hashtags) as well as JUUL use during social activities, events, social acceptance of JUULing and any mentions of JUULing as a characteristic of cultural or social identity."

Content analysis of the posts found that 34.3% were promotional, 11% referenced nicotine and addiction themes, and 55.4% featured youth-oriented cultural themes, and 57% featured lifestyle themes. There was overlap among the categories, for example, the 71.9% of the promotional posts had lifestyle messages included and 86.3% of the nicotine/addiction posts contained lifestyle elements. The promotional posts also contained some hashtags referencing cannabis (#420, #710).

An additional feature of the promotional posts is the incentivizing messages. “More than more than a third of JUUL-related posts containing overt promotional content that highlights ways to obtain products at reduced cost, such as giveaways and incentivized friend-tagging. This finding is consistent with previous research which found that Twitter users employed person-tagging (e.g., @username) when purchasing JUUL, suggesting friend-tagging plays an important role in motivating product use,” the researchers wrote.

The study was limited by the short time frame, the analysis of Instagram postings only, and the limitation of only 50 hashtags. These limitations may result in underreporting of the amount of JUUL-related social media messaging that targets youth. In addition, the investigators did not analyze the origin of accounts or the identity of the individuals creating the content.

“The results of this study demonstrate the reach of organic posts that contain JUUL-related content, and posts by third-party vendors of vaping products, who continue to push explicitly youth-targeted advertisements for JUUL and similar e-cigarette products under JUUL-related hashtags,” Dr. Hair wrote. “Our research and studies done by others in the field are one way to build the evidence base to advocate for stricter social media marketing restrictions on tobacco products that are applicable to all players in the field.”

She added that the Food and Drug Administration should use its power to restrict e-cigarette manufacturers from using social media to market to young people. “We also think that social media platforms should do more to adopt and enforce strong and well-enforced policies against the promotion of any tobacco products to young adults,” she concluded.

The study was sponsored by the Truth Initiative. The Truth Initiative was created as a part of the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) that was negotiated between the tobacco industry and 46 states and the District of Columbia in 1998. The MSA created the American Legacy Foundation (now known as the Truth Initiative), a nonprofit research and educational organization that focuses its efforts on preventing teen smoking and encouraging smokers to quit.

SOURCE: Czaplicki L et al. Tob Control. 2019 Jul 2; doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054824.

This article was updated 7/17/2019.

FROM TOBACCO CONTROL

Medicare going in ‘right direction’ on opioid epidemic

About 174,000 Medicare beneficiaries received such a medication – either buprenorphine or naltrexone – to help them with recovery in 2018, according to the Office of Inspector General in the Department of Health & Human Services.

In addition, prescriptions for naloxone – the drug that can reverse an opioid overdose – spiked since 2016, rising 501% – and that is likely an underestimate because it doesn’t include doses of the nasal spray Medicare members might have received through local programs, the OIG said.

“For now, the numbers are going in the right direction,” said Miriam Anderson, lead investigator on the report. “But this is a national crisis and we must remain vigilant and continue to fight this epidemic and ensure that opioids are prescribed and used appropriately.”

During the 2 years studied, the threat of new addictions appeared to slow. Prescriptions for an opioid through Medicare Part D decreased by 11%. The numbers of the beneficiaries considered at serious risk for misuse or overdose ― either because they received extreme amounts of opioids or appeared to be “doctor shopping” – dropped 46%. And there were 51% fewer doctors or other providers flagged for prescribing opioids to patients at serious risk from 2016 to 2018.

The report says the OIG and other law enforcement agencies will investigate the highest-level prescribers for possible fraud and signs that some providers operate pill mills. The report mentions a physician in Florida who provided 104 high-risk Medicare patients with 2,619 opioid prescriptions.

It will be up to Medicare to follow up with patients whose opioid use suggests addiction, recreational use, or resale. In one case, a Pennsylvania woman received 10,728 oxycodone pills and 570 fentanyl patches from a single physician during 2018. A Medicare member in Alabama acquired 56 opioid prescriptions from 25 different prescribers within 1 year.

In a statement, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said: “Fighting the opioid epidemic has been a top priority for the Trump administration. We are encouraged by the OIG’s conclusion which finds significant progress has been made in our efforts to decrease opioid misuse while simultaneously increasing medication-assisted treatment in the Medicare Part D program.”

The agency points to recent efforts to curb opioid misuse including a 7-day limit on first-time opioid prescriptions, pharmacy alerts about Medicare beneficiaries who receive high doses of pain medication, and drug management programs that may restrict a patient’s supply. CMS says it does not use a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Medicare patients in long-term care facilities or hospice care and those in cancer treatment are exempt from the opioid-prescribing restrictions.

The opioid-prescribing limits are raising alarms among some Medicare recipients, especially those who qualify based on a long-term disability and deal with severe, chronic pain.

Jae Kennedy, PhD, a disability policy expert at Washington State University, Spokane, said cutting back on opioid prescriptions is generally a good development.

“But we hear from people in the disability community who feel like they’re being victimized by this new, very stringent set of dispensing limits,” said Dr. Kennedy. “People have been managing their pain, in some cases for many years without a problem, and now they’re being kind of criminalized by this new bureaucratic backlash.”

Ms. Anderson said the OIG agrees that “some patients need opioids and they should receive those needed for their condition. This report raises concerns that some patients may be receiving opioids above and beyond those needs.”

While most Medicare beneficiaries are 65 years or older, the 15% who are under 65 and disabled may be the key piece of this report. Dr. Kennedy’s research shows they are up to three times more likely to describe persistent pain than are other adults and 50% more likely to report opioid misuse. A 2017 OIG report found that 74% of Medicare beneficiaries at serious risk for addiction and overdose deaths were under age 65 years.

Dr. Kennedy said it’s good to see Medicare expanding access to medication-assisted treatment, known as MAT, for addiction, but the agency needs to make sure that more buprenorphine prescribers accept all patients, not just the ones who are easiest to manage. Patients with disabilities often need many different medications for multiple physical and mental health conditions.

“Saying, ‘Well, because you’ve got schizophrenia or manic depressive disorder, we can’t treat you,’ I think is discriminatory,” Dr. Kennedy said. “It’s happening with private buprenorphine prescribers in this country because there are so few.”

Americans 65 years or older have the lowest rates of opioid overdose deaths. Even so, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says the number of deaths among seniors increased by 279% from 1999 to 2017.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. WBUR, a public radio station owned by Boston University, is a member station of NPR.

About 174,000 Medicare beneficiaries received such a medication – either buprenorphine or naltrexone – to help them with recovery in 2018, according to the Office of Inspector General in the Department of Health & Human Services.

In addition, prescriptions for naloxone – the drug that can reverse an opioid overdose – spiked since 2016, rising 501% – and that is likely an underestimate because it doesn’t include doses of the nasal spray Medicare members might have received through local programs, the OIG said.

“For now, the numbers are going in the right direction,” said Miriam Anderson, lead investigator on the report. “But this is a national crisis and we must remain vigilant and continue to fight this epidemic and ensure that opioids are prescribed and used appropriately.”

During the 2 years studied, the threat of new addictions appeared to slow. Prescriptions for an opioid through Medicare Part D decreased by 11%. The numbers of the beneficiaries considered at serious risk for misuse or overdose ― either because they received extreme amounts of opioids or appeared to be “doctor shopping” – dropped 46%. And there were 51% fewer doctors or other providers flagged for prescribing opioids to patients at serious risk from 2016 to 2018.

The report says the OIG and other law enforcement agencies will investigate the highest-level prescribers for possible fraud and signs that some providers operate pill mills. The report mentions a physician in Florida who provided 104 high-risk Medicare patients with 2,619 opioid prescriptions.

It will be up to Medicare to follow up with patients whose opioid use suggests addiction, recreational use, or resale. In one case, a Pennsylvania woman received 10,728 oxycodone pills and 570 fentanyl patches from a single physician during 2018. A Medicare member in Alabama acquired 56 opioid prescriptions from 25 different prescribers within 1 year.

In a statement, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said: “Fighting the opioid epidemic has been a top priority for the Trump administration. We are encouraged by the OIG’s conclusion which finds significant progress has been made in our efforts to decrease opioid misuse while simultaneously increasing medication-assisted treatment in the Medicare Part D program.”

The agency points to recent efforts to curb opioid misuse including a 7-day limit on first-time opioid prescriptions, pharmacy alerts about Medicare beneficiaries who receive high doses of pain medication, and drug management programs that may restrict a patient’s supply. CMS says it does not use a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Medicare patients in long-term care facilities or hospice care and those in cancer treatment are exempt from the opioid-prescribing restrictions.

The opioid-prescribing limits are raising alarms among some Medicare recipients, especially those who qualify based on a long-term disability and deal with severe, chronic pain.

Jae Kennedy, PhD, a disability policy expert at Washington State University, Spokane, said cutting back on opioid prescriptions is generally a good development.

“But we hear from people in the disability community who feel like they’re being victimized by this new, very stringent set of dispensing limits,” said Dr. Kennedy. “People have been managing their pain, in some cases for many years without a problem, and now they’re being kind of criminalized by this new bureaucratic backlash.”

Ms. Anderson said the OIG agrees that “some patients need opioids and they should receive those needed for their condition. This report raises concerns that some patients may be receiving opioids above and beyond those needs.”

While most Medicare beneficiaries are 65 years or older, the 15% who are under 65 and disabled may be the key piece of this report. Dr. Kennedy’s research shows they are up to three times more likely to describe persistent pain than are other adults and 50% more likely to report opioid misuse. A 2017 OIG report found that 74% of Medicare beneficiaries at serious risk for addiction and overdose deaths were under age 65 years.

Dr. Kennedy said it’s good to see Medicare expanding access to medication-assisted treatment, known as MAT, for addiction, but the agency needs to make sure that more buprenorphine prescribers accept all patients, not just the ones who are easiest to manage. Patients with disabilities often need many different medications for multiple physical and mental health conditions.

“Saying, ‘Well, because you’ve got schizophrenia or manic depressive disorder, we can’t treat you,’ I think is discriminatory,” Dr. Kennedy said. “It’s happening with private buprenorphine prescribers in this country because there are so few.”

Americans 65 years or older have the lowest rates of opioid overdose deaths. Even so, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says the number of deaths among seniors increased by 279% from 1999 to 2017.