User login

In methamphetamine use disorder, consider off-label drugs

SAN DIEGO – Its toll is obscured by the opioid crisis, but methamphetamine use is on the rise in the United States. There are no approved treatments for methamphetamine use, but a psychiatrist told colleagues that several off-label medications might prove helpful.

However, the evidence supporting the use of these medications for patients taking methamphetamine is not robust, “and none are even close to [Food and Drug Administration] approval,” said Larissa J. Mooney, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. “But if I use something that’s approved for depression or might be helpful for anxiety symptoms, maybe it would also help reduce their likelihood of relapse in conjunction with an evidence-based behavioral program or treatment with a therapist.”

Dr. Mooney, who spoke at the annual Psych Congress, highlighted a federal report estimating that 0.4% of people aged 18-25 in 2017 used the drug within the past month, compared with 0.3% of those aged 26 and higher.

There were about 758,000 current adult users of methamphetamine in 2017, the report found.

Meanwhile, (Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018 Dec 1;193:14-20). And, Dr. Mooney said, deaths from stimulants are rising, even independent of opioid deaths.

Stimulant users typically have other psychiatric conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and concentration problems, Dr. Mooney said. In those cases, she said, treating those conditions might help with the substance use, too.

For methamphetamine use disorder, she highlighted some medications that might be helpful, although, again, she cautioned that evidence is not strong:

- Bupropion (Wellbutrin). Research suggests that this drug is more effective in patients with less severe methamphetamine use disorder, Dr. Mooney said. “It’s a more stimulating antidepressant, and can be helpful with concentration and attention.”

- Mirtazapine (Remeron). “I keep it in my list of options for some [who are] really anxious and not sleeping well,” she said. “It might be beneficial.”

- Naltrexone (ReVia, Depade, Vivitrol). “There are some early signs of efficacy,” she said, and a randomized, controlled trial is in progress.

- Methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta) and topiramate (Topamax). There’s “low-strength” evidence that the drugs can be helpful and lower use of methamphetamine, she said. However, methylphenidate is a stimulant. There’s controversy over the use of stimulants to treat patients with substance use disorders, Dr. Mooney said, and she tends to be conservative about their use in this population.

Why not use them to treat methamphetamine users in the same way that opioids such as methadone are used to treat opioid use addiction? “We don’t have an equivalent stimulant that works in the same way,” she said. “They don’t stay in the system for 24 hours. If you take a prescription stimulant, by the end of the day it wears off. It won’t stay in the same way as agonist treatments for opioid disorder.”

Even so, she said, “it makes sense that stimulants might be helpful.”

Dr. Mooney disclosed an advisory board relationship with Alkermes and grant/research support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

SAN DIEGO – Its toll is obscured by the opioid crisis, but methamphetamine use is on the rise in the United States. There are no approved treatments for methamphetamine use, but a psychiatrist told colleagues that several off-label medications might prove helpful.

However, the evidence supporting the use of these medications for patients taking methamphetamine is not robust, “and none are even close to [Food and Drug Administration] approval,” said Larissa J. Mooney, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. “But if I use something that’s approved for depression or might be helpful for anxiety symptoms, maybe it would also help reduce their likelihood of relapse in conjunction with an evidence-based behavioral program or treatment with a therapist.”

Dr. Mooney, who spoke at the annual Psych Congress, highlighted a federal report estimating that 0.4% of people aged 18-25 in 2017 used the drug within the past month, compared with 0.3% of those aged 26 and higher.

There were about 758,000 current adult users of methamphetamine in 2017, the report found.

Meanwhile, (Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018 Dec 1;193:14-20). And, Dr. Mooney said, deaths from stimulants are rising, even independent of opioid deaths.

Stimulant users typically have other psychiatric conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and concentration problems, Dr. Mooney said. In those cases, she said, treating those conditions might help with the substance use, too.

For methamphetamine use disorder, she highlighted some medications that might be helpful, although, again, she cautioned that evidence is not strong:

- Bupropion (Wellbutrin). Research suggests that this drug is more effective in patients with less severe methamphetamine use disorder, Dr. Mooney said. “It’s a more stimulating antidepressant, and can be helpful with concentration and attention.”

- Mirtazapine (Remeron). “I keep it in my list of options for some [who are] really anxious and not sleeping well,” she said. “It might be beneficial.”

- Naltrexone (ReVia, Depade, Vivitrol). “There are some early signs of efficacy,” she said, and a randomized, controlled trial is in progress.

- Methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta) and topiramate (Topamax). There’s “low-strength” evidence that the drugs can be helpful and lower use of methamphetamine, she said. However, methylphenidate is a stimulant. There’s controversy over the use of stimulants to treat patients with substance use disorders, Dr. Mooney said, and she tends to be conservative about their use in this population.

Why not use them to treat methamphetamine users in the same way that opioids such as methadone are used to treat opioid use addiction? “We don’t have an equivalent stimulant that works in the same way,” she said. “They don’t stay in the system for 24 hours. If you take a prescription stimulant, by the end of the day it wears off. It won’t stay in the same way as agonist treatments for opioid disorder.”

Even so, she said, “it makes sense that stimulants might be helpful.”

Dr. Mooney disclosed an advisory board relationship with Alkermes and grant/research support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

SAN DIEGO – Its toll is obscured by the opioid crisis, but methamphetamine use is on the rise in the United States. There are no approved treatments for methamphetamine use, but a psychiatrist told colleagues that several off-label medications might prove helpful.

However, the evidence supporting the use of these medications for patients taking methamphetamine is not robust, “and none are even close to [Food and Drug Administration] approval,” said Larissa J. Mooney, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. “But if I use something that’s approved for depression or might be helpful for anxiety symptoms, maybe it would also help reduce their likelihood of relapse in conjunction with an evidence-based behavioral program or treatment with a therapist.”

Dr. Mooney, who spoke at the annual Psych Congress, highlighted a federal report estimating that 0.4% of people aged 18-25 in 2017 used the drug within the past month, compared with 0.3% of those aged 26 and higher.

There were about 758,000 current adult users of methamphetamine in 2017, the report found.

Meanwhile, (Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018 Dec 1;193:14-20). And, Dr. Mooney said, deaths from stimulants are rising, even independent of opioid deaths.

Stimulant users typically have other psychiatric conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and concentration problems, Dr. Mooney said. In those cases, she said, treating those conditions might help with the substance use, too.

For methamphetamine use disorder, she highlighted some medications that might be helpful, although, again, she cautioned that evidence is not strong:

- Bupropion (Wellbutrin). Research suggests that this drug is more effective in patients with less severe methamphetamine use disorder, Dr. Mooney said. “It’s a more stimulating antidepressant, and can be helpful with concentration and attention.”

- Mirtazapine (Remeron). “I keep it in my list of options for some [who are] really anxious and not sleeping well,” she said. “It might be beneficial.”

- Naltrexone (ReVia, Depade, Vivitrol). “There are some early signs of efficacy,” she said, and a randomized, controlled trial is in progress.

- Methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta) and topiramate (Topamax). There’s “low-strength” evidence that the drugs can be helpful and lower use of methamphetamine, she said. However, methylphenidate is a stimulant. There’s controversy over the use of stimulants to treat patients with substance use disorders, Dr. Mooney said, and she tends to be conservative about their use in this population.

Why not use them to treat methamphetamine users in the same way that opioids such as methadone are used to treat opioid use addiction? “We don’t have an equivalent stimulant that works in the same way,” she said. “They don’t stay in the system for 24 hours. If you take a prescription stimulant, by the end of the day it wears off. It won’t stay in the same way as agonist treatments for opioid disorder.”

Even so, she said, “it makes sense that stimulants might be helpful.”

Dr. Mooney disclosed an advisory board relationship with Alkermes and grant/research support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

REPORTING FROM PSYCH CONGRESS 2019

Dismantling the opioid crisis

Dr. John Hickner’s editorial, “Doing our part to dismantle the opioid crisis” (J Fam Pract 2019;68:308) had important inaccuracies.

The Joint Commission, for which I serve as an executive vice president, did not “dub pain assessment the ‘fifth vital sign’. ” The concept of the fifth vital sign was developed by the American Pain Society in the 1990s.1 It gained national attention through a Veterans Health Administration initiative in 1999.2 And in 2001, the Joint Commission (then the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations or JCAHO) issued its Pain Standards.

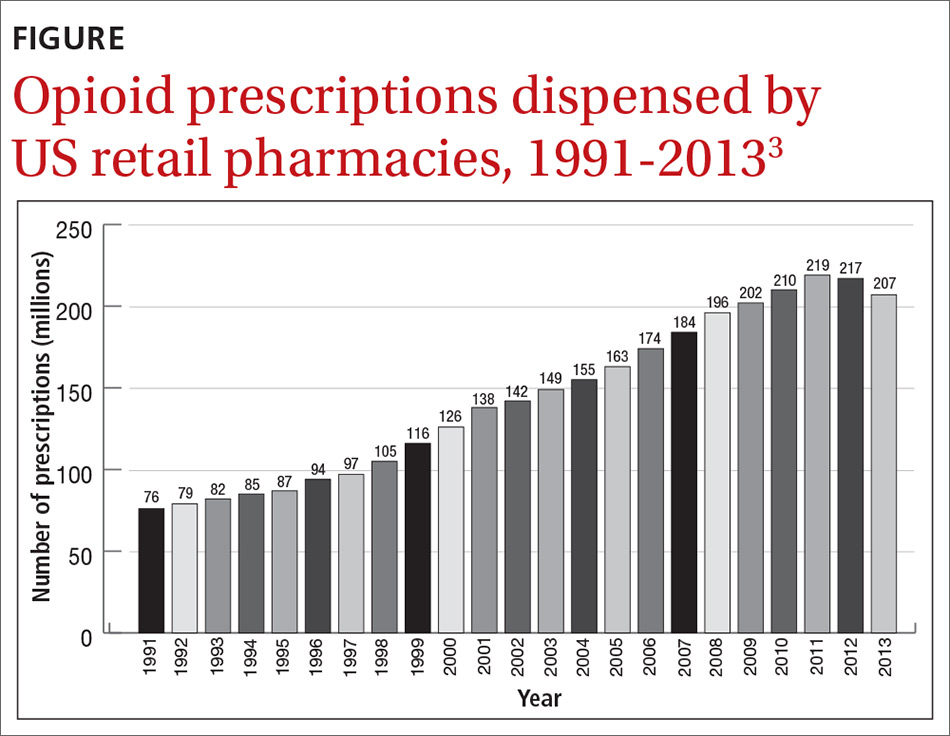

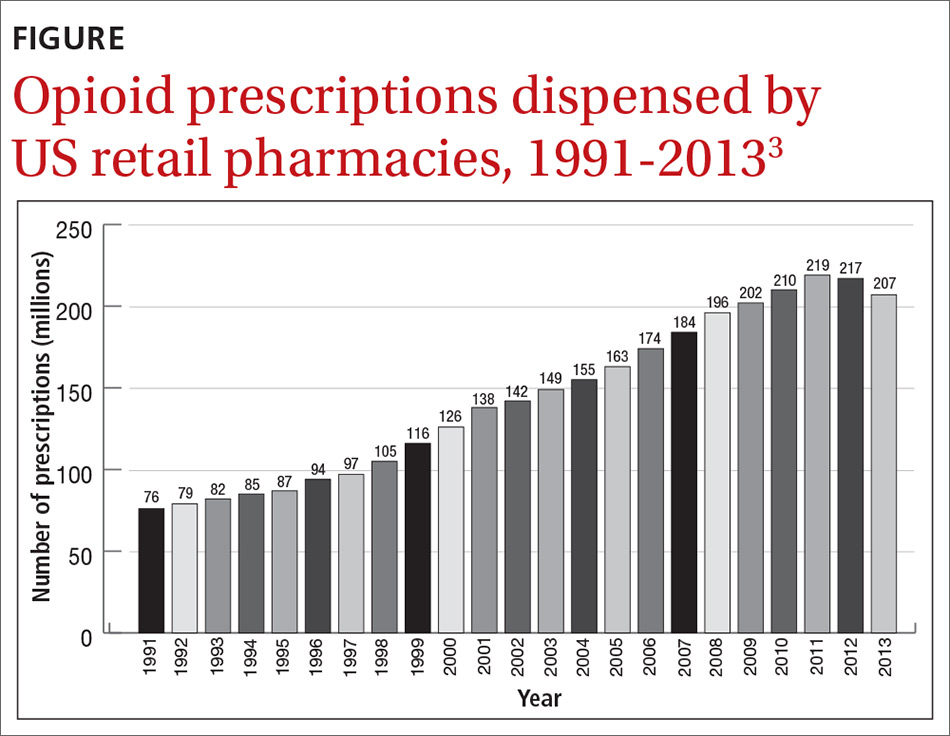

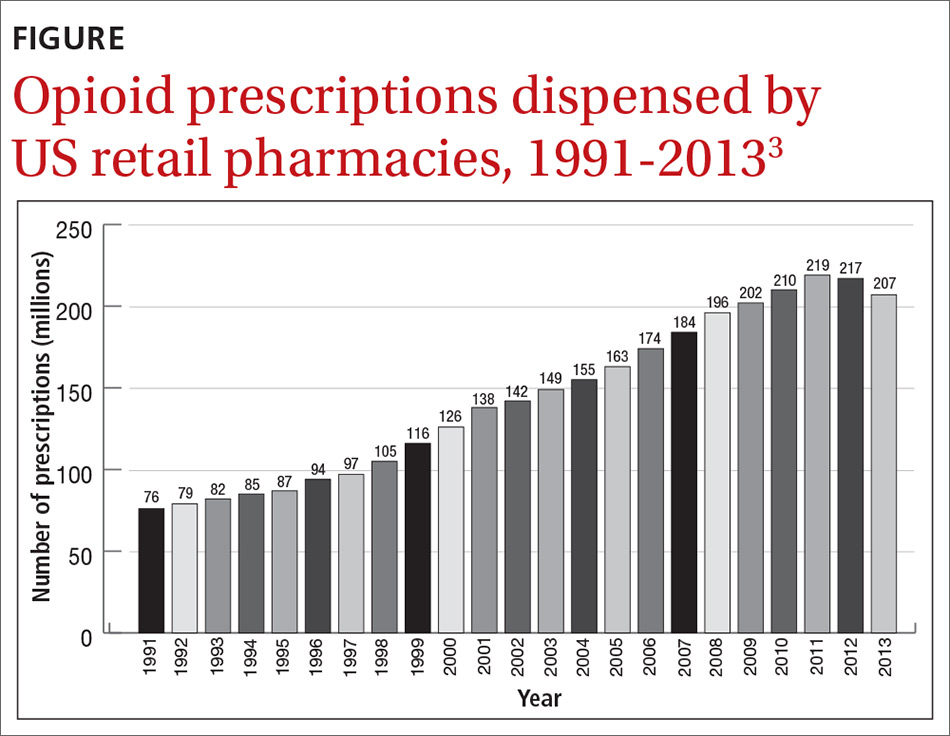

Dr. Hickner wrote that the push to assess for pain as the fifth vital sign was a central cause of the opioid epidemic; however, this is contrary to published data on the epidemic. Total opioid prescriptions had been steadily increasing in the United States for at least a decade before the Pain Standards went into effect in 2001 (FIGURE).3 Between 1991 and 1997, the number of prescriptions increased from 76 million to 97 million. The rate of increase from 1997 to 2011 appears to have been more rapid, which is likely due to the 1995 approval of the new sustained-release opioid OxyContin and the associated aggressive marketing campaigns to physicians.

Your readers should know that we, at the Joint Commission, are also “doing our part to dismantle the opioid crisis.” In 2016, we completely revised our Pain Standards, adding new criteria to help address the epidemic. Some adjustments include: requiring improved availability of nonpharmacologic therapy, encouraging engagement of patients in pain management plans, enhancing accessibility of Physician Drug Monitoring Program tools, and monitoring opioid prescribing.

David W. Baker, MD, FACP, executive vice president

The Joint Commission, Oakbrook Terrace, IL

1. American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Chronic Cancer Pain. 2nd ed. Skokie, Illinois: American Pain Society; 1989.

2. Department of Veteran’s Affairs. Pain: the fifth vital sign. www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/docs/Pain_As_the_5th_Vital_Sign_Toolkit.pdf. Published October 2000. Accessed September 30, 2019.

3 National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s addiction to opioids: heroin and prescription drug abuse. https://archives.drugabuse.gov/testimonies/2014/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse. Published May 14, 2014. Accessed September 30, 2019.

Dr. John Hickner’s editorial, “Doing our part to dismantle the opioid crisis” (J Fam Pract 2019;68:308) had important inaccuracies.

The Joint Commission, for which I serve as an executive vice president, did not “dub pain assessment the ‘fifth vital sign’. ” The concept of the fifth vital sign was developed by the American Pain Society in the 1990s.1 It gained national attention through a Veterans Health Administration initiative in 1999.2 And in 2001, the Joint Commission (then the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations or JCAHO) issued its Pain Standards.

Dr. Hickner wrote that the push to assess for pain as the fifth vital sign was a central cause of the opioid epidemic; however, this is contrary to published data on the epidemic. Total opioid prescriptions had been steadily increasing in the United States for at least a decade before the Pain Standards went into effect in 2001 (FIGURE).3 Between 1991 and 1997, the number of prescriptions increased from 76 million to 97 million. The rate of increase from 1997 to 2011 appears to have been more rapid, which is likely due to the 1995 approval of the new sustained-release opioid OxyContin and the associated aggressive marketing campaigns to physicians.

Your readers should know that we, at the Joint Commission, are also “doing our part to dismantle the opioid crisis.” In 2016, we completely revised our Pain Standards, adding new criteria to help address the epidemic. Some adjustments include: requiring improved availability of nonpharmacologic therapy, encouraging engagement of patients in pain management plans, enhancing accessibility of Physician Drug Monitoring Program tools, and monitoring opioid prescribing.

David W. Baker, MD, FACP, executive vice president

The Joint Commission, Oakbrook Terrace, IL

Dr. John Hickner’s editorial, “Doing our part to dismantle the opioid crisis” (J Fam Pract 2019;68:308) had important inaccuracies.

The Joint Commission, for which I serve as an executive vice president, did not “dub pain assessment the ‘fifth vital sign’. ” The concept of the fifth vital sign was developed by the American Pain Society in the 1990s.1 It gained national attention through a Veterans Health Administration initiative in 1999.2 And in 2001, the Joint Commission (then the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations or JCAHO) issued its Pain Standards.

Dr. Hickner wrote that the push to assess for pain as the fifth vital sign was a central cause of the opioid epidemic; however, this is contrary to published data on the epidemic. Total opioid prescriptions had been steadily increasing in the United States for at least a decade before the Pain Standards went into effect in 2001 (FIGURE).3 Between 1991 and 1997, the number of prescriptions increased from 76 million to 97 million. The rate of increase from 1997 to 2011 appears to have been more rapid, which is likely due to the 1995 approval of the new sustained-release opioid OxyContin and the associated aggressive marketing campaigns to physicians.

Your readers should know that we, at the Joint Commission, are also “doing our part to dismantle the opioid crisis.” In 2016, we completely revised our Pain Standards, adding new criteria to help address the epidemic. Some adjustments include: requiring improved availability of nonpharmacologic therapy, encouraging engagement of patients in pain management plans, enhancing accessibility of Physician Drug Monitoring Program tools, and monitoring opioid prescribing.

David W. Baker, MD, FACP, executive vice president

The Joint Commission, Oakbrook Terrace, IL

1. American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Chronic Cancer Pain. 2nd ed. Skokie, Illinois: American Pain Society; 1989.

2. Department of Veteran’s Affairs. Pain: the fifth vital sign. www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/docs/Pain_As_the_5th_Vital_Sign_Toolkit.pdf. Published October 2000. Accessed September 30, 2019.

3 National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s addiction to opioids: heroin and prescription drug abuse. https://archives.drugabuse.gov/testimonies/2014/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse. Published May 14, 2014. Accessed September 30, 2019.

1. American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Chronic Cancer Pain. 2nd ed. Skokie, Illinois: American Pain Society; 1989.

2. Department of Veteran’s Affairs. Pain: the fifth vital sign. www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/docs/Pain_As_the_5th_Vital_Sign_Toolkit.pdf. Published October 2000. Accessed September 30, 2019.

3 National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s addiction to opioids: heroin and prescription drug abuse. https://archives.drugabuse.gov/testimonies/2014/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse. Published May 14, 2014. Accessed September 30, 2019.

SUDs are almost always comorbid with other disorders

SAN DIEGO – Substance use disorders rarely ride alone, a psychiatrist told colleagues, and it’s crucial to treat the accompanying mental illness that is almost always present.

“If you’re really depressed and you’re smoking marijuana, the smoking could have made it worse, but you were probably depressed before,” said Timothy E. Wilens, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston. Dr. Wilens spoke at the annual Psych Congress.

He pointed to numbers supporting the link between substance use and mental illness. He also offered several tips about treating substance use disorder (SUD).

In ADHD, consider the big picture. If a person has both ADHD and SUD, treat both if the level of substance abuse is lower. But focus on the SUD in more severe cases, he said, and realize that “most likely your treatment for ADHD isn’t going to work as well.”

The same goes for the anxiolytic buspirone (Buspar) in patients with depression and SUD.

Consider N-acetyl cysteine in cannabis use disorder. N-acetyl cysteine, a nutraceutical used as an asthma medication, has shown promise in trials as a treatment for cannabis use disorder, Dr. Wilens said. It helps patients avoid the temptation to smoke. “They won’t say they’ve lost all their cravings, but you’ll hear, ‘I just didn’t need to do it; I’m not smoking as much.’ If you hear that from your patients, you know it’s working. It’s a subtle effect, but it can help.”

Scamming’ drugs shouldn’t be your main worry. Substance use research suggests that users of pharmaceutical drugs for nonmedical uses rarely get them directly from practitioners (7%), but instead mainly get them through friends, Dr. Wilens said. “If you work with this population and treat ADHD or anxiety, you’re paranoid that everyone coming in wants to scam medicines. Be more concerned about oversupplying them with immediate-release medications and not [taking] them to task about keeping the medication safely stored.”

Interventions such as Alcoholics Anonymous are as “effective as any other treatment for substance abuse, and it’s not costly,” Dr. Wilens said. He added that the Rational Recovery program, an alternative to Alcoholics Anonymous, also seems to work well. The approaches to ending substance use differ in that Alcoholics Anonymous’s orientation is spiritual and Rational Recovery’s is cognitive.

Dr. Wilens reported various disclosures, including consulting relationships with Ironshore Pharmaceuticals, KemPharm, and Neurovance/Otsuka.

SAN DIEGO – Substance use disorders rarely ride alone, a psychiatrist told colleagues, and it’s crucial to treat the accompanying mental illness that is almost always present.

“If you’re really depressed and you’re smoking marijuana, the smoking could have made it worse, but you were probably depressed before,” said Timothy E. Wilens, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston. Dr. Wilens spoke at the annual Psych Congress.

He pointed to numbers supporting the link between substance use and mental illness. He also offered several tips about treating substance use disorder (SUD).

In ADHD, consider the big picture. If a person has both ADHD and SUD, treat both if the level of substance abuse is lower. But focus on the SUD in more severe cases, he said, and realize that “most likely your treatment for ADHD isn’t going to work as well.”

The same goes for the anxiolytic buspirone (Buspar) in patients with depression and SUD.

Consider N-acetyl cysteine in cannabis use disorder. N-acetyl cysteine, a nutraceutical used as an asthma medication, has shown promise in trials as a treatment for cannabis use disorder, Dr. Wilens said. It helps patients avoid the temptation to smoke. “They won’t say they’ve lost all their cravings, but you’ll hear, ‘I just didn’t need to do it; I’m not smoking as much.’ If you hear that from your patients, you know it’s working. It’s a subtle effect, but it can help.”

Scamming’ drugs shouldn’t be your main worry. Substance use research suggests that users of pharmaceutical drugs for nonmedical uses rarely get them directly from practitioners (7%), but instead mainly get them through friends, Dr. Wilens said. “If you work with this population and treat ADHD or anxiety, you’re paranoid that everyone coming in wants to scam medicines. Be more concerned about oversupplying them with immediate-release medications and not [taking] them to task about keeping the medication safely stored.”

Interventions such as Alcoholics Anonymous are as “effective as any other treatment for substance abuse, and it’s not costly,” Dr. Wilens said. He added that the Rational Recovery program, an alternative to Alcoholics Anonymous, also seems to work well. The approaches to ending substance use differ in that Alcoholics Anonymous’s orientation is spiritual and Rational Recovery’s is cognitive.

Dr. Wilens reported various disclosures, including consulting relationships with Ironshore Pharmaceuticals, KemPharm, and Neurovance/Otsuka.

SAN DIEGO – Substance use disorders rarely ride alone, a psychiatrist told colleagues, and it’s crucial to treat the accompanying mental illness that is almost always present.

“If you’re really depressed and you’re smoking marijuana, the smoking could have made it worse, but you were probably depressed before,” said Timothy E. Wilens, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston. Dr. Wilens spoke at the annual Psych Congress.

He pointed to numbers supporting the link between substance use and mental illness. He also offered several tips about treating substance use disorder (SUD).

In ADHD, consider the big picture. If a person has both ADHD and SUD, treat both if the level of substance abuse is lower. But focus on the SUD in more severe cases, he said, and realize that “most likely your treatment for ADHD isn’t going to work as well.”

The same goes for the anxiolytic buspirone (Buspar) in patients with depression and SUD.

Consider N-acetyl cysteine in cannabis use disorder. N-acetyl cysteine, a nutraceutical used as an asthma medication, has shown promise in trials as a treatment for cannabis use disorder, Dr. Wilens said. It helps patients avoid the temptation to smoke. “They won’t say they’ve lost all their cravings, but you’ll hear, ‘I just didn’t need to do it; I’m not smoking as much.’ If you hear that from your patients, you know it’s working. It’s a subtle effect, but it can help.”

Scamming’ drugs shouldn’t be your main worry. Substance use research suggests that users of pharmaceutical drugs for nonmedical uses rarely get them directly from practitioners (7%), but instead mainly get them through friends, Dr. Wilens said. “If you work with this population and treat ADHD or anxiety, you’re paranoid that everyone coming in wants to scam medicines. Be more concerned about oversupplying them with immediate-release medications and not [taking] them to task about keeping the medication safely stored.”

Interventions such as Alcoholics Anonymous are as “effective as any other treatment for substance abuse, and it’s not costly,” Dr. Wilens said. He added that the Rational Recovery program, an alternative to Alcoholics Anonymous, also seems to work well. The approaches to ending substance use differ in that Alcoholics Anonymous’s orientation is spiritual and Rational Recovery’s is cognitive.

Dr. Wilens reported various disclosures, including consulting relationships with Ironshore Pharmaceuticals, KemPharm, and Neurovance/Otsuka.

REPORTING FROM PSYCH CONGRESS 2019

How to use lofexidine for quick opioid withdrawal

SAN DIEGO – Lofexidine (Lucemyra), the new kid on the block in the United States for opioid withdrawal, can help patients get through the process in a few days, instead of a week or more, according to Thomas Kosten, MD, a psychiatry professor and director of the division of addictions at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Lofexidine relieves symptom withdrawal and has significant advantages over clonidine, a similar drug, including easier dosing and no orthostatic hypertension.

In a video interview at the annual Psych Congress, Dr. Kosten went into the nuts and bolts of how to use lofexidine with buprenorphine and naltrexone – plus benzodiazepines when needed – to help people safely go through withdrawal and in just a few days.

Once chronic pain patients are off opioids, the next question is what to do for their pain. In a presentation before the interview, Dr. Kosten said he favors tricyclic antidepressants, especially desipramine because it has the fewest side effects. The effect size with tricyclic antidepressants is larger than with gabapentin and other options. They take a few weeks to kick in, however, so he’s thinking about a unique approach: using ketamine – either infusions or the new nasal spray esketamine (Spravato) – to tide people over in the meantime. It’s becoming well known that ketamine works amazingly fast for depression and suicidality, and there is emerging support that it might do the same for chronic pain. Dr. Kosten is a consultant for US Worldmeds, maker of lofexidine.

SAN DIEGO – Lofexidine (Lucemyra), the new kid on the block in the United States for opioid withdrawal, can help patients get through the process in a few days, instead of a week or more, according to Thomas Kosten, MD, a psychiatry professor and director of the division of addictions at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Lofexidine relieves symptom withdrawal and has significant advantages over clonidine, a similar drug, including easier dosing and no orthostatic hypertension.

In a video interview at the annual Psych Congress, Dr. Kosten went into the nuts and bolts of how to use lofexidine with buprenorphine and naltrexone – plus benzodiazepines when needed – to help people safely go through withdrawal and in just a few days.

Once chronic pain patients are off opioids, the next question is what to do for their pain. In a presentation before the interview, Dr. Kosten said he favors tricyclic antidepressants, especially desipramine because it has the fewest side effects. The effect size with tricyclic antidepressants is larger than with gabapentin and other options. They take a few weeks to kick in, however, so he’s thinking about a unique approach: using ketamine – either infusions or the new nasal spray esketamine (Spravato) – to tide people over in the meantime. It’s becoming well known that ketamine works amazingly fast for depression and suicidality, and there is emerging support that it might do the same for chronic pain. Dr. Kosten is a consultant for US Worldmeds, maker of lofexidine.

SAN DIEGO – Lofexidine (Lucemyra), the new kid on the block in the United States for opioid withdrawal, can help patients get through the process in a few days, instead of a week or more, according to Thomas Kosten, MD, a psychiatry professor and director of the division of addictions at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Lofexidine relieves symptom withdrawal and has significant advantages over clonidine, a similar drug, including easier dosing and no orthostatic hypertension.

In a video interview at the annual Psych Congress, Dr. Kosten went into the nuts and bolts of how to use lofexidine with buprenorphine and naltrexone – plus benzodiazepines when needed – to help people safely go through withdrawal and in just a few days.

Once chronic pain patients are off opioids, the next question is what to do for their pain. In a presentation before the interview, Dr. Kosten said he favors tricyclic antidepressants, especially desipramine because it has the fewest side effects. The effect size with tricyclic antidepressants is larger than with gabapentin and other options. They take a few weeks to kick in, however, so he’s thinking about a unique approach: using ketamine – either infusions or the new nasal spray esketamine (Spravato) – to tide people over in the meantime. It’s becoming well known that ketamine works amazingly fast for depression and suicidality, and there is emerging support that it might do the same for chronic pain. Dr. Kosten is a consultant for US Worldmeds, maker of lofexidine.

REPORTING FROM PSYCH CONGRESS 2019

Buprenorphine merits more attention for treatment of opioid use disorder

SAN DIEGO – Prescribing buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder requires strict discernment on the part of clinicians, Arwen Podesta, MD, said at the annual Psych Congress.

She encouraged clinicians to be prepared for a visit from the Drug Enforcement Administration, understand the unique properties of buprenorphine, and make sure that patients grasp the importance of sublingual administration.

Research shows that only 5% of physicians are allowed to prescribe buprenorphine – an opioid – by way of a DEA waiver, Dr. Podesta said. About half do not prescribe the drug. Barriers to prescribing buprenorphine include factors such as low reimbursement and untrained support staff, said Dr. Podesta, a board-certified psychiatrist who subspecializes in addiction medicine and practices in New Orleans.

But she noted that the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has recommended that medication-assisted therapy (MAT) – methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone – be considered in all patients with opioid use disorder. The drugs are safe and effective when used correctly, the federal agency has said.

Remember, Dr. Podesta said, that “patients taking MAT are considered to be in recovery.” In the big picture, she added, “we have to improve access to care because we have so many people who don’t have access to treatment.”

Getting permission from the DEA to prescribe buprenorphine – a schedule III controlled substance – comes with a price, Dr. Podesta said. “We have special scrutiny from the DEA,” she said. They come in and want to see your records. It sounds very punitive, although it’s their jobs.”

The best approach is to document that you know what you’re doing, she said. “It’s your job to educate them about why you’re using buprenorphine and produce the records to show that.”

Being aware of buprenorphine’s unique properties is important, she said. The drug is safer on the overdose front than are other opioids, Dr. Podesta said, but it can be very dangerous in patients without opioid tolerance. According to the DEA, as an analgesic, buprenorphine is 20-30 times more potent than morphine. Also, like morphine, patients who take buprenorphine are likely to experience euphoria, papillary restriction, and respiratory depression and sedation.

The buprenorphine/naloxone formulation is preferred to treat opioid use disorder, she noted.

The reason that naloxone, which treats opioid overdoses, is part of the drug combo is because as an add-on, it reduces the risk that buprenorphine will be crushed and snorted for an opioid high, she said. Those who take the combo drug via that method could end up with sudden and nasty withdrawal symptoms.

When the drug combo is administered sublingually, the idea is that the “good stuff” (buprenorphine) is absorbed in the mouth, while the “bad stuff” (naloxone) is harmlessly absorbed in the gut, Dr. Podesta said. This happens because the drugs are absorbed differently.

But patients can mistakenly trigger symptoms of withdrawal if, for example, they put the combo drug on their tongue and then go to sleep. “That’s a peril,” she said, and it’s important to make sure patients know what to do – and what not to do.

Dr. Podesta emphasized the importance of choosing language related to patients with addictions carefully and respectfully.

“We have stigma,” she said. “We have been saying that patients are ‘dirty’ or ‘clean,’ and if they’re ‘clean,’ they’re the opposite of ‘dirty.’

She also suggested that clinicians drop the use of the word “contract” to describe treatment agreements between patients and clinicians. “Call it an ‘agreement,’ ” she said. “It seems more mutual and less punitive or risky for the patient to sign, especially when they’re in a precarious comfort zone.”

And consider that even the words “substance abuse” can be misleading, she said. “Many [patients] are taking the medications that the doctor prescribed and following instructions to the letter.”

Dr. Podesta disclosed consulting with Kaleo, Pear Therapeutics, and JayMac, and serving on the speakers bureau of Alkermes, Orexo, and US WorldMeds. She is the author of “Hooked: A Concise Guide to the Underlying Mechanics of Addiction and Treatment for Patients, Families, and Providers” (Dog Ear Publishing, 2016).

SAN DIEGO – Prescribing buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder requires strict discernment on the part of clinicians, Arwen Podesta, MD, said at the annual Psych Congress.

She encouraged clinicians to be prepared for a visit from the Drug Enforcement Administration, understand the unique properties of buprenorphine, and make sure that patients grasp the importance of sublingual administration.

Research shows that only 5% of physicians are allowed to prescribe buprenorphine – an opioid – by way of a DEA waiver, Dr. Podesta said. About half do not prescribe the drug. Barriers to prescribing buprenorphine include factors such as low reimbursement and untrained support staff, said Dr. Podesta, a board-certified psychiatrist who subspecializes in addiction medicine and practices in New Orleans.

But she noted that the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has recommended that medication-assisted therapy (MAT) – methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone – be considered in all patients with opioid use disorder. The drugs are safe and effective when used correctly, the federal agency has said.

Remember, Dr. Podesta said, that “patients taking MAT are considered to be in recovery.” In the big picture, she added, “we have to improve access to care because we have so many people who don’t have access to treatment.”

Getting permission from the DEA to prescribe buprenorphine – a schedule III controlled substance – comes with a price, Dr. Podesta said. “We have special scrutiny from the DEA,” she said. They come in and want to see your records. It sounds very punitive, although it’s their jobs.”

The best approach is to document that you know what you’re doing, she said. “It’s your job to educate them about why you’re using buprenorphine and produce the records to show that.”

Being aware of buprenorphine’s unique properties is important, she said. The drug is safer on the overdose front than are other opioids, Dr. Podesta said, but it can be very dangerous in patients without opioid tolerance. According to the DEA, as an analgesic, buprenorphine is 20-30 times more potent than morphine. Also, like morphine, patients who take buprenorphine are likely to experience euphoria, papillary restriction, and respiratory depression and sedation.

The buprenorphine/naloxone formulation is preferred to treat opioid use disorder, she noted.

The reason that naloxone, which treats opioid overdoses, is part of the drug combo is because as an add-on, it reduces the risk that buprenorphine will be crushed and snorted for an opioid high, she said. Those who take the combo drug via that method could end up with sudden and nasty withdrawal symptoms.

When the drug combo is administered sublingually, the idea is that the “good stuff” (buprenorphine) is absorbed in the mouth, while the “bad stuff” (naloxone) is harmlessly absorbed in the gut, Dr. Podesta said. This happens because the drugs are absorbed differently.

But patients can mistakenly trigger symptoms of withdrawal if, for example, they put the combo drug on their tongue and then go to sleep. “That’s a peril,” she said, and it’s important to make sure patients know what to do – and what not to do.

Dr. Podesta emphasized the importance of choosing language related to patients with addictions carefully and respectfully.

“We have stigma,” she said. “We have been saying that patients are ‘dirty’ or ‘clean,’ and if they’re ‘clean,’ they’re the opposite of ‘dirty.’

She also suggested that clinicians drop the use of the word “contract” to describe treatment agreements between patients and clinicians. “Call it an ‘agreement,’ ” she said. “It seems more mutual and less punitive or risky for the patient to sign, especially when they’re in a precarious comfort zone.”

And consider that even the words “substance abuse” can be misleading, she said. “Many [patients] are taking the medications that the doctor prescribed and following instructions to the letter.”

Dr. Podesta disclosed consulting with Kaleo, Pear Therapeutics, and JayMac, and serving on the speakers bureau of Alkermes, Orexo, and US WorldMeds. She is the author of “Hooked: A Concise Guide to the Underlying Mechanics of Addiction and Treatment for Patients, Families, and Providers” (Dog Ear Publishing, 2016).

SAN DIEGO – Prescribing buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder requires strict discernment on the part of clinicians, Arwen Podesta, MD, said at the annual Psych Congress.

She encouraged clinicians to be prepared for a visit from the Drug Enforcement Administration, understand the unique properties of buprenorphine, and make sure that patients grasp the importance of sublingual administration.

Research shows that only 5% of physicians are allowed to prescribe buprenorphine – an opioid – by way of a DEA waiver, Dr. Podesta said. About half do not prescribe the drug. Barriers to prescribing buprenorphine include factors such as low reimbursement and untrained support staff, said Dr. Podesta, a board-certified psychiatrist who subspecializes in addiction medicine and practices in New Orleans.

But she noted that the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has recommended that medication-assisted therapy (MAT) – methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone – be considered in all patients with opioid use disorder. The drugs are safe and effective when used correctly, the federal agency has said.

Remember, Dr. Podesta said, that “patients taking MAT are considered to be in recovery.” In the big picture, she added, “we have to improve access to care because we have so many people who don’t have access to treatment.”

Getting permission from the DEA to prescribe buprenorphine – a schedule III controlled substance – comes with a price, Dr. Podesta said. “We have special scrutiny from the DEA,” she said. They come in and want to see your records. It sounds very punitive, although it’s their jobs.”

The best approach is to document that you know what you’re doing, she said. “It’s your job to educate them about why you’re using buprenorphine and produce the records to show that.”

Being aware of buprenorphine’s unique properties is important, she said. The drug is safer on the overdose front than are other opioids, Dr. Podesta said, but it can be very dangerous in patients without opioid tolerance. According to the DEA, as an analgesic, buprenorphine is 20-30 times more potent than morphine. Also, like morphine, patients who take buprenorphine are likely to experience euphoria, papillary restriction, and respiratory depression and sedation.

The buprenorphine/naloxone formulation is preferred to treat opioid use disorder, she noted.

The reason that naloxone, which treats opioid overdoses, is part of the drug combo is because as an add-on, it reduces the risk that buprenorphine will be crushed and snorted for an opioid high, she said. Those who take the combo drug via that method could end up with sudden and nasty withdrawal symptoms.

When the drug combo is administered sublingually, the idea is that the “good stuff” (buprenorphine) is absorbed in the mouth, while the “bad stuff” (naloxone) is harmlessly absorbed in the gut, Dr. Podesta said. This happens because the drugs are absorbed differently.

But patients can mistakenly trigger symptoms of withdrawal if, for example, they put the combo drug on their tongue and then go to sleep. “That’s a peril,” she said, and it’s important to make sure patients know what to do – and what not to do.

Dr. Podesta emphasized the importance of choosing language related to patients with addictions carefully and respectfully.

“We have stigma,” she said. “We have been saying that patients are ‘dirty’ or ‘clean,’ and if they’re ‘clean,’ they’re the opposite of ‘dirty.’

She also suggested that clinicians drop the use of the word “contract” to describe treatment agreements between patients and clinicians. “Call it an ‘agreement,’ ” she said. “It seems more mutual and less punitive or risky for the patient to sign, especially when they’re in a precarious comfort zone.”

And consider that even the words “substance abuse” can be misleading, she said. “Many [patients] are taking the medications that the doctor prescribed and following instructions to the letter.”

Dr. Podesta disclosed consulting with Kaleo, Pear Therapeutics, and JayMac, and serving on the speakers bureau of Alkermes, Orexo, and US WorldMeds. She is the author of “Hooked: A Concise Guide to the Underlying Mechanics of Addiction and Treatment for Patients, Families, and Providers” (Dog Ear Publishing, 2016).

REPORTING FROM PSYCH CONGRESS 2019

Clinical Pharmacists Improve Patient Outcomes and Expand Access to Care

The US is in the midst of a chronic disease crisis. According to the latest published data available, 60% of Americans have at least 1 chronic condition, and 42% have ≥ 2 chronic conditions.1 Estimates by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) indicate a current shortfall of 13 800 primary care physicians and a projected escalation of that shortage to be between 14 800 and 49 300 physicians by the year 2030.2

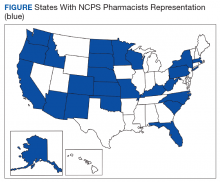

The US Public Health Service (USPHS) has used pharmacists since 1930 to provide direct patient care to underserved and vulnerable populations. Clinical pharmacists currently serve in direct patient care roles within the Indian Health Service (IHS), Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the United States Coast Guard (USCG) in many states (Figure). These pharmacists play a vital role in improving access to care and delivering quality care by managing acute and chronic diseases in collaborative practice settings and pharmacist-managed clinics.

It has previously been reported that in the face of physician shortages and growing demand for primary health care providers, pharmacists are well-equipped and motivated to meet this demand.3 A review of the previous 2 years of outcomes reported by clinical pharmacists certified through the USPHS National Clinical Pharmacy Specialist (NCPS) Committee are presented to demonstrate the impact of pharmacists in advancing the health of the populations they serve and to showcase a model for ameliorating the ongoing physician shortage.

Background

The USPHS NCPS Committee serves to promote uniform competency among clinical pharmacists by establishing national standards for protocols, collaborative practice agreements (CPAs), credentialing and privileging of pharmacists, and by collecting, reviewing, and publishing health care outcomes. The committee, whose constituents include pharmacist and physician subject matter experts from across USPHS agencies, reviews applications and protocols and certifies pharmacists (civilian and uniformed) to recognize an advanced scope of practice in managing various diseases and optimizing medication therapy. NCPScertified pharmacists manage a wide spectrum of diseases, including coagulopathy, asthma, diabetes mellitus (DM), hepatitis C, HIV, hypertension, pain, seizure disorders, and tobacco use disorders.

Clinical pharmacists practicing chronic disease management establish a clinical service in collaboration with 1 or more physicians, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners. In this collaborative practice, the health care practitioner(s) refer patients to be managed by a pharmacist for specific medical needs, such as anticoagulation management, or for holistic medication- focused care (eg, cardiovascular risk reduction, DM management, HIV, hepatitis, or mental health). The pharmacist may order and interpret laboratory tests, check vital signs, perform a limited physical examination, and gather other pertinent information from the patient and the medical record in order to provide the best possible care to the patient.

Medications may be started, stopped, or adjusted, education is provided, and therapeutic lifestyle interventions may be recommended. The pharmacist-run clinic provides the patient more frequent interaction with a health care professional (pharmacist) and focused disease management. As a result, pharmacists increase access to care and allow the medical team to handle a larger panel of patients as the practitioner delegates specified diseases to the pharmacist- managed clinic(s). The number of NCPS-certified pharmacists grew 46% from 2012 (n = 230) to 2017 (n = 336), reflecting an evolution of pharmacists’ practice to better meet the need of patients across the nation.

Methods

The NCPS Committee requires NCPS pharmacists to report data annually from all patients referred for pharmacist management for specific diseases in which they have been certified. The data reflect the patient’s clinical outcome goal status at the time of referral as well as the same status at the end of the reporting period or on release from the pharmacist-run clinic. These data describe the impact prescribing pharmacists have on patients reaching clinical outcome goals acting as the team member specializing in the medication selection and dosing aspect of care.

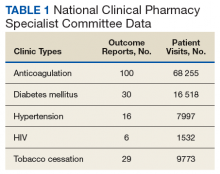

These records were reviewed for the fiscal year (FY) periods of October 1, 2015 to September 30, 2016 (FY 2016) and October 1, 2016 to September 30, 2017 (FY 2017). A systematic review of submitted reports resulted in 181 reports that included all requested data points for the disease as published here for FYs 2016 and 2017. These include 66 reports from FY 2016 and 115 reports from FY 2017; they cover 76 BOP and IHS facilities located across 24 states. Table 1 shows the number of outcome reports collected from 104 075 patient visits in pharmacist-run clinics in FYs 2016 and 2017.

Results

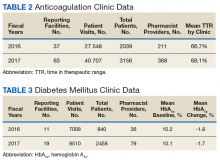

The following tables represent the standardized outcomes collected by NCPS-certified pharmacists providing direct patient care. Patients on anticoagulants (eg, warfarin) require special monitoring and education for drug interactions and adverse effects. NCPS-certified pharmacists were able to achieve a mean patient time in therapeutic range (TTR) of 67.6% (regardless of indication) over the 2 years (calculated per each facility by Rosendaal method of linear interpolation then combined in a weighted average per visit). The TTR produced by NCPS-certified pharmacists are consistent with Chest Guidelines and Expert Panel Report suggesting that TTR should be between 65% and 70%.4 Table 2 shows data from 100 reports with 68 255 patient visits for anticoagulation management.

DM management can be complex and time-intensive. NCPS data indicate pharmacist intervention resulted in a mean decrease in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 1.8% from a baseline of 10.2% (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 3 shows data from 30 reports with 16 518 patient visits for DM care.

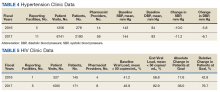

In addition to diet and exercise, medication management plays a vital role in managing hypertension. Patients managed by an NCPS-certified pharmacist experienced a mean decrease in blood pressure from 144/83 to 133/77, putting them in goal for both systolic and diastolic ranges (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 4 shows data from 16 reports and 7997 patient visits for treatment of hypertension.

HIV viral suppression is vital in order to best manage patients with HIV and reduce the risk of transmission. Pharmacistled clinics have shown a 32.9% absolute improvement in patients at goal (viral load < 50 copies/mL), from a mean baseline of 46.0% to a mean final assessment of 71.6% of patients at goal (combined by weighted average visits). Table 5 shows data from 6 reports covering 1532 patient encounters for management of HIV.

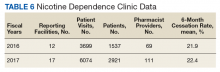

Nicotine dependence includes the use of cigarettes, cigars, pipe tobacco, chewing tobacco, and vaping products containing nicotine. NCPS-certified pharmacists have successfully helped patients improve their chance of quitting, with a 6-month quit rate of 22.2% (quit rate calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average by visits), which is higher than the national average of 9.4% as reported by the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention. 5 Table 6 shows 29 reports covering 9773 patient visits for treatment of nicotine dependence.

Discussion

These data demonstrate the ability of advanced practice pharmacists in multiple locations within the federal sector to improve targeted clinical outcomes in patients with varying diseases. These results are strengthened by their varied origins as well as the improvements observed across the board. Limitations include the general lack of a comparable dataset, manual method of selfreporting by the individual facilities, and the relatively limited array of diseases reported. Although NCPS-certified pharmacists are currently providing care for patients with hepatitis C, asthma, seizure, pain and other diseases not reported here, there are insufficient data collected for FYs 2016 and 2017 to merit inclusion within this report.

Pharmacists are trusted, readily available medication experts. In a clinical role, NCPS-certified pharmacists have increased access to primary care services and demonstrated beneficial impact on important health outcomes as exhibited by the data reported above. Clinical pharmacy is a growing field, and NCPS has displayed continual growth in both the number of NCPS-certified pharmacists and the number of patient encounters performed by these providers. As more pharmacists in all settings collaborate with medical providers to offer high-quality clinical care, these providers will have more opportunity to delegate disease management. Continued reporting of clinical pharmacy outcomes is expected to increase confidence in pharmacists as primary care providers, increase utilization of pharmacy clinical services, and assist in easing the burden of primary care provider shortages across our nation.

Although these outcomes indicate demonstrable benefit in patient-centered outcomes, the need for ongoing assessment and continued improvement is not obviated. Future efforts may benefit from a comparison of alternative approaches to better facilitate the establishment of best practices. Alignment of clinical outcomes with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Electronic Clinical Quality Measures, where applicable, also may prove beneficial by automating the reporting process and thereby decreasing the burden of reporting as well as providing an avenue for standard comparison across multiple populations. Clinical pharmacy interventions have positive outcomes based on the NCPS model, and the NCPS Committee invites other clinical settings to report outcomes data with which to compare.

Conclusion

The NCPS Committee has documented positive outcomes of clinical pharmacy intervention and anticipates growth of the pharmacy profession as additional states and health systems recognize the capacity of the pharmacist to provide high-quality, multidisciplinary patient care. Clinical pharmacists are prepared to address critical health care needs as the US continues to face a PCP shortage.2 The NCPS Committee challenges those participating in clinical pharmacy practice to report outcomes to amplify this body of evidence.

Acknowledgments

NCPS-certified pharmacists provided the outcomes detailed in this report. For document review and edits: Federal Bureau of Prison Publication Review Workgroup; RADM Ty Bingham, USPHS; CAPT Cindy Gunderson, USPHS; CAPT Kevin Brooks, USPHS.

1. Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corp; 2017.

2. Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, Reynolds R, Iacobucci W. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2016 to 2030, 2018 update. Association of American Medical Colleges. March 2018.

3. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. A report to the U.S. Surgeon General 2011. https://www .accp.com/docs/positions/misc/improving_patient_and _health_system_outcomes.pdf. Updated December 2011. Accessed September 11, 2019.

4. Lip G, Banerjee A, Boriani G, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation. CHEST guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2018;154(5):1121-1201.

5. Babb S, Marlarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2000-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457-1464.

The US is in the midst of a chronic disease crisis. According to the latest published data available, 60% of Americans have at least 1 chronic condition, and 42% have ≥ 2 chronic conditions.1 Estimates by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) indicate a current shortfall of 13 800 primary care physicians and a projected escalation of that shortage to be between 14 800 and 49 300 physicians by the year 2030.2

The US Public Health Service (USPHS) has used pharmacists since 1930 to provide direct patient care to underserved and vulnerable populations. Clinical pharmacists currently serve in direct patient care roles within the Indian Health Service (IHS), Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the United States Coast Guard (USCG) in many states (Figure). These pharmacists play a vital role in improving access to care and delivering quality care by managing acute and chronic diseases in collaborative practice settings and pharmacist-managed clinics.

It has previously been reported that in the face of physician shortages and growing demand for primary health care providers, pharmacists are well-equipped and motivated to meet this demand.3 A review of the previous 2 years of outcomes reported by clinical pharmacists certified through the USPHS National Clinical Pharmacy Specialist (NCPS) Committee are presented to demonstrate the impact of pharmacists in advancing the health of the populations they serve and to showcase a model for ameliorating the ongoing physician shortage.

Background

The USPHS NCPS Committee serves to promote uniform competency among clinical pharmacists by establishing national standards for protocols, collaborative practice agreements (CPAs), credentialing and privileging of pharmacists, and by collecting, reviewing, and publishing health care outcomes. The committee, whose constituents include pharmacist and physician subject matter experts from across USPHS agencies, reviews applications and protocols and certifies pharmacists (civilian and uniformed) to recognize an advanced scope of practice in managing various diseases and optimizing medication therapy. NCPScertified pharmacists manage a wide spectrum of diseases, including coagulopathy, asthma, diabetes mellitus (DM), hepatitis C, HIV, hypertension, pain, seizure disorders, and tobacco use disorders.

Clinical pharmacists practicing chronic disease management establish a clinical service in collaboration with 1 or more physicians, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners. In this collaborative practice, the health care practitioner(s) refer patients to be managed by a pharmacist for specific medical needs, such as anticoagulation management, or for holistic medication- focused care (eg, cardiovascular risk reduction, DM management, HIV, hepatitis, or mental health). The pharmacist may order and interpret laboratory tests, check vital signs, perform a limited physical examination, and gather other pertinent information from the patient and the medical record in order to provide the best possible care to the patient.

Medications may be started, stopped, or adjusted, education is provided, and therapeutic lifestyle interventions may be recommended. The pharmacist-run clinic provides the patient more frequent interaction with a health care professional (pharmacist) and focused disease management. As a result, pharmacists increase access to care and allow the medical team to handle a larger panel of patients as the practitioner delegates specified diseases to the pharmacist- managed clinic(s). The number of NCPS-certified pharmacists grew 46% from 2012 (n = 230) to 2017 (n = 336), reflecting an evolution of pharmacists’ practice to better meet the need of patients across the nation.

Methods

The NCPS Committee requires NCPS pharmacists to report data annually from all patients referred for pharmacist management for specific diseases in which they have been certified. The data reflect the patient’s clinical outcome goal status at the time of referral as well as the same status at the end of the reporting period or on release from the pharmacist-run clinic. These data describe the impact prescribing pharmacists have on patients reaching clinical outcome goals acting as the team member specializing in the medication selection and dosing aspect of care.

These records were reviewed for the fiscal year (FY) periods of October 1, 2015 to September 30, 2016 (FY 2016) and October 1, 2016 to September 30, 2017 (FY 2017). A systematic review of submitted reports resulted in 181 reports that included all requested data points for the disease as published here for FYs 2016 and 2017. These include 66 reports from FY 2016 and 115 reports from FY 2017; they cover 76 BOP and IHS facilities located across 24 states. Table 1 shows the number of outcome reports collected from 104 075 patient visits in pharmacist-run clinics in FYs 2016 and 2017.

Results

The following tables represent the standardized outcomes collected by NCPS-certified pharmacists providing direct patient care. Patients on anticoagulants (eg, warfarin) require special monitoring and education for drug interactions and adverse effects. NCPS-certified pharmacists were able to achieve a mean patient time in therapeutic range (TTR) of 67.6% (regardless of indication) over the 2 years (calculated per each facility by Rosendaal method of linear interpolation then combined in a weighted average per visit). The TTR produced by NCPS-certified pharmacists are consistent with Chest Guidelines and Expert Panel Report suggesting that TTR should be between 65% and 70%.4 Table 2 shows data from 100 reports with 68 255 patient visits for anticoagulation management.

DM management can be complex and time-intensive. NCPS data indicate pharmacist intervention resulted in a mean decrease in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 1.8% from a baseline of 10.2% (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 3 shows data from 30 reports with 16 518 patient visits for DM care.

In addition to diet and exercise, medication management plays a vital role in managing hypertension. Patients managed by an NCPS-certified pharmacist experienced a mean decrease in blood pressure from 144/83 to 133/77, putting them in goal for both systolic and diastolic ranges (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 4 shows data from 16 reports and 7997 patient visits for treatment of hypertension.

HIV viral suppression is vital in order to best manage patients with HIV and reduce the risk of transmission. Pharmacistled clinics have shown a 32.9% absolute improvement in patients at goal (viral load < 50 copies/mL), from a mean baseline of 46.0% to a mean final assessment of 71.6% of patients at goal (combined by weighted average visits). Table 5 shows data from 6 reports covering 1532 patient encounters for management of HIV.

Nicotine dependence includes the use of cigarettes, cigars, pipe tobacco, chewing tobacco, and vaping products containing nicotine. NCPS-certified pharmacists have successfully helped patients improve their chance of quitting, with a 6-month quit rate of 22.2% (quit rate calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average by visits), which is higher than the national average of 9.4% as reported by the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention. 5 Table 6 shows 29 reports covering 9773 patient visits for treatment of nicotine dependence.

Discussion

These data demonstrate the ability of advanced practice pharmacists in multiple locations within the federal sector to improve targeted clinical outcomes in patients with varying diseases. These results are strengthened by their varied origins as well as the improvements observed across the board. Limitations include the general lack of a comparable dataset, manual method of selfreporting by the individual facilities, and the relatively limited array of diseases reported. Although NCPS-certified pharmacists are currently providing care for patients with hepatitis C, asthma, seizure, pain and other diseases not reported here, there are insufficient data collected for FYs 2016 and 2017 to merit inclusion within this report.

Pharmacists are trusted, readily available medication experts. In a clinical role, NCPS-certified pharmacists have increased access to primary care services and demonstrated beneficial impact on important health outcomes as exhibited by the data reported above. Clinical pharmacy is a growing field, and NCPS has displayed continual growth in both the number of NCPS-certified pharmacists and the number of patient encounters performed by these providers. As more pharmacists in all settings collaborate with medical providers to offer high-quality clinical care, these providers will have more opportunity to delegate disease management. Continued reporting of clinical pharmacy outcomes is expected to increase confidence in pharmacists as primary care providers, increase utilization of pharmacy clinical services, and assist in easing the burden of primary care provider shortages across our nation.

Although these outcomes indicate demonstrable benefit in patient-centered outcomes, the need for ongoing assessment and continued improvement is not obviated. Future efforts may benefit from a comparison of alternative approaches to better facilitate the establishment of best practices. Alignment of clinical outcomes with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Electronic Clinical Quality Measures, where applicable, also may prove beneficial by automating the reporting process and thereby decreasing the burden of reporting as well as providing an avenue for standard comparison across multiple populations. Clinical pharmacy interventions have positive outcomes based on the NCPS model, and the NCPS Committee invites other clinical settings to report outcomes data with which to compare.

Conclusion

The NCPS Committee has documented positive outcomes of clinical pharmacy intervention and anticipates growth of the pharmacy profession as additional states and health systems recognize the capacity of the pharmacist to provide high-quality, multidisciplinary patient care. Clinical pharmacists are prepared to address critical health care needs as the US continues to face a PCP shortage.2 The NCPS Committee challenges those participating in clinical pharmacy practice to report outcomes to amplify this body of evidence.

Acknowledgments

NCPS-certified pharmacists provided the outcomes detailed in this report. For document review and edits: Federal Bureau of Prison Publication Review Workgroup; RADM Ty Bingham, USPHS; CAPT Cindy Gunderson, USPHS; CAPT Kevin Brooks, USPHS.

The US is in the midst of a chronic disease crisis. According to the latest published data available, 60% of Americans have at least 1 chronic condition, and 42% have ≥ 2 chronic conditions.1 Estimates by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) indicate a current shortfall of 13 800 primary care physicians and a projected escalation of that shortage to be between 14 800 and 49 300 physicians by the year 2030.2

The US Public Health Service (USPHS) has used pharmacists since 1930 to provide direct patient care to underserved and vulnerable populations. Clinical pharmacists currently serve in direct patient care roles within the Indian Health Service (IHS), Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the United States Coast Guard (USCG) in many states (Figure). These pharmacists play a vital role in improving access to care and delivering quality care by managing acute and chronic diseases in collaborative practice settings and pharmacist-managed clinics.

It has previously been reported that in the face of physician shortages and growing demand for primary health care providers, pharmacists are well-equipped and motivated to meet this demand.3 A review of the previous 2 years of outcomes reported by clinical pharmacists certified through the USPHS National Clinical Pharmacy Specialist (NCPS) Committee are presented to demonstrate the impact of pharmacists in advancing the health of the populations they serve and to showcase a model for ameliorating the ongoing physician shortage.

Background

The USPHS NCPS Committee serves to promote uniform competency among clinical pharmacists by establishing national standards for protocols, collaborative practice agreements (CPAs), credentialing and privileging of pharmacists, and by collecting, reviewing, and publishing health care outcomes. The committee, whose constituents include pharmacist and physician subject matter experts from across USPHS agencies, reviews applications and protocols and certifies pharmacists (civilian and uniformed) to recognize an advanced scope of practice in managing various diseases and optimizing medication therapy. NCPScertified pharmacists manage a wide spectrum of diseases, including coagulopathy, asthma, diabetes mellitus (DM), hepatitis C, HIV, hypertension, pain, seizure disorders, and tobacco use disorders.

Clinical pharmacists practicing chronic disease management establish a clinical service in collaboration with 1 or more physicians, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners. In this collaborative practice, the health care practitioner(s) refer patients to be managed by a pharmacist for specific medical needs, such as anticoagulation management, or for holistic medication- focused care (eg, cardiovascular risk reduction, DM management, HIV, hepatitis, or mental health). The pharmacist may order and interpret laboratory tests, check vital signs, perform a limited physical examination, and gather other pertinent information from the patient and the medical record in order to provide the best possible care to the patient.

Medications may be started, stopped, or adjusted, education is provided, and therapeutic lifestyle interventions may be recommended. The pharmacist-run clinic provides the patient more frequent interaction with a health care professional (pharmacist) and focused disease management. As a result, pharmacists increase access to care and allow the medical team to handle a larger panel of patients as the practitioner delegates specified diseases to the pharmacist- managed clinic(s). The number of NCPS-certified pharmacists grew 46% from 2012 (n = 230) to 2017 (n = 336), reflecting an evolution of pharmacists’ practice to better meet the need of patients across the nation.

Methods

The NCPS Committee requires NCPS pharmacists to report data annually from all patients referred for pharmacist management for specific diseases in which they have been certified. The data reflect the patient’s clinical outcome goal status at the time of referral as well as the same status at the end of the reporting period or on release from the pharmacist-run clinic. These data describe the impact prescribing pharmacists have on patients reaching clinical outcome goals acting as the team member specializing in the medication selection and dosing aspect of care.

These records were reviewed for the fiscal year (FY) periods of October 1, 2015 to September 30, 2016 (FY 2016) and October 1, 2016 to September 30, 2017 (FY 2017). A systematic review of submitted reports resulted in 181 reports that included all requested data points for the disease as published here for FYs 2016 and 2017. These include 66 reports from FY 2016 and 115 reports from FY 2017; they cover 76 BOP and IHS facilities located across 24 states. Table 1 shows the number of outcome reports collected from 104 075 patient visits in pharmacist-run clinics in FYs 2016 and 2017.

Results

The following tables represent the standardized outcomes collected by NCPS-certified pharmacists providing direct patient care. Patients on anticoagulants (eg, warfarin) require special monitoring and education for drug interactions and adverse effects. NCPS-certified pharmacists were able to achieve a mean patient time in therapeutic range (TTR) of 67.6% (regardless of indication) over the 2 years (calculated per each facility by Rosendaal method of linear interpolation then combined in a weighted average per visit). The TTR produced by NCPS-certified pharmacists are consistent with Chest Guidelines and Expert Panel Report suggesting that TTR should be between 65% and 70%.4 Table 2 shows data from 100 reports with 68 255 patient visits for anticoagulation management.

DM management can be complex and time-intensive. NCPS data indicate pharmacist intervention resulted in a mean decrease in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 1.8% from a baseline of 10.2% (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 3 shows data from 30 reports with 16 518 patient visits for DM care.

In addition to diet and exercise, medication management plays a vital role in managing hypertension. Patients managed by an NCPS-certified pharmacist experienced a mean decrease in blood pressure from 144/83 to 133/77, putting them in goal for both systolic and diastolic ranges (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 4 shows data from 16 reports and 7997 patient visits for treatment of hypertension.

HIV viral suppression is vital in order to best manage patients with HIV and reduce the risk of transmission. Pharmacistled clinics have shown a 32.9% absolute improvement in patients at goal (viral load < 50 copies/mL), from a mean baseline of 46.0% to a mean final assessment of 71.6% of patients at goal (combined by weighted average visits). Table 5 shows data from 6 reports covering 1532 patient encounters for management of HIV.

Nicotine dependence includes the use of cigarettes, cigars, pipe tobacco, chewing tobacco, and vaping products containing nicotine. NCPS-certified pharmacists have successfully helped patients improve their chance of quitting, with a 6-month quit rate of 22.2% (quit rate calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average by visits), which is higher than the national average of 9.4% as reported by the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention. 5 Table 6 shows 29 reports covering 9773 patient visits for treatment of nicotine dependence.

Discussion

These data demonstrate the ability of advanced practice pharmacists in multiple locations within the federal sector to improve targeted clinical outcomes in patients with varying diseases. These results are strengthened by their varied origins as well as the improvements observed across the board. Limitations include the general lack of a comparable dataset, manual method of selfreporting by the individual facilities, and the relatively limited array of diseases reported. Although NCPS-certified pharmacists are currently providing care for patients with hepatitis C, asthma, seizure, pain and other diseases not reported here, there are insufficient data collected for FYs 2016 and 2017 to merit inclusion within this report.

Pharmacists are trusted, readily available medication experts. In a clinical role, NCPS-certified pharmacists have increased access to primary care services and demonstrated beneficial impact on important health outcomes as exhibited by the data reported above. Clinical pharmacy is a growing field, and NCPS has displayed continual growth in both the number of NCPS-certified pharmacists and the number of patient encounters performed by these providers. As more pharmacists in all settings collaborate with medical providers to offer high-quality clinical care, these providers will have more opportunity to delegate disease management. Continued reporting of clinical pharmacy outcomes is expected to increase confidence in pharmacists as primary care providers, increase utilization of pharmacy clinical services, and assist in easing the burden of primary care provider shortages across our nation.

Although these outcomes indicate demonstrable benefit in patient-centered outcomes, the need for ongoing assessment and continued improvement is not obviated. Future efforts may benefit from a comparison of alternative approaches to better facilitate the establishment of best practices. Alignment of clinical outcomes with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Electronic Clinical Quality Measures, where applicable, also may prove beneficial by automating the reporting process and thereby decreasing the burden of reporting as well as providing an avenue for standard comparison across multiple populations. Clinical pharmacy interventions have positive outcomes based on the NCPS model, and the NCPS Committee invites other clinical settings to report outcomes data with which to compare.

Conclusion

The NCPS Committee has documented positive outcomes of clinical pharmacy intervention and anticipates growth of the pharmacy profession as additional states and health systems recognize the capacity of the pharmacist to provide high-quality, multidisciplinary patient care. Clinical pharmacists are prepared to address critical health care needs as the US continues to face a PCP shortage.2 The NCPS Committee challenges those participating in clinical pharmacy practice to report outcomes to amplify this body of evidence.

Acknowledgments

NCPS-certified pharmacists provided the outcomes detailed in this report. For document review and edits: Federal Bureau of Prison Publication Review Workgroup; RADM Ty Bingham, USPHS; CAPT Cindy Gunderson, USPHS; CAPT Kevin Brooks, USPHS.

1. Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corp; 2017.

2. Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, Reynolds R, Iacobucci W. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2016 to 2030, 2018 update. Association of American Medical Colleges. March 2018.

3. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. A report to the U.S. Surgeon General 2011. https://www .accp.com/docs/positions/misc/improving_patient_and _health_system_outcomes.pdf. Updated December 2011. Accessed September 11, 2019.

4. Lip G, Banerjee A, Boriani G, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation. CHEST guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2018;154(5):1121-1201.

5. Babb S, Marlarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2000-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457-1464.

1. Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corp; 2017.

2. Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, Reynolds R, Iacobucci W. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2016 to 2030, 2018 update. Association of American Medical Colleges. March 2018.

3. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. A report to the U.S. Surgeon General 2011. https://www .accp.com/docs/positions/misc/improving_patient_and _health_system_outcomes.pdf. Updated December 2011. Accessed September 11, 2019.

4. Lip G, Banerjee A, Boriani G, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation. CHEST guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2018;154(5):1121-1201.

5. Babb S, Marlarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2000-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457-1464.

Advancing Order Set Design

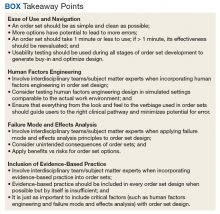

In the current health care environment, hospitals are constantly challenged to improve quality metrics and deliver better health care outcomes. One means to achieving quality improvement is through the use of order sets, groups of related orders that a health care provider (HCP) can place with either a few keystrokes or mouse clicks.1

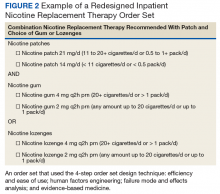

Historically, design of order sets has largely focused on clicking checkboxes containing evidence-based practices. According to Bates and colleagues and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, incorporating evidence-based medicine (EBM) into order sets is not by itself sufficient.2,3Execution of proper design coupled with simplicity and provider efficiency is paramount to HCP buy-in, increased likelihood of order set adherence, and to potentially better outcomes.

In this article, we outline advancements in order set design. These improvements increase provider efficiency and ease of use; incorporate human factors engineering (HFE); apply failure mode and effects analysis; and include EBM.

Methods