User login

CDC reports most vaping lung disease linked to THC-containing cartridges

and most products used were prepackaged, prefilled cartridges, according to new data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The majority of these products (66%) were THC-containing cartridges marketed under the brand name Dank. Dank cartridges are available at legal dispensaries and online in areas where they are legal. The Dank company posted a statement on its website warning buyers about fake cartridges and showing images of genuine cartridges. However, 89% of the cartridges were obtained on the street, from dealers, online, or from friends or social contacts, Jennifer Layden, MD, of the Illinois Department of Public Health said during a CDC telebriefing.

The illness was first recognized in Wisconsin and Illinois. Marijuana is illegal in Wisconsin; Illinois licensed recreational marijuana in 2009.

Other commonalties among cases have also emerged, Anne Schuchat, MD, deputy director of CDC, said during the call. More than two-thirds of the 805 confirmed or probable cases were male, and the median age was 23 years. The illness crosses age barriers, she said. About 62% were 18-24 years of age, and 54% under age 25. However, among the 12 deaths so far reported, the median age was 50 years. The age range was wide, from 27 to 71 years. Dr. Schuchat said data about medical comorbidities potentially linking the deaths is not yet available, although it is part of the ongoing investigation.

Other clinical commonalities included intensive use of THC-containing products and, in a small number of cases, concomitant use of benzodiazepenes, opioids, and narcotics.

Cases have now emerged in 46 states and in the U.S. Virgin Islands, although the number reported each week is dropping. However, this decrease may not represent a drop in newly occurring cases, but instead reflect delays in clinical recognition or reporting to local health departments, Dr. Schuchat said.

Regardless of the recent decline in reported cases, she said, the epidemic is serious, far reaching, and ongoing.

“I want to stress that this is a serious, life-threatening disease occurring mostly in otherwise healthy young people. These illnesses and deaths are occurring in the context of a dynamic marketplace with mix of products with mixes of ingredients, including potentially illicit substances. Users don’t know what’s in them and cannot tell from the ingredients listed on the packaging.”

Dr. Schuchat drew her data from two reports issued in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: a national case update by Peter A. Briss, MD, chair of CDC’s Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group, and colleagues, and a regional report coauthored by Dr. Layden of cases in Illinois and Wisconsin.

In the national report, 514 patients self-reported their history of e-cigarette and vaping use. Among those, 395 (76.9%) reported using THC-containing products, and 292 (56.8%) reported using nicotine-containing products in the 30 days preceding symptom onset. Almost half (210; 40.9%) reported using both THC- and nicotine-containing products.

But there appeared to be no clear pattern of use, said Dr. Briss, who also participated in the briefing. More than a third (185; 36.0%) reported exclusive use of THC-containing products, and 82 (16.0%) reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products.

The regional report added additional details.

Among the 86 patients who self-reported details, there were 234 unique cases of e-cigarette or THC vaping in 87 brands.

“Patients reported using numerous products and brands,” Dr. Layden noted. “Those who reported using THC products used an average of 2.1 different products and those who reported using nicotine products used about 1.3 different ones. Some patients reported using up to seven different brands, and these were used at least daily and sometimes numerous times in the day.”

According to the MMWR regional report, among the urinary THC screens obtained for 32 patients, “29 (91%) were positive for THC. One of these patients reported smoking combustible marijuana. Urinary THC levels for four patients who reported using THC-containing products exceeded 400 ng/ml, indicating intensive use of THC or THC-containing products.”

About 40% of THC users and 65% of nicotine-product users reported using the product at least five times a day; 52% said they used combustible marijuana in addition to the vapes, and 24% reported also smoking combustible tobacco.

There was a very low level of concomitant drug use. Two patients reported using LSD; one reported misusing dextroamphetamine-amphetamine (Adderall), and one reported misusing oxycodone. Two tested positive for benzodiazepines and opioids, and one each for only benzodiazepines, only opioids, only amphetamines. One patient screened positive for unidentified narcotics.

and most products used were prepackaged, prefilled cartridges, according to new data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The majority of these products (66%) were THC-containing cartridges marketed under the brand name Dank. Dank cartridges are available at legal dispensaries and online in areas where they are legal. The Dank company posted a statement on its website warning buyers about fake cartridges and showing images of genuine cartridges. However, 89% of the cartridges were obtained on the street, from dealers, online, or from friends or social contacts, Jennifer Layden, MD, of the Illinois Department of Public Health said during a CDC telebriefing.

The illness was first recognized in Wisconsin and Illinois. Marijuana is illegal in Wisconsin; Illinois licensed recreational marijuana in 2009.

Other commonalties among cases have also emerged, Anne Schuchat, MD, deputy director of CDC, said during the call. More than two-thirds of the 805 confirmed or probable cases were male, and the median age was 23 years. The illness crosses age barriers, she said. About 62% were 18-24 years of age, and 54% under age 25. However, among the 12 deaths so far reported, the median age was 50 years. The age range was wide, from 27 to 71 years. Dr. Schuchat said data about medical comorbidities potentially linking the deaths is not yet available, although it is part of the ongoing investigation.

Other clinical commonalities included intensive use of THC-containing products and, in a small number of cases, concomitant use of benzodiazepenes, opioids, and narcotics.

Cases have now emerged in 46 states and in the U.S. Virgin Islands, although the number reported each week is dropping. However, this decrease may not represent a drop in newly occurring cases, but instead reflect delays in clinical recognition or reporting to local health departments, Dr. Schuchat said.

Regardless of the recent decline in reported cases, she said, the epidemic is serious, far reaching, and ongoing.

“I want to stress that this is a serious, life-threatening disease occurring mostly in otherwise healthy young people. These illnesses and deaths are occurring in the context of a dynamic marketplace with mix of products with mixes of ingredients, including potentially illicit substances. Users don’t know what’s in them and cannot tell from the ingredients listed on the packaging.”

Dr. Schuchat drew her data from two reports issued in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: a national case update by Peter A. Briss, MD, chair of CDC’s Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group, and colleagues, and a regional report coauthored by Dr. Layden of cases in Illinois and Wisconsin.

In the national report, 514 patients self-reported their history of e-cigarette and vaping use. Among those, 395 (76.9%) reported using THC-containing products, and 292 (56.8%) reported using nicotine-containing products in the 30 days preceding symptom onset. Almost half (210; 40.9%) reported using both THC- and nicotine-containing products.

But there appeared to be no clear pattern of use, said Dr. Briss, who also participated in the briefing. More than a third (185; 36.0%) reported exclusive use of THC-containing products, and 82 (16.0%) reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products.

The regional report added additional details.

Among the 86 patients who self-reported details, there were 234 unique cases of e-cigarette or THC vaping in 87 brands.

“Patients reported using numerous products and brands,” Dr. Layden noted. “Those who reported using THC products used an average of 2.1 different products and those who reported using nicotine products used about 1.3 different ones. Some patients reported using up to seven different brands, and these were used at least daily and sometimes numerous times in the day.”

According to the MMWR regional report, among the urinary THC screens obtained for 32 patients, “29 (91%) were positive for THC. One of these patients reported smoking combustible marijuana. Urinary THC levels for four patients who reported using THC-containing products exceeded 400 ng/ml, indicating intensive use of THC or THC-containing products.”

About 40% of THC users and 65% of nicotine-product users reported using the product at least five times a day; 52% said they used combustible marijuana in addition to the vapes, and 24% reported also smoking combustible tobacco.

There was a very low level of concomitant drug use. Two patients reported using LSD; one reported misusing dextroamphetamine-amphetamine (Adderall), and one reported misusing oxycodone. Two tested positive for benzodiazepines and opioids, and one each for only benzodiazepines, only opioids, only amphetamines. One patient screened positive for unidentified narcotics.

and most products used were prepackaged, prefilled cartridges, according to new data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The majority of these products (66%) were THC-containing cartridges marketed under the brand name Dank. Dank cartridges are available at legal dispensaries and online in areas where they are legal. The Dank company posted a statement on its website warning buyers about fake cartridges and showing images of genuine cartridges. However, 89% of the cartridges were obtained on the street, from dealers, online, or from friends or social contacts, Jennifer Layden, MD, of the Illinois Department of Public Health said during a CDC telebriefing.

The illness was first recognized in Wisconsin and Illinois. Marijuana is illegal in Wisconsin; Illinois licensed recreational marijuana in 2009.

Other commonalties among cases have also emerged, Anne Schuchat, MD, deputy director of CDC, said during the call. More than two-thirds of the 805 confirmed or probable cases were male, and the median age was 23 years. The illness crosses age barriers, she said. About 62% were 18-24 years of age, and 54% under age 25. However, among the 12 deaths so far reported, the median age was 50 years. The age range was wide, from 27 to 71 years. Dr. Schuchat said data about medical comorbidities potentially linking the deaths is not yet available, although it is part of the ongoing investigation.

Other clinical commonalities included intensive use of THC-containing products and, in a small number of cases, concomitant use of benzodiazepenes, opioids, and narcotics.

Cases have now emerged in 46 states and in the U.S. Virgin Islands, although the number reported each week is dropping. However, this decrease may not represent a drop in newly occurring cases, but instead reflect delays in clinical recognition or reporting to local health departments, Dr. Schuchat said.

Regardless of the recent decline in reported cases, she said, the epidemic is serious, far reaching, and ongoing.

“I want to stress that this is a serious, life-threatening disease occurring mostly in otherwise healthy young people. These illnesses and deaths are occurring in the context of a dynamic marketplace with mix of products with mixes of ingredients, including potentially illicit substances. Users don’t know what’s in them and cannot tell from the ingredients listed on the packaging.”

Dr. Schuchat drew her data from two reports issued in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: a national case update by Peter A. Briss, MD, chair of CDC’s Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group, and colleagues, and a regional report coauthored by Dr. Layden of cases in Illinois and Wisconsin.

In the national report, 514 patients self-reported their history of e-cigarette and vaping use. Among those, 395 (76.9%) reported using THC-containing products, and 292 (56.8%) reported using nicotine-containing products in the 30 days preceding symptom onset. Almost half (210; 40.9%) reported using both THC- and nicotine-containing products.

But there appeared to be no clear pattern of use, said Dr. Briss, who also participated in the briefing. More than a third (185; 36.0%) reported exclusive use of THC-containing products, and 82 (16.0%) reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products.

The regional report added additional details.

Among the 86 patients who self-reported details, there were 234 unique cases of e-cigarette or THC vaping in 87 brands.

“Patients reported using numerous products and brands,” Dr. Layden noted. “Those who reported using THC products used an average of 2.1 different products and those who reported using nicotine products used about 1.3 different ones. Some patients reported using up to seven different brands, and these were used at least daily and sometimes numerous times in the day.”

According to the MMWR regional report, among the urinary THC screens obtained for 32 patients, “29 (91%) were positive for THC. One of these patients reported smoking combustible marijuana. Urinary THC levels for four patients who reported using THC-containing products exceeded 400 ng/ml, indicating intensive use of THC or THC-containing products.”

About 40% of THC users and 65% of nicotine-product users reported using the product at least five times a day; 52% said they used combustible marijuana in addition to the vapes, and 24% reported also smoking combustible tobacco.

There was a very low level of concomitant drug use. Two patients reported using LSD; one reported misusing dextroamphetamine-amphetamine (Adderall), and one reported misusing oxycodone. Two tested positive for benzodiazepines and opioids, and one each for only benzodiazepines, only opioids, only amphetamines. One patient screened positive for unidentified narcotics.

Growing vaping habit may lead to nicotine addiction in adolescents

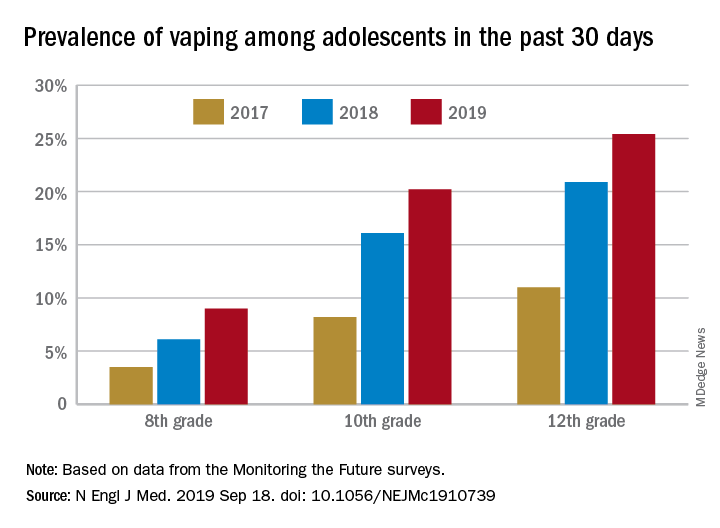

and in 2019 almost 12% of high school seniors reported that they were vaping every day, according to data from the Monitoring the Future surveys.

Daily use – defined as vaping on 20 or more of the previous 30 days – was reported by 6.9% of 10th-grade and 1.9% of 8th-grade respondents in the 2019 survey, which was the first time use in these age groups was assessed. “The substantial levels of daily vaping suggest the development of nicotine addiction,” Richard Miech, PhD, and associates said Sept. 18 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

From 2017 to 2019, e-cigarette use over the previous 30 days increased from 11.0% to 25.4% among 12th graders, from 8.2% to 20.2% in 10th graders, and from 3.5% to 9.0% of 8th graders, suggesting that “current efforts by the vaping industry, government agencies, and schools have thus far proved insufficient to stop the rapid spread of nicotine vaping among adolescents,” the investigators wrote.

By 2019, over 40% of 12th-grade students reported ever using e-cigarettes, along with more than 36% of 10th graders and almost 21% of 8th graders. Corresponding figures for past 12-month use were 35.1%, 31.1%, and 16.1%, they reported.

“New efforts are needed to protect youth from using nicotine during adolescence, when the developing brain is particularly susceptible to permanent changes from nicotine use and when almost all nicotine addiction is established,” the investigators wrote.

The analysis was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Dr. Miech.

SOURCE: Miech R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1910739.

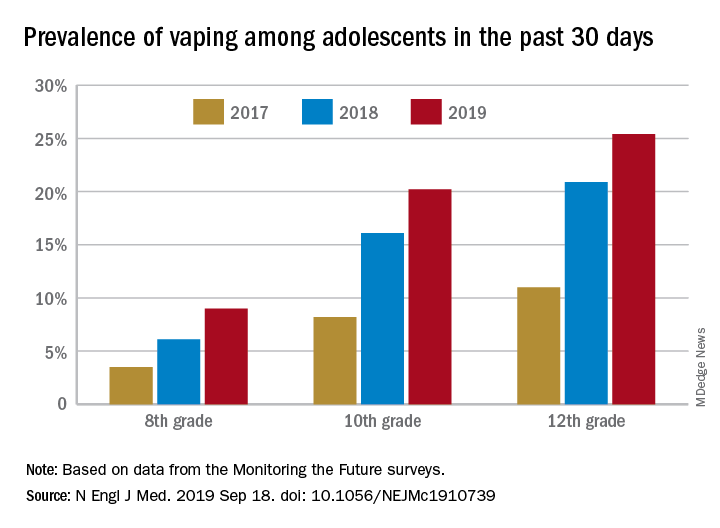

and in 2019 almost 12% of high school seniors reported that they were vaping every day, according to data from the Monitoring the Future surveys.

Daily use – defined as vaping on 20 or more of the previous 30 days – was reported by 6.9% of 10th-grade and 1.9% of 8th-grade respondents in the 2019 survey, which was the first time use in these age groups was assessed. “The substantial levels of daily vaping suggest the development of nicotine addiction,” Richard Miech, PhD, and associates said Sept. 18 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

From 2017 to 2019, e-cigarette use over the previous 30 days increased from 11.0% to 25.4% among 12th graders, from 8.2% to 20.2% in 10th graders, and from 3.5% to 9.0% of 8th graders, suggesting that “current efforts by the vaping industry, government agencies, and schools have thus far proved insufficient to stop the rapid spread of nicotine vaping among adolescents,” the investigators wrote.

By 2019, over 40% of 12th-grade students reported ever using e-cigarettes, along with more than 36% of 10th graders and almost 21% of 8th graders. Corresponding figures for past 12-month use were 35.1%, 31.1%, and 16.1%, they reported.

“New efforts are needed to protect youth from using nicotine during adolescence, when the developing brain is particularly susceptible to permanent changes from nicotine use and when almost all nicotine addiction is established,” the investigators wrote.

The analysis was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Dr. Miech.

SOURCE: Miech R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1910739.

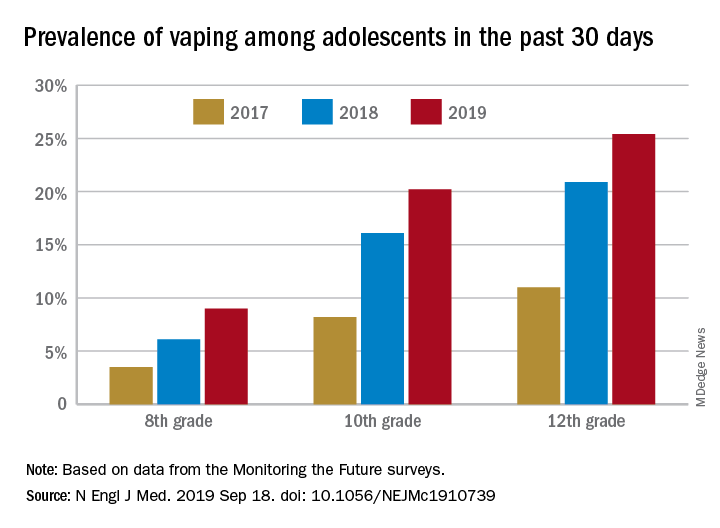

and in 2019 almost 12% of high school seniors reported that they were vaping every day, according to data from the Monitoring the Future surveys.

Daily use – defined as vaping on 20 or more of the previous 30 days – was reported by 6.9% of 10th-grade and 1.9% of 8th-grade respondents in the 2019 survey, which was the first time use in these age groups was assessed. “The substantial levels of daily vaping suggest the development of nicotine addiction,” Richard Miech, PhD, and associates said Sept. 18 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

From 2017 to 2019, e-cigarette use over the previous 30 days increased from 11.0% to 25.4% among 12th graders, from 8.2% to 20.2% in 10th graders, and from 3.5% to 9.0% of 8th graders, suggesting that “current efforts by the vaping industry, government agencies, and schools have thus far proved insufficient to stop the rapid spread of nicotine vaping among adolescents,” the investigators wrote.

By 2019, over 40% of 12th-grade students reported ever using e-cigarettes, along with more than 36% of 10th graders and almost 21% of 8th graders. Corresponding figures for past 12-month use were 35.1%, 31.1%, and 16.1%, they reported.

“New efforts are needed to protect youth from using nicotine during adolescence, when the developing brain is particularly susceptible to permanent changes from nicotine use and when almost all nicotine addiction is established,” the investigators wrote.

The analysis was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Dr. Miech.

SOURCE: Miech R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1910739.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Adolescents who use e-cigarettes every day may be developing nicotine addiction.

Major finding: In 2019, almost 12% of high school seniors were vaping every day.

Study details: Monitoring the Future surveys nationally representative samples of 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students each year.

Disclosures: The analysis was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Dr. Miech.

Source: Miech R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1910739.

CDC activates Emergency Operations Center to investigate vaping-associated lung injury

This move allows the CDC “to provide increased operational support” to CDC staff to meet the evolving challenges of the outbreak of vaping-related injuries and deaths, says a statement from the CDC.

“CDC has made it a priority to find out what is causing this outbreak,” noted CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD, in the statement.

The agency “continues to work closely with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to collect information about recent e-cigarette product use, or vaping, among patients and to test the substances or chemicals within e-cigarette products used by case patients,” according to the statement.

The CDC provided email addresses and site addresses for gathering information and communicating about e-cigarettes.

Information about the collection of e-cigarettes for possible testing by FDA can be obtained through contacting [email protected].

To communicate with CDC about this public health response, clinicians and health officials can contact [email protected].

More information on the current outbreak related to e-cigarettes is available at https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html.

General information on electronic cigarette products, can be found at www.cdc.gov/e-cigarettes.

Individuals concerned about health risks of vaping should consider refraining from e-cigarette use while the cases of lung injury are being investigated, the CDC said.

This move allows the CDC “to provide increased operational support” to CDC staff to meet the evolving challenges of the outbreak of vaping-related injuries and deaths, says a statement from the CDC.

“CDC has made it a priority to find out what is causing this outbreak,” noted CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD, in the statement.

The agency “continues to work closely with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to collect information about recent e-cigarette product use, or vaping, among patients and to test the substances or chemicals within e-cigarette products used by case patients,” according to the statement.

The CDC provided email addresses and site addresses for gathering information and communicating about e-cigarettes.

Information about the collection of e-cigarettes for possible testing by FDA can be obtained through contacting [email protected].

To communicate with CDC about this public health response, clinicians and health officials can contact [email protected].

More information on the current outbreak related to e-cigarettes is available at https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html.

General information on electronic cigarette products, can be found at www.cdc.gov/e-cigarettes.

Individuals concerned about health risks of vaping should consider refraining from e-cigarette use while the cases of lung injury are being investigated, the CDC said.

This move allows the CDC “to provide increased operational support” to CDC staff to meet the evolving challenges of the outbreak of vaping-related injuries and deaths, says a statement from the CDC.

“CDC has made it a priority to find out what is causing this outbreak,” noted CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD, in the statement.

The agency “continues to work closely with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to collect information about recent e-cigarette product use, or vaping, among patients and to test the substances or chemicals within e-cigarette products used by case patients,” according to the statement.

The CDC provided email addresses and site addresses for gathering information and communicating about e-cigarettes.

Information about the collection of e-cigarettes for possible testing by FDA can be obtained through contacting [email protected].

To communicate with CDC about this public health response, clinicians and health officials can contact [email protected].

More information on the current outbreak related to e-cigarettes is available at https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html.

General information on electronic cigarette products, can be found at www.cdc.gov/e-cigarettes.

Individuals concerned about health risks of vaping should consider refraining from e-cigarette use while the cases of lung injury are being investigated, the CDC said.

Educating teens, young adults about dangers of vaping

Physicians have been alarmed about the vaping craze for quite some time. This alarm has grown louder in the wake of news that electronic cigarettes have been associated with a mysterious lung disease.

Public health officials have reported that there have been 530 cases of vaping-related respiratory disease,1 and as of press time at least seven deaths had been attributed to vaping*. On Sept. 6, 2019, the Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and other health officials issued an investigation notice on vaping and e-cigarettes,2 cautioning teenagers, young adults, and pregnant women to avoid e-cigarettes completely and cautioning all users to never buy e-cigarettes off the street or from social sources.

A few days later, on Sept. 9, the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products issued a warning letter to JUUL Labs, makers of a popular e-cigarette, for illegal marketing of modified-risk tobacco products.3 Then on Sept. 10, health officials in Kansas reported that a sixth person has died of a lung illness related to vaping.4

Researchers have found that 80% of those diagnosed with the vaping illness used products that contained THC, the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana, 61% had used nicotine products, and 7% used cannabidiol (CBD) products. Vitamin E acetate is another substance identified in press reports as tied to the severe lung disease.

Most of the patients affected are adolescents and young adults, with the average age of 19 years.5 This comes as vaping among high school students rose 78% between 2017 and 2018.6 According the U.S. surgeon general, one in five teens vapes. Other data show that teen use of e-cigarettes comes with most users having never smoked a traditional cigarette.7 Teens and young adults frequently borrow buy* e-cigarette “pods” from gas stations but borrow and purchase from friends or peers. In addition, young people are known to alter the pods to insert other liquids, such as CBD and other marijuana products.

Teens and young adults are at higher risk for vaping complications. Their respiratory and immune systems are still developing. In addition to concerns about the recent surge of respiratory illnesses, nicotine is known to also suppress the immune system, which makes people who use it more susceptible to viral and bacterial infections – and also making it harder for them to recover.

In addition nicotine hyperactivates the reward centers of the brain, which can trigger addictive behaviors. Because the brains of young adults are not yet fully developed until at or after age 26, nicotine use before this can “prime the pump” of a still-developing brain, thereby increasing the likelihood for addiction to harder drugs. Nicotine has been shown to disrupt sleep patterns, which are critical for mental and physical health. Lastly, research shows that smoking increases the risks of various psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety. My teen and young adult patients have endlessly debated with me the idea that smoking – either nicotine or marijuana – eases their anxiety or helps them get to sleep. I tell them that, in the long run, the data show that smoking makes those problems worse.8-11

Nationally, we are seeing an explosion of multistate legislation pushing marijuana as a health food. E-cigarettes have followed as the “healthy” alternative to traditional tobacco. As clinicians, we must counter those messages.

Finally, our world is now filled with smartphones, sexting, and social media overuse. An entire peer group exists that knows life only with constant electronic stimulation. It is not without irony that our national nicotine obsessions have morphed from paper cigarettes to electronic versions. This raises questions: Are teens and young adults using e-cigarettes because of boredom? Are we witnessing a generational ADHD borne from restlessness that stems from lives with fewer meaningful face-to-face human interactions?

In addition to educating our teens and young adults about the physical risks tied to vaping, we need to teach them to build meaning into their lives that exists outside of this digital age.

Dr. Jorandby is chief medical officer of Lakeview Health in Jacksonville, Fla. She trained in addiction psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

References

1. CDC. Outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping. 2019 Sep 19.

2. CDC. Outbreak of lung illness associated with using e-cigarette products. Investigation notice. 2019 Sep 6.

3. FDA. Warning letter, JUUL Labs. 2019 Sep 9.

4. Sixth person dies of vaping-related illness. The Hill. 2019 Sep 10.

5. Layden JE. Pulmonary illness related to cigarette use in Illinois and Wisconsin – preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911614.

6. Cullen KA et al. CDC. MMWR. 2018 Nov 16;67(45):1276-7.

7. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. 2018.

8. Patton GC et al. Am J Public Health. 1996 Feb;86(2):225-30.

9. Leventhal AM et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2016 Feb;73:71-8.

10. Levine A et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017 Mar;56(3):214-2.

11. Leadbeater BJ et al. Addiction. 2019 Feb;114(2):278-93.

* This column was updated 9/24/2019.

Physicians have been alarmed about the vaping craze for quite some time. This alarm has grown louder in the wake of news that electronic cigarettes have been associated with a mysterious lung disease.

Public health officials have reported that there have been 530 cases of vaping-related respiratory disease,1 and as of press time at least seven deaths had been attributed to vaping*. On Sept. 6, 2019, the Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and other health officials issued an investigation notice on vaping and e-cigarettes,2 cautioning teenagers, young adults, and pregnant women to avoid e-cigarettes completely and cautioning all users to never buy e-cigarettes off the street or from social sources.

A few days later, on Sept. 9, the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products issued a warning letter to JUUL Labs, makers of a popular e-cigarette, for illegal marketing of modified-risk tobacco products.3 Then on Sept. 10, health officials in Kansas reported that a sixth person has died of a lung illness related to vaping.4

Researchers have found that 80% of those diagnosed with the vaping illness used products that contained THC, the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana, 61% had used nicotine products, and 7% used cannabidiol (CBD) products. Vitamin E acetate is another substance identified in press reports as tied to the severe lung disease.

Most of the patients affected are adolescents and young adults, with the average age of 19 years.5 This comes as vaping among high school students rose 78% between 2017 and 2018.6 According the U.S. surgeon general, one in five teens vapes. Other data show that teen use of e-cigarettes comes with most users having never smoked a traditional cigarette.7 Teens and young adults frequently borrow buy* e-cigarette “pods” from gas stations but borrow and purchase from friends or peers. In addition, young people are known to alter the pods to insert other liquids, such as CBD and other marijuana products.

Teens and young adults are at higher risk for vaping complications. Their respiratory and immune systems are still developing. In addition to concerns about the recent surge of respiratory illnesses, nicotine is known to also suppress the immune system, which makes people who use it more susceptible to viral and bacterial infections – and also making it harder for them to recover.

In addition nicotine hyperactivates the reward centers of the brain, which can trigger addictive behaviors. Because the brains of young adults are not yet fully developed until at or after age 26, nicotine use before this can “prime the pump” of a still-developing brain, thereby increasing the likelihood for addiction to harder drugs. Nicotine has been shown to disrupt sleep patterns, which are critical for mental and physical health. Lastly, research shows that smoking increases the risks of various psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety. My teen and young adult patients have endlessly debated with me the idea that smoking – either nicotine or marijuana – eases their anxiety or helps them get to sleep. I tell them that, in the long run, the data show that smoking makes those problems worse.8-11

Nationally, we are seeing an explosion of multistate legislation pushing marijuana as a health food. E-cigarettes have followed as the “healthy” alternative to traditional tobacco. As clinicians, we must counter those messages.

Finally, our world is now filled with smartphones, sexting, and social media overuse. An entire peer group exists that knows life only with constant electronic stimulation. It is not without irony that our national nicotine obsessions have morphed from paper cigarettes to electronic versions. This raises questions: Are teens and young adults using e-cigarettes because of boredom? Are we witnessing a generational ADHD borne from restlessness that stems from lives with fewer meaningful face-to-face human interactions?

In addition to educating our teens and young adults about the physical risks tied to vaping, we need to teach them to build meaning into their lives that exists outside of this digital age.

Dr. Jorandby is chief medical officer of Lakeview Health in Jacksonville, Fla. She trained in addiction psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

References

1. CDC. Outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping. 2019 Sep 19.

2. CDC. Outbreak of lung illness associated with using e-cigarette products. Investigation notice. 2019 Sep 6.

3. FDA. Warning letter, JUUL Labs. 2019 Sep 9.

4. Sixth person dies of vaping-related illness. The Hill. 2019 Sep 10.

5. Layden JE. Pulmonary illness related to cigarette use in Illinois and Wisconsin – preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911614.

6. Cullen KA et al. CDC. MMWR. 2018 Nov 16;67(45):1276-7.

7. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. 2018.

8. Patton GC et al. Am J Public Health. 1996 Feb;86(2):225-30.

9. Leventhal AM et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2016 Feb;73:71-8.

10. Levine A et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017 Mar;56(3):214-2.

11. Leadbeater BJ et al. Addiction. 2019 Feb;114(2):278-93.

* This column was updated 9/24/2019.

Physicians have been alarmed about the vaping craze for quite some time. This alarm has grown louder in the wake of news that electronic cigarettes have been associated with a mysterious lung disease.

Public health officials have reported that there have been 530 cases of vaping-related respiratory disease,1 and as of press time at least seven deaths had been attributed to vaping*. On Sept. 6, 2019, the Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and other health officials issued an investigation notice on vaping and e-cigarettes,2 cautioning teenagers, young adults, and pregnant women to avoid e-cigarettes completely and cautioning all users to never buy e-cigarettes off the street or from social sources.

A few days later, on Sept. 9, the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products issued a warning letter to JUUL Labs, makers of a popular e-cigarette, for illegal marketing of modified-risk tobacco products.3 Then on Sept. 10, health officials in Kansas reported that a sixth person has died of a lung illness related to vaping.4

Researchers have found that 80% of those diagnosed with the vaping illness used products that contained THC, the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana, 61% had used nicotine products, and 7% used cannabidiol (CBD) products. Vitamin E acetate is another substance identified in press reports as tied to the severe lung disease.

Most of the patients affected are adolescents and young adults, with the average age of 19 years.5 This comes as vaping among high school students rose 78% between 2017 and 2018.6 According the U.S. surgeon general, one in five teens vapes. Other data show that teen use of e-cigarettes comes with most users having never smoked a traditional cigarette.7 Teens and young adults frequently borrow buy* e-cigarette “pods” from gas stations but borrow and purchase from friends or peers. In addition, young people are known to alter the pods to insert other liquids, such as CBD and other marijuana products.

Teens and young adults are at higher risk for vaping complications. Their respiratory and immune systems are still developing. In addition to concerns about the recent surge of respiratory illnesses, nicotine is known to also suppress the immune system, which makes people who use it more susceptible to viral and bacterial infections – and also making it harder for them to recover.

In addition nicotine hyperactivates the reward centers of the brain, which can trigger addictive behaviors. Because the brains of young adults are not yet fully developed until at or after age 26, nicotine use before this can “prime the pump” of a still-developing brain, thereby increasing the likelihood for addiction to harder drugs. Nicotine has been shown to disrupt sleep patterns, which are critical for mental and physical health. Lastly, research shows that smoking increases the risks of various psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety. My teen and young adult patients have endlessly debated with me the idea that smoking – either nicotine or marijuana – eases their anxiety or helps them get to sleep. I tell them that, in the long run, the data show that smoking makes those problems worse.8-11

Nationally, we are seeing an explosion of multistate legislation pushing marijuana as a health food. E-cigarettes have followed as the “healthy” alternative to traditional tobacco. As clinicians, we must counter those messages.

Finally, our world is now filled with smartphones, sexting, and social media overuse. An entire peer group exists that knows life only with constant electronic stimulation. It is not without irony that our national nicotine obsessions have morphed from paper cigarettes to electronic versions. This raises questions: Are teens and young adults using e-cigarettes because of boredom? Are we witnessing a generational ADHD borne from restlessness that stems from lives with fewer meaningful face-to-face human interactions?

In addition to educating our teens and young adults about the physical risks tied to vaping, we need to teach them to build meaning into their lives that exists outside of this digital age.

Dr. Jorandby is chief medical officer of Lakeview Health in Jacksonville, Fla. She trained in addiction psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

References

1. CDC. Outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping. 2019 Sep 19.

2. CDC. Outbreak of lung illness associated with using e-cigarette products. Investigation notice. 2019 Sep 6.

3. FDA. Warning letter, JUUL Labs. 2019 Sep 9.

4. Sixth person dies of vaping-related illness. The Hill. 2019 Sep 10.

5. Layden JE. Pulmonary illness related to cigarette use in Illinois and Wisconsin – preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911614.

6. Cullen KA et al. CDC. MMWR. 2018 Nov 16;67(45):1276-7.

7. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. 2018.

8. Patton GC et al. Am J Public Health. 1996 Feb;86(2):225-30.

9. Leventhal AM et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2016 Feb;73:71-8.

10. Levine A et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017 Mar;56(3):214-2.

11. Leadbeater BJ et al. Addiction. 2019 Feb;114(2):278-93.

* This column was updated 9/24/2019.

Left ear pain

The FP suspected cutaneous vasculitis of the ear caused by levamisole-adulterated cocaine.

Levamisole is an antihelminthic drug approved for veterinary purposes. In the past, the drug had been used as an immune modulator in autoimmune disorders, but no longer is considered safe for human use, as it can cause agranulocytosis. Sellers around the world often lace cocaine with levamisole because it boosts the profits and potentiates the psychoactive effects of the cocaine. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to levamisole-adulterated cocaine has been reported many times in the literature.

Levamisole-associated vasculitis presents with ear purpura, retiform (like a net) purpura of the trunk or extremities, and neutropenia. Patients will test positive for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA). This cutaneous vasculitis also may present on the nose or face. There are reports of cocaine/levamisole-associated autoimmune syndrome involving agranulocytosis and cutaneous vasculitis.

The patient tested positive for pANCA, as was expected. The FP told her to discontinue her cocaine use, as she ran the risk of worse manifestations. She refused any treatment for her drug use and stated she could stop it on her own. The FP referred the patient to Dermatology, but the vasculitis was barely visible by the time she was seen. Convincing the patient not to use cocaine again remained the only treatment.

Photo courtesy of Jon Karnes, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected cutaneous vasculitis of the ear caused by levamisole-adulterated cocaine.

Levamisole is an antihelminthic drug approved for veterinary purposes. In the past, the drug had been used as an immune modulator in autoimmune disorders, but no longer is considered safe for human use, as it can cause agranulocytosis. Sellers around the world often lace cocaine with levamisole because it boosts the profits and potentiates the psychoactive effects of the cocaine. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to levamisole-adulterated cocaine has been reported many times in the literature.

Levamisole-associated vasculitis presents with ear purpura, retiform (like a net) purpura of the trunk or extremities, and neutropenia. Patients will test positive for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA). This cutaneous vasculitis also may present on the nose or face. There are reports of cocaine/levamisole-associated autoimmune syndrome involving agranulocytosis and cutaneous vasculitis.

The patient tested positive for pANCA, as was expected. The FP told her to discontinue her cocaine use, as she ran the risk of worse manifestations. She refused any treatment for her drug use and stated she could stop it on her own. The FP referred the patient to Dermatology, but the vasculitis was barely visible by the time she was seen. Convincing the patient not to use cocaine again remained the only treatment.

Photo courtesy of Jon Karnes, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected cutaneous vasculitis of the ear caused by levamisole-adulterated cocaine.

Levamisole is an antihelminthic drug approved for veterinary purposes. In the past, the drug had been used as an immune modulator in autoimmune disorders, but no longer is considered safe for human use, as it can cause agranulocytosis. Sellers around the world often lace cocaine with levamisole because it boosts the profits and potentiates the psychoactive effects of the cocaine. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to levamisole-adulterated cocaine has been reported many times in the literature.

Levamisole-associated vasculitis presents with ear purpura, retiform (like a net) purpura of the trunk or extremities, and neutropenia. Patients will test positive for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA). This cutaneous vasculitis also may present on the nose or face. There are reports of cocaine/levamisole-associated autoimmune syndrome involving agranulocytosis and cutaneous vasculitis.

The patient tested positive for pANCA, as was expected. The FP told her to discontinue her cocaine use, as she ran the risk of worse manifestations. She refused any treatment for her drug use and stated she could stop it on her own. The FP referred the patient to Dermatology, but the vasculitis was barely visible by the time she was seen. Convincing the patient not to use cocaine again remained the only treatment.

Photo courtesy of Jon Karnes, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

Trump administration finalizing ban on flavored e-cigarettes

The Food and Drug Administration is finalizing a compliance policy that will target flavored e-cigarettes and aim to clear the market of unauthorized, non–tobacco-flavored e-cigarette products, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex M. Azar II announced Sept. 11.

“The Trump administration is making it clear that we intend to clear the market of flavored e-cigarettes to reverse the deeply concerning epidemic of youth e-cigarette use that is impacting children, families, schools, and communities,” Mr. Azar said in a statement. “We will not stand idly by as these products become an on-ramp to combustible cigarettes or nicotine addiction for a generation of youth.”

The announcement comes as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state health departments track hundreds of lung-related illnesses that are linked to the use of e-cigarettes. At least 450 cases have been reported in 33 states and one jurisdiction. Diagnoses include lipoid pneumonia, alveolar hemorrhage, and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, according to a Sept. 6 press briefing by Ileana Arias, PhD, CDC acting deputy director for non-infectious diseases. Six deaths associated with the illnesses have been reported thus far.

Details of new regulatory action will be forthcoming and will outline enforcement policy for non–tobacco-flavored e-cigarette products that lack premarket authorization, HHS officials said. According to federal rules, all electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) products must file premarket tobacco product applications with the FDA within 2 years. Many ENDS products currently on the market are not being legally marketed and are subject to government action, according to the Trump administration.

“Once finalized, this compliance policy will serve as a powerful tool that the FDA can use to combat the troubling trend of youth e-cigarette use,” Ned Sharpless, MD, acting FDA commissioner, said in the statement. “We must act swiftly against flavored e-cigarette products that are especially attractive to children. Moreover, if we see a migration to tobacco-flavored products by kids, we will take additional steps to address youth use of these products.”

Federal officials noted that preliminary numbers from the National Youth Tobacco Survey show a continued rise in youth e-cigarette use, with more than a quarter of high school students current e-cigarette users in 2019. The overwhelming majority of youth e-cigarette users cited the use of fruit, menthol, or mint flavors, according to the preliminary data, which have not yet been published.

According to 2018 survey data, e-cigarette use increased from 12% to 21% among high school students and from 3% to 5% among middle school students from 2017 to 2018. There were 1.5 million more youth e-cigarette users in 2018 than in 2017, and youth who were using e-cigarettes were using them more often, according to the survey.

The Food and Drug Administration is finalizing a compliance policy that will target flavored e-cigarettes and aim to clear the market of unauthorized, non–tobacco-flavored e-cigarette products, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex M. Azar II announced Sept. 11.

“The Trump administration is making it clear that we intend to clear the market of flavored e-cigarettes to reverse the deeply concerning epidemic of youth e-cigarette use that is impacting children, families, schools, and communities,” Mr. Azar said in a statement. “We will not stand idly by as these products become an on-ramp to combustible cigarettes or nicotine addiction for a generation of youth.”

The announcement comes as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state health departments track hundreds of lung-related illnesses that are linked to the use of e-cigarettes. At least 450 cases have been reported in 33 states and one jurisdiction. Diagnoses include lipoid pneumonia, alveolar hemorrhage, and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, according to a Sept. 6 press briefing by Ileana Arias, PhD, CDC acting deputy director for non-infectious diseases. Six deaths associated with the illnesses have been reported thus far.

Details of new regulatory action will be forthcoming and will outline enforcement policy for non–tobacco-flavored e-cigarette products that lack premarket authorization, HHS officials said. According to federal rules, all electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) products must file premarket tobacco product applications with the FDA within 2 years. Many ENDS products currently on the market are not being legally marketed and are subject to government action, according to the Trump administration.

“Once finalized, this compliance policy will serve as a powerful tool that the FDA can use to combat the troubling trend of youth e-cigarette use,” Ned Sharpless, MD, acting FDA commissioner, said in the statement. “We must act swiftly against flavored e-cigarette products that are especially attractive to children. Moreover, if we see a migration to tobacco-flavored products by kids, we will take additional steps to address youth use of these products.”

Federal officials noted that preliminary numbers from the National Youth Tobacco Survey show a continued rise in youth e-cigarette use, with more than a quarter of high school students current e-cigarette users in 2019. The overwhelming majority of youth e-cigarette users cited the use of fruit, menthol, or mint flavors, according to the preliminary data, which have not yet been published.

According to 2018 survey data, e-cigarette use increased from 12% to 21% among high school students and from 3% to 5% among middle school students from 2017 to 2018. There were 1.5 million more youth e-cigarette users in 2018 than in 2017, and youth who were using e-cigarettes were using them more often, according to the survey.

The Food and Drug Administration is finalizing a compliance policy that will target flavored e-cigarettes and aim to clear the market of unauthorized, non–tobacco-flavored e-cigarette products, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex M. Azar II announced Sept. 11.

“The Trump administration is making it clear that we intend to clear the market of flavored e-cigarettes to reverse the deeply concerning epidemic of youth e-cigarette use that is impacting children, families, schools, and communities,” Mr. Azar said in a statement. “We will not stand idly by as these products become an on-ramp to combustible cigarettes or nicotine addiction for a generation of youth.”

The announcement comes as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state health departments track hundreds of lung-related illnesses that are linked to the use of e-cigarettes. At least 450 cases have been reported in 33 states and one jurisdiction. Diagnoses include lipoid pneumonia, alveolar hemorrhage, and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, according to a Sept. 6 press briefing by Ileana Arias, PhD, CDC acting deputy director for non-infectious diseases. Six deaths associated with the illnesses have been reported thus far.

Details of new regulatory action will be forthcoming and will outline enforcement policy for non–tobacco-flavored e-cigarette products that lack premarket authorization, HHS officials said. According to federal rules, all electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) products must file premarket tobacco product applications with the FDA within 2 years. Many ENDS products currently on the market are not being legally marketed and are subject to government action, according to the Trump administration.

“Once finalized, this compliance policy will serve as a powerful tool that the FDA can use to combat the troubling trend of youth e-cigarette use,” Ned Sharpless, MD, acting FDA commissioner, said in the statement. “We must act swiftly against flavored e-cigarette products that are especially attractive to children. Moreover, if we see a migration to tobacco-flavored products by kids, we will take additional steps to address youth use of these products.”

Federal officials noted that preliminary numbers from the National Youth Tobacco Survey show a continued rise in youth e-cigarette use, with more than a quarter of high school students current e-cigarette users in 2019. The overwhelming majority of youth e-cigarette users cited the use of fruit, menthol, or mint flavors, according to the preliminary data, which have not yet been published.

According to 2018 survey data, e-cigarette use increased from 12% to 21% among high school students and from 3% to 5% among middle school students from 2017 to 2018. There were 1.5 million more youth e-cigarette users in 2018 than in 2017, and youth who were using e-cigarettes were using them more often, according to the survey.

CDC, SAMHSA commit $1.8 billion to combat opioid crisis

More financial reinforcements are arriving in the battle against the opioid crisis, with the Trump administration promising more than $1.8 billion in new funds to help states address the crisis.

Speaking at a Sept. 4 press conference announcing the funding, President Donald Trump said the money will be used “to increase access to medication and medication-assisted treatment and mental health resources, which are critical for ending homelessness and getting people the help they deserve.” The president added that the grants also will help state and local governments obtain high-quality, comprehensive data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will provide more than $900 million in new funding over the next 3 years to “advance the understanding of the opioid overdose epidemic and to scale-up prevention and response activities,” the Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement announcing the funding.

“This money will help states and local communities track overdose data and develop strategies that save lives,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during the press conference.

He noted that, when the Trump administration began, overdose data were published with a 12-month lag. That lag has since shortened to 6 months. One of the goals with the new funding is to bring data publishing as close to real time as possible.

Separately, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded $932 million to all 50 states as part of its State Opioid Response grants, which “provide flexible funding to state governments to support prevention, treatment, and recovery services in the ways that meet the needs of their state,” according to the HHS statement.

That flexibility “can mean everything from expanding the use of medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice settings or in rural areas via telemedicine, to youth-focused community-based prevention efforts,” Secretary Azar explained. The funds can also support employment coaching and naloxone distribution, he added.

More financial reinforcements are arriving in the battle against the opioid crisis, with the Trump administration promising more than $1.8 billion in new funds to help states address the crisis.

Speaking at a Sept. 4 press conference announcing the funding, President Donald Trump said the money will be used “to increase access to medication and medication-assisted treatment and mental health resources, which are critical for ending homelessness and getting people the help they deserve.” The president added that the grants also will help state and local governments obtain high-quality, comprehensive data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will provide more than $900 million in new funding over the next 3 years to “advance the understanding of the opioid overdose epidemic and to scale-up prevention and response activities,” the Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement announcing the funding.

“This money will help states and local communities track overdose data and develop strategies that save lives,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during the press conference.

He noted that, when the Trump administration began, overdose data were published with a 12-month lag. That lag has since shortened to 6 months. One of the goals with the new funding is to bring data publishing as close to real time as possible.

Separately, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded $932 million to all 50 states as part of its State Opioid Response grants, which “provide flexible funding to state governments to support prevention, treatment, and recovery services in the ways that meet the needs of their state,” according to the HHS statement.

That flexibility “can mean everything from expanding the use of medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice settings or in rural areas via telemedicine, to youth-focused community-based prevention efforts,” Secretary Azar explained. The funds can also support employment coaching and naloxone distribution, he added.

More financial reinforcements are arriving in the battle against the opioid crisis, with the Trump administration promising more than $1.8 billion in new funds to help states address the crisis.

Speaking at a Sept. 4 press conference announcing the funding, President Donald Trump said the money will be used “to increase access to medication and medication-assisted treatment and mental health resources, which are critical for ending homelessness and getting people the help they deserve.” The president added that the grants also will help state and local governments obtain high-quality, comprehensive data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will provide more than $900 million in new funding over the next 3 years to “advance the understanding of the opioid overdose epidemic and to scale-up prevention and response activities,” the Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement announcing the funding.

“This money will help states and local communities track overdose data and develop strategies that save lives,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during the press conference.

He noted that, when the Trump administration began, overdose data were published with a 12-month lag. That lag has since shortened to 6 months. One of the goals with the new funding is to bring data publishing as close to real time as possible.

Separately, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded $932 million to all 50 states as part of its State Opioid Response grants, which “provide flexible funding to state governments to support prevention, treatment, and recovery services in the ways that meet the needs of their state,” according to the HHS statement.

That flexibility “can mean everything from expanding the use of medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice settings or in rural areas via telemedicine, to youth-focused community-based prevention efforts,” Secretary Azar explained. The funds can also support employment coaching and naloxone distribution, he added.

Multispecialty Opioid Risk Reduction Program Targeting Chronic Pain and Addiction Management in Veterans

Chronic pain significantly affects 100 million Americans.1,2 Pain accounts for $560 to $635 billion in annual financial costs to society, including health care costs and loss of productivity (ie, days missed from work, hours of work lost, and lower wages).2,3 Although pain prevalence exceeds other chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, cancer, and heart disease, it lacks a sufficient body of evidence-based research and guidelines on the underlying mechanisms, valid methods of assessment, and comparative effectiveness of treatments to effectively implement into clinical practice.2,4 Prevention and treatment of pain are often delayed, inaccessible, or inadequate.2 Primary care providers (PCPs) are most often sought for pain management and treat about 52% of chronic pain patients.2,3,5 Veterans are especially vulnerable to chronic pain and are at risk for inadequate treatment.2

Background

There is an epidemic of drug abuse and mortality from opioid prescription medication.6 In the US, rates of overdose deaths from prescription opioids were 6.1 per 100,000 for men and 4.2 per 100,000 for women in 2017. Opioids were involved in 47,600 overdose deaths in 2017, accounting for 67.8% of all drug overdose deaths.7

A large number of patients on long-term opioids have preexisting substance use disorders and/or psychiatric disease, further complicating chronic pain management.8-10 Prescription opioid use has been the precursor for about 80% of people who are now heroin addicts.11 Iatrogenic addiction from prescription medications isn’t easily captured by standard addiction criteria. Consequently, in patients who are on opioid therapy for prolonged periods, separating complex opioid dependence from addiction is difficult.12 Improved addiction screening and risk mitigation strategies are needed along with aggressive treatment monitoring to curb the opioid epidemic.

Opioid Management in Primary Care

The majority of opioid medications are prescribed by PCPs, which is magnified in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system due to the high prevalence of service-related injuries.3,13 The VA is at the forefront of addressing the complexities of opioid addiction through several initiatives.14 The ability to offer the frequent visits needed to safely manage patients prescribed opioids and the integration of mental health and addiction treatment are often lacking in non-VA primary care clinics. Therefore, a key to solving the opioid crisis is developing these capabilities so they can be delivered within the primary care setting. There is substantial evidence in support of nonopioid alternatives to chronic pain management, including other pharmacologic approaches, exercise, physical therapy, acupuncture, weight loss, smoking cessation, chiropractic care, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and other integrative health modalities.

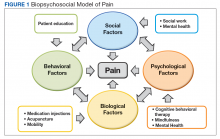

A 2009 VA directive mandated the development of a comprehensive, integrated, systemwide approach to pain management.15 The VA Stepped-Care Biopsychosocial Model for Pain Management is dependent on timely access to secondary consultation from pain medicine, behavioral health, physical medicine, and other specialty consultation.15

History of VHA SCAN-ECHO Model

The Specialty Care Access Network–Extension for Community Health Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) is a Veterans Health Administration (VHA) adaptation of a program that originated at the University of Mexico.16,17 The SCAN-ECHO model uses a multisite videoconferencing network to provide specialty care consultations to PCPs and patient aligned care teams (PACTs). During the 60- to 90-minute weekly sessions, case presentations are analyzed in real time so that over time, the PCPs gain knowledge, competency, and confidence in learning how to handle complex chronic conditions.

Since its implementation, the SCAN-ECHO program has been adopted across the VHA in a variety of specialties. One program, the SCAN-ECHO for Pain Management (SCAN-ECHO-PM) was implemented in 7 VHA networks in 31 states, spanning 47 medical centers and 148 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs).18 The SCAN-ECHO-PM program successfully conducted 257 multidisciplinary pain consultations between 2011 and 2013, resulting in increased initiation of nonopioid medications.18

The aim of this article is to describe the implementation of a multicomponent primary care-based pain clinic with a fully integrated mental health service and addiction service at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS). A practiced-based intervention of the biopsychosocial model with robust patient engagement has guided the development of the NF/SGVHS pain clinic (Figure 1).4,19

Pain CLinic

NF/SGVHS comprises the Malcom Randall and Lake City VA medical centers (VAMCs) hospitals, 3 satellite outpatient clinics, and 8 CBOCs. Spanning 33 counties in North Florida and 19 counties in South Georgia, the NF/SGVHS serves more than 140,000 patients. In 2010, the Malcom Randall VAMC established a multidisciplinary primary care pain clinic to manage veterans at high-risk for noncancer chronic pain and addiction. The noncancer pain policy was revised after garnering support from stakeholders who treat chronic pain, including the chiefs of psychiatry, rehabilitation medicine, neurosurgery, psychology, interventional pain, pharmacy, nursing, addiction medicine, and primary care. The clinic is staffed by primary care physicians trained in internal medicine and family medicine and is structured with 1-hour first visits, and 30-minute follow-up visits to allow enough time for comprehensive evaluation while meeting the needs for close follow-up support.

All physicians in the clinic have buprenorphine prescribing credentials to aid in the management of opioid addiction, as some patients feel more comfortable receiving addiction treatment in a primary care setting. The multimodal care model consists of several services that include addiction psychiatrists, interventional pain specialists, pain psychologists, and pain pharmacologists who coordinate the care to the veterans. The addiction psychiatrists offer a full range of services with inpatient residential and outpatient programs. Through recurring meetings with primary care pain clinic staff, the addiction psychiatrists are available to discuss use of buprenorphine and arrange follow-up for patients with complex pain addiction. There is ongoing collaboration to develop the best care plan that meets the patient’s needs for chronic pain, addiction, and/or mental health issues. The interventional pain service has 3 fellowship-trained pain care providers who deliver comprehensive evaluation, pharmacologic recommendations, and a full range of interventional and complementary therapies with an emphasis on objective functional improvement. Pain care providers offer alternatives to patients who are being weaned from opioids and support the multidisciplinary patient engagement model.

The pain psychology program, established in 2011, delivers CBT to 5 onsite locations and 5 telehealth locations. The service includes an advanced CBT program and a couples CBT program. The pharmacy pain fellowship program provides staff for an outpatient e-consult pain management service and an inpatient pharmacy consult service. Harnessing pain specialty pharmacists, the pharmacy service addresses pharmacokinetic issues, urine drug screen (UDS) results, opioid tapering and discharge planning for pain, addiction and mental health needs. The NF/SGVHS Primary Care Pain Clinic was established to support PCPs who did not feel comfortable managing chronic pain patients. These patients were typically on high-dose opioid therapy (> 100-mg morphine equivalent daily doses [MEDDs]); patients with a history of opioid addiction; patients with an addiction to opioids combined with benzodiazepines; and patients with comorbid medical issues (eg, sleep apnea), which complicated their management. The process of addressing opioid safety in these complex pain patients can be labor intensive and generally cannot be accomplished in a brief visit in a primary care setting where many other medical problems often need to be addressed.

Most patients on high-dose opioids are fearful of any changes in their medications. The difficult conversation regarding opioid safety is a lengthy one and frequently will occur over multiple visits. In addition, safely tapering opioids requires frequent follow-up to provide psychological support and to address withdrawal and mental health issues that may arise. As opioids are tapered, the clinic reinforces improved pain care through a multimodal biopsychosocial model. All veterans receiving pain care outside the VA are monitored annually to assure they are receiving evidence-based pain care as defined by the biopsychosocial model.

Education

Since 2011, the NF/SGVHS SCAN-ECHO pain and addiction educational forum has created > 50 hours of approved annual continuing medical education (CME) on pain management and addiction for PCPs. Initially, the 1-hour weekly educational audioconferences presented a pain management case along with related topics and involved specialists from interventional pain, physical therapy, psychiatry, nursing, neurology, and psychology departments. In 2013, in conjunction with the VA SCAN-ECHO program of Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC in Richmond, Virginia, and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, the audioconference was expanded to 2 days each week with additional topics on addiction management. Residency and fellowship rotations were developed that specifically targeted fellows from psychiatry, pharmacology, and interventional pain departments.

Currently, an 8-session pain school is delivered onsite and at 7 telehealth locations. The school is a collaborative effort involving interventional pain, psychology, pharmacy, nutrition, and the primary care pain clinic staff. As the cornerstone of the program, the pain school stresses the biopsychosocial patient engagement model.

Program Evaluation

The VA is equipped with multiple telehealth service networks that allow for the delivery of programs, such as the pain school, a pain psychology program, and a yoga program, onsite or offsite. The VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) manages electronic health records, allowing for rapid chart review and e-consults. The NF/SGVHS Pain Management Program provides about 1500 e-consults yearly. The CPRS includes templates with pain metrics to help PCPs deliver pain care more efficiently and evaluate performance measures. This system also allows for the capture of data to track improvements in the care of the veterans served.

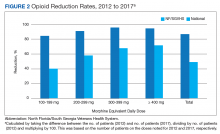

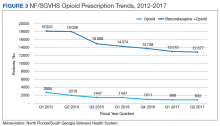

From 2012 to 2017, more than 5000 NF/SGVHS patients were weaned from opioids. Overall, there was an 87% reduction in patients receiving opioids ( ≥ 100-mg MEDDs) within the NF/SGVHS, which is significantly more than the 49% seen nationally across the VHA (Figure 2). Percent reduction was calculated by taking the difference in number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and 2017, dividing by the number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and multiplying by 100. The largest proportion of opioid dose reductions for NF/SGVHS and VHA patients, respectively, were seen in 300-mg to 399-mg MEDDs (95% vs 67%, respectively); followed by ≥ 400-mg MEDDs (94% vs 71%, respectively); 200-mg to 299-mg MEDDs (91% vs 58%, respectively); and 100-mg to 199-mg MEDDs (84% vs 40%, respectively). When examining NF/SGVHS trends over time, there has been a consistent decline in patients prescribed opioids (18 223 in 2012 compared with 12 877 in 2017) with similar trends in benzodiazepine-opioid combination therapy (2694 in 2012 compared with 833 in 2017) (Figure 3).

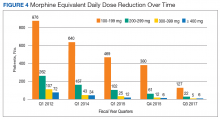

Similar declines are seen when patients are stratified by the MEDD (Figure 4). From 2012 to 2017, 92% of the patients were successfully tapered off doses ≥ 400-mg MEDD (2012, n = 72; 2017, n = 6), and tapered off 300-mg to 399-mg MEDD (2012, n = 107; 2017, n = 5); 95% were tapered off 200-mg to 299-mg MEDD (2012, n = 262; 2017, n = 22); and 86% were tapered off 100-mg to 199-mg MEDD (2012, n = 876; 2017; n = 127).

Conclusion

Successful integration of primary care with mental health and addiction services is paramount to aggressively taper patients with chronic pain from opioids. There is evidence that drug dependence and chronic pain should be treated like other chronic illness.20 Both chronic pain and addiction can be treated with a multidimensional self-management approach. In view of the high incidence of mental health and addiction associated with opioid use, it makes sense that an integrated, 1-stop pain and addiction clinic that understands and addresses both issues is more likely to improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported by the resources and facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Geriatric Research Education Clinical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

1. Dueñas M, Ojeda B, Salazar A, Mico JA, Failde I. A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. J Pain Res. 2016;9:457-467.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011.

3. Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103(8):738-747.

4. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):119-130.

5. Meghani SH, Polomano RC, Tait RC, Vallerand AH, Anderson KO, Gallagher RM. Advancing a national agenda to eliminate disparities in pain care: directions for health policy, education, practice, and research. Pain Med. 2012;13(1):5-28.

6. McHugh RK, Nielsen S, Weiss RD. Prescription drug abuse: from epidemiology to public policy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48(1):1-7.

7. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths-United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419-1427.

8. Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan MY, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(1):1-8.

9. Højsted J, Sjøgren P. Addiction to opioids in chronic pain patients: a literature review. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(5):490-518.

10. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947.

11. Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:559-574.

12. Ballantyne JC, Sullivan MD, Kolodny A. Opioid dependence vs addiction: a distinction without a difference? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1342-1343.

13. Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409-413.

14. Gellad WF, Good CB, Shulkin DJ. Addressing the opioid epidemic in the United States: lessons from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):611-612.

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran Health Administration Directive 2009-053, Pain Management. https://www.va.gov/painmanagement/docs/vha09paindirective.pdf. Published October 28, 2009. Accessed August 19, 2019.

16. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

17. Kirsh S, Su GL, Sales A, Jain R. Access to outpatient specialty care: solutions from an integrated health care system. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(1):88-90.

18. Frank JW, Carey EP, Fagan KM, et al. Evaluation of a telementoring intervention for pain management in the Veterans Health Administration. Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1090-1100.

19. Fillingim RB. Individual differences in pain: understanding the mosaic that makes pain personal. Pain. 2017;158 (suppl 1):S11-S18.

20. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689-1695.