User login

Tackling unhealthy substance use using USPSTF guidance and a 1-question tool

References

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Unhealthy drug use: screening [final recommendation statement]. Published June 9, 2020. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-screening. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Illicit drug use in children, adolescents, and young adults: primary care-based interventions [final recommendation statement]. Published May 26, 2020. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-primary-care-interventions-for-children-and-adolescents. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions [final recommendation statement]. Published April 28, 2020. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA Quick Screen v 1.0. www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/nmassist.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions [update in progress]. Published September 21, 2015. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions. Accessed July 28, 2020.

References

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Unhealthy drug use: screening [final recommendation statement]. Published June 9, 2020. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-screening. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Illicit drug use in children, adolescents, and young adults: primary care-based interventions [final recommendation statement]. Published May 26, 2020. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-primary-care-interventions-for-children-and-adolescents. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions [final recommendation statement]. Published April 28, 2020. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA Quick Screen v 1.0. www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/nmassist.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions [update in progress]. Published September 21, 2015. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions. Accessed July 28, 2020.

References

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Unhealthy drug use: screening [final recommendation statement]. Published June 9, 2020. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-screening. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Illicit drug use in children, adolescents, and young adults: primary care-based interventions [final recommendation statement]. Published May 26, 2020. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-primary-care-interventions-for-children-and-adolescents. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions [final recommendation statement]. Published April 28, 2020. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA Quick Screen v 1.0. www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/nmassist.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions [update in progress]. Published September 21, 2015. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions. Accessed July 28, 2020.

AMA urges change after dramatic increase in illicit opioid fatalities

In the past 5 years, there has been a significant drop in the use of prescription opioids and in deaths associated with such use; but at the same time there’s been a dramatic increase in fatalities involving illicit opioids and stimulants, a new report from the American Medical Association (AMA) Opioid Task Force shows.

Although the medical community has made some important progress against the opioid epidemic, with a 37% reduction in opioid prescribing since 2013, illicit drugs are now the dominant reason why drug overdoses kill more than 70,000 people each year, the report says.

In an effort to improve the situation, the AMA Opioid Task Force is urging the removal of barriers to evidence-based care for patients who have pain and for those who have substance use disorders (SUDs). The report notes that “red tape and misguided policies are grave dangers” to these patients.

“It is critically important as we see drug overdoses increasing that we work towards reducing barriers of care for substance use abusers,” Task Force Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in an interview.

“At present, the status quo is killing far too many of our loved ones and wreaking havoc in our communities,” she said.

Dr. Harris noted that “a more coordinated/integrated approach” is needed to help individuals with SUDs.

“It is vitally important that these individuals can get access to treatment. Everyone deserves the opportunity for care,” she added.

Dramatic increases

The report cites figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that indicate the following regarding the period from the beginning of 2015 to the end of 2019:

- Deaths involving illicitly manufactured and fentanyl analogues increased from 5,766 to 36,509.

- Deaths involving stimulants such as increased from 4,402 to 16,279.

- Deaths involving cocaine increased from 5,496 to 15,974.

- Deaths involving heroin increased from 10,788 to 14,079.

- Deaths involving prescription opioids decreased from 12,269 to 11,904.

The report notes that deaths involving prescription opioids peaked in July 2017 at 15,003.

Some good news

In addition to the 37% reduction in opioid prescribing in recent years, the AMA lists other points of progress, such as a large increase in prescription drug monitoring program registrations. More than 1.8 million physicians and other healthcare professionals now participate in these programs.

Also, more physicians are now certified to treat opioid use disorder. More than 85,000 physicians, as well as a growing number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants, are now certified to treat patients in the office with buprenorphine. This represents an increase of more than 50,000 from 2017.

Access to naloxone is also increasing. More than 1 million naloxone prescriptions were dispensed in 2019 – nearly double the amount in 2018. This represents a 649% increase from 2017.

“We have made some good progress, but we can’t declare victory, and there are far too many barriers to getting treatment for substance use disorder,” Dr. Harris said.

“Policymakers, public health officials, and insurance companies need to come together to create a system where there are no barriers to care for people with substance use disorder and for those needing pain medications,” she added.

At present, prior authorization is often needed before these patients can receive medication. “This involves quite a bit of administration, filling in forms, making phone calls, and this is stopping people getting the care they need,” said Dr. Harris.

“This is a highly regulated environment. There are also regulations on the amount of methadone that can be prescribed and for the prescription of buprenorphine, which has to be initiated in person,” she said.

Will COVID-19 bring change?

Dr. Harris noted that some of these regulations have been relaxed during the COVID-19 crisis so that physicians could ensure that patients have continued access to medication, and she suggested that this may pave the way for the future.

“We need now to look at this carefully and have a conversation about whether these relaxations can be continued. But this would have to be evidence based. Perhaps we can use experience from the COVID-19 period to guide future policy on this,” she said.

The report highlights that despite medical society and patient advocacy, only 21 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws that limit public and private insurers from imposing prior authorization requirements on SUD services or medications.

The Task Force urges removal of remaining prior authorizations, step therapy, and other inappropriate administrative burdens that delay or deny care for Food and Drug Administration–approved medications used as part of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.

The organization is also calling for better implementation of mental health and substance use disorder parity laws that require health insurers to provide the same level of benefits for mental health and SUD treatment and services that they do for medical/surgical care.

At present, only a few states have taken meaningful action to enact or enforce those laws, the report notes.

The Task Force also recommends the implementation of systems to track overdose and mortality trends to provide equitable public health interventions. These measures would include comprehensive, disaggregated racial and ethnic data collection related to testing, hospitalization, and mortality associated with opioids and other substances.

“We know that ending the drug overdose epidemic will not be easy, but if policymakers allow the status quo to continue, it will be impossible,” Dr. Harris said.

“ Physicians will continue to do our part. We urge policymakers to do theirs,” she added.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In the past 5 years, there has been a significant drop in the use of prescription opioids and in deaths associated with such use; but at the same time there’s been a dramatic increase in fatalities involving illicit opioids and stimulants, a new report from the American Medical Association (AMA) Opioid Task Force shows.

Although the medical community has made some important progress against the opioid epidemic, with a 37% reduction in opioid prescribing since 2013, illicit drugs are now the dominant reason why drug overdoses kill more than 70,000 people each year, the report says.

In an effort to improve the situation, the AMA Opioid Task Force is urging the removal of barriers to evidence-based care for patients who have pain and for those who have substance use disorders (SUDs). The report notes that “red tape and misguided policies are grave dangers” to these patients.

“It is critically important as we see drug overdoses increasing that we work towards reducing barriers of care for substance use abusers,” Task Force Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in an interview.

“At present, the status quo is killing far too many of our loved ones and wreaking havoc in our communities,” she said.

Dr. Harris noted that “a more coordinated/integrated approach” is needed to help individuals with SUDs.

“It is vitally important that these individuals can get access to treatment. Everyone deserves the opportunity for care,” she added.

Dramatic increases

The report cites figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that indicate the following regarding the period from the beginning of 2015 to the end of 2019:

- Deaths involving illicitly manufactured and fentanyl analogues increased from 5,766 to 36,509.

- Deaths involving stimulants such as increased from 4,402 to 16,279.

- Deaths involving cocaine increased from 5,496 to 15,974.

- Deaths involving heroin increased from 10,788 to 14,079.

- Deaths involving prescription opioids decreased from 12,269 to 11,904.

The report notes that deaths involving prescription opioids peaked in July 2017 at 15,003.

Some good news

In addition to the 37% reduction in opioid prescribing in recent years, the AMA lists other points of progress, such as a large increase in prescription drug monitoring program registrations. More than 1.8 million physicians and other healthcare professionals now participate in these programs.

Also, more physicians are now certified to treat opioid use disorder. More than 85,000 physicians, as well as a growing number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants, are now certified to treat patients in the office with buprenorphine. This represents an increase of more than 50,000 from 2017.

Access to naloxone is also increasing. More than 1 million naloxone prescriptions were dispensed in 2019 – nearly double the amount in 2018. This represents a 649% increase from 2017.

“We have made some good progress, but we can’t declare victory, and there are far too many barriers to getting treatment for substance use disorder,” Dr. Harris said.

“Policymakers, public health officials, and insurance companies need to come together to create a system where there are no barriers to care for people with substance use disorder and for those needing pain medications,” she added.

At present, prior authorization is often needed before these patients can receive medication. “This involves quite a bit of administration, filling in forms, making phone calls, and this is stopping people getting the care they need,” said Dr. Harris.

“This is a highly regulated environment. There are also regulations on the amount of methadone that can be prescribed and for the prescription of buprenorphine, which has to be initiated in person,” she said.

Will COVID-19 bring change?

Dr. Harris noted that some of these regulations have been relaxed during the COVID-19 crisis so that physicians could ensure that patients have continued access to medication, and she suggested that this may pave the way for the future.

“We need now to look at this carefully and have a conversation about whether these relaxations can be continued. But this would have to be evidence based. Perhaps we can use experience from the COVID-19 period to guide future policy on this,” she said.

The report highlights that despite medical society and patient advocacy, only 21 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws that limit public and private insurers from imposing prior authorization requirements on SUD services or medications.

The Task Force urges removal of remaining prior authorizations, step therapy, and other inappropriate administrative burdens that delay or deny care for Food and Drug Administration–approved medications used as part of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.

The organization is also calling for better implementation of mental health and substance use disorder parity laws that require health insurers to provide the same level of benefits for mental health and SUD treatment and services that they do for medical/surgical care.

At present, only a few states have taken meaningful action to enact or enforce those laws, the report notes.

The Task Force also recommends the implementation of systems to track overdose and mortality trends to provide equitable public health interventions. These measures would include comprehensive, disaggregated racial and ethnic data collection related to testing, hospitalization, and mortality associated with opioids and other substances.

“We know that ending the drug overdose epidemic will not be easy, but if policymakers allow the status quo to continue, it will be impossible,” Dr. Harris said.

“ Physicians will continue to do our part. We urge policymakers to do theirs,” she added.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In the past 5 years, there has been a significant drop in the use of prescription opioids and in deaths associated with such use; but at the same time there’s been a dramatic increase in fatalities involving illicit opioids and stimulants, a new report from the American Medical Association (AMA) Opioid Task Force shows.

Although the medical community has made some important progress against the opioid epidemic, with a 37% reduction in opioid prescribing since 2013, illicit drugs are now the dominant reason why drug overdoses kill more than 70,000 people each year, the report says.

In an effort to improve the situation, the AMA Opioid Task Force is urging the removal of barriers to evidence-based care for patients who have pain and for those who have substance use disorders (SUDs). The report notes that “red tape and misguided policies are grave dangers” to these patients.

“It is critically important as we see drug overdoses increasing that we work towards reducing barriers of care for substance use abusers,” Task Force Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in an interview.

“At present, the status quo is killing far too many of our loved ones and wreaking havoc in our communities,” she said.

Dr. Harris noted that “a more coordinated/integrated approach” is needed to help individuals with SUDs.

“It is vitally important that these individuals can get access to treatment. Everyone deserves the opportunity for care,” she added.

Dramatic increases

The report cites figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that indicate the following regarding the period from the beginning of 2015 to the end of 2019:

- Deaths involving illicitly manufactured and fentanyl analogues increased from 5,766 to 36,509.

- Deaths involving stimulants such as increased from 4,402 to 16,279.

- Deaths involving cocaine increased from 5,496 to 15,974.

- Deaths involving heroin increased from 10,788 to 14,079.

- Deaths involving prescription opioids decreased from 12,269 to 11,904.

The report notes that deaths involving prescription opioids peaked in July 2017 at 15,003.

Some good news

In addition to the 37% reduction in opioid prescribing in recent years, the AMA lists other points of progress, such as a large increase in prescription drug monitoring program registrations. More than 1.8 million physicians and other healthcare professionals now participate in these programs.

Also, more physicians are now certified to treat opioid use disorder. More than 85,000 physicians, as well as a growing number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants, are now certified to treat patients in the office with buprenorphine. This represents an increase of more than 50,000 from 2017.

Access to naloxone is also increasing. More than 1 million naloxone prescriptions were dispensed in 2019 – nearly double the amount in 2018. This represents a 649% increase from 2017.

“We have made some good progress, but we can’t declare victory, and there are far too many barriers to getting treatment for substance use disorder,” Dr. Harris said.

“Policymakers, public health officials, and insurance companies need to come together to create a system where there are no barriers to care for people with substance use disorder and for those needing pain medications,” she added.

At present, prior authorization is often needed before these patients can receive medication. “This involves quite a bit of administration, filling in forms, making phone calls, and this is stopping people getting the care they need,” said Dr. Harris.

“This is a highly regulated environment. There are also regulations on the amount of methadone that can be prescribed and for the prescription of buprenorphine, which has to be initiated in person,” she said.

Will COVID-19 bring change?

Dr. Harris noted that some of these regulations have been relaxed during the COVID-19 crisis so that physicians could ensure that patients have continued access to medication, and she suggested that this may pave the way for the future.

“We need now to look at this carefully and have a conversation about whether these relaxations can be continued. But this would have to be evidence based. Perhaps we can use experience from the COVID-19 period to guide future policy on this,” she said.

The report highlights that despite medical society and patient advocacy, only 21 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws that limit public and private insurers from imposing prior authorization requirements on SUD services or medications.

The Task Force urges removal of remaining prior authorizations, step therapy, and other inappropriate administrative burdens that delay or deny care for Food and Drug Administration–approved medications used as part of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.

The organization is also calling for better implementation of mental health and substance use disorder parity laws that require health insurers to provide the same level of benefits for mental health and SUD treatment and services that they do for medical/surgical care.

At present, only a few states have taken meaningful action to enact or enforce those laws, the report notes.

The Task Force also recommends the implementation of systems to track overdose and mortality trends to provide equitable public health interventions. These measures would include comprehensive, disaggregated racial and ethnic data collection related to testing, hospitalization, and mortality associated with opioids and other substances.

“We know that ending the drug overdose epidemic will not be easy, but if policymakers allow the status quo to continue, it will be impossible,” Dr. Harris said.

“ Physicians will continue to do our part. We urge policymakers to do theirs,” she added.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Stress, COVID-19 contribute to mental health concerns in college students

Socioeconomic, technological, cultural, and historical conditions are contributing to a mental health crisis among college students in the United States, according to Anthony L. Rostain, MD, MA, in a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

A recent National College Health Assessment published in fall of 2018 by the American College Health Association found that one in four college students had some kind of diagnosable mental illness, and 44% had symptoms of depression within the past year.

The assessment also found that college students felt overwhelmed (86%), felt sad (68%), felt very lonely (63%), had overwhelming anxiety (62%), experienced feelings of hopelessness (53%), or were depressed to the point where functioning was difficult (41%), all of which was higher than in previous years. Students also were more likely than in previous years to engage in interpersonal violence (17%), seriously consider suicide (11%), intentionally hurt themselves (7.4%), and attempt suicide (1.9%). According to the organization Active Minds, suicide is a leading cause of death in college students.

This shift in mental health for individuals in Generation Z, those born between the mid-1990s and early 2010s, can be attributed to historical events since the turn of the century, Dr. Rostain said at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education. The Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the financial crisis of 2007-2008, school shootings, globalization leading to economic uncertainty, the 24-hour news cycle and continuous media exposure, and the influence of the Internet have all influenced Gen Z’s identity.

“Growing up immersed in the Internet certainly has its advantages, but also maybe created some vulnerabilities in our young people,” he said.

Concerns about climate change, the burden of higher education and student debt, and the COVID-19 pandemic also have contributed to anxiety in this group. In a spring survey of students published by Active Minds about COVID-19 and its impact on mental health, 91% of students reported having stress or anxiety, 81% were disappointed or sad, 80% said they felt lonely or isolated, 56% had relocated as a result of the pandemic, and 48% reported financial setbacks tied to COVID-19.

“Anxiety seems to have become a feature of modern life,” said Dr. Rostain, who is director of education at the department of psychiatry and professor of psychiatry at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“Our culture, which often has a prominent emotional tone of fear, tends to promote cognitive distortions in which everyone is perceiving danger at every turn.” in this group, he noted. While people should be washing their hands and staying safe through social distancing during the pandemic, “we don’t want people to stop functioning, planning the future, and really in college students’ case, studying and getting ready for their careers,” he said. Parents can hinder those goals through intensively parenting or “overparenting” their children, which can result in destructive perfectionism, anxiety and depression, abject fear of failure and risk avoidance, and a focus on the external aspects of life rather than internal feelings.

Heavier alcohol use and amphetamine use also is on the rise in college students, Dr. Rostain said. Increased stimulant use in young adults is attributed to greater access to prescription drugs prior to college, greater prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), peer pressure, and influence from marketing and media messaging, he said. Another important change is the rise of smartphones and the Internet, which might drive the need to be constantly connected and compete for attention.

“This is the first generation who had constant access to the Internet. Smartphones in particular are everywhere, and we think this is another important factor in considering what might be happening to young people,” Dr. Rostain said.

Developing problem-solving and conflict resolution skills, developing coping mechanisms, being able to regulate emotions, finding optimism toward the future, having access to mental health services, and having cultural or religious beliefs with a negative view of suicide are all protective factors that promote resiliency in young people, Dr. Rostain said. Other protective factors include the development of socio-emotional readiness skills, such as conscientiousness, self-management, interpersonal skills, self-control, task persistence, risk management, self-acceptance, and having an open mindset or seeking help when needed. However, he noted, family is one area that can be both a help or a risk to mental health.

“Family attachments and supportive relationships in the family are really critical in predicting good outcomes. By the same token, families that are conflicted, where there’s a lot of stress or there’s a lot of turmoil and/or where resources are not available, that may be a risk factor to coping in young adulthood,” he said.

Individual resilience can be developed through learning from mistakes and overcoming mindset barriers, such as feelings of not belonging, concerns about disappointing one’s parents, worries about not making it, or fears of being different.

On campus, best practices and emerging trends include wellness and resiliency programs, reducing stigma, engagement from students, training of faculty and staff, crisis management plans, telehealth counseling, substance abuse programs, postvention support after suicide, collaboration with mental health providers, and support for diverse populations.

“The best schools are the ones that promote communication and that invite families to be involved early on because parents and families can be and need to be educated about what to do to prevent adverse outcomes of young people who are really at risk,” Dr. Rostain said. “It takes a village to raise a child, and it takes the same village to bring someone from adolescence to young adulthood.”

Family-based intervention has also shown promise, he said, but clinicians should watch for signs that a family is not willing to undergo therapy, is scapegoating a college student, or there are signs of boundary violations, violence, or sexual abuse in the family – or attempts to undermine treatment.

Specific to COVID-19, campus mental health services should focus on routine, self-care, physical activity, and connections with other people while also space for grieving lost experiences, facing uncertainty, developing resilience, and finding meaning. In the family, challenges around COVID-19 can include issues of physical distancing and quarantine, anxiety about becoming infected with the virus, economic insecurity, managing conflicts, setting and enforcing boundaries in addition to providing mutual support, and finding new meaning during the pandemic.

“I think these are the challenges, but we think this whole process of people living together and handling life in a way they’ve never expected to may hold some silver linings,” Dr. Rostain said. “It may be a way of addressing many issues that were never addressed before the young person went off to college.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Rostain reported receiving royalties from Routledge/Taylor Francis Group and St. Martin’s Press, scientific advisory board honoraria from Arbor and Shire/Takeda, consulting fees from the National Football League and Tris Pharmaceuticals, and has presented CME sessions for American Psychiatric Publishing, Global Medical Education, Shire/Takeda, and the U.S. Psychiatric Congress.

Socioeconomic, technological, cultural, and historical conditions are contributing to a mental health crisis among college students in the United States, according to Anthony L. Rostain, MD, MA, in a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

A recent National College Health Assessment published in fall of 2018 by the American College Health Association found that one in four college students had some kind of diagnosable mental illness, and 44% had symptoms of depression within the past year.

The assessment also found that college students felt overwhelmed (86%), felt sad (68%), felt very lonely (63%), had overwhelming anxiety (62%), experienced feelings of hopelessness (53%), or were depressed to the point where functioning was difficult (41%), all of which was higher than in previous years. Students also were more likely than in previous years to engage in interpersonal violence (17%), seriously consider suicide (11%), intentionally hurt themselves (7.4%), and attempt suicide (1.9%). According to the organization Active Minds, suicide is a leading cause of death in college students.

This shift in mental health for individuals in Generation Z, those born between the mid-1990s and early 2010s, can be attributed to historical events since the turn of the century, Dr. Rostain said at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education. The Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the financial crisis of 2007-2008, school shootings, globalization leading to economic uncertainty, the 24-hour news cycle and continuous media exposure, and the influence of the Internet have all influenced Gen Z’s identity.

“Growing up immersed in the Internet certainly has its advantages, but also maybe created some vulnerabilities in our young people,” he said.

Concerns about climate change, the burden of higher education and student debt, and the COVID-19 pandemic also have contributed to anxiety in this group. In a spring survey of students published by Active Minds about COVID-19 and its impact on mental health, 91% of students reported having stress or anxiety, 81% were disappointed or sad, 80% said they felt lonely or isolated, 56% had relocated as a result of the pandemic, and 48% reported financial setbacks tied to COVID-19.

“Anxiety seems to have become a feature of modern life,” said Dr. Rostain, who is director of education at the department of psychiatry and professor of psychiatry at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“Our culture, which often has a prominent emotional tone of fear, tends to promote cognitive distortions in which everyone is perceiving danger at every turn.” in this group, he noted. While people should be washing their hands and staying safe through social distancing during the pandemic, “we don’t want people to stop functioning, planning the future, and really in college students’ case, studying and getting ready for their careers,” he said. Parents can hinder those goals through intensively parenting or “overparenting” their children, which can result in destructive perfectionism, anxiety and depression, abject fear of failure and risk avoidance, and a focus on the external aspects of life rather than internal feelings.

Heavier alcohol use and amphetamine use also is on the rise in college students, Dr. Rostain said. Increased stimulant use in young adults is attributed to greater access to prescription drugs prior to college, greater prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), peer pressure, and influence from marketing and media messaging, he said. Another important change is the rise of smartphones and the Internet, which might drive the need to be constantly connected and compete for attention.

“This is the first generation who had constant access to the Internet. Smartphones in particular are everywhere, and we think this is another important factor in considering what might be happening to young people,” Dr. Rostain said.

Developing problem-solving and conflict resolution skills, developing coping mechanisms, being able to regulate emotions, finding optimism toward the future, having access to mental health services, and having cultural or religious beliefs with a negative view of suicide are all protective factors that promote resiliency in young people, Dr. Rostain said. Other protective factors include the development of socio-emotional readiness skills, such as conscientiousness, self-management, interpersonal skills, self-control, task persistence, risk management, self-acceptance, and having an open mindset or seeking help when needed. However, he noted, family is one area that can be both a help or a risk to mental health.

“Family attachments and supportive relationships in the family are really critical in predicting good outcomes. By the same token, families that are conflicted, where there’s a lot of stress or there’s a lot of turmoil and/or where resources are not available, that may be a risk factor to coping in young adulthood,” he said.

Individual resilience can be developed through learning from mistakes and overcoming mindset barriers, such as feelings of not belonging, concerns about disappointing one’s parents, worries about not making it, or fears of being different.

On campus, best practices and emerging trends include wellness and resiliency programs, reducing stigma, engagement from students, training of faculty and staff, crisis management plans, telehealth counseling, substance abuse programs, postvention support after suicide, collaboration with mental health providers, and support for diverse populations.

“The best schools are the ones that promote communication and that invite families to be involved early on because parents and families can be and need to be educated about what to do to prevent adverse outcomes of young people who are really at risk,” Dr. Rostain said. “It takes a village to raise a child, and it takes the same village to bring someone from adolescence to young adulthood.”

Family-based intervention has also shown promise, he said, but clinicians should watch for signs that a family is not willing to undergo therapy, is scapegoating a college student, or there are signs of boundary violations, violence, or sexual abuse in the family – or attempts to undermine treatment.

Specific to COVID-19, campus mental health services should focus on routine, self-care, physical activity, and connections with other people while also space for grieving lost experiences, facing uncertainty, developing resilience, and finding meaning. In the family, challenges around COVID-19 can include issues of physical distancing and quarantine, anxiety about becoming infected with the virus, economic insecurity, managing conflicts, setting and enforcing boundaries in addition to providing mutual support, and finding new meaning during the pandemic.

“I think these are the challenges, but we think this whole process of people living together and handling life in a way they’ve never expected to may hold some silver linings,” Dr. Rostain said. “It may be a way of addressing many issues that were never addressed before the young person went off to college.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Rostain reported receiving royalties from Routledge/Taylor Francis Group and St. Martin’s Press, scientific advisory board honoraria from Arbor and Shire/Takeda, consulting fees from the National Football League and Tris Pharmaceuticals, and has presented CME sessions for American Psychiatric Publishing, Global Medical Education, Shire/Takeda, and the U.S. Psychiatric Congress.

Socioeconomic, technological, cultural, and historical conditions are contributing to a mental health crisis among college students in the United States, according to Anthony L. Rostain, MD, MA, in a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

A recent National College Health Assessment published in fall of 2018 by the American College Health Association found that one in four college students had some kind of diagnosable mental illness, and 44% had symptoms of depression within the past year.

The assessment also found that college students felt overwhelmed (86%), felt sad (68%), felt very lonely (63%), had overwhelming anxiety (62%), experienced feelings of hopelessness (53%), or were depressed to the point where functioning was difficult (41%), all of which was higher than in previous years. Students also were more likely than in previous years to engage in interpersonal violence (17%), seriously consider suicide (11%), intentionally hurt themselves (7.4%), and attempt suicide (1.9%). According to the organization Active Minds, suicide is a leading cause of death in college students.

This shift in mental health for individuals in Generation Z, those born between the mid-1990s and early 2010s, can be attributed to historical events since the turn of the century, Dr. Rostain said at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education. The Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the financial crisis of 2007-2008, school shootings, globalization leading to economic uncertainty, the 24-hour news cycle and continuous media exposure, and the influence of the Internet have all influenced Gen Z’s identity.

“Growing up immersed in the Internet certainly has its advantages, but also maybe created some vulnerabilities in our young people,” he said.

Concerns about climate change, the burden of higher education and student debt, and the COVID-19 pandemic also have contributed to anxiety in this group. In a spring survey of students published by Active Minds about COVID-19 and its impact on mental health, 91% of students reported having stress or anxiety, 81% were disappointed or sad, 80% said they felt lonely or isolated, 56% had relocated as a result of the pandemic, and 48% reported financial setbacks tied to COVID-19.

“Anxiety seems to have become a feature of modern life,” said Dr. Rostain, who is director of education at the department of psychiatry and professor of psychiatry at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“Our culture, which often has a prominent emotional tone of fear, tends to promote cognitive distortions in which everyone is perceiving danger at every turn.” in this group, he noted. While people should be washing their hands and staying safe through social distancing during the pandemic, “we don’t want people to stop functioning, planning the future, and really in college students’ case, studying and getting ready for their careers,” he said. Parents can hinder those goals through intensively parenting or “overparenting” their children, which can result in destructive perfectionism, anxiety and depression, abject fear of failure and risk avoidance, and a focus on the external aspects of life rather than internal feelings.

Heavier alcohol use and amphetamine use also is on the rise in college students, Dr. Rostain said. Increased stimulant use in young adults is attributed to greater access to prescription drugs prior to college, greater prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), peer pressure, and influence from marketing and media messaging, he said. Another important change is the rise of smartphones and the Internet, which might drive the need to be constantly connected and compete for attention.

“This is the first generation who had constant access to the Internet. Smartphones in particular are everywhere, and we think this is another important factor in considering what might be happening to young people,” Dr. Rostain said.

Developing problem-solving and conflict resolution skills, developing coping mechanisms, being able to regulate emotions, finding optimism toward the future, having access to mental health services, and having cultural or religious beliefs with a negative view of suicide are all protective factors that promote resiliency in young people, Dr. Rostain said. Other protective factors include the development of socio-emotional readiness skills, such as conscientiousness, self-management, interpersonal skills, self-control, task persistence, risk management, self-acceptance, and having an open mindset or seeking help when needed. However, he noted, family is one area that can be both a help or a risk to mental health.

“Family attachments and supportive relationships in the family are really critical in predicting good outcomes. By the same token, families that are conflicted, where there’s a lot of stress or there’s a lot of turmoil and/or where resources are not available, that may be a risk factor to coping in young adulthood,” he said.

Individual resilience can be developed through learning from mistakes and overcoming mindset barriers, such as feelings of not belonging, concerns about disappointing one’s parents, worries about not making it, or fears of being different.

On campus, best practices and emerging trends include wellness and resiliency programs, reducing stigma, engagement from students, training of faculty and staff, crisis management plans, telehealth counseling, substance abuse programs, postvention support after suicide, collaboration with mental health providers, and support for diverse populations.

“The best schools are the ones that promote communication and that invite families to be involved early on because parents and families can be and need to be educated about what to do to prevent adverse outcomes of young people who are really at risk,” Dr. Rostain said. “It takes a village to raise a child, and it takes the same village to bring someone from adolescence to young adulthood.”

Family-based intervention has also shown promise, he said, but clinicians should watch for signs that a family is not willing to undergo therapy, is scapegoating a college student, or there are signs of boundary violations, violence, or sexual abuse in the family – or attempts to undermine treatment.

Specific to COVID-19, campus mental health services should focus on routine, self-care, physical activity, and connections with other people while also space for grieving lost experiences, facing uncertainty, developing resilience, and finding meaning. In the family, challenges around COVID-19 can include issues of physical distancing and quarantine, anxiety about becoming infected with the virus, economic insecurity, managing conflicts, setting and enforcing boundaries in addition to providing mutual support, and finding new meaning during the pandemic.

“I think these are the challenges, but we think this whole process of people living together and handling life in a way they’ve never expected to may hold some silver linings,” Dr. Rostain said. “It may be a way of addressing many issues that were never addressed before the young person went off to college.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Rostain reported receiving royalties from Routledge/Taylor Francis Group and St. Martin’s Press, scientific advisory board honoraria from Arbor and Shire/Takeda, consulting fees from the National Football League and Tris Pharmaceuticals, and has presented CME sessions for American Psychiatric Publishing, Global Medical Education, Shire/Takeda, and the U.S. Psychiatric Congress.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CP/AACP 2020 PSYCHIATRY UPDATE

Some telepsychiatry ‘here to stay’ post COVID

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed life in numerous ways, including use of telehealth services for patients in all specialties. But telepsychiatry is an area not likely to go away even after the pandemic is over, according to Sanjay Gupta, MD.

The use of telepsychiatry has escalated significantly,” said Dr. Gupta, of the DENT Neurologic Institute, in Amherst, N.Y., in a bonus virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

About 90% of clinicians are performing telepsychiatry, Dr. Gupta noted, through methods such as phone consults, email, and video chat. As patients with psychiatric issues grapple with issues related to COVID-19 involving lockdowns, restrictions on travel, and consumption of news, they are presenting with addiction, depression, paranoia, mood lability, and other problems.

One issue immediately facing clinicians is whether to keep patients on long-acting injectables as a way to maintain psychological stability in patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and alcoholism – something Dr. Gupta and session moderator Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, advocated. “We should never stop the long-acting injectable to switch them to oral medication. Those patients are very likely to relapse,” Dr. Nasrallah said.

During the pandemic, clinicians need to find “safe and novel ways of providing the injection,” and several methods have been pioneered. For example, if a patient with schizophrenia is on lockdown, a nurse can visit monthly or bimonthly to administer an injection, check on the patient’s mental status, and assess whether that patient needs an adjustment to their medication. Other clinics are offering “drive-by” injections to patients who arrive by car, and a nurse wearing a mask and a face shield administers the injection from the car window. Monthly naltrexone also can be administered using one of these methods, and telepsychiatry can be used to monitor patients, Dr. Gupta noted at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“In my clinic, what happens is the injection room is set up just next to the door, so they don’t have to walk deep into the clinic,” Dr. Gupta said. “They walk in, go to the left, [and] there’s the injection room. They sit, get an injection, they’re out. It’s kept smooth.”

Choosing the right telehealth option

Clinicians should be aware of important regulatory changes that occurred that made widespread telehealth more appealing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Payment parity with in-office visits makes telehealth a viable consideration, while some states have begun offering telehealth licenses to practice across state lines. There is wide variation with regard to which states provide licensure and prescribing privileges for out-of-state clinicians without seeing those patients in person. “The most important thing: The psychiatry service is provided in the state where the patient is located,” Dr. Gupta said. Clinicians should check with that state’s board to figure out specific requirements. “Preferably if you get it in writing, it’s good for you,” he said.

Deciding who the clinician is seeing – consulting with patients or other physicians/clinicians – and what type of visits a clinician will conduct is an important step in transitioning to telepsychiatry. Visits from evaluation through ongoing care are possible through telepsychiatry, or a clinician can opt to see just second opinion visits, Dr. Gupta said. It is also important to consider the technical ability of the patient to do video conferencing.

As HIPAA requirements for privacy have relaxed, clinicians now have an array of teleconferencing options to choose from; platforms such as FaceTime, Doximity, Vidyo, Doxy.me, Zoom, and video chat through EMR are popular options. However, when regular HIPAA requirements are reinstated after the pandemic, clinicians will need to find a compliant platform and sign a business associate agreement to stay within the law.

“Right now, my preferred use is FaceTime,” Dr. Gupta said. “Quick, simple, easy to use. A lot of people have an iPhone, and they know how to do it. I usually have the patient call me and I don’t use my personal iPhone; my clinic has an iPhone.”

How a clinician looks during a telepsychiatry visit is also important. Lighting, position of the camera, and clothing should all be considered. Keep the camera at eye level, test the lighting in the room where the call will take place, and use artificial lighting sources behind a computer, Dr. Gupta said. Other tips for telepsychiatry visits include silencing devices and microphones before a session begins, wearing solid-colored clothes, and having an identification badge visible to the patient. Sessions should be free of background distractions, such as a dog barking or a child interrupting, with the goal of creating an environment where the patient feels free to answer questions.

Contingency planning is a must for video visits, Dr. Gupta said. “I think the simplest thing is to see the patient. But all the stuff that’s the wraparound is really hard, because issues can arise suddenly, and we need to plan.” If a patient has a medical issue or becomes actively suicidal during a session, it is important to know contact information for the local police and crisis services. Clinicians also must plan for technology failure and provide alternative options for continuing the sessions, such as by phone.

Selecting patients for telepsychiatry

Not all patients will make the transition to telepsychiatry. “You can’t do telepsychiatry with everyone. It is a risk, so pick and choose,” Dr. Gupta said.

“Safety is a big consideration for conducting a telepsychiatry visit, especially when other health care providers are present. For example, when performing telehealth visits in a clinic, nursing home, or correctional facility, “I feel a lot more comfortable if there’s another health care clinician there,” Dr. Gupta said.

Clinicians may want to avoid a telepsychiatry visit for a patient in their own home for reasons of safety, reliability, and privacy. A longitudinal history with collateral information from friends or relatives can be helpful, but some subtle signs and body language may get missed over video, compared with an in-person visit. Sometimes you may not see if the patient is using substances. You have to really reconsider if [there] is violence and self-injurious behavior,” he said.

Discussing the pros and cons of telepsychiatry is important to obtaining patient consent. While consent requirements have relaxed under the COVID-19 pandemic, consent should ideally be obtained in writing, but can also be obtained verbally during a crisis. A plan should be developed for what will happen in the case of technology failure. “The patient should also know you’re maintaining privacy, you’re maintaining confidentiality, but there is a risk of hacking,” Dr. Gupta said. “Those things can happen, [and] there are no guarantees.”

If a patient is uncomfortable after beginning telepsychiatry, moving to in-person visits is also an option. “Many times, I do that if I’m not getting a good handle on things,” Dr. Gupta said. Situations where patients insist on in-patient visits over telepsychiatry are rare in his experience, Dr. Gupta noted, and are usually the result of the patient being unfamiliar with the technology. In cases where a patient cannot be talked through a technology barrier, visits can be done in the clinic while taking proper precautions.

“If it is a first-time visit, then I do it in the clinic,” Dr. Gupta said. “They come in, they have a face mask, and we use our group therapy room. The patients sit in a social-distanced fashion. But then, you document why you did this in-person visit like that.”

Documentation during COVID-19 also includes identifying the patient at the first visit, the nature of the visit (teleconference or other), parties present, referencing the pandemic, writing the location of the patient and the clinician, noting the patient’s satisfaction, evaluating the patient’s mental status, and recording what technology was used and any technical issues that were encountered.

Some populations of patients are better suited to telepsychiatry than others. It is more convenient for chronically psychiatrically ill patients in group homes and their staff to communicate through telepsychiatry, Dr. Gupta said. Consultation liaison in hospitals and emergency departments through telepsychiatry can limit the spread of infection, while increased access and convenience occurs as telepsychiatry is implemented in correctional facilities and nursing homes.

“What we are doing now, some of it is here to stay,” Dr. Gupta said.

In situations where a patient needs to switch providers, clinicians should continue to follow that patient until his first patient visit with that new provider. It is also important to set boundaries and apply some level of formality to the telepsychiatry visit, which means seeing the patient in a secure location where he can speak freely and privately.

“The best practices are [to] maintain faith [and] fidelity of the psychiatric assessment,” Dr. Gupta said. “Keep the trust and do your best to maintain patient privacy, because the privacy is not the same as it may be in a face-to-face session when you use televideo.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Gupta reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Nasrallah disclosed serving as a consultant for and on the speakers bureaus of several pharmaceutical companies, including Alkermes, Janssen, and Lundbeck. He also disclosed serving on the speakers bureau of Otsuka.

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed life in numerous ways, including use of telehealth services for patients in all specialties. But telepsychiatry is an area not likely to go away even after the pandemic is over, according to Sanjay Gupta, MD.

The use of telepsychiatry has escalated significantly,” said Dr. Gupta, of the DENT Neurologic Institute, in Amherst, N.Y., in a bonus virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

About 90% of clinicians are performing telepsychiatry, Dr. Gupta noted, through methods such as phone consults, email, and video chat. As patients with psychiatric issues grapple with issues related to COVID-19 involving lockdowns, restrictions on travel, and consumption of news, they are presenting with addiction, depression, paranoia, mood lability, and other problems.

One issue immediately facing clinicians is whether to keep patients on long-acting injectables as a way to maintain psychological stability in patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and alcoholism – something Dr. Gupta and session moderator Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, advocated. “We should never stop the long-acting injectable to switch them to oral medication. Those patients are very likely to relapse,” Dr. Nasrallah said.

During the pandemic, clinicians need to find “safe and novel ways of providing the injection,” and several methods have been pioneered. For example, if a patient with schizophrenia is on lockdown, a nurse can visit monthly or bimonthly to administer an injection, check on the patient’s mental status, and assess whether that patient needs an adjustment to their medication. Other clinics are offering “drive-by” injections to patients who arrive by car, and a nurse wearing a mask and a face shield administers the injection from the car window. Monthly naltrexone also can be administered using one of these methods, and telepsychiatry can be used to monitor patients, Dr. Gupta noted at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“In my clinic, what happens is the injection room is set up just next to the door, so they don’t have to walk deep into the clinic,” Dr. Gupta said. “They walk in, go to the left, [and] there’s the injection room. They sit, get an injection, they’re out. It’s kept smooth.”

Choosing the right telehealth option

Clinicians should be aware of important regulatory changes that occurred that made widespread telehealth more appealing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Payment parity with in-office visits makes telehealth a viable consideration, while some states have begun offering telehealth licenses to practice across state lines. There is wide variation with regard to which states provide licensure and prescribing privileges for out-of-state clinicians without seeing those patients in person. “The most important thing: The psychiatry service is provided in the state where the patient is located,” Dr. Gupta said. Clinicians should check with that state’s board to figure out specific requirements. “Preferably if you get it in writing, it’s good for you,” he said.

Deciding who the clinician is seeing – consulting with patients or other physicians/clinicians – and what type of visits a clinician will conduct is an important step in transitioning to telepsychiatry. Visits from evaluation through ongoing care are possible through telepsychiatry, or a clinician can opt to see just second opinion visits, Dr. Gupta said. It is also important to consider the technical ability of the patient to do video conferencing.

As HIPAA requirements for privacy have relaxed, clinicians now have an array of teleconferencing options to choose from; platforms such as FaceTime, Doximity, Vidyo, Doxy.me, Zoom, and video chat through EMR are popular options. However, when regular HIPAA requirements are reinstated after the pandemic, clinicians will need to find a compliant platform and sign a business associate agreement to stay within the law.

“Right now, my preferred use is FaceTime,” Dr. Gupta said. “Quick, simple, easy to use. A lot of people have an iPhone, and they know how to do it. I usually have the patient call me and I don’t use my personal iPhone; my clinic has an iPhone.”

How a clinician looks during a telepsychiatry visit is also important. Lighting, position of the camera, and clothing should all be considered. Keep the camera at eye level, test the lighting in the room where the call will take place, and use artificial lighting sources behind a computer, Dr. Gupta said. Other tips for telepsychiatry visits include silencing devices and microphones before a session begins, wearing solid-colored clothes, and having an identification badge visible to the patient. Sessions should be free of background distractions, such as a dog barking or a child interrupting, with the goal of creating an environment where the patient feels free to answer questions.

Contingency planning is a must for video visits, Dr. Gupta said. “I think the simplest thing is to see the patient. But all the stuff that’s the wraparound is really hard, because issues can arise suddenly, and we need to plan.” If a patient has a medical issue or becomes actively suicidal during a session, it is important to know contact information for the local police and crisis services. Clinicians also must plan for technology failure and provide alternative options for continuing the sessions, such as by phone.

Selecting patients for telepsychiatry

Not all patients will make the transition to telepsychiatry. “You can’t do telepsychiatry with everyone. It is a risk, so pick and choose,” Dr. Gupta said.

“Safety is a big consideration for conducting a telepsychiatry visit, especially when other health care providers are present. For example, when performing telehealth visits in a clinic, nursing home, or correctional facility, “I feel a lot more comfortable if there’s another health care clinician there,” Dr. Gupta said.

Clinicians may want to avoid a telepsychiatry visit for a patient in their own home for reasons of safety, reliability, and privacy. A longitudinal history with collateral information from friends or relatives can be helpful, but some subtle signs and body language may get missed over video, compared with an in-person visit. Sometimes you may not see if the patient is using substances. You have to really reconsider if [there] is violence and self-injurious behavior,” he said.

Discussing the pros and cons of telepsychiatry is important to obtaining patient consent. While consent requirements have relaxed under the COVID-19 pandemic, consent should ideally be obtained in writing, but can also be obtained verbally during a crisis. A plan should be developed for what will happen in the case of technology failure. “The patient should also know you’re maintaining privacy, you’re maintaining confidentiality, but there is a risk of hacking,” Dr. Gupta said. “Those things can happen, [and] there are no guarantees.”

If a patient is uncomfortable after beginning telepsychiatry, moving to in-person visits is also an option. “Many times, I do that if I’m not getting a good handle on things,” Dr. Gupta said. Situations where patients insist on in-patient visits over telepsychiatry are rare in his experience, Dr. Gupta noted, and are usually the result of the patient being unfamiliar with the technology. In cases where a patient cannot be talked through a technology barrier, visits can be done in the clinic while taking proper precautions.

“If it is a first-time visit, then I do it in the clinic,” Dr. Gupta said. “They come in, they have a face mask, and we use our group therapy room. The patients sit in a social-distanced fashion. But then, you document why you did this in-person visit like that.”

Documentation during COVID-19 also includes identifying the patient at the first visit, the nature of the visit (teleconference or other), parties present, referencing the pandemic, writing the location of the patient and the clinician, noting the patient’s satisfaction, evaluating the patient’s mental status, and recording what technology was used and any technical issues that were encountered.

Some populations of patients are better suited to telepsychiatry than others. It is more convenient for chronically psychiatrically ill patients in group homes and their staff to communicate through telepsychiatry, Dr. Gupta said. Consultation liaison in hospitals and emergency departments through telepsychiatry can limit the spread of infection, while increased access and convenience occurs as telepsychiatry is implemented in correctional facilities and nursing homes.

“What we are doing now, some of it is here to stay,” Dr. Gupta said.

In situations where a patient needs to switch providers, clinicians should continue to follow that patient until his first patient visit with that new provider. It is also important to set boundaries and apply some level of formality to the telepsychiatry visit, which means seeing the patient in a secure location where he can speak freely and privately.

“The best practices are [to] maintain faith [and] fidelity of the psychiatric assessment,” Dr. Gupta said. “Keep the trust and do your best to maintain patient privacy, because the privacy is not the same as it may be in a face-to-face session when you use televideo.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Gupta reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Nasrallah disclosed serving as a consultant for and on the speakers bureaus of several pharmaceutical companies, including Alkermes, Janssen, and Lundbeck. He also disclosed serving on the speakers bureau of Otsuka.

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed life in numerous ways, including use of telehealth services for patients in all specialties. But telepsychiatry is an area not likely to go away even after the pandemic is over, according to Sanjay Gupta, MD.

The use of telepsychiatry has escalated significantly,” said Dr. Gupta, of the DENT Neurologic Institute, in Amherst, N.Y., in a bonus virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

About 90% of clinicians are performing telepsychiatry, Dr. Gupta noted, through methods such as phone consults, email, and video chat. As patients with psychiatric issues grapple with issues related to COVID-19 involving lockdowns, restrictions on travel, and consumption of news, they are presenting with addiction, depression, paranoia, mood lability, and other problems.

One issue immediately facing clinicians is whether to keep patients on long-acting injectables as a way to maintain psychological stability in patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and alcoholism – something Dr. Gupta and session moderator Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, advocated. “We should never stop the long-acting injectable to switch them to oral medication. Those patients are very likely to relapse,” Dr. Nasrallah said.

During the pandemic, clinicians need to find “safe and novel ways of providing the injection,” and several methods have been pioneered. For example, if a patient with schizophrenia is on lockdown, a nurse can visit monthly or bimonthly to administer an injection, check on the patient’s mental status, and assess whether that patient needs an adjustment to their medication. Other clinics are offering “drive-by” injections to patients who arrive by car, and a nurse wearing a mask and a face shield administers the injection from the car window. Monthly naltrexone also can be administered using one of these methods, and telepsychiatry can be used to monitor patients, Dr. Gupta noted at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“In my clinic, what happens is the injection room is set up just next to the door, so they don’t have to walk deep into the clinic,” Dr. Gupta said. “They walk in, go to the left, [and] there’s the injection room. They sit, get an injection, they’re out. It’s kept smooth.”

Choosing the right telehealth option

Clinicians should be aware of important regulatory changes that occurred that made widespread telehealth more appealing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Payment parity with in-office visits makes telehealth a viable consideration, while some states have begun offering telehealth licenses to practice across state lines. There is wide variation with regard to which states provide licensure and prescribing privileges for out-of-state clinicians without seeing those patients in person. “The most important thing: The psychiatry service is provided in the state where the patient is located,” Dr. Gupta said. Clinicians should check with that state’s board to figure out specific requirements. “Preferably if you get it in writing, it’s good for you,” he said.

Deciding who the clinician is seeing – consulting with patients or other physicians/clinicians – and what type of visits a clinician will conduct is an important step in transitioning to telepsychiatry. Visits from evaluation through ongoing care are possible through telepsychiatry, or a clinician can opt to see just second opinion visits, Dr. Gupta said. It is also important to consider the technical ability of the patient to do video conferencing.

As HIPAA requirements for privacy have relaxed, clinicians now have an array of teleconferencing options to choose from; platforms such as FaceTime, Doximity, Vidyo, Doxy.me, Zoom, and video chat through EMR are popular options. However, when regular HIPAA requirements are reinstated after the pandemic, clinicians will need to find a compliant platform and sign a business associate agreement to stay within the law.

“Right now, my preferred use is FaceTime,” Dr. Gupta said. “Quick, simple, easy to use. A lot of people have an iPhone, and they know how to do it. I usually have the patient call me and I don’t use my personal iPhone; my clinic has an iPhone.”

How a clinician looks during a telepsychiatry visit is also important. Lighting, position of the camera, and clothing should all be considered. Keep the camera at eye level, test the lighting in the room where the call will take place, and use artificial lighting sources behind a computer, Dr. Gupta said. Other tips for telepsychiatry visits include silencing devices and microphones before a session begins, wearing solid-colored clothes, and having an identification badge visible to the patient. Sessions should be free of background distractions, such as a dog barking or a child interrupting, with the goal of creating an environment where the patient feels free to answer questions.

Contingency planning is a must for video visits, Dr. Gupta said. “I think the simplest thing is to see the patient. But all the stuff that’s the wraparound is really hard, because issues can arise suddenly, and we need to plan.” If a patient has a medical issue or becomes actively suicidal during a session, it is important to know contact information for the local police and crisis services. Clinicians also must plan for technology failure and provide alternative options for continuing the sessions, such as by phone.

Selecting patients for telepsychiatry

Not all patients will make the transition to telepsychiatry. “You can’t do telepsychiatry with everyone. It is a risk, so pick and choose,” Dr. Gupta said.

“Safety is a big consideration for conducting a telepsychiatry visit, especially when other health care providers are present. For example, when performing telehealth visits in a clinic, nursing home, or correctional facility, “I feel a lot more comfortable if there’s another health care clinician there,” Dr. Gupta said.

Clinicians may want to avoid a telepsychiatry visit for a patient in their own home for reasons of safety, reliability, and privacy. A longitudinal history with collateral information from friends or relatives can be helpful, but some subtle signs and body language may get missed over video, compared with an in-person visit. Sometimes you may not see if the patient is using substances. You have to really reconsider if [there] is violence and self-injurious behavior,” he said.

Discussing the pros and cons of telepsychiatry is important to obtaining patient consent. While consent requirements have relaxed under the COVID-19 pandemic, consent should ideally be obtained in writing, but can also be obtained verbally during a crisis. A plan should be developed for what will happen in the case of technology failure. “The patient should also know you’re maintaining privacy, you’re maintaining confidentiality, but there is a risk of hacking,” Dr. Gupta said. “Those things can happen, [and] there are no guarantees.”

If a patient is uncomfortable after beginning telepsychiatry, moving to in-person visits is also an option. “Many times, I do that if I’m not getting a good handle on things,” Dr. Gupta said. Situations where patients insist on in-patient visits over telepsychiatry are rare in his experience, Dr. Gupta noted, and are usually the result of the patient being unfamiliar with the technology. In cases where a patient cannot be talked through a technology barrier, visits can be done in the clinic while taking proper precautions.

“If it is a first-time visit, then I do it in the clinic,” Dr. Gupta said. “They come in, they have a face mask, and we use our group therapy room. The patients sit in a social-distanced fashion. But then, you document why you did this in-person visit like that.”

Documentation during COVID-19 also includes identifying the patient at the first visit, the nature of the visit (teleconference or other), parties present, referencing the pandemic, writing the location of the patient and the clinician, noting the patient’s satisfaction, evaluating the patient’s mental status, and recording what technology was used and any technical issues that were encountered.

Some populations of patients are better suited to telepsychiatry than others. It is more convenient for chronically psychiatrically ill patients in group homes and their staff to communicate through telepsychiatry, Dr. Gupta said. Consultation liaison in hospitals and emergency departments through telepsychiatry can limit the spread of infection, while increased access and convenience occurs as telepsychiatry is implemented in correctional facilities and nursing homes.

“What we are doing now, some of it is here to stay,” Dr. Gupta said.

In situations where a patient needs to switch providers, clinicians should continue to follow that patient until his first patient visit with that new provider. It is also important to set boundaries and apply some level of formality to the telepsychiatry visit, which means seeing the patient in a secure location where he can speak freely and privately.

“The best practices are [to] maintain faith [and] fidelity of the psychiatric assessment,” Dr. Gupta said. “Keep the trust and do your best to maintain patient privacy, because the privacy is not the same as it may be in a face-to-face session when you use televideo.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Gupta reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Nasrallah disclosed serving as a consultant for and on the speakers bureaus of several pharmaceutical companies, including Alkermes, Janssen, and Lundbeck. He also disclosed serving on the speakers bureau of Otsuka.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CP/AACP 2020 PSYCHIATRY UPDATE

Managing amidst COVID-19 (and everything else that ails us)

This year, medical media has been dominated by reporting on the devastating COVID-19 pandemic. Many studies and analyses have shown that staying at home, social distancing, quarantining of close contacts, and wearing face masks and face shields are effective ways of preventing spread.

Although initially there were no known effective treatments for severe COVID-19 infection (other than oxygen and ventilator support), we now know that dexamethasone,1 remdesivir,2 and convalescent plasma3 are effective in lessening the severity of illness and perhaps preventing death. That said, we will continue to struggle with COVID-19 for the foreseeable future.

But other medical illnesses actually predominate in terms of morbidity and mortality, even during this pandemic. For example, although there has been an average of roughly 5600 COVID-19-related deaths per week for the past 4 months,4 there are, on average, more than 54,000 deaths per week in the United States from other causes.5 This means that we must continue to tend to the other health care needs of our patients even as we deal with COVID-19.

In that light, JFP continues to publish practical, evidence-based clinical reviews designed to keep family physicians and other primary health care clinicians up to date on a variety of topics. For instance, in this issue of JFP, we have articles on:

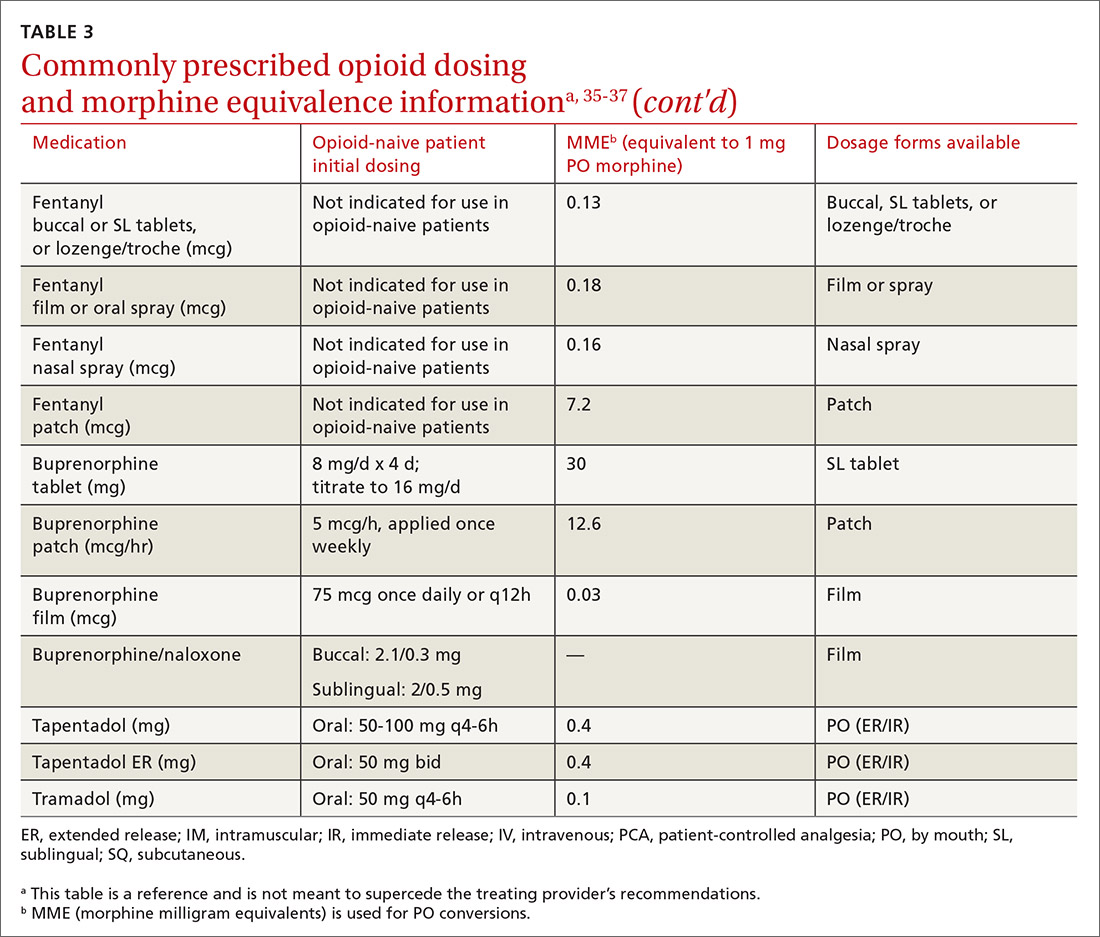

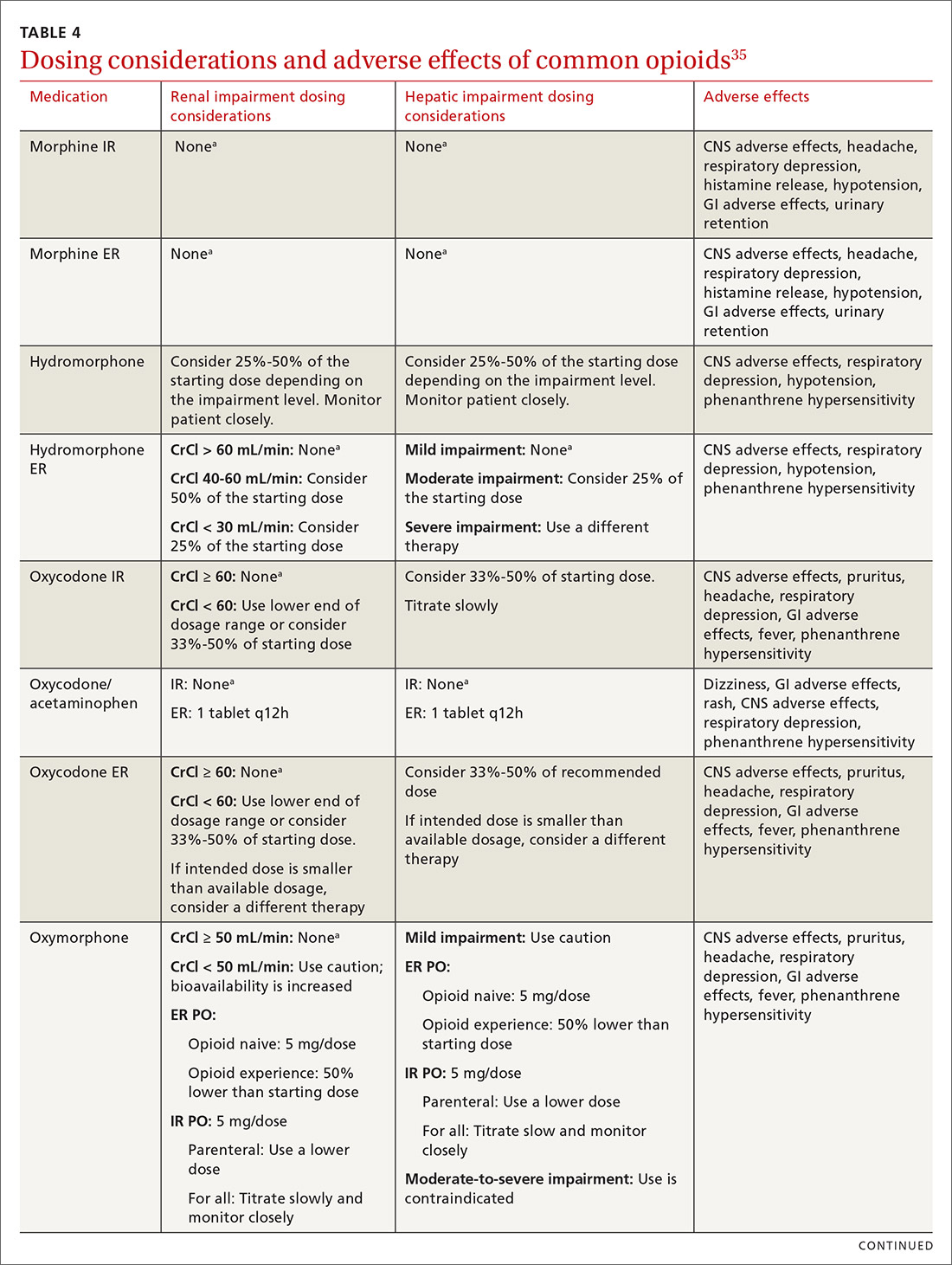

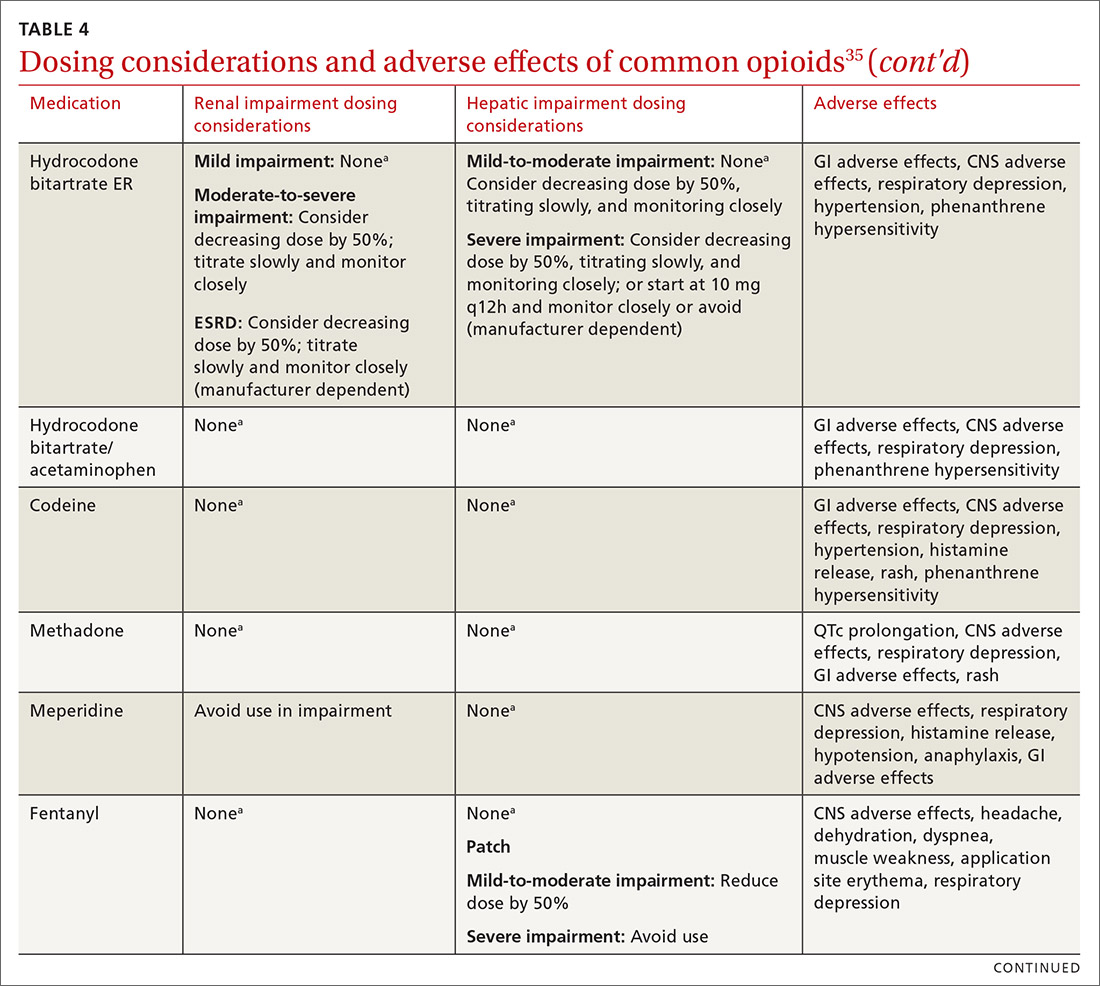

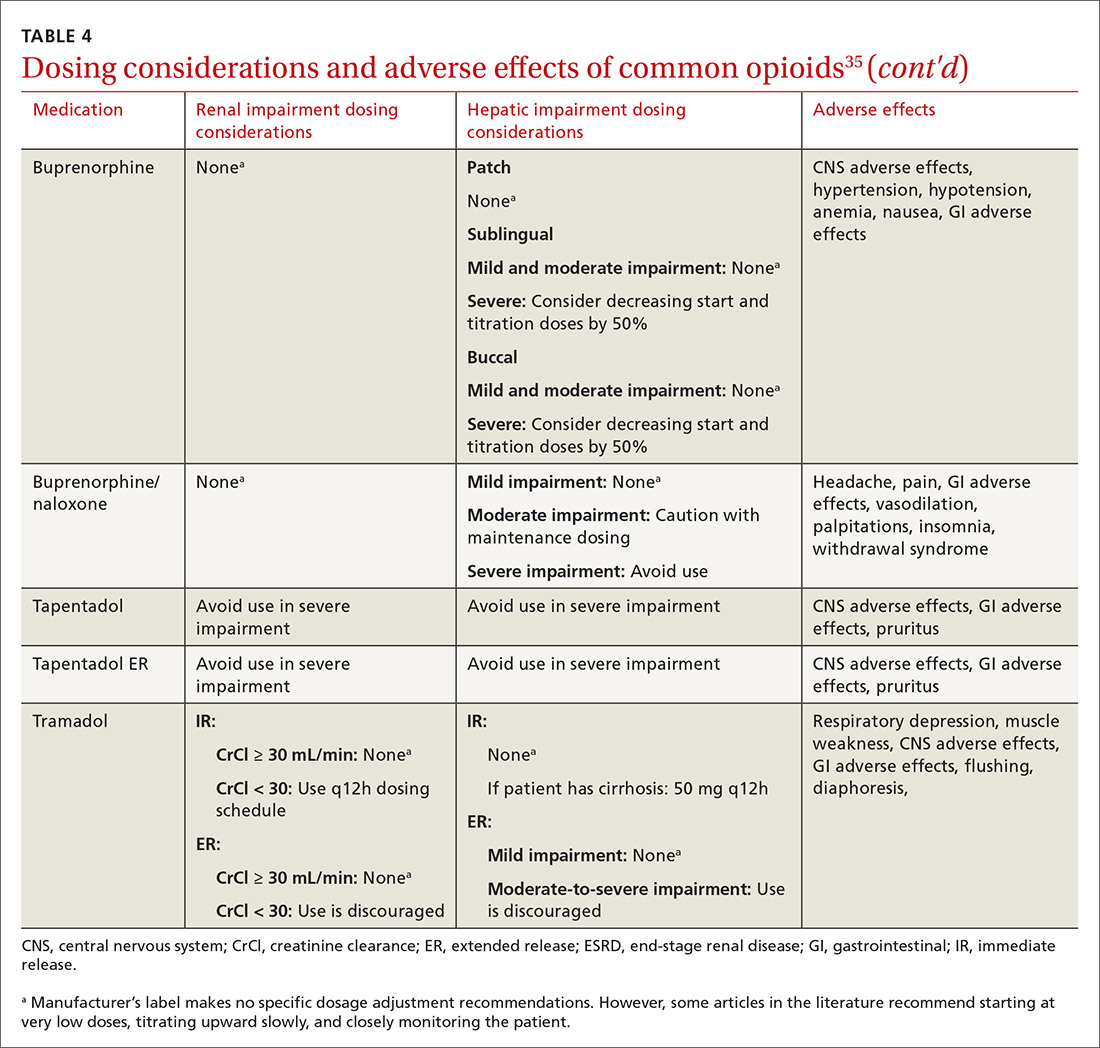

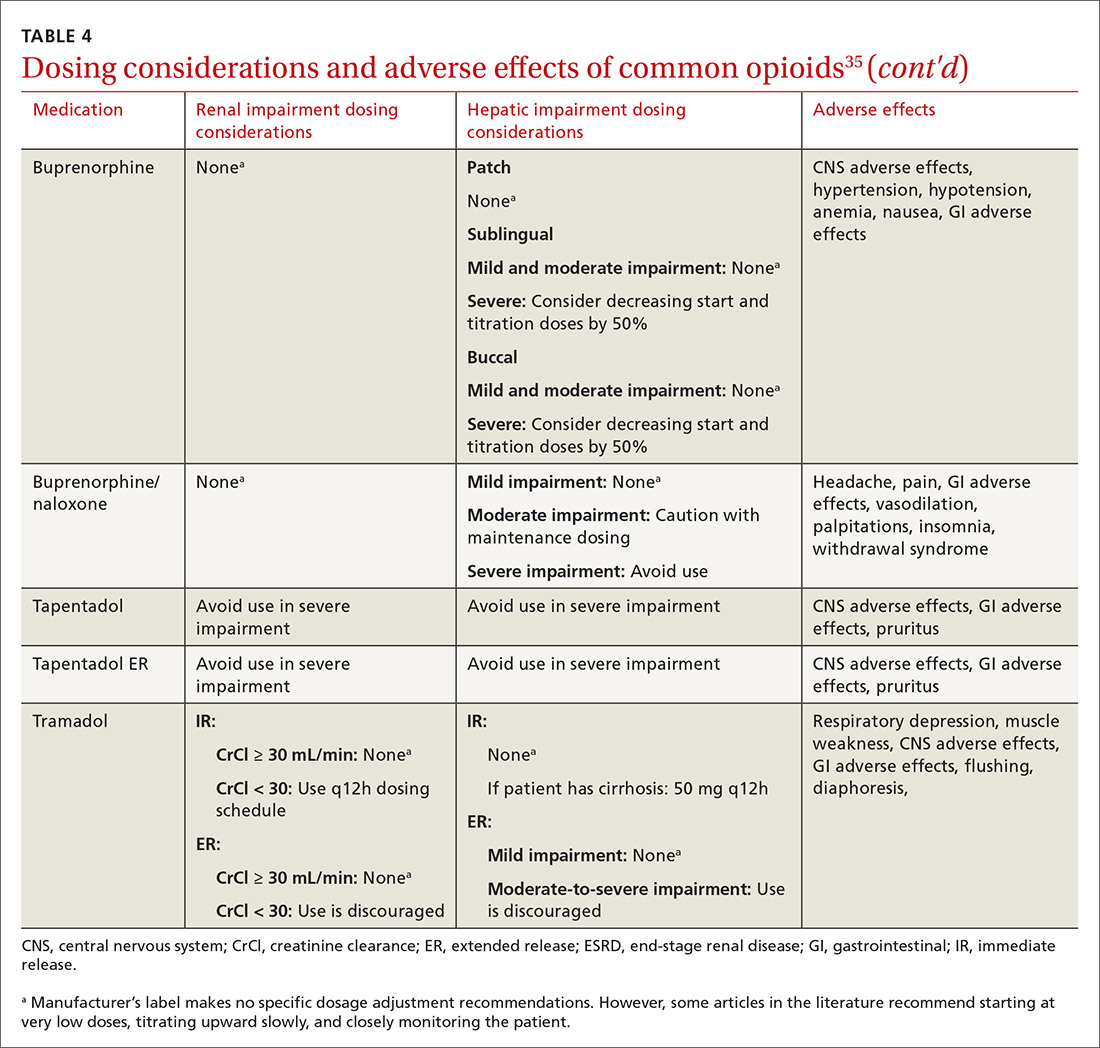

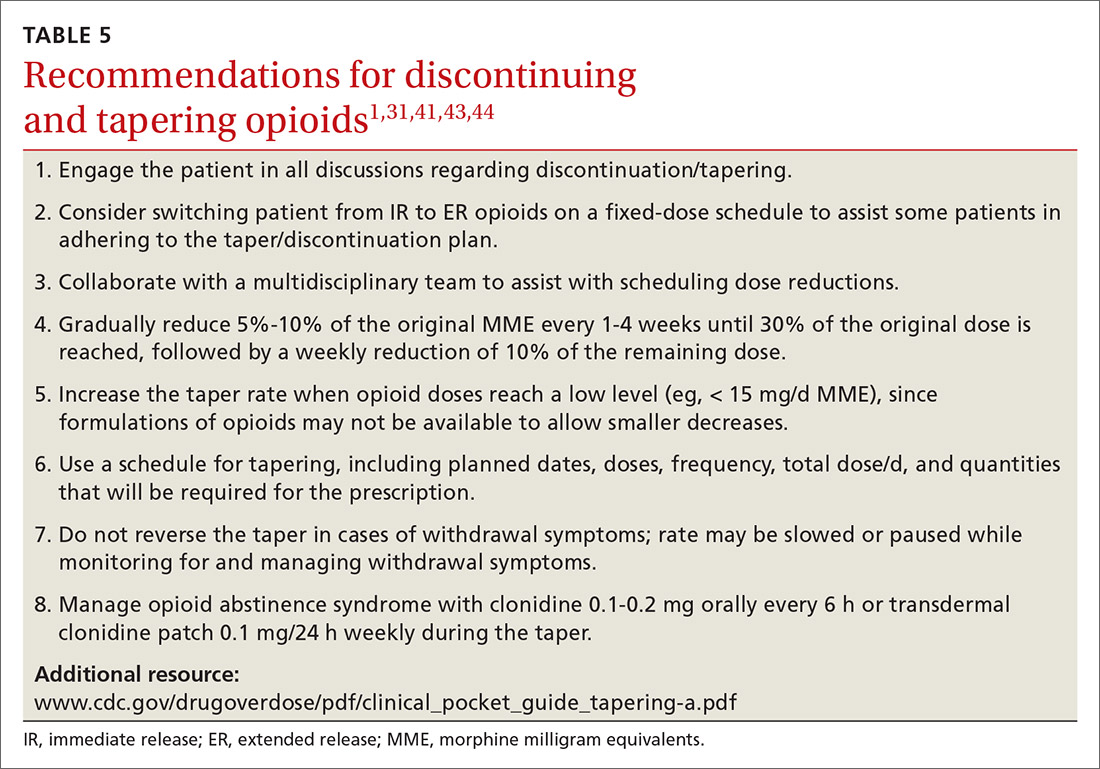

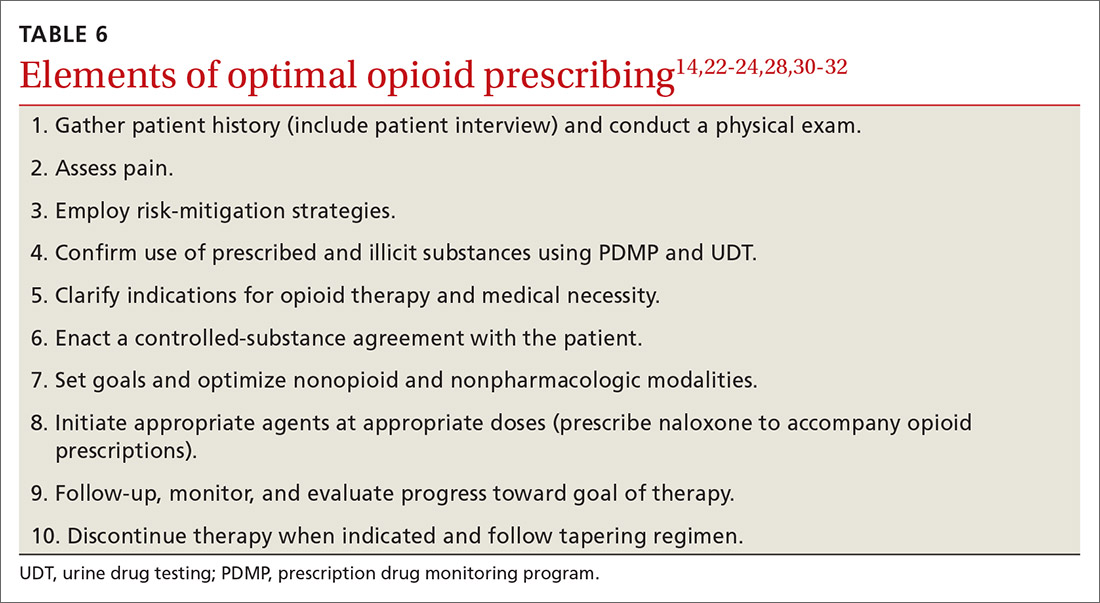

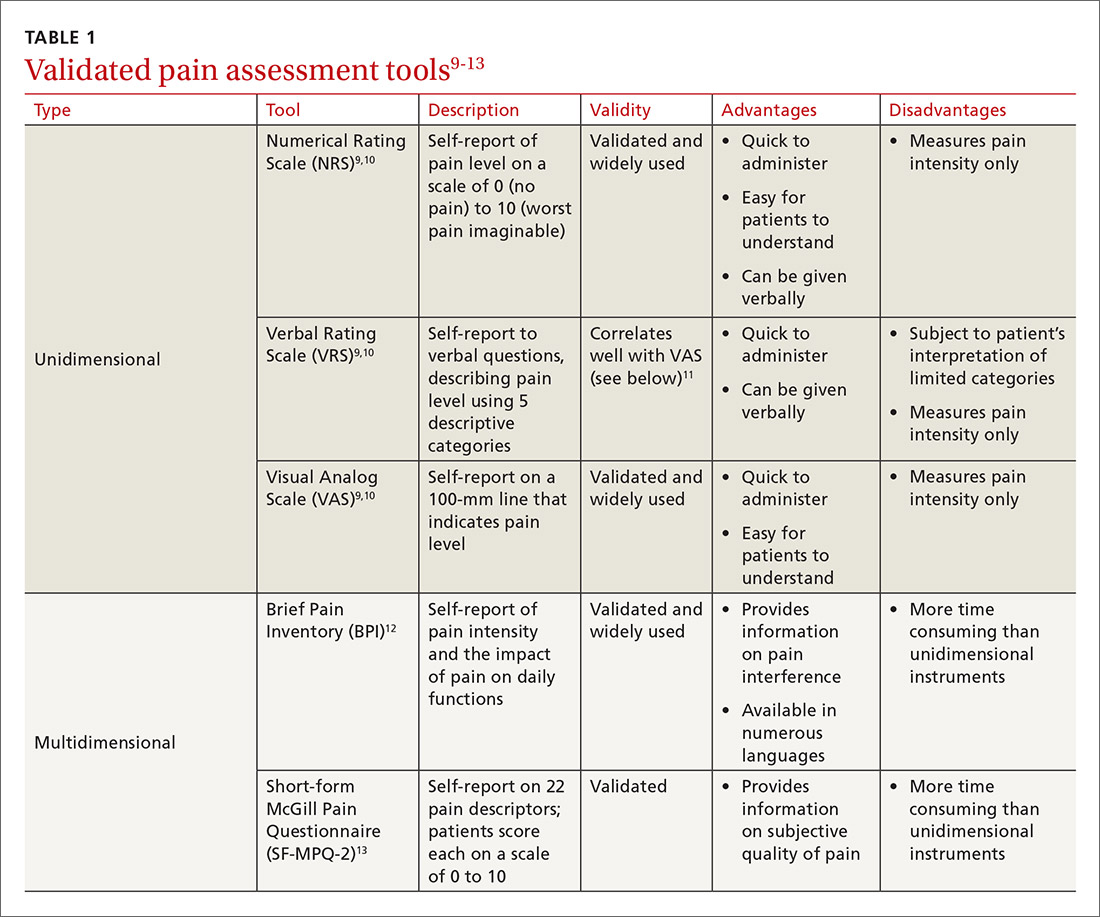

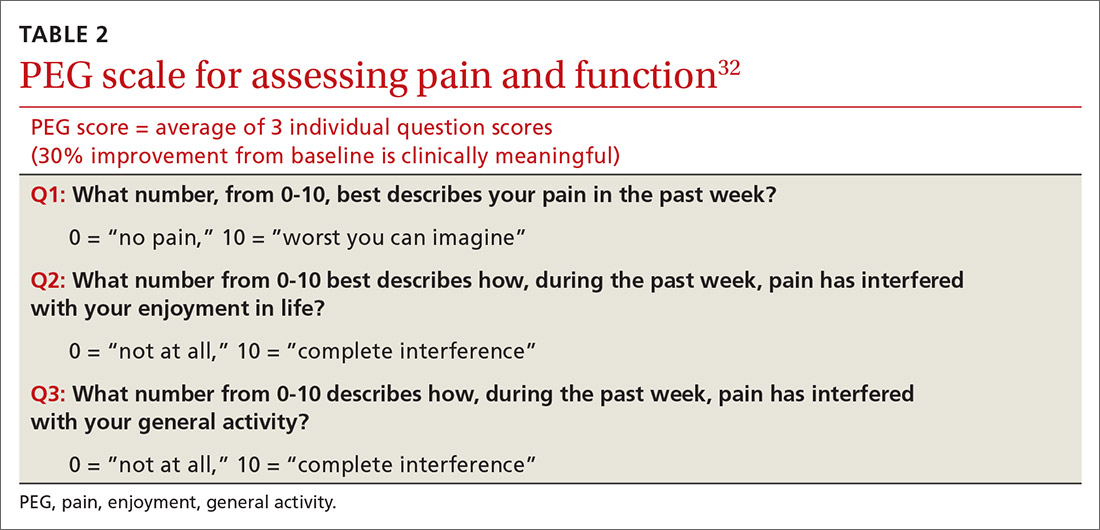

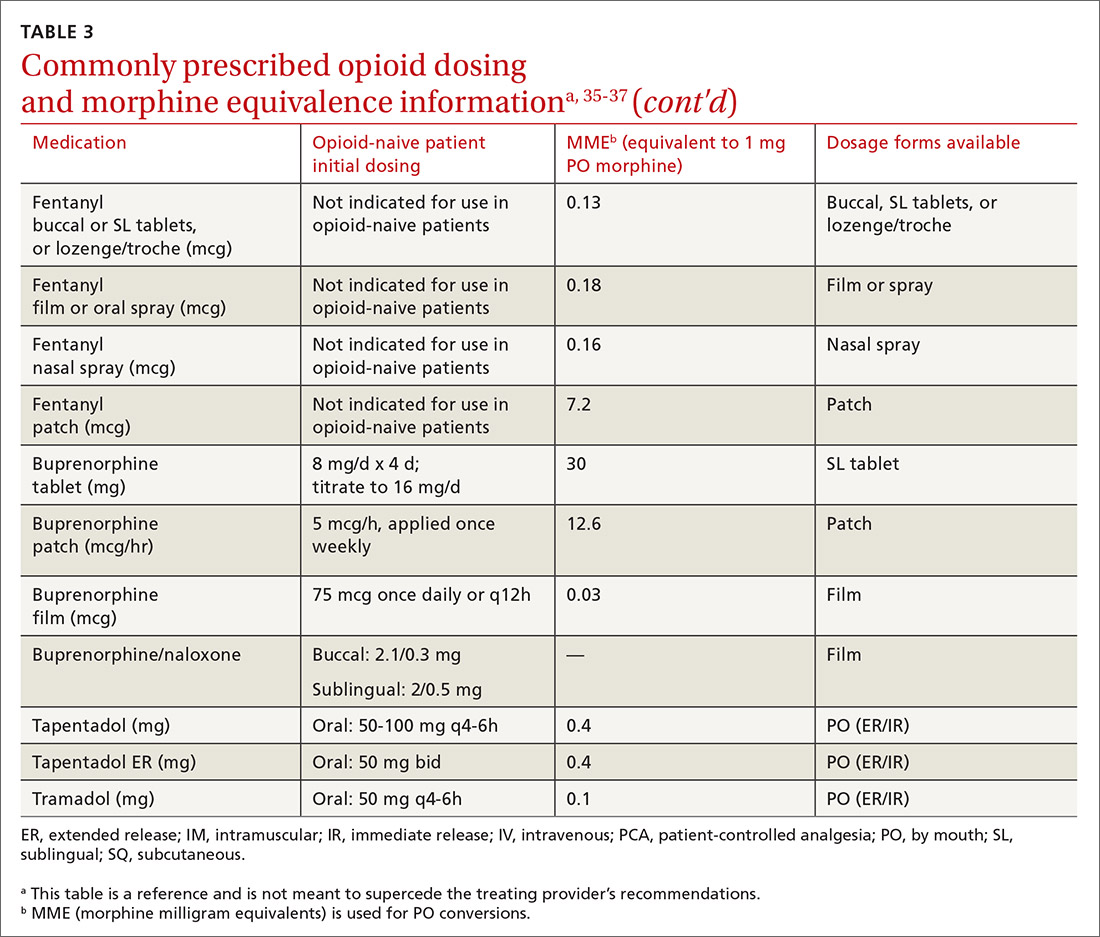

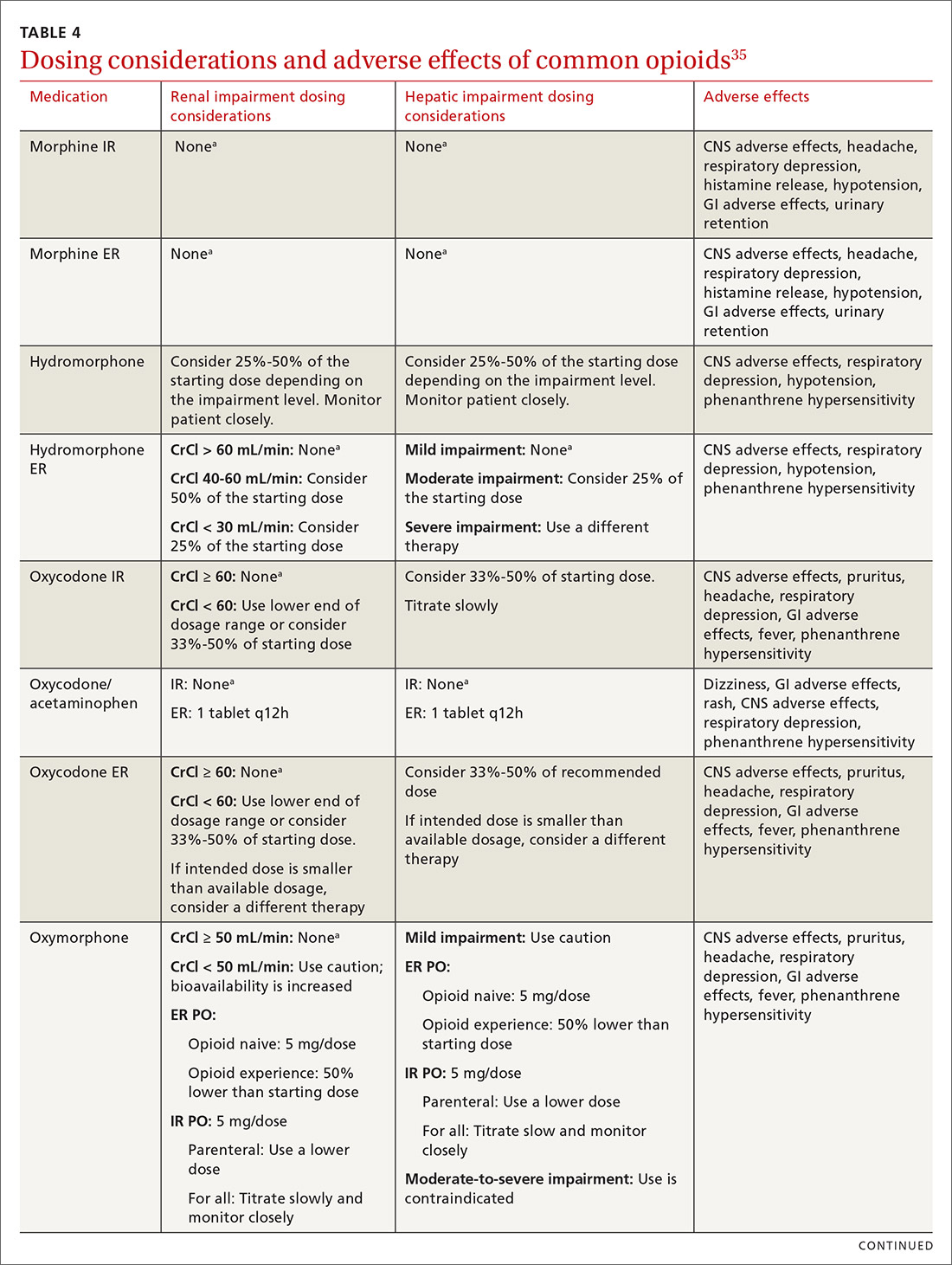

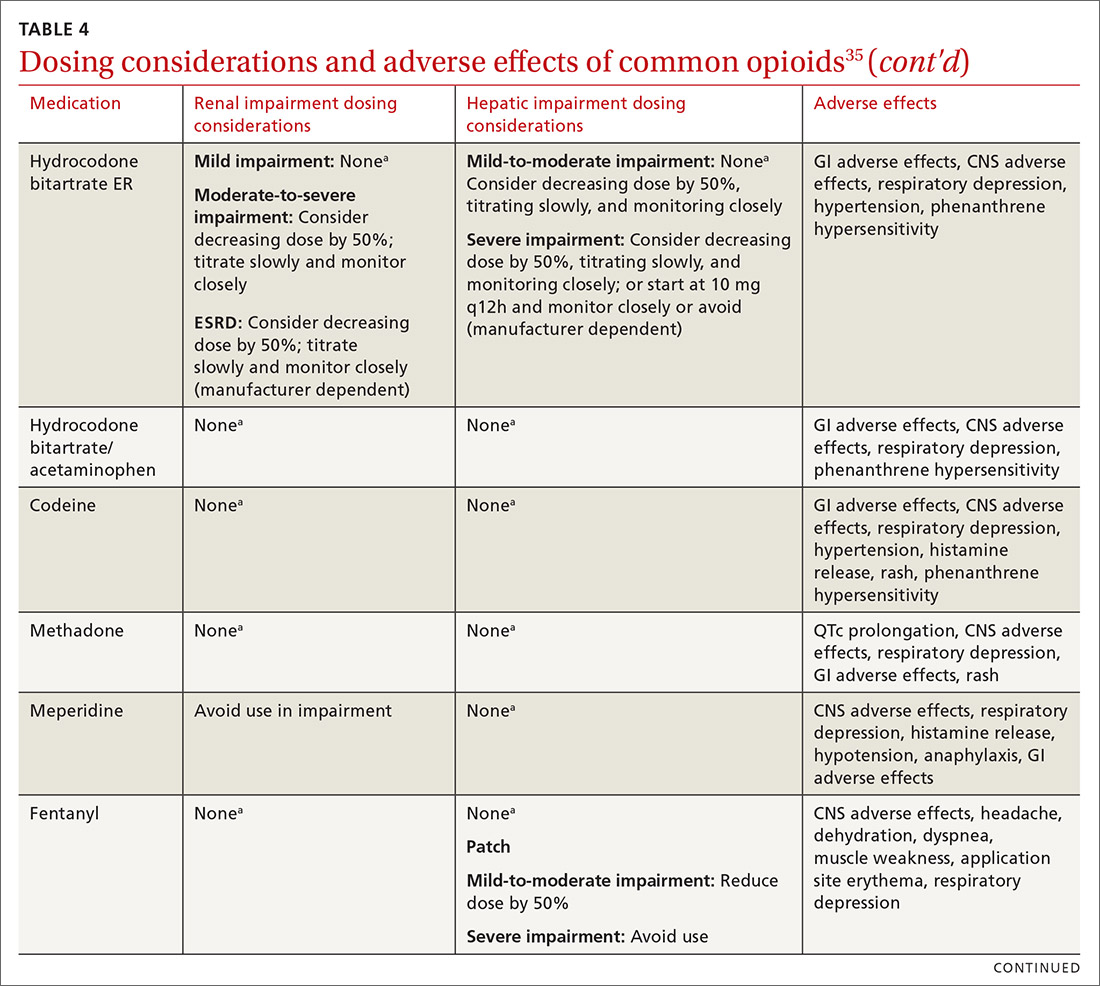

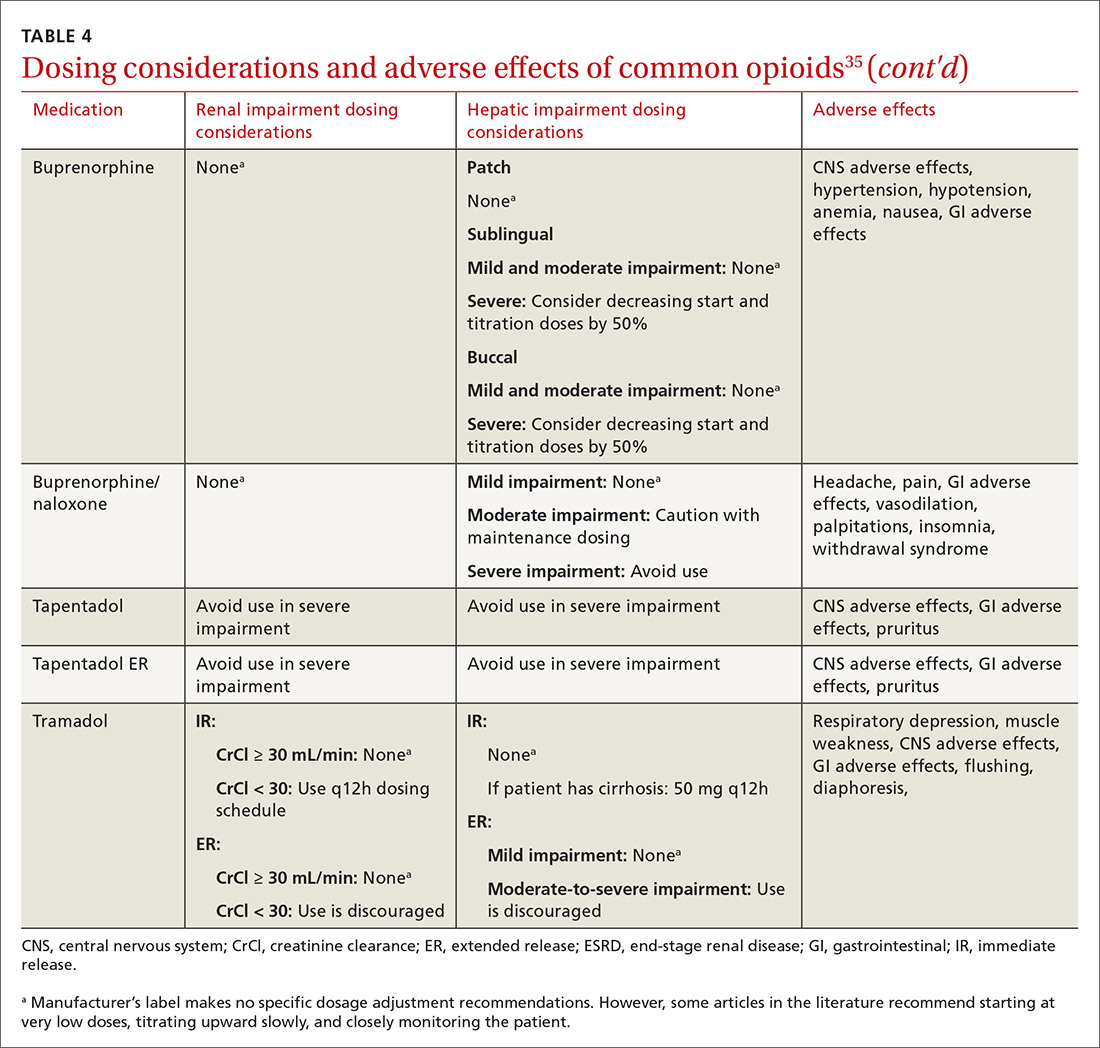

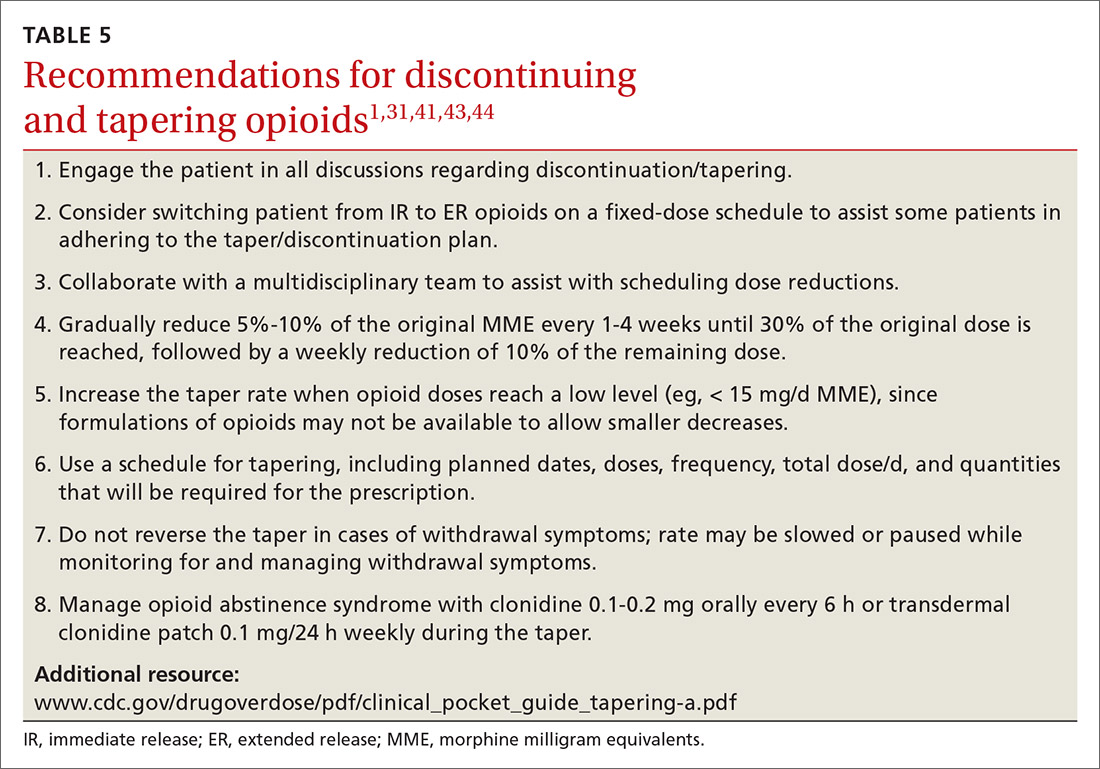

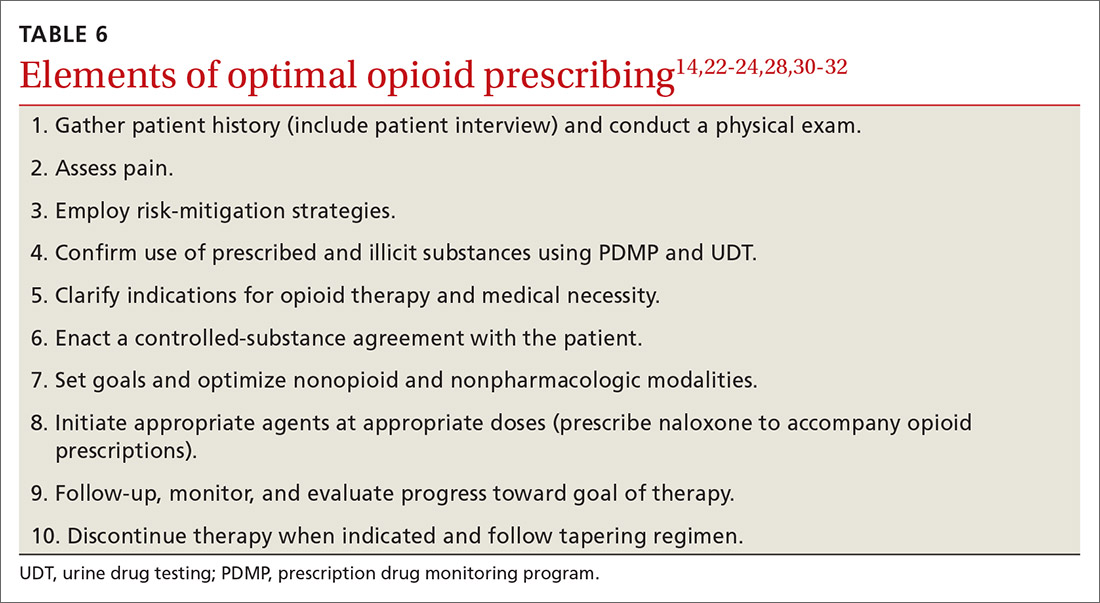

- Opioid prescribing. Although opioids have risks, they remain potent medications for relief from acute pain, as well as cancer-related pain and chronic pain not sufficiently treated with other medications. Mahvan et al provide expert advice on maximizing benefit and minimizing the risks of opioid prescribing.

- Secondary ischemic stroke prevention. For patients who have suffered a transient ischemic attack or minor stroke, a mainstay of prevention is antiplatelet therapy. Aspirin alone used to be the treatment of choice, but research has demonstrated the value of adding another antiplatelet agent. Helmer et al’s thorough review reminds us that the antiplatelet drug of choice, in addition to aspirin, is clopidogrel, which should be used only for the first 30 days after the event because of an increased bleeding risk.

- Combatting Clostridioides difficile infection. CDI has been a difficult condition to treat, especially in high-risk patients. Zukauckas et al provide a comprehensive review of diagnosis and management. Vancomycin is now the drug of choice, and fecal transplant is highly effective in preventing recurrent CDI.

This diverse range of timely, practical, evidence-based guidance—in addition to coverage of COVID-19 and other rapidly emerging medical news stories—can all be found on our Web site at www.mdedge.com/familymedicine. We remain committed to supplying you with all of the information you need to provide your patients with the very best care—no matter what brings them in to see you.

1. Low-cost dexamethasone reduces death by up to one third in hospitalized patients with severe respiratory complications of COVID-19. Recovery: Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy Web site. June 16, 2020. www.recoverytrial.net/news/low-cost-dexamethasone-reduces-death-by-up-to-one-third-in-hospitalised-patients-with-severe-respiratory-complications-of-covid-19. Accessed July 1, 2020.

2. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—preliminary report [published online ahead of print]. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764.

3. Li L, Zhang W, Hu Y, et. al. Effect of convalescent plasma therapy on time to clinical improvement in patients with severe and life-threatening COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial [published online ahead of print]. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.10044.

4. Stokes EK, Zambrano LD, Anderson KN, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 case surveillance—United States, January 22–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:759-765.