User login

Treatment for a tobacco-dependent adult

Applying American Thoracic Society’s new clinical practice guideline

Complications from tobacco use are the most common preventable cause of death, disability, and disease in the United States. Tobacco use causes 480,000 premature deaths every year. In pregnancy, tobacco use causes complications such as premature birth, intrauterine growth restriction, and placental abruption. In the perinatal period, it is associated with sudden infant death syndrome. While cigarette smoking is decreasing in adolescents, e-cigarette use in on the rise. Approximately 1,600 children aged 12-17 smoke their first cigarette every day and it is estimated that 5.6 million children and adolescents will die of a tobacco use–related death.1 For these reasons it is important to address tobacco use and cessation with patients whenever it is possible.

Case

A forty-five-year-old male who rarely comes to the office is here today for a physical exam at the urging of his partner. He has been smoking a pack a day since age 17. You have tried at past visits to discuss quitting, but he had been in the precontemplative stage and had been unwilling to consider any change. This visit, however, he is ready to try to quit. What can you offer him?

Core recommendations from ATS guidelines

This patient can be offered varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy rather than nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, e-cigarettes, or varenicline alone. His course of therapy should extend beyond 12 weeks instead of the standard 6- to 12-week therapy. Alternatively, he could be offered varenicline alone, rather than nicotine replacement.2

A change from previous guidelines

What makes this recommendation so interesting and new is the emphasis it places on varenicline. The United States Preventive Services Task Force released a recommendation statement in 2015 that stressed a combination of pharmacological and behavioral interventions. It discussed nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, and varenicline, but did not recommend any one over any of the others.3 The new recommendation from the American Thoracic Society favors varenicline over other pharmacologic interventions. It is based on an independent systematic review of the literature that showed higher rates of tobacco use abstinence at the 6-month follow-up with varenicline alone versus nicotine replacement therapy alone, bupropion alone, or e-cigarette use only.

A review of 14 randomized controlled trials showed that varenicline improves abstinence rates during treatment by approximately 40% compared with nicotine replacement, and by 20% at the end of 6 months of treatment. The review found that varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy is more effective than varenicline alone. In this comparison, based on three trials, there was a 36% higher abstinence rate at 6 months using varenicline plus nicotine replacement. When varenicline use was compared with use of a nicotine patch, bupropion, or e-cigarettes, there was a reduction in serious adverse events – changes in mood, suicidal ideation, and neurological side effects such as seizures.2 Clinicians may remember a black box warning on the varenicline label citing neuropsychiatric effects and it is important to note that the Food and Drug Administration removed this boxed warning in 2016.4

Opinion

This recommendation represents an important, evidence-based change from previous guidelines. It presents the opportunity for better outcomes, but will likely take a while to filter into practice, as clinicians need to become more comfortable with the use of varenicline and insurance supports the cost of varenicline.

The average cost of varenicline for 12 weeks is between $1,220 and $1,584. For comparison, nicotine replacement therapy costs $170 to $240 for the same number of weeks. To put those costs in perspective, the 12-week cost of cigarettes for a two-pack-a-day smoker is approximately $1,000.

For some patients, the motivation to quit smoking comes from the realization of how much they are spending on cigarettes each month. That said, if a patient does not have insurance or their insurance does not cover the cost of varenicline, nicotine replacement therapy might be more appealing. It should be noted that better abstinence rates have been seen in patients taking varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy versus varenicline alone.

Suggested treatment

Based on a systematic review of randomized controlled trials, the American Thoracic Society’s guideline on pharmacological treatment in tobacco-dependent adults concludes that varenicline plus nicotine patch is the preferred pharmacological treatment for tobacco cessation when compared with varenicline alone, bupropion alone, nicotine replacement therapy alone, and e-cigarettes alone. If the patient does not want to start two medicines at once, then varenicline alone would be the preferred choice.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Sprogell is a third-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. For questions or comments, feel free to contact Dr. Skolnik on Twitter @NeilSkolnik.

References

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Primary care interventions for prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA.2020;323(16):1590-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4679.

2. Leone FT et al. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults: An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):e5–e31.

3. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2015 Sep 21.

4. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. 2016 Dec. 16.

Applying American Thoracic Society’s new clinical practice guideline

Applying American Thoracic Society’s new clinical practice guideline

Complications from tobacco use are the most common preventable cause of death, disability, and disease in the United States. Tobacco use causes 480,000 premature deaths every year. In pregnancy, tobacco use causes complications such as premature birth, intrauterine growth restriction, and placental abruption. In the perinatal period, it is associated with sudden infant death syndrome. While cigarette smoking is decreasing in adolescents, e-cigarette use in on the rise. Approximately 1,600 children aged 12-17 smoke their first cigarette every day and it is estimated that 5.6 million children and adolescents will die of a tobacco use–related death.1 For these reasons it is important to address tobacco use and cessation with patients whenever it is possible.

Case

A forty-five-year-old male who rarely comes to the office is here today for a physical exam at the urging of his partner. He has been smoking a pack a day since age 17. You have tried at past visits to discuss quitting, but he had been in the precontemplative stage and had been unwilling to consider any change. This visit, however, he is ready to try to quit. What can you offer him?

Core recommendations from ATS guidelines

This patient can be offered varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy rather than nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, e-cigarettes, or varenicline alone. His course of therapy should extend beyond 12 weeks instead of the standard 6- to 12-week therapy. Alternatively, he could be offered varenicline alone, rather than nicotine replacement.2

A change from previous guidelines

What makes this recommendation so interesting and new is the emphasis it places on varenicline. The United States Preventive Services Task Force released a recommendation statement in 2015 that stressed a combination of pharmacological and behavioral interventions. It discussed nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, and varenicline, but did not recommend any one over any of the others.3 The new recommendation from the American Thoracic Society favors varenicline over other pharmacologic interventions. It is based on an independent systematic review of the literature that showed higher rates of tobacco use abstinence at the 6-month follow-up with varenicline alone versus nicotine replacement therapy alone, bupropion alone, or e-cigarette use only.

A review of 14 randomized controlled trials showed that varenicline improves abstinence rates during treatment by approximately 40% compared with nicotine replacement, and by 20% at the end of 6 months of treatment. The review found that varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy is more effective than varenicline alone. In this comparison, based on three trials, there was a 36% higher abstinence rate at 6 months using varenicline plus nicotine replacement. When varenicline use was compared with use of a nicotine patch, bupropion, or e-cigarettes, there was a reduction in serious adverse events – changes in mood, suicidal ideation, and neurological side effects such as seizures.2 Clinicians may remember a black box warning on the varenicline label citing neuropsychiatric effects and it is important to note that the Food and Drug Administration removed this boxed warning in 2016.4

Opinion

This recommendation represents an important, evidence-based change from previous guidelines. It presents the opportunity for better outcomes, but will likely take a while to filter into practice, as clinicians need to become more comfortable with the use of varenicline and insurance supports the cost of varenicline.

The average cost of varenicline for 12 weeks is between $1,220 and $1,584. For comparison, nicotine replacement therapy costs $170 to $240 for the same number of weeks. To put those costs in perspective, the 12-week cost of cigarettes for a two-pack-a-day smoker is approximately $1,000.

For some patients, the motivation to quit smoking comes from the realization of how much they are spending on cigarettes each month. That said, if a patient does not have insurance or their insurance does not cover the cost of varenicline, nicotine replacement therapy might be more appealing. It should be noted that better abstinence rates have been seen in patients taking varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy versus varenicline alone.

Suggested treatment

Based on a systematic review of randomized controlled trials, the American Thoracic Society’s guideline on pharmacological treatment in tobacco-dependent adults concludes that varenicline plus nicotine patch is the preferred pharmacological treatment for tobacco cessation when compared with varenicline alone, bupropion alone, nicotine replacement therapy alone, and e-cigarettes alone. If the patient does not want to start two medicines at once, then varenicline alone would be the preferred choice.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Sprogell is a third-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. For questions or comments, feel free to contact Dr. Skolnik on Twitter @NeilSkolnik.

References

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Primary care interventions for prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA.2020;323(16):1590-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4679.

2. Leone FT et al. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults: An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):e5–e31.

3. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2015 Sep 21.

4. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. 2016 Dec. 16.

Complications from tobacco use are the most common preventable cause of death, disability, and disease in the United States. Tobacco use causes 480,000 premature deaths every year. In pregnancy, tobacco use causes complications such as premature birth, intrauterine growth restriction, and placental abruption. In the perinatal period, it is associated with sudden infant death syndrome. While cigarette smoking is decreasing in adolescents, e-cigarette use in on the rise. Approximately 1,600 children aged 12-17 smoke their first cigarette every day and it is estimated that 5.6 million children and adolescents will die of a tobacco use–related death.1 For these reasons it is important to address tobacco use and cessation with patients whenever it is possible.

Case

A forty-five-year-old male who rarely comes to the office is here today for a physical exam at the urging of his partner. He has been smoking a pack a day since age 17. You have tried at past visits to discuss quitting, but he had been in the precontemplative stage and had been unwilling to consider any change. This visit, however, he is ready to try to quit. What can you offer him?

Core recommendations from ATS guidelines

This patient can be offered varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy rather than nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, e-cigarettes, or varenicline alone. His course of therapy should extend beyond 12 weeks instead of the standard 6- to 12-week therapy. Alternatively, he could be offered varenicline alone, rather than nicotine replacement.2

A change from previous guidelines

What makes this recommendation so interesting and new is the emphasis it places on varenicline. The United States Preventive Services Task Force released a recommendation statement in 2015 that stressed a combination of pharmacological and behavioral interventions. It discussed nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, and varenicline, but did not recommend any one over any of the others.3 The new recommendation from the American Thoracic Society favors varenicline over other pharmacologic interventions. It is based on an independent systematic review of the literature that showed higher rates of tobacco use abstinence at the 6-month follow-up with varenicline alone versus nicotine replacement therapy alone, bupropion alone, or e-cigarette use only.

A review of 14 randomized controlled trials showed that varenicline improves abstinence rates during treatment by approximately 40% compared with nicotine replacement, and by 20% at the end of 6 months of treatment. The review found that varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy is more effective than varenicline alone. In this comparison, based on three trials, there was a 36% higher abstinence rate at 6 months using varenicline plus nicotine replacement. When varenicline use was compared with use of a nicotine patch, bupropion, or e-cigarettes, there was a reduction in serious adverse events – changes in mood, suicidal ideation, and neurological side effects such as seizures.2 Clinicians may remember a black box warning on the varenicline label citing neuropsychiatric effects and it is important to note that the Food and Drug Administration removed this boxed warning in 2016.4

Opinion

This recommendation represents an important, evidence-based change from previous guidelines. It presents the opportunity for better outcomes, but will likely take a while to filter into practice, as clinicians need to become more comfortable with the use of varenicline and insurance supports the cost of varenicline.

The average cost of varenicline for 12 weeks is between $1,220 and $1,584. For comparison, nicotine replacement therapy costs $170 to $240 for the same number of weeks. To put those costs in perspective, the 12-week cost of cigarettes for a two-pack-a-day smoker is approximately $1,000.

For some patients, the motivation to quit smoking comes from the realization of how much they are spending on cigarettes each month. That said, if a patient does not have insurance or their insurance does not cover the cost of varenicline, nicotine replacement therapy might be more appealing. It should be noted that better abstinence rates have been seen in patients taking varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy versus varenicline alone.

Suggested treatment

Based on a systematic review of randomized controlled trials, the American Thoracic Society’s guideline on pharmacological treatment in tobacco-dependent adults concludes that varenicline plus nicotine patch is the preferred pharmacological treatment for tobacco cessation when compared with varenicline alone, bupropion alone, nicotine replacement therapy alone, and e-cigarettes alone. If the patient does not want to start two medicines at once, then varenicline alone would be the preferred choice.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Sprogell is a third-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. For questions or comments, feel free to contact Dr. Skolnik on Twitter @NeilSkolnik.

References

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Primary care interventions for prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA.2020;323(16):1590-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4679.

2. Leone FT et al. Initiating pharmacologic treatment in tobacco-dependent adults: An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):e5–e31.

3. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2015 Sep 21.

4. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. 2016 Dec. 16.

COVID-19: Optimizing therapeutic strategies for children, adolescents with ADHD

Recently, the Yakima Health District (YHD), in collaboration with the Washington State Department of Health, issued dramatic revisions to its educational curriculum, opting for exclusively remote learning as an important next step in COVID-19 containment measures.

The newly implemented “enhanced” distance-learning paradigm has garnered considerable national attention. Even more noteworthy is how YHD addressed those with language barriers and learning differences such as ADHD as a “priority group”; these individuals are exempt from the newly implemented measures, and small instructional groups of no more than five “at-risk” students will be directly supervised by specialized educators.1,2 To overcome these new unprecedented challenges from the coronavirus pandemic, especially from the perspective of distance education and mental health for susceptible groups such as those with ADHD, it is of utmost importance to explore various programs of interest, as well as the targeted therapies being considered during this crisis.

From a therapeutic standpoint, individuals with learning differences are more likely to play catch-up with their age-matched peers. This puts them at significant risk for developmental delays with symptoms manifesting as disruptive behavioral issues. This is why ongoing parental guidance, coupled with a paradoxically stimulating environment, is critical for children and adolescents with ADHD.3 Accumulating evidence, based on a myriad of studies, demonstrates that childhood treatment with ADHD stimulants reduces the incidence of future substance use, as well as that of other negative outcomes.4,5

Therapeutic strategies that work

“The new normal” has forced unique challenges on clinicians for mitigating distress by novel means of health care delivery. Given the paucity of research exploring the interactions of individuals with ADHD within the context of COVID-19, Take for example, the suggested guidelines from the European ADHD Guidelines Group (EAGG) – such as the following:

- Telecommunications in general, and telepsychiatry in particular, should function as the primary mode of health care delivery to fulfill societal standards of physical distancing.

- Children and adolescents with ADHD should be designated as a “priority group” with respect to monitoring initiatives by educators in a school setting, be it virtual or otherwise.

- Implementation of behavioral strategies by parent or guardian to address psychological well-being and reduce the presence of comorbid behavioral conditions (such as oppositional defiant disorder).

In addition to the aforementioned guidance, EAGG maintains that individuals with ADHD may be initiated on medications after the completion of a baseline examination; if the patients in question are already on a treatment regimen, they should proceed with it as indicated. Interruptions to therapy are not ideal because patients are then subjected to health-related stressors of COVID-19. Reasonable regulations concerning access to medications, without unnecessary delays, undoubtedly will facilitate patient needs, allowing for a smooth transition in day-to-day activities. The family, as a cohesive unit, may benefit from reeducation because it contributes toward the therapeutic process. Neurofeedback, coping skills, and cognitive restructuring training are potential modalities that can augment medications.

Although it may seem counterintuitive, parents or caregivers should resist the urge to increase the medication dose during an outbreak with the intended goal of diminishing the psychosocial burden of ADHD symptomatology. Likewise, unless indicated by a specialist, antipsychotics and/or hypnotics should not be introduced for addressing behavioral dysregulation (such as agitation) during the confinement period.

Historically, numerous clinicians have suggested that patients undergo a routine cardiovascular examination and EKG before being prescribed psychostimulants (the rationale for this recommendation is that sympathomimetics unduly affect blood pressure and heart rate).6,7 However, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Heart Association (AHA) eventually amended their previous stance by releasing a joint statement in which they deemed a baseline EKG necessary only in ADHD patients with preexisting cardiac risk. For all other patients, the use of EKGs was entirely contingent on physician discretion. However, given the nature of safety precautions for COVID-19, it is prudent to discourage or delay in-person cardiovascular examination/monitoring protocols altogether, especially in those patients without known heart conditions.

Another area of concern is sleep dysfunction, which might exist as an untoward effect of ADHD medication intake or because of the presence of COVID-19 psychosocial stressors. However, clinicians advise that unnecessary psychopharmacology (such as hypnotics or melatonin) be avoided. Instead, conservative lifestyle measures should be enacted, emphasizing the role of proper sleep hygiene in maintaining optimal behavioral health. Despite setbacks to in-person appointments, patients are expected to continue their pharmacotherapy with “parent-focused” ADHD interventions taking a primary role in facilitating compliance through remote monitoring.

ADMiRE, a tertiary-level, dedicated ADHD intervention program from South Dublin, Ireland, has identified several roadblocks with respect to streamlining health care for individuals with ADHD during the confinement period. The proposed resolution to these issues, some of which are derived from EAGG guidelines, might have universal applications elsewhere, thereby facilitating the development of therapeutic services of interest. ADMiRE has noted a correspondence between the guidelines established by EAGG and that of the Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance (CADDRA), including minimal in-person interactions (in favor of virtual teleconferencing) and a cardiovascular screen can be performed in lieu of baseline cardiac auscultation. Moreover, in the event that the patient is a low cardiac risk candidate for ADHD treatment, monitoring protocols may be continued from a home setting. However, if a physical examination is indicated, CADDRA recommends the use of precautionary PPE before commencing ADHD pharmacotherapy.

One of the most significant hurdles is that of school closures because teacher feedback for baseline behavior was traditionally instrumental in dictating patient medical management (for example, for titration schedule). It is expected that, for the time being, this role will be supplanted by parental reports. As well as disclosing information on behavioral dysregulation, family members should be trained to relay critical information about the development of stimulant-induced cardiovascular symptoms – namely, dyspnea, chest pain, and/or palpitations. Furthermore, as primary caregivers, parents should harbor a certain degree of emotional sensitivity because their mood state may influence the child’s overall behavioral course in terms of symptom exacerbation.8

Toward adopting an integrated model for care

Developing an effective assessment plan for patients with ADHD often proves to be a challenging task for clinicians, perhaps even more so in environments that enforce social distancing and limited physical contact by default. As a neurodevelopmental disorder from childhood, the symptoms (including inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity) of ADHD do not arise in a vacuum – comorbid conditions include mood and anxiety disorders, which are complicated further by a background risk for substance use and self-medicating tendencies.9 Unfortunately, the pandemic has limited the breadth of non-COVID doctors visits, which hinders the overall diagnostic and monitoring process for identifiable comorbid conditions, such as autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, oppositional defiant and conduct disorders, and so on.10 Since ADHD symptoms cannot be treated by pharmacotherapy or behavioral interventions alone, our team advocates that families provide additional emotional support and continuous encouragement during these uncertain times.

ADHD and the self-medication hypothesis

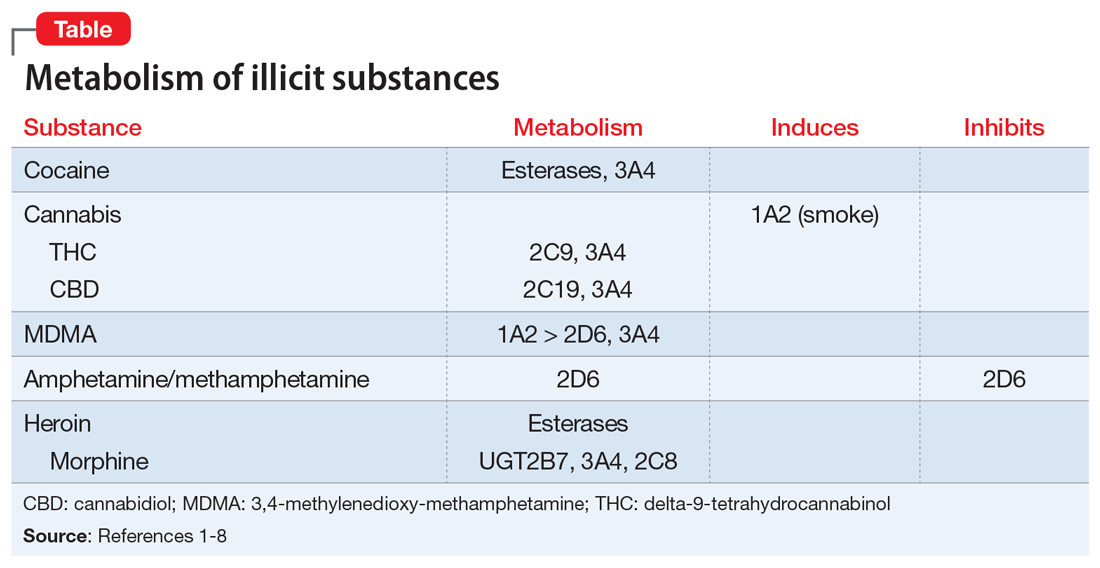

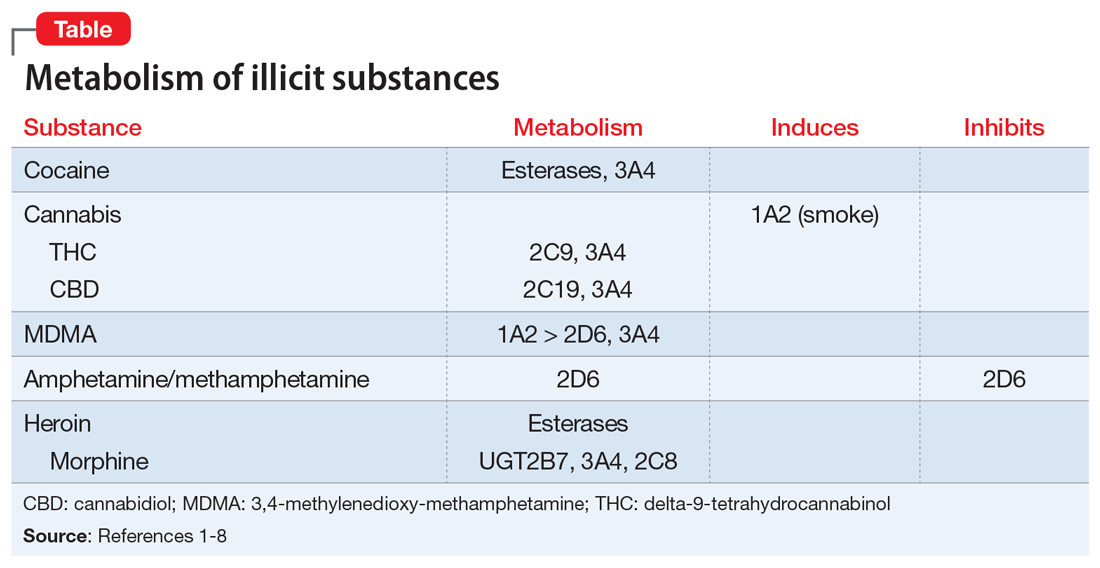

The Khantzian self-medication hypothesis posits that a drug seeker may subconsciously gravitate toward a particular agent only to discover a sense of relief concerning inner turmoil or restlessness after use. Observations support the notion that individuals with undiagnosed ADHD have sought cocaine or even recreational designer drugs (such as methylenedioxypyrovalerone, or “bath salts”).11 Given the similar mechanism of action between cocaine, methylenedioxypyrovalerone, and prescribed psychostimulants such as methylphenidate, the results are hardly surprising because these agents all work on the brain’s “reward center” (for example, the nucleus accumbens) by invoking dopamine release. Aside from the aforementioned self-medication hypothesis, “downers” such as Xanax recently have experienced a prescription spike during the outbreak. While there isn’t an immediate cause for concern of Xanax abuse in ADHD individuals, the potential for addiction is certainly real, especially when taking into account comorbid anxiety disorder or sleep dysfunction.

Because of limited resources and precautionary guidelines, clinicians are at a considerable disadvantage in terms of formulating a comprehensive diagnostic and treatment plan for children and adolescents with ADHD. This situation is further compounded by the recent closure of schools and the lack of feedback with respect to baseline behavior from teachers and specialized educators. This is why it is imperative for primary caregivers to closely monitor children with ADHD for developing changes in behavioral patterns (for example, mood or anxiety issues and drug-seeking or disruptive behavior) and work with health care professionals.

References

1. “Distance learning strongly recommended for all Yakima county schools.” NBC Right Now. 2020 Aug 5.

2. Retka J. “Enhanced” remote learning in Yakima county schools? What that means for students this fall. Yakima Herald-Republic. 2020 Aug 8.

3. Armstrong T. “To empower! Not Control! A holistic approach to ADHD.” American Institute for Learning and Development. 1998.

4. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014 Aug;55(8):878-85.

5. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020 May 21:1-22.

6. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020 Jun;4(6):412-4.

7. O’Keefe L. AAP News. 2008 Jun;29(6):1.

8. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Jun;51:102077.

9. Current Psychiatry. 2015 Dec;14(12):e3-4.

10. Encephale. 2020 Jun 7;46(3S):S85-92.

11. Current Psychiatry. 2014 Dec; 3(12): e3-4.

Dr. Islam is a medical adviser for the International Maternal and Child Health Foundation (IMCHF), Montreal, and is based in New York. He also is a postdoctoral fellow, psychopharmacologist, and a board-certified medical affairs specialist. Dr. Islam disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Zaid Ulhaq Choudhry is a research assistant at the IMCHF. He has no disclosures. Dr. Zia Choudhry is the chief scientific officer and head of the department of mental health and clini-cal research at the IMCHF and is Mr. Choudhry’s father. He has no disclosures.

Recently, the Yakima Health District (YHD), in collaboration with the Washington State Department of Health, issued dramatic revisions to its educational curriculum, opting for exclusively remote learning as an important next step in COVID-19 containment measures.

The newly implemented “enhanced” distance-learning paradigm has garnered considerable national attention. Even more noteworthy is how YHD addressed those with language barriers and learning differences such as ADHD as a “priority group”; these individuals are exempt from the newly implemented measures, and small instructional groups of no more than five “at-risk” students will be directly supervised by specialized educators.1,2 To overcome these new unprecedented challenges from the coronavirus pandemic, especially from the perspective of distance education and mental health for susceptible groups such as those with ADHD, it is of utmost importance to explore various programs of interest, as well as the targeted therapies being considered during this crisis.

From a therapeutic standpoint, individuals with learning differences are more likely to play catch-up with their age-matched peers. This puts them at significant risk for developmental delays with symptoms manifesting as disruptive behavioral issues. This is why ongoing parental guidance, coupled with a paradoxically stimulating environment, is critical for children and adolescents with ADHD.3 Accumulating evidence, based on a myriad of studies, demonstrates that childhood treatment with ADHD stimulants reduces the incidence of future substance use, as well as that of other negative outcomes.4,5

Therapeutic strategies that work

“The new normal” has forced unique challenges on clinicians for mitigating distress by novel means of health care delivery. Given the paucity of research exploring the interactions of individuals with ADHD within the context of COVID-19, Take for example, the suggested guidelines from the European ADHD Guidelines Group (EAGG) – such as the following:

- Telecommunications in general, and telepsychiatry in particular, should function as the primary mode of health care delivery to fulfill societal standards of physical distancing.

- Children and adolescents with ADHD should be designated as a “priority group” with respect to monitoring initiatives by educators in a school setting, be it virtual or otherwise.

- Implementation of behavioral strategies by parent or guardian to address psychological well-being and reduce the presence of comorbid behavioral conditions (such as oppositional defiant disorder).

In addition to the aforementioned guidance, EAGG maintains that individuals with ADHD may be initiated on medications after the completion of a baseline examination; if the patients in question are already on a treatment regimen, they should proceed with it as indicated. Interruptions to therapy are not ideal because patients are then subjected to health-related stressors of COVID-19. Reasonable regulations concerning access to medications, without unnecessary delays, undoubtedly will facilitate patient needs, allowing for a smooth transition in day-to-day activities. The family, as a cohesive unit, may benefit from reeducation because it contributes toward the therapeutic process. Neurofeedback, coping skills, and cognitive restructuring training are potential modalities that can augment medications.

Although it may seem counterintuitive, parents or caregivers should resist the urge to increase the medication dose during an outbreak with the intended goal of diminishing the psychosocial burden of ADHD symptomatology. Likewise, unless indicated by a specialist, antipsychotics and/or hypnotics should not be introduced for addressing behavioral dysregulation (such as agitation) during the confinement period.

Historically, numerous clinicians have suggested that patients undergo a routine cardiovascular examination and EKG before being prescribed psychostimulants (the rationale for this recommendation is that sympathomimetics unduly affect blood pressure and heart rate).6,7 However, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Heart Association (AHA) eventually amended their previous stance by releasing a joint statement in which they deemed a baseline EKG necessary only in ADHD patients with preexisting cardiac risk. For all other patients, the use of EKGs was entirely contingent on physician discretion. However, given the nature of safety precautions for COVID-19, it is prudent to discourage or delay in-person cardiovascular examination/monitoring protocols altogether, especially in those patients without known heart conditions.

Another area of concern is sleep dysfunction, which might exist as an untoward effect of ADHD medication intake or because of the presence of COVID-19 psychosocial stressors. However, clinicians advise that unnecessary psychopharmacology (such as hypnotics or melatonin) be avoided. Instead, conservative lifestyle measures should be enacted, emphasizing the role of proper sleep hygiene in maintaining optimal behavioral health. Despite setbacks to in-person appointments, patients are expected to continue their pharmacotherapy with “parent-focused” ADHD interventions taking a primary role in facilitating compliance through remote monitoring.

ADMiRE, a tertiary-level, dedicated ADHD intervention program from South Dublin, Ireland, has identified several roadblocks with respect to streamlining health care for individuals with ADHD during the confinement period. The proposed resolution to these issues, some of which are derived from EAGG guidelines, might have universal applications elsewhere, thereby facilitating the development of therapeutic services of interest. ADMiRE has noted a correspondence between the guidelines established by EAGG and that of the Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance (CADDRA), including minimal in-person interactions (in favor of virtual teleconferencing) and a cardiovascular screen can be performed in lieu of baseline cardiac auscultation. Moreover, in the event that the patient is a low cardiac risk candidate for ADHD treatment, monitoring protocols may be continued from a home setting. However, if a physical examination is indicated, CADDRA recommends the use of precautionary PPE before commencing ADHD pharmacotherapy.

One of the most significant hurdles is that of school closures because teacher feedback for baseline behavior was traditionally instrumental in dictating patient medical management (for example, for titration schedule). It is expected that, for the time being, this role will be supplanted by parental reports. As well as disclosing information on behavioral dysregulation, family members should be trained to relay critical information about the development of stimulant-induced cardiovascular symptoms – namely, dyspnea, chest pain, and/or palpitations. Furthermore, as primary caregivers, parents should harbor a certain degree of emotional sensitivity because their mood state may influence the child’s overall behavioral course in terms of symptom exacerbation.8

Toward adopting an integrated model for care

Developing an effective assessment plan for patients with ADHD often proves to be a challenging task for clinicians, perhaps even more so in environments that enforce social distancing and limited physical contact by default. As a neurodevelopmental disorder from childhood, the symptoms (including inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity) of ADHD do not arise in a vacuum – comorbid conditions include mood and anxiety disorders, which are complicated further by a background risk for substance use and self-medicating tendencies.9 Unfortunately, the pandemic has limited the breadth of non-COVID doctors visits, which hinders the overall diagnostic and monitoring process for identifiable comorbid conditions, such as autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, oppositional defiant and conduct disorders, and so on.10 Since ADHD symptoms cannot be treated by pharmacotherapy or behavioral interventions alone, our team advocates that families provide additional emotional support and continuous encouragement during these uncertain times.

ADHD and the self-medication hypothesis

The Khantzian self-medication hypothesis posits that a drug seeker may subconsciously gravitate toward a particular agent only to discover a sense of relief concerning inner turmoil or restlessness after use. Observations support the notion that individuals with undiagnosed ADHD have sought cocaine or even recreational designer drugs (such as methylenedioxypyrovalerone, or “bath salts”).11 Given the similar mechanism of action between cocaine, methylenedioxypyrovalerone, and prescribed psychostimulants such as methylphenidate, the results are hardly surprising because these agents all work on the brain’s “reward center” (for example, the nucleus accumbens) by invoking dopamine release. Aside from the aforementioned self-medication hypothesis, “downers” such as Xanax recently have experienced a prescription spike during the outbreak. While there isn’t an immediate cause for concern of Xanax abuse in ADHD individuals, the potential for addiction is certainly real, especially when taking into account comorbid anxiety disorder or sleep dysfunction.

Because of limited resources and precautionary guidelines, clinicians are at a considerable disadvantage in terms of formulating a comprehensive diagnostic and treatment plan for children and adolescents with ADHD. This situation is further compounded by the recent closure of schools and the lack of feedback with respect to baseline behavior from teachers and specialized educators. This is why it is imperative for primary caregivers to closely monitor children with ADHD for developing changes in behavioral patterns (for example, mood or anxiety issues and drug-seeking or disruptive behavior) and work with health care professionals.

References

1. “Distance learning strongly recommended for all Yakima county schools.” NBC Right Now. 2020 Aug 5.

2. Retka J. “Enhanced” remote learning in Yakima county schools? What that means for students this fall. Yakima Herald-Republic. 2020 Aug 8.

3. Armstrong T. “To empower! Not Control! A holistic approach to ADHD.” American Institute for Learning and Development. 1998.

4. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014 Aug;55(8):878-85.

5. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020 May 21:1-22.

6. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020 Jun;4(6):412-4.

7. O’Keefe L. AAP News. 2008 Jun;29(6):1.

8. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Jun;51:102077.

9. Current Psychiatry. 2015 Dec;14(12):e3-4.

10. Encephale. 2020 Jun 7;46(3S):S85-92.

11. Current Psychiatry. 2014 Dec; 3(12): e3-4.

Dr. Islam is a medical adviser for the International Maternal and Child Health Foundation (IMCHF), Montreal, and is based in New York. He also is a postdoctoral fellow, psychopharmacologist, and a board-certified medical affairs specialist. Dr. Islam disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Zaid Ulhaq Choudhry is a research assistant at the IMCHF. He has no disclosures. Dr. Zia Choudhry is the chief scientific officer and head of the department of mental health and clini-cal research at the IMCHF and is Mr. Choudhry’s father. He has no disclosures.

Recently, the Yakima Health District (YHD), in collaboration with the Washington State Department of Health, issued dramatic revisions to its educational curriculum, opting for exclusively remote learning as an important next step in COVID-19 containment measures.

The newly implemented “enhanced” distance-learning paradigm has garnered considerable national attention. Even more noteworthy is how YHD addressed those with language barriers and learning differences such as ADHD as a “priority group”; these individuals are exempt from the newly implemented measures, and small instructional groups of no more than five “at-risk” students will be directly supervised by specialized educators.1,2 To overcome these new unprecedented challenges from the coronavirus pandemic, especially from the perspective of distance education and mental health for susceptible groups such as those with ADHD, it is of utmost importance to explore various programs of interest, as well as the targeted therapies being considered during this crisis.

From a therapeutic standpoint, individuals with learning differences are more likely to play catch-up with their age-matched peers. This puts them at significant risk for developmental delays with symptoms manifesting as disruptive behavioral issues. This is why ongoing parental guidance, coupled with a paradoxically stimulating environment, is critical for children and adolescents with ADHD.3 Accumulating evidence, based on a myriad of studies, demonstrates that childhood treatment with ADHD stimulants reduces the incidence of future substance use, as well as that of other negative outcomes.4,5

Therapeutic strategies that work

“The new normal” has forced unique challenges on clinicians for mitigating distress by novel means of health care delivery. Given the paucity of research exploring the interactions of individuals with ADHD within the context of COVID-19, Take for example, the suggested guidelines from the European ADHD Guidelines Group (EAGG) – such as the following:

- Telecommunications in general, and telepsychiatry in particular, should function as the primary mode of health care delivery to fulfill societal standards of physical distancing.

- Children and adolescents with ADHD should be designated as a “priority group” with respect to monitoring initiatives by educators in a school setting, be it virtual or otherwise.

- Implementation of behavioral strategies by parent or guardian to address psychological well-being and reduce the presence of comorbid behavioral conditions (such as oppositional defiant disorder).

In addition to the aforementioned guidance, EAGG maintains that individuals with ADHD may be initiated on medications after the completion of a baseline examination; if the patients in question are already on a treatment regimen, they should proceed with it as indicated. Interruptions to therapy are not ideal because patients are then subjected to health-related stressors of COVID-19. Reasonable regulations concerning access to medications, without unnecessary delays, undoubtedly will facilitate patient needs, allowing for a smooth transition in day-to-day activities. The family, as a cohesive unit, may benefit from reeducation because it contributes toward the therapeutic process. Neurofeedback, coping skills, and cognitive restructuring training are potential modalities that can augment medications.

Although it may seem counterintuitive, parents or caregivers should resist the urge to increase the medication dose during an outbreak with the intended goal of diminishing the psychosocial burden of ADHD symptomatology. Likewise, unless indicated by a specialist, antipsychotics and/or hypnotics should not be introduced for addressing behavioral dysregulation (such as agitation) during the confinement period.

Historically, numerous clinicians have suggested that patients undergo a routine cardiovascular examination and EKG before being prescribed psychostimulants (the rationale for this recommendation is that sympathomimetics unduly affect blood pressure and heart rate).6,7 However, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Heart Association (AHA) eventually amended their previous stance by releasing a joint statement in which they deemed a baseline EKG necessary only in ADHD patients with preexisting cardiac risk. For all other patients, the use of EKGs was entirely contingent on physician discretion. However, given the nature of safety precautions for COVID-19, it is prudent to discourage or delay in-person cardiovascular examination/monitoring protocols altogether, especially in those patients without known heart conditions.

Another area of concern is sleep dysfunction, which might exist as an untoward effect of ADHD medication intake or because of the presence of COVID-19 psychosocial stressors. However, clinicians advise that unnecessary psychopharmacology (such as hypnotics or melatonin) be avoided. Instead, conservative lifestyle measures should be enacted, emphasizing the role of proper sleep hygiene in maintaining optimal behavioral health. Despite setbacks to in-person appointments, patients are expected to continue their pharmacotherapy with “parent-focused” ADHD interventions taking a primary role in facilitating compliance through remote monitoring.

ADMiRE, a tertiary-level, dedicated ADHD intervention program from South Dublin, Ireland, has identified several roadblocks with respect to streamlining health care for individuals with ADHD during the confinement period. The proposed resolution to these issues, some of which are derived from EAGG guidelines, might have universal applications elsewhere, thereby facilitating the development of therapeutic services of interest. ADMiRE has noted a correspondence between the guidelines established by EAGG and that of the Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance (CADDRA), including minimal in-person interactions (in favor of virtual teleconferencing) and a cardiovascular screen can be performed in lieu of baseline cardiac auscultation. Moreover, in the event that the patient is a low cardiac risk candidate for ADHD treatment, monitoring protocols may be continued from a home setting. However, if a physical examination is indicated, CADDRA recommends the use of precautionary PPE before commencing ADHD pharmacotherapy.

One of the most significant hurdles is that of school closures because teacher feedback for baseline behavior was traditionally instrumental in dictating patient medical management (for example, for titration schedule). It is expected that, for the time being, this role will be supplanted by parental reports. As well as disclosing information on behavioral dysregulation, family members should be trained to relay critical information about the development of stimulant-induced cardiovascular symptoms – namely, dyspnea, chest pain, and/or palpitations. Furthermore, as primary caregivers, parents should harbor a certain degree of emotional sensitivity because their mood state may influence the child’s overall behavioral course in terms of symptom exacerbation.8

Toward adopting an integrated model for care

Developing an effective assessment plan for patients with ADHD often proves to be a challenging task for clinicians, perhaps even more so in environments that enforce social distancing and limited physical contact by default. As a neurodevelopmental disorder from childhood, the symptoms (including inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity) of ADHD do not arise in a vacuum – comorbid conditions include mood and anxiety disorders, which are complicated further by a background risk for substance use and self-medicating tendencies.9 Unfortunately, the pandemic has limited the breadth of non-COVID doctors visits, which hinders the overall diagnostic and monitoring process for identifiable comorbid conditions, such as autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, oppositional defiant and conduct disorders, and so on.10 Since ADHD symptoms cannot be treated by pharmacotherapy or behavioral interventions alone, our team advocates that families provide additional emotional support and continuous encouragement during these uncertain times.

ADHD and the self-medication hypothesis

The Khantzian self-medication hypothesis posits that a drug seeker may subconsciously gravitate toward a particular agent only to discover a sense of relief concerning inner turmoil or restlessness after use. Observations support the notion that individuals with undiagnosed ADHD have sought cocaine or even recreational designer drugs (such as methylenedioxypyrovalerone, or “bath salts”).11 Given the similar mechanism of action between cocaine, methylenedioxypyrovalerone, and prescribed psychostimulants such as methylphenidate, the results are hardly surprising because these agents all work on the brain’s “reward center” (for example, the nucleus accumbens) by invoking dopamine release. Aside from the aforementioned self-medication hypothesis, “downers” such as Xanax recently have experienced a prescription spike during the outbreak. While there isn’t an immediate cause for concern of Xanax abuse in ADHD individuals, the potential for addiction is certainly real, especially when taking into account comorbid anxiety disorder or sleep dysfunction.

Because of limited resources and precautionary guidelines, clinicians are at a considerable disadvantage in terms of formulating a comprehensive diagnostic and treatment plan for children and adolescents with ADHD. This situation is further compounded by the recent closure of schools and the lack of feedback with respect to baseline behavior from teachers and specialized educators. This is why it is imperative for primary caregivers to closely monitor children with ADHD for developing changes in behavioral patterns (for example, mood or anxiety issues and drug-seeking or disruptive behavior) and work with health care professionals.

References

1. “Distance learning strongly recommended for all Yakima county schools.” NBC Right Now. 2020 Aug 5.

2. Retka J. “Enhanced” remote learning in Yakima county schools? What that means for students this fall. Yakima Herald-Republic. 2020 Aug 8.

3. Armstrong T. “To empower! Not Control! A holistic approach to ADHD.” American Institute for Learning and Development. 1998.

4. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014 Aug;55(8):878-85.

5. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020 May 21:1-22.

6. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020 Jun;4(6):412-4.

7. O’Keefe L. AAP News. 2008 Jun;29(6):1.

8. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Jun;51:102077.

9. Current Psychiatry. 2015 Dec;14(12):e3-4.

10. Encephale. 2020 Jun 7;46(3S):S85-92.

11. Current Psychiatry. 2014 Dec; 3(12): e3-4.

Dr. Islam is a medical adviser for the International Maternal and Child Health Foundation (IMCHF), Montreal, and is based in New York. He also is a postdoctoral fellow, psychopharmacologist, and a board-certified medical affairs specialist. Dr. Islam disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Zaid Ulhaq Choudhry is a research assistant at the IMCHF. He has no disclosures. Dr. Zia Choudhry is the chief scientific officer and head of the department of mental health and clini-cal research at the IMCHF and is Mr. Choudhry’s father. He has no disclosures.

Frequent cannabis use in depression tripled over past decade

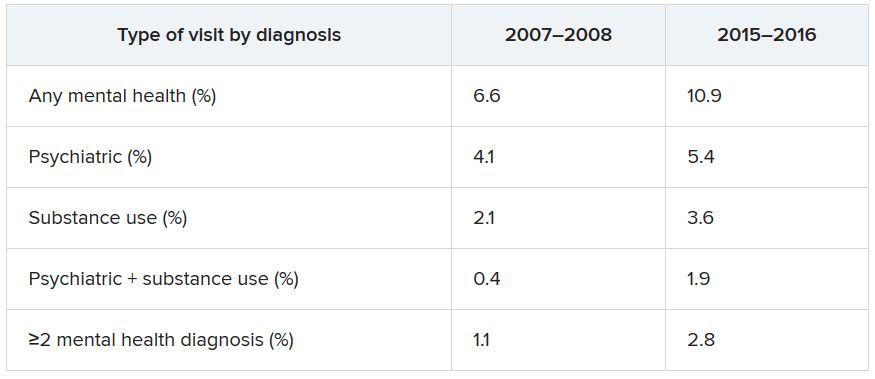

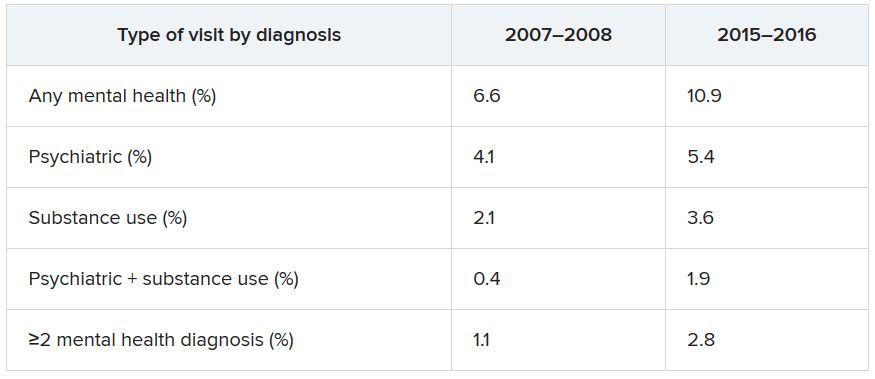

Not only are individuals with depression at significantly higher risk for cannabis use, compared with those without depression, this trend has increased dramatically over the last decade, new research shows.

Investigators analyzed data from more than 16,000 U.S. adults between the ages of 20 and 59 years and found that those with depression had almost twice the odds of any past-month cannabis use compared with those without depression. Odds rose from 1.5 in the 2005-2006 period to 2.3 in the 2015-2016 period.

Moreover, the odds ratio for daily or near-daily use almost tripled for those with versus without depression between the two periods.

“Clinicians should screen their depressed patients for cannabis use, since this is becoming more common and could actually make their depressive symptoms worse rather than better,” senior author Deborah Hasin, PhD, professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York City, told Medscape Medical News.

The results were published online August 18 in JAMA Network Open.

Misleading advertising

“Cannabis use is increasing in the U.S. and the potency of cannabis products is increasing as well,” Dr. Hasin said.

“Misleading media information and advertising suggests that cannabis is a good treatment for depression, although studies show that cannabis use may actually worsen depression symptoms, [so] we were interested in whether U.S. adults were increasingly likely to be cannabis users if they were depressed,” she reported.

To investigate, the researchers assessed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), with a final study sample consisting of 16,216 U.S. adults. The mean age was 39.12 years, 48.9% were men, 66.4% were non-Hispanic White, 65.6% had at least some college education, and 62.4% had an annual family income of less than $75,000.

Of these participants, 7.5% had “probable depression,” based on the Patient Health Questionnaire–9, the investigators report.

Past-month cannabis use was defined as using cannabis at least once during the past 20 days. Daily or near-daily past-month use was defined as using cannabis at least 20 times in the past 30 days.

Covariates included age, gender, race, education, marital status, annual family income, and past-year use of other substances, such as alcohol, heroin, and methamphetamine.

The researchers note that because the NHANES data were divided into six survey years (2005-2006, 2007-2008, 2009-2010, 2011-2012, 2013-2014, and 2015-2016), their analysis was based on a “new sample weight” that combined the datasets.

Especially pronounced

Results showed that the prevalence of any past-month cannabis use in the overall sample group increased from 12.2% in the 2005-2006 period to 17.3% in the 2015-2016 period (P < .001).

The investigators characterized this change as “significant,” adding that the estimated odds of cannabis use increased by approximately 9% between every 2-year time period.

The change was even more dramatic when the increase was examined across survey time periods (OR, 1.12; P < .001). The estimated odds of daily or near-daily use increased by approximately 12% between every 2-year period.

Interestingly, however, there were no significant changes in odds for depression when consecutive survey years were compared.

When the researchers specifically focused on the association between any past-month cannabis use and depression versus no depression, they found an adjusted OR of 1.90 (95% CI, 1.62-2.12; P < .001).

Individuals with depression also had 2.29 (95% CI, 1.80-2.92) times the odds for daily or near-daily cannabis use, compared with those without depression.

A post-hoc analysis looked at time trends in a sample group that included those missing information on at least one covariate (n = 17,724 participants). It showed similar results to those in the final sample that included no missing data.

People with depression have increased risk of using “most substances that can be abused,” Dr. Hasin said. “However, with the overall rates of cannabis use increasing in the general population, this is becoming especially pronounced for cannabis.”

Clear implications

Commenting on the findings for Medscape Medical News, Deepak D’Souza, MD, professor of psychiatry, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said there is “concern about the unsubstantiated claims of cannabis having a beneficial effect in psychiatric disorders, the most common being depression.”

Dr. D’Souza, who was not involved with the study, called it “yet another piece of evidence suggesting that over the period of time during which cannabis laws have been liberalized, rates of past-month and daily cannabis use have increased, whereas rates of other substances, including alcohol, have remained stable.”

He suggested that a common limitation of epidemiological studies is that it is difficult to tell the direction of the association, “and it could be bidirectional.”

Nevertheless, there are clear implications for the practicing clinician, he added.

“If people have a history of depression, one should ask patients about the use of cannabis and also remind them about potential psychiatric negative effects of use,” Dr. D’Souza noted.

For the general public, “the point is that there is no good evidence to support cannabis use in depression treatment and, in fact, people with depression might be more likely to use it in problematic way,” he said.

Dr. Hasin agreed that it is “certainly possible that the relationship between cannabis use and depression is bidirectional, but the mechanism of this association requires more study.”

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Dr. Hasin and by the New York State Psychiatric Institute. The study authors and Dr. D’Souza disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Not only are individuals with depression at significantly higher risk for cannabis use, compared with those without depression, this trend has increased dramatically over the last decade, new research shows.

Investigators analyzed data from more than 16,000 U.S. adults between the ages of 20 and 59 years and found that those with depression had almost twice the odds of any past-month cannabis use compared with those without depression. Odds rose from 1.5 in the 2005-2006 period to 2.3 in the 2015-2016 period.

Moreover, the odds ratio for daily or near-daily use almost tripled for those with versus without depression between the two periods.

“Clinicians should screen their depressed patients for cannabis use, since this is becoming more common and could actually make their depressive symptoms worse rather than better,” senior author Deborah Hasin, PhD, professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York City, told Medscape Medical News.

The results were published online August 18 in JAMA Network Open.

Misleading advertising

“Cannabis use is increasing in the U.S. and the potency of cannabis products is increasing as well,” Dr. Hasin said.

“Misleading media information and advertising suggests that cannabis is a good treatment for depression, although studies show that cannabis use may actually worsen depression symptoms, [so] we were interested in whether U.S. adults were increasingly likely to be cannabis users if they were depressed,” she reported.

To investigate, the researchers assessed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), with a final study sample consisting of 16,216 U.S. adults. The mean age was 39.12 years, 48.9% were men, 66.4% were non-Hispanic White, 65.6% had at least some college education, and 62.4% had an annual family income of less than $75,000.

Of these participants, 7.5% had “probable depression,” based on the Patient Health Questionnaire–9, the investigators report.

Past-month cannabis use was defined as using cannabis at least once during the past 20 days. Daily or near-daily past-month use was defined as using cannabis at least 20 times in the past 30 days.

Covariates included age, gender, race, education, marital status, annual family income, and past-year use of other substances, such as alcohol, heroin, and methamphetamine.

The researchers note that because the NHANES data were divided into six survey years (2005-2006, 2007-2008, 2009-2010, 2011-2012, 2013-2014, and 2015-2016), their analysis was based on a “new sample weight” that combined the datasets.

Especially pronounced

Results showed that the prevalence of any past-month cannabis use in the overall sample group increased from 12.2% in the 2005-2006 period to 17.3% in the 2015-2016 period (P < .001).

The investigators characterized this change as “significant,” adding that the estimated odds of cannabis use increased by approximately 9% between every 2-year time period.

The change was even more dramatic when the increase was examined across survey time periods (OR, 1.12; P < .001). The estimated odds of daily or near-daily use increased by approximately 12% between every 2-year period.

Interestingly, however, there were no significant changes in odds for depression when consecutive survey years were compared.

When the researchers specifically focused on the association between any past-month cannabis use and depression versus no depression, they found an adjusted OR of 1.90 (95% CI, 1.62-2.12; P < .001).

Individuals with depression also had 2.29 (95% CI, 1.80-2.92) times the odds for daily or near-daily cannabis use, compared with those without depression.

A post-hoc analysis looked at time trends in a sample group that included those missing information on at least one covariate (n = 17,724 participants). It showed similar results to those in the final sample that included no missing data.

People with depression have increased risk of using “most substances that can be abused,” Dr. Hasin said. “However, with the overall rates of cannabis use increasing in the general population, this is becoming especially pronounced for cannabis.”

Clear implications

Commenting on the findings for Medscape Medical News, Deepak D’Souza, MD, professor of psychiatry, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said there is “concern about the unsubstantiated claims of cannabis having a beneficial effect in psychiatric disorders, the most common being depression.”

Dr. D’Souza, who was not involved with the study, called it “yet another piece of evidence suggesting that over the period of time during which cannabis laws have been liberalized, rates of past-month and daily cannabis use have increased, whereas rates of other substances, including alcohol, have remained stable.”

He suggested that a common limitation of epidemiological studies is that it is difficult to tell the direction of the association, “and it could be bidirectional.”

Nevertheless, there are clear implications for the practicing clinician, he added.

“If people have a history of depression, one should ask patients about the use of cannabis and also remind them about potential psychiatric negative effects of use,” Dr. D’Souza noted.

For the general public, “the point is that there is no good evidence to support cannabis use in depression treatment and, in fact, people with depression might be more likely to use it in problematic way,” he said.

Dr. Hasin agreed that it is “certainly possible that the relationship between cannabis use and depression is bidirectional, but the mechanism of this association requires more study.”

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Dr. Hasin and by the New York State Psychiatric Institute. The study authors and Dr. D’Souza disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Not only are individuals with depression at significantly higher risk for cannabis use, compared with those without depression, this trend has increased dramatically over the last decade, new research shows.

Investigators analyzed data from more than 16,000 U.S. adults between the ages of 20 and 59 years and found that those with depression had almost twice the odds of any past-month cannabis use compared with those without depression. Odds rose from 1.5 in the 2005-2006 period to 2.3 in the 2015-2016 period.

Moreover, the odds ratio for daily or near-daily use almost tripled for those with versus without depression between the two periods.

“Clinicians should screen their depressed patients for cannabis use, since this is becoming more common and could actually make their depressive symptoms worse rather than better,” senior author Deborah Hasin, PhD, professor of epidemiology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York City, told Medscape Medical News.

The results were published online August 18 in JAMA Network Open.

Misleading advertising

“Cannabis use is increasing in the U.S. and the potency of cannabis products is increasing as well,” Dr. Hasin said.

“Misleading media information and advertising suggests that cannabis is a good treatment for depression, although studies show that cannabis use may actually worsen depression symptoms, [so] we were interested in whether U.S. adults were increasingly likely to be cannabis users if they were depressed,” she reported.

To investigate, the researchers assessed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), with a final study sample consisting of 16,216 U.S. adults. The mean age was 39.12 years, 48.9% were men, 66.4% were non-Hispanic White, 65.6% had at least some college education, and 62.4% had an annual family income of less than $75,000.

Of these participants, 7.5% had “probable depression,” based on the Patient Health Questionnaire–9, the investigators report.

Past-month cannabis use was defined as using cannabis at least once during the past 20 days. Daily or near-daily past-month use was defined as using cannabis at least 20 times in the past 30 days.

Covariates included age, gender, race, education, marital status, annual family income, and past-year use of other substances, such as alcohol, heroin, and methamphetamine.

The researchers note that because the NHANES data were divided into six survey years (2005-2006, 2007-2008, 2009-2010, 2011-2012, 2013-2014, and 2015-2016), their analysis was based on a “new sample weight” that combined the datasets.

Especially pronounced

Results showed that the prevalence of any past-month cannabis use in the overall sample group increased from 12.2% in the 2005-2006 period to 17.3% in the 2015-2016 period (P < .001).

The investigators characterized this change as “significant,” adding that the estimated odds of cannabis use increased by approximately 9% between every 2-year time period.

The change was even more dramatic when the increase was examined across survey time periods (OR, 1.12; P < .001). The estimated odds of daily or near-daily use increased by approximately 12% between every 2-year period.

Interestingly, however, there were no significant changes in odds for depression when consecutive survey years were compared.

When the researchers specifically focused on the association between any past-month cannabis use and depression versus no depression, they found an adjusted OR of 1.90 (95% CI, 1.62-2.12; P < .001).

Individuals with depression also had 2.29 (95% CI, 1.80-2.92) times the odds for daily or near-daily cannabis use, compared with those without depression.

A post-hoc analysis looked at time trends in a sample group that included those missing information on at least one covariate (n = 17,724 participants). It showed similar results to those in the final sample that included no missing data.

People with depression have increased risk of using “most substances that can be abused,” Dr. Hasin said. “However, with the overall rates of cannabis use increasing in the general population, this is becoming especially pronounced for cannabis.”

Clear implications

Commenting on the findings for Medscape Medical News, Deepak D’Souza, MD, professor of psychiatry, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said there is “concern about the unsubstantiated claims of cannabis having a beneficial effect in psychiatric disorders, the most common being depression.”

Dr. D’Souza, who was not involved with the study, called it “yet another piece of evidence suggesting that over the period of time during which cannabis laws have been liberalized, rates of past-month and daily cannabis use have increased, whereas rates of other substances, including alcohol, have remained stable.”

He suggested that a common limitation of epidemiological studies is that it is difficult to tell the direction of the association, “and it could be bidirectional.”

Nevertheless, there are clear implications for the practicing clinician, he added.

“If people have a history of depression, one should ask patients about the use of cannabis and also remind them about potential psychiatric negative effects of use,” Dr. D’Souza noted.

For the general public, “the point is that there is no good evidence to support cannabis use in depression treatment and, in fact, people with depression might be more likely to use it in problematic way,” he said.

Dr. Hasin agreed that it is “certainly possible that the relationship between cannabis use and depression is bidirectional, but the mechanism of this association requires more study.”

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Dr. Hasin and by the New York State Psychiatric Institute. The study authors and Dr. D’Souza disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CDC data confirm mental health is suffering during COVID-19

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to exact a huge toll on mental health in the United States, according to results of a survey released Aug. 13 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During late June, about two in five U.S. adults surveyed said they were struggling with mental health or substance use. Younger adults, racial/ethnic minorities, essential workers, and those with preexisting psychiatric conditions were suffering the most.

“Addressing mental health disparities and preparing support systems to mitigate mental health consequences as the pandemic evolves will continue to be needed urgently,” write Rashon Lane, with the CDC COVID-19 Response Team, and colleagues in an article published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

During the period of June 24-30, 2020, 5,412 U.S. adults aged 18 and older completed online surveys that gauged mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation.

Overall, 40.9% of respondents reported having at least one adverse mental or behavioral health condition; 31% reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder; and 26% reported symptoms of a trauma- and stressor-related disorder related to the pandemic.

The prevalence of symptoms of anxiety disorder alone was roughly three times that reported in the second quarter of 2019, the authors noted.

In addition, , and nearly 11% reported having seriously considered suicide in the preceding 30 days.

Approximately twice as many respondents reported seriously considering suicide in the prior month compared with adults in the United States in 2018 (referring to the previous 12 months), the authors noted.

Suicidal ideation was significantly higher among younger respondents (aged 18-24 years, 26%), Hispanic persons (19%), non-Hispanic Black persons (15%), unpaid caregivers for adults (31%), and essential workers (22%).

The survey results are in line with recent data from Mental Health America, which indicate dramatic increases in depression, anxiety, and suicidality since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The “markedly elevated” prevalence of adverse mental and behavioral health conditions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the “broad impact of the pandemic and the need to prevent and treat these conditions,” the researchers wrote.

The survey also highlights populations at increased risk for psychological distress and unhealthy coping.

“Future studies should identify drivers of adverse mental and behavioral health during the COVID-19 pandemic and whether factors such as social isolation, absence of school structure, unemployment and other financial worries, and various forms of violence (e.g., physical, emotional, mental, or sexual abuse) serve as additional stressors,” they suggested.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to exact a huge toll on mental health in the United States, according to results of a survey released Aug. 13 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During late June, about two in five U.S. adults surveyed said they were struggling with mental health or substance use. Younger adults, racial/ethnic minorities, essential workers, and those with preexisting psychiatric conditions were suffering the most.

“Addressing mental health disparities and preparing support systems to mitigate mental health consequences as the pandemic evolves will continue to be needed urgently,” write Rashon Lane, with the CDC COVID-19 Response Team, and colleagues in an article published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

During the period of June 24-30, 2020, 5,412 U.S. adults aged 18 and older completed online surveys that gauged mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation.

Overall, 40.9% of respondents reported having at least one adverse mental or behavioral health condition; 31% reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder; and 26% reported symptoms of a trauma- and stressor-related disorder related to the pandemic.

The prevalence of symptoms of anxiety disorder alone was roughly three times that reported in the second quarter of 2019, the authors noted.

In addition, , and nearly 11% reported having seriously considered suicide in the preceding 30 days.

Approximately twice as many respondents reported seriously considering suicide in the prior month compared with adults in the United States in 2018 (referring to the previous 12 months), the authors noted.

Suicidal ideation was significantly higher among younger respondents (aged 18-24 years, 26%), Hispanic persons (19%), non-Hispanic Black persons (15%), unpaid caregivers for adults (31%), and essential workers (22%).

The survey results are in line with recent data from Mental Health America, which indicate dramatic increases in depression, anxiety, and suicidality since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The “markedly elevated” prevalence of adverse mental and behavioral health conditions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the “broad impact of the pandemic and the need to prevent and treat these conditions,” the researchers wrote.

The survey also highlights populations at increased risk for psychological distress and unhealthy coping.

“Future studies should identify drivers of adverse mental and behavioral health during the COVID-19 pandemic and whether factors such as social isolation, absence of school structure, unemployment and other financial worries, and various forms of violence (e.g., physical, emotional, mental, or sexual abuse) serve as additional stressors,” they suggested.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to exact a huge toll on mental health in the United States, according to results of a survey released Aug. 13 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During late June, about two in five U.S. adults surveyed said they were struggling with mental health or substance use. Younger adults, racial/ethnic minorities, essential workers, and those with preexisting psychiatric conditions were suffering the most.

“Addressing mental health disparities and preparing support systems to mitigate mental health consequences as the pandemic evolves will continue to be needed urgently,” write Rashon Lane, with the CDC COVID-19 Response Team, and colleagues in an article published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

During the period of June 24-30, 2020, 5,412 U.S. adults aged 18 and older completed online surveys that gauged mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation.

Overall, 40.9% of respondents reported having at least one adverse mental or behavioral health condition; 31% reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder; and 26% reported symptoms of a trauma- and stressor-related disorder related to the pandemic.

The prevalence of symptoms of anxiety disorder alone was roughly three times that reported in the second quarter of 2019, the authors noted.

In addition, , and nearly 11% reported having seriously considered suicide in the preceding 30 days.

Approximately twice as many respondents reported seriously considering suicide in the prior month compared with adults in the United States in 2018 (referring to the previous 12 months), the authors noted.

Suicidal ideation was significantly higher among younger respondents (aged 18-24 years, 26%), Hispanic persons (19%), non-Hispanic Black persons (15%), unpaid caregivers for adults (31%), and essential workers (22%).

The survey results are in line with recent data from Mental Health America, which indicate dramatic increases in depression, anxiety, and suicidality since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The “markedly elevated” prevalence of adverse mental and behavioral health conditions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the “broad impact of the pandemic and the need to prevent and treat these conditions,” the researchers wrote.

The survey also highlights populations at increased risk for psychological distress and unhealthy coping.