User login

Treating major depressive disorder after limited response to an initial agent

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are commonly used first-line agents for treating major depressive disorder. Less than one-half of patients with major depressive disorder experience remission after 1 acute trial of an antidepressant.1 After optimization of an initial agent’s dose and duration, potential next steps include switching agents or augmentation. Augmentation strategies may lead to clinical improvement but carry the risks of polypharmacy, including increased risk of adverse effects and drug interactions. Clinicians can consider the following evidence-based options for a patient with a limited response to an initial SSRI or SNRI.

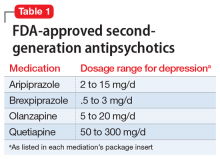

Second-generation antipsychotics, when used as augmentation agents to treat a patient with major depressive disorder, can lead to an approximately 10% improvement in remission rate compared with placebo.2 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, olanzapine (in combination with fluoxetine only), and quetiapine are FDA-approved as adjunctive therapies with an antidepressant (Table 1). Second-generation antipsychotics should be started at lower doses than those used for schizophrenia, and these agents have an increased risk of metabolic adverse effects as well as extrapyramidal symptoms.

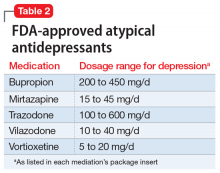

Atypical antidepressants are those that are not classified as an SSRI, SNRI, tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), or monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). These include bupropion, mirtazapine, trazodone, vilazodone, and vortioxetine (Table 2). Bupropion is a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. When used for augmentation in clinical studies, it led to a 30% remission rate.3 Mirtazapine is an alpha-2 antagonist that can be used as monotherapy or in combination with another antidepressant.4 Trazodone is an antidepressant with activity at histamine and alpha-1-adrenergic receptors that is often used off-label for insomnia. Trazodone can be used safely and effectively in combination with other agents for treatment-resistant depression.5 Vilazodone is a 5-HT1A partial agonist, and vortioxetine is a 5-HT1A agonist and 5-HT3 antagonist; both are FDA-approved as alternative agents for monotherapy for major depressive disorder. Choosing among these agents for switching or augmenting can be guided by patient preference, adverse effect profile, and targeting specific symptoms, such as using mirtazapine to address poor sleep and appetite.

Lithium augmentation has been frequently investigated in placebo-controlled, double-blind studies. A meta-analysis showed that patients receiving lithium augmentation with a serum level of ≥0.5 mEq/L were >3 times more likely to respond than those receiving placebo.6 When lithium is used to treat bipolar disorder, the therapeutic serum range for lithium is 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L, with an increased risk of adverse effects (including toxicity) at higher levels.7

Triiodothyronine (T3) augmentation of antidepressants led to remission in approximately 1 in 4 patients who had not achieved remission or who were intolerant to an initial treatment with citalopram and a second switch or augmentation trial.8 In this study, the mean dose of T3 was 45.2 µg/d, with an average length of treatment of 9 weeks.

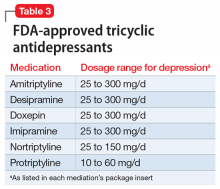

Tricyclic antidepressants are another option when considering switching agents (Table 3). TCAs are additionally effective for comorbid pain conditions.9 When TCAs are used in combination with SSRIs, drug interactions may occur that increase TCA plasma levels. There is also an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when used with serotonergic agents, though an SSRI/ TCA combination may be appropriate for a patient with treatment-resistant depression.10 Additionally, TCAs carry unique risks of cardiovascular effects, including cardiac arrhythmias. A meta-analysis comparing fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline to TCAs (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, and nortriptyline) concluded that both classes had similar efficacy in treating depression, though the drop-out rate was significantly higher among patients receiving TCAs.11

Buspirone is approved for generalized anxiety disorder. In studies where buspirone was used as an augmentation agent for major depressive disorder at a mean daily dose of 40.9 mg divided into 2 doses, it led to a remission rate >30%.3

Continue to: Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

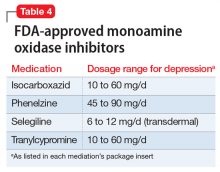

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors should typically be avoided in initial or early treatment of depression due to tolerability issues, drug interactions, and dietary restrictions to avoid hypertensive crisis. MAOIs are generally not recommended to be used with SSRIs, SNRIs, or TCAs, and typically require a “washout” period from other antidepressants (Table 4). One review found that MAOI treatment had advantage over TCA treatment for patients with early-stage treatment-resistant depression, though this advantage decreased as the number of failed antidepressant trials increased.12 One MAOI, selegiline, is available in a transdermal patch, and the 6-mg patch does not require dietary restriction.

Esketamine (intranasal) is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression (failure of response after at least 2 antidepressant trials with adequate dose and duration) in conjunction with an oral antidepressant. In clinical studies, a significant response was noted after 1 week of treatment.13 Esketamine requires an induction period of twice-weekly doses of 56 or 84 mg, with maintenance doses every 1 to 2 weeks. Each dosage administration requires monitoring for at least 2 hours by a health care professional at a certified treatment center. Esketamine’s indication was recently expanded to include treatment of patients with major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation or behavior.

Stimulants such as amphetamines, methylphenidate, or modafinil have been effective in open studies for augmentation in depression.14 However, no stimulant is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression. In addition to other adverse effects, these medications are controlled substances and carry risk of misuse, and their use may not be appropriate for all patients.

1. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

2. Kato M, Chang CM. Augmentation treatments with second-generation antipsychotics to antidepressants in treatment-resistant depression. CNS Drugs. 2013;27 Suppl 1:S11-S19.

3. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

4. Carpenter LL, Jocic Z, Hall JM, et al. Mirtazapine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):45-49.

5. Maes M, Vandoolaeghe E, Desnyder R. Efficacy of treatment with trazodone in combination with pindolol or fluoxetine in major depression. J Affect Disord. 1996;41(3):201-210.

6. Bauer M, Dopfmer S. Lithium augmentation in treatment-resistant depression: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(5):427-434.

7. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

8. Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1519-1530; quiz 1665.

9. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17(4):CD005454.

10. Taylor D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in combination. Interactions and therapeutic uses. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(5):575-580.

11. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ. Are SSRIs better than TCAs? Comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 1997;6(1):10-18.

12. Kim T, Xu C, Amsterdam JD. Relative effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressant versus monoamine oxidase inhibitor monotherapy for treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;250:199-203.

13. Daly EJ, Singh JB, Fedgchin M, et al. Efficacy and safety of intranasal esketamine adjunctive to oral antidepressant therapy in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):139-148.

14. DeBattista C. Augmentation and combination strategies for depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(3 Suppl):11-18.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are commonly used first-line agents for treating major depressive disorder. Less than one-half of patients with major depressive disorder experience remission after 1 acute trial of an antidepressant.1 After optimization of an initial agent’s dose and duration, potential next steps include switching agents or augmentation. Augmentation strategies may lead to clinical improvement but carry the risks of polypharmacy, including increased risk of adverse effects and drug interactions. Clinicians can consider the following evidence-based options for a patient with a limited response to an initial SSRI or SNRI.

Second-generation antipsychotics, when used as augmentation agents to treat a patient with major depressive disorder, can lead to an approximately 10% improvement in remission rate compared with placebo.2 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, olanzapine (in combination with fluoxetine only), and quetiapine are FDA-approved as adjunctive therapies with an antidepressant (Table 1). Second-generation antipsychotics should be started at lower doses than those used for schizophrenia, and these agents have an increased risk of metabolic adverse effects as well as extrapyramidal symptoms.

Atypical antidepressants are those that are not classified as an SSRI, SNRI, tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), or monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). These include bupropion, mirtazapine, trazodone, vilazodone, and vortioxetine (Table 2). Bupropion is a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. When used for augmentation in clinical studies, it led to a 30% remission rate.3 Mirtazapine is an alpha-2 antagonist that can be used as monotherapy or in combination with another antidepressant.4 Trazodone is an antidepressant with activity at histamine and alpha-1-adrenergic receptors that is often used off-label for insomnia. Trazodone can be used safely and effectively in combination with other agents for treatment-resistant depression.5 Vilazodone is a 5-HT1A partial agonist, and vortioxetine is a 5-HT1A agonist and 5-HT3 antagonist; both are FDA-approved as alternative agents for monotherapy for major depressive disorder. Choosing among these agents for switching or augmenting can be guided by patient preference, adverse effect profile, and targeting specific symptoms, such as using mirtazapine to address poor sleep and appetite.

Lithium augmentation has been frequently investigated in placebo-controlled, double-blind studies. A meta-analysis showed that patients receiving lithium augmentation with a serum level of ≥0.5 mEq/L were >3 times more likely to respond than those receiving placebo.6 When lithium is used to treat bipolar disorder, the therapeutic serum range for lithium is 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L, with an increased risk of adverse effects (including toxicity) at higher levels.7

Triiodothyronine (T3) augmentation of antidepressants led to remission in approximately 1 in 4 patients who had not achieved remission or who were intolerant to an initial treatment with citalopram and a second switch or augmentation trial.8 In this study, the mean dose of T3 was 45.2 µg/d, with an average length of treatment of 9 weeks.

Tricyclic antidepressants are another option when considering switching agents (Table 3). TCAs are additionally effective for comorbid pain conditions.9 When TCAs are used in combination with SSRIs, drug interactions may occur that increase TCA plasma levels. There is also an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when used with serotonergic agents, though an SSRI/ TCA combination may be appropriate for a patient with treatment-resistant depression.10 Additionally, TCAs carry unique risks of cardiovascular effects, including cardiac arrhythmias. A meta-analysis comparing fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline to TCAs (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, and nortriptyline) concluded that both classes had similar efficacy in treating depression, though the drop-out rate was significantly higher among patients receiving TCAs.11

Buspirone is approved for generalized anxiety disorder. In studies where buspirone was used as an augmentation agent for major depressive disorder at a mean daily dose of 40.9 mg divided into 2 doses, it led to a remission rate >30%.3

Continue to: Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors should typically be avoided in initial or early treatment of depression due to tolerability issues, drug interactions, and dietary restrictions to avoid hypertensive crisis. MAOIs are generally not recommended to be used with SSRIs, SNRIs, or TCAs, and typically require a “washout” period from other antidepressants (Table 4). One review found that MAOI treatment had advantage over TCA treatment for patients with early-stage treatment-resistant depression, though this advantage decreased as the number of failed antidepressant trials increased.12 One MAOI, selegiline, is available in a transdermal patch, and the 6-mg patch does not require dietary restriction.

Esketamine (intranasal) is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression (failure of response after at least 2 antidepressant trials with adequate dose and duration) in conjunction with an oral antidepressant. In clinical studies, a significant response was noted after 1 week of treatment.13 Esketamine requires an induction period of twice-weekly doses of 56 or 84 mg, with maintenance doses every 1 to 2 weeks. Each dosage administration requires monitoring for at least 2 hours by a health care professional at a certified treatment center. Esketamine’s indication was recently expanded to include treatment of patients with major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation or behavior.

Stimulants such as amphetamines, methylphenidate, or modafinil have been effective in open studies for augmentation in depression.14 However, no stimulant is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression. In addition to other adverse effects, these medications are controlled substances and carry risk of misuse, and their use may not be appropriate for all patients.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are commonly used first-line agents for treating major depressive disorder. Less than one-half of patients with major depressive disorder experience remission after 1 acute trial of an antidepressant.1 After optimization of an initial agent’s dose and duration, potential next steps include switching agents or augmentation. Augmentation strategies may lead to clinical improvement but carry the risks of polypharmacy, including increased risk of adverse effects and drug interactions. Clinicians can consider the following evidence-based options for a patient with a limited response to an initial SSRI or SNRI.

Second-generation antipsychotics, when used as augmentation agents to treat a patient with major depressive disorder, can lead to an approximately 10% improvement in remission rate compared with placebo.2 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, olanzapine (in combination with fluoxetine only), and quetiapine are FDA-approved as adjunctive therapies with an antidepressant (Table 1). Second-generation antipsychotics should be started at lower doses than those used for schizophrenia, and these agents have an increased risk of metabolic adverse effects as well as extrapyramidal symptoms.

Atypical antidepressants are those that are not classified as an SSRI, SNRI, tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), or monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). These include bupropion, mirtazapine, trazodone, vilazodone, and vortioxetine (Table 2). Bupropion is a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. When used for augmentation in clinical studies, it led to a 30% remission rate.3 Mirtazapine is an alpha-2 antagonist that can be used as monotherapy or in combination with another antidepressant.4 Trazodone is an antidepressant with activity at histamine and alpha-1-adrenergic receptors that is often used off-label for insomnia. Trazodone can be used safely and effectively in combination with other agents for treatment-resistant depression.5 Vilazodone is a 5-HT1A partial agonist, and vortioxetine is a 5-HT1A agonist and 5-HT3 antagonist; both are FDA-approved as alternative agents for monotherapy for major depressive disorder. Choosing among these agents for switching or augmenting can be guided by patient preference, adverse effect profile, and targeting specific symptoms, such as using mirtazapine to address poor sleep and appetite.

Lithium augmentation has been frequently investigated in placebo-controlled, double-blind studies. A meta-analysis showed that patients receiving lithium augmentation with a serum level of ≥0.5 mEq/L were >3 times more likely to respond than those receiving placebo.6 When lithium is used to treat bipolar disorder, the therapeutic serum range for lithium is 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L, with an increased risk of adverse effects (including toxicity) at higher levels.7

Triiodothyronine (T3) augmentation of antidepressants led to remission in approximately 1 in 4 patients who had not achieved remission or who were intolerant to an initial treatment with citalopram and a second switch or augmentation trial.8 In this study, the mean dose of T3 was 45.2 µg/d, with an average length of treatment of 9 weeks.

Tricyclic antidepressants are another option when considering switching agents (Table 3). TCAs are additionally effective for comorbid pain conditions.9 When TCAs are used in combination with SSRIs, drug interactions may occur that increase TCA plasma levels. There is also an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when used with serotonergic agents, though an SSRI/ TCA combination may be appropriate for a patient with treatment-resistant depression.10 Additionally, TCAs carry unique risks of cardiovascular effects, including cardiac arrhythmias. A meta-analysis comparing fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline to TCAs (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, and nortriptyline) concluded that both classes had similar efficacy in treating depression, though the drop-out rate was significantly higher among patients receiving TCAs.11

Buspirone is approved for generalized anxiety disorder. In studies where buspirone was used as an augmentation agent for major depressive disorder at a mean daily dose of 40.9 mg divided into 2 doses, it led to a remission rate >30%.3

Continue to: Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors should typically be avoided in initial or early treatment of depression due to tolerability issues, drug interactions, and dietary restrictions to avoid hypertensive crisis. MAOIs are generally not recommended to be used with SSRIs, SNRIs, or TCAs, and typically require a “washout” period from other antidepressants (Table 4). One review found that MAOI treatment had advantage over TCA treatment for patients with early-stage treatment-resistant depression, though this advantage decreased as the number of failed antidepressant trials increased.12 One MAOI, selegiline, is available in a transdermal patch, and the 6-mg patch does not require dietary restriction.

Esketamine (intranasal) is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression (failure of response after at least 2 antidepressant trials with adequate dose and duration) in conjunction with an oral antidepressant. In clinical studies, a significant response was noted after 1 week of treatment.13 Esketamine requires an induction period of twice-weekly doses of 56 or 84 mg, with maintenance doses every 1 to 2 weeks. Each dosage administration requires monitoring for at least 2 hours by a health care professional at a certified treatment center. Esketamine’s indication was recently expanded to include treatment of patients with major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation or behavior.

Stimulants such as amphetamines, methylphenidate, or modafinil have been effective in open studies for augmentation in depression.14 However, no stimulant is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression. In addition to other adverse effects, these medications are controlled substances and carry risk of misuse, and their use may not be appropriate for all patients.

1. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

2. Kato M, Chang CM. Augmentation treatments with second-generation antipsychotics to antidepressants in treatment-resistant depression. CNS Drugs. 2013;27 Suppl 1:S11-S19.

3. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

4. Carpenter LL, Jocic Z, Hall JM, et al. Mirtazapine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):45-49.

5. Maes M, Vandoolaeghe E, Desnyder R. Efficacy of treatment with trazodone in combination with pindolol or fluoxetine in major depression. J Affect Disord. 1996;41(3):201-210.

6. Bauer M, Dopfmer S. Lithium augmentation in treatment-resistant depression: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(5):427-434.

7. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

8. Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1519-1530; quiz 1665.

9. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17(4):CD005454.

10. Taylor D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in combination. Interactions and therapeutic uses. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(5):575-580.

11. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ. Are SSRIs better than TCAs? Comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 1997;6(1):10-18.

12. Kim T, Xu C, Amsterdam JD. Relative effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressant versus monoamine oxidase inhibitor monotherapy for treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;250:199-203.

13. Daly EJ, Singh JB, Fedgchin M, et al. Efficacy and safety of intranasal esketamine adjunctive to oral antidepressant therapy in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):139-148.

14. DeBattista C. Augmentation and combination strategies for depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(3 Suppl):11-18.

1. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

2. Kato M, Chang CM. Augmentation treatments with second-generation antipsychotics to antidepressants in treatment-resistant depression. CNS Drugs. 2013;27 Suppl 1:S11-S19.

3. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

4. Carpenter LL, Jocic Z, Hall JM, et al. Mirtazapine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):45-49.

5. Maes M, Vandoolaeghe E, Desnyder R. Efficacy of treatment with trazodone in combination with pindolol or fluoxetine in major depression. J Affect Disord. 1996;41(3):201-210.

6. Bauer M, Dopfmer S. Lithium augmentation in treatment-resistant depression: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(5):427-434.

7. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

8. Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1519-1530; quiz 1665.

9. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17(4):CD005454.

10. Taylor D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in combination. Interactions and therapeutic uses. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(5):575-580.

11. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ. Are SSRIs better than TCAs? Comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 1997;6(1):10-18.

12. Kim T, Xu C, Amsterdam JD. Relative effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressant versus monoamine oxidase inhibitor monotherapy for treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;250:199-203.

13. Daly EJ, Singh JB, Fedgchin M, et al. Efficacy and safety of intranasal esketamine adjunctive to oral antidepressant therapy in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):139-148.

14. DeBattista C. Augmentation and combination strategies for depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(3 Suppl):11-18.

Nontraditional therapies for treatment-resistant depression

Presently, FDA-approved first-line treatments and standard adjunctive strategies (eg, lithium, thyroid supplementation, stimulants, second-generation antipsychotics) for major depressive disorder (MDD) often produce less-than-desired outcomes while carrying a potentially substantial safety and tolerability burden. The lack of clinically useful and individual-based biomarkers (eg, genetic, neurophysiological, imaging) is a major obstacle to enhancing treatment efficacy and/or decreasing associated adverse effects (AEs). While the discovery of such tools is being aggressively pursued and ultimately will facilitate a more precision-based choice of therapy, empirical strategies remain our primary approach.

In controlled trials, several nontraditional treatments used primarily as adjuncts to standard antidepressants have shown promise. These include “repurposed” (off-label) medications, herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

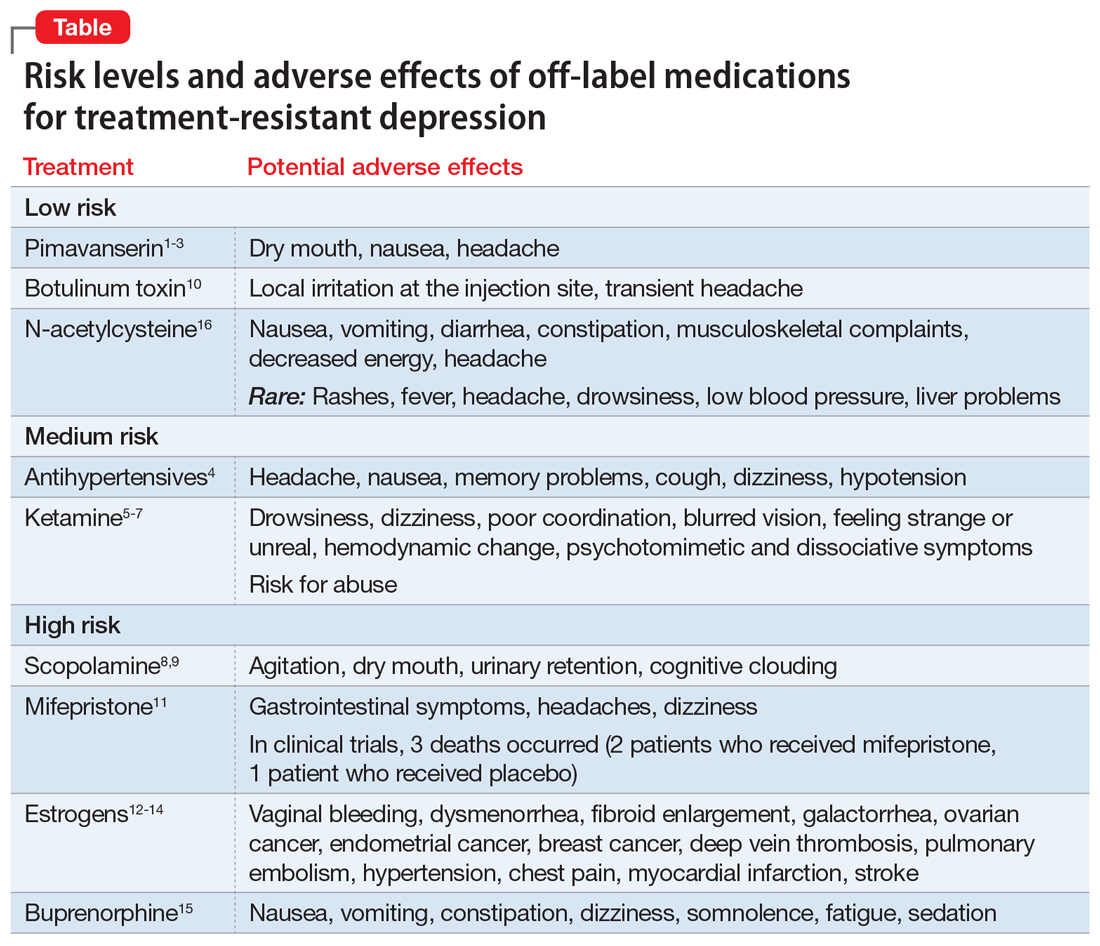

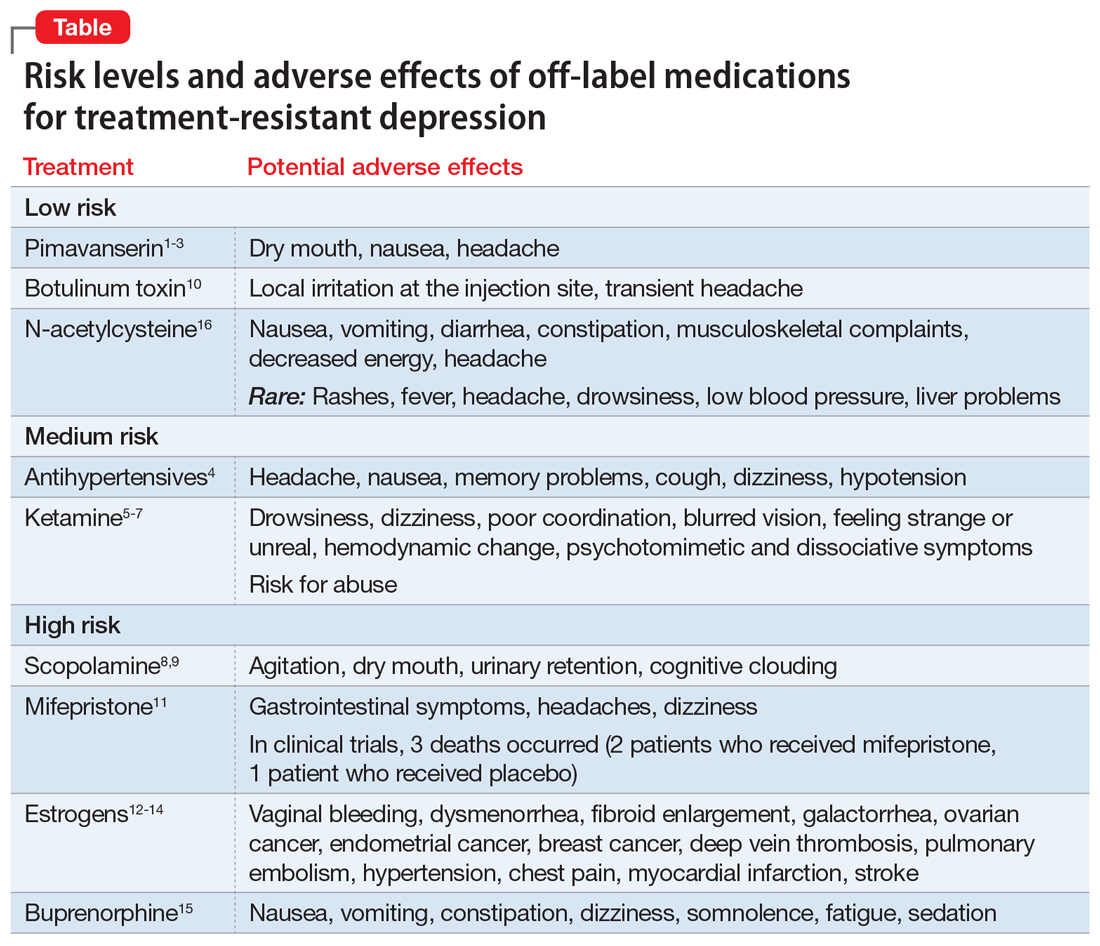

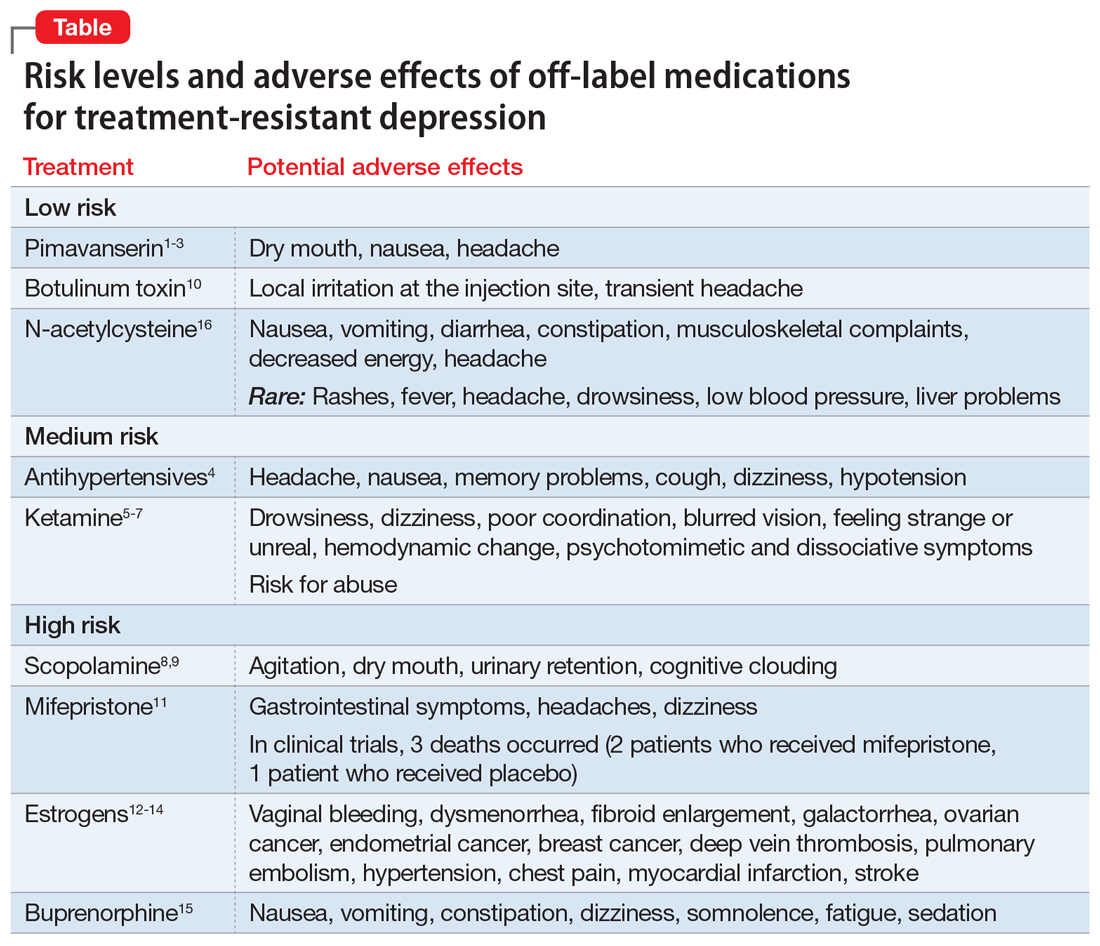

Importantly, some nontraditional treatments also demonstrate AEs (Table1-16). With a careful consideration of the risk/benefit balance, this article reviews some of the better-studied treatment options for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). In Part 1, we will examine off-label medications. In Part 2, we will review other nontraditional approaches to TRD, including herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

We believe this review will help clinicians who need to formulate a different approach after their patient with depression is not helped by traditional first-, second-, and third-line treatments. The potential options discussed in Part 1 of this article are categorized based on their putative mechanism of action (MOA) for depression.

Serotonergic and noradrenergic strategies

Pimavanserin is FDA-approved for treatment of Parkinson’s psychosis. Its potential MOA as an adjunctive strategy for MDD may involve 5-HT2A antagonist and inverse agonist receptor activity, as well as lesser effects at the 5-HT2Creceptor.

A 2-stage, 5-week randomized controlled trial (RCT) (CLARITY; N = 207) found adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) produced a robust antidepressant effect vs placebo in patients whose depression did not respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).1 Furthermore, a secondary analysis of the data suggested that pimavanserin also improved sleepiness (P < .0003) and daily functioning (P < .014) at Week 5.2

Unfortunately, two 6-week, Phase III RCTs (CLARITY-2 and -3; N = 298) did not find a statistically significant difference between active treatment and placebo. This was based on change in the primary outcome measure (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 score) when adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) was added to an SSRI or SNRI in patients with TRD.3 There was, however, a significant difference favoring active treatment over placebo based on the Clinical Global Impression–Severity score.

Continue to: In these trials...

In these trials, pimavanserin was generally well-tolerated. The most common AEs were dry mouth, nausea, and headache. Pimavanserin has minimal activity at norepinephrine, dopamine, histamine, or acetylcholine receptors, thus avoiding AEs associated with these receptor interactions.

Given the mixed efficacy results of existing trials, further studies are needed to clarify this agent’s overall risk/benefit in the context of TRD.

Antihypertensive medications

Emerging data suggest that some beta-adrenergic blockers, angiotensin-inhibiting agents, and calcium antagonists are associated with a decreased incidence of depression. A large 2020 study (N = 3,747,190) used population-based Danish registries (2005 to 2015) to evaluate if any of the 41 most commonly prescribed antihypertensive medications were associated with the diagnosis of depressive disorder or use of antidepressants.4 These researchers found that enalapril, ramipril, amlodipine, propranolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol (P < .001), and verapamil (P < .004) were strongly associated with a decreased risk of depression.4

Adverse effects across these different classes of antihypertensives are well characterized, can be substantial, and commonly are related to their impact on cardiovascular function (eg, hypotension). Clinically, these agents may be potential adjuncts for patients with TRD who need antihypertensive therapy. Their use and the choice of specific agent should only be determined in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician (PCP) or appropriate specialist.

Glutamatergic strategies

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic and analgesic. Its MOA for treating depression appears to occur primarily through antagonist activity at the N-methyl-

Continue to: Many published studies...

Many published studies and reviews have described ketamine’s role for treating MDD. Several studies have reported that low-dose (0.5 mg/kg) IV ketamine infusions can rapidly attenuate severe episodes of MDD as well as associated suicidality. For example, a meta-analysis of 9 RCTs (N = 368) comparing ketamine to placebo for acute treatment of unipolar and bipolar depression reported superior therapeutic effects with active treatment at 24 hours, 72 hours, and 7 days.6 The response and remission rates for ketamine were 52% and 21% at 24 hours; 48% and 24% at 72 hours; and 40% and 26% at 7 days, respectively.6

The most commonly reported AEs during the 4 hours after ketamine infusion included7:

- drowsiness, dizziness, poor coordination

- blurred vision, feeling strange or unreal

- hemodynamic changes (approximately 33%)

- small but significant (P < .05) increases in psychotomimetic and dissociative symptoms.

Because some individuals use ketamine recreationally, this agent also carries the risk of abuse.

Research is ongoing on strategies for long-term maintenance ketamine treatment, and the results of both short- and long-term trials will require careful scrutiny to better assess this agent’s safety and tolerability. Clinicians should first consider esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—because an intranasal formulation of this agent is FDA-approved for treating patients with TRD or MDD with suicidality when administered in a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–certified setting.

Cholinergic strategies

Scopolamine is a potent muscarinic receptor antagonist used to prevent nausea and vomiting caused by motion sickness or medications used during surgery. Its use for MDD is based on the theory that muscarinic receptors may be hypersensitive in mood disorders.

Continue to: Several double-blind RCTs...

Several double-blind RCTs of patients with unipolar or bipolar depression that used 3 pulsed IV infusions (4.0 mcg/kg) over 15 minutes found a rapid, robust antidepressant effect with scopolamine vs placebo.8,9 The oral formulation might also be effective, but would not have a rapid onset.

Common adverse effects of scopolamine include agitation, dry mouth, urinary retention, and cognitive clouding. Given scopolamine’s substantial AE profile, it should be considered only for patients with TRD who could also benefit from the oral formulation for the medical indications noted above, should generally be avoided in older patients, and should be prescribed in consultation with the patient’s PCP.

Botulinum toxin. This neurotoxin inhibits acetylcholine release. It is used to treat disorders characterized by abnormal muscular contraction, such as strabismus, blepharospasm, and chronic pain syndromes. Its MOA for depression may involve its paralytic effects after injection into the glabella forehead muscle (based on the facial feedback hypothesis), as well as modulation of neurotransmitters implicated in the pathophysiology of depression.

In several small trials, injectable botulinum toxin type A (BTA) (29 units) demonstrated antidepressant effects. A recent review that considered 6 trials (N = 235; 4 of the 6 studies were RCTs, 3 of which were rated as high quality) concluded that BTA may be a promising treatment for MDD.10 Limitations of this review included lack of a priori hypotheses, small sample sizes, gender bias, and difficulty in blinding.

In clinical trials, the most common AEs included local irritation at the injection site and transient headache. This agent’s relatively mild AE profile and possible overlap when used for some of the medical indications noted above opens its potential use as an adjunct in patients with comorbid TRD.

Continue to: Endocrine strategies

Endocrine strategies

Mifepristone (RU486). This anti-glucocorticoid receptor antagonist is used as an abortifacient. Based on the theory that hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is implicated in the pathophysiology of MDD with psychotic features (psychotic depression), this agent has been studied as a treatment for this indication.

An analysis of 5 double-blind RCTs (N = 1,460) found that 7 days of mifepristone, 1,200 mg/d, was superior to placebo (P < .004) in reducing psychotic symptoms of depression.11 Plasma concentrations ≥1,600 ng/mL may be required to maximize benefit.11

Overall, this agent demonstrated a good safety profile in clinical trials, with treatment-emergent AEs reported in 556 (66.7%) patients who received mifepristone vs 386 (61.6%) patients who received placebo.11 Common AEs included gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, headache, and dizziness. However, 3 deaths occurred: 2 patients who received mifepristone and 1 patient who received placebo. Given this potential for a fatal outcome, clinicians should first consider prescribing an adjunctive antipsychotic agent or electroconvulsive therapy.

Estrogens. These hormones are important for sexual and reproductive development and are used to treat various sexual/reproductive disorders, primarily in women. Their role in treating depression is based on the observation that perimenopause is accompanied by an increased risk of new and recurrent depression coincident with declining ovarian function.

Evidence supports the antidepressant efficacy of transdermal estradiol plus progesterone for perimenopausal depression, but not for postmenopausal depression.12-14 However, estrogens carry significant risks that must be carefully considered in relationship to their potential benefits. These risks include:

- vaginal bleeding, dysmenorrhea

- fibroid enlargement

- galactorrhea

- ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, breast cancer

- deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism

- hypertension, chest pain, myocardial infarction, stroke.

Continue to: The use of estrogens...

The use of estrogens as an adjunctive therapy for women with treatment-resistant perimenopausal depression should only be undertaken when standard strategies have failed, and in consultation with an endocrine specialist who can monitor for potentially serious AEs.

Opioid medications

Buprenorphine is used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) as well as acute and chronic pain. The opioid system is involved in the regulation of mood and may be an appropriate target for novel antidepressants. The use of buprenorphine in combination with samidorphan (a preferential mu-opioid receptor antagonist) has shown initial promise for TRD while minimizing abuse potential.

Although earlier results were mixed, a pooled analysis of 2 recent large RCTs (N = 760) of patients with MDD who had not responded to antidepressants reported greater reduction in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores from baseline for active treatment (buprenorphine/samidorphan; 2 mg/2 mg) vs placebo at multiple timepoints, including end of treatment (-1.8; P < .010).15

The most common AEs included nausea, constipation, dizziness, vomiting, somnolence, fatigue, and sedation. There was minimal evidence of abuse, dependence, or opioid withdrawal. Due to the opioid crisis in the United States, the resulting relaxation of regulations regarding prescribing buprenorphine, and the high rates of depression among patients with OUD, buprenorphine/samidorphan, which is an investigational agent that is not FDA-approved, may be particularly helpful for patients with OUD who also experience comorbid TRD.

Antioxidant agents

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an amino acid that can treat acetaminophen toxicity and moderate hepatic damage by increasing glutathione levels. Glutathione is also the primary antioxidant in the CNS. NAC may protect against oxidative stress, chelate heavy metals, reduce inflammation, protect against mitochondrial dysfunction, inhibit apoptosis, and enhance neurogenesis, all potential pathophysiological processes that may contribute to depression.16

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (N = 574) considered patients with various depression diagnoses who were randomized to adjunctive NAC, 1,000 mg twice a day, or placebo. Over 12 to 24 weeks, there was a significantly greater improvement in mood symptoms and functionality with NAC vs placebo.16

Overall, NAC was well-tolerated. The most common AEs were GI symptoms, musculoskeletal complaints, decreased energy, and headache. While NAC has been touted as a potential adjunct therapy for several psychiatric disorders, including TRD, the evidence for benefit remains limited. Given its favorable AE profile, however, and over-the-counter availability, it remains an option for select patients. It is important to ask patients if they are already taking NAC.

Options beyond off-label medications

There are a multitude of options available for addressing TRD. Many FDA-approved medications are repurposed and prescribed off-label for other indications when the risk/benefit balance is favorable. In Part 1 of this article, we reviewed several off-label medications that have supportive controlled data for treating TRD. In Part 2, we will review other nontraditional therapies for TRD, including herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

Bottom Line

Off-label medications that may offer benefit for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) include pimavanserin, antihypertensive agents, ketamine, scopolamine, botulinum toxin, mifepristone, estrogens, buprenorphine, and N-acetylcysteine. Although some evidence supports use of these agents as adjuncts for TRD, an individualized risk/benefit analysis is required.

Related Resource

- Joshi KG, Frierson RL. Off-label prescribing: How to limit your liability. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):12,39.

Drug Brand Names

Amlodipine • Katerzia, Norvasc

Atenolol • Tenormin

Bisoprolol • Zebeta

Buprenorphine • Sublocade, Subutex

Carvedilol • Coreg

Enalapril • Vasotec

Esketamine • Spravato

Estradiol transdermal • Estraderm

Ketamine • Ketalar

Mifepristone • Mifeprex

Pimavanserin • Nuplazid

Progesterone • Prometrium

Propranolol • Inderal

Ramipril • Altace

Verapamil • Calan, Verelan

1. Fava M, Dirks B, Freeman M, et al. A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adjunctive pimavanserin in patients with major depressive disorder and an inadequate response to therapy (CLARITY). J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(6):19m12928.

2. Jha MK, Fava M, Freeman MP, et al. Effect of adjunctive pimavanserin on sleep/wakefulness in patients with major depressive disorder: secondary analysis from CLARITY. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;82(1):20m13425.

3. ACADIA Pharmaceuticals announces top-line results from the Phase 3 CLARITY study evaluating pimavanserin for the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder. News release. Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc. Published July 20, 2020. https://ir.acadia-pharm.com/news-releases/news-release-details/acadia-pharmaceuticals-announces-top-line-results-phase-3-0

4. Kessing LV, Rytgaard HC, Ekstrom CT, et al. Antihypertensive drugs and risk of depression: a nationwide population-based study. Hypertension. 2020;76(4):1263-1279.

5. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

6. Han Y, Chen J, Zou D, et al. Efficacy of ketamine in the rapid treatment of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2859-2867.

7. Wan LB, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):247-252.

8. Hasselmann, H. Scopolamine and depression: a role for muscarinic antagonism? CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13(4):673-683.

9. Drevets WC, Zarate CA Jr, Furey ML. Antidepressant effects of the muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist scopolamine: a review. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1156-1163.

10. Stearns TP, Shad MU, Guzman GC. Glabellar botulinum toxin injections in major depressive disorder: a critical review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5): 18r02298.

11. Block TS, Kushner H, Kalin N, et al. Combined analysis of mifepristone for psychotic depression: plasma levels associated with clinical response. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(1):46-54.

12. Rubinow DR, Johnson SL, Schmidt PJ, et al. Efficacy of estradiol in perimenopausal depression: so much promise and so few answers. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(8):539-549.

13. Schmidt PJ, Ben Dor R, Martinez PE, et al. Effects of estradiol withdrawal on mood in women with past perimenopausal depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(7):714-726.

14. Gordon JL, Rubinow DR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, et al. Efficacy of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone in the prevention of depressive symptoms in the menopause transition: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):149-157.

15. Fava M, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, et al. Opioid system modulation with buprenorphine/samidorphan combination for major depressive disorder: two randomized controlled studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1580-1591.

16. Fernandes BS, Dean OM, Dodd S, et al. N-Acetylcysteine in depressive symptoms and functionality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(4):e457-466.

Presently, FDA-approved first-line treatments and standard adjunctive strategies (eg, lithium, thyroid supplementation, stimulants, second-generation antipsychotics) for major depressive disorder (MDD) often produce less-than-desired outcomes while carrying a potentially substantial safety and tolerability burden. The lack of clinically useful and individual-based biomarkers (eg, genetic, neurophysiological, imaging) is a major obstacle to enhancing treatment efficacy and/or decreasing associated adverse effects (AEs). While the discovery of such tools is being aggressively pursued and ultimately will facilitate a more precision-based choice of therapy, empirical strategies remain our primary approach.

In controlled trials, several nontraditional treatments used primarily as adjuncts to standard antidepressants have shown promise. These include “repurposed” (off-label) medications, herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

Importantly, some nontraditional treatments also demonstrate AEs (Table1-16). With a careful consideration of the risk/benefit balance, this article reviews some of the better-studied treatment options for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). In Part 1, we will examine off-label medications. In Part 2, we will review other nontraditional approaches to TRD, including herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

We believe this review will help clinicians who need to formulate a different approach after their patient with depression is not helped by traditional first-, second-, and third-line treatments. The potential options discussed in Part 1 of this article are categorized based on their putative mechanism of action (MOA) for depression.

Serotonergic and noradrenergic strategies

Pimavanserin is FDA-approved for treatment of Parkinson’s psychosis. Its potential MOA as an adjunctive strategy for MDD may involve 5-HT2A antagonist and inverse agonist receptor activity, as well as lesser effects at the 5-HT2Creceptor.

A 2-stage, 5-week randomized controlled trial (RCT) (CLARITY; N = 207) found adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) produced a robust antidepressant effect vs placebo in patients whose depression did not respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).1 Furthermore, a secondary analysis of the data suggested that pimavanserin also improved sleepiness (P < .0003) and daily functioning (P < .014) at Week 5.2

Unfortunately, two 6-week, Phase III RCTs (CLARITY-2 and -3; N = 298) did not find a statistically significant difference between active treatment and placebo. This was based on change in the primary outcome measure (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 score) when adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) was added to an SSRI or SNRI in patients with TRD.3 There was, however, a significant difference favoring active treatment over placebo based on the Clinical Global Impression–Severity score.

Continue to: In these trials...

In these trials, pimavanserin was generally well-tolerated. The most common AEs were dry mouth, nausea, and headache. Pimavanserin has minimal activity at norepinephrine, dopamine, histamine, or acetylcholine receptors, thus avoiding AEs associated with these receptor interactions.

Given the mixed efficacy results of existing trials, further studies are needed to clarify this agent’s overall risk/benefit in the context of TRD.

Antihypertensive medications

Emerging data suggest that some beta-adrenergic blockers, angiotensin-inhibiting agents, and calcium antagonists are associated with a decreased incidence of depression. A large 2020 study (N = 3,747,190) used population-based Danish registries (2005 to 2015) to evaluate if any of the 41 most commonly prescribed antihypertensive medications were associated with the diagnosis of depressive disorder or use of antidepressants.4 These researchers found that enalapril, ramipril, amlodipine, propranolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol (P < .001), and verapamil (P < .004) were strongly associated with a decreased risk of depression.4

Adverse effects across these different classes of antihypertensives are well characterized, can be substantial, and commonly are related to their impact on cardiovascular function (eg, hypotension). Clinically, these agents may be potential adjuncts for patients with TRD who need antihypertensive therapy. Their use and the choice of specific agent should only be determined in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician (PCP) or appropriate specialist.

Glutamatergic strategies

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic and analgesic. Its MOA for treating depression appears to occur primarily through antagonist activity at the N-methyl-

Continue to: Many published studies...

Many published studies and reviews have described ketamine’s role for treating MDD. Several studies have reported that low-dose (0.5 mg/kg) IV ketamine infusions can rapidly attenuate severe episodes of MDD as well as associated suicidality. For example, a meta-analysis of 9 RCTs (N = 368) comparing ketamine to placebo for acute treatment of unipolar and bipolar depression reported superior therapeutic effects with active treatment at 24 hours, 72 hours, and 7 days.6 The response and remission rates for ketamine were 52% and 21% at 24 hours; 48% and 24% at 72 hours; and 40% and 26% at 7 days, respectively.6

The most commonly reported AEs during the 4 hours after ketamine infusion included7:

- drowsiness, dizziness, poor coordination

- blurred vision, feeling strange or unreal

- hemodynamic changes (approximately 33%)

- small but significant (P < .05) increases in psychotomimetic and dissociative symptoms.

Because some individuals use ketamine recreationally, this agent also carries the risk of abuse.

Research is ongoing on strategies for long-term maintenance ketamine treatment, and the results of both short- and long-term trials will require careful scrutiny to better assess this agent’s safety and tolerability. Clinicians should first consider esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—because an intranasal formulation of this agent is FDA-approved for treating patients with TRD or MDD with suicidality when administered in a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–certified setting.

Cholinergic strategies

Scopolamine is a potent muscarinic receptor antagonist used to prevent nausea and vomiting caused by motion sickness or medications used during surgery. Its use for MDD is based on the theory that muscarinic receptors may be hypersensitive in mood disorders.

Continue to: Several double-blind RCTs...

Several double-blind RCTs of patients with unipolar or bipolar depression that used 3 pulsed IV infusions (4.0 mcg/kg) over 15 minutes found a rapid, robust antidepressant effect with scopolamine vs placebo.8,9 The oral formulation might also be effective, but would not have a rapid onset.

Common adverse effects of scopolamine include agitation, dry mouth, urinary retention, and cognitive clouding. Given scopolamine’s substantial AE profile, it should be considered only for patients with TRD who could also benefit from the oral formulation for the medical indications noted above, should generally be avoided in older patients, and should be prescribed in consultation with the patient’s PCP.

Botulinum toxin. This neurotoxin inhibits acetylcholine release. It is used to treat disorders characterized by abnormal muscular contraction, such as strabismus, blepharospasm, and chronic pain syndromes. Its MOA for depression may involve its paralytic effects after injection into the glabella forehead muscle (based on the facial feedback hypothesis), as well as modulation of neurotransmitters implicated in the pathophysiology of depression.

In several small trials, injectable botulinum toxin type A (BTA) (29 units) demonstrated antidepressant effects. A recent review that considered 6 trials (N = 235; 4 of the 6 studies were RCTs, 3 of which were rated as high quality) concluded that BTA may be a promising treatment for MDD.10 Limitations of this review included lack of a priori hypotheses, small sample sizes, gender bias, and difficulty in blinding.

In clinical trials, the most common AEs included local irritation at the injection site and transient headache. This agent’s relatively mild AE profile and possible overlap when used for some of the medical indications noted above opens its potential use as an adjunct in patients with comorbid TRD.

Continue to: Endocrine strategies

Endocrine strategies

Mifepristone (RU486). This anti-glucocorticoid receptor antagonist is used as an abortifacient. Based on the theory that hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is implicated in the pathophysiology of MDD with psychotic features (psychotic depression), this agent has been studied as a treatment for this indication.

An analysis of 5 double-blind RCTs (N = 1,460) found that 7 days of mifepristone, 1,200 mg/d, was superior to placebo (P < .004) in reducing psychotic symptoms of depression.11 Plasma concentrations ≥1,600 ng/mL may be required to maximize benefit.11

Overall, this agent demonstrated a good safety profile in clinical trials, with treatment-emergent AEs reported in 556 (66.7%) patients who received mifepristone vs 386 (61.6%) patients who received placebo.11 Common AEs included gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, headache, and dizziness. However, 3 deaths occurred: 2 patients who received mifepristone and 1 patient who received placebo. Given this potential for a fatal outcome, clinicians should first consider prescribing an adjunctive antipsychotic agent or electroconvulsive therapy.

Estrogens. These hormones are important for sexual and reproductive development and are used to treat various sexual/reproductive disorders, primarily in women. Their role in treating depression is based on the observation that perimenopause is accompanied by an increased risk of new and recurrent depression coincident with declining ovarian function.

Evidence supports the antidepressant efficacy of transdermal estradiol plus progesterone for perimenopausal depression, but not for postmenopausal depression.12-14 However, estrogens carry significant risks that must be carefully considered in relationship to their potential benefits. These risks include:

- vaginal bleeding, dysmenorrhea

- fibroid enlargement

- galactorrhea

- ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, breast cancer

- deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism

- hypertension, chest pain, myocardial infarction, stroke.

Continue to: The use of estrogens...

The use of estrogens as an adjunctive therapy for women with treatment-resistant perimenopausal depression should only be undertaken when standard strategies have failed, and in consultation with an endocrine specialist who can monitor for potentially serious AEs.

Opioid medications

Buprenorphine is used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) as well as acute and chronic pain. The opioid system is involved in the regulation of mood and may be an appropriate target for novel antidepressants. The use of buprenorphine in combination with samidorphan (a preferential mu-opioid receptor antagonist) has shown initial promise for TRD while minimizing abuse potential.

Although earlier results were mixed, a pooled analysis of 2 recent large RCTs (N = 760) of patients with MDD who had not responded to antidepressants reported greater reduction in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores from baseline for active treatment (buprenorphine/samidorphan; 2 mg/2 mg) vs placebo at multiple timepoints, including end of treatment (-1.8; P < .010).15

The most common AEs included nausea, constipation, dizziness, vomiting, somnolence, fatigue, and sedation. There was minimal evidence of abuse, dependence, or opioid withdrawal. Due to the opioid crisis in the United States, the resulting relaxation of regulations regarding prescribing buprenorphine, and the high rates of depression among patients with OUD, buprenorphine/samidorphan, which is an investigational agent that is not FDA-approved, may be particularly helpful for patients with OUD who also experience comorbid TRD.

Antioxidant agents

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an amino acid that can treat acetaminophen toxicity and moderate hepatic damage by increasing glutathione levels. Glutathione is also the primary antioxidant in the CNS. NAC may protect against oxidative stress, chelate heavy metals, reduce inflammation, protect against mitochondrial dysfunction, inhibit apoptosis, and enhance neurogenesis, all potential pathophysiological processes that may contribute to depression.16

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (N = 574) considered patients with various depression diagnoses who were randomized to adjunctive NAC, 1,000 mg twice a day, or placebo. Over 12 to 24 weeks, there was a significantly greater improvement in mood symptoms and functionality with NAC vs placebo.16

Overall, NAC was well-tolerated. The most common AEs were GI symptoms, musculoskeletal complaints, decreased energy, and headache. While NAC has been touted as a potential adjunct therapy for several psychiatric disorders, including TRD, the evidence for benefit remains limited. Given its favorable AE profile, however, and over-the-counter availability, it remains an option for select patients. It is important to ask patients if they are already taking NAC.

Options beyond off-label medications

There are a multitude of options available for addressing TRD. Many FDA-approved medications are repurposed and prescribed off-label for other indications when the risk/benefit balance is favorable. In Part 1 of this article, we reviewed several off-label medications that have supportive controlled data for treating TRD. In Part 2, we will review other nontraditional therapies for TRD, including herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

Bottom Line

Off-label medications that may offer benefit for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) include pimavanserin, antihypertensive agents, ketamine, scopolamine, botulinum toxin, mifepristone, estrogens, buprenorphine, and N-acetylcysteine. Although some evidence supports use of these agents as adjuncts for TRD, an individualized risk/benefit analysis is required.

Related Resource

- Joshi KG, Frierson RL. Off-label prescribing: How to limit your liability. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):12,39.

Drug Brand Names

Amlodipine • Katerzia, Norvasc

Atenolol • Tenormin

Bisoprolol • Zebeta

Buprenorphine • Sublocade, Subutex

Carvedilol • Coreg

Enalapril • Vasotec

Esketamine • Spravato

Estradiol transdermal • Estraderm

Ketamine • Ketalar

Mifepristone • Mifeprex

Pimavanserin • Nuplazid

Progesterone • Prometrium

Propranolol • Inderal

Ramipril • Altace

Verapamil • Calan, Verelan

Presently, FDA-approved first-line treatments and standard adjunctive strategies (eg, lithium, thyroid supplementation, stimulants, second-generation antipsychotics) for major depressive disorder (MDD) often produce less-than-desired outcomes while carrying a potentially substantial safety and tolerability burden. The lack of clinically useful and individual-based biomarkers (eg, genetic, neurophysiological, imaging) is a major obstacle to enhancing treatment efficacy and/or decreasing associated adverse effects (AEs). While the discovery of such tools is being aggressively pursued and ultimately will facilitate a more precision-based choice of therapy, empirical strategies remain our primary approach.

In controlled trials, several nontraditional treatments used primarily as adjuncts to standard antidepressants have shown promise. These include “repurposed” (off-label) medications, herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

Importantly, some nontraditional treatments also demonstrate AEs (Table1-16). With a careful consideration of the risk/benefit balance, this article reviews some of the better-studied treatment options for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). In Part 1, we will examine off-label medications. In Part 2, we will review other nontraditional approaches to TRD, including herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

We believe this review will help clinicians who need to formulate a different approach after their patient with depression is not helped by traditional first-, second-, and third-line treatments. The potential options discussed in Part 1 of this article are categorized based on their putative mechanism of action (MOA) for depression.

Serotonergic and noradrenergic strategies

Pimavanserin is FDA-approved for treatment of Parkinson’s psychosis. Its potential MOA as an adjunctive strategy for MDD may involve 5-HT2A antagonist and inverse agonist receptor activity, as well as lesser effects at the 5-HT2Creceptor.

A 2-stage, 5-week randomized controlled trial (RCT) (CLARITY; N = 207) found adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) produced a robust antidepressant effect vs placebo in patients whose depression did not respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).1 Furthermore, a secondary analysis of the data suggested that pimavanserin also improved sleepiness (P < .0003) and daily functioning (P < .014) at Week 5.2

Unfortunately, two 6-week, Phase III RCTs (CLARITY-2 and -3; N = 298) did not find a statistically significant difference between active treatment and placebo. This was based on change in the primary outcome measure (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 score) when adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) was added to an SSRI or SNRI in patients with TRD.3 There was, however, a significant difference favoring active treatment over placebo based on the Clinical Global Impression–Severity score.

Continue to: In these trials...

In these trials, pimavanserin was generally well-tolerated. The most common AEs were dry mouth, nausea, and headache. Pimavanserin has minimal activity at norepinephrine, dopamine, histamine, or acetylcholine receptors, thus avoiding AEs associated with these receptor interactions.

Given the mixed efficacy results of existing trials, further studies are needed to clarify this agent’s overall risk/benefit in the context of TRD.

Antihypertensive medications

Emerging data suggest that some beta-adrenergic blockers, angiotensin-inhibiting agents, and calcium antagonists are associated with a decreased incidence of depression. A large 2020 study (N = 3,747,190) used population-based Danish registries (2005 to 2015) to evaluate if any of the 41 most commonly prescribed antihypertensive medications were associated with the diagnosis of depressive disorder or use of antidepressants.4 These researchers found that enalapril, ramipril, amlodipine, propranolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol (P < .001), and verapamil (P < .004) were strongly associated with a decreased risk of depression.4

Adverse effects across these different classes of antihypertensives are well characterized, can be substantial, and commonly are related to their impact on cardiovascular function (eg, hypotension). Clinically, these agents may be potential adjuncts for patients with TRD who need antihypertensive therapy. Their use and the choice of specific agent should only be determined in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician (PCP) or appropriate specialist.

Glutamatergic strategies

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic and analgesic. Its MOA for treating depression appears to occur primarily through antagonist activity at the N-methyl-

Continue to: Many published studies...

Many published studies and reviews have described ketamine’s role for treating MDD. Several studies have reported that low-dose (0.5 mg/kg) IV ketamine infusions can rapidly attenuate severe episodes of MDD as well as associated suicidality. For example, a meta-analysis of 9 RCTs (N = 368) comparing ketamine to placebo for acute treatment of unipolar and bipolar depression reported superior therapeutic effects with active treatment at 24 hours, 72 hours, and 7 days.6 The response and remission rates for ketamine were 52% and 21% at 24 hours; 48% and 24% at 72 hours; and 40% and 26% at 7 days, respectively.6

The most commonly reported AEs during the 4 hours after ketamine infusion included7:

- drowsiness, dizziness, poor coordination

- blurred vision, feeling strange or unreal

- hemodynamic changes (approximately 33%)

- small but significant (P < .05) increases in psychotomimetic and dissociative symptoms.

Because some individuals use ketamine recreationally, this agent also carries the risk of abuse.

Research is ongoing on strategies for long-term maintenance ketamine treatment, and the results of both short- and long-term trials will require careful scrutiny to better assess this agent’s safety and tolerability. Clinicians should first consider esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—because an intranasal formulation of this agent is FDA-approved for treating patients with TRD or MDD with suicidality when administered in a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–certified setting.

Cholinergic strategies

Scopolamine is a potent muscarinic receptor antagonist used to prevent nausea and vomiting caused by motion sickness or medications used during surgery. Its use for MDD is based on the theory that muscarinic receptors may be hypersensitive in mood disorders.

Continue to: Several double-blind RCTs...

Several double-blind RCTs of patients with unipolar or bipolar depression that used 3 pulsed IV infusions (4.0 mcg/kg) over 15 minutes found a rapid, robust antidepressant effect with scopolamine vs placebo.8,9 The oral formulation might also be effective, but would not have a rapid onset.

Common adverse effects of scopolamine include agitation, dry mouth, urinary retention, and cognitive clouding. Given scopolamine’s substantial AE profile, it should be considered only for patients with TRD who could also benefit from the oral formulation for the medical indications noted above, should generally be avoided in older patients, and should be prescribed in consultation with the patient’s PCP.

Botulinum toxin. This neurotoxin inhibits acetylcholine release. It is used to treat disorders characterized by abnormal muscular contraction, such as strabismus, blepharospasm, and chronic pain syndromes. Its MOA for depression may involve its paralytic effects after injection into the glabella forehead muscle (based on the facial feedback hypothesis), as well as modulation of neurotransmitters implicated in the pathophysiology of depression.

In several small trials, injectable botulinum toxin type A (BTA) (29 units) demonstrated antidepressant effects. A recent review that considered 6 trials (N = 235; 4 of the 6 studies were RCTs, 3 of which were rated as high quality) concluded that BTA may be a promising treatment for MDD.10 Limitations of this review included lack of a priori hypotheses, small sample sizes, gender bias, and difficulty in blinding.

In clinical trials, the most common AEs included local irritation at the injection site and transient headache. This agent’s relatively mild AE profile and possible overlap when used for some of the medical indications noted above opens its potential use as an adjunct in patients with comorbid TRD.

Continue to: Endocrine strategies

Endocrine strategies

Mifepristone (RU486). This anti-glucocorticoid receptor antagonist is used as an abortifacient. Based on the theory that hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is implicated in the pathophysiology of MDD with psychotic features (psychotic depression), this agent has been studied as a treatment for this indication.

An analysis of 5 double-blind RCTs (N = 1,460) found that 7 days of mifepristone, 1,200 mg/d, was superior to placebo (P < .004) in reducing psychotic symptoms of depression.11 Plasma concentrations ≥1,600 ng/mL may be required to maximize benefit.11

Overall, this agent demonstrated a good safety profile in clinical trials, with treatment-emergent AEs reported in 556 (66.7%) patients who received mifepristone vs 386 (61.6%) patients who received placebo.11 Common AEs included gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, headache, and dizziness. However, 3 deaths occurred: 2 patients who received mifepristone and 1 patient who received placebo. Given this potential for a fatal outcome, clinicians should first consider prescribing an adjunctive antipsychotic agent or electroconvulsive therapy.

Estrogens. These hormones are important for sexual and reproductive development and are used to treat various sexual/reproductive disorders, primarily in women. Their role in treating depression is based on the observation that perimenopause is accompanied by an increased risk of new and recurrent depression coincident with declining ovarian function.

Evidence supports the antidepressant efficacy of transdermal estradiol plus progesterone for perimenopausal depression, but not for postmenopausal depression.12-14 However, estrogens carry significant risks that must be carefully considered in relationship to their potential benefits. These risks include:

- vaginal bleeding, dysmenorrhea

- fibroid enlargement

- galactorrhea

- ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, breast cancer

- deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism

- hypertension, chest pain, myocardial infarction, stroke.

Continue to: The use of estrogens...

The use of estrogens as an adjunctive therapy for women with treatment-resistant perimenopausal depression should only be undertaken when standard strategies have failed, and in consultation with an endocrine specialist who can monitor for potentially serious AEs.

Opioid medications

Buprenorphine is used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) as well as acute and chronic pain. The opioid system is involved in the regulation of mood and may be an appropriate target for novel antidepressants. The use of buprenorphine in combination with samidorphan (a preferential mu-opioid receptor antagonist) has shown initial promise for TRD while minimizing abuse potential.

Although earlier results were mixed, a pooled analysis of 2 recent large RCTs (N = 760) of patients with MDD who had not responded to antidepressants reported greater reduction in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores from baseline for active treatment (buprenorphine/samidorphan; 2 mg/2 mg) vs placebo at multiple timepoints, including end of treatment (-1.8; P < .010).15

The most common AEs included nausea, constipation, dizziness, vomiting, somnolence, fatigue, and sedation. There was minimal evidence of abuse, dependence, or opioid withdrawal. Due to the opioid crisis in the United States, the resulting relaxation of regulations regarding prescribing buprenorphine, and the high rates of depression among patients with OUD, buprenorphine/samidorphan, which is an investigational agent that is not FDA-approved, may be particularly helpful for patients with OUD who also experience comorbid TRD.

Antioxidant agents

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an amino acid that can treat acetaminophen toxicity and moderate hepatic damage by increasing glutathione levels. Glutathione is also the primary antioxidant in the CNS. NAC may protect against oxidative stress, chelate heavy metals, reduce inflammation, protect against mitochondrial dysfunction, inhibit apoptosis, and enhance neurogenesis, all potential pathophysiological processes that may contribute to depression.16

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (N = 574) considered patients with various depression diagnoses who were randomized to adjunctive NAC, 1,000 mg twice a day, or placebo. Over 12 to 24 weeks, there was a significantly greater improvement in mood symptoms and functionality with NAC vs placebo.16

Overall, NAC was well-tolerated. The most common AEs were GI symptoms, musculoskeletal complaints, decreased energy, and headache. While NAC has been touted as a potential adjunct therapy for several psychiatric disorders, including TRD, the evidence for benefit remains limited. Given its favorable AE profile, however, and over-the-counter availability, it remains an option for select patients. It is important to ask patients if they are already taking NAC.

Options beyond off-label medications

There are a multitude of options available for addressing TRD. Many FDA-approved medications are repurposed and prescribed off-label for other indications when the risk/benefit balance is favorable. In Part 1 of this article, we reviewed several off-label medications that have supportive controlled data for treating TRD. In Part 2, we will review other nontraditional therapies for TRD, including herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

Bottom Line

Off-label medications that may offer benefit for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) include pimavanserin, antihypertensive agents, ketamine, scopolamine, botulinum toxin, mifepristone, estrogens, buprenorphine, and N-acetylcysteine. Although some evidence supports use of these agents as adjuncts for TRD, an individualized risk/benefit analysis is required.

Related Resource

- Joshi KG, Frierson RL. Off-label prescribing: How to limit your liability. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):12,39.

Drug Brand Names

Amlodipine • Katerzia, Norvasc

Atenolol • Tenormin

Bisoprolol • Zebeta

Buprenorphine • Sublocade, Subutex

Carvedilol • Coreg

Enalapril • Vasotec

Esketamine • Spravato

Estradiol transdermal • Estraderm

Ketamine • Ketalar

Mifepristone • Mifeprex

Pimavanserin • Nuplazid

Progesterone • Prometrium

Propranolol • Inderal

Ramipril • Altace

Verapamil • Calan, Verelan

1. Fava M, Dirks B, Freeman M, et al. A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adjunctive pimavanserin in patients with major depressive disorder and an inadequate response to therapy (CLARITY). J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(6):19m12928.

2. Jha MK, Fava M, Freeman MP, et al. Effect of adjunctive pimavanserin on sleep/wakefulness in patients with major depressive disorder: secondary analysis from CLARITY. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;82(1):20m13425.

3. ACADIA Pharmaceuticals announces top-line results from the Phase 3 CLARITY study evaluating pimavanserin for the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder. News release. Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc. Published July 20, 2020. https://ir.acadia-pharm.com/news-releases/news-release-details/acadia-pharmaceuticals-announces-top-line-results-phase-3-0

4. Kessing LV, Rytgaard HC, Ekstrom CT, et al. Antihypertensive drugs and risk of depression: a nationwide population-based study. Hypertension. 2020;76(4):1263-1279.

5. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

6. Han Y, Chen J, Zou D, et al. Efficacy of ketamine in the rapid treatment of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2859-2867.

7. Wan LB, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):247-252.

8. Hasselmann, H. Scopolamine and depression: a role for muscarinic antagonism? CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13(4):673-683.

9. Drevets WC, Zarate CA Jr, Furey ML. Antidepressant effects of the muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist scopolamine: a review. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1156-1163.

10. Stearns TP, Shad MU, Guzman GC. Glabellar botulinum toxin injections in major depressive disorder: a critical review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5): 18r02298.

11. Block TS, Kushner H, Kalin N, et al. Combined analysis of mifepristone for psychotic depression: plasma levels associated with clinical response. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(1):46-54.

12. Rubinow DR, Johnson SL, Schmidt PJ, et al. Efficacy of estradiol in perimenopausal depression: so much promise and so few answers. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(8):539-549.

13. Schmidt PJ, Ben Dor R, Martinez PE, et al. Effects of estradiol withdrawal on mood in women with past perimenopausal depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(7):714-726.

14. Gordon JL, Rubinow DR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, et al. Efficacy of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone in the prevention of depressive symptoms in the menopause transition: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):149-157.

15. Fava M, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, et al. Opioid system modulation with buprenorphine/samidorphan combination for major depressive disorder: two randomized controlled studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1580-1591.

16. Fernandes BS, Dean OM, Dodd S, et al. N-Acetylcysteine in depressive symptoms and functionality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(4):e457-466.

1. Fava M, Dirks B, Freeman M, et al. A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adjunctive pimavanserin in patients with major depressive disorder and an inadequate response to therapy (CLARITY). J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(6):19m12928.