User login

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are commonly used first-line agents for treating major depressive disorder. Less than one-half of patients with major depressive disorder experience remission after 1 acute trial of an antidepressant.1 After optimization of an initial agent’s dose and duration, potential next steps include switching agents or augmentation. Augmentation strategies may lead to clinical improvement but carry the risks of polypharmacy, including increased risk of adverse effects and drug interactions. Clinicians can consider the following evidence-based options for a patient with a limited response to an initial SSRI or SNRI.

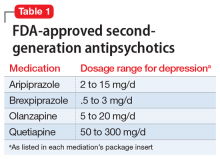

Second-generation antipsychotics, when used as augmentation agents to treat a patient with major depressive disorder, can lead to an approximately 10% improvement in remission rate compared with placebo.2 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, olanzapine (in combination with fluoxetine only), and quetiapine are FDA-approved as adjunctive therapies with an antidepressant (Table 1). Second-generation antipsychotics should be started at lower doses than those used for schizophrenia, and these agents have an increased risk of metabolic adverse effects as well as extrapyramidal symptoms.

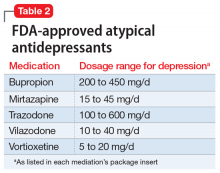

Atypical antidepressants are those that are not classified as an SSRI, SNRI, tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), or monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). These include bupropion, mirtazapine, trazodone, vilazodone, and vortioxetine (Table 2). Bupropion is a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. When used for augmentation in clinical studies, it led to a 30% remission rate.3 Mirtazapine is an alpha-2 antagonist that can be used as monotherapy or in combination with another antidepressant.4 Trazodone is an antidepressant with activity at histamine and alpha-1-adrenergic receptors that is often used off-label for insomnia. Trazodone can be used safely and effectively in combination with other agents for treatment-resistant depression.5 Vilazodone is a 5-HT1A partial agonist, and vortioxetine is a 5-HT1A agonist and 5-HT3 antagonist; both are FDA-approved as alternative agents for monotherapy for major depressive disorder. Choosing among these agents for switching or augmenting can be guided by patient preference, adverse effect profile, and targeting specific symptoms, such as using mirtazapine to address poor sleep and appetite.

Lithium augmentation has been frequently investigated in placebo-controlled, double-blind studies. A meta-analysis showed that patients receiving lithium augmentation with a serum level of ≥0.5 mEq/L were >3 times more likely to respond than those receiving placebo.6 When lithium is used to treat bipolar disorder, the therapeutic serum range for lithium is 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L, with an increased risk of adverse effects (including toxicity) at higher levels.7

Triiodothyronine (T3) augmentation of antidepressants led to remission in approximately 1 in 4 patients who had not achieved remission or who were intolerant to an initial treatment with citalopram and a second switch or augmentation trial.8 In this study, the mean dose of T3 was 45.2 µg/d, with an average length of treatment of 9 weeks.

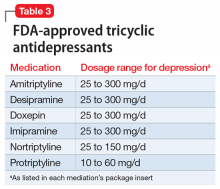

Tricyclic antidepressants are another option when considering switching agents (Table 3). TCAs are additionally effective for comorbid pain conditions.9 When TCAs are used in combination with SSRIs, drug interactions may occur that increase TCA plasma levels. There is also an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when used with serotonergic agents, though an SSRI/ TCA combination may be appropriate for a patient with treatment-resistant depression.10 Additionally, TCAs carry unique risks of cardiovascular effects, including cardiac arrhythmias. A meta-analysis comparing fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline to TCAs (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, and nortriptyline) concluded that both classes had similar efficacy in treating depression, though the drop-out rate was significantly higher among patients receiving TCAs.11

Buspirone is approved for generalized anxiety disorder. In studies where buspirone was used as an augmentation agent for major depressive disorder at a mean daily dose of 40.9 mg divided into 2 doses, it led to a remission rate >30%.3

Continue to: Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

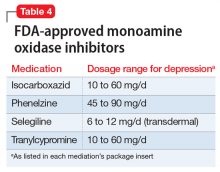

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors should typically be avoided in initial or early treatment of depression due to tolerability issues, drug interactions, and dietary restrictions to avoid hypertensive crisis. MAOIs are generally not recommended to be used with SSRIs, SNRIs, or TCAs, and typically require a “washout” period from other antidepressants (Table 4). One review found that MAOI treatment had advantage over TCA treatment for patients with early-stage treatment-resistant depression, though this advantage decreased as the number of failed antidepressant trials increased.12 One MAOI, selegiline, is available in a transdermal patch, and the 6-mg patch does not require dietary restriction.

Esketamine (intranasal) is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression (failure of response after at least 2 antidepressant trials with adequate dose and duration) in conjunction with an oral antidepressant. In clinical studies, a significant response was noted after 1 week of treatment.13 Esketamine requires an induction period of twice-weekly doses of 56 or 84 mg, with maintenance doses every 1 to 2 weeks. Each dosage administration requires monitoring for at least 2 hours by a health care professional at a certified treatment center. Esketamine’s indication was recently expanded to include treatment of patients with major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation or behavior.

Stimulants such as amphetamines, methylphenidate, or modafinil have been effective in open studies for augmentation in depression.14 However, no stimulant is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression. In addition to other adverse effects, these medications are controlled substances and carry risk of misuse, and their use may not be appropriate for all patients.

1. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

2. Kato M, Chang CM. Augmentation treatments with second-generation antipsychotics to antidepressants in treatment-resistant depression. CNS Drugs. 2013;27 Suppl 1:S11-S19.

3. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

4. Carpenter LL, Jocic Z, Hall JM, et al. Mirtazapine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):45-49.

5. Maes M, Vandoolaeghe E, Desnyder R. Efficacy of treatment with trazodone in combination with pindolol or fluoxetine in major depression. J Affect Disord. 1996;41(3):201-210.

6. Bauer M, Dopfmer S. Lithium augmentation in treatment-resistant depression: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(5):427-434.

7. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

8. Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1519-1530; quiz 1665.

9. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17(4):CD005454.

10. Taylor D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in combination. Interactions and therapeutic uses. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(5):575-580.

11. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ. Are SSRIs better than TCAs? Comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 1997;6(1):10-18.

12. Kim T, Xu C, Amsterdam JD. Relative effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressant versus monoamine oxidase inhibitor monotherapy for treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;250:199-203.

13. Daly EJ, Singh JB, Fedgchin M, et al. Efficacy and safety of intranasal esketamine adjunctive to oral antidepressant therapy in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):139-148.

14. DeBattista C. Augmentation and combination strategies for depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(3 Suppl):11-18.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are commonly used first-line agents for treating major depressive disorder. Less than one-half of patients with major depressive disorder experience remission after 1 acute trial of an antidepressant.1 After optimization of an initial agent’s dose and duration, potential next steps include switching agents or augmentation. Augmentation strategies may lead to clinical improvement but carry the risks of polypharmacy, including increased risk of adverse effects and drug interactions. Clinicians can consider the following evidence-based options for a patient with a limited response to an initial SSRI or SNRI.

Second-generation antipsychotics, when used as augmentation agents to treat a patient with major depressive disorder, can lead to an approximately 10% improvement in remission rate compared with placebo.2 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, olanzapine (in combination with fluoxetine only), and quetiapine are FDA-approved as adjunctive therapies with an antidepressant (Table 1). Second-generation antipsychotics should be started at lower doses than those used for schizophrenia, and these agents have an increased risk of metabolic adverse effects as well as extrapyramidal symptoms.

Atypical antidepressants are those that are not classified as an SSRI, SNRI, tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), or monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). These include bupropion, mirtazapine, trazodone, vilazodone, and vortioxetine (Table 2). Bupropion is a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. When used for augmentation in clinical studies, it led to a 30% remission rate.3 Mirtazapine is an alpha-2 antagonist that can be used as monotherapy or in combination with another antidepressant.4 Trazodone is an antidepressant with activity at histamine and alpha-1-adrenergic receptors that is often used off-label for insomnia. Trazodone can be used safely and effectively in combination with other agents for treatment-resistant depression.5 Vilazodone is a 5-HT1A partial agonist, and vortioxetine is a 5-HT1A agonist and 5-HT3 antagonist; both are FDA-approved as alternative agents for monotherapy for major depressive disorder. Choosing among these agents for switching or augmenting can be guided by patient preference, adverse effect profile, and targeting specific symptoms, such as using mirtazapine to address poor sleep and appetite.

Lithium augmentation has been frequently investigated in placebo-controlled, double-blind studies. A meta-analysis showed that patients receiving lithium augmentation with a serum level of ≥0.5 mEq/L were >3 times more likely to respond than those receiving placebo.6 When lithium is used to treat bipolar disorder, the therapeutic serum range for lithium is 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L, with an increased risk of adverse effects (including toxicity) at higher levels.7

Triiodothyronine (T3) augmentation of antidepressants led to remission in approximately 1 in 4 patients who had not achieved remission or who were intolerant to an initial treatment with citalopram and a second switch or augmentation trial.8 In this study, the mean dose of T3 was 45.2 µg/d, with an average length of treatment of 9 weeks.

Tricyclic antidepressants are another option when considering switching agents (Table 3). TCAs are additionally effective for comorbid pain conditions.9 When TCAs are used in combination with SSRIs, drug interactions may occur that increase TCA plasma levels. There is also an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when used with serotonergic agents, though an SSRI/ TCA combination may be appropriate for a patient with treatment-resistant depression.10 Additionally, TCAs carry unique risks of cardiovascular effects, including cardiac arrhythmias. A meta-analysis comparing fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline to TCAs (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, and nortriptyline) concluded that both classes had similar efficacy in treating depression, though the drop-out rate was significantly higher among patients receiving TCAs.11

Buspirone is approved for generalized anxiety disorder. In studies where buspirone was used as an augmentation agent for major depressive disorder at a mean daily dose of 40.9 mg divided into 2 doses, it led to a remission rate >30%.3

Continue to: Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors should typically be avoided in initial or early treatment of depression due to tolerability issues, drug interactions, and dietary restrictions to avoid hypertensive crisis. MAOIs are generally not recommended to be used with SSRIs, SNRIs, or TCAs, and typically require a “washout” period from other antidepressants (Table 4). One review found that MAOI treatment had advantage over TCA treatment for patients with early-stage treatment-resistant depression, though this advantage decreased as the number of failed antidepressant trials increased.12 One MAOI, selegiline, is available in a transdermal patch, and the 6-mg patch does not require dietary restriction.

Esketamine (intranasal) is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression (failure of response after at least 2 antidepressant trials with adequate dose and duration) in conjunction with an oral antidepressant. In clinical studies, a significant response was noted after 1 week of treatment.13 Esketamine requires an induction period of twice-weekly doses of 56 or 84 mg, with maintenance doses every 1 to 2 weeks. Each dosage administration requires monitoring for at least 2 hours by a health care professional at a certified treatment center. Esketamine’s indication was recently expanded to include treatment of patients with major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation or behavior.

Stimulants such as amphetamines, methylphenidate, or modafinil have been effective in open studies for augmentation in depression.14 However, no stimulant is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression. In addition to other adverse effects, these medications are controlled substances and carry risk of misuse, and their use may not be appropriate for all patients.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are commonly used first-line agents for treating major depressive disorder. Less than one-half of patients with major depressive disorder experience remission after 1 acute trial of an antidepressant.1 After optimization of an initial agent’s dose and duration, potential next steps include switching agents or augmentation. Augmentation strategies may lead to clinical improvement but carry the risks of polypharmacy, including increased risk of adverse effects and drug interactions. Clinicians can consider the following evidence-based options for a patient with a limited response to an initial SSRI or SNRI.

Second-generation antipsychotics, when used as augmentation agents to treat a patient with major depressive disorder, can lead to an approximately 10% improvement in remission rate compared with placebo.2 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, olanzapine (in combination with fluoxetine only), and quetiapine are FDA-approved as adjunctive therapies with an antidepressant (Table 1). Second-generation antipsychotics should be started at lower doses than those used for schizophrenia, and these agents have an increased risk of metabolic adverse effects as well as extrapyramidal symptoms.

Atypical antidepressants are those that are not classified as an SSRI, SNRI, tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), or monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). These include bupropion, mirtazapine, trazodone, vilazodone, and vortioxetine (Table 2). Bupropion is a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. When used for augmentation in clinical studies, it led to a 30% remission rate.3 Mirtazapine is an alpha-2 antagonist that can be used as monotherapy or in combination with another antidepressant.4 Trazodone is an antidepressant with activity at histamine and alpha-1-adrenergic receptors that is often used off-label for insomnia. Trazodone can be used safely and effectively in combination with other agents for treatment-resistant depression.5 Vilazodone is a 5-HT1A partial agonist, and vortioxetine is a 5-HT1A agonist and 5-HT3 antagonist; both are FDA-approved as alternative agents for monotherapy for major depressive disorder. Choosing among these agents for switching or augmenting can be guided by patient preference, adverse effect profile, and targeting specific symptoms, such as using mirtazapine to address poor sleep and appetite.

Lithium augmentation has been frequently investigated in placebo-controlled, double-blind studies. A meta-analysis showed that patients receiving lithium augmentation with a serum level of ≥0.5 mEq/L were >3 times more likely to respond than those receiving placebo.6 When lithium is used to treat bipolar disorder, the therapeutic serum range for lithium is 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L, with an increased risk of adverse effects (including toxicity) at higher levels.7

Triiodothyronine (T3) augmentation of antidepressants led to remission in approximately 1 in 4 patients who had not achieved remission or who were intolerant to an initial treatment with citalopram and a second switch or augmentation trial.8 In this study, the mean dose of T3 was 45.2 µg/d, with an average length of treatment of 9 weeks.

Tricyclic antidepressants are another option when considering switching agents (Table 3). TCAs are additionally effective for comorbid pain conditions.9 When TCAs are used in combination with SSRIs, drug interactions may occur that increase TCA plasma levels. There is also an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when used with serotonergic agents, though an SSRI/ TCA combination may be appropriate for a patient with treatment-resistant depression.10 Additionally, TCAs carry unique risks of cardiovascular effects, including cardiac arrhythmias. A meta-analysis comparing fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline to TCAs (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, and nortriptyline) concluded that both classes had similar efficacy in treating depression, though the drop-out rate was significantly higher among patients receiving TCAs.11

Buspirone is approved for generalized anxiety disorder. In studies where buspirone was used as an augmentation agent for major depressive disorder at a mean daily dose of 40.9 mg divided into 2 doses, it led to a remission rate >30%.3

Continue to: Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors should typically be avoided in initial or early treatment of depression due to tolerability issues, drug interactions, and dietary restrictions to avoid hypertensive crisis. MAOIs are generally not recommended to be used with SSRIs, SNRIs, or TCAs, and typically require a “washout” period from other antidepressants (Table 4). One review found that MAOI treatment had advantage over TCA treatment for patients with early-stage treatment-resistant depression, though this advantage decreased as the number of failed antidepressant trials increased.12 One MAOI, selegiline, is available in a transdermal patch, and the 6-mg patch does not require dietary restriction.

Esketamine (intranasal) is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression (failure of response after at least 2 antidepressant trials with adequate dose and duration) in conjunction with an oral antidepressant. In clinical studies, a significant response was noted after 1 week of treatment.13 Esketamine requires an induction period of twice-weekly doses of 56 or 84 mg, with maintenance doses every 1 to 2 weeks. Each dosage administration requires monitoring for at least 2 hours by a health care professional at a certified treatment center. Esketamine’s indication was recently expanded to include treatment of patients with major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation or behavior.

Stimulants such as amphetamines, methylphenidate, or modafinil have been effective in open studies for augmentation in depression.14 However, no stimulant is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression. In addition to other adverse effects, these medications are controlled substances and carry risk of misuse, and their use may not be appropriate for all patients.

1. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

2. Kato M, Chang CM. Augmentation treatments with second-generation antipsychotics to antidepressants in treatment-resistant depression. CNS Drugs. 2013;27 Suppl 1:S11-S19.

3. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

4. Carpenter LL, Jocic Z, Hall JM, et al. Mirtazapine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):45-49.

5. Maes M, Vandoolaeghe E, Desnyder R. Efficacy of treatment with trazodone in combination with pindolol or fluoxetine in major depression. J Affect Disord. 1996;41(3):201-210.

6. Bauer M, Dopfmer S. Lithium augmentation in treatment-resistant depression: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(5):427-434.

7. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

8. Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1519-1530; quiz 1665.

9. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17(4):CD005454.

10. Taylor D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in combination. Interactions and therapeutic uses. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(5):575-580.

11. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ. Are SSRIs better than TCAs? Comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 1997;6(1):10-18.

12. Kim T, Xu C, Amsterdam JD. Relative effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressant versus monoamine oxidase inhibitor monotherapy for treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;250:199-203.

13. Daly EJ, Singh JB, Fedgchin M, et al. Efficacy and safety of intranasal esketamine adjunctive to oral antidepressant therapy in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):139-148.

14. DeBattista C. Augmentation and combination strategies for depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(3 Suppl):11-18.

1. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

2. Kato M, Chang CM. Augmentation treatments with second-generation antipsychotics to antidepressants in treatment-resistant depression. CNS Drugs. 2013;27 Suppl 1:S11-S19.

3. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

4. Carpenter LL, Jocic Z, Hall JM, et al. Mirtazapine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):45-49.

5. Maes M, Vandoolaeghe E, Desnyder R. Efficacy of treatment with trazodone in combination with pindolol or fluoxetine in major depression. J Affect Disord. 1996;41(3):201-210.

6. Bauer M, Dopfmer S. Lithium augmentation in treatment-resistant depression: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(5):427-434.

7. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

8. Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1519-1530; quiz 1665.

9. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17(4):CD005454.

10. Taylor D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in combination. Interactions and therapeutic uses. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(5):575-580.

11. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ. Are SSRIs better than TCAs? Comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 1997;6(1):10-18.

12. Kim T, Xu C, Amsterdam JD. Relative effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressant versus monoamine oxidase inhibitor monotherapy for treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;250:199-203.

13. Daly EJ, Singh JB, Fedgchin M, et al. Efficacy and safety of intranasal esketamine adjunctive to oral antidepressant therapy in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):139-148.

14. DeBattista C. Augmentation and combination strategies for depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(3 Suppl):11-18.