User login

Should lithium and ECT be used concurrently in geriatric patients?

Delirium has been described as a potential complication of concurrent lithium and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for depression, in association with a range of serum lithium levels. Although debate persists about the safety of continuing previously established lithium therapy during a course of ECT for mood symptoms, withholding lithium for 24 hours before administering ECT and measuring the serum lithium level before ECT were found to decrease the risk of post-ECT neurocognitive effects.1

We have found that the conventional practice of holding lithium for 24 hours before ECT might need to be re-evaluated in geriatric patients, as the following case demonstrates. Only 24 hours of holding lithium therapy might result in a lithium level sufficient to contribute to delirium after ECT.

CASE REPORT

An older woman with recurrent unipolar psychotic depression

Mrs. A, age 81, was admitted to the hospital with a 1-week history of depressed mood, anhedonia, insomnia, anergia, anorexia, and nihilistic somatic delusions that her organs were “rotting and shutting down.” Treatment included nortriptyline, 40 mg/d; lithium, 150 mg/d; and haloperidol, 0.5 mg/d. Her serum lithium level was 0.3 mEq/L (reference range, 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L); the serum nortriptyline level was 68 ng/mL (reference range, 50 to 150 ng/mL). CT of the head and an electrocardiogram were unremarkable.

A twice-weekly course of ECT was initiated.

The day before Treatment 1 of ECT, the serum lithium level (drawn 12 hours after the last dose) was 0.4 mEq/L. Lithium was withheld 24 hours before ECT; nortriptyline and haloperidol were continued at prescribed dosages.

Right unilateral stimulation was used at 50%/mC energy (Thymatron DG, with methohexital anesthesia, and succinylcholine for muscle relaxation). Seizure duration, measured by EEG, was 57 seconds.

Mrs. A developed postictal delirium after the first 2 ECT sessions. The serum lithium level was unchanged. Subsequently, lithium treatment was discontinued and ECT was continued; once lithium was stopped, delirium resolved. ECT sessions 3 and 4 were uneventful, with no post-treatment delirium. Seizure duration for Treatment 4 was 58 seconds. She started breathing easily after all ECT sessions.

After Treatment 4, Mrs. A experienced full remission of depressive and psychotic symptoms. Repeat CT of head, after Treatment 4, was unchanged from baseline.

What is the role of lithium?

Mrs. A did not exhibit typical signs of lithium intoxication (diarrhea, vomiting, tremor). Notably, lithium has an intrinsic anticholinergic activity2; concurrent nortriptyline, a secondary amine tricyclic antidepressant with fewer anticholinergic side effects than other tricyclics,2 could precipitate delirium in a vulnerable patient secondary to excessive cumulative anticholinergic exposure.

No prolonged time-to-respiration or time-to-awakening occurred during treatments in which concurrent lithium and ECT were used; seizure duration with and without concurrent lithium was relatively similar.

There are potential complications of concurrent use of lithium and ECT:

• prolongation of the duration of muscle paralysis and apnea induced by commonly used neuromuscular-blocking agents (eg, succinylcholine)

• post-ECT cognitive disturbance.1,3,4

There is debate about the safety of continuing lithium during, or in close proximity to, ECT. In a case series of 12 patients who underwent combined lithium therapy and ECT, the authors concluded that this combination can be safe, regardless of age, as long as appropriate clinical monitoring is provided.4 In Mrs. A’s case, once post-ECT delirium was noted, lithium was discontinued for subsequent ECT sessions.

Because further ECT was uneventful without lithium, and no other clear acute cause of delirium could be identified, we concluded that lithium likely played a role in Mrs. A’s delirium. Notably, nortriptyline had been continued, suggesting that the degree of anticholinergic blockade provided by nortriptyline was insufficient to provoke delirium post-ECT in the absence of potentiation of this effect, as it had been when lithium also was used initially.

Guidelines for dosing and serum lithium concentrations in geriatric patients are not well-established; the current traditional range of 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L, is too high for geriatric patients and can result in episodes of lithium toxicity, including delirium.5 Although our patient’s lithium level was below the reference range for all patients, a level of 0.3 mEq/L can be considered at the low end of the reference range for geriatric patients.5 Inasmuch as the lithium-assisted post-ECT delirium could represent a clinical sign of lithium toxicity, perhaps even a subtherapeutic level in a certain patient could be paradoxically “toxic.”

Although the serum lithium level in our patient remained below the toxic level for the general population (>1.5 mEq/L), delirium in a geriatric patient could result from:

• age-related changes in the pharmacokinetics of lithium, a water-soluble drug; these changes reduce renal clearance of the drug and extend plasma elimination half-life of a single dose to 36 hours, with the result that lithium remains in the body longer and necessitating a lower dosage (ie, a dosage that yields a serum level of approximately 0.5 mEq/L)

• the CNS tissue concentration of lithium, which can be high even though the serum level is not toxic

• an age-related increase in blood-brain barrier permeability, making the barrier more porous for drugs

• changes in blood-brain barrier permeability by post-ECT biochemical induction, with subsequent increased drug availability in the CNS.5,6

What we recommend

Possible interactions between lithium and ECT that lead to ECT-associated delirium need further elucidation, but discontinuing lithium during the course of ECT in a geriatric patient warrants your consideration. Following a safe interval after the last ECT session, lithium likely can be safely re-introduced 1) if there is clinical need and 2) as long as clinical surveillance for cognitive side effects is provided— especially if ECT will need to be reconsidered in the future.

Two additional considerations:

• Actively reassess lithium dosing in all geriatric psychiatric patients, especially those with renal insufficiency and other systemic metabolic considerations.

• Actively examine the use of all other anticholinergic agents in the course of evaluating a patient’s candidacy for ECT.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Psychiatric Association. The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging. A task force report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2001.

2. Chew ML, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, et al. Anticholinergic activity of 107 medications commonly used by older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1333-1341.

3. Hill GE, Wong KC, Hodges MR. Potentiation of succinylcholine neuromuscular blockade by lithium carbonate. Anesthesiology. 1976;44(5):439-442.

4. Dolenc TJ, Rasmussen KG. The safety of electroconvulsive therapy and lithium in combination: a case series and review of the literature. J ECT. 2005;21(3):165-170.

5. Shulman KI. Lithium for older adults with bipolar disorder: should it still be considered a first line agent? Drugs Aging. 2010;27(8):607-615.

6. Grandjean EM, Aubry JM. Lithium: updated human knowledge using an evidence-based approach. Part II: clinical pharmacology and therapeutic monitoring. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(4):331-349.

Delirium has been described as a potential complication of concurrent lithium and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for depression, in association with a range of serum lithium levels. Although debate persists about the safety of continuing previously established lithium therapy during a course of ECT for mood symptoms, withholding lithium for 24 hours before administering ECT and measuring the serum lithium level before ECT were found to decrease the risk of post-ECT neurocognitive effects.1

We have found that the conventional practice of holding lithium for 24 hours before ECT might need to be re-evaluated in geriatric patients, as the following case demonstrates. Only 24 hours of holding lithium therapy might result in a lithium level sufficient to contribute to delirium after ECT.

CASE REPORT

An older woman with recurrent unipolar psychotic depression

Mrs. A, age 81, was admitted to the hospital with a 1-week history of depressed mood, anhedonia, insomnia, anergia, anorexia, and nihilistic somatic delusions that her organs were “rotting and shutting down.” Treatment included nortriptyline, 40 mg/d; lithium, 150 mg/d; and haloperidol, 0.5 mg/d. Her serum lithium level was 0.3 mEq/L (reference range, 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L); the serum nortriptyline level was 68 ng/mL (reference range, 50 to 150 ng/mL). CT of the head and an electrocardiogram were unremarkable.

A twice-weekly course of ECT was initiated.

The day before Treatment 1 of ECT, the serum lithium level (drawn 12 hours after the last dose) was 0.4 mEq/L. Lithium was withheld 24 hours before ECT; nortriptyline and haloperidol were continued at prescribed dosages.

Right unilateral stimulation was used at 50%/mC energy (Thymatron DG, with methohexital anesthesia, and succinylcholine for muscle relaxation). Seizure duration, measured by EEG, was 57 seconds.

Mrs. A developed postictal delirium after the first 2 ECT sessions. The serum lithium level was unchanged. Subsequently, lithium treatment was discontinued and ECT was continued; once lithium was stopped, delirium resolved. ECT sessions 3 and 4 were uneventful, with no post-treatment delirium. Seizure duration for Treatment 4 was 58 seconds. She started breathing easily after all ECT sessions.

After Treatment 4, Mrs. A experienced full remission of depressive and psychotic symptoms. Repeat CT of head, after Treatment 4, was unchanged from baseline.

What is the role of lithium?

Mrs. A did not exhibit typical signs of lithium intoxication (diarrhea, vomiting, tremor). Notably, lithium has an intrinsic anticholinergic activity2; concurrent nortriptyline, a secondary amine tricyclic antidepressant with fewer anticholinergic side effects than other tricyclics,2 could precipitate delirium in a vulnerable patient secondary to excessive cumulative anticholinergic exposure.

No prolonged time-to-respiration or time-to-awakening occurred during treatments in which concurrent lithium and ECT were used; seizure duration with and without concurrent lithium was relatively similar.

There are potential complications of concurrent use of lithium and ECT:

• prolongation of the duration of muscle paralysis and apnea induced by commonly used neuromuscular-blocking agents (eg, succinylcholine)

• post-ECT cognitive disturbance.1,3,4

There is debate about the safety of continuing lithium during, or in close proximity to, ECT. In a case series of 12 patients who underwent combined lithium therapy and ECT, the authors concluded that this combination can be safe, regardless of age, as long as appropriate clinical monitoring is provided.4 In Mrs. A’s case, once post-ECT delirium was noted, lithium was discontinued for subsequent ECT sessions.

Because further ECT was uneventful without lithium, and no other clear acute cause of delirium could be identified, we concluded that lithium likely played a role in Mrs. A’s delirium. Notably, nortriptyline had been continued, suggesting that the degree of anticholinergic blockade provided by nortriptyline was insufficient to provoke delirium post-ECT in the absence of potentiation of this effect, as it had been when lithium also was used initially.

Guidelines for dosing and serum lithium concentrations in geriatric patients are not well-established; the current traditional range of 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L, is too high for geriatric patients and can result in episodes of lithium toxicity, including delirium.5 Although our patient’s lithium level was below the reference range for all patients, a level of 0.3 mEq/L can be considered at the low end of the reference range for geriatric patients.5 Inasmuch as the lithium-assisted post-ECT delirium could represent a clinical sign of lithium toxicity, perhaps even a subtherapeutic level in a certain patient could be paradoxically “toxic.”

Although the serum lithium level in our patient remained below the toxic level for the general population (>1.5 mEq/L), delirium in a geriatric patient could result from:

• age-related changes in the pharmacokinetics of lithium, a water-soluble drug; these changes reduce renal clearance of the drug and extend plasma elimination half-life of a single dose to 36 hours, with the result that lithium remains in the body longer and necessitating a lower dosage (ie, a dosage that yields a serum level of approximately 0.5 mEq/L)

• the CNS tissue concentration of lithium, which can be high even though the serum level is not toxic

• an age-related increase in blood-brain barrier permeability, making the barrier more porous for drugs

• changes in blood-brain barrier permeability by post-ECT biochemical induction, with subsequent increased drug availability in the CNS.5,6

What we recommend

Possible interactions between lithium and ECT that lead to ECT-associated delirium need further elucidation, but discontinuing lithium during the course of ECT in a geriatric patient warrants your consideration. Following a safe interval after the last ECT session, lithium likely can be safely re-introduced 1) if there is clinical need and 2) as long as clinical surveillance for cognitive side effects is provided— especially if ECT will need to be reconsidered in the future.

Two additional considerations:

• Actively reassess lithium dosing in all geriatric psychiatric patients, especially those with renal insufficiency and other systemic metabolic considerations.

• Actively examine the use of all other anticholinergic agents in the course of evaluating a patient’s candidacy for ECT.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Delirium has been described as a potential complication of concurrent lithium and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for depression, in association with a range of serum lithium levels. Although debate persists about the safety of continuing previously established lithium therapy during a course of ECT for mood symptoms, withholding lithium for 24 hours before administering ECT and measuring the serum lithium level before ECT were found to decrease the risk of post-ECT neurocognitive effects.1

We have found that the conventional practice of holding lithium for 24 hours before ECT might need to be re-evaluated in geriatric patients, as the following case demonstrates. Only 24 hours of holding lithium therapy might result in a lithium level sufficient to contribute to delirium after ECT.

CASE REPORT

An older woman with recurrent unipolar psychotic depression

Mrs. A, age 81, was admitted to the hospital with a 1-week history of depressed mood, anhedonia, insomnia, anergia, anorexia, and nihilistic somatic delusions that her organs were “rotting and shutting down.” Treatment included nortriptyline, 40 mg/d; lithium, 150 mg/d; and haloperidol, 0.5 mg/d. Her serum lithium level was 0.3 mEq/L (reference range, 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L); the serum nortriptyline level was 68 ng/mL (reference range, 50 to 150 ng/mL). CT of the head and an electrocardiogram were unremarkable.

A twice-weekly course of ECT was initiated.

The day before Treatment 1 of ECT, the serum lithium level (drawn 12 hours after the last dose) was 0.4 mEq/L. Lithium was withheld 24 hours before ECT; nortriptyline and haloperidol were continued at prescribed dosages.

Right unilateral stimulation was used at 50%/mC energy (Thymatron DG, with methohexital anesthesia, and succinylcholine for muscle relaxation). Seizure duration, measured by EEG, was 57 seconds.

Mrs. A developed postictal delirium after the first 2 ECT sessions. The serum lithium level was unchanged. Subsequently, lithium treatment was discontinued and ECT was continued; once lithium was stopped, delirium resolved. ECT sessions 3 and 4 were uneventful, with no post-treatment delirium. Seizure duration for Treatment 4 was 58 seconds. She started breathing easily after all ECT sessions.

After Treatment 4, Mrs. A experienced full remission of depressive and psychotic symptoms. Repeat CT of head, after Treatment 4, was unchanged from baseline.

What is the role of lithium?

Mrs. A did not exhibit typical signs of lithium intoxication (diarrhea, vomiting, tremor). Notably, lithium has an intrinsic anticholinergic activity2; concurrent nortriptyline, a secondary amine tricyclic antidepressant with fewer anticholinergic side effects than other tricyclics,2 could precipitate delirium in a vulnerable patient secondary to excessive cumulative anticholinergic exposure.

No prolonged time-to-respiration or time-to-awakening occurred during treatments in which concurrent lithium and ECT were used; seizure duration with and without concurrent lithium was relatively similar.

There are potential complications of concurrent use of lithium and ECT:

• prolongation of the duration of muscle paralysis and apnea induced by commonly used neuromuscular-blocking agents (eg, succinylcholine)

• post-ECT cognitive disturbance.1,3,4

There is debate about the safety of continuing lithium during, or in close proximity to, ECT. In a case series of 12 patients who underwent combined lithium therapy and ECT, the authors concluded that this combination can be safe, regardless of age, as long as appropriate clinical monitoring is provided.4 In Mrs. A’s case, once post-ECT delirium was noted, lithium was discontinued for subsequent ECT sessions.

Because further ECT was uneventful without lithium, and no other clear acute cause of delirium could be identified, we concluded that lithium likely played a role in Mrs. A’s delirium. Notably, nortriptyline had been continued, suggesting that the degree of anticholinergic blockade provided by nortriptyline was insufficient to provoke delirium post-ECT in the absence of potentiation of this effect, as it had been when lithium also was used initially.

Guidelines for dosing and serum lithium concentrations in geriatric patients are not well-established; the current traditional range of 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L, is too high for geriatric patients and can result in episodes of lithium toxicity, including delirium.5 Although our patient’s lithium level was below the reference range for all patients, a level of 0.3 mEq/L can be considered at the low end of the reference range for geriatric patients.5 Inasmuch as the lithium-assisted post-ECT delirium could represent a clinical sign of lithium toxicity, perhaps even a subtherapeutic level in a certain patient could be paradoxically “toxic.”

Although the serum lithium level in our patient remained below the toxic level for the general population (>1.5 mEq/L), delirium in a geriatric patient could result from:

• age-related changes in the pharmacokinetics of lithium, a water-soluble drug; these changes reduce renal clearance of the drug and extend plasma elimination half-life of a single dose to 36 hours, with the result that lithium remains in the body longer and necessitating a lower dosage (ie, a dosage that yields a serum level of approximately 0.5 mEq/L)

• the CNS tissue concentration of lithium, which can be high even though the serum level is not toxic

• an age-related increase in blood-brain barrier permeability, making the barrier more porous for drugs

• changes in blood-brain barrier permeability by post-ECT biochemical induction, with subsequent increased drug availability in the CNS.5,6

What we recommend

Possible interactions between lithium and ECT that lead to ECT-associated delirium need further elucidation, but discontinuing lithium during the course of ECT in a geriatric patient warrants your consideration. Following a safe interval after the last ECT session, lithium likely can be safely re-introduced 1) if there is clinical need and 2) as long as clinical surveillance for cognitive side effects is provided— especially if ECT will need to be reconsidered in the future.

Two additional considerations:

• Actively reassess lithium dosing in all geriatric psychiatric patients, especially those with renal insufficiency and other systemic metabolic considerations.

• Actively examine the use of all other anticholinergic agents in the course of evaluating a patient’s candidacy for ECT.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Psychiatric Association. The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging. A task force report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2001.

2. Chew ML, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, et al. Anticholinergic activity of 107 medications commonly used by older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1333-1341.

3. Hill GE, Wong KC, Hodges MR. Potentiation of succinylcholine neuromuscular blockade by lithium carbonate. Anesthesiology. 1976;44(5):439-442.

4. Dolenc TJ, Rasmussen KG. The safety of electroconvulsive therapy and lithium in combination: a case series and review of the literature. J ECT. 2005;21(3):165-170.

5. Shulman KI. Lithium for older adults with bipolar disorder: should it still be considered a first line agent? Drugs Aging. 2010;27(8):607-615.

6. Grandjean EM, Aubry JM. Lithium: updated human knowledge using an evidence-based approach. Part II: clinical pharmacology and therapeutic monitoring. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(4):331-349.

1. American Psychiatric Association. The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging. A task force report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2001.

2. Chew ML, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, et al. Anticholinergic activity of 107 medications commonly used by older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1333-1341.

3. Hill GE, Wong KC, Hodges MR. Potentiation of succinylcholine neuromuscular blockade by lithium carbonate. Anesthesiology. 1976;44(5):439-442.

4. Dolenc TJ, Rasmussen KG. The safety of electroconvulsive therapy and lithium in combination: a case series and review of the literature. J ECT. 2005;21(3):165-170.

5. Shulman KI. Lithium for older adults with bipolar disorder: should it still be considered a first line agent? Drugs Aging. 2010;27(8):607-615.

6. Grandjean EM, Aubry JM. Lithium: updated human knowledge using an evidence-based approach. Part II: clinical pharmacology and therapeutic monitoring. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(4):331-349.

Current and novel therapeutic approaches in myelodysplastic syndromes

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous group of hematologic neoplasms with an annual incidence of 4.1 cases per 100,000 Americans. Patients with MDS suffer from chronic cytopenias that may lead to recurrent transfusions, infections, and increased risk for bleeding. They are also at risk for progression to acute myeloid leukemia. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation is the only potentially curative treatment for MDS, although 3 drugs have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for its treatment: lenalidomide, 5-azacitidine, and decitabine.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous group of hematologic neoplasms with an annual incidence of 4.1 cases per 100,000 Americans. Patients with MDS suffer from chronic cytopenias that may lead to recurrent transfusions, infections, and increased risk for bleeding. They are also at risk for progression to acute myeloid leukemia. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation is the only potentially curative treatment for MDS, although 3 drugs have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for its treatment: lenalidomide, 5-azacitidine, and decitabine.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous group of hematologic neoplasms with an annual incidence of 4.1 cases per 100,000 Americans. Patients with MDS suffer from chronic cytopenias that may lead to recurrent transfusions, infections, and increased risk for bleeding. They are also at risk for progression to acute myeloid leukemia. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation is the only potentially curative treatment for MDS, although 3 drugs have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for its treatment: lenalidomide, 5-azacitidine, and decitabine.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Delirium in the hospital: Emphasis on the management of geriatric patients

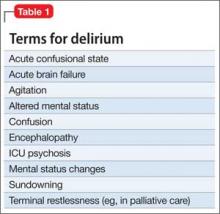

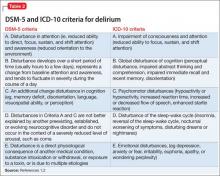

Although delirium has many descriptive terms (Table 1), a common unifying term is “acute global cognitive dysfunction,” now recognized as delirium; a consensus supported by DSM-51 and ICD-102 (Table 2). According to DSM-5, the essential feature is a disturbance of attention or awareness that is accompanied by a change in baseline cognition that cannot be explained by another preexisting, established, or evolving neurocognitive disorder (the newly named DSM-5 entity for dementia syndromes).1 Because delirium affects the cortex diffusely, psychiatric symptoms can include cognitive, mood, anxiety, or psychotic symptoms. Because many systemic illnesses can induce delirium, the differential diagnosis spans all organ systems.

Three subtypes

Delirium can be classified, based on symptoms,3,4 into 3 subtypes: hyperactive-hyperalert, hypoactive-hypoalert, and mixed delirium. Hyperactive patients present with restlessness and agitation. Hypoactive patients are lethargic, confused, slow to respond to questions, and often appear depressed. The differential prognostic significance of these subtypes has been examined in the literature, with conflicting results. Rabinowitz5 reported that hypoactive delirium has the worst prognosis, while Marcantonio et al6 indicated that the hyperactive subtype is associated with the highest mortality rate. Mixed delirium, with periods of both hyperactivity and hypoactivity, is the most common type of delirium.7

A prodromal phase, characterized by anxiety, frequent requests for nursing and medical assistance, decreased attention, restlessness, vivid dreams, disorientation immediately after awakening, and hallucinations, can occur before an episode of full-spectrum delirium; this prodromal state often is identified retrospectively —after the patient is in an episode of delirium.8,9

Evidence-based guidelines aim to improve recognition and clinical management.10-13 Disruptive behavior is the main reason for psychiatric referral in delirium.14,15 Delayed psychiatric consultation because of non-recognition of delirium is related to variables such as older age; history of a pre-existing, comorbid neurocognitive disorder; and the clinical appearance of hypoactive delirium.14

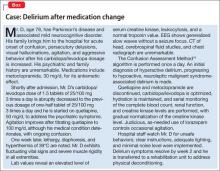

The case of Mr. D (Box),16 illustrates how the emergence of antipsychotic-associated neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) can complicate antipsychotic treatment of delirium in a geriatric medical patient, although delirium also is a common presentation in NMS.17 Delirium developed after an increase in carbidopa/levodopa, which has central dopaminergic effects that can precipitate delirium, particularly in a geriatric patient with preexisting comorbid neurocognitive disorder. Further complicating Mr. D’s delirium presentation was the development of NMS, which had a multifactorial causation, such as the use of dopamine antagonists (ie, quetiapine, metoclopramide), and an abrupt decrease of a dopaminergic agent (ie, carbidopa/levodopa), all inducing a central dopamine relative hypoactivity.

Epidemiology

Delirium is more common in older patients,15 and is seen in 30% to 40% of hospitalized geriatric patients.18 Delirium in older patients, compared with other adults, is associated with more severe cognitive impairment.19 It is common among geriatric surgical patients (15% to 62%)20 with a peak 2 to 5 days postoperatively for hip fracture,21 and often is seen in ICU patients (70% to 87%).20 However, Spronk et al22 found that delirium is significantly under-recognized in the ICU. Nearly 90% of terminally ill patients become delirious before death.23 Terminal delirium often is unrecognized and can interfere with assessment of other clinical problems.24 A preexisting history of comorbid neurocognitive disorder was evident in as many as two-thirds of delirium cases.25

Pathophysiology and risk factors

The pathophysiology of delirium has been characterized as an imbalance of CNS metabolism, including decreased blood flow in various regions of the brain that may normalize once delirium resolves.26 Studies describe the simultaneous decrease of cholinergic transmission and dopaminergic excess.27,28 Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium that are of particular importance in geriatric patients include:

• advanced age

• CNS disease

• infection

• cognitive impairment

• male sex

• poor nutrition

• dehydration and other metabolic abnormalities

• cardiovascular events

• substance use

• medication

• sensory deprivation (eg, impaired vision or hearing)

• sleep deprivation

• low level of physical activity.27,29,30

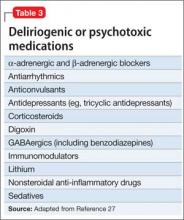

Table 3 lists the most common delirium-provocative medications.27

Evaluation and psychometric scales

The EEG can be useful in evaluating delirium, especially in clinically ambiguous cases. EEG findings may indicate generalized slowing or dropout of the posterior dominant rhythm, and generalized slow theta and delta waves, findings that are more common in delirium than in other neurocognitive disorders and other psychiatric illnesses. The EEG must be interpreted in the context of the delirium diagnostic workup, because abnormalities seen in other neurocognitive disorders can overlap with those of delirium.31

The EEG referral should specify the clinical suspicion of delirium to help interpret the results. Delirium cases in which the patient’s previous cognitive status is unknown may benefit from EEG evaluation, such as:

• in possible status epilepticus

• when delirium improvement has reached a plateau at a lower level of cognitive function than before onset of delirium

• when the patient is unable or unwilling to complete a psychiatric interview.27

Assessment instruments are available to diagnose and monitor delirium (Table 4). Typically, delirium assessment includes examining levels of arousal, psychomotor activity, cognition (ie, orientation, attention, and memory), and perceptual disturbances.

Psychometrically, a review of Table 4 suggests that validity appeared stable with adequate specificity (64% to 99%) but more variable sensitivity (36% to 100%). These reliability parameters also will be affected by the classification system (ie, DSM vs ICD) and the cut-off score employed.32 Most measures (eg, Confusion Assessment Method [CAM], CAM-ICU) provide an adequate sample of behavioral (ie, level of alertness), motor (ie, psychomotor activity), and cognitive (ie, orientation, attention, memory, and receptive language) function, with the exception of the Global Attentiveness Rating, which is a 2-minute open conversation protocol between physician and patient.

Some measures are stand-alone instruments, such as the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale, whereas the CAM requires administration of separate cognitive screens, including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Digit Span.33 Instruments to detect delirium in critically ill patients are a more recent development. Wong et al34 reported that the most widely studied tool was the CAM. Obtaining collateral information from family, caregivers, and hospital staff is essential, particularly given the fluctuating nature of delirium.

Management

Prevention. Identify patients at high risk of delirium so that preventive strategies can be employed. Multi-component, nonpharmacotherapeutic interventions are used in clinical settings but few randomized trials have been conducted. The contributing effectiveness of individual components is not well-studied, but most include staff education to increase awareness of delirium. Of 3 multi-component intervention randomized trials, 2 reported a significantly lower incidence of delirium in the intervention group.35-37 Implementation of a multi-component protocol in medical/ surgical units was associated with a significant reduction in use of restraints.38

As in Mr. D’s case, complex drug regimens, particularly for CNS illness, can increase the risk of delirium. Considering the medication profile for patients with complex systemic illness—in particular, minimizing the use anticholinergics and dopamine agonists— may be crucial in preventing delirium.

Prophylactic administration of antipsychotics may reduce the risk of developing postoperative delirium.39 Studies of the use of these agents were characterized by small sample sizes and selected groups of patient populations. Of the 4 randomized studies evaluating prophylactic antipsychotics (vs placebo), 3 found a lower incidence of delirium in the intervention groups.39-41

A study of haloperidol in post-GI surgery patients showed a reduced occurrence of delirium,40 whereas its prophylactic use in patients undergoing hip surgery42 did not reduce the incidence of delirium compared with placebo, but did decrease severity when delirium occurred.42

Risperidone39 in post-cardiac surgery and olanzapine41 perioperatively in patients undergoing total knee or hip replacement have been shown to decrease delirium severity and duration. Targeted prophylaxis with risperidone43 in post-cardiac surgery patients who showed disturbed cognition but did not meet criteria for delirium reduced the number of patients requiring medication, compared with placebo.43

Dexmedetomidine, an α-2 adrenergic receptor agonist, compared with propofol or midazolam in post-cardiac valve surgery patients, resulted in a decreased incidence of delirium but no difference in delirium duration, hospital length of stay, or use of other medications.44 However, other studies have shown that dexmedetomidine reduces ICU length of stay and duration of mechanical ventilation.45

Treatment. Management of hospitalized medically ill geriatric patients with delirium is challenging and requires a comprehensive approach. The first step in delirium management is prompt identification and management of systemic medical disturbances associated with the delirium episode. First-line, nonpharmacotherapeutic strategies for patients with delirium include:

• reorientation

• behavioral interventions (eg, use of clear instructions and frequent eye contact with patients)

• environmental interventions (eg, minimal noise, adequate lighting, and limited room and staff changes)

• avoidance of physical restraints.46

Consider employing family members or hospital staff sitters to stay with the patient and to reassure, reorient, and watch for agitation and other unsafe behaviors (eg, attempted elopement). Psychoeducation for the patient and family on the phenomenology of delirium can be helpful.

The use of drug treatment strategies should be integrated into a comprehensive approach that includes the routine use of nondrug measures.46 Using medications for treating hypoactive delirium, formerly controversial, now has wider acceptance.47,48 A few high-quality randomized trials have been performed.25,49,50

Pharmacotherapy, especially in frail patients, should be initiated at the lowest starting dosage and titrated cautiously to clinical effect and for the shortest period of time necessary. Antipsychotics are preferred agents for treating all subtypes of delirium; haloperidol is widely used.46,51,52 However, antipsychotics, including haloperidol, can be associated with adverse neurologic effects such as extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and NMS.

Although reported less frequently than with haloperidol, other agents have been implicated in development of EPS and NMS, including atypical antipsychotics and antiemetic dopamine antagonists, particularly in parkinsonism-prone patients.53 Strategies that can minimize such risks in geriatric inpatients with delirium include oral, rather than parenteral, use of antipsychotics—preferential use of atypical over typical antipsychotics— and lowest effective dosages.54

In controlled trials, atypical antipsychotics for delirium showed efficacy compared with haloperidol.52,55 However, there is no research that demonstrates any advantage of one atypical over another.25

In Mr. D’s case, the most important intervention for managing delirium caused by NMS is to discontinue all dopamine antagonists and treat agitation with judicious doses of a benzodiazepine, with supportive care.17 In cases of sudden discontinuation or a dosage decrease of dopamine agonists, these medications should be resumed or optimized to minimize the risk of NMS-associated rhabdomyolysis and subsequent renal failure.17 Antipsychotics carry an increased risk of stroke and mortality in older patients with established or evolving neurocognitive disorders56,57 and can cause prolongation of the QTc interval.57

Other medications that could be used for delirium include cholinesterase inhibitors58,59 (although larger trials and a systematic review did not support this use60), and 5-HT receptor antagonists,61 such as trazodone. Benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam, are first-line treatment for delirium associated with seizures or withdrawal from alcohol, sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics and for delirium caused by NMS. Be cautious about using benzodiazepines in geriatric patients because of a risk of respiratory depression, falls, sedation, and amnesia.

Geriatric patients with alcoholism and those with malnutrition are prone to thiamine and vitamin B12 deficiencies, which can induce delirium. Laboratory assessment and consideration of supplementation is recommended. Despite high occurrence of delirium in hospitalized older adults with preexisting comorbid neurocognitive disorders, there is no standard care for delirium comorbid with another neurocognitive disorder.62 Clinical practice guidelines for older patients receiving palliative care have been developed63; the goal is to minimize suffering and discomfort in patients in palliative care.64

Post-delirium prophylaxis. Medications for delirium usually can be tapered and discontinued once the episode has resolved and the patient is stable; it is common to discontinue medications when the patient has been symptom-free for 1 week.65 Some patients (eg, with end-stage liver disease, disseminated cancer) are prone to recurrent or to prolonged or chronic delirium. A period of post-recovery treatment with antipsychotics—even indefinite treatment in some cases—should be considered.

Post-delirium debriefing and aftercare. The psychological complications of delirium are distressing for the patient and his (her) caregivers. Psychiatric complications associated with delirium, including acute stress disorder—which might predict posttraumatic stress disorder—have been explored; early recognition and treatment may improve long-term outcomes.66 After recovery from acute delirium, cognitive assessment (eg, MMSE67 or Montreal Cognitive Assessment68) is recommended to validate current cognitive status because patients may have persistent decrement in cognitive function compared with pre-delirium condition, even after recovery from the acute episode.

Post-delirium debriefing may help patients who have recovered from a delirium episode. Patients may fear that their brief period of hallucinations might represent the onset of a chronic-relapsing psychotic disorder. Allow patients to communicate their distress about the delirium episode and give them the opportunity to talk through the experience. Brief them on the possibility that delirium will recur and advise them to seek emergency medical care in case of recurrence. Advise patients to monitor and maintain a normal sleep-wake cycle.

Family members can watch for syndromal recurrence of delirium. They should be encouraged to discuss their reaction to having seen their relative in a delirious state.

Health care systems with integrated electronic medical records should list “delirium, resolved” on the patient’s illness profile or problem list and alert the patient’s primary care provider to the delirium history to avoid future exposure to delirium-provocative medications, and to prompt the provider to assume an active role in post-delirium care, including delirium recurrence surveillance, medication adjustment, risk factor management, and post-recovery cognitive assessment.

Bottom Line

Evaluation of delirium in geriatric patients includes clinical vigilance and screening, differentiating delirium from other neurocognitive disorders, and identifying and treating underlying causes. Perioperative use of antipsychotics may reduce the incidence of delirium, although hospital length of stay generally has not been reduced with prophylaxis. Management interventions include staff education, systematic screening, use of multicomponent interventions, and pharmacologic interventions.

Related Resources

• Downing LJ, Caprio TV, Lyness JM. Geriatric psychiatry review: differential diagnosis and treatment of the 3 D’s - delirium, dementia, and depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(6):365.

• Brooks PB. Postoperative delirium in elderly patients. Am J Nurs. 2012;112(9):38-49.

Drug Brand Names

Carbidopa/levodopa • Sinemet Midazolam • Versed

Dexmedetomidine • Precedex Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Haloperidol • Haldol Propofol • Diprivan

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Quetiapine • Seroquel

Lorazepam • Ativan Risperidone • Risperdal

Metoclopramide • Reglan Trazodone • Desyrel

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1993.

3. Lipowski ZJ. Delirium in the elderly patient. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(9):578-582.

4. Meagher DJ, Trzepacz PT. Motoric subtypes of delirium. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2000;5(2):75-85.

5. Rabinowitz T. Delirium: an important (but often unrecognized) clinical syndrome. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4(3):202-208.

6. Marcantonio ER, Ta T, Duthie E, et al. Delirium severity and psychomotor types: their relationship with outcomes after hip fracture repair. Am J Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(5):850-857.

7. Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703-2710.

8. Duppils GS, Wikblad K. Delirium: behavioural changes before and during the prodromal phase. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(5):609-616.

9. de Jonghe JF, Kalisvaart KJ, Dijkstra M, et al. Early symptoms in the prodromal phase of delirium: a prospective cohort study in elderly patients undergoing hip surgery. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(2):112-121.

10. Cook IA. Guideline watch: practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

11. Hogan D, Gage L, Bruto V, et al. National guidelines for seniors’ mental health: the assessment and treatment of delirium. Canadian Journal of Geriatrics. 2006;9(suppl 2):S42-51.

12. Leentjens AF, Diefenbacher A. A survey of delirium guidelines in Europe. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(1):123-128.

13. Tropea J, Slee JA, Brand CA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of delirium in older people in Australia. Australas J Ageing. 2008;27(3):150-156.

14. Mittal D, Majithia D, Kennedy R, et al. Differences in characteristics and outcome of delirium as based on referral patterns. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(5):367-375.

15. Grover S, Subodh BN, Avasthi A, et al. Prevalence and clinical profile of delirium: a study from a tertiary-care hospital in north India. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(1): 25-29.

16. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12): 941-948.

17. Strawn JR, Keck PE Jr, Caroff SN. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):870-876.

18. Dobmejer K. Delirium in elderly medical patients. Clinical Geriatrics. 1996;4:43-68.

19. Leentjens AF, Maclullich AM, Meagher DJ. Delirium, Cinderella no more...? J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(3):205.

20. Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210-220.

21. Streubel PN, Ricci WM, Gardner MJ. Fragility fractures: preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative management. Current Orthopaedic Practice. 2009;20(5):482-489.

22. Spronk PE, Riekerk B, Hofhuis J, et al. Occurrence of delirium is severely underestimated in the ICU during daily care. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(7):1276-1280.

23. Lawlor PG, Gagnon B, Mancini IL, et al. Occurrence, causes, and outcome of delirium in patients with advanced cancer: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):786-794.

24. Ganzini L. Care of patients with delirium at the end of life. Annals of Long-Term Care. 2007;15(3):35-40.

25. Bourne RS, Tahir TA, Borthwick M, et al. Drug treatment of delirium: past, present and future. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(3):273-282.

26. Yokota H, Ogawa S, Kurokawa A, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow in delirium patients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57(3):337-339.

27. Maldonado JR. Pathoetiological model of delirium: a comprehensive understanding of the neurobiology of delirium and an evidence-based approach to prevention and treatment. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24(4):789-856, ix.

28. Trzepacz PT. Is there a final common neural pathway in delirium? Focus on acetylcholine and dopamine. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2000;5(2):132-148.

29. Inouye SK. The dilemma of delirium: clinical and research controversies regarding diagnosis and evaluation of delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients. Am J Med. 1994;97(3):278-288.

30. Laurila JV, Laakkonen ML, Tilvis RS, et al. Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in a frail geriatric population. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(3):249-254.

31. Morandi A, McCurley J, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Tools to detect delirium superimposed on dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(11):2005-2013.

32. Kazmierski J, Kowman M, Banach M, et al. The use of DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria and diagnostic scales for delirium among cardiac surgery patients: results from the IPDACS study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010; 22(4):426-432.

33. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Roth A, et al. The Memorial Delirium Rating Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(3):128-137.

34. Wong CL, Holroyd-Leduc J, Simel DL, et al. Does this patient have delirium?: value of bedside instruments. JAMA. 2010;304(7):779-786.

35. Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, et al. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;49(5):516-522.

36. Lundström M, Edlund A, Karlsson S, et al. A multifactorial intervention program reduces the duration of delirium, length of hospitalization, and mortality in delirious patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):622-628.

37. Lundström M, Olofsson B, Stenvall M, et al. Postoperative delirium in old patients with femoral neck fracture: a randomized intervention study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007; 19(3):178-186.

38. Kratz A. Use of the acute confusion protocol: a research utilization project. J Nurs Care Qual. 2008;23(4):331-337.

39. Prakanrattana U, Prapaitrakool S. Efficacy of risperidone for prevention of postoperative delirium in cardiac surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35(5):714-719.

40. Kaneko T, Cai J, Ishikura T, et al. Prophylactic consecutive administration of haloperidol can reduce the occurrence of postoperative delirium in gastrointestinal surgery. Yonago Acta Medica. 1999;42:179-184.

41. Larsen KA, Kelly SE, Stern TA, et al. Administration of olanzapine to prevent postoperative delirium in elderly joint-replacement patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(5):409-418.

42. Kalisvaart KJ, de Jonghe JF, Bogaards MJ, et al. Haloperidol prophylaxis for elderly hip-surgery patients at risk for delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(10):1658-1666.

43. Hakim SM, Othman AI, Naoum DO. Early treatment with risperidone for subsyndromal delirium after on-pump cardiac surgery in the elderly: a randomized trial. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(5):987-997.

44. Maldonado JR, Wysong A, van der Starre PJ, et al. Dexmedetomidine and the reduction of postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(3): 206-217.

45. Short J. Use of dexmedetomidine for primary sedation in a general intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurse. 2010;30(1): 29-38; quiz 39.

46. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. American Psychiatric Association [Comment in: Treatment of patients with delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 2000.]. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(suppl 5):1-20.

47. Maldonado JR. Delirium in the acute care setting: characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24(4):657-722, vii.

48. Platt MM, Breitbart W, Smith M, et al. Efficacy of neuroleptics for hypoactive delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;6(1):66-67.

49. Lonergan E, Britton AM, Luxenberg J, et al. Antipsychotics for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005594.

50. Seitz DP, Gill SS, van Zyl LT. Antipsychotics in the treatment of delirium: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(1):11-21.

51. Breitbart W, Marotta R, Platt MM, et al. A double-blind trial of haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and lorazepam in the treatment of delirium in hospitalized AIDS patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(2):231-237.

52. Hu H, Deng W, Yang H, et al. Olanzapine and haloperidol for senile delirium: a randomized controlled observation. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation. 2006;10(42): 188-190.

53. Friedman JH, Fernandez HH. Atypical antipsychotics in Parkinson-sensitive populations. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2002;15(3):156-170.

54. Seitz DP, Gill SS. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome complicating antipsychotic treatment of delirium or agitation in medical and surgical patients: case reports and a review of the literature. Psychosomatics. 2009; 50(1):8-15.

55. Han CS, Kim YK. A double-blind trial of risperidone and haloperidol for the treatment of delirium. Psychosomatics. 2004;45(4):297-301.

56. Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence. JAMA. 2005;293(5):596-608.

57. Hermann N, Lanctôt KL. Atypical antipsychotics for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: malignant or maligned? Drug Saf. 2006;29(10):833-843.

58. Noyan MA, Elbi H, Aksu H. Donepezil for anticholinergic drug intoxication: a case report. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27(5):885-887.

59. Gleason OC. Donepezil for postoperative delirium. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(5):437-438.

60. Overshott R, Karim S, Burns A. Cholinesterase inhibitors for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1): CD005317.

61. Davis MP. Does trazodone have a role in palliating symptoms? Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(2):221-224.

62. Fick DM, Agostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002; 50(10):1723-1732.

63. Brajtman S, Wright D, Hogan D, et al. Developing guidelines for the assessment and treatment of delirium in older adults at the end of life. Can Geriatr J. 2011;14(2):40-50.

64. Caraceni A, Simonetti F. Palliating delirium in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(2):164-172.

65. Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, et al; Expert Consensus Panel for using Antipsychotic Drugs in Older Patients. Using antipsychotic agents in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 2):5-99; discussion 100-102; quiz 103-104.

66. Granja C, Gomes E, Amaro A, et al. Understanding posttraumatic stress disorder-related symptoms after critical care: the early illness amnesia hypothesis. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(10):2801-2809.

67. Ringdal GI, Ringdal K, Juliebø V, et al. Using the Mini- Mental State Examination to screen for delirium in elderly patients with hip fracture. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2011;32(6):394-400.

68. Olson RA, Chhanabhai T, McKenzie M. Feasibility study of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in patients with brain metastases. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(11):1273-1278.

Although delirium has many descriptive terms (Table 1), a common unifying term is “acute global cognitive dysfunction,” now recognized as delirium; a consensus supported by DSM-51 and ICD-102 (Table 2). According to DSM-5, the essential feature is a disturbance of attention or awareness that is accompanied by a change in baseline cognition that cannot be explained by another preexisting, established, or evolving neurocognitive disorder (the newly named DSM-5 entity for dementia syndromes).1 Because delirium affects the cortex diffusely, psychiatric symptoms can include cognitive, mood, anxiety, or psychotic symptoms. Because many systemic illnesses can induce delirium, the differential diagnosis spans all organ systems.

Three subtypes

Delirium can be classified, based on symptoms,3,4 into 3 subtypes: hyperactive-hyperalert, hypoactive-hypoalert, and mixed delirium. Hyperactive patients present with restlessness and agitation. Hypoactive patients are lethargic, confused, slow to respond to questions, and often appear depressed. The differential prognostic significance of these subtypes has been examined in the literature, with conflicting results. Rabinowitz5 reported that hypoactive delirium has the worst prognosis, while Marcantonio et al6 indicated that the hyperactive subtype is associated with the highest mortality rate. Mixed delirium, with periods of both hyperactivity and hypoactivity, is the most common type of delirium.7

A prodromal phase, characterized by anxiety, frequent requests for nursing and medical assistance, decreased attention, restlessness, vivid dreams, disorientation immediately after awakening, and hallucinations, can occur before an episode of full-spectrum delirium; this prodromal state often is identified retrospectively —after the patient is in an episode of delirium.8,9

Evidence-based guidelines aim to improve recognition and clinical management.10-13 Disruptive behavior is the main reason for psychiatric referral in delirium.14,15 Delayed psychiatric consultation because of non-recognition of delirium is related to variables such as older age; history of a pre-existing, comorbid neurocognitive disorder; and the clinical appearance of hypoactive delirium.14

The case of Mr. D (Box),16 illustrates how the emergence of antipsychotic-associated neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) can complicate antipsychotic treatment of delirium in a geriatric medical patient, although delirium also is a common presentation in NMS.17 Delirium developed after an increase in carbidopa/levodopa, which has central dopaminergic effects that can precipitate delirium, particularly in a geriatric patient with preexisting comorbid neurocognitive disorder. Further complicating Mr. D’s delirium presentation was the development of NMS, which had a multifactorial causation, such as the use of dopamine antagonists (ie, quetiapine, metoclopramide), and an abrupt decrease of a dopaminergic agent (ie, carbidopa/levodopa), all inducing a central dopamine relative hypoactivity.

Epidemiology

Delirium is more common in older patients,15 and is seen in 30% to 40% of hospitalized geriatric patients.18 Delirium in older patients, compared with other adults, is associated with more severe cognitive impairment.19 It is common among geriatric surgical patients (15% to 62%)20 with a peak 2 to 5 days postoperatively for hip fracture,21 and often is seen in ICU patients (70% to 87%).20 However, Spronk et al22 found that delirium is significantly under-recognized in the ICU. Nearly 90% of terminally ill patients become delirious before death.23 Terminal delirium often is unrecognized and can interfere with assessment of other clinical problems.24 A preexisting history of comorbid neurocognitive disorder was evident in as many as two-thirds of delirium cases.25

Pathophysiology and risk factors

The pathophysiology of delirium has been characterized as an imbalance of CNS metabolism, including decreased blood flow in various regions of the brain that may normalize once delirium resolves.26 Studies describe the simultaneous decrease of cholinergic transmission and dopaminergic excess.27,28 Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium that are of particular importance in geriatric patients include:

• advanced age

• CNS disease

• infection

• cognitive impairment

• male sex

• poor nutrition

• dehydration and other metabolic abnormalities

• cardiovascular events

• substance use

• medication

• sensory deprivation (eg, impaired vision or hearing)

• sleep deprivation

• low level of physical activity.27,29,30

Table 3 lists the most common delirium-provocative medications.27

Evaluation and psychometric scales

The EEG can be useful in evaluating delirium, especially in clinically ambiguous cases. EEG findings may indicate generalized slowing or dropout of the posterior dominant rhythm, and generalized slow theta and delta waves, findings that are more common in delirium than in other neurocognitive disorders and other psychiatric illnesses. The EEG must be interpreted in the context of the delirium diagnostic workup, because abnormalities seen in other neurocognitive disorders can overlap with those of delirium.31

The EEG referral should specify the clinical suspicion of delirium to help interpret the results. Delirium cases in which the patient’s previous cognitive status is unknown may benefit from EEG evaluation, such as:

• in possible status epilepticus

• when delirium improvement has reached a plateau at a lower level of cognitive function than before onset of delirium

• when the patient is unable or unwilling to complete a psychiatric interview.27

Assessment instruments are available to diagnose and monitor delirium (Table 4). Typically, delirium assessment includes examining levels of arousal, psychomotor activity, cognition (ie, orientation, attention, and memory), and perceptual disturbances.

Psychometrically, a review of Table 4 suggests that validity appeared stable with adequate specificity (64% to 99%) but more variable sensitivity (36% to 100%). These reliability parameters also will be affected by the classification system (ie, DSM vs ICD) and the cut-off score employed.32 Most measures (eg, Confusion Assessment Method [CAM], CAM-ICU) provide an adequate sample of behavioral (ie, level of alertness), motor (ie, psychomotor activity), and cognitive (ie, orientation, attention, memory, and receptive language) function, with the exception of the Global Attentiveness Rating, which is a 2-minute open conversation protocol between physician and patient.

Some measures are stand-alone instruments, such as the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale, whereas the CAM requires administration of separate cognitive screens, including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Digit Span.33 Instruments to detect delirium in critically ill patients are a more recent development. Wong et al34 reported that the most widely studied tool was the CAM. Obtaining collateral information from family, caregivers, and hospital staff is essential, particularly given the fluctuating nature of delirium.

Management

Prevention. Identify patients at high risk of delirium so that preventive strategies can be employed. Multi-component, nonpharmacotherapeutic interventions are used in clinical settings but few randomized trials have been conducted. The contributing effectiveness of individual components is not well-studied, but most include staff education to increase awareness of delirium. Of 3 multi-component intervention randomized trials, 2 reported a significantly lower incidence of delirium in the intervention group.35-37 Implementation of a multi-component protocol in medical/ surgical units was associated with a significant reduction in use of restraints.38

As in Mr. D’s case, complex drug regimens, particularly for CNS illness, can increase the risk of delirium. Considering the medication profile for patients with complex systemic illness—in particular, minimizing the use anticholinergics and dopamine agonists— may be crucial in preventing delirium.

Prophylactic administration of antipsychotics may reduce the risk of developing postoperative delirium.39 Studies of the use of these agents were characterized by small sample sizes and selected groups of patient populations. Of the 4 randomized studies evaluating prophylactic antipsychotics (vs placebo), 3 found a lower incidence of delirium in the intervention groups.39-41

A study of haloperidol in post-GI surgery patients showed a reduced occurrence of delirium,40 whereas its prophylactic use in patients undergoing hip surgery42 did not reduce the incidence of delirium compared with placebo, but did decrease severity when delirium occurred.42

Risperidone39 in post-cardiac surgery and olanzapine41 perioperatively in patients undergoing total knee or hip replacement have been shown to decrease delirium severity and duration. Targeted prophylaxis with risperidone43 in post-cardiac surgery patients who showed disturbed cognition but did not meet criteria for delirium reduced the number of patients requiring medication, compared with placebo.43

Dexmedetomidine, an α-2 adrenergic receptor agonist, compared with propofol or midazolam in post-cardiac valve surgery patients, resulted in a decreased incidence of delirium but no difference in delirium duration, hospital length of stay, or use of other medications.44 However, other studies have shown that dexmedetomidine reduces ICU length of stay and duration of mechanical ventilation.45

Treatment. Management of hospitalized medically ill geriatric patients with delirium is challenging and requires a comprehensive approach. The first step in delirium management is prompt identification and management of systemic medical disturbances associated with the delirium episode. First-line, nonpharmacotherapeutic strategies for patients with delirium include:

• reorientation

• behavioral interventions (eg, use of clear instructions and frequent eye contact with patients)

• environmental interventions (eg, minimal noise, adequate lighting, and limited room and staff changes)

• avoidance of physical restraints.46

Consider employing family members or hospital staff sitters to stay with the patient and to reassure, reorient, and watch for agitation and other unsafe behaviors (eg, attempted elopement). Psychoeducation for the patient and family on the phenomenology of delirium can be helpful.

The use of drug treatment strategies should be integrated into a comprehensive approach that includes the routine use of nondrug measures.46 Using medications for treating hypoactive delirium, formerly controversial, now has wider acceptance.47,48 A few high-quality randomized trials have been performed.25,49,50

Pharmacotherapy, especially in frail patients, should be initiated at the lowest starting dosage and titrated cautiously to clinical effect and for the shortest period of time necessary. Antipsychotics are preferred agents for treating all subtypes of delirium; haloperidol is widely used.46,51,52 However, antipsychotics, including haloperidol, can be associated with adverse neurologic effects such as extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and NMS.

Although reported less frequently than with haloperidol, other agents have been implicated in development of EPS and NMS, including atypical antipsychotics and antiemetic dopamine antagonists, particularly in parkinsonism-prone patients.53 Strategies that can minimize such risks in geriatric inpatients with delirium include oral, rather than parenteral, use of antipsychotics—preferential use of atypical over typical antipsychotics— and lowest effective dosages.54

In controlled trials, atypical antipsychotics for delirium showed efficacy compared with haloperidol.52,55 However, there is no research that demonstrates any advantage of one atypical over another.25

In Mr. D’s case, the most important intervention for managing delirium caused by NMS is to discontinue all dopamine antagonists and treat agitation with judicious doses of a benzodiazepine, with supportive care.17 In cases of sudden discontinuation or a dosage decrease of dopamine agonists, these medications should be resumed or optimized to minimize the risk of NMS-associated rhabdomyolysis and subsequent renal failure.17 Antipsychotics carry an increased risk of stroke and mortality in older patients with established or evolving neurocognitive disorders56,57 and can cause prolongation of the QTc interval.57

Other medications that could be used for delirium include cholinesterase inhibitors58,59 (although larger trials and a systematic review did not support this use60), and 5-HT receptor antagonists,61 such as trazodone. Benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam, are first-line treatment for delirium associated with seizures or withdrawal from alcohol, sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics and for delirium caused by NMS. Be cautious about using benzodiazepines in geriatric patients because of a risk of respiratory depression, falls, sedation, and amnesia.

Geriatric patients with alcoholism and those with malnutrition are prone to thiamine and vitamin B12 deficiencies, which can induce delirium. Laboratory assessment and consideration of supplementation is recommended. Despite high occurrence of delirium in hospitalized older adults with preexisting comorbid neurocognitive disorders, there is no standard care for delirium comorbid with another neurocognitive disorder.62 Clinical practice guidelines for older patients receiving palliative care have been developed63; the goal is to minimize suffering and discomfort in patients in palliative care.64

Post-delirium prophylaxis. Medications for delirium usually can be tapered and discontinued once the episode has resolved and the patient is stable; it is common to discontinue medications when the patient has been symptom-free for 1 week.65 Some patients (eg, with end-stage liver disease, disseminated cancer) are prone to recurrent or to prolonged or chronic delirium. A period of post-recovery treatment with antipsychotics—even indefinite treatment in some cases—should be considered.

Post-delirium debriefing and aftercare. The psychological complications of delirium are distressing for the patient and his (her) caregivers. Psychiatric complications associated with delirium, including acute stress disorder—which might predict posttraumatic stress disorder—have been explored; early recognition and treatment may improve long-term outcomes.66 After recovery from acute delirium, cognitive assessment (eg, MMSE67 or Montreal Cognitive Assessment68) is recommended to validate current cognitive status because patients may have persistent decrement in cognitive function compared with pre-delirium condition, even after recovery from the acute episode.

Post-delirium debriefing may help patients who have recovered from a delirium episode. Patients may fear that their brief period of hallucinations might represent the onset of a chronic-relapsing psychotic disorder. Allow patients to communicate their distress about the delirium episode and give them the opportunity to talk through the experience. Brief them on the possibility that delirium will recur and advise them to seek emergency medical care in case of recurrence. Advise patients to monitor and maintain a normal sleep-wake cycle.

Family members can watch for syndromal recurrence of delirium. They should be encouraged to discuss their reaction to having seen their relative in a delirious state.

Health care systems with integrated electronic medical records should list “delirium, resolved” on the patient’s illness profile or problem list and alert the patient’s primary care provider to the delirium history to avoid future exposure to delirium-provocative medications, and to prompt the provider to assume an active role in post-delirium care, including delirium recurrence surveillance, medication adjustment, risk factor management, and post-recovery cognitive assessment.

Bottom Line

Evaluation of delirium in geriatric patients includes clinical vigilance and screening, differentiating delirium from other neurocognitive disorders, and identifying and treating underlying causes. Perioperative use of antipsychotics may reduce the incidence of delirium, although hospital length of stay generally has not been reduced with prophylaxis. Management interventions include staff education, systematic screening, use of multicomponent interventions, and pharmacologic interventions.

Related Resources

• Downing LJ, Caprio TV, Lyness JM. Geriatric psychiatry review: differential diagnosis and treatment of the 3 D’s - delirium, dementia, and depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(6):365.

• Brooks PB. Postoperative delirium in elderly patients. Am J Nurs. 2012;112(9):38-49.

Drug Brand Names

Carbidopa/levodopa • Sinemet Midazolam • Versed

Dexmedetomidine • Precedex Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Haloperidol • Haldol Propofol • Diprivan

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Quetiapine • Seroquel

Lorazepam • Ativan Risperidone • Risperdal

Metoclopramide • Reglan Trazodone • Desyrel

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Although delirium has many descriptive terms (Table 1), a common unifying term is “acute global cognitive dysfunction,” now recognized as delirium; a consensus supported by DSM-51 and ICD-102 (Table 2). According to DSM-5, the essential feature is a disturbance of attention or awareness that is accompanied by a change in baseline cognition that cannot be explained by another preexisting, established, or evolving neurocognitive disorder (the newly named DSM-5 entity for dementia syndromes).1 Because delirium affects the cortex diffusely, psychiatric symptoms can include cognitive, mood, anxiety, or psychotic symptoms. Because many systemic illnesses can induce delirium, the differential diagnosis spans all organ systems.

Three subtypes

Delirium can be classified, based on symptoms,3,4 into 3 subtypes: hyperactive-hyperalert, hypoactive-hypoalert, and mixed delirium. Hyperactive patients present with restlessness and agitation. Hypoactive patients are lethargic, confused, slow to respond to questions, and often appear depressed. The differential prognostic significance of these subtypes has been examined in the literature, with conflicting results. Rabinowitz5 reported that hypoactive delirium has the worst prognosis, while Marcantonio et al6 indicated that the hyperactive subtype is associated with the highest mortality rate. Mixed delirium, with periods of both hyperactivity and hypoactivity, is the most common type of delirium.7

A prodromal phase, characterized by anxiety, frequent requests for nursing and medical assistance, decreased attention, restlessness, vivid dreams, disorientation immediately after awakening, and hallucinations, can occur before an episode of full-spectrum delirium; this prodromal state often is identified retrospectively —after the patient is in an episode of delirium.8,9

Evidence-based guidelines aim to improve recognition and clinical management.10-13 Disruptive behavior is the main reason for psychiatric referral in delirium.14,15 Delayed psychiatric consultation because of non-recognition of delirium is related to variables such as older age; history of a pre-existing, comorbid neurocognitive disorder; and the clinical appearance of hypoactive delirium.14

The case of Mr. D (Box),16 illustrates how the emergence of antipsychotic-associated neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) can complicate antipsychotic treatment of delirium in a geriatric medical patient, although delirium also is a common presentation in NMS.17 Delirium developed after an increase in carbidopa/levodopa, which has central dopaminergic effects that can precipitate delirium, particularly in a geriatric patient with preexisting comorbid neurocognitive disorder. Further complicating Mr. D’s delirium presentation was the development of NMS, which had a multifactorial causation, such as the use of dopamine antagonists (ie, quetiapine, metoclopramide), and an abrupt decrease of a dopaminergic agent (ie, carbidopa/levodopa), all inducing a central dopamine relative hypoactivity.

Epidemiology

Delirium is more common in older patients,15 and is seen in 30% to 40% of hospitalized geriatric patients.18 Delirium in older patients, compared with other adults, is associated with more severe cognitive impairment.19 It is common among geriatric surgical patients (15% to 62%)20 with a peak 2 to 5 days postoperatively for hip fracture,21 and often is seen in ICU patients (70% to 87%).20 However, Spronk et al22 found that delirium is significantly under-recognized in the ICU. Nearly 90% of terminally ill patients become delirious before death.23 Terminal delirium often is unrecognized and can interfere with assessment of other clinical problems.24 A preexisting history of comorbid neurocognitive disorder was evident in as many as two-thirds of delirium cases.25

Pathophysiology and risk factors

The pathophysiology of delirium has been characterized as an imbalance of CNS metabolism, including decreased blood flow in various regions of the brain that may normalize once delirium resolves.26 Studies describe the simultaneous decrease of cholinergic transmission and dopaminergic excess.27,28 Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium that are of particular importance in geriatric patients include:

• advanced age

• CNS disease

• infection

• cognitive impairment

• male sex

• poor nutrition

• dehydration and other metabolic abnormalities

• cardiovascular events

• substance use

• medication

• sensory deprivation (eg, impaired vision or hearing)

• sleep deprivation

• low level of physical activity.27,29,30

Table 3 lists the most common delirium-provocative medications.27

Evaluation and psychometric scales

The EEG can be useful in evaluating delirium, especially in clinically ambiguous cases. EEG findings may indicate generalized slowing or dropout of the posterior dominant rhythm, and generalized slow theta and delta waves, findings that are more common in delirium than in other neurocognitive disorders and other psychiatric illnesses. The EEG must be interpreted in the context of the delirium diagnostic workup, because abnormalities seen in other neurocognitive disorders can overlap with those of delirium.31

The EEG referral should specify the clinical suspicion of delirium to help interpret the results. Delirium cases in which the patient’s previous cognitive status is unknown may benefit from EEG evaluation, such as:

• in possible status epilepticus

• when delirium improvement has reached a plateau at a lower level of cognitive function than before onset of delirium

• when the patient is unable or unwilling to complete a psychiatric interview.27

Assessment instruments are available to diagnose and monitor delirium (Table 4). Typically, delirium assessment includes examining levels of arousal, psychomotor activity, cognition (ie, orientation, attention, and memory), and perceptual disturbances.

Psychometrically, a review of Table 4 suggests that validity appeared stable with adequate specificity (64% to 99%) but more variable sensitivity (36% to 100%). These reliability parameters also will be affected by the classification system (ie, DSM vs ICD) and the cut-off score employed.32 Most measures (eg, Confusion Assessment Method [CAM], CAM-ICU) provide an adequate sample of behavioral (ie, level of alertness), motor (ie, psychomotor activity), and cognitive (ie, orientation, attention, memory, and receptive language) function, with the exception of the Global Attentiveness Rating, which is a 2-minute open conversation protocol between physician and patient.

Some measures are stand-alone instruments, such as the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale, whereas the CAM requires administration of separate cognitive screens, including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Digit Span.33 Instruments to detect delirium in critically ill patients are a more recent development. Wong et al34 reported that the most widely studied tool was the CAM. Obtaining collateral information from family, caregivers, and hospital staff is essential, particularly given the fluctuating nature of delirium.

Management