User login

Many mental health practitioners have had training in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)—short-term, evidence-based psychotherapy for treating a variety of psychiatric conditions (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder) and medical comorbidities (eg, insomnia)—but only some are knowledgeable about how to best use CBT with a suicidal patient. This article provides a clinician-friendly summary of a 10-session evidence-based outpatient1-3 and an adapted 6 to 8 session inpatient4,5 cognitive-behavioral protocol (known as Post-Admission Cognitive Therapy [PACT]) that is designed to help patients who have suicide-related thoughts and/or behaviors.

3 phases of CBT for suicide prevention

An average of 9 hours of individual CBT for the prevention of suicide has been reported to reduce the likelihood of repeat suicide attempts in approximately 50% of patients.1 Here, we introduce you to 3 phases of CBT for preventing suicide—phases that are the same for outpatients or inpatients. Our aim is to help you become familiar with CBT strategies that can be adapted for your treatment setting and used to intervene with vulnerable patients who are at risk for suicidal self-directed violence. A thorough assessment of the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis and history, presenting problems, and risk and protective factors for suicide must be completed before treatment begins.

Phase I. The patient is asked to tell a story associated with his (her) most recent episode of suicidal thoughts or behavior, or both. This narrative serves as 1) a foundation for planning treatment and 2) a model for understanding how best to deactivate the wish to die through the process of psychotherapy.

Phase II. The patient is assisted with modifying underdeveloped or overdeveloped skills that are most closely associated with the risk of triggering a suicidal crisis. For example, a patient with underdeveloped skills in regulating anger and hatred toward himself is taught to modulate these problematic emotions more effectively. In addition, effective problem-solving strategies are reviewed and practiced.

Phase III. The patient is guided through a relapse prevention task. The purpose of this exercise is to 1) highlight skills learned during therapy and 2) allow the patient to practice effective problem-solving strategies that are aimed at minimizing the recurrence of suicidal self-directed violence.

Theorectical basis for preventing suicide with CBT

Aaron Beck, in 1979,6 proposed that a person’s biopsychosocial vulnerabilities can interact with suicidal thoughts and behaviors to produce a state that Beck labeled the “suicide mode.” Once produced, a suicide mode can become activated by cognitive, affective, motivational, and behavioral systems.

The frequency and severity of suicide mode activation can increase over time, especially for persons who do not have protective factors and those who have a history of self-directed violence—in particular, attempted suicide. Moreover, some persons might experience a chronic state of suicide mode activation and, therefore, remain at elevated risk of suicide. Once a suicide-specific mode is activated, the person considers suicide the only option for solving his life problems. Suicide might be considered a rational decision at this point.6

The hypothesized mechanism of action associated with CBT for preventing suicide can be described as:

• deactivation of the suicide mode

• modification of the structure and content of the suicide mode

• construction and practice of more adaptive structural modes to promote a desire to live.

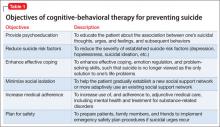

The underlying philosophy of this intervention is that the suicide mode occurs independently of psychiatric diagnoses and must be targeted directly; treatment therefore is transdiagnostic.7 In other words, instead of addressing a symptom of a psychiatric disorder, treatment directly targets suicide-related ideation and behaviors (Table 1).

Using that framework, psychiatric diagnoses are conceptualized in terms of how the associated symptoms contribute to the activation, maintenance, and exacerbation of the suicide mode.

Protocol for preventing suicide

The outpatient protocol1-3 comprises 10, 45- to 50-minute weekly individual psychotherapy sessions, with an allowance for booster sessions (as needed), until the patient is able to complete the relapse prevention task in Phase III. The inpatient protocol4,5 comprises 6, 90-minute individual psychotherapy sessions, with an allowance for 2 booster sessions (as needed) during the inpatient stay and as many as 4 telephone booster sessions after discharge.

Phase I: Tell the suicide story

Engage the patient in treatment. To increase adherence to treatment and minimize the risk of drop-out, practitioners are encouraged to establish a strong, early therapeutic alliance with the patient. Showing genuine empathy and providing a safe, supportive, and nonjudgmental environment are instrumental for engaging patients in treatment. The practitioner listens carefully to the patient’s narrative, provides periodic summaries to check on accurate understanding, and keeps interruptions to a minimum.

Collaboratively generate a safety plan. A crisis response plan or safety plan—an individualized, hierarchically arranged, written list of coping strategies to be implemented during a suicide crisis—is developed as soon as possible. Guidance on how to develop a structured safety plan has been provided by Stanley and Brown.8,9

Practitioners must ensure that the safety plan contains contact information that the patient can use to reach the practitioner, the clinic, the on-call provider (if available), the local 24-hour emergency department, and the 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (800-273-TALK [8255]). Discussion of how to limit access to lethal means also is important.

Because safety planning is a collaborative process, it is imperative that practitioners check on the patient’s willingness to follow the safety plan and help him overcome perceived obstacles in implementation. Copies of the plan can be kept at different locations and shared with family members, friends, or both with the patient’s permission.

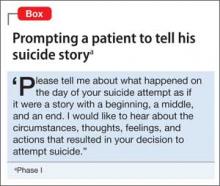

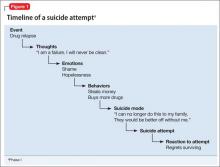

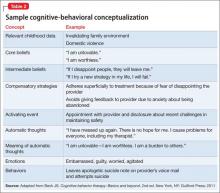

Develop a cognitive-behavioral conceptualization. The cognitive-behavioral conceptualization is an individualized map of a patient’s automatic thoughts (eg, “I am going to get fired today”), conditional assumptions (“If I get fired, then my life is over”), and core beliefs (“I am an utter failure”) that are activated before, during, and after suicidal self-directed violence. To develop that conceptualization, the patient is asked to tell a story about his (her) most recent suicidal crisis (the Box, offers a sample script) and to describe reactions to having survived a suicide attempt. (Note: Patients who report regret after an attempt are at greatest risk for dying by suicide.10)

This activity gives the patient an opportunity to disclose details surrounding his suicidal thoughts and actions, and might allow for a cathartic experience through storytelling. As practitioners listen to the suicide narrative, they collect data on the patient’s early childhood experiences (typically, suicide-activating events), associated automatic thoughts and images, emotional responses, and subsequent behaviors.

Based on this information, a cognitive-behavioral case conceptualization diagram (Figure 1, and Table 2) is generated collaboratively with the patienta and used to personalize treatment planning.

a Judith Beck offers sample case conceptualization diagrams in Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond, 2nd ed. New York, New York: Guilford Press; 2011.

Phase II: Build skills

Build skills to prevent episodes of suicidal self-directed violence. Information obtained from the conceptualization is used to generate an individualized cognitive-behavioral plan of intervention. The overall goal is to determine skill-based problem areas that are associated with the most recent episode of suicidal self-directed violence.

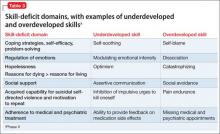

Practitioner and patient collaboratively identify skills that are underdeveloped and ones that are overdeveloped so that they can be addressed systematically. In general, based on our clinical experience with suicidal patients, we recommend focusing on skills captured within ≥1 of the deficit domains in Table 3. Explanation of the various cognitive-behavioral strategies used in this phase of treatment is beyond the scope of this article, but 2 activities that highlight the clinical work conducted in this phase are described in the following sections. We selected those activities because they are easy to implement and, we have found, receive overall patient acceptability.

For a detailed understanding of strategies used in Phase II of CBT for preventing suicide, see Related Resources. In addition, the book Choosing to live: How to defeat suicide through cognitive therapy11 can serve as a self-help guide for patients to follow through with CBT skill-building strategies.

Sample activity #1: Construct a ‘hope box.’ One activity that you can use to help a patient cope with suicide-activating core beliefs (eg, “My life is worthless”) involves construction of a so-called hope box. The box helps the patient directly challenge his extreme distress, by being reminded of previous successes, positive experiences, and reasons for living. The process of constructing a hope box allows the patient to work on modifying his problematic core beliefs (eg, worthlessness, helplessness, incapable of being loved).

It can be helpful to have the patient construct his hope box during a session, to ensure that everything that is put in the box is truly helpful and personalized. Items included vary from patient to patient, and might consist of pictures of loved ones, a favorite poem, a prayer, coping cards (see next section), or all of these. For example, one of our patients chose to include a picture of herself in her early 20s as a reminder of a positive, fulfilling time in her life; this gave her hope that it is possible to experience those feelings again.

Bush et alb at the National Center for Telehealth and Technology have developed a Virtual Hope Box, a free mobile application for tablets and smartphones (compatible with Android and iOS operating systems) that patients can use under the guidance of their practitioner.

bwww.t2.health.mil/apps/virtual-hope-box

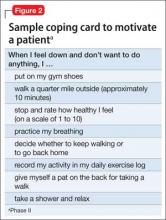

Sample activity #2: Generate coping cards. Effective problem-solving skills can be promoted by having the patient construct coping cards —wallet-size cards generated collaboratively in session. Coping cards are note cards that a patient keeps nearby to cope better during a difficult situation. They provide an easily accessible way to jump-start adaptive thinking during a suicidal crisis. The patient is encouraged to use coping cards to practice adaptive thinking even when not in a crisis.

There are 3 kinds of coping cards:

• place a suicide-relevant automatic thought or core belief on one side of the card; on the other side, place an alternative, more adaptive response

• write a list of coping strategies

• write instructions to motivate or “activate” the patient toward completing a specific goal (Figure 2).

Phase III: Prevent relapse

Complete relapse prevention task. Relapse prevention is a common CBT strategy that aims to strengthen self-management to minimize likelihood of returning to a previously stopped behavior. For patients who present only with suicidal thoughts, relapse prevention is directed at identifying triggers and minimizing the occurrence and/ or intensity of such thoughts in the future. For patients who present with suicidal self-directed violence, relapse prevention is directed at identifying triggers for suicidal actions and reducing the likelihood of acting on suicidal urges. The brief guidance provided below will familiarize you with each of the relapse prevention steps, which may be completed in multiple sessions.

Step 1: Provide psychoeducation

Explain the difference between a lapse and a relapse. In general, you want the patient to understand that, although suicidal thoughts might persist and recur over time, suicidal self-directed violence must be prevented. Describe the purpose of the relapse prevention task (ie, to minimize the chance that suicidal thinking and actions will recur); address questions and concerns; and obtain permission to begin the procedure. Assure the patient that this is a collaborative activity and you will be in the room to ensure comfort and safety.

STEP 2: Retell the suicide story

Ask the patient to imagine the chain of events, thoughts, and feelings that led to the most recent episode of suicide ideation or suicidal self-directed violence. Tell the patient that you want him to construct a movie script to describe the chain of events that resulted in the suicide crisis —but to do so slowly, taking enough time to describe the details of each scene of the movie.

Step 3: Apply CBT skills

Ask the patient again to take you through the sequence of events leading to the most recent episode of suicide ideation or suicidal self-directed violence. This time, however, direct him to use the skills learned in therapy to appropriately respond cognitively, affectively, and behaviorally to move further away from the suicide outcome.

If the patient is moving too fast or neglecting important points, stop and ask about alternative ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving. Use as much time as needed until the patient is able to demonstrate solid learning of at least several learned CBT strategies to prevent suicidal self-directed violence.

Step 4: Generalize learning to prepare for future suicidal crises

In this stage —given your knowledge of the patient’s psychosocial history, cognitive- behavioral conceptualization, and suicide mode triggers —you collaboratively create a future scenario that is likely to activate suicidal self-directed violence. Question the patient about possible coping strategies, provide helpful feedback, guide him through each link in the chain of events, and propose additional alternative strategies if he is clearly neglecting important points of the intervention.

Step 5: Debrief and summarize lessons learned

Debrief the patient by providing a summary of the skills he has learned in therapy, congratulate him for completing this final therapeutic task, and assess overall emotional reaction to this activity. Remind him that mood fluctuations and future setbacks, in the form of lapses, are expected. Give him the option to request booster sessions and make plans for next steps in accomplishing general goals of therapy.

Treatment can be terminated when the patient is able to complete the relapse prevention task. If he is not ready or able to complete this exercise successfully, you can extend treatment. The duration of the extension is left to the practitioner’s judgment, based on the overall treatment plan. Brown and colleagues2 have reported a maximum number of 24 outpatient sessions (for patients who need additional booster sessions); based on clinical experience, it is reasonable to assume that it would be highly unlikely for a patient not to meet treatment objectives after a methodical course of outpatient CBT.

In cases in which goals of treatment have not been met, consultation with colleagues, review of adherence problems, and consideration of obstacles for treatment efficacy would be recommended.

A checklist can be used to determine whether a patient is ready to end treatment. Variables that can be considered in assessing readiness for termination include:

• reduced scores on self-report measures for a number of weeks

• evidence of enhanced problem-solving

• engagement in adjunctive health care services

• development of a social support system.

Post-Admission Cognitive Therapy (PACT)

An inpatient cognitive-behavioral protocol for the prevention of suicide, adapted from the efficacious outpatient model, is being evaluated at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland, and Fort Belvoir Community Hospital, Fort Belvoir, Virginia. The inpatient intervention is called PACT; components are summarized in Table 4.

Bottom Line

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for preventing suicide is an efficacious protocol for reducing the recurrence of suicidal self-directed violence. Post-Admission Cognitive Therapy is the adapted inpatient treatment package. You are encouraged to gain additional training and supervision on the delivery of these interventions to your high-risk suicidal patients.

Related Resources

• Academy of Cognitive Therapy. www.academyofct.org.

• National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. www.suicide preventionlifeline.org.

• Wenzel A, Brown GK, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for suicidal patients: scientific and clinical applications. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009.

Disclosures

Support for research on inpatient cognitive-behavioral therapy for the prevention of suicide provided to Principal Investigator, Dr. Ghahramanlou-Holloway by the Department of Defense, Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (W81XWH-08-2-0172), Military Operational Medicine Research Program (W81XWH-11-2-0106), and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (15219).

1. Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(5):563-570.

2. Brown GK, Henriques GR, Ratto C, et al. Cognitive therapy treatment manual for suicide attempters. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania; 2002 (unpublished).

3. Berk MS, Henriques GR, Warman DM, et al. A cognitive therapy intervention for suicide attempters: an overview of the treatment and case examples. Cogn Behav Pract. 2004;11(3):265-277.

4. Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, Cox D, Greene F. Post-admission cognitive therapy: a brief intervention for psychiatric inpatients admitted after a suicide attempt. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):233-244.

5. Neely L, Irwin K, Carreno Ponce JT, et al. Post Admission Cognitive Therapy (PACT) for the prevention of suicide in military personnel with histories of trauma: treatment development and case example. Clinical Case Studies. 2013;12(6):457-473.

6. Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York, NY: Penguin Group; 1979.

7. Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, Brown GK, Beck AT. Suicide. In: Whisman M, ed. Adapting cognitive therapy for depression: managing complexity and comorbidity. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008:159-184.

8. Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety planning intervention: a brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):256-264.

9. Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety plan treatment manual to reduce suicide risk: veteran version. http://www. mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/va_safety_planning_manual. pdf. Published August 20, 2008. Accessed July 2, 2014.

10. Henriques G, Wenzel A, Brown GK, et al. Suicide attempters’ reaction to survival as a risk factor for eventual suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(11):2180-2182.

11. Ellis TE, Newman CF. Choosing to live: How to defeat suicide through cognitive therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc; 1996.

Many mental health practitioners have had training in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)—short-term, evidence-based psychotherapy for treating a variety of psychiatric conditions (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder) and medical comorbidities (eg, insomnia)—but only some are knowledgeable about how to best use CBT with a suicidal patient. This article provides a clinician-friendly summary of a 10-session evidence-based outpatient1-3 and an adapted 6 to 8 session inpatient4,5 cognitive-behavioral protocol (known as Post-Admission Cognitive Therapy [PACT]) that is designed to help patients who have suicide-related thoughts and/or behaviors.

3 phases of CBT for suicide prevention

An average of 9 hours of individual CBT for the prevention of suicide has been reported to reduce the likelihood of repeat suicide attempts in approximately 50% of patients.1 Here, we introduce you to 3 phases of CBT for preventing suicide—phases that are the same for outpatients or inpatients. Our aim is to help you become familiar with CBT strategies that can be adapted for your treatment setting and used to intervene with vulnerable patients who are at risk for suicidal self-directed violence. A thorough assessment of the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis and history, presenting problems, and risk and protective factors for suicide must be completed before treatment begins.

Phase I. The patient is asked to tell a story associated with his (her) most recent episode of suicidal thoughts or behavior, or both. This narrative serves as 1) a foundation for planning treatment and 2) a model for understanding how best to deactivate the wish to die through the process of psychotherapy.

Phase II. The patient is assisted with modifying underdeveloped or overdeveloped skills that are most closely associated with the risk of triggering a suicidal crisis. For example, a patient with underdeveloped skills in regulating anger and hatred toward himself is taught to modulate these problematic emotions more effectively. In addition, effective problem-solving strategies are reviewed and practiced.

Phase III. The patient is guided through a relapse prevention task. The purpose of this exercise is to 1) highlight skills learned during therapy and 2) allow the patient to practice effective problem-solving strategies that are aimed at minimizing the recurrence of suicidal self-directed violence.

Theorectical basis for preventing suicide with CBT

Aaron Beck, in 1979,6 proposed that a person’s biopsychosocial vulnerabilities can interact with suicidal thoughts and behaviors to produce a state that Beck labeled the “suicide mode.” Once produced, a suicide mode can become activated by cognitive, affective, motivational, and behavioral systems.

The frequency and severity of suicide mode activation can increase over time, especially for persons who do not have protective factors and those who have a history of self-directed violence—in particular, attempted suicide. Moreover, some persons might experience a chronic state of suicide mode activation and, therefore, remain at elevated risk of suicide. Once a suicide-specific mode is activated, the person considers suicide the only option for solving his life problems. Suicide might be considered a rational decision at this point.6

The hypothesized mechanism of action associated with CBT for preventing suicide can be described as:

• deactivation of the suicide mode

• modification of the structure and content of the suicide mode

• construction and practice of more adaptive structural modes to promote a desire to live.

The underlying philosophy of this intervention is that the suicide mode occurs independently of psychiatric diagnoses and must be targeted directly; treatment therefore is transdiagnostic.7 In other words, instead of addressing a symptom of a psychiatric disorder, treatment directly targets suicide-related ideation and behaviors (Table 1).

Using that framework, psychiatric diagnoses are conceptualized in terms of how the associated symptoms contribute to the activation, maintenance, and exacerbation of the suicide mode.

Protocol for preventing suicide

The outpatient protocol1-3 comprises 10, 45- to 50-minute weekly individual psychotherapy sessions, with an allowance for booster sessions (as needed), until the patient is able to complete the relapse prevention task in Phase III. The inpatient protocol4,5 comprises 6, 90-minute individual psychotherapy sessions, with an allowance for 2 booster sessions (as needed) during the inpatient stay and as many as 4 telephone booster sessions after discharge.

Phase I: Tell the suicide story

Engage the patient in treatment. To increase adherence to treatment and minimize the risk of drop-out, practitioners are encouraged to establish a strong, early therapeutic alliance with the patient. Showing genuine empathy and providing a safe, supportive, and nonjudgmental environment are instrumental for engaging patients in treatment. The practitioner listens carefully to the patient’s narrative, provides periodic summaries to check on accurate understanding, and keeps interruptions to a minimum.

Collaboratively generate a safety plan. A crisis response plan or safety plan—an individualized, hierarchically arranged, written list of coping strategies to be implemented during a suicide crisis—is developed as soon as possible. Guidance on how to develop a structured safety plan has been provided by Stanley and Brown.8,9

Practitioners must ensure that the safety plan contains contact information that the patient can use to reach the practitioner, the clinic, the on-call provider (if available), the local 24-hour emergency department, and the 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (800-273-TALK [8255]). Discussion of how to limit access to lethal means also is important.

Because safety planning is a collaborative process, it is imperative that practitioners check on the patient’s willingness to follow the safety plan and help him overcome perceived obstacles in implementation. Copies of the plan can be kept at different locations and shared with family members, friends, or both with the patient’s permission.

Develop a cognitive-behavioral conceptualization. The cognitive-behavioral conceptualization is an individualized map of a patient’s automatic thoughts (eg, “I am going to get fired today”), conditional assumptions (“If I get fired, then my life is over”), and core beliefs (“I am an utter failure”) that are activated before, during, and after suicidal self-directed violence. To develop that conceptualization, the patient is asked to tell a story about his (her) most recent suicidal crisis (the Box, offers a sample script) and to describe reactions to having survived a suicide attempt. (Note: Patients who report regret after an attempt are at greatest risk for dying by suicide.10)

This activity gives the patient an opportunity to disclose details surrounding his suicidal thoughts and actions, and might allow for a cathartic experience through storytelling. As practitioners listen to the suicide narrative, they collect data on the patient’s early childhood experiences (typically, suicide-activating events), associated automatic thoughts and images, emotional responses, and subsequent behaviors.

Based on this information, a cognitive-behavioral case conceptualization diagram (Figure 1, and Table 2) is generated collaboratively with the patienta and used to personalize treatment planning.

a Judith Beck offers sample case conceptualization diagrams in Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond, 2nd ed. New York, New York: Guilford Press; 2011.

Phase II: Build skills

Build skills to prevent episodes of suicidal self-directed violence. Information obtained from the conceptualization is used to generate an individualized cognitive-behavioral plan of intervention. The overall goal is to determine skill-based problem areas that are associated with the most recent episode of suicidal self-directed violence.

Practitioner and patient collaboratively identify skills that are underdeveloped and ones that are overdeveloped so that they can be addressed systematically. In general, based on our clinical experience with suicidal patients, we recommend focusing on skills captured within ≥1 of the deficit domains in Table 3. Explanation of the various cognitive-behavioral strategies used in this phase of treatment is beyond the scope of this article, but 2 activities that highlight the clinical work conducted in this phase are described in the following sections. We selected those activities because they are easy to implement and, we have found, receive overall patient acceptability.

For a detailed understanding of strategies used in Phase II of CBT for preventing suicide, see Related Resources. In addition, the book Choosing to live: How to defeat suicide through cognitive therapy11 can serve as a self-help guide for patients to follow through with CBT skill-building strategies.

Sample activity #1: Construct a ‘hope box.’ One activity that you can use to help a patient cope with suicide-activating core beliefs (eg, “My life is worthless”) involves construction of a so-called hope box. The box helps the patient directly challenge his extreme distress, by being reminded of previous successes, positive experiences, and reasons for living. The process of constructing a hope box allows the patient to work on modifying his problematic core beliefs (eg, worthlessness, helplessness, incapable of being loved).

It can be helpful to have the patient construct his hope box during a session, to ensure that everything that is put in the box is truly helpful and personalized. Items included vary from patient to patient, and might consist of pictures of loved ones, a favorite poem, a prayer, coping cards (see next section), or all of these. For example, one of our patients chose to include a picture of herself in her early 20s as a reminder of a positive, fulfilling time in her life; this gave her hope that it is possible to experience those feelings again.

Bush et alb at the National Center for Telehealth and Technology have developed a Virtual Hope Box, a free mobile application for tablets and smartphones (compatible with Android and iOS operating systems) that patients can use under the guidance of their practitioner.

bwww.t2.health.mil/apps/virtual-hope-box

Sample activity #2: Generate coping cards. Effective problem-solving skills can be promoted by having the patient construct coping cards —wallet-size cards generated collaboratively in session. Coping cards are note cards that a patient keeps nearby to cope better during a difficult situation. They provide an easily accessible way to jump-start adaptive thinking during a suicidal crisis. The patient is encouraged to use coping cards to practice adaptive thinking even when not in a crisis.

There are 3 kinds of coping cards:

• place a suicide-relevant automatic thought or core belief on one side of the card; on the other side, place an alternative, more adaptive response

• write a list of coping strategies

• write instructions to motivate or “activate” the patient toward completing a specific goal (Figure 2).

Phase III: Prevent relapse

Complete relapse prevention task. Relapse prevention is a common CBT strategy that aims to strengthen self-management to minimize likelihood of returning to a previously stopped behavior. For patients who present only with suicidal thoughts, relapse prevention is directed at identifying triggers and minimizing the occurrence and/ or intensity of such thoughts in the future. For patients who present with suicidal self-directed violence, relapse prevention is directed at identifying triggers for suicidal actions and reducing the likelihood of acting on suicidal urges. The brief guidance provided below will familiarize you with each of the relapse prevention steps, which may be completed in multiple sessions.

Step 1: Provide psychoeducation

Explain the difference between a lapse and a relapse. In general, you want the patient to understand that, although suicidal thoughts might persist and recur over time, suicidal self-directed violence must be prevented. Describe the purpose of the relapse prevention task (ie, to minimize the chance that suicidal thinking and actions will recur); address questions and concerns; and obtain permission to begin the procedure. Assure the patient that this is a collaborative activity and you will be in the room to ensure comfort and safety.

STEP 2: Retell the suicide story

Ask the patient to imagine the chain of events, thoughts, and feelings that led to the most recent episode of suicide ideation or suicidal self-directed violence. Tell the patient that you want him to construct a movie script to describe the chain of events that resulted in the suicide crisis —but to do so slowly, taking enough time to describe the details of each scene of the movie.

Step 3: Apply CBT skills

Ask the patient again to take you through the sequence of events leading to the most recent episode of suicide ideation or suicidal self-directed violence. This time, however, direct him to use the skills learned in therapy to appropriately respond cognitively, affectively, and behaviorally to move further away from the suicide outcome.

If the patient is moving too fast or neglecting important points, stop and ask about alternative ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving. Use as much time as needed until the patient is able to demonstrate solid learning of at least several learned CBT strategies to prevent suicidal self-directed violence.

Step 4: Generalize learning to prepare for future suicidal crises

In this stage —given your knowledge of the patient’s psychosocial history, cognitive- behavioral conceptualization, and suicide mode triggers —you collaboratively create a future scenario that is likely to activate suicidal self-directed violence. Question the patient about possible coping strategies, provide helpful feedback, guide him through each link in the chain of events, and propose additional alternative strategies if he is clearly neglecting important points of the intervention.

Step 5: Debrief and summarize lessons learned

Debrief the patient by providing a summary of the skills he has learned in therapy, congratulate him for completing this final therapeutic task, and assess overall emotional reaction to this activity. Remind him that mood fluctuations and future setbacks, in the form of lapses, are expected. Give him the option to request booster sessions and make plans for next steps in accomplishing general goals of therapy.

Treatment can be terminated when the patient is able to complete the relapse prevention task. If he is not ready or able to complete this exercise successfully, you can extend treatment. The duration of the extension is left to the practitioner’s judgment, based on the overall treatment plan. Brown and colleagues2 have reported a maximum number of 24 outpatient sessions (for patients who need additional booster sessions); based on clinical experience, it is reasonable to assume that it would be highly unlikely for a patient not to meet treatment objectives after a methodical course of outpatient CBT.

In cases in which goals of treatment have not been met, consultation with colleagues, review of adherence problems, and consideration of obstacles for treatment efficacy would be recommended.

A checklist can be used to determine whether a patient is ready to end treatment. Variables that can be considered in assessing readiness for termination include:

• reduced scores on self-report measures for a number of weeks

• evidence of enhanced problem-solving

• engagement in adjunctive health care services

• development of a social support system.

Post-Admission Cognitive Therapy (PACT)

An inpatient cognitive-behavioral protocol for the prevention of suicide, adapted from the efficacious outpatient model, is being evaluated at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland, and Fort Belvoir Community Hospital, Fort Belvoir, Virginia. The inpatient intervention is called PACT; components are summarized in Table 4.

Bottom Line

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for preventing suicide is an efficacious protocol for reducing the recurrence of suicidal self-directed violence. Post-Admission Cognitive Therapy is the adapted inpatient treatment package. You are encouraged to gain additional training and supervision on the delivery of these interventions to your high-risk suicidal patients.

Related Resources

• Academy of Cognitive Therapy. www.academyofct.org.

• National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. www.suicide preventionlifeline.org.

• Wenzel A, Brown GK, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for suicidal patients: scientific and clinical applications. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009.

Disclosures

Support for research on inpatient cognitive-behavioral therapy for the prevention of suicide provided to Principal Investigator, Dr. Ghahramanlou-Holloway by the Department of Defense, Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (W81XWH-08-2-0172), Military Operational Medicine Research Program (W81XWH-11-2-0106), and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (15219).

Many mental health practitioners have had training in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)—short-term, evidence-based psychotherapy for treating a variety of psychiatric conditions (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder) and medical comorbidities (eg, insomnia)—but only some are knowledgeable about how to best use CBT with a suicidal patient. This article provides a clinician-friendly summary of a 10-session evidence-based outpatient1-3 and an adapted 6 to 8 session inpatient4,5 cognitive-behavioral protocol (known as Post-Admission Cognitive Therapy [PACT]) that is designed to help patients who have suicide-related thoughts and/or behaviors.

3 phases of CBT for suicide prevention

An average of 9 hours of individual CBT for the prevention of suicide has been reported to reduce the likelihood of repeat suicide attempts in approximately 50% of patients.1 Here, we introduce you to 3 phases of CBT for preventing suicide—phases that are the same for outpatients or inpatients. Our aim is to help you become familiar with CBT strategies that can be adapted for your treatment setting and used to intervene with vulnerable patients who are at risk for suicidal self-directed violence. A thorough assessment of the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis and history, presenting problems, and risk and protective factors for suicide must be completed before treatment begins.

Phase I. The patient is asked to tell a story associated with his (her) most recent episode of suicidal thoughts or behavior, or both. This narrative serves as 1) a foundation for planning treatment and 2) a model for understanding how best to deactivate the wish to die through the process of psychotherapy.

Phase II. The patient is assisted with modifying underdeveloped or overdeveloped skills that are most closely associated with the risk of triggering a suicidal crisis. For example, a patient with underdeveloped skills in regulating anger and hatred toward himself is taught to modulate these problematic emotions more effectively. In addition, effective problem-solving strategies are reviewed and practiced.

Phase III. The patient is guided through a relapse prevention task. The purpose of this exercise is to 1) highlight skills learned during therapy and 2) allow the patient to practice effective problem-solving strategies that are aimed at minimizing the recurrence of suicidal self-directed violence.

Theorectical basis for preventing suicide with CBT

Aaron Beck, in 1979,6 proposed that a person’s biopsychosocial vulnerabilities can interact with suicidal thoughts and behaviors to produce a state that Beck labeled the “suicide mode.” Once produced, a suicide mode can become activated by cognitive, affective, motivational, and behavioral systems.

The frequency and severity of suicide mode activation can increase over time, especially for persons who do not have protective factors and those who have a history of self-directed violence—in particular, attempted suicide. Moreover, some persons might experience a chronic state of suicide mode activation and, therefore, remain at elevated risk of suicide. Once a suicide-specific mode is activated, the person considers suicide the only option for solving his life problems. Suicide might be considered a rational decision at this point.6

The hypothesized mechanism of action associated with CBT for preventing suicide can be described as:

• deactivation of the suicide mode

• modification of the structure and content of the suicide mode

• construction and practice of more adaptive structural modes to promote a desire to live.

The underlying philosophy of this intervention is that the suicide mode occurs independently of psychiatric diagnoses and must be targeted directly; treatment therefore is transdiagnostic.7 In other words, instead of addressing a symptom of a psychiatric disorder, treatment directly targets suicide-related ideation and behaviors (Table 1).

Using that framework, psychiatric diagnoses are conceptualized in terms of how the associated symptoms contribute to the activation, maintenance, and exacerbation of the suicide mode.

Protocol for preventing suicide

The outpatient protocol1-3 comprises 10, 45- to 50-minute weekly individual psychotherapy sessions, with an allowance for booster sessions (as needed), until the patient is able to complete the relapse prevention task in Phase III. The inpatient protocol4,5 comprises 6, 90-minute individual psychotherapy sessions, with an allowance for 2 booster sessions (as needed) during the inpatient stay and as many as 4 telephone booster sessions after discharge.

Phase I: Tell the suicide story

Engage the patient in treatment. To increase adherence to treatment and minimize the risk of drop-out, practitioners are encouraged to establish a strong, early therapeutic alliance with the patient. Showing genuine empathy and providing a safe, supportive, and nonjudgmental environment are instrumental for engaging patients in treatment. The practitioner listens carefully to the patient’s narrative, provides periodic summaries to check on accurate understanding, and keeps interruptions to a minimum.

Collaboratively generate a safety plan. A crisis response plan or safety plan—an individualized, hierarchically arranged, written list of coping strategies to be implemented during a suicide crisis—is developed as soon as possible. Guidance on how to develop a structured safety plan has been provided by Stanley and Brown.8,9

Practitioners must ensure that the safety plan contains contact information that the patient can use to reach the practitioner, the clinic, the on-call provider (if available), the local 24-hour emergency department, and the 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (800-273-TALK [8255]). Discussion of how to limit access to lethal means also is important.

Because safety planning is a collaborative process, it is imperative that practitioners check on the patient’s willingness to follow the safety plan and help him overcome perceived obstacles in implementation. Copies of the plan can be kept at different locations and shared with family members, friends, or both with the patient’s permission.

Develop a cognitive-behavioral conceptualization. The cognitive-behavioral conceptualization is an individualized map of a patient’s automatic thoughts (eg, “I am going to get fired today”), conditional assumptions (“If I get fired, then my life is over”), and core beliefs (“I am an utter failure”) that are activated before, during, and after suicidal self-directed violence. To develop that conceptualization, the patient is asked to tell a story about his (her) most recent suicidal crisis (the Box, offers a sample script) and to describe reactions to having survived a suicide attempt. (Note: Patients who report regret after an attempt are at greatest risk for dying by suicide.10)

This activity gives the patient an opportunity to disclose details surrounding his suicidal thoughts and actions, and might allow for a cathartic experience through storytelling. As practitioners listen to the suicide narrative, they collect data on the patient’s early childhood experiences (typically, suicide-activating events), associated automatic thoughts and images, emotional responses, and subsequent behaviors.

Based on this information, a cognitive-behavioral case conceptualization diagram (Figure 1, and Table 2) is generated collaboratively with the patienta and used to personalize treatment planning.

a Judith Beck offers sample case conceptualization diagrams in Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond, 2nd ed. New York, New York: Guilford Press; 2011.

Phase II: Build skills

Build skills to prevent episodes of suicidal self-directed violence. Information obtained from the conceptualization is used to generate an individualized cognitive-behavioral plan of intervention. The overall goal is to determine skill-based problem areas that are associated with the most recent episode of suicidal self-directed violence.

Practitioner and patient collaboratively identify skills that are underdeveloped and ones that are overdeveloped so that they can be addressed systematically. In general, based on our clinical experience with suicidal patients, we recommend focusing on skills captured within ≥1 of the deficit domains in Table 3. Explanation of the various cognitive-behavioral strategies used in this phase of treatment is beyond the scope of this article, but 2 activities that highlight the clinical work conducted in this phase are described in the following sections. We selected those activities because they are easy to implement and, we have found, receive overall patient acceptability.

For a detailed understanding of strategies used in Phase II of CBT for preventing suicide, see Related Resources. In addition, the book Choosing to live: How to defeat suicide through cognitive therapy11 can serve as a self-help guide for patients to follow through with CBT skill-building strategies.

Sample activity #1: Construct a ‘hope box.’ One activity that you can use to help a patient cope with suicide-activating core beliefs (eg, “My life is worthless”) involves construction of a so-called hope box. The box helps the patient directly challenge his extreme distress, by being reminded of previous successes, positive experiences, and reasons for living. The process of constructing a hope box allows the patient to work on modifying his problematic core beliefs (eg, worthlessness, helplessness, incapable of being loved).

It can be helpful to have the patient construct his hope box during a session, to ensure that everything that is put in the box is truly helpful and personalized. Items included vary from patient to patient, and might consist of pictures of loved ones, a favorite poem, a prayer, coping cards (see next section), or all of these. For example, one of our patients chose to include a picture of herself in her early 20s as a reminder of a positive, fulfilling time in her life; this gave her hope that it is possible to experience those feelings again.

Bush et alb at the National Center for Telehealth and Technology have developed a Virtual Hope Box, a free mobile application for tablets and smartphones (compatible with Android and iOS operating systems) that patients can use under the guidance of their practitioner.

bwww.t2.health.mil/apps/virtual-hope-box

Sample activity #2: Generate coping cards. Effective problem-solving skills can be promoted by having the patient construct coping cards —wallet-size cards generated collaboratively in session. Coping cards are note cards that a patient keeps nearby to cope better during a difficult situation. They provide an easily accessible way to jump-start adaptive thinking during a suicidal crisis. The patient is encouraged to use coping cards to practice adaptive thinking even when not in a crisis.

There are 3 kinds of coping cards:

• place a suicide-relevant automatic thought or core belief on one side of the card; on the other side, place an alternative, more adaptive response

• write a list of coping strategies

• write instructions to motivate or “activate” the patient toward completing a specific goal (Figure 2).

Phase III: Prevent relapse

Complete relapse prevention task. Relapse prevention is a common CBT strategy that aims to strengthen self-management to minimize likelihood of returning to a previously stopped behavior. For patients who present only with suicidal thoughts, relapse prevention is directed at identifying triggers and minimizing the occurrence and/ or intensity of such thoughts in the future. For patients who present with suicidal self-directed violence, relapse prevention is directed at identifying triggers for suicidal actions and reducing the likelihood of acting on suicidal urges. The brief guidance provided below will familiarize you with each of the relapse prevention steps, which may be completed in multiple sessions.

Step 1: Provide psychoeducation

Explain the difference between a lapse and a relapse. In general, you want the patient to understand that, although suicidal thoughts might persist and recur over time, suicidal self-directed violence must be prevented. Describe the purpose of the relapse prevention task (ie, to minimize the chance that suicidal thinking and actions will recur); address questions and concerns; and obtain permission to begin the procedure. Assure the patient that this is a collaborative activity and you will be in the room to ensure comfort and safety.

STEP 2: Retell the suicide story

Ask the patient to imagine the chain of events, thoughts, and feelings that led to the most recent episode of suicide ideation or suicidal self-directed violence. Tell the patient that you want him to construct a movie script to describe the chain of events that resulted in the suicide crisis —but to do so slowly, taking enough time to describe the details of each scene of the movie.

Step 3: Apply CBT skills

Ask the patient again to take you through the sequence of events leading to the most recent episode of suicide ideation or suicidal self-directed violence. This time, however, direct him to use the skills learned in therapy to appropriately respond cognitively, affectively, and behaviorally to move further away from the suicide outcome.

If the patient is moving too fast or neglecting important points, stop and ask about alternative ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving. Use as much time as needed until the patient is able to demonstrate solid learning of at least several learned CBT strategies to prevent suicidal self-directed violence.

Step 4: Generalize learning to prepare for future suicidal crises

In this stage —given your knowledge of the patient’s psychosocial history, cognitive- behavioral conceptualization, and suicide mode triggers —you collaboratively create a future scenario that is likely to activate suicidal self-directed violence. Question the patient about possible coping strategies, provide helpful feedback, guide him through each link in the chain of events, and propose additional alternative strategies if he is clearly neglecting important points of the intervention.

Step 5: Debrief and summarize lessons learned

Debrief the patient by providing a summary of the skills he has learned in therapy, congratulate him for completing this final therapeutic task, and assess overall emotional reaction to this activity. Remind him that mood fluctuations and future setbacks, in the form of lapses, are expected. Give him the option to request booster sessions and make plans for next steps in accomplishing general goals of therapy.

Treatment can be terminated when the patient is able to complete the relapse prevention task. If he is not ready or able to complete this exercise successfully, you can extend treatment. The duration of the extension is left to the practitioner’s judgment, based on the overall treatment plan. Brown and colleagues2 have reported a maximum number of 24 outpatient sessions (for patients who need additional booster sessions); based on clinical experience, it is reasonable to assume that it would be highly unlikely for a patient not to meet treatment objectives after a methodical course of outpatient CBT.

In cases in which goals of treatment have not been met, consultation with colleagues, review of adherence problems, and consideration of obstacles for treatment efficacy would be recommended.

A checklist can be used to determine whether a patient is ready to end treatment. Variables that can be considered in assessing readiness for termination include:

• reduced scores on self-report measures for a number of weeks

• evidence of enhanced problem-solving

• engagement in adjunctive health care services

• development of a social support system.

Post-Admission Cognitive Therapy (PACT)

An inpatient cognitive-behavioral protocol for the prevention of suicide, adapted from the efficacious outpatient model, is being evaluated at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland, and Fort Belvoir Community Hospital, Fort Belvoir, Virginia. The inpatient intervention is called PACT; components are summarized in Table 4.

Bottom Line

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for preventing suicide is an efficacious protocol for reducing the recurrence of suicidal self-directed violence. Post-Admission Cognitive Therapy is the adapted inpatient treatment package. You are encouraged to gain additional training and supervision on the delivery of these interventions to your high-risk suicidal patients.

Related Resources

• Academy of Cognitive Therapy. www.academyofct.org.

• National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. www.suicide preventionlifeline.org.

• Wenzel A, Brown GK, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for suicidal patients: scientific and clinical applications. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009.

Disclosures

Support for research on inpatient cognitive-behavioral therapy for the prevention of suicide provided to Principal Investigator, Dr. Ghahramanlou-Holloway by the Department of Defense, Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (W81XWH-08-2-0172), Military Operational Medicine Research Program (W81XWH-11-2-0106), and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (15219).

1. Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(5):563-570.

2. Brown GK, Henriques GR, Ratto C, et al. Cognitive therapy treatment manual for suicide attempters. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania; 2002 (unpublished).

3. Berk MS, Henriques GR, Warman DM, et al. A cognitive therapy intervention for suicide attempters: an overview of the treatment and case examples. Cogn Behav Pract. 2004;11(3):265-277.

4. Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, Cox D, Greene F. Post-admission cognitive therapy: a brief intervention for psychiatric inpatients admitted after a suicide attempt. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):233-244.

5. Neely L, Irwin K, Carreno Ponce JT, et al. Post Admission Cognitive Therapy (PACT) for the prevention of suicide in military personnel with histories of trauma: treatment development and case example. Clinical Case Studies. 2013;12(6):457-473.

6. Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York, NY: Penguin Group; 1979.

7. Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, Brown GK, Beck AT. Suicide. In: Whisman M, ed. Adapting cognitive therapy for depression: managing complexity and comorbidity. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008:159-184.

8. Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety planning intervention: a brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):256-264.

9. Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety plan treatment manual to reduce suicide risk: veteran version. http://www. mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/va_safety_planning_manual. pdf. Published August 20, 2008. Accessed July 2, 2014.

10. Henriques G, Wenzel A, Brown GK, et al. Suicide attempters’ reaction to survival as a risk factor for eventual suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(11):2180-2182.

11. Ellis TE, Newman CF. Choosing to live: How to defeat suicide through cognitive therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc; 1996.

1. Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(5):563-570.

2. Brown GK, Henriques GR, Ratto C, et al. Cognitive therapy treatment manual for suicide attempters. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania; 2002 (unpublished).

3. Berk MS, Henriques GR, Warman DM, et al. A cognitive therapy intervention for suicide attempters: an overview of the treatment and case examples. Cogn Behav Pract. 2004;11(3):265-277.

4. Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, Cox D, Greene F. Post-admission cognitive therapy: a brief intervention for psychiatric inpatients admitted after a suicide attempt. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):233-244.

5. Neely L, Irwin K, Carreno Ponce JT, et al. Post Admission Cognitive Therapy (PACT) for the prevention of suicide in military personnel with histories of trauma: treatment development and case example. Clinical Case Studies. 2013;12(6):457-473.

6. Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York, NY: Penguin Group; 1979.

7. Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, Brown GK, Beck AT. Suicide. In: Whisman M, ed. Adapting cognitive therapy for depression: managing complexity and comorbidity. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008:159-184.

8. Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety planning intervention: a brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):256-264.

9. Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety plan treatment manual to reduce suicide risk: veteran version. http://www. mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/va_safety_planning_manual. pdf. Published August 20, 2008. Accessed July 2, 2014.

10. Henriques G, Wenzel A, Brown GK, et al. Suicide attempters’ reaction to survival as a risk factor for eventual suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(11):2180-2182.

11. Ellis TE, Newman CF. Choosing to live: How to defeat suicide through cognitive therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc; 1996.