User login

The Hospitalist only

Is a telehospitalist service right for you and your group?

Telemedicine “ripe for adoption” by hospitalists

For medical inpatients, the advent of virtual care began decades ago with telephones and the ability of physicians to give “verbal orders” while outside the hospital. It evolved into widespread adoption of pagers and is now ubiquitous through smart phones, texting, and HIPPA-compliant applications. In the past few years, inpatient telemedicine programs have been developed and studied including tele-ICU, telestroke, and now the telehospitalist.

Telemedicine is not new and has seen rapid adoption in the outpatient setting over the past decade,1 especially since the passing of telemedicine parity laws in 35 states to support equal reimbursement with face-to-face visits.2 In addition, 24 states have joined the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC).3 This voluntary program provides an expedited pathway to licensure for qualified physicians who practice in multiple states. The goal is to increase access to care for patients in underserved and rural areas and to allow easier consultation through telemedicine. Combined, these two federal initiatives have lowered two major barriers to entry for telemedicine: reimbursement and credentialing.

Only a handful of papers have been published on the telehospitalist model with one of the first in 2007 in The Hospitalist reporting on the intersection between tele-ICU and telehospitalist care.4 More recent work describes the implementation of a telehospitalist program between a large university hospitalist program and a rural, critical access hospital.5 A key goal of this program, developed by Dr. Ethan Kuperman and colleagues at the University of Iowa, was to keep patients at the critical access hospital that previously would have been transferred. This has obvious benefits for patients, the critical access hospital, and the local community. It also benefited the tertiary care referral center, which was dealing with high occupancy rates. Keeping lower acuity patients at the critical access hospital helps maintain access for more complex patients at the referral center. This same principle has applied to the use of the tele-ICU where lower acuity ICU patients could remain in the small, rural ICU, and only those patients who the intensivist believes would benefit from a higher level of care in a tertiary center would be transferred.

As this study and others have shown, telemedicine is ripe for adoption by hospitalists. The bigger question is how should it fit into the current model of hospital medicine? There are several different applications we are familiar with and each has unique considerations. The first model, as applied in the Kuperman paper, is for a larger hospitalist program to provide a telehospitalist service to a smaller, unaffiliated hospital (for example, critical access hospitals) that employs nurse practitioners or physician assistants on site but can’t recruit or retain full-time hospitalist coverage. In this collaborative model of care, the local provider performs the physical exam but provides care under the guidance and supervision of a hospital medicine specialist. This is expected to improve outcomes and bring the benefits of hospital medicine, including improved outcomes and decreased hospital spending, to smaller communities.6 In this model, the critical access hospital pays a fee for the service and retains the billing to third party payers.

A variation on that model would provide telehospitalist services to other hospitals within an existing health care network (such as Kaiser Permanente, Intermountain Healthcare, government hospitals) that have different financial models with incentives to collaborate. The Veterans Health Administration is embarking on a pilot through the VA Office of Rural Health to provide a telehospitalist service to small rural VA hospitals using the consultative model during the day with a nurse practitioner at the local site and physician backup from the emergency department. Although existing night cross-coverage will be maintained by a physician on call, this telehospitalist service may also evolve into providing cross-coverage on nights and weekends.

A third would be like a locum tenens model in which telehospitalist services are contracted for short periods of time when coverage is needed for vacations or staff shortages. A fourth model of telehospitalist care would be to international areas in need of hospitalist expertise, like a medical mission model but without the expense or time required to travel. Other models will likely evolve based on the demand for services, supply of hospitalists, changes in regulations, and reimbursement.

Another important consideration is how this will evolve for the practicing hospitalist. Will we have dedicated virtual hospitalists, akin to the “nocturnist” who covers nights and weekends? Or will working on the telehospitalist service be in the rotation of duties like many programs have with teaching and “nonteaching” services, medical consultation, and even transition clinics and emergency department triage responsibilities? It could serve as a lower-intensity service that can be staffed during office-based time that would include scholarly work, quality improvement, and administrative duties. If financially viable, it could be mutually beneficial for both the provider and recipient sides of telehospitalist care.

For any of these models to work, technical aspects must be ironed-out. It is indispensable for the provider to have remote access to the electronic health record for data review, documentation, and placing orders if needed. Adequate broadband for effective video connection, accompanied by the appropriate HIPPA-compliant software and hardware must be in place. Although highly specialized hardware has been developed, including remote stethoscopes and otoscopes, the key component is a good camera and video screen on each end of the interaction. Based upon prior experience with telemedicine programs, establishment of trusting relationships with the receiving hospital staff, physicians, and nurse practitioners is also critical. Optimally, the telehospitalist would have an opportunity to travel to the remote site to meet with the local care team and learn about the local resources and community. Many other operational and logistical issues need to be considered and will be supported by the Society of Hospital Medicine through publications, online resources, and national and regional meeting educational content on telehospitalist programs.

As hospital medicine adopts the telehospitalist model, it brings with it important considerations. First, is how we embrace the concept of the medical virtualist, a term used to describe physicians who spend the majority or all of their time caring for patients using a virtual medium.7 We find it difficult to imagine spending all or the majority of our time as a virtual hospitalist, but years ago many could not imagine someone being a full-time hospitalist or nocturnist. Some individuals will see this as a career opportunity that allows them to work as a hospitalist regardless of where they live or where the hospital is located. That has obvious advantages for both career choice and the provision of hospital medicine expertise to low-resourced or low-volume settings, such as rural or international locations and nights and weekends.

Second, the telehospitalist model will require professional standards, training, reimbursement and coding adjustments, hardware and software development, and managing patient expectations for care.

Lastly, hospitals, health care systems, hospitalist groups, and even individual hospitalists will have to determine how best to take advantage of this innovative model of care to provide the highest possible quality, in a cost-efficient manner, that supports professional satisfaction and development.

Dr. Kaboli and Dr. Gutierrez are based at the Center for Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE) at the Iowa City VA Healthcare System, the Veterans Rural Health Resource Center-Iowa City, VA Office of Rural Health, and the department of internal medicine, University of Iowa, both in Iowa City.

References

1. Barnett ML et al. Trends in telemedicine use in a large commercially insured population, 2005-2017. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2147-9.

2. American Telemedicine Association State Policy Resource Center. 2018; http://www.americantelemed.org/main/policy-page/state-policy-resource-center. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

3. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact 2018; https://imlcc.org/. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

4. Hengehold D. The telehospitalist. The Hospitalist. 2007;7(July). https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/123381/telehospitalist. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

5. Kuperman EF et al. The virtual hospitalist: A single-site implementation bringing hospitalist coverage to critical access hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):759-63.

6. Peterson MC. A systematic review of outcomes and quality measures in adult patients cared for by hospitalists vs nonhospitalists. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2009;84(3):248-54.

7. Nochomovitz M, Sharma R. Is it time for a new medical specialty?: The medical virtualist. JAMA. 2018;319(5):437-8.

Telemedicine “ripe for adoption” by hospitalists

Telemedicine “ripe for adoption” by hospitalists

For medical inpatients, the advent of virtual care began decades ago with telephones and the ability of physicians to give “verbal orders” while outside the hospital. It evolved into widespread adoption of pagers and is now ubiquitous through smart phones, texting, and HIPPA-compliant applications. In the past few years, inpatient telemedicine programs have been developed and studied including tele-ICU, telestroke, and now the telehospitalist.

Telemedicine is not new and has seen rapid adoption in the outpatient setting over the past decade,1 especially since the passing of telemedicine parity laws in 35 states to support equal reimbursement with face-to-face visits.2 In addition, 24 states have joined the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC).3 This voluntary program provides an expedited pathway to licensure for qualified physicians who practice in multiple states. The goal is to increase access to care for patients in underserved and rural areas and to allow easier consultation through telemedicine. Combined, these two federal initiatives have lowered two major barriers to entry for telemedicine: reimbursement and credentialing.

Only a handful of papers have been published on the telehospitalist model with one of the first in 2007 in The Hospitalist reporting on the intersection between tele-ICU and telehospitalist care.4 More recent work describes the implementation of a telehospitalist program between a large university hospitalist program and a rural, critical access hospital.5 A key goal of this program, developed by Dr. Ethan Kuperman and colleagues at the University of Iowa, was to keep patients at the critical access hospital that previously would have been transferred. This has obvious benefits for patients, the critical access hospital, and the local community. It also benefited the tertiary care referral center, which was dealing with high occupancy rates. Keeping lower acuity patients at the critical access hospital helps maintain access for more complex patients at the referral center. This same principle has applied to the use of the tele-ICU where lower acuity ICU patients could remain in the small, rural ICU, and only those patients who the intensivist believes would benefit from a higher level of care in a tertiary center would be transferred.

As this study and others have shown, telemedicine is ripe for adoption by hospitalists. The bigger question is how should it fit into the current model of hospital medicine? There are several different applications we are familiar with and each has unique considerations. The first model, as applied in the Kuperman paper, is for a larger hospitalist program to provide a telehospitalist service to a smaller, unaffiliated hospital (for example, critical access hospitals) that employs nurse practitioners or physician assistants on site but can’t recruit or retain full-time hospitalist coverage. In this collaborative model of care, the local provider performs the physical exam but provides care under the guidance and supervision of a hospital medicine specialist. This is expected to improve outcomes and bring the benefits of hospital medicine, including improved outcomes and decreased hospital spending, to smaller communities.6 In this model, the critical access hospital pays a fee for the service and retains the billing to third party payers.

A variation on that model would provide telehospitalist services to other hospitals within an existing health care network (such as Kaiser Permanente, Intermountain Healthcare, government hospitals) that have different financial models with incentives to collaborate. The Veterans Health Administration is embarking on a pilot through the VA Office of Rural Health to provide a telehospitalist service to small rural VA hospitals using the consultative model during the day with a nurse practitioner at the local site and physician backup from the emergency department. Although existing night cross-coverage will be maintained by a physician on call, this telehospitalist service may also evolve into providing cross-coverage on nights and weekends.

A third would be like a locum tenens model in which telehospitalist services are contracted for short periods of time when coverage is needed for vacations or staff shortages. A fourth model of telehospitalist care would be to international areas in need of hospitalist expertise, like a medical mission model but without the expense or time required to travel. Other models will likely evolve based on the demand for services, supply of hospitalists, changes in regulations, and reimbursement.

Another important consideration is how this will evolve for the practicing hospitalist. Will we have dedicated virtual hospitalists, akin to the “nocturnist” who covers nights and weekends? Or will working on the telehospitalist service be in the rotation of duties like many programs have with teaching and “nonteaching” services, medical consultation, and even transition clinics and emergency department triage responsibilities? It could serve as a lower-intensity service that can be staffed during office-based time that would include scholarly work, quality improvement, and administrative duties. If financially viable, it could be mutually beneficial for both the provider and recipient sides of telehospitalist care.

For any of these models to work, technical aspects must be ironed-out. It is indispensable for the provider to have remote access to the electronic health record for data review, documentation, and placing orders if needed. Adequate broadband for effective video connection, accompanied by the appropriate HIPPA-compliant software and hardware must be in place. Although highly specialized hardware has been developed, including remote stethoscopes and otoscopes, the key component is a good camera and video screen on each end of the interaction. Based upon prior experience with telemedicine programs, establishment of trusting relationships with the receiving hospital staff, physicians, and nurse practitioners is also critical. Optimally, the telehospitalist would have an opportunity to travel to the remote site to meet with the local care team and learn about the local resources and community. Many other operational and logistical issues need to be considered and will be supported by the Society of Hospital Medicine through publications, online resources, and national and regional meeting educational content on telehospitalist programs.

As hospital medicine adopts the telehospitalist model, it brings with it important considerations. First, is how we embrace the concept of the medical virtualist, a term used to describe physicians who spend the majority or all of their time caring for patients using a virtual medium.7 We find it difficult to imagine spending all or the majority of our time as a virtual hospitalist, but years ago many could not imagine someone being a full-time hospitalist or nocturnist. Some individuals will see this as a career opportunity that allows them to work as a hospitalist regardless of where they live or where the hospital is located. That has obvious advantages for both career choice and the provision of hospital medicine expertise to low-resourced or low-volume settings, such as rural or international locations and nights and weekends.

Second, the telehospitalist model will require professional standards, training, reimbursement and coding adjustments, hardware and software development, and managing patient expectations for care.

Lastly, hospitals, health care systems, hospitalist groups, and even individual hospitalists will have to determine how best to take advantage of this innovative model of care to provide the highest possible quality, in a cost-efficient manner, that supports professional satisfaction and development.

Dr. Kaboli and Dr. Gutierrez are based at the Center for Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE) at the Iowa City VA Healthcare System, the Veterans Rural Health Resource Center-Iowa City, VA Office of Rural Health, and the department of internal medicine, University of Iowa, both in Iowa City.

References

1. Barnett ML et al. Trends in telemedicine use in a large commercially insured population, 2005-2017. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2147-9.

2. American Telemedicine Association State Policy Resource Center. 2018; http://www.americantelemed.org/main/policy-page/state-policy-resource-center. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

3. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact 2018; https://imlcc.org/. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

4. Hengehold D. The telehospitalist. The Hospitalist. 2007;7(July). https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/123381/telehospitalist. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

5. Kuperman EF et al. The virtual hospitalist: A single-site implementation bringing hospitalist coverage to critical access hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):759-63.

6. Peterson MC. A systematic review of outcomes and quality measures in adult patients cared for by hospitalists vs nonhospitalists. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2009;84(3):248-54.

7. Nochomovitz M, Sharma R. Is it time for a new medical specialty?: The medical virtualist. JAMA. 2018;319(5):437-8.

For medical inpatients, the advent of virtual care began decades ago with telephones and the ability of physicians to give “verbal orders” while outside the hospital. It evolved into widespread adoption of pagers and is now ubiquitous through smart phones, texting, and HIPPA-compliant applications. In the past few years, inpatient telemedicine programs have been developed and studied including tele-ICU, telestroke, and now the telehospitalist.

Telemedicine is not new and has seen rapid adoption in the outpatient setting over the past decade,1 especially since the passing of telemedicine parity laws in 35 states to support equal reimbursement with face-to-face visits.2 In addition, 24 states have joined the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC).3 This voluntary program provides an expedited pathway to licensure for qualified physicians who practice in multiple states. The goal is to increase access to care for patients in underserved and rural areas and to allow easier consultation through telemedicine. Combined, these two federal initiatives have lowered two major barriers to entry for telemedicine: reimbursement and credentialing.

Only a handful of papers have been published on the telehospitalist model with one of the first in 2007 in The Hospitalist reporting on the intersection between tele-ICU and telehospitalist care.4 More recent work describes the implementation of a telehospitalist program between a large university hospitalist program and a rural, critical access hospital.5 A key goal of this program, developed by Dr. Ethan Kuperman and colleagues at the University of Iowa, was to keep patients at the critical access hospital that previously would have been transferred. This has obvious benefits for patients, the critical access hospital, and the local community. It also benefited the tertiary care referral center, which was dealing with high occupancy rates. Keeping lower acuity patients at the critical access hospital helps maintain access for more complex patients at the referral center. This same principle has applied to the use of the tele-ICU where lower acuity ICU patients could remain in the small, rural ICU, and only those patients who the intensivist believes would benefit from a higher level of care in a tertiary center would be transferred.

As this study and others have shown, telemedicine is ripe for adoption by hospitalists. The bigger question is how should it fit into the current model of hospital medicine? There are several different applications we are familiar with and each has unique considerations. The first model, as applied in the Kuperman paper, is for a larger hospitalist program to provide a telehospitalist service to a smaller, unaffiliated hospital (for example, critical access hospitals) that employs nurse practitioners or physician assistants on site but can’t recruit or retain full-time hospitalist coverage. In this collaborative model of care, the local provider performs the physical exam but provides care under the guidance and supervision of a hospital medicine specialist. This is expected to improve outcomes and bring the benefits of hospital medicine, including improved outcomes and decreased hospital spending, to smaller communities.6 In this model, the critical access hospital pays a fee for the service and retains the billing to third party payers.

A variation on that model would provide telehospitalist services to other hospitals within an existing health care network (such as Kaiser Permanente, Intermountain Healthcare, government hospitals) that have different financial models with incentives to collaborate. The Veterans Health Administration is embarking on a pilot through the VA Office of Rural Health to provide a telehospitalist service to small rural VA hospitals using the consultative model during the day with a nurse practitioner at the local site and physician backup from the emergency department. Although existing night cross-coverage will be maintained by a physician on call, this telehospitalist service may also evolve into providing cross-coverage on nights and weekends.

A third would be like a locum tenens model in which telehospitalist services are contracted for short periods of time when coverage is needed for vacations or staff shortages. A fourth model of telehospitalist care would be to international areas in need of hospitalist expertise, like a medical mission model but without the expense or time required to travel. Other models will likely evolve based on the demand for services, supply of hospitalists, changes in regulations, and reimbursement.

Another important consideration is how this will evolve for the practicing hospitalist. Will we have dedicated virtual hospitalists, akin to the “nocturnist” who covers nights and weekends? Or will working on the telehospitalist service be in the rotation of duties like many programs have with teaching and “nonteaching” services, medical consultation, and even transition clinics and emergency department triage responsibilities? It could serve as a lower-intensity service that can be staffed during office-based time that would include scholarly work, quality improvement, and administrative duties. If financially viable, it could be mutually beneficial for both the provider and recipient sides of telehospitalist care.

For any of these models to work, technical aspects must be ironed-out. It is indispensable for the provider to have remote access to the electronic health record for data review, documentation, and placing orders if needed. Adequate broadband for effective video connection, accompanied by the appropriate HIPPA-compliant software and hardware must be in place. Although highly specialized hardware has been developed, including remote stethoscopes and otoscopes, the key component is a good camera and video screen on each end of the interaction. Based upon prior experience with telemedicine programs, establishment of trusting relationships with the receiving hospital staff, physicians, and nurse practitioners is also critical. Optimally, the telehospitalist would have an opportunity to travel to the remote site to meet with the local care team and learn about the local resources and community. Many other operational and logistical issues need to be considered and will be supported by the Society of Hospital Medicine through publications, online resources, and national and regional meeting educational content on telehospitalist programs.

As hospital medicine adopts the telehospitalist model, it brings with it important considerations. First, is how we embrace the concept of the medical virtualist, a term used to describe physicians who spend the majority or all of their time caring for patients using a virtual medium.7 We find it difficult to imagine spending all or the majority of our time as a virtual hospitalist, but years ago many could not imagine someone being a full-time hospitalist or nocturnist. Some individuals will see this as a career opportunity that allows them to work as a hospitalist regardless of where they live or where the hospital is located. That has obvious advantages for both career choice and the provision of hospital medicine expertise to low-resourced or low-volume settings, such as rural or international locations and nights and weekends.

Second, the telehospitalist model will require professional standards, training, reimbursement and coding adjustments, hardware and software development, and managing patient expectations for care.

Lastly, hospitals, health care systems, hospitalist groups, and even individual hospitalists will have to determine how best to take advantage of this innovative model of care to provide the highest possible quality, in a cost-efficient manner, that supports professional satisfaction and development.

Dr. Kaboli and Dr. Gutierrez are based at the Center for Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE) at the Iowa City VA Healthcare System, the Veterans Rural Health Resource Center-Iowa City, VA Office of Rural Health, and the department of internal medicine, University of Iowa, both in Iowa City.

References

1. Barnett ML et al. Trends in telemedicine use in a large commercially insured population, 2005-2017. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2147-9.

2. American Telemedicine Association State Policy Resource Center. 2018; http://www.americantelemed.org/main/policy-page/state-policy-resource-center. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

3. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact 2018; https://imlcc.org/. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

4. Hengehold D. The telehospitalist. The Hospitalist. 2007;7(July). https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/123381/telehospitalist. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

5. Kuperman EF et al. The virtual hospitalist: A single-site implementation bringing hospitalist coverage to critical access hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):759-63.

6. Peterson MC. A systematic review of outcomes and quality measures in adult patients cared for by hospitalists vs nonhospitalists. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2009;84(3):248-54.

7. Nochomovitz M, Sharma R. Is it time for a new medical specialty?: The medical virtualist. JAMA. 2018;319(5):437-8.

Advance care planning codes not being used

Starting in 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services began paying physicians for advance care planning discussions with the approval of two new codes: 99497 and 99498. The codes pay about $86 for the first 30 minutes of a face-to-face conversation with a patient, family member, and/or surrogate and about $75 for additional sessions. Services can be furnished in both inpatient and ambulatory settings, and payment is not limited to particular physician specialties.

In 2016, health care professionals in New England (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont) billed Medicare 26,522 times for the advance care planning (ACP) codes for a total of 24,536 patients, which represented less than 1% of Medicare beneficiaries in New England at the time, according to Kimberly Pelland, MPH, of Healthcentric Advisors, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues. Most claims were billed in the office, followed by in nursing homes, and in hospitals; 40% of conversations occurred during an annual wellness visit (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8107).

Internists billed Medicare the most for ACP claims (65%), followed by family physicians (22%) gerontologists (5%), and oncologist/hematologists (0.3%), according to the analysis based on 2016 Medicare claims data and Census Bureau data. A greater proportion of patients with ACP claims were female, aged 85 years or older, enrolled in hospice, and died in the study year. Patients had higher odds of having an ACP claim if they were older and had lower income, and if they had cancer, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, or dementia. Male patients who were Asian, black, and Hispanic had lower chances of having an ACP claim.

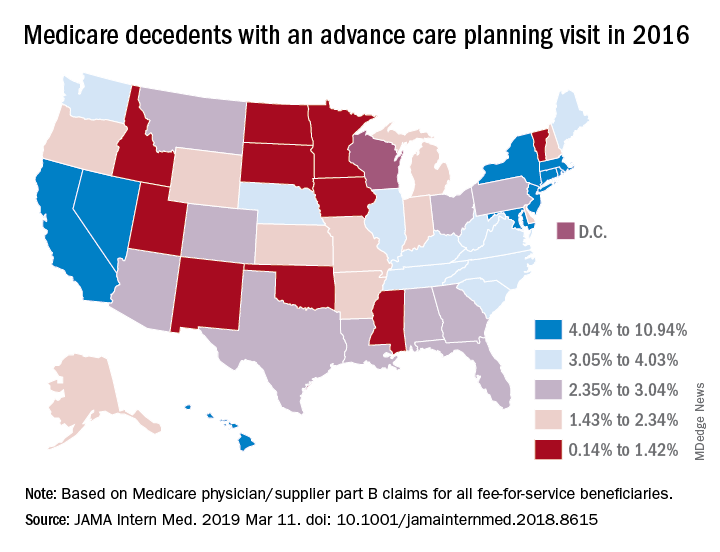

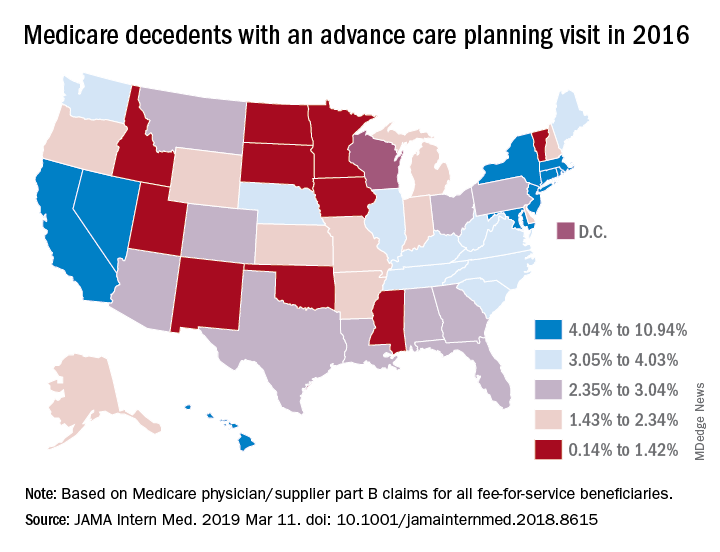

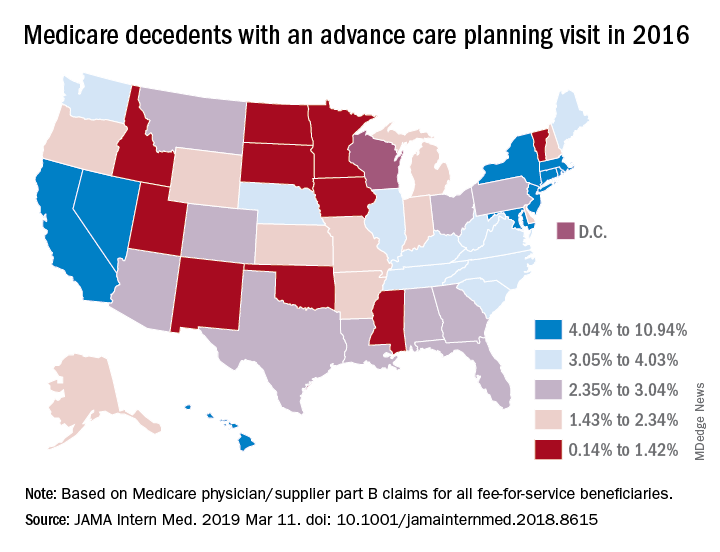

In a related study, Emmanuelle Belanger, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues examined national Medicare data from 2016 to the third quarter of 2017. Across the United States, 2% of Medicare patients aged 65 years and older received advance care planning services that were billed under the ACP codes (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8615). Visits billed under the ACP codes increased from 538,275 to 633,214 during the same time period. Claim rates were higher among patients who died within the study period, reaching 3% in 2016 and 6% in 2017. The percentage of decedents with an ACP billed visit varied strongly across states, with states such as North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming having the fewest ACP visits billed and states such as California and Nevada having the most. ACP billed visits increased in all settings in 2017, but primarily in hospitals and nursing homes. Nationally, internists billed the codes most (48%), followed by family physicians (28%).

While the two studies indicate low usage of the ACP codes, many physicians are discussing advance care planning with their patients, said Mary M. Newman, MD, an internist based in Lutherville, Md., and former American College of Physicians adviser to the American Medical Association Relative Scale Value Update Committee (RUC).

“What cannot be captured by tracking under Medicare claims data are those shorter conversations that we have frequently,” Dr. Newman said in an interview. “If we have a short conversation about advance care planning, it gets folded into our evaluation and management visit. It’s not going to be separately billed.”

At the same time, some patients are not ready to discuss end-of-life options and decline the discussions when asked, Dr. Newman said. Particularly for healthier patients, end of life care is not a primary focus, she noted.

“Not everybody’s ready to have an advance care planning [discussion] that lasts 16-45 minutes,” she said. “Many people over age 65 are not ready to deal with advance care planning in their day-to-day lives, and it may not be what they wish to discuss. I offer the option to patients and some say, ‘Yes, I’d love to,’ and others decline or postpone.”

Low usage of the ACP codes may be associated with lack of awareness, uncertainty about appropriate code use, or associated billing that is not part of the standard workflow, Ankita Mehta, MD, of Mount Sinai in New York wrote an editorial accompanying the studies (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8105).

“Regardless, the low rates of utilization of ACP codes is alarming and highlights the need to create strategies to integrate ACP discussions into standard practice and build ACP documentation and billing in clinical workflow,” Dr. Mehta said.

Dr. Newman agreed that more education among physicians is needed.

“The amount of education clinicians have received varies tremendously across the geography of the country,” she said. “I think the codes are going to be slowly adopted. The challenge to us is to make sure we’re all better educated on palliative care as people age and get sick and that we are sensitive to our patients explicit and implicit needs for these discussions.”

Starting in 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services began paying physicians for advance care planning discussions with the approval of two new codes: 99497 and 99498. The codes pay about $86 for the first 30 minutes of a face-to-face conversation with a patient, family member, and/or surrogate and about $75 for additional sessions. Services can be furnished in both inpatient and ambulatory settings, and payment is not limited to particular physician specialties.

In 2016, health care professionals in New England (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont) billed Medicare 26,522 times for the advance care planning (ACP) codes for a total of 24,536 patients, which represented less than 1% of Medicare beneficiaries in New England at the time, according to Kimberly Pelland, MPH, of Healthcentric Advisors, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues. Most claims were billed in the office, followed by in nursing homes, and in hospitals; 40% of conversations occurred during an annual wellness visit (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8107).

Internists billed Medicare the most for ACP claims (65%), followed by family physicians (22%) gerontologists (5%), and oncologist/hematologists (0.3%), according to the analysis based on 2016 Medicare claims data and Census Bureau data. A greater proportion of patients with ACP claims were female, aged 85 years or older, enrolled in hospice, and died in the study year. Patients had higher odds of having an ACP claim if they were older and had lower income, and if they had cancer, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, or dementia. Male patients who were Asian, black, and Hispanic had lower chances of having an ACP claim.

In a related study, Emmanuelle Belanger, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues examined national Medicare data from 2016 to the third quarter of 2017. Across the United States, 2% of Medicare patients aged 65 years and older received advance care planning services that were billed under the ACP codes (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8615). Visits billed under the ACP codes increased from 538,275 to 633,214 during the same time period. Claim rates were higher among patients who died within the study period, reaching 3% in 2016 and 6% in 2017. The percentage of decedents with an ACP billed visit varied strongly across states, with states such as North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming having the fewest ACP visits billed and states such as California and Nevada having the most. ACP billed visits increased in all settings in 2017, but primarily in hospitals and nursing homes. Nationally, internists billed the codes most (48%), followed by family physicians (28%).

While the two studies indicate low usage of the ACP codes, many physicians are discussing advance care planning with their patients, said Mary M. Newman, MD, an internist based in Lutherville, Md., and former American College of Physicians adviser to the American Medical Association Relative Scale Value Update Committee (RUC).

“What cannot be captured by tracking under Medicare claims data are those shorter conversations that we have frequently,” Dr. Newman said in an interview. “If we have a short conversation about advance care planning, it gets folded into our evaluation and management visit. It’s not going to be separately billed.”

At the same time, some patients are not ready to discuss end-of-life options and decline the discussions when asked, Dr. Newman said. Particularly for healthier patients, end of life care is not a primary focus, she noted.

“Not everybody’s ready to have an advance care planning [discussion] that lasts 16-45 minutes,” she said. “Many people over age 65 are not ready to deal with advance care planning in their day-to-day lives, and it may not be what they wish to discuss. I offer the option to patients and some say, ‘Yes, I’d love to,’ and others decline or postpone.”

Low usage of the ACP codes may be associated with lack of awareness, uncertainty about appropriate code use, or associated billing that is not part of the standard workflow, Ankita Mehta, MD, of Mount Sinai in New York wrote an editorial accompanying the studies (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8105).

“Regardless, the low rates of utilization of ACP codes is alarming and highlights the need to create strategies to integrate ACP discussions into standard practice and build ACP documentation and billing in clinical workflow,” Dr. Mehta said.

Dr. Newman agreed that more education among physicians is needed.

“The amount of education clinicians have received varies tremendously across the geography of the country,” she said. “I think the codes are going to be slowly adopted. The challenge to us is to make sure we’re all better educated on palliative care as people age and get sick and that we are sensitive to our patients explicit and implicit needs for these discussions.”

Starting in 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services began paying physicians for advance care planning discussions with the approval of two new codes: 99497 and 99498. The codes pay about $86 for the first 30 minutes of a face-to-face conversation with a patient, family member, and/or surrogate and about $75 for additional sessions. Services can be furnished in both inpatient and ambulatory settings, and payment is not limited to particular physician specialties.

In 2016, health care professionals in New England (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont) billed Medicare 26,522 times for the advance care planning (ACP) codes for a total of 24,536 patients, which represented less than 1% of Medicare beneficiaries in New England at the time, according to Kimberly Pelland, MPH, of Healthcentric Advisors, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues. Most claims were billed in the office, followed by in nursing homes, and in hospitals; 40% of conversations occurred during an annual wellness visit (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8107).

Internists billed Medicare the most for ACP claims (65%), followed by family physicians (22%) gerontologists (5%), and oncologist/hematologists (0.3%), according to the analysis based on 2016 Medicare claims data and Census Bureau data. A greater proportion of patients with ACP claims were female, aged 85 years or older, enrolled in hospice, and died in the study year. Patients had higher odds of having an ACP claim if they were older and had lower income, and if they had cancer, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, or dementia. Male patients who were Asian, black, and Hispanic had lower chances of having an ACP claim.

In a related study, Emmanuelle Belanger, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her colleagues examined national Medicare data from 2016 to the third quarter of 2017. Across the United States, 2% of Medicare patients aged 65 years and older received advance care planning services that were billed under the ACP codes (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8615). Visits billed under the ACP codes increased from 538,275 to 633,214 during the same time period. Claim rates were higher among patients who died within the study period, reaching 3% in 2016 and 6% in 2017. The percentage of decedents with an ACP billed visit varied strongly across states, with states such as North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming having the fewest ACP visits billed and states such as California and Nevada having the most. ACP billed visits increased in all settings in 2017, but primarily in hospitals and nursing homes. Nationally, internists billed the codes most (48%), followed by family physicians (28%).

While the two studies indicate low usage of the ACP codes, many physicians are discussing advance care planning with their patients, said Mary M. Newman, MD, an internist based in Lutherville, Md., and former American College of Physicians adviser to the American Medical Association Relative Scale Value Update Committee (RUC).

“What cannot be captured by tracking under Medicare claims data are those shorter conversations that we have frequently,” Dr. Newman said in an interview. “If we have a short conversation about advance care planning, it gets folded into our evaluation and management visit. It’s not going to be separately billed.”

At the same time, some patients are not ready to discuss end-of-life options and decline the discussions when asked, Dr. Newman said. Particularly for healthier patients, end of life care is not a primary focus, she noted.

“Not everybody’s ready to have an advance care planning [discussion] that lasts 16-45 minutes,” she said. “Many people over age 65 are not ready to deal with advance care planning in their day-to-day lives, and it may not be what they wish to discuss. I offer the option to patients and some say, ‘Yes, I’d love to,’ and others decline or postpone.”

Low usage of the ACP codes may be associated with lack of awareness, uncertainty about appropriate code use, or associated billing that is not part of the standard workflow, Ankita Mehta, MD, of Mount Sinai in New York wrote an editorial accompanying the studies (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 March 11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8105).

“Regardless, the low rates of utilization of ACP codes is alarming and highlights the need to create strategies to integrate ACP discussions into standard practice and build ACP documentation and billing in clinical workflow,” Dr. Mehta said.

Dr. Newman agreed that more education among physicians is needed.

“The amount of education clinicians have received varies tremendously across the geography of the country,” she said. “I think the codes are going to be slowly adopted. The challenge to us is to make sure we’re all better educated on palliative care as people age and get sick and that we are sensitive to our patients explicit and implicit needs for these discussions.”

Prior authorization an increasing burden

The use of prior authorization for prescriptions and medical services has continued to increase in recent years, despite the consequences to continuity of care, according to a survey by the American Medical Association.

and 41% said that PA for medical services has done the same. The corresponding numbers for 5-year decreases in PAs were 2% and 1%, the AMA reported March 12.

Results of the survey, conducted in December 2018, also show that 85% of physicians believe that prior authorization sometimes, often, or always has a negative effect on the continuity of patients’ care. Almost 70% of respondents said that it is somewhat or extremely difficult to determine when PA is required for a prescription or medical service, and only 8% reported contracting with a health plan that offers programs to exempt physicians from the PA process, the AMA said.

“Physicians follow insurance protocols for prior authorization that require faxing recurring paperwork, multiple phone calls, and hours spent on hold. At the same time, patients’ lives can hang in the balance until health plans decide if needed care will qualify for insurance coverage,” AMA President Barbara L. McAneny, MD, said in a statement.

In January 2018, two organizations representing insurers – America’s Health Insurance Plans and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association – signed onto a joint consensus statement with the AMA and other health care groups that provided five areas for improvement of the PA process. The current survey results show that “most health plans are not making meaningful progress on reforming the cumbersome prior authorization process,” the AMA said.

The use of prior authorization for prescriptions and medical services has continued to increase in recent years, despite the consequences to continuity of care, according to a survey by the American Medical Association.

and 41% said that PA for medical services has done the same. The corresponding numbers for 5-year decreases in PAs were 2% and 1%, the AMA reported March 12.

Results of the survey, conducted in December 2018, also show that 85% of physicians believe that prior authorization sometimes, often, or always has a negative effect on the continuity of patients’ care. Almost 70% of respondents said that it is somewhat or extremely difficult to determine when PA is required for a prescription or medical service, and only 8% reported contracting with a health plan that offers programs to exempt physicians from the PA process, the AMA said.

“Physicians follow insurance protocols for prior authorization that require faxing recurring paperwork, multiple phone calls, and hours spent on hold. At the same time, patients’ lives can hang in the balance until health plans decide if needed care will qualify for insurance coverage,” AMA President Barbara L. McAneny, MD, said in a statement.

In January 2018, two organizations representing insurers – America’s Health Insurance Plans and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association – signed onto a joint consensus statement with the AMA and other health care groups that provided five areas for improvement of the PA process. The current survey results show that “most health plans are not making meaningful progress on reforming the cumbersome prior authorization process,” the AMA said.

The use of prior authorization for prescriptions and medical services has continued to increase in recent years, despite the consequences to continuity of care, according to a survey by the American Medical Association.

and 41% said that PA for medical services has done the same. The corresponding numbers for 5-year decreases in PAs were 2% and 1%, the AMA reported March 12.

Results of the survey, conducted in December 2018, also show that 85% of physicians believe that prior authorization sometimes, often, or always has a negative effect on the continuity of patients’ care. Almost 70% of respondents said that it is somewhat or extremely difficult to determine when PA is required for a prescription or medical service, and only 8% reported contracting with a health plan that offers programs to exempt physicians from the PA process, the AMA said.

“Physicians follow insurance protocols for prior authorization that require faxing recurring paperwork, multiple phone calls, and hours spent on hold. At the same time, patients’ lives can hang in the balance until health plans decide if needed care will qualify for insurance coverage,” AMA President Barbara L. McAneny, MD, said in a statement.

In January 2018, two organizations representing insurers – America’s Health Insurance Plans and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association – signed onto a joint consensus statement with the AMA and other health care groups that provided five areas for improvement of the PA process. The current survey results show that “most health plans are not making meaningful progress on reforming the cumbersome prior authorization process,” the AMA said.

Hospitalist scheduling: A search for balance

Survey says ...

Scheduling. Has there ever been such a simple word that is so complex? A simple Internet search of hospitalist scheduling returns thousands of possible discussions, leaving readers to conclude that the possibilities are endless and the challenges great. The answer certainly is not a one-size-fits-all approach.

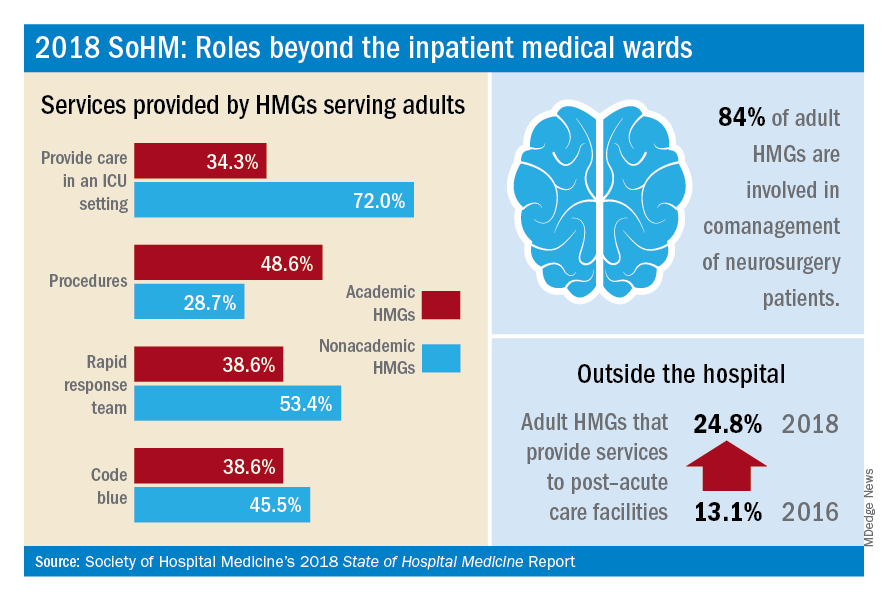

Hospitalist scheduling is one of the key sections in the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report; the 2018 report delves deeper into hospitalist scheduling than ever before.

For those of you who have been regular users of prior SoHM reports, you should be pleasantly surprised to find new comparative values: There are nearly 50% more pages dedicated just to scheduling!

For those readers who have never subscribed to the SoHM Report, this is your chance to study how other groups approach hospitalist schedules.

Why is hospitalist scheduling such a hot topic? For one, flexible and sustainable scheduling is an important contributor to job satisfaction. It is important for hospitalists to have a high degree of input into managing and effecting change for personal work-life balance.

As John Nelson, MD, MHM, a cofounder of the Society of Hospital Medicine, wrote recently in The Hospitalist, “an optimal schedule alone isn’t the key to preventing it [burnout], but maybe a good schedule can reduce your risk you’ll suffer from it.”

Secondly, ensuring that the hospitalist team is right sized – that is, scheduling hospitalists in the right place at the right time – is an art. Using resources, such as the 2018 SoHM report, to identify quantifiable comparisons enables hospitalist groups to continuously ensure the hospitalist schedule meets the clinical demands while optimizing the hospitalist group’s schedule.

Unfilled positions

The 2018 SoHM report features a new section on unfilled positions that may provide insight and better understanding about how your group compares to others, as it relates to properly evaluating your recruitment pipeline.

For hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving adults only, two out of three groups have unfilled positions, and about half of pediatric-only hospitalist groups have unfilled positions. Andrew White, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, provided us with a deep-dive discussion of this topic in a recent article in The Hospitalist.

If your group has historically had more unfilled positions than the respondents, it might mean your group should consider different strategies to close the gap. It may also lead to conversations about how to rethink the schedule to better meet the demands of clinical care with limited resources.

So, with all these unfilled positions, how are hospitalist groups filling the gap? Not all groups are using locum tenens to fill those unfilled positions. About a third of hospitalist groups reported leaving those gaps uncovered.

The most commonly reported tactic to fill in the gaps was voluntary extra shifts by existing hospitalists (physicians and/or nurse practioners/physician assistants). This approach is used by 70% of hospitalist groups. The second most-used tactic was “moonlighters” or PRN physicians (57.4%). Thirdly, was use of locum tenens physicians.

With these baselines, we will be able to better track and trend the industry going forward.

Scheduling methodologies

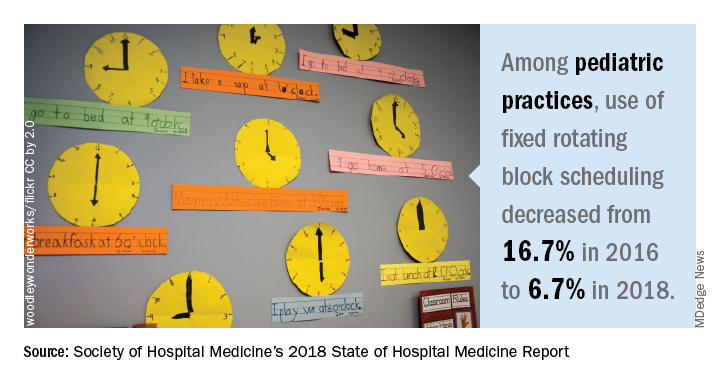

For pediatric practices, the fixed rotating block scheduling has decreased over the two survey periods (16.7% versus 6.7%).

Even though the 7-on/7-off schedule remains quite popular among adult-only HMGs, many seasoned hospitalists wonder whether this is sustainable through all seasons of life. Some hospitalists have said a 7-on/7-off schedule is like turning on and off your personal life and that it takes a day or 2 to recover from 7 consecutive 12-hour days.

On the other hand, a fixed schedule is the easiest to explain, and many new hospitalists are requesting a fixed schedule. Even so, a fixed schedule may not allow for enough flexibility to adapt the schedule to the demands of patient care.

Nonetheless, a fixed schedule remains a very popular scheduling pattern. Does this scheduling model lead to burnout? Does this scheduling model increase or decrease elasticity? The debate of flexible versus fixed schedules continues!

Results by shift type

Very simply, the length of individual shifts has not changed much in prior years. For adult-only practices, most all day and night shifts are 12 hours in length. For pediatric-only HMGs, most day shifts are about 10 hours, and most night shifts are about 13 hours.

Most evening or swing shifts for adult-only practices are about 10 hours, which is a slight decrease from 2016. Pediatric-only practices’ evening shifts are about 8 hours in length.

A new question this year is about daytime admitters. For adult hospitalist groups, over half of groups have daytime admitters. For pediatric groups, nearly three out of four groups have daytime dedicated admitters. Also, the larger the group size, the more likely it is to have a dedicated daytime admitter.

Nocturnists remain in demand! Over 80% of adult hospitalist groups have on-site hospitalists at night. About a quarter of pediatric-only practices have nocturnists.

Scheduled workload distribution

One way of scheduling patient assignments is the phenomenon of unit-based assignments, or geographic rounding. As this has become more prevalent, the SHM Practice Analysis Committee recommended adding a question about unit-based assignments to the 2018 SoHM report.

The adoption of unit-based assignments is higher in academic groups (54.3%), as well as among hospitalists employed at a “hospital, health system or integrated delivery system” (47.4%), than in other group practice models.

Just as with the presence of daytime admitters, the larger the group the more likely it has some form of unit-based assignments. Further study would be needed to determine whether there is a link between the presence of daytime admitters and successful unit-based assignments for daytime rounders.

What’s the verdict?

Hospitalist scheduling will continue to evolve. It’s a never-ending balance of what’s best for patients and what’s best for hospitalists (and likely many other key stakeholders).

Scheduling is personal. Scheduling is an art form. The biggest question in this topic area is: Has anyone figured out the ‘secret sauce’ to hospitalist scheduling? Go online to SHM’s HMX to start the discussion!

Ms. Trask is national vice president of the Hospital Medicine Service Line at Catholic Health Initiatives in Englewood, Colo. She is also a member of The Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

Survey says ...

Survey says ...

Scheduling. Has there ever been such a simple word that is so complex? A simple Internet search of hospitalist scheduling returns thousands of possible discussions, leaving readers to conclude that the possibilities are endless and the challenges great. The answer certainly is not a one-size-fits-all approach.

Hospitalist scheduling is one of the key sections in the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report; the 2018 report delves deeper into hospitalist scheduling than ever before.

For those of you who have been regular users of prior SoHM reports, you should be pleasantly surprised to find new comparative values: There are nearly 50% more pages dedicated just to scheduling!

For those readers who have never subscribed to the SoHM Report, this is your chance to study how other groups approach hospitalist schedules.

Why is hospitalist scheduling such a hot topic? For one, flexible and sustainable scheduling is an important contributor to job satisfaction. It is important for hospitalists to have a high degree of input into managing and effecting change for personal work-life balance.

As John Nelson, MD, MHM, a cofounder of the Society of Hospital Medicine, wrote recently in The Hospitalist, “an optimal schedule alone isn’t the key to preventing it [burnout], but maybe a good schedule can reduce your risk you’ll suffer from it.”

Secondly, ensuring that the hospitalist team is right sized – that is, scheduling hospitalists in the right place at the right time – is an art. Using resources, such as the 2018 SoHM report, to identify quantifiable comparisons enables hospitalist groups to continuously ensure the hospitalist schedule meets the clinical demands while optimizing the hospitalist group’s schedule.

Unfilled positions

The 2018 SoHM report features a new section on unfilled positions that may provide insight and better understanding about how your group compares to others, as it relates to properly evaluating your recruitment pipeline.

For hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving adults only, two out of three groups have unfilled positions, and about half of pediatric-only hospitalist groups have unfilled positions. Andrew White, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, provided us with a deep-dive discussion of this topic in a recent article in The Hospitalist.

If your group has historically had more unfilled positions than the respondents, it might mean your group should consider different strategies to close the gap. It may also lead to conversations about how to rethink the schedule to better meet the demands of clinical care with limited resources.

So, with all these unfilled positions, how are hospitalist groups filling the gap? Not all groups are using locum tenens to fill those unfilled positions. About a third of hospitalist groups reported leaving those gaps uncovered.

The most commonly reported tactic to fill in the gaps was voluntary extra shifts by existing hospitalists (physicians and/or nurse practioners/physician assistants). This approach is used by 70% of hospitalist groups. The second most-used tactic was “moonlighters” or PRN physicians (57.4%). Thirdly, was use of locum tenens physicians.

With these baselines, we will be able to better track and trend the industry going forward.

Scheduling methodologies

For pediatric practices, the fixed rotating block scheduling has decreased over the two survey periods (16.7% versus 6.7%).

Even though the 7-on/7-off schedule remains quite popular among adult-only HMGs, many seasoned hospitalists wonder whether this is sustainable through all seasons of life. Some hospitalists have said a 7-on/7-off schedule is like turning on and off your personal life and that it takes a day or 2 to recover from 7 consecutive 12-hour days.

On the other hand, a fixed schedule is the easiest to explain, and many new hospitalists are requesting a fixed schedule. Even so, a fixed schedule may not allow for enough flexibility to adapt the schedule to the demands of patient care.

Nonetheless, a fixed schedule remains a very popular scheduling pattern. Does this scheduling model lead to burnout? Does this scheduling model increase or decrease elasticity? The debate of flexible versus fixed schedules continues!

Results by shift type

Very simply, the length of individual shifts has not changed much in prior years. For adult-only practices, most all day and night shifts are 12 hours in length. For pediatric-only HMGs, most day shifts are about 10 hours, and most night shifts are about 13 hours.

Most evening or swing shifts for adult-only practices are about 10 hours, which is a slight decrease from 2016. Pediatric-only practices’ evening shifts are about 8 hours in length.

A new question this year is about daytime admitters. For adult hospitalist groups, over half of groups have daytime admitters. For pediatric groups, nearly three out of four groups have daytime dedicated admitters. Also, the larger the group size, the more likely it is to have a dedicated daytime admitter.

Nocturnists remain in demand! Over 80% of adult hospitalist groups have on-site hospitalists at night. About a quarter of pediatric-only practices have nocturnists.

Scheduled workload distribution

One way of scheduling patient assignments is the phenomenon of unit-based assignments, or geographic rounding. As this has become more prevalent, the SHM Practice Analysis Committee recommended adding a question about unit-based assignments to the 2018 SoHM report.

The adoption of unit-based assignments is higher in academic groups (54.3%), as well as among hospitalists employed at a “hospital, health system or integrated delivery system” (47.4%), than in other group practice models.

Just as with the presence of daytime admitters, the larger the group the more likely it has some form of unit-based assignments. Further study would be needed to determine whether there is a link between the presence of daytime admitters and successful unit-based assignments for daytime rounders.

What’s the verdict?

Hospitalist scheduling will continue to evolve. It’s a never-ending balance of what’s best for patients and what’s best for hospitalists (and likely many other key stakeholders).

Scheduling is personal. Scheduling is an art form. The biggest question in this topic area is: Has anyone figured out the ‘secret sauce’ to hospitalist scheduling? Go online to SHM’s HMX to start the discussion!

Ms. Trask is national vice president of the Hospital Medicine Service Line at Catholic Health Initiatives in Englewood, Colo. She is also a member of The Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

Scheduling. Has there ever been such a simple word that is so complex? A simple Internet search of hospitalist scheduling returns thousands of possible discussions, leaving readers to conclude that the possibilities are endless and the challenges great. The answer certainly is not a one-size-fits-all approach.

Hospitalist scheduling is one of the key sections in the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report; the 2018 report delves deeper into hospitalist scheduling than ever before.

For those of you who have been regular users of prior SoHM reports, you should be pleasantly surprised to find new comparative values: There are nearly 50% more pages dedicated just to scheduling!

For those readers who have never subscribed to the SoHM Report, this is your chance to study how other groups approach hospitalist schedules.

Why is hospitalist scheduling such a hot topic? For one, flexible and sustainable scheduling is an important contributor to job satisfaction. It is important for hospitalists to have a high degree of input into managing and effecting change for personal work-life balance.

As John Nelson, MD, MHM, a cofounder of the Society of Hospital Medicine, wrote recently in The Hospitalist, “an optimal schedule alone isn’t the key to preventing it [burnout], but maybe a good schedule can reduce your risk you’ll suffer from it.”

Secondly, ensuring that the hospitalist team is right sized – that is, scheduling hospitalists in the right place at the right time – is an art. Using resources, such as the 2018 SoHM report, to identify quantifiable comparisons enables hospitalist groups to continuously ensure the hospitalist schedule meets the clinical demands while optimizing the hospitalist group’s schedule.

Unfilled positions

The 2018 SoHM report features a new section on unfilled positions that may provide insight and better understanding about how your group compares to others, as it relates to properly evaluating your recruitment pipeline.

For hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving adults only, two out of three groups have unfilled positions, and about half of pediatric-only hospitalist groups have unfilled positions. Andrew White, MD, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, provided us with a deep-dive discussion of this topic in a recent article in The Hospitalist.

If your group has historically had more unfilled positions than the respondents, it might mean your group should consider different strategies to close the gap. It may also lead to conversations about how to rethink the schedule to better meet the demands of clinical care with limited resources.

So, with all these unfilled positions, how are hospitalist groups filling the gap? Not all groups are using locum tenens to fill those unfilled positions. About a third of hospitalist groups reported leaving those gaps uncovered.

The most commonly reported tactic to fill in the gaps was voluntary extra shifts by existing hospitalists (physicians and/or nurse practioners/physician assistants). This approach is used by 70% of hospitalist groups. The second most-used tactic was “moonlighters” or PRN physicians (57.4%). Thirdly, was use of locum tenens physicians.

With these baselines, we will be able to better track and trend the industry going forward.

Scheduling methodologies

For pediatric practices, the fixed rotating block scheduling has decreased over the two survey periods (16.7% versus 6.7%).

Even though the 7-on/7-off schedule remains quite popular among adult-only HMGs, many seasoned hospitalists wonder whether this is sustainable through all seasons of life. Some hospitalists have said a 7-on/7-off schedule is like turning on and off your personal life and that it takes a day or 2 to recover from 7 consecutive 12-hour days.

On the other hand, a fixed schedule is the easiest to explain, and many new hospitalists are requesting a fixed schedule. Even so, a fixed schedule may not allow for enough flexibility to adapt the schedule to the demands of patient care.

Nonetheless, a fixed schedule remains a very popular scheduling pattern. Does this scheduling model lead to burnout? Does this scheduling model increase or decrease elasticity? The debate of flexible versus fixed schedules continues!

Results by shift type

Very simply, the length of individual shifts has not changed much in prior years. For adult-only practices, most all day and night shifts are 12 hours in length. For pediatric-only HMGs, most day shifts are about 10 hours, and most night shifts are about 13 hours.

Most evening or swing shifts for adult-only practices are about 10 hours, which is a slight decrease from 2016. Pediatric-only practices’ evening shifts are about 8 hours in length.

A new question this year is about daytime admitters. For adult hospitalist groups, over half of groups have daytime admitters. For pediatric groups, nearly three out of four groups have daytime dedicated admitters. Also, the larger the group size, the more likely it is to have a dedicated daytime admitter.

Nocturnists remain in demand! Over 80% of adult hospitalist groups have on-site hospitalists at night. About a quarter of pediatric-only practices have nocturnists.

Scheduled workload distribution

One way of scheduling patient assignments is the phenomenon of unit-based assignments, or geographic rounding. As this has become more prevalent, the SHM Practice Analysis Committee recommended adding a question about unit-based assignments to the 2018 SoHM report.

The adoption of unit-based assignments is higher in academic groups (54.3%), as well as among hospitalists employed at a “hospital, health system or integrated delivery system” (47.4%), than in other group practice models.

Just as with the presence of daytime admitters, the larger the group the more likely it has some form of unit-based assignments. Further study would be needed to determine whether there is a link between the presence of daytime admitters and successful unit-based assignments for daytime rounders.

What’s the verdict?

Hospitalist scheduling will continue to evolve. It’s a never-ending balance of what’s best for patients and what’s best for hospitalists (and likely many other key stakeholders).

Scheduling is personal. Scheduling is an art form. The biggest question in this topic area is: Has anyone figured out the ‘secret sauce’ to hospitalist scheduling? Go online to SHM’s HMX to start the discussion!

Ms. Trask is national vice president of the Hospital Medicine Service Line at Catholic Health Initiatives in Englewood, Colo. She is also a member of The Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

Groups of physicians produce more accurate diagnoses than individuals

Groups of physicians and trainees diagnose clinical cases with more accuracy than individuals, according to a study of solo and aggregate diagnoses collected through an online medical teaching platform.

“These findings suggest that using the concept of collective intelligence to pool many physicians’ diagnoses could be a scalable approach to improve diagnostic accuracy,” wrote lead author Michael L. Barnett, MD, of Harvard University in Boston and his coauthors, adding that “groups of all sizes outperformed individual subspecialists on cases in their own subspecialty.” The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

This cross-sectional study examined 1,572 cases solved within the Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) system, an online platform for authoring and diagnosing teaching cases. The system presents real-life cases from clinical practices and asks respondents to generate ranked differential diagnoses. Cases are tagged for specialties based on both intended diagnoses and the top diagnoses chosen by respondents. All cases used in this study were authored between May 7, 2014, and October 5, 2016, and had 10 or more respondents.

Of the 2,069 attending physicians and fellows, residents, and medical students (users) who solved cases within the Human Dx system, 1,452 (70.2%) were trained in internal medicine, 1,228 (59.4%) were residents or fellows, 431 (20.8%) were attending physicians, and 410 (19.8%) were medical students. To create a collective differential, Dr. Barnett and his colleagues aggregated the responses of up to nine participants via a weighted combination of each clinician’s top three diagnoses, which they dubbed “collective intelligence.”

The diagnostic accuracy for groups of nine was 85.6% (95% confidence interval, 83.9%-87.4%), compared with individual users at 62.5% (95% CI, 60.1%-64.9%), a difference of 23% (95% CI, 14.9%-31.2%; P less than .001). Groups of five saw a 17.8% difference in accuracy versus an individual (95% CI, 14.0%-21.6%; P less than .001), compared with 12.5% for groups of two (95% CI, 9.3%-15.8%; P less than .001). Taken together, these seem to underline an association between larger groups and increased accuracy.

Individual specialists solved cases in their particular areas with a diagnostic accuracy of 66.3% (95% CI, 59.1%-73.5%), compared with nonmatched specialty accuracy of 63.9% (95% CI, 56.6%-71.2%). Groups, however, outperformed specialists across the board: 77.7% accuracy for a group of 2 (95% CI, 70.1%-84.6%; P less than .001) and 85.5% accuracy for a group of 9 (95% CI, 75.1%-95.9%; P less than .001).

The coauthors shared the limitations of their study, including the possibility that the users who contributed these cases to Human Dx may not be representative of the medical community as a whole. They also noted that, while their 431 attending physicians constituted the “largest number ... to date in a study of collective intelligence,” trainees still made up almost 80% of users. In addition, they acknowledged that Human Dx was not designed to generate collective diagnoses nor assess collective intelligence; another platform created with that ability in mind may have returned different results. Finally, they were unable to assess how exactly greater accuracy would have been linked to changes in treatment, calling it “an important question for future work.”

The authors disclosed several conflicts of interest. One doctor reported receiving personal fees from Greylock McKinnon Associates; another reported receiving personal fees from the Human Diagnosis Project and serving as their nonprofit director during the study. A third doctor reported consulting for a company that makes patient-safety monitoring systems and receiving compensation from a not-for-profit incubator, along with having equity in three medical data and software companies.

SOURCE: Barnett ML et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0096.

Although this study from Barnett et al. is not the silver bullet for misdiagnosis, better understanding why physicians make mistakes is a necessary and valuable undertaking, according to Stephan D. Fihn, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle.

In the past, the “correct” diagnostic approach included making a list of potential diagnoses and systematically ruling them out one by one, a process conveyed via clinicopathologic conferences in teaching hospitals. These, Dr. Fihn recalled, lasted until medical educators recognized them as “more ... theatrical events than meaningful teaching exercises” and understood that master clinicians did not actually think in the manner this approach modeled. Since then, the maturation of cognitive psychology and “a growing literature” have made diagnostic error seem like a common, sometimes unavoidable element of being human.

What can be done? Computers have always been a possibility, but “none have achieved the breadth of content and accuracy necessary to be adopted to any great extent,” Dr. Fihn wrote. Another option is crowdsourcing, as described in this study from Barnett and colleagues. Their approach has its pitfalls: A 62.5% level of diagnostic accuracy from individuals is not very high, which suggests either difficult cases or a preponderance of inexperienced clinicians who may benefit from collective intelligence even more. Regardless, he stated, “clinicians need to be cognizant of their own inherent limitations and acknowledge fallibility”; being humble and willing to seek advice “remain important, albeit imperfect, antidotes to misdiagnosis.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1071 ). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Although this study from Barnett et al. is not the silver bullet for misdiagnosis, better understanding why physicians make mistakes is a necessary and valuable undertaking, according to Stephan D. Fihn, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle.

In the past, the “correct” diagnostic approach included making a list of potential diagnoses and systematically ruling them out one by one, a process conveyed via clinicopathologic conferences in teaching hospitals. These, Dr. Fihn recalled, lasted until medical educators recognized them as “more ... theatrical events than meaningful teaching exercises” and understood that master clinicians did not actually think in the manner this approach modeled. Since then, the maturation of cognitive psychology and “a growing literature” have made diagnostic error seem like a common, sometimes unavoidable element of being human.

What can be done? Computers have always been a possibility, but “none have achieved the breadth of content and accuracy necessary to be adopted to any great extent,” Dr. Fihn wrote. Another option is crowdsourcing, as described in this study from Barnett and colleagues. Their approach has its pitfalls: A 62.5% level of diagnostic accuracy from individuals is not very high, which suggests either difficult cases or a preponderance of inexperienced clinicians who may benefit from collective intelligence even more. Regardless, he stated, “clinicians need to be cognizant of their own inherent limitations and acknowledge fallibility”; being humble and willing to seek advice “remain important, albeit imperfect, antidotes to misdiagnosis.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1071 ). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Although this study from Barnett et al. is not the silver bullet for misdiagnosis, better understanding why physicians make mistakes is a necessary and valuable undertaking, according to Stephan D. Fihn, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle.

In the past, the “correct” diagnostic approach included making a list of potential diagnoses and systematically ruling them out one by one, a process conveyed via clinicopathologic conferences in teaching hospitals. These, Dr. Fihn recalled, lasted until medical educators recognized them as “more ... theatrical events than meaningful teaching exercises” and understood that master clinicians did not actually think in the manner this approach modeled. Since then, the maturation of cognitive psychology and “a growing literature” have made diagnostic error seem like a common, sometimes unavoidable element of being human.

What can be done? Computers have always been a possibility, but “none have achieved the breadth of content and accuracy necessary to be adopted to any great extent,” Dr. Fihn wrote. Another option is crowdsourcing, as described in this study from Barnett and colleagues. Their approach has its pitfalls: A 62.5% level of diagnostic accuracy from individuals is not very high, which suggests either difficult cases or a preponderance of inexperienced clinicians who may benefit from collective intelligence even more. Regardless, he stated, “clinicians need to be cognizant of their own inherent limitations and acknowledge fallibility”; being humble and willing to seek advice “remain important, albeit imperfect, antidotes to misdiagnosis.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1071 ). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Groups of physicians and trainees diagnose clinical cases with more accuracy than individuals, according to a study of solo and aggregate diagnoses collected through an online medical teaching platform.

“These findings suggest that using the concept of collective intelligence to pool many physicians’ diagnoses could be a scalable approach to improve diagnostic accuracy,” wrote lead author Michael L. Barnett, MD, of Harvard University in Boston and his coauthors, adding that “groups of all sizes outperformed individual subspecialists on cases in their own subspecialty.” The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

This cross-sectional study examined 1,572 cases solved within the Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) system, an online platform for authoring and diagnosing teaching cases. The system presents real-life cases from clinical practices and asks respondents to generate ranked differential diagnoses. Cases are tagged for specialties based on both intended diagnoses and the top diagnoses chosen by respondents. All cases used in this study were authored between May 7, 2014, and October 5, 2016, and had 10 or more respondents.