User login

The Hospitalist only

Nontraditional specialty physicians supplement hospitalist staffing

More HMGs cover inpatient and ED settings

Our profession continues to experience steady growth, and demand for hospitalist physicians exceeds supply. In a recent article in The Hospitalist, Andrew White, MD, SFHM, highlighted the fact that most hospital medicine groups (HMGs) are constantly recruiting and open positions are not uncommon.

When we think about recruitment and staffing, I bet many of us think principally of physicians trained in the general medicine specialties of internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics. Yet, to help meet demand for hospital-based clinicians, HMGs sometimes turn to physicians certified in emergency medicine, critical care, geriatric medicine, palliative care, and other fields.

To gain a better understanding of the diversity within our profession, the Society of Hospital Medicine’s State of Hospital Medicine survey asked HMGs whether they employ at least one physician in these various specialties. Results published in the recently released 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report show significant differences among groups, affected by location, group size, and type of employer.

At the core of our profession are physicians trained in internal medicine, present in 99.2% of adult medicine HMGs throughout the United States. No surprise given that our field was founded by internists and remains a popular career choice for IM residency graduates. Family physicians follow, with the highest percentage of groups employing at least one FP located in the southern United States at 70.3% and lowest in the west at 54.7%. Small-sized groups – fewer than 10 full-time equivalents (FTEs) – were also more likely to employ FPs.

This speaks to the challenge – often faced by smaller hospitals – of covering both adult and pediatric patient populations and limited workforce availability. Pediatrics- and internal medicine/pediatrics–trained physicians help meet this need and were prevalent within small-sized groups. Another distinction found in the report is that, while 92.1% of multistate hospitalist management companies employed family physicians, only 28.8% of academic university settings did so. Partly because of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for IM-certified teaching attending for internal medicine residents, FP and other specialties are filling some non–teaching hospitalist positions within our academic programs.

What may be surprising is that emergency medicine and critical care had the largest increase in representation in hospital medicine. The two specialties showed similar growth trends, with a larger presence in the South and Midwest states and 56% of multistate hospitalist management companies employing them. Small- to medium-sized groups of up to 20 FTEs were also more likely to have physicians from these fields, with up to 44% of groups doing so. This is a significant change from 2016, when less than 3.4% of all HMGs overall had a physician certified in emergency or critical care medicine.

This finding seems to coincide with the growth in hospital medicine groups who are covering both ED and inpatient services. For small and rural hospitals, it has become necessary and beneficial to have physicians capable of covering both clinical settings.

Contrast this with geriatric medicine and palliative care. Here, we saw these two specialties to be present in our academic institutions at 26.8% and 22.5%, respectively. Large-sized HMGs were more likely to employ them, whereas their presence in multistate management groups or private multispecialty/primary care groups was quite low. Compared with our last survey in 2016, their overall prevalence in HMGs hasn’t changed significantly. Whether this will be different in the future with our aging population will be interesting to follow.

Published biannually, the SoHM report provides insight into these and other market-based dynamics that shape hospital medicine. The demand for hospital-based clinicians and the demands of acute inpatient care are leading to the broad and inclusive nature of hospital medicine. Our staffing will continue to be met not only by internal medicine and family medicine physicians but also through these other specialties joining our ranks and adding diversity to our profession.

Dr. Sites is the executive medical director of acute medicine at Providence St. Joseph Health, Oregon, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. She leads the hospital medicine programs and is involved in strategy development and alignment of acute inpatient medicine services at eight member hospitals. She has been a practicing hospitalist for 20 years and volunteers on medical mission trips to Guatemala annually.

More HMGs cover inpatient and ED settings

More HMGs cover inpatient and ED settings

Our profession continues to experience steady growth, and demand for hospitalist physicians exceeds supply. In a recent article in The Hospitalist, Andrew White, MD, SFHM, highlighted the fact that most hospital medicine groups (HMGs) are constantly recruiting and open positions are not uncommon.

When we think about recruitment and staffing, I bet many of us think principally of physicians trained in the general medicine specialties of internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics. Yet, to help meet demand for hospital-based clinicians, HMGs sometimes turn to physicians certified in emergency medicine, critical care, geriatric medicine, palliative care, and other fields.

To gain a better understanding of the diversity within our profession, the Society of Hospital Medicine’s State of Hospital Medicine survey asked HMGs whether they employ at least one physician in these various specialties. Results published in the recently released 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report show significant differences among groups, affected by location, group size, and type of employer.

At the core of our profession are physicians trained in internal medicine, present in 99.2% of adult medicine HMGs throughout the United States. No surprise given that our field was founded by internists and remains a popular career choice for IM residency graduates. Family physicians follow, with the highest percentage of groups employing at least one FP located in the southern United States at 70.3% and lowest in the west at 54.7%. Small-sized groups – fewer than 10 full-time equivalents (FTEs) – were also more likely to employ FPs.

This speaks to the challenge – often faced by smaller hospitals – of covering both adult and pediatric patient populations and limited workforce availability. Pediatrics- and internal medicine/pediatrics–trained physicians help meet this need and were prevalent within small-sized groups. Another distinction found in the report is that, while 92.1% of multistate hospitalist management companies employed family physicians, only 28.8% of academic university settings did so. Partly because of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for IM-certified teaching attending for internal medicine residents, FP and other specialties are filling some non–teaching hospitalist positions within our academic programs.

What may be surprising is that emergency medicine and critical care had the largest increase in representation in hospital medicine. The two specialties showed similar growth trends, with a larger presence in the South and Midwest states and 56% of multistate hospitalist management companies employing them. Small- to medium-sized groups of up to 20 FTEs were also more likely to have physicians from these fields, with up to 44% of groups doing so. This is a significant change from 2016, when less than 3.4% of all HMGs overall had a physician certified in emergency or critical care medicine.

This finding seems to coincide with the growth in hospital medicine groups who are covering both ED and inpatient services. For small and rural hospitals, it has become necessary and beneficial to have physicians capable of covering both clinical settings.

Contrast this with geriatric medicine and palliative care. Here, we saw these two specialties to be present in our academic institutions at 26.8% and 22.5%, respectively. Large-sized HMGs were more likely to employ them, whereas their presence in multistate management groups or private multispecialty/primary care groups was quite low. Compared with our last survey in 2016, their overall prevalence in HMGs hasn’t changed significantly. Whether this will be different in the future with our aging population will be interesting to follow.

Published biannually, the SoHM report provides insight into these and other market-based dynamics that shape hospital medicine. The demand for hospital-based clinicians and the demands of acute inpatient care are leading to the broad and inclusive nature of hospital medicine. Our staffing will continue to be met not only by internal medicine and family medicine physicians but also through these other specialties joining our ranks and adding diversity to our profession.

Dr. Sites is the executive medical director of acute medicine at Providence St. Joseph Health, Oregon, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. She leads the hospital medicine programs and is involved in strategy development and alignment of acute inpatient medicine services at eight member hospitals. She has been a practicing hospitalist for 20 years and volunteers on medical mission trips to Guatemala annually.

Our profession continues to experience steady growth, and demand for hospitalist physicians exceeds supply. In a recent article in The Hospitalist, Andrew White, MD, SFHM, highlighted the fact that most hospital medicine groups (HMGs) are constantly recruiting and open positions are not uncommon.

When we think about recruitment and staffing, I bet many of us think principally of physicians trained in the general medicine specialties of internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics. Yet, to help meet demand for hospital-based clinicians, HMGs sometimes turn to physicians certified in emergency medicine, critical care, geriatric medicine, palliative care, and other fields.

To gain a better understanding of the diversity within our profession, the Society of Hospital Medicine’s State of Hospital Medicine survey asked HMGs whether they employ at least one physician in these various specialties. Results published in the recently released 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report show significant differences among groups, affected by location, group size, and type of employer.

At the core of our profession are physicians trained in internal medicine, present in 99.2% of adult medicine HMGs throughout the United States. No surprise given that our field was founded by internists and remains a popular career choice for IM residency graduates. Family physicians follow, with the highest percentage of groups employing at least one FP located in the southern United States at 70.3% and lowest in the west at 54.7%. Small-sized groups – fewer than 10 full-time equivalents (FTEs) – were also more likely to employ FPs.

This speaks to the challenge – often faced by smaller hospitals – of covering both adult and pediatric patient populations and limited workforce availability. Pediatrics- and internal medicine/pediatrics–trained physicians help meet this need and were prevalent within small-sized groups. Another distinction found in the report is that, while 92.1% of multistate hospitalist management companies employed family physicians, only 28.8% of academic university settings did so. Partly because of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for IM-certified teaching attending for internal medicine residents, FP and other specialties are filling some non–teaching hospitalist positions within our academic programs.

What may be surprising is that emergency medicine and critical care had the largest increase in representation in hospital medicine. The two specialties showed similar growth trends, with a larger presence in the South and Midwest states and 56% of multistate hospitalist management companies employing them. Small- to medium-sized groups of up to 20 FTEs were also more likely to have physicians from these fields, with up to 44% of groups doing so. This is a significant change from 2016, when less than 3.4% of all HMGs overall had a physician certified in emergency or critical care medicine.

This finding seems to coincide with the growth in hospital medicine groups who are covering both ED and inpatient services. For small and rural hospitals, it has become necessary and beneficial to have physicians capable of covering both clinical settings.

Contrast this with geriatric medicine and palliative care. Here, we saw these two specialties to be present in our academic institutions at 26.8% and 22.5%, respectively. Large-sized HMGs were more likely to employ them, whereas their presence in multistate management groups or private multispecialty/primary care groups was quite low. Compared with our last survey in 2016, their overall prevalence in HMGs hasn’t changed significantly. Whether this will be different in the future with our aging population will be interesting to follow.

Published biannually, the SoHM report provides insight into these and other market-based dynamics that shape hospital medicine. The demand for hospital-based clinicians and the demands of acute inpatient care are leading to the broad and inclusive nature of hospital medicine. Our staffing will continue to be met not only by internal medicine and family medicine physicians but also through these other specialties joining our ranks and adding diversity to our profession.

Dr. Sites is the executive medical director of acute medicine at Providence St. Joseph Health, Oregon, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. She leads the hospital medicine programs and is involved in strategy development and alignment of acute inpatient medicine services at eight member hospitals. She has been a practicing hospitalist for 20 years and volunteers on medical mission trips to Guatemala annually.

In search of high-value care

Six steps that can help your team

U.S. spending on health care is growing rapidly and expected to reach 19.7% of gross domestic product by 2026.1 In response, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and national organizations such as the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) and the American College of Physicians (ACP) have launched initiatives to ensure that the value being delivered to patients is on par with the escalating cost of care.

Over the past 10 years, I have led and advised hundreds of small- and large-scale projects that focused on improving patient care quality and cost. Below, I share what I, along with other leaders in high-value care, have observed that it takes to implement successful and lasting improvements – for the benefit of patients and hospitals.

A brief history of high-value care

When compared to other wealthy countries, the United States spends disproportionately more money on health care. In 2016, U.S. health care spending was $3.3 trillion1, or $10,348 per person.2 Hospital care alone was responsible for a third of health spending and amounted to $1.1 trillion in 20161. By 2026, national health spending is projected to reach $5.7 trillion1.

In response to escalating health care costs, CMS and other payers have shifted toward value-based reimbursements that tie payments to health care facilities and clinicians to their performance on selected quality, cost, and efficiency measures. For example, under the CMS Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), 5% of clinicians’ revenue in 2020 is tied to their 2018 performance in four categories: Quality, Cost, Improvement Activities, and Promoting Interoperability. The percentage of revenue at risk will increase to 9% in 2022, based on 2020 performance.

Rising health care costs put a burden not just on the federal and state budgets, but on individual and family budgets as well. Out-of-pocket spending grew 3.9% in 2016 to $352.5 billion1 and is expected to increase in the future. High health care costs rightfully bring into question the value individual consumers of health care services are getting in return. If value is defined as the level of benefit achieved for a given cost, what is high-value care? The 2013 Institute of Medicine report3 defined high-value care as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.” It goes beyond a set of quality and cost measures used by payers to affect provider reimbursement and is driven by day-to-day individual providers’ decisions that affect individual patients’ outcomes and their cost of care.

High-value care has been embraced by national organizations. In 2012, the ABIM Foundation launched the Choosing Wisely initiative to support and promote conversations between clinicians and patients in choosing care that is truly necessary, supported by evidence, and free from harm. The result was an evidence-based list of recommendations from 540 specialty societies, including the Society of Hospital Medicine. The SHM – Adult Hospital Medicine list4 features the following “Five things physicians and patients should question”:

- Don’t place, or leave in place, urinary catheters for incontinence or convenience or monitoring of output for non–critically ill patients.

- Don’t prescribe medications for stress ulcer prophylaxis to medical inpatients unless at high risk for GI complications.

- Avoid transfusions of red blood cells for arbitrary hemoglobin or hematocrit thresholds and in the absence of symptoms of active coronary disease, heart failure, or stroke.

- Don’t order continuous telemetry monitoring outside of the ICU without using a protocol that governs continuation.

- Don’t perform repetitive CBC and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.

The ACP launched a high-value care initiative that offers learning resources for clinicians and medical educators, clinical guidelines, and best practice advice. In 2012, a workgroup of internists convened by ACP developed a list of 37 clinical situations in which medical tests are commonly used but do not provide high value.5 Seven of those situations are applicable to adult hospital medicine.

High-value care today: What the experts say

More than 5 years later, what progress have hospitalists made in adopting high-value care practices? To answer this and other questions, I reached out to three national experts in high-value care in hospital medicine: Amit Pahwa, MD, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and a course director of “Topics in interdisciplinary medicine: High-value health care”; Christopher Petrilli, MD, clinical assistant professor in the department of medicine at New York University Langone Health and clinical lead, Manhattan campus, value-based management; and Charlie Wray, DO, MS, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California in San Francisco and a coauthor of an article on high-value care in hospital medicine published recently in the Journal of General Internal Medicine6.

The experts agree that awareness of high-value care among practicing physicians and medical trainees has increased in the last few years. Major professional publications have highlighted the topic, including The Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do For No Reason” series, JAMA’s “Teachable Moments,” and the American Journal of Medicine’s recurring column dedicated to high-value care practice. Leading teaching institutions have built high-value care curricula as a part of their medical student and resident training. However, widespread adoption has been slow and sometimes difficult.

The barriers to adoption of high-value practices among hospitalists are numerous and deep rooted in historical practices and culture. As Dr. Petrilli said, the “culture of overordering [diagnostic tests] is hard to break.” Hospitalists may not have well-developed relationships with patients, or time to explain why some tests or treatments are unnecessary. There is a lack of cost transparency, including the cost of the tests themselves and the downstream costs of additional tests and follow-ups. The best intended interventions fail to produce durable change unless they are seamlessly integrated into a hospitalist’s daily workflow.

Six steps to implementing a successful high-value care initiative

What can hospitalists do to improve the value of care they provide to their patients and hospital partners?

1. Identify high-value care opportunities at your hospital.

Dr. Wray pointed out that “all high-value care is local.” Start by looking at the national guidelines and talking to your senior clinical leaders and colleagues. Review your hospital data to identify opportunities and understand the root causes, including variability among providers.

If you choose to analyze and present provider-specific data, first be transparent on why you are doing that. Your goal is not to tell physicians how to practice or to score them, but instead, to promote adoption of evidence-based high-value care by identifying and discussing provider practice variations, and to generate possible solutions. Second, make sure that the data you present is credible and trustworthy by clearly outlining the data source, time frame, sample size per provider, any inclusion and exclusion criteria, attribution logic, and severity adjustment methodology. Third, expect initial pushback as transparency and change can be scary. But most doctors are inherently competitive and will want to be the best at caring for their patients.

2. Assemble the team.

Identify an executive sponsor – a senior clinical executive (for example, the chief medical officer or vice president of medical affairs) whose role is to help engage stakeholders, secure resources, and remove barriers. When assembling the rest of the team, include a representative from each major stakeholder group, but keep the team small enough to be effective. For example, if your project focuses on improving telemetry utilization, seek representation from hospitalists, cardiologists, nurses, utilization managers, and possibly IT. Look for people with the relevant knowledge and experience who are respected by their peers and can influence opinion.

3. Design a sustainable solution.

To be sustainable, a solution must be evidence based, well integrated in provider workflow, and have acceptable impact on daily workload (e.g., additional time per patient). If an estimated impact is significant, you need to discuss adding resources or negotiating trade-offs.

A great example of a sustainable solution, aimed to control overutilization of telemetry and urinary catheters, is the one implemented by Dr. Wray and his team.7 They designed an EHR-based “silent” indicator that clearly signaled an active telemetry or urinary catheter order for each patient. Clicking on the indicator directed a provider to a “manage order” screen where she could cancel the order, if necessary.

4. Engage providers.

You may design the best solution, but it will not succeed unless it is embraced by others. To engage providers, you must clearly communicate why the change is urgently needed for the benefit of their patients, hospital, or community, and appeal to their minds, hearts, and competitive nature.

For example, if you are focusing on overutilization of urinary catheters, you may share your hospital’s urinary catheter device utilization ratio (# of indwelling catheter days/# patient days) against national benchmarks, or the impact on hospital catheter–associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) rates to appeal to the physicians’ minds. Often, data alone are not enough to move people to action. You must appeal to their hearts by sharing stories of real patients whose lives were affected by preventable CAUTI. Leverage physicians’ competitive nature by using provider-specific data to compare against their peers to spark a discussion.

5. Evaluate impact.

Even before you implement a solution, select metrics to measure impact and set SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) goals. As your implementation moves forward, do not let up or give up – continue to evaluate impact, remove barriers, refine your solution to get back on track if needed, and constantly communicate to share ongoing project results and lessons learned.

6. Sustain improvements.

Sustainable improvements require well-designed solutions integrated into provider workflow, but that is just the first step. Once you demonstrate the impact, consider including the metric (e.g., telemetry or urinary catheter utilization) in your team and/or individual provider performance dashboard, regularly reviewing and discussing performance during your team meetings to maintain engagement, and if needed, making improvements to get back on track.

Successful adoption of high-value care practices requires a disciplined approach to design and implement solutions that are patient-centric, evidence-based, data-driven and integrated in provider workflow.

Dr. Farah is a hospitalist, Physician Advisor, and Lean Six Sigma Black Belt. She is a performance improvement consultant based in Corvallis, Ore., and a member of The Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

References

1. From the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: National Health Expenditure Projections 2018-2027.

2. Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker: How does health spending in the U.S. compare to other countries?

3. Creating a new culture of care, in “Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America.” (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013, pp. 255-80).

4. Choosing Wisely: SHM – Adult Hospital Medicine; Five things physicians and patients should question.

5. Qaseem A et al. Appropriate use of screening and diagnostic tests to foster high-value, cost-conscious care. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jan 17;156(2):147-9.

6. Cho HJ et al. Right care in hospital medicine: Co-creation of ten opportunities in overuse and underuse for improving value in hospital medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Jun;33(6):804-6.

7. Wray CM et al. Improving value by reducing unnecessary telemetry and urinary catheter utilization in hospitalized patients. Am J Med. 2017 Sep;130(9):1037-41.

Six steps that can help your team

Six steps that can help your team

U.S. spending on health care is growing rapidly and expected to reach 19.7% of gross domestic product by 2026.1 In response, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and national organizations such as the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) and the American College of Physicians (ACP) have launched initiatives to ensure that the value being delivered to patients is on par with the escalating cost of care.

Over the past 10 years, I have led and advised hundreds of small- and large-scale projects that focused on improving patient care quality and cost. Below, I share what I, along with other leaders in high-value care, have observed that it takes to implement successful and lasting improvements – for the benefit of patients and hospitals.

A brief history of high-value care

When compared to other wealthy countries, the United States spends disproportionately more money on health care. In 2016, U.S. health care spending was $3.3 trillion1, or $10,348 per person.2 Hospital care alone was responsible for a third of health spending and amounted to $1.1 trillion in 20161. By 2026, national health spending is projected to reach $5.7 trillion1.

In response to escalating health care costs, CMS and other payers have shifted toward value-based reimbursements that tie payments to health care facilities and clinicians to their performance on selected quality, cost, and efficiency measures. For example, under the CMS Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), 5% of clinicians’ revenue in 2020 is tied to their 2018 performance in four categories: Quality, Cost, Improvement Activities, and Promoting Interoperability. The percentage of revenue at risk will increase to 9% in 2022, based on 2020 performance.

Rising health care costs put a burden not just on the federal and state budgets, but on individual and family budgets as well. Out-of-pocket spending grew 3.9% in 2016 to $352.5 billion1 and is expected to increase in the future. High health care costs rightfully bring into question the value individual consumers of health care services are getting in return. If value is defined as the level of benefit achieved for a given cost, what is high-value care? The 2013 Institute of Medicine report3 defined high-value care as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.” It goes beyond a set of quality and cost measures used by payers to affect provider reimbursement and is driven by day-to-day individual providers’ decisions that affect individual patients’ outcomes and their cost of care.

High-value care has been embraced by national organizations. In 2012, the ABIM Foundation launched the Choosing Wisely initiative to support and promote conversations between clinicians and patients in choosing care that is truly necessary, supported by evidence, and free from harm. The result was an evidence-based list of recommendations from 540 specialty societies, including the Society of Hospital Medicine. The SHM – Adult Hospital Medicine list4 features the following “Five things physicians and patients should question”:

- Don’t place, or leave in place, urinary catheters for incontinence or convenience or monitoring of output for non–critically ill patients.

- Don’t prescribe medications for stress ulcer prophylaxis to medical inpatients unless at high risk for GI complications.

- Avoid transfusions of red blood cells for arbitrary hemoglobin or hematocrit thresholds and in the absence of symptoms of active coronary disease, heart failure, or stroke.

- Don’t order continuous telemetry monitoring outside of the ICU without using a protocol that governs continuation.

- Don’t perform repetitive CBC and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.

The ACP launched a high-value care initiative that offers learning resources for clinicians and medical educators, clinical guidelines, and best practice advice. In 2012, a workgroup of internists convened by ACP developed a list of 37 clinical situations in which medical tests are commonly used but do not provide high value.5 Seven of those situations are applicable to adult hospital medicine.

High-value care today: What the experts say

More than 5 years later, what progress have hospitalists made in adopting high-value care practices? To answer this and other questions, I reached out to three national experts in high-value care in hospital medicine: Amit Pahwa, MD, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and a course director of “Topics in interdisciplinary medicine: High-value health care”; Christopher Petrilli, MD, clinical assistant professor in the department of medicine at New York University Langone Health and clinical lead, Manhattan campus, value-based management; and Charlie Wray, DO, MS, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California in San Francisco and a coauthor of an article on high-value care in hospital medicine published recently in the Journal of General Internal Medicine6.

The experts agree that awareness of high-value care among practicing physicians and medical trainees has increased in the last few years. Major professional publications have highlighted the topic, including The Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do For No Reason” series, JAMA’s “Teachable Moments,” and the American Journal of Medicine’s recurring column dedicated to high-value care practice. Leading teaching institutions have built high-value care curricula as a part of their medical student and resident training. However, widespread adoption has been slow and sometimes difficult.

The barriers to adoption of high-value practices among hospitalists are numerous and deep rooted in historical practices and culture. As Dr. Petrilli said, the “culture of overordering [diagnostic tests] is hard to break.” Hospitalists may not have well-developed relationships with patients, or time to explain why some tests or treatments are unnecessary. There is a lack of cost transparency, including the cost of the tests themselves and the downstream costs of additional tests and follow-ups. The best intended interventions fail to produce durable change unless they are seamlessly integrated into a hospitalist’s daily workflow.

Six steps to implementing a successful high-value care initiative

What can hospitalists do to improve the value of care they provide to their patients and hospital partners?

1. Identify high-value care opportunities at your hospital.

Dr. Wray pointed out that “all high-value care is local.” Start by looking at the national guidelines and talking to your senior clinical leaders and colleagues. Review your hospital data to identify opportunities and understand the root causes, including variability among providers.

If you choose to analyze and present provider-specific data, first be transparent on why you are doing that. Your goal is not to tell physicians how to practice or to score them, but instead, to promote adoption of evidence-based high-value care by identifying and discussing provider practice variations, and to generate possible solutions. Second, make sure that the data you present is credible and trustworthy by clearly outlining the data source, time frame, sample size per provider, any inclusion and exclusion criteria, attribution logic, and severity adjustment methodology. Third, expect initial pushback as transparency and change can be scary. But most doctors are inherently competitive and will want to be the best at caring for their patients.

2. Assemble the team.

Identify an executive sponsor – a senior clinical executive (for example, the chief medical officer or vice president of medical affairs) whose role is to help engage stakeholders, secure resources, and remove barriers. When assembling the rest of the team, include a representative from each major stakeholder group, but keep the team small enough to be effective. For example, if your project focuses on improving telemetry utilization, seek representation from hospitalists, cardiologists, nurses, utilization managers, and possibly IT. Look for people with the relevant knowledge and experience who are respected by their peers and can influence opinion.

3. Design a sustainable solution.

To be sustainable, a solution must be evidence based, well integrated in provider workflow, and have acceptable impact on daily workload (e.g., additional time per patient). If an estimated impact is significant, you need to discuss adding resources or negotiating trade-offs.

A great example of a sustainable solution, aimed to control overutilization of telemetry and urinary catheters, is the one implemented by Dr. Wray and his team.7 They designed an EHR-based “silent” indicator that clearly signaled an active telemetry or urinary catheter order for each patient. Clicking on the indicator directed a provider to a “manage order” screen where she could cancel the order, if necessary.

4. Engage providers.

You may design the best solution, but it will not succeed unless it is embraced by others. To engage providers, you must clearly communicate why the change is urgently needed for the benefit of their patients, hospital, or community, and appeal to their minds, hearts, and competitive nature.

For example, if you are focusing on overutilization of urinary catheters, you may share your hospital’s urinary catheter device utilization ratio (# of indwelling catheter days/# patient days) against national benchmarks, or the impact on hospital catheter–associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) rates to appeal to the physicians’ minds. Often, data alone are not enough to move people to action. You must appeal to their hearts by sharing stories of real patients whose lives were affected by preventable CAUTI. Leverage physicians’ competitive nature by using provider-specific data to compare against their peers to spark a discussion.

5. Evaluate impact.

Even before you implement a solution, select metrics to measure impact and set SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) goals. As your implementation moves forward, do not let up or give up – continue to evaluate impact, remove barriers, refine your solution to get back on track if needed, and constantly communicate to share ongoing project results and lessons learned.

6. Sustain improvements.

Sustainable improvements require well-designed solutions integrated into provider workflow, but that is just the first step. Once you demonstrate the impact, consider including the metric (e.g., telemetry or urinary catheter utilization) in your team and/or individual provider performance dashboard, regularly reviewing and discussing performance during your team meetings to maintain engagement, and if needed, making improvements to get back on track.

Successful adoption of high-value care practices requires a disciplined approach to design and implement solutions that are patient-centric, evidence-based, data-driven and integrated in provider workflow.

Dr. Farah is a hospitalist, Physician Advisor, and Lean Six Sigma Black Belt. She is a performance improvement consultant based in Corvallis, Ore., and a member of The Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

References

1. From the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: National Health Expenditure Projections 2018-2027.

2. Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker: How does health spending in the U.S. compare to other countries?

3. Creating a new culture of care, in “Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America.” (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013, pp. 255-80).

4. Choosing Wisely: SHM – Adult Hospital Medicine; Five things physicians and patients should question.

5. Qaseem A et al. Appropriate use of screening and diagnostic tests to foster high-value, cost-conscious care. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jan 17;156(2):147-9.

6. Cho HJ et al. Right care in hospital medicine: Co-creation of ten opportunities in overuse and underuse for improving value in hospital medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Jun;33(6):804-6.

7. Wray CM et al. Improving value by reducing unnecessary telemetry and urinary catheter utilization in hospitalized patients. Am J Med. 2017 Sep;130(9):1037-41.

U.S. spending on health care is growing rapidly and expected to reach 19.7% of gross domestic product by 2026.1 In response, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and national organizations such as the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) and the American College of Physicians (ACP) have launched initiatives to ensure that the value being delivered to patients is on par with the escalating cost of care.

Over the past 10 years, I have led and advised hundreds of small- and large-scale projects that focused on improving patient care quality and cost. Below, I share what I, along with other leaders in high-value care, have observed that it takes to implement successful and lasting improvements – for the benefit of patients and hospitals.

A brief history of high-value care

When compared to other wealthy countries, the United States spends disproportionately more money on health care. In 2016, U.S. health care spending was $3.3 trillion1, or $10,348 per person.2 Hospital care alone was responsible for a third of health spending and amounted to $1.1 trillion in 20161. By 2026, national health spending is projected to reach $5.7 trillion1.

In response to escalating health care costs, CMS and other payers have shifted toward value-based reimbursements that tie payments to health care facilities and clinicians to their performance on selected quality, cost, and efficiency measures. For example, under the CMS Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), 5% of clinicians’ revenue in 2020 is tied to their 2018 performance in four categories: Quality, Cost, Improvement Activities, and Promoting Interoperability. The percentage of revenue at risk will increase to 9% in 2022, based on 2020 performance.

Rising health care costs put a burden not just on the federal and state budgets, but on individual and family budgets as well. Out-of-pocket spending grew 3.9% in 2016 to $352.5 billion1 and is expected to increase in the future. High health care costs rightfully bring into question the value individual consumers of health care services are getting in return. If value is defined as the level of benefit achieved for a given cost, what is high-value care? The 2013 Institute of Medicine report3 defined high-value care as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.” It goes beyond a set of quality and cost measures used by payers to affect provider reimbursement and is driven by day-to-day individual providers’ decisions that affect individual patients’ outcomes and their cost of care.

High-value care has been embraced by national organizations. In 2012, the ABIM Foundation launched the Choosing Wisely initiative to support and promote conversations between clinicians and patients in choosing care that is truly necessary, supported by evidence, and free from harm. The result was an evidence-based list of recommendations from 540 specialty societies, including the Society of Hospital Medicine. The SHM – Adult Hospital Medicine list4 features the following “Five things physicians and patients should question”:

- Don’t place, or leave in place, urinary catheters for incontinence or convenience or monitoring of output for non–critically ill patients.

- Don’t prescribe medications for stress ulcer prophylaxis to medical inpatients unless at high risk for GI complications.

- Avoid transfusions of red blood cells for arbitrary hemoglobin or hematocrit thresholds and in the absence of symptoms of active coronary disease, heart failure, or stroke.

- Don’t order continuous telemetry monitoring outside of the ICU without using a protocol that governs continuation.

- Don’t perform repetitive CBC and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.

The ACP launched a high-value care initiative that offers learning resources for clinicians and medical educators, clinical guidelines, and best practice advice. In 2012, a workgroup of internists convened by ACP developed a list of 37 clinical situations in which medical tests are commonly used but do not provide high value.5 Seven of those situations are applicable to adult hospital medicine.

High-value care today: What the experts say

More than 5 years later, what progress have hospitalists made in adopting high-value care practices? To answer this and other questions, I reached out to three national experts in high-value care in hospital medicine: Amit Pahwa, MD, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and a course director of “Topics in interdisciplinary medicine: High-value health care”; Christopher Petrilli, MD, clinical assistant professor in the department of medicine at New York University Langone Health and clinical lead, Manhattan campus, value-based management; and Charlie Wray, DO, MS, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California in San Francisco and a coauthor of an article on high-value care in hospital medicine published recently in the Journal of General Internal Medicine6.

The experts agree that awareness of high-value care among practicing physicians and medical trainees has increased in the last few years. Major professional publications have highlighted the topic, including The Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do For No Reason” series, JAMA’s “Teachable Moments,” and the American Journal of Medicine’s recurring column dedicated to high-value care practice. Leading teaching institutions have built high-value care curricula as a part of their medical student and resident training. However, widespread adoption has been slow and sometimes difficult.

The barriers to adoption of high-value practices among hospitalists are numerous and deep rooted in historical practices and culture. As Dr. Petrilli said, the “culture of overordering [diagnostic tests] is hard to break.” Hospitalists may not have well-developed relationships with patients, or time to explain why some tests or treatments are unnecessary. There is a lack of cost transparency, including the cost of the tests themselves and the downstream costs of additional tests and follow-ups. The best intended interventions fail to produce durable change unless they are seamlessly integrated into a hospitalist’s daily workflow.

Six steps to implementing a successful high-value care initiative

What can hospitalists do to improve the value of care they provide to their patients and hospital partners?

1. Identify high-value care opportunities at your hospital.

Dr. Wray pointed out that “all high-value care is local.” Start by looking at the national guidelines and talking to your senior clinical leaders and colleagues. Review your hospital data to identify opportunities and understand the root causes, including variability among providers.

If you choose to analyze and present provider-specific data, first be transparent on why you are doing that. Your goal is not to tell physicians how to practice or to score them, but instead, to promote adoption of evidence-based high-value care by identifying and discussing provider practice variations, and to generate possible solutions. Second, make sure that the data you present is credible and trustworthy by clearly outlining the data source, time frame, sample size per provider, any inclusion and exclusion criteria, attribution logic, and severity adjustment methodology. Third, expect initial pushback as transparency and change can be scary. But most doctors are inherently competitive and will want to be the best at caring for their patients.

2. Assemble the team.

Identify an executive sponsor – a senior clinical executive (for example, the chief medical officer or vice president of medical affairs) whose role is to help engage stakeholders, secure resources, and remove barriers. When assembling the rest of the team, include a representative from each major stakeholder group, but keep the team small enough to be effective. For example, if your project focuses on improving telemetry utilization, seek representation from hospitalists, cardiologists, nurses, utilization managers, and possibly IT. Look for people with the relevant knowledge and experience who are respected by their peers and can influence opinion.

3. Design a sustainable solution.

To be sustainable, a solution must be evidence based, well integrated in provider workflow, and have acceptable impact on daily workload (e.g., additional time per patient). If an estimated impact is significant, you need to discuss adding resources or negotiating trade-offs.

A great example of a sustainable solution, aimed to control overutilization of telemetry and urinary catheters, is the one implemented by Dr. Wray and his team.7 They designed an EHR-based “silent” indicator that clearly signaled an active telemetry or urinary catheter order for each patient. Clicking on the indicator directed a provider to a “manage order” screen where she could cancel the order, if necessary.

4. Engage providers.

You may design the best solution, but it will not succeed unless it is embraced by others. To engage providers, you must clearly communicate why the change is urgently needed for the benefit of their patients, hospital, or community, and appeal to their minds, hearts, and competitive nature.

For example, if you are focusing on overutilization of urinary catheters, you may share your hospital’s urinary catheter device utilization ratio (# of indwelling catheter days/# patient days) against national benchmarks, or the impact on hospital catheter–associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) rates to appeal to the physicians’ minds. Often, data alone are not enough to move people to action. You must appeal to their hearts by sharing stories of real patients whose lives were affected by preventable CAUTI. Leverage physicians’ competitive nature by using provider-specific data to compare against their peers to spark a discussion.

5. Evaluate impact.

Even before you implement a solution, select metrics to measure impact and set SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) goals. As your implementation moves forward, do not let up or give up – continue to evaluate impact, remove barriers, refine your solution to get back on track if needed, and constantly communicate to share ongoing project results and lessons learned.

6. Sustain improvements.

Sustainable improvements require well-designed solutions integrated into provider workflow, but that is just the first step. Once you demonstrate the impact, consider including the metric (e.g., telemetry or urinary catheter utilization) in your team and/or individual provider performance dashboard, regularly reviewing and discussing performance during your team meetings to maintain engagement, and if needed, making improvements to get back on track.

Successful adoption of high-value care practices requires a disciplined approach to design and implement solutions that are patient-centric, evidence-based, data-driven and integrated in provider workflow.

Dr. Farah is a hospitalist, Physician Advisor, and Lean Six Sigma Black Belt. She is a performance improvement consultant based in Corvallis, Ore., and a member of The Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

References

1. From the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: National Health Expenditure Projections 2018-2027.

2. Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker: How does health spending in the U.S. compare to other countries?

3. Creating a new culture of care, in “Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America.” (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013, pp. 255-80).

4. Choosing Wisely: SHM – Adult Hospital Medicine; Five things physicians and patients should question.

5. Qaseem A et al. Appropriate use of screening and diagnostic tests to foster high-value, cost-conscious care. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jan 17;156(2):147-9.

6. Cho HJ et al. Right care in hospital medicine: Co-creation of ten opportunities in overuse and underuse for improving value in hospital medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Jun;33(6):804-6.

7. Wray CM et al. Improving value by reducing unnecessary telemetry and urinary catheter utilization in hospitalized patients. Am J Med. 2017 Sep;130(9):1037-41.

Hospitalist Career Goals Should Flow from Passion and Purpose

By Surinder Yadav, MD

For many new or job-changing hospitalists, finding your next position may be your main focus. It’s easy to imagine that once you land a job, the rest of your career will fall easily into place.

But hospital medicine is demanding stuff, and you can get so busy meeting the needs of others that you lose sight of your own. Eventually survival mode kicks in, and your drive and passion begin to fade.

In order to maintain a sense of forward momentum and job satisfaction, it helps to set annual goals. What could you accomplish this year that would really get you excited about your career? What skills could take your practice to the next level? Are your current actions in sync with your values and life purpose?

Here are some tips I've learned through the years:

Base goals on your passion

To get the most satisfaction from your career, start by identifying your passion. Why did you select medicine as a career, and how does it relate to your life purpose? Once you are clear on what motivates you to get up in the morning, you can set your goals to help drive and sustain that passion.

Set goals that are measurable

If you don’t have goals you can measure, it’s too easy to let them slide when you get busy with other obligations. Examples of some measurable goals I’ve set for my own career include taking leadership courses in project management and people management.

Once you’ve established your goals and determined how you will measure your progress and success, create a timeline for achieving each milestone. Also, consider finding an accountability partner who will check in with you now and then to make sure you're on track.

Be realistic

Goals that are admirable but not attainable are a waste of the paper they are written on. Make sure you have the resources you need to achieve your specific goals so that you have no roadblocks to success.

A final thought: One of the benefits of working for a physician partnership like Vituity is flexibility. You'll have more leeway to create a work schedule that allows you time for yourself. Work-life balance is great for your career longevity, and we believe it’s also good for your patients. When you feel rested and fulfilled, you have more energy and compassion to give to others.

Surinder Yadav, MD, is Vituity’s Vice President of Hospital Medicine Operations.

To learn more about satisfying medical careers at Vituity, please visit http://www.vituity.com/careers.

By Surinder Yadav, MD

For many new or job-changing hospitalists, finding your next position may be your main focus. It’s easy to imagine that once you land a job, the rest of your career will fall easily into place.

But hospital medicine is demanding stuff, and you can get so busy meeting the needs of others that you lose sight of your own. Eventually survival mode kicks in, and your drive and passion begin to fade.

In order to maintain a sense of forward momentum and job satisfaction, it helps to set annual goals. What could you accomplish this year that would really get you excited about your career? What skills could take your practice to the next level? Are your current actions in sync with your values and life purpose?

Here are some tips I've learned through the years:

Base goals on your passion

To get the most satisfaction from your career, start by identifying your passion. Why did you select medicine as a career, and how does it relate to your life purpose? Once you are clear on what motivates you to get up in the morning, you can set your goals to help drive and sustain that passion.

Set goals that are measurable

If you don’t have goals you can measure, it’s too easy to let them slide when you get busy with other obligations. Examples of some measurable goals I’ve set for my own career include taking leadership courses in project management and people management.

Once you’ve established your goals and determined how you will measure your progress and success, create a timeline for achieving each milestone. Also, consider finding an accountability partner who will check in with you now and then to make sure you're on track.

Be realistic

Goals that are admirable but not attainable are a waste of the paper they are written on. Make sure you have the resources you need to achieve your specific goals so that you have no roadblocks to success.

A final thought: One of the benefits of working for a physician partnership like Vituity is flexibility. You'll have more leeway to create a work schedule that allows you time for yourself. Work-life balance is great for your career longevity, and we believe it’s also good for your patients. When you feel rested and fulfilled, you have more energy and compassion to give to others.

Surinder Yadav, MD, is Vituity’s Vice President of Hospital Medicine Operations.

To learn more about satisfying medical careers at Vituity, please visit http://www.vituity.com/careers.

By Surinder Yadav, MD

For many new or job-changing hospitalists, finding your next position may be your main focus. It’s easy to imagine that once you land a job, the rest of your career will fall easily into place.

But hospital medicine is demanding stuff, and you can get so busy meeting the needs of others that you lose sight of your own. Eventually survival mode kicks in, and your drive and passion begin to fade.

In order to maintain a sense of forward momentum and job satisfaction, it helps to set annual goals. What could you accomplish this year that would really get you excited about your career? What skills could take your practice to the next level? Are your current actions in sync with your values and life purpose?

Here are some tips I've learned through the years:

Base goals on your passion

To get the most satisfaction from your career, start by identifying your passion. Why did you select medicine as a career, and how does it relate to your life purpose? Once you are clear on what motivates you to get up in the morning, you can set your goals to help drive and sustain that passion.

Set goals that are measurable

If you don’t have goals you can measure, it’s too easy to let them slide when you get busy with other obligations. Examples of some measurable goals I’ve set for my own career include taking leadership courses in project management and people management.

Once you’ve established your goals and determined how you will measure your progress and success, create a timeline for achieving each milestone. Also, consider finding an accountability partner who will check in with you now and then to make sure you're on track.

Be realistic

Goals that are admirable but not attainable are a waste of the paper they are written on. Make sure you have the resources you need to achieve your specific goals so that you have no roadblocks to success.

A final thought: One of the benefits of working for a physician partnership like Vituity is flexibility. You'll have more leeway to create a work schedule that allows you time for yourself. Work-life balance is great for your career longevity, and we believe it’s also good for your patients. When you feel rested and fulfilled, you have more energy and compassion to give to others.

Surinder Yadav, MD, is Vituity’s Vice President of Hospital Medicine Operations.

To learn more about satisfying medical careers at Vituity, please visit http://www.vituity.com/careers.

ONC’s Dr. Rucker: Era of provider-controlled data is over

“The era of the provider controlling all of this, I think this is over,” Donald Rucker, MD, head of the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) for Health Information Technology within the Department of Health and Human Services, said at an annual conference on health data and innovation. We need a “formal path to put patients back in control of their medical data.”

That path can be found in a pair of proposed rules issued earlier this year, one from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the other from ONC, that are designed to give patients that control.

With smartphone apps under development that will allow patient access to health care data from a single point of entry, “technology now allows us to move from having to go portal to portal to portal to really having us in control,” Dr. Rucker said. “I think it is going to transform [health care] in the same way that the smartphone app has transformed other sectors. We are very excited about that.”

Access to data and information should further the transition to value-based care as patients become the center of the decision tree, Dr. Rucker said, making decisions based on benefits in a way that is not possible now.

“In particular, we think patients are going to start being able to shop for care,” he said, adding that if “they don’t like the price of the care they are getting, they are going to be able to move their business elsewhere.”

To that end, he said that much of the talk about interoperability “is really a conversation about affordability and the vast expenses in health care and how you get some control over that.”

“The era of the provider controlling all of this, I think this is over,” Donald Rucker, MD, head of the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) for Health Information Technology within the Department of Health and Human Services, said at an annual conference on health data and innovation. We need a “formal path to put patients back in control of their medical data.”

That path can be found in a pair of proposed rules issued earlier this year, one from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the other from ONC, that are designed to give patients that control.

With smartphone apps under development that will allow patient access to health care data from a single point of entry, “technology now allows us to move from having to go portal to portal to portal to really having us in control,” Dr. Rucker said. “I think it is going to transform [health care] in the same way that the smartphone app has transformed other sectors. We are very excited about that.”

Access to data and information should further the transition to value-based care as patients become the center of the decision tree, Dr. Rucker said, making decisions based on benefits in a way that is not possible now.

“In particular, we think patients are going to start being able to shop for care,” he said, adding that if “they don’t like the price of the care they are getting, they are going to be able to move their business elsewhere.”

To that end, he said that much of the talk about interoperability “is really a conversation about affordability and the vast expenses in health care and how you get some control over that.”

“The era of the provider controlling all of this, I think this is over,” Donald Rucker, MD, head of the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) for Health Information Technology within the Department of Health and Human Services, said at an annual conference on health data and innovation. We need a “formal path to put patients back in control of their medical data.”

That path can be found in a pair of proposed rules issued earlier this year, one from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the other from ONC, that are designed to give patients that control.

With smartphone apps under development that will allow patient access to health care data from a single point of entry, “technology now allows us to move from having to go portal to portal to portal to really having us in control,” Dr. Rucker said. “I think it is going to transform [health care] in the same way that the smartphone app has transformed other sectors. We are very excited about that.”

Access to data and information should further the transition to value-based care as patients become the center of the decision tree, Dr. Rucker said, making decisions based on benefits in a way that is not possible now.

“In particular, we think patients are going to start being able to shop for care,” he said, adding that if “they don’t like the price of the care they are getting, they are going to be able to move their business elsewhere.”

To that end, he said that much of the talk about interoperability “is really a conversation about affordability and the vast expenses in health care and how you get some control over that.”

REPORTING FROM HEALTH DATAPALOOZA 2019

Malpractice: More lawsuits does not equal more relocations

David M. Studdert of Stanford (Calif.) University and his colleagues analyzed data from Medicare and the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) to assess associations between the number of paid malpractice claims that doctors accrued and exits from medical practice, changes in clinical volume, geographic relocation, and change in practice-group size. The study population included 480,894 physicians who had 68,956 paid claims from 2003 to 2015. Of the study group, 89% had no claims, 9% had one claim, and the remaining 2% had two or more claims that accounted for 40% of all claims. Nearly three-quarters of the doctors studied were men, and the majority of specialties were internal medicine (17%), general practice/family medicine (15%), emergency medicine (7%), radiology (6%), and anesthesiology (6%).

Physicians with a higher number of claims against them did not relocate at a greater rate than physicians who had fewer or no claims, the investigators wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

More claims against a doctor were associated with a higher likelihood of leaving medicine and more shifts into smaller practice settings. For instance, physicians with one claim had 9% higher odds of leaving the practice than doctors with no claims, and physicians with five or more claims had a 45% higher chance of leaving medicine than doctors with no claims, the researchers found.

In addition, investigators found that doctors with two to four claims had 50%-60% higher odds of entering solo practice than physicians with no claims, and physicians with five or more claims had nearly 150% higher odds of moving to solo practice than doctors who had never been sued. Physicians with three or more claims were more likely to be male, work in surgical specialties, and be at least age 50 years.

The study addresses concerns that physicians with troubling legal records were moving across state lines for a fresh start, Mr. Studdert said in an interview. “We were surprised to find that physicians who accumulated multiple malpractice claims were no more likely to relocate their practices than physicians without claims. The National Practitioner Data Bank probably has something to do with that.”

Established by Congress in 1986, the NPDB was started, in part, to restrict the ability of incompetent physicians to move across states to hide their track records. By requiring hospitals to query doctors records before granting them clinical privileges and encouraging physician groups, health plans, and professional societies to do the same, the NPDB has “almost certainly increased the difficulty of relocation for physicians with legal problems,” the authors noted in the study.

A primary takeaway from the analysis is that, while a single malpractice claim is a relatively weak signal that a quality problem exists, multiple paid claims over a relatively short period of time are a strong signal that a physician may have a quality deficiency, Mr. Studdert said in the interview.

“Regulators and malpractice insurers should be paying closer attention to this signal,” he added. “To the extent that physicians are aware of a colleague’s checkered malpractice history, they may have a role to play too. Vigilance about signs of further problems, for one, but also careful thought about the wisdom of referring patients to such physicians.”

Michelle M. Mello, JD, PhD, and Mr. Studdert both reported receiving grants from SUMIT Insurance during the conduct of the study.

Source: Studdert DM et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Mar 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1809981.

David M. Studdert of Stanford (Calif.) University and his colleagues analyzed data from Medicare and the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) to assess associations between the number of paid malpractice claims that doctors accrued and exits from medical practice, changes in clinical volume, geographic relocation, and change in practice-group size. The study population included 480,894 physicians who had 68,956 paid claims from 2003 to 2015. Of the study group, 89% had no claims, 9% had one claim, and the remaining 2% had two or more claims that accounted for 40% of all claims. Nearly three-quarters of the doctors studied were men, and the majority of specialties were internal medicine (17%), general practice/family medicine (15%), emergency medicine (7%), radiology (6%), and anesthesiology (6%).

Physicians with a higher number of claims against them did not relocate at a greater rate than physicians who had fewer or no claims, the investigators wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

More claims against a doctor were associated with a higher likelihood of leaving medicine and more shifts into smaller practice settings. For instance, physicians with one claim had 9% higher odds of leaving the practice than doctors with no claims, and physicians with five or more claims had a 45% higher chance of leaving medicine than doctors with no claims, the researchers found.

In addition, investigators found that doctors with two to four claims had 50%-60% higher odds of entering solo practice than physicians with no claims, and physicians with five or more claims had nearly 150% higher odds of moving to solo practice than doctors who had never been sued. Physicians with three or more claims were more likely to be male, work in surgical specialties, and be at least age 50 years.

The study addresses concerns that physicians with troubling legal records were moving across state lines for a fresh start, Mr. Studdert said in an interview. “We were surprised to find that physicians who accumulated multiple malpractice claims were no more likely to relocate their practices than physicians without claims. The National Practitioner Data Bank probably has something to do with that.”

Established by Congress in 1986, the NPDB was started, in part, to restrict the ability of incompetent physicians to move across states to hide their track records. By requiring hospitals to query doctors records before granting them clinical privileges and encouraging physician groups, health plans, and professional societies to do the same, the NPDB has “almost certainly increased the difficulty of relocation for physicians with legal problems,” the authors noted in the study.

A primary takeaway from the analysis is that, while a single malpractice claim is a relatively weak signal that a quality problem exists, multiple paid claims over a relatively short period of time are a strong signal that a physician may have a quality deficiency, Mr. Studdert said in the interview.

“Regulators and malpractice insurers should be paying closer attention to this signal,” he added. “To the extent that physicians are aware of a colleague’s checkered malpractice history, they may have a role to play too. Vigilance about signs of further problems, for one, but also careful thought about the wisdom of referring patients to such physicians.”

Michelle M. Mello, JD, PhD, and Mr. Studdert both reported receiving grants from SUMIT Insurance during the conduct of the study.

Source: Studdert DM et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Mar 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1809981.

David M. Studdert of Stanford (Calif.) University and his colleagues analyzed data from Medicare and the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) to assess associations between the number of paid malpractice claims that doctors accrued and exits from medical practice, changes in clinical volume, geographic relocation, and change in practice-group size. The study population included 480,894 physicians who had 68,956 paid claims from 2003 to 2015. Of the study group, 89% had no claims, 9% had one claim, and the remaining 2% had two or more claims that accounted for 40% of all claims. Nearly three-quarters of the doctors studied were men, and the majority of specialties were internal medicine (17%), general practice/family medicine (15%), emergency medicine (7%), radiology (6%), and anesthesiology (6%).

Physicians with a higher number of claims against them did not relocate at a greater rate than physicians who had fewer or no claims, the investigators wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

More claims against a doctor were associated with a higher likelihood of leaving medicine and more shifts into smaller practice settings. For instance, physicians with one claim had 9% higher odds of leaving the practice than doctors with no claims, and physicians with five or more claims had a 45% higher chance of leaving medicine than doctors with no claims, the researchers found.

In addition, investigators found that doctors with two to four claims had 50%-60% higher odds of entering solo practice than physicians with no claims, and physicians with five or more claims had nearly 150% higher odds of moving to solo practice than doctors who had never been sued. Physicians with three or more claims were more likely to be male, work in surgical specialties, and be at least age 50 years.

The study addresses concerns that physicians with troubling legal records were moving across state lines for a fresh start, Mr. Studdert said in an interview. “We were surprised to find that physicians who accumulated multiple malpractice claims were no more likely to relocate their practices than physicians without claims. The National Practitioner Data Bank probably has something to do with that.”

Established by Congress in 1986, the NPDB was started, in part, to restrict the ability of incompetent physicians to move across states to hide their track records. By requiring hospitals to query doctors records before granting them clinical privileges and encouraging physician groups, health plans, and professional societies to do the same, the NPDB has “almost certainly increased the difficulty of relocation for physicians with legal problems,” the authors noted in the study.

A primary takeaway from the analysis is that, while a single malpractice claim is a relatively weak signal that a quality problem exists, multiple paid claims over a relatively short period of time are a strong signal that a physician may have a quality deficiency, Mr. Studdert said in the interview.

“Regulators and malpractice insurers should be paying closer attention to this signal,” he added. “To the extent that physicians are aware of a colleague’s checkered malpractice history, they may have a role to play too. Vigilance about signs of further problems, for one, but also careful thought about the wisdom of referring patients to such physicians.”

Michelle M. Mello, JD, PhD, and Mr. Studdert both reported receiving grants from SUMIT Insurance during the conduct of the study.

Source: Studdert DM et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Mar 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1809981.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Gender wage gap varies by specialty

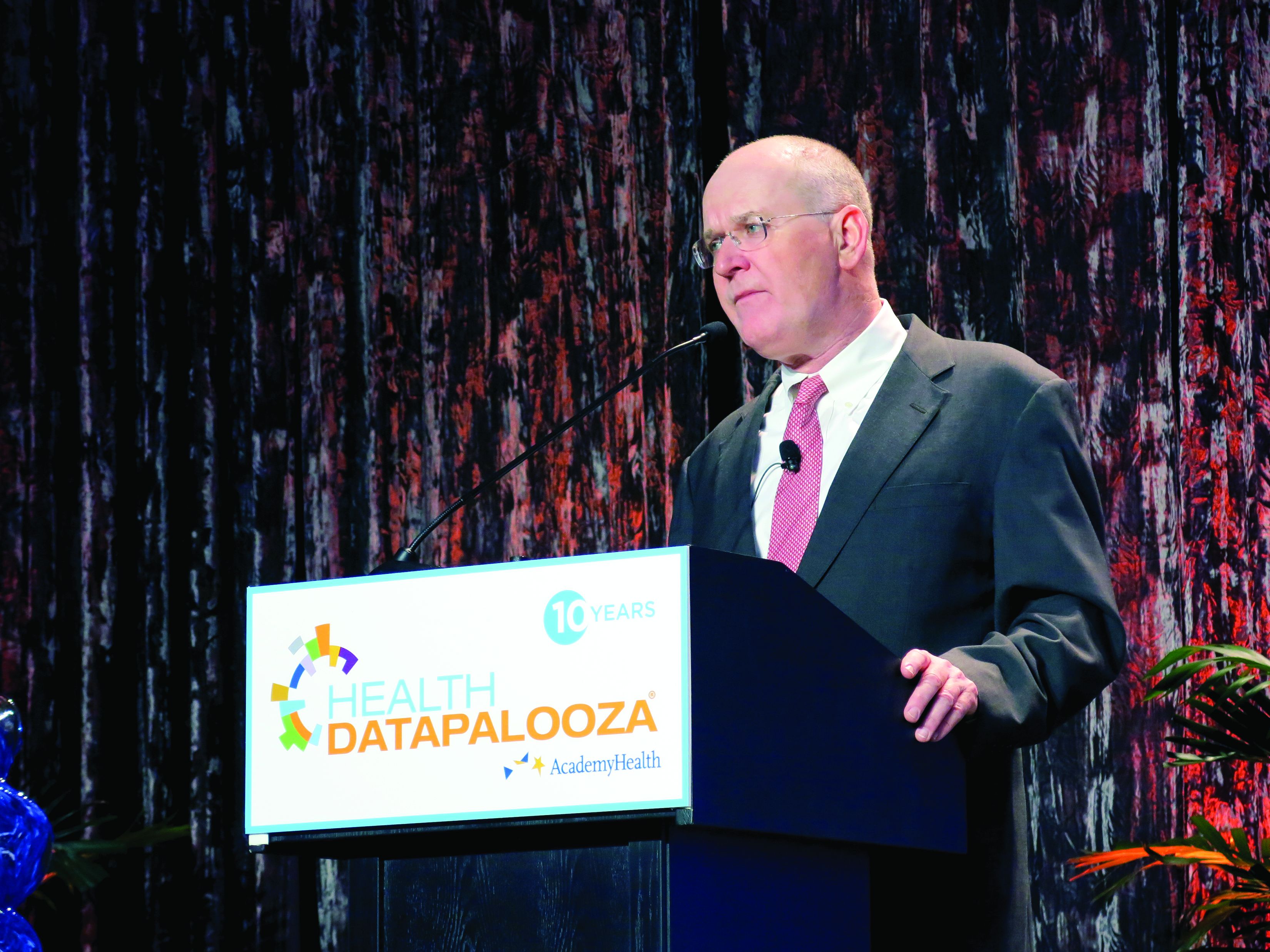

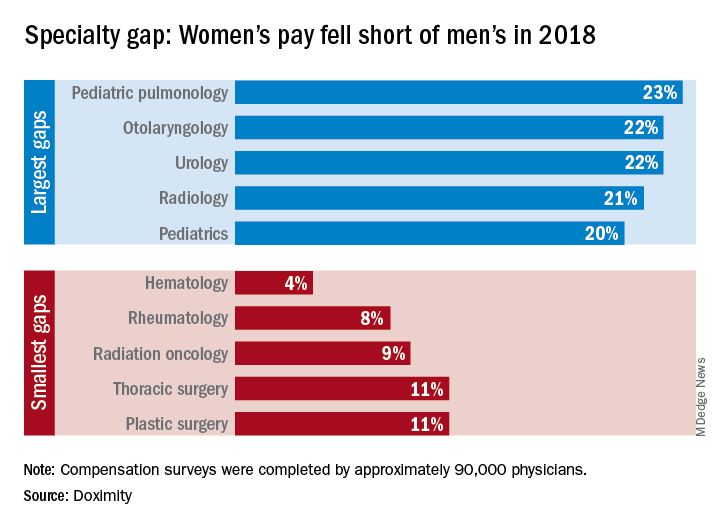

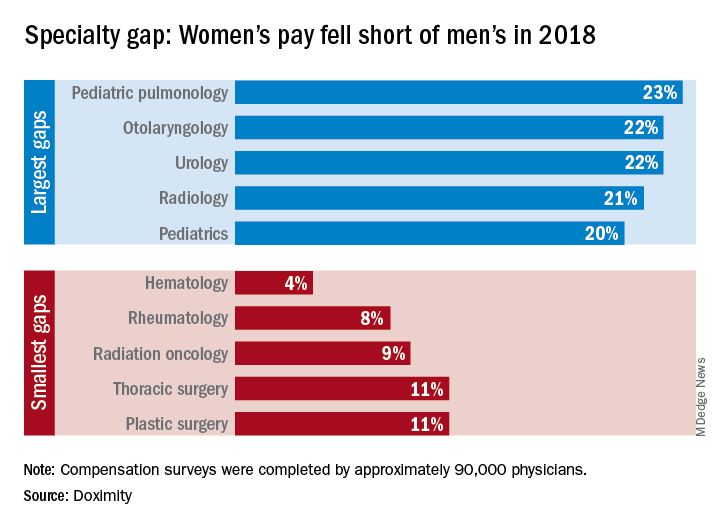

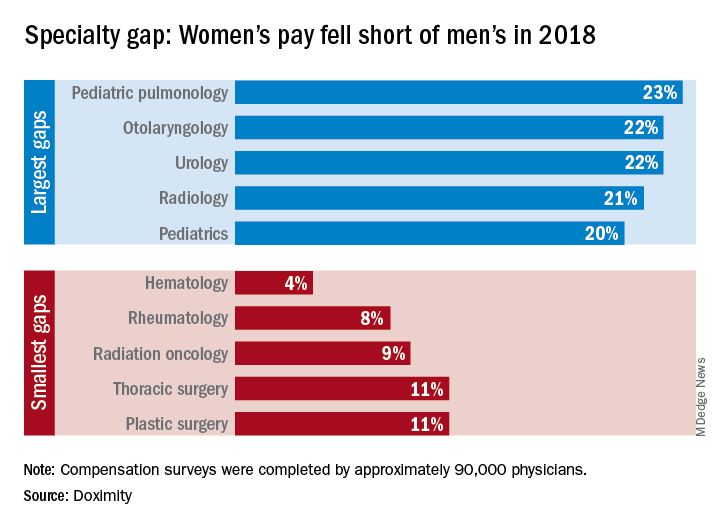

There is no specialty in which women physicians make as much as men, but hematology came the closest in 2018, according to a new survey by the medical social network Doximity.

Female hematologists averaged $309,000 in earnings in 2018, just 4% less than their male counterparts, who brought in an average of $323,000. Rheumatology had the next-smallest gap, 8%, between women and men, followed by radiation oncology at 9% and thoracic surgery and plastic surgery at 11% each, Doximity reported March 26. All of the 90,000 physicians involved in the survey worked at least 40 hours per week.

At the other end of the scale is pediatric pulmonology, home of the largest gender wage gap. Average compensation for women in the specialty was $195,000, or 23% less than the $253,000 that men received. Women in otolaryngology and urology were next, earning 22% less than men in those specialties, while women in radiology and pediatrics averaged 21% and 20% less, respectively, than men, Doximity said in its report.

The gender wage gap has been persistent, but the latest data show that it is starting to close as the earnings curve for male physicians flattened in 2018 while pay increased for female physicians.

“Compensation transparency is a powerful force. As more data becomes available to us, exposing the pay gap between men and women, we see more movements to rectify this issue,” said Christopher Whaley, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health, who was lead author of the study.

To account for differences in specialty, geography, and physician-specific factors, the Doximity researchers used “a multivariate regression with fixed effects for provider specialty and [metropolitan statistical area].” They also controlled for how long each physician has been in practice and their self-reported average hours worked.

There is no specialty in which women physicians make as much as men, but hematology came the closest in 2018, according to a new survey by the medical social network Doximity.

Female hematologists averaged $309,000 in earnings in 2018, just 4% less than their male counterparts, who brought in an average of $323,000. Rheumatology had the next-smallest gap, 8%, between women and men, followed by radiation oncology at 9% and thoracic surgery and plastic surgery at 11% each, Doximity reported March 26. All of the 90,000 physicians involved in the survey worked at least 40 hours per week.

At the other end of the scale is pediatric pulmonology, home of the largest gender wage gap. Average compensation for women in the specialty was $195,000, or 23% less than the $253,000 that men received. Women in otolaryngology and urology were next, earning 22% less than men in those specialties, while women in radiology and pediatrics averaged 21% and 20% less, respectively, than men, Doximity said in its report.

The gender wage gap has been persistent, but the latest data show that it is starting to close as the earnings curve for male physicians flattened in 2018 while pay increased for female physicians.

“Compensation transparency is a powerful force. As more data becomes available to us, exposing the pay gap between men and women, we see more movements to rectify this issue,” said Christopher Whaley, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health, who was lead author of the study.

To account for differences in specialty, geography, and physician-specific factors, the Doximity researchers used “a multivariate regression with fixed effects for provider specialty and [metropolitan statistical area].” They also controlled for how long each physician has been in practice and their self-reported average hours worked.

There is no specialty in which women physicians make as much as men, but hematology came the closest in 2018, according to a new survey by the medical social network Doximity.