User login

Vesicular rash in a newborn girl

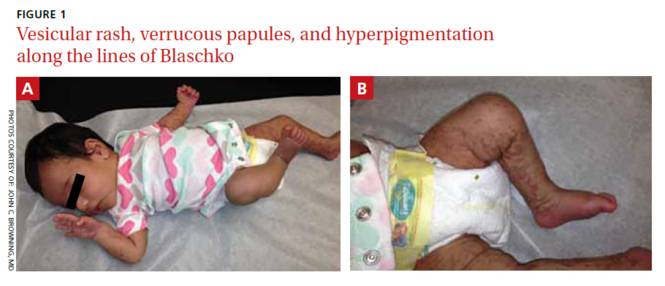

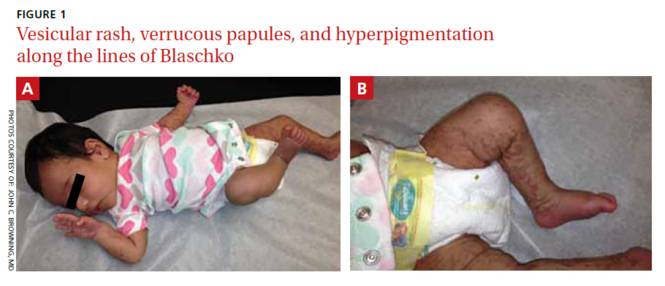

A 3-week-old girl was brought to our pediatric dermatology clinic by her mother for evaluation of a rash on her arms, legs, and trunk that she’d had since birth. The child was otherwise healthy and the mother said she hadn’t experienced any complications during pregnancy or the perinatal period.

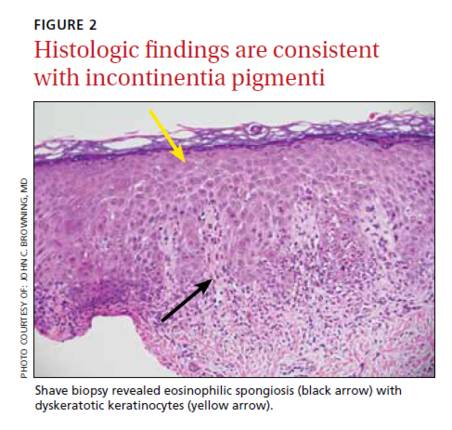

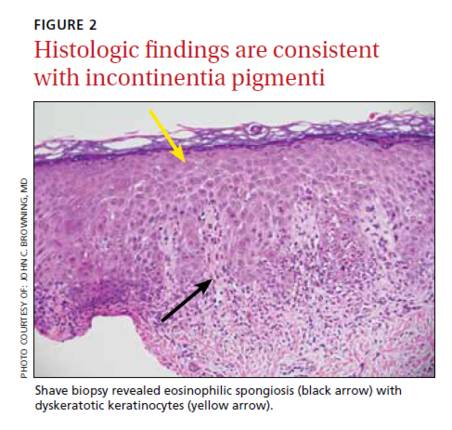

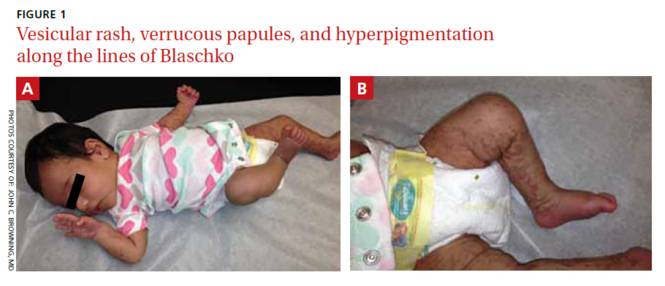

On physical exam, we noted erythematous papules, vesicles, and brown verrucous papules distributed on the newborn’s torso and extremities in a Blaschkoid patter (FIGURE 1). A shave biopsy revealed a mild to moderate hyperplastic epidermis with eosinophilic spongiosis and many scattered necrotic keratinocytes (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Incontinentia pigmenti

Based on the appearance and pattern of the rash and histologic findings, we diagnosed incontinentia pigmenti (IP) in this patient. IP is a rare genodermatosis characterized by abnormalities of the tissues and organs derived from the ectoderm and neuroectoderm. It is a type of ectodermal dysplasia that involves the skin, and sometimes other tissues.1

IP is transmitted in an X-linked dominant manner and occurs predominantly in females; it is often lethal in males. It is caused by a mutation of the IKBKG (inhibitor of kappa B kinase gamma) gene, which results in defective activation of nuclear factor-kappa beta (NF-κB), an essential regulator of inflammatory and apoptotic pathways.1 In females, lyonization results in functional mosaicism of X-linked genes, which is manifested by the Blaschkoid distribution of cutaneous lesions.2

In addition to the skin, IP can also affect the eyes, central nervous system (CNS), teeth, hair, and nails.1 Ocular symptoms are present in 35% to 77% of patients with IP.3 Such symptoms are often unilateral, persistent, and may be highly debilitating. The most serious and by far the most common ocular anomalies affect the retina, with possible development of vascular anomalies, pre-retinal fibrosis, retrolental mass, retinal detachment, and a change in the retinal pigment epithelium. Common non-retinal ocular complications of IP include cataracts and strabismus.

The skin lesions of IP progress through 4 stages

Cutaneous manifestations of IP follow the lines of Blaschko and occur in a chronological sequence of 4 stages, which may temporarily overlap.4

The first stage (the vesicular stage) is comprised of papules, vesicles, or pustules on an erythematous base. These skin lesions are present at birth or develop in the first few weeks of life in 90% of patients, and typically resolve around 4 months.5

The second stage (the verrucous stage) consists of wart-like papules and plaques. These most commonly develop between 2 to 6 weeks and resolve by 6 months.

The third stage (the hyperpigmented stage) is marked by linear or whorled brown pigmentation. These lesions typically develop during the first 3 to 6 months of life and slowly disappear in adolescence.6

The final stage (the hypopigmented/atrophic stage) develops in adolescence and may be permanent. It often affects the lower extremities with areas of hypopigmentation, atrophy, and an absence of hair.

The diagnosis of IP is made based on the presence of typical cutaneous findings of any stage, most commonly the characteristic vesicular rash and the classic Blaschkoid hyperpigmentation on the trunk that often fades in adolescence.7 Typical features on cutaneous histology, such as eosinophilic spongiosis and dyskeratotic keratinocytes, can support the diagnosis.

Abnormalities of the teeth, eyes, hair, nails, CNS (eg, seizures, mental retardation, or microcephaly), palate, and nipple and breast have also been seen during infancy and are permanent. The mother of a child with IP may have a history of multiple miscarriages of male fetuses.6

Distinguish the rash of IP from other blistering diseases

The differential diagnosis of IP includes other cutaneous blistering diseases, such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection and epidermolysis bullosa (EB).8 HSV infection is the most common misdiagnosis in a neonate with vesicles, especially when seizures are also present.6 EB is a rare group of inherited disorders that manifest as blistering of the skin in infants, most commonly affecting the fingers, hands, elbows, feet, legs, and diaper area.

The distribution of skin lesions along the lines of Blaschko, the progression of the rash through different stages, and the possible maternal history of spontaneous abortions can distinguish IP from both HSV infection and EB.6 Cutaneous histopathology is also helpful for differentiating vesicular lesions in infancy and can confirm the diagnosis of IP.

No specific treatment for IP rash; carefully evaluate other symptoms

Because the skin manifestations of IP usually resolve spontaneously, no specific treatment is required. The prognosis of a patient with IP depends on the presence and severity of extracutaneous manifestations of the condition.

A patient with IP who has abnormal findings on a neurologic examination, vascular retinopathy, or both should undergo routine neurodevelopmental assessment and neuroimaging.5 Treatment of neurologic complications is symptomatic. Speech therapy may play an important role in management of these patients because dental and neurologic abnormalities may result in dysfunction of chewing, swallowing, speech, language, and hearing.

Ophthalmology referral is also crucial because untreated retinal disorders have been reported to cause blindness in 7% to 23% of patients with IP.3 Screening is recommended at birth (or at diagnosis), and the child is followed regularly during the first year of life.5

Morbidity and mortality primarily result from neurologic manifestations (most commonly seizures and mental retardation) and ophthalmologic complications, which can result in vision loss.

Our patient presented with a rash in the vesicular stage of IP that was transitioning to the verrucous stage. She was seen by Ophthalmology at 4 weeks of age and there were no concerning findings at that time. She will continue to follow up with Ophthalmology, Dermatology, and her primary care physician.

CORRESPONDENCE

John C. Browning, MD, Chief of Dermatology, Children’s Hospital of San Antonio, 333 N. Santa Rosa, San Antonio, TX, 78207; [email protected]

1. Landy SJ, Donnai D. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome). J Med Genet. 1993;30:53-59.

2. Migeon BR, Axelman J, Jan de Beur S, et al. Selection against lethal alleles in females heterozygous for incontinentia pigmenti. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:100-106.

3. Minic S, Obradovic M, Kovacevic I, et al. Ocular anomalies in incontinentia pigmenti: literature review and meta-analysis. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2010;138:408-413.

4. Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:26-36.

5. Hadj-Rabia S, Froidevaux D, Bodak N, et al. Clinical study of 40 cases of incontinentia pigmenti. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1163-1170.

6. Faloyin M, Levitt J, Bercowitz E, et al. All that is vesicular is not herpes: incontinentia pigmenti masquerading as herpes simplex virus in a newborn. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e270-e272.

7. Minic S, Trpinac D, Obradovic M. Incontinentia pigmenti diagnostic criteria update. Clin Genet. 2014;85:536-542.

8. Cohen PR. Incontinentia pigmenti: clinicopathologic characteristics and differential diagnosis. Cutis. 1994;54:161-166.

A 3-week-old girl was brought to our pediatric dermatology clinic by her mother for evaluation of a rash on her arms, legs, and trunk that she’d had since birth. The child was otherwise healthy and the mother said she hadn’t experienced any complications during pregnancy or the perinatal period.

On physical exam, we noted erythematous papules, vesicles, and brown verrucous papules distributed on the newborn’s torso and extremities in a Blaschkoid patter (FIGURE 1). A shave biopsy revealed a mild to moderate hyperplastic epidermis with eosinophilic spongiosis and many scattered necrotic keratinocytes (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Incontinentia pigmenti

Based on the appearance and pattern of the rash and histologic findings, we diagnosed incontinentia pigmenti (IP) in this patient. IP is a rare genodermatosis characterized by abnormalities of the tissues and organs derived from the ectoderm and neuroectoderm. It is a type of ectodermal dysplasia that involves the skin, and sometimes other tissues.1

IP is transmitted in an X-linked dominant manner and occurs predominantly in females; it is often lethal in males. It is caused by a mutation of the IKBKG (inhibitor of kappa B kinase gamma) gene, which results in defective activation of nuclear factor-kappa beta (NF-κB), an essential regulator of inflammatory and apoptotic pathways.1 In females, lyonization results in functional mosaicism of X-linked genes, which is manifested by the Blaschkoid distribution of cutaneous lesions.2

In addition to the skin, IP can also affect the eyes, central nervous system (CNS), teeth, hair, and nails.1 Ocular symptoms are present in 35% to 77% of patients with IP.3 Such symptoms are often unilateral, persistent, and may be highly debilitating. The most serious and by far the most common ocular anomalies affect the retina, with possible development of vascular anomalies, pre-retinal fibrosis, retrolental mass, retinal detachment, and a change in the retinal pigment epithelium. Common non-retinal ocular complications of IP include cataracts and strabismus.

The skin lesions of IP progress through 4 stages

Cutaneous manifestations of IP follow the lines of Blaschko and occur in a chronological sequence of 4 stages, which may temporarily overlap.4

The first stage (the vesicular stage) is comprised of papules, vesicles, or pustules on an erythematous base. These skin lesions are present at birth or develop in the first few weeks of life in 90% of patients, and typically resolve around 4 months.5

The second stage (the verrucous stage) consists of wart-like papules and plaques. These most commonly develop between 2 to 6 weeks and resolve by 6 months.

The third stage (the hyperpigmented stage) is marked by linear or whorled brown pigmentation. These lesions typically develop during the first 3 to 6 months of life and slowly disappear in adolescence.6

The final stage (the hypopigmented/atrophic stage) develops in adolescence and may be permanent. It often affects the lower extremities with areas of hypopigmentation, atrophy, and an absence of hair.

The diagnosis of IP is made based on the presence of typical cutaneous findings of any stage, most commonly the characteristic vesicular rash and the classic Blaschkoid hyperpigmentation on the trunk that often fades in adolescence.7 Typical features on cutaneous histology, such as eosinophilic spongiosis and dyskeratotic keratinocytes, can support the diagnosis.

Abnormalities of the teeth, eyes, hair, nails, CNS (eg, seizures, mental retardation, or microcephaly), palate, and nipple and breast have also been seen during infancy and are permanent. The mother of a child with IP may have a history of multiple miscarriages of male fetuses.6

Distinguish the rash of IP from other blistering diseases

The differential diagnosis of IP includes other cutaneous blistering diseases, such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection and epidermolysis bullosa (EB).8 HSV infection is the most common misdiagnosis in a neonate with vesicles, especially when seizures are also present.6 EB is a rare group of inherited disorders that manifest as blistering of the skin in infants, most commonly affecting the fingers, hands, elbows, feet, legs, and diaper area.

The distribution of skin lesions along the lines of Blaschko, the progression of the rash through different stages, and the possible maternal history of spontaneous abortions can distinguish IP from both HSV infection and EB.6 Cutaneous histopathology is also helpful for differentiating vesicular lesions in infancy and can confirm the diagnosis of IP.

No specific treatment for IP rash; carefully evaluate other symptoms

Because the skin manifestations of IP usually resolve spontaneously, no specific treatment is required. The prognosis of a patient with IP depends on the presence and severity of extracutaneous manifestations of the condition.

A patient with IP who has abnormal findings on a neurologic examination, vascular retinopathy, or both should undergo routine neurodevelopmental assessment and neuroimaging.5 Treatment of neurologic complications is symptomatic. Speech therapy may play an important role in management of these patients because dental and neurologic abnormalities may result in dysfunction of chewing, swallowing, speech, language, and hearing.

Ophthalmology referral is also crucial because untreated retinal disorders have been reported to cause blindness in 7% to 23% of patients with IP.3 Screening is recommended at birth (or at diagnosis), and the child is followed regularly during the first year of life.5

Morbidity and mortality primarily result from neurologic manifestations (most commonly seizures and mental retardation) and ophthalmologic complications, which can result in vision loss.

Our patient presented with a rash in the vesicular stage of IP that was transitioning to the verrucous stage. She was seen by Ophthalmology at 4 weeks of age and there were no concerning findings at that time. She will continue to follow up with Ophthalmology, Dermatology, and her primary care physician.

CORRESPONDENCE

John C. Browning, MD, Chief of Dermatology, Children’s Hospital of San Antonio, 333 N. Santa Rosa, San Antonio, TX, 78207; [email protected]

A 3-week-old girl was brought to our pediatric dermatology clinic by her mother for evaluation of a rash on her arms, legs, and trunk that she’d had since birth. The child was otherwise healthy and the mother said she hadn’t experienced any complications during pregnancy or the perinatal period.

On physical exam, we noted erythematous papules, vesicles, and brown verrucous papules distributed on the newborn’s torso and extremities in a Blaschkoid patter (FIGURE 1). A shave biopsy revealed a mild to moderate hyperplastic epidermis with eosinophilic spongiosis and many scattered necrotic keratinocytes (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Incontinentia pigmenti

Based on the appearance and pattern of the rash and histologic findings, we diagnosed incontinentia pigmenti (IP) in this patient. IP is a rare genodermatosis characterized by abnormalities of the tissues and organs derived from the ectoderm and neuroectoderm. It is a type of ectodermal dysplasia that involves the skin, and sometimes other tissues.1

IP is transmitted in an X-linked dominant manner and occurs predominantly in females; it is often lethal in males. It is caused by a mutation of the IKBKG (inhibitor of kappa B kinase gamma) gene, which results in defective activation of nuclear factor-kappa beta (NF-κB), an essential regulator of inflammatory and apoptotic pathways.1 In females, lyonization results in functional mosaicism of X-linked genes, which is manifested by the Blaschkoid distribution of cutaneous lesions.2

In addition to the skin, IP can also affect the eyes, central nervous system (CNS), teeth, hair, and nails.1 Ocular symptoms are present in 35% to 77% of patients with IP.3 Such symptoms are often unilateral, persistent, and may be highly debilitating. The most serious and by far the most common ocular anomalies affect the retina, with possible development of vascular anomalies, pre-retinal fibrosis, retrolental mass, retinal detachment, and a change in the retinal pigment epithelium. Common non-retinal ocular complications of IP include cataracts and strabismus.

The skin lesions of IP progress through 4 stages

Cutaneous manifestations of IP follow the lines of Blaschko and occur in a chronological sequence of 4 stages, which may temporarily overlap.4

The first stage (the vesicular stage) is comprised of papules, vesicles, or pustules on an erythematous base. These skin lesions are present at birth or develop in the first few weeks of life in 90% of patients, and typically resolve around 4 months.5

The second stage (the verrucous stage) consists of wart-like papules and plaques. These most commonly develop between 2 to 6 weeks and resolve by 6 months.

The third stage (the hyperpigmented stage) is marked by linear or whorled brown pigmentation. These lesions typically develop during the first 3 to 6 months of life and slowly disappear in adolescence.6

The final stage (the hypopigmented/atrophic stage) develops in adolescence and may be permanent. It often affects the lower extremities with areas of hypopigmentation, atrophy, and an absence of hair.

The diagnosis of IP is made based on the presence of typical cutaneous findings of any stage, most commonly the characteristic vesicular rash and the classic Blaschkoid hyperpigmentation on the trunk that often fades in adolescence.7 Typical features on cutaneous histology, such as eosinophilic spongiosis and dyskeratotic keratinocytes, can support the diagnosis.

Abnormalities of the teeth, eyes, hair, nails, CNS (eg, seizures, mental retardation, or microcephaly), palate, and nipple and breast have also been seen during infancy and are permanent. The mother of a child with IP may have a history of multiple miscarriages of male fetuses.6

Distinguish the rash of IP from other blistering diseases

The differential diagnosis of IP includes other cutaneous blistering diseases, such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection and epidermolysis bullosa (EB).8 HSV infection is the most common misdiagnosis in a neonate with vesicles, especially when seizures are also present.6 EB is a rare group of inherited disorders that manifest as blistering of the skin in infants, most commonly affecting the fingers, hands, elbows, feet, legs, and diaper area.

The distribution of skin lesions along the lines of Blaschko, the progression of the rash through different stages, and the possible maternal history of spontaneous abortions can distinguish IP from both HSV infection and EB.6 Cutaneous histopathology is also helpful for differentiating vesicular lesions in infancy and can confirm the diagnosis of IP.

No specific treatment for IP rash; carefully evaluate other symptoms

Because the skin manifestations of IP usually resolve spontaneously, no specific treatment is required. The prognosis of a patient with IP depends on the presence and severity of extracutaneous manifestations of the condition.

A patient with IP who has abnormal findings on a neurologic examination, vascular retinopathy, or both should undergo routine neurodevelopmental assessment and neuroimaging.5 Treatment of neurologic complications is symptomatic. Speech therapy may play an important role in management of these patients because dental and neurologic abnormalities may result in dysfunction of chewing, swallowing, speech, language, and hearing.

Ophthalmology referral is also crucial because untreated retinal disorders have been reported to cause blindness in 7% to 23% of patients with IP.3 Screening is recommended at birth (or at diagnosis), and the child is followed regularly during the first year of life.5

Morbidity and mortality primarily result from neurologic manifestations (most commonly seizures and mental retardation) and ophthalmologic complications, which can result in vision loss.

Our patient presented with a rash in the vesicular stage of IP that was transitioning to the verrucous stage. She was seen by Ophthalmology at 4 weeks of age and there were no concerning findings at that time. She will continue to follow up with Ophthalmology, Dermatology, and her primary care physician.

CORRESPONDENCE

John C. Browning, MD, Chief of Dermatology, Children’s Hospital of San Antonio, 333 N. Santa Rosa, San Antonio, TX, 78207; [email protected]

1. Landy SJ, Donnai D. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome). J Med Genet. 1993;30:53-59.

2. Migeon BR, Axelman J, Jan de Beur S, et al. Selection against lethal alleles in females heterozygous for incontinentia pigmenti. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:100-106.

3. Minic S, Obradovic M, Kovacevic I, et al. Ocular anomalies in incontinentia pigmenti: literature review and meta-analysis. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2010;138:408-413.

4. Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:26-36.

5. Hadj-Rabia S, Froidevaux D, Bodak N, et al. Clinical study of 40 cases of incontinentia pigmenti. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1163-1170.

6. Faloyin M, Levitt J, Bercowitz E, et al. All that is vesicular is not herpes: incontinentia pigmenti masquerading as herpes simplex virus in a newborn. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e270-e272.

7. Minic S, Trpinac D, Obradovic M. Incontinentia pigmenti diagnostic criteria update. Clin Genet. 2014;85:536-542.

8. Cohen PR. Incontinentia pigmenti: clinicopathologic characteristics and differential diagnosis. Cutis. 1994;54:161-166.

1. Landy SJ, Donnai D. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome). J Med Genet. 1993;30:53-59.

2. Migeon BR, Axelman J, Jan de Beur S, et al. Selection against lethal alleles in females heterozygous for incontinentia pigmenti. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:100-106.

3. Minic S, Obradovic M, Kovacevic I, et al. Ocular anomalies in incontinentia pigmenti: literature review and meta-analysis. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2010;138:408-413.

4. Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:26-36.

5. Hadj-Rabia S, Froidevaux D, Bodak N, et al. Clinical study of 40 cases of incontinentia pigmenti. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1163-1170.

6. Faloyin M, Levitt J, Bercowitz E, et al. All that is vesicular is not herpes: incontinentia pigmenti masquerading as herpes simplex virus in a newborn. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e270-e272.

7. Minic S, Trpinac D, Obradovic M. Incontinentia pigmenti diagnostic criteria update. Clin Genet. 2014;85:536-542.

8. Cohen PR. Incontinentia pigmenti: clinicopathologic characteristics and differential diagnosis. Cutis. 1994;54:161-166.

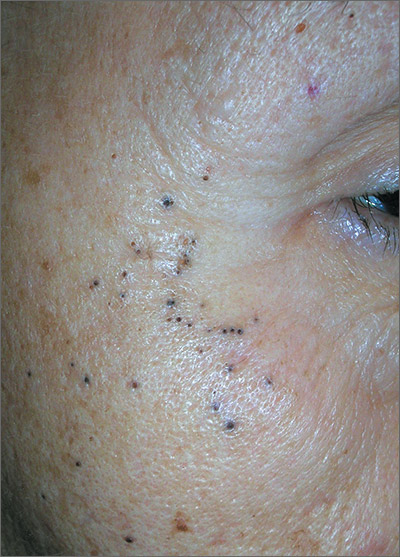

Diminished vision and face papules

The FP diagnosed papulopustular rosacea in this patient, along with ocular rosacea. The patient had advanced ocular rosacea with neovascularization on the cornea, which can lead to blindness.

Ocular rosacea is an advanced subtype of rosacea that is characterized by impressive, severe flushing with persistent telangiectasias, papules, and pustules. Patients may complain of watery eyes, a foreign-body sensation, burning, dryness, vision changes, and lid or periocular erythema. The eyelids are most commonly involved with telangiectasias, blepharitis, and recurrent hordeola and chalazia. Conjunctivitis may be chronic. Although corneal involvement is the least common, it can have the most devastating consequences. Corneal findings may include punctate erosions, corneal infiltrates, and corneal neovascularization. In the most severe cases, blood vessels may grow over the cornea and lead to blindness.

The FP in this case started the patient on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day and made an urgent referral to Ophthalmology. At a follow-up visit one month later, the FP noted that the patient had been started on ophthalmic cyclosporine for the ocular rosacea. The doxycycline had diminished the papules and pustules, and together with the ophthalmic cyclosporine, the patient’s eyes were feeling less symptomatic. The ophthalmologist also indicated that the patient might need corneal transplants in the future if medical treatment did not stop the severe corneal involvement.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Rosacea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:659-664.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed papulopustular rosacea in this patient, along with ocular rosacea. The patient had advanced ocular rosacea with neovascularization on the cornea, which can lead to blindness.

Ocular rosacea is an advanced subtype of rosacea that is characterized by impressive, severe flushing with persistent telangiectasias, papules, and pustules. Patients may complain of watery eyes, a foreign-body sensation, burning, dryness, vision changes, and lid or periocular erythema. The eyelids are most commonly involved with telangiectasias, blepharitis, and recurrent hordeola and chalazia. Conjunctivitis may be chronic. Although corneal involvement is the least common, it can have the most devastating consequences. Corneal findings may include punctate erosions, corneal infiltrates, and corneal neovascularization. In the most severe cases, blood vessels may grow over the cornea and lead to blindness.

The FP in this case started the patient on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day and made an urgent referral to Ophthalmology. At a follow-up visit one month later, the FP noted that the patient had been started on ophthalmic cyclosporine for the ocular rosacea. The doxycycline had diminished the papules and pustules, and together with the ophthalmic cyclosporine, the patient’s eyes were feeling less symptomatic. The ophthalmologist also indicated that the patient might need corneal transplants in the future if medical treatment did not stop the severe corneal involvement.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Rosacea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:659-664.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed papulopustular rosacea in this patient, along with ocular rosacea. The patient had advanced ocular rosacea with neovascularization on the cornea, which can lead to blindness.

Ocular rosacea is an advanced subtype of rosacea that is characterized by impressive, severe flushing with persistent telangiectasias, papules, and pustules. Patients may complain of watery eyes, a foreign-body sensation, burning, dryness, vision changes, and lid or periocular erythema. The eyelids are most commonly involved with telangiectasias, blepharitis, and recurrent hordeola and chalazia. Conjunctivitis may be chronic. Although corneal involvement is the least common, it can have the most devastating consequences. Corneal findings may include punctate erosions, corneal infiltrates, and corneal neovascularization. In the most severe cases, blood vessels may grow over the cornea and lead to blindness.

The FP in this case started the patient on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day and made an urgent referral to Ophthalmology. At a follow-up visit one month later, the FP noted that the patient had been started on ophthalmic cyclosporine for the ocular rosacea. The doxycycline had diminished the papules and pustules, and together with the ophthalmic cyclosporine, the patient’s eyes were feeling less symptomatic. The ophthalmologist also indicated that the patient might need corneal transplants in the future if medical treatment did not stop the severe corneal involvement.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Rosacea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:659-664.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Painful rash on face

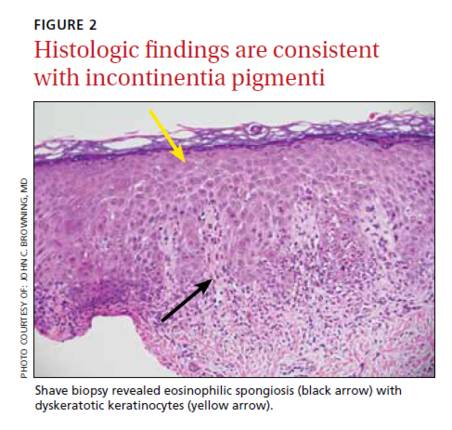

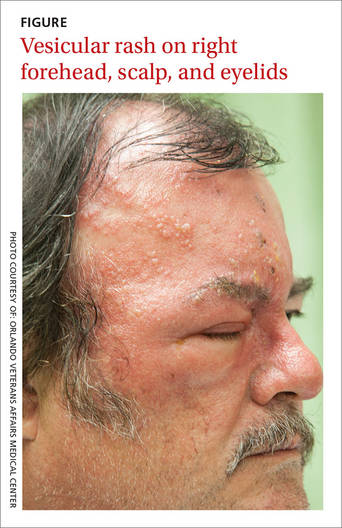

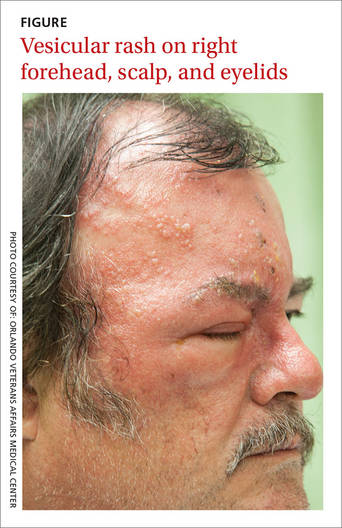

A 58-year-old man sought care at our clinic for burning in his right eye and a skin eruption on his right forehead and scalp. The pain in both had been getting progressively worse over the previous 10 days. The patient also reported that he had decreased vision in his right eye, as well as a fever, chills, photophobia, and headache. He had a history of psoriasis, which was being treated with adalimumab and methotrexate.

A physical exam revealed vesicles on an erythematous base on his right scalp, forehead, upper and lower eyelids, dorsum of his nose, and cheek (FIGURE). The distribution of the vesicles corresponded to the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

An ophthalmologic exam confirmed the diagnosis of herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), a serious condition that has been linked to reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) within the trigeminal ganglion.1 Primary infection with VZV results in varicella (chickenpox), whereas reactivation of a latent VZV infection within the sensory ganglia is known as herpes zoster.

HZO occurs in 10% to 20% of patients who have herpes zoster.2 The ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve is most frequently involved, and as many as 72% of patients experience direct ocular involvement.1

The acute syndrome begins with headache, fever, and unilateral pain in the affected eye, followed by the onset of a vesicular eruption along the trigeminal dermatome, hyperemic conjunctivitis, and episcleritis.3,4 Almost two-thirds of HZO patients develop corneal involvement.5

Rule out other types of vesicular eruptions

Impetigo, herpes simplex virus-type 1 (HSV-1), atopic dermatitis, acute contact dermatitis, and chickenpox should be included in the differential diagnosis of HZO.

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection. The lesions begin as papules and then progress to vesicles that enlarge and rapidly break down to form adherent crusts with a characteristic golden appearance. These lesions usually affect the face and extremities.

HSV-1 is characterized by multiple vesicular lesions superimposed on an erythematous base on the skin or mucous membranes of the mouth or lips.

Atopic dermatitis is characterized by pruritus, erythema, scale, and crusting. The flexural areas (neck, antecubital fossae, and popliteal fossae) are most commonly affected.6 Other common sites include the face, wrists, and forearms.

Acute contact dermatitis is an acute vesicular eruption accompanied by pruritus and erythema. The vesicles may be distributed in a characteristic linear pattern when a portion of an allergen (such as poison ivy) has made contact with the skin or when the patient has scratched the skin.

Chickenpox is a primary infection with VZV. The clinical manifestations include a prodrome of fever, malaise, or pharyngitis, followed by the development of a generalized vesicular rash. Although the appearance of the chickenpox rash is similar to that of HZO, herpes zoster is usually localized to a dermatome.

Diagnostic testing is rarely indicated

A history of VZV infection and the characteristic rash are usually adequate to make a diagnosis of HZO. Of note: vesicular lesions on the nose—known as Hutchinson’s sign—are associated with a high risk of HZO.7

If you suspect HZO, your patient will need an ophthalmologic exam, including an external inspection, testing of visual acuity, extraocular movements, and pupillary response, and various other exams (fundoscopy, anterior chamber slit lamp, and corneal).

A viral culture, direct immunofluorescence assay, Tzanck smear, or polymerase chain reaction may be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Treat with antivirals and steroid eye drops

An early diagnosis of HZO is critical to prevent progressive corneal involvement and potential loss of vision. The standard management is to initiate antiviral therapy with oral acyclovir (800 mg 5 times per day or 10 mg/kg intravenously 3 times per day), oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times per day), or oral famciclovir (500 mg 3 times per day), and to use adjunctive steroid eye drops that are prescribed by an ophthalmologist to reduce the inflammatory response.8

In otherwise healthy individuals in whom HZO causes minimal ocular symptoms, outpatient treatment with 7 to 10 days of antiviral medications is recommended. Immunodeficient patients and those taking immunosuppressive agents should be admitted to the hospital so they can receive intravenous antiviral medications.

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and underwent an ophthalmologic consultation and exam, which showed right erythematous conjunctiva and punctate corneal erosions. The iris, anterior vitreous, macula, and lens all appeared normal. He was given acyclovir 10 mg/kg intravenously and steroid ophthalmic drops, and his pain was controlled with oral oxycodone/acetaminophen (10 mg/325 mg) and ibuprofen 400 mg. Our patient continued to improve and was discharged on oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times per day and steroid eye drops with outpatient Ophthalmology follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mahmoud Farhoud, MD, Orlando Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 13800 Veterans Way, Orlando, FL 32827; [email protected].

1. Pavan-Langston D. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Neurology. 1995;45:S50-S51.

2. Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:S3-S12.

3. Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186: S91-S98.

4. Liesegang TJ. Diagnosis and therapy of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1216-1229.

5. Kaufman SC. Anterior segment complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:S24-S32.

6. Williams HC. Clinical practice. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2314-2324.

7. Tomkinson A, Roblin DG, Brown MJ. Hutchinson’s sign and its importance in rhinology. Rhinology. 1995;33:180-182.

8. Cohen EJ, Kessler J. Persistent dilemmas in zoster eye disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015.

A 58-year-old man sought care at our clinic for burning in his right eye and a skin eruption on his right forehead and scalp. The pain in both had been getting progressively worse over the previous 10 days. The patient also reported that he had decreased vision in his right eye, as well as a fever, chills, photophobia, and headache. He had a history of psoriasis, which was being treated with adalimumab and methotrexate.

A physical exam revealed vesicles on an erythematous base on his right scalp, forehead, upper and lower eyelids, dorsum of his nose, and cheek (FIGURE). The distribution of the vesicles corresponded to the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

An ophthalmologic exam confirmed the diagnosis of herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), a serious condition that has been linked to reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) within the trigeminal ganglion.1 Primary infection with VZV results in varicella (chickenpox), whereas reactivation of a latent VZV infection within the sensory ganglia is known as herpes zoster.

HZO occurs in 10% to 20% of patients who have herpes zoster.2 The ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve is most frequently involved, and as many as 72% of patients experience direct ocular involvement.1

The acute syndrome begins with headache, fever, and unilateral pain in the affected eye, followed by the onset of a vesicular eruption along the trigeminal dermatome, hyperemic conjunctivitis, and episcleritis.3,4 Almost two-thirds of HZO patients develop corneal involvement.5

Rule out other types of vesicular eruptions

Impetigo, herpes simplex virus-type 1 (HSV-1), atopic dermatitis, acute contact dermatitis, and chickenpox should be included in the differential diagnosis of HZO.

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection. The lesions begin as papules and then progress to vesicles that enlarge and rapidly break down to form adherent crusts with a characteristic golden appearance. These lesions usually affect the face and extremities.

HSV-1 is characterized by multiple vesicular lesions superimposed on an erythematous base on the skin or mucous membranes of the mouth or lips.

Atopic dermatitis is characterized by pruritus, erythema, scale, and crusting. The flexural areas (neck, antecubital fossae, and popliteal fossae) are most commonly affected.6 Other common sites include the face, wrists, and forearms.

Acute contact dermatitis is an acute vesicular eruption accompanied by pruritus and erythema. The vesicles may be distributed in a characteristic linear pattern when a portion of an allergen (such as poison ivy) has made contact with the skin or when the patient has scratched the skin.

Chickenpox is a primary infection with VZV. The clinical manifestations include a prodrome of fever, malaise, or pharyngitis, followed by the development of a generalized vesicular rash. Although the appearance of the chickenpox rash is similar to that of HZO, herpes zoster is usually localized to a dermatome.

Diagnostic testing is rarely indicated

A history of VZV infection and the characteristic rash are usually adequate to make a diagnosis of HZO. Of note: vesicular lesions on the nose—known as Hutchinson’s sign—are associated with a high risk of HZO.7

If you suspect HZO, your patient will need an ophthalmologic exam, including an external inspection, testing of visual acuity, extraocular movements, and pupillary response, and various other exams (fundoscopy, anterior chamber slit lamp, and corneal).

A viral culture, direct immunofluorescence assay, Tzanck smear, or polymerase chain reaction may be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Treat with antivirals and steroid eye drops

An early diagnosis of HZO is critical to prevent progressive corneal involvement and potential loss of vision. The standard management is to initiate antiviral therapy with oral acyclovir (800 mg 5 times per day or 10 mg/kg intravenously 3 times per day), oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times per day), or oral famciclovir (500 mg 3 times per day), and to use adjunctive steroid eye drops that are prescribed by an ophthalmologist to reduce the inflammatory response.8

In otherwise healthy individuals in whom HZO causes minimal ocular symptoms, outpatient treatment with 7 to 10 days of antiviral medications is recommended. Immunodeficient patients and those taking immunosuppressive agents should be admitted to the hospital so they can receive intravenous antiviral medications.

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and underwent an ophthalmologic consultation and exam, which showed right erythematous conjunctiva and punctate corneal erosions. The iris, anterior vitreous, macula, and lens all appeared normal. He was given acyclovir 10 mg/kg intravenously and steroid ophthalmic drops, and his pain was controlled with oral oxycodone/acetaminophen (10 mg/325 mg) and ibuprofen 400 mg. Our patient continued to improve and was discharged on oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times per day and steroid eye drops with outpatient Ophthalmology follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mahmoud Farhoud, MD, Orlando Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 13800 Veterans Way, Orlando, FL 32827; [email protected].

A 58-year-old man sought care at our clinic for burning in his right eye and a skin eruption on his right forehead and scalp. The pain in both had been getting progressively worse over the previous 10 days. The patient also reported that he had decreased vision in his right eye, as well as a fever, chills, photophobia, and headache. He had a history of psoriasis, which was being treated with adalimumab and methotrexate.

A physical exam revealed vesicles on an erythematous base on his right scalp, forehead, upper and lower eyelids, dorsum of his nose, and cheek (FIGURE). The distribution of the vesicles corresponded to the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

An ophthalmologic exam confirmed the diagnosis of herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), a serious condition that has been linked to reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) within the trigeminal ganglion.1 Primary infection with VZV results in varicella (chickenpox), whereas reactivation of a latent VZV infection within the sensory ganglia is known as herpes zoster.

HZO occurs in 10% to 20% of patients who have herpes zoster.2 The ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve is most frequently involved, and as many as 72% of patients experience direct ocular involvement.1

The acute syndrome begins with headache, fever, and unilateral pain in the affected eye, followed by the onset of a vesicular eruption along the trigeminal dermatome, hyperemic conjunctivitis, and episcleritis.3,4 Almost two-thirds of HZO patients develop corneal involvement.5

Rule out other types of vesicular eruptions

Impetigo, herpes simplex virus-type 1 (HSV-1), atopic dermatitis, acute contact dermatitis, and chickenpox should be included in the differential diagnosis of HZO.

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection. The lesions begin as papules and then progress to vesicles that enlarge and rapidly break down to form adherent crusts with a characteristic golden appearance. These lesions usually affect the face and extremities.

HSV-1 is characterized by multiple vesicular lesions superimposed on an erythematous base on the skin or mucous membranes of the mouth or lips.

Atopic dermatitis is characterized by pruritus, erythema, scale, and crusting. The flexural areas (neck, antecubital fossae, and popliteal fossae) are most commonly affected.6 Other common sites include the face, wrists, and forearms.

Acute contact dermatitis is an acute vesicular eruption accompanied by pruritus and erythema. The vesicles may be distributed in a characteristic linear pattern when a portion of an allergen (such as poison ivy) has made contact with the skin or when the patient has scratched the skin.

Chickenpox is a primary infection with VZV. The clinical manifestations include a prodrome of fever, malaise, or pharyngitis, followed by the development of a generalized vesicular rash. Although the appearance of the chickenpox rash is similar to that of HZO, herpes zoster is usually localized to a dermatome.

Diagnostic testing is rarely indicated

A history of VZV infection and the characteristic rash are usually adequate to make a diagnosis of HZO. Of note: vesicular lesions on the nose—known as Hutchinson’s sign—are associated with a high risk of HZO.7

If you suspect HZO, your patient will need an ophthalmologic exam, including an external inspection, testing of visual acuity, extraocular movements, and pupillary response, and various other exams (fundoscopy, anterior chamber slit lamp, and corneal).

A viral culture, direct immunofluorescence assay, Tzanck smear, or polymerase chain reaction may be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Treat with antivirals and steroid eye drops

An early diagnosis of HZO is critical to prevent progressive corneal involvement and potential loss of vision. The standard management is to initiate antiviral therapy with oral acyclovir (800 mg 5 times per day or 10 mg/kg intravenously 3 times per day), oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times per day), or oral famciclovir (500 mg 3 times per day), and to use adjunctive steroid eye drops that are prescribed by an ophthalmologist to reduce the inflammatory response.8

In otherwise healthy individuals in whom HZO causes minimal ocular symptoms, outpatient treatment with 7 to 10 days of antiviral medications is recommended. Immunodeficient patients and those taking immunosuppressive agents should be admitted to the hospital so they can receive intravenous antiviral medications.

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and underwent an ophthalmologic consultation and exam, which showed right erythematous conjunctiva and punctate corneal erosions. The iris, anterior vitreous, macula, and lens all appeared normal. He was given acyclovir 10 mg/kg intravenously and steroid ophthalmic drops, and his pain was controlled with oral oxycodone/acetaminophen (10 mg/325 mg) and ibuprofen 400 mg. Our patient continued to improve and was discharged on oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times per day and steroid eye drops with outpatient Ophthalmology follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mahmoud Farhoud, MD, Orlando Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 13800 Veterans Way, Orlando, FL 32827; [email protected].

1. Pavan-Langston D. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Neurology. 1995;45:S50-S51.

2. Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:S3-S12.

3. Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186: S91-S98.

4. Liesegang TJ. Diagnosis and therapy of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1216-1229.

5. Kaufman SC. Anterior segment complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:S24-S32.

6. Williams HC. Clinical practice. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2314-2324.

7. Tomkinson A, Roblin DG, Brown MJ. Hutchinson’s sign and its importance in rhinology. Rhinology. 1995;33:180-182.

8. Cohen EJ, Kessler J. Persistent dilemmas in zoster eye disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015.

1. Pavan-Langston D. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Neurology. 1995;45:S50-S51.

2. Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:S3-S12.

3. Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186: S91-S98.

4. Liesegang TJ. Diagnosis and therapy of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1216-1229.

5. Kaufman SC. Anterior segment complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:S24-S32.

6. Williams HC. Clinical practice. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2314-2324.

7. Tomkinson A, Roblin DG, Brown MJ. Hutchinson’s sign and its importance in rhinology. Rhinology. 1995;33:180-182.

8. Cohen EJ, Kessler J. Persistent dilemmas in zoster eye disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015.

Enlarged nose

The FP diagnosed rhinophymatous rosacea in this patient (along with erythematous rosacea on his cheeks). Rhinophymatous rosacea is characterized by hyperplasia of the sebaceous glands that form thickened confluent plaques on the nose known as rhinophyma. This hyperplasia can cause significant disfigurement to the forehead, eyelids, chin, and nose. Nasal disfiguration is seen more commonly in men than in women.

The FP prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and topical metronidazole gel 1% daily. During a follow-up appointment one month later, the patient noted that his cheeks improved but he did not see any changes in his nose. The FP offered to send him in for a surgical procedure to treat the rhinophyma. However, the patient was not interested in surgery at the time and continued the prescribed treatment.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Rosacea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:659-664.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed rhinophymatous rosacea in this patient (along with erythematous rosacea on his cheeks). Rhinophymatous rosacea is characterized by hyperplasia of the sebaceous glands that form thickened confluent plaques on the nose known as rhinophyma. This hyperplasia can cause significant disfigurement to the forehead, eyelids, chin, and nose. Nasal disfiguration is seen more commonly in men than in women.

The FP prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and topical metronidazole gel 1% daily. During a follow-up appointment one month later, the patient noted that his cheeks improved but he did not see any changes in his nose. The FP offered to send him in for a surgical procedure to treat the rhinophyma. However, the patient was not interested in surgery at the time and continued the prescribed treatment.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Rosacea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:659-664.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed rhinophymatous rosacea in this patient (along with erythematous rosacea on his cheeks). Rhinophymatous rosacea is characterized by hyperplasia of the sebaceous glands that form thickened confluent plaques on the nose known as rhinophyma. This hyperplasia can cause significant disfigurement to the forehead, eyelids, chin, and nose. Nasal disfiguration is seen more commonly in men than in women.

The FP prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and topical metronidazole gel 1% daily. During a follow-up appointment one month later, the patient noted that his cheeks improved but he did not see any changes in his nose. The FP offered to send him in for a surgical procedure to treat the rhinophyma. However, the patient was not interested in surgery at the time and continued the prescribed treatment.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Rosacea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:659-664.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Red rash on cheeks

The FP diagnosed erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in this patient. This stage of rosacea is characterized by frequent episodes of mild to severe flushing with persistent central facial erythema. As its name suggests, there are many telangiectasias along with the erythema.

The standard therapy for papulopustular rosacea—oral doxycycline and topical metronidazole—is less effective for erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. There is, however, a new FDA-approved medication (brimonidine gel) that treats the erythema of rosacea. There have been numerous studies that show this gel is better than a placebo gel for reducing the erythema of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. However, if the new gel is too costly for the patient, an alternative is to use over-the-counter oxymetazoline and have the patient apply this directly to the skin on a daily basis.

In this case, the FP suggested that the patient avoid food, drink, and activities that exacerbate his flushing. The patient was also given a prescription for brimonidine gel with an explanation about the optional use of over-the-counter oxymetazoline.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Rosacea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:659-664.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in this patient. This stage of rosacea is characterized by frequent episodes of mild to severe flushing with persistent central facial erythema. As its name suggests, there are many telangiectasias along with the erythema.

The standard therapy for papulopustular rosacea—oral doxycycline and topical metronidazole—is less effective for erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. There is, however, a new FDA-approved medication (brimonidine gel) that treats the erythema of rosacea. There have been numerous studies that show this gel is better than a placebo gel for reducing the erythema of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. However, if the new gel is too costly for the patient, an alternative is to use over-the-counter oxymetazoline and have the patient apply this directly to the skin on a daily basis.

In this case, the FP suggested that the patient avoid food, drink, and activities that exacerbate his flushing. The patient was also given a prescription for brimonidine gel with an explanation about the optional use of over-the-counter oxymetazoline.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Rosacea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:659-664.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in this patient. This stage of rosacea is characterized by frequent episodes of mild to severe flushing with persistent central facial erythema. As its name suggests, there are many telangiectasias along with the erythema.

The standard therapy for papulopustular rosacea—oral doxycycline and topical metronidazole—is less effective for erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. There is, however, a new FDA-approved medication (brimonidine gel) that treats the erythema of rosacea. There have been numerous studies that show this gel is better than a placebo gel for reducing the erythema of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. However, if the new gel is too costly for the patient, an alternative is to use over-the-counter oxymetazoline and have the patient apply this directly to the skin on a daily basis.

In this case, the FP suggested that the patient avoid food, drink, and activities that exacerbate his flushing. The patient was also given a prescription for brimonidine gel with an explanation about the optional use of over-the-counter oxymetazoline.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Rosacea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:659-664.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Worsening rash on face

This patient had rosacea, an inflammatory condition of the face and eyes that mostly affects adults (women more often than men). Patients’ cheeks and noses become reddened, and they develop telangiectasias and papulopustular eruptions. Rosacea is common in fair-skinned people of Celtic and northern European heritage.

In this case, the FP counseled the patient about the diagnosis of rosacea and the factors that can worsen it, including exposure to the sun, alcohol, hot beverages, and spicy foods. The FP started the patient on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily with the intent to taper it to once daily in the future. In addition, he wrote a prescription for metronidazole gel to be used once daily.

The patient agreed to wear a hat and stay out of the sun during the middle of the day. She also promised to look for a sunscreen she could tolerate. A follow-up appointment was arranged for the following month.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Rosacea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:659-664.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

This patient had rosacea, an inflammatory condition of the face and eyes that mostly affects adults (women more often than men). Patients’ cheeks and noses become reddened, and they develop telangiectasias and papulopustular eruptions. Rosacea is common in fair-skinned people of Celtic and northern European heritage.

In this case, the FP counseled the patient about the diagnosis of rosacea and the factors that can worsen it, including exposure to the sun, alcohol, hot beverages, and spicy foods. The FP started the patient on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily with the intent to taper it to once daily in the future. In addition, he wrote a prescription for metronidazole gel to be used once daily.

The patient agreed to wear a hat and stay out of the sun during the middle of the day. She also promised to look for a sunscreen she could tolerate. A follow-up appointment was arranged for the following month.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Rosacea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:659-664.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

This patient had rosacea, an inflammatory condition of the face and eyes that mostly affects adults (women more often than men). Patients’ cheeks and noses become reddened, and they develop telangiectasias and papulopustular eruptions. Rosacea is common in fair-skinned people of Celtic and northern European heritage.

In this case, the FP counseled the patient about the diagnosis of rosacea and the factors that can worsen it, including exposure to the sun, alcohol, hot beverages, and spicy foods. The FP started the patient on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily with the intent to taper it to once daily in the future. In addition, he wrote a prescription for metronidazole gel to be used once daily.

The patient agreed to wear a hat and stay out of the sun during the middle of the day. She also promised to look for a sunscreen she could tolerate. A follow-up appointment was arranged for the following month.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Rosacea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:659-664.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Crusted lesions on palms

Based on the physical findings and results of the lab work, the patient was given a diagnosis of crusted scabies.

Crusted scabies, also known as Norwegian scabies, is an uncommon form of scabies infestation. The causative organism is the burrowing mite Sarcoptes scabiei (the same organism involved in ordinary scabies). The difference, though, is that the level of infestation with crusted scabies is more severe.

Definitive diagnosis depends on microscopic identification of the mites, their eggs, eggshell fragments, or mite pellets. Patients also have extremely elevated total serum immunoglobulin E and G levels, and are predisposed to secondary infections.

Patients with dementia or mental retardation and those who are immunocompromised are most susceptible to the disease. (The patient described here had a history of dementia.) In nursing homes, patients with unrecognized crusted scabies are often the source of transmission to other residents and staff members. A crusted scabies host may harbor more than one million mites.

Because of the large number of mites in the hyperkeratotic lesions, this disease is difficult to manage. Daily application of topical scabicidal agents such as 5% permethrin cream, 1% lindane cream, 6% to 10% sulfur-based topical agents, or 12.5% benzyl benzoate lotion is recommended. A mixture of keratolytic agents on the hyperkeratotic areas might help the topical medication gain access to the target areas. Another effective approach is prescribing a single oral dose of ivermectin 200 mcg/kg with a topical preparation. Most modern treatments of crusted scabies involve the use of oral ivermectin and topical permethrin given at the time of diagnosis and repeated in 7 to 10 days. Clothes, bedding, and towels should also be decontaminated by machine washing them in hot water and drying them in the hot cycle.

In this case, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and her skin lesions were treated with topical mesulphen once daily for 10 days. Gradually, the lesions improved and she returned to the nursing home a month later.

Adapted from: Liaw FY, Huang CF, Fang WH, et al. Asymptomatic crusted lesions on the palms. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:43-46.

Based on the physical findings and results of the lab work, the patient was given a diagnosis of crusted scabies.

Crusted scabies, also known as Norwegian scabies, is an uncommon form of scabies infestation. The causative organism is the burrowing mite Sarcoptes scabiei (the same organism involved in ordinary scabies). The difference, though, is that the level of infestation with crusted scabies is more severe.

Definitive diagnosis depends on microscopic identification of the mites, their eggs, eggshell fragments, or mite pellets. Patients also have extremely elevated total serum immunoglobulin E and G levels, and are predisposed to secondary infections.

Patients with dementia or mental retardation and those who are immunocompromised are most susceptible to the disease. (The patient described here had a history of dementia.) In nursing homes, patients with unrecognized crusted scabies are often the source of transmission to other residents and staff members. A crusted scabies host may harbor more than one million mites.

Because of the large number of mites in the hyperkeratotic lesions, this disease is difficult to manage. Daily application of topical scabicidal agents such as 5% permethrin cream, 1% lindane cream, 6% to 10% sulfur-based topical agents, or 12.5% benzyl benzoate lotion is recommended. A mixture of keratolytic agents on the hyperkeratotic areas might help the topical medication gain access to the target areas. Another effective approach is prescribing a single oral dose of ivermectin 200 mcg/kg with a topical preparation. Most modern treatments of crusted scabies involve the use of oral ivermectin and topical permethrin given at the time of diagnosis and repeated in 7 to 10 days. Clothes, bedding, and towels should also be decontaminated by machine washing them in hot water and drying them in the hot cycle.

In this case, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and her skin lesions were treated with topical mesulphen once daily for 10 days. Gradually, the lesions improved and she returned to the nursing home a month later.

Adapted from: Liaw FY, Huang CF, Fang WH, et al. Asymptomatic crusted lesions on the palms. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:43-46.

Based on the physical findings and results of the lab work, the patient was given a diagnosis of crusted scabies.

Crusted scabies, also known as Norwegian scabies, is an uncommon form of scabies infestation. The causative organism is the burrowing mite Sarcoptes scabiei (the same organism involved in ordinary scabies). The difference, though, is that the level of infestation with crusted scabies is more severe.

Definitive diagnosis depends on microscopic identification of the mites, their eggs, eggshell fragments, or mite pellets. Patients also have extremely elevated total serum immunoglobulin E and G levels, and are predisposed to secondary infections.

Patients with dementia or mental retardation and those who are immunocompromised are most susceptible to the disease. (The patient described here had a history of dementia.) In nursing homes, patients with unrecognized crusted scabies are often the source of transmission to other residents and staff members. A crusted scabies host may harbor more than one million mites.

Because of the large number of mites in the hyperkeratotic lesions, this disease is difficult to manage. Daily application of topical scabicidal agents such as 5% permethrin cream, 1% lindane cream, 6% to 10% sulfur-based topical agents, or 12.5% benzyl benzoate lotion is recommended. A mixture of keratolytic agents on the hyperkeratotic areas might help the topical medication gain access to the target areas. Another effective approach is prescribing a single oral dose of ivermectin 200 mcg/kg with a topical preparation. Most modern treatments of crusted scabies involve the use of oral ivermectin and topical permethrin given at the time of diagnosis and repeated in 7 to 10 days. Clothes, bedding, and towels should also be decontaminated by machine washing them in hot water and drying them in the hot cycle.

In this case, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and her skin lesions were treated with topical mesulphen once daily for 10 days. Gradually, the lesions improved and she returned to the nursing home a month later.

Adapted from: Liaw FY, Huang CF, Fang WH, et al. Asymptomatic crusted lesions on the palms. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:43-46.

Linear rash from shoulder to wrist

A 19-year-old woman came to our outpatient clinic with a rash on her upper left arm that she’d had for a month. Small pink and flesh-colored spots that first appeared over her left shoulder had spread down her arm and forearm to her wrist. The rash was initially scattered, but within a few weeks it had joined together to form a linear band. It was not itchy or painful.

Our patient had no changes to her fingernails, no contact with potential allergens, and no history of skin disease, atopy, or drug allergies. She was not taking any medication, but had received the second of 3 doses of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine 2 months before she’d developed the rash. She had tried to treat the rash with an over-the-counter steroid cream, but it had not been effective.

On physical examination, we noted flat-topped, slightly scaly, pinkish papules that were about 3 mm in diameter and formed an interrupted linear pattern that extended down the patient’s left shoulder and arm, cubital fossa, and forearm to her wrist (FIGURE). There were no vesicles, pustules, erosions, ulcers, or excoriation. The rash was non-tender and Koebner’s phenomenon was absent.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen striatus

Based on the appearance and distribution of our patient’s lesions, we made a clinical diagnosis of lichen striatus, an uncommon condition that typically affects children younger than age 15.1

Lichen striatus usually presents as papulovesicular lesions in bands that follow Blaschko’s lines. (Blaschko’s lines are patterns of lines on the skin that represent the developmental growth pattern of the skin during epidermal cell migration; these lines usually aren’t visible but can be seen in patients with certain skin diseases.2) Lichen striatus most frequently affects the neck, trunk, and limbs; nail involvement is rare.1 Patients with lichen striatus are usually asymptomatic, but they occasionally have various degrees of pruritus.

The etiology of lichen striatus is unknown, but it has been reported to occur after flu-like illnesses, tonsillitis, the application of retinoic acid lotions, sunburn, hepatitis B virus infection, and bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination.3 There is no documented relationship between lichen striatus and the HPV vaccine. Atopy may be a predisposing factor for lichen striatus, but does not trigger the disease.1

The diagnosis is typically made based on the appearance and distribution of the rash. Skin biopsy is rarely needed to establish the diagnosis.3

Distinguishing lichen striatus from other linear skin disorders

Other lesions that could follow Blaschko’s lines include linear psoriasis, linear lichen planus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, and linear Darier’s disease (keratosis follicularis).3

Linear psoriasis usually presents as late-onset, mildly pruritic linear scaly plaques with a positive Auspitz sign. This form of psoriasis responds well to topical or systemic psoriatic treatment, such as topical steroids, coal tar preparation, or vitamin D derivatives.4

Linear lichen planus involves pruritic, hyperpigmented, well-demarcated, flat-topped papules and small, thin plaques without scale. Linear lichen planus can be the result of scratching or injuring the skin.5

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus usually presents as erythematous and verrucous papules with a psoriasiform appearance. It is accompanied by intense pruritus. Girls are more commonly affected than boys and the condition is refractory to psoriatic therapy.6

Darier’s disease (keratosis follicularis) is an autosomal dominant inherited disease that usually presents as an eruption of keratotic papules. Nails may be affected, with longitudinal nail striations and subungual hyperkeratosis.7

Lichen striatus typically resolves without treatment

The role of topical steroids, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, or tacrolimus for treating ichen striatus is unclear.8 Observation is thought to be the best approach.8 Lichen striatus usually resolves spontaneously in 6 to 9 months, although relapses have been reported.3

We advised our patient that no treatment was required and asked that she return for a follow-up appointment in 2 weeks. When she came in for her follow-up appointment, her rash had stopped spreading. Approximately 6 months after onset, the rash was less pink.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kai Lim Chow, MBChB, FHKAM, Tseung Kwan O Jockey Club General Outpatient Clinic, 99 Po Lam Road North, G/F, Tseung Kwan O, Hong Kong, China; [email protected].

1. Patrizi A, Neri I, Fiorentini C, et al. Lichen striatus: clinical and laboratory features of 115 children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:197-204.

2. Keegan BR, Kamino H, Fangman W, et al. “Pediatric blaschkitis”: expanding the spectrum of childhood acquired Blaschkolinear dermatoses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:621-627.

3. Skvarka CB, Ko CJ. Lichenoid dermatoses. In: Schwarzenberger K, Werchniak AE, Ko CJ, eds. General Dermatology: Requisites in Dermatology. London: Elsevier; 2008;13:204-205.

4. Happle R. Linear psoriasis and ILVEN: is lumping or splitting appropriate? Dermatology. 2006;212:101-102.

5. Batra P, Wang N, Kamino H, et al. Linear lichen planus. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:16.

6. Kumar CA, Yeluri G, Raghav N. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus syndrome with its polymorphic presentation—A rare case report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3:119-122.

7. Meziane M, Chraibi R, Kihel N, et al. Linear Darier disease. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:11.

8. Mu EW, Abuav R, Cohen BA. Facial lichen striatus in children: retracing the lines of Blaschko. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:364-366.

A 19-year-old woman came to our outpatient clinic with a rash on her upper left arm that she’d had for a month. Small pink and flesh-colored spots that first appeared over her left shoulder had spread down her arm and forearm to her wrist. The rash was initially scattered, but within a few weeks it had joined together to form a linear band. It was not itchy or painful.

Our patient had no changes to her fingernails, no contact with potential allergens, and no history of skin disease, atopy, or drug allergies. She was not taking any medication, but had received the second of 3 doses of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine 2 months before she’d developed the rash. She had tried to treat the rash with an over-the-counter steroid cream, but it had not been effective.

On physical examination, we noted flat-topped, slightly scaly, pinkish papules that were about 3 mm in diameter and formed an interrupted linear pattern that extended down the patient’s left shoulder and arm, cubital fossa, and forearm to her wrist (FIGURE). There were no vesicles, pustules, erosions, ulcers, or excoriation. The rash was non-tender and Koebner’s phenomenon was absent.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen striatus

Based on the appearance and distribution of our patient’s lesions, we made a clinical diagnosis of lichen striatus, an uncommon condition that typically affects children younger than age 15.1

Lichen striatus usually presents as papulovesicular lesions in bands that follow Blaschko’s lines. (Blaschko’s lines are patterns of lines on the skin that represent the developmental growth pattern of the skin during epidermal cell migration; these lines usually aren’t visible but can be seen in patients with certain skin diseases.2) Lichen striatus most frequently affects the neck, trunk, and limbs; nail involvement is rare.1 Patients with lichen striatus are usually asymptomatic, but they occasionally have various degrees of pruritus.

The etiology of lichen striatus is unknown, but it has been reported to occur after flu-like illnesses, tonsillitis, the application of retinoic acid lotions, sunburn, hepatitis B virus infection, and bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination.3 There is no documented relationship between lichen striatus and the HPV vaccine. Atopy may be a predisposing factor for lichen striatus, but does not trigger the disease.1

The diagnosis is typically made based on the appearance and distribution of the rash. Skin biopsy is rarely needed to establish the diagnosis.3

Distinguishing lichen striatus from other linear skin disorders

Other lesions that could follow Blaschko’s lines include linear psoriasis, linear lichen planus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, and linear Darier’s disease (keratosis follicularis).3

Linear psoriasis usually presents as late-onset, mildly pruritic linear scaly plaques with a positive Auspitz sign. This form of psoriasis responds well to topical or systemic psoriatic treatment, such as topical steroids, coal tar preparation, or vitamin D derivatives.4

Linear lichen planus involves pruritic, hyperpigmented, well-demarcated, flat-topped papules and small, thin plaques without scale. Linear lichen planus can be the result of scratching or injuring the skin.5

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus usually presents as erythematous and verrucous papules with a psoriasiform appearance. It is accompanied by intense pruritus. Girls are more commonly affected than boys and the condition is refractory to psoriatic therapy.6

Darier’s disease (keratosis follicularis) is an autosomal dominant inherited disease that usually presents as an eruption of keratotic papules. Nails may be affected, with longitudinal nail striations and subungual hyperkeratosis.7

Lichen striatus typically resolves without treatment

The role of topical steroids, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, or tacrolimus for treating ichen striatus is unclear.8 Observation is thought to be the best approach.8 Lichen striatus usually resolves spontaneously in 6 to 9 months, although relapses have been reported.3

We advised our patient that no treatment was required and asked that she return for a follow-up appointment in 2 weeks. When she came in for her follow-up appointment, her rash had stopped spreading. Approximately 6 months after onset, the rash was less pink.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kai Lim Chow, MBChB, FHKAM, Tseung Kwan O Jockey Club General Outpatient Clinic, 99 Po Lam Road North, G/F, Tseung Kwan O, Hong Kong, China; [email protected].

A 19-year-old woman came to our outpatient clinic with a rash on her upper left arm that she’d had for a month. Small pink and flesh-colored spots that first appeared over her left shoulder had spread down her arm and forearm to her wrist. The rash was initially scattered, but within a few weeks it had joined together to form a linear band. It was not itchy or painful.

Our patient had no changes to her fingernails, no contact with potential allergens, and no history of skin disease, atopy, or drug allergies. She was not taking any medication, but had received the second of 3 doses of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine 2 months before she’d developed the rash. She had tried to treat the rash with an over-the-counter steroid cream, but it had not been effective.

On physical examination, we noted flat-topped, slightly scaly, pinkish papules that were about 3 mm in diameter and formed an interrupted linear pattern that extended down the patient’s left shoulder and arm, cubital fossa, and forearm to her wrist (FIGURE). There were no vesicles, pustules, erosions, ulcers, or excoriation. The rash was non-tender and Koebner’s phenomenon was absent.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen striatus

Based on the appearance and distribution of our patient’s lesions, we made a clinical diagnosis of lichen striatus, an uncommon condition that typically affects children younger than age 15.1