User login

Swollen right hand and forearm • minor trauma to hand • previous diagnosis of cellulitis • Dx?

THE CASE

A 63-year-old woman with a history of hyperlipidemia presented to our hospital with a swollen right hand. The patient noted that she had closed her hand in a car door one week earlier, causing minor trauma to the right third metacarpophalangeal joint. Shortly after injuring her hand, she’d sought care at an outpatient facility, where she was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and a prescription for an oral antibiotic. The swelling, however, worsened, prompting her visit to our hospital. She was admitted for further work-up and started on intravenous (IV) antibiotics.

Her family history included a sister with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and a maternal aunt with breast cancer. The patient denied oral contraceptive use or a personal history of malignancy. On physical examination, her right hand and forearm were swollen, tender, and erythematous.

THE DIAGNOSIS

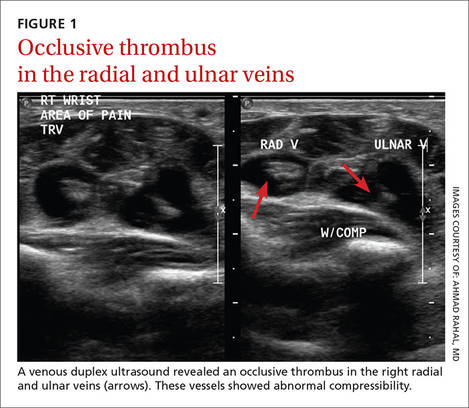

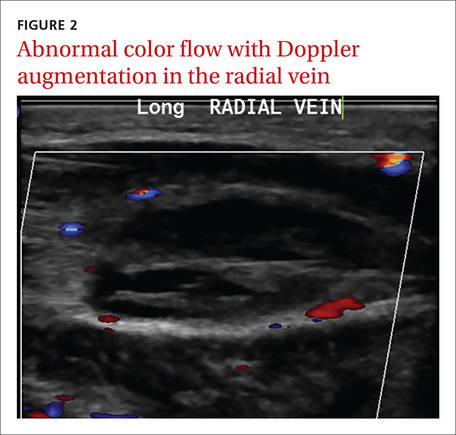

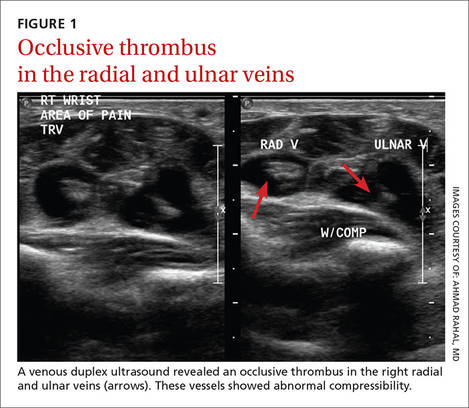

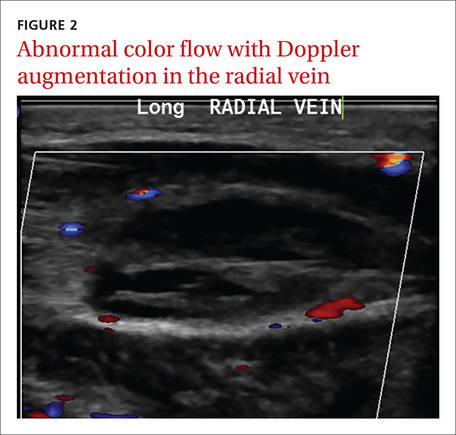

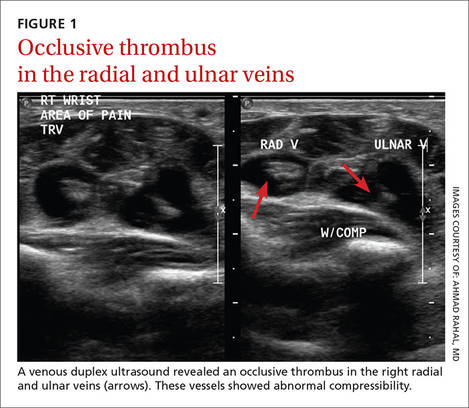

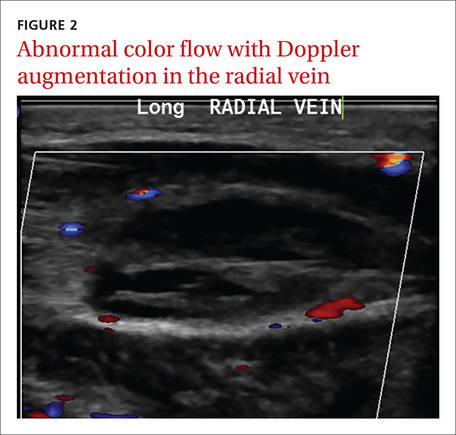

Laboratory data showed a normal complete blood count and complete metabolic panel. The patient’s sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were elevated at 65 mm/hr and 110 mg/L, respectively. The patient was not improving on IV antibiotics, so we performed a right upper extremity venous duplex ultrasound. The ultrasound showed an occlusive thrombus in the right ulnar and radial veins (FIGURES 1 AND 2), and we diagnosed the patient with upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (UEDVT). (The timing of the diagnosis, relative to the injury to the patient’s hand, appeared to have been coincidental.)

Further work-up revealed normal complement C3 and C4 tests, as well as negative antinuclear, anti-double stranded DNA, anti-Smith, and anticardiolipin antibody tests. Similarly, a factor II DNA analysis was negative. However, the patient was positive for the factor V Leiden heterozygous mutation.

|

|

DISCUSSION

More than 350,000 people are diagnosed with DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE) in the United States each year.1 Up to 4% of all DVTs involve the upper extremities.2 Secondary UEDVT, which occurs in patients with central venous catheters, malignancies, and thrombophilia, accounts for the majority of UEDVT cases; primary UEDVT is less common.3

Large epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that hypercoagulability is a risk factor for lower extremity DVT, but few data exist on the role of coagulation abnormalities in patients with primary UEDVT. The prevalence of clotting abnormalities in patients with primary UEDVT ranges from 8% to 43%.4,5 Factor V Leiden is the most common cause of inherited thrombophilia. Patients with heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation have a 7-fold increased risk of venous thrombosis.6

Héron and colleagues7 reported that 16 of 51 patients with at least one clotting abnormality had primary UEDVT. Factor V Leiden was found in 5 of those patients (20%). Interestingly, 3 of the 5 carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation were older than 45 years. Our patient was 63, which was consistent with these findings.

Malignancy is also an important risk factor for UEDVT.8,9 In patients with a DVT in an unusual location, age- and sex-appropriate cancer screenings are strongly recommended. (Our patient had undergone a colonoscopy 8 years earlier, which was normal. She’d also had a recent mammogram and Pap smear, which were normal, as well.)

It’s often difficult to distinguish between cellulitis and UEDVT

The differential diagnosis for UEDVT includes effort thrombosis (also known as Paget-Schroetter syndrome) and cellulitis.

Effort thrombosis usually occurs in young, otherwise healthy individuals and almost exclusively in the axillary and subclavian veins. Our patient’s age and a venous duplex ultrasound ruled out any thrombosis in these locations.

Distinguishing cellulitis from UEDVT based on clinical features can be difficult. In both conditions, the limb is swollen and painful and the skin is warm and erythematous. As a result, each condition is often misdiagnosed as the other.

But there are features that distinguish the 2. In patients with UEDVT, you’re likely to see limb pain and a palpable cord (a hard, thickened palpable vein along the line of the deep veins). On the other hand, patients with cellulitis tend to have more systemic symptoms, such as fever, chills, and swollen lymph nodes, as well as skin breakdown, ulcers, and pus.

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends that the initial evaluation for patients with suspected UEDVT be a combined modality ultrasound (compression with either Doppler or color Doppler) rather than D-dimer or venography.10 Quickly arriving at a proper diagnosis is critical, given that up to one-third of patients with UEDVT will develop a PE.7 Other complications include superior vena cava syndrome, septic thrombophlebitis, thoracic duct obstruction, and brachial plexopathy.11

Treat with anticoagulants for no longer than 3 months

The ACCP also recommends that patients who have UEDVT that isn’t associated with a central venous catheter or with cancer be treated with anticoagulation for no longer than 3 months.10

Our patient was started on enoxaparin and warfarin. After 5 days at our hospital, she was taken off the enoxaparin and discharged home on warfarin 5 mg/d. The swelling completely resolved one week later.

THE TAKEAWAY

Ulnar and radial DVT in a patient with factor V Leiden mutation is a rare condition. UEDVT should be included in the differential diagnosis for cellulitis whenever the diagnosis is uncertain or the patient doesn’t respond to antibiotics. Factor V Leiden mutation appears to be a risk factor in UEDVT and testing for it should be considered.

1. Office of the Surgeon General (US); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (US). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44178/. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2008.

2. Sawyer GA, Hayda R. Upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis following humeral shaft fracture. Orthopedics. 2011;34:141.

3. Leebeek FW, Stadhouders NA, van Stein D, et al. Hypercoagulability states in upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis. Am J Hematol. 2001;67:15-19.

4. Prandoni P, Polistena P, Bernardi E, et al. Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Risk factors, diagnosis, and complications. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:57-62.

5. Ruggeri M, Castaman G, Tosetto A, et al. Low prevalence of thrombophilic coagulation defects in patients with deep vein thrombosis of the upper limbs. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1997;8:191-194.

6. Ornstein DL, Cushman M. Cardiology patient page. Factor V Leiden. Circulation. 2003;107:e94-e97.

7. Héron E, Lozinguez O, Alhenc-Gelas M, et al. Hypercoagulable states in primary upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:382-386.

8. Linnemann B, Meister F, Schwonberg J, et al; MAISTHRO registry. Hereditary and acquired thrombophilia in patients with upper extremity deep-vein thrombosis. Results from the MAISTHRO registry. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:440-446.

9. Monreal M, Lafoz E, Ruiz J, et al. Upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A prospective study. Chest. 1991;99:280-283.

10. Holbrook A, Schulman S, Witt DM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Evidence-based management of anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e152S-e184S.

11. Becker DM, Philbrick JT, Walker FB 4th. Axillary and subclavian venous thrombosis. Prognosis and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1934-1943.

THE CASE

A 63-year-old woman with a history of hyperlipidemia presented to our hospital with a swollen right hand. The patient noted that she had closed her hand in a car door one week earlier, causing minor trauma to the right third metacarpophalangeal joint. Shortly after injuring her hand, she’d sought care at an outpatient facility, where she was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and a prescription for an oral antibiotic. The swelling, however, worsened, prompting her visit to our hospital. She was admitted for further work-up and started on intravenous (IV) antibiotics.

Her family history included a sister with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and a maternal aunt with breast cancer. The patient denied oral contraceptive use or a personal history of malignancy. On physical examination, her right hand and forearm were swollen, tender, and erythematous.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Laboratory data showed a normal complete blood count and complete metabolic panel. The patient’s sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were elevated at 65 mm/hr and 110 mg/L, respectively. The patient was not improving on IV antibiotics, so we performed a right upper extremity venous duplex ultrasound. The ultrasound showed an occlusive thrombus in the right ulnar and radial veins (FIGURES 1 AND 2), and we diagnosed the patient with upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (UEDVT). (The timing of the diagnosis, relative to the injury to the patient’s hand, appeared to have been coincidental.)

Further work-up revealed normal complement C3 and C4 tests, as well as negative antinuclear, anti-double stranded DNA, anti-Smith, and anticardiolipin antibody tests. Similarly, a factor II DNA analysis was negative. However, the patient was positive for the factor V Leiden heterozygous mutation.

|

|

DISCUSSION

More than 350,000 people are diagnosed with DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE) in the United States each year.1 Up to 4% of all DVTs involve the upper extremities.2 Secondary UEDVT, which occurs in patients with central venous catheters, malignancies, and thrombophilia, accounts for the majority of UEDVT cases; primary UEDVT is less common.3

Large epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that hypercoagulability is a risk factor for lower extremity DVT, but few data exist on the role of coagulation abnormalities in patients with primary UEDVT. The prevalence of clotting abnormalities in patients with primary UEDVT ranges from 8% to 43%.4,5 Factor V Leiden is the most common cause of inherited thrombophilia. Patients with heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation have a 7-fold increased risk of venous thrombosis.6

Héron and colleagues7 reported that 16 of 51 patients with at least one clotting abnormality had primary UEDVT. Factor V Leiden was found in 5 of those patients (20%). Interestingly, 3 of the 5 carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation were older than 45 years. Our patient was 63, which was consistent with these findings.

Malignancy is also an important risk factor for UEDVT.8,9 In patients with a DVT in an unusual location, age- and sex-appropriate cancer screenings are strongly recommended. (Our patient had undergone a colonoscopy 8 years earlier, which was normal. She’d also had a recent mammogram and Pap smear, which were normal, as well.)

It’s often difficult to distinguish between cellulitis and UEDVT

The differential diagnosis for UEDVT includes effort thrombosis (also known as Paget-Schroetter syndrome) and cellulitis.

Effort thrombosis usually occurs in young, otherwise healthy individuals and almost exclusively in the axillary and subclavian veins. Our patient’s age and a venous duplex ultrasound ruled out any thrombosis in these locations.

Distinguishing cellulitis from UEDVT based on clinical features can be difficult. In both conditions, the limb is swollen and painful and the skin is warm and erythematous. As a result, each condition is often misdiagnosed as the other.

But there are features that distinguish the 2. In patients with UEDVT, you’re likely to see limb pain and a palpable cord (a hard, thickened palpable vein along the line of the deep veins). On the other hand, patients with cellulitis tend to have more systemic symptoms, such as fever, chills, and swollen lymph nodes, as well as skin breakdown, ulcers, and pus.

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends that the initial evaluation for patients with suspected UEDVT be a combined modality ultrasound (compression with either Doppler or color Doppler) rather than D-dimer or venography.10 Quickly arriving at a proper diagnosis is critical, given that up to one-third of patients with UEDVT will develop a PE.7 Other complications include superior vena cava syndrome, septic thrombophlebitis, thoracic duct obstruction, and brachial plexopathy.11

Treat with anticoagulants for no longer than 3 months

The ACCP also recommends that patients who have UEDVT that isn’t associated with a central venous catheter or with cancer be treated with anticoagulation for no longer than 3 months.10

Our patient was started on enoxaparin and warfarin. After 5 days at our hospital, she was taken off the enoxaparin and discharged home on warfarin 5 mg/d. The swelling completely resolved one week later.

THE TAKEAWAY

Ulnar and radial DVT in a patient with factor V Leiden mutation is a rare condition. UEDVT should be included in the differential diagnosis for cellulitis whenever the diagnosis is uncertain or the patient doesn’t respond to antibiotics. Factor V Leiden mutation appears to be a risk factor in UEDVT and testing for it should be considered.

THE CASE

A 63-year-old woman with a history of hyperlipidemia presented to our hospital with a swollen right hand. The patient noted that she had closed her hand in a car door one week earlier, causing minor trauma to the right third metacarpophalangeal joint. Shortly after injuring her hand, she’d sought care at an outpatient facility, where she was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and a prescription for an oral antibiotic. The swelling, however, worsened, prompting her visit to our hospital. She was admitted for further work-up and started on intravenous (IV) antibiotics.

Her family history included a sister with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and a maternal aunt with breast cancer. The patient denied oral contraceptive use or a personal history of malignancy. On physical examination, her right hand and forearm were swollen, tender, and erythematous.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Laboratory data showed a normal complete blood count and complete metabolic panel. The patient’s sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were elevated at 65 mm/hr and 110 mg/L, respectively. The patient was not improving on IV antibiotics, so we performed a right upper extremity venous duplex ultrasound. The ultrasound showed an occlusive thrombus in the right ulnar and radial veins (FIGURES 1 AND 2), and we diagnosed the patient with upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (UEDVT). (The timing of the diagnosis, relative to the injury to the patient’s hand, appeared to have been coincidental.)

Further work-up revealed normal complement C3 and C4 tests, as well as negative antinuclear, anti-double stranded DNA, anti-Smith, and anticardiolipin antibody tests. Similarly, a factor II DNA analysis was negative. However, the patient was positive for the factor V Leiden heterozygous mutation.

|

|

DISCUSSION

More than 350,000 people are diagnosed with DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE) in the United States each year.1 Up to 4% of all DVTs involve the upper extremities.2 Secondary UEDVT, which occurs in patients with central venous catheters, malignancies, and thrombophilia, accounts for the majority of UEDVT cases; primary UEDVT is less common.3

Large epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that hypercoagulability is a risk factor for lower extremity DVT, but few data exist on the role of coagulation abnormalities in patients with primary UEDVT. The prevalence of clotting abnormalities in patients with primary UEDVT ranges from 8% to 43%.4,5 Factor V Leiden is the most common cause of inherited thrombophilia. Patients with heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation have a 7-fold increased risk of venous thrombosis.6

Héron and colleagues7 reported that 16 of 51 patients with at least one clotting abnormality had primary UEDVT. Factor V Leiden was found in 5 of those patients (20%). Interestingly, 3 of the 5 carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation were older than 45 years. Our patient was 63, which was consistent with these findings.

Malignancy is also an important risk factor for UEDVT.8,9 In patients with a DVT in an unusual location, age- and sex-appropriate cancer screenings are strongly recommended. (Our patient had undergone a colonoscopy 8 years earlier, which was normal. She’d also had a recent mammogram and Pap smear, which were normal, as well.)

It’s often difficult to distinguish between cellulitis and UEDVT

The differential diagnosis for UEDVT includes effort thrombosis (also known as Paget-Schroetter syndrome) and cellulitis.

Effort thrombosis usually occurs in young, otherwise healthy individuals and almost exclusively in the axillary and subclavian veins. Our patient’s age and a venous duplex ultrasound ruled out any thrombosis in these locations.

Distinguishing cellulitis from UEDVT based on clinical features can be difficult. In both conditions, the limb is swollen and painful and the skin is warm and erythematous. As a result, each condition is often misdiagnosed as the other.

But there are features that distinguish the 2. In patients with UEDVT, you’re likely to see limb pain and a palpable cord (a hard, thickened palpable vein along the line of the deep veins). On the other hand, patients with cellulitis tend to have more systemic symptoms, such as fever, chills, and swollen lymph nodes, as well as skin breakdown, ulcers, and pus.

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends that the initial evaluation for patients with suspected UEDVT be a combined modality ultrasound (compression with either Doppler or color Doppler) rather than D-dimer or venography.10 Quickly arriving at a proper diagnosis is critical, given that up to one-third of patients with UEDVT will develop a PE.7 Other complications include superior vena cava syndrome, septic thrombophlebitis, thoracic duct obstruction, and brachial plexopathy.11

Treat with anticoagulants for no longer than 3 months

The ACCP also recommends that patients who have UEDVT that isn’t associated with a central venous catheter or with cancer be treated with anticoagulation for no longer than 3 months.10

Our patient was started on enoxaparin and warfarin. After 5 days at our hospital, she was taken off the enoxaparin and discharged home on warfarin 5 mg/d. The swelling completely resolved one week later.

THE TAKEAWAY

Ulnar and radial DVT in a patient with factor V Leiden mutation is a rare condition. UEDVT should be included in the differential diagnosis for cellulitis whenever the diagnosis is uncertain or the patient doesn’t respond to antibiotics. Factor V Leiden mutation appears to be a risk factor in UEDVT and testing for it should be considered.

1. Office of the Surgeon General (US); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (US). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44178/. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2008.

2. Sawyer GA, Hayda R. Upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis following humeral shaft fracture. Orthopedics. 2011;34:141.

3. Leebeek FW, Stadhouders NA, van Stein D, et al. Hypercoagulability states in upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis. Am J Hematol. 2001;67:15-19.

4. Prandoni P, Polistena P, Bernardi E, et al. Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Risk factors, diagnosis, and complications. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:57-62.

5. Ruggeri M, Castaman G, Tosetto A, et al. Low prevalence of thrombophilic coagulation defects in patients with deep vein thrombosis of the upper limbs. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1997;8:191-194.

6. Ornstein DL, Cushman M. Cardiology patient page. Factor V Leiden. Circulation. 2003;107:e94-e97.

7. Héron E, Lozinguez O, Alhenc-Gelas M, et al. Hypercoagulable states in primary upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:382-386.

8. Linnemann B, Meister F, Schwonberg J, et al; MAISTHRO registry. Hereditary and acquired thrombophilia in patients with upper extremity deep-vein thrombosis. Results from the MAISTHRO registry. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:440-446.

9. Monreal M, Lafoz E, Ruiz J, et al. Upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A prospective study. Chest. 1991;99:280-283.

10. Holbrook A, Schulman S, Witt DM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Evidence-based management of anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e152S-e184S.

11. Becker DM, Philbrick JT, Walker FB 4th. Axillary and subclavian venous thrombosis. Prognosis and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1934-1943.

1. Office of the Surgeon General (US); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (US). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44178/. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2008.

2. Sawyer GA, Hayda R. Upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis following humeral shaft fracture. Orthopedics. 2011;34:141.

3. Leebeek FW, Stadhouders NA, van Stein D, et al. Hypercoagulability states in upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis. Am J Hematol. 2001;67:15-19.

4. Prandoni P, Polistena P, Bernardi E, et al. Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Risk factors, diagnosis, and complications. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:57-62.

5. Ruggeri M, Castaman G, Tosetto A, et al. Low prevalence of thrombophilic coagulation defects in patients with deep vein thrombosis of the upper limbs. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1997;8:191-194.

6. Ornstein DL, Cushman M. Cardiology patient page. Factor V Leiden. Circulation. 2003;107:e94-e97.

7. Héron E, Lozinguez O, Alhenc-Gelas M, et al. Hypercoagulable states in primary upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:382-386.

8. Linnemann B, Meister F, Schwonberg J, et al; MAISTHRO registry. Hereditary and acquired thrombophilia in patients with upper extremity deep-vein thrombosis. Results from the MAISTHRO registry. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:440-446.

9. Monreal M, Lafoz E, Ruiz J, et al. Upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A prospective study. Chest. 1991;99:280-283.

10. Holbrook A, Schulman S, Witt DM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Evidence-based management of anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e152S-e184S.

11. Becker DM, Philbrick JT, Walker FB 4th. Axillary and subclavian venous thrombosis. Prognosis and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1934-1943.

Painful rash on face

A 58-year-old man sought care at our clinic for burning in his right eye and a skin eruption on his right forehead and scalp. The pain in both had been getting progressively worse over the previous 10 days. The patient also reported that he had decreased vision in his right eye, as well as a fever, chills, photophobia, and headache. He had a history of psoriasis, which was being treated with adalimumab and methotrexate.

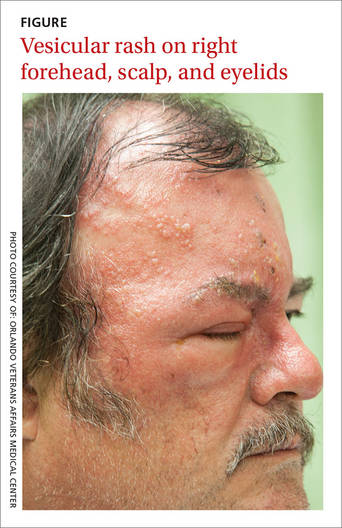

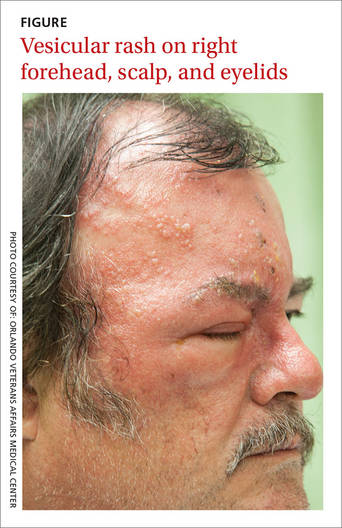

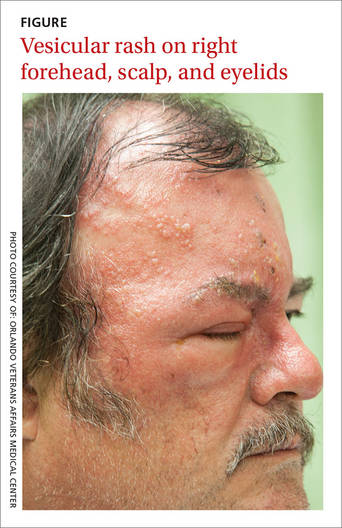

A physical exam revealed vesicles on an erythematous base on his right scalp, forehead, upper and lower eyelids, dorsum of his nose, and cheek (FIGURE). The distribution of the vesicles corresponded to the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

An ophthalmologic exam confirmed the diagnosis of herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), a serious condition that has been linked to reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) within the trigeminal ganglion.1 Primary infection with VZV results in varicella (chickenpox), whereas reactivation of a latent VZV infection within the sensory ganglia is known as herpes zoster.

HZO occurs in 10% to 20% of patients who have herpes zoster.2 The ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve is most frequently involved, and as many as 72% of patients experience direct ocular involvement.1

The acute syndrome begins with headache, fever, and unilateral pain in the affected eye, followed by the onset of a vesicular eruption along the trigeminal dermatome, hyperemic conjunctivitis, and episcleritis.3,4 Almost two-thirds of HZO patients develop corneal involvement.5

Rule out other types of vesicular eruptions

Impetigo, herpes simplex virus-type 1 (HSV-1), atopic dermatitis, acute contact dermatitis, and chickenpox should be included in the differential diagnosis of HZO.

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection. The lesions begin as papules and then progress to vesicles that enlarge and rapidly break down to form adherent crusts with a characteristic golden appearance. These lesions usually affect the face and extremities.

HSV-1 is characterized by multiple vesicular lesions superimposed on an erythematous base on the skin or mucous membranes of the mouth or lips.

Atopic dermatitis is characterized by pruritus, erythema, scale, and crusting. The flexural areas (neck, antecubital fossae, and popliteal fossae) are most commonly affected.6 Other common sites include the face, wrists, and forearms.

Acute contact dermatitis is an acute vesicular eruption accompanied by pruritus and erythema. The vesicles may be distributed in a characteristic linear pattern when a portion of an allergen (such as poison ivy) has made contact with the skin or when the patient has scratched the skin.

Chickenpox is a primary infection with VZV. The clinical manifestations include a prodrome of fever, malaise, or pharyngitis, followed by the development of a generalized vesicular rash. Although the appearance of the chickenpox rash is similar to that of HZO, herpes zoster is usually localized to a dermatome.

Diagnostic testing is rarely indicated

A history of VZV infection and the characteristic rash are usually adequate to make a diagnosis of HZO. Of note: vesicular lesions on the nose—known as Hutchinson’s sign—are associated with a high risk of HZO.7

If you suspect HZO, your patient will need an ophthalmologic exam, including an external inspection, testing of visual acuity, extraocular movements, and pupillary response, and various other exams (fundoscopy, anterior chamber slit lamp, and corneal).

A viral culture, direct immunofluorescence assay, Tzanck smear, or polymerase chain reaction may be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Treat with antivirals and steroid eye drops

An early diagnosis of HZO is critical to prevent progressive corneal involvement and potential loss of vision. The standard management is to initiate antiviral therapy with oral acyclovir (800 mg 5 times per day or 10 mg/kg intravenously 3 times per day), oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times per day), or oral famciclovir (500 mg 3 times per day), and to use adjunctive steroid eye drops that are prescribed by an ophthalmologist to reduce the inflammatory response.8

In otherwise healthy individuals in whom HZO causes minimal ocular symptoms, outpatient treatment with 7 to 10 days of antiviral medications is recommended. Immunodeficient patients and those taking immunosuppressive agents should be admitted to the hospital so they can receive intravenous antiviral medications.

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and underwent an ophthalmologic consultation and exam, which showed right erythematous conjunctiva and punctate corneal erosions. The iris, anterior vitreous, macula, and lens all appeared normal. He was given acyclovir 10 mg/kg intravenously and steroid ophthalmic drops, and his pain was controlled with oral oxycodone/acetaminophen (10 mg/325 mg) and ibuprofen 400 mg. Our patient continued to improve and was discharged on oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times per day and steroid eye drops with outpatient Ophthalmology follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mahmoud Farhoud, MD, Orlando Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 13800 Veterans Way, Orlando, FL 32827; [email protected].

1. Pavan-Langston D. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Neurology. 1995;45:S50-S51.

2. Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:S3-S12.

3. Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186: S91-S98.

4. Liesegang TJ. Diagnosis and therapy of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1216-1229.

5. Kaufman SC. Anterior segment complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:S24-S32.

6. Williams HC. Clinical practice. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2314-2324.

7. Tomkinson A, Roblin DG, Brown MJ. Hutchinson’s sign and its importance in rhinology. Rhinology. 1995;33:180-182.

8. Cohen EJ, Kessler J. Persistent dilemmas in zoster eye disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015.

A 58-year-old man sought care at our clinic for burning in his right eye and a skin eruption on his right forehead and scalp. The pain in both had been getting progressively worse over the previous 10 days. The patient also reported that he had decreased vision in his right eye, as well as a fever, chills, photophobia, and headache. He had a history of psoriasis, which was being treated with adalimumab and methotrexate.

A physical exam revealed vesicles on an erythematous base on his right scalp, forehead, upper and lower eyelids, dorsum of his nose, and cheek (FIGURE). The distribution of the vesicles corresponded to the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

An ophthalmologic exam confirmed the diagnosis of herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), a serious condition that has been linked to reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) within the trigeminal ganglion.1 Primary infection with VZV results in varicella (chickenpox), whereas reactivation of a latent VZV infection within the sensory ganglia is known as herpes zoster.

HZO occurs in 10% to 20% of patients who have herpes zoster.2 The ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve is most frequently involved, and as many as 72% of patients experience direct ocular involvement.1

The acute syndrome begins with headache, fever, and unilateral pain in the affected eye, followed by the onset of a vesicular eruption along the trigeminal dermatome, hyperemic conjunctivitis, and episcleritis.3,4 Almost two-thirds of HZO patients develop corneal involvement.5

Rule out other types of vesicular eruptions

Impetigo, herpes simplex virus-type 1 (HSV-1), atopic dermatitis, acute contact dermatitis, and chickenpox should be included in the differential diagnosis of HZO.

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection. The lesions begin as papules and then progress to vesicles that enlarge and rapidly break down to form adherent crusts with a characteristic golden appearance. These lesions usually affect the face and extremities.

HSV-1 is characterized by multiple vesicular lesions superimposed on an erythematous base on the skin or mucous membranes of the mouth or lips.

Atopic dermatitis is characterized by pruritus, erythema, scale, and crusting. The flexural areas (neck, antecubital fossae, and popliteal fossae) are most commonly affected.6 Other common sites include the face, wrists, and forearms.

Acute contact dermatitis is an acute vesicular eruption accompanied by pruritus and erythema. The vesicles may be distributed in a characteristic linear pattern when a portion of an allergen (such as poison ivy) has made contact with the skin or when the patient has scratched the skin.

Chickenpox is a primary infection with VZV. The clinical manifestations include a prodrome of fever, malaise, or pharyngitis, followed by the development of a generalized vesicular rash. Although the appearance of the chickenpox rash is similar to that of HZO, herpes zoster is usually localized to a dermatome.

Diagnostic testing is rarely indicated

A history of VZV infection and the characteristic rash are usually adequate to make a diagnosis of HZO. Of note: vesicular lesions on the nose—known as Hutchinson’s sign—are associated with a high risk of HZO.7

If you suspect HZO, your patient will need an ophthalmologic exam, including an external inspection, testing of visual acuity, extraocular movements, and pupillary response, and various other exams (fundoscopy, anterior chamber slit lamp, and corneal).

A viral culture, direct immunofluorescence assay, Tzanck smear, or polymerase chain reaction may be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Treat with antivirals and steroid eye drops

An early diagnosis of HZO is critical to prevent progressive corneal involvement and potential loss of vision. The standard management is to initiate antiviral therapy with oral acyclovir (800 mg 5 times per day or 10 mg/kg intravenously 3 times per day), oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times per day), or oral famciclovir (500 mg 3 times per day), and to use adjunctive steroid eye drops that are prescribed by an ophthalmologist to reduce the inflammatory response.8

In otherwise healthy individuals in whom HZO causes minimal ocular symptoms, outpatient treatment with 7 to 10 days of antiviral medications is recommended. Immunodeficient patients and those taking immunosuppressive agents should be admitted to the hospital so they can receive intravenous antiviral medications.

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and underwent an ophthalmologic consultation and exam, which showed right erythematous conjunctiva and punctate corneal erosions. The iris, anterior vitreous, macula, and lens all appeared normal. He was given acyclovir 10 mg/kg intravenously and steroid ophthalmic drops, and his pain was controlled with oral oxycodone/acetaminophen (10 mg/325 mg) and ibuprofen 400 mg. Our patient continued to improve and was discharged on oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times per day and steroid eye drops with outpatient Ophthalmology follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mahmoud Farhoud, MD, Orlando Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 13800 Veterans Way, Orlando, FL 32827; [email protected].

A 58-year-old man sought care at our clinic for burning in his right eye and a skin eruption on his right forehead and scalp. The pain in both had been getting progressively worse over the previous 10 days. The patient also reported that he had decreased vision in his right eye, as well as a fever, chills, photophobia, and headache. He had a history of psoriasis, which was being treated with adalimumab and methotrexate.

A physical exam revealed vesicles on an erythematous base on his right scalp, forehead, upper and lower eyelids, dorsum of his nose, and cheek (FIGURE). The distribution of the vesicles corresponded to the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

An ophthalmologic exam confirmed the diagnosis of herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), a serious condition that has been linked to reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) within the trigeminal ganglion.1 Primary infection with VZV results in varicella (chickenpox), whereas reactivation of a latent VZV infection within the sensory ganglia is known as herpes zoster.

HZO occurs in 10% to 20% of patients who have herpes zoster.2 The ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve is most frequently involved, and as many as 72% of patients experience direct ocular involvement.1

The acute syndrome begins with headache, fever, and unilateral pain in the affected eye, followed by the onset of a vesicular eruption along the trigeminal dermatome, hyperemic conjunctivitis, and episcleritis.3,4 Almost two-thirds of HZO patients develop corneal involvement.5

Rule out other types of vesicular eruptions

Impetigo, herpes simplex virus-type 1 (HSV-1), atopic dermatitis, acute contact dermatitis, and chickenpox should be included in the differential diagnosis of HZO.

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection. The lesions begin as papules and then progress to vesicles that enlarge and rapidly break down to form adherent crusts with a characteristic golden appearance. These lesions usually affect the face and extremities.

HSV-1 is characterized by multiple vesicular lesions superimposed on an erythematous base on the skin or mucous membranes of the mouth or lips.

Atopic dermatitis is characterized by pruritus, erythema, scale, and crusting. The flexural areas (neck, antecubital fossae, and popliteal fossae) are most commonly affected.6 Other common sites include the face, wrists, and forearms.

Acute contact dermatitis is an acute vesicular eruption accompanied by pruritus and erythema. The vesicles may be distributed in a characteristic linear pattern when a portion of an allergen (such as poison ivy) has made contact with the skin or when the patient has scratched the skin.

Chickenpox is a primary infection with VZV. The clinical manifestations include a prodrome of fever, malaise, or pharyngitis, followed by the development of a generalized vesicular rash. Although the appearance of the chickenpox rash is similar to that of HZO, herpes zoster is usually localized to a dermatome.

Diagnostic testing is rarely indicated

A history of VZV infection and the characteristic rash are usually adequate to make a diagnosis of HZO. Of note: vesicular lesions on the nose—known as Hutchinson’s sign—are associated with a high risk of HZO.7

If you suspect HZO, your patient will need an ophthalmologic exam, including an external inspection, testing of visual acuity, extraocular movements, and pupillary response, and various other exams (fundoscopy, anterior chamber slit lamp, and corneal).

A viral culture, direct immunofluorescence assay, Tzanck smear, or polymerase chain reaction may be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Treat with antivirals and steroid eye drops

An early diagnosis of HZO is critical to prevent progressive corneal involvement and potential loss of vision. The standard management is to initiate antiviral therapy with oral acyclovir (800 mg 5 times per day or 10 mg/kg intravenously 3 times per day), oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times per day), or oral famciclovir (500 mg 3 times per day), and to use adjunctive steroid eye drops that are prescribed by an ophthalmologist to reduce the inflammatory response.8

In otherwise healthy individuals in whom HZO causes minimal ocular symptoms, outpatient treatment with 7 to 10 days of antiviral medications is recommended. Immunodeficient patients and those taking immunosuppressive agents should be admitted to the hospital so they can receive intravenous antiviral medications.

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and underwent an ophthalmologic consultation and exam, which showed right erythematous conjunctiva and punctate corneal erosions. The iris, anterior vitreous, macula, and lens all appeared normal. He was given acyclovir 10 mg/kg intravenously and steroid ophthalmic drops, and his pain was controlled with oral oxycodone/acetaminophen (10 mg/325 mg) and ibuprofen 400 mg. Our patient continued to improve and was discharged on oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times per day and steroid eye drops with outpatient Ophthalmology follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mahmoud Farhoud, MD, Orlando Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 13800 Veterans Way, Orlando, FL 32827; [email protected].

1. Pavan-Langston D. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Neurology. 1995;45:S50-S51.

2. Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:S3-S12.

3. Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186: S91-S98.

4. Liesegang TJ. Diagnosis and therapy of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1216-1229.

5. Kaufman SC. Anterior segment complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:S24-S32.

6. Williams HC. Clinical practice. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2314-2324.

7. Tomkinson A, Roblin DG, Brown MJ. Hutchinson’s sign and its importance in rhinology. Rhinology. 1995;33:180-182.

8. Cohen EJ, Kessler J. Persistent dilemmas in zoster eye disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015.

1. Pavan-Langston D. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Neurology. 1995;45:S50-S51.

2. Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:S3-S12.

3. Gnann JW Jr. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186: S91-S98.

4. Liesegang TJ. Diagnosis and therapy of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1216-1229.

5. Kaufman SC. Anterior segment complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:S24-S32.

6. Williams HC. Clinical practice. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2314-2324.

7. Tomkinson A, Roblin DG, Brown MJ. Hutchinson’s sign and its importance in rhinology. Rhinology. 1995;33:180-182.

8. Cohen EJ, Kessler J. Persistent dilemmas in zoster eye disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015.