User login

Painful lumps on back

The FP recognized that this patient was suffering from the follicular occlusion triad, which includes acne conglobata on the back, hidradenitis suppurativa, and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp. Some adult males (and occasionally females) have acne conglobata that takes the form of open comedones and cystic nodules that are found on the chest, shoulders, back, buttocks, and face. However, in some patients (like this one), acne conglobata is part of a follicular occlusion triad including hidradenitis suppurativa and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp.

Hidradenitis suppurativa causes purulent nodules, cysts, and sinus tracts in the axilla, groin, buttocks, and the breast area of women. Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp is a form of scarring alopecia that creates sinus tracts filled with pus on the scalp.

Treatment choices available for the whole follicular occlusion triad include oral isotretinoin (often known by the discontinued brand name Accutane), acitretin, multiple oral antibiotics, and some of the same biologic agents used to treat psoriasis. Unfortunately, this disease is hard to manage and impossible to cure.

Fortunately for this patient, the hidradenitis suppurativa and dissecting cellulitis weren’t active when he sought care. The patient found the cysts on his back to be tender and painful, but was not worried about the blackheads (open comedones). The FP offered to excise the tender cysts on his back and referred the patient to a skin specialist for the follicular occlusion triad. The patient returned to the FP’s office for 2 cyst excisions and scheduled an appointment with a skin specialist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:651-658.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that this patient was suffering from the follicular occlusion triad, which includes acne conglobata on the back, hidradenitis suppurativa, and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp. Some adult males (and occasionally females) have acne conglobata that takes the form of open comedones and cystic nodules that are found on the chest, shoulders, back, buttocks, and face. However, in some patients (like this one), acne conglobata is part of a follicular occlusion triad including hidradenitis suppurativa and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp.

Hidradenitis suppurativa causes purulent nodules, cysts, and sinus tracts in the axilla, groin, buttocks, and the breast area of women. Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp is a form of scarring alopecia that creates sinus tracts filled with pus on the scalp.

Treatment choices available for the whole follicular occlusion triad include oral isotretinoin (often known by the discontinued brand name Accutane), acitretin, multiple oral antibiotics, and some of the same biologic agents used to treat psoriasis. Unfortunately, this disease is hard to manage and impossible to cure.

Fortunately for this patient, the hidradenitis suppurativa and dissecting cellulitis weren’t active when he sought care. The patient found the cysts on his back to be tender and painful, but was not worried about the blackheads (open comedones). The FP offered to excise the tender cysts on his back and referred the patient to a skin specialist for the follicular occlusion triad. The patient returned to the FP’s office for 2 cyst excisions and scheduled an appointment with a skin specialist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:651-658.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that this patient was suffering from the follicular occlusion triad, which includes acne conglobata on the back, hidradenitis suppurativa, and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp. Some adult males (and occasionally females) have acne conglobata that takes the form of open comedones and cystic nodules that are found on the chest, shoulders, back, buttocks, and face. However, in some patients (like this one), acne conglobata is part of a follicular occlusion triad including hidradenitis suppurativa and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp.

Hidradenitis suppurativa causes purulent nodules, cysts, and sinus tracts in the axilla, groin, buttocks, and the breast area of women. Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp is a form of scarring alopecia that creates sinus tracts filled with pus on the scalp.

Treatment choices available for the whole follicular occlusion triad include oral isotretinoin (often known by the discontinued brand name Accutane), acitretin, multiple oral antibiotics, and some of the same biologic agents used to treat psoriasis. Unfortunately, this disease is hard to manage and impossible to cure.

Fortunately for this patient, the hidradenitis suppurativa and dissecting cellulitis weren’t active when he sought care. The patient found the cysts on his back to be tender and painful, but was not worried about the blackheads (open comedones). The FP offered to excise the tender cysts on his back and referred the patient to a skin specialist for the follicular occlusion triad. The patient returned to the FP’s office for 2 cyst excisions and scheduled an appointment with a skin specialist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:651-658.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Severe rash on face

Based on the patient’s severe cystic acne with sinus tracts between the cysts, the FP diagnosed acne conglobata in this patient. Acne conglobata is an uncommon and unusually severe form of acne characterized by multiple comedones, cysts, sinus tracts, and abscesses. The inflammatory lesions and scars can lead to significant disfigurement. Sinus tracts can form with multiple openings that drain foul-smelling purulent material.

The FP recognized that this patient needed oral isotretinoin (which he didn’t prescribe), so he referred the adolescent to a local skin specialist. Isotretinoin (once known by the discontinued brand name Accutane) is the most powerful treatment for all forms of severe acne. It is especially useful for cystic and scarring acne that has not responded to other therapies, and is dosed at approximately 1 mg/kg per day for 5 to 6 months. Women of childbearing age must use 2 forms of contraception or strict abstinence, as it is a potent teratogen. Isotretinoin should be avoided in patients with a strong history of depression.

The US Food and Drug Administration requires that individuals prescribing, dispensing, or taking isotretinoin register with the iPLEDGE system (www.ipledgeprogram.com). Since the start of this program, the percentage of FPs prescribing isotretinoin has significantly decreased. However, FPs with an interest in dermatology are not prohibited from prescribing it.

Prior to the patient’s specialty appointment, the FP started the patient on oral doxycycline 100 mg BID. When the FP with special training in dermatology saw the patient, he initially prescribed oral prednisone 40 mg/d and changed the antibiotic to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (which is more potent and reserved for severe forms of acne). Within 2 weeks, the acne was improving and the patient was willing to start school.

Oral isotretinoin was initiated after one month while continuing the prednisone for another month. The prednisone served as a potent anti-inflammatory agent and was needed to prevent worsening of the acne at the time of isotretinoin initiation. The acne conglobata cleared with minimal scarring after 5 to 6 months of isotretinoin therapy.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:651-658.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the patient’s severe cystic acne with sinus tracts between the cysts, the FP diagnosed acne conglobata in this patient. Acne conglobata is an uncommon and unusually severe form of acne characterized by multiple comedones, cysts, sinus tracts, and abscesses. The inflammatory lesions and scars can lead to significant disfigurement. Sinus tracts can form with multiple openings that drain foul-smelling purulent material.

The FP recognized that this patient needed oral isotretinoin (which he didn’t prescribe), so he referred the adolescent to a local skin specialist. Isotretinoin (once known by the discontinued brand name Accutane) is the most powerful treatment for all forms of severe acne. It is especially useful for cystic and scarring acne that has not responded to other therapies, and is dosed at approximately 1 mg/kg per day for 5 to 6 months. Women of childbearing age must use 2 forms of contraception or strict abstinence, as it is a potent teratogen. Isotretinoin should be avoided in patients with a strong history of depression.

The US Food and Drug Administration requires that individuals prescribing, dispensing, or taking isotretinoin register with the iPLEDGE system (www.ipledgeprogram.com). Since the start of this program, the percentage of FPs prescribing isotretinoin has significantly decreased. However, FPs with an interest in dermatology are not prohibited from prescribing it.

Prior to the patient’s specialty appointment, the FP started the patient on oral doxycycline 100 mg BID. When the FP with special training in dermatology saw the patient, he initially prescribed oral prednisone 40 mg/d and changed the antibiotic to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (which is more potent and reserved for severe forms of acne). Within 2 weeks, the acne was improving and the patient was willing to start school.

Oral isotretinoin was initiated after one month while continuing the prednisone for another month. The prednisone served as a potent anti-inflammatory agent and was needed to prevent worsening of the acne at the time of isotretinoin initiation. The acne conglobata cleared with minimal scarring after 5 to 6 months of isotretinoin therapy.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:651-658.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the patient’s severe cystic acne with sinus tracts between the cysts, the FP diagnosed acne conglobata in this patient. Acne conglobata is an uncommon and unusually severe form of acne characterized by multiple comedones, cysts, sinus tracts, and abscesses. The inflammatory lesions and scars can lead to significant disfigurement. Sinus tracts can form with multiple openings that drain foul-smelling purulent material.

The FP recognized that this patient needed oral isotretinoin (which he didn’t prescribe), so he referred the adolescent to a local skin specialist. Isotretinoin (once known by the discontinued brand name Accutane) is the most powerful treatment for all forms of severe acne. It is especially useful for cystic and scarring acne that has not responded to other therapies, and is dosed at approximately 1 mg/kg per day for 5 to 6 months. Women of childbearing age must use 2 forms of contraception or strict abstinence, as it is a potent teratogen. Isotretinoin should be avoided in patients with a strong history of depression.

The US Food and Drug Administration requires that individuals prescribing, dispensing, or taking isotretinoin register with the iPLEDGE system (www.ipledgeprogram.com). Since the start of this program, the percentage of FPs prescribing isotretinoin has significantly decreased. However, FPs with an interest in dermatology are not prohibited from prescribing it.

Prior to the patient’s specialty appointment, the FP started the patient on oral doxycycline 100 mg BID. When the FP with special training in dermatology saw the patient, he initially prescribed oral prednisone 40 mg/d and changed the antibiotic to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (which is more potent and reserved for severe forms of acne). Within 2 weeks, the acne was improving and the patient was willing to start school.

Oral isotretinoin was initiated after one month while continuing the prednisone for another month. The prednisone served as a potent anti-inflammatory agent and was needed to prevent worsening of the acne at the time of isotretinoin initiation. The acne conglobata cleared with minimal scarring after 5 to 6 months of isotretinoin therapy.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:651-658.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Bad case of diaper rash

The FP diagnosed Candida diaper dermatitis in this patient based on the erythema, white scale, satellite lesions (pustules or papules beyond the rash border), and involvement of the skin folds. The FP also inspected the oropharynx for signs of thrush, but no thrush was detected.

Diaper dermatitis often has a multifactorial etiology. The main cause is irritation of the skin as a result of prolonged contact with moisture, such as feces and urine. Irritant diaper dermatitis is a combination of intertrigo and miliaria (heat rash that occurs when eccrine glands become obstructed from excessive hydration). It is a noninfectious, nonallergic, and often asymptomatic contact dermatitis. Within 3 days, 45% to 75% of diaper rashes are colonized with Candida albicans of fecal origin.

Treatment begins with frequent diaper changes (as soon as the infant is wet or soiled and at least every 3-4 hours), and frequent gentle cleaning of the affected area with lukewarm tap water instead of commercial wipes that contain alcohol. A squeeze bottle with lukewarm water can be used to avoid rubbing the delicate skin. Superabsorbent disposable diapers that pull moisture away from the skin are also helpful.

In addition, barrier preparations, including zinc oxide paste, petroleum jelly, and vitamin A and D ointment are helpful after each diaper change.Pastes are better than ointments, which, in turn, are better than creams or lotions. Caregivers should avoid products with fragrances or preservatives to minimize the chance of an allergic response.

Barrier preparations should be used on top of other indicated therapies. Combination antifungal-steroid agents that contain steroids stronger than hydrocortisone (eg, clotrimazole/betamethasone) should be avoided. Potent topical steroids can cause striae and skin erosions, hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression, and Cushing syndrome.

In this case, the FP recommended the treatment steps outlined above, as well as topical nonprescription antifungal creams (eg, clotrimazole and miconazole) after every diaper change until the rash resolved.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Malit B, Taylor J. Diaper rash and perianal dermatitis. Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:646-650.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed Candida diaper dermatitis in this patient based on the erythema, white scale, satellite lesions (pustules or papules beyond the rash border), and involvement of the skin folds. The FP also inspected the oropharynx for signs of thrush, but no thrush was detected.

Diaper dermatitis often has a multifactorial etiology. The main cause is irritation of the skin as a result of prolonged contact with moisture, such as feces and urine. Irritant diaper dermatitis is a combination of intertrigo and miliaria (heat rash that occurs when eccrine glands become obstructed from excessive hydration). It is a noninfectious, nonallergic, and often asymptomatic contact dermatitis. Within 3 days, 45% to 75% of diaper rashes are colonized with Candida albicans of fecal origin.

Treatment begins with frequent diaper changes (as soon as the infant is wet or soiled and at least every 3-4 hours), and frequent gentle cleaning of the affected area with lukewarm tap water instead of commercial wipes that contain alcohol. A squeeze bottle with lukewarm water can be used to avoid rubbing the delicate skin. Superabsorbent disposable diapers that pull moisture away from the skin are also helpful.

In addition, barrier preparations, including zinc oxide paste, petroleum jelly, and vitamin A and D ointment are helpful after each diaper change.Pastes are better than ointments, which, in turn, are better than creams or lotions. Caregivers should avoid products with fragrances or preservatives to minimize the chance of an allergic response.

Barrier preparations should be used on top of other indicated therapies. Combination antifungal-steroid agents that contain steroids stronger than hydrocortisone (eg, clotrimazole/betamethasone) should be avoided. Potent topical steroids can cause striae and skin erosions, hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression, and Cushing syndrome.

In this case, the FP recommended the treatment steps outlined above, as well as topical nonprescription antifungal creams (eg, clotrimazole and miconazole) after every diaper change until the rash resolved.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Malit B, Taylor J. Diaper rash and perianal dermatitis. Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:646-650.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed Candida diaper dermatitis in this patient based on the erythema, white scale, satellite lesions (pustules or papules beyond the rash border), and involvement of the skin folds. The FP also inspected the oropharynx for signs of thrush, but no thrush was detected.

Diaper dermatitis often has a multifactorial etiology. The main cause is irritation of the skin as a result of prolonged contact with moisture, such as feces and urine. Irritant diaper dermatitis is a combination of intertrigo and miliaria (heat rash that occurs when eccrine glands become obstructed from excessive hydration). It is a noninfectious, nonallergic, and often asymptomatic contact dermatitis. Within 3 days, 45% to 75% of diaper rashes are colonized with Candida albicans of fecal origin.

Treatment begins with frequent diaper changes (as soon as the infant is wet or soiled and at least every 3-4 hours), and frequent gentle cleaning of the affected area with lukewarm tap water instead of commercial wipes that contain alcohol. A squeeze bottle with lukewarm water can be used to avoid rubbing the delicate skin. Superabsorbent disposable diapers that pull moisture away from the skin are also helpful.

In addition, barrier preparations, including zinc oxide paste, petroleum jelly, and vitamin A and D ointment are helpful after each diaper change.Pastes are better than ointments, which, in turn, are better than creams or lotions. Caregivers should avoid products with fragrances or preservatives to minimize the chance of an allergic response.

Barrier preparations should be used on top of other indicated therapies. Combination antifungal-steroid agents that contain steroids stronger than hydrocortisone (eg, clotrimazole/betamethasone) should be avoided. Potent topical steroids can cause striae and skin erosions, hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression, and Cushing syndrome.

In this case, the FP recommended the treatment steps outlined above, as well as topical nonprescription antifungal creams (eg, clotrimazole and miconazole) after every diaper change until the rash resolved.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Malit B, Taylor J. Diaper rash and perianal dermatitis. Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:646-650.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Pustules on newborn’s wrists

The FP diagnosed transient neonatal pustular melanosis in this young patient. To confirm his diagnosis, he sent a photograph from his smartphone to a dermatology colleague, who agreed with the diagnosis.

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis is a disease of newborns with an equal male-to-female ratio. It is seen in 4.4% of black infants and 0.6% of white infants. There is an early, spontaneous remission. This condition is characterized by the presence of 2- to 3-mm macules and pustules on a non-erythematous base at birth. The lesions are thought to evolve prenatally; they subsequently rupture a day or two after birth. They heal as hyperpigmented macules that fade when the child is 3 months of age. Sometimes, the only evidence of the disease is the presence of small, brown macules with a rim of scale at birth.

The FP reassured the parents that the condition was benign and would resolve spontaneously with eventual normalization of any hyperpigmented macules. The child was sent home without any specific treatment.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Shedd A, Usatine R, Chumley H. Pustular diseases of childhood. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:642-645.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed transient neonatal pustular melanosis in this young patient. To confirm his diagnosis, he sent a photograph from his smartphone to a dermatology colleague, who agreed with the diagnosis.

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis is a disease of newborns with an equal male-to-female ratio. It is seen in 4.4% of black infants and 0.6% of white infants. There is an early, spontaneous remission. This condition is characterized by the presence of 2- to 3-mm macules and pustules on a non-erythematous base at birth. The lesions are thought to evolve prenatally; they subsequently rupture a day or two after birth. They heal as hyperpigmented macules that fade when the child is 3 months of age. Sometimes, the only evidence of the disease is the presence of small, brown macules with a rim of scale at birth.

The FP reassured the parents that the condition was benign and would resolve spontaneously with eventual normalization of any hyperpigmented macules. The child was sent home without any specific treatment.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Shedd A, Usatine R, Chumley H. Pustular diseases of childhood. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:642-645.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed transient neonatal pustular melanosis in this young patient. To confirm his diagnosis, he sent a photograph from his smartphone to a dermatology colleague, who agreed with the diagnosis.

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis is a disease of newborns with an equal male-to-female ratio. It is seen in 4.4% of black infants and 0.6% of white infants. There is an early, spontaneous remission. This condition is characterized by the presence of 2- to 3-mm macules and pustules on a non-erythematous base at birth. The lesions are thought to evolve prenatally; they subsequently rupture a day or two after birth. They heal as hyperpigmented macules that fade when the child is 3 months of age. Sometimes, the only evidence of the disease is the presence of small, brown macules with a rim of scale at birth.

The FP reassured the parents that the condition was benign and would resolve spontaneously with eventual normalization of any hyperpigmented macules. The child was sent home without any specific treatment.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Shedd A, Usatine R, Chumley H. Pustular diseases of childhood. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:642-645.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Recurrent vesicular rash over the sacrum

A 35-year-old woman sought care at our dermatology clinic with the self-diagnosis of “recurrent shingles,” noting that she’d had a rash over her sacrum on and off for the past 10 years. She said that the tender blisters typically appeared in this area 3 to 4 times per year (FIGURE) and that their onset was occasionally associated with stress. The rash tended to resolve—without treatment—within 5 to 7 days. The patient had no other medical problems or symptoms. Physical examination revealed 3 groups of vesicular lesions, each on an erythematous base, located bilaterally over the gluteal cleft.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Recurrent herpes simplex virus-2

While the presentation of herpes zoster (shingles) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) is similar—grouped vesicles on an erythematous base—recurrent shingles is rare in immunocompetent patients. Also, the herpes zoster rash is generally unilateral and is not common on the buttocks.1,2

Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) generally occurs around the mouth. Herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) is generally a genital rash. (Our patient was not aware that she’d had a genital primary HSV-2 infection.) That said, non-genital recurrences in the sacral region and lower extremities occur in up to 60% of patients whose primary genital HSV-2 infection also involved non-genital sites.3

HSV-2 infects an estimated 5% to 25% of adults in western nations.4 In 2012, approximately 417 million people ages 15 to 49 were living with HSV-2 worldwide, including 19 million who were newly infected.5

A dormant infection that is reactivated. Following a genital primary infection, HSV-2 lies dormant in the sacral nerve root ganglia, which innervate both the genitals and sacrum. Reactivation can thus result in recurrences anywhere over the sacral dermatome.6 The sacral area is the most common non-genital site for recurrent HSV-2.3 Reactivation of HSV-2 is more common and more severe in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection.7

Neurologic complications in some patients with genital herpes (eg, sacral radiculopathy, hyperesthesia) reinforce the hypothesis that genital herpes can infect ganglia that are also associated with sacral nerves.8 Contrary to popular belief, sacral HSV-2 is not commonly contracted from toilet seats.

How to differentiate herpes simplex from herpes zoster

As noted earlier, the location of the vesicles and unilateral nature of herpes zoster are useful in differentiating HSV from herpes zoster.

Tzanck preparation can’t be used to differentiate HSV and herpes zoster because it will demonstrate multinucleated giant cells in both cases. When necessary, viral culture can be used to distinguish the 2 conditions, although HSV often takes 24 to 72 hours to grow and herpes zoster may take up to 2 weeks.9,10 Increasingly, polymerase chain reaction is being used for this purpose.

Antivirals are used for both genital and non-genital recurrences

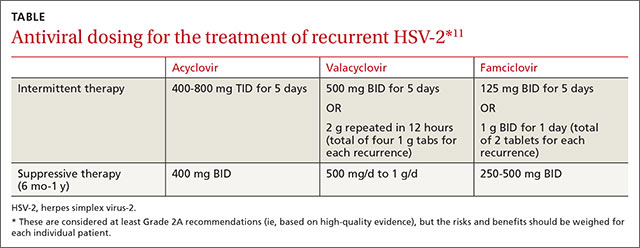

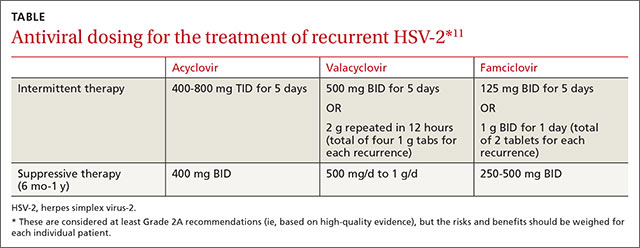

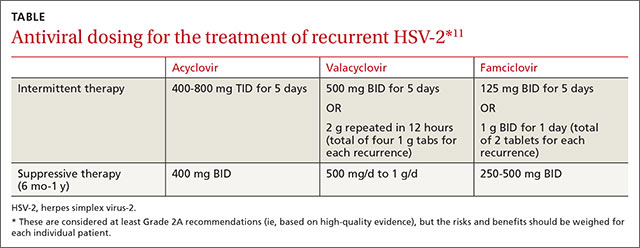

The mainstay of treatment for HSV is antiviral therapy with acyclovir. Famciclovir and valacyclovir can be used as well (TABLE).11 These antivirals inhibit viral DNA replication, shorten duration of symptoms, increase lesion healing, and decrease viral shedding time.12 They are generally safe; the main adverse effects of oral therapy are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

In general, non-genital recurrences of HSV are treated the same as genital recurrences.13 Dosing during prodromal symptoms, or at the first sign of a recurrence is recommended for maximum efficacy.13 Suppressive therapy can be effective in patients who experience frequent recurrences and is generally recommended for 6 months to a year or longer.

Patients should also be warned that because of increased genital viral shedding during sacral recurrences, they should avoid sexual contact during outbreaks.14

Our patient began taking oral valacyclovir 1 g daily and had no recurrences over the next year.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, et al. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1605-1609.

2. Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

3. Benedetti JK, Zeh J, Selke S, et al. Frequency and reactivation of nongenital lesions among patients with genital herpes simplex virus. Am J Med. 1995;98:237-242.

4. Smith JS, Robinson NJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. J Infect Dis. 2002;186 Suppl 1:S3-S28.

5. Looker KJ, Magaret AS, Turner KME, et al. Global estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type 2 infections in 2012. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e114989.

6. Corey L, Adams HG, Brown ZA, et al. Genital herpes simplex virus infections: clinical manifestations, course, and complications. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:958-972.

7. Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

8. Ooi C, Zawar V. Hyperaesthesia following genital herpes: a case report. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:903595.

9. Domeika M, Bashmakova M, Savicheva A, et al; Eastern European Network for Sexual and Reproductive Health (EE SRH Network). Guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of genital herpes in eastern European countries. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(44). pii:19703.

10. Solomon AR, Rasmussen JE, Weiss JS. A comparison of the Tzanck smear and viral isolation in varicella and herpes zoster. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:282-285.

11. Cernik C, Gallina K, Brodell RT. The treatment of herpes simplex infections: an evidence-based review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1137-1144.

12. Goldberg LH, Kaufman R, Conant MA, et al. Oral acyclovir for episodic treatment of recurrent genital herpes. Efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:256-264.

13. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s color atlas and synopsis of clinical dermatology. 5th ed. Chicago, IL: McGraw-Hill:2005;800-803.

14. Kerkering K, Gardella C, Selke S, et al. Isolation of herpes simplex virus from the genital tract during symptomatic recurrence on the buttocks. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:947-952.

A 35-year-old woman sought care at our dermatology clinic with the self-diagnosis of “recurrent shingles,” noting that she’d had a rash over her sacrum on and off for the past 10 years. She said that the tender blisters typically appeared in this area 3 to 4 times per year (FIGURE) and that their onset was occasionally associated with stress. The rash tended to resolve—without treatment—within 5 to 7 days. The patient had no other medical problems or symptoms. Physical examination revealed 3 groups of vesicular lesions, each on an erythematous base, located bilaterally over the gluteal cleft.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Recurrent herpes simplex virus-2

While the presentation of herpes zoster (shingles) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) is similar—grouped vesicles on an erythematous base—recurrent shingles is rare in immunocompetent patients. Also, the herpes zoster rash is generally unilateral and is not common on the buttocks.1,2

Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) generally occurs around the mouth. Herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) is generally a genital rash. (Our patient was not aware that she’d had a genital primary HSV-2 infection.) That said, non-genital recurrences in the sacral region and lower extremities occur in up to 60% of patients whose primary genital HSV-2 infection also involved non-genital sites.3

HSV-2 infects an estimated 5% to 25% of adults in western nations.4 In 2012, approximately 417 million people ages 15 to 49 were living with HSV-2 worldwide, including 19 million who were newly infected.5

A dormant infection that is reactivated. Following a genital primary infection, HSV-2 lies dormant in the sacral nerve root ganglia, which innervate both the genitals and sacrum. Reactivation can thus result in recurrences anywhere over the sacral dermatome.6 The sacral area is the most common non-genital site for recurrent HSV-2.3 Reactivation of HSV-2 is more common and more severe in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection.7

Neurologic complications in some patients with genital herpes (eg, sacral radiculopathy, hyperesthesia) reinforce the hypothesis that genital herpes can infect ganglia that are also associated with sacral nerves.8 Contrary to popular belief, sacral HSV-2 is not commonly contracted from toilet seats.

How to differentiate herpes simplex from herpes zoster

As noted earlier, the location of the vesicles and unilateral nature of herpes zoster are useful in differentiating HSV from herpes zoster.

Tzanck preparation can’t be used to differentiate HSV and herpes zoster because it will demonstrate multinucleated giant cells in both cases. When necessary, viral culture can be used to distinguish the 2 conditions, although HSV often takes 24 to 72 hours to grow and herpes zoster may take up to 2 weeks.9,10 Increasingly, polymerase chain reaction is being used for this purpose.

Antivirals are used for both genital and non-genital recurrences

The mainstay of treatment for HSV is antiviral therapy with acyclovir. Famciclovir and valacyclovir can be used as well (TABLE).11 These antivirals inhibit viral DNA replication, shorten duration of symptoms, increase lesion healing, and decrease viral shedding time.12 They are generally safe; the main adverse effects of oral therapy are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

In general, non-genital recurrences of HSV are treated the same as genital recurrences.13 Dosing during prodromal symptoms, or at the first sign of a recurrence is recommended for maximum efficacy.13 Suppressive therapy can be effective in patients who experience frequent recurrences and is generally recommended for 6 months to a year or longer.

Patients should also be warned that because of increased genital viral shedding during sacral recurrences, they should avoid sexual contact during outbreaks.14

Our patient began taking oral valacyclovir 1 g daily and had no recurrences over the next year.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

A 35-year-old woman sought care at our dermatology clinic with the self-diagnosis of “recurrent shingles,” noting that she’d had a rash over her sacrum on and off for the past 10 years. She said that the tender blisters typically appeared in this area 3 to 4 times per year (FIGURE) and that their onset was occasionally associated with stress. The rash tended to resolve—without treatment—within 5 to 7 days. The patient had no other medical problems or symptoms. Physical examination revealed 3 groups of vesicular lesions, each on an erythematous base, located bilaterally over the gluteal cleft.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Recurrent herpes simplex virus-2

While the presentation of herpes zoster (shingles) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) is similar—grouped vesicles on an erythematous base—recurrent shingles is rare in immunocompetent patients. Also, the herpes zoster rash is generally unilateral and is not common on the buttocks.1,2

Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) generally occurs around the mouth. Herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) is generally a genital rash. (Our patient was not aware that she’d had a genital primary HSV-2 infection.) That said, non-genital recurrences in the sacral region and lower extremities occur in up to 60% of patients whose primary genital HSV-2 infection also involved non-genital sites.3

HSV-2 infects an estimated 5% to 25% of adults in western nations.4 In 2012, approximately 417 million people ages 15 to 49 were living with HSV-2 worldwide, including 19 million who were newly infected.5

A dormant infection that is reactivated. Following a genital primary infection, HSV-2 lies dormant in the sacral nerve root ganglia, which innervate both the genitals and sacrum. Reactivation can thus result in recurrences anywhere over the sacral dermatome.6 The sacral area is the most common non-genital site for recurrent HSV-2.3 Reactivation of HSV-2 is more common and more severe in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection.7

Neurologic complications in some patients with genital herpes (eg, sacral radiculopathy, hyperesthesia) reinforce the hypothesis that genital herpes can infect ganglia that are also associated with sacral nerves.8 Contrary to popular belief, sacral HSV-2 is not commonly contracted from toilet seats.

How to differentiate herpes simplex from herpes zoster

As noted earlier, the location of the vesicles and unilateral nature of herpes zoster are useful in differentiating HSV from herpes zoster.

Tzanck preparation can’t be used to differentiate HSV and herpes zoster because it will demonstrate multinucleated giant cells in both cases. When necessary, viral culture can be used to distinguish the 2 conditions, although HSV often takes 24 to 72 hours to grow and herpes zoster may take up to 2 weeks.9,10 Increasingly, polymerase chain reaction is being used for this purpose.

Antivirals are used for both genital and non-genital recurrences

The mainstay of treatment for HSV is antiviral therapy with acyclovir. Famciclovir and valacyclovir can be used as well (TABLE).11 These antivirals inhibit viral DNA replication, shorten duration of symptoms, increase lesion healing, and decrease viral shedding time.12 They are generally safe; the main adverse effects of oral therapy are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

In general, non-genital recurrences of HSV are treated the same as genital recurrences.13 Dosing during prodromal symptoms, or at the first sign of a recurrence is recommended for maximum efficacy.13 Suppressive therapy can be effective in patients who experience frequent recurrences and is generally recommended for 6 months to a year or longer.

Patients should also be warned that because of increased genital viral shedding during sacral recurrences, they should avoid sexual contact during outbreaks.14

Our patient began taking oral valacyclovir 1 g daily and had no recurrences over the next year.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, et al. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1605-1609.

2. Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

3. Benedetti JK, Zeh J, Selke S, et al. Frequency and reactivation of nongenital lesions among patients with genital herpes simplex virus. Am J Med. 1995;98:237-242.

4. Smith JS, Robinson NJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. J Infect Dis. 2002;186 Suppl 1:S3-S28.

5. Looker KJ, Magaret AS, Turner KME, et al. Global estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type 2 infections in 2012. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e114989.

6. Corey L, Adams HG, Brown ZA, et al. Genital herpes simplex virus infections: clinical manifestations, course, and complications. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:958-972.

7. Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

8. Ooi C, Zawar V. Hyperaesthesia following genital herpes: a case report. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:903595.

9. Domeika M, Bashmakova M, Savicheva A, et al; Eastern European Network for Sexual and Reproductive Health (EE SRH Network). Guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of genital herpes in eastern European countries. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(44). pii:19703.

10. Solomon AR, Rasmussen JE, Weiss JS. A comparison of the Tzanck smear and viral isolation in varicella and herpes zoster. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:282-285.

11. Cernik C, Gallina K, Brodell RT. The treatment of herpes simplex infections: an evidence-based review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1137-1144.

12. Goldberg LH, Kaufman R, Conant MA, et al. Oral acyclovir for episodic treatment of recurrent genital herpes. Efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:256-264.

13. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s color atlas and synopsis of clinical dermatology. 5th ed. Chicago, IL: McGraw-Hill:2005;800-803.

14. Kerkering K, Gardella C, Selke S, et al. Isolation of herpes simplex virus from the genital tract during symptomatic recurrence on the buttocks. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:947-952.

1. Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, et al. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1605-1609.

2. Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

3. Benedetti JK, Zeh J, Selke S, et al. Frequency and reactivation of nongenital lesions among patients with genital herpes simplex virus. Am J Med. 1995;98:237-242.

4. Smith JS, Robinson NJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. J Infect Dis. 2002;186 Suppl 1:S3-S28.

5. Looker KJ, Magaret AS, Turner KME, et al. Global estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type 2 infections in 2012. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e114989.

6. Corey L, Adams HG, Brown ZA, et al. Genital herpes simplex virus infections: clinical manifestations, course, and complications. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:958-972.

7. Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

8. Ooi C, Zawar V. Hyperaesthesia following genital herpes: a case report. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:903595.

9. Domeika M, Bashmakova M, Savicheva A, et al; Eastern European Network for Sexual and Reproductive Health (EE SRH Network). Guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of genital herpes in eastern European countries. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(44). pii:19703.

10. Solomon AR, Rasmussen JE, Weiss JS. A comparison of the Tzanck smear and viral isolation in varicella and herpes zoster. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:282-285.

11. Cernik C, Gallina K, Brodell RT. The treatment of herpes simplex infections: an evidence-based review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1137-1144.

12. Goldberg LH, Kaufman R, Conant MA, et al. Oral acyclovir for episodic treatment of recurrent genital herpes. Efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:256-264.

13. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s color atlas and synopsis of clinical dermatology. 5th ed. Chicago, IL: McGraw-Hill:2005;800-803.

14. Kerkering K, Gardella C, Selke S, et al. Isolation of herpes simplex virus from the genital tract during symptomatic recurrence on the buttocks. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:947-952.

Large red area on infant’s face

This patient had a large infantile hemangioma on her face and scalp that needed immediate treatment to prevent amblyopia in the left eye. There was also concern for PHACE (posterior fossa malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities) syndrome. Any large segmental hemangioma on the face could be part of PHACE syndrome and therefore would require an evaluation of the child’s eyes, central nervous system, and heart.

The FP referred the patient to a pediatric dermatologist who initiated oral propranolol therapy. The workup for PHACE syndrome was negative, and the hemangioma responded well to the propranolol.

Photo courtesy of John Browning, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Madhukar M. Childhood hemangiomas and vascular malformations. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:636-641.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

This patient had a large infantile hemangioma on her face and scalp that needed immediate treatment to prevent amblyopia in the left eye. There was also concern for PHACE (posterior fossa malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities) syndrome. Any large segmental hemangioma on the face could be part of PHACE syndrome and therefore would require an evaluation of the child’s eyes, central nervous system, and heart.

The FP referred the patient to a pediatric dermatologist who initiated oral propranolol therapy. The workup for PHACE syndrome was negative, and the hemangioma responded well to the propranolol.

Photo courtesy of John Browning, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Madhukar M. Childhood hemangiomas and vascular malformations. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:636-641.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

This patient had a large infantile hemangioma on her face and scalp that needed immediate treatment to prevent amblyopia in the left eye. There was also concern for PHACE (posterior fossa malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities) syndrome. Any large segmental hemangioma on the face could be part of PHACE syndrome and therefore would require an evaluation of the child’s eyes, central nervous system, and heart.

The FP referred the patient to a pediatric dermatologist who initiated oral propranolol therapy. The workup for PHACE syndrome was negative, and the hemangioma responded well to the propranolol.

Photo courtesy of John Browning, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Madhukar M. Childhood hemangiomas and vascular malformations. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:636-641.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Red area on back of scalp

The FP recognized that the young patient had a salmon patch (a variant of nevus flammeus or port-wine stain) on her neck. The mark is often referred to as a “stork bite” and is not dangerous. (Parents often see the humor in the idea that this is where the stork held the child while delivering the baby to the parents.) These vascular malformations are not the same as hemangiomas.

Superficial capillary malformations are frequently seen in infants above the eyelids and on the nape of the neck. “Angel kisses” (salmon patches on the eyelids) usually disappear by 2 years of age. The “stork bites” may last into adulthood, but are rarely an issue because they often get covered by hair.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Madhukar M. Childhood hemangiomas and vascular malformations. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:636-641.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that the young patient had a salmon patch (a variant of nevus flammeus or port-wine stain) on her neck. The mark is often referred to as a “stork bite” and is not dangerous. (Parents often see the humor in the idea that this is where the stork held the child while delivering the baby to the parents.) These vascular malformations are not the same as hemangiomas.

Superficial capillary malformations are frequently seen in infants above the eyelids and on the nape of the neck. “Angel kisses” (salmon patches on the eyelids) usually disappear by 2 years of age. The “stork bites” may last into adulthood, but are rarely an issue because they often get covered by hair.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Madhukar M. Childhood hemangiomas and vascular malformations. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:636-641.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that the young patient had a salmon patch (a variant of nevus flammeus or port-wine stain) on her neck. The mark is often referred to as a “stork bite” and is not dangerous. (Parents often see the humor in the idea that this is where the stork held the child while delivering the baby to the parents.) These vascular malformations are not the same as hemangiomas.

Superficial capillary malformations are frequently seen in infants above the eyelids and on the nape of the neck. “Angel kisses” (salmon patches on the eyelids) usually disappear by 2 years of age. The “stork bites” may last into adulthood, but are rarely an issue because they often get covered by hair.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Madhukar M. Childhood hemangiomas and vascular malformations. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:636-641.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Mass on infant’s arm

The FP recognized that the patient had a deep (cavernous) hemangioma. Hemangiomas consist of an abnormally dense group of dilated blood vessels. The proliferation phase occurs during the first year, and most growth takes place during the first 6 months of life. Proliferation then slows and the hemangioma begins to involute.

Hemangiomas may be superficial, deep, or a combination of both. Superficial hemangiomas (“strawberry” marks) are well-defined, bright red, and appear as nodules or plaques located on clinically normal skin. Deep (cavernous) hemangiomas (like this patient’s) are raised, flesh-colored nodules that often have a bluish hue and feel firm and rubbery. Most are clinically insignificant unless they impinge on vital structures, ulcerate, bleed, incite a consumptive coagulopathy, or cause high output cardiac failure or structural abnormalities.

In this case, there was no need for aggressive treatment because there were no signs of ulcerations or bleeding, and because the hemangioma was not blocking any of the infant’s essential organs. The FP reassured the parents that the hemangioma was likely to involute over time and might very well resolve completely without any treatment. The FP also explained that hemangiomas don't just pop open spontaneously—or secondary to minor trauma—and bleed. The parents were adequately reassured by this and planned to return for further follow up at the one-year well-child visit.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Madhukar M. Childhood hemangiomas and vascular malformations. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:636-641.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that the patient had a deep (cavernous) hemangioma. Hemangiomas consist of an abnormally dense group of dilated blood vessels. The proliferation phase occurs during the first year, and most growth takes place during the first 6 months of life. Proliferation then slows and the hemangioma begins to involute.

Hemangiomas may be superficial, deep, or a combination of both. Superficial hemangiomas (“strawberry” marks) are well-defined, bright red, and appear as nodules or plaques located on clinically normal skin. Deep (cavernous) hemangiomas (like this patient’s) are raised, flesh-colored nodules that often have a bluish hue and feel firm and rubbery. Most are clinically insignificant unless they impinge on vital structures, ulcerate, bleed, incite a consumptive coagulopathy, or cause high output cardiac failure or structural abnormalities.

In this case, there was no need for aggressive treatment because there were no signs of ulcerations or bleeding, and because the hemangioma was not blocking any of the infant’s essential organs. The FP reassured the parents that the hemangioma was likely to involute over time and might very well resolve completely without any treatment. The FP also explained that hemangiomas don't just pop open spontaneously—or secondary to minor trauma—and bleed. The parents were adequately reassured by this and planned to return for further follow up at the one-year well-child visit.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Madhukar M. Childhood hemangiomas and vascular malformations. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:636-641.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that the patient had a deep (cavernous) hemangioma. Hemangiomas consist of an abnormally dense group of dilated blood vessels. The proliferation phase occurs during the first year, and most growth takes place during the first 6 months of life. Proliferation then slows and the hemangioma begins to involute.

Hemangiomas may be superficial, deep, or a combination of both. Superficial hemangiomas (“strawberry” marks) are well-defined, bright red, and appear as nodules or plaques located on clinically normal skin. Deep (cavernous) hemangiomas (like this patient’s) are raised, flesh-colored nodules that often have a bluish hue and feel firm and rubbery. Most are clinically insignificant unless they impinge on vital structures, ulcerate, bleed, incite a consumptive coagulopathy, or cause high output cardiac failure or structural abnormalities.

In this case, there was no need for aggressive treatment because there were no signs of ulcerations or bleeding, and because the hemangioma was not blocking any of the infant’s essential organs. The FP reassured the parents that the hemangioma was likely to involute over time and might very well resolve completely without any treatment. The FP also explained that hemangiomas don't just pop open spontaneously—or secondary to minor trauma—and bleed. The parents were adequately reassured by this and planned to return for further follow up at the one-year well-child visit.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Madhukar M. Childhood hemangiomas and vascular malformations. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:636-641.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Vomiting and abdominal pain in a woman with diabetes

A 60-year-old woman with diabetes sought treatment for worsening generalized abdominal pain and intermittent vomiting that she’d had for 5 days. She was afebrile and had no history of abdominal surgeries.

Liver function and amylase tests were normal. Lab work revealed normal sodium and potassium levels and a normal platelet count. The patient’s hemoglobin was 12.2 g/dL (normal 12.3-15.3 g/dL); white blood cell count, 150,000 mcL (normal 4500-11,000 mcL); serum blood urea nitrogen, 25 mg/dL (normal 6-20 mg/dL); serum creatinine, 1.3 mg/dL (normal 0.6-1.2 mg/dL); and blood glucose, 331 mg/dL (normal <125 mg/dL).

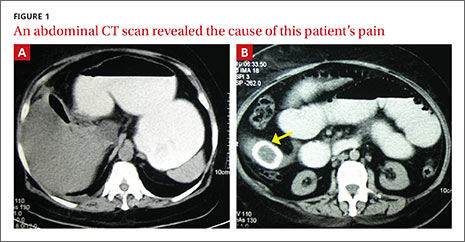

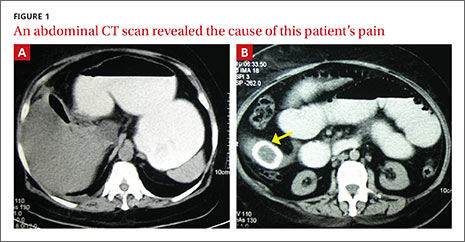

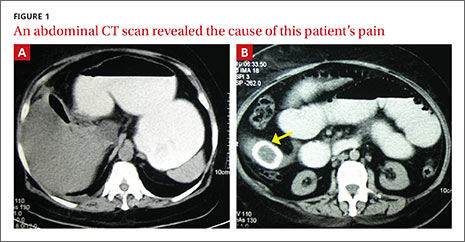

On physical examination, the patient had moderate abdominal distension without tenderness. Murphy’s sign was negative. A digital rectal examination revealed an empty rectum. The patient was hospitalized for further work-up and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen was performed (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Gallstone ileus

Evaluation of the spiral CT scan revealed abnormal gas in the gallbladder fossa (FIGURE 1A), gas in the biliary tree, and distended loops of small bowel consistent with partial small bowel obstruction. A laminated calcified mass was present in the ileal lumen in the right iliac fossa (FIGURE 1B, arrow). These findings suggested gallstone ileus.1

Gallstone ileus is a rare complication of recurrent gallstones.2 It accounts for 1% to 4% of all cases of mechanical intestinal obstruction, but up to 25% of cases in patients older than age 65.2 The condition is more common in women2 and, if missed, is associated with a high degree of morbidity and mortality.3

Rule out other causes of right upper quadrant pain

The differential diagnosis for gallstone ileus includes other causes of right upper quadrant pain.

Acute cholecystitis is characterized by abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant that extends to the shoulder. It can be visualized by sonography as a gallbladder with a thickened wall.4

Acute cholangitis typically presents with fever, right upper quadrant pain, and jaundice (Charcot’s triad).

Biliary colic is associated with right upper quadrant or epigastric pain that begins postprandially.

Hepatitis can be asymptomatic or the patient can have icterus with gastrointestinal symptoms, depending on the type of causative virus and phase of illness.

Also consider other potential causes of small bowel obstruction.

Gastric or duodenal ulcers usually present with painless bleeding and can be diagnosed with an upper endoscopy.4

Pancreatitis is characterized by high lipase levels and patients may describe the pain as feeling “like a belt around the upper abdomen.”4

Bowel ischemia is usually characterized by diffuse pain, diarrhea, and a positive lactate test.4

Imaging leads to a prompt Dx

In a patient with gallstone ileus, imaging studies typically show a classic radiographic triad (Rigler’s triad) consisting of small bowel obstruction, pneumobilia, and an ectopic gallstone.2,5 Optimizing patient management hinges on prompt correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalances and surgical intervention.

Surgical management of gallstone ileus must be individualized according to the patient’s comorbid conditions.6 Patients with significant comorbidities are usually managed with a 2-stage procedure: first with enterolithotomy to relieve the obstruction, and later with biliary tract surgery.7 This approach avoids the need for fistula exploration and reduces operative time. (Most fistulas close spontaneously if left alone.) Performing enterolithotomy and biliary tract surgery at the same time (a one-stage procedure) is more technically difficult, but reduces the risk of recurrent gallstone ileus or cholecystitis. Published reports show a lower mortality rate for the 2-stage procedure (11%) compared to the one-stage procedure (16.7%).7

After fluid resuscitation, our patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy, during which a 2.5 x 1.5 cm stone was extracted from the ileum. A cholecystoduodenal fistula was left intact because the chances of recurrence are very low and the patient did not have residual gallstones. Fistula repair is usually done 6 to 8 weeks after resolution of acute symptoms, but a less aggressive surgical approach was used for our patient. The patient remained well on follow-up at 6 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chhavi Kaushik, MD, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, 132 S. 10th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107; [email protected]

1. Masannat Y, Shatnawei A. Gallstone ileus: a review. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73:1132-1134.

2. Chou JW, Hsu CH, Liao KF, et al. Gallstone ileus: report of two cases and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1295-1298.

3. Lobo DN, Jobling JC, Balfour TW. Gallstone ileus: diagnostic pitfalls and therapeutic successes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:72-76.

4. Zuber-Jerger I, Kullmann F, Schneidewind A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of a patient with gallstone ileus. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:331-335.

5. Delabrousse E, Bartholomot B, Sohm O, et al. Gallstone ileus: CT findings. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:938-940.

6. Mallipeddi MK, Pappas TN, Shapiro ML, et al. Gallstone ileus: revisiting surgical outcomes using National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data. J Surg Res. 2013;184:84-88.

7. Rodríguez-Sanjuán JC, Casado F, Fernández MJ, et al. Cholecystectomy and fistula closure versus enterolithotomy alone in gallstone ileus. Br J Surg. 1997:84:634-637.

A 60-year-old woman with diabetes sought treatment for worsening generalized abdominal pain and intermittent vomiting that she’d had for 5 days. She was afebrile and had no history of abdominal surgeries.

Liver function and amylase tests were normal. Lab work revealed normal sodium and potassium levels and a normal platelet count. The patient’s hemoglobin was 12.2 g/dL (normal 12.3-15.3 g/dL); white blood cell count, 150,000 mcL (normal 4500-11,000 mcL); serum blood urea nitrogen, 25 mg/dL (normal 6-20 mg/dL); serum creatinine, 1.3 mg/dL (normal 0.6-1.2 mg/dL); and blood glucose, 331 mg/dL (normal <125 mg/dL).

On physical examination, the patient had moderate abdominal distension without tenderness. Murphy’s sign was negative. A digital rectal examination revealed an empty rectum. The patient was hospitalized for further work-up and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen was performed (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Gallstone ileus

Evaluation of the spiral CT scan revealed abnormal gas in the gallbladder fossa (FIGURE 1A), gas in the biliary tree, and distended loops of small bowel consistent with partial small bowel obstruction. A laminated calcified mass was present in the ileal lumen in the right iliac fossa (FIGURE 1B, arrow). These findings suggested gallstone ileus.1

Gallstone ileus is a rare complication of recurrent gallstones.2 It accounts for 1% to 4% of all cases of mechanical intestinal obstruction, but up to 25% of cases in patients older than age 65.2 The condition is more common in women2 and, if missed, is associated with a high degree of morbidity and mortality.3

Rule out other causes of right upper quadrant pain

The differential diagnosis for gallstone ileus includes other causes of right upper quadrant pain.

Acute cholecystitis is characterized by abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant that extends to the shoulder. It can be visualized by sonography as a gallbladder with a thickened wall.4

Acute cholangitis typically presents with fever, right upper quadrant pain, and jaundice (Charcot’s triad).

Biliary colic is associated with right upper quadrant or epigastric pain that begins postprandially.

Hepatitis can be asymptomatic or the patient can have icterus with gastrointestinal symptoms, depending on the type of causative virus and phase of illness.

Also consider other potential causes of small bowel obstruction.

Gastric or duodenal ulcers usually present with painless bleeding and can be diagnosed with an upper endoscopy.4

Pancreatitis is characterized by high lipase levels and patients may describe the pain as feeling “like a belt around the upper abdomen.”4

Bowel ischemia is usually characterized by diffuse pain, diarrhea, and a positive lactate test.4

Imaging leads to a prompt Dx

In a patient with gallstone ileus, imaging studies typically show a classic radiographic triad (Rigler’s triad) consisting of small bowel obstruction, pneumobilia, and an ectopic gallstone.2,5 Optimizing patient management hinges on prompt correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalances and surgical intervention.

Surgical management of gallstone ileus must be individualized according to the patient’s comorbid conditions.6 Patients with significant comorbidities are usually managed with a 2-stage procedure: first with enterolithotomy to relieve the obstruction, and later with biliary tract surgery.7 This approach avoids the need for fistula exploration and reduces operative time. (Most fistulas close spontaneously if left alone.) Performing enterolithotomy and biliary tract surgery at the same time (a one-stage procedure) is more technically difficult, but reduces the risk of recurrent gallstone ileus or cholecystitis. Published reports show a lower mortality rate for the 2-stage procedure (11%) compared to the one-stage procedure (16.7%).7

After fluid resuscitation, our patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy, during which a 2.5 x 1.5 cm stone was extracted from the ileum. A cholecystoduodenal fistula was left intact because the chances of recurrence are very low and the patient did not have residual gallstones. Fistula repair is usually done 6 to 8 weeks after resolution of acute symptoms, but a less aggressive surgical approach was used for our patient. The patient remained well on follow-up at 6 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chhavi Kaushik, MD, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, 132 S. 10th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107; [email protected]

A 60-year-old woman with diabetes sought treatment for worsening generalized abdominal pain and intermittent vomiting that she’d had for 5 days. She was afebrile and had no history of abdominal surgeries.

Liver function and amylase tests were normal. Lab work revealed normal sodium and potassium levels and a normal platelet count. The patient’s hemoglobin was 12.2 g/dL (normal 12.3-15.3 g/dL); white blood cell count, 150,000 mcL (normal 4500-11,000 mcL); serum blood urea nitrogen, 25 mg/dL (normal 6-20 mg/dL); serum creatinine, 1.3 mg/dL (normal 0.6-1.2 mg/dL); and blood glucose, 331 mg/dL (normal <125 mg/dL).

On physical examination, the patient had moderate abdominal distension without tenderness. Murphy’s sign was negative. A digital rectal examination revealed an empty rectum. The patient was hospitalized for further work-up and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen was performed (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Gallstone ileus

Evaluation of the spiral CT scan revealed abnormal gas in the gallbladder fossa (FIGURE 1A), gas in the biliary tree, and distended loops of small bowel consistent with partial small bowel obstruction. A laminated calcified mass was present in the ileal lumen in the right iliac fossa (FIGURE 1B, arrow). These findings suggested gallstone ileus.1

Gallstone ileus is a rare complication of recurrent gallstones.2 It accounts for 1% to 4% of all cases of mechanical intestinal obstruction, but up to 25% of cases in patients older than age 65.2 The condition is more common in women2 and, if missed, is associated with a high degree of morbidity and mortality.3

Rule out other causes of right upper quadrant pain

The differential diagnosis for gallstone ileus includes other causes of right upper quadrant pain.

Acute cholecystitis is characterized by abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant that extends to the shoulder. It can be visualized by sonography as a gallbladder with a thickened wall.4

Acute cholangitis typically presents with fever, right upper quadrant pain, and jaundice (Charcot’s triad).

Biliary colic is associated with right upper quadrant or epigastric pain that begins postprandially.

Hepatitis can be asymptomatic or the patient can have icterus with gastrointestinal symptoms, depending on the type of causative virus and phase of illness.

Also consider other potential causes of small bowel obstruction.

Gastric or duodenal ulcers usually present with painless bleeding and can be diagnosed with an upper endoscopy.4

Pancreatitis is characterized by high lipase levels and patients may describe the pain as feeling “like a belt around the upper abdomen.”4

Bowel ischemia is usually characterized by diffuse pain, diarrhea, and a positive lactate test.4

Imaging leads to a prompt Dx

In a patient with gallstone ileus, imaging studies typically show a classic radiographic triad (Rigler’s triad) consisting of small bowel obstruction, pneumobilia, and an ectopic gallstone.2,5 Optimizing patient management hinges on prompt correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalances and surgical intervention.

Surgical management of gallstone ileus must be individualized according to the patient’s comorbid conditions.6 Patients with significant comorbidities are usually managed with a 2-stage procedure: first with enterolithotomy to relieve the obstruction, and later with biliary tract surgery.7 This approach avoids the need for fistula exploration and reduces operative time. (Most fistulas close spontaneously if left alone.) Performing enterolithotomy and biliary tract surgery at the same time (a one-stage procedure) is more technically difficult, but reduces the risk of recurrent gallstone ileus or cholecystitis. Published reports show a lower mortality rate for the 2-stage procedure (11%) compared to the one-stage procedure (16.7%).7

After fluid resuscitation, our patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy, during which a 2.5 x 1.5 cm stone was extracted from the ileum. A cholecystoduodenal fistula was left intact because the chances of recurrence are very low and the patient did not have residual gallstones. Fistula repair is usually done 6 to 8 weeks after resolution of acute symptoms, but a less aggressive surgical approach was used for our patient. The patient remained well on follow-up at 6 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chhavi Kaushik, MD, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, 132 S. 10th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107; [email protected]

1. Masannat Y, Shatnawei A. Gallstone ileus: a review. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73:1132-1134.

2. Chou JW, Hsu CH, Liao KF, et al. Gallstone ileus: report of two cases and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1295-1298.

3. Lobo DN, Jobling JC, Balfour TW. Gallstone ileus: diagnostic pitfalls and therapeutic successes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:72-76.

4. Zuber-Jerger I, Kullmann F, Schneidewind A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of a patient with gallstone ileus. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:331-335.

5. Delabrousse E, Bartholomot B, Sohm O, et al. Gallstone ileus: CT findings. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:938-940.

6. Mallipeddi MK, Pappas TN, Shapiro ML, et al. Gallstone ileus: revisiting surgical outcomes using National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data. J Surg Res. 2013;184:84-88.

7. Rodríguez-Sanjuán JC, Casado F, Fernández MJ, et al. Cholecystectomy and fistula closure versus enterolithotomy alone in gallstone ileus. Br J Surg. 1997:84:634-637.

1. Masannat Y, Shatnawei A. Gallstone ileus: a review. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73:1132-1134.

2. Chou JW, Hsu CH, Liao KF, et al. Gallstone ileus: report of two cases and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1295-1298.

3. Lobo DN, Jobling JC, Balfour TW. Gallstone ileus: diagnostic pitfalls and therapeutic successes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:72-76.

4. Zuber-Jerger I, Kullmann F, Schneidewind A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of a patient with gallstone ileus. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:331-335.

5. Delabrousse E, Bartholomot B, Sohm O, et al. Gallstone ileus: CT findings. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:938-940.

6. Mallipeddi MK, Pappas TN, Shapiro ML, et al. Gallstone ileus: revisiting surgical outcomes using National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data. J Surg Res. 2013;184:84-88.

7. Rodríguez-Sanjuán JC, Casado F, Fernández MJ, et al. Cholecystectomy and fistula closure versus enterolithotomy alone in gallstone ileus. Br J Surg. 1997:84:634-637.

Painful ear nodules

The patient was given a diagnosis of levamisole toxicity, based on his clinical presentation and the fact that he had used cocaine around the time his ear lesions appeared. Levamisole—primarily a veterinary anthelmintic medication—is used on rare occasions to treat nephrotic syndrome in children. Levamisole's physical similarity to cocaine also allows it to act as a cutting or bulking agent, increasing the total weight of the sample and making the drug appear purer. Levamisole adulteration often occurs as part of the refining process of cocaine production.

Patients with levamisole toxicity present with sudden onset tender plaques or bullae with necrotic centers within days of cocaine use. Lesions primarily appear on the ears and cheeks, although they can appear almost anywhere on the body. It’s important to have a high index of suspicion for levamisole toxicity in patients using cocaine who present with unexplained neutropenia or vasculitis. If needed, tissue biopsy and urine detection of levamisole can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Skin lesions have been reported to improve several weeks after discontinuing use of the contaminated cocaine. Known users should be referred to drug treatment centers and counseled on the risks of use.