User login

Red growth on infant’s face

The FP recognized that the baby had a large infantile hemangioma on her face that needed immediate treatment to prevent amblyopia in the left eye. There was also concern for PHACE (posterior fossa malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities) syndrome. Any large segmental hemangioma on the face could be part of PHACE syndrome and therefore would require evaluation of the eyes, central nervous system, and heart.

Hemangiomas consist of an abnormally dense group of dilated blood vessels that are thought to occur sporadically. They are characterized by an initial phase of rapid proliferation followed by spontaneous and slow involution. Often, they lead to complete regression. Most childhood hemangiomas are small and innocuous, but some can grow to threaten a particular function or even an infant’s life.

Rapid growth during the first month of life is the historical hallmark of hemangiomas because rapidly dividing endothelial cells are responsible for the enlargement of these lesions. The hemangiomas become elevated and may take on numerous morphologies (dome-shaped, lobulated, plaque-like, and/or tumoral).

The proliferation phase occurs during the first year, and most growth takes place during the first 6 months of life. Proliferation then slows, and the hemangioma begins to involute. Typically, 50% of childhood hemangiomas will involute by age 5, 70% by age 7, and the remainder will take an additional 3 to 5 years to complete the process of involution.

Large periocular hemangiomas demand prompt treatment to prevent debilitating consequences such as amblyopia. Propranolol is the first-line treatment for function-impairing and rapidly proliferating infantile hemangiomas. It has been successfully used to treat periorbital infantile hemangiomas and other problematic infantile hemangiomas.

The FP administered all the appropriate vaccines to the infant and told her parents to bring her to a pediatric dermatologist and an ophthalmologist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Madhukar M. Childhood hemangiomas and vascular malformations. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:636-641.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that the baby had a large infantile hemangioma on her face that needed immediate treatment to prevent amblyopia in the left eye. There was also concern for PHACE (posterior fossa malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities) syndrome. Any large segmental hemangioma on the face could be part of PHACE syndrome and therefore would require evaluation of the eyes, central nervous system, and heart.

Hemangiomas consist of an abnormally dense group of dilated blood vessels that are thought to occur sporadically. They are characterized by an initial phase of rapid proliferation followed by spontaneous and slow involution. Often, they lead to complete regression. Most childhood hemangiomas are small and innocuous, but some can grow to threaten a particular function or even an infant’s life.

Rapid growth during the first month of life is the historical hallmark of hemangiomas because rapidly dividing endothelial cells are responsible for the enlargement of these lesions. The hemangiomas become elevated and may take on numerous morphologies (dome-shaped, lobulated, plaque-like, and/or tumoral).

The proliferation phase occurs during the first year, and most growth takes place during the first 6 months of life. Proliferation then slows, and the hemangioma begins to involute. Typically, 50% of childhood hemangiomas will involute by age 5, 70% by age 7, and the remainder will take an additional 3 to 5 years to complete the process of involution.

Large periocular hemangiomas demand prompt treatment to prevent debilitating consequences such as amblyopia. Propranolol is the first-line treatment for function-impairing and rapidly proliferating infantile hemangiomas. It has been successfully used to treat periorbital infantile hemangiomas and other problematic infantile hemangiomas.

The FP administered all the appropriate vaccines to the infant and told her parents to bring her to a pediatric dermatologist and an ophthalmologist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Madhukar M. Childhood hemangiomas and vascular malformations. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:636-641.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that the baby had a large infantile hemangioma on her face that needed immediate treatment to prevent amblyopia in the left eye. There was also concern for PHACE (posterior fossa malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities) syndrome. Any large segmental hemangioma on the face could be part of PHACE syndrome and therefore would require evaluation of the eyes, central nervous system, and heart.

Hemangiomas consist of an abnormally dense group of dilated blood vessels that are thought to occur sporadically. They are characterized by an initial phase of rapid proliferation followed by spontaneous and slow involution. Often, they lead to complete regression. Most childhood hemangiomas are small and innocuous, but some can grow to threaten a particular function or even an infant’s life.

Rapid growth during the first month of life is the historical hallmark of hemangiomas because rapidly dividing endothelial cells are responsible for the enlargement of these lesions. The hemangiomas become elevated and may take on numerous morphologies (dome-shaped, lobulated, plaque-like, and/or tumoral).

The proliferation phase occurs during the first year, and most growth takes place during the first 6 months of life. Proliferation then slows, and the hemangioma begins to involute. Typically, 50% of childhood hemangiomas will involute by age 5, 70% by age 7, and the remainder will take an additional 3 to 5 years to complete the process of involution.

Large periocular hemangiomas demand prompt treatment to prevent debilitating consequences such as amblyopia. Propranolol is the first-line treatment for function-impairing and rapidly proliferating infantile hemangiomas. It has been successfully used to treat periorbital infantile hemangiomas and other problematic infantile hemangiomas.

The FP administered all the appropriate vaccines to the infant and told her parents to bring her to a pediatric dermatologist and an ophthalmologist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Madhukar M. Childhood hemangiomas and vascular malformations. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:636-641.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Skin discoloration on infant

The FP recognized this as cutis marmorata, a normal response to cold in infants. The pattern resolved when the infant was warmed. Cutis marmorata is reticulated, mottled skin with symmetric involvement of the trunk and extremities. This condition can come and go for weeks to months.

In this case, no treatment was needed, and the physician reassured the mother that it was normal and would resolve spontaneously in the coming months. The infant received her typical 4-month vaccines as planned.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Fernandez C, Smith M. Normal skin changes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:629-635.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as cutis marmorata, a normal response to cold in infants. The pattern resolved when the infant was warmed. Cutis marmorata is reticulated, mottled skin with symmetric involvement of the trunk and extremities. This condition can come and go for weeks to months.

In this case, no treatment was needed, and the physician reassured the mother that it was normal and would resolve spontaneously in the coming months. The infant received her typical 4-month vaccines as planned.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Fernandez C, Smith M. Normal skin changes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:629-635.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as cutis marmorata, a normal response to cold in infants. The pattern resolved when the infant was warmed. Cutis marmorata is reticulated, mottled skin with symmetric involvement of the trunk and extremities. This condition can come and go for weeks to months.

In this case, no treatment was needed, and the physician reassured the mother that it was normal and would resolve spontaneously in the coming months. The infant received her typical 4-month vaccines as planned.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Fernandez C, Smith M. Normal skin changes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:629-635.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Dark spots on child’s back

The FP recognized this as a case of dermal melanocytosis, also known as Mongolian spots. She reassured the mother that the spots would fade over time and were not dangerous. There were no suspicions of abuse, but the physician inquired about the child's safety and environment to avoid missing any red flags.

A Mongolian spot is a hereditary, congenital macule of bluish-black or bluish-gray pigment that usually occurs in the sacral area, back, and buttocks of infants. The spots result from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during their migration from the neural crest into the epidermis.

Mongolian spots have been reported in approximately 96% of black infants, 90% of Native American infants, 81% to 90% of Asian infants, 46% to 70% of Hispanic infants, and up to 10% of white infants. A few cases of extensive Mongolian spots have been reported with inborn errors of metabolism, the most common being Hurler syndrome, followed by gangliosidosis type 1, Niemann-Pick disease, Hunter syndrome, and mannosidosis. In such cases, the spots are likely to persist rather than resolve.

There are also reports of Mongolian spots being mistaken for the bruising that occurs from child abuse. A thorough history and a clear knowledge of the pattern of Mongolian spots should help to differentiate between the 2. Mongolian spots are likely to fade over time and may disappear by age 13.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Fernandez C, Smith M. Normal skin changes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 629-635.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as a case of dermal melanocytosis, also known as Mongolian spots. She reassured the mother that the spots would fade over time and were not dangerous. There were no suspicions of abuse, but the physician inquired about the child's safety and environment to avoid missing any red flags.

A Mongolian spot is a hereditary, congenital macule of bluish-black or bluish-gray pigment that usually occurs in the sacral area, back, and buttocks of infants. The spots result from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during their migration from the neural crest into the epidermis.

Mongolian spots have been reported in approximately 96% of black infants, 90% of Native American infants, 81% to 90% of Asian infants, 46% to 70% of Hispanic infants, and up to 10% of white infants. A few cases of extensive Mongolian spots have been reported with inborn errors of metabolism, the most common being Hurler syndrome, followed by gangliosidosis type 1, Niemann-Pick disease, Hunter syndrome, and mannosidosis. In such cases, the spots are likely to persist rather than resolve.

There are also reports of Mongolian spots being mistaken for the bruising that occurs from child abuse. A thorough history and a clear knowledge of the pattern of Mongolian spots should help to differentiate between the 2. Mongolian spots are likely to fade over time and may disappear by age 13.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Fernandez C, Smith M. Normal skin changes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 629-635.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized this as a case of dermal melanocytosis, also known as Mongolian spots. She reassured the mother that the spots would fade over time and were not dangerous. There were no suspicions of abuse, but the physician inquired about the child's safety and environment to avoid missing any red flags.

A Mongolian spot is a hereditary, congenital macule of bluish-black or bluish-gray pigment that usually occurs in the sacral area, back, and buttocks of infants. The spots result from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during their migration from the neural crest into the epidermis.

Mongolian spots have been reported in approximately 96% of black infants, 90% of Native American infants, 81% to 90% of Asian infants, 46% to 70% of Hispanic infants, and up to 10% of white infants. A few cases of extensive Mongolian spots have been reported with inborn errors of metabolism, the most common being Hurler syndrome, followed by gangliosidosis type 1, Niemann-Pick disease, Hunter syndrome, and mannosidosis. In such cases, the spots are likely to persist rather than resolve.

There are also reports of Mongolian spots being mistaken for the bruising that occurs from child abuse. A thorough history and a clear knowledge of the pattern of Mongolian spots should help to differentiate between the 2. Mongolian spots are likely to fade over time and may disappear by age 13.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Fernandez C, Smith M. Normal skin changes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 629-635.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

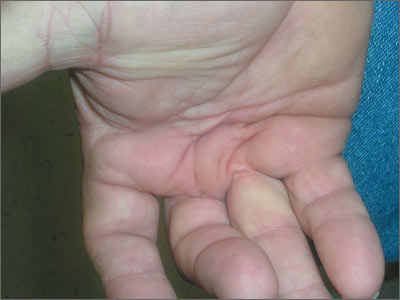

Stiffness in hands

The FP diagnosed Dupuytren contracture (also known as palmar fibromatosis, morbus Dupuytren), a flexion contracture of one or more fingers. Patients develop a progressive thickening of the palmar fascia that which causes the fingers to bend in toward the palm, limiting extension. Dupuytren contracture is an autosomal dominant disease with incomplete penetrance. The diagnosis is clinical and palpable nodules and/or cords in the palm are considered diagnostic.

Dupuytren contracture is more prevalent among whites, particularly Northern Europeans, and the incidence increases with age. Dupuytren contracture is more common in men than in women (approximately 6:1). People who use tobacco and alcohol, or who have diabetes mellitus or epilepsy, also have a higher incidence of the disease.

Treatment has historically been surgical, but a nonsurgical treatment with collagenase is now available.

Surgical correction is considered when there is at least 30 degrees of contracture at the metacarpophalangeal joint. A fasciotomy decreases the degree of flexion deformity and results in modest improvements in hand function. An intralesional injection of corticosteroids, however, is only mildly successful and may place the patient at risk for tendon rupture.

Studies indicate that improvements in function are correlated with changes at the proximal interphalangeal joint. The recurrence rate increases with time and is related to the amount of fascia that is removed during surgery.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Delzell J, Chumley H. Dupuytren disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:625-628.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed Dupuytren contracture (also known as palmar fibromatosis, morbus Dupuytren), a flexion contracture of one or more fingers. Patients develop a progressive thickening of the palmar fascia that which causes the fingers to bend in toward the palm, limiting extension. Dupuytren contracture is an autosomal dominant disease with incomplete penetrance. The diagnosis is clinical and palpable nodules and/or cords in the palm are considered diagnostic.

Dupuytren contracture is more prevalent among whites, particularly Northern Europeans, and the incidence increases with age. Dupuytren contracture is more common in men than in women (approximately 6:1). People who use tobacco and alcohol, or who have diabetes mellitus or epilepsy, also have a higher incidence of the disease.

Treatment has historically been surgical, but a nonsurgical treatment with collagenase is now available.

Surgical correction is considered when there is at least 30 degrees of contracture at the metacarpophalangeal joint. A fasciotomy decreases the degree of flexion deformity and results in modest improvements in hand function. An intralesional injection of corticosteroids, however, is only mildly successful and may place the patient at risk for tendon rupture.

Studies indicate that improvements in function are correlated with changes at the proximal interphalangeal joint. The recurrence rate increases with time and is related to the amount of fascia that is removed during surgery.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Delzell J, Chumley H. Dupuytren disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:625-628.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed Dupuytren contracture (also known as palmar fibromatosis, morbus Dupuytren), a flexion contracture of one or more fingers. Patients develop a progressive thickening of the palmar fascia that which causes the fingers to bend in toward the palm, limiting extension. Dupuytren contracture is an autosomal dominant disease with incomplete penetrance. The diagnosis is clinical and palpable nodules and/or cords in the palm are considered diagnostic.

Dupuytren contracture is more prevalent among whites, particularly Northern Europeans, and the incidence increases with age. Dupuytren contracture is more common in men than in women (approximately 6:1). People who use tobacco and alcohol, or who have diabetes mellitus or epilepsy, also have a higher incidence of the disease.

Treatment has historically been surgical, but a nonsurgical treatment with collagenase is now available.

Surgical correction is considered when there is at least 30 degrees of contracture at the metacarpophalangeal joint. A fasciotomy decreases the degree of flexion deformity and results in modest improvements in hand function. An intralesional injection of corticosteroids, however, is only mildly successful and may place the patient at risk for tendon rupture.

Studies indicate that improvements in function are correlated with changes at the proximal interphalangeal joint. The recurrence rate increases with time and is related to the amount of fascia that is removed during surgery.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Delzell J, Chumley H. Dupuytren disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:625-628.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Scarring alopecia in a woman with psoriasis

A 57-year-old African American woman came to our dermatology clinic to reestablish care. She had a long history of plaque psoriasis involving her trunk and extremities. More recently, she had developed progressive hair loss, which her previous physician had attributed to the psoriasis. Before this visit, our patient had been treating her psoriasis with topical clobetasol and calcipotriene.

A physical exam revealed multiple welldemarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques consistent with plaque psoriasis on her trunk and extremities. She also said her scalp was itchy, and we noted significant cicatricial (scarring) alopecia of the scalp, with faint perifollicular erythema, that was predominantly affecting the frontotemporal region (FIGURE). We performed a scalp biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen planopilaris

We suspected that this was not simply a case of plaque psoriasis because psoriasis of the scalp only causes non-cicatricial alopecia.1 Biopsy results confirmed that while the patient did have plaque psoriasis on her scalp, there was also evidence of peri-infundibular fibrosis and inflammation at the junction of the epidermis and dermis along the follicular epithelium. These 2 findings are pathognomonic for lichen planopilaris (LPP).

An uncommon diagnosis

Although its exact incidence and prevalence are unknown, LPP appears to be uncommon.2 The condition typically presents in adults ages 25 to 70, and is more common in women than in men.2 There is no known association between LPP and psoriasis.

Clinically, LPP manifests as cicatricial hair loss, often in a band-like fashion that can coalesce into larger, reticulated patterns.1 In addition to the scalp, LPP can affect other hair-bearing areas, such as the eyelids (lashes, brows), body, axillae, or pubic region.3,4 It is typically accompanied by burning and itching, and commonly presents with perifollicular erythema.1

LPP is thought to be the result of an immune-mediated lymphocytic inflammatory process that produces follicular hyperkeratosis, surrounding erythema, overlying scale, and, eventually, fibrosis and loss of the hair follicle.3,5

LPP has 3 variants: classic LPP, which typically affects the vertex and parietal areas of the scalp; frontal fibrosing alopecia, which is characterized by frontotemporal hair loss in a band-like pattern (as in our patient’s case); and Graham-Little syndrome, which can include cicatricial alopecia of the scalp and non-cicatricial alopecia of the axillary and pubic areas.3 Postmenopausal women appear to be at heightened risk for frontal fibrosing LPP.4

Differential diagnosis includes other types of scarring hair loss

The differential diagnosis for LPP includes discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), folliculitis decalvans, and dissecting cellulitis.1

DLE typically causes discrete, indurated lesions of central hypopigmentation (erythematous when active), along with slight atrophy and a rim of hyperpigmentation. This is in contrast to the perifollicular erythema and lack of atrophy that you’ll see in LPP. In addition, patients with DLE will have telangiectasias, while those with LPP will not.

CCCA is typically non-inflammatory, but can sometimes have symptoms such as mild itching. As the name implies, the hair loss associated with this disease starts in the central scalp and works its way centrifugally to the periphery, whereas in LPP, the alopecia can be patchy or diffuse, or can involve only the frontal scalp.2

Folliculitis decalvans is a form of scarring alopecia characterized by inflammatory perifollicular papules and pustules. Such lesions would not be observed in a patient with LPP. Bacterial culture will identify Staphylococcus aureus in most patients with untreated folliculitis decalvans.6

Dissecting cellulitis presents with tender, fluctuant nodules on the scalp that commonly suppurate and drain. The scarring hair loss that results could be mistaken for LPP, but a history of active, inflamed, nodular lesions will help to distinguish this condition from LPP.

Do a punch biopsy next to a patch of alopecia

A biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis of LPP.2 A 4 mm punch biopsy should be performed, and optimally, 2 adjacent biopsies are taken so that they can be sectioned both vertically and horizontally.2 The biopsy should be done adjacent to a patch of alopecia that still has most of the hair follicles present. This is important because a biopsy of an area of scalp completely scarred with no remaining hair follicles will not demonstrate the pathognomonic patterns of inflammation that will allow for an accurate diagnosis.

In early-stage LPP, histopathology will reveal a lichenoid interface inflammation with hypergranulosis, hyperkeratosis, and hyperacanthosis, whereas in later stages, inflammation may be minimal or absent, with fibrous tracts taking the place of destroyed hair follicles.7

Steroids have produced the best treatment outcomes

LPP has an unpredictable course.2 Currently, there is no cure, and in areas where follicle destruction has occurred, normal hair growth cannot be restored.2 Therefore, treatment should focus on preventing progression and improving symptoms. It is imperative to manage patients’ expectations when dealing with cicatricial hair loss to ensure that they understand the likely outcomes.

Topical corticosteroids alone have shown some efficacy in treating LPP, but intralesional corticosteroids and oral glucocorticosteroids have resulted in better outcomes.4 Typical doses for intralesional triamcinolone are up to 1 mL of 10 mg/mL to 40 mg/mL per treatment session, with a one-month interval between treatments. Oral steroids can be used to initially control the disease and would require approximately 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered over 3 to 4 weeks.

Adverse effects. Intralesional steroids can cause atrophy at the injection site and oral steroids can have rebound effects after an oral regimen is completed. This is in addition to other known adverse effects, such as insomnia and mood changes.4

Hydroxychloroquine has been reported to help arrest progression of, and control symptoms of, LPP with minimal adverse effects; a typical dosage is 200 mg twice a day.4 The 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors finasteride and dutasteride, which inhibit the conversion of testosterone to its more active form of dihydrotestosterone, have also shown similar efficacy.4

Finasteride can be used at a dose of 1 mg/d to 5 mg/d, and dutasteride is most effective at 0.5 to 2.5 mg/d.8 In a preliminary trial, pioglitazone (a peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptor gamma [PPAR-gamma] agonist) showed promise as a new treatment modality for LPP, perhaps because tissue expression of PPAR-gamma is decreased in LPP.9

A reasonable approach to therapy is to follow a stepwise increase from topical or intralesional corticosteroids to oral glucocorticosteroids, then to hydroxychloroquine or finasteride/dutasteride. The addition of a PPAR-gamma agonist can be added at any stage as adjunct therapy. A referral to a dermatologist may be necessary for refractory cases.

We started our patient on topical clobetasol 0.05% foam, which decreased her pruritus. However, we counseled her that we did not expect hair to regrow in the areas where she’d experienced hair loss. We continue to monitor her, and she would be a candidate for systemic therapy if the topical corticosteroid does not continue to control her disease.

CORRESPONDENCE

Simon Ritchie, MD, San Antonio Military Health System, 59MDSP/SGO7D, 2200 Berquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236; [email protected]

1. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby; 2004:214,252,841,855-856,860-861.

2. Shapiro J, Otberg N. Lichen planopilaris. UpToDate Web site. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/lichen-planopilaris. Accessed June 2, 2015.

3. Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcón C, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670-678.

4. Ross EK, Tan E, Shapiro J. Update on primary cicatricial alopecias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1-37.

5. Mobini N, Tam S, Kamino H. Possible role of the bulge region in the pathogenesis of inflammatory scarring alopecia: lichen planopilaris as the prototype. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:675-679.

6. Otberg N, Kang H, Alzolibani AA, et al. Folliculitis decalvans. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:238-244.

7. Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:3-10.

8. Olsen EA, Hordinsky M, Whiting D, et al. The importance of dual 5alpha-reductase inhibition in the treatment of male pattern hair loss: results of a randomized placebo-controlled study of dutasteride versus finasteride. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:1014-1023.

9. Baibergenova A, Walsh S. Use of pioglitazone in patients with lichen planopilaris. J Cutan Med Surg. 2012;16:97-100.

A 57-year-old African American woman came to our dermatology clinic to reestablish care. She had a long history of plaque psoriasis involving her trunk and extremities. More recently, she had developed progressive hair loss, which her previous physician had attributed to the psoriasis. Before this visit, our patient had been treating her psoriasis with topical clobetasol and calcipotriene.

A physical exam revealed multiple welldemarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques consistent with plaque psoriasis on her trunk and extremities. She also said her scalp was itchy, and we noted significant cicatricial (scarring) alopecia of the scalp, with faint perifollicular erythema, that was predominantly affecting the frontotemporal region (FIGURE). We performed a scalp biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen planopilaris

We suspected that this was not simply a case of plaque psoriasis because psoriasis of the scalp only causes non-cicatricial alopecia.1 Biopsy results confirmed that while the patient did have plaque psoriasis on her scalp, there was also evidence of peri-infundibular fibrosis and inflammation at the junction of the epidermis and dermis along the follicular epithelium. These 2 findings are pathognomonic for lichen planopilaris (LPP).

An uncommon diagnosis

Although its exact incidence and prevalence are unknown, LPP appears to be uncommon.2 The condition typically presents in adults ages 25 to 70, and is more common in women than in men.2 There is no known association between LPP and psoriasis.

Clinically, LPP manifests as cicatricial hair loss, often in a band-like fashion that can coalesce into larger, reticulated patterns.1 In addition to the scalp, LPP can affect other hair-bearing areas, such as the eyelids (lashes, brows), body, axillae, or pubic region.3,4 It is typically accompanied by burning and itching, and commonly presents with perifollicular erythema.1

LPP is thought to be the result of an immune-mediated lymphocytic inflammatory process that produces follicular hyperkeratosis, surrounding erythema, overlying scale, and, eventually, fibrosis and loss of the hair follicle.3,5

LPP has 3 variants: classic LPP, which typically affects the vertex and parietal areas of the scalp; frontal fibrosing alopecia, which is characterized by frontotemporal hair loss in a band-like pattern (as in our patient’s case); and Graham-Little syndrome, which can include cicatricial alopecia of the scalp and non-cicatricial alopecia of the axillary and pubic areas.3 Postmenopausal women appear to be at heightened risk for frontal fibrosing LPP.4

Differential diagnosis includes other types of scarring hair loss

The differential diagnosis for LPP includes discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), folliculitis decalvans, and dissecting cellulitis.1

DLE typically causes discrete, indurated lesions of central hypopigmentation (erythematous when active), along with slight atrophy and a rim of hyperpigmentation. This is in contrast to the perifollicular erythema and lack of atrophy that you’ll see in LPP. In addition, patients with DLE will have telangiectasias, while those with LPP will not.

CCCA is typically non-inflammatory, but can sometimes have symptoms such as mild itching. As the name implies, the hair loss associated with this disease starts in the central scalp and works its way centrifugally to the periphery, whereas in LPP, the alopecia can be patchy or diffuse, or can involve only the frontal scalp.2

Folliculitis decalvans is a form of scarring alopecia characterized by inflammatory perifollicular papules and pustules. Such lesions would not be observed in a patient with LPP. Bacterial culture will identify Staphylococcus aureus in most patients with untreated folliculitis decalvans.6

Dissecting cellulitis presents with tender, fluctuant nodules on the scalp that commonly suppurate and drain. The scarring hair loss that results could be mistaken for LPP, but a history of active, inflamed, nodular lesions will help to distinguish this condition from LPP.

Do a punch biopsy next to a patch of alopecia

A biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis of LPP.2 A 4 mm punch biopsy should be performed, and optimally, 2 adjacent biopsies are taken so that they can be sectioned both vertically and horizontally.2 The biopsy should be done adjacent to a patch of alopecia that still has most of the hair follicles present. This is important because a biopsy of an area of scalp completely scarred with no remaining hair follicles will not demonstrate the pathognomonic patterns of inflammation that will allow for an accurate diagnosis.

In early-stage LPP, histopathology will reveal a lichenoid interface inflammation with hypergranulosis, hyperkeratosis, and hyperacanthosis, whereas in later stages, inflammation may be minimal or absent, with fibrous tracts taking the place of destroyed hair follicles.7

Steroids have produced the best treatment outcomes

LPP has an unpredictable course.2 Currently, there is no cure, and in areas where follicle destruction has occurred, normal hair growth cannot be restored.2 Therefore, treatment should focus on preventing progression and improving symptoms. It is imperative to manage patients’ expectations when dealing with cicatricial hair loss to ensure that they understand the likely outcomes.

Topical corticosteroids alone have shown some efficacy in treating LPP, but intralesional corticosteroids and oral glucocorticosteroids have resulted in better outcomes.4 Typical doses for intralesional triamcinolone are up to 1 mL of 10 mg/mL to 40 mg/mL per treatment session, with a one-month interval between treatments. Oral steroids can be used to initially control the disease and would require approximately 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered over 3 to 4 weeks.

Adverse effects. Intralesional steroids can cause atrophy at the injection site and oral steroids can have rebound effects after an oral regimen is completed. This is in addition to other known adverse effects, such as insomnia and mood changes.4

Hydroxychloroquine has been reported to help arrest progression of, and control symptoms of, LPP with minimal adverse effects; a typical dosage is 200 mg twice a day.4 The 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors finasteride and dutasteride, which inhibit the conversion of testosterone to its more active form of dihydrotestosterone, have also shown similar efficacy.4

Finasteride can be used at a dose of 1 mg/d to 5 mg/d, and dutasteride is most effective at 0.5 to 2.5 mg/d.8 In a preliminary trial, pioglitazone (a peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptor gamma [PPAR-gamma] agonist) showed promise as a new treatment modality for LPP, perhaps because tissue expression of PPAR-gamma is decreased in LPP.9

A reasonable approach to therapy is to follow a stepwise increase from topical or intralesional corticosteroids to oral glucocorticosteroids, then to hydroxychloroquine or finasteride/dutasteride. The addition of a PPAR-gamma agonist can be added at any stage as adjunct therapy. A referral to a dermatologist may be necessary for refractory cases.

We started our patient on topical clobetasol 0.05% foam, which decreased her pruritus. However, we counseled her that we did not expect hair to regrow in the areas where she’d experienced hair loss. We continue to monitor her, and she would be a candidate for systemic therapy if the topical corticosteroid does not continue to control her disease.

CORRESPONDENCE

Simon Ritchie, MD, San Antonio Military Health System, 59MDSP/SGO7D, 2200 Berquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236; [email protected]

A 57-year-old African American woman came to our dermatology clinic to reestablish care. She had a long history of plaque psoriasis involving her trunk and extremities. More recently, she had developed progressive hair loss, which her previous physician had attributed to the psoriasis. Before this visit, our patient had been treating her psoriasis with topical clobetasol and calcipotriene.

A physical exam revealed multiple welldemarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques consistent with plaque psoriasis on her trunk and extremities. She also said her scalp was itchy, and we noted significant cicatricial (scarring) alopecia of the scalp, with faint perifollicular erythema, that was predominantly affecting the frontotemporal region (FIGURE). We performed a scalp biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen planopilaris

We suspected that this was not simply a case of plaque psoriasis because psoriasis of the scalp only causes non-cicatricial alopecia.1 Biopsy results confirmed that while the patient did have plaque psoriasis on her scalp, there was also evidence of peri-infundibular fibrosis and inflammation at the junction of the epidermis and dermis along the follicular epithelium. These 2 findings are pathognomonic for lichen planopilaris (LPP).

An uncommon diagnosis

Although its exact incidence and prevalence are unknown, LPP appears to be uncommon.2 The condition typically presents in adults ages 25 to 70, and is more common in women than in men.2 There is no known association between LPP and psoriasis.

Clinically, LPP manifests as cicatricial hair loss, often in a band-like fashion that can coalesce into larger, reticulated patterns.1 In addition to the scalp, LPP can affect other hair-bearing areas, such as the eyelids (lashes, brows), body, axillae, or pubic region.3,4 It is typically accompanied by burning and itching, and commonly presents with perifollicular erythema.1

LPP is thought to be the result of an immune-mediated lymphocytic inflammatory process that produces follicular hyperkeratosis, surrounding erythema, overlying scale, and, eventually, fibrosis and loss of the hair follicle.3,5

LPP has 3 variants: classic LPP, which typically affects the vertex and parietal areas of the scalp; frontal fibrosing alopecia, which is characterized by frontotemporal hair loss in a band-like pattern (as in our patient’s case); and Graham-Little syndrome, which can include cicatricial alopecia of the scalp and non-cicatricial alopecia of the axillary and pubic areas.3 Postmenopausal women appear to be at heightened risk for frontal fibrosing LPP.4

Differential diagnosis includes other types of scarring hair loss

The differential diagnosis for LPP includes discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), folliculitis decalvans, and dissecting cellulitis.1

DLE typically causes discrete, indurated lesions of central hypopigmentation (erythematous when active), along with slight atrophy and a rim of hyperpigmentation. This is in contrast to the perifollicular erythema and lack of atrophy that you’ll see in LPP. In addition, patients with DLE will have telangiectasias, while those with LPP will not.

CCCA is typically non-inflammatory, but can sometimes have symptoms such as mild itching. As the name implies, the hair loss associated with this disease starts in the central scalp and works its way centrifugally to the periphery, whereas in LPP, the alopecia can be patchy or diffuse, or can involve only the frontal scalp.2

Folliculitis decalvans is a form of scarring alopecia characterized by inflammatory perifollicular papules and pustules. Such lesions would not be observed in a patient with LPP. Bacterial culture will identify Staphylococcus aureus in most patients with untreated folliculitis decalvans.6

Dissecting cellulitis presents with tender, fluctuant nodules on the scalp that commonly suppurate and drain. The scarring hair loss that results could be mistaken for LPP, but a history of active, inflamed, nodular lesions will help to distinguish this condition from LPP.

Do a punch biopsy next to a patch of alopecia

A biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis of LPP.2 A 4 mm punch biopsy should be performed, and optimally, 2 adjacent biopsies are taken so that they can be sectioned both vertically and horizontally.2 The biopsy should be done adjacent to a patch of alopecia that still has most of the hair follicles present. This is important because a biopsy of an area of scalp completely scarred with no remaining hair follicles will not demonstrate the pathognomonic patterns of inflammation that will allow for an accurate diagnosis.

In early-stage LPP, histopathology will reveal a lichenoid interface inflammation with hypergranulosis, hyperkeratosis, and hyperacanthosis, whereas in later stages, inflammation may be minimal or absent, with fibrous tracts taking the place of destroyed hair follicles.7

Steroids have produced the best treatment outcomes

LPP has an unpredictable course.2 Currently, there is no cure, and in areas where follicle destruction has occurred, normal hair growth cannot be restored.2 Therefore, treatment should focus on preventing progression and improving symptoms. It is imperative to manage patients’ expectations when dealing with cicatricial hair loss to ensure that they understand the likely outcomes.

Topical corticosteroids alone have shown some efficacy in treating LPP, but intralesional corticosteroids and oral glucocorticosteroids have resulted in better outcomes.4 Typical doses for intralesional triamcinolone are up to 1 mL of 10 mg/mL to 40 mg/mL per treatment session, with a one-month interval between treatments. Oral steroids can be used to initially control the disease and would require approximately 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered over 3 to 4 weeks.

Adverse effects. Intralesional steroids can cause atrophy at the injection site and oral steroids can have rebound effects after an oral regimen is completed. This is in addition to other known adverse effects, such as insomnia and mood changes.4

Hydroxychloroquine has been reported to help arrest progression of, and control symptoms of, LPP with minimal adverse effects; a typical dosage is 200 mg twice a day.4 The 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors finasteride and dutasteride, which inhibit the conversion of testosterone to its more active form of dihydrotestosterone, have also shown similar efficacy.4

Finasteride can be used at a dose of 1 mg/d to 5 mg/d, and dutasteride is most effective at 0.5 to 2.5 mg/d.8 In a preliminary trial, pioglitazone (a peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptor gamma [PPAR-gamma] agonist) showed promise as a new treatment modality for LPP, perhaps because tissue expression of PPAR-gamma is decreased in LPP.9

A reasonable approach to therapy is to follow a stepwise increase from topical or intralesional corticosteroids to oral glucocorticosteroids, then to hydroxychloroquine or finasteride/dutasteride. The addition of a PPAR-gamma agonist can be added at any stage as adjunct therapy. A referral to a dermatologist may be necessary for refractory cases.

We started our patient on topical clobetasol 0.05% foam, which decreased her pruritus. However, we counseled her that we did not expect hair to regrow in the areas where she’d experienced hair loss. We continue to monitor her, and she would be a candidate for systemic therapy if the topical corticosteroid does not continue to control her disease.

CORRESPONDENCE

Simon Ritchie, MD, San Antonio Military Health System, 59MDSP/SGO7D, 2200 Berquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236; [email protected]

1. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby; 2004:214,252,841,855-856,860-861.

2. Shapiro J, Otberg N. Lichen planopilaris. UpToDate Web site. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/lichen-planopilaris. Accessed June 2, 2015.

3. Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcón C, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670-678.

4. Ross EK, Tan E, Shapiro J. Update on primary cicatricial alopecias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1-37.

5. Mobini N, Tam S, Kamino H. Possible role of the bulge region in the pathogenesis of inflammatory scarring alopecia: lichen planopilaris as the prototype. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:675-679.

6. Otberg N, Kang H, Alzolibani AA, et al. Folliculitis decalvans. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:238-244.

7. Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:3-10.

8. Olsen EA, Hordinsky M, Whiting D, et al. The importance of dual 5alpha-reductase inhibition in the treatment of male pattern hair loss: results of a randomized placebo-controlled study of dutasteride versus finasteride. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:1014-1023.

9. Baibergenova A, Walsh S. Use of pioglitazone in patients with lichen planopilaris. J Cutan Med Surg. 2012;16:97-100.

1. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby; 2004:214,252,841,855-856,860-861.

2. Shapiro J, Otberg N. Lichen planopilaris. UpToDate Web site. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/lichen-planopilaris. Accessed June 2, 2015.

3. Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcón C, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670-678.

4. Ross EK, Tan E, Shapiro J. Update on primary cicatricial alopecias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1-37.

5. Mobini N, Tam S, Kamino H. Possible role of the bulge region in the pathogenesis of inflammatory scarring alopecia: lichen planopilaris as the prototype. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:675-679.

6. Otberg N, Kang H, Alzolibani AA, et al. Folliculitis decalvans. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:238-244.

7. Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:3-10.

8. Olsen EA, Hordinsky M, Whiting D, et al. The importance of dual 5alpha-reductase inhibition in the treatment of male pattern hair loss: results of a randomized placebo-controlled study of dutasteride versus finasteride. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:1014-1023.

9. Baibergenova A, Walsh S. Use of pioglitazone in patients with lichen planopilaris. J Cutan Med Surg. 2012;16:97-100.

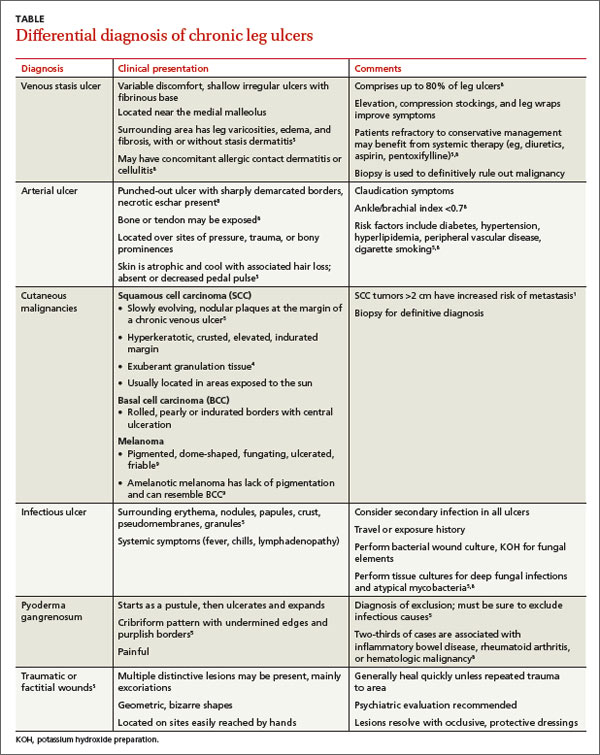

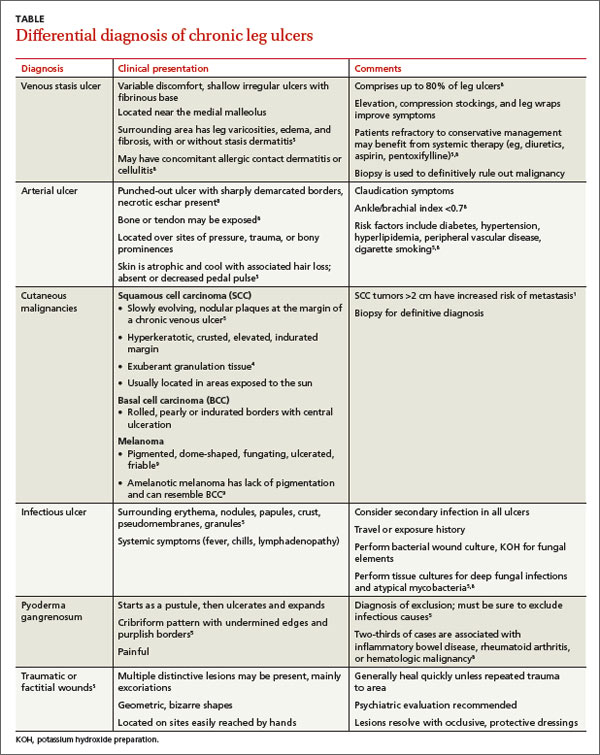

Non-healing, non-tender ulcer on shin

A 63-year-old morbidly obese man presented to our clinic with a non-healing, slowly growing, painless ulcer on his right shin that he’d had for one year. It was not actively bleeding or draining, but the scab had come off one month earlier and the wound did not close. The patient denied any trauma to the area or foreign travel. Bacitracin and triamcinolone creams hadn’t helped.

Our patient’s medical history included diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and worsening venous insufficiency. He was not currently using compression stockings, but they had helped him in the past.

On examination, we noted a 3 x 3.5 cm well-demarcated, somewhat geometric, clean-based ulceration on the patient’s right medial shin (FIGURE 1A). There was no significant erythema, purulence, tenderness, warmth, or drainage of the ulcer. The base had seemingly normal granulation tissue. Woody induration, verrucous plaques, and confluent erythematous, violaceous, indurated patches were adjacent to the ulcer (FIGURE 1B). The patient also had severe pitting edema on his lower legs.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infiltrative basal cell carcinoma

In addition to our patient’s history of venous insufficiency, he’d also had a melanoma removed from his right shoulder 6 years earlier, and a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) removed from his upper back 2 years earlier. The chronic, non-healing nature of the ulcer prompted us to perform a punch biopsy, which revealed infiltrative BCC. We also did a wound culture, which showed a secondary infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The verrucous plaques next to the ulcer were the result of chronic venous stasis and lymphedema.

BCC is the most common type of cancer, estimated to comprise 80% of all skin cancers.1 It typically presents on the head and neck, but can occur in other locations. Eight percent of BCCs occur on the legs.2,3 Lower extremity BCC is more common in women, likely due to increased ultraviolet radiation exposure.2,4

BCC presents as erythematous and pearly macules, papules, nodules, ulcers, or scars, and can be pigmented. It may appear as a crusted ulcer (known as a “rodent ulcer”) with a rolled, translucent border and telangiectases.5 There are 5 major histologic subtypes of BCC: nodular, micronodular, superficial, morpheaform, and infiltrative.1,5 Infiltrative BCCs are an invasive subtype1,5 and may be more commonly associated with severe venous stasis,3 as was the case with our patient.

Although considered uncommon, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and BCC have been discovered in chronic leg ulcers.4,6 In fact, one report suggests that as many as 10% of chronic leg ulcers are malignant (31% BCC, 56% SCC).7 Thus, it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for malignancy in chronic leg ulcers.

Ulcerating BCC can mimic other types of leg ulcers

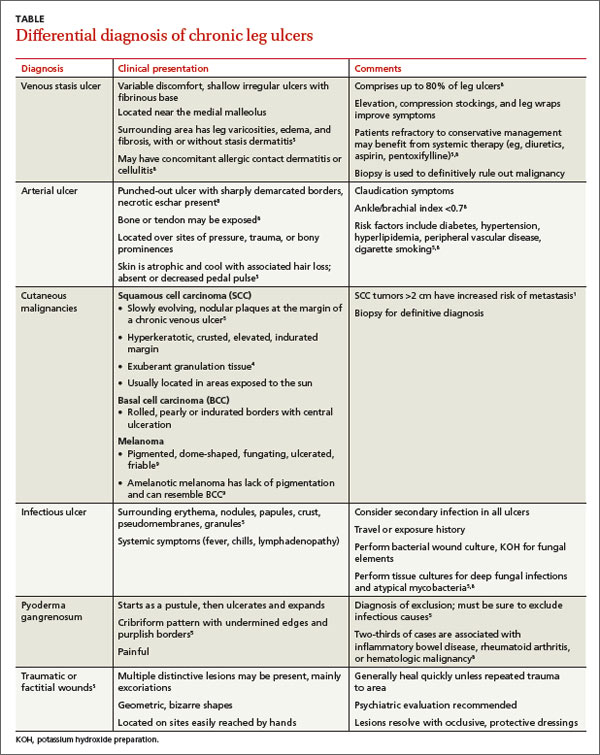

The differential diagnosis of a chronic leg ulcer includes venous or arterial ulcers, malignancies (SCC, BCC, lymphoma, melanoma), infectious ulcers (bacterial, deep fungal), pyoderma gangrenosum, and traumatic or factitial wounds (TABLE).1,4,5,8,9

Consider biopsy for ulcers that don't respond to treatment

The diagnosis of BCC in a leg ulcer is confirmed histologically. A punch or incisional biopsy should be taken at the edge of the ulcer, including the base.5,6 (For a Watch & Learn video that demonstrates how to perform a punch biopsy, go to http://bit.ly/punch_biopsy.) Providers may be concerned that biopsies could worsen a chronic wound; however, biopsy sites usually heal with no substantial complications.2,6,7 There are no guidelines on when to biopsy an ulcer, but it is reasonable to biopsy a leg ulcer that has not responded to 3 months of conservative treatment.2,7

Factors associated with malignancy in chronic leg ulcers include older age, abnormal excessive granulation tissue at wound edges, high clinical suspicion of cancer, and number of previous biopsies.7 The size and duration of the ulcer do not directly correlate with malignancy.7 The threshold for performing a diagnostic biopsy in a chronic leg ulcer should be lower for a patient who has any of the risk factors noted above. Be aware that ulcerating skin cancers may lack the classic appearance of typical skin cancers.6

For most BCCs, surgical excision will be required

Each BCC must be thoroughly evaluated for size, location, and histologic subtype. Surgical excision is the preferred treatment in most cases.5 Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery include skin cancers with aggressive histologic subtypes, such as infiltrative BCC, and tumors larger than 2 cm that are located on the extremities.1,5 Due to the limited amount of excess skin on the lower leg, skin flaps or grafts may be required.

Electrodessication and curettage, topical therapy with 5% imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil, and cryotherapy are reserved for certain low-risk superficial and nodular BCCs.1,5 Radiation therapy is an option for tumors that are not amenable to surgery. Treatment is tailored to the patient’s needs based on age, medical history, and the characteristics of the skin cancer.

Inadequate treatment of BCCs can result in recurrences, which may appear 4 to 12 months after treatment.5 Close followup with regular full body skin exams is indicated.

Our patient was treated with Bactrim DS (800 mg sulfamethoxazole and 160 mg trimethoprim) one tablet PO BID for 10 days and acetic acid soaks for the MRSA. While it was clear that the patient needed Mohs surgery, it was important to first address his lower extremity edema. He was evaluated by a vascular surgeon and resumed using compression stockings regularly.

The patient then underwent Mohs surgery.

After 2 stages of the surgery, the patient’s ulcer healed partially by secondary intention. After 5 months, the ulcer was covered with a split-thickness skin graft. Nine months after diagnosis, the patient had no clinical recurrence.

Physicians subsequently identified 2 BCCs on his face and scalp that were also treated with Mohs surgery. Our patient continues to have regular skin examinations.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jane Hwang, MD, Capt, USAF, MC, Kunsan Air Base, PSC 2 Box 205, APO, AP 96264; [email protected]

1. Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of Basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

2. Phillips TJ, Salman SM, Rogers GS. Nonhealing leg ulcers: a manifestation of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25;47-49.

3. Lutz ME, Davis MD, Otley CC. Infiltrating basal cell carcinoma in the setting of a venous ulcer. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:519-520.

4. Jankovic A, Binic I, Ljubenovic M. Basal cell carcinoma is not granulation tissue in the venous leg ulcer. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2008;7:182-184.

5. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Chapter 29. Epidermal nevi, neoplasms, and cysts. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2011.

6. Yang D, Morrison BD, Vandongen YK, et al. Malignancy in chronic leg ulcers. Med J Aust. 1996;164:718-720.

7. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al; Angio-Dermatology Group Of The French Society Of Dermatology. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers: the value of systematic wound biopsies: a prospective, multicenter, cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

8. Valencia IC, Falabella A, Kirsner RS, et al. Chronic venous insufficiency and venous leg ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:401-421.

9. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Chapter 30. Melanocytic nevi and neoplasms. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2011.

A 63-year-old morbidly obese man presented to our clinic with a non-healing, slowly growing, painless ulcer on his right shin that he’d had for one year. It was not actively bleeding or draining, but the scab had come off one month earlier and the wound did not close. The patient denied any trauma to the area or foreign travel. Bacitracin and triamcinolone creams hadn’t helped.

Our patient’s medical history included diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and worsening venous insufficiency. He was not currently using compression stockings, but they had helped him in the past.

On examination, we noted a 3 x 3.5 cm well-demarcated, somewhat geometric, clean-based ulceration on the patient’s right medial shin (FIGURE 1A). There was no significant erythema, purulence, tenderness, warmth, or drainage of the ulcer. The base had seemingly normal granulation tissue. Woody induration, verrucous plaques, and confluent erythematous, violaceous, indurated patches were adjacent to the ulcer (FIGURE 1B). The patient also had severe pitting edema on his lower legs.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infiltrative basal cell carcinoma

In addition to our patient’s history of venous insufficiency, he’d also had a melanoma removed from his right shoulder 6 years earlier, and a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) removed from his upper back 2 years earlier. The chronic, non-healing nature of the ulcer prompted us to perform a punch biopsy, which revealed infiltrative BCC. We also did a wound culture, which showed a secondary infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The verrucous plaques next to the ulcer were the result of chronic venous stasis and lymphedema.

BCC is the most common type of cancer, estimated to comprise 80% of all skin cancers.1 It typically presents on the head and neck, but can occur in other locations. Eight percent of BCCs occur on the legs.2,3 Lower extremity BCC is more common in women, likely due to increased ultraviolet radiation exposure.2,4

BCC presents as erythematous and pearly macules, papules, nodules, ulcers, or scars, and can be pigmented. It may appear as a crusted ulcer (known as a “rodent ulcer”) with a rolled, translucent border and telangiectases.5 There are 5 major histologic subtypes of BCC: nodular, micronodular, superficial, morpheaform, and infiltrative.1,5 Infiltrative BCCs are an invasive subtype1,5 and may be more commonly associated with severe venous stasis,3 as was the case with our patient.

Although considered uncommon, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and BCC have been discovered in chronic leg ulcers.4,6 In fact, one report suggests that as many as 10% of chronic leg ulcers are malignant (31% BCC, 56% SCC).7 Thus, it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for malignancy in chronic leg ulcers.

Ulcerating BCC can mimic other types of leg ulcers

The differential diagnosis of a chronic leg ulcer includes venous or arterial ulcers, malignancies (SCC, BCC, lymphoma, melanoma), infectious ulcers (bacterial, deep fungal), pyoderma gangrenosum, and traumatic or factitial wounds (TABLE).1,4,5,8,9

Consider biopsy for ulcers that don't respond to treatment

The diagnosis of BCC in a leg ulcer is confirmed histologically. A punch or incisional biopsy should be taken at the edge of the ulcer, including the base.5,6 (For a Watch & Learn video that demonstrates how to perform a punch biopsy, go to http://bit.ly/punch_biopsy.) Providers may be concerned that biopsies could worsen a chronic wound; however, biopsy sites usually heal with no substantial complications.2,6,7 There are no guidelines on when to biopsy an ulcer, but it is reasonable to biopsy a leg ulcer that has not responded to 3 months of conservative treatment.2,7

Factors associated with malignancy in chronic leg ulcers include older age, abnormal excessive granulation tissue at wound edges, high clinical suspicion of cancer, and number of previous biopsies.7 The size and duration of the ulcer do not directly correlate with malignancy.7 The threshold for performing a diagnostic biopsy in a chronic leg ulcer should be lower for a patient who has any of the risk factors noted above. Be aware that ulcerating skin cancers may lack the classic appearance of typical skin cancers.6

For most BCCs, surgical excision will be required

Each BCC must be thoroughly evaluated for size, location, and histologic subtype. Surgical excision is the preferred treatment in most cases.5 Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery include skin cancers with aggressive histologic subtypes, such as infiltrative BCC, and tumors larger than 2 cm that are located on the extremities.1,5 Due to the limited amount of excess skin on the lower leg, skin flaps or grafts may be required.

Electrodessication and curettage, topical therapy with 5% imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil, and cryotherapy are reserved for certain low-risk superficial and nodular BCCs.1,5 Radiation therapy is an option for tumors that are not amenable to surgery. Treatment is tailored to the patient’s needs based on age, medical history, and the characteristics of the skin cancer.

Inadequate treatment of BCCs can result in recurrences, which may appear 4 to 12 months after treatment.5 Close followup with regular full body skin exams is indicated.

Our patient was treated with Bactrim DS (800 mg sulfamethoxazole and 160 mg trimethoprim) one tablet PO BID for 10 days and acetic acid soaks for the MRSA. While it was clear that the patient needed Mohs surgery, it was important to first address his lower extremity edema. He was evaluated by a vascular surgeon and resumed using compression stockings regularly.

The patient then underwent Mohs surgery.

After 2 stages of the surgery, the patient’s ulcer healed partially by secondary intention. After 5 months, the ulcer was covered with a split-thickness skin graft. Nine months after diagnosis, the patient had no clinical recurrence.

Physicians subsequently identified 2 BCCs on his face and scalp that were also treated with Mohs surgery. Our patient continues to have regular skin examinations.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jane Hwang, MD, Capt, USAF, MC, Kunsan Air Base, PSC 2 Box 205, APO, AP 96264; [email protected]

A 63-year-old morbidly obese man presented to our clinic with a non-healing, slowly growing, painless ulcer on his right shin that he’d had for one year. It was not actively bleeding or draining, but the scab had come off one month earlier and the wound did not close. The patient denied any trauma to the area or foreign travel. Bacitracin and triamcinolone creams hadn’t helped.

Our patient’s medical history included diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and worsening venous insufficiency. He was not currently using compression stockings, but they had helped him in the past.

On examination, we noted a 3 x 3.5 cm well-demarcated, somewhat geometric, clean-based ulceration on the patient’s right medial shin (FIGURE 1A). There was no significant erythema, purulence, tenderness, warmth, or drainage of the ulcer. The base had seemingly normal granulation tissue. Woody induration, verrucous plaques, and confluent erythematous, violaceous, indurated patches were adjacent to the ulcer (FIGURE 1B). The patient also had severe pitting edema on his lower legs.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infiltrative basal cell carcinoma

In addition to our patient’s history of venous insufficiency, he’d also had a melanoma removed from his right shoulder 6 years earlier, and a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) removed from his upper back 2 years earlier. The chronic, non-healing nature of the ulcer prompted us to perform a punch biopsy, which revealed infiltrative BCC. We also did a wound culture, which showed a secondary infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The verrucous plaques next to the ulcer were the result of chronic venous stasis and lymphedema.

BCC is the most common type of cancer, estimated to comprise 80% of all skin cancers.1 It typically presents on the head and neck, but can occur in other locations. Eight percent of BCCs occur on the legs.2,3 Lower extremity BCC is more common in women, likely due to increased ultraviolet radiation exposure.2,4

BCC presents as erythematous and pearly macules, papules, nodules, ulcers, or scars, and can be pigmented. It may appear as a crusted ulcer (known as a “rodent ulcer”) with a rolled, translucent border and telangiectases.5 There are 5 major histologic subtypes of BCC: nodular, micronodular, superficial, morpheaform, and infiltrative.1,5 Infiltrative BCCs are an invasive subtype1,5 and may be more commonly associated with severe venous stasis,3 as was the case with our patient.

Although considered uncommon, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and BCC have been discovered in chronic leg ulcers.4,6 In fact, one report suggests that as many as 10% of chronic leg ulcers are malignant (31% BCC, 56% SCC).7 Thus, it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for malignancy in chronic leg ulcers.

Ulcerating BCC can mimic other types of leg ulcers

The differential diagnosis of a chronic leg ulcer includes venous or arterial ulcers, malignancies (SCC, BCC, lymphoma, melanoma), infectious ulcers (bacterial, deep fungal), pyoderma gangrenosum, and traumatic or factitial wounds (TABLE).1,4,5,8,9

Consider biopsy for ulcers that don't respond to treatment

The diagnosis of BCC in a leg ulcer is confirmed histologically. A punch or incisional biopsy should be taken at the edge of the ulcer, including the base.5,6 (For a Watch & Learn video that demonstrates how to perform a punch biopsy, go to http://bit.ly/punch_biopsy.) Providers may be concerned that biopsies could worsen a chronic wound; however, biopsy sites usually heal with no substantial complications.2,6,7 There are no guidelines on when to biopsy an ulcer, but it is reasonable to biopsy a leg ulcer that has not responded to 3 months of conservative treatment.2,7

Factors associated with malignancy in chronic leg ulcers include older age, abnormal excessive granulation tissue at wound edges, high clinical suspicion of cancer, and number of previous biopsies.7 The size and duration of the ulcer do not directly correlate with malignancy.7 The threshold for performing a diagnostic biopsy in a chronic leg ulcer should be lower for a patient who has any of the risk factors noted above. Be aware that ulcerating skin cancers may lack the classic appearance of typical skin cancers.6

For most BCCs, surgical excision will be required

Each BCC must be thoroughly evaluated for size, location, and histologic subtype. Surgical excision is the preferred treatment in most cases.5 Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery include skin cancers with aggressive histologic subtypes, such as infiltrative BCC, and tumors larger than 2 cm that are located on the extremities.1,5 Due to the limited amount of excess skin on the lower leg, skin flaps or grafts may be required.

Electrodessication and curettage, topical therapy with 5% imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil, and cryotherapy are reserved for certain low-risk superficial and nodular BCCs.1,5 Radiation therapy is an option for tumors that are not amenable to surgery. Treatment is tailored to the patient’s needs based on age, medical history, and the characteristics of the skin cancer.

Inadequate treatment of BCCs can result in recurrences, which may appear 4 to 12 months after treatment.5 Close followup with regular full body skin exams is indicated.

Our patient was treated with Bactrim DS (800 mg sulfamethoxazole and 160 mg trimethoprim) one tablet PO BID for 10 days and acetic acid soaks for the MRSA. While it was clear that the patient needed Mohs surgery, it was important to first address his lower extremity edema. He was evaluated by a vascular surgeon and resumed using compression stockings regularly.

The patient then underwent Mohs surgery.

After 2 stages of the surgery, the patient’s ulcer healed partially by secondary intention. After 5 months, the ulcer was covered with a split-thickness skin graft. Nine months after diagnosis, the patient had no clinical recurrence.

Physicians subsequently identified 2 BCCs on his face and scalp that were also treated with Mohs surgery. Our patient continues to have regular skin examinations.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jane Hwang, MD, Capt, USAF, MC, Kunsan Air Base, PSC 2 Box 205, APO, AP 96264; [email protected]

1. Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of Basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

2. Phillips TJ, Salman SM, Rogers GS. Nonhealing leg ulcers: a manifestation of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25;47-49.

3. Lutz ME, Davis MD, Otley CC. Infiltrating basal cell carcinoma in the setting of a venous ulcer. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:519-520.

4. Jankovic A, Binic I, Ljubenovic M. Basal cell carcinoma is not granulation tissue in the venous leg ulcer. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2008;7:182-184.

5. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Chapter 29. Epidermal nevi, neoplasms, and cysts. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2011.

6. Yang D, Morrison BD, Vandongen YK, et al. Malignancy in chronic leg ulcers. Med J Aust. 1996;164:718-720.

7. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al; Angio-Dermatology Group Of The French Society Of Dermatology. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers: the value of systematic wound biopsies: a prospective, multicenter, cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

8. Valencia IC, Falabella A, Kirsner RS, et al. Chronic venous insufficiency and venous leg ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:401-421.

9. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Chapter 30. Melanocytic nevi and neoplasms. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2011.

1. Firnhaber JM. Diagnosis and treatment of Basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:161-168.

2. Phillips TJ, Salman SM, Rogers GS. Nonhealing leg ulcers: a manifestation of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25;47-49.

3. Lutz ME, Davis MD, Otley CC. Infiltrating basal cell carcinoma in the setting of a venous ulcer. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:519-520.

4. Jankovic A, Binic I, Ljubenovic M. Basal cell carcinoma is not granulation tissue in the venous leg ulcer. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2008;7:182-184.

5. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Chapter 29. Epidermal nevi, neoplasms, and cysts. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2011.

6. Yang D, Morrison BD, Vandongen YK, et al. Malignancy in chronic leg ulcers. Med J Aust. 1996;164:718-720.

7. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al; Angio-Dermatology Group Of The French Society Of Dermatology. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers: the value of systematic wound biopsies: a prospective, multicenter, cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

8. Valencia IC, Falabella A, Kirsner RS, et al. Chronic venous insufficiency and venous leg ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:401-421.

9. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Chapter 30. Melanocytic nevi and neoplasms. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2011.

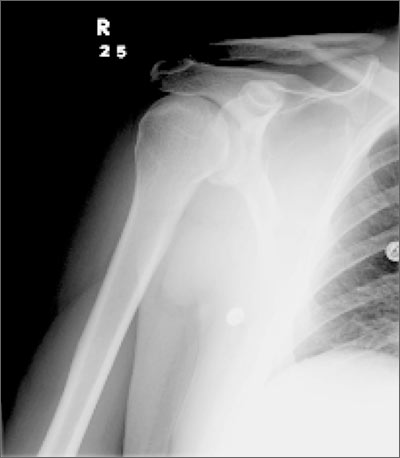

Hip pain prohibits walking

This patient had a transcervical left femoral neck fracture. The radiologist noted that there was varus angulation and superior offset of the distal fracture fragment. The FP called the orthopedic surgeon, who admitted the patient to the hospital for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis and preparation for surgery. After months of rehabilitation, the patient was able to walk again. A dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan showed osteoporosis, and treatment was initiated.

Approximately 300,000 hip fractures occur every year in the United States, and 70% to 80% of them are in women. The average age at fracture is 70 to 80 years, but the risk increases with age. Half of patients with a hip fracture have osteoporosis. Other risk factors include: postural instability and/or quadriceps weakness, history of falls, prior hip fracture, dementia, tobacco use, physical inactivity, impaired vision, and alcohol use.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley, H. Hip fracture. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:615-618.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

This patient had a transcervical left femoral neck fracture. The radiologist noted that there was varus angulation and superior offset of the distal fracture fragment. The FP called the orthopedic surgeon, who admitted the patient to the hospital for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis and preparation for surgery. After months of rehabilitation, the patient was able to walk again. A dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan showed osteoporosis, and treatment was initiated.

Approximately 300,000 hip fractures occur every year in the United States, and 70% to 80% of them are in women. The average age at fracture is 70 to 80 years, but the risk increases with age. Half of patients with a hip fracture have osteoporosis. Other risk factors include: postural instability and/or quadriceps weakness, history of falls, prior hip fracture, dementia, tobacco use, physical inactivity, impaired vision, and alcohol use.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley, H. Hip fracture. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:615-618.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

This patient had a transcervical left femoral neck fracture. The radiologist noted that there was varus angulation and superior offset of the distal fracture fragment. The FP called the orthopedic surgeon, who admitted the patient to the hospital for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis and preparation for surgery. After months of rehabilitation, the patient was able to walk again. A dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan showed osteoporosis, and treatment was initiated.

Approximately 300,000 hip fractures occur every year in the United States, and 70% to 80% of them are in women. The average age at fracture is 70 to 80 years, but the risk increases with age. Half of patients with a hip fracture have osteoporosis. Other risk factors include: postural instability and/or quadriceps weakness, history of falls, prior hip fracture, dementia, tobacco use, physical inactivity, impaired vision, and alcohol use.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley, H. Hip fracture. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:615-618.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Twisted ankle

The x-ray revealed that the patient had a nondisplaced fracture at the base of the fifth metatarsal (also known as a dancer’s fracture). Most metatarsal fractures involve the fifth metatarsal and include avulsion fractures at the base, as seen in this patient. Fractures of the first through fourth metatarsals are less common. Diagnosis is based on the mechanism of injury/type of overuse activity and the radiographic appearance.

Treatment depends on the type of fracture. Most metatarsal fractures at the base have a good prognosis; however Jones fractures—an acute diaphyseal fracture of the fifth metatarsal—have a high rate of non-union.