User login

Purpuric lesions on extremities

This patient was given a diagnosis of Churg-Strauss syndrome. A CSS diagnosis can be made if 4 of the following 6 criteria are met: (1) asthma, (2) eosinophilia >10% on a differential white blood cell count (WBC), (3) paranasal sinus abnormalities, (4) a transient pulmonary infiltrate detected on chest x-ray, (5) mono- or polyneuropathy, and (6) a biopsy specimen showing extravascular accumulation of eosinophils.

This patient met 4 of the 6 criteria. She had asthma and a punch biopsy showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with prominent tissue eosinophilia. Lab studies showed an elevated WBC of 12,300/mcL and eosinophilia of 40%. A serologic test for perinuclear pattern antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) was positive. Radiography of the chest showed transient pulmonary infiltrates.

CSS—also known as allergic granulomatosis and angiitis—is a rare multisystemic vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels characterized by asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis, and prominent peripheral blood eosinophilia. The mean diagnosis age is 50 years and any organ system can be affected, although the lungs and skin are most commonly involved.

Three distinct phases of CSS have been described. The first is the prodromal or allergic phase, which is characterized by the onset of asthma later in life in patients with no family history of atopy. The eosinophilic phase is characterized by peripheral blood eosinophilia and eosinophilic infiltration of multiple organs. The vasculitis phase is characterized by life-threatening systemic vasculitis of the small and medium vessels that is often associated with vascular and extravascular granulomatosis. One-half to two-thirds of patients with CSS have cutaneous manifestations that typically present in the vasculitis phase.

Systemic corticosteroids (prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day) are the primary treatment for patients with CSS; most patients improve dramatically with therapy. Adjunctive therapy with immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate (10-15 mg per week), chlorambucil, or azathioprine may be needed if a patient does not respond adequately to steroids alone.

In this case, the patient was prescribed prednisone 1 mg/kg/d. Her skin lesions resolved and subsequent laboratory tests normalized, including her eosinophil counts. Prednisone therapy was gradually tapered over several months to attain the lowest dose required for control of symptoms—in this case, 5 mg/d.

Adapted from: Abadi R, Dakik H, Abbas O. Purpuric lesions in an elderly woman. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:159-161.

This patient was given a diagnosis of Churg-Strauss syndrome. A CSS diagnosis can be made if 4 of the following 6 criteria are met: (1) asthma, (2) eosinophilia >10% on a differential white blood cell count (WBC), (3) paranasal sinus abnormalities, (4) a transient pulmonary infiltrate detected on chest x-ray, (5) mono- or polyneuropathy, and (6) a biopsy specimen showing extravascular accumulation of eosinophils.

This patient met 4 of the 6 criteria. She had asthma and a punch biopsy showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with prominent tissue eosinophilia. Lab studies showed an elevated WBC of 12,300/mcL and eosinophilia of 40%. A serologic test for perinuclear pattern antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) was positive. Radiography of the chest showed transient pulmonary infiltrates.

CSS—also known as allergic granulomatosis and angiitis—is a rare multisystemic vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels characterized by asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis, and prominent peripheral blood eosinophilia. The mean diagnosis age is 50 years and any organ system can be affected, although the lungs and skin are most commonly involved.

Three distinct phases of CSS have been described. The first is the prodromal or allergic phase, which is characterized by the onset of asthma later in life in patients with no family history of atopy. The eosinophilic phase is characterized by peripheral blood eosinophilia and eosinophilic infiltration of multiple organs. The vasculitis phase is characterized by life-threatening systemic vasculitis of the small and medium vessels that is often associated with vascular and extravascular granulomatosis. One-half to two-thirds of patients with CSS have cutaneous manifestations that typically present in the vasculitis phase.

Systemic corticosteroids (prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day) are the primary treatment for patients with CSS; most patients improve dramatically with therapy. Adjunctive therapy with immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate (10-15 mg per week), chlorambucil, or azathioprine may be needed if a patient does not respond adequately to steroids alone.

In this case, the patient was prescribed prednisone 1 mg/kg/d. Her skin lesions resolved and subsequent laboratory tests normalized, including her eosinophil counts. Prednisone therapy was gradually tapered over several months to attain the lowest dose required for control of symptoms—in this case, 5 mg/d.

Adapted from: Abadi R, Dakik H, Abbas O. Purpuric lesions in an elderly woman. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:159-161.

This patient was given a diagnosis of Churg-Strauss syndrome. A CSS diagnosis can be made if 4 of the following 6 criteria are met: (1) asthma, (2) eosinophilia >10% on a differential white blood cell count (WBC), (3) paranasal sinus abnormalities, (4) a transient pulmonary infiltrate detected on chest x-ray, (5) mono- or polyneuropathy, and (6) a biopsy specimen showing extravascular accumulation of eosinophils.

This patient met 4 of the 6 criteria. She had asthma and a punch biopsy showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with prominent tissue eosinophilia. Lab studies showed an elevated WBC of 12,300/mcL and eosinophilia of 40%. A serologic test for perinuclear pattern antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) was positive. Radiography of the chest showed transient pulmonary infiltrates.

CSS—also known as allergic granulomatosis and angiitis—is a rare multisystemic vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels characterized by asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis, and prominent peripheral blood eosinophilia. The mean diagnosis age is 50 years and any organ system can be affected, although the lungs and skin are most commonly involved.

Three distinct phases of CSS have been described. The first is the prodromal or allergic phase, which is characterized by the onset of asthma later in life in patients with no family history of atopy. The eosinophilic phase is characterized by peripheral blood eosinophilia and eosinophilic infiltration of multiple organs. The vasculitis phase is characterized by life-threatening systemic vasculitis of the small and medium vessels that is often associated with vascular and extravascular granulomatosis. One-half to two-thirds of patients with CSS have cutaneous manifestations that typically present in the vasculitis phase.

Systemic corticosteroids (prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day) are the primary treatment for patients with CSS; most patients improve dramatically with therapy. Adjunctive therapy with immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate (10-15 mg per week), chlorambucil, or azathioprine may be needed if a patient does not respond adequately to steroids alone.

In this case, the patient was prescribed prednisone 1 mg/kg/d. Her skin lesions resolved and subsequent laboratory tests normalized, including her eosinophil counts. Prednisone therapy was gradually tapered over several months to attain the lowest dose required for control of symptoms—in this case, 5 mg/d.

Adapted from: Abadi R, Dakik H, Abbas O. Purpuric lesions in an elderly woman. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:159-161.

Itchy rash on back

The FP was concerned that this could be a drug eruption but didn’t want to stop the ACE inhibitor because the patient had hypertension that was finally under control. Therefore, she performed a punch biopsy around one of the red papules for a definitive diagnosis. She also prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream and oral hydroxyzine for the pruritus while awaiting the diagnosis. The punch biopsy revealed that the patient had transient acantholytic dermatosis, also known as Grover’s disease.

Grover’s disease mostly affects older men (>50 years), but occasionally occurs in women and younger people. Pruritus is a common complaint and some sufferers feel that sweating makes it worse. The cause is unknown and the prognosis is variable.

Grover’s disease is transient for some, but it can also be chronic or relapsing. As it is a relatively rare condition, there are few high-quality studies to guide treatment. Some of the treatments described in the literature include topical steroids, oral antihistamines, oral antifungals, oral antibiotics, oral retinoids, moisturizers, and phototherapy.

When this particular patient returned for follow-up, he noted about a 50% improvement in his symptoms and the red papules were less red. The patient was referred to Dermatology and told to continue the triamcinolone cream until he could see a dermatologist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Hunter-Anderson K. Folliculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:680-685.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP was concerned that this could be a drug eruption but didn’t want to stop the ACE inhibitor because the patient had hypertension that was finally under control. Therefore, she performed a punch biopsy around one of the red papules for a definitive diagnosis. She also prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream and oral hydroxyzine for the pruritus while awaiting the diagnosis. The punch biopsy revealed that the patient had transient acantholytic dermatosis, also known as Grover’s disease.

Grover’s disease mostly affects older men (>50 years), but occasionally occurs in women and younger people. Pruritus is a common complaint and some sufferers feel that sweating makes it worse. The cause is unknown and the prognosis is variable.

Grover’s disease is transient for some, but it can also be chronic or relapsing. As it is a relatively rare condition, there are few high-quality studies to guide treatment. Some of the treatments described in the literature include topical steroids, oral antihistamines, oral antifungals, oral antibiotics, oral retinoids, moisturizers, and phototherapy.

When this particular patient returned for follow-up, he noted about a 50% improvement in his symptoms and the red papules were less red. The patient was referred to Dermatology and told to continue the triamcinolone cream until he could see a dermatologist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Hunter-Anderson K. Folliculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:680-685.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP was concerned that this could be a drug eruption but didn’t want to stop the ACE inhibitor because the patient had hypertension that was finally under control. Therefore, she performed a punch biopsy around one of the red papules for a definitive diagnosis. She also prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream and oral hydroxyzine for the pruritus while awaiting the diagnosis. The punch biopsy revealed that the patient had transient acantholytic dermatosis, also known as Grover’s disease.

Grover’s disease mostly affects older men (>50 years), but occasionally occurs in women and younger people. Pruritus is a common complaint and some sufferers feel that sweating makes it worse. The cause is unknown and the prognosis is variable.

Grover’s disease is transient for some, but it can also be chronic or relapsing. As it is a relatively rare condition, there are few high-quality studies to guide treatment. Some of the treatments described in the literature include topical steroids, oral antihistamines, oral antifungals, oral antibiotics, oral retinoids, moisturizers, and phototherapy.

When this particular patient returned for follow-up, he noted about a 50% improvement in his symptoms and the red papules were less red. The patient was referred to Dermatology and told to continue the triamcinolone cream until he could see a dermatologist.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Hunter-Anderson K. Folliculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:680-685.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Pruritic rash on chest

The FP suspected that this could be Pityrosporum folliculitis because of the cape-like distribution and the lack of response to an antibiotic. While bacterial folliculitis is more common than Pityrosporum folliculitis, this condition is not rare. Pityrosporum is also known by the name Malassezia furfur, a yeast-like fungal organism.

A KOH preparation was performed, but no evidence of Pityrosporum was found. This was not suprising. While a KOH preparation for tinea versicolor is usually positive for a “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern seen with Pityrosporum, this is not always the case with Pityrosporum folliculitis because the yeast lives deeper in the hair follicle, rather than on the surface of the skin.

The patient was desperate for a definitive diagnosis and rapid treatment, so he was happy to undergo a punch biopsy around an involved hair follicle.

The FP began treatment with ketoconazole 2% shampoo to be applied daily to the hair and the involved areas while in the shower. In 10 days, the patient returned for the biopsy results, which confirmed the presence of Pityrosporum in the hair follicles. The patient didn’t notice any improvement with topical treatment, so the FP started the patient on oral fluconazole 200 mg/d for 2 weeks and the Pityrosporum folliculitis resolved. Typically, Pityrosporum folliculitis and/or tinea versicolor can be treated with systemic antifungals, topical azoles, and/or shampoos containing azoles, selenium, or zinc.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Hunter-Anderson K. Folliculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:680-685.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this could be Pityrosporum folliculitis because of the cape-like distribution and the lack of response to an antibiotic. While bacterial folliculitis is more common than Pityrosporum folliculitis, this condition is not rare. Pityrosporum is also known by the name Malassezia furfur, a yeast-like fungal organism.

A KOH preparation was performed, but no evidence of Pityrosporum was found. This was not suprising. While a KOH preparation for tinea versicolor is usually positive for a “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern seen with Pityrosporum, this is not always the case with Pityrosporum folliculitis because the yeast lives deeper in the hair follicle, rather than on the surface of the skin.

The patient was desperate for a definitive diagnosis and rapid treatment, so he was happy to undergo a punch biopsy around an involved hair follicle.

The FP began treatment with ketoconazole 2% shampoo to be applied daily to the hair and the involved areas while in the shower. In 10 days, the patient returned for the biopsy results, which confirmed the presence of Pityrosporum in the hair follicles. The patient didn’t notice any improvement with topical treatment, so the FP started the patient on oral fluconazole 200 mg/d for 2 weeks and the Pityrosporum folliculitis resolved. Typically, Pityrosporum folliculitis and/or tinea versicolor can be treated with systemic antifungals, topical azoles, and/or shampoos containing azoles, selenium, or zinc.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Hunter-Anderson K. Folliculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:680-685.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this could be Pityrosporum folliculitis because of the cape-like distribution and the lack of response to an antibiotic. While bacterial folliculitis is more common than Pityrosporum folliculitis, this condition is not rare. Pityrosporum is also known by the name Malassezia furfur, a yeast-like fungal organism.

A KOH preparation was performed, but no evidence of Pityrosporum was found. This was not suprising. While a KOH preparation for tinea versicolor is usually positive for a “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern seen with Pityrosporum, this is not always the case with Pityrosporum folliculitis because the yeast lives deeper in the hair follicle, rather than on the surface of the skin.

The patient was desperate for a definitive diagnosis and rapid treatment, so he was happy to undergo a punch biopsy around an involved hair follicle.

The FP began treatment with ketoconazole 2% shampoo to be applied daily to the hair and the involved areas while in the shower. In 10 days, the patient returned for the biopsy results, which confirmed the presence of Pityrosporum in the hair follicles. The patient didn’t notice any improvement with topical treatment, so the FP started the patient on oral fluconazole 200 mg/d for 2 weeks and the Pityrosporum folliculitis resolved. Typically, Pityrosporum folliculitis and/or tinea versicolor can be treated with systemic antifungals, topical azoles, and/or shampoos containing azoles, selenium, or zinc.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Hunter-Anderson K. Folliculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:680-685.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Pruritic lesions on back

The family physician (FP) noted that the lesions were centered on hair follicles and diagnosed bacterial folliculitis. She prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days.

On follow-up, the rash hadn’t improved, so the FP suggested a punch biopsy and the patient consented to the procedure. This time, the FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream and hydroxyzine for the itching, as the diagnosis was uncertain. The biopsy revealed that the patient had eosinophilic folliculitis, a condition mostly seen in immunosuppressed individuals, including those with HIV/AIDS.

Eosinophilic folliculitis associated with HIV is treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) as well as one or more of the following: topical steroids, antihistamines, itraconazole, metronidazole, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral retinoids, or ultraviolet light therapy.

When the patient returned for a follow-up visit, the FP noted considerable improvement that was likely due to the restart of his HAART therapy and use of the topical steroid and antihistamine. The FP encouraged the patient to call for an appointment if the eosinophilic folliculitis didn’t resolve completely.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Hunter-Anderson K. Folliculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:680-685.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) noted that the lesions were centered on hair follicles and diagnosed bacterial folliculitis. She prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days.

On follow-up, the rash hadn’t improved, so the FP suggested a punch biopsy and the patient consented to the procedure. This time, the FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream and hydroxyzine for the itching, as the diagnosis was uncertain. The biopsy revealed that the patient had eosinophilic folliculitis, a condition mostly seen in immunosuppressed individuals, including those with HIV/AIDS.

Eosinophilic folliculitis associated with HIV is treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) as well as one or more of the following: topical steroids, antihistamines, itraconazole, metronidazole, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral retinoids, or ultraviolet light therapy.

When the patient returned for a follow-up visit, the FP noted considerable improvement that was likely due to the restart of his HAART therapy and use of the topical steroid and antihistamine. The FP encouraged the patient to call for an appointment if the eosinophilic folliculitis didn’t resolve completely.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Hunter-Anderson K. Folliculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:680-685.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) noted that the lesions were centered on hair follicles and diagnosed bacterial folliculitis. She prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days.

On follow-up, the rash hadn’t improved, so the FP suggested a punch biopsy and the patient consented to the procedure. This time, the FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream and hydroxyzine for the itching, as the diagnosis was uncertain. The biopsy revealed that the patient had eosinophilic folliculitis, a condition mostly seen in immunosuppressed individuals, including those with HIV/AIDS.

Eosinophilic folliculitis associated with HIV is treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) as well as one or more of the following: topical steroids, antihistamines, itraconazole, metronidazole, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral retinoids, or ultraviolet light therapy.

When the patient returned for a follow-up visit, the FP noted considerable improvement that was likely due to the restart of his HAART therapy and use of the topical steroid and antihistamine. The FP encouraged the patient to call for an appointment if the eosinophilic folliculitis didn’t resolve completely.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Hunter-Anderson K. Folliculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:680-685.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Rash on abdomen

The FP diagnosed bullous impetigo with surrounding cellulitis. The most likely cause was Staphylococcus aureus. Honey crusts are typical of impetigo, a superficial bacterial infection of the skin. Bullae are less common in impetigo and should be a tip-off that methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is involved. In this case, the surrounding erythema indicated that the infection might have penetrated deeper into the dermis, producing a coexisting cellulitis.

If MRSA is suspected, some clinicians culture the lesions while starting an appropriate antibiotic. However, this is not necessary if the antibiotic choice is effective against MRSA. In one randomized controlled trial, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole achieved 100% clearance in the treatment of impetigo in children cultured with MRSA and group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus.

The 2 best treatment choices for children of this age with bullous impetigo are trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or clindamycin. They are both available in oral liquid preparations as generic medicines.

The FP chose to give the child trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole twice daily (as there is less resistance to this compared to clindamycin) for 10 days. The physician also discussed hygiene issues with the mother and how to avoid the condition from spreading within the household. The FP told the mother to bring the child back if she didn’t notice an improvement within 2 days. The FP called the home 2 days later and learned that the child was significantly better. The bullous impetigo and cellulitis fully resolved within 10 days.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Impetigo. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:676-679.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed bullous impetigo with surrounding cellulitis. The most likely cause was Staphylococcus aureus. Honey crusts are typical of impetigo, a superficial bacterial infection of the skin. Bullae are less common in impetigo and should be a tip-off that methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is involved. In this case, the surrounding erythema indicated that the infection might have penetrated deeper into the dermis, producing a coexisting cellulitis.

If MRSA is suspected, some clinicians culture the lesions while starting an appropriate antibiotic. However, this is not necessary if the antibiotic choice is effective against MRSA. In one randomized controlled trial, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole achieved 100% clearance in the treatment of impetigo in children cultured with MRSA and group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus.

The 2 best treatment choices for children of this age with bullous impetigo are trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or clindamycin. They are both available in oral liquid preparations as generic medicines.

The FP chose to give the child trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole twice daily (as there is less resistance to this compared to clindamycin) for 10 days. The physician also discussed hygiene issues with the mother and how to avoid the condition from spreading within the household. The FP told the mother to bring the child back if she didn’t notice an improvement within 2 days. The FP called the home 2 days later and learned that the child was significantly better. The bullous impetigo and cellulitis fully resolved within 10 days.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Impetigo. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:676-679.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed bullous impetigo with surrounding cellulitis. The most likely cause was Staphylococcus aureus. Honey crusts are typical of impetigo, a superficial bacterial infection of the skin. Bullae are less common in impetigo and should be a tip-off that methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is involved. In this case, the surrounding erythema indicated that the infection might have penetrated deeper into the dermis, producing a coexisting cellulitis.

If MRSA is suspected, some clinicians culture the lesions while starting an appropriate antibiotic. However, this is not necessary if the antibiotic choice is effective against MRSA. In one randomized controlled trial, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole achieved 100% clearance in the treatment of impetigo in children cultured with MRSA and group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus.

The 2 best treatment choices for children of this age with bullous impetigo are trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or clindamycin. They are both available in oral liquid preparations as generic medicines.

The FP chose to give the child trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole twice daily (as there is less resistance to this compared to clindamycin) for 10 days. The physician also discussed hygiene issues with the mother and how to avoid the condition from spreading within the household. The FP told the mother to bring the child back if she didn’t notice an improvement within 2 days. The FP called the home 2 days later and learned that the child was significantly better. The bullous impetigo and cellulitis fully resolved within 10 days.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Impetigo. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:676-679.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Young man with unexplained hair loss

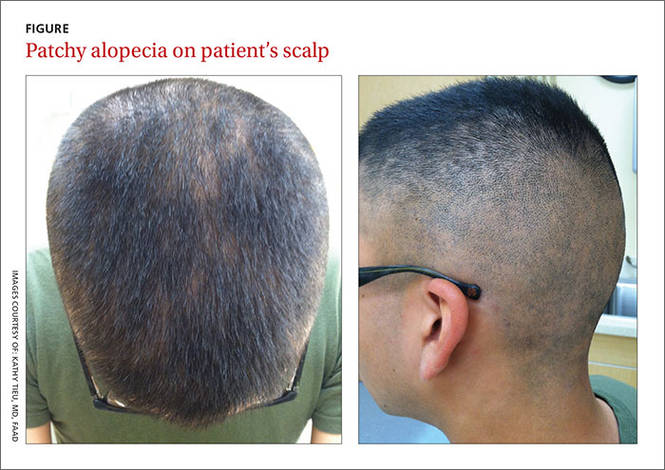

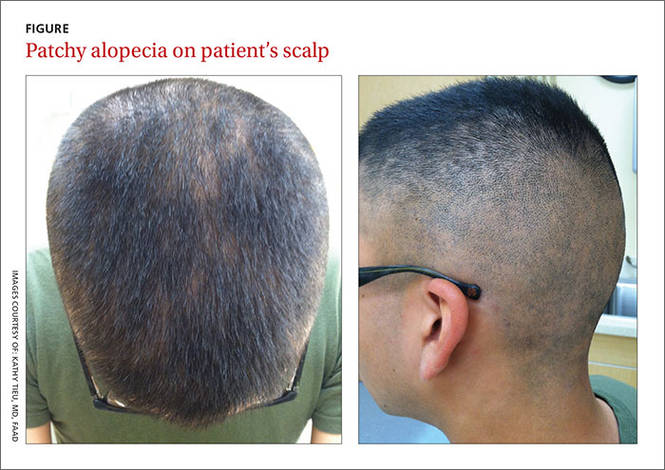

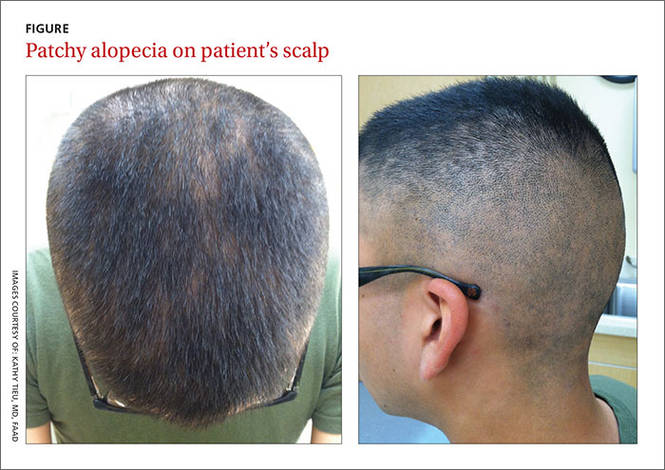

A 21-year-old Hispanic man sought care at our dermatology clinic because he was concerned about the patchy hair loss on his scalp that had begun 4 months earlier (FIGURE). His primary care physician had prescribed topical antifungals for presumed seborrheic dermatitis with no effect.

Three months prior to his visit with us, the patient had also seen his primary care physician for a nonspecific exanthema. It was presumed to be a viral exanthem and spontaneously resolved.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

Our patient’s “moth-eaten” alopecia—an uncommon sign of syphilis—heightened our suspicion of this sexually transmitted infection and prompted us to ask additional questions about his sexual history. We learned that our patient had engaged in unprotected sex with a male partner approximately 6 months prior to his unusual hair loss. Shortly after that encounter, the patient went to his primary care physician for screening of sexually transmitted diseases after his partner had complained of a new lesion on his penis. At that screening, our patient was tested for chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes simplex virus (HSV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and was given a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. He was positive only for HSV-1.

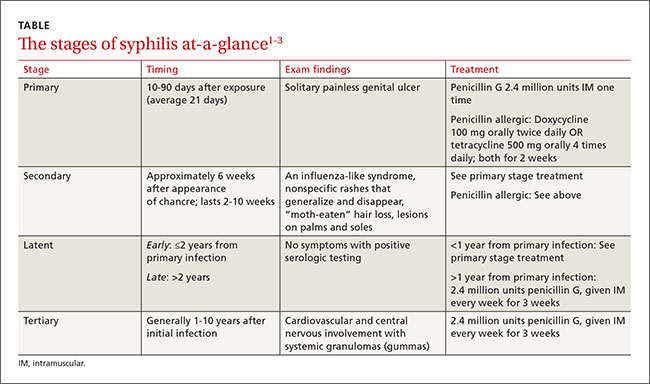

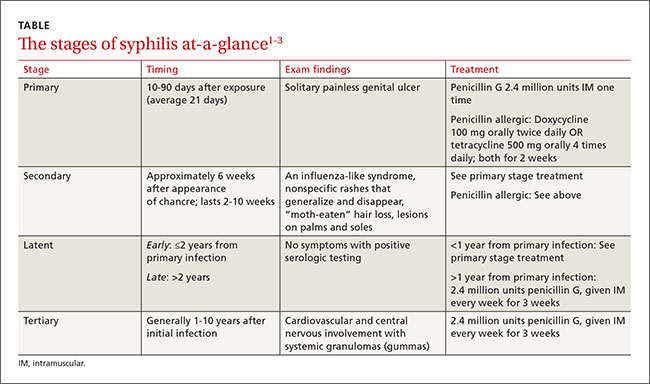

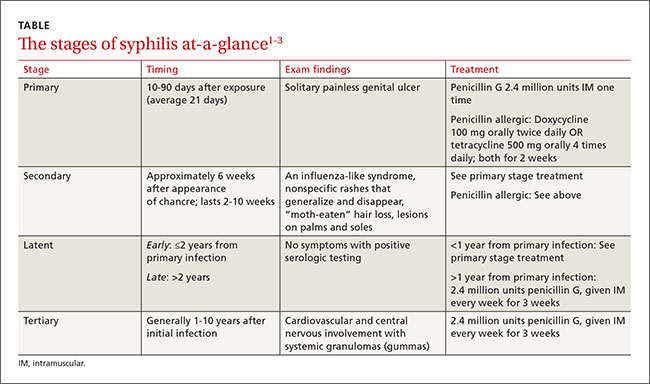

How “the great imitator” presents. A solitary painless genital ulcer marks the first (primary) stage of infection with the spirochete Treponema pallidum (TABLE1-3). Secondary syphilis results from the hematogenous or lymphatic spread of the Treponema pallidum spirochete, and often results in dermatologic findings that mimic numerous other conditions. Patients may also experience fever and myalgia. Typically, secondary syphilis lesions are pink and scaly 1 to 2 cm patches, which generalize in 80% of patients.2 Alopecia in a “moth-eaten” pattern is an uncommon finding of secondary syphilis, and should prompt a thorough sexual history.

While syphilis can be diagnosed by direct detection of the treponemal spirochete under dark-field microscopy, it is usually identified by one of 2 quick and inexpensive serologic screening tests: an RPR or a venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test. These tests can be positive as early as 7 days after the appearance of the original chancre. Due to the possibility of a false positive result caused by a viral infection, tuberculosis, or connective tissue diseases, confirmatory testing with fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) or a Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA) is necessary.2

Our patient initially had several false negative RPR tests. His RPR at the time of his visit to our dermatology clinic was also negative. This was due to the prozone phenomenon, which occurs when a high antibody titer interferes with the formation of an antigen-antibody lattice, which is needed for a positive flocculation test. The incidence of this phenomenon ranges from 0.2% to 2%,1 and it is commonly reported with HIV coinfection and pregnancy. If syphilis is suspected in a patient, a negative RPR should prompt requests for the laboratory to dilute the patient’s serum to ensure that the prozone phenomenon does not result in a false negative.

Because we highly suspected syphilis in our patient, we requested his serum be serially diluted. The final RPR titer was positive (1:128), and a confirmatory FTA-ABS was also positive.

Rule out these other potential causes of hair loss

The differential diagnosis for syphilis alopecia includes alopecia areata, telogen effluvium, trichotillomania, and tinea capitis.

Alopecia areata is characterized by the rapid loss of sharply defined round/oval areas of hair, and is often seen in children and young adults with a family history of autoimmune disorders.4 Topical or intralesional steroid injections are used for treatment, although the condition can self-resolve.

Telogen effluvium is sudden diffuse hair loss following a major stressor (such as childbirth, a “crash” diet, or severe illness).4 The hair loss often stops when the underlying event has passed.

Trichotillomania is recurrent hair pulling that results in patches of hair loss with irregular and angulated borders.4 Treatment usually consists of behavioral modification and psychotherapy.

Tinea capitis is caused by the invasion of hair shafts by fungal hyphae. Findings range from small, round, scaly areas of alopecia to large, inflamed, boggy lesions (kerions). Fungal hyphae are visible on a potassium hydroxide preparation. Treatment includes oral antifungals and topical selenium sulfide or ketoconazole shampoo.2,4

Treat with penicillin

Treatment at any stage is important to prevent further progression and central nervous system or cardiac dissemination. The initial treatment for either primary or secondary (<1 year) syphilis is one injection of penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscularly (IM). When treating symptoms of more than a year’s duration, the injection is repeated once a week for 3 consecutive weeks. For patients who are allergic to penicillin, oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily or tetracycline 500 mg 4 times daily can be used for 2 weeks.3

Our patient received a single dose of penicillin G 2.4 million units IM. The result was complete resolution of his alopecia. He was retested at 6 months and there was an appropriate drop in titer. Infectious disease specialists were notified on the day of diagnosis, and the patient’s partner was also contacted for testing and treatment. Both patients were counseled on safe sex practices.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeffrey Kinard, DO, 31 AMDS/SGPF, APO, AE, 09604; [email protected].

1. Sidana R, Mangala HC, Murugesh SB, et al. Prozone phenomenon in secondary syphilis. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2011;32:47-49.

2. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Habif TP, Campbell JL, Chapman MS, et al, eds. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. 3rd ed. New York: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:184-189.

3. Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;63:1-137.

4. Mounsey AL, Reed SW. Diagnosing and treating hair loss. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:356-362.

A 21-year-old Hispanic man sought care at our dermatology clinic because he was concerned about the patchy hair loss on his scalp that had begun 4 months earlier (FIGURE). His primary care physician had prescribed topical antifungals for presumed seborrheic dermatitis with no effect.

Three months prior to his visit with us, the patient had also seen his primary care physician for a nonspecific exanthema. It was presumed to be a viral exanthem and spontaneously resolved.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

Our patient’s “moth-eaten” alopecia—an uncommon sign of syphilis—heightened our suspicion of this sexually transmitted infection and prompted us to ask additional questions about his sexual history. We learned that our patient had engaged in unprotected sex with a male partner approximately 6 months prior to his unusual hair loss. Shortly after that encounter, the patient went to his primary care physician for screening of sexually transmitted diseases after his partner had complained of a new lesion on his penis. At that screening, our patient was tested for chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes simplex virus (HSV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and was given a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. He was positive only for HSV-1.

How “the great imitator” presents. A solitary painless genital ulcer marks the first (primary) stage of infection with the spirochete Treponema pallidum (TABLE1-3). Secondary syphilis results from the hematogenous or lymphatic spread of the Treponema pallidum spirochete, and often results in dermatologic findings that mimic numerous other conditions. Patients may also experience fever and myalgia. Typically, secondary syphilis lesions are pink and scaly 1 to 2 cm patches, which generalize in 80% of patients.2 Alopecia in a “moth-eaten” pattern is an uncommon finding of secondary syphilis, and should prompt a thorough sexual history.

While syphilis can be diagnosed by direct detection of the treponemal spirochete under dark-field microscopy, it is usually identified by one of 2 quick and inexpensive serologic screening tests: an RPR or a venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test. These tests can be positive as early as 7 days after the appearance of the original chancre. Due to the possibility of a false positive result caused by a viral infection, tuberculosis, or connective tissue diseases, confirmatory testing with fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) or a Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA) is necessary.2

Our patient initially had several false negative RPR tests. His RPR at the time of his visit to our dermatology clinic was also negative. This was due to the prozone phenomenon, which occurs when a high antibody titer interferes with the formation of an antigen-antibody lattice, which is needed for a positive flocculation test. The incidence of this phenomenon ranges from 0.2% to 2%,1 and it is commonly reported with HIV coinfection and pregnancy. If syphilis is suspected in a patient, a negative RPR should prompt requests for the laboratory to dilute the patient’s serum to ensure that the prozone phenomenon does not result in a false negative.

Because we highly suspected syphilis in our patient, we requested his serum be serially diluted. The final RPR titer was positive (1:128), and a confirmatory FTA-ABS was also positive.

Rule out these other potential causes of hair loss

The differential diagnosis for syphilis alopecia includes alopecia areata, telogen effluvium, trichotillomania, and tinea capitis.

Alopecia areata is characterized by the rapid loss of sharply defined round/oval areas of hair, and is often seen in children and young adults with a family history of autoimmune disorders.4 Topical or intralesional steroid injections are used for treatment, although the condition can self-resolve.

Telogen effluvium is sudden diffuse hair loss following a major stressor (such as childbirth, a “crash” diet, or severe illness).4 The hair loss often stops when the underlying event has passed.

Trichotillomania is recurrent hair pulling that results in patches of hair loss with irregular and angulated borders.4 Treatment usually consists of behavioral modification and psychotherapy.

Tinea capitis is caused by the invasion of hair shafts by fungal hyphae. Findings range from small, round, scaly areas of alopecia to large, inflamed, boggy lesions (kerions). Fungal hyphae are visible on a potassium hydroxide preparation. Treatment includes oral antifungals and topical selenium sulfide or ketoconazole shampoo.2,4

Treat with penicillin

Treatment at any stage is important to prevent further progression and central nervous system or cardiac dissemination. The initial treatment for either primary or secondary (<1 year) syphilis is one injection of penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscularly (IM). When treating symptoms of more than a year’s duration, the injection is repeated once a week for 3 consecutive weeks. For patients who are allergic to penicillin, oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily or tetracycline 500 mg 4 times daily can be used for 2 weeks.3

Our patient received a single dose of penicillin G 2.4 million units IM. The result was complete resolution of his alopecia. He was retested at 6 months and there was an appropriate drop in titer. Infectious disease specialists were notified on the day of diagnosis, and the patient’s partner was also contacted for testing and treatment. Both patients were counseled on safe sex practices.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeffrey Kinard, DO, 31 AMDS/SGPF, APO, AE, 09604; [email protected].

A 21-year-old Hispanic man sought care at our dermatology clinic because he was concerned about the patchy hair loss on his scalp that had begun 4 months earlier (FIGURE). His primary care physician had prescribed topical antifungals for presumed seborrheic dermatitis with no effect.

Three months prior to his visit with us, the patient had also seen his primary care physician for a nonspecific exanthema. It was presumed to be a viral exanthem and spontaneously resolved.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

Our patient’s “moth-eaten” alopecia—an uncommon sign of syphilis—heightened our suspicion of this sexually transmitted infection and prompted us to ask additional questions about his sexual history. We learned that our patient had engaged in unprotected sex with a male partner approximately 6 months prior to his unusual hair loss. Shortly after that encounter, the patient went to his primary care physician for screening of sexually transmitted diseases after his partner had complained of a new lesion on his penis. At that screening, our patient was tested for chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes simplex virus (HSV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and was given a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. He was positive only for HSV-1.

How “the great imitator” presents. A solitary painless genital ulcer marks the first (primary) stage of infection with the spirochete Treponema pallidum (TABLE1-3). Secondary syphilis results from the hematogenous or lymphatic spread of the Treponema pallidum spirochete, and often results in dermatologic findings that mimic numerous other conditions. Patients may also experience fever and myalgia. Typically, secondary syphilis lesions are pink and scaly 1 to 2 cm patches, which generalize in 80% of patients.2 Alopecia in a “moth-eaten” pattern is an uncommon finding of secondary syphilis, and should prompt a thorough sexual history.

While syphilis can be diagnosed by direct detection of the treponemal spirochete under dark-field microscopy, it is usually identified by one of 2 quick and inexpensive serologic screening tests: an RPR or a venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test. These tests can be positive as early as 7 days after the appearance of the original chancre. Due to the possibility of a false positive result caused by a viral infection, tuberculosis, or connective tissue diseases, confirmatory testing with fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) or a Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA) is necessary.2

Our patient initially had several false negative RPR tests. His RPR at the time of his visit to our dermatology clinic was also negative. This was due to the prozone phenomenon, which occurs when a high antibody titer interferes with the formation of an antigen-antibody lattice, which is needed for a positive flocculation test. The incidence of this phenomenon ranges from 0.2% to 2%,1 and it is commonly reported with HIV coinfection and pregnancy. If syphilis is suspected in a patient, a negative RPR should prompt requests for the laboratory to dilute the patient’s serum to ensure that the prozone phenomenon does not result in a false negative.

Because we highly suspected syphilis in our patient, we requested his serum be serially diluted. The final RPR titer was positive (1:128), and a confirmatory FTA-ABS was also positive.

Rule out these other potential causes of hair loss

The differential diagnosis for syphilis alopecia includes alopecia areata, telogen effluvium, trichotillomania, and tinea capitis.

Alopecia areata is characterized by the rapid loss of sharply defined round/oval areas of hair, and is often seen in children and young adults with a family history of autoimmune disorders.4 Topical or intralesional steroid injections are used for treatment, although the condition can self-resolve.

Telogen effluvium is sudden diffuse hair loss following a major stressor (such as childbirth, a “crash” diet, or severe illness).4 The hair loss often stops when the underlying event has passed.

Trichotillomania is recurrent hair pulling that results in patches of hair loss with irregular and angulated borders.4 Treatment usually consists of behavioral modification and psychotherapy.

Tinea capitis is caused by the invasion of hair shafts by fungal hyphae. Findings range from small, round, scaly areas of alopecia to large, inflamed, boggy lesions (kerions). Fungal hyphae are visible on a potassium hydroxide preparation. Treatment includes oral antifungals and topical selenium sulfide or ketoconazole shampoo.2,4

Treat with penicillin

Treatment at any stage is important to prevent further progression and central nervous system or cardiac dissemination. The initial treatment for either primary or secondary (<1 year) syphilis is one injection of penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscularly (IM). When treating symptoms of more than a year’s duration, the injection is repeated once a week for 3 consecutive weeks. For patients who are allergic to penicillin, oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily or tetracycline 500 mg 4 times daily can be used for 2 weeks.3

Our patient received a single dose of penicillin G 2.4 million units IM. The result was complete resolution of his alopecia. He was retested at 6 months and there was an appropriate drop in titer. Infectious disease specialists were notified on the day of diagnosis, and the patient’s partner was also contacted for testing and treatment. Both patients were counseled on safe sex practices.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeffrey Kinard, DO, 31 AMDS/SGPF, APO, AE, 09604; [email protected].

1. Sidana R, Mangala HC, Murugesh SB, et al. Prozone phenomenon in secondary syphilis. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2011;32:47-49.

2. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Habif TP, Campbell JL, Chapman MS, et al, eds. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. 3rd ed. New York: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:184-189.

3. Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;63:1-137.

4. Mounsey AL, Reed SW. Diagnosing and treating hair loss. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:356-362.

1. Sidana R, Mangala HC, Murugesh SB, et al. Prozone phenomenon in secondary syphilis. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2011;32:47-49.

2. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Habif TP, Campbell JL, Chapman MS, et al, eds. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. 3rd ed. New York: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:184-189.

3. Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;63:1-137.

4. Mounsey AL, Reed SW. Diagnosing and treating hair loss. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:356-362.

Bumps in beard area

The FP diagnosed pseudofolliculitis, a common skin condition affecting the hair-bearing areas of the body that are shaved. Potential complications include post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, bacterial superinfection, and keloid formation.

Pseudofolliculitis is most common in black men and at least half of black men who shave are prone to it. The condition is called pseudofolliculitis barbae when it occurs in the beard area, and pseudofolliculitis pubis when it occurs after pubic hair is shaved. It may also occur in the neck area.

Pseudofolliculitis develops when, after shaving, the free end of a tightly coiled hair reenters the skin, causing a foreign-body-like inflammatory reaction. Tightly curled hair has a greater tendency to pierce the follicle and the surface of the skin, explaining the relative predominance of this condition in patients of African descent.

The FP encouraged the patient to avoid shaving as much as possible and to consider trying scissors or an electric clipper instead of a razor blade. The FP told the patient to search for ingrown hairs daily by using a magnifying mirror and to release them gently with a sterilized needle or tweezers.

The FP prescribed tretinoin cream 0.025% to be applied at night before sleep. While this medication is typically prescribed for acne, it can also help pseudofolliculitis. The FP also recommended trying over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream 1% for areas that were inflamed, painful, or itchy.

Alternative treatments involve chemical depilatories (such as Ali, Royal Crown, or Magic Shave), which cause fewer symptoms than shaving. However, these creams can cause severe irritation, so testing a small amount on the forearm is important. They work by breaking the disulfide bonds in hair, which results in the hair being bluntly broken at the follicular opening instead of sharply cut below the surface. They should be used every second or third day to avoid skin irritation, although this can be controlled with hydrocortisone cream.

Barium sulfide 2% powder depilatories can be made into a paste with water, applied to the beard, and removed after 3 to 5 minutes. Calcium thioglycolate preparations are left on for 10 to 15 minutes, but the fragrances can cause an allergic reaction and the treatment can result in chemical burns if left on for too long.

During a follow-up visit 2 months later, the skin on the young man’s face had improved and he was very pleased with the outcome. The FP recommended continuing the current regimen.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pseudofolliculitis and acne keloidalis nuchae. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:665-670.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed pseudofolliculitis, a common skin condition affecting the hair-bearing areas of the body that are shaved. Potential complications include post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, bacterial superinfection, and keloid formation.

Pseudofolliculitis is most common in black men and at least half of black men who shave are prone to it. The condition is called pseudofolliculitis barbae when it occurs in the beard area, and pseudofolliculitis pubis when it occurs after pubic hair is shaved. It may also occur in the neck area.

Pseudofolliculitis develops when, after shaving, the free end of a tightly coiled hair reenters the skin, causing a foreign-body-like inflammatory reaction. Tightly curled hair has a greater tendency to pierce the follicle and the surface of the skin, explaining the relative predominance of this condition in patients of African descent.

The FP encouraged the patient to avoid shaving as much as possible and to consider trying scissors or an electric clipper instead of a razor blade. The FP told the patient to search for ingrown hairs daily by using a magnifying mirror and to release them gently with a sterilized needle or tweezers.

The FP prescribed tretinoin cream 0.025% to be applied at night before sleep. While this medication is typically prescribed for acne, it can also help pseudofolliculitis. The FP also recommended trying over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream 1% for areas that were inflamed, painful, or itchy.

Alternative treatments involve chemical depilatories (such as Ali, Royal Crown, or Magic Shave), which cause fewer symptoms than shaving. However, these creams can cause severe irritation, so testing a small amount on the forearm is important. They work by breaking the disulfide bonds in hair, which results in the hair being bluntly broken at the follicular opening instead of sharply cut below the surface. They should be used every second or third day to avoid skin irritation, although this can be controlled with hydrocortisone cream.

Barium sulfide 2% powder depilatories can be made into a paste with water, applied to the beard, and removed after 3 to 5 minutes. Calcium thioglycolate preparations are left on for 10 to 15 minutes, but the fragrances can cause an allergic reaction and the treatment can result in chemical burns if left on for too long.

During a follow-up visit 2 months later, the skin on the young man’s face had improved and he was very pleased with the outcome. The FP recommended continuing the current regimen.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pseudofolliculitis and acne keloidalis nuchae. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:665-670.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed pseudofolliculitis, a common skin condition affecting the hair-bearing areas of the body that are shaved. Potential complications include post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, bacterial superinfection, and keloid formation.

Pseudofolliculitis is most common in black men and at least half of black men who shave are prone to it. The condition is called pseudofolliculitis barbae when it occurs in the beard area, and pseudofolliculitis pubis when it occurs after pubic hair is shaved. It may also occur in the neck area.

Pseudofolliculitis develops when, after shaving, the free end of a tightly coiled hair reenters the skin, causing a foreign-body-like inflammatory reaction. Tightly curled hair has a greater tendency to pierce the follicle and the surface of the skin, explaining the relative predominance of this condition in patients of African descent.

The FP encouraged the patient to avoid shaving as much as possible and to consider trying scissors or an electric clipper instead of a razor blade. The FP told the patient to search for ingrown hairs daily by using a magnifying mirror and to release them gently with a sterilized needle or tweezers.

The FP prescribed tretinoin cream 0.025% to be applied at night before sleep. While this medication is typically prescribed for acne, it can also help pseudofolliculitis. The FP also recommended trying over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream 1% for areas that were inflamed, painful, or itchy.

Alternative treatments involve chemical depilatories (such as Ali, Royal Crown, or Magic Shave), which cause fewer symptoms than shaving. However, these creams can cause severe irritation, so testing a small amount on the forearm is important. They work by breaking the disulfide bonds in hair, which results in the hair being bluntly broken at the follicular opening instead of sharply cut below the surface. They should be used every second or third day to avoid skin irritation, although this can be controlled with hydrocortisone cream.

Barium sulfide 2% powder depilatories can be made into a paste with water, applied to the beard, and removed after 3 to 5 minutes. Calcium thioglycolate preparations are left on for 10 to 15 minutes, but the fragrances can cause an allergic reaction and the treatment can result in chemical burns if left on for too long.

During a follow-up visit 2 months later, the skin on the young man’s face had improved and he was very pleased with the outcome. The FP recommended continuing the current regimen.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pseudofolliculitis and acne keloidalis nuchae. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:665-670.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Painful lesions in axillae

The family physician (FP) diagnosed hidradenitis suppurativa, a disorder of the terminal follicular epithelium in the apocrine gland-bearing skin. Hidradenitis suppurativa causes chronic relapsing inflammation with mucopurulent discharge. As seen in this case, it can also lead to sinus tracts, draining fistulas, and progressive scarring, as well as disabling pain and social isolation.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is also called acne inversa because it involves intertriginous areas and not the regions affected by acne (face and back). Patients typically complain of painful, tender, firm, nodular lesions in the axillae. Both obesity and smoking make the condition worse.

The patient was desperate for relief from this condition. The FP explained exacerbating factors and treatment options. The patient acknowledged that she needed to quit smoking and lose weight, but found it painful to move her arms because of the lesions in both axillae. She set a smoking quit date for 2 weeks in the future and planned to quit without any pharmacologic intervention. The physician suggested that she start exercising by walking, especially since she did not have any of the hidradenitis in the inguinal or buttocks region. Diet control was also briefly discussed.

The patient chose to have intralesional steroid injections for the 3 most painful nodules. The FP injected the nodules with triamcinolone 10 mg/mL and started the patient on doxycycline 100 mg bid for one month. Injections are less painful than incision and drainage and usually work better (unless there is a huge abscess).

The FP also explained that the Food and Drug Administration had approved the first drug specifically for hidradenitis, called adalimumab (Humira), which has been used for years for psoriasis and various other inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis. While he was not comfortable prescribing this injectable biologic medication, he offered the patient a referral to Dermatology. The patient gladly accepted this and was happy to know that there was some hope for her condition.

Unfortunately, adalimumab does not cure hidradenitis and will not reverse the damage that’s been done. It can, however, provide symptomatic relief and minimize the number of future flare-ups. Surgery is another option, but it is major surgery that involves a long, painful healing time that brings with it the risk of complications. Surgery is also not curative, as the hidradenitis may reappear in the skin that was not resected.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hidradenitis suppurativa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:671-675.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) diagnosed hidradenitis suppurativa, a disorder of the terminal follicular epithelium in the apocrine gland-bearing skin. Hidradenitis suppurativa causes chronic relapsing inflammation with mucopurulent discharge. As seen in this case, it can also lead to sinus tracts, draining fistulas, and progressive scarring, as well as disabling pain and social isolation.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is also called acne inversa because it involves intertriginous areas and not the regions affected by acne (face and back). Patients typically complain of painful, tender, firm, nodular lesions in the axillae. Both obesity and smoking make the condition worse.

The patient was desperate for relief from this condition. The FP explained exacerbating factors and treatment options. The patient acknowledged that she needed to quit smoking and lose weight, but found it painful to move her arms because of the lesions in both axillae. She set a smoking quit date for 2 weeks in the future and planned to quit without any pharmacologic intervention. The physician suggested that she start exercising by walking, especially since she did not have any of the hidradenitis in the inguinal or buttocks region. Diet control was also briefly discussed.

The patient chose to have intralesional steroid injections for the 3 most painful nodules. The FP injected the nodules with triamcinolone 10 mg/mL and started the patient on doxycycline 100 mg bid for one month. Injections are less painful than incision and drainage and usually work better (unless there is a huge abscess).

The FP also explained that the Food and Drug Administration had approved the first drug specifically for hidradenitis, called adalimumab (Humira), which has been used for years for psoriasis and various other inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis. While he was not comfortable prescribing this injectable biologic medication, he offered the patient a referral to Dermatology. The patient gladly accepted this and was happy to know that there was some hope for her condition.

Unfortunately, adalimumab does not cure hidradenitis and will not reverse the damage that’s been done. It can, however, provide symptomatic relief and minimize the number of future flare-ups. Surgery is another option, but it is major surgery that involves a long, painful healing time that brings with it the risk of complications. Surgery is also not curative, as the hidradenitis may reappear in the skin that was not resected.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hidradenitis suppurativa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:671-675.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) diagnosed hidradenitis suppurativa, a disorder of the terminal follicular epithelium in the apocrine gland-bearing skin. Hidradenitis suppurativa causes chronic relapsing inflammation with mucopurulent discharge. As seen in this case, it can also lead to sinus tracts, draining fistulas, and progressive scarring, as well as disabling pain and social isolation.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is also called acne inversa because it involves intertriginous areas and not the regions affected by acne (face and back). Patients typically complain of painful, tender, firm, nodular lesions in the axillae. Both obesity and smoking make the condition worse.

The patient was desperate for relief from this condition. The FP explained exacerbating factors and treatment options. The patient acknowledged that she needed to quit smoking and lose weight, but found it painful to move her arms because of the lesions in both axillae. She set a smoking quit date for 2 weeks in the future and planned to quit without any pharmacologic intervention. The physician suggested that she start exercising by walking, especially since she did not have any of the hidradenitis in the inguinal or buttocks region. Diet control was also briefly discussed.

The patient chose to have intralesional steroid injections for the 3 most painful nodules. The FP injected the nodules with triamcinolone 10 mg/mL and started the patient on doxycycline 100 mg bid for one month. Injections are less painful than incision and drainage and usually work better (unless there is a huge abscess).

The FP also explained that the Food and Drug Administration had approved the first drug specifically for hidradenitis, called adalimumab (Humira), which has been used for years for psoriasis and various other inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis. While he was not comfortable prescribing this injectable biologic medication, he offered the patient a referral to Dermatology. The patient gladly accepted this and was happy to know that there was some hope for her condition.

Unfortunately, adalimumab does not cure hidradenitis and will not reverse the damage that’s been done. It can, however, provide symptomatic relief and minimize the number of future flare-ups. Surgery is another option, but it is major surgery that involves a long, painful healing time that brings with it the risk of complications. Surgery is also not curative, as the hidradenitis may reappear in the skin that was not resected.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hidradenitis suppurativa. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:671-675.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Large, painful mass on neck

The FP diagnosed acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) based on the large keloidal mass with multiple hairs growing from single follicles. When multiple hairs grow from single follicles, this is called tufted folliculitis and is seen in various types of scarring alopecia.

The FP told the patient that the exact cause of AKN is unclear, but that it can occur in patients with tightly curled hair shafts and those whose posterior hairline is shaved with a razor. (For more on AKN, see last week’s case here.) The FP advised the patient to avoid short haircuts.

As far as treatment was concerned, the FP discussed the 2 best options: intralesional steroids and/or surgery. The major risks of intralesional steroids are pain at the time of injection and hypopigmentation of the skin at the site of injection weeks to months after the injection. Also, there is no guarantee that the steroid injection will work. As for surgery, the FP advised that there would be a significant risk of intraoperative bleeding and postoperative scarring; also, a plastic surgeon would need to be called in.

The patient was not interested in the surgery, and opted for the intralesional steroid injection, instead. The FP explained the risks and benefits of the procedure, got the patient’s written consent, and injected triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL into the mass using a 25-gauge needle. This was difficult to do because the mass was firm. During a follow-up visit a month later, the FP noted that the mass was smaller. At the patient’s request, a second injection was performed. This one involved a stronger concentration: 40 mg/mL triamcinolone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pseudofolliculitis and acne keloidalis nuchae. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:665-670.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) based on the large keloidal mass with multiple hairs growing from single follicles. When multiple hairs grow from single follicles, this is called tufted folliculitis and is seen in various types of scarring alopecia.

The FP told the patient that the exact cause of AKN is unclear, but that it can occur in patients with tightly curled hair shafts and those whose posterior hairline is shaved with a razor. (For more on AKN, see last week’s case here.) The FP advised the patient to avoid short haircuts.

As far as treatment was concerned, the FP discussed the 2 best options: intralesional steroids and/or surgery. The major risks of intralesional steroids are pain at the time of injection and hypopigmentation of the skin at the site of injection weeks to months after the injection. Also, there is no guarantee that the steroid injection will work. As for surgery, the FP advised that there would be a significant risk of intraoperative bleeding and postoperative scarring; also, a plastic surgeon would need to be called in.

The patient was not interested in the surgery, and opted for the intralesional steroid injection, instead. The FP explained the risks and benefits of the procedure, got the patient’s written consent, and injected triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL into the mass using a 25-gauge needle. This was difficult to do because the mass was firm. During a follow-up visit a month later, the FP noted that the mass was smaller. At the patient’s request, a second injection was performed. This one involved a stronger concentration: 40 mg/mL triamcinolone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pseudofolliculitis and acne keloidalis nuchae. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:665-670.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) based on the large keloidal mass with multiple hairs growing from single follicles. When multiple hairs grow from single follicles, this is called tufted folliculitis and is seen in various types of scarring alopecia.

The FP told the patient that the exact cause of AKN is unclear, but that it can occur in patients with tightly curled hair shafts and those whose posterior hairline is shaved with a razor. (For more on AKN, see last week’s case here.) The FP advised the patient to avoid short haircuts.

As far as treatment was concerned, the FP discussed the 2 best options: intralesional steroids and/or surgery. The major risks of intralesional steroids are pain at the time of injection and hypopigmentation of the skin at the site of injection weeks to months after the injection. Also, there is no guarantee that the steroid injection will work. As for surgery, the FP advised that there would be a significant risk of intraoperative bleeding and postoperative scarring; also, a plastic surgeon would need to be called in.

The patient was not interested in the surgery, and opted for the intralesional steroid injection, instead. The FP explained the risks and benefits of the procedure, got the patient’s written consent, and injected triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL into the mass using a 25-gauge needle. This was difficult to do because the mass was firm. During a follow-up visit a month later, the FP noted that the mass was smaller. At the patient’s request, a second injection was performed. This one involved a stronger concentration: 40 mg/mL triamcinolone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pseudofolliculitis and acne keloidalis nuchae. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:665-670.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Lesions on back of neck

The FP diagnosed acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN), a condition that occurs most often in black men, but can be seen in all ethnic groups. The lesions are often painful and cosmetically disfiguring. The exact cause of AKN is uncertain, but it often develops in areas of pseudofolliculitis or folliculitis. It may be associated with haircuts where the posterior hairline is shaved with a razor and in individuals with tightly curled hair shafts. Other possible etiologies include irritation from shirt collars and a chronic bacterial infection.

Tretinoin cream 0.025% may be useful in patients with a mild case of the disease, but it is rarely helpful in moderate to severe cases. It is first applied nightly for a week, and then reduced to every second or third night. Tretinoin may be used in conjunction with a mid-potency topical corticosteroid that is applied each morning.

In this case, the FP recommended that the patient avoid using a razor on the back of his neck and that he allow his hair to grow a bit longer there. This would minimize the irritation and also cover up some of the visible lesions. The FP also prescribed a 2-week course of doxycycline 100 mg bid and topical tretinoin 0.025% cream in the evening, with triamcinolone 0.1% cream in the morning to help with the itching and inflammation.

The patient returned a month later with fewer symptoms and lesions. The FP explained that there are no curative treatments and that he should stick with the current topical treatments for a bit longer.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pseudofolliculitis and acne keloidalis nuchae. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:665-670.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN), a condition that occurs most often in black men, but can be seen in all ethnic groups. The lesions are often painful and cosmetically disfiguring. The exact cause of AKN is uncertain, but it often develops in areas of pseudofolliculitis or folliculitis. It may be associated with haircuts where the posterior hairline is shaved with a razor and in individuals with tightly curled hair shafts. Other possible etiologies include irritation from shirt collars and a chronic bacterial infection.

Tretinoin cream 0.025% may be useful in patients with a mild case of the disease, but it is rarely helpful in moderate to severe cases. It is first applied nightly for a week, and then reduced to every second or third night. Tretinoin may be used in conjunction with a mid-potency topical corticosteroid that is applied each morning.

In this case, the FP recommended that the patient avoid using a razor on the back of his neck and that he allow his hair to grow a bit longer there. This would minimize the irritation and also cover up some of the visible lesions. The FP also prescribed a 2-week course of doxycycline 100 mg bid and topical tretinoin 0.025% cream in the evening, with triamcinolone 0.1% cream in the morning to help with the itching and inflammation.

The patient returned a month later with fewer symptoms and lesions. The FP explained that there are no curative treatments and that he should stick with the current topical treatments for a bit longer.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pseudofolliculitis and acne keloidalis nuchae. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:665-670.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/