User login

Severely swollen eye

This patient had a severe case of periorbital cellulitis. The ENT doctor ordered a computed tomography scan of the sinuses, which showed ethmoid and maxillary sinusitis on the right side with some proptosis. Periorbital cellulitis is often seen in conjunction with sinusitis in children and adults.

Mild cases with minimal upper eyelid swelling can be treated with oral antibiotics, whereas moderate to severe cases may require hospitalization for IV antibiotics and evaluation for surgical intervention. Possible complications of untreated periorbital cellulitis include orbital cellulitis, blindness, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and death.

This patient was prepped for sinus surgery to drain the infected sinuses. She also received IV antibiotics. Fortunately, she responded well to treatment and went home without any complications.

Photo courtesy of Frank Miller, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cellulitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:693-697.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

This patient had a severe case of periorbital cellulitis. The ENT doctor ordered a computed tomography scan of the sinuses, which showed ethmoid and maxillary sinusitis on the right side with some proptosis. Periorbital cellulitis is often seen in conjunction with sinusitis in children and adults.

Mild cases with minimal upper eyelid swelling can be treated with oral antibiotics, whereas moderate to severe cases may require hospitalization for IV antibiotics and evaluation for surgical intervention. Possible complications of untreated periorbital cellulitis include orbital cellulitis, blindness, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and death.

This patient was prepped for sinus surgery to drain the infected sinuses. She also received IV antibiotics. Fortunately, she responded well to treatment and went home without any complications.

Photo courtesy of Frank Miller, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cellulitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:693-697.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

This patient had a severe case of periorbital cellulitis. The ENT doctor ordered a computed tomography scan of the sinuses, which showed ethmoid and maxillary sinusitis on the right side with some proptosis. Periorbital cellulitis is often seen in conjunction with sinusitis in children and adults.

Mild cases with minimal upper eyelid swelling can be treated with oral antibiotics, whereas moderate to severe cases may require hospitalization for IV antibiotics and evaluation for surgical intervention. Possible complications of untreated periorbital cellulitis include orbital cellulitis, blindness, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and death.

This patient was prepped for sinus surgery to drain the infected sinuses. She also received IV antibiotics. Fortunately, she responded well to treatment and went home without any complications.

Photo courtesy of Frank Miller, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cellulitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:693-697.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Swollen nose and cheek

The FP diagnosed erysipelas. Erysipelas is a specific type of superficial cellulitis with prominent lymphatic involvement that leads to sharply defined and elevated borders. It is most often caused by β-hemolytic Streptococcus, but may also be caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

The classic treatment for erysipelas is systemic penicillin because of its excellent coverage of β-hemolytic Streptococcus. The route of administration—oral or IV—hinges on the severity of the case.

In light of a possible (mild) penicillin allergy, the physician treated the patient with oral cephalexin, which covers Streptococcus and methicillin sensitive S aureus. The FP discussed the pros and cons of hospitalization with the patient and they agreed that it was reasonable to start with oral outpatient therapy. The FP advised the patient to go to the emergency department if his condition worsened or if he was unable to hold down the oral medication.

At a 2-day follow-up appointment, the patient was afebrile and showed significant improvement. The patient finished the full 7-day course of the antibiotic without any complications.

Photo courtesy of Ernesto Samano Ayon, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cellulitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:693-697.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed erysipelas. Erysipelas is a specific type of superficial cellulitis with prominent lymphatic involvement that leads to sharply defined and elevated borders. It is most often caused by β-hemolytic Streptococcus, but may also be caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

The classic treatment for erysipelas is systemic penicillin because of its excellent coverage of β-hemolytic Streptococcus. The route of administration—oral or IV—hinges on the severity of the case.

In light of a possible (mild) penicillin allergy, the physician treated the patient with oral cephalexin, which covers Streptococcus and methicillin sensitive S aureus. The FP discussed the pros and cons of hospitalization with the patient and they agreed that it was reasonable to start with oral outpatient therapy. The FP advised the patient to go to the emergency department if his condition worsened or if he was unable to hold down the oral medication.

At a 2-day follow-up appointment, the patient was afebrile and showed significant improvement. The patient finished the full 7-day course of the antibiotic without any complications.

Photo courtesy of Ernesto Samano Ayon, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cellulitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:693-697.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed erysipelas. Erysipelas is a specific type of superficial cellulitis with prominent lymphatic involvement that leads to sharply defined and elevated borders. It is most often caused by β-hemolytic Streptococcus, but may also be caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

The classic treatment for erysipelas is systemic penicillin because of its excellent coverage of β-hemolytic Streptococcus. The route of administration—oral or IV—hinges on the severity of the case.

In light of a possible (mild) penicillin allergy, the physician treated the patient with oral cephalexin, which covers Streptococcus and methicillin sensitive S aureus. The FP discussed the pros and cons of hospitalization with the patient and they agreed that it was reasonable to start with oral outpatient therapy. The FP advised the patient to go to the emergency department if his condition worsened or if he was unable to hold down the oral medication.

At a 2-day follow-up appointment, the patient was afebrile and showed significant improvement. The patient finished the full 7-day course of the antibiotic without any complications.

Photo courtesy of Ernesto Samano Ayon, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cellulitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:693-697.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Violaceous bullae on legs

The FP suspected a Vibrio vulnificus infection secondary to ingesting the raw oysters, especially because the patient had a history of liver disease. V vulnificus grew out of the patient’s blood cultures, confirming the diagnosis.

V vulnificus is a free-living bacterium that is found in warm saltwater, such as in the Gulf of Mexico. This patient had been visiting the Gulf Coast when he ate the raw oysters. V vulnificus becomes concentrated in filter-feeding shellfish such as oysters.

Eating raw oysters can lead to overwhelming infections from V vulnificus, especially in those with liver disease, lymphoma, leukemia, and diabetes. The mortality rate in people with primary V vulnificus sepsis exceeds 40%.1

Unfortunately, the patient’s liver disease predisposed him to a more serious infection. Despite appropriate use of systemic antibiotics and supportive care, the patient died from sepsis.

1. Falcon LM, Pham L. Images in clinical medicine. Hemorrhagic cellulitis after consumption of raw oysters. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1604.

Photo courtesy of Donna Nguyen, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cellulitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:693-697.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected a Vibrio vulnificus infection secondary to ingesting the raw oysters, especially because the patient had a history of liver disease. V vulnificus grew out of the patient’s blood cultures, confirming the diagnosis.

V vulnificus is a free-living bacterium that is found in warm saltwater, such as in the Gulf of Mexico. This patient had been visiting the Gulf Coast when he ate the raw oysters. V vulnificus becomes concentrated in filter-feeding shellfish such as oysters.

Eating raw oysters can lead to overwhelming infections from V vulnificus, especially in those with liver disease, lymphoma, leukemia, and diabetes. The mortality rate in people with primary V vulnificus sepsis exceeds 40%.1

Unfortunately, the patient’s liver disease predisposed him to a more serious infection. Despite appropriate use of systemic antibiotics and supportive care, the patient died from sepsis.

1. Falcon LM, Pham L. Images in clinical medicine. Hemorrhagic cellulitis after consumption of raw oysters. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1604.

Photo courtesy of Donna Nguyen, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cellulitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:693-697.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected a Vibrio vulnificus infection secondary to ingesting the raw oysters, especially because the patient had a history of liver disease. V vulnificus grew out of the patient’s blood cultures, confirming the diagnosis.

V vulnificus is a free-living bacterium that is found in warm saltwater, such as in the Gulf of Mexico. This patient had been visiting the Gulf Coast when he ate the raw oysters. V vulnificus becomes concentrated in filter-feeding shellfish such as oysters.

Eating raw oysters can lead to overwhelming infections from V vulnificus, especially in those with liver disease, lymphoma, leukemia, and diabetes. The mortality rate in people with primary V vulnificus sepsis exceeds 40%.1

Unfortunately, the patient’s liver disease predisposed him to a more serious infection. Despite appropriate use of systemic antibiotics and supportive care, the patient died from sepsis.

1. Falcon LM, Pham L. Images in clinical medicine. Hemorrhagic cellulitis after consumption of raw oysters. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1604.

Photo courtesy of Donna Nguyen, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cellulitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:693-697.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Stiff hands and feet, facial deformities

A 47-year-old Malaysian aboriginal woman presented to our clinic with stiffness in her fingers and feet that had been bothering her for about 10 years. The patient had multiple facial deformities, including perioral fibrosis, which gave her face a bird-like appearance; micrognathia (which affected the alignment of her teeth); a narrow mouth with pursed, puckered lips; bound-down skin of the nose; and a loss of wrinkling.

Ivory-colored plaques of hard, thickened skin caused a pigmented, “salt and pepper” appearance on our patient’s face. She also had deformities of all of her fingers and toes that severely restricted her ability to move them (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Limited systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare autoimmune disease that mainly affects women ages 30 to 50.1 SSc is classified according to the extent of skin involvement and includes limited SSc (lSSc), which is also called CREST syndrome, and diffuse SSc (dSSc).

CREST stands for:

- calcinosis, or subcutaneous calcium deposits,

- Raynaud’s phenomenon,

- esophageal dysfunction,

- sclerodactyly, which presents as tightening of the skin of the fingers or toes, and

- telangiectasia, which is characterized by dilated superficial capillaries, usually on the face, arms, and hands.2

Patients like ours who have lSSc experience a gradual progression of symptoms. Their skin is affected in limited areas, such as the fingers, hands, face, lower arms, and feet. There is no involvement of the chest, abdomen, or internal organs, with the exception of the esophagus. Esophageal smooth muscle becomes atrophied and is replaced by fibrous tissue, leading to esophageal motility dysfunction. This is in contrast to dSSc, in which you would see involvement of internal organs such as the lungs, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.

Raynaud’s phenomenon is commonly the first symptom of lSSc, and often precedes other manifestations of the disease by years. Raynaud’s phenomenon is triggered by cold conditions and emotional stress, which cause spasms and narrowing of the blood vessels of the skin. Telangiectasia and calcinosis often follow skin tightening and thickening on the face and hands.

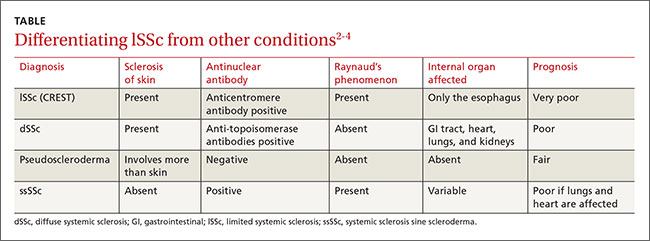

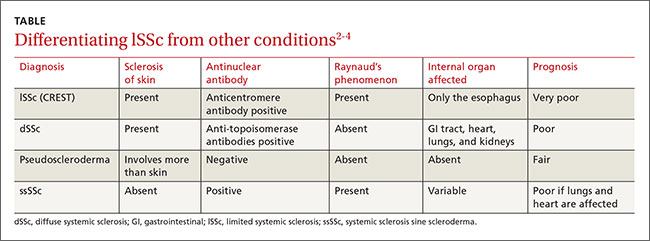

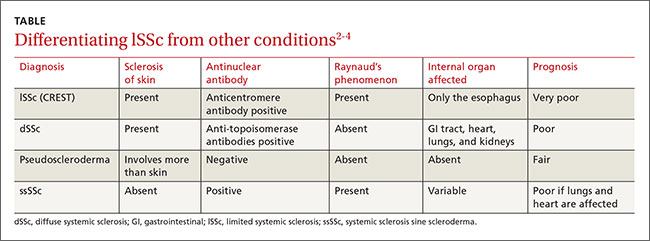

The differential diagnosis for lSSc includes dSSc, pseudoscleroderma, and systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma (ssSSc) (TABLE).2-4 In 2013, a joint committee of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism published revised classification criteria for SSc based on a scoring systemto improve sensitivity because the 1980 ACR criteria did not classify some cases of limited cutaneous SSc.5 Based on these revised criteria, patients having a total score of 9 or more are classified as having SSc. Our patient’s score was 15.

Lab tests, imaging studies are used to diagnose SSc

Generally, blood testing in patients with SSc may show thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, or (in patients with renal involvement of SSc) elevated blood urea and creatinine levels. Creatine kinase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein may be elevated due to myositis, vasculitis, malignancy, or an overlap of systemic sclerosis with another autoimmune disease.3

Serologic testing. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are positive in 60% to 80% of patients with SSc.2 Antibodies to topoisomerase-1 (Scl-70 antibodies) are present in 30% of cases of dSSc.2 The presence of either anticentromere antibodies (ACA) or anti-Scl-70 is highly specific (95%-99%) for the diagnosis of lSSc and dSSc, respectively.2 Anti-polymerase 1 and 3 antibodies (RNAP) are associated with dSSc and a significantly higher incidence of renal involvement.4

Capillary microscopy can be helpful in showing dilated, tortuous, and enlarged capillaries in the nail fold and adjacent areas. It is an effective method for distinguishing between primary and secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon.6

Chest x-ray. The lungs are involved in approximately 80% of all patients with SSc, and lung involvement is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality.7 The 2 most common types of direct pulmonary involvement are interstitial lung disease and pulmonary hypertension, which together account for 60% of SSc-related deaths.8

Key elements of sclerodermal lung disease are inflammation, lung scarring, and pulmonary hypertension due to progressive scarring of the inner lining of the small arteries. Inflammation and scarring of lung tissue causes interstitial lung disease. This is more common in dSSc, whereas pulmonary hypertension is more common in lSSc.8 In ssSSc, pulmonary disease can occur without any skin involvement. High-resolution computer tomography scans of the lungs (HRCT) can sensitively detect scarring and severity of lung inflammation, while a simple chest x-ray cannot.9 Interstitial abnormalities on HRCT have been found in 90% of patients.9

Spirometry. Interstitial lung disease leads to a reduction in forced vital capacity (FVC) and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Significant pulmonary involvement is detectable in 25% of patients with SSc within 3 years of diagnosis.10 Interstitial fibrosis shows a restrictive pattern on spirometry. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and FVC are reduced, and the FEV1/FVC ratio is normal or increased.

No cure, but patient-specific Tx can improve quality of life

SSc greatly reduces a patient’s self-esteem and quality of life. Because there is no cure, many patients develop depression.11,12 However, depending on the patient, some treatments can control symptoms and complications, and thus improve quality of life.

Because SSc is an autoimmune disease, immunosuppressive agents are a pillar of treatment. Recent studies have shown that low-dose pulse cyclophosphamide can stabilize pulmonary function.13

Raynaud’s phenomenon is treated with low-dose calcium-channel blockers, such as amlodipine 5 mg/d that is gradually increased to as much as 20 mg/d to increase blood flow to the fingers.14

Fibrosis of the skin is treated with daily doses of PUVA (photochemotherapy) 0.25 J/cm2 or 0.4 J/cm2 for 3 to 8 weeks (total doses between 3.5 J/cm2 and 9.6 J/cm2); this results in improvements in hand closure, skin sclerosis index, and flexion of fingers or knee joints.15 D-penicillamine, an anti-fibrotic drug that has the ability to not only destabilize tissue collagen but also reduce its production, is started early with a low dose and then carefully increased.16

Our patient declined hospital care or treatment and refused referral to a physiotherapist for hand exercises, paraffin baths, massages, splints, or water aerobics. Her condition remained stable and she has been able to manage on her own, despite her advanced stage of CREST syndrome.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chandramani Thuraisingham, MBBS, FAFP, FRACGP, AM, DRM, PDOH, International Medical University, Clinical School Seremban, Jalan Rasah, 70300 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia; [email protected].

1. Scleroderma. American College of Rheumatology Web site. Available at: http://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Scleroderma. Accessed January 7, 2016.

2. Chatterjee S. Systemic scleroderma. Cleveland Clinic Web site. August 2010. Available at: http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/rheumatology/systemic-sclerosis/. Accessed January 7, 2016.

3. Hinchcliff M, Varga J. Systemic sclerosis/scleroderma: a treatable multisystem disease. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78:961-968.

4. Bunn CC, Denton CP, Shi-Wen X, et al. Anti-RNA polymerases and other autoantibody specificities in systemic sclerosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:15-20.

5. van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1747-1755.

6. Pavlov-Dolijanovic S, Damjanov NS, Stojanovic RM, et al. Scleroderma pattern of nailfold capillary changes as predictive value for the development of a connective tissue disease: a follow-up study of 3,029 patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:3039-3045.

7. Lung involvement. University of Michigan Health System, Scleroderma Program Web site. Available at: https://www.med.umich.edu/scleroderma/patients/lung.htm. Accessed January 7, 2016.

8. Morelli S, Barbieri C, Sgreccia A, et al. Relationship between cutaneous and pulmonary involvement in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:81-85.

9. Schurawitzki H, Stiglbauer R, Graninger W, et al. Interstitial lung disease in progressive systemic sclerosis: high-resolution CT versus radiography. Radiology. 1990;176:755-759.

10. Wells AU, Steen V, Valentini G. Pulmonary complications: one of the most challenging complications of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:iii40-iii44.

11. Thombs BD, Taillefer SS, Hudson M, et al. Depression in patients with systemic sclerosis: a systematic review of the evidence. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1089-1097.

12. Benrud-Larson LM, Heinberg LJ, Boling C, et al. Body image dissatisfaction among women with scleroderma: extent and relationship to psychosocial function. Health Psychol. 2003;22:130-139.

13. Iudici M, Cuomo G, Vettori S, et al. Low-dose pulse cyclophosphamide in interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc-ILD): efficacy of maintenance immunosuppression in responders and non-responders. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;44:437-444.

14. Treatment of the Raynaud phenomenon resistant to initial therapy. UpToDate Website. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-the-raynaud-phenomenon-resistant-to-initial-therapy. Accessed January 7, 2016.

15. Kanekura T, Fukumaru S, Matsushita S, et al. Successful treatment of scleroderma with PUVA therapy. J Dermatol. 1996;23:455-459.

16. Jayson MI, Lovell C, Black CM, et al. Penicillamine therapy in systemic sclerosis. Proc R Soc Med. 1977;70:82-88.

A 47-year-old Malaysian aboriginal woman presented to our clinic with stiffness in her fingers and feet that had been bothering her for about 10 years. The patient had multiple facial deformities, including perioral fibrosis, which gave her face a bird-like appearance; micrognathia (which affected the alignment of her teeth); a narrow mouth with pursed, puckered lips; bound-down skin of the nose; and a loss of wrinkling.

Ivory-colored plaques of hard, thickened skin caused a pigmented, “salt and pepper” appearance on our patient’s face. She also had deformities of all of her fingers and toes that severely restricted her ability to move them (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Limited systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare autoimmune disease that mainly affects women ages 30 to 50.1 SSc is classified according to the extent of skin involvement and includes limited SSc (lSSc), which is also called CREST syndrome, and diffuse SSc (dSSc).

CREST stands for:

- calcinosis, or subcutaneous calcium deposits,

- Raynaud’s phenomenon,

- esophageal dysfunction,

- sclerodactyly, which presents as tightening of the skin of the fingers or toes, and

- telangiectasia, which is characterized by dilated superficial capillaries, usually on the face, arms, and hands.2

Patients like ours who have lSSc experience a gradual progression of symptoms. Their skin is affected in limited areas, such as the fingers, hands, face, lower arms, and feet. There is no involvement of the chest, abdomen, or internal organs, with the exception of the esophagus. Esophageal smooth muscle becomes atrophied and is replaced by fibrous tissue, leading to esophageal motility dysfunction. This is in contrast to dSSc, in which you would see involvement of internal organs such as the lungs, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.

Raynaud’s phenomenon is commonly the first symptom of lSSc, and often precedes other manifestations of the disease by years. Raynaud’s phenomenon is triggered by cold conditions and emotional stress, which cause spasms and narrowing of the blood vessels of the skin. Telangiectasia and calcinosis often follow skin tightening and thickening on the face and hands.

The differential diagnosis for lSSc includes dSSc, pseudoscleroderma, and systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma (ssSSc) (TABLE).2-4 In 2013, a joint committee of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism published revised classification criteria for SSc based on a scoring systemto improve sensitivity because the 1980 ACR criteria did not classify some cases of limited cutaneous SSc.5 Based on these revised criteria, patients having a total score of 9 or more are classified as having SSc. Our patient’s score was 15.

Lab tests, imaging studies are used to diagnose SSc

Generally, blood testing in patients with SSc may show thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, or (in patients with renal involvement of SSc) elevated blood urea and creatinine levels. Creatine kinase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein may be elevated due to myositis, vasculitis, malignancy, or an overlap of systemic sclerosis with another autoimmune disease.3

Serologic testing. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are positive in 60% to 80% of patients with SSc.2 Antibodies to topoisomerase-1 (Scl-70 antibodies) are present in 30% of cases of dSSc.2 The presence of either anticentromere antibodies (ACA) or anti-Scl-70 is highly specific (95%-99%) for the diagnosis of lSSc and dSSc, respectively.2 Anti-polymerase 1 and 3 antibodies (RNAP) are associated with dSSc and a significantly higher incidence of renal involvement.4

Capillary microscopy can be helpful in showing dilated, tortuous, and enlarged capillaries in the nail fold and adjacent areas. It is an effective method for distinguishing between primary and secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon.6

Chest x-ray. The lungs are involved in approximately 80% of all patients with SSc, and lung involvement is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality.7 The 2 most common types of direct pulmonary involvement are interstitial lung disease and pulmonary hypertension, which together account for 60% of SSc-related deaths.8

Key elements of sclerodermal lung disease are inflammation, lung scarring, and pulmonary hypertension due to progressive scarring of the inner lining of the small arteries. Inflammation and scarring of lung tissue causes interstitial lung disease. This is more common in dSSc, whereas pulmonary hypertension is more common in lSSc.8 In ssSSc, pulmonary disease can occur without any skin involvement. High-resolution computer tomography scans of the lungs (HRCT) can sensitively detect scarring and severity of lung inflammation, while a simple chest x-ray cannot.9 Interstitial abnormalities on HRCT have been found in 90% of patients.9

Spirometry. Interstitial lung disease leads to a reduction in forced vital capacity (FVC) and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Significant pulmonary involvement is detectable in 25% of patients with SSc within 3 years of diagnosis.10 Interstitial fibrosis shows a restrictive pattern on spirometry. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and FVC are reduced, and the FEV1/FVC ratio is normal or increased.

No cure, but patient-specific Tx can improve quality of life

SSc greatly reduces a patient’s self-esteem and quality of life. Because there is no cure, many patients develop depression.11,12 However, depending on the patient, some treatments can control symptoms and complications, and thus improve quality of life.

Because SSc is an autoimmune disease, immunosuppressive agents are a pillar of treatment. Recent studies have shown that low-dose pulse cyclophosphamide can stabilize pulmonary function.13

Raynaud’s phenomenon is treated with low-dose calcium-channel blockers, such as amlodipine 5 mg/d that is gradually increased to as much as 20 mg/d to increase blood flow to the fingers.14

Fibrosis of the skin is treated with daily doses of PUVA (photochemotherapy) 0.25 J/cm2 or 0.4 J/cm2 for 3 to 8 weeks (total doses between 3.5 J/cm2 and 9.6 J/cm2); this results in improvements in hand closure, skin sclerosis index, and flexion of fingers or knee joints.15 D-penicillamine, an anti-fibrotic drug that has the ability to not only destabilize tissue collagen but also reduce its production, is started early with a low dose and then carefully increased.16

Our patient declined hospital care or treatment and refused referral to a physiotherapist for hand exercises, paraffin baths, massages, splints, or water aerobics. Her condition remained stable and she has been able to manage on her own, despite her advanced stage of CREST syndrome.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chandramani Thuraisingham, MBBS, FAFP, FRACGP, AM, DRM, PDOH, International Medical University, Clinical School Seremban, Jalan Rasah, 70300 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia; [email protected].

A 47-year-old Malaysian aboriginal woman presented to our clinic with stiffness in her fingers and feet that had been bothering her for about 10 years. The patient had multiple facial deformities, including perioral fibrosis, which gave her face a bird-like appearance; micrognathia (which affected the alignment of her teeth); a narrow mouth with pursed, puckered lips; bound-down skin of the nose; and a loss of wrinkling.

Ivory-colored plaques of hard, thickened skin caused a pigmented, “salt and pepper” appearance on our patient’s face. She also had deformities of all of her fingers and toes that severely restricted her ability to move them (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Limited systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare autoimmune disease that mainly affects women ages 30 to 50.1 SSc is classified according to the extent of skin involvement and includes limited SSc (lSSc), which is also called CREST syndrome, and diffuse SSc (dSSc).

CREST stands for:

- calcinosis, or subcutaneous calcium deposits,

- Raynaud’s phenomenon,

- esophageal dysfunction,

- sclerodactyly, which presents as tightening of the skin of the fingers or toes, and

- telangiectasia, which is characterized by dilated superficial capillaries, usually on the face, arms, and hands.2

Patients like ours who have lSSc experience a gradual progression of symptoms. Their skin is affected in limited areas, such as the fingers, hands, face, lower arms, and feet. There is no involvement of the chest, abdomen, or internal organs, with the exception of the esophagus. Esophageal smooth muscle becomes atrophied and is replaced by fibrous tissue, leading to esophageal motility dysfunction. This is in contrast to dSSc, in which you would see involvement of internal organs such as the lungs, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.

Raynaud’s phenomenon is commonly the first symptom of lSSc, and often precedes other manifestations of the disease by years. Raynaud’s phenomenon is triggered by cold conditions and emotional stress, which cause spasms and narrowing of the blood vessels of the skin. Telangiectasia and calcinosis often follow skin tightening and thickening on the face and hands.

The differential diagnosis for lSSc includes dSSc, pseudoscleroderma, and systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma (ssSSc) (TABLE).2-4 In 2013, a joint committee of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism published revised classification criteria for SSc based on a scoring systemto improve sensitivity because the 1980 ACR criteria did not classify some cases of limited cutaneous SSc.5 Based on these revised criteria, patients having a total score of 9 or more are classified as having SSc. Our patient’s score was 15.

Lab tests, imaging studies are used to diagnose SSc

Generally, blood testing in patients with SSc may show thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, or (in patients with renal involvement of SSc) elevated blood urea and creatinine levels. Creatine kinase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein may be elevated due to myositis, vasculitis, malignancy, or an overlap of systemic sclerosis with another autoimmune disease.3

Serologic testing. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are positive in 60% to 80% of patients with SSc.2 Antibodies to topoisomerase-1 (Scl-70 antibodies) are present in 30% of cases of dSSc.2 The presence of either anticentromere antibodies (ACA) or anti-Scl-70 is highly specific (95%-99%) for the diagnosis of lSSc and dSSc, respectively.2 Anti-polymerase 1 and 3 antibodies (RNAP) are associated with dSSc and a significantly higher incidence of renal involvement.4

Capillary microscopy can be helpful in showing dilated, tortuous, and enlarged capillaries in the nail fold and adjacent areas. It is an effective method for distinguishing between primary and secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon.6

Chest x-ray. The lungs are involved in approximately 80% of all patients with SSc, and lung involvement is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality.7 The 2 most common types of direct pulmonary involvement are interstitial lung disease and pulmonary hypertension, which together account for 60% of SSc-related deaths.8

Key elements of sclerodermal lung disease are inflammation, lung scarring, and pulmonary hypertension due to progressive scarring of the inner lining of the small arteries. Inflammation and scarring of lung tissue causes interstitial lung disease. This is more common in dSSc, whereas pulmonary hypertension is more common in lSSc.8 In ssSSc, pulmonary disease can occur without any skin involvement. High-resolution computer tomography scans of the lungs (HRCT) can sensitively detect scarring and severity of lung inflammation, while a simple chest x-ray cannot.9 Interstitial abnormalities on HRCT have been found in 90% of patients.9

Spirometry. Interstitial lung disease leads to a reduction in forced vital capacity (FVC) and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Significant pulmonary involvement is detectable in 25% of patients with SSc within 3 years of diagnosis.10 Interstitial fibrosis shows a restrictive pattern on spirometry. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and FVC are reduced, and the FEV1/FVC ratio is normal or increased.

No cure, but patient-specific Tx can improve quality of life

SSc greatly reduces a patient’s self-esteem and quality of life. Because there is no cure, many patients develop depression.11,12 However, depending on the patient, some treatments can control symptoms and complications, and thus improve quality of life.

Because SSc is an autoimmune disease, immunosuppressive agents are a pillar of treatment. Recent studies have shown that low-dose pulse cyclophosphamide can stabilize pulmonary function.13

Raynaud’s phenomenon is treated with low-dose calcium-channel blockers, such as amlodipine 5 mg/d that is gradually increased to as much as 20 mg/d to increase blood flow to the fingers.14

Fibrosis of the skin is treated with daily doses of PUVA (photochemotherapy) 0.25 J/cm2 or 0.4 J/cm2 for 3 to 8 weeks (total doses between 3.5 J/cm2 and 9.6 J/cm2); this results in improvements in hand closure, skin sclerosis index, and flexion of fingers or knee joints.15 D-penicillamine, an anti-fibrotic drug that has the ability to not only destabilize tissue collagen but also reduce its production, is started early with a low dose and then carefully increased.16

Our patient declined hospital care or treatment and refused referral to a physiotherapist for hand exercises, paraffin baths, massages, splints, or water aerobics. Her condition remained stable and she has been able to manage on her own, despite her advanced stage of CREST syndrome.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chandramani Thuraisingham, MBBS, FAFP, FRACGP, AM, DRM, PDOH, International Medical University, Clinical School Seremban, Jalan Rasah, 70300 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia; [email protected].

1. Scleroderma. American College of Rheumatology Web site. Available at: http://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Scleroderma. Accessed January 7, 2016.

2. Chatterjee S. Systemic scleroderma. Cleveland Clinic Web site. August 2010. Available at: http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/rheumatology/systemic-sclerosis/. Accessed January 7, 2016.

3. Hinchcliff M, Varga J. Systemic sclerosis/scleroderma: a treatable multisystem disease. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78:961-968.

4. Bunn CC, Denton CP, Shi-Wen X, et al. Anti-RNA polymerases and other autoantibody specificities in systemic sclerosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:15-20.

5. van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1747-1755.

6. Pavlov-Dolijanovic S, Damjanov NS, Stojanovic RM, et al. Scleroderma pattern of nailfold capillary changes as predictive value for the development of a connective tissue disease: a follow-up study of 3,029 patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:3039-3045.

7. Lung involvement. University of Michigan Health System, Scleroderma Program Web site. Available at: https://www.med.umich.edu/scleroderma/patients/lung.htm. Accessed January 7, 2016.

8. Morelli S, Barbieri C, Sgreccia A, et al. Relationship between cutaneous and pulmonary involvement in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:81-85.

9. Schurawitzki H, Stiglbauer R, Graninger W, et al. Interstitial lung disease in progressive systemic sclerosis: high-resolution CT versus radiography. Radiology. 1990;176:755-759.

10. Wells AU, Steen V, Valentini G. Pulmonary complications: one of the most challenging complications of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:iii40-iii44.

11. Thombs BD, Taillefer SS, Hudson M, et al. Depression in patients with systemic sclerosis: a systematic review of the evidence. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1089-1097.

12. Benrud-Larson LM, Heinberg LJ, Boling C, et al. Body image dissatisfaction among women with scleroderma: extent and relationship to psychosocial function. Health Psychol. 2003;22:130-139.

13. Iudici M, Cuomo G, Vettori S, et al. Low-dose pulse cyclophosphamide in interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc-ILD): efficacy of maintenance immunosuppression in responders and non-responders. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;44:437-444.

14. Treatment of the Raynaud phenomenon resistant to initial therapy. UpToDate Website. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-the-raynaud-phenomenon-resistant-to-initial-therapy. Accessed January 7, 2016.

15. Kanekura T, Fukumaru S, Matsushita S, et al. Successful treatment of scleroderma with PUVA therapy. J Dermatol. 1996;23:455-459.

16. Jayson MI, Lovell C, Black CM, et al. Penicillamine therapy in systemic sclerosis. Proc R Soc Med. 1977;70:82-88.

1. Scleroderma. American College of Rheumatology Web site. Available at: http://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Scleroderma. Accessed January 7, 2016.

2. Chatterjee S. Systemic scleroderma. Cleveland Clinic Web site. August 2010. Available at: http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/rheumatology/systemic-sclerosis/. Accessed January 7, 2016.

3. Hinchcliff M, Varga J. Systemic sclerosis/scleroderma: a treatable multisystem disease. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78:961-968.

4. Bunn CC, Denton CP, Shi-Wen X, et al. Anti-RNA polymerases and other autoantibody specificities in systemic sclerosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:15-20.

5. van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1747-1755.

6. Pavlov-Dolijanovic S, Damjanov NS, Stojanovic RM, et al. Scleroderma pattern of nailfold capillary changes as predictive value for the development of a connective tissue disease: a follow-up study of 3,029 patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:3039-3045.

7. Lung involvement. University of Michigan Health System, Scleroderma Program Web site. Available at: https://www.med.umich.edu/scleroderma/patients/lung.htm. Accessed January 7, 2016.

8. Morelli S, Barbieri C, Sgreccia A, et al. Relationship between cutaneous and pulmonary involvement in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:81-85.

9. Schurawitzki H, Stiglbauer R, Graninger W, et al. Interstitial lung disease in progressive systemic sclerosis: high-resolution CT versus radiography. Radiology. 1990;176:755-759.

10. Wells AU, Steen V, Valentini G. Pulmonary complications: one of the most challenging complications of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:iii40-iii44.

11. Thombs BD, Taillefer SS, Hudson M, et al. Depression in patients with systemic sclerosis: a systematic review of the evidence. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1089-1097.

12. Benrud-Larson LM, Heinberg LJ, Boling C, et al. Body image dissatisfaction among women with scleroderma: extent and relationship to psychosocial function. Health Psychol. 2003;22:130-139.

13. Iudici M, Cuomo G, Vettori S, et al. Low-dose pulse cyclophosphamide in interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc-ILD): efficacy of maintenance immunosuppression in responders and non-responders. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;44:437-444.

14. Treatment of the Raynaud phenomenon resistant to initial therapy. UpToDate Website. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-the-raynaud-phenomenon-resistant-to-initial-therapy. Accessed January 7, 2016.

15. Kanekura T, Fukumaru S, Matsushita S, et al. Successful treatment of scleroderma with PUVA therapy. J Dermatol. 1996;23:455-459.

16. Jayson MI, Lovell C, Black CM, et al. Penicillamine therapy in systemic sclerosis. Proc R Soc Med. 1977;70:82-88.

Rash on feet

The FP diagnosed pitted keratolysis in this patient. Pitted keratolysis is a superficial foot infection caused by Gram-positive bacteria, including Kytococcus sedentarius, Corynebacterium species, and Dermatophilus congolensis.

These bacteria produce proteases that degrade the keratin of the stratum corneum, leaving visible pits on the soles of the feet. The condition is typically seen in people with chronically wet feet, such as rice paddy workers. The associated malodor in some patients is likely secondary to the production of sulfur byproducts; in this case, however, the wide-open plastic shoes that the patient wore did not retain any odor.

Pitted keratolysis may be associated with an itching and burning sensation in some patients. Pitted keratolysis usually involves the callused pressure-bearing areas of the foot, such as the heel, ball of the foot, or plantar great toe. It can also be found in friction areas between the toes, as seen in this patient.

Treatment is based on eliminating bacteria and reducing the moist environment in which the bacteria thrive. Topical erythromycin or clindamycin solution can be applied twice daily until the condition resolves. It may take 3 to 4 weeks to clear the skin lesions. Oral erythromycin is effective and may be considered if topical therapy fails.

In this case, the FP prescribed oral erythromycin because that was the only option available. He also encouraged the boy to keep his feet as dry as possible, despite the rainy climate and the fact that he didn’t have access to socks.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Babcock M, Usatine R. Pitted keratolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:686-688.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed pitted keratolysis in this patient. Pitted keratolysis is a superficial foot infection caused by Gram-positive bacteria, including Kytococcus sedentarius, Corynebacterium species, and Dermatophilus congolensis.

These bacteria produce proteases that degrade the keratin of the stratum corneum, leaving visible pits on the soles of the feet. The condition is typically seen in people with chronically wet feet, such as rice paddy workers. The associated malodor in some patients is likely secondary to the production of sulfur byproducts; in this case, however, the wide-open plastic shoes that the patient wore did not retain any odor.

Pitted keratolysis may be associated with an itching and burning sensation in some patients. Pitted keratolysis usually involves the callused pressure-bearing areas of the foot, such as the heel, ball of the foot, or plantar great toe. It can also be found in friction areas between the toes, as seen in this patient.

Treatment is based on eliminating bacteria and reducing the moist environment in which the bacteria thrive. Topical erythromycin or clindamycin solution can be applied twice daily until the condition resolves. It may take 3 to 4 weeks to clear the skin lesions. Oral erythromycin is effective and may be considered if topical therapy fails.

In this case, the FP prescribed oral erythromycin because that was the only option available. He also encouraged the boy to keep his feet as dry as possible, despite the rainy climate and the fact that he didn’t have access to socks.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Babcock M, Usatine R. Pitted keratolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:686-688.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed pitted keratolysis in this patient. Pitted keratolysis is a superficial foot infection caused by Gram-positive bacteria, including Kytococcus sedentarius, Corynebacterium species, and Dermatophilus congolensis.

These bacteria produce proteases that degrade the keratin of the stratum corneum, leaving visible pits on the soles of the feet. The condition is typically seen in people with chronically wet feet, such as rice paddy workers. The associated malodor in some patients is likely secondary to the production of sulfur byproducts; in this case, however, the wide-open plastic shoes that the patient wore did not retain any odor.

Pitted keratolysis may be associated with an itching and burning sensation in some patients. Pitted keratolysis usually involves the callused pressure-bearing areas of the foot, such as the heel, ball of the foot, or plantar great toe. It can also be found in friction areas between the toes, as seen in this patient.

Treatment is based on eliminating bacteria and reducing the moist environment in which the bacteria thrive. Topical erythromycin or clindamycin solution can be applied twice daily until the condition resolves. It may take 3 to 4 weeks to clear the skin lesions. Oral erythromycin is effective and may be considered if topical therapy fails.

In this case, the FP prescribed oral erythromycin because that was the only option available. He also encouraged the boy to keep his feet as dry as possible, despite the rainy climate and the fact that he didn’t have access to socks.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Babcock M, Usatine R. Pitted keratolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:686-688.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Swollen middle finger

The FP diagnosed cellulitis and an abscess over the proximal interphalangeal joint in this patient, a result of a closed fist bite (also known as a “fight bite”). The FP sent the patient to the emergency department for admission and inpatient care under the orthopedic service. The FP was concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, septic tenosynovitis, and traumatic tendon injuries—in addition to the cellulitis and abscess. The flora of a human bite injury made this more risky for the patient, as well.

In the hospital, the orthopedist cultured the open wound and irrigated the joint. There were no signs of osteomyelitis, broken bones, or tooth fragments clinically or on x-rays. The patient was started on IV penicillin and vancomycin based on his weight to cover Eikenella corrodens and Staphylococcus aureus, respectively, until the culture results came back.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cellulitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:693-697.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed cellulitis and an abscess over the proximal interphalangeal joint in this patient, a result of a closed fist bite (also known as a “fight bite”). The FP sent the patient to the emergency department for admission and inpatient care under the orthopedic service. The FP was concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, septic tenosynovitis, and traumatic tendon injuries—in addition to the cellulitis and abscess. The flora of a human bite injury made this more risky for the patient, as well.

In the hospital, the orthopedist cultured the open wound and irrigated the joint. There were no signs of osteomyelitis, broken bones, or tooth fragments clinically or on x-rays. The patient was started on IV penicillin and vancomycin based on his weight to cover Eikenella corrodens and Staphylococcus aureus, respectively, until the culture results came back.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cellulitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:693-697.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed cellulitis and an abscess over the proximal interphalangeal joint in this patient, a result of a closed fist bite (also known as a “fight bite”). The FP sent the patient to the emergency department for admission and inpatient care under the orthopedic service. The FP was concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, septic tenosynovitis, and traumatic tendon injuries—in addition to the cellulitis and abscess. The flora of a human bite injury made this more risky for the patient, as well.

In the hospital, the orthopedist cultured the open wound and irrigated the joint. There were no signs of osteomyelitis, broken bones, or tooth fragments clinically or on x-rays. The patient was started on IV penicillin and vancomycin based on his weight to cover Eikenella corrodens and Staphylococcus aureus, respectively, until the culture results came back.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Cellulitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:693-697.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Itchy rash in axillae

The FP diagnosed erythrasma, a chronic superficial bacterial skin infection found in the intertriginous areas—especially the axilla and the groin. Patches of erythrasma can also be found in the interspaces of the toes, intergluteal cleft, perianal skin, and inframammary area.

The causative agent is Corynebacterium minutissimum, a lipophilic Gram-positive non–spore-forming rod-shaped organism. In hot and humid conditions, this organism can invade and proliferate in the upper one-third of the stratum corneum. The organism produces porphyrins that result in coral-red fluorescence under a Wood’s lamp. Washing the area before examination, however, may eliminate the fluorescence.

Patients with erythrasma will present with well-demarcated, dry, red-brown patches that are slightly scaly in places. Some lesions appear redder in color whereas others appear browner—especially in patients with darker skin. Some patients don’t find the lesions bothersome, while others will complain of itching and burning. Risk factors for erythrasma include a warm climate, diabetes mellitus, immunocompromised status, obesity, hyperhidrosis, and poor hygiene.

Although the bacteria respond to a variety of antibacterial agents, the treatment of choice is oral erythromycin 250 mg 4 times a day for 14 days. Topical erythromycin 2% solution applied twice daily is an alternative for mild cases. Oral erythromycin shows cure rates as high as 100%. For treatment and prophylaxis of more severe cases, topical clindamycin may be added once daily during the course of oral erythromycin therapy and for 2 weeks after physical clearance of the lesions.

In this case, the FP prescribed oral erythromycin and the patient’s erythrasma cleared completely.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Allred A, Usatine R, Smith M. Erythrasma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:689-692.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed erythrasma, a chronic superficial bacterial skin infection found in the intertriginous areas—especially the axilla and the groin. Patches of erythrasma can also be found in the interspaces of the toes, intergluteal cleft, perianal skin, and inframammary area.

The causative agent is Corynebacterium minutissimum, a lipophilic Gram-positive non–spore-forming rod-shaped organism. In hot and humid conditions, this organism can invade and proliferate in the upper one-third of the stratum corneum. The organism produces porphyrins that result in coral-red fluorescence under a Wood’s lamp. Washing the area before examination, however, may eliminate the fluorescence.

Patients with erythrasma will present with well-demarcated, dry, red-brown patches that are slightly scaly in places. Some lesions appear redder in color whereas others appear browner—especially in patients with darker skin. Some patients don’t find the lesions bothersome, while others will complain of itching and burning. Risk factors for erythrasma include a warm climate, diabetes mellitus, immunocompromised status, obesity, hyperhidrosis, and poor hygiene.

Although the bacteria respond to a variety of antibacterial agents, the treatment of choice is oral erythromycin 250 mg 4 times a day for 14 days. Topical erythromycin 2% solution applied twice daily is an alternative for mild cases. Oral erythromycin shows cure rates as high as 100%. For treatment and prophylaxis of more severe cases, topical clindamycin may be added once daily during the course of oral erythromycin therapy and for 2 weeks after physical clearance of the lesions.

In this case, the FP prescribed oral erythromycin and the patient’s erythrasma cleared completely.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Allred A, Usatine R, Smith M. Erythrasma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:689-692.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed erythrasma, a chronic superficial bacterial skin infection found in the intertriginous areas—especially the axilla and the groin. Patches of erythrasma can also be found in the interspaces of the toes, intergluteal cleft, perianal skin, and inframammary area.

The causative agent is Corynebacterium minutissimum, a lipophilic Gram-positive non–spore-forming rod-shaped organism. In hot and humid conditions, this organism can invade and proliferate in the upper one-third of the stratum corneum. The organism produces porphyrins that result in coral-red fluorescence under a Wood’s lamp. Washing the area before examination, however, may eliminate the fluorescence.

Patients with erythrasma will present with well-demarcated, dry, red-brown patches that are slightly scaly in places. Some lesions appear redder in color whereas others appear browner—especially in patients with darker skin. Some patients don’t find the lesions bothersome, while others will complain of itching and burning. Risk factors for erythrasma include a warm climate, diabetes mellitus, immunocompromised status, obesity, hyperhidrosis, and poor hygiene.

Although the bacteria respond to a variety of antibacterial agents, the treatment of choice is oral erythromycin 250 mg 4 times a day for 14 days. Topical erythromycin 2% solution applied twice daily is an alternative for mild cases. Oral erythromycin shows cure rates as high as 100%. For treatment and prophylaxis of more severe cases, topical clindamycin may be added once daily during the course of oral erythromycin therapy and for 2 weeks after physical clearance of the lesions.

In this case, the FP prescribed oral erythromycin and the patient’s erythrasma cleared completely.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Allred A, Usatine R, Smith M. Erythrasma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:689-692.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Overwhelming foot odor

The FP diagnosed pitted keratolysis in addition to hyperhidrosis. Pitted keratolysis is a superficial foot infection caused by Gram-positive bacteria, including Kytococcus sedentarius, Corynebacterium species, and Dermatophilus congolensis.

These bacteria produce proteases that degrade the keratin of the stratum corneum, leaving visible pits on the soles of the feet. The associated malodor is likely secondary to the production of sulfur byproducts.

Pitted keratolysis is more common in men and is often a complication of hyperhidrosis. It’s associated with an itching and burning sensation in some patients. The condition usually involves the callused pressure-bearing areas of the foot, such as the heel, ball of the foot, or plantar great toe.

Treatment is based on eliminating bacteria and reducing the moist environment in which the bacteria thrive. Topical erythromycin or clindamycin solution can be applied twice daily until the condition resolves. It may take 3 to 4 weeks to clear the odor and skin lesions. Oral erythromycin is effective and may be considered if topical therapy fails. Treating underlying hyperhidrosis is also important to prevent recurrence.

The FP prescribed topical erythromycin solution for the pitted keratolysis and topical 20% aluminum chloride for the hyperhidrosis. The physician also suggested that the patient wear a lighter and more breathable shoe until his condition improved.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Babcock M, Usatine R. Pitted keratolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:686-688.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed pitted keratolysis in addition to hyperhidrosis. Pitted keratolysis is a superficial foot infection caused by Gram-positive bacteria, including Kytococcus sedentarius, Corynebacterium species, and Dermatophilus congolensis.

These bacteria produce proteases that degrade the keratin of the stratum corneum, leaving visible pits on the soles of the feet. The associated malodor is likely secondary to the production of sulfur byproducts.

Pitted keratolysis is more common in men and is often a complication of hyperhidrosis. It’s associated with an itching and burning sensation in some patients. The condition usually involves the callused pressure-bearing areas of the foot, such as the heel, ball of the foot, or plantar great toe.

Treatment is based on eliminating bacteria and reducing the moist environment in which the bacteria thrive. Topical erythromycin or clindamycin solution can be applied twice daily until the condition resolves. It may take 3 to 4 weeks to clear the odor and skin lesions. Oral erythromycin is effective and may be considered if topical therapy fails. Treating underlying hyperhidrosis is also important to prevent recurrence.

The FP prescribed topical erythromycin solution for the pitted keratolysis and topical 20% aluminum chloride for the hyperhidrosis. The physician also suggested that the patient wear a lighter and more breathable shoe until his condition improved.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Babcock M, Usatine R. Pitted keratolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:686-688.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed pitted keratolysis in addition to hyperhidrosis. Pitted keratolysis is a superficial foot infection caused by Gram-positive bacteria, including Kytococcus sedentarius, Corynebacterium species, and Dermatophilus congolensis.

These bacteria produce proteases that degrade the keratin of the stratum corneum, leaving visible pits on the soles of the feet. The associated malodor is likely secondary to the production of sulfur byproducts.

Pitted keratolysis is more common in men and is often a complication of hyperhidrosis. It’s associated with an itching and burning sensation in some patients. The condition usually involves the callused pressure-bearing areas of the foot, such as the heel, ball of the foot, or plantar great toe.

Treatment is based on eliminating bacteria and reducing the moist environment in which the bacteria thrive. Topical erythromycin or clindamycin solution can be applied twice daily until the condition resolves. It may take 3 to 4 weeks to clear the odor and skin lesions. Oral erythromycin is effective and may be considered if topical therapy fails. Treating underlying hyperhidrosis is also important to prevent recurrence.

The FP prescribed topical erythromycin solution for the pitted keratolysis and topical 20% aluminum chloride for the hyperhidrosis. The physician also suggested that the patient wear a lighter and more breathable shoe until his condition improved.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Babcock M, Usatine R. Pitted keratolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:686-688.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Pruritic postpartum eruption

Four days after delivering a boy by cesarean section, a 24-year-old woman sought care at our gynecology emergency room for a diffuse skin eruption. She said that one day after delivery, she developed several pruritic lesions near the site of the surgical incision. She attributed this to the surgical tape, but within the next 24 hours, blisters began to develop elsewhere on her body.

On exam, we noted light pink papules and plaques—some with overlying tense bullae—in and around her umbilicus (FIGURE 1), as well as on her abdomen, lower extremities, and within the left third and fourth web space of her toes. There were no lesions in the oral mucosa or near the groin or genitalia.

Aside from this blistering skin eruption, our patient was recovering well after the C-section. Her postoperative medications included simethicone, prenatal vitamins with iron, ibuprofen, ferrous sulfate, stool softeners, and acetaminophen with codeine. She indicated that her newborn son didn’t have any health problems—skin or otherwise—and her 2 other sons were healthy. She had no significant medical or dermatologic history. We performed a skin biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pemphigoid gestationis

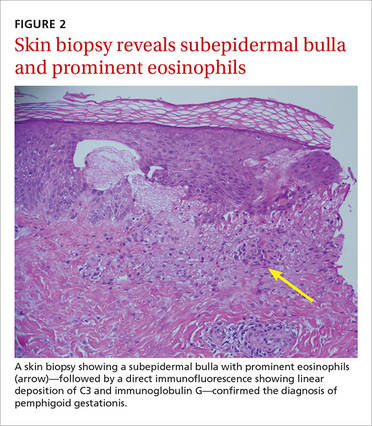

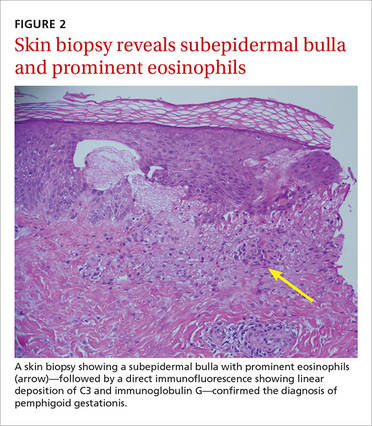

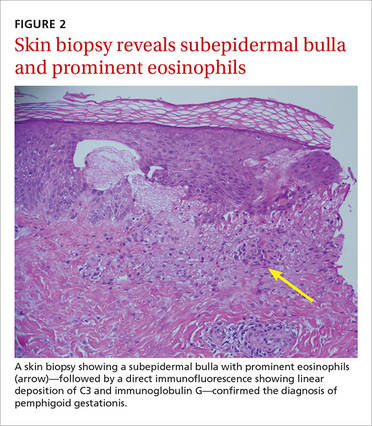

Based on the appearance of the lesions and the lab findings, we diagnosed our patient with pemphigoid gestationis (PG). The pathology demonstrated a subepidermal blister with prominent eosinophils, which supported the diagnosis (FIGURE 2). Direct immunofluorescence further supported the diagnosis, as it showed a thick, dense, and linear C3 deposition and weak immunoglobulin G deposition along the epidermal basement membrane zone.

PG, previously referred to as herpes gestationis, is a rare autoimmune dermatosis of pregnancy that usually presents with intense, pruritic, erythematous papules and blisters that surround the umbilicus. PG lesions spread rapidly throughout the body, but tend to spare the face and oral mucosa. The incidence is approximately 1 in 50,000 pregnancies.1

Although the exact pathogenesis of PG is unknown, it is hypothesized that major histocompatibility complex class II antigens within the placenta may play a role through cross-reaction with maternal skin.2

PG usually develops weeks to months before delivery

The onset of PG is usually during the second or third trimester; it typically manifests earlier and with greater severity in subsequent pregnancies.2 That said, postpartum cases and cases where PG “skipped” pregnancies have been reported.2 PG can impact the fetus—about 5% to 10% of infants born to affected mothers have a diffuse bullous eruption similar to that of PG.3 One study found a fetal mortality rate of up to 30% and high rates of prematurity.1

This case represents an interesting variation because the patient hadn’t developed any dermatologic conditions during her previous 2 pregnancies, and it was only after she delivered her third child that she developed PG. While there is a wide range of possible presentations of PG, all mothers who have it should be monitored by an obstetrician and should follow up with a dermatologist during their prenatal periods due to the small but significant risks of prematurity and fetal growth restriction.4

Reactivation of symptoms. Although PG symptoms typically resolve several weeks before delivery, 75% of patients experience reactivation of their symptoms at delivery.4 Progestin has immunosuppressive properties, and variations in progestin levels near delivery are thought to be responsible for the relapsing-remitting course of PG symptoms.4

Rule out other diagnoses with patch testing, skin biopsy

Pruritic and erythematous bullae and vesicles, particularly around the umbilicus, should raise clinical suspicion for PG in a pregnant patient. A skin biopsy showing a subepidermal bulla with prominent eosinophils, as well as direct immunofluorescence showing linear deposition of C3 and IgG at the dermo-epidermal junction, indicates a diagnosis of PG.

The differential diagnosis of PG includes urticarial/bullous drug eruptions, viral exanthems, allergic contact dermatitis, and pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP). Clinical correlation and a careful review of the patient’s medications, symptoms, and exposure to viruses can aid in ruling out a drug eruption or viral exanthema. Patch testing can be performed to rule out allergic contact dermatitis, and serum testing or indirect immunofluorescence or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is recommended to rule out PUPPP.

Treat with topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines

The goal of treatment for PG is to provide relief from the pruritus and to decrease and suppress blister formation. Topical corticosteroids, such as clobetasol or betamethasone, and systemic antihistamines, such as cetirizine, can be used to treat mild cases of PG. First-generation antihistamines are favored over second-generation antihistamines because of their increased safety when used during pregnancy.

Severe cases. Oral steroids are used for patients with more severe cases of PG. The preferred corticosteroid is prednisolone, typically starting at 20 to 40 mg/d or 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/d and adjusting as needed.5 For patients who do not respond to corticosteroids or for whom corticosteroids are contraindicated, intravenous immunoglobulins or plasmapheresis may be beneficial.5 If a patient requires postpartum treatment, the possibility of medications being passed through breast milk needs to be considered.

Our patient. We prescribed clobetasol 0.05% ointment for our patient and told her to apply it twice daily to the affected areas. We discussed the possibility of using a systemic corticosteroid, but she opted to use the topical medication exclusively because she was breastfeeding. Although our patient still gets an occasional blister when she is stressed, they go away 1 to 2 days after she applies the clobetasol ointment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarah Groff, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7979 Wurzbach Road, San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected].

1. Lawley TJ, Stingl G, Katz SI. Fetal and maternal risk factors in herpes gestationis. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:552-555.

2. Engineer L, Bhol K, Ahmed AR. Pemphigoid gestationis: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:483-491.

3. Katz A, Minto JO, Toole JW, et al. Immunopathologic study of herpes gestationis in mother and infant. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1069-1072.

4. Huilaja L, Mäkikallio K, Tasanen K. Gestational pemphigoid. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:136.

5. Jurecka W. Pregnancy dermatoses. In: Lebwohl MG, Berth-Jones J, Heymann WR, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:606-611.

Four days after delivering a boy by cesarean section, a 24-year-old woman sought care at our gynecology emergency room for a diffuse skin eruption. She said that one day after delivery, she developed several pruritic lesions near the site of the surgical incision. She attributed this to the surgical tape, but within the next 24 hours, blisters began to develop elsewhere on her body.

On exam, we noted light pink papules and plaques—some with overlying tense bullae—in and around her umbilicus (FIGURE 1), as well as on her abdomen, lower extremities, and within the left third and fourth web space of her toes. There were no lesions in the oral mucosa or near the groin or genitalia.

Aside from this blistering skin eruption, our patient was recovering well after the C-section. Her postoperative medications included simethicone, prenatal vitamins with iron, ibuprofen, ferrous sulfate, stool softeners, and acetaminophen with codeine. She indicated that her newborn son didn’t have any health problems—skin or otherwise—and her 2 other sons were healthy. She had no significant medical or dermatologic history. We performed a skin biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pemphigoid gestationis

Based on the appearance of the lesions and the lab findings, we diagnosed our patient with pemphigoid gestationis (PG). The pathology demonstrated a subepidermal blister with prominent eosinophils, which supported the diagnosis (FIGURE 2). Direct immunofluorescence further supported the diagnosis, as it showed a thick, dense, and linear C3 deposition and weak immunoglobulin G deposition along the epidermal basement membrane zone.

PG, previously referred to as herpes gestationis, is a rare autoimmune dermatosis of pregnancy that usually presents with intense, pruritic, erythematous papules and blisters that surround the umbilicus. PG lesions spread rapidly throughout the body, but tend to spare the face and oral mucosa. The incidence is approximately 1 in 50,000 pregnancies.1

Although the exact pathogenesis of PG is unknown, it is hypothesized that major histocompatibility complex class II antigens within the placenta may play a role through cross-reaction with maternal skin.2

PG usually develops weeks to months before delivery

The onset of PG is usually during the second or third trimester; it typically manifests earlier and with greater severity in subsequent pregnancies.2 That said, postpartum cases and cases where PG “skipped” pregnancies have been reported.2 PG can impact the fetus—about 5% to 10% of infants born to affected mothers have a diffuse bullous eruption similar to that of PG.3 One study found a fetal mortality rate of up to 30% and high rates of prematurity.1

This case represents an interesting variation because the patient hadn’t developed any dermatologic conditions during her previous 2 pregnancies, and it was only after she delivered her third child that she developed PG. While there is a wide range of possible presentations of PG, all mothers who have it should be monitored by an obstetrician and should follow up with a dermatologist during their prenatal periods due to the small but significant risks of prematurity and fetal growth restriction.4

Reactivation of symptoms. Although PG symptoms typically resolve several weeks before delivery, 75% of patients experience reactivation of their symptoms at delivery.4 Progestin has immunosuppressive properties, and variations in progestin levels near delivery are thought to be responsible for the relapsing-remitting course of PG symptoms.4

Rule out other diagnoses with patch testing, skin biopsy

Pruritic and erythematous bullae and vesicles, particularly around the umbilicus, should raise clinical suspicion for PG in a pregnant patient. A skin biopsy showing a subepidermal bulla with prominent eosinophils, as well as direct immunofluorescence showing linear deposition of C3 and IgG at the dermo-epidermal junction, indicates a diagnosis of PG.