User login

Blisters on thigh

The FP diagnosed the boy with herpes zoster that was found in multiple dermatomes. He did not think it was disseminated because it was still localized to one area and there were not 20 or more lesions outside the primary zoster. However, the FP was very concerned about HIV and the boy was tested. A rapid HIV test came back positive.

The FP discussed the results of his findings with the child's grandmother, who was now caring for the child. An attempt was made to obtain oral or intravenous acyclovir but it was not available in the village or local health center. The child was given oral liquid acetaminophen for the pain and was added to the list for the local HIV clinic. Fortunately, the zoster resolved without antiviral medications and the child began to receive care for his HIV infection.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Zoster. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:712-717.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed the boy with herpes zoster that was found in multiple dermatomes. He did not think it was disseminated because it was still localized to one area and there were not 20 or more lesions outside the primary zoster. However, the FP was very concerned about HIV and the boy was tested. A rapid HIV test came back positive.

The FP discussed the results of his findings with the child's grandmother, who was now caring for the child. An attempt was made to obtain oral or intravenous acyclovir but it was not available in the village or local health center. The child was given oral liquid acetaminophen for the pain and was added to the list for the local HIV clinic. Fortunately, the zoster resolved without antiviral medications and the child began to receive care for his HIV infection.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Zoster. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:712-717.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed the boy with herpes zoster that was found in multiple dermatomes. He did not think it was disseminated because it was still localized to one area and there were not 20 or more lesions outside the primary zoster. However, the FP was very concerned about HIV and the boy was tested. A rapid HIV test came back positive.

The FP discussed the results of his findings with the child's grandmother, who was now caring for the child. An attempt was made to obtain oral or intravenous acyclovir but it was not available in the village or local health center. The child was given oral liquid acetaminophen for the pain and was added to the list for the local HIV clinic. Fortunately, the zoster resolved without antiviral medications and the child began to receive care for his HIV infection.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Zoster. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:712-717.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Pruritic rash on 16-year-old girl

Despite the fact that some of the vesicles crossed the midline (which is suggestive of disseminated zoster), the FP felt confident in diagnosing herpes zoster (shingles) in this patient. The FP knew that the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) leaves the dorsal root ganglion to travel down the spinal nerves to the cutaneous nerves of the skin. But she also knew that the vesicles could cross the midline by a few centimeters because the posterior primary ramus of the spinal nerve includes a small cutaneous medial branch that reaches across the midline.1

After a primary infection with either chickenpox or vaccine-type VZV, a latent infection is established in the sensory dorsal root ganglia. Reactivation of this latent VZV infection results in herpes zoster. Both sensory ganglia neurons and satellite cells surrounding the neurons serve as sites of VZV latent infection. Once reactivated, the virus spreads to other cells within the ganglion. The dermatomal distribution of the rash corresponds to the sensory fields of the infected neurons within the specific ganglion.

The pain associated with zoster infections and postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is thought to result from injury to the peripheral nerves and altered central nervous system processing. PHN occurs more commonly in individuals older than age 60 and in immunosuppressed individuals. The lesions typically crust in approximately a week, with complete resolution within 3 to 4 weeks. If there are more than 20 lesions distributed outside the affected dermatome, the patient has disseminated zoster.

The treatment of herpes zoster includes antiviral agents, such as acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir. The evidence only supports their use if started within 72 hours of rash onset. Pain can be managed with nonprescription analgesics or narcotics and should be treated aggressively. This may actually prevent or lessen the severity of PHN.

The FP in this case was also concerned about whether the patient might be positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or have some type of immunosuppression. The patient denied sexual activity and use of intravenous drugs (even when her mom wasn’t in the room). She was otherwise healthy, so no further workup for HIV or immunosuppression was ordered. The FP told the teen to stay home from school until the lesions crusted over. A follow-up visit in one month was scheduled. The zoster resolved and the girl returned to her usual state of good health.

1. Usatine RP, Clemente C. Is herpes zoster unilateral? West J Med. 1999;170:263.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Zoster. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:712-717.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Despite the fact that some of the vesicles crossed the midline (which is suggestive of disseminated zoster), the FP felt confident in diagnosing herpes zoster (shingles) in this patient. The FP knew that the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) leaves the dorsal root ganglion to travel down the spinal nerves to the cutaneous nerves of the skin. But she also knew that the vesicles could cross the midline by a few centimeters because the posterior primary ramus of the spinal nerve includes a small cutaneous medial branch that reaches across the midline.1

After a primary infection with either chickenpox or vaccine-type VZV, a latent infection is established in the sensory dorsal root ganglia. Reactivation of this latent VZV infection results in herpes zoster. Both sensory ganglia neurons and satellite cells surrounding the neurons serve as sites of VZV latent infection. Once reactivated, the virus spreads to other cells within the ganglion. The dermatomal distribution of the rash corresponds to the sensory fields of the infected neurons within the specific ganglion.

The pain associated with zoster infections and postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is thought to result from injury to the peripheral nerves and altered central nervous system processing. PHN occurs more commonly in individuals older than age 60 and in immunosuppressed individuals. The lesions typically crust in approximately a week, with complete resolution within 3 to 4 weeks. If there are more than 20 lesions distributed outside the affected dermatome, the patient has disseminated zoster.

The treatment of herpes zoster includes antiviral agents, such as acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir. The evidence only supports their use if started within 72 hours of rash onset. Pain can be managed with nonprescription analgesics or narcotics and should be treated aggressively. This may actually prevent or lessen the severity of PHN.

The FP in this case was also concerned about whether the patient might be positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or have some type of immunosuppression. The patient denied sexual activity and use of intravenous drugs (even when her mom wasn’t in the room). She was otherwise healthy, so no further workup for HIV or immunosuppression was ordered. The FP told the teen to stay home from school until the lesions crusted over. A follow-up visit in one month was scheduled. The zoster resolved and the girl returned to her usual state of good health.

1. Usatine RP, Clemente C. Is herpes zoster unilateral? West J Med. 1999;170:263.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Zoster. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:712-717.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Despite the fact that some of the vesicles crossed the midline (which is suggestive of disseminated zoster), the FP felt confident in diagnosing herpes zoster (shingles) in this patient. The FP knew that the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) leaves the dorsal root ganglion to travel down the spinal nerves to the cutaneous nerves of the skin. But she also knew that the vesicles could cross the midline by a few centimeters because the posterior primary ramus of the spinal nerve includes a small cutaneous medial branch that reaches across the midline.1

After a primary infection with either chickenpox or vaccine-type VZV, a latent infection is established in the sensory dorsal root ganglia. Reactivation of this latent VZV infection results in herpes zoster. Both sensory ganglia neurons and satellite cells surrounding the neurons serve as sites of VZV latent infection. Once reactivated, the virus spreads to other cells within the ganglion. The dermatomal distribution of the rash corresponds to the sensory fields of the infected neurons within the specific ganglion.

The pain associated with zoster infections and postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is thought to result from injury to the peripheral nerves and altered central nervous system processing. PHN occurs more commonly in individuals older than age 60 and in immunosuppressed individuals. The lesions typically crust in approximately a week, with complete resolution within 3 to 4 weeks. If there are more than 20 lesions distributed outside the affected dermatome, the patient has disseminated zoster.

The treatment of herpes zoster includes antiviral agents, such as acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir. The evidence only supports their use if started within 72 hours of rash onset. Pain can be managed with nonprescription analgesics or narcotics and should be treated aggressively. This may actually prevent or lessen the severity of PHN.

The FP in this case was also concerned about whether the patient might be positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or have some type of immunosuppression. The patient denied sexual activity and use of intravenous drugs (even when her mom wasn’t in the room). She was otherwise healthy, so no further workup for HIV or immunosuppression was ordered. The FP told the teen to stay home from school until the lesions crusted over. A follow-up visit in one month was scheduled. The zoster resolved and the girl returned to her usual state of good health.

1. Usatine RP, Clemente C. Is herpes zoster unilateral? West J Med. 1999;170:263.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Zoster. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:712-717.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Rash on trunk

The FP diagnosed a varicella infection in this patient. The simultaneous appearance of papules, pustules, and crusted lesions on the patient’s trunk and face was highly suspicious for varicella, especially because there was no history of him receiving the varicella vaccine.

Varicella (chickenpox) is caused by a primary infection with the varicella zoster virus (VZV), which is a double-stranded, linear DNA herpes virus. Transmission occurs via contact with aerosolized droplets from nasopharyngeal secretions or by direct cutaneous contact with vesicle fluid from skin lesions. The incubation period for VZV is approximately 15 days, during which the virus undergoes replication in regional lymph nodes, followed by 2 viremic stages. In the first stage the virus spreads to internal organs, and in the second stage the virus spreads to the skin.

The vesicular rash appears in crops for several days and the lesions start as vesicles on a red base (classically described as a “dew drop on a rose petal”). The lesions gradually develop a pustular component followed by the evolution of crusted papules. The period of infectivity is generally considered to last from 48 hours prior to the onset of the rash until the skin lesions have fully crusted.

New varicella lesions stop forming in approximately 4 days, and most lesions become fully crusted by 7 days. Diagnosis is usually based on classic presentation. A culture of the lesions may provide a definitive diagnosis, but is positive in less than 40% of cases. Direct fluorescent antibody testing has good sensitivity and is more rapid than tissue culture. In this case, the diagnosis was made on clinical grounds.

Adults who get varicella should be assessed for neurologic and pulmonary disease; our patient showed no signs of either complication. Encephalitis is a serious potential complication of chickenpox that can develop toward the end of the first week of the exanthema. One form, acute cerebellar ataxia, occurs mostly in children and is generally followed by a complete recovery. In adults, a diffuse encephalitis can occur, and may produce delirium, seizures, and focal neurologic signs. It has significant rates of long-term neurologic sequelae and death.

Varicella pneumonia accounts for the majority of hospitalizations in adults with chickenpox, where it has up to a 30% mortality rate. It usually develops insidiously within a few days after the rash has appeared, with progressive tachypnea, dyspnea, and dry cough. Chest x-rays will reveal diffuse bilateral infiltrates. Varicella pneumonia requires prompt administration of intravenous acyclovir.

For adults with uncomplicated varicella, oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times/d for 5 days may be used for treatment if started within the first 24 hours of the rash. The patient in this case denied risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus, and because he lacked health insurance, he did not want any blood tests or medications unless they were absolutely necessary. He wanted to return to work but was told that he needed to wait until all his lesions had crusted over.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Chickenpox. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:707-711.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed a varicella infection in this patient. The simultaneous appearance of papules, pustules, and crusted lesions on the patient’s trunk and face was highly suspicious for varicella, especially because there was no history of him receiving the varicella vaccine.

Varicella (chickenpox) is caused by a primary infection with the varicella zoster virus (VZV), which is a double-stranded, linear DNA herpes virus. Transmission occurs via contact with aerosolized droplets from nasopharyngeal secretions or by direct cutaneous contact with vesicle fluid from skin lesions. The incubation period for VZV is approximately 15 days, during which the virus undergoes replication in regional lymph nodes, followed by 2 viremic stages. In the first stage the virus spreads to internal organs, and in the second stage the virus spreads to the skin.

The vesicular rash appears in crops for several days and the lesions start as vesicles on a red base (classically described as a “dew drop on a rose petal”). The lesions gradually develop a pustular component followed by the evolution of crusted papules. The period of infectivity is generally considered to last from 48 hours prior to the onset of the rash until the skin lesions have fully crusted.

New varicella lesions stop forming in approximately 4 days, and most lesions become fully crusted by 7 days. Diagnosis is usually based on classic presentation. A culture of the lesions may provide a definitive diagnosis, but is positive in less than 40% of cases. Direct fluorescent antibody testing has good sensitivity and is more rapid than tissue culture. In this case, the diagnosis was made on clinical grounds.

Adults who get varicella should be assessed for neurologic and pulmonary disease; our patient showed no signs of either complication. Encephalitis is a serious potential complication of chickenpox that can develop toward the end of the first week of the exanthema. One form, acute cerebellar ataxia, occurs mostly in children and is generally followed by a complete recovery. In adults, a diffuse encephalitis can occur, and may produce delirium, seizures, and focal neurologic signs. It has significant rates of long-term neurologic sequelae and death.

Varicella pneumonia accounts for the majority of hospitalizations in adults with chickenpox, where it has up to a 30% mortality rate. It usually develops insidiously within a few days after the rash has appeared, with progressive tachypnea, dyspnea, and dry cough. Chest x-rays will reveal diffuse bilateral infiltrates. Varicella pneumonia requires prompt administration of intravenous acyclovir.

For adults with uncomplicated varicella, oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times/d for 5 days may be used for treatment if started within the first 24 hours of the rash. The patient in this case denied risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus, and because he lacked health insurance, he did not want any blood tests or medications unless they were absolutely necessary. He wanted to return to work but was told that he needed to wait until all his lesions had crusted over.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Chickenpox. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:707-711.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed a varicella infection in this patient. The simultaneous appearance of papules, pustules, and crusted lesions on the patient’s trunk and face was highly suspicious for varicella, especially because there was no history of him receiving the varicella vaccine.

Varicella (chickenpox) is caused by a primary infection with the varicella zoster virus (VZV), which is a double-stranded, linear DNA herpes virus. Transmission occurs via contact with aerosolized droplets from nasopharyngeal secretions or by direct cutaneous contact with vesicle fluid from skin lesions. The incubation period for VZV is approximately 15 days, during which the virus undergoes replication in regional lymph nodes, followed by 2 viremic stages. In the first stage the virus spreads to internal organs, and in the second stage the virus spreads to the skin.

The vesicular rash appears in crops for several days and the lesions start as vesicles on a red base (classically described as a “dew drop on a rose petal”). The lesions gradually develop a pustular component followed by the evolution of crusted papules. The period of infectivity is generally considered to last from 48 hours prior to the onset of the rash until the skin lesions have fully crusted.

New varicella lesions stop forming in approximately 4 days, and most lesions become fully crusted by 7 days. Diagnosis is usually based on classic presentation. A culture of the lesions may provide a definitive diagnosis, but is positive in less than 40% of cases. Direct fluorescent antibody testing has good sensitivity and is more rapid than tissue culture. In this case, the diagnosis was made on clinical grounds.

Adults who get varicella should be assessed for neurologic and pulmonary disease; our patient showed no signs of either complication. Encephalitis is a serious potential complication of chickenpox that can develop toward the end of the first week of the exanthema. One form, acute cerebellar ataxia, occurs mostly in children and is generally followed by a complete recovery. In adults, a diffuse encephalitis can occur, and may produce delirium, seizures, and focal neurologic signs. It has significant rates of long-term neurologic sequelae and death.

Varicella pneumonia accounts for the majority of hospitalizations in adults with chickenpox, where it has up to a 30% mortality rate. It usually develops insidiously within a few days after the rash has appeared, with progressive tachypnea, dyspnea, and dry cough. Chest x-rays will reveal diffuse bilateral infiltrates. Varicella pneumonia requires prompt administration of intravenous acyclovir.

For adults with uncomplicated varicella, oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times/d for 5 days may be used for treatment if started within the first 24 hours of the rash. The patient in this case denied risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus, and because he lacked health insurance, he did not want any blood tests or medications unless they were absolutely necessary. He wanted to return to work but was told that he needed to wait until all his lesions had crusted over.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Chickenpox. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:707-711.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Patient with intractable nausea and vomiting

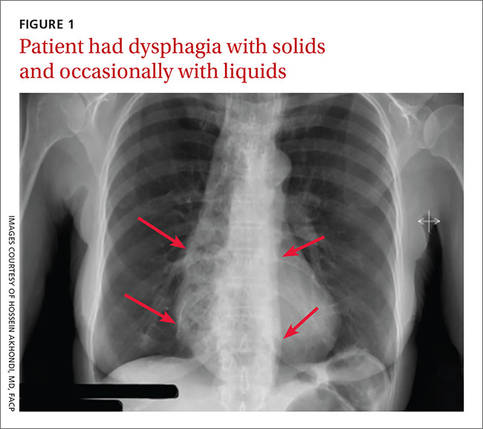

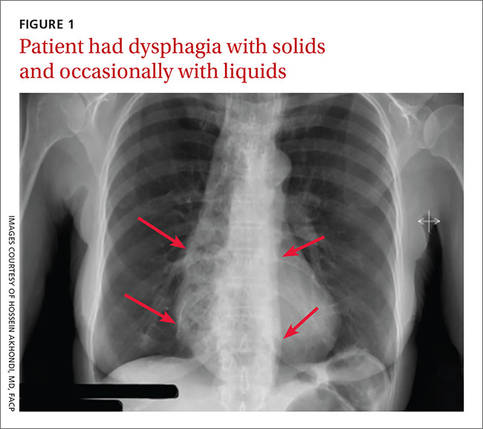

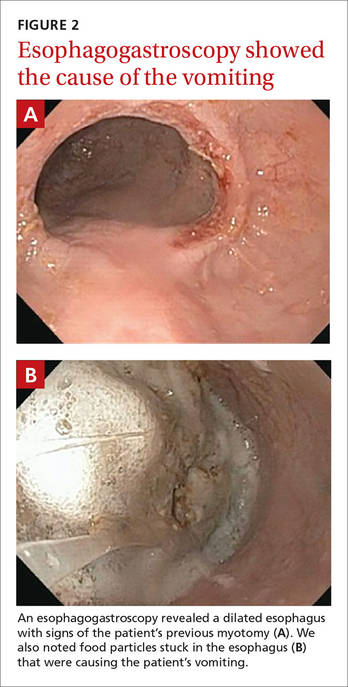

A 53-year-old African American woman was admitted to our hospital for intractable nausea and vomiting that she’d been experiencing for a month. She also reported dysphagia with solids and occasionally with liquids. She had no chest or abdominal pain, and no fever, bleeding, diarrhea, significant weight loss, or significant travel history. The patient was not taking any medication and her physical exam was normal. The patient’s complete blood count and electrolytes were normal. We ordered a chest x-ray (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

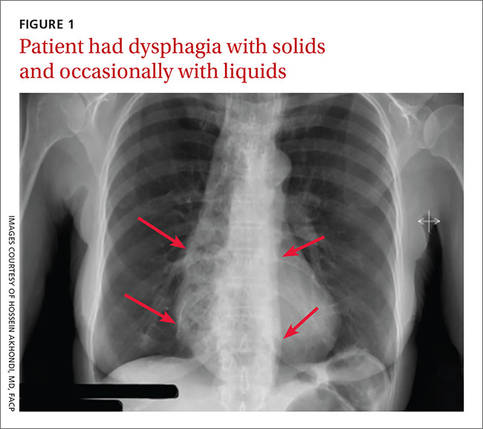

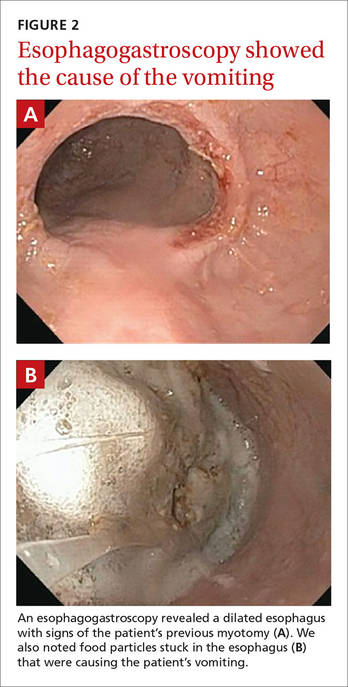

Diagnosis: Achalasia

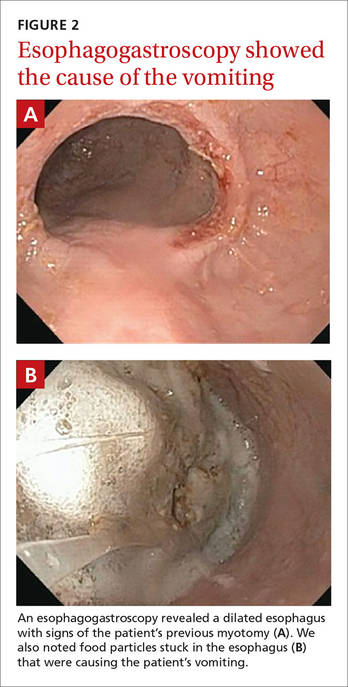

The radiologist who examined the x-ray noted a dilated esophagus (FIGURE 1, red arrows) with debris behind the heart shadow, which suggested achalasia. Upon further questioning, the patient reported a history of achalasia that had been treated with a myotomy 6 years ago. We performed an esophagogastroscopy, which showed a dilated esophagus with signs of the myotomy (FIGURE 2A), as well as food particles lodged in the esophagus (FIGURE 2B) that were causing the patient’s intractable vomiting.

Achalasia is a motor disorder of the esophagus smooth muscle in which the lower esophageal sphincter does not relax properly with swallowing, and the normal peristalsis of the esophagus body is replaced by abnormal contractions. Primary idiopathic achalasia is the most common form in the United States, but secondary forms caused by gastric carcinoma, lymphoma, or Chagas disease are also seen.1 The prevalence of achalasia is 1.6 per 100,000 in some populations.2 Symptoms can include dysphagia with solids and liquids, chest pain, and regurgitation.

A chest x-ray will show an absence of gastric air, and occasionally, as in this case, a tubular mass (the dilated esophagus) behind the heart and aorta. On fluoroscopy, the lower two-thirds of the esophagus does not have peristalsis and the terminal part has a bird beak appearance. Manometry will show normal or elevated pressure in the lower esophagus. Administration of cholinergic agonists will cause a marked increase in baseline pressure, as well as pain and regurgitation. Endoscopy can exclude secondary causes.

Narrowing the causes of dysphagia

The differential diagnosis is broad because there are 2 types of dysphagia: mechanical and neuromuscular.

Mechanical dysphagia is caused by a food bolus or foreign body, by intrinsic narrowing of the esophagus (from inflammation, esophageal webs, benign and malignant strictures, and tumors) or by extrinsic compression (from bone or thyroid abscesses or vascular tightening).

Neuromuscular dysphagia is either a swallowing reflex problem, a disorder of the pharyngeal and striated esophagus muscles, or an esophageal smooth muscle disorder.3 Close attention to the patient’s history and physical exam is key to zeroing in on the proper diagnosis.

On the other hand, food impaction in the esophagus almost always indicates certain etiologies. Benign esophageal stenosis caused by Schatzki rings (B rings) or by peptic strictures is the most common cause of food impaction, followed by esophageal webs, extrinsic compression, surgical anastomosis, esophagitis (eg, eosinophilic esophagitis), and motor disorders, such as achalasia.

First-line therapy is surgery; pharmacologic Tx is least effective

Treatment should be individualized by age, gender, and patient preference; however, there is no definitive treatment for this condition. First-line therapy includes graded pneumatic dilation or laparoscopic myotomy with a partial fundoplication.4 Botulinum toxin injection in the lower esophageal sphincter is recommended for patients who are not good candidates for surgery or dilation.5

Pharmacologic therapy, the least effective treatment option, is recommended for patients who are unwilling or unable to undergo myotomy and/or dilation and do not respond to botulinum toxin.6,7 Long-acting nitrates such as isosorbide, calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine, and phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors such as sildenafil reduce lower esophageal sphincter tone and pressure.

Both nifedipine and isosorbide should be taken sublingually before meals (30 minutes and 10 minutes, respectively). The effects of nifedipine and isosorbide, however, are partial, and these agents do not provide complete relief from symptoms.6 PDE5 use has been limited and results are inconclusive.

Our patient. The food particles in the patient’s esophagus were removed during endoscopy, and she stopped vomiting completely. Based on the findings and clinical picture, the patient most likely suffered from mega-esophagus (an end-stage dilated malfunctioning esophagus). Our patient was discharged to follow-up with her gastroenterologist.

Because there is no definitive treatment for achalasia, the patient was counseled about the need for continuous monitoring and dietary precautions, including modification of food texture or change of fluid viscosity. Food may be chopped, minced, or pureed, and fluids may be thickened.

CORRESPONDENCE

Hossein Akhondi, MD, FACP, Georgetown University, 1010 Mass Ave, NW, Unit 904, Washington, DC 20001; [email protected].

1. Richter JE. Esophageal motility disorder achalasia. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;21:535-542.

2. O’Neill OM, Johnston BT, Coleman HG. Achalasia: a review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5806-5812.

3. Ott R, Bajbouj M, Feussner H, et al. [Dysphagia—what is important for primary diagnosis in private practice?]. MMW Fortschr Med. 2014;156:54-57.

4. Yaghoobi M. Treatment of patients with new diagnosis of achalasia: laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy may be more effective than pneumatic dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:360.

5. Blatnik JA, Ponsky JL. Advances in the treatment of achalasia. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2014;12:49-58.

6. Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1238-1249.

7. Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Current therapies for achalasia: comparison and efficacy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:21-35.

A 53-year-old African American woman was admitted to our hospital for intractable nausea and vomiting that she’d been experiencing for a month. She also reported dysphagia with solids and occasionally with liquids. She had no chest or abdominal pain, and no fever, bleeding, diarrhea, significant weight loss, or significant travel history. The patient was not taking any medication and her physical exam was normal. The patient’s complete blood count and electrolytes were normal. We ordered a chest x-ray (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Achalasia

The radiologist who examined the x-ray noted a dilated esophagus (FIGURE 1, red arrows) with debris behind the heart shadow, which suggested achalasia. Upon further questioning, the patient reported a history of achalasia that had been treated with a myotomy 6 years ago. We performed an esophagogastroscopy, which showed a dilated esophagus with signs of the myotomy (FIGURE 2A), as well as food particles lodged in the esophagus (FIGURE 2B) that were causing the patient’s intractable vomiting.

Achalasia is a motor disorder of the esophagus smooth muscle in which the lower esophageal sphincter does not relax properly with swallowing, and the normal peristalsis of the esophagus body is replaced by abnormal contractions. Primary idiopathic achalasia is the most common form in the United States, but secondary forms caused by gastric carcinoma, lymphoma, or Chagas disease are also seen.1 The prevalence of achalasia is 1.6 per 100,000 in some populations.2 Symptoms can include dysphagia with solids and liquids, chest pain, and regurgitation.

A chest x-ray will show an absence of gastric air, and occasionally, as in this case, a tubular mass (the dilated esophagus) behind the heart and aorta. On fluoroscopy, the lower two-thirds of the esophagus does not have peristalsis and the terminal part has a bird beak appearance. Manometry will show normal or elevated pressure in the lower esophagus. Administration of cholinergic agonists will cause a marked increase in baseline pressure, as well as pain and regurgitation. Endoscopy can exclude secondary causes.

Narrowing the causes of dysphagia

The differential diagnosis is broad because there are 2 types of dysphagia: mechanical and neuromuscular.

Mechanical dysphagia is caused by a food bolus or foreign body, by intrinsic narrowing of the esophagus (from inflammation, esophageal webs, benign and malignant strictures, and tumors) or by extrinsic compression (from bone or thyroid abscesses or vascular tightening).

Neuromuscular dysphagia is either a swallowing reflex problem, a disorder of the pharyngeal and striated esophagus muscles, or an esophageal smooth muscle disorder.3 Close attention to the patient’s history and physical exam is key to zeroing in on the proper diagnosis.

On the other hand, food impaction in the esophagus almost always indicates certain etiologies. Benign esophageal stenosis caused by Schatzki rings (B rings) or by peptic strictures is the most common cause of food impaction, followed by esophageal webs, extrinsic compression, surgical anastomosis, esophagitis (eg, eosinophilic esophagitis), and motor disorders, such as achalasia.

First-line therapy is surgery; pharmacologic Tx is least effective

Treatment should be individualized by age, gender, and patient preference; however, there is no definitive treatment for this condition. First-line therapy includes graded pneumatic dilation or laparoscopic myotomy with a partial fundoplication.4 Botulinum toxin injection in the lower esophageal sphincter is recommended for patients who are not good candidates for surgery or dilation.5

Pharmacologic therapy, the least effective treatment option, is recommended for patients who are unwilling or unable to undergo myotomy and/or dilation and do not respond to botulinum toxin.6,7 Long-acting nitrates such as isosorbide, calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine, and phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors such as sildenafil reduce lower esophageal sphincter tone and pressure.

Both nifedipine and isosorbide should be taken sublingually before meals (30 minutes and 10 minutes, respectively). The effects of nifedipine and isosorbide, however, are partial, and these agents do not provide complete relief from symptoms.6 PDE5 use has been limited and results are inconclusive.

Our patient. The food particles in the patient’s esophagus were removed during endoscopy, and she stopped vomiting completely. Based on the findings and clinical picture, the patient most likely suffered from mega-esophagus (an end-stage dilated malfunctioning esophagus). Our patient was discharged to follow-up with her gastroenterologist.

Because there is no definitive treatment for achalasia, the patient was counseled about the need for continuous monitoring and dietary precautions, including modification of food texture or change of fluid viscosity. Food may be chopped, minced, or pureed, and fluids may be thickened.

CORRESPONDENCE

Hossein Akhondi, MD, FACP, Georgetown University, 1010 Mass Ave, NW, Unit 904, Washington, DC 20001; [email protected].

A 53-year-old African American woman was admitted to our hospital for intractable nausea and vomiting that she’d been experiencing for a month. She also reported dysphagia with solids and occasionally with liquids. She had no chest or abdominal pain, and no fever, bleeding, diarrhea, significant weight loss, or significant travel history. The patient was not taking any medication and her physical exam was normal. The patient’s complete blood count and electrolytes were normal. We ordered a chest x-ray (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Achalasia

The radiologist who examined the x-ray noted a dilated esophagus (FIGURE 1, red arrows) with debris behind the heart shadow, which suggested achalasia. Upon further questioning, the patient reported a history of achalasia that had been treated with a myotomy 6 years ago. We performed an esophagogastroscopy, which showed a dilated esophagus with signs of the myotomy (FIGURE 2A), as well as food particles lodged in the esophagus (FIGURE 2B) that were causing the patient’s intractable vomiting.

Achalasia is a motor disorder of the esophagus smooth muscle in which the lower esophageal sphincter does not relax properly with swallowing, and the normal peristalsis of the esophagus body is replaced by abnormal contractions. Primary idiopathic achalasia is the most common form in the United States, but secondary forms caused by gastric carcinoma, lymphoma, or Chagas disease are also seen.1 The prevalence of achalasia is 1.6 per 100,000 in some populations.2 Symptoms can include dysphagia with solids and liquids, chest pain, and regurgitation.

A chest x-ray will show an absence of gastric air, and occasionally, as in this case, a tubular mass (the dilated esophagus) behind the heart and aorta. On fluoroscopy, the lower two-thirds of the esophagus does not have peristalsis and the terminal part has a bird beak appearance. Manometry will show normal or elevated pressure in the lower esophagus. Administration of cholinergic agonists will cause a marked increase in baseline pressure, as well as pain and regurgitation. Endoscopy can exclude secondary causes.

Narrowing the causes of dysphagia

The differential diagnosis is broad because there are 2 types of dysphagia: mechanical and neuromuscular.

Mechanical dysphagia is caused by a food bolus or foreign body, by intrinsic narrowing of the esophagus (from inflammation, esophageal webs, benign and malignant strictures, and tumors) or by extrinsic compression (from bone or thyroid abscesses or vascular tightening).

Neuromuscular dysphagia is either a swallowing reflex problem, a disorder of the pharyngeal and striated esophagus muscles, or an esophageal smooth muscle disorder.3 Close attention to the patient’s history and physical exam is key to zeroing in on the proper diagnosis.

On the other hand, food impaction in the esophagus almost always indicates certain etiologies. Benign esophageal stenosis caused by Schatzki rings (B rings) or by peptic strictures is the most common cause of food impaction, followed by esophageal webs, extrinsic compression, surgical anastomosis, esophagitis (eg, eosinophilic esophagitis), and motor disorders, such as achalasia.

First-line therapy is surgery; pharmacologic Tx is least effective

Treatment should be individualized by age, gender, and patient preference; however, there is no definitive treatment for this condition. First-line therapy includes graded pneumatic dilation or laparoscopic myotomy with a partial fundoplication.4 Botulinum toxin injection in the lower esophageal sphincter is recommended for patients who are not good candidates for surgery or dilation.5

Pharmacologic therapy, the least effective treatment option, is recommended for patients who are unwilling or unable to undergo myotomy and/or dilation and do not respond to botulinum toxin.6,7 Long-acting nitrates such as isosorbide, calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine, and phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors such as sildenafil reduce lower esophageal sphincter tone and pressure.

Both nifedipine and isosorbide should be taken sublingually before meals (30 minutes and 10 minutes, respectively). The effects of nifedipine and isosorbide, however, are partial, and these agents do not provide complete relief from symptoms.6 PDE5 use has been limited and results are inconclusive.

Our patient. The food particles in the patient’s esophagus were removed during endoscopy, and she stopped vomiting completely. Based on the findings and clinical picture, the patient most likely suffered from mega-esophagus (an end-stage dilated malfunctioning esophagus). Our patient was discharged to follow-up with her gastroenterologist.

Because there is no definitive treatment for achalasia, the patient was counseled about the need for continuous monitoring and dietary precautions, including modification of food texture or change of fluid viscosity. Food may be chopped, minced, or pureed, and fluids may be thickened.

CORRESPONDENCE

Hossein Akhondi, MD, FACP, Georgetown University, 1010 Mass Ave, NW, Unit 904, Washington, DC 20001; [email protected].

1. Richter JE. Esophageal motility disorder achalasia. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;21:535-542.

2. O’Neill OM, Johnston BT, Coleman HG. Achalasia: a review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5806-5812.

3. Ott R, Bajbouj M, Feussner H, et al. [Dysphagia—what is important for primary diagnosis in private practice?]. MMW Fortschr Med. 2014;156:54-57.

4. Yaghoobi M. Treatment of patients with new diagnosis of achalasia: laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy may be more effective than pneumatic dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:360.

5. Blatnik JA, Ponsky JL. Advances in the treatment of achalasia. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2014;12:49-58.

6. Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1238-1249.

7. Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Current therapies for achalasia: comparison and efficacy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:21-35.

1. Richter JE. Esophageal motility disorder achalasia. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;21:535-542.

2. O’Neill OM, Johnston BT, Coleman HG. Achalasia: a review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5806-5812.

3. Ott R, Bajbouj M, Feussner H, et al. [Dysphagia—what is important for primary diagnosis in private practice?]. MMW Fortschr Med. 2014;156:54-57.

4. Yaghoobi M. Treatment of patients with new diagnosis of achalasia: laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy may be more effective than pneumatic dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:360.

5. Blatnik JA, Ponsky JL. Advances in the treatment of achalasia. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2014;12:49-58.

6. Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1238-1249.

7. Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Current therapies for achalasia: comparison and efficacy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:21-35.

Painful area above cesarean scar

The ED physician suspected necrotizing fasciitis (NF) and immediately called for a surgical consult. This patient had type II NF, which can be caused by common skin organisms, such as Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus.

Surgical debridement is the primary therapeutic modality. If the first debridement occurs within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms, there is a significantly improved chance of survival. Extensive, definitive debridement should be the goal with the first surgery. This may require amputation of an extremity to control the disease. Surgical debridement is repeated until all infected devitalized tissue is removed.

Antibiotics are the main adjunctive therapy to surgery. Broad-spectrum empiric antibiotics should be started immediately when NF is suspected and should include coverage of Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms. Antimicrobial therapy must be directed at the known or suspected pathogens and used in appropriate doses until repeated operative procedures are no longer needed. Empiric vancomycin should be considered while awaiting culture results to cover for the increasing incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Aggressive fluid resuscitation is often necessary because of massive capillary leak syndrome.

In this case, the patient was started on empiric broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics to cover Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms. The surgical team then rapidly admitted the patient to the operating room (OR) for debridement. From the OR, she was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit where she received ongoing supportive and postoperative care. The intraoperative tissue cultures grew out MRSA.

The patient in this case was fortunate. She survived because of the speed with which she received a proper diagnosis and treatment.

Photo courtesy of Michael Babcock, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Franklin J. Necrotizing fasciitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:702-706.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The ED physician suspected necrotizing fasciitis (NF) and immediately called for a surgical consult. This patient had type II NF, which can be caused by common skin organisms, such as Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus.

Surgical debridement is the primary therapeutic modality. If the first debridement occurs within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms, there is a significantly improved chance of survival. Extensive, definitive debridement should be the goal with the first surgery. This may require amputation of an extremity to control the disease. Surgical debridement is repeated until all infected devitalized tissue is removed.

Antibiotics are the main adjunctive therapy to surgery. Broad-spectrum empiric antibiotics should be started immediately when NF is suspected and should include coverage of Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms. Antimicrobial therapy must be directed at the known or suspected pathogens and used in appropriate doses until repeated operative procedures are no longer needed. Empiric vancomycin should be considered while awaiting culture results to cover for the increasing incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Aggressive fluid resuscitation is often necessary because of massive capillary leak syndrome.

In this case, the patient was started on empiric broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics to cover Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms. The surgical team then rapidly admitted the patient to the operating room (OR) for debridement. From the OR, she was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit where she received ongoing supportive and postoperative care. The intraoperative tissue cultures grew out MRSA.

The patient in this case was fortunate. She survived because of the speed with which she received a proper diagnosis and treatment.

Photo courtesy of Michael Babcock, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Franklin J. Necrotizing fasciitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:702-706.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The ED physician suspected necrotizing fasciitis (NF) and immediately called for a surgical consult. This patient had type II NF, which can be caused by common skin organisms, such as Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus.

Surgical debridement is the primary therapeutic modality. If the first debridement occurs within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms, there is a significantly improved chance of survival. Extensive, definitive debridement should be the goal with the first surgery. This may require amputation of an extremity to control the disease. Surgical debridement is repeated until all infected devitalized tissue is removed.

Antibiotics are the main adjunctive therapy to surgery. Broad-spectrum empiric antibiotics should be started immediately when NF is suspected and should include coverage of Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms. Antimicrobial therapy must be directed at the known or suspected pathogens and used in appropriate doses until repeated operative procedures are no longer needed. Empiric vancomycin should be considered while awaiting culture results to cover for the increasing incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Aggressive fluid resuscitation is often necessary because of massive capillary leak syndrome.

In this case, the patient was started on empiric broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics to cover Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms. The surgical team then rapidly admitted the patient to the operating room (OR) for debridement. From the OR, she was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit where she received ongoing supportive and postoperative care. The intraoperative tissue cultures grew out MRSA.

The patient in this case was fortunate. She survived because of the speed with which she received a proper diagnosis and treatment.

Photo courtesy of Michael Babcock, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Franklin J. Necrotizing fasciitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:702-706.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Swollen, painful leg

The ED physician suspected necrotizing fasciitis (NF), a rapidly progressive infection of the deep fascia with necrosis of the subcutaneous tissues. It usually occurs after surgery or trauma. Patients have erythema and pain disproportionate to the physical findings.

This patient had type I NF, a polymicrobial infection with aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. It is frequently caused by enteric Gram-negative pathogens including Enterobacteriaceae organisms and Bacteroides. It can also occur with Gram-positive organisms such as non–group A streptococci and Peptostreptococcus.

Risk factors for type I NF include diabetes, severe peripheral vascular disease, obesity, alcoholism, cirrhosis, intravenous drug use, decubitus ulcers, poor nutritional status, surgery, and penetrating trauma. Early recognition based on signs and symptoms is potentially lifesaving. Although lab tests and imaging studies can confirm one’s clinical impression, rapid treatment with antibiotics and surgery are crucial to improving survival.

The patient in this case was taken to the operating room for debridement of her NF. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were started, but the infection continued to quickly advance. The patient died the following day. Her wound culture later grew Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris, Corynebacterium, Enterococcus, Staphylococcus sp., and Peptostreptococcus.

Adapted from: Dufel S, Martino M. Simple cellulitis or a more serious infection? J Fam Pract. 2006;55:396-400.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The ED physician suspected necrotizing fasciitis (NF), a rapidly progressive infection of the deep fascia with necrosis of the subcutaneous tissues. It usually occurs after surgery or trauma. Patients have erythema and pain disproportionate to the physical findings.

This patient had type I NF, a polymicrobial infection with aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. It is frequently caused by enteric Gram-negative pathogens including Enterobacteriaceae organisms and Bacteroides. It can also occur with Gram-positive organisms such as non–group A streptococci and Peptostreptococcus.

Risk factors for type I NF include diabetes, severe peripheral vascular disease, obesity, alcoholism, cirrhosis, intravenous drug use, decubitus ulcers, poor nutritional status, surgery, and penetrating trauma. Early recognition based on signs and symptoms is potentially lifesaving. Although lab tests and imaging studies can confirm one’s clinical impression, rapid treatment with antibiotics and surgery are crucial to improving survival.

The patient in this case was taken to the operating room for debridement of her NF. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were started, but the infection continued to quickly advance. The patient died the following day. Her wound culture later grew Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris, Corynebacterium, Enterococcus, Staphylococcus sp., and Peptostreptococcus.

Adapted from: Dufel S, Martino M. Simple cellulitis or a more serious infection? J Fam Pract. 2006;55:396-400.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The ED physician suspected necrotizing fasciitis (NF), a rapidly progressive infection of the deep fascia with necrosis of the subcutaneous tissues. It usually occurs after surgery or trauma. Patients have erythema and pain disproportionate to the physical findings.

This patient had type I NF, a polymicrobial infection with aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. It is frequently caused by enteric Gram-negative pathogens including Enterobacteriaceae organisms and Bacteroides. It can also occur with Gram-positive organisms such as non–group A streptococci and Peptostreptococcus.

Risk factors for type I NF include diabetes, severe peripheral vascular disease, obesity, alcoholism, cirrhosis, intravenous drug use, decubitus ulcers, poor nutritional status, surgery, and penetrating trauma. Early recognition based on signs and symptoms is potentially lifesaving. Although lab tests and imaging studies can confirm one’s clinical impression, rapid treatment with antibiotics and surgery are crucial to improving survival.

The patient in this case was taken to the operating room for debridement of her NF. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were started, but the infection continued to quickly advance. The patient died the following day. Her wound culture later grew Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris, Corynebacterium, Enterococcus, Staphylococcus sp., and Peptostreptococcus.

Adapted from: Dufel S, Martino M. Simple cellulitis or a more serious infection? J Fam Pract. 2006;55:396-400.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Swollen neck

The physician recognized that his patient had a neck abscess that was likely related to a dental abscess (odontogenic abscess). The patient’s alcoholism most likely weakened his ability to fight the infection, causing it to become potentially life-threatening. Risk factors for abscess formation include intravenous drug abuse, alcoholism, homelessness, dental disease, contact sports, and incarceration.

The physician transferred the patient to the local emergency department for hospitalization under the care of the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) service. The ENT physicians drained the abscess in the operating room without any complications. They cultured the abscess and started the patient on appropriate antibiotics, including penicillin G for dental aerobes and anaerobes.

The hospital team observed the patient for signs of alcohol withdrawal, but there were no complications because the patient hadn’t been drinking for the 5 days prior to hospitalization. Social Services was consulted and the patient was discharged to a respite bed in a local shelter that also had an alcohol and drug rehabilitation program. Arrangements were made for dental work in a charity dental clinic.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Abscess. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:698-701.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The physician recognized that his patient had a neck abscess that was likely related to a dental abscess (odontogenic abscess). The patient’s alcoholism most likely weakened his ability to fight the infection, causing it to become potentially life-threatening. Risk factors for abscess formation include intravenous drug abuse, alcoholism, homelessness, dental disease, contact sports, and incarceration.

The physician transferred the patient to the local emergency department for hospitalization under the care of the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) service. The ENT physicians drained the abscess in the operating room without any complications. They cultured the abscess and started the patient on appropriate antibiotics, including penicillin G for dental aerobes and anaerobes.

The hospital team observed the patient for signs of alcohol withdrawal, but there were no complications because the patient hadn’t been drinking for the 5 days prior to hospitalization. Social Services was consulted and the patient was discharged to a respite bed in a local shelter that also had an alcohol and drug rehabilitation program. Arrangements were made for dental work in a charity dental clinic.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Abscess. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:698-701.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The physician recognized that his patient had a neck abscess that was likely related to a dental abscess (odontogenic abscess). The patient’s alcoholism most likely weakened his ability to fight the infection, causing it to become potentially life-threatening. Risk factors for abscess formation include intravenous drug abuse, alcoholism, homelessness, dental disease, contact sports, and incarceration.

The physician transferred the patient to the local emergency department for hospitalization under the care of the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) service. The ENT physicians drained the abscess in the operating room without any complications. They cultured the abscess and started the patient on appropriate antibiotics, including penicillin G for dental aerobes and anaerobes.

The hospital team observed the patient for signs of alcohol withdrawal, but there were no complications because the patient hadn’t been drinking for the 5 days prior to hospitalization. Social Services was consulted and the patient was discharged to a respite bed in a local shelter that also had an alcohol and drug rehabilitation program. Arrangements were made for dental work in a charity dental clinic.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Abscess. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:698-701.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Tender, red thigh

The FP diagnosed an abscess with some surrounding cellulitis. An abscess is a collection of pus in infected tissue. The abscess represents a walled-off infection in which there is a pocket of purulence. In abscesses of the skin, the offending organism is almost always Staphylococcus aureus. In 2004, methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) was the most common identifiable cause of skin and soft-tissue infections among patients presenting to emergency departments in 11 US cities. S aureus was isolated from 76% of these infections and 59% of the infections were community-acquired MRSA.

A clinical cure is often obtained with incision and drainage alone. It is reasonable to obtain wound cultures in high-risk patients, those with signs of systemic infection, and in patients with a history of high recurrence rates.

While the patient’s abscess was beginning to drain spontaneously, it needed to drain some more. The FP performed an incision and drained more than 10 mL of pus. The large abscess cavity was packed with non-iodinated gauze (there is no benefit to iodinated gauze and iodine can be toxic to open tissues). The patient was placed on trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole DS (double strength) twice daily to cover the surrounding cellulitis. His diabetes medications were renewed and he was reminded of the importance of taking (and not skipping) these important medicines.

When the patient returned 2 days later, the erythema was gone and the packing was removed. The patient was feeling much better and his blood sugar was down to 150 mg/dL. The FP inserted a small amount of packing and told the patient that he could remove it himself in 2 days while in the shower. The patient’s culture grew out MRSA sensitive to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Two weeks later the patient was fully healed, with only a small scar from the incision remaining.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Abscess. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:698-701.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed an abscess with some surrounding cellulitis. An abscess is a collection of pus in infected tissue. The abscess represents a walled-off infection in which there is a pocket of purulence. In abscesses of the skin, the offending organism is almost always Staphylococcus aureus. In 2004, methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) was the most common identifiable cause of skin and soft-tissue infections among patients presenting to emergency departments in 11 US cities. S aureus was isolated from 76% of these infections and 59% of the infections were community-acquired MRSA.

A clinical cure is often obtained with incision and drainage alone. It is reasonable to obtain wound cultures in high-risk patients, those with signs of systemic infection, and in patients with a history of high recurrence rates.

While the patient’s abscess was beginning to drain spontaneously, it needed to drain some more. The FP performed an incision and drained more than 10 mL of pus. The large abscess cavity was packed with non-iodinated gauze (there is no benefit to iodinated gauze and iodine can be toxic to open tissues). The patient was placed on trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole DS (double strength) twice daily to cover the surrounding cellulitis. His diabetes medications were renewed and he was reminded of the importance of taking (and not skipping) these important medicines.

When the patient returned 2 days later, the erythema was gone and the packing was removed. The patient was feeling much better and his blood sugar was down to 150 mg/dL. The FP inserted a small amount of packing and told the patient that he could remove it himself in 2 days while in the shower. The patient’s culture grew out MRSA sensitive to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Two weeks later the patient was fully healed, with only a small scar from the incision remaining.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Abscess. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:698-701.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed an abscess with some surrounding cellulitis. An abscess is a collection of pus in infected tissue. The abscess represents a walled-off infection in which there is a pocket of purulence. In abscesses of the skin, the offending organism is almost always Staphylococcus aureus. In 2004, methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) was the most common identifiable cause of skin and soft-tissue infections among patients presenting to emergency departments in 11 US cities. S aureus was isolated from 76% of these infections and 59% of the infections were community-acquired MRSA.

A clinical cure is often obtained with incision and drainage alone. It is reasonable to obtain wound cultures in high-risk patients, those with signs of systemic infection, and in patients with a history of high recurrence rates.

While the patient’s abscess was beginning to drain spontaneously, it needed to drain some more. The FP performed an incision and drained more than 10 mL of pus. The large abscess cavity was packed with non-iodinated gauze (there is no benefit to iodinated gauze and iodine can be toxic to open tissues). The patient was placed on trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole DS (double strength) twice daily to cover the surrounding cellulitis. His diabetes medications were renewed and he was reminded of the importance of taking (and not skipping) these important medicines.

When the patient returned 2 days later, the erythema was gone and the packing was removed. The patient was feeling much better and his blood sugar was down to 150 mg/dL. The FP inserted a small amount of packing and told the patient that he could remove it himself in 2 days while in the shower. The patient’s culture grew out MRSA sensitive to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Two weeks later the patient was fully healed, with only a small scar from the incision remaining.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Abscess. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:698-701.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Vulvar pain in pregnancy

A 30-year-old pregnant woman presented to a rural Panamanian hospital with new onset genital pain, vaginal itching, and dysuria that she’d had for 48 hours. The patient was in the first trimester of her pregnancy and indicated that she’d had recent unprotected sex with a new partner who wasn’t the father of the developing fetus. The patient had never experienced symptoms like these before and denied ever having a sexually transmitted infection (STI). On physical exam, the physician noted numerous pustules covering tender, swollen labia (FIGURE). A small amount of white discharge was noted at the introitus.

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes simplex virus

The physician on-call diagnosed candida vaginitis along with a bacterial skin infection, and admitted the patient to the hospital for intravenous (IV) antibiotics. Fortunately, we were there on a medical mission and were consulted on the case.

We diagnosed a primary herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection in this patient, based on the classic presentation of grouped pustules and vesicles on erythematous and swollen labia, and the patient’s complaint of dysuria.

Herpes cultures weren’t available in the hospital, but the clinical picture was unmistakable for HSV infection. Since multiple STIs may occur simultaneously, we ordered a serum rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test for syphilis, and tested her urine for gonorrhea and chlamydia. The tests were negative.

Differential Dx includes other STIs and a fixed drug eruption

Herpes is a common STI and most people don’t have symptoms. In 2012, an estimated 417 million people worldwide were living with genital herpes caused by HSV-2.1

The differential diagnosis for HSV infection includes primary syphilis, chancroid, folliculitis, and fixed drug eruptions.

Primary syphilis (Treponema pallidum) commonly presents with a painless, ulcerated, clean-based ulcer. While the chancre of primary syphilis can sometimes be painful, this patient did not have ulcers at the time of her presentation. Her pustules would likely ulcerate over time, but would not resemble the chancre of syphilis.

Chancroid (Haemophilus ducreyi) is a less common STI than syphilis and HSV infection. It presents with deep, sharply defined, purulent ulcers that are often associated with painful adenopathy. The ulcers can appear grey or yellowish in color.

Folliculitis presents with pustules surrounding hair follicles. Some of the pustules were surrounding hair follicles in this patient’s case, but others were independent of the hair. The patient’s marked swelling and tenderness along with dysuria also did not fit the characteristics of folliculitis.

Fixed drug eruptions can occur in the genital region, but the patient had neither bullous nor ulcerated eruptions (as one would expect with this condition). Fixed drug eruptions are usually hyperpigmented and require a history of taking medication, such as an antibiotic or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Questions that help narrow the differential. Zeroing in on the cause of a patient’s genital lesions requires that you ask whether the lesions are painful, if the patient has dysuria, if there are any constitutional symptoms, and if this has happened before. Other distinguishing factors include enlarged lymph nodes and the presence of multiple (vs single) lesions.

Viral cell cultures are the preferred lab test

Common laboratory tests to make the diagnosis include viral culture, direct fluorescence antibody (DFA), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and type-specific serologic tests.

Viral cell culture is the preferred test for suspected HSV of the skin and mucous membranes.2 PCR is the preferred test for suspected herpes meningitis or encephalitis when cerebrospinal fluid has been obtained through lumbar puncture.3 DFA and herpes culture can be ordered simultaneously. DFA can provide a quick result, and herpes culture can provide a more sensitive result (this may take 5-7 days before results are available).

No evidence that antivirals pose risk during pregnancy

Treatment with antivirals (acyclovir, famciclovir, or valacyclovir) may help to reduce the length of the outbreak. Oral antivirals are usually sufficient for uncomplicated HSV; IV antivirals may be needed in complicated cases. The current recommendation for acyclovir (the most commonly prescribed drug for HSV infection) is 400 mg 3 times daily or 200 mg 5 times daily for 7 to 10 days in a primary outbreak.3

Antiviral therapy is most effective if begun within 72 hours of symptom onset in primary herpes genitalis.4 Analgesics can help with pain control and sitz baths are helpful for women with severe dysuria.

Maternal–fetal transmission of HSV is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in children.5 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend that cesarean delivery be offered as soon as possible to women who have active HSV lesions or, in those with a history of genital herpes, symptoms of vulvar pain or burning at the time of delivery.3

There is no evidence that the use of antiviral agents in women who are pregnant and have a history of genital herpes prevents perinatal transmission of HSV to neonates.6 However, antenatal antiviral prophylaxis has been shown to reduce viral shedding, recurrences at delivery, and the need for cesarean delivery.7

Our patient was treated with oral acyclovir 400 mg 3 times a day for 10 days. One day after seeking care, she had less pain, swelling, and tenderness and was discharged. (Based on the severity of the outbreak and lack of sanitary living conditions, hospitalization was the safest and most reliable option.) The patient was counseled on the ramifications of HSV infection in pregnancy, including the fact that she might need a cesarean section. She was told that she must get prenatal care and that she needed to tell her primary care physician about her HSV infection. She was also warned about the risk of disease transmission to sexual partners and the importance of using barrier contraception to minimize the risk of future transmission.

CORRESPONDENCE

Luke Wallis, BS, 6410 Rambling Trail Drive, San Antonio, TX 78240; [email protected].

1. World Health Organization. Herpes simplex virus. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs400/en/. Accessed February 8, 2016.

2. Ramaswamy M, McDonald C, Smith M, et al. Diagnosis of genital herpes by real time PCR in routine clinical practice. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:406-410.

3. Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-110.

4. Cernik C, Gallina K, Brodell RT. The treatment of herpes simplex infections: an evidence-based review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1137-1144.

5. Flagg EW, Weinstock H. Incidence of neonatal herpes simplex virus infections in the United States, 2006. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1-e8.

6. Wenner C, Nashelsky J. Antiviral agents for pregnant women with genital herpes. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:1807-1808.

7. Hollier LM, Wendel GD. Third trimester antiviral prophylaxis for preventing maternal genital herpes simplex virus (HSV) recurrences and neonatal infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;CD004946.

A 30-year-old pregnant woman presented to a rural Panamanian hospital with new onset genital pain, vaginal itching, and dysuria that she’d had for 48 hours. The patient was in the first trimester of her pregnancy and indicated that she’d had recent unprotected sex with a new partner who wasn’t the father of the developing fetus. The patient had never experienced symptoms like these before and denied ever having a sexually transmitted infection (STI). On physical exam, the physician noted numerous pustules covering tender, swollen labia (FIGURE). A small amount of white discharge was noted at the introitus.

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes simplex virus

The physician on-call diagnosed candida vaginitis along with a bacterial skin infection, and admitted the patient to the hospital for intravenous (IV) antibiotics. Fortunately, we were there on a medical mission and were consulted on the case.

We diagnosed a primary herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection in this patient, based on the classic presentation of grouped pustules and vesicles on erythematous and swollen labia, and the patient’s complaint of dysuria.

Herpes cultures weren’t available in the hospital, but the clinical picture was unmistakable for HSV infection. Since multiple STIs may occur simultaneously, we ordered a serum rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test for syphilis, and tested her urine for gonorrhea and chlamydia. The tests were negative.

Differential Dx includes other STIs and a fixed drug eruption

Herpes is a common STI and most people don’t have symptoms. In 2012, an estimated 417 million people worldwide were living with genital herpes caused by HSV-2.1

The differential diagnosis for HSV infection includes primary syphilis, chancroid, folliculitis, and fixed drug eruptions.

Primary syphilis (Treponema pallidum) commonly presents with a painless, ulcerated, clean-based ulcer. While the chancre of primary syphilis can sometimes be painful, this patient did not have ulcers at the time of her presentation. Her pustules would likely ulcerate over time, but would not resemble the chancre of syphilis.

Chancroid (Haemophilus ducreyi) is a less common STI than syphilis and HSV infection. It presents with deep, sharply defined, purulent ulcers that are often associated with painful adenopathy. The ulcers can appear grey or yellowish in color.

Folliculitis presents with pustules surrounding hair follicles. Some of the pustules were surrounding hair follicles in this patient’s case, but others were independent of the hair. The patient’s marked swelling and tenderness along with dysuria also did not fit the characteristics of folliculitis.

Fixed drug eruptions can occur in the genital region, but the patient had neither bullous nor ulcerated eruptions (as one would expect with this condition). Fixed drug eruptions are usually hyperpigmented and require a history of taking medication, such as an antibiotic or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Questions that help narrow the differential. Zeroing in on the cause of a patient’s genital lesions requires that you ask whether the lesions are painful, if the patient has dysuria, if there are any constitutional symptoms, and if this has happened before. Other distinguishing factors include enlarged lymph nodes and the presence of multiple (vs single) lesions.

Viral cell cultures are the preferred lab test

Common laboratory tests to make the diagnosis include viral culture, direct fluorescence antibody (DFA), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and type-specific serologic tests.