User login

Growths on face and scalp

The FP diagnosed molluscum contagiosum and recognized that some of the larger lesions on the scalp were related to the patient’s altered immune status. Molluscum contagiosum is a viral skin infection that produces pearly papules that often have central umbilication. This skin infection is most commonly seen in children, but can also be transmitted sexually among adults. The number of cases in adults increased in the 1980s in the United States, probably as a result of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the number of molluscum contagiosum cases in HIV/AIDS patients has decreased substantially. However, the prevalence of molluscum contagiosum in patients who are HIV-positive may still be as high as 5% to 18%.

The FP encouraged the patient to take her antiretroviral medication as prescribed and suggested that she return to her HIV specialist to see if her therapeutic regimen required any adjustments. He also offered her cryotherapy, with a follow-up appointment one month later. The patient agreed to the cryotherapy, which was performed with a cryogun using a bent tip spray. The patient’s eye was protected using a tongue depressor, while her eyelid was sprayed with liquid nitrogen.

At the follow-up visit, the molluscum lesions had improved and a second round of cryotherapy was performed. Although it was not offered to this patient, topical imiquimod is another treatment option for molluscum contagiosum. This treatment has not, however, been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Molluscum contagiosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:743-748.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed molluscum contagiosum and recognized that some of the larger lesions on the scalp were related to the patient’s altered immune status. Molluscum contagiosum is a viral skin infection that produces pearly papules that often have central umbilication. This skin infection is most commonly seen in children, but can also be transmitted sexually among adults. The number of cases in adults increased in the 1980s in the United States, probably as a result of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the number of molluscum contagiosum cases in HIV/AIDS patients has decreased substantially. However, the prevalence of molluscum contagiosum in patients who are HIV-positive may still be as high as 5% to 18%.

The FP encouraged the patient to take her antiretroviral medication as prescribed and suggested that she return to her HIV specialist to see if her therapeutic regimen required any adjustments. He also offered her cryotherapy, with a follow-up appointment one month later. The patient agreed to the cryotherapy, which was performed with a cryogun using a bent tip spray. The patient’s eye was protected using a tongue depressor, while her eyelid was sprayed with liquid nitrogen.

At the follow-up visit, the molluscum lesions had improved and a second round of cryotherapy was performed. Although it was not offered to this patient, topical imiquimod is another treatment option for molluscum contagiosum. This treatment has not, however, been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Molluscum contagiosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:743-748.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed molluscum contagiosum and recognized that some of the larger lesions on the scalp were related to the patient’s altered immune status. Molluscum contagiosum is a viral skin infection that produces pearly papules that often have central umbilication. This skin infection is most commonly seen in children, but can also be transmitted sexually among adults. The number of cases in adults increased in the 1980s in the United States, probably as a result of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the number of molluscum contagiosum cases in HIV/AIDS patients has decreased substantially. However, the prevalence of molluscum contagiosum in patients who are HIV-positive may still be as high as 5% to 18%.

The FP encouraged the patient to take her antiretroviral medication as prescribed and suggested that she return to her HIV specialist to see if her therapeutic regimen required any adjustments. He also offered her cryotherapy, with a follow-up appointment one month later. The patient agreed to the cryotherapy, which was performed with a cryogun using a bent tip spray. The patient’s eye was protected using a tongue depressor, while her eyelid was sprayed with liquid nitrogen.

At the follow-up visit, the molluscum lesions had improved and a second round of cryotherapy was performed. Although it was not offered to this patient, topical imiquimod is another treatment option for molluscum contagiosum. This treatment has not, however, been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Molluscum contagiosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:743-748.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Large plaques on a baby boy

A 25-year-old G2P1 mother gave birth to a boy at 40 and 6/7 weeks by vaginal delivery. Labor was induced because of oligohydramnios complicated by chorioamnionitis. The mother was treated with vancomycin and gentamicin. Prenatal lab work and delivery were otherwise unremarkable.

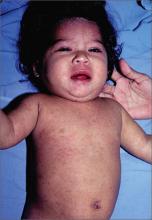

The delivering physician (CG) noted that the neonate had numerous brown, red, and black plaques distributed over his abdomen, lower back, groin, and thighs (FIGURE). Some plaques were hypertrichotic and other areas, apart from the plaques, were thinly desquamated. Apgar scores were 8 and 9 and the remainder of the exam, including the neurologic exam, was normal. The Dermatology Service (JK) was consulted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Giant congenital nevus

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are pigmented lesions that are present at birth and created by the abnormal migration of neural crest cells during embryogenesis.1 Nevi are categorized by size as small (<1.5 cm), medium (1.5-20 cm), large (>20 cm), and giant (>40 cm).2 Congenital nevi tend to start out flat, with uniform pigmentation, but can become more variegated in texture and color as normal growth and development continue. Giant congenital nevi are likely to thicken, darken, and enlarge as the patient grows. Some nevi may develop very coarse or dark hair.

CMN can cover any part of the body and occur independent of skin color and other ethnic factors.3 Giant congenital nevi are rare, with an incidence of approximately one in 50,000 live births and with males and females equally affected.3,4 The condition is diagnosed at birth, based on the appearance of the lesions.

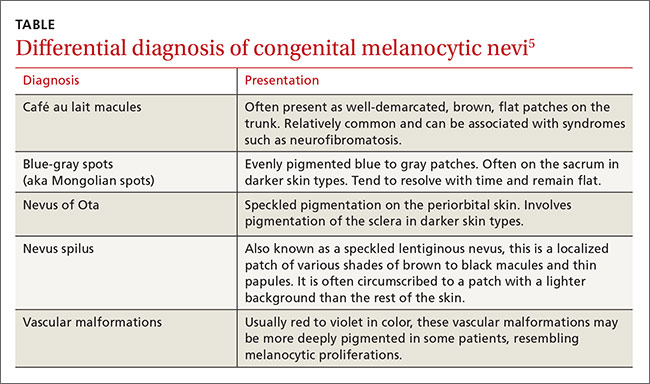

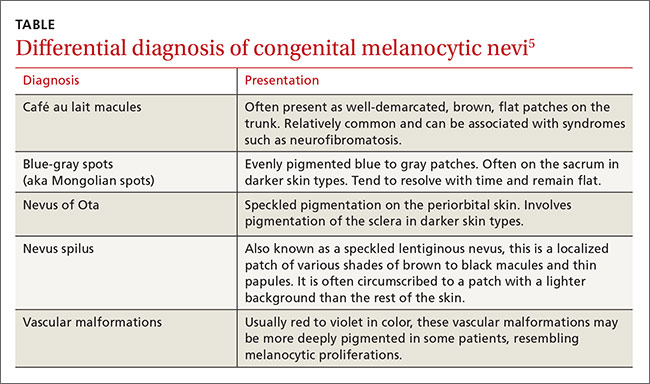

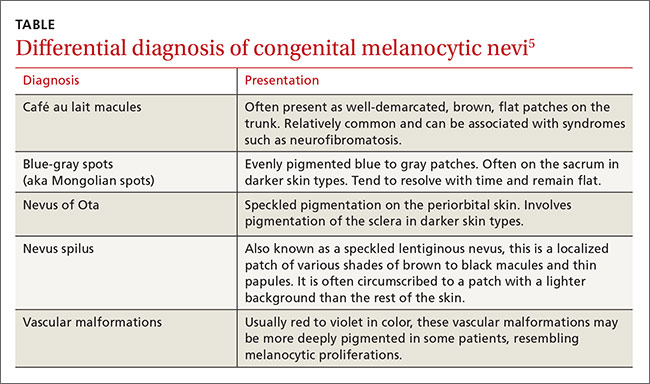

The differential diagnosis for CMN includes café au lait macules, blue-gray spots (aka Mongolian spots), nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations (TABLE).5 CMN may present in almost any location and may be brown, black, pink, or purple in color. Café au lait macules, blue-gray spots, nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations have individual location and color characteristics that set them apart clinically.

Monitor patients for melanoma, CNS complications

Patients with CMN are at increased risk of neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) and cutaneous melanoma.

Neurocutaneous melanosis, a complication of giant congenital nevi, is a melanocyte proliferation in the central nervous system (CNS). Between 6% and 11% of patients with giant congenital nevi develop symptomatic NCM in childhood. Thus, any CNS symptoms should be fully evaluated.4,6 NCM can result in seizures, cranial nerve palsy, hydrocephalus, and leptomeningeal melanoma.

Besides giant congenital nevi, risk factors for NCM include male sex, large numbers of satellite nevi, and the presence of nevi over the posterior midline or head and neck.7 The prognosis is poor for patients who develop neurologic symptoms. NCM is associated with other malignancies, including rhadomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors.4

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful to exclude NCM. Ideally, an MRI should be ordered before 4 months of age, at which time myelination begins to make the identification of melanin deposits in the CNS more challenging.7 Not all patients with imaging findings that are consistent with NCM will develop symptoms.8

Melanoma. By age 10, up to 8% of patients with giant congenital nevi will develop melanoma within the nevi; most of these cases occur during the first 2 years of life.7,9 Patients with NCM are at even greater risk: their rate of malignant melanoma is between 40% and 60%.6 As a result, patients should be monitored closely for any signs of the disease. Total body photography, serial clinical photos, and patient self-exam are helpful to detect changes and de novo lesions. New lesions or ulcerations superimposed on existing nevi may indicate malignancy.7 Sun protection is critical to reduce the risk of melanogenesis.

Should patients pursue surgery? It’s debatable

Options for patients with large and giant CMN include early curettage (prior to 2 weeks of life), local excision (often with tissue expansion), dermabrasion, and laser therapy.2 There is considerable debate about surgery. Advocates of surgery cite psychosocial relief as a major treatment benefit and speculate about prevention of melanoma. Opponents worry that excessive surgical intervention may cause melanogenesis in a scar or deep in an area of treatment. And, while smaller congenital nevi are easier to surgically remove, they have a low associated risk of developing melanoma and are typically monitored clinically.

Children with congenital nevi will need support

Several nonprofit organizations offer resources for children with congenital nevi and their families. Nevus Outreach (www.nevus.org) is an organization devoted to improving awareness and providing support for people with CMN and NCM. The group maintains a registry of patients with large nevi in an effort to help researchers improve treatment and identify a cure.

For children with congenital nevi and other skin conditions, the American Academy of Dermatology offers its “Camp Discovery” at locations across the country (https://www.aad.org/public/kids/camp-discovery). Camp Discovery provides full scholarships and includes transportation to each of the individual camps for attendees.

Our patient underwent an MRI on his fifth day of life. The results were normal and he hadn’t developed any neurologic symptoms at 4 months of age. The child sees his family physician for routine well-child visits and a dermatologist annually. The dermatologist is carefully monitoring the nevi, which continue to grow.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Suite 340, Augusta, ME 04330; [email protected].

1. Sarnat HB, Flores-Sarnat L. Embryology of the neural crest: its inductive role in the neurocutaneous syndromes. J Child Neurol. 2005:20:637-643.

2. Gosain AK, Santoro TD, Larson DL, et al. Giant congenital nevi: a 20-year experience and an algorithm for their management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:622-636.

3. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Giant congenital melanocytic nevus. National Organization for Rare Disorders Web site. Available at: http://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/giant-congenital-melanocytic-nevus. Accessed April 29, 2016.

4. Vourc’h-Jourdain M, Martin L, Barbarot S; aRED. Large congenital melanocytic nevi: therapeutic management and melanoma risk: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:493-498.e1-e14.

5. Jackson SM, Nesbitt LT. Differential Diagnosis for the Dermatologist. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2012.

6. Jain P, Kannan L, Kumar A, et al. Symptomatic neurocutaneous melanosis in a child. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:516.

7. Kinsler VA, Chong WK, Aylett SE, et al. Complications of congenital melanocytic naevi in children: analysis of 16 years’ experience and clinical practice. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:907-914.

8. Agero AL, B envenuto-Andrade C, Dusza SW, et al. Asymptomatic neurocutaneous melanocytosis in patients with large congenital melanocytic nevi: a study of cases from an Internet-based registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:959-965.

9. Zayour M, Lazova R. Congenital melanocytic nevi. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:267-280.

A 25-year-old G2P1 mother gave birth to a boy at 40 and 6/7 weeks by vaginal delivery. Labor was induced because of oligohydramnios complicated by chorioamnionitis. The mother was treated with vancomycin and gentamicin. Prenatal lab work and delivery were otherwise unremarkable.

The delivering physician (CG) noted that the neonate had numerous brown, red, and black plaques distributed over his abdomen, lower back, groin, and thighs (FIGURE). Some plaques were hypertrichotic and other areas, apart from the plaques, were thinly desquamated. Apgar scores were 8 and 9 and the remainder of the exam, including the neurologic exam, was normal. The Dermatology Service (JK) was consulted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Giant congenital nevus

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are pigmented lesions that are present at birth and created by the abnormal migration of neural crest cells during embryogenesis.1 Nevi are categorized by size as small (<1.5 cm), medium (1.5-20 cm), large (>20 cm), and giant (>40 cm).2 Congenital nevi tend to start out flat, with uniform pigmentation, but can become more variegated in texture and color as normal growth and development continue. Giant congenital nevi are likely to thicken, darken, and enlarge as the patient grows. Some nevi may develop very coarse or dark hair.

CMN can cover any part of the body and occur independent of skin color and other ethnic factors.3 Giant congenital nevi are rare, with an incidence of approximately one in 50,000 live births and with males and females equally affected.3,4 The condition is diagnosed at birth, based on the appearance of the lesions.

The differential diagnosis for CMN includes café au lait macules, blue-gray spots (aka Mongolian spots), nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations (TABLE).5 CMN may present in almost any location and may be brown, black, pink, or purple in color. Café au lait macules, blue-gray spots, nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations have individual location and color characteristics that set them apart clinically.

Monitor patients for melanoma, CNS complications

Patients with CMN are at increased risk of neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) and cutaneous melanoma.

Neurocutaneous melanosis, a complication of giant congenital nevi, is a melanocyte proliferation in the central nervous system (CNS). Between 6% and 11% of patients with giant congenital nevi develop symptomatic NCM in childhood. Thus, any CNS symptoms should be fully evaluated.4,6 NCM can result in seizures, cranial nerve palsy, hydrocephalus, and leptomeningeal melanoma.

Besides giant congenital nevi, risk factors for NCM include male sex, large numbers of satellite nevi, and the presence of nevi over the posterior midline or head and neck.7 The prognosis is poor for patients who develop neurologic symptoms. NCM is associated with other malignancies, including rhadomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors.4

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful to exclude NCM. Ideally, an MRI should be ordered before 4 months of age, at which time myelination begins to make the identification of melanin deposits in the CNS more challenging.7 Not all patients with imaging findings that are consistent with NCM will develop symptoms.8

Melanoma. By age 10, up to 8% of patients with giant congenital nevi will develop melanoma within the nevi; most of these cases occur during the first 2 years of life.7,9 Patients with NCM are at even greater risk: their rate of malignant melanoma is between 40% and 60%.6 As a result, patients should be monitored closely for any signs of the disease. Total body photography, serial clinical photos, and patient self-exam are helpful to detect changes and de novo lesions. New lesions or ulcerations superimposed on existing nevi may indicate malignancy.7 Sun protection is critical to reduce the risk of melanogenesis.

Should patients pursue surgery? It’s debatable

Options for patients with large and giant CMN include early curettage (prior to 2 weeks of life), local excision (often with tissue expansion), dermabrasion, and laser therapy.2 There is considerable debate about surgery. Advocates of surgery cite psychosocial relief as a major treatment benefit and speculate about prevention of melanoma. Opponents worry that excessive surgical intervention may cause melanogenesis in a scar or deep in an area of treatment. And, while smaller congenital nevi are easier to surgically remove, they have a low associated risk of developing melanoma and are typically monitored clinically.

Children with congenital nevi will need support

Several nonprofit organizations offer resources for children with congenital nevi and their families. Nevus Outreach (www.nevus.org) is an organization devoted to improving awareness and providing support for people with CMN and NCM. The group maintains a registry of patients with large nevi in an effort to help researchers improve treatment and identify a cure.

For children with congenital nevi and other skin conditions, the American Academy of Dermatology offers its “Camp Discovery” at locations across the country (https://www.aad.org/public/kids/camp-discovery). Camp Discovery provides full scholarships and includes transportation to each of the individual camps for attendees.

Our patient underwent an MRI on his fifth day of life. The results were normal and he hadn’t developed any neurologic symptoms at 4 months of age. The child sees his family physician for routine well-child visits and a dermatologist annually. The dermatologist is carefully monitoring the nevi, which continue to grow.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Suite 340, Augusta, ME 04330; [email protected].

A 25-year-old G2P1 mother gave birth to a boy at 40 and 6/7 weeks by vaginal delivery. Labor was induced because of oligohydramnios complicated by chorioamnionitis. The mother was treated with vancomycin and gentamicin. Prenatal lab work and delivery were otherwise unremarkable.

The delivering physician (CG) noted that the neonate had numerous brown, red, and black plaques distributed over his abdomen, lower back, groin, and thighs (FIGURE). Some plaques were hypertrichotic and other areas, apart from the plaques, were thinly desquamated. Apgar scores were 8 and 9 and the remainder of the exam, including the neurologic exam, was normal. The Dermatology Service (JK) was consulted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Giant congenital nevus

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are pigmented lesions that are present at birth and created by the abnormal migration of neural crest cells during embryogenesis.1 Nevi are categorized by size as small (<1.5 cm), medium (1.5-20 cm), large (>20 cm), and giant (>40 cm).2 Congenital nevi tend to start out flat, with uniform pigmentation, but can become more variegated in texture and color as normal growth and development continue. Giant congenital nevi are likely to thicken, darken, and enlarge as the patient grows. Some nevi may develop very coarse or dark hair.

CMN can cover any part of the body and occur independent of skin color and other ethnic factors.3 Giant congenital nevi are rare, with an incidence of approximately one in 50,000 live births and with males and females equally affected.3,4 The condition is diagnosed at birth, based on the appearance of the lesions.

The differential diagnosis for CMN includes café au lait macules, blue-gray spots (aka Mongolian spots), nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations (TABLE).5 CMN may present in almost any location and may be brown, black, pink, or purple in color. Café au lait macules, blue-gray spots, nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations have individual location and color characteristics that set them apart clinically.

Monitor patients for melanoma, CNS complications

Patients with CMN are at increased risk of neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) and cutaneous melanoma.

Neurocutaneous melanosis, a complication of giant congenital nevi, is a melanocyte proliferation in the central nervous system (CNS). Between 6% and 11% of patients with giant congenital nevi develop symptomatic NCM in childhood. Thus, any CNS symptoms should be fully evaluated.4,6 NCM can result in seizures, cranial nerve palsy, hydrocephalus, and leptomeningeal melanoma.

Besides giant congenital nevi, risk factors for NCM include male sex, large numbers of satellite nevi, and the presence of nevi over the posterior midline or head and neck.7 The prognosis is poor for patients who develop neurologic symptoms. NCM is associated with other malignancies, including rhadomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors.4

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful to exclude NCM. Ideally, an MRI should be ordered before 4 months of age, at which time myelination begins to make the identification of melanin deposits in the CNS more challenging.7 Not all patients with imaging findings that are consistent with NCM will develop symptoms.8

Melanoma. By age 10, up to 8% of patients with giant congenital nevi will develop melanoma within the nevi; most of these cases occur during the first 2 years of life.7,9 Patients with NCM are at even greater risk: their rate of malignant melanoma is between 40% and 60%.6 As a result, patients should be monitored closely for any signs of the disease. Total body photography, serial clinical photos, and patient self-exam are helpful to detect changes and de novo lesions. New lesions or ulcerations superimposed on existing nevi may indicate malignancy.7 Sun protection is critical to reduce the risk of melanogenesis.

Should patients pursue surgery? It’s debatable

Options for patients with large and giant CMN include early curettage (prior to 2 weeks of life), local excision (often with tissue expansion), dermabrasion, and laser therapy.2 There is considerable debate about surgery. Advocates of surgery cite psychosocial relief as a major treatment benefit and speculate about prevention of melanoma. Opponents worry that excessive surgical intervention may cause melanogenesis in a scar or deep in an area of treatment. And, while smaller congenital nevi are easier to surgically remove, they have a low associated risk of developing melanoma and are typically monitored clinically.

Children with congenital nevi will need support

Several nonprofit organizations offer resources for children with congenital nevi and their families. Nevus Outreach (www.nevus.org) is an organization devoted to improving awareness and providing support for people with CMN and NCM. The group maintains a registry of patients with large nevi in an effort to help researchers improve treatment and identify a cure.

For children with congenital nevi and other skin conditions, the American Academy of Dermatology offers its “Camp Discovery” at locations across the country (https://www.aad.org/public/kids/camp-discovery). Camp Discovery provides full scholarships and includes transportation to each of the individual camps for attendees.

Our patient underwent an MRI on his fifth day of life. The results were normal and he hadn’t developed any neurologic symptoms at 4 months of age. The child sees his family physician for routine well-child visits and a dermatologist annually. The dermatologist is carefully monitoring the nevi, which continue to grow.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Suite 340, Augusta, ME 04330; [email protected].

1. Sarnat HB, Flores-Sarnat L. Embryology of the neural crest: its inductive role in the neurocutaneous syndromes. J Child Neurol. 2005:20:637-643.

2. Gosain AK, Santoro TD, Larson DL, et al. Giant congenital nevi: a 20-year experience and an algorithm for their management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:622-636.

3. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Giant congenital melanocytic nevus. National Organization for Rare Disorders Web site. Available at: http://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/giant-congenital-melanocytic-nevus. Accessed April 29, 2016.

4. Vourc’h-Jourdain M, Martin L, Barbarot S; aRED. Large congenital melanocytic nevi: therapeutic management and melanoma risk: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:493-498.e1-e14.

5. Jackson SM, Nesbitt LT. Differential Diagnosis for the Dermatologist. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2012.

6. Jain P, Kannan L, Kumar A, et al. Symptomatic neurocutaneous melanosis in a child. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:516.

7. Kinsler VA, Chong WK, Aylett SE, et al. Complications of congenital melanocytic naevi in children: analysis of 16 years’ experience and clinical practice. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:907-914.

8. Agero AL, B envenuto-Andrade C, Dusza SW, et al. Asymptomatic neurocutaneous melanocytosis in patients with large congenital melanocytic nevi: a study of cases from an Internet-based registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:959-965.

9. Zayour M, Lazova R. Congenital melanocytic nevi. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:267-280.

1. Sarnat HB, Flores-Sarnat L. Embryology of the neural crest: its inductive role in the neurocutaneous syndromes. J Child Neurol. 2005:20:637-643.

2. Gosain AK, Santoro TD, Larson DL, et al. Giant congenital nevi: a 20-year experience and an algorithm for their management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:622-636.

3. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Giant congenital melanocytic nevus. National Organization for Rare Disorders Web site. Available at: http://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/giant-congenital-melanocytic-nevus. Accessed April 29, 2016.

4. Vourc’h-Jourdain M, Martin L, Barbarot S; aRED. Large congenital melanocytic nevi: therapeutic management and melanoma risk: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:493-498.e1-e14.

5. Jackson SM, Nesbitt LT. Differential Diagnosis for the Dermatologist. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2012.

6. Jain P, Kannan L, Kumar A, et al. Symptomatic neurocutaneous melanosis in a child. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:516.

7. Kinsler VA, Chong WK, Aylett SE, et al. Complications of congenital melanocytic naevi in children: analysis of 16 years’ experience and clinical practice. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:907-914.

8. Agero AL, B envenuto-Andrade C, Dusza SW, et al. Asymptomatic neurocutaneous melanocytosis in patients with large congenital melanocytic nevi: a study of cases from an Internet-based registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:959-965.

9. Zayour M, Lazova R. Congenital melanocytic nevi. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:267-280.

Painful vesicles on penis

The FP diagnosed this patient with genital herpes. The patient’s herpes culture came back positive and his rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) tests were negative.

Genital herpes presents with multiple transient, painful vesicles that appear on the penis, vulva, buttocks, perineum, vagina, or cervix. The vesicles break down and become ulcers that develop crusts while healing. Recurrences typically occur 2 to 3 times a year. The duration is shorter and less painful than in primary infections. The lesions often heal completely by 8 to 10 days.

The gold standard of diagnosis is viral isolation by tissue culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The culture sensitivity rate is only 70% to 80% and depends upon the stage at which the specimen is collected. The sensitivity is highest in the vesicular stage and declines with ulceration and crusting. The tissue culture assay can be positive within 48 hours but may take longer.

PCR is extremely sensitive (96%) and specific (99%). PCR testing is generally used for cerebrospinal fluid testing in suspected herpes simplex virus encephalitis or meningitis. The Tzanck test and antigen detection tests have lower sensitivity rates than viral culture and should not be relied on for diagnosis.

Antiviral therapy is recommended for an initial genital herpes outbreak. Although systemic antiviral drugs can partially control the signs and symptoms of herpes episodes, they do not eradicate the latent virus. Acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir are equally effective for episodic treatment of genital herpes, but famciclovir appears somewhat less effective for suppression of viral shedding. Effective episodic treatment of herpes requires initiation of therapy during the prodrome period or within one day of lesion onset. Providing the patient with instructions to initiate treatment immediately when symptoms begin improves efficacy for future outbreaks. Patients with frequent recurrences can choose to take daily antiviral medication for prevention of new outbreaks.

It was too late to initiate antiviral therapy for this patient, so treatment was confined to oral over-the-counter analgesics and topical petrolatum. The FP counseled the patient about the nature of the disease, its transmissibility, and the likelihood of recurrence.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Carter K. Herpes simplex. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:735-742.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed this patient with genital herpes. The patient’s herpes culture came back positive and his rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) tests were negative.

Genital herpes presents with multiple transient, painful vesicles that appear on the penis, vulva, buttocks, perineum, vagina, or cervix. The vesicles break down and become ulcers that develop crusts while healing. Recurrences typically occur 2 to 3 times a year. The duration is shorter and less painful than in primary infections. The lesions often heal completely by 8 to 10 days.

The gold standard of diagnosis is viral isolation by tissue culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The culture sensitivity rate is only 70% to 80% and depends upon the stage at which the specimen is collected. The sensitivity is highest in the vesicular stage and declines with ulceration and crusting. The tissue culture assay can be positive within 48 hours but may take longer.

PCR is extremely sensitive (96%) and specific (99%). PCR testing is generally used for cerebrospinal fluid testing in suspected herpes simplex virus encephalitis or meningitis. The Tzanck test and antigen detection tests have lower sensitivity rates than viral culture and should not be relied on for diagnosis.

Antiviral therapy is recommended for an initial genital herpes outbreak. Although systemic antiviral drugs can partially control the signs and symptoms of herpes episodes, they do not eradicate the latent virus. Acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir are equally effective for episodic treatment of genital herpes, but famciclovir appears somewhat less effective for suppression of viral shedding. Effective episodic treatment of herpes requires initiation of therapy during the prodrome period or within one day of lesion onset. Providing the patient with instructions to initiate treatment immediately when symptoms begin improves efficacy for future outbreaks. Patients with frequent recurrences can choose to take daily antiviral medication for prevention of new outbreaks.

It was too late to initiate antiviral therapy for this patient, so treatment was confined to oral over-the-counter analgesics and topical petrolatum. The FP counseled the patient about the nature of the disease, its transmissibility, and the likelihood of recurrence.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Carter K. Herpes simplex. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:735-742.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed this patient with genital herpes. The patient’s herpes culture came back positive and his rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) tests were negative.

Genital herpes presents with multiple transient, painful vesicles that appear on the penis, vulva, buttocks, perineum, vagina, or cervix. The vesicles break down and become ulcers that develop crusts while healing. Recurrences typically occur 2 to 3 times a year. The duration is shorter and less painful than in primary infections. The lesions often heal completely by 8 to 10 days.

The gold standard of diagnosis is viral isolation by tissue culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The culture sensitivity rate is only 70% to 80% and depends upon the stage at which the specimen is collected. The sensitivity is highest in the vesicular stage and declines with ulceration and crusting. The tissue culture assay can be positive within 48 hours but may take longer.

PCR is extremely sensitive (96%) and specific (99%). PCR testing is generally used for cerebrospinal fluid testing in suspected herpes simplex virus encephalitis or meningitis. The Tzanck test and antigen detection tests have lower sensitivity rates than viral culture and should not be relied on for diagnosis.

Antiviral therapy is recommended for an initial genital herpes outbreak. Although systemic antiviral drugs can partially control the signs and symptoms of herpes episodes, they do not eradicate the latent virus. Acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir are equally effective for episodic treatment of genital herpes, but famciclovir appears somewhat less effective for suppression of viral shedding. Effective episodic treatment of herpes requires initiation of therapy during the prodrome period or within one day of lesion onset. Providing the patient with instructions to initiate treatment immediately when symptoms begin improves efficacy for future outbreaks. Patients with frequent recurrences can choose to take daily antiviral medication for prevention of new outbreaks.

It was too late to initiate antiviral therapy for this patient, so treatment was confined to oral over-the-counter analgesics and topical petrolatum. The FP counseled the patient about the nature of the disease, its transmissibility, and the likelihood of recurrence.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Carter K. Herpes simplex. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:735-742.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Child with fever, cough, and rash

The FP suspected that this patient had measles, but since it has a low prevalence in the United States, he confirmed the diagnosis with a specific serum immunoglobulin M antibody test. Measles is a highly communicable, acute, viral illness that is still one of the most serious infectious diseases in human history. Until the introduction of the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, it was responsible for millions of deaths worldwide annually. Eradication of measles is possible, but the ease of transmission and the low percentage of nonimmunized population that is required for disease survival have made eradication extremely difficult.

The classic measles rash is maculopapular and blanches under pressure. The rash begins on the face and spreads centrifugally to involve the neck, trunk, and, finally, the extremities. This cranial-to-caudal rash progression is characteristic of measles. The cough may persist for up to 2 weeks. Fever persisting beyond the third day of rash suggests a measles-associated complication.

Postinfectious encephalomyelitis can also occur. Postinfectious encephalomyelitis is a demyelinating disease that presents during the recovery phase, and is thought to be caused by a postinfectious autoimmune response.

The treatment of measles is mostly supportive and patients will need to stay away from other individuals—particularly unimmunized children and adults, pregnant women, and immunocompromised people—until at least 4 days after rash onset. Suspected cases of measles should be reported immediately to the local or state department of health.

In this case, the child showed no evidence of pneumonia, neurological symptoms, or dehydration, so hospitalization was not needed. Fortunately, the mother and father had both been vaccinated as children and this was their only child. Antipyretics and fluids were recommended. The parents were told to avoid giving the child aspirin to prevent Reye’s syndrome.

The FP maintained contact with the family over the phone and the symptoms began resolving within a few days. The FP also reported the case to the local health department.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Eric Kraus. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Baudoin L. Measles. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY:McGraw-Hill;2013:723-727.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this patient had measles, but since it has a low prevalence in the United States, he confirmed the diagnosis with a specific serum immunoglobulin M antibody test. Measles is a highly communicable, acute, viral illness that is still one of the most serious infectious diseases in human history. Until the introduction of the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, it was responsible for millions of deaths worldwide annually. Eradication of measles is possible, but the ease of transmission and the low percentage of nonimmunized population that is required for disease survival have made eradication extremely difficult.

The classic measles rash is maculopapular and blanches under pressure. The rash begins on the face and spreads centrifugally to involve the neck, trunk, and, finally, the extremities. This cranial-to-caudal rash progression is characteristic of measles. The cough may persist for up to 2 weeks. Fever persisting beyond the third day of rash suggests a measles-associated complication.

Postinfectious encephalomyelitis can also occur. Postinfectious encephalomyelitis is a demyelinating disease that presents during the recovery phase, and is thought to be caused by a postinfectious autoimmune response.

The treatment of measles is mostly supportive and patients will need to stay away from other individuals—particularly unimmunized children and adults, pregnant women, and immunocompromised people—until at least 4 days after rash onset. Suspected cases of measles should be reported immediately to the local or state department of health.

In this case, the child showed no evidence of pneumonia, neurological symptoms, or dehydration, so hospitalization was not needed. Fortunately, the mother and father had both been vaccinated as children and this was their only child. Antipyretics and fluids were recommended. The parents were told to avoid giving the child aspirin to prevent Reye’s syndrome.

The FP maintained contact with the family over the phone and the symptoms began resolving within a few days. The FP also reported the case to the local health department.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Eric Kraus. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Baudoin L. Measles. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY:McGraw-Hill;2013:723-727.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this patient had measles, but since it has a low prevalence in the United States, he confirmed the diagnosis with a specific serum immunoglobulin M antibody test. Measles is a highly communicable, acute, viral illness that is still one of the most serious infectious diseases in human history. Until the introduction of the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, it was responsible for millions of deaths worldwide annually. Eradication of measles is possible, but the ease of transmission and the low percentage of nonimmunized population that is required for disease survival have made eradication extremely difficult.

The classic measles rash is maculopapular and blanches under pressure. The rash begins on the face and spreads centrifugally to involve the neck, trunk, and, finally, the extremities. This cranial-to-caudal rash progression is characteristic of measles. The cough may persist for up to 2 weeks. Fever persisting beyond the third day of rash suggests a measles-associated complication.

Postinfectious encephalomyelitis can also occur. Postinfectious encephalomyelitis is a demyelinating disease that presents during the recovery phase, and is thought to be caused by a postinfectious autoimmune response.

The treatment of measles is mostly supportive and patients will need to stay away from other individuals—particularly unimmunized children and adults, pregnant women, and immunocompromised people—until at least 4 days after rash onset. Suspected cases of measles should be reported immediately to the local or state department of health.

In this case, the child showed no evidence of pneumonia, neurological symptoms, or dehydration, so hospitalization was not needed. Fortunately, the mother and father had both been vaccinated as children and this was their only child. Antipyretics and fluids were recommended. The parents were told to avoid giving the child aspirin to prevent Reye’s syndrome.

The FP maintained contact with the family over the phone and the symptoms began resolving within a few days. The FP also reported the case to the local health department.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Eric Kraus. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Baudoin L. Measles. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY:McGraw-Hill;2013:723-727.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Ulcers on upper lip

The FP diagnosed recurrent orolabial herpes. Orolabial herpes typically takes the form of painful vesicles and ulcerative erosions on the tongue, palate, gingiva, buccal mucosa, and lips. Treatment for primary orolabial herpes includes oral acyclovir (200 mg 5 times daily for 5 days), which accelerates healing by one day and can reduce the mean duration of pain by 36%. Alternatively, valacyclovir can be given 2000 mg orally every 12 hours for one day and, like acyclovir, should be started as soon as possible after the onset of symptoms.

Docosanol cream is available without a prescription for oral herpes. One randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 743 patients with herpes labialis showed a faster healing time in patients treated with docosanol 10% cream when compared with placebo cream (4.1 vs 4.8 days), as well as reduced duration of pain symptoms (2.2 vs 2.7 days).1 More than 90% of patients in both groups healed completely within 10 days.1 Treatment with docosanol cream, when applied 5 times per day and within 12 hours of episode onset until symptoms are relieved, is safe and somewhat effective.

Suppression for patients with frequent recurrences may be provided with valacyclovir 500 mg daily or acyclovir 400 mg twice daily.

Suppression was not indicated for this patient since she had infrequent episodes. She was told that the best prevention would be to use a high-potency sunscreen on her lips and face when out in the sun and to use protective clothing such as a broad brim hat. To prevent skin cancers and recurrent oral labial herpes, she was told to avoid the midday sun whenever possible.

The FP also explained that it was too late now to start oral antiviral treatment, but that she might want to use topical petrolatum for symptom relief. He also offered her a prescription for an oral antiviral medicine that she could fill at the start of symptoms during a future outbreak. He explained that there is some benefit to the over-the-counter topical medicine, docosanol.

1. Sacks SL, Thisted RA, Jones TM, et al; Docosanol 10% Cream Study Group. Clinical efficacy of topical docosanol 10% cream for herpes simplex labialis: A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:222-230.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Carter K. Herpes simplex. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:735-742.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed recurrent orolabial herpes. Orolabial herpes typically takes the form of painful vesicles and ulcerative erosions on the tongue, palate, gingiva, buccal mucosa, and lips. Treatment for primary orolabial herpes includes oral acyclovir (200 mg 5 times daily for 5 days), which accelerates healing by one day and can reduce the mean duration of pain by 36%. Alternatively, valacyclovir can be given 2000 mg orally every 12 hours for one day and, like acyclovir, should be started as soon as possible after the onset of symptoms.

Docosanol cream is available without a prescription for oral herpes. One randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 743 patients with herpes labialis showed a faster healing time in patients treated with docosanol 10% cream when compared with placebo cream (4.1 vs 4.8 days), as well as reduced duration of pain symptoms (2.2 vs 2.7 days).1 More than 90% of patients in both groups healed completely within 10 days.1 Treatment with docosanol cream, when applied 5 times per day and within 12 hours of episode onset until symptoms are relieved, is safe and somewhat effective.

Suppression for patients with frequent recurrences may be provided with valacyclovir 500 mg daily or acyclovir 400 mg twice daily.

Suppression was not indicated for this patient since she had infrequent episodes. She was told that the best prevention would be to use a high-potency sunscreen on her lips and face when out in the sun and to use protective clothing such as a broad brim hat. To prevent skin cancers and recurrent oral labial herpes, she was told to avoid the midday sun whenever possible.

The FP also explained that it was too late now to start oral antiviral treatment, but that she might want to use topical petrolatum for symptom relief. He also offered her a prescription for an oral antiviral medicine that she could fill at the start of symptoms during a future outbreak. He explained that there is some benefit to the over-the-counter topical medicine, docosanol.

1. Sacks SL, Thisted RA, Jones TM, et al; Docosanol 10% Cream Study Group. Clinical efficacy of topical docosanol 10% cream for herpes simplex labialis: A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:222-230.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Carter K. Herpes simplex. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:735-742.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed recurrent orolabial herpes. Orolabial herpes typically takes the form of painful vesicles and ulcerative erosions on the tongue, palate, gingiva, buccal mucosa, and lips. Treatment for primary orolabial herpes includes oral acyclovir (200 mg 5 times daily for 5 days), which accelerates healing by one day and can reduce the mean duration of pain by 36%. Alternatively, valacyclovir can be given 2000 mg orally every 12 hours for one day and, like acyclovir, should be started as soon as possible after the onset of symptoms.

Docosanol cream is available without a prescription for oral herpes. One randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 743 patients with herpes labialis showed a faster healing time in patients treated with docosanol 10% cream when compared with placebo cream (4.1 vs 4.8 days), as well as reduced duration of pain symptoms (2.2 vs 2.7 days).1 More than 90% of patients in both groups healed completely within 10 days.1 Treatment with docosanol cream, when applied 5 times per day and within 12 hours of episode onset until symptoms are relieved, is safe and somewhat effective.

Suppression for patients with frequent recurrences may be provided with valacyclovir 500 mg daily or acyclovir 400 mg twice daily.

Suppression was not indicated for this patient since she had infrequent episodes. She was told that the best prevention would be to use a high-potency sunscreen on her lips and face when out in the sun and to use protective clothing such as a broad brim hat. To prevent skin cancers and recurrent oral labial herpes, she was told to avoid the midday sun whenever possible.

The FP also explained that it was too late now to start oral antiviral treatment, but that she might want to use topical petrolatum for symptom relief. He also offered her a prescription for an oral antiviral medicine that she could fill at the start of symptoms during a future outbreak. He explained that there is some benefit to the over-the-counter topical medicine, docosanol.

1. Sacks SL, Thisted RA, Jones TM, et al; Docosanol 10% Cream Study Group. Clinical efficacy of topical docosanol 10% cream for herpes simplex labialis: A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:222-230.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Carter K. Herpes simplex. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:735-742.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Child with malar rash

The patient’s “slapped-cheek” appearance led to the diagnosis: fifth disease (erythema infectiosum). The name of the diagnosis derives from the fact that it represents the fifth of 6 common childhood viral exanthems. Transmission of the causative parvovirus B19 occurs through respiratory secretions (possibly through fomites), parenterally via vertical transmission from mother to fetus, or by transfusion of blood or blood products.

Fifth disease is very contagious via the respiratory route and occurs more frequently between late winter and early summer. Up to 60% of the population is seropositive for antiparvovirus B19 immunoglobulin G (IgG) by age 20. Thirty to 40% of pregnant women lack measurable IgG to the infecting agent and are therefore presumed to be susceptible to infection. Infection during pregnancy can, in some cases, lead to fetal death.

Fifth disease is usually a biphasic illness, starting with upper respiratory tract symptoms that may include headache, fever, sore throat, pruritus, coryza, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and/or arthralgias. These constitutional symptoms coincide with the onset of viremia and usually resolve (for about a week) before the next stage begins. The second stage is characterized by a classic erythematous malar rash with relative circumoral pallor (the “slapped-cheek” appearance in children). This is followed by a “lace-like” erythematous rash on the trunk and extremities.

Pregnant women who are exposed to or have symptoms of parvovirus infection should have serologic testing. Fortunately in this case, the mother and the day care providers were not pregnant. The parents were reassured that this would go away on its own. They were told that their son should avoid excessive heat and sunlight, which can cause the rash to flare up. Children who present with the classic skin findings of fifth disease are past the infectious state and can attend school and day care. The child in this case returned to day care the next day with a note from the FP.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Fifth disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:728-731.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The patient’s “slapped-cheek” appearance led to the diagnosis: fifth disease (erythema infectiosum). The name of the diagnosis derives from the fact that it represents the fifth of 6 common childhood viral exanthems. Transmission of the causative parvovirus B19 occurs through respiratory secretions (possibly through fomites), parenterally via vertical transmission from mother to fetus, or by transfusion of blood or blood products.

Fifth disease is very contagious via the respiratory route and occurs more frequently between late winter and early summer. Up to 60% of the population is seropositive for antiparvovirus B19 immunoglobulin G (IgG) by age 20. Thirty to 40% of pregnant women lack measurable IgG to the infecting agent and are therefore presumed to be susceptible to infection. Infection during pregnancy can, in some cases, lead to fetal death.

Fifth disease is usually a biphasic illness, starting with upper respiratory tract symptoms that may include headache, fever, sore throat, pruritus, coryza, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and/or arthralgias. These constitutional symptoms coincide with the onset of viremia and usually resolve (for about a week) before the next stage begins. The second stage is characterized by a classic erythematous malar rash with relative circumoral pallor (the “slapped-cheek” appearance in children). This is followed by a “lace-like” erythematous rash on the trunk and extremities.

Pregnant women who are exposed to or have symptoms of parvovirus infection should have serologic testing. Fortunately in this case, the mother and the day care providers were not pregnant. The parents were reassured that this would go away on its own. They were told that their son should avoid excessive heat and sunlight, which can cause the rash to flare up. Children who present with the classic skin findings of fifth disease are past the infectious state and can attend school and day care. The child in this case returned to day care the next day with a note from the FP.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Fifth disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:728-731.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The patient’s “slapped-cheek” appearance led to the diagnosis: fifth disease (erythema infectiosum). The name of the diagnosis derives from the fact that it represents the fifth of 6 common childhood viral exanthems. Transmission of the causative parvovirus B19 occurs through respiratory secretions (possibly through fomites), parenterally via vertical transmission from mother to fetus, or by transfusion of blood or blood products.

Fifth disease is very contagious via the respiratory route and occurs more frequently between late winter and early summer. Up to 60% of the population is seropositive for antiparvovirus B19 immunoglobulin G (IgG) by age 20. Thirty to 40% of pregnant women lack measurable IgG to the infecting agent and are therefore presumed to be susceptible to infection. Infection during pregnancy can, in some cases, lead to fetal death.

Fifth disease is usually a biphasic illness, starting with upper respiratory tract symptoms that may include headache, fever, sore throat, pruritus, coryza, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and/or arthralgias. These constitutional symptoms coincide with the onset of viremia and usually resolve (for about a week) before the next stage begins. The second stage is characterized by a classic erythematous malar rash with relative circumoral pallor (the “slapped-cheek” appearance in children). This is followed by a “lace-like” erythematous rash on the trunk and extremities.

Pregnant women who are exposed to or have symptoms of parvovirus infection should have serologic testing. Fortunately in this case, the mother and the day care providers were not pregnant. The parents were reassured that this would go away on its own. They were told that their son should avoid excessive heat and sunlight, which can cause the rash to flare up. Children who present with the classic skin findings of fifth disease are past the infectious state and can attend school and day care. The child in this case returned to day care the next day with a note from the FP.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Fifth disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:728-731.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

From The Journal of Family Practice | 2016;65(5).

Elderly woman with sharp shoulder pain

A 78-year-old woman sought care at our emergency department for sudden-onset right shoulder pain that had begun 5 days earlier. She said the pain was sharp and that it radiated to the scapula, right arm, and chest. She said that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs provided pain relief.

The patient denied any recent trauma or heavy lifting, and was not experiencing extremity weakness, numbness, or tingling. She reported no fever, chills, cough, or night sweats, but said she’d lost 10 pounds over the previous month. The patient was a former smoker whose medical history included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Two years ago, she was treated for recurrent right-sided pleural effusions with pleurocentesis, which was negative for cytology and acid-fast bacilli.

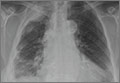

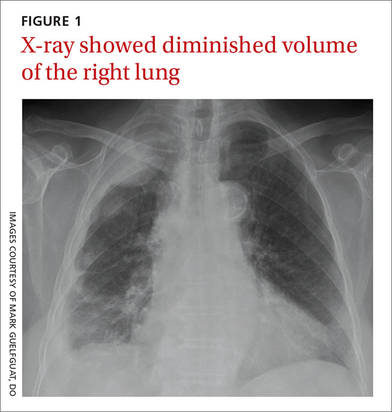

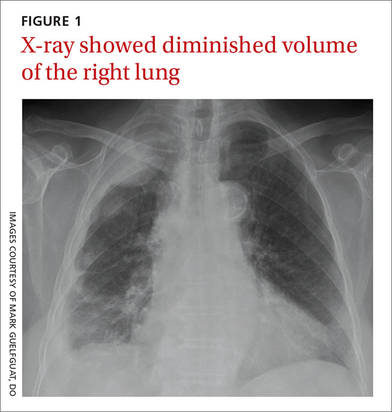

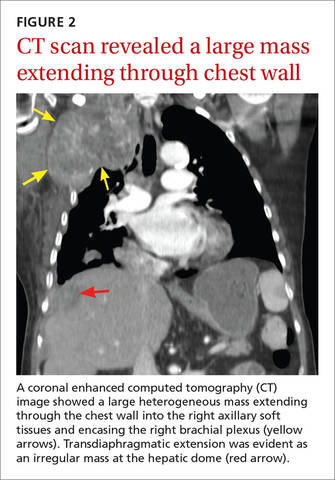

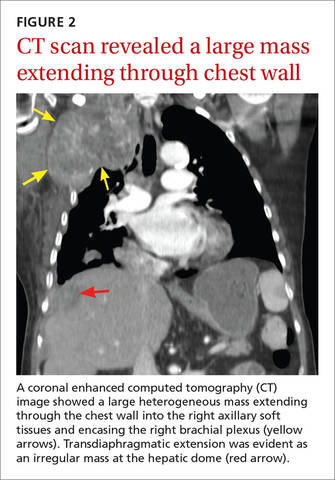

Auscultation revealed crackles in the right lower lung field with decreased breath sounds. The patient had full range of motion in her right shoulder and experienced minimal pain on flexion. She had no swelling, erythema, or tenderness in her right upper extremity and there was no sign of lymphadenopathy. Her laboratory data were noncontributory. A chest radiograph was obtained (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Malignant pleural mesothelioma

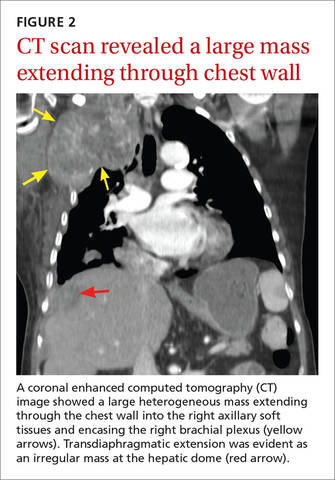

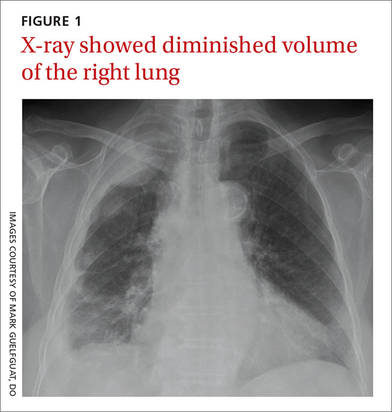

The chest radiograph revealed pleural-based masses extending along the convexity of the right chest wall. (Note the diminished volume of the right lung in FIGURE 1.) A coronal enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan (FIGURE 2) showed a large heterogeneous mass extending through the chest wall into the right axillary soft tissue and encasing the right brachial plexus (yellow arrows). Transdiaphragmatic extension was evident as an irregular mass at the hepatic dome (red arrow). The constellation of findings prompted the radiologist to suspect pleural malignancy.

An aggressive cancer

MPM is a highly aggressive neoplasm of the pleura with rising incidence around the globe.1,2 The annual incidence of mesothelioma in the United States is approximately 3000 cases per year, with the majority linked to asbestos exposure. The latency period is long, typically ranging from 35 to 40 years.1 Our patient, however, did not have a history of asbestos exposure. She was a housewife who had no exposure to building construction or demolition.

Nonspecific complaints. Clinical findings of MPM are frequently nonspecific and may masquerade as innocuous shoulder pain, as illustrated in this case. Patients may also present with dyspnea, nonpleuritic chest pain, and incidental pleural effusions. On examination, unilateral dullness on percussion at the lung base, palpable chest wall masses, and scoliosis toward the sides of the lesion may be present.3

Differential Dx of shoulder pain includes rotator cuff disorders, tears

The differential diagnosis of shoulder pain includes rotator cuff disorders, acromioclavicular osteoarthritis, and cervical radiculopathy from degenerative spondylosis.

Rotator cuff tendinopathy and tears usually present with pain on overhead activity, positional test muscle weakness, and evidence of impingement. Acromioclavicular osteoarthritis usually causes acromioclavicular joint tenderness, which can be relieved with diagnostic intra-articular anesthetic injections. Pain from cervical spondylosis is usually accompanied by numbness and weakness in the arms and hands and muscle spasms in the neck. Also, the symptoms are usually aggravated by downward compression of the head (Spurling’s test).4,5

Chest radiographs are useful, but CT scans are more sensitive

Often, MPM is initially suspected because of unilateral pleural nodularity or thickening with a large, unilateral pleural effusion on a chest radiograph.6 Pleural plaques may also be seen. As the tumor grows, encasing the lung and invading the fissures, it leads to volume loss of the affected side, which can also be identified radiographically.1

CT is a more sensitive way to detect pleural and pulmonary parenchymal involvement, as well as invasion of adjacent thoracic structures, including the chest wall, pericardium, diaphragm, and the mediastinal lymph nodes.1

When mesothelioma is suspected because of clinical or radiologic data, experts recommend that cytologic findings from thoracentesis be followed by tissue confirmation from thoracoscopy or CT biopsy.2

Chemotherapy, Yes, but there are many Tx unknowns

The best approach to treatment of MPM remains controversial due to the rarity of the disease and the scarcity of randomized prospective trials. Surgical resection is most often performed when the disease is confined to the pleural space. An extrapleural pneumonectomy is usually performed for stage I disease, when the tumor is limited to one hemithorax, invading the pleura and involving the lung, endothoracic fascia, diaphragm, or pericardium.7

Unfortunately, mesothelioma is highly radioresistant; patients often endure severe toxicity due to large radiation fields. Chemotherapy, either as single agents or in combination, can be administered systemically or directly into the pleural space. Combination chemotherapy using cisplatin and pemetrexed is currently the standard of care, based upon a phase III trial that demonstrated prolonged overall survival with the combination compared to treatment with cisplatin alone (12.1 months vs 9.3 months).8

Other agents used to treat MPM. Five other chemotherapy agents are also used in the treatment of MPM. Used individually, the maximum response rates to these agents are as follows: methotrexate (37%), mitomycin (21%), doxorubicin (16%), cyclophosphamide (13%), and carboplatin (11%).7

Our patient. The rest of our patient’s hospital course was uncomplicated. She was not a surgical candidate because she had such extensive tumor involvement. She was discharged with a referral to an outpatient oncology clinic. Despite 2 cycles of carboplatin and pemetrexed, and palliative radiation therapy to the right upper thoracic mass, the disease progressed with worsening right upper extremity pain and neurologic deficits.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mark Guelfguat, DO, Jacobi Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1400 S Pelham Parkway, Building 1, Room 4N15, Bronx, NY 10461; [email protected].

1. Miller BH, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Mason AC, et al. From the archives of the AFIP. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1996;16:613-644.

2. Scherpereel A, Astoul P, Baas P, et al; European Respiratory Society/European Society of Thoracic Surgeons Task Force. Guidelines of the European Respiratory Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons for the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:479-495.

3. Antman KH. Natural history and epidemiology of malignant mesothelioma. Chest. 1993;103:373S-376S.

4. Burbank KM, Stevenson JH, Czarnecki GR, et al. Chronic shoulder pain: part I. Evaluation and diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:453-460.

5. Anekstein Y, Blecher R, Smorgick Y, et al. What is the best way to apply the Spurling test for cervical radiculopathy? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:2566-2572.

6. British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee. Statement on malignant mesothelioma in the United Kingdom. Thorax. 2001;56:250-265.

7. Aisner J. Current approach to malignant mesothelioma of the pleura. Chest. 1995;107:332S-344S.

8. Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, et al. Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2636-2644.

A 78-year-old woman sought care at our emergency department for sudden-onset right shoulder pain that had begun 5 days earlier. She said the pain was sharp and that it radiated to the scapula, right arm, and chest. She said that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs provided pain relief.

The patient denied any recent trauma or heavy lifting, and was not experiencing extremity weakness, numbness, or tingling. She reported no fever, chills, cough, or night sweats, but said she’d lost 10 pounds over the previous month. The patient was a former smoker whose medical history included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Two years ago, she was treated for recurrent right-sided pleural effusions with pleurocentesis, which was negative for cytology and acid-fast bacilli.

Auscultation revealed crackles in the right lower lung field with decreased breath sounds. The patient had full range of motion in her right shoulder and experienced minimal pain on flexion. She had no swelling, erythema, or tenderness in her right upper extremity and there was no sign of lymphadenopathy. Her laboratory data were noncontributory. A chest radiograph was obtained (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Malignant pleural mesothelioma

The chest radiograph revealed pleural-based masses extending along the convexity of the right chest wall. (Note the diminished volume of the right lung in FIGURE 1.) A coronal enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan (FIGURE 2) showed a large heterogeneous mass extending through the chest wall into the right axillary soft tissue and encasing the right brachial plexus (yellow arrows). Transdiaphragmatic extension was evident as an irregular mass at the hepatic dome (red arrow). The constellation of findings prompted the radiologist to suspect pleural malignancy.

An aggressive cancer

MPM is a highly aggressive neoplasm of the pleura with rising incidence around the globe.1,2 The annual incidence of mesothelioma in the United States is approximately 3000 cases per year, with the majority linked to asbestos exposure. The latency period is long, typically ranging from 35 to 40 years.1 Our patient, however, did not have a history of asbestos exposure. She was a housewife who had no exposure to building construction or demolition.

Nonspecific complaints. Clinical findings of MPM are frequently nonspecific and may masquerade as innocuous shoulder pain, as illustrated in this case. Patients may also present with dyspnea, nonpleuritic chest pain, and incidental pleural effusions. On examination, unilateral dullness on percussion at the lung base, palpable chest wall masses, and scoliosis toward the sides of the lesion may be present.3

Differential Dx of shoulder pain includes rotator cuff disorders, tears

The differential diagnosis of shoulder pain includes rotator cuff disorders, acromioclavicular osteoarthritis, and cervical radiculopathy from degenerative spondylosis.

Rotator cuff tendinopathy and tears usually present with pain on overhead activity, positional test muscle weakness, and evidence of impingement. Acromioclavicular osteoarthritis usually causes acromioclavicular joint tenderness, which can be relieved with diagnostic intra-articular anesthetic injections. Pain from cervical spondylosis is usually accompanied by numbness and weakness in the arms and hands and muscle spasms in the neck. Also, the symptoms are usually aggravated by downward compression of the head (Spurling’s test).4,5

Chest radiographs are useful, but CT scans are more sensitive

Often, MPM is initially suspected because of unilateral pleural nodularity or thickening with a large, unilateral pleural effusion on a chest radiograph.6 Pleural plaques may also be seen. As the tumor grows, encasing the lung and invading the fissures, it leads to volume loss of the affected side, which can also be identified radiographically.1

CT is a more sensitive way to detect pleural and pulmonary parenchymal involvement, as well as invasion of adjacent thoracic structures, including the chest wall, pericardium, diaphragm, and the mediastinal lymph nodes.1

When mesothelioma is suspected because of clinical or radiologic data, experts recommend that cytologic findings from thoracentesis be followed by tissue confirmation from thoracoscopy or CT biopsy.2

Chemotherapy, Yes, but there are many Tx unknowns

The best approach to treatment of MPM remains controversial due to the rarity of the disease and the scarcity of randomized prospective trials. Surgical resection is most often performed when the disease is confined to the pleural space. An extrapleural pneumonectomy is usually performed for stage I disease, when the tumor is limited to one hemithorax, invading the pleura and involving the lung, endothoracic fascia, diaphragm, or pericardium.7

Unfortunately, mesothelioma is highly radioresistant; patients often endure severe toxicity due to large radiation fields. Chemotherapy, either as single agents or in combination, can be administered systemically or directly into the pleural space. Combination chemotherapy using cisplatin and pemetrexed is currently the standard of care, based upon a phase III trial that demonstrated prolonged overall survival with the combination compared to treatment with cisplatin alone (12.1 months vs 9.3 months).8

Other agents used to treat MPM. Five other chemotherapy agents are also used in the treatment of MPM. Used individually, the maximum response rates to these agents are as follows: methotrexate (37%), mitomycin (21%), doxorubicin (16%), cyclophosphamide (13%), and carboplatin (11%).7

Our patient. The rest of our patient’s hospital course was uncomplicated. She was not a surgical candidate because she had such extensive tumor involvement. She was discharged with a referral to an outpatient oncology clinic. Despite 2 cycles of carboplatin and pemetrexed, and palliative radiation therapy to the right upper thoracic mass, the disease progressed with worsening right upper extremity pain and neurologic deficits.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mark Guelfguat, DO, Jacobi Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1400 S Pelham Parkway, Building 1, Room 4N15, Bronx, NY 10461; [email protected].

A 78-year-old woman sought care at our emergency department for sudden-onset right shoulder pain that had begun 5 days earlier. She said the pain was sharp and that it radiated to the scapula, right arm, and chest. She said that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs provided pain relief.

The patient denied any recent trauma or heavy lifting, and was not experiencing extremity weakness, numbness, or tingling. She reported no fever, chills, cough, or night sweats, but said she’d lost 10 pounds over the previous month. The patient was a former smoker whose medical history included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Two years ago, she was treated for recurrent right-sided pleural effusions with pleurocentesis, which was negative for cytology and acid-fast bacilli.

Auscultation revealed crackles in the right lower lung field with decreased breath sounds. The patient had full range of motion in her right shoulder and experienced minimal pain on flexion. She had no swelling, erythema, or tenderness in her right upper extremity and there was no sign of lymphadenopathy. Her laboratory data were noncontributory. A chest radiograph was obtained (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Malignant pleural mesothelioma

The chest radiograph revealed pleural-based masses extending along the convexity of the right chest wall. (Note the diminished volume of the right lung in FIGURE 1.) A coronal enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan (FIGURE 2) showed a large heterogeneous mass extending through the chest wall into the right axillary soft tissue and encasing the right brachial plexus (yellow arrows). Transdiaphragmatic extension was evident as an irregular mass at the hepatic dome (red arrow). The constellation of findings prompted the radiologist to suspect pleural malignancy.

An aggressive cancer

MPM is a highly aggressive neoplasm of the pleura with rising incidence around the globe.1,2 The annual incidence of mesothelioma in the United States is approximately 3000 cases per year, with the majority linked to asbestos exposure. The latency period is long, typically ranging from 35 to 40 years.1 Our patient, however, did not have a history of asbestos exposure. She was a housewife who had no exposure to building construction or demolition.

Nonspecific complaints. Clinical findings of MPM are frequently nonspecific and may masquerade as innocuous shoulder pain, as illustrated in this case. Patients may also present with dyspnea, nonpleuritic chest pain, and incidental pleural effusions. On examination, unilateral dullness on percussion at the lung base, palpable chest wall masses, and scoliosis toward the sides of the lesion may be present.3

Differential Dx of shoulder pain includes rotator cuff disorders, tears

The differential diagnosis of shoulder pain includes rotator cuff disorders, acromioclavicular osteoarthritis, and cervical radiculopathy from degenerative spondylosis.

Rotator cuff tendinopathy and tears usually present with pain on overhead activity, positional test muscle weakness, and evidence of impingement. Acromioclavicular osteoarthritis usually causes acromioclavicular joint tenderness, which can be relieved with diagnostic intra-articular anesthetic injections. Pain from cervical spondylosis is usually accompanied by numbness and weakness in the arms and hands and muscle spasms in the neck. Also, the symptoms are usually aggravated by downward compression of the head (Spurling’s test).4,5

Chest radiographs are useful, but CT scans are more sensitive